Screening for Peptides to Bind and Functionally Inhibit SARS-CoV-2 Fusion Peptide Using Mirrored Combinatorial Phage Display and Human Proteomic Phage Display

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Binding Kinetics Between FP and Selected S-Derived Peptides

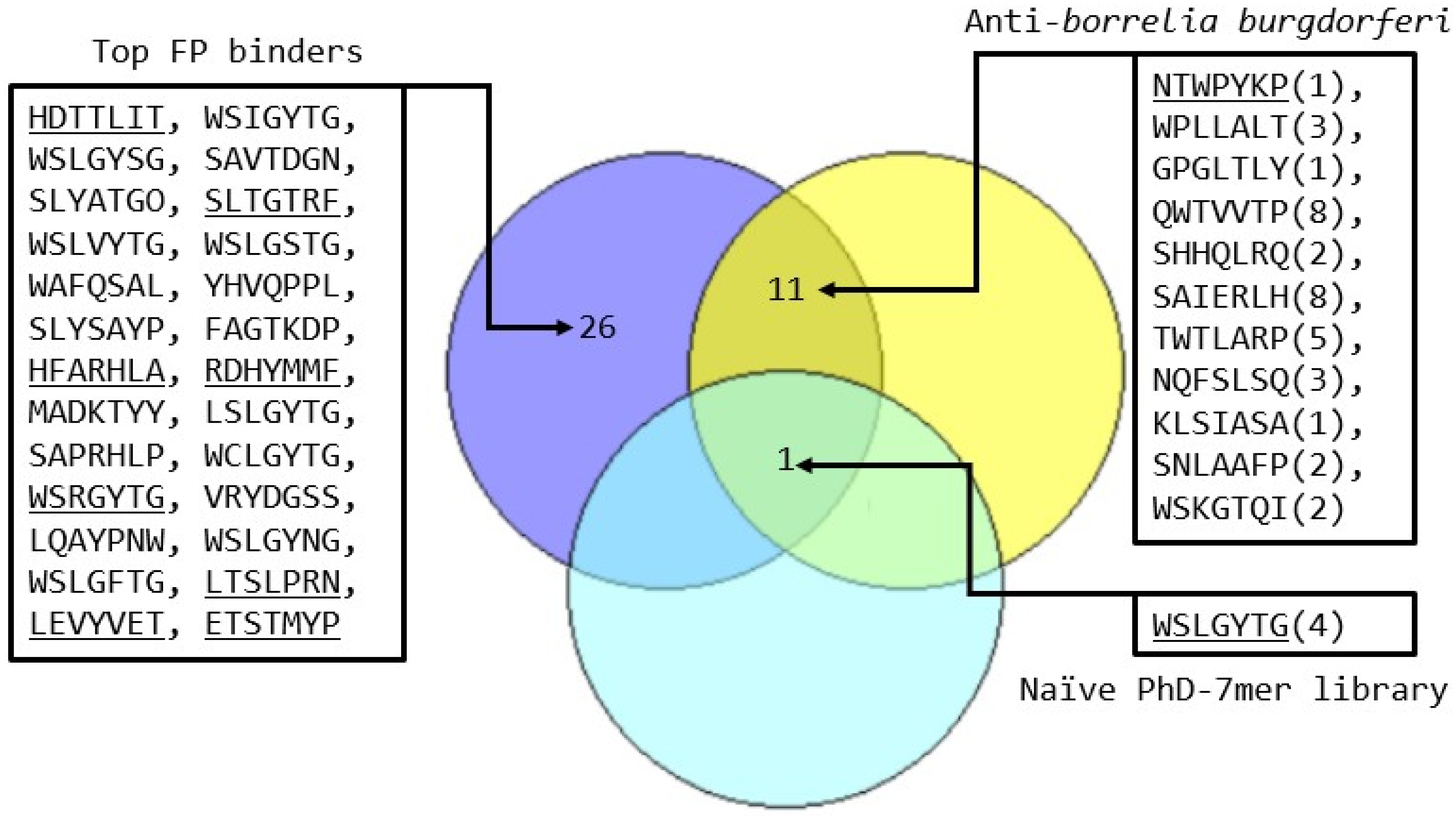

