Trimetallic Nanocomposites Grafted on Modified PET Substrate Revealing Antibacterial Effect Against Escherichia coli

Abstract

1. Introduction

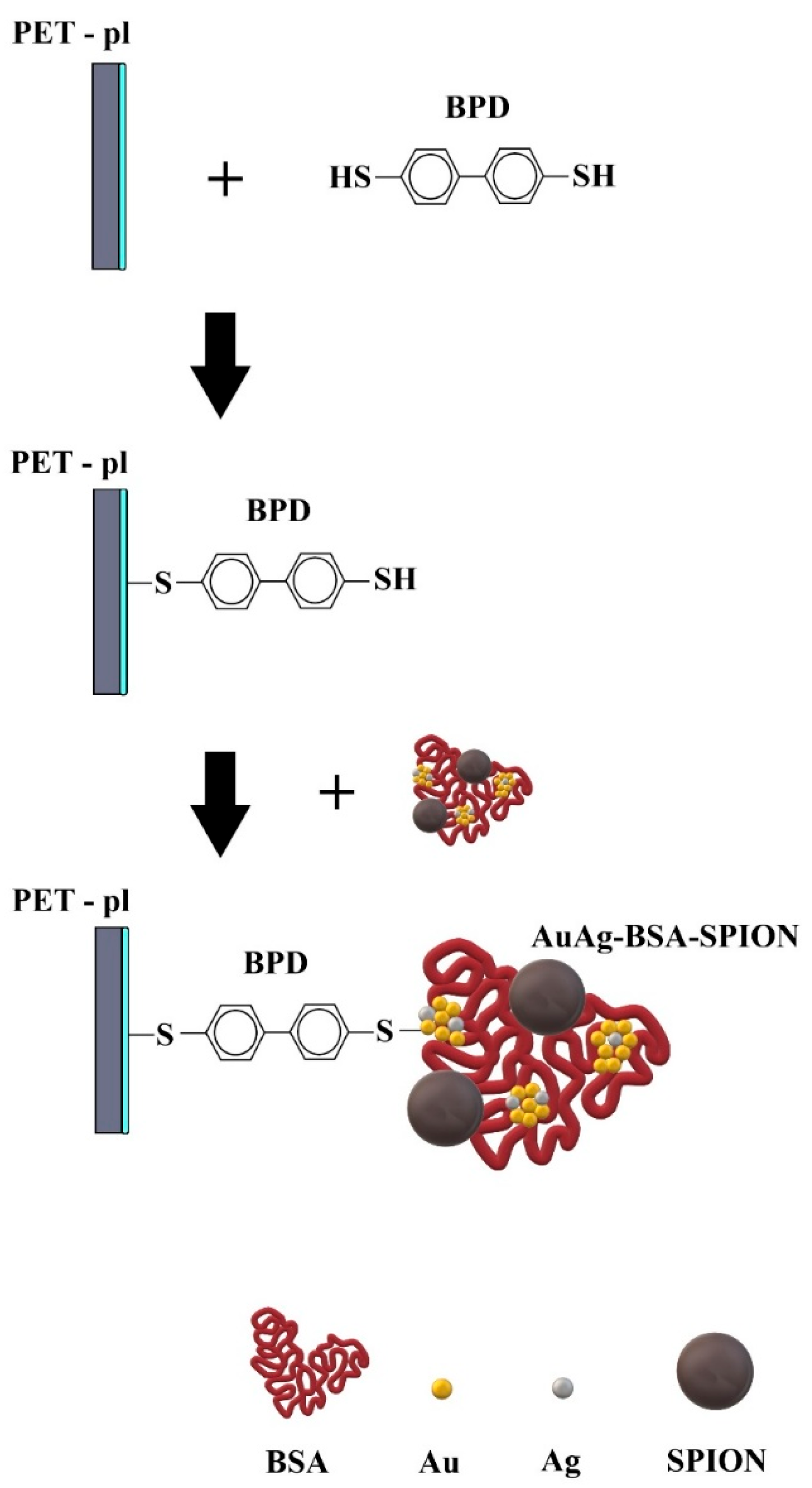

2. Results and Discussion

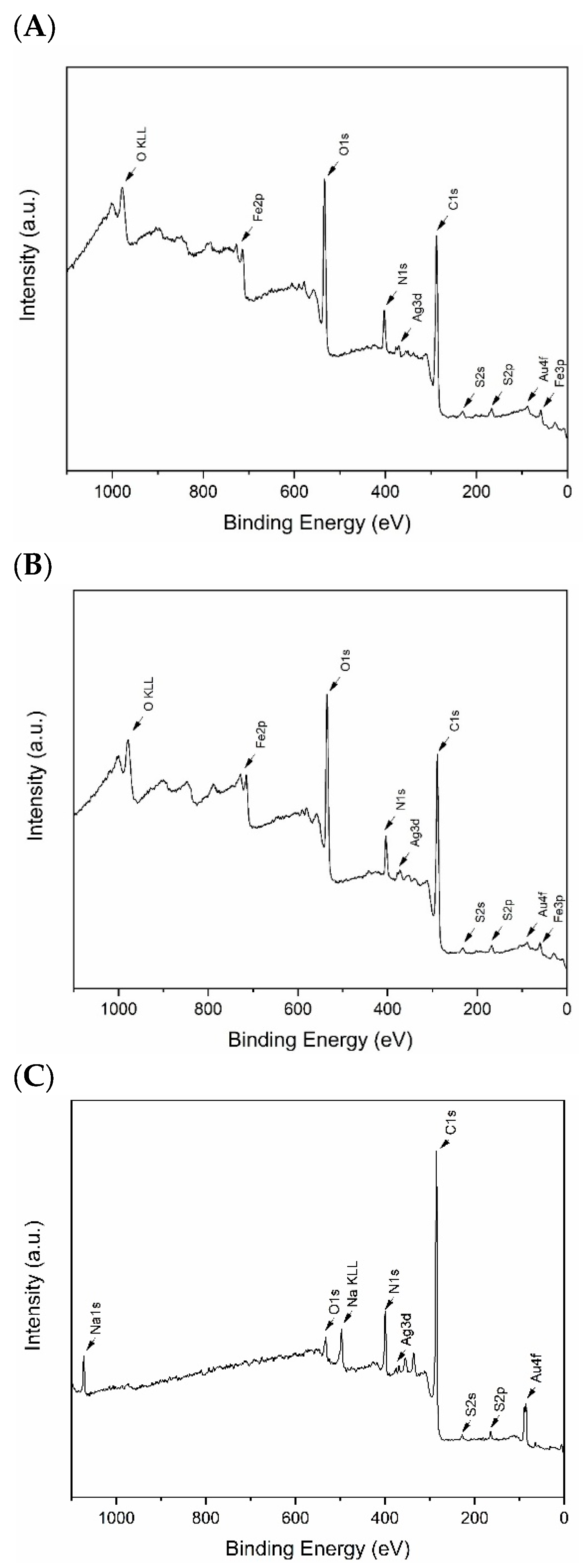

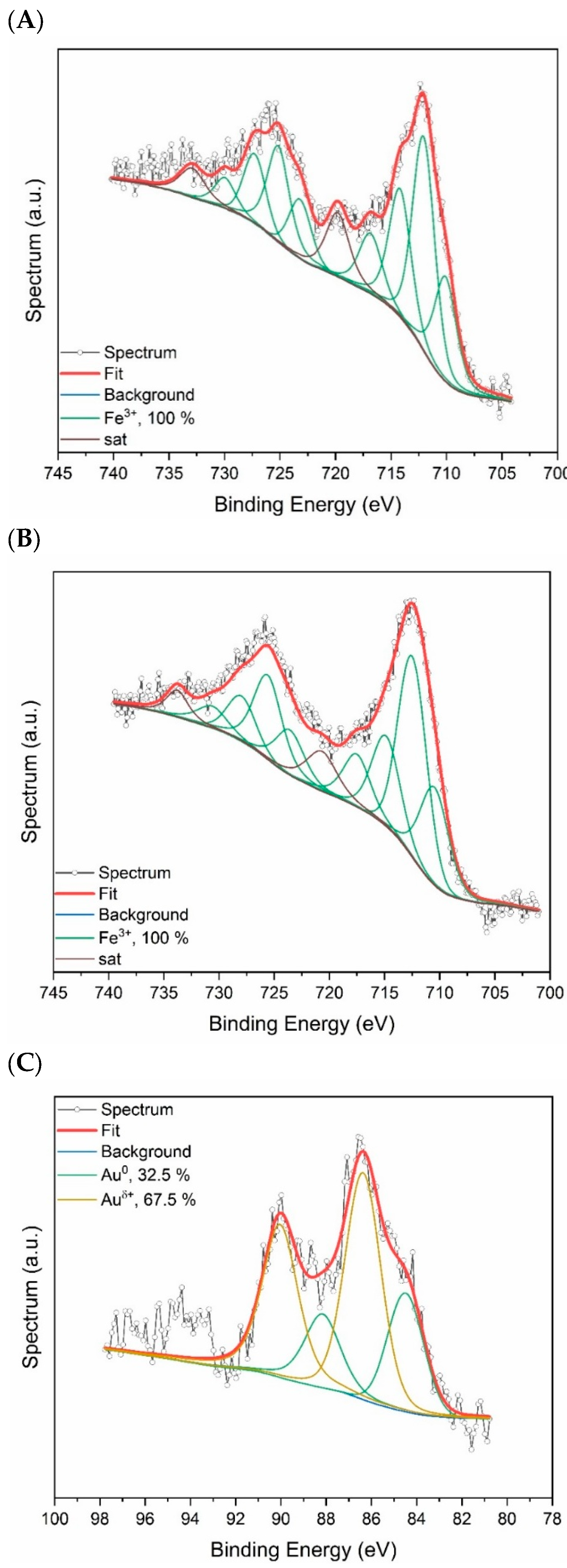

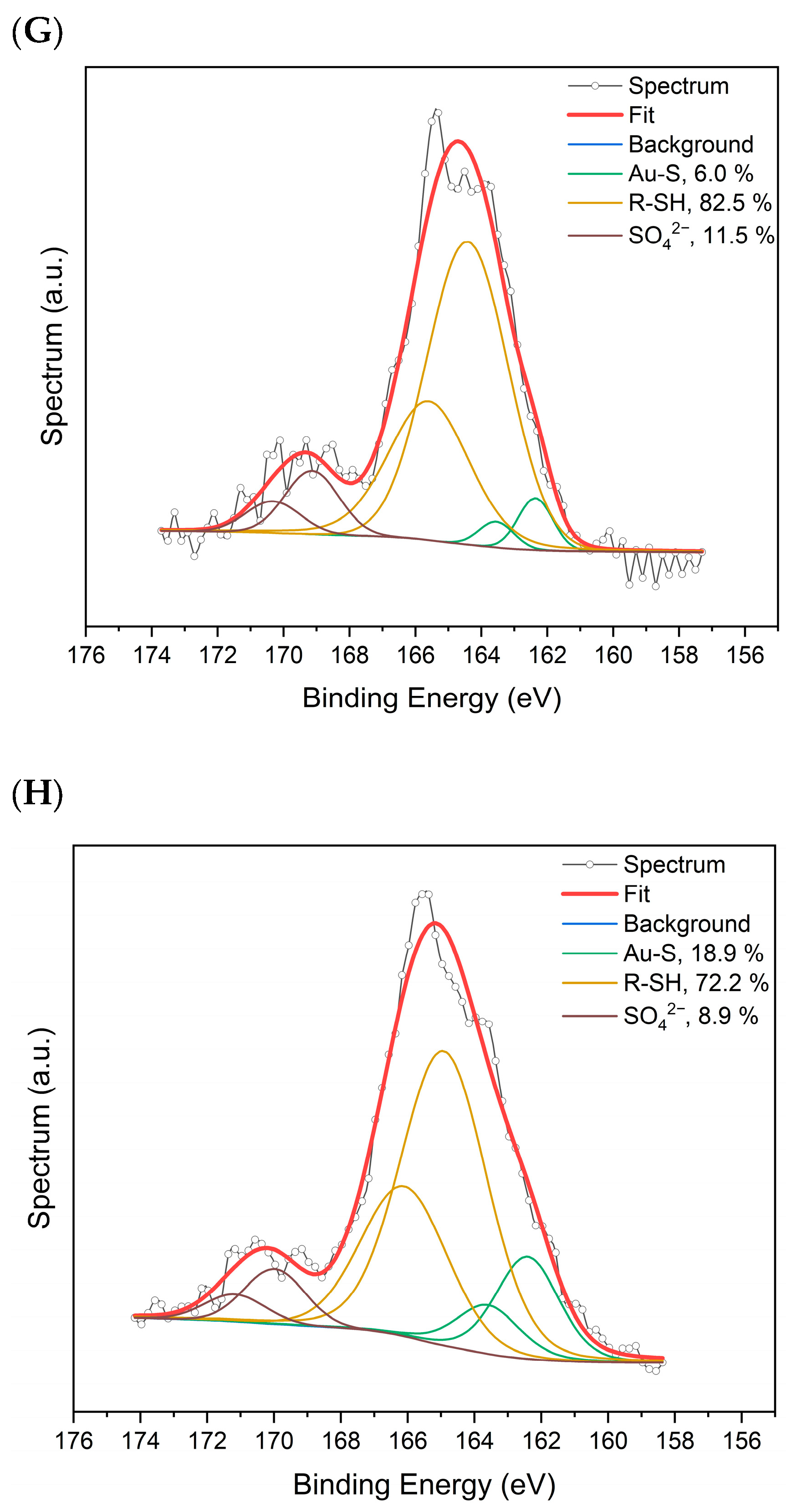

2.1. Spectroscopic Characterization of AuAg-BSA-SPION@pl-BPD-PET

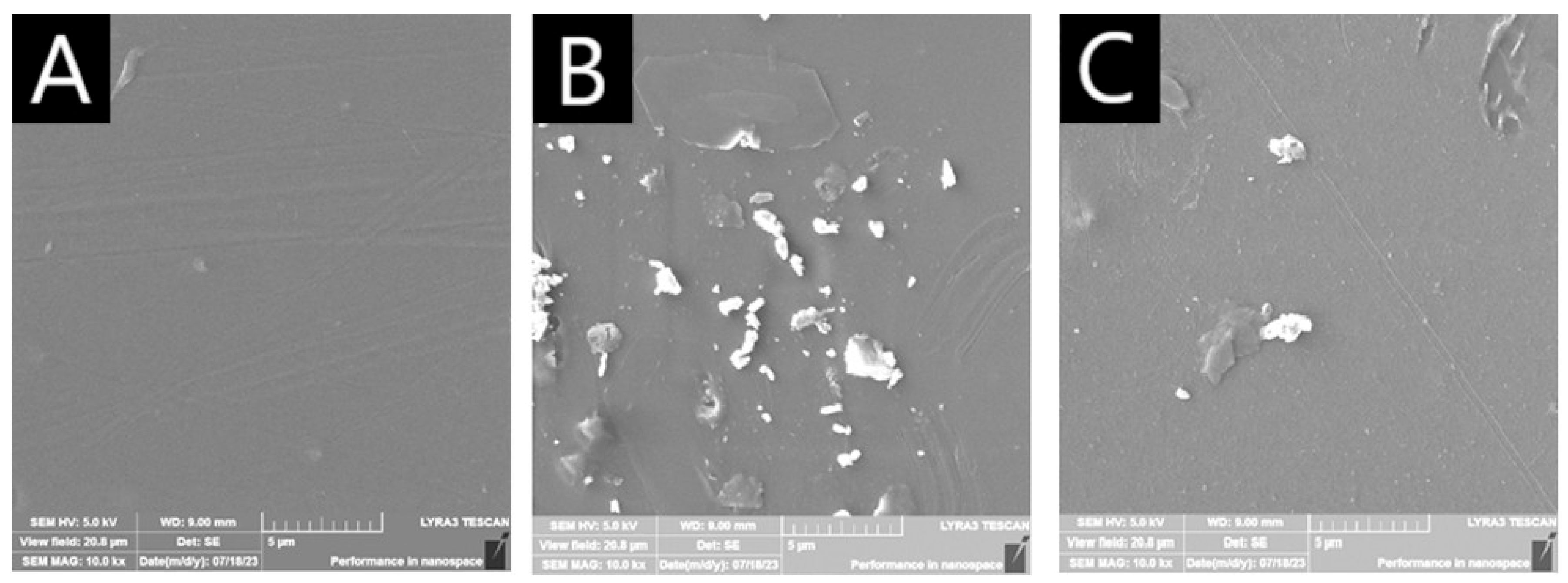

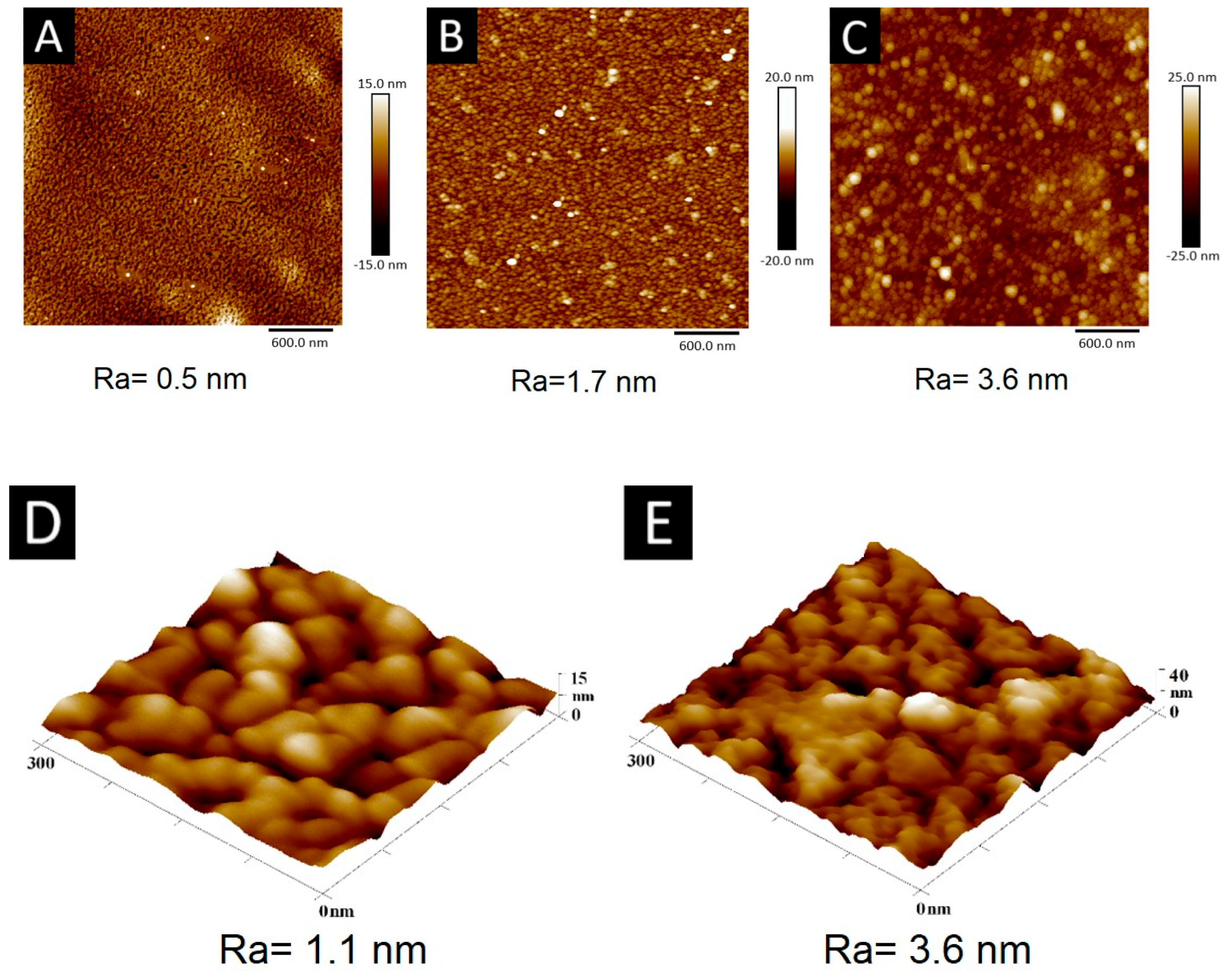

2.2. Microscopic Characterization of AuAg-BSA-SPION@pl-BPD-PET

2.3. Goniometric Contact Angle Measurements

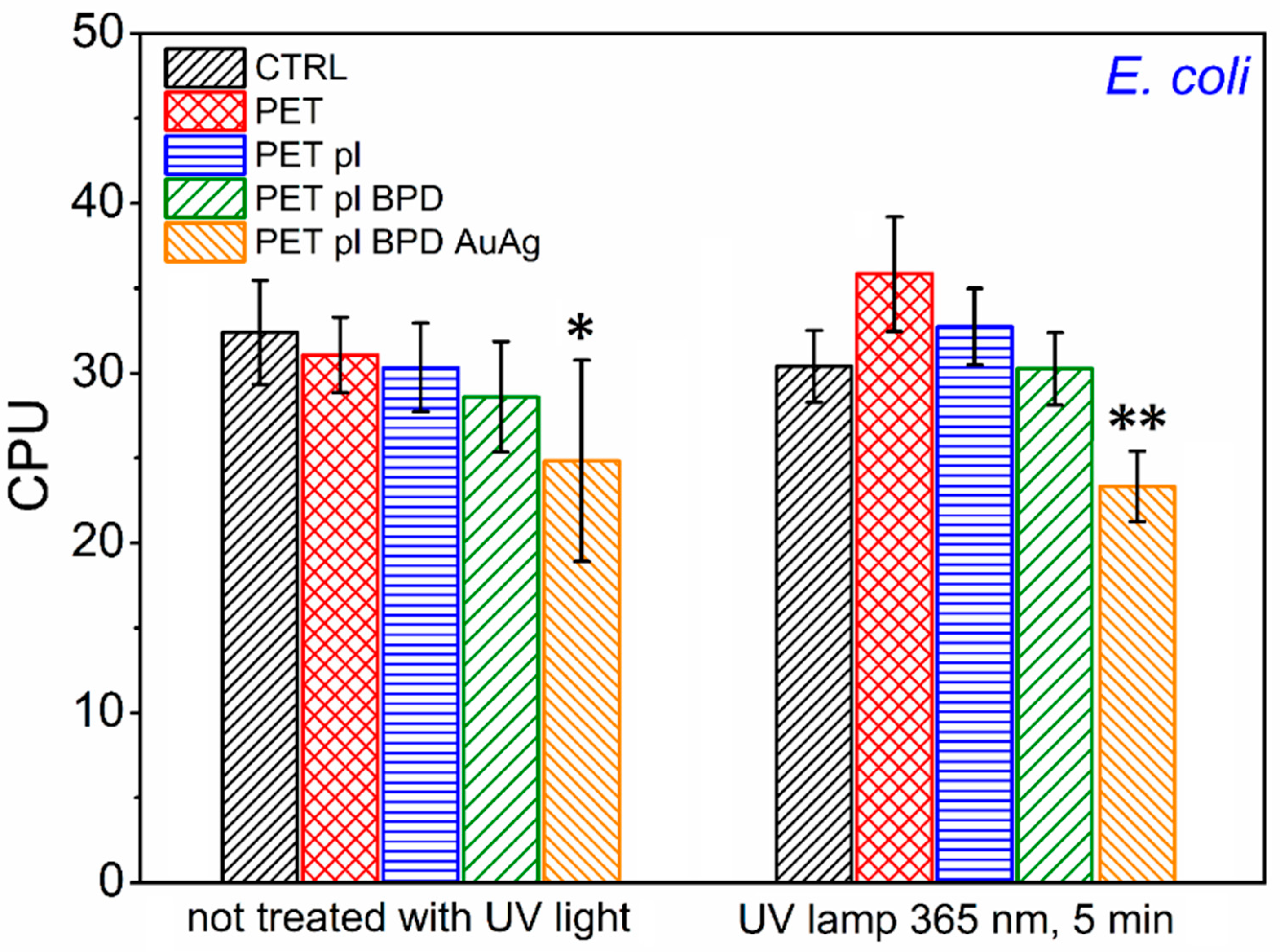

2.4. Antibacterial Effect Against Escherichia coli

3. Experimental Part

3.1. Materials for Trimetallic Nanocomposites Synthesis

3.2. AuAg-BSA-SPION@pl-BPD-PET Preparation

3.3. Analytical Methods

3.4. Antibacterial Effect

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Er-Rahmani, S.; Errabiti, B.; Raouan, S.E.; Elharchli, E.; Elaabedy, A.; El Abed, S.; El Ghachtouli, N.; Sadiki, M.; Zanane, C.; Latrache, H.; et al. Reduction of Biofilm Formation on 3D Printing Materials Treated with Essential Oils Major Compounds. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 182, 114864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcionivoschi, N.; Balta, I.; Butucel, E.; McCleery, D.; Pet, I.; Iamandei, M.; Stef, L.; Morariu, S. Natural Antimicrobial Mixtures Disrupt Attachment and Survival of E. Coli and C. Jejuni to Non-Organic and Organic Surfaces. Foods 2023, 12, 3863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirain, C.O.; Silva, R.C.; Antonelli, P.J. Prevention of Biofilm Formation by Polyquaternary Polymer. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2016, 88, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Xu, C.; Zhou, X.; Qi, R.; Liu, L.; Lv, F.; Li, Z.; Wang, S. Cationic Conjugated Polymers for Enhancing Beneficial Bacteria Adhesion and Biofilm Formation in Gut Microbiota. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2020, 188, 110815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Algadi, H.; Alhoot, M.A.; Al-Maleki, A.R.; Purwitasari, N. Effects of Metal and Metal Oxide Nanoparticles against Biofilm-Forming Bacteria: A Systematic Review. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 34, 1748–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Huang, W.; Zhang, J.; Yu, Y.; Sun, T. Metal-Based Nanoparticles as Antimicrobial Agents: A Review. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 2529–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Salleh, N.K.; Aziz, F.; Mohtar, S.S.; Mohammad, A.M.; Mhamad, S.A.; Yusof, N.; Jaafar, J.; Wan Salleh, W.N. Strategies to Improve the Antimicrobial Properties of Metal-Oxide Based Photocatalytic Coating: A Review. Prog. Org. Coat. 2024, 187, 108183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanwar, S.N.; Parauha, Y.R.; There, Y.; Swart, H.C.; Dhoble, S.J. Plant-Based Biosynthesis of Metal and Metal Oxide Nanoparticles: An Update on Antimicrobial and Anticancer Activity. ChemBioEng Rev. 2024, 11, e202400012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R.J. The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly of Metals as Antimicrobials. BioMetals 2024, 37, 545–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frei, A.; Verderosa, A.D.; Elliott, A.G.; Zuegg, J.; Blaskovich, M.A.T. Metals to Combat Antimicrobial Resistance. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2023, 7, 202–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, S.; Das, D.K.; Kaur, J.; Kumar, A.; Ubaidullah, M.; Hasan, M.; Yadav, K.K.; Gupta, R.K. Transition Metal-Based Nanoparticles as Potential Antimicrobial Agents: Recent Advancements, Mechanistic, Challenges, and Future Prospects. Discov. Nano 2023, 18, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leong, C.Y.; Wahab, R.A.; Lee, S.L.; Ponnusamy, V.K.; Chen, Y.H. Current Perspectives of Metal-Based Nanomaterials as Photocatalytic Antimicrobial Agents and Their Therapeutic Modes of Action: A Review. Environ. Res. 2023, 227, 115578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezić, I.; Meštrović, E. Characterization of Nanoparticles