Comparative Expression of Diacylglycerol Acyltransferases for Enhanced Accumulation of Punicic Acid-Enriched Triacylglycerols in Yarrowia lipolytica

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

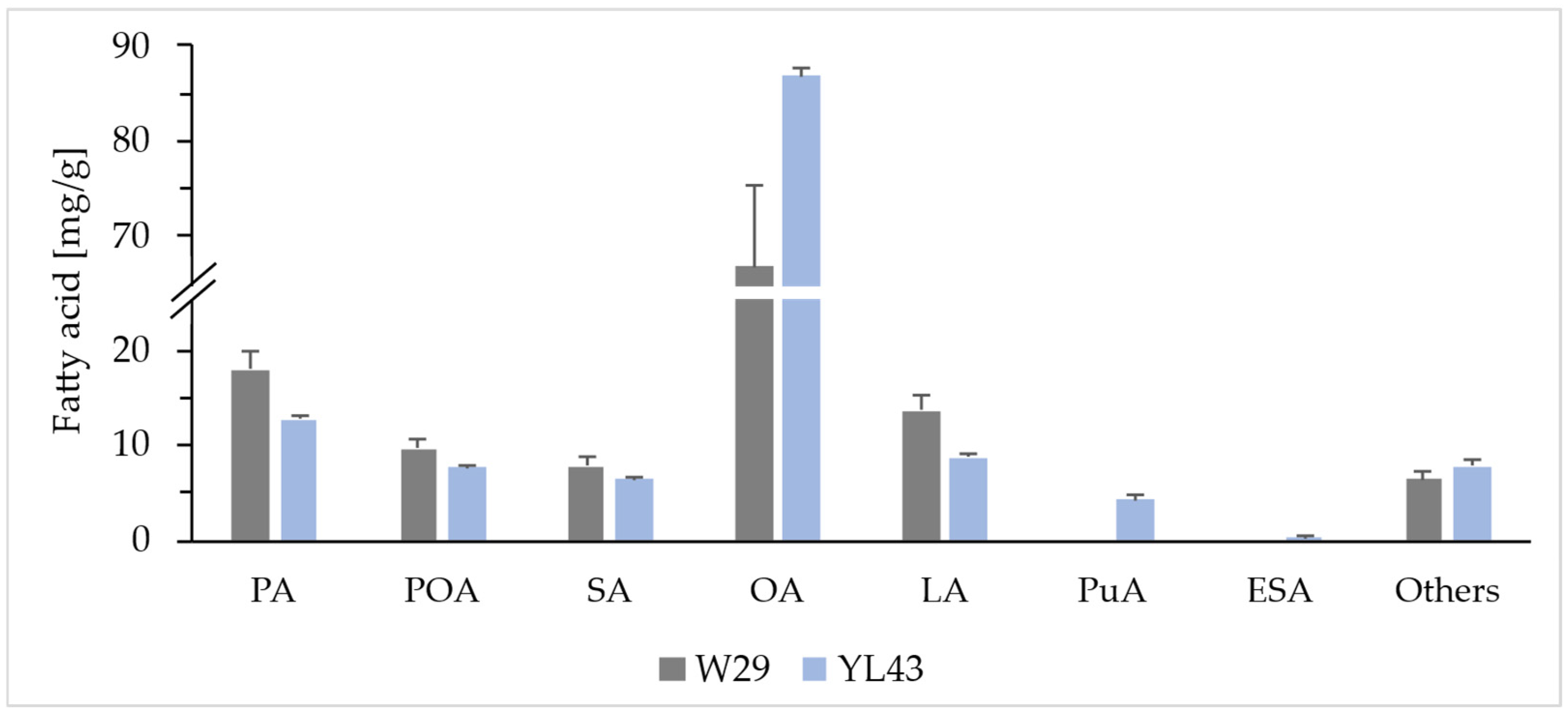

2.1. Overexpression of PgFADX Gene in Yarrowia lipolytica Po1d Derivative Strain

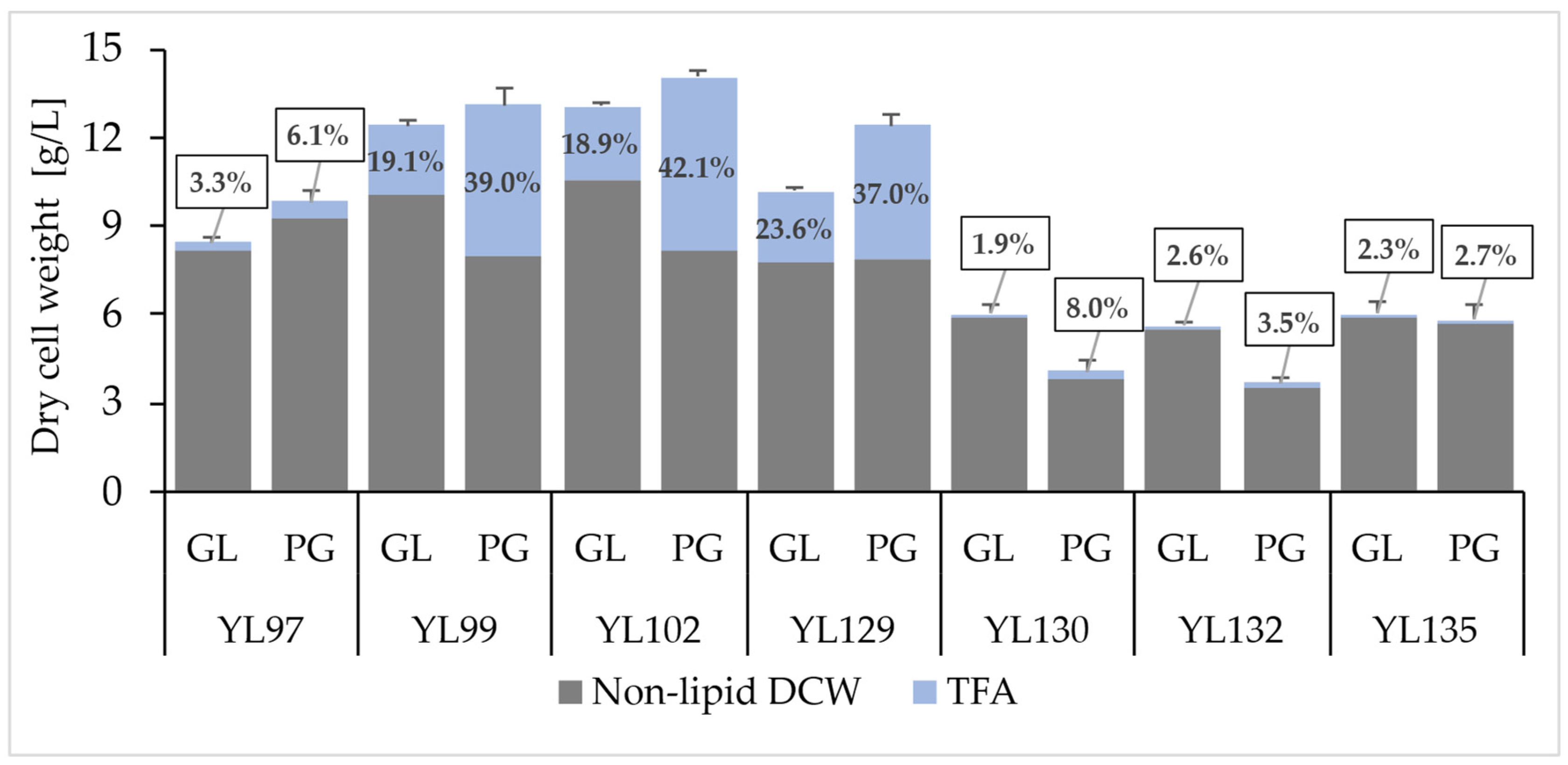

2.2. Monitoring the Effect of the Expression of Different Diacylglycerol Acyltransferase Genes on Punicic Acid Accumulation

