Stereoselective Synthesis and Structural Confirmation of All Four 8-Hydroxyhexahydrocannabinol Stereoisomers

Abstract

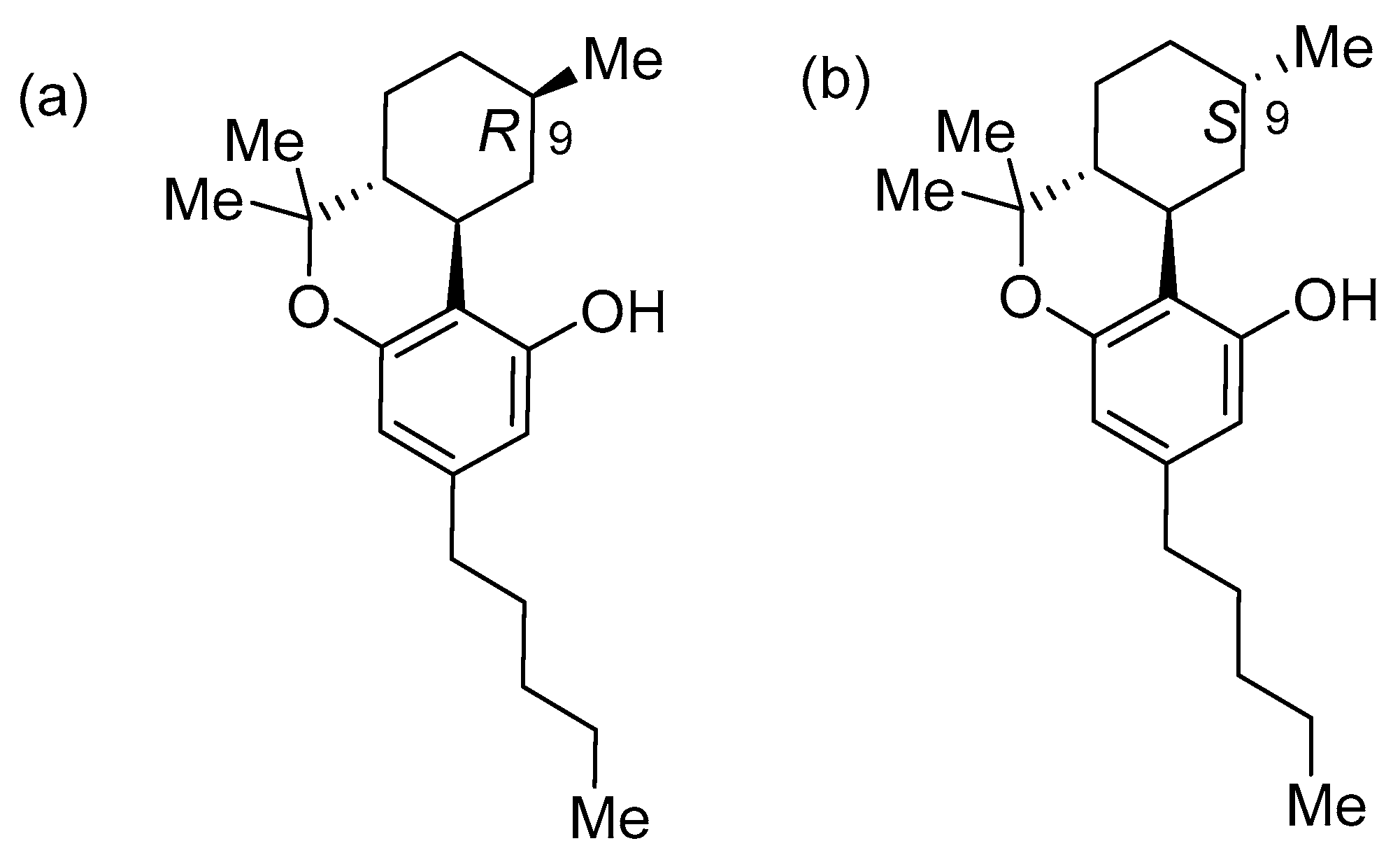

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

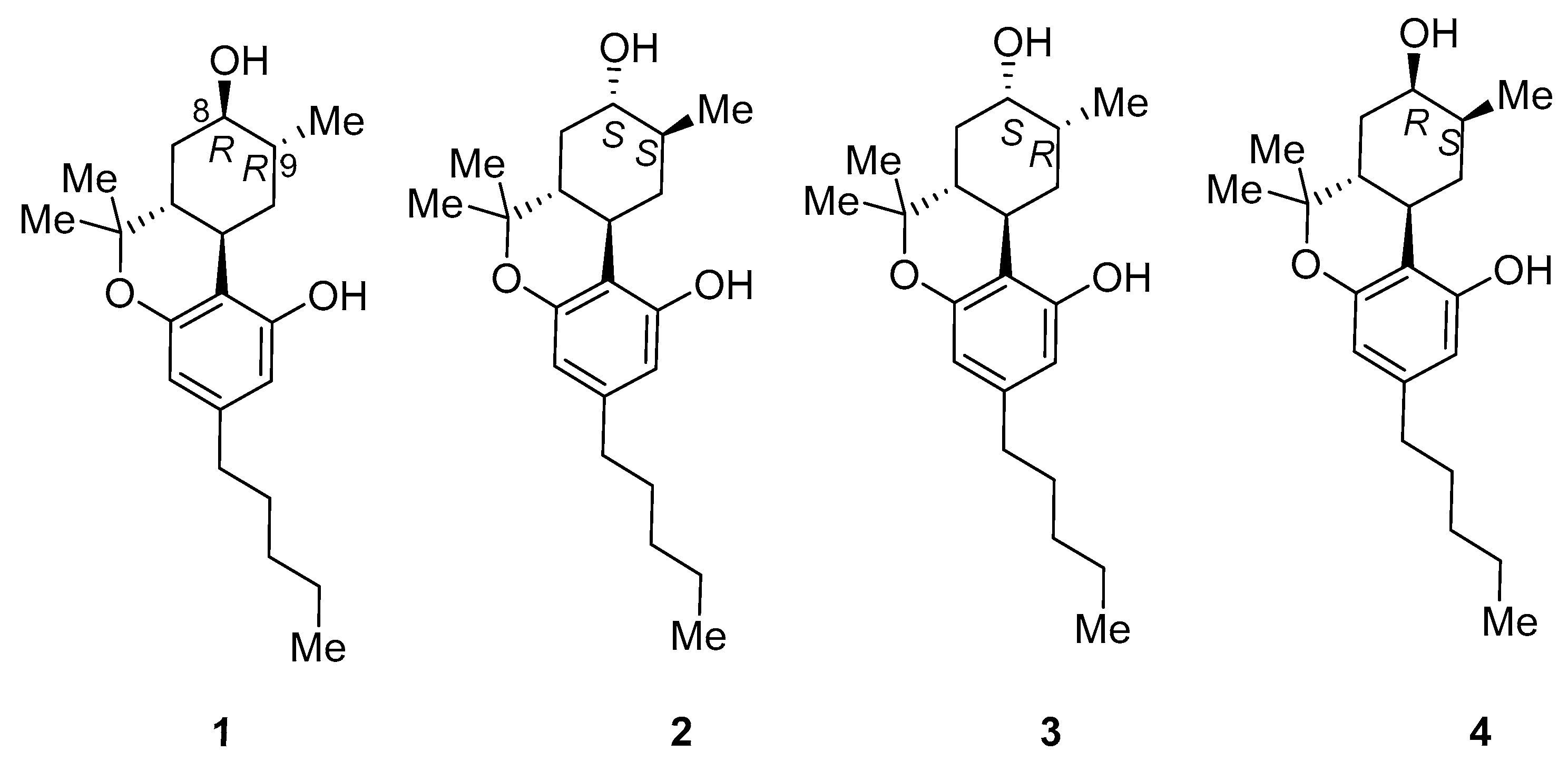

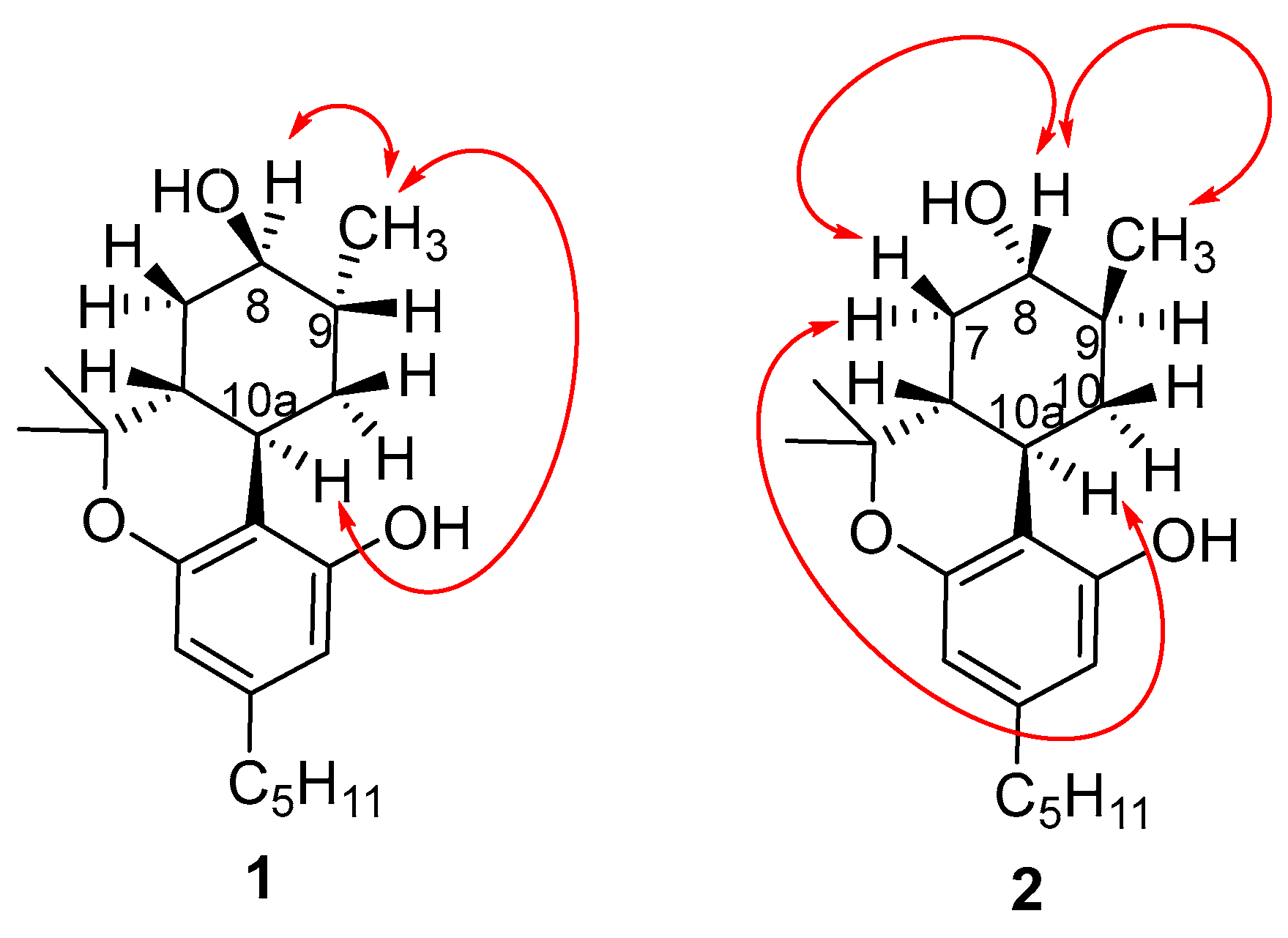

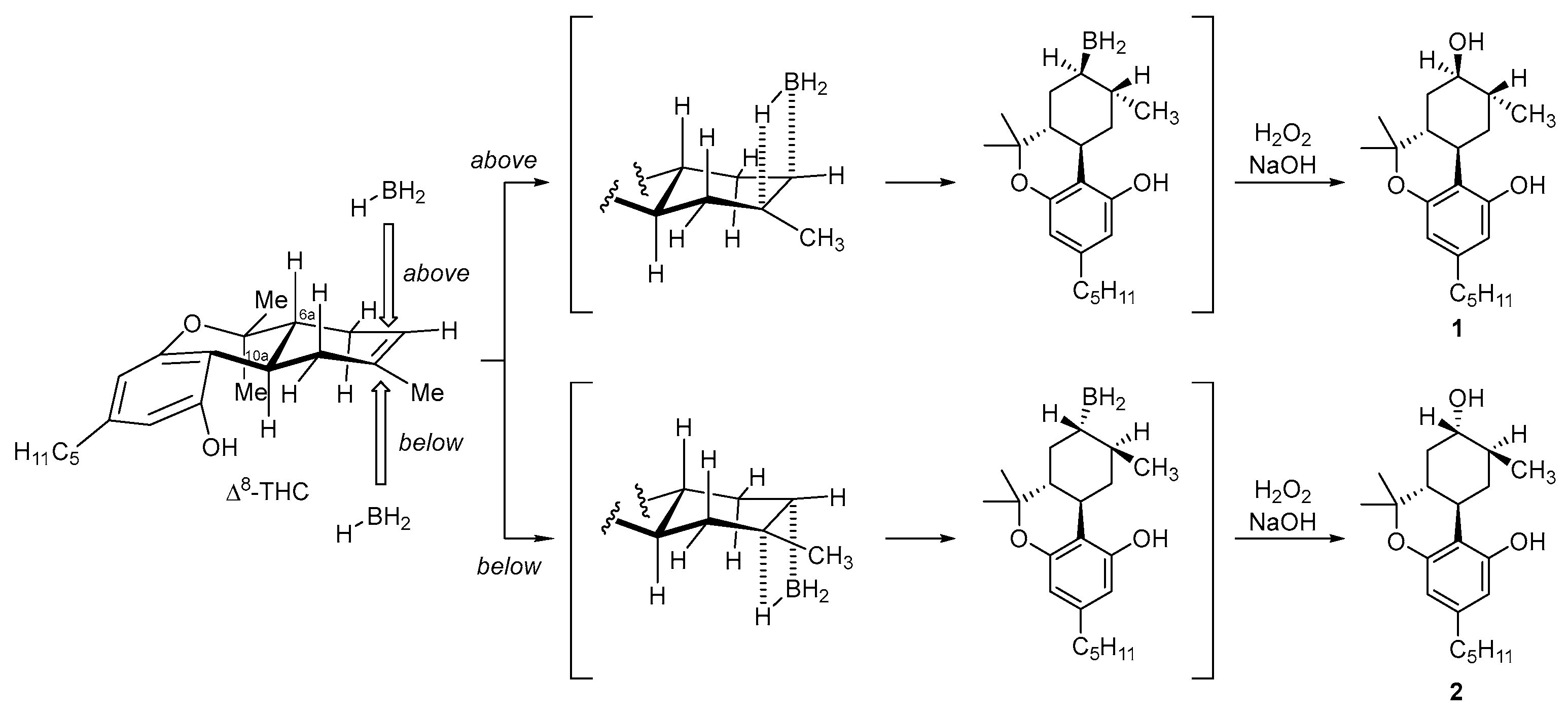

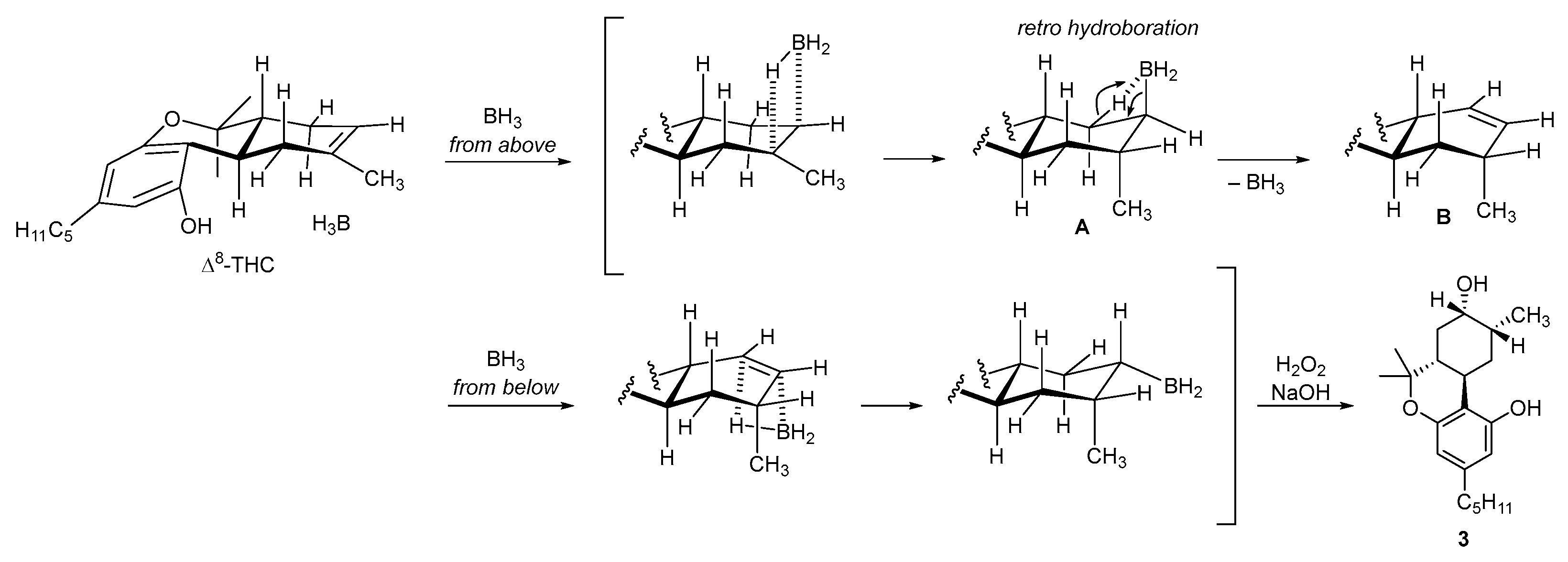

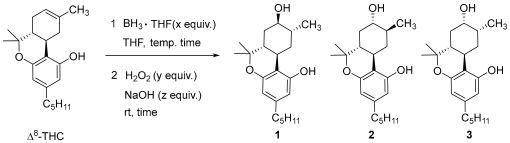

2.1. Synthesis of (8R)OH-(6aR,9R,10aR)-HHC (1) and (8S)OH-(6aR,9S,10aR)-HHC (2)

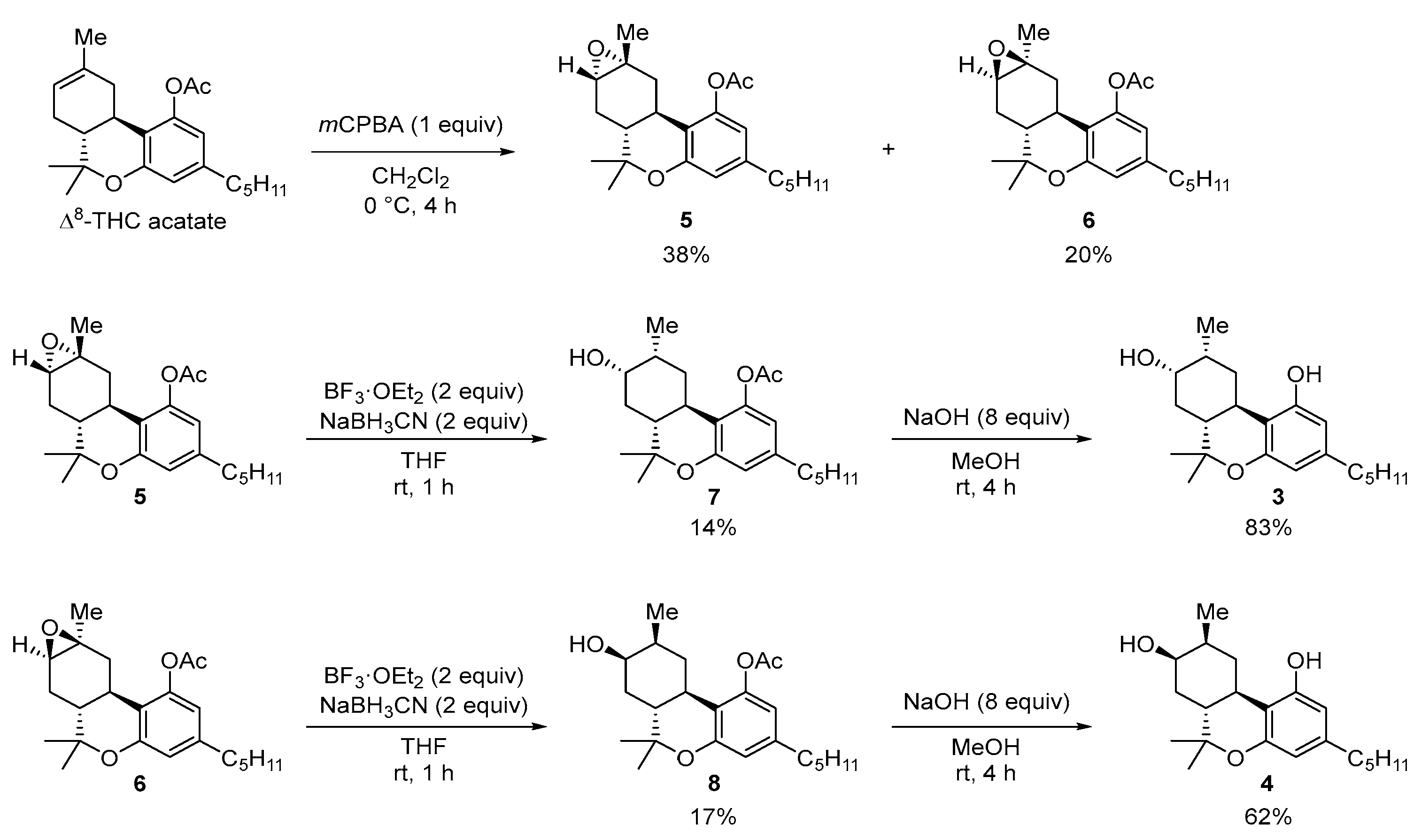

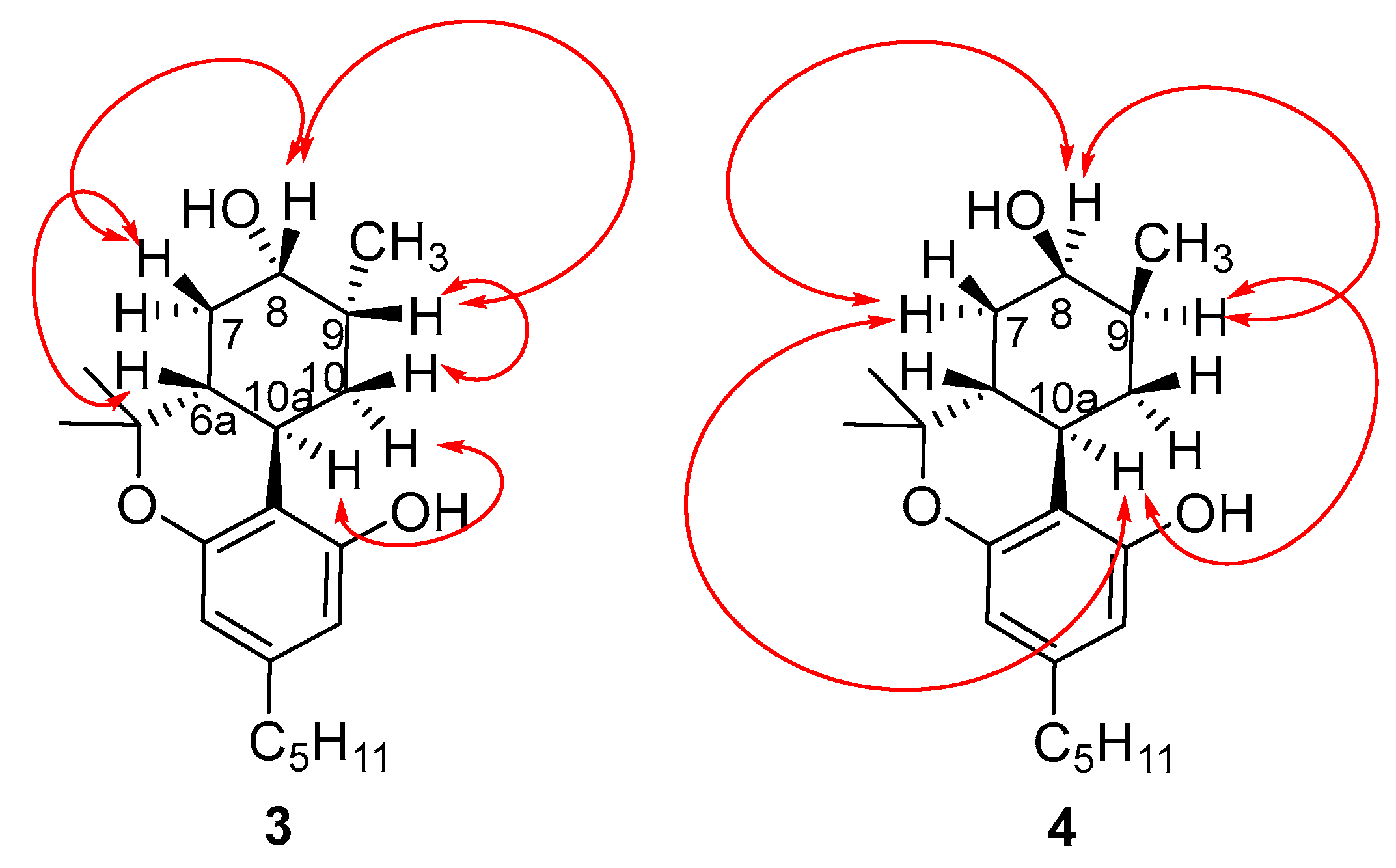

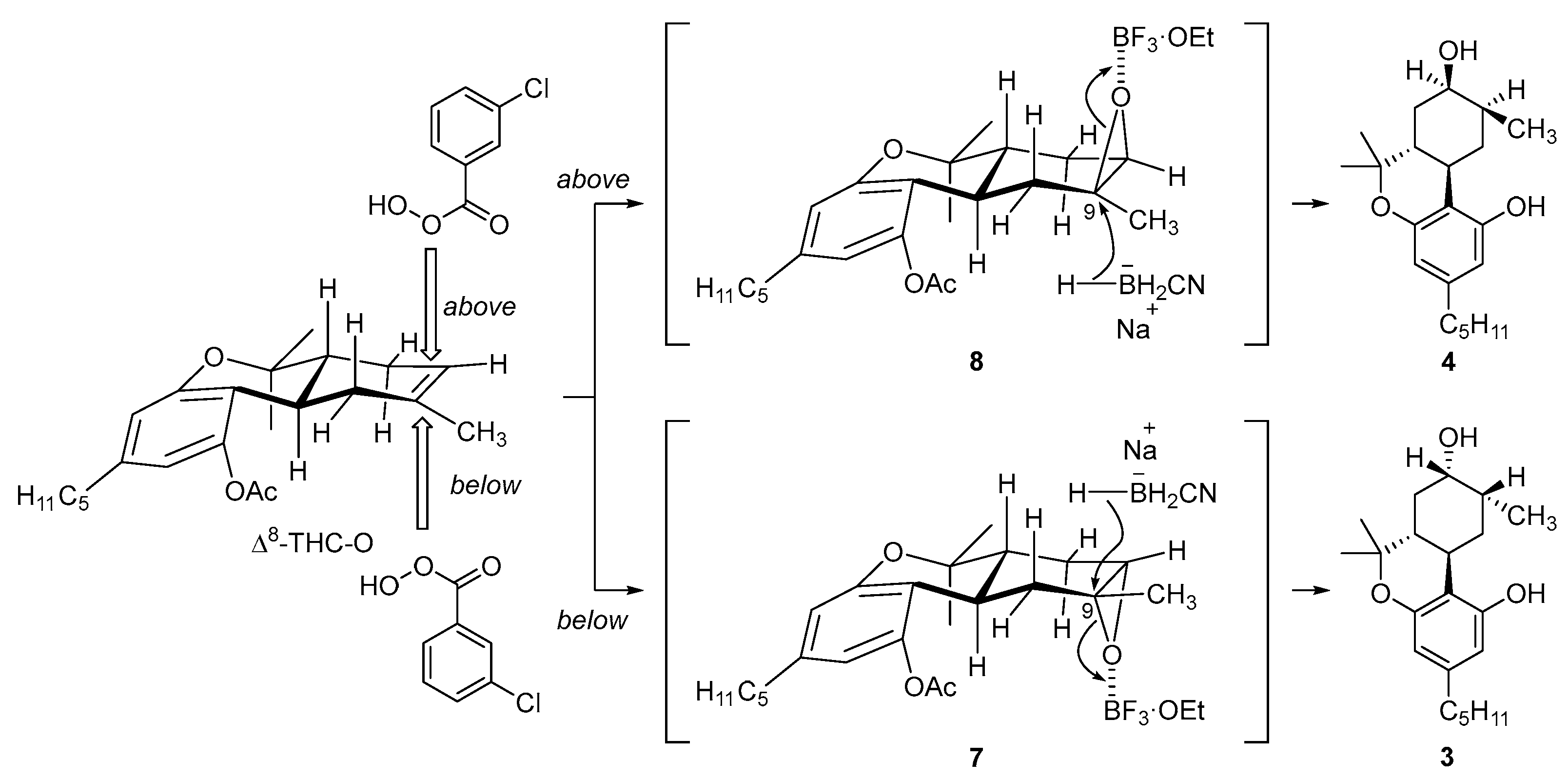

