Varietal Discrimination of Purple, Red, and White Rice Bran Oils Based on Physicochemical Properties, Bioactive Compounds, and Lipidomic Profiles

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Physicochemical Parameters of the RBOs

2.2. Fatty Acid Composition of RBOs

2.3. Bioactive Compounds of RBOs

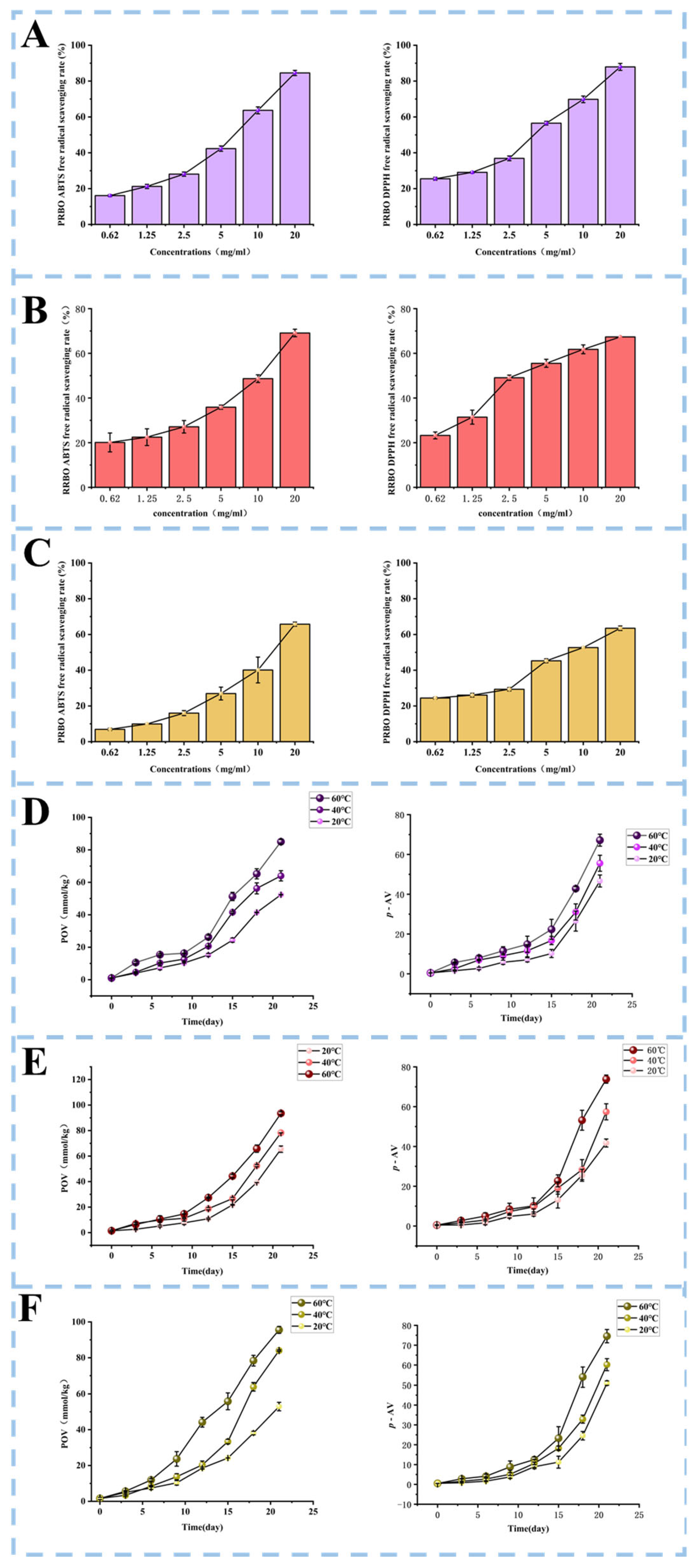

2.4. Radical-Scavenging Capacity of RBOs

2.5. Oxidation Stability of RBOs

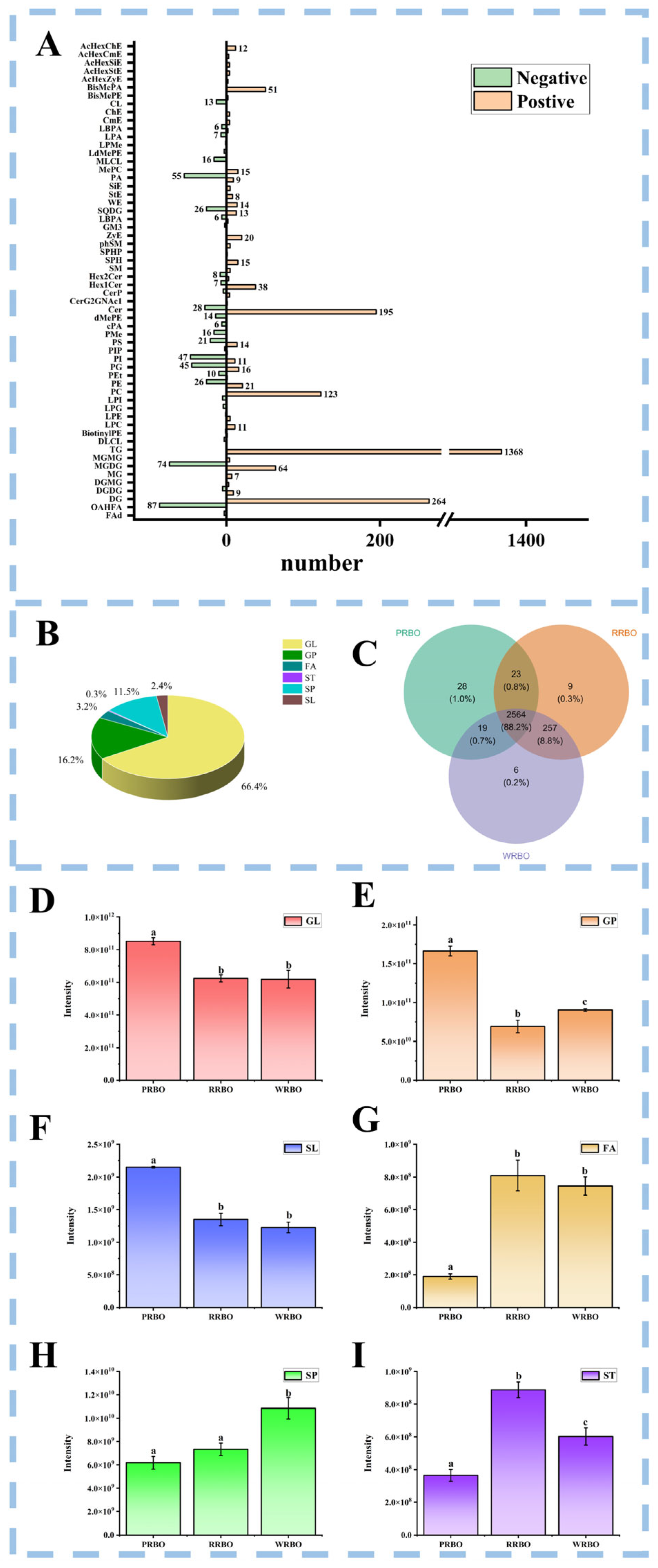

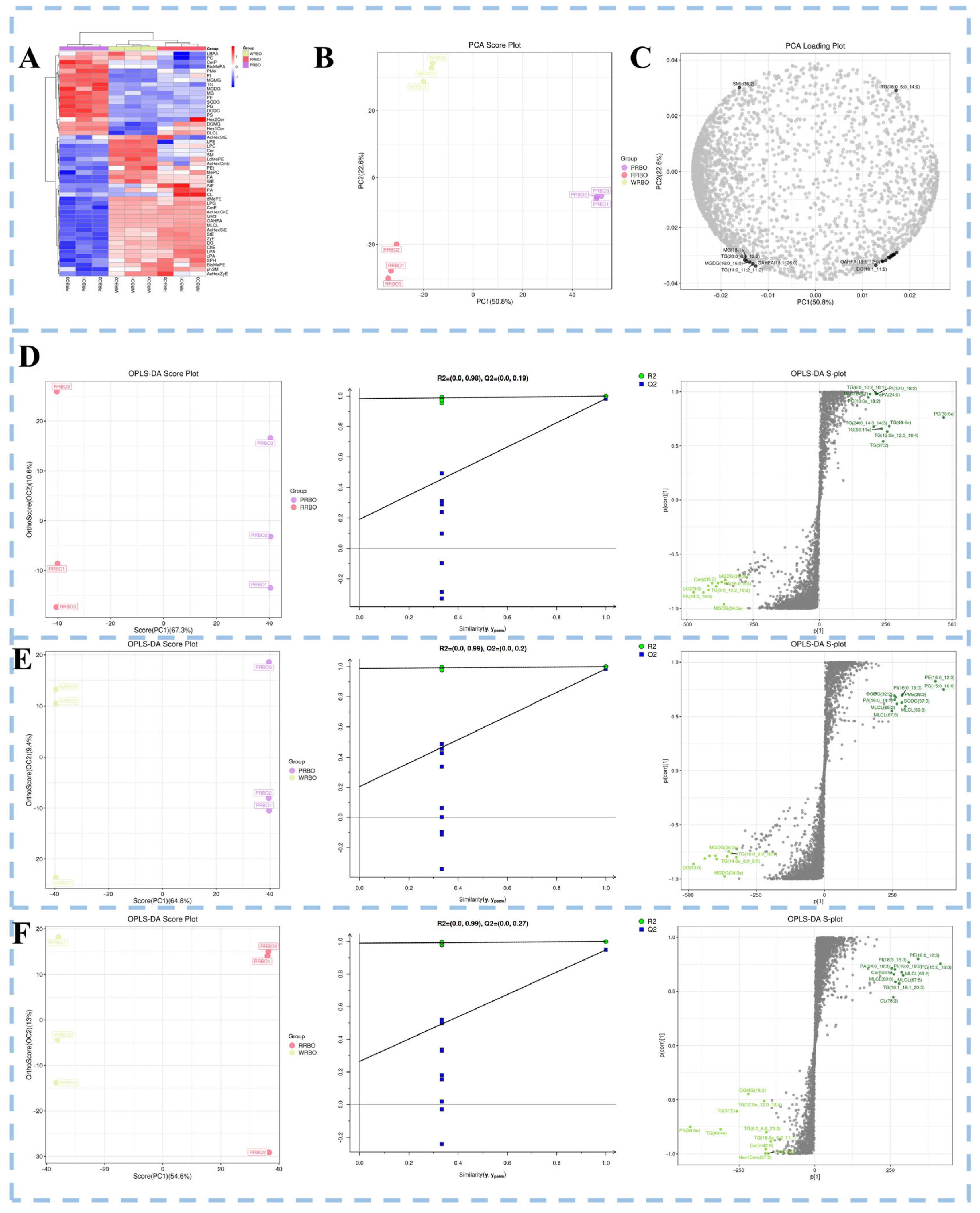

2.6. Lipidomics Profiling of RBOs

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Sample Preparation

3.3. Physicochemical Analysis

3.4. Fatty Acid Composition

3.5. Bioactive Compound Analysis

3.5.1. Oryzanol

