Segmentation and Multimodal Characterization of Metal Particles in the Human Hippocampus Using Discrete Segmentation Algorithms and Correlation Spectral Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Image and Spectral Data

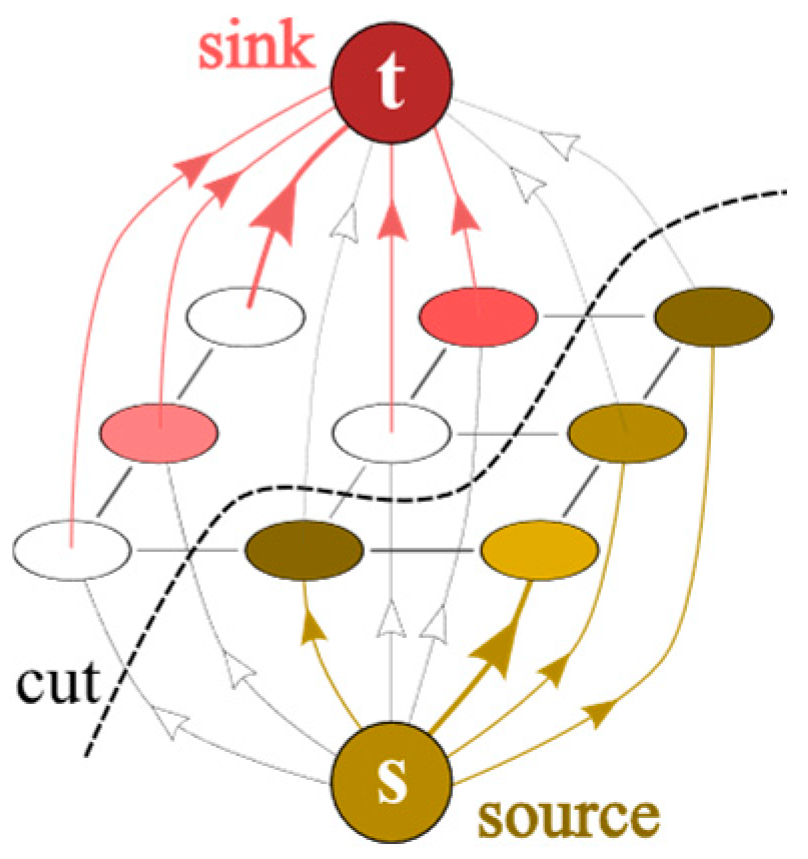

2.2. Image Segmentation Through the Graph-Cut Method

2.2.1. Construction of the Graph for Image Segmentation

2.2.2. Segmentation via Max-Flow/Min-Cut and Dinic’s Algorithm

- Breadth-First Search (BFS): Used to construct a level graph from residual graph. BFS explores the graph layer by layer, identifying the shortest path (in terms of number of edges) from the source to the sink. The level graph contains only edges that go from level i to level i + 1 and only those vertices reachable from the source s.

- Depth-First Search (DFS): Used to find a blocking flow in the level graph. DFS explores as far as possible along each branch before backtracking, pushing the maximum possible flow along identified paths.