2.2. Synthesis of (8S)OH-(6aR,9R,10aR)-HHC (3), (8R)OH-(6aR,9S,10aR)-HHC (4)

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Analysis Information

3.3. Synthesis of 1 and 2

3.4. Synthesis of 5 and 6

3.5. Synthesis of 7

3.6. Synthesis of 8

3.7. Synthesis of 3

3.8. Synthesis of 4

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World Drug Report 2022; World Drug Report; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rock, E.M.; Parker, L.A. Cannabinoids and Neuropsychiatric Disorders; Murillo-Rodriguez, E., Pandi-Perumal, S.R., Monti, J.M., Eds.; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, H.M. Phytocanabinoids and synthetic cannabinoids: From recreational consumption to potential therapeutic use–A review. Front. Toxcol. 2025, 6, 1495547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ujváry, I. Hexahydrocannabinol and closely related semi-synthetic cannabinoids: A comprehensive review. Drug Test. Anal. 2024, 16, 127–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hively, R.L.; Mosher, W.A.; Hoffmann, F.W. Isolation of trans-Δ6-Tetrahydrocannabinol from marijuana. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1966, 88, 1832–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Docampo-Palacios, M.L.; Ramirez, G.A.; Tesfatsion, T.T.; Okhovat, A.; Pittiglio, M.; Ray, K.P.; Cruces, W. Saturated