Thermally Activated Composite Y2O3-bTiO2 as an Efficient Photocatalyst for Degradation of Azo Dye Reactive Black 5

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Structural Characterization

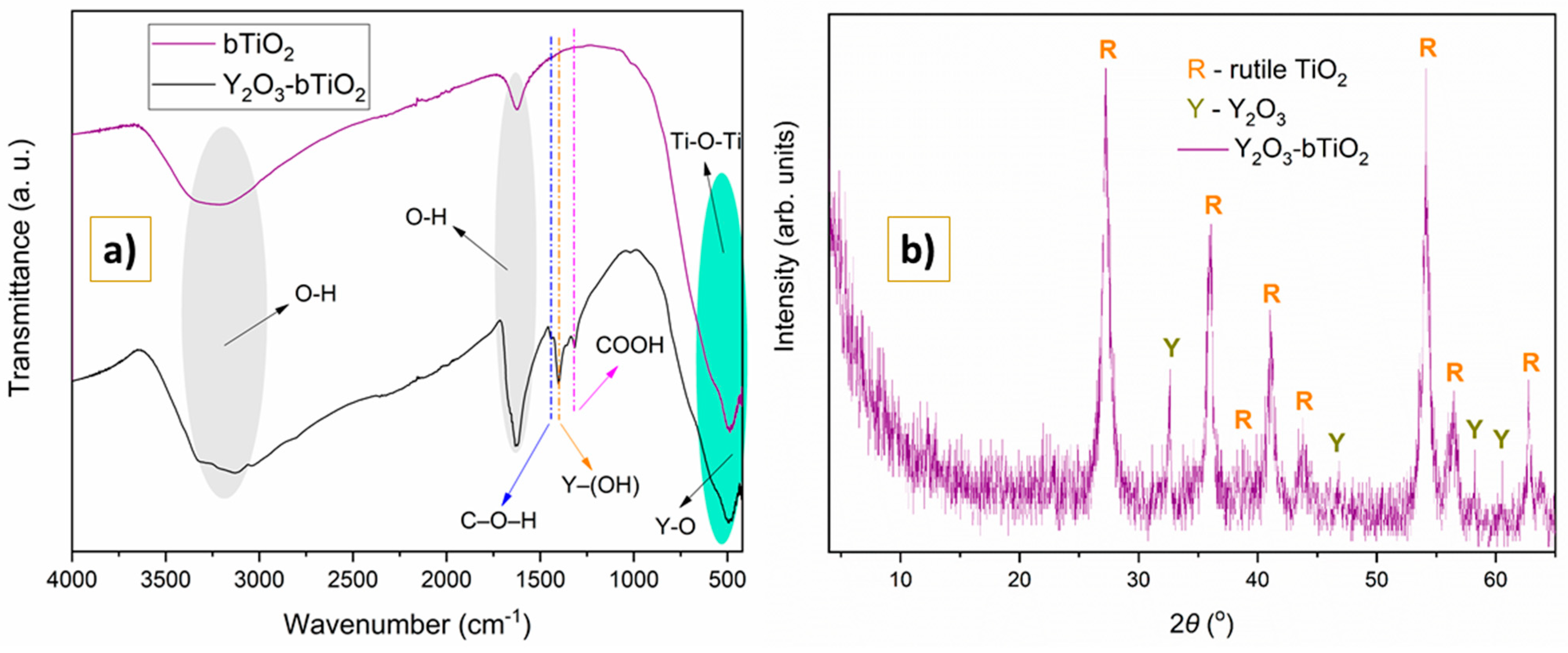