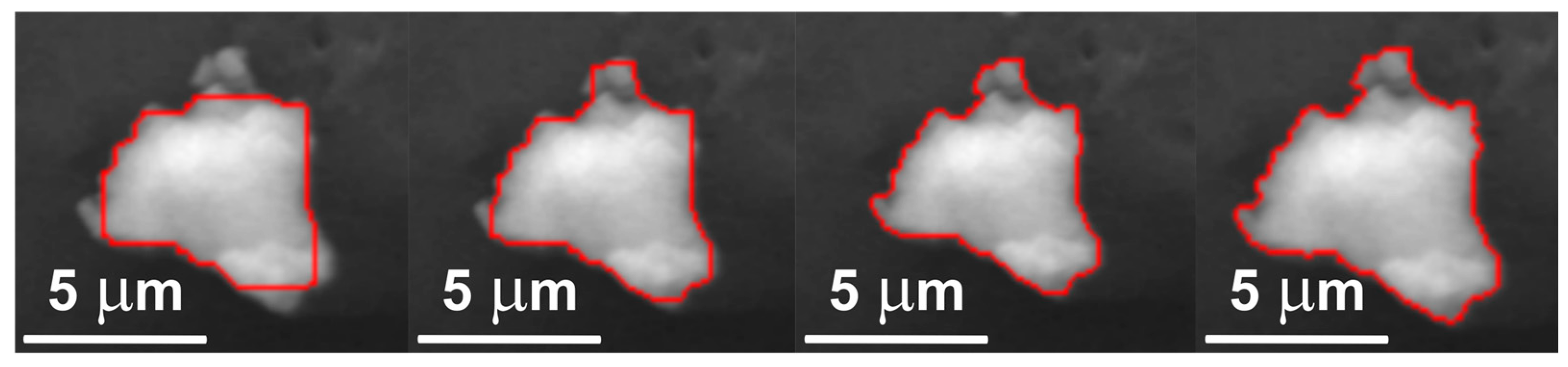

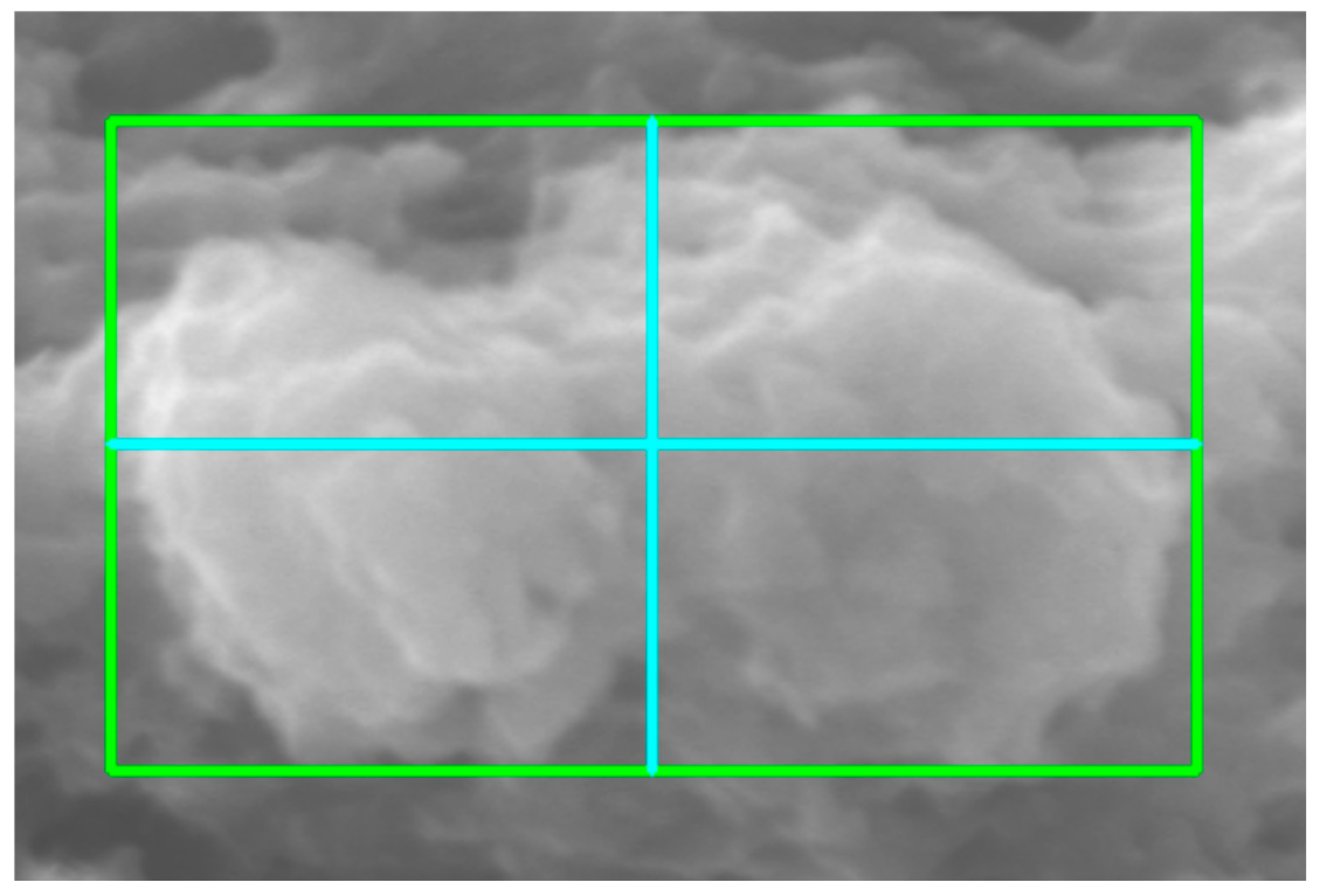

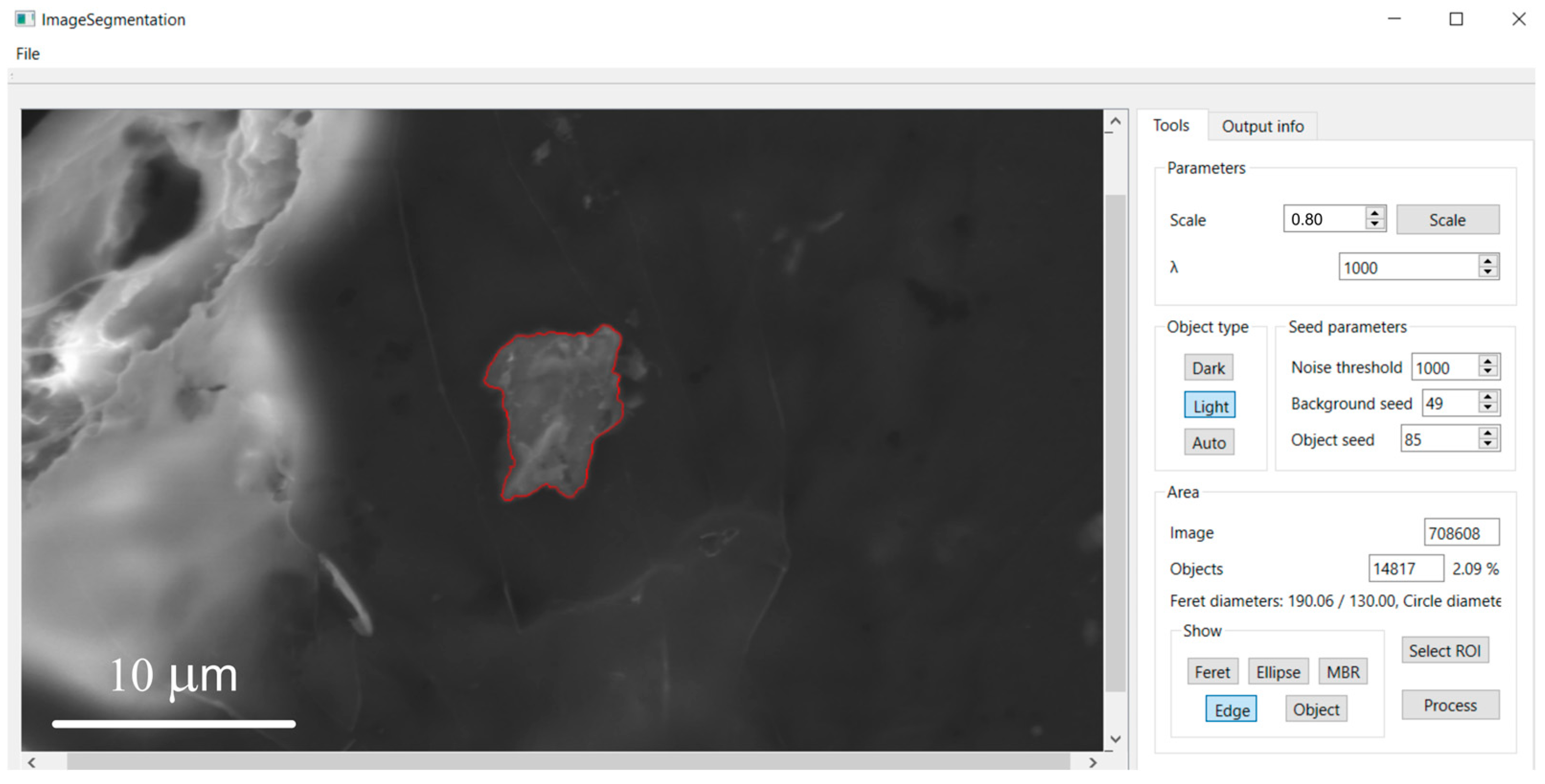

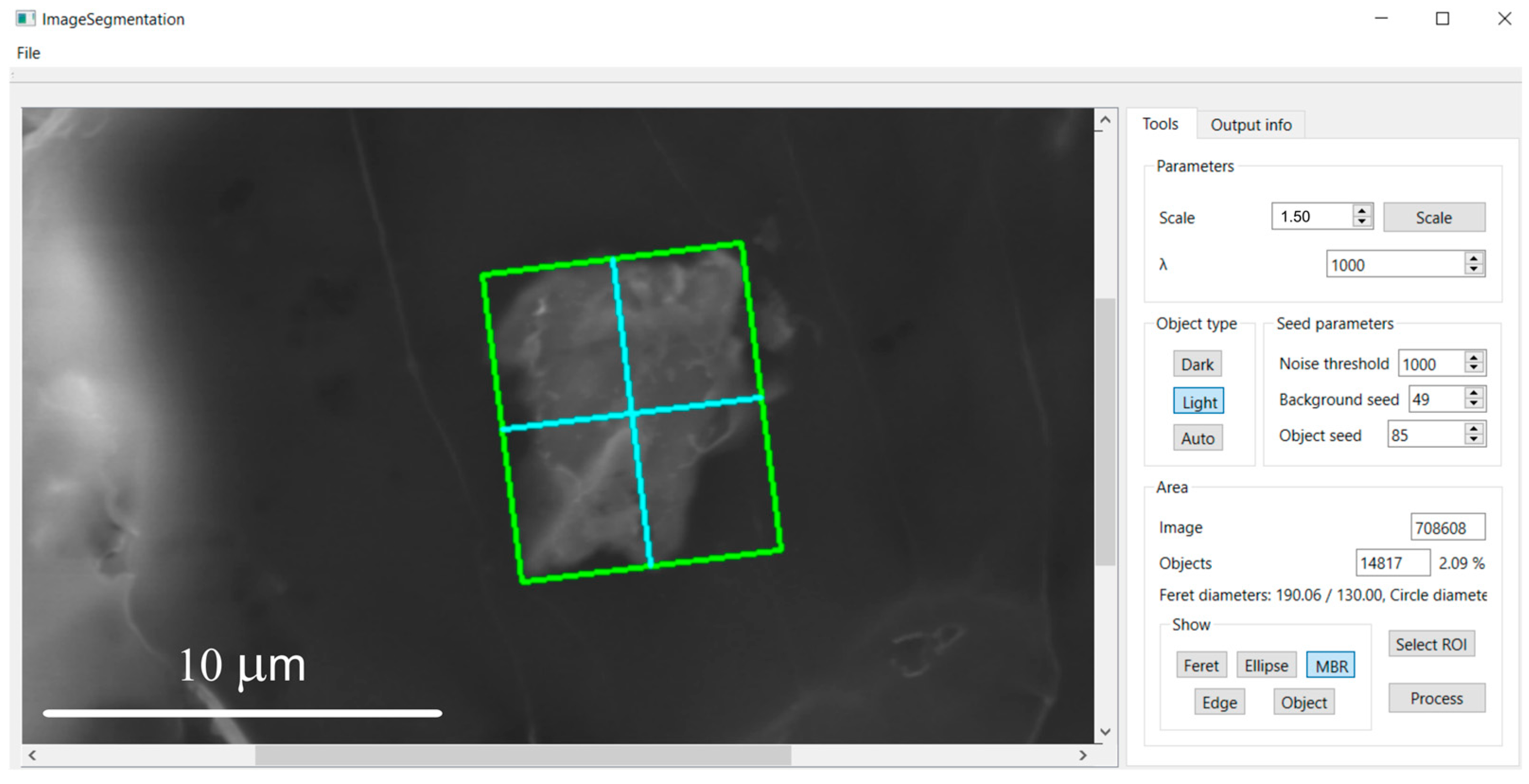

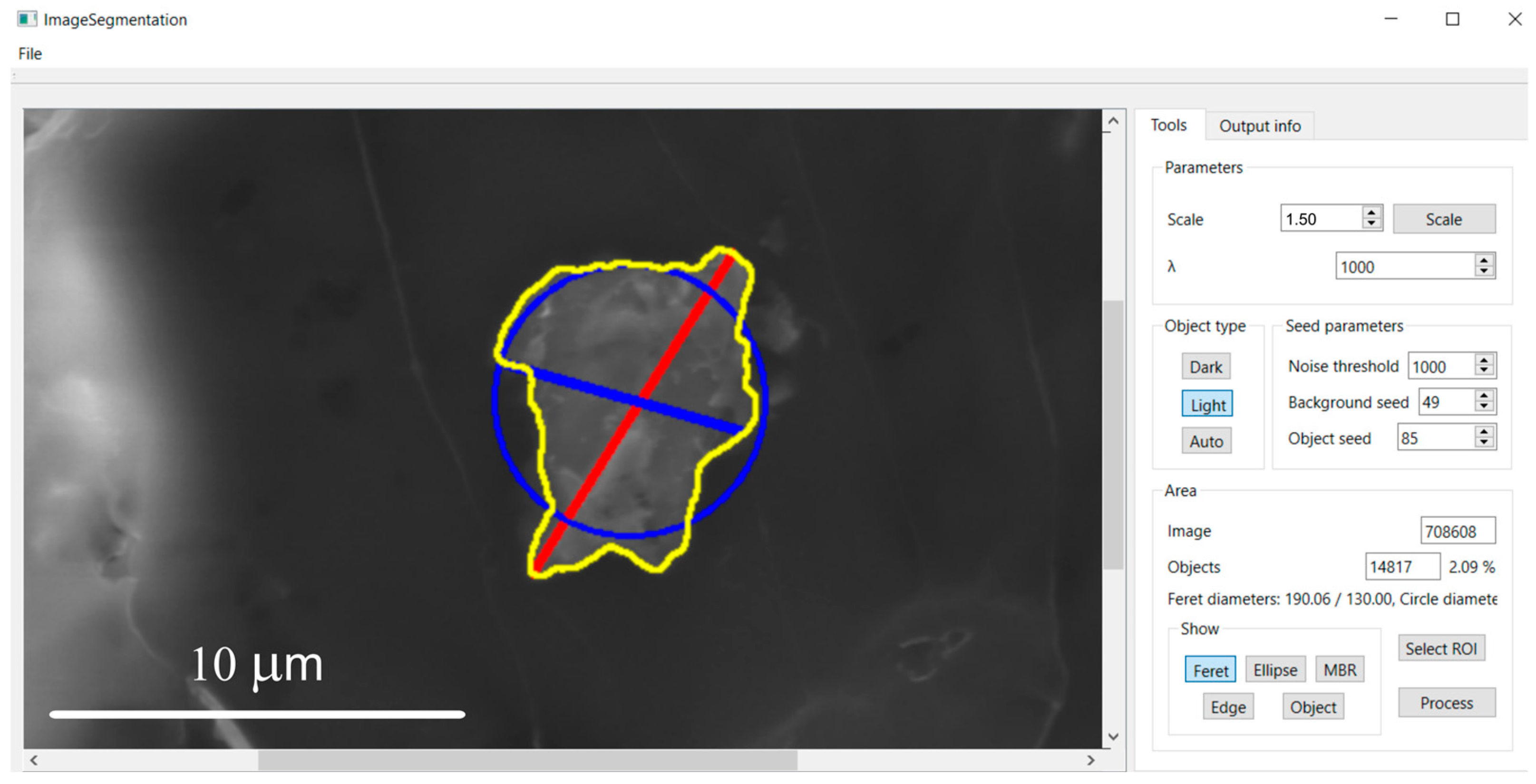

2.3. Implementation, User Interface, and Post-Processing

- Hole Filling: Small holes within the segmented object are filled using an algorithm similar to flood-fill (function fillHolesInGraph). This step is crucial for metallic particles, which may appear hollow in electron microscopy due to surface charging or uneven contrast distributions.

- Noise Removal: Small isolated components that do not meet a size threshold are removed as noise (function removeNoiseFromGraph). Care was taken to set this threshold low enough to preserve small but significant nanoparticles while effectively removing background artifacts. To clean the resulting mask further, morphological operations such as opening and closing may also be applied.