cannabinoids: Update on synthesis strategies and biological studies of these emerging cannabinoid analogs. Molecules 2023, 28, 6434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seccamani, P.; Franco, C.; Protti, S.; Porta, A.; Profumo, A.; Caprioglio, D.; Salamone, S.; Mannucci, B.; Merli, D. Photochemistry of cannabidiol (CBD) revised. A combined preparative and spectrometric investigation. J. Nat. Prod. 2021, 84, 2858–2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, R.; Kikura-Hanajiri, R. Identification of hexahydrocannabinol (HHC), dihydro-iso-tetrahydrocannabinol (dihydro-iso-THC) and hexahydrocannabiphorol (HHCP) in electronic cigarette cartridge products. Forensic Toxicol. 2024, 42, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, D.J.; Brown, N.K. A method based on catalytic hydrogenation for the identification of monohydroxy metabolites of isomeric tetrahydrocannabinols. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 1990, 4, 67–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Trana, A.; Di Giorgi, A.; Sprega, G.; Carlier, J.; Kobidze, G.; Montanari, E.; Taoussi, O.; Bambagiotti, G.; Fede, M.S.; Lo Faro, A.F.; et al. Disposition of hexahydrocannabinol epimers and their metabolites in biological matrices following a single administration of smoked hexahydrocannabinol: A preliminary study. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schirmer, W.; Auwärter, V.; Kaudewitz, J.; Schürch, S.; Weinmann, W. Identification of human hexahydrocannabinol metabolites in urine. Eur. J. Mass Spectrom. Behav. 2023, 29, 326–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindbom, K.; Norman, C.; Baginski, S.; Krebs, L.; Stalberga, D.; Rautio, T.; Wu, X.; Kronstrand, R.; Gréen, H. Human metabolism of the semi-synthetic cannabinoids hexahydrocannabinol, hexahydrocannabiphorol and their acetates using hepatocytes and urine samples. Drug Test. Anal. 2025, 17, 372–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechoulam, R.; Lander, N.; Varkony, T.H.; Kimmel, I.; Becker, O.; Ben-Zvi, Z.; Edery, H.; Porath, G. Stereochemical requirements for cannabinoid activity. J. Med. Chem. 1980, 23, 1068–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechoulam, R.; Braun, P.; Gaoni, Y. Syntheses of Δ1-tetrahydrocannabinol and related cannabinoids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972, 94, 6159–6165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carey, F.A.; Sundberg, R.J. Advanced Organic Chemistry, Part B: Reactions and Synthesis, 4th ed.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 226–232. [Google Scholar]