3.5.2. Phytosterols

3.5.3. Tocopherols and Tocotrienols

3.5.4. Squalene

3.6. Radical-Scavenging Capacity

3.6.1. DPPH Radical Scavenging Assay

3.6.2. ABTS Radical Scavenging Assay

3.7. Oxidative Stability Evaluation

3.8. Lipidomics Analysis

3.9. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AV | Acid value |

| ABTS | 2,2′-azino-bi (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) |

| AcHexChE | Acylhexosyl cholesteryl ester |

| AcHexCmE | Acylhexosyl campesteryl ester |

| AcHexSiE | Acylhexosyl sitosteryl ester |

| AcHexStE | Acylhexosyl sterol ester |

| AcHexZyE | Acylhexosyl zymosterol |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| AOCS | American Oil Chemists’ Society |

| Cer | Ceramides |

| CerG2GNAc1 | Ceramide glycosides |

| CerP | Ceramide phosphate |

| ChE | Cholesteryl ester |

| CL | Cardiolipin |

| CmE | Campesteryl ester |

| DG | Diacylglycerols |

| DGDG | Digalactosyldiacylglycerols |

| DGMG | Digalactosyl monoacylglycerols |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| FA | Fatty acyls |

| FAd | Fatty acids |

| FAMEs | Fatty acid methyl esters |

| FID | Flame ionization detector |

| GC-FID | Gas chromatography–flame ionization detector |

| GL | Glycerolipids |

| GM3 | Monosialodihexosylganglioside |

| GP | Glycerophospholipids |

| Hex1Cer | Monohexosylceramides |

| Hex2Cer | Dihydroxyceramides |

| HPLC | High Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| IV | Iodine value |