2.1.1. FTIR and XRD

2.1.2. SEM and EDX

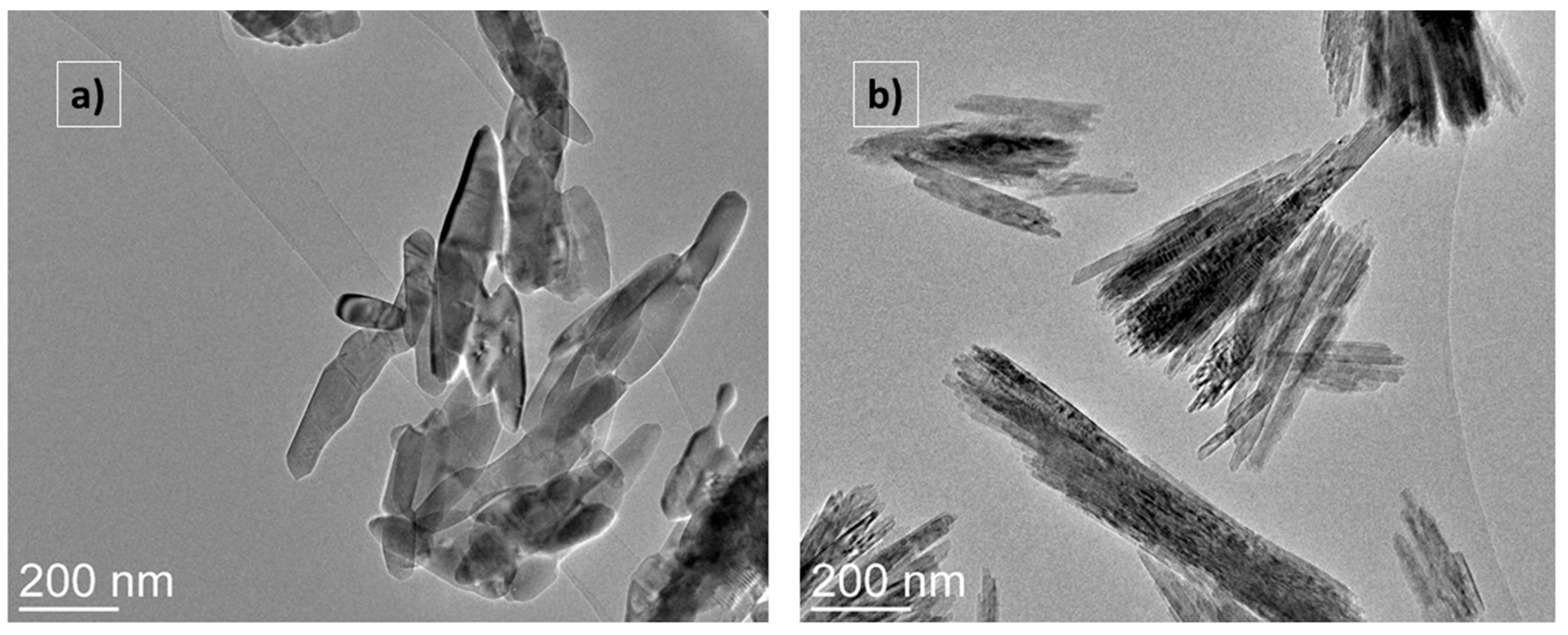

2.1.3. TEM

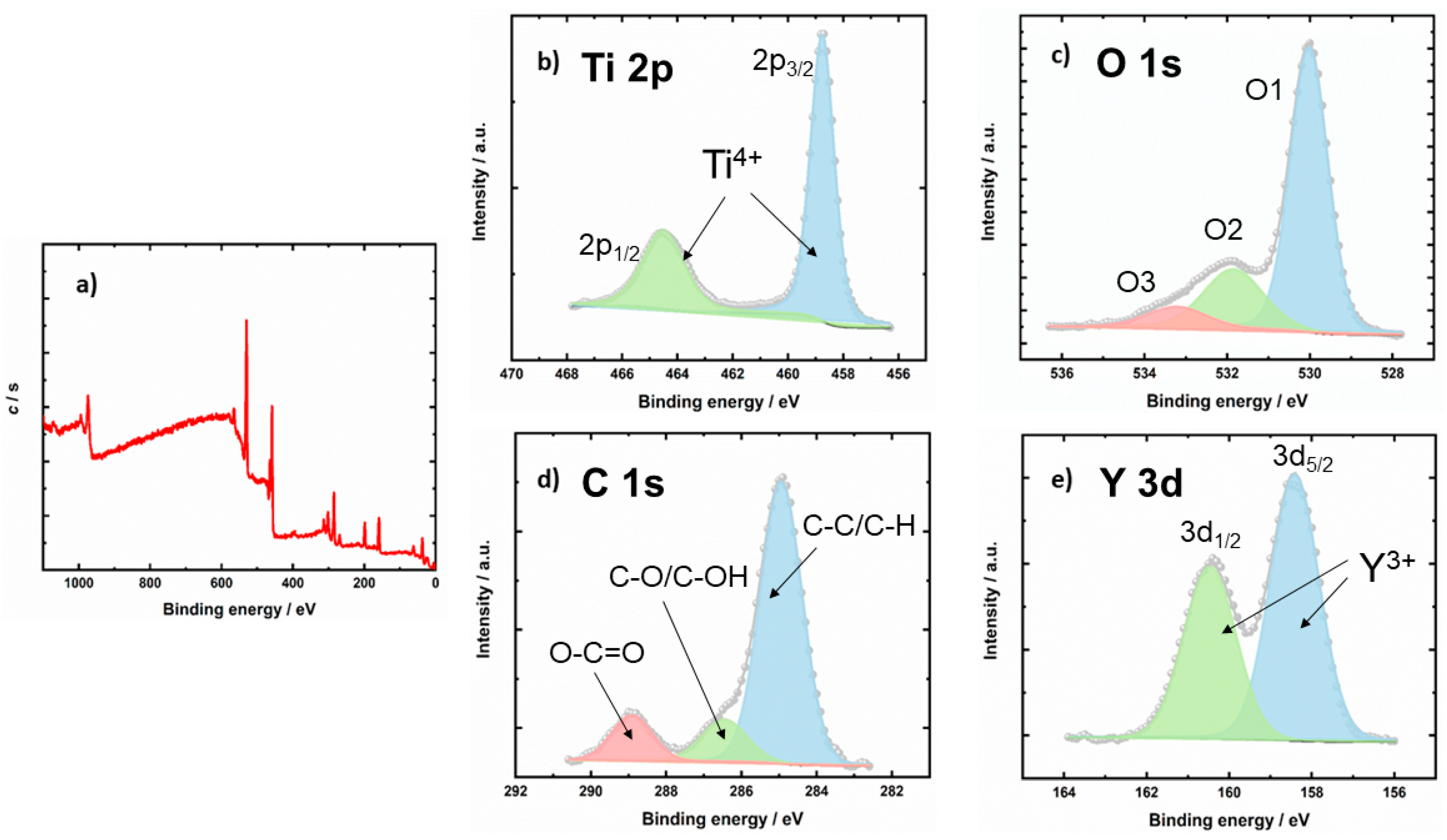

2.1.4. XPS

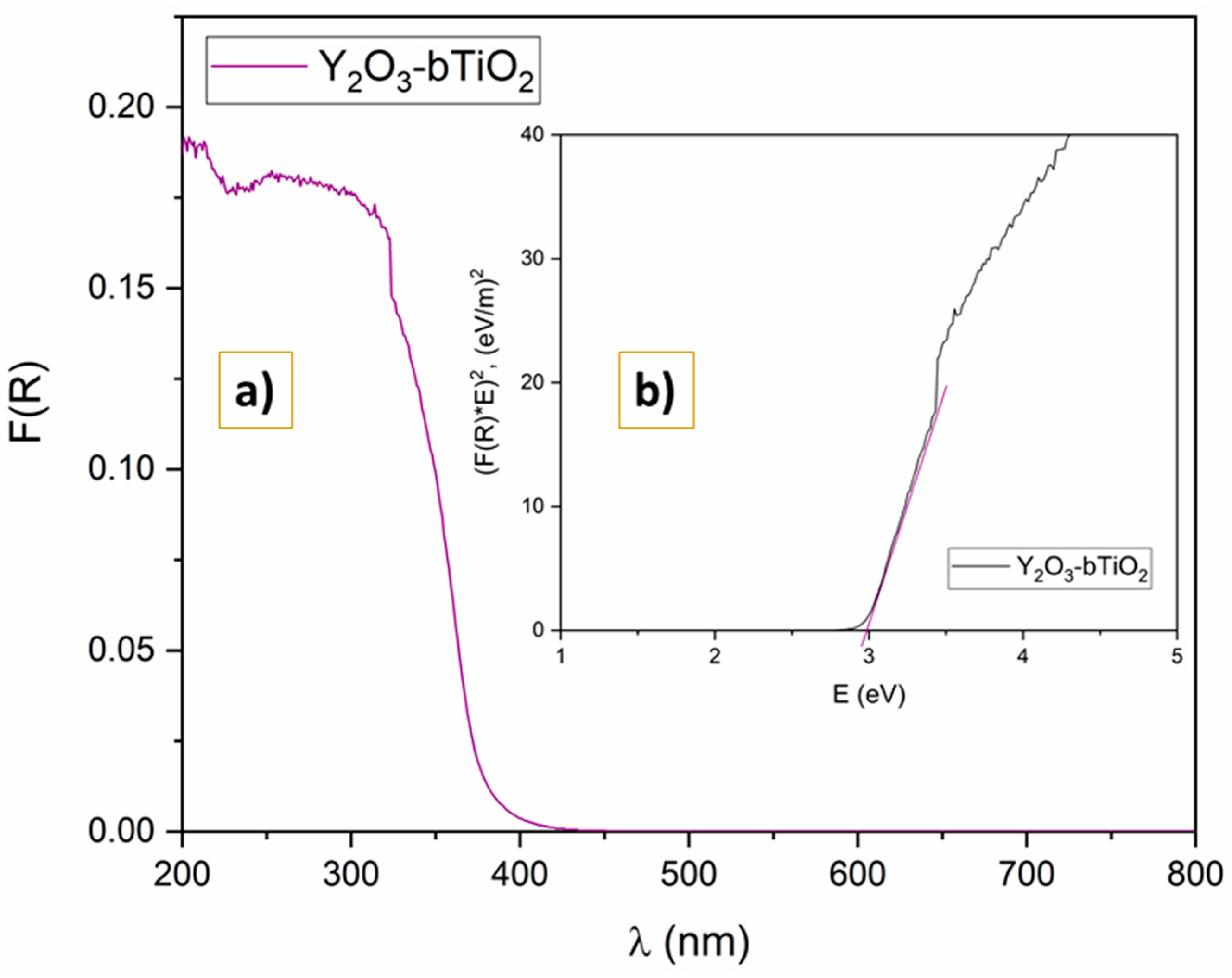

2.1.5. UV-DRS