2.2. Identification and Testing of Combinatorial Phage Display Peptides

2.3. Screening Versus the Human Disordered Proteomic Phage Display Library

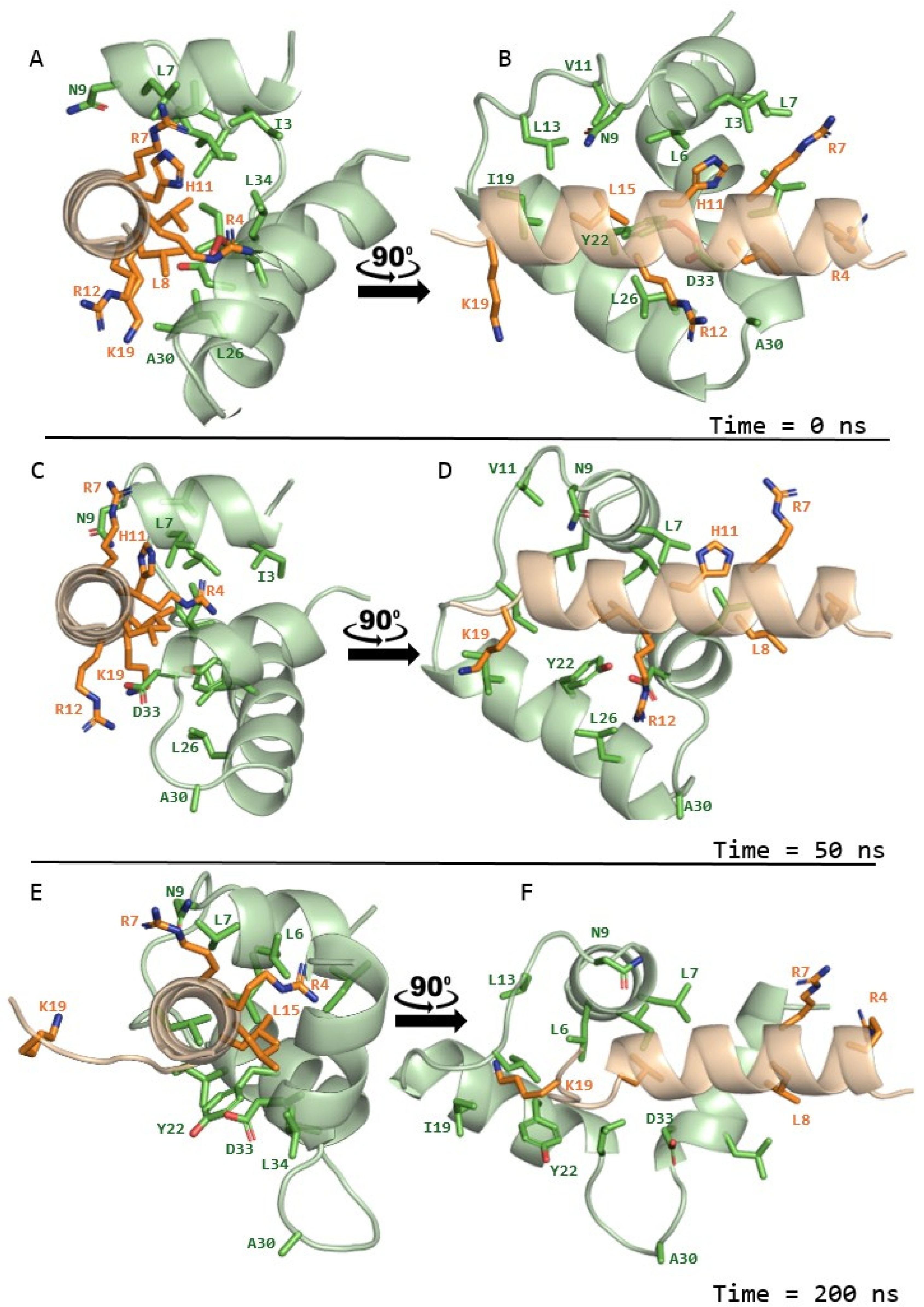

2.4. Structural Modelling of Interactions Between OTUD1 Peptide and FP

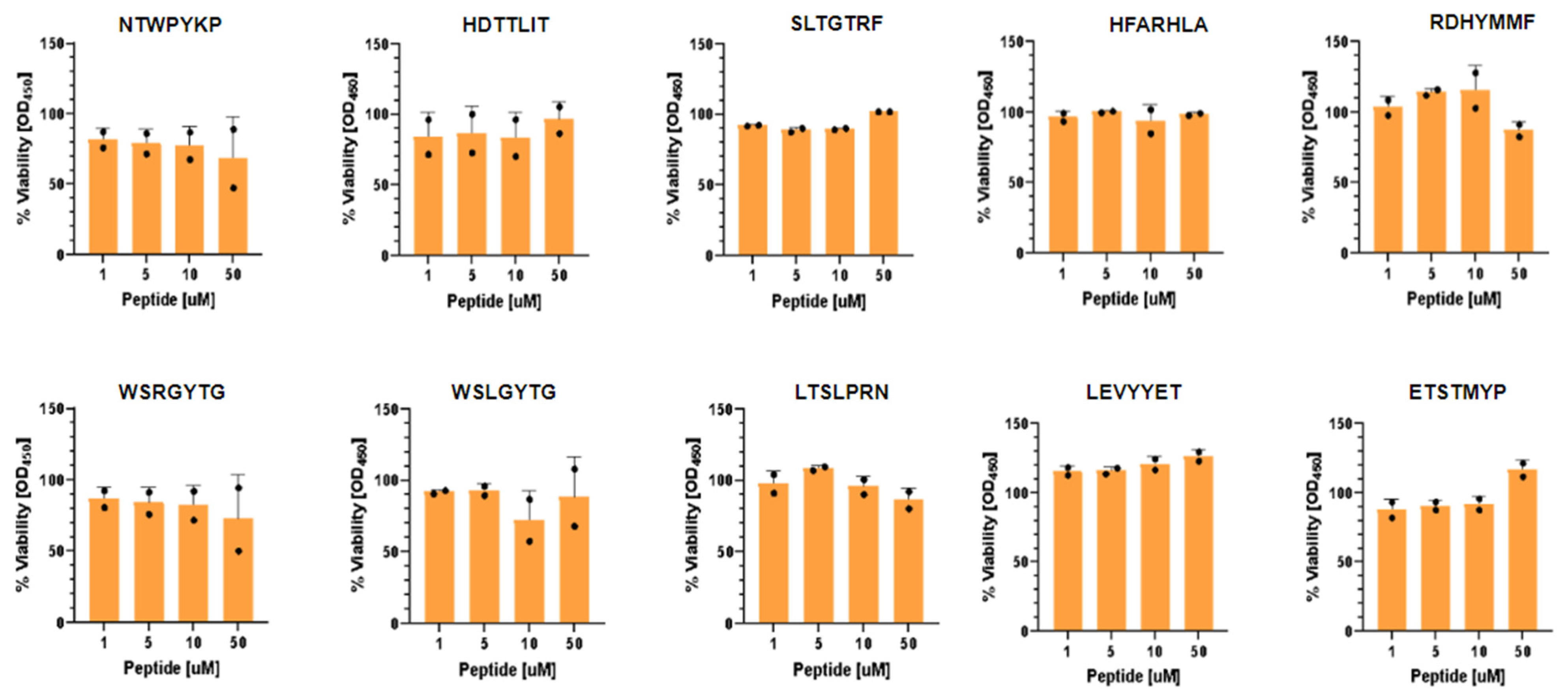

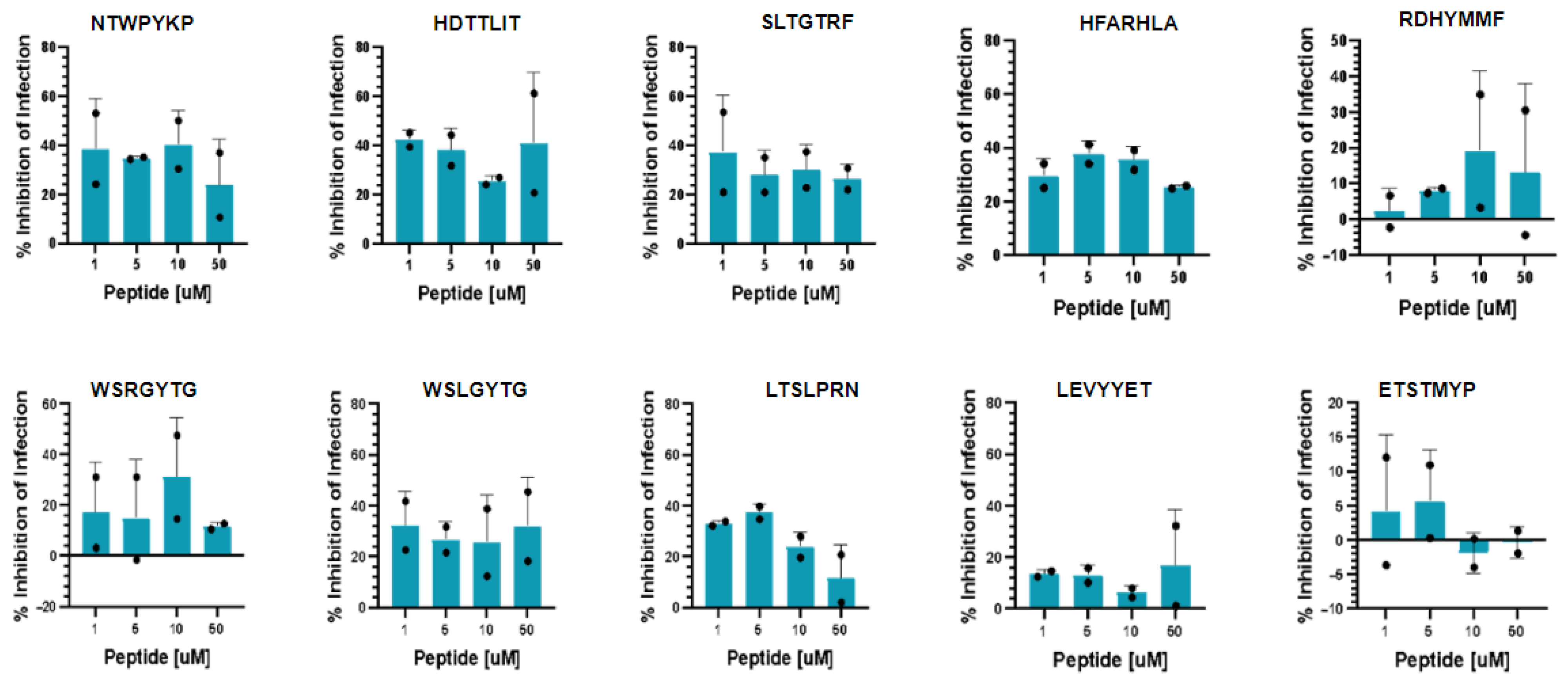