in Antimicrobial Coatings for Medical Applications—A Review. Coatings 2023, 13, 1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ślosarczyk, A.; Klapiszewska, I.; Skowrońska, D.; Janczarek, M.; Jesionowski, T.; Klapiszewski, Ł. A Comprehensive Review of Building Materials Modified with Metal and Metal Oxide Nanoparticles against Microbial Multiplication and Growth. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 466, 143276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, S.; Bharti, S. The Synergy of Nanoparticles and Metal-Organic Frameworks in Antimicrobial Applications: A Critical Review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 111458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhou, H.; Jiang, P.; Xiao, X. Metal-Based Nanomaterials as Antimicrobial Agents: A Novel Driveway to Accelerate the Aggravation of Antibiotic Resistance. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 455, 131658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyenova, H.Y.; Vokata, B.; Zaruba, K.; Siegel, J.; Kolska, Z.; Svorcik, V.; Slepicka, P.; Reznickova, A. Silver Nanoparticles Grafted onto PET: Effect of Preparation Method on Antibacterial Activity. React. Funct. Polym. 2019, 145, 104376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Villani, S.; Mansi, A.; Marcelloni, A.M.; Chiominto, A.; Amori, I.; Proietto, A.R.; Calcagnile, M.; Alifano, P.; Bagheri, S.; et al. Antimicrobial and Superhydrophobic CuONPs/TiO2 Hybrid Coating on Polypropylene Substrates against Biofilm Formation. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 45376–45385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, T.; Zeng, X.; Zou, Y.; Luo, T.; Tao, X.; Xu, H. Fabrication of Polyvinyl Alcohol/Vanillin/Ti3C2Tx/ZnONPs Composite Film with Excellent Antimicrobial Properties for Pepper Preservation. Food Biosci. 2024, 59, 104175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, Z.; Saran, A.; Hou, S.; Wen, T.; Liu, W.; Ji, Y.; Jiang, X.; Wu, X. Gold Nanorods Core/AgPt Alloy Nanodots Shell: A Novel Potent Antibacterial Nanostructure. Nano Res. 2013, 6, 822–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, N.