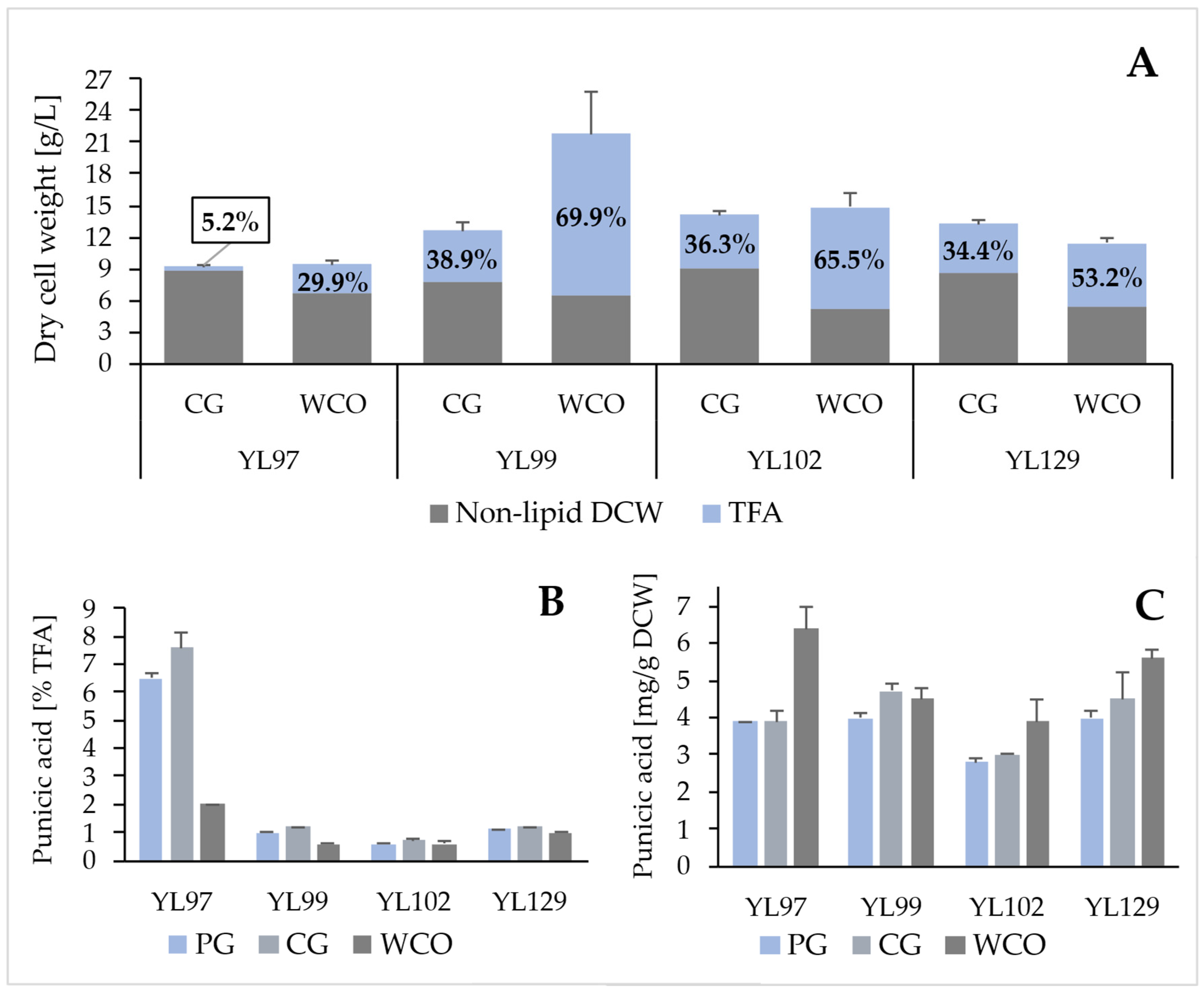

2.3. Punicic Acid Production on Waste Carbon Sources

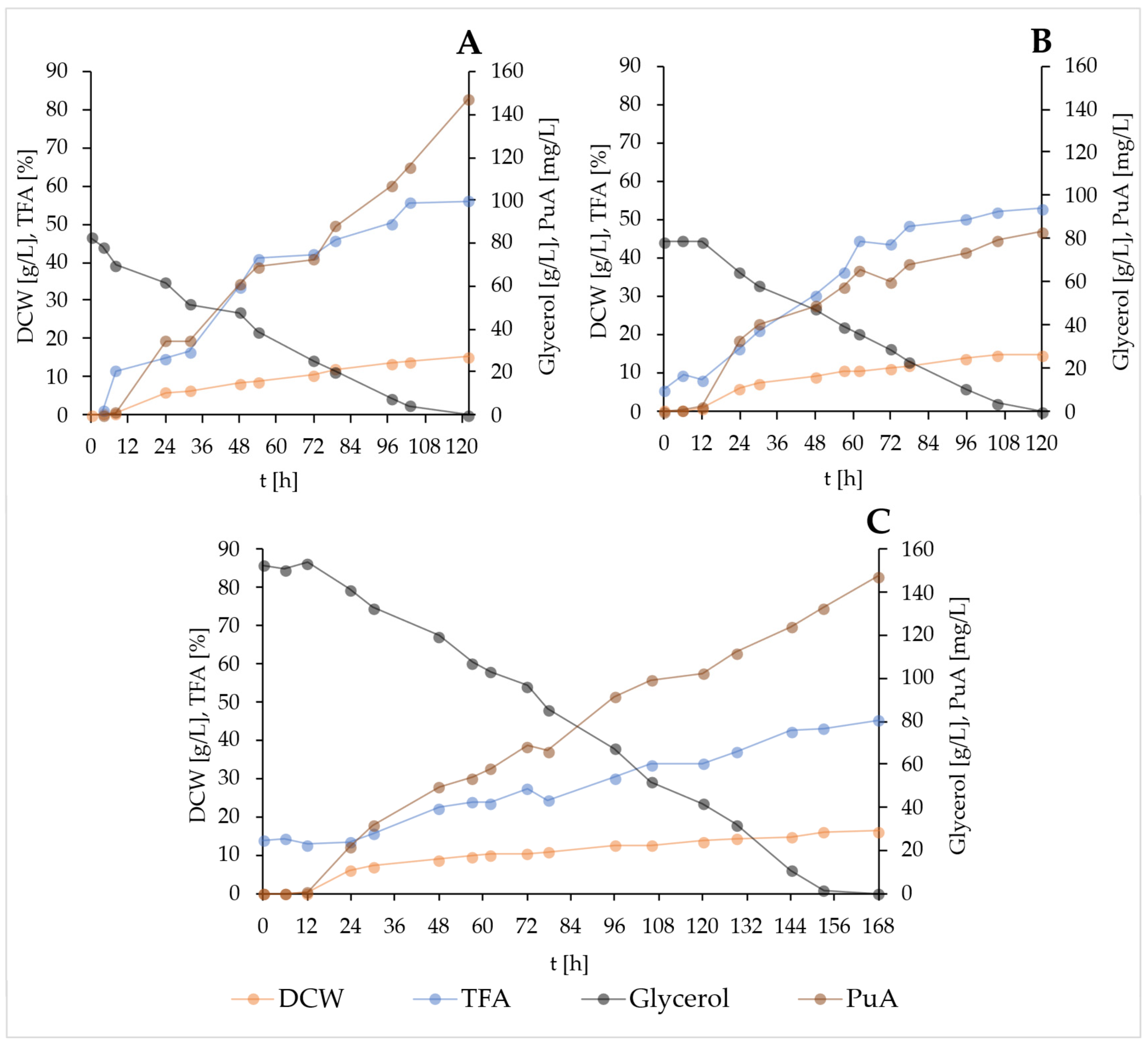

2.4. Crude Glycerol in Scale-Up of Fermentations

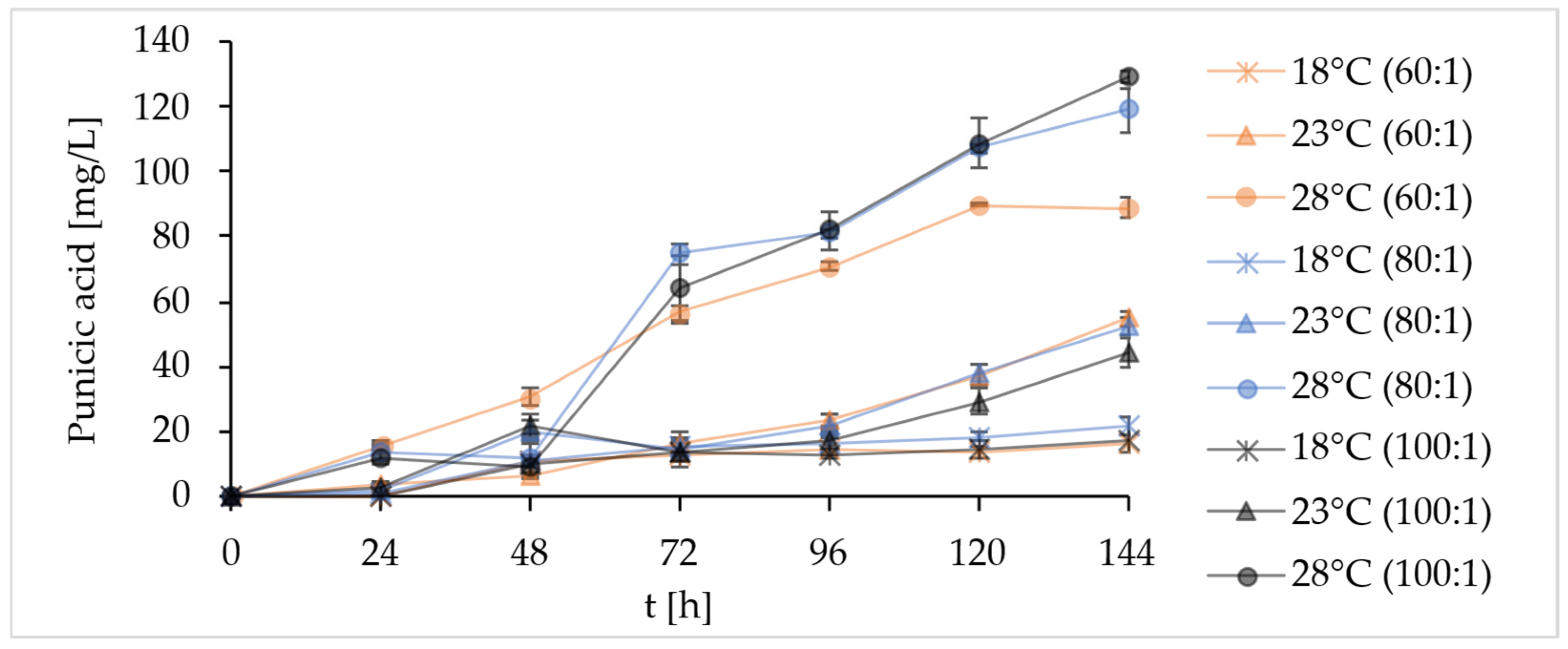

2.4.1. Modification of the Culture Medium and Cultivation Conditions

2.4.2. Scale-Up of Batch Fermentations with the Strain YL129 in Bioreactor

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Culture Conditions

3.2. Plasmid and Strain Construction

| Strain | Plasmid/Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| JME1868 | 4,5 kb sequence of LEU2 gene | [3] |