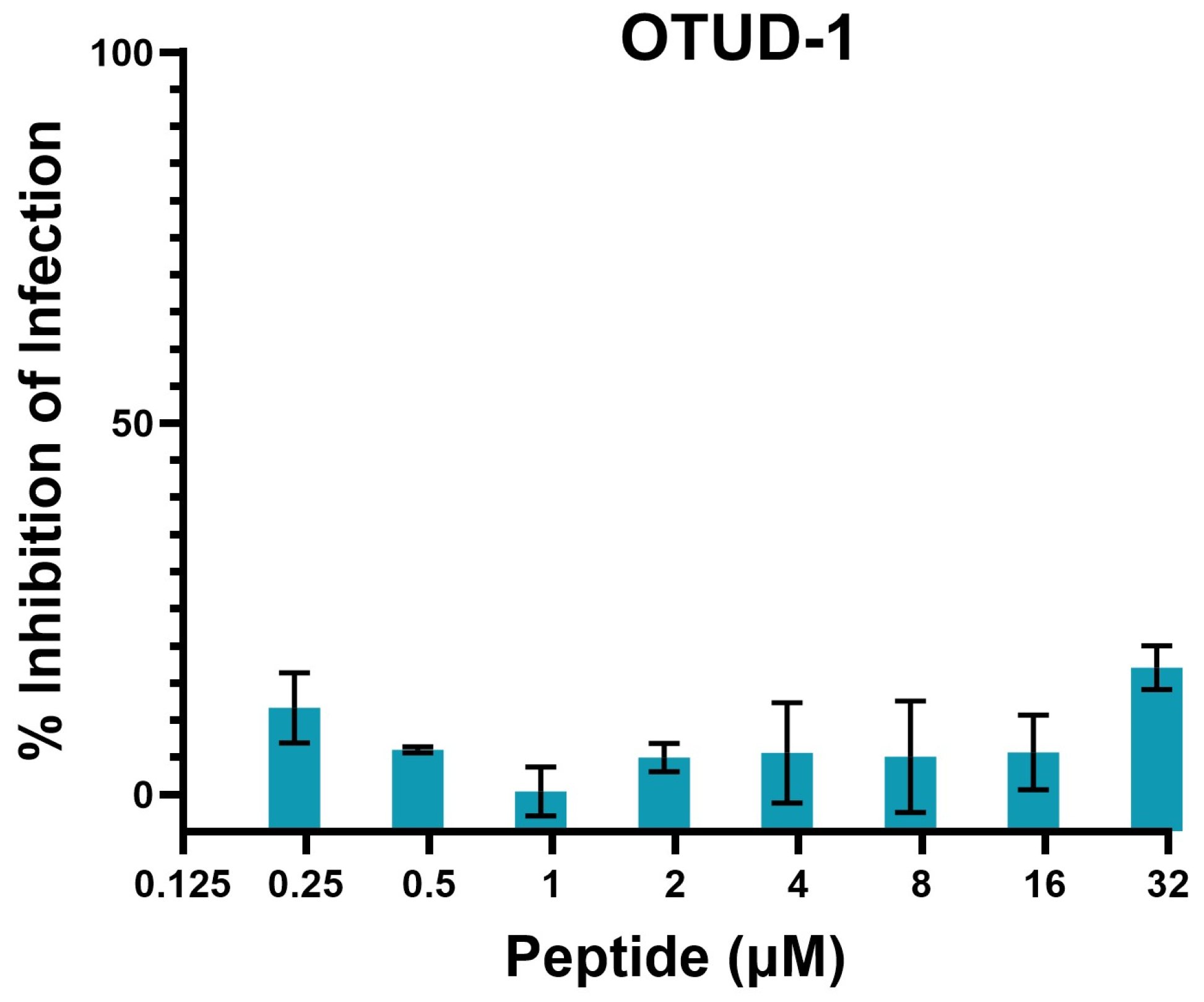

2.5. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Toxicity

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Peptide Synthesis and Characterisation

4.2. Combinatorial NEB PhD Phage Display Screening

4.3. Surface Plasma Resonance

4.4. Proteomic Phage Display

4.5. SARS-CoV-2 Infection Assay and Viability Assay Methods

4.6. Structural Modelling

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FP | Fusion Peptide |

| SPR | Surface Plasmon Resonance |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| -am | Amidation |

| ac- | Acetylation |

| NMR | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| PDB | Protein Database |