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Dey, K.K.; Yadav, V.B.; Nath, G.; Srivastava, A.K.; Yadav, R.R. Trimetallic Au/Pt/Ag Based Nanofluid for Enhanced Antibacterial Response. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2018, 218, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlugaszewska, J.; Dobrucka, R. Effectiveness of Biosynthesized Trimetallic Au/Pt/Ag Nanoparticles on Planktonic and Biofilm Enterococcus Faecalis and Enterococcus Faecium Forms. J. Clust. Sci. 2019, 30, 1091–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivasubramanian, K.; Tamilselvi, Y.; Velmurugan, P.; Oleyan Al-Otibi, F.; Ibrahim Alharbi, R.; Mohanavel, V.; Manickam, S.; Rebecca, L.J.; Rudragouda Patil, B. Enhanced Applications in Dentistry through Autoclave-Assisted Sonochemical Synthesis of Pb/Ag/Cu Trimetallic Nanocomposites. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2024, 108, 106966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, D.; Mangla, S.; Neogi, S. Antibacterial Study of CuO-NiO-ZnO Trimetallic Oxide Nanoparticle. Mater. Lett. 2020, 271, 127740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaseghi, Z.; Tavakoli, O.; Nematollahzadeh, A. Rapid Biosynthesis of Novel Cu/Cr/Ni Trimetallic Oxide Nanoparticles with Antimicrobial Activity. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 1898–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacmanová, V.; Ostruszka, R.; Petr, M.; Slepička, P.; Průša, F.; Kvítek, O.; Kutová, A.; Řezníčková, A.; Šišková, K. Photo-Activated Antibacterial Effect of Bimetallic Nanocomposite Grafted on Modified PET Substrate. Next Res. 2025, 2, 100996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Park, S.; Ryu, S.; Park, S.; Kim, M.S. Different Inactivation Mechanisms of Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli in Water by Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species Generated from an Argon Plasma Jet. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 3276–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.K.; Siskova, K.M.; Zboril, R.; Gardea-Torresdey, J.L. Organic-Coated Silver Nanoparticles in Biological and Environmental Conditions: Fate, Stability and Toxicity. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2014, 204, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Řezníčková, A.; Kolská, Z.; Hnatowicz, V.; Stopka, P.; Švorčík, V. Comparison of Glow Argon Plasma-Induced Surface Changes of Thermoplastic Polymers. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 2011, 269, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Švorčík, V.; Kolská, Z.; Kvítek, O.; Siegel, J.; Řezníčková, A.; Řezanka, P.; Záruba, K. “Soft and Rigid” Dithiols and Au Nanoparticles Grafting on Plasma-Treated Polyethyleneterephthalate. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2011, 6, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reznickova, A.; Novotna, Z.; Kolska, Z.; Svorcik, V. Immobilization of Silver Nanoparticles on Polyethylene Terephthalate. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reznickova, A.; Kolska, Z.; Siegel, J.; Svorcik, V. Grafting of Gold Nanoparticles and Nanorods on Plasma-Treated Polymers by Thiols. J. Mater. Sci. 2012, 47, 6297–6304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svačinová, V.; Halili, A.; Ostruszka, R.; Pluháček, T.; Jiráková, K.; Jirák, D.; Šišková, K. Trimetallic Nanocomposites Developed for Efficient in Vivo Bimodal Imaging via Fluorescence and Magnetic Resonance. J. Mater. Chem. B 2024, 12, 8153–8166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoppellaro, G.; Ostruszka, R.; Siskova, K. Engineered Protein-Iron and/or Gold-Protein-Iron Nanocomposites in Aqueous Solutions upon UVA Light: Photo-Induced Electron Transfer Possibilities and Limitations. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2024, 450, 115415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šuljagić, M.; Milenković, M.; Uskoković, V.; Mirković, M.; Vrbica, B.; Pavlović, V.; Živković-Radovanović, V.; Stanković, D.; Andjelković, L. Silver Distribution and Binding Mode as Key Determinants of the Antimicrobial Performance of Iron Oxide/Silver Nanocomposites. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 32, 104157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Minella, M.; del Castillo González, I.; Lehmann, A.H.; Li, D.; Gonçalves, N.P.F.; Prevot, A.B.; Lin, T.; Giannakis, S. From Rust to Robust Disinfectants: How Do Iron Oxides and Inorganic Oxidants Synergize with UVA Light towards Bacterial Inactivation? Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 931, 172740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostruszka, R.; Zoppellaro, G.; Tomanec, O.; Pinkas, D.; Filimonenko, V.; Šišková, K. Evidence of Au(II) and Au(0) States in Bovine Serum Albumin-Au Nanoclusters Revealed by CW-EPR/LEPR and Peculiarities in HR-TEM/STEM Imaging. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibria, M.G.; Zhang, F.; Lee, T.H.; Kim, M.J.; Howlader, M.M.R. Comprehensive Investigation of Sequential Plasma Activated Si/Si Bonded Interfaces for Nano-Integration on the Wafer Scale. Nanotechnology 2010, 21, 134011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svačinová, V.; Pluháček, T.; Petr, M.; Siskova, K. Maturing Conditions of Bimetallic Nanocomposites as a New Factor Influencing Au-Ag Synergism and Impact of Cu(II) and/or Fe(III) on Luminescence. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2025, 12, 241385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, Y.; Liu, S.; Pihl, M.; van der Mei, H.C.; Liu, J.; Hizal, F.; Choi, C.H.; Chen, H.; Ren, Y.; Busscher, H.J. Bacterial Interactions with Nanostructured Surfaces. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 38, 170–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Pandit, S.; Garnæs, J.; Tunjic, S.; Mokkapati, V.R.S.S.; Sultan, A.; Thygesen, A.; Mackevica, A.; Mateiu, R.V.; Daugaard, A.E.; et al. Green Synthesis of Gold and Silver Nanoparticles from Cannabis Sativa (Industrial Hemp) and Their Capacity for Biofilm Inhibition. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 3571–3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqi, K.S.; Husen, A.; Rao, R.A.K. A Review on Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles and Their Biocidal Properties. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2018, 16, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qayyum, S.; Oves, M.; Khan, A.U. Obliteration of Bacterial Growth and Biofilm through ROS Generation by Facilely Synthesized Green Silver Nanoparticles. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, 0181363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, W.; Lü, X.; Jiang, X. The Molecular Mechanism of Action of Bactericidal Gold Nanoparticles on Escherichia coli. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 2327–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.L.; Moreirinha, C.; Lopes, D.; Esteves, A.C.; Henriques, I.; Almeida, A.; Domingues, M.R.M.; Delgadillo, I.; Correia, A.; Cunha, A. Effects of UV Radiation on the Lipids and Proteins of Bacteria Studied by Mid-Infrared Spectroscopy. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 6306–6315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotoh, K.; Yasukawa, A.; Kobayashi, Y. Wettability Characteristics of Poly(Ethylene Terephthalate) Films Treated by Atmospheric Pressure Plasma and Ultraviolet Excimer Light. Polym. J. 2011, 43, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auffan, M.; Achouak, W.; Rose, J.; Roncato, M.A.; Chanéac, C.; Waite, D.T.; Masion, A.; Woicik, J.C.; Wiesner, M.R.; Bottero, J.Y. Relation between the Redox State of Iron-Based Nanoparticles and Their Cytotoxicity toward Escherichia coli. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 6730–6735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrega, J.; Fawcett, S.R.; Renshaw, J.C.; Lead, J.R. Silver Nanoparticle Impact on Bacterial Growth: Effect of PH, Concentration, and Organic Matter. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 7285–7290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element, Selected Orbital | AuAg-BSA-SPION | AuAg-BSA-SPION@pl-BPD-PET | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic % (Scan at 0°) | Atomic % (Scan at 0°) | Atomic % (Scan at 81°) | |