| LC-MS | Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| LdMePE | Lysodimethylphosphatidylethanolamine |

| LPA | Lysophosphatidic acid |

| LPC | Lysophosphatidylcholine |

| LPE | Lysophosphatidylethanolamine |

| LPG | Lysophosphatidylglycerol |

| MGDG | Monogalactosyldiacylglycerols |

| MGMG | Monogalactosyl monoacylglycerols |

| MTBE | Methyl tert-butyl ether |

| OAHFA | O-acyl-1-hydroxy fatty acids |

| OPLS-DA | Orthogonal PLS-DA |

| PA | Phosphatidic acid |

| p-AV | P-anisidine value |

| PC | Phosphatidylcholines |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| PE | Phosphatidylethanolamine |

| PEt | Phosphatidylethanol |

| PG | Phosphatidylglycerols |

| phSM | Plant sphingosine |

| PI | Phosphatidylinositols |

| POV | Peroxide value |

| PRBO | Purple rice bran oil |

| PS | Phosphatidylserine |

| RBO | Rice bran oil |

| RRBO | Red rice bran oil |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SiE | Sitosteryl esters |

| SL | Saccharolipids |

| SM | sphingomyelin |

| SP | Sphingolipids |

| SPH | Sphingosines |

| SPHP | Sphingosine-1-phosphate |

| SQDG | Sulfoquinovosyldiacylglycerols |

| ST | Sterol lipids |

| StE | Sterol ester |

| TG | Triacylglycerols |

| WE | Wax esters |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| WRBO | White rice bran oil |

| ZyE | Zymosterol |

References

- Spaggiari, M.; Dall’Asta, C.; Galaverna, G.; del Castillo Bilbao, M.D. Rice bran by-product: From valorization strategies to nutritional perspectives. Foods 2021, 10, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, K.; Yousuf, B.; Singh, A.; Singh, P.; Wani, A.A. Rice bran: Nutritional values and its emerging potential for development of functional food—A review. Bioact. Carbohydr. Diet. Fibre 2015, 6, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punia, S.; Kumar, M.; Siroha, A.K.; Purewal, S.S. Rice bran oil: Emerging trends in extraction, health benefit, and its industrial application. Rice Sci. 2021, 28, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhao, G.; Chen, Z.-Y. Dietary wheat bran oil is equally as effective as rice bran oil in reducing plasma cholesterol. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 2765–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Xiao, X.; Jin, D.; Zhai, L.; Li, Y.; Yang, Q.; Xing, F.; Qiao, W.; Yan, X.; Tang, Q. Composition and Biological Activity of Colored Rice—A Comprehensive Review. Foods 2025, 14, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Ko, J.; Ahn, S.-J.; Kim, H.J.; Min, S.-S.; Kim, E. Potential effects of pigmented rice on immunity: A review focusing on anthocyanins, gamma-oryzanol, and arabinoxylan. J. Food Nutr. Res. 2021, 9, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, V.; Ferreira, C.D.; Hoffmann, J.F.; Chaves, F.C.; Vanier, N.L.; de Oliveira, M.; Elias, M.C. Cooking quality properties and free and bound phenolics content of brown, black, and red rice grains stored at different temperatures for six months. Food Chem. 2018, 242, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.-H.; McClung, A.M.; Bergman, C.J. Phenolic content, anthocyanins and antiradical capacity of diverse purple bran rice genotypes as compared to other bran colors. J. Cereal Sci. 2017, 77, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phannasorn, W.; Chariyakornkul, A.; Sookwong, P.; Wongpoomchai, R. Comparative studies on the Hepatoprotective effect of white and Coloured Rice bran oil against acetaminophen-induced oxidative stress in mice through antioxidant-and xenobiotic-metabolizing systems. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 5510230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balegh, S.M.; Saadati, P.; Safiaghdam, M.; Fakhari, A.A.; Razavi, R. Effect of cold atmospheric plasma pre-treatment and ultrasound-assisted extraction on bioactive compounds and chemical quality of rice bran oil. LWT 2025, 218, 117451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siripattanakulkajorn, C.; Sombutsuwan, P.; Villeneuve, P.; Barea, B.; Domingo, R.; Lebrun, M.; Aryusuk, K.; Durand, E. Physical properties and oxidative stability of mayonnaises fortified with natural deep eutectic solvent, either alone or enriched with pigmented rice bran. Food Chem. 2025, 463, 141124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingyai, S.; Srikaeo, K.; Kettawan, A.; Singanusong, R.; Nakagawa, K.; Kimura, F.; Ito, J. Effects of extraction methods on phytochemicals of rice bran oils produced from colored rice. J. Oleo Sci. 2018, 67, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modupalli, N.; Krisshnan, A.; CK, S.; DV, C.; Natarajan, V.; Koidis, A.; Rawson, A. Effect of novel combination processing technologies on extraction and quality of rice bran oil. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 1911–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, J.F.; Dal Prá, V.; de Souza, M.; Lunelli, F.C.; Abaide, E.; da Silva, J.R.; Kuhn, R.C.; Martínez, J.; Mazutti, M.A. Extraction of rice bran oil using supercritical CO2 and compressed liquefied petroleum gas. J. Food Eng. 2016, 170, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, J.F.; Prá, V.D.; Barrales, F.M.; Dos Santos, P.; Kuhn, R.C.; Rezende, C.A.; Martínez, J.; Mazutti, M.A. Extraction of rice bran oil using supercritical CO2 combined with ultrasound. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 2018, 35, 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, V.M.; Junyusen, T.; Liplap, P.; Junyusen, P. Effects of ultrasonication and thermal cooking pretreatments on the extractability and quality of cold press extracted rice bran oil. J. Food Process Eng. 2019, 42, e12975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimpa, B.; Thongraung, C.; Sutthirak, P. Effect of solvents and extraction conditions on the properties of crude rice bran oil. Walailak J. Sci. Technol. (WJST) 2021, 18, 9611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, S.; Zhang, M.; Yang, H.; Li, G.; Ren, X.; Liang, S. Optimization of oil extraction from rice bran with mixed solvent using response surface methodology. Foods 2022, 11, 3849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CODEX STAN 210–1999; Codex Standard for Named Vegetable Oils. Codex Alimentarius Commission: Rome, Italy, 1999.