| S | Spike Protein |

| nsp3 | Non-structural protein 3 |

| DUB | Deubiquitinase |

| OTUD1 | Ovarian Tumour Deubiquitinase 1 |

| MD | Molecular Dynamics |

References

- Aiello, T.F.; García-Vidal, C.; Soriano, A. Antiviral Drugs against SARS-CoV-2. Rev. Esp. Quimioter. 2022, 35, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.; Hashimoto, K.; Abe, Y.; Kodama, E.N.; Nabika, R.; Oishi, S.; Ohara, S.; Sato, M.; Kawasaki, Y.; Fujii, N.; et al. A Novel Peptide Derived from the Fusion Protein Heptad Repeat Inhibits Replication of Subacute Sclerosing Panencephalitis Virus In Vitro and In Vivo. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0162823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joly, V.; Jidar, K.; Tatay, M.; Yeni, P. Enfuvirtide: From Basic Investigations to Current Clinical Use. Expert. Opin. Pharmacother. 2010, 11, 2701–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yang, C.; Xu, X.-F.; Xu, W.; Liu, S.-W. Structural and Functional Properties of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein: Potential Antivirus Drug Development for COVID-19. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2020, 41, 1141–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zheng, A.; Tang, Y.; Chai, Y.; Chen, J.; Cheng, L.; Hu, Y.; Qu, J.; Lei, W.; Liu, W.J.; et al. A Pan-Coronavirus Peptide Inhibitor Prevents SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Mice by Intranasal Delivery. Sci. China Life Sci. 2023, 66, 2201–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppisetti, R.K.; Fulcher, Y.G.; Van Doren, S.R. Fusion Peptide of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Rearranges into a Wedge Inserted in Bilayered Micelles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 13205–13211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, A.D.; Williamson, M.K.; Lewis, S.; Shoemark, D.; Carroll, M.W.; Heesom, K.J.; Zambon, M.; Ellis, J.; Lewis, P.A.; Hiscox, J.A.; et al. Characterisation of the Transcriptome and Proteome of SARS-CoV-2 Reveals a Cell Passage Induced in-Frame Deletion of the Furin-like Cleavage Site from the Spike Glycoprotein. Genome Med. 2020, 12, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, T.N.; Mayr, L.M.; Minor, D.L.; Milhollen, M.A.; Burgess, M.W.; Kim, P.S. Identification of D-Peptide Ligands through Mirror-Image Phage Display. Science 1996, 271, 1854–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davey, N.E.; Seo, M.-H.; Yadav, V.K.; Jeon, J.; Nim, S.; Krystkowiak, I.; Blikstad, C.; Dong, D.; Markova, N.; Kim, P.M.; et al. Discovery of Short Linear Motif-Mediated Interactions through Phage Display of Intrinsically Disordered Regions of the Human Proteome. FEBS J. 2017, 284, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, T.-Y.; Wu, S.-L.; Chen, J.-C.; Wei, Y.-C.; Cheng, S.-E.; Chang, Y.-H.; Liu, H.-J.; Hsiang, C.-Y. Design and Biological Activities of Novel Inhibitory Peptides for SARS-CoV Spike Protein and Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 Interaction. Antivir. Res. 2006, 69, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madu, I.G.; Belouzard, S.; Whittaker, G.R. SARS-Coronavirus Spike S2 Domain Flanked by Cysteine Residues C822 and C833 Is Important for Activation of Membrane Fusion. Virology 2009, 393, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, H.; Wu, Z. Effect of Disulfide Bridge on the Binding of SARS-CoV-2 Fusion Peptide to Cell Membrane: A Coarse-Grained Study. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 36762–36775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, S.L.; Jung, H.; Hummer, G. Binding of SARS-CoV-2 Fusion Peptide to Host Endosome and Plasma Membrane. J. Phys. Chem. B 2021, 125, 7732–7741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, I.-J.; Kao, C.-L.; Hsieh, S.-C.; Wey, M.-T.; Kan, L.-S.; Wang, W.