| C 1s | 82.6 | 62.6 | 63.1 |

| O 1s | 1.9 | 24.8 | 25.1 |

| N 1s | 11.0 | 8.5 | 7.7 |

| S 2p | 1.0 | 1.5 | 1.1 |

| Fe 2p | n.d. | 2.1 | 2.7 |

| Ag 3d | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| Au 4f | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lacmanová, V.; Svačinová, V.; Petr, M.; Slepička, P.; Průša, F.; Kvítek, O.; Kutová, A.; Řezníčková, A.; Šišková, K. Trimetallic Nanocomposites Grafted on Modified PET Substrate Revealing Antibacterial Effect Against Escherichia coli. Molecules 2025, 30, 4820. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244820

Lacmanová V, Svačinová V, Petr M, Slepička P, Průša F, Kvítek O, Kutová A, Řezníčková A, Šišková K. Trimetallic Nanocomposites Grafted on Modified PET Substrate Revealing Antibacterial Effect Against Escherichia coli. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4820. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244820

Chicago/Turabian StyleLacmanová, Veronika, Veronika Svačinová, Martin Petr, Petr Slepička, Filip Průša, Ondřej Kvítek, Anna Kutová, Alena Řezníčková, and Karolína Šišková. 2025. "Trimetallic Nanocomposites Grafted on Modified PET Substrate Revealing Antibacterial Effect Against Escherichia coli" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4820. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244820

APA StyleLacmanová, V., Svačinová, V., Petr, M., Slepička, P., Průša, F., Kvítek, O., Kutová, A., Řezníčková, A., & Šišková, K. (2025). Trimetallic Nanocomposites Grafted on Modified PET Substrate Revealing Antibacterial Effect Against Escherichia coli. Molecules, 30(24), 4820. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244820