| EC69 | pUC57 PgFADX | Generay Biotech |

| EC72 | JMP62 pTEF1-PgFADX::LEU2ex | This study |

| EC78 | JMP62 8UAS-pTEF1-PgFADX::LEU2ex | This study |

| EC80 | JMP62 8UAS-pTEF1-PgFADX::URA3ex | This study |

| EC98 | pUC57 PgPDAT | GenScript Biotech |

| EC100 | pUC57 PgDGAT1 | GenScript Biotech |

| EC102 | pUC57 PgDGAT2 | GenScript Biotech |

| EC104 | pUC57 PgDGAT3 | GenScript Biotech |

| EC138 | JMP62 pTEF1-PgDGAT1::URA3ex | This study |

| EC140 | JMP62 pTEF1-PgDGAT2::URA3ex | This study |

| EC141 | JMP62 pTEF1-PgDGAT3::URA3ex | This study |

| EC143 | JMP62 pTEF1-PgPDAT::URA3ex | This study |

| Y. lipolytica | ||

| W29 | MATA, wild type | ATCC24060 |

| Po1d | MATA leu2-270 ura3-302 xpr2-322 | [56] |

| JMY1877 (Q4) | Po1d Δdga1 Δlro1 Δare1 Δdga2 | [12] |

| JMY1882 | Q4 pTEF-YlLRO1::URA3ex | [12] |

| JMY1884 | Q4 pTEF-YlDGA2::URA3ex | [12] |

| JMY1892 | Q4 pTEF-YlDGA1::URA3ex | [12] |

| YL43 | Po1d 8UAS-pTEF1-PgFADX::URA3ex LEU2 | This study |

| YL45 | Po1d pTEF1-PgFADX::URA3ex LEU2 | This study |

| YL94 | Q4 8UAS-pTEF1-PgFADX::LEU2ex | This study |

| YL97 | JMY1882 8UAS-pTEF1-PgFADX::LEU2ex | This study |

| YL99 | JMY1884 8UAS-pTEF1-PgFADX::LEU2ex | This study |

| YL102 | JMY1892 8UAS-pTEF1-PgFADX::LEU2ex | This study |

| YL129 | YL94 pTEF1-PgDGAT1::URA3ex | This study |

| YL130 | YL94 pTEF1-PgDGAT2::URA3ex | This study |

| YL132 | YL94 pTEF1-PgDGAT3::URA3ex | This study |

| YL135 | YL94 pTEF1-PgPDAT::URA3ex | This study |

3.3. Analytical Methods

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DAG | Diacylglycerol |

| DCW | Dry cell weight |

| DGAT | Acyl-CoA:diacylglycerol acyltransferase |

| DO | Dissolved oxygen |

| ESA | α-eleostearic acid |

| FA | Fatty acid |

| LA | Linoleic acid |

| OA | Oleic acid |

| PA | Palmitic acid |

| PDAT | Phospholipid:diacylglycerol acyltransferase |

| POA | Palmitoleic acid |

| PSO | Pomegranate seed oil |

| PuA | Punicic acid |

| TAG | Triacylglycerol |

| TFA | Total fatty acids |

| WCO | Waste cooking oil |

References

- Almoraie, M.; Spencer, J.; Wagstaff, C. Fatty Acid Profile, Tocopherol Content, and Phenolic Compounds of Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) Seed Oils. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 145, 107788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Zhao, M.; Wang, J.; Faiza, M.; Chen, X.; Cui, J.; Liu, N.; Li, D. A Novel and Efficient Method for Punicic Acid-Enriched Diacylglycerol Preparation: Enzymatic Ethanolysis of Pomegranate Seed Oil Catalyzed by Lipozyme 435. Lebensm.-Wiss. Technol. 2022, 159, 113246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holic, R.; Xu, Y.; Caldo, K.M.P.; Singer, S.D.; Field, C.J.; Weselake, R.J.; Chen, G. Bioactivity and Biotechnological Production of Punicic Acid. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 3537–3549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Haddis, D.Z.; Xiao, Q.; Bressler, D.C.; Chen, G. Engineering Rhodosporidium Toruloides for Sustainable Production of Value-Added Punicic Acid from Glucose and Wood Residues. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 412, 131422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsharawy, H.; Refat, M. Yarrowia lipolytica: A Promising Microbial Platform for Sustainable Squalene Production. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2024, 57, 103130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, M.; Miranda, S.M.; Costa, A.R.; Pereira, A.S.; Belo, I. Yarrowia lipolytica as a Biorefinery Platform for Effluents and Solid Wastes Valorization—Challenges and Opportunities. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2022, 42, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottardi, D.; Siroli, L.; Vannini, L.; Patrignani, F.; Lanciotti, R. Recovery and Valorization of Agri-Food Wastes and by-Products Using the Non-Conventional Yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 115, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q.D.; Nguyen, T.-V.-L.; Tran, T.T.V.; Khatri, Y.; Chandrapala, J.; Truong, T. Single Cell Oils from Oleaginous Yeasts and Metabolic Engineering for Potent Cultivated Lipids: A Review with Food Application Perspectives. Future Foods 2025, 11, 100658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanikova, V.; Park, Y.-K.; Krajciova, D.; Tachekort, M.; Certik, M.; Grigoras, I.; Holic, R.; Nicaud, J.-M.; Gajdos, P. Yarrowia lipolytica as a Platform for Punicic Acid Production. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhou, Y.; Cao, L.; Lin, L.; Ledesma-Amaro, R.; Ji, X.-J. Engineering Yarrowia lipolytica for Sustainable Production of the Pomegranate Seed Oil-Derived Punicic Acid. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 3088–3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Francis, T.; Mietkiewska, E.; Giblin, E.M.; Barton, D.L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Taylor, D.C. Cloning and Characterization of an Acyl-CoA-Dependent Diacylglycerol Acyltransferase 1 (DGAT1) Gene from Tropaeolum majus, and a Study of the Functional Motifs of the DGAT Protein Using Site-Directed Mutagenesis to Modify Enzyme Activity and Oil Content. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2008, 6, 799–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beopoulos, A.; Haddouche, R.; Kabran, P.; Dulermo, T.; Chardot, T.; Nicaud, J.-M. Identification and Characterization of DGA2, an Acyltransferase of the DGAT1 Acyl-CoA:Diacylglycerol Acyltransferase Family in the Oleaginous Yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. New Insights into the Storage Lipid Metabolism of Oleaginous Yeasts. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 93, 1523–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajdoš, P.; Ledesma-Amaro, R.; Nicaud, J.-M.; Čertík, M.; Rossignol, T. Overexpression of Diacylglycerol Acyltransferase in Yarrowia lipolytica Affects Lipid Body Size, Number and Distribution. FEMS Yeast Res. 2016, 16, fow062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajdoš, P.; Nicaud, J.-M.; Rossignol, T.; Čertík, M. Single Cell Oil Production on Molasses by Yarrowia lipolytica Strains Overexpressing DGA2 in Multicopy. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 8065–8074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Harwood, J.L.; Lemieux, M.J.; Stone, S.J.; Weselake, R.J. Acyl-CoA:Diacylglycerol Acyltransferase: Properties, Physiological Roles, Metabolic Engineering and Intentional Control. Prog. Lipid Res. 2022, 88, 101181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Siloto, R.M.P.; Lehner, R.; Stone, S.J.; Weselake, R.J. Acyl-CoA:Diacylglycerol Acyltransferase: Molecular Biology, Biochemistry and Biotechnology. Prog. Lipid Res. 2012, 51, 350–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, H. Identification of the Major Diacylglycerol Acyltransferase mRNA in Mouse Adipocytes and Macrophages. BMC Biochem. 2018, 19, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turchetto-Zolet, A.C.; Maraschin, F.S.; de Morais, G.L.; Cagliari, A.; Andrade, C.M.; Margis-Pinheiro, M.; Margis, R. Evolutionary View of Acyl-CoA Diacylglycerol Acyltransferase (DGAT), a Key Enzyme in Neutral Lipid Biosynthesis. BMC Evol. Biol. 2011, 11, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rani, S.H.; Krishna, T.H.A.; Saha, S.; Negi, A.S.; Rajasekharan, R. Defective in Cuticular Ridges (DCR) of Arabidopsis thaliana, a Gene Associated with Surface Cutin Formation, Encodes a Soluble Diacylglycerol Acyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 38337–38347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Shockey, J.M.; Klasson, K.T.; Chapital, D.C.; Mason, C.B.; Scheffler, B.E. Developmental Regulation of Diacylglycerol Acyltransferase Family Gene Expression in Tung Tree Tissues. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.-L.; Yu, S.-Y.; Hu, Y.-H. Synergistic Mechanisms of DGAT and PDAT in Shaping Triacylglycerol Diversity: Evolutionary Insights and Metabolic Engineering Strategies. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1598815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zhou, C.; Fan, J.; Shanklin, J.; Xu, C. Mechanisms and Functions of Membrane Lipid Remodeling in Plants. Plant J. 2021, 107, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Li, M.; Ma, D.; Gao, J.; Tao, J.; Meng, J. Identification of Key Genes for Triacylglycerol Biosynthesis and Storage in Herbaceous Peony (Paeonia lactifolra Pall.) Seeds Based on Full-Length Transcriptome. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Yang, T.; Wang, R.; Liu, A. Characterisation of DGAT1 and DGAT2 from Jatropha Curcas and Their Functions in Storage Lipid Biosynthesis. Funct. Plant Biol. FPB 2014, 41, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shockey, J.M.; Gidda, S.K.; Chapital, D.C.; Kuan, J.-C.; Dhanoa, P.K.; Bland, J.M.; Rothstein, S.J.; Mullen, R.T.; Dyer, J.M. Tung Tree DGAT1 and DGAT2 Have Nonredundant Functions in Triacylglycerol Biosynthesis and Are Localized to Different Subdomains of the Endoplasmic Reticulum. Plant Cell 2006, 18, 2294–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marmon, S.; Sturtevant, D.; Herrfurth, C.; Chapman, K.; Stymne, S.; Feussner, I. Two Acyltransferases Contribute Differently to Linolenic Acid Levels in Seed Oil1. Plant Physiol. 2017, 173, 2081–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banaś, W.; Sanchez Garcia, A.; Banaś, A.; Stymne, S. Activities of Acyl-CoA:Diacylglycerol Acyltransferase (DGAT) and Phospholipid:Diacylglycerol Acyltransferase (PDAT) in Microsomal Preparations of Developing Sunflower and Safflower Seeds. Planta 2013, 237, 1627–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajdoš, P.; Urbaníková, V.; Vicenová, M.; Čertík, M. Enhancing Very Long Chain Fatty Acids Production in Yarrowia lipolytica. Microb. Cell Factories 2022, 21, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loukhmas, S.; Kerak, E.; Elgadi, S.; Ettalibi, F.; El Antari, A.; Harrak, H. Oil Content, Fatty Acid Composition, Physicochemical Properties, and Antioxidant Activity of Seed Oils of Ten Moroccan Pomegranate Cultivars. J. Food Qual. 2021, 2021, 6617863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weselake, R.J.; Mietkiewska, E. Gene Combinations for Producing Punicic Acid in Transgenic Plants. U.S. Patent 14/224,582, 25 March 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Xu, Y.; Holic, R.; Yu, X.; Singer, S.D.; Chen, G. Improving the Production of Punicic Acid in Baker’s Yeast by Engineering Genes in Acyl Channeling Processes and Adjusting Precursor Supply. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 9616–9624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsirigka, A.; Theodosiou, E.; Patsios, S.I.; Tsoureki, A.; Andreadelli, A.; Papa, E.; Aggeli, A.; Karabelas, A.J.; Makris, A.M. Novel Evolved Yarrowia lipolytica Strains for Enhanced Growth and Lipid Content under High Concentrations of Crude Glycerol. Microb. Cell Factories 2023, 22, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnuolo, M.; Shabbir Hussain, M.; Gambill, L.; Blenner, M. Alternative Substrate Metabolism in Yarrowia lipolytica. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierzchowska, K.; Derewiaka, D.; Zieniuk, B.; Nowak, D.; Fabiszewska, A. Whey and Post-Frying Oil as Substrates in the Process of Microbial Lipids Obtaining: A Value-Added Product with Nutritional Benefits. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2023, 249, 2675–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierzchowska, K.; Szulc, K.; Zieniuk, B.; Fabiszewska, A. Bioconversion of Liquid and Solid Lipid Waste by Yarrowia lipolytica Yeast: A Study of Extracellular Lipase Biosynthesis and Microbial Lipid Production. Molecules 2025, 30, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, J.M.; Chapital, D.C.; Kuan, J.-C.W.; Mullen, R.T.; Turner, C.; McKeon, T.A.; Pepperman, A.B. Molecular Analysis of a Bifunctional Fatty Acid Conjugase/Desaturase from Tung. Implications for the Evolution of Plant Fatty Acid Diversity. Plant Physiol. 2002, 130, 2027–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brabender, M.; Hussain, M.S.; Rodriguez, G.; Blenner, M.A. Urea and Urine Are a Viable and Cost-Effective Nitrogen Source for Yarrowia lipolytica Biomass and Lipid Accumulation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 2313–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konzock, O.; Zaghen, S.; Fu, J.; Kerkhoven, E.J. Urea Is a Drop-in Nitrogen Source Alternative to Ammonium Sulphate in Yarrowia lipolytica. iScience 2022, 25, 105703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanklin, J.; Guy, J.E.; Mishra, G.; Lindqvist, Y. Desaturases: Emerging Models for Understanding Functional Diversification of Diiron-Containing Enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 18559–18563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindqvist, Y.; Huang, W.; Schneider, G.; Shanklin, J. Crystal Structure of Delta9 Stearoyl-acyl Carrier Protein Desaturase from Castor Seed and Its Relationship to Other Di-iron Proteins. EMBO J. 1996, 15, 4081–4092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwabuchi, M.; Kohno-Murase, J.; Imamura, J. Δ12-Oleate Desaturase-Related Enzymes Associated with Formation of Conjugated Trans-Δ11, Cis-Δ13 Double Bonds. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 4603–4610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bláhová, Z.; Harvey, T.N.; Pšenička, M.; Mráz, J. Assessment of Fatty Acid Desaturase (Fads2) Structure-Function Properties in Fish in the Context of Environmental Adaptations and as a Target for Genetic Engineering. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sestric, R.; Munch, G.; Cicek, N.; Sparling, R.; Levin, D.B. Growth and Neutral Lipid Synthesis by Yarrowia lipolytica on Various Carbon Substrates under Nutrient-Sufficient and Nutrient-Limited Conditions. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 164, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezaki, S.; Iwama, R.; Kobayashi, S.; Shiwa, Y.; Yoshikawa, H.; Ohta, A.; Horiuchi, H.; Fukuda, R. Δ12-Fatty Acid Desaturase Is Involved in Growth at Low Temperature in Yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 488, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobalter, S.; Wriessnegger, T.; Pichler, H. Engineering Yeast for Tailored Fatty Acid Profiles. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 109, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, W.; Zhou, W.; Gong, Z. Co-Valorization of Crude Glycerol and Low-Cost Substrates via Oleaginous Yeasts to Micro-Biodiesel: Status and Outlook. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 180, 113303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaiova, M.; Mietkiewska, E.; Weselake, R.J.; Holic, R. Metabolic Engineering of Schizosaccharomyces pombe to Produce Punicic Acid, a Conjugated Fatty Acid with Nutraceutic Properties. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 7913–7922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornung, E.; Pernstich, C.; Feussner, I. Formation of Conjugated Δ11Δ13-Double Bonds by Δ12-Linoleic Acid (1,4)-Acyl-Lipid-Desaturase in Pomegranate Seeds. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002, 269, 4852–4859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krajciova, D.; Holic, R. The Plasma Membrane H+-ATPase Promoter Driving the Expression of FADX Enables Highly Efficient Production of Punicic Acid in Rhodotorula toruloides Cultivated on Glucose and Crude Glycerol. J. Fungi Basel Switz. 2024, 10, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanikolaou, S.; Diamantopoulou, P.; Blanchard, F.; Lambrinea, E.; Chevalot, I.; Stoforos, N.G.; Rondags, E. Physiological Characterization of a Novel Wild-Type Yarrowia lipolytica Strain Grown on Glycerol: Effects of Cultivation Conditions and Mode on Polyols and Citric Acid Production. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepańczyk, M.; Rzechonek, D.A.; Neuvéglise, C.; Mirończuk, A.M. In-Depth Analysis of Erythrose Reductase Homologs in Yarrowia lipolytica. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vastaroucha, E.-S.; Maina, S.; Michou, S.; Kalantzi, O.; Pateraki, C.; Koutinas, A.A.; Papanikolaou, S. Bioconversions of Biodiesel-Derived Glycerol into Sugar Alcohols by Newly Isolated Wild-Type Yarrowia lipolytica Strains. Reactions 2021, 2, 499–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambrook, J. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-0-87969-577-4. [Google Scholar]