- Zhang, D.; Duan, X.; Wang, Y.; Shang, B.; Liu, H.; Sun, H.; Wang, Y. A comparative investigation on physicochemical properties, chemical composition, and in vitro antioxidant activities of rice bran oils from different japonica rice (Oryza sativa L.) varieties. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2021, 15, 2064–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunita, E.; Nasaruddin, M.L.; Ramli, N.Z.; Yahaya, M.F.; Ahmad Damanhuri, H. Scoping Review: The Role of Tocotrienol-Rich Fraction as a Potent Neuroprotective Agent. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juricic, H.; Cuccioloni, M.; Bonfili, L.; Angeletti, M.; Uberti, D.; Eleuteri, A.M.; Abate, G.; Cecarini, V. Biochemical, Biological, and Clinical Properties of γ-Oryzanol. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattananandecha, T.; Sirithunyalug, J.; Sirithunyalug, B.; Thiankhanithikun, K.; Khanongnuch, C.; Saenjum, C. Bioactive compounds constituent and anti-inflammatory activity of natural rice bran oil produced from colored and non-pigmented rice in northern Thailand. J. Pharm. Nutr. Sci. 2019, 9, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Ji, T.; Zhang, M.; Fang, B. Recent advances in squalene: Biological activities, sources, extraction, and delivery systems. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 146, 104392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, B.-H.; Truong, V.-L.; Jeong, W.-S. Phytosterols: Extraction Methods, Analytical Techniques, and Biological Activity. Molecules 2025, 30, 2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junyusen, T.; Chatchavanthatri, N.; Liplap, P.; Junyusen, P.; Phan, V.M.; Nawong, S. Effects of extraction processes on the oxidative stability, bioactive phytochemicals, and antioxidant activity of crude rice bran oil. Foods 2022, 11, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.T.; Liu, K.; Han, S.; Jatoi, M.A. The effects of thermal treatment on lipid oxidation, protein changes, and storage stabilization of rice bran. Foods 2022, 11, 4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.R.; Rosado, E.L.; Soares-Mota, M. Influence of the dietary intake of medium chain triglycerides on body composition, energy expenditure and satiety; a systematic review. Nutr. Hosp. 2012, 27, 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.; Liu, L.; Li, J.; Zhu, B.; Li, X.; Cheng, J.; Muneeb, M.; Kouame, K.J.E.-p.; Jiang, X. Enhancing the physical stability and bioaccessibility of curcumin emulsions through the interaction of whey protein isolate and soybean lecithin. Food Biosci. 2024, 58, 103676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolter, T. A view on sphingolipids and disease. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2011, 164, 590–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkas, F.; Nomikos, T.; Liberopoulos, E.; Panagiotakos, D. Diet and cardiovascular disease risk among individuals with familial hypercholesterolemia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudiß, K.; Ayata, C.K.; Lazar, Z.; Cicko, S.; Beckert, J.; Meyer, A.; Zech, A.; Vieira, R.P.; Bittman, R.; Gómez-Muñoz, A. Ceramide-1-phosphate inhibits cigarette smoke-induced airway inflammation. Eur. Respir. J. 2015, 45, 1669–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, K.; Komatsu, S.; Kuno, H.; Asai, S.; Matsuura, I.; Kudkyal, V.R.; Kawahara, T. Virucidal and immunostimulating activities of monogalactosyl diacylglyceride from Coccomyxa sp. KJ, a green microalga, against murine norovirus and feline calicivirus. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paradies, G.; Paradies, V.; Ruggiero, F.M.; Petrosillo, G. Cardiolipin and mitochondrial function in health and disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014, 20, 1925–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carman, G.M.; Han, G.-S. Fat-regulating phosphatidic acid phosphatase: A review of its roles and regulation in lipid homeostasis. J. Lipid Res. 2019, 60, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Chen, G. The nutritional functions of dietary sphingomyelin and its applications in food. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1002574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Zhou, Y.; Li, T.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, W. Comprehensive characterization of the lipid profiles in five mango kernel oils using integrated lipidomics and chemometrics. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 220, 119216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, N.; Castanho, A.; Lageiro, M.; Pereira, C.; Brites, C.M.; Vaz-Velho, M. Rice bran stabilisation and oil extraction using the microwave-assisted method and its effects on GABA and gamma-oryzanol compounds. Foods 2022, 11, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOCS Official Method Cd 3d-63; Acid Value. American Oil Chemists’ Society: Urbana, IL, USA, 2017.