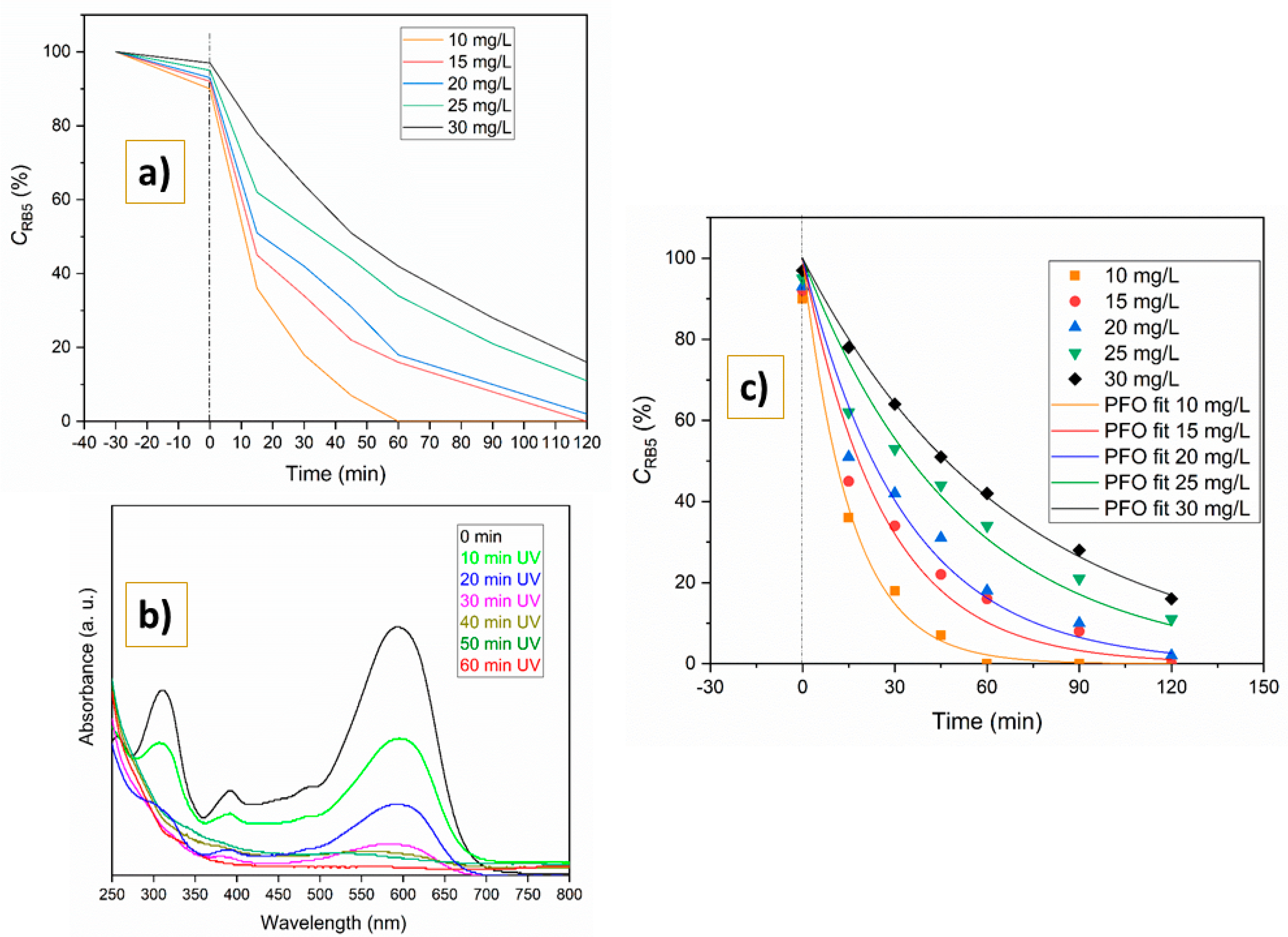

2.2. Photocatalytic Degradation

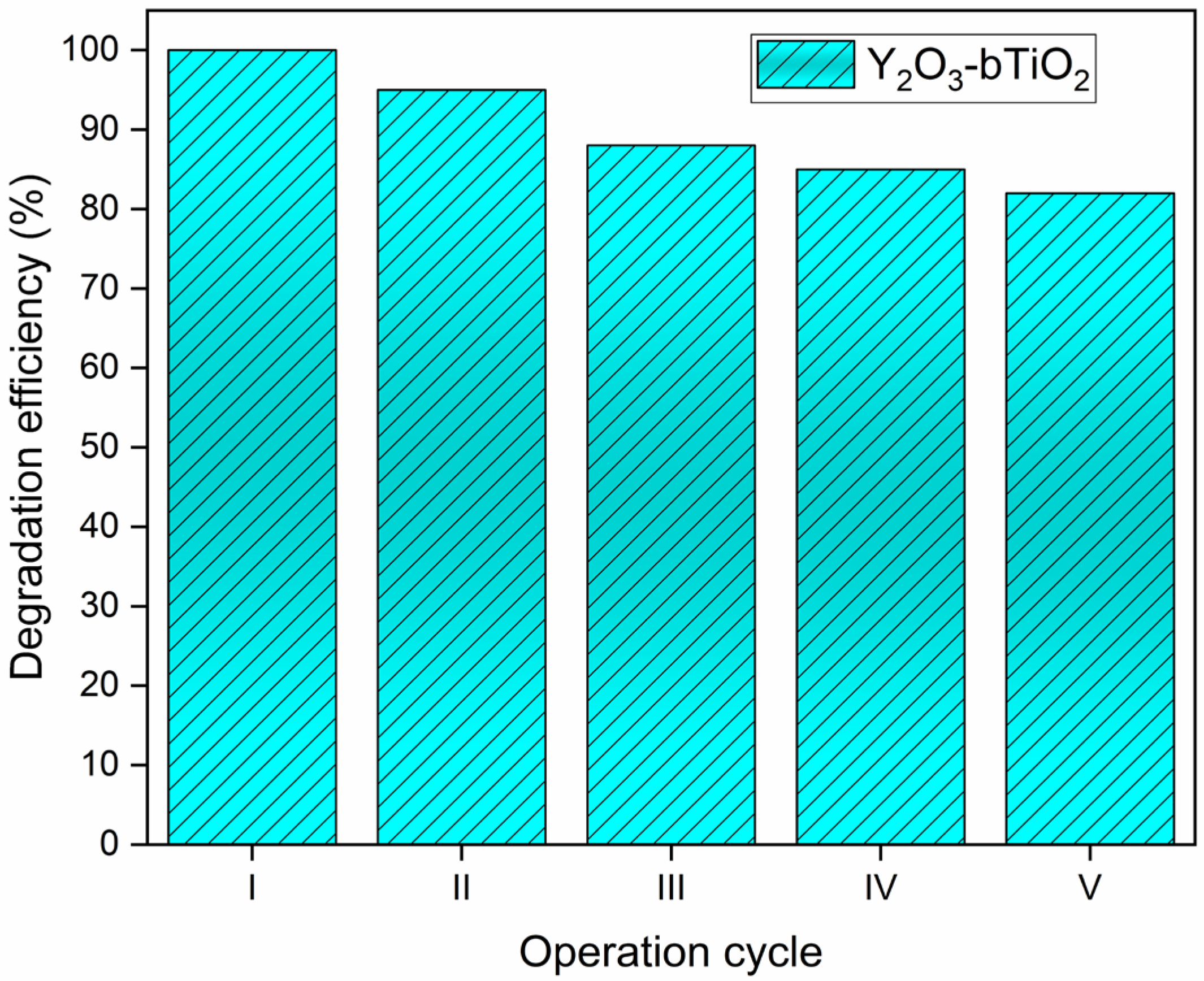

2.3. Quantum Yield and Multicycle Degradation

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Fabrication of Y2O3-bTiO2

4.1.1. Obtaining bTiO2 Particles

4.1.2. Preparation of Y2O3-bTiO2

4.2. Structural Characterization of Fabricated Composite

4.3. Photocatalytical Degradation of RB5

4.4. Degradation Kinetics and Quantum Yield Determination

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RB5 | Reactive Black 5 |

| AOPs | Advanced Oxidation Processes |

| PFO | Pseudo-First-Order |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| EDX | Energy-Dispersive X-Ray |