- Nicaud, J.-M.; Madzak, C.; van den Broek, P.; Gysler, C.; Duboc, P.; Niederberger, P.; Gaillardin, C. Protein Expression and Secretion in the Yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. FEMS Yeast Res. 2002, 2, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Dall, M.-T.; Nicaud, J.-M.; Gaillardin, C. Multiple-Copy Integration in the Yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. Curr. Genet. 1994, 26, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barth, G.; Gaillardin, C. Yarrowia lipolytica . In Nonconventional Yeasts in Biotechnology: A Handbook; Wolf, K., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996; pp. 313–388. ISBN 978-3-642-79856-6. [Google Scholar]

- Lazar, Z.; Walczak, E.; Robak, M. Simultaneous Production of Citric Acid and Invertase by Yarrowia lipolytica SUC+ Transformants. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 6982–6989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strain | Carbon Source | Fatty Acid [mg/g DCW] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA | POA | SA | OA | LA | PuA | ESA | Others | ||

| YL97 | GL | 3.5 ± 0.3 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 24.8 ± 2.0 | 6.7 ± 0.6 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 2.5 ± 0.3 |

| PG | 3.6 ± 0.4 | 3.3 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 35.6 ± 1.3 | 10.5 ± 0.0 | 3.9 ± 0.0 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | |

| YL99 | GL | 25.2 ± 2.7 | 10.8 ± 0.8 | 9.9 ± 1.0 | 125 ± 12 | 8.1 ± 0.8 | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 8.8 ± 1.0 |

| PG | 40.9 ± 1.0 | 25.1 ± 0.5 | 24.0 ± 0.6 | 264.0 ± 6.7 | 17.5 ± 0.5 | 4.0 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 13.8 ± 0.5 | |

| YL102 | GL | 14.0 ± 2.3 | 6.4 ± 1.0 | 11.9 ± 1.9 | 85.0 ± 13.5 | 7.9 ± 0.8 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 9.7 ± 1.0 |

| PG | 52 ± 12 | 30.8 ± 7.2 | 56 ± 12 | 265.0 ± 6.2 | 19.0 ± 4.3 | 3.2 ± 0.6 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 23.8 ± 5.5 | |

| YL129 | GL | 24.3 ± 2.7 | 10.6 ± 1.3 | 18.0 ± 0.7 | 151.5 ± 9.4 | 12.4 ± 0.9 | 4.4 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 13.8 ± 1.1 |

| PG | 32.9 ± 1.4 | 15.1 ± 0.5 | 42.8 ± 2.5 | 242.9 ± 4.0 | 14.0 ± 0.1 | 4.0 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 18.0 ± 1.2 | |

| YL130 | GL | 2.6 ± 0.6 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 7.3 ± 1.6 | 4.4 ± 0.9 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 2.1 ± 0.5 |

| PG | 8.9 ± 1.4 | 5.0 ± 0.9 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 24.9 ± 5.1 | 30.0 ± 5.6 | 5.1 ±0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 2.3 ± 0.3 | |