2.4. Quantitative Validation

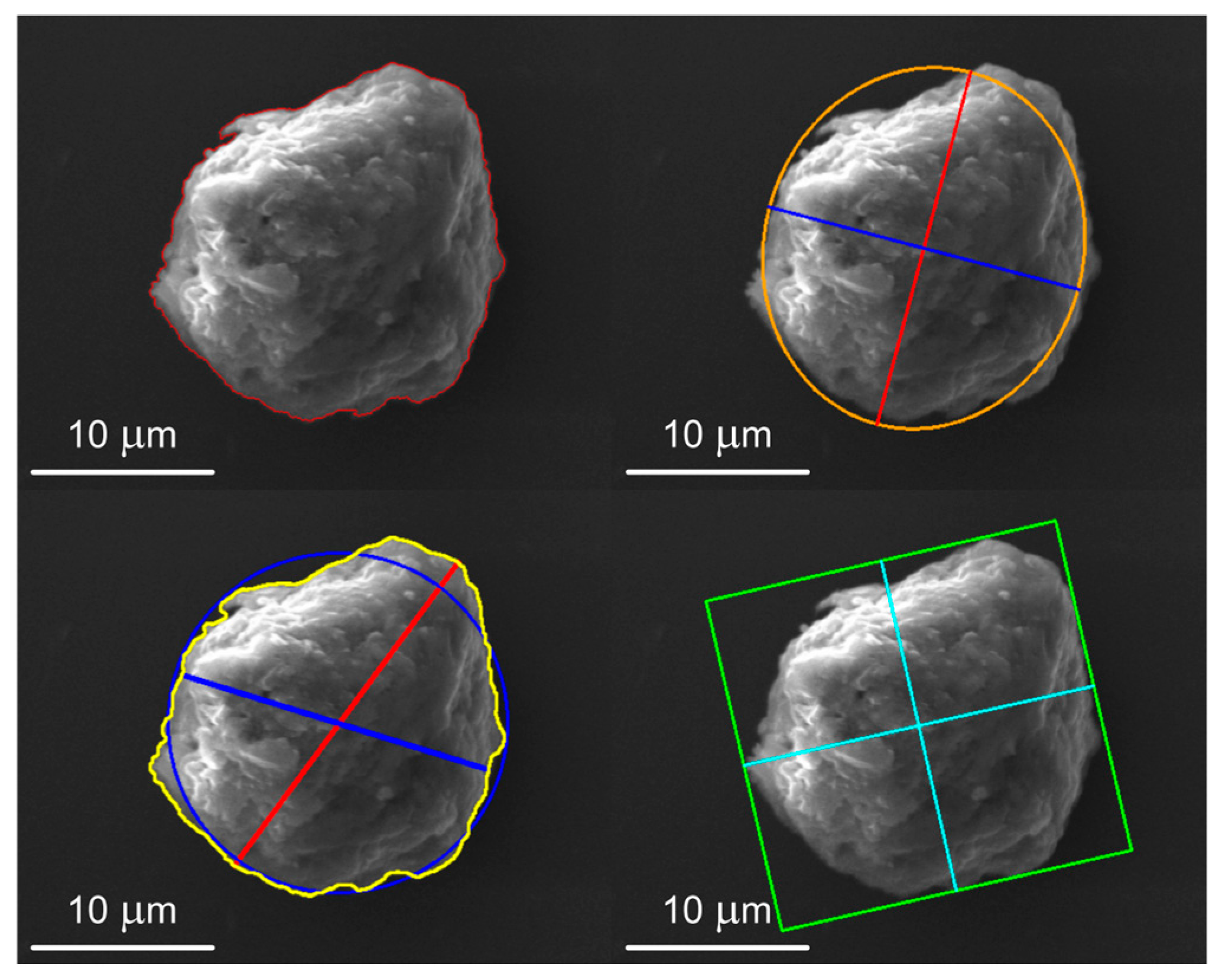

2.5. Morphometric Characterization

2.6. Validation of the Segmentation Algorithm

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Validation of Results

- Intersection over Union (IoU): 0.9609 ± 0.0326

- Dice Coefficient: 0.9798 ± 0.0172

- Pixel Accuracy: 0.9987 ± 0.0018

3.2. Morphometric Characterization of Metallic Particles

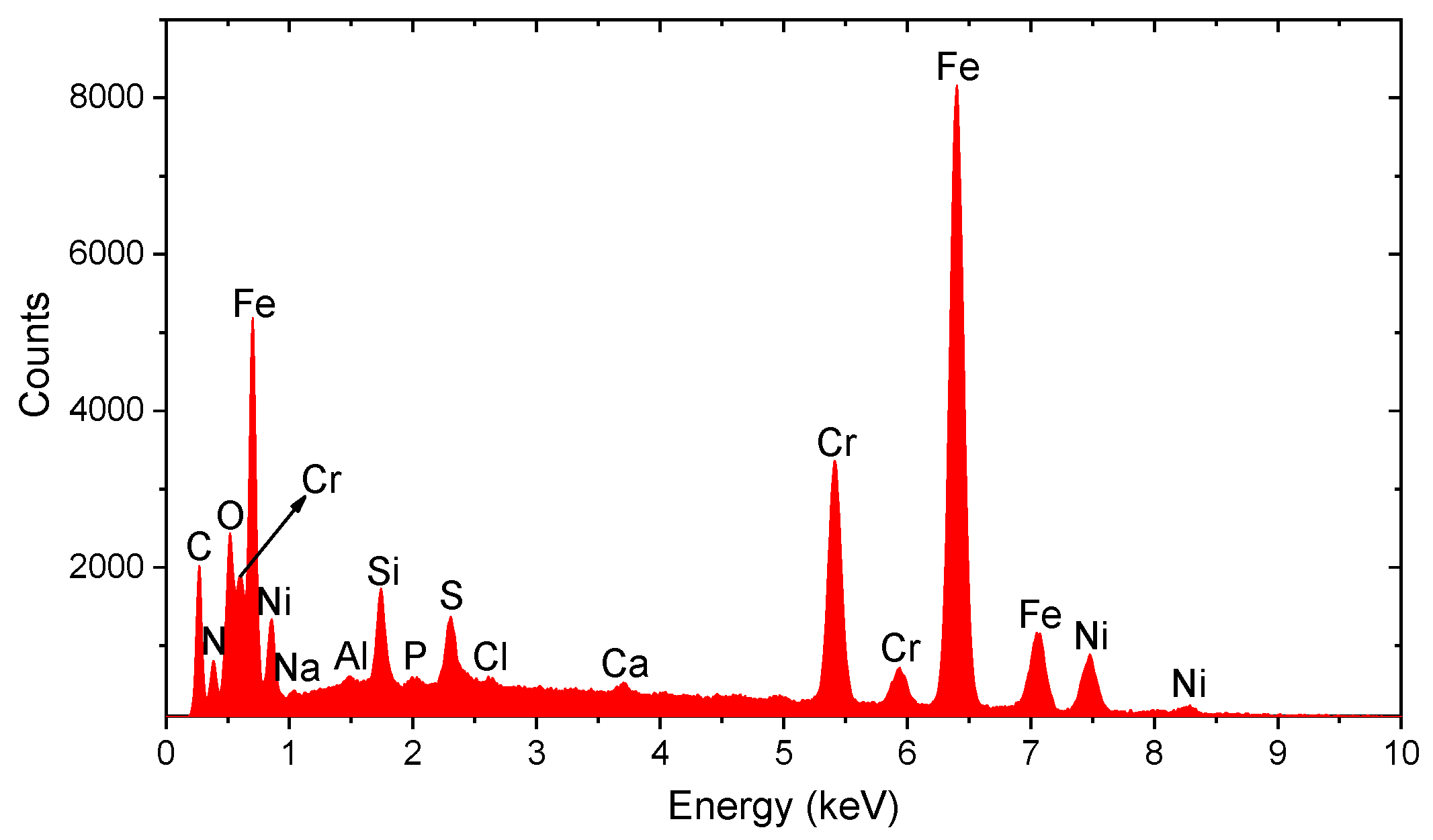

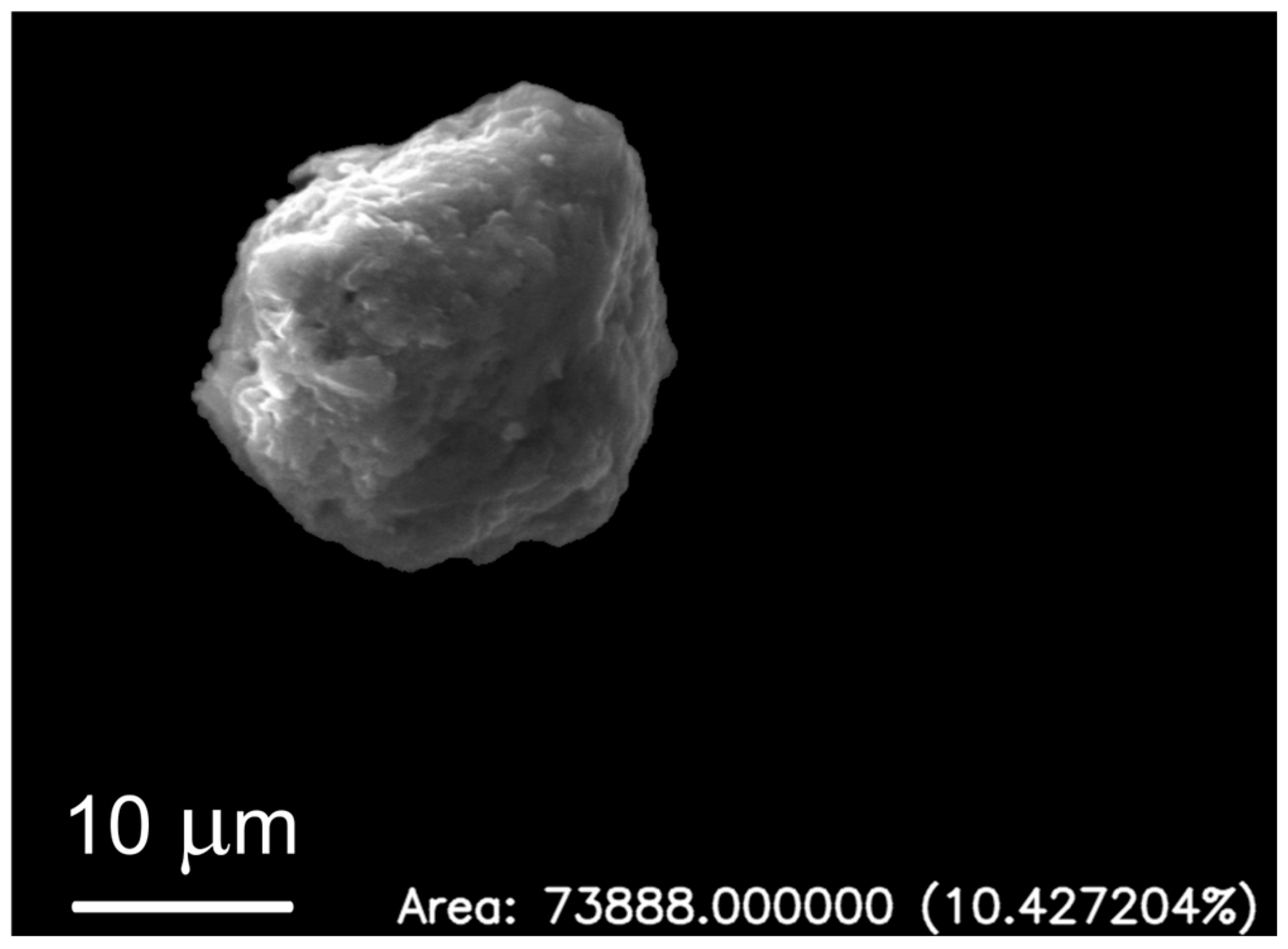

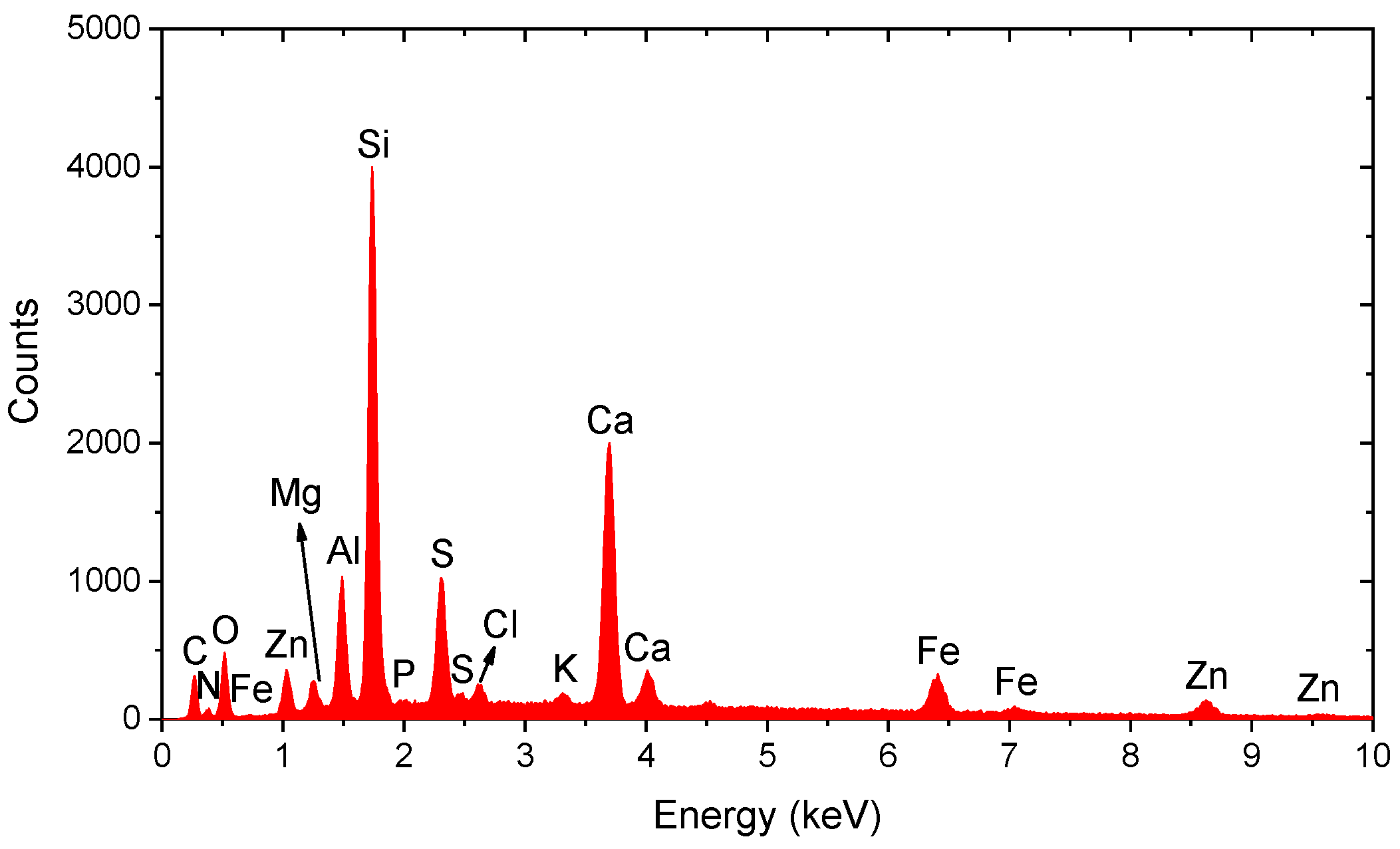

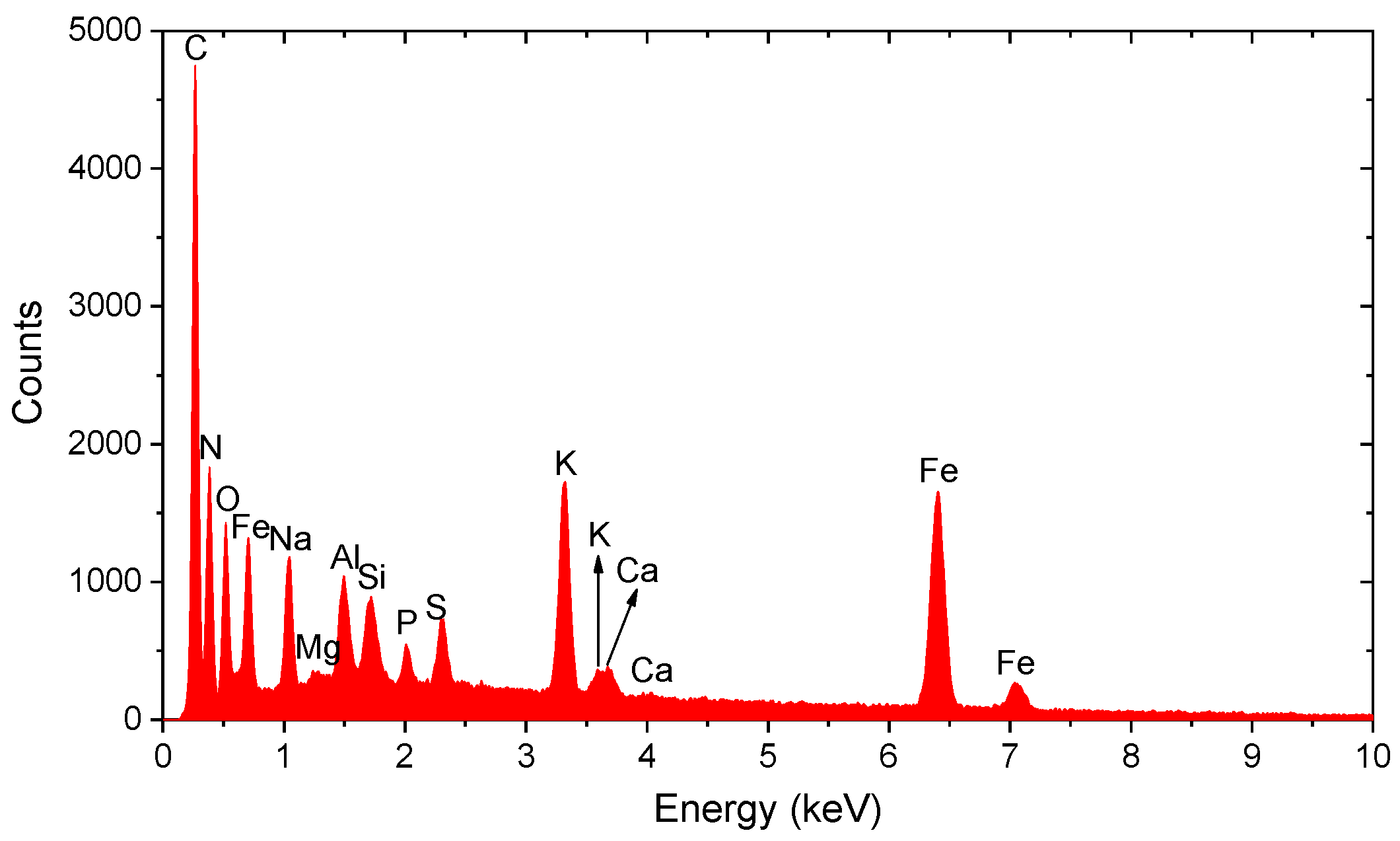

3.3. Spectral Analysis of Metallic Particles

4. Discussion

4.1. Neurobiological Implications of Metallic Particle Presence in the Hippocampus

4.2. Importance of Morphometric Analysis

4.3. Study Limitations and Future Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wiltgen, B.J.; Zhou, M.; Cai, Y.; Balaji, J.; Karlsson, M.G.; Parivash, S.N.; Li, W.; Silva, A.J. The Hippocampus Plays a Selective Role in the Retrieval of Detailed Contextual Memories. Curr. Biol. 2010, 20, 1336–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarov, O.; Hollands, C. Hippocampal neurogenesis: Learning to remember. Prog. Neurobiol. 2016, 138–140, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sofic, E.; Riederer, P.; Heinsen, H.; Beckmann, H.; Reynolds, G.P.; Hebenstreit, G.; Youdim, M.B.H. Increased iron (III) and total iron content in post mortem substantia nigra of parkinsonian brain. J. Neural Transm. 