-K. Identification of a Minimal Peptide Derived from Heptad Repeat (HR) 2 of Spike Protein of SARS-CoV and Combination of HR1-Derived Peptides as Fusion Inhibitors. Antivir. Res. 2009, 81, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badani, H.; Garry, R.F.; Wimley, W.C. Peptide Entry Inhibitors of Enveloped Viruses: The Importance of Interfacial Hydrophobicity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1838, 2180–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillén, J.; Pérez-Berná, A.J.; Moreno, M.R.; Villalaín, J. Identification of the Membrane-Active Regions of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Spike Membrane Glycoprotein Using a 16/18-Mer Peptide Scan: Implications for the Viral Fusion Mechanism. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 1743–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sell, D.K.; Sloth, A.B.; Bakhshinejad, B.; Kjaer, A. A White Plaque, Associated with Genomic Deletion, Derived from M13KE-Based Peptide Library Is Enriched in a Target-Unrelated Manner during Phage Display Biopanning Due to Propagation Advantage. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matochko, W.L.; Chu, K.; Jin, B.; Lee, S.W.; Whitesides, G.M.; Derda, R. Deep Sequencing Analysis of Phage Libraries Using Illumina Platform. Methods 2012, 58, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ionov, Y.; Rogovskyy, A.S. Comparison of Motif-Based and Whole-Unique-Sequence-Based Analyses of Phage Display Library Datasets Generated by Biopanning of Anti-Borrelia Burgdorferi Immune Sera. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0226378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoofnagle, A.N.; Whiteaker, J.R.; Carr, S.A.; Kuhn, E.; Liu, T.; Massoni, S.A.; Thomas, S.N.; Townsend, R.R.; Zimmerman, L.J.; Boja, E.; et al. Recommendations for the Generation, Quantification, Storage, and Handling of Peptides Used for Mass Spectrometry-Based Assays. Clin. Chem. 2016, 62, 48–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, C.; Ali, M.; Krystkowiak, I.; Simonetti, L.; Sayadi, A.; Mihalic, F.; Kliche, J.; Andersson, E.; Jemth, P.; Davey, N.E.; et al. Proteome-scale Mapping of Binding Sites in the Unstructured Regions of the Human Proteome. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2022, 18, e10584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoddard, C.I.; Galloway, J.; Chu, H.Y.; Shipley, M.M.; Sung, K.; Itell, H.L.; Wolf, C.R.; Logue, J.K.; Magedson, A.; Garrett, M.E.; et al. Epitope Profiling Reveals Binding Signatures of SARS-CoV-2 Immune Response in Natural Infection and Cross-Reactivity with Endemic Human CoVs. Cell Rep. 2021, 35, 109164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Pustovalova, Y.; Shi, W.; Gorbatyuk, O.; Sreeramulu, S.; Schwalbe, H.; Hoch, J.C.; Hao, B. Crystal Structure of the CoV-Y Domain of SARS-CoV-2 Nonstructural Protein 3. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate Structure Prediction of Biomolecular Interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, A.C.; Laskowski, R.A.; Thornton, J.M. LIGPLOT: A Program to Generate Schematic Diagrams of Protein-Ligand Interactions. Protein Eng. 1995, 8, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossel, E.C.; Huang, C.; Narayanan, K.; Makino, S.; Tesh, R.B.; Peters, C.J. Exogenous ACE2 Expression Allows Refractory Cell Lines To Support Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Replication. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 3846–3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogando, N.S.; Dalebout, T.J.; Zevenhoven-Dobbe, J.C.; Limpens, R.W.A.L.; van der Meer, Y.; Caly, L.; Druce, J.; de Vries, J.J.C.; Kikkert, M.; Bárcena, M.; et al. SARS-Coronavirus-2 Replication in Vero E6 Cells: Replication Kinetics, Rapid Adaptation and Cytopathology. J. Gen. Virol. 2020, 101, 925–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, M.; Lan, Q.; Xu, W.; Wu, Y.; Ying, T.; Liu, S.; Shi, Z.; Jiang, S.; et al. Fusion Mechanism of 2019-nCoV and Fusion Inhibitors Targeting HR1 Domain in Spike Protein. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2020, 17, 765–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, B.J.; Martina, B.E.E.; van der Zee, R.; Lepault, J.; Haijema, B.J.; Versluis, C.; Heck, A.J.R.; de Groot, R.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; Rottier, P.J.M. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (SARS-CoV) Infection Inhibition Using Spike Protein Heptad Repeat-Derived Peptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 8455–8460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, L.; Xu, X.; Xu, W.; Liu, Z.; Shen, X.; Zhou, J.; Xu, L.; Pu, J.; Yang, C.; Huang, Y.; et al. A Five-Helix-Based SARS-CoV-2 Fusion Inhibitor Targeting Heptad Repeat 2 Domain against SARS-CoV-2 and Its Variants of Concern. Viruses 2022, 14, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dacon, C.; Tucker, C.; Peng, L.; Lee, C.-C.D.; Lin, T.-H.; Yuan, M.; Cong, Y.; Wang, L.; Purser, L.; Williams, J.K.; et al. Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies Target the Coronavirus Fusion Peptide. Science 2022, 377, 728–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, G.; Zhu, L.; Li, G.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Pan, J.; Lv, H. An Integrated View of Deubiquitinating Enzymes Involved in Type I Interferon Signaling, Host Defense and Antiviral Activities. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 742542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-Y.; Whalley, J.P.; Knight, J.C.; Wicker, L.S.; Todd, J.A.; Ferreira, R.C. SARS-CoV-2 Infection Induces a Long-Lived pro-Inflammatory Transcriptional Profile. Genome Med. 2023, 15, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsaadi, E.A.J.; Neuman, B.W.; Jones, I.M.; Alsaadi, E.A.J.; Neuman, B.W.; Jones, I.M. A Fusion Peptide in the Spike Protein of MERS Coronavirus. Viruses 2019, 11, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, E.; Buckley, V.; Moman, E.; Coleman, L.; Meade, G.; Kenny, D.; Devocelle, M. Inhibition of Platelet Adhesion by Peptidomimetics Mimicking the Interactive β-Hairpin of Glycoprotein Ibα. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 3323–3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, M.E.; Sidhu, S.S. Chapter Fifteen—Engineering and Analysis of Peptide-Recognition Domain Specificities by Phage Display and Deep Sequencing. In Methods in Enzymology; Keating, A.E., Ed.; Methods in Protein Design; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013; Volume 523, pp. 327–349. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama, S.; Nao, N.; Shirato, K.; Kawase, M.; Saito, S.; Takayama, I.; Nagata, N.; Sekizuka, T.; Katoh, H.; Kato, F.; et al. Enhanced Isolation of SARS-CoV-2 by TMPRSS2-Expressing Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 7001–7003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nao, N.; Sato, K.; Yamagishi, J.; Tahara, M.; Nakatsu, Y.; Seki, F.; Katoh, H.; Ohnuma, A.; Shirogane, Y.; Hayashi, M.; et al. Consensus and Variations in Cell Line Specificity among Human Metapneumovirus Strains. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0215822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Reilly, S.; Kenny, G.; Alrawahneh, T.; Francois, N.; Gu, L.; Angeliadis, M.; d’Autume, V.d.M.; Leon, A.G.; Feeney, E.R.; Yousif, O.; et al. Development of a Novel Medium Throughput Flow-Cytometry Based Micro-Neutralisation Test for SARS-CoV-2 with Applications in Clinical Vaccine Trials and Antibody Screening. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0294262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.; Kim, T.; Iyer, V.G.; Im, W. CHARMM-GUI: A Web-Based Graphical User Interface for CHARMM. J. Comput. Chem. 2008, 29, 1859–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Cheng, X.; Jo, S.; MacKerell, A.D.; Klauda, J.B.; Im, W. CHARMM-GUI Input Generator for NAMD, Gromacs, Amber, Openmm, and CHARMM/OpenMM Simulations Using the CHARMM36 Additive Force Field. Biophys. J. 2016, 110, 641a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandrunen, R.; Vanderspoel, D.; Berendsen, H. Gromacs-a Software Package and a Parallel Computer for Molecular-Dynamics. In Abstracts of Papers of the American Chemical Society; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; Volume 209, p. 49–COMP. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Rauscher, S.; Nawrocki, G.; Ran, T.; Feig, M.; de Groot, B.L.; Grubmüller, H.; MacKerell, A.D. CHARMM36m: An Improved Force Field for Folded and Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Region of S | Residues | Sequence | Related Peptide |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heptad repeat | 936–957 * | ac-DSLSSC(chol)ASALGKLADVVNQNAQ-am | HR [14] |