| XPS | X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy |

| UV/Vis | Ultraviolet–Visible Spectroscopy |

References

- Jovanovic, A.; Misic, M.; Vukovic, N.; Stojanovic, J.; Sokic, M. Photocatalytic Activity of Novely Obtained Biobased Mandarin Peels/TiO2 Particles toward Textile Dye. Sci. Sinter. 2025, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataya, G.; Issa, M.; Badran, A.; Cornu, D.; Bechelany, M.; Jellali, S.; Jeguirim, M.; Hijazi, A. Dynamic Removal of Methylene Blue and Methyl Orange from Water Using Biochar Derived from Kitchen Waste. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 29907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Mbarek, W.; Daza, J.; Escoda, L.; Fiol, N.; Pineda, E.; Khitouni, M.; Suñol, J.J. Removal of Reactive Black 5 Azo Dye from Aqueous Solutions by a Combination of Reduction and Natural Adsorbents Processes. Metals 2023, 13, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuervo Lumbaque, E.; Gomes, M.F.; Da Silva Carvalho, V.; de Freitas, A.M.; Tiburtius, E.R.L. Degradation and Ecotoxicity of Dye Reactive Black 5 after Reductive-Oxidative Process: Environmental Science and Pollution Research. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 6126–6134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djokić, V.; Vujović, J.; Marinković, A.; Petrović, R.; Janaćković, D.; Onjia, A.; Mijin, D. A Study of the Photocatalytic Degradation of the Textile Dye CI Basic Yellow 28 in Water Using a P160 TiO2-Based Catalyst. J. Serbian Chem. Soc. 2012, 77, 1747–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armaković, S.; Kudus, M.; Jovanoski Kostić, A.; Savanović, M. Comparison of Photocatalytic Performance of Sr0.9La0.1TiO3 and Sr0.25Ca0.25Na0.25Pr0.25TiO3 Towards Metoprolol and Pindolol Photodegradation. Metall. Mater. Data 2023, 1, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnabi, M.K.A.; Ghazy, M.A.; Ali, S.S.; Eltarahony, M.; Nassrallah, A. Efficient Biodegradation and Detoxification of Reactive Black 5 Using a Newly Constructed Bacterial Consortium. Microb. Cell Factories 2025, 24, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armaković, S.J.; Savanović, M.M.; Armaković, S. Titanium Dioxide as the Most Used Photocatalyst for Water Purification: An Overview. Catalysts 2023, 13, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahasan, T.; Edirisooriya, E.M.N.T.; Senanayake, P.S.; Xu, P.; Wang, H. Advanced TiO2-Based Photocatalytic Systems for Water Splitting: Comprehensive Review from Fundamentals to Manufacturing. Molecules 2025, 30, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuama, A.N.; Abass, K.H.; Rabee, B.H.; Alnayl, R.S.; Alzubaidi, L.H.; Salman, Z.N.; Agam, M.A.b. Electron Donors’ Approach to Enhance Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production of TiO2: A Critical Review. Transit. Met. Chem. 2025, 50, 863–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukrey, N.A.; Bushroa, A.R.; Rizwan, M. Dopant Incorporation into TiO2 Semiconductor Materials for Optical, Electronic, and Physical Property Enhancement: Doping Strategy and Trend Analysis. J. Aust. Ceram. Soc. 2024, 60, 563–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikolajczyk, A.; Wyrzykowska, E.; Mazierski, P.; Grzyb, T.; Wei, Z.; Kowalska, E.; Caicedo, P.N.A.; Zaleska-Medynska, A.; Puzyn, T.; Nadolna, J. Visible-Light Photocatalytic Activity of Rare-Earth-Metal-Doped TiO2: Experimental Analysis and Machine Learning for Virtual Design. Appl. Catal. B 2024, 346, 123744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, Y.; Gareso, P.L.; Tahir, D. Review: Influence of Synthesis Methods and Performance of Rare Earth Doped TiO2 Photocatalysts in Degrading Dye Effluents. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 22, 1975–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zheng, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Yan, K.; Wang, J.; Zhu, K. Synergistic Effect of Y Doping and Reduction of TiO2 on the Improvement of Photocatalytic Performance. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, G.; Tan, Y.; Guan, Y.; Zhou, L.; Cui, L.; Choi, S.W.; Li, M.X. Preparation of Y2O3/TiO2-Loaded Polyester Fabric and Its Photocatalytic Properties under Visible Light Irradiation. Polymers 2022, 14, 2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirm’, M.; Feldbach, E.; Kink, R.; Lushchik, A.; Lushchik, C.; Maaroos, A.; Martinson, I. Mechanisms of Intrinsic and Impurity Luminescence Excitation by Synchrotron Radiation in Wide-Gap Oxides. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 1996, 79, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, J.L.; Chakraborty, S.; Vijayarangan, D.R. Toxicity Studies on Danio rerio (Zebrafish) Models Using Yttrium Oxide Nanoparticles from Hygrophila Auriculata and Their Potential Biological and Environmental Applications. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2025, 44, 2787–2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Peng, Z.; Gao, Y.; You, F.; Yao, C. Preparation and Visible-Light Photocatalytic Activity of Ag-Loaded TiO2@Y2O3 Hollow Microspheres with Double-Shell Structure. Powder Technol. 