1988, 74, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenner, P.; Olanow, C.W. Oxidative stress and the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Neurology 1996, 47, 161S–170S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casadesus, G.; Smith, M.A.; Zhu, X.; Aliev, G.; Cash, A.D.; Honda, K.; Petersen, R.B.; Perry, G. Alzheimer disease: Evidence for a central pathogenic role of iron-mediated reactive oxygen species. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2004, 6, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasae, K.D.; Abolaji, A.O.; Faloye, T.R.; Odunsi, A.Y.; Oyetayo, B.O.; Enya, J.I.; Rotimi, J.A.; Akinyemi, R.O.; Whitworth, A.J.; Aschner, M. Metallobiology and therapeutic chelation of biometals (copper, zinc and iron) in Alzheimer’s disease: Limitations, and current and future perspectives. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2021, 67, 126779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, J.P.; Young, J.L.; Cai, J.; Cai, L. Current understanding of hexavalent chromium [Cr(VI)] neurotoxicity and new perspectives. Environ. Int. 2022, 158, 106877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyachor, C.P.; Dooka, D.B.; Orish, C.N.; Amadi, C.N.; Bocca, B.; Ruggieri, F.; Senofonte, M.; Frazzoli, C.; Orisakwe, O.E. Mechanistic considerations and biomarkers level in nickel-induced neurodegenerative diseases: An updated systematic review. IBRO Neurosci. Rep. 2022, 13, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, S.; Ripamonti, M.; Moro, A.S.; Cozzi, A. Iron imbalance in neurodegeneration. Mol. Psychiatry 2024, 29, 1139–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asimakidou, E.; Tan, J.K.S.; Zeng, J.; Lo, C.H. Blood–Brain Barrier-Targeting Nanoparticles: Biomaterial Properties and Biomedical Applications in Translational Neuroscience. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Pan, L. A Survey of Graph Cuts/Graph Search Based Medical Image Segmentation. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2018, 11, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.; Chakurkar, P.; Naik, V. Graph Based Image Segmentation by Dinic Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2023 14th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT), New Delhi, India, 6–8 July 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolmogorov, V.; Zabih, R. What energy functions can be minimized via graph cuts? IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2004, 26, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boykov, Y.; Veksler, O.; Zabih, R. Fast approximate energy minimization via graph cuts. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2001, 23, 1222–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, L.R.; Fulkerson, D.R. Maximal Flow Through a Network. In Classic Papers in Combinatorics; Birkhäuser Boston: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 243–248. [Google Scholar]