| Membrane embedding regions | 788–806 | IYKTPPIKDFGGFNFSQIL-am | WWI [15] |

| 891–906 | GAALQIPFAMQMAYRF-am | IFP-WWII-R1[16] | |

| 1095–1110 | FVSNGTHWFVTQRNFY-am | IFP-WWII-R2 [16] |

| Sequence | Read Count | Occurrence in an Unrelated Screen [19] |

|---|---|---|

| WSLGYTG | 6,280,489 | 4 |

| NTWPYKP | 264,257 | 1 |

| HDTTLIT | 169,773 | - |

| SLTGTRF | 11,170 | - |

| RDHYMMF | 7135 | - |

| HFARHLA | 7063 | - |

| LTSLPRN | 4284 | - |

| WSRGYTG * | 3676 | - |

| LEVYYET | 3570 | - |

| ETSTMYP | 3552 | - |

| Gene Name | Protein Name | Peptide | Count | % Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFAP73 | Cilia- and flagella-associated protein 73 | QLEHVKLFMQDLSAML | 4673 | 9.07 |

| OTUD1 | OTU domain-containing protein 1 | GPDRNFRLSEHRQALA | 3393 | 6.59 |

| CFAP65 | Cilia- and flagella-associated protein 65 | DTLLPTQQAEVLHPVV | 1392 | 2.70 |

| DBP | D site-binding protein | TLPFGDVEYVDLDAFL | 148 | 0.29 |

| ACACB | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase 2 | GSSYAEMEVMKMIMTL | 31 | 0.06 |

| MAP1A | Microtubule-associated protein 1A | SFQYADIYEQMMLTGL | 5 | 0.01 |

| MBTPS1 | Membrane-bound transcription factor site-1 protease | HPNIKRVTPQRKVFRS | 3 | 0.01 |

| OTUD1 | OTU domain-containing protein 1 | NFRLSEHRQALAAAKH | 2 | 0.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pal, A.; Roy, N.S.; Angeliadis, M.; Madhu, P.; O’Reilly, S.; Bera, I.; Francois, N.; Lynch, A.; Gautier, V.; Devocelle, M.; et al. Screening for Peptides to Bind and Functionally Inhibit SARS-CoV-2 Fusion Peptide Using Mirrored Combinatorial Phage Display and Human Proteomic Phage Display. Molecules 2026, 31, 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020282

Pal A, Roy NS, Angeliadis M, Madhu P, O’Reilly S, Bera I, Francois N, Lynch A, Gautier V, Devocelle M, et al. Screening for Peptides to Bind and Functionally Inhibit SARS-CoV-2 Fusion Peptide Using Mirrored Combinatorial Phage Display and Human Proteomic Phage Display. Molecules. 2026; 31(2):282. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020282

Chicago/Turabian StylePal, Ajay, Neeladri Sekhar Roy, Matthew Angeliadis, Priyanka Madhu, Sophie O’Reilly, Indrani Bera, Nathan Francois, Aisling Lynch, Virginie Gautier, Marc Devocelle, and et al. 2026. "Screening for Peptides to Bind and Functionally Inhibit SARS-CoV-2 Fusion Peptide Using Mirrored Combinatorial Phage Display and Human Proteomic Phage Display" Molecules 31, no. 2: 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020282

APA StylePal, A., Roy, N. S., Angeliadis, M., Madhu, P., O’Reilly, S., Bera, I., Francois, N., Lynch, A., Gautier, V., Devocelle, M., O’Connell, D. J., & Shields, D. C. (2026). Screening for Peptides to Bind and Functionally Inhibit SARS-CoV-2 Fusion Peptide Using Mirrored Combinatorial Phage Display and Human Proteomic Phage Display. Molecules, 31(2), 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020282