| YL132 | GL | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 8.2 ± 0.1 | 5.5 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 2.4 ± 0.2 |

| PG | 5.2 ± 1.7 | 2.9 ± 1.0 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 13.6 ± 4.5 | 16.0 ± 5.5 | 3.1 ± 0.8 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 2.1 ± 0.7 | |

| YL135 | GL | 3.4 ± 0.0 | 0.9 ± 0.0 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 8.5 ± 0.4 | 5.5 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 2.4 ± 0.2 |

| PG | 1.8 ± 0.9 | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 0.6 ± 0.4 | 8.6 ± 3.2 | 6.5 ± 2.4 | 1.7 ± 0.6 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.5 | |

| Filter Sterilization | Moist Heat Sterilization | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FeSO4·7H2O | MedPG | MedPG + Urea | MedPG | MedPG + Urea | |||

| 20 mg/L | 20 mg/L | 20 mg/L | 20 mg/L | 30 mg/L | 40 mg/L | 50 mg/L | |

| DCW [g/L] | 13.1 ± 0.7 | 13.5 ± 0.1 | 13.4 ± 0.2 | 10.7 ± 0.1 | 9.4 ± 0.4 | 8.5 ± 1.8 | 6.2 ± 1.5 |

| GlyRES [g/L] | 3.4 ± 1.3 | 6.0 ± 1.6 | 3.3 ± 0.7 | 10.4 ± 1.6 | 16.1 ± 1.5 | 16.0 ± 3.9 | 19.3 ± 4.0 |

| TFA [% DCW] | 43.0 ± 1.6 | 41.0 ± 2.4 | 44.2 ± 1.0 | 31.0 ± 2.7 | 33.8 ± 3.0 | 38.5 ± 0.5 | 25.7 ± 5.4 |

| PuA [% TFA] | 1.3 ± 0.7 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.0 | 2.1 ± 0.0 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 2.3 ± 0.1 |

| PuA [mg/g DCW] | 5.5 ± 0.2 | 6.0 ± 0.6 | 5.4 ± 0.5 | 6.7 ± 0.6 | 7.2 ± 0.6 | 7.4 ± 0.8 | 5.8 ± 1.0 |

| PuA [mg/L] | 71.6 ± 1.5 | 80.4 ± 5.7 | 72.2 ± 4.8 | 71.9 ± 6.1 | 67.8 ± 7.1 | 64.1 ± 18.0 | 37 ± 13 |

| Host Organism | Engineering Strategy | Substrate | PuA Production | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y. lipolytica | PgFADX, YlDGA2, GPD1, eyk1Δ, pox1-6Δ, tgl4Δ | Glucose | 36.6 mg/L (shake-flask) | [9] |

| Y. lipolytica | PgFADX, YlFAD2, YlCPT, PgLPCAT, YlLRO1, GPD1, P. graminis Δ9 desaturase, MaELO2, YlELO1, pex10Δ, gut2Δ, lro1Δ, fad2Δ, scdΔ, lip1Δ, scp2Δ | Glucose | 100.56 mg/L (shake-flask) 3072.72 mg/L (bioreactor) | [10] |

| S. cerevisiae | PgFADX | Glucose, galactose, and LA | 1.6% of the TFA (shake-flask) | [48] |

| S. cerevisiae | TkFADX | Galactose and LA | 0.1% of the TFA (shake-flask) | [41] |

| S. cerevisiae | PgFADX | Galactose and LA | 0.8% of the TFA (shake-flask) | [41] |

| S. cerevisiae | PgFADX, PgPDAT, PgLPCAT, snf2Δ | LA | 7.2 mg/L (shake-flask) | [31] |

| S. pombe | PgFADX | Glucose | 38.71 mg/L (shake-flask) | [47] |

| S. pombe | PgFADX, PgFAD2 | Glucose | 34.33 mg/L (shake-flask) | [47] |

| R. toruloides | PgFADX | Glucose | 105.77 mg/L (shake-flask) | [49] |

| R. toruloides | PgFADX | Crude glycerol | 72.81 mg/L (shake-flask) | [49] |

| R. toruloides | PgFADX, PgFAD2 | Glucose | 451.6 mg/L (shake-flask) | [4] |

| R. toruloides | PgFADX, PgFAD2 | Wood hydrolysate | 310 mg/L (shake-flask) | [4] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hambalko, V.; Vevericová, S.; Hambalko, J.; Štefuca, V.; Gajdoš, P.; Čertík, M. Comparative Expression of Diacylglycerol Acyltransferases for Enhanced Accumulation of Punicic Acid-Enriched Triacylglycerols in Yarrowia lipolytica. Molecules 2026, 31, 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020281

Hambalko V, Vevericová S, Hambalko J, Štefuca V, Gajdoš P, Čertík M. Comparative Expression of Diacylglycerol Acyltransferases for Enhanced Accumulation of Punicic Acid-Enriched Triacylglycerols in Yarrowia lipolytica. Molecules. 2026; 31(2):281. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020281

Chicago/Turabian StyleHambalko, Veronika, Simona Vevericová, Jaroslav Hambalko, Vladimír Štefuca, Peter Gajdoš, and Milan Čertík. 2026. "Comparative Expression of Diacylglycerol Acyltransferases for Enhanced Accumulation of Punicic Acid-Enriched Triacylglycerols in Yarrowia lipolytica" Molecules 31, no. 2: 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020281

APA StyleHambalko, V., Vevericová, S., Hambalko, J., Štefuca, V., Gajdoš, P., & Čertík, M. (2026). Comparative Expression of Diacylglycerol Acyltransferases for Enhanced Accumulation of Punicic Acid-Enriched Triacylglycerols in Yarrowia lipolytica. Molecules, 31(2), 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020281