2021, 377, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Singh, A.; Sharma, A.; Prerna; Verma, S.; Mahajan, S.; Arya, S. Investigating the Thermographical Effect on Optical Properties of Eu Doped Y2O3:TiO2 Nanocomposite Synthesized via Sol-Gel Method. Solid State Sci. 2021, 116, 106617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlovskiy, A.L.; Zhumatayeva, I.Z.; Mustahieva, D.; Zdorovets, M.V. Phase Transformations and Photocatalytic Activity of Nanostructured Y2O3/TiO2-Y2TiO5 Ceramic Such as Doped with Carbon Nanotubes. Molecules 2020, 25, 1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhandayuthapani, T.; Sivakumar, R.; Ilangovan, R. Growth of Micro Flower Rutile TiO2 Films by Chemical Bath Deposition Technique: Study on the Properties of Structural, Surface Morphological, Vibrational, Optical and Compositional. Surf. Interfaces 2016, 4, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasieczna-Patkowska, S.; Cichy, M.; Flieger, J. Application of Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy in Characterization of Green Synthesized Nanoparticles. Molecules 2025, 30, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garduño-Wilches, I.A.; Alarcón-Flores, G.; Carmona-Téllez, S.; Guzmán, J.; Aguilar-Frutis, M. Luminescent Properties of Y(OH)3: Tb Nanopowders Synthesized by Microwave-Assisted Hydrothermal Method. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2019, 21, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egerić, M.; Matović, L.; Pilić, B.; Nešić, A.; Vranješ-Djurić, S.; Radović, M.; Vujasin, R. Electrospun MOF-Loaded Polyamide Membranes for Y3+ Radioisotopes Removal. Metall. Mater. Data 2023, 2, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisz, A.D.; Rodenas, L.G.; Morando, P.J.; Regazzoni, A.E.; Blesa, M.A. FTIR Study of the Adsorption of Single Pollutants and Mixtures of Pollutants onto Titanium Dioxide in Water: Oxalic and Salicylic Acids. Catal. Today 2002, 76, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, Z.; Zhen, F.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, R.; Selim, F.A.; Wong, C.; Chen, H. High Sinterability Nano-Y2O3 Powders Prepared via Decomposition of Hydroxyl-Carbonate Precursors for Transparent Ceramics. J. Mater. Sci. 2017, 52, 8556–8567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatsepin, A.; Kuznetsova, Y.; Zatsepin, D.; Wong, C.H.; Law, W.C.; Tang, C.Y.; Gavrilov, N. Exciton Luminescence and Optical Properties of Nanocrystalline Cubic Y2O3 Films Prepared by Reactive Magnetron Sputtering. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu-Jaureguí, C.; Andronic, L.; Sepúlveda-Escribano, A.; Silvestre-Albero, J. Improved Photocatalytic Performance of TiO2/Carbon Photocatalysts: Role of Carbon Additive. Environ. Res. 2024, 251, 118672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Sun, H.; Xia, W.; He, J.; Han, J. Enhanced Photocatalytic Performance of Carbon Fiber Paper Supported TiO2 under the Ultrasonic Synergy Effect. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 22922–22930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, F.; Zhang, G.; Wang, Y.; Gao, C.; Chen, L.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, Z.; Xie, E. The Role of Carbon in the Photocatalytic Reaction of Carbon/TiO2 Photocatalysts. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 320, 703–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuvarega, A.T.; Mamba, B.B. TiO2-Based Photocatalysis: Toward Visible Light-Responsive Photocatalysts Through Doping and Fabrication of Carbon-Based Nanocomposites. Crit. Rev. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2017, 42, 295–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Guo, S.; Wang, H.; Li, X.; Wu, Z. Enhancement of the Visible Light Photocatalytic Activity of C-Doped TiO2 Nanomaterials Prepared by a Green Synthetic Approach. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 13285–13292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Yeon Yun, C.; Sun Hahn, M.; Lee, J.; Yi, J. Synthesis and Characterization of Carbon-Doped Titania as a Visible-Light-Sensitive Photocatalyst. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2008, 25, 892–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shard, A.G.; Reed, B.P.; Cant, D.J.H. Surface Analysis Insight Note: Uncertainties in XPS Elemental Quantification. Surf. Interface Anal. 2025, 57, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesinger, M.C.; Payne, B.P.; Hart, B.R.; Grosvenor, A.P.; McIntryre, N.S.; Lau, L.W.M.; Smart, R.S.C. Quantitative Chemical State XPS Analysis of First Row Transition Metals, Oxides and Hydroxides. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2008, 100, 012025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.D.; Payne, B.P.; McIntyre, N.S.; Biesinger, M.C. Enhancing Oxygen Spectra Interpretation by Calculating Oxygen Linked to Adventitious Carbon. Surf. Interface Anal. 2025, 57, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grey, L.H.; Nie, H.Y.; Biesinger, M.C. Defining the Nature of Adventitious Carbon and Improving Its Merit as a Charge Correction Reference for XPS. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 653, 159319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.-Y.; Park, E.K.; Raju, K.; Lee, H.-K. Microstructure and TEM/XPS Characterization of YOF Layers on Y2O3 Substrates Modified via NH4F Salt Solution Treatment. J. Korean Ceram. Soc. 2025, 62, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siva Rao, T.; Segne, T.A.; Susmitha, T.; Balaram Kiran, A.; Subrahmanyam, C. Photocatalytic Degradation of Dichlorvos in Visible Light by Mg2+-TiO2 Nanocatalyst. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2012, 2012, 168780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, E.; Vijayarangamuthu, K.; Youn, J.S.; Park, Y.K.; Jung, S.C.; Jeon, K.J. Degussa P25 TiO2 Modified with H2O2 under Microwave Treatment to Enhance Photocatalytic Properties. Catal. Today 2018, 303, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karcıoğlu Karakaş, Z.; Dönmez, Z. A Sustainable Approach in the Removal of Pharmaceuticals: The Effects of Operational Parameters in the Photocatalytic Degradation of Tetracycline with MXene/ZnO Photocatalysts. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Cai, M.; Li, J.; Zhang, W. Study on Photocatalytic Performance of Bi2O3-TiO2/Powdered Activated Carbon Composite Catalyst for Malachite Green Degradation. Water 2025, 17, 1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.A.; Mahmoud, S.A.; Mohamed, A.A. Interfacially Engineered Metal Oxide Nanocomposites for Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Pollutants and Energy Applications. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 15561–15603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saint, U.K.; Chandra Baral, S.; Sasmal, D.; Maneesha, P.; Datta, S.; Naushin, F.; Sen, S. Effect of PH on Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue in Water by Facile Hydrothermally Grown TiO2 Nanoparticles under Natural Sunlight. JCIS Open 2025, 19, 100150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, V.; Coppola, G.; Calabrò, V.; Chakraborty, S.; Candamano, S.; Algieri, C. Heterogeneous TiO2 Photocatalysis Coupled with Membrane Technology for Persistent Contaminant Degradation: A Critical Review. Appl. Water Sci. 2025, 15, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Dong, W.; Huang, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhou, J.L.; Li, W. Photocatalysis for Sustainable Energy and Environmental Protection in Construction: A Review on Surface Engineering and Emerging Synthesis. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 117529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, H.; Tang, A. Optical, Electrochemical and Hydrophilic Properties of Y2O3 Doped TiO2 Nanocomposite Films. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 16271–16279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi-Galangash, M.; Mousavi, S.K.; Shirzad-Siboni, M. Photocatalytic Degradation of Reactive Black 5 from Synthetic and Real Wastewater under Visible Light with TiO2 Coated PET Photocatalysts. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaison, A.; Mohan, A.; Lee, Y.C. Recent Developments in Photocatalytic Nanotechnology for Purifying Air Polluted with Volatile Organic Compounds: Effect of Operating Parameters and Catalyst Deactivation. Catalysts 2023, 13, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorakopoulos, G.V.; Papageorgiou, S.K.; Katsaros, F.K.; Romanos, G.E.; Beazi-Katsioti, M. Investigation of MO Adsorption Kinetics and Photocatalytic Degradation Utilizing Hollow Fibers of Cu-CuO/TiO2 Nanocomposite. Materials 2024, 17, 4663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallick, P.; Rath, C.; Prakash, J.; Mishra, D.K.; Choudhary, R.J.; Phase, D.M.; Tripathi, A.; Avasthi, D.K.; Kanjilal, D.; Mishra, N.C. Swift Heavy Ion Irradiation Induced Modification of the Microstructure of NiO Thin Films. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 2010, 268, 1613–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talebian-Kiakalaieh, A.; Hashem, E.M.; Guo, M.; Ran, J.; Qiao, S.Z. Single Atom Extracting Photoexcited Holes for Key Photocatalytic Reactions. Adv. Energy Mater. 2025, 15, e2501945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Guo, T.; Hu, P. The Influence of Defect Engineering on the Electronic Structure of Active Centers on the Catalyst Surface. Catalysts 2025, 15, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranovskyi, D.; Kolesnichenko, V.; Tyschenko, N.; Lobunets, T.; Shyrokov, O.; Baranovska, O.; Ragulya, A. Crystallization Kinetics of Nano-Sized Amorphous TiO2 during Transformation to Anatase under Non-Isothermal Conditions. Next Mater. 2025, 9, 101106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozael, M.M.; Dong, Z.; Shi, J.; Kear, B.H.; Tse, S.D. Synthesis of Tungsten-Doped TiO2 Nano-Onions via a Layered Amorphous-to-Crystalline Phase Transition Prepared by Reactive Laser Ablation in Liquid with Post Heat Treatment. Powder Technol. 2025, 465, 121319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, S.; Hou, Y.; Chen, H.; Deng, D.; Yang, Z.; Xue, S.; Zhu, R.; Diao, Z.; Chu, W. An Efficient Photocatalyst