- AOCS Official Method Cd 1-87; Iodine Value of Fats and Oils—Cyclohexane Method. American Oil Chemists’ Society: Urbana, IL, USA, 2012.

- AOCS Official Method Cd 8-53; Peroxide Value—Acetic Acid–Chloroform Method. AOCS Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 2005.

- AOCS Official Method Ce 2-66; Preparation of Methyl Esters of Fatty Acids. American Oil Chemists’ Society: Urbana, IL, USA, 1997.

- AOCS Official Method Ce 8-89; Determination of Tocopherols and Tocotrienols in Vegetable Oils and Fats by HPLC. American Oil Chemists’ Society: Champaign, IL, USA, 1997.

- Xu, D.; Hao, J.; Wang, Z.; Liang, D.; Wang, J.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, M. Physicochemical properties, fatty acid compositions, bioactive compounds, antioxidant activity and thermal behavior of rice bran oil obtained with aqueous enzymatic extraction. LWT 2021, 149, 111817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Xu, Y.; Chang, M.; Tang, L.; Lu, M.; Liu, R.; Jin, Q.; Wang, X. Antioxidant interaction of α-tocopherol, γ-oryzanol and phytosterol in rice bran oil. Food Chem. 2021, 343, 128431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, C.-C.; Zeng, F.-K.; Wu, N.-N.; Tan, B. Functional, physicochemical and structural properties of soluble dietary fiber from rice bran with extrusion cooking treatment. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 121, 107057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PRBO | RRBO | WRBO | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extraction ratio (%) | 7.90 ± 0.30 a | 6.90 ± 0.46 b | 6.03 ± 0.29 c |

| Acid value (mg KOH/g oil) | 3.68 ± 0.04 a | 9.26 ± 0.01 b | 9.45 ± 0.06 c |

| Iodine value (g I2/100 g oil) | 139.00 ± 2.40 a | 127.35 ± 4.50 b | 124.46 ± 2.47 b |