- Hilario-Martinez, J.C.; Murillo, F.; Garcia-Mendez, J.; Dzib, E.; Sandoval-Ramirez, J.; Munoz-Hernandez, M.A.; Bernes, S.; Kurti, L.; Duarte, F.; Merino, G.; et al. trans-Hydroboration–oxidation products in Δ5-steroids via a hydroboration-retro-hydroboration mechanism. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 12764–12768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dethe, D.H.; Erande, R.D.; Mahapatra, S.; Das, S.; Kumar, B.V. Protecting group free enantiospecific total syntheses of structurally diverse natural products of the tetrahydrocannabinoid family. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 2871–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inayama, S.; Sawa, A.; Hosoya, E. The oxidation of Δ1- and Δ6-tetrahydrocannabinol with selenium dioxide. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1974, 22, 1519–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, I.; Narimatsu, S.; Watanabe, K.; Yoshimura, H. Synthesis of 8α, 9α- and 8β, 9β-epoxyhexahydrocannabinols. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1981, 29, 3378–3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.H.; Hazekamp, A.; Peltenburg-Looman, A.M.G.; Frédérich, M.; Erkelens, C.; Lefeber, A.W.M.; Verpoorte, R. NMR assignments of the major cannabinoids and cannabiflavonoids isolated from flowers of Cannabis sativa. Phytochem. Anal. 2004, 15, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binder, M.; Franke, I.; Schmidt, B.; Dietrich, W. 13C-NMR. Spectra of natural and semi-synthetic cannabinoids. Helv. Chim. Acta 1982, 65, 807–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction 1 | Reaction 2 | |||||||

| Entry | x (Equiv.) | Temp. (°C) | Time (h) | Y (Equiv.) | Z (Equiv.) | Time (h) | 1 (%) | 2 + 3 (%) (Ratio) |

| 1 | 2 | −20 | 2 | 10 | 10 | 1 | 24 | 20 (5:1) |

| 2 | 2 | −10 | 21 | 10 | 10 | 30 | 26 | 34 (4:1) |

| 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 10 | 10 | 15 | 40 | 35 (7:1) |

| 4 | 2 | 0 | 2.5 | >>10 | 10 | 60 | 14 | 25 (5:1) |

| 5 | 2.5 | 0 | 3 | >>10 | >>10 | 15 | 26 | 8 (10:1) |

| 6 | 2.2 | 23 | 4 | >>10 | >>10 | 15 | 15 | 30 (2:1) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ieuji, K.; Nakamura, K.; Takahashi, H. Stereoselective Synthesis and Structural Confirmation of All Four 8-Hydroxyhexahydrocannabinol Stereoisomers. Molecules 2026, 31, 289. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020289

Ieuji K, Nakamura K, Takahashi H. Stereoselective Synthesis and Structural Confirmation of All Four 8-Hydroxyhexahydrocannabinol Stereoisomers. Molecules. 2026; 31(2):289. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020289

Chicago/Turabian StyleIeuji, Kei, Kayo Nakamura, and Hideyo Takahashi. 2026. "Stereoselective Synthesis and Structural Confirmation of All Four 8-Hydroxyhexahydrocannabinol Stereoisomers" Molecules 31, no. 2: 289. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020289

APA StyleIeuji, K., Nakamura, K., & Takahashi, H. (2026). Stereoselective Synthesis and Structural Confirmation of All Four 8-Hydroxyhexahydrocannabinol Stereoisomers. Molecules, 31(2), 289. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020289