- Loucký, J.; Oberhuber, T. Graph cuts in segmentation of a left ventricile from MRI data. In Proceedings of the Czech–Japanese Seminar in Applied Mathematics 2010, Prague, Czech Republic, 30 August–1 September 2010; pp. 46–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, L.R.; Fulkerson, D.R. Maximal Flow Through a Network. Can. J. Math. 1956, 8, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinic, E.A. Algorithm for solution of a problem of maximum flow in networks with power estimation. Sov. Math. Dokl. 1970, 11, 1277–1280. [Google Scholar]

- Boykov, Y.; Kolmogorov, V. An experimental comparison of min-cut/max- flow algorithms for energy minimization in vision. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2004, 26, 1124–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althobaiti, N.A. Heavy metals exposure and Alzheimer’s disease: Underlying mechanisms and advancing therapeutic approaches. Behav. Brain Res. 2025, 476, 115212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, J.; Everett, J.; Sadler, P.J.; Telling, N.; Collingwood, J.F. On the origin of metal species in the human brain: A perspective on key physicochemical properties. Metallomics 2025, 17, mfaf004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.V.; Hornburg, K.J.; Merrill, A.; Marvin, E.; Conrad, K.; Welle, K.; Gelein, R.; Chalupa, D.; Graham, U.; Oberdörster, G.; et al. Brain iron accumulation in neurodegenerative disorders: Does air pollution play a role? Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2025, 22, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Shen, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, L.; Ma, X.; Song, N.; Xie, J. Homeostasis and metabolism of iron and other metal ions in neurodegenerative diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshiro, S.; Morioka, M.S.; Kikuchi, M. Dysregulation of iron metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Adv. Pharmacol. Sci. 2011, 2011, 378278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zambelli, B.; Ciurli, S. Nickel and Human Health. In Interrelations Between Essential Metal Ions and Human Diseases; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 321–357. [Google Scholar]

- Duckett, S. Abnormal deposits of chromium in the pathological human brain. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1986, 49, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickerson, A.S.; Hansen, J.; Gredal, O.; Weisskopf, M.G. Study of Occupational Chromium, Iron, and Nickel Exposure and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis in Denmark. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, S.; Wang, Z.; Cao, X.; Wang, L.; Gao, X.; Shen, Y.; Du, J.; Liu, P.; Zhuang, Y.; Guo, X. Insights into the effects of chronic combined chromium-nickel exposure on colon damage in mice through transcriptomic analysis and in vitro gastrointestinal digestion assay. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 279, 116458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turhan, Ş.; Altuner, E.M.; Bakır, T.K.; Duran, C.; Hançerlioğulları, A.; Kurnaz, A. Assessment of Human Health Risk Caused by Heavy Metals in Kiln Dust from Coal-Fired Clay Brick Factories in Türkiye. Expo. Health 2025, 17, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norisepehr, M.; Darvishmotevalli, M.; Qorbani, M.; Rahimi, J.; Moradnia, M.; Salari, M.; Gomnam, F. Monitoring of urinary nickel and chromium in metal industries workers in Alborz, Iran. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindal, A.B. The effect of particle shape on cellular interaction and drug delivery applications of micro- and nanoparticles. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 532, 450–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadji, H.; Bouchemal, K. Effect of micro- and nanoparticle shape on biological processes. J. Control. Release 2022, 342, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Edge | Cost | |

|---|---|---|---|

| t-link | (s, p) | for p ∈ P/{O ∪ B} | λRs(p) |

| for p ∈ O | Kmax | ||

| for p ∈ B | 0 | ||

| (p, t) | for p ∈ P/{O ∪ B} | λRt(p) | |

| for p ∈ O | 0 | ||

| for p ∈ B | Kmax | ||

| n-link | (p, q) | for p, q ∈ P | N(p, q) |

| Particle Type | Area (nm2) | Circularity | Aspect Ratio | Primary Elements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe-Zn | 715,000 | 0.726 | 0.78 | Fe, Zn |

| Fe-rich | 450,000 | 0.85 | 0.92 | Fe |

| Fe-Cr-Ni | 620,000 | 0.65 | 0.6 | Fe, Cr, Ni |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pánik, J.; Ždímalová, M.; Kosnáč, D.; Kopáni, M.; Dulanská, S.; Kretsul, N.; Trnka, M. Segmentation and Multimodal Characterization of Metal Particles in the Human Hippocampus Using Discrete Segmentation Algorithms and Correlation Spectral Analysis. Molecules 2026, 31, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010009

Pánik J, Ždímalová M, Kosnáč D, Kopáni M, Dulanská S, Kretsul N, Trnka M. Segmentation and Multimodal Characterization of Metal Particles in the Human Hippocampus Using Discrete Segmentation Algorithms and Correlation Spectral Analysis. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010009

Chicago/Turabian StylePánik, Ján, Mária Ždímalová, Daniel Kosnáč, Martin Kopáni, Silvia Dulanská, Nazarii Kretsul, and Michal Trnka. 2026. "Segmentation and Multimodal Characterization of Metal Particles in the Human Hippocampus Using Discrete Segmentation Algorithms and Correlation Spectral Analysis" Molecules 31, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010009

APA StylePánik, J., Ždímalová, M., Kosnáč, D., Kopáni, M., Dulanská, S., Kretsul, N., & Trnka, M. (2026). Segmentation and Multimodal Characterization of Metal Particles in the Human Hippocampus Using Discrete Segmentation Algorithms and Correlation Spectral Analysis. Molecules, 31(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010009