| Peroxide value (POV) (mmol/kg) | 1.04 ± 0.17 a | 1.45 ± 0.54 b | 1.61 ± 0.62 c |

| L* | 18.98 ± 0.09 a | 53.16 ± 0.02 b | 60.12 ± 0.01 c |

| a* | 9.35 ± 0.15 a | 1.31 ± 0.03 b | 1.43 ± 0.06 c |

| b* | 36.35 ± 0.34 a | 38.81 ± 0.04 b | 14.98 ± 0.06 c |

| Sample | PRBO | RRBO | WRBO |

|---|---|---|---|

| C16:0 | 15.47 ± 0.03 a | 16.78 ± 0.03 b | 16.79 ± 0.03 b |

| C18:0 | 1.77 ± 0.02 a | 2.43 ± 0.01 b | 2.43 ± 0.01 b |

| C18:1 | 43.12 ± 0.39 a | 43.59 ± 0.14 a | 43.51 ± 0.15 a |

| C18:2 | 34.17 ± 0.18 a | 31.75 ± 0.08 b | 31.59 ± 0.30 b |

| C18:3 | 1.61 ± 0.01 a | 1.20 ± 0.02 b | 1.23 ± 0.06 b |

| C20:0 | 0.86 ± 0.02 a | 0.93 ± 0.02 b | 0.92 ± 0.01 b |

| C20:1 | 0.60 ± 0.02 a | 0.53 ± 0.03 b | 0.51 ± 0.03 b |

| C22:0 | 0.56 ± 0.02 a | 0.37 ± 0.01 b | 0.38 ± 0.01 b |

| C24:0 | 1.86 ± 0.03 a | 2.42 ± 0.09 b | 2.65 ± 0.14 b |

| SFA | 20.51 ± 0.05 a | 22.93 ± 0.02 b | 23.17 ± 0.03 b |

| MUFS | 43.72 ± 0.38 a | 44.11 ± 0.17 a | 44.02 ± 0.17 a |

| PUFA | 35.77 ± 0.18 a | 32.95 ± 0.08 b | 32.81 ± 0.24 b |

| Sample | PRBO | RRBO | WRBO |

|---|---|---|---|

| α-tocopherol (mg/kg) | 220.82 ± 5.94 | ND | ND |

| β-tocopherol (mg/kg) | 290.32 ± 0.94 a | 42.18 ± 1.59 b | 10.19 ± 0.28 c |

| γ-tocopherol (mg/kg) | 691.57 ± 5.59 a | 105.2 ± 2.34 b | ND |

| α-tocotrienol (mg/kg) | 71.99 ± 3.18 | ND | ND |

| Squalene (mg/kg) | 500.17 ± 7.62 a | 211.25 ± 0.94 b | 90.59 ± 1.15 c |

| Phytosterol (mg/g) | 0.20 ± 0.02 a | 0.20 ± 0.06 a | 0.14 ± 0.01 b |

| γ-oryzanol (g/100 g) | 2.52 ± 0.03 a | 1.86 ± 0.04 b | 0.83 ± 0.02 c |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zheng, P.; Qin, Y.; Yin, X.; Cao, J.; Wang, S.; Cheng, G. Varietal Discrimination of Purple, Red, and White Rice Bran Oils Based on Physicochemical Properties, Bioactive Compounds, and Lipidomic Profiles. Molecules 2026, 31, 308. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020308

Zheng P, Qin Y, Yin X, Cao J, Wang S, Cheng G. Varietal Discrimination of Purple, Red, and White Rice Bran Oils Based on Physicochemical Properties, Bioactive Compounds, and Lipidomic Profiles. Molecules. 2026; 31(2):308. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020308

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Peng, Yuyue Qin, Xiaoyu Yin, Jianxin Cao, Shujie Wang, and Guiguang Cheng. 2026. "Varietal Discrimination of Purple, Red, and White Rice Bran Oils Based on Physicochemical Properties, Bioactive Compounds, and Lipidomic Profiles" Molecules 31, no. 2: 308. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020308

APA StyleZheng, P., Qin, Y., Yin, X., Cao, J., Wang, S., & Cheng, G. (2026). Varietal Discrimination of Purple, Red, and White Rice Bran Oils Based on Physicochemical Properties, Bioactive Compounds, and Lipidomic Profiles. Molecules, 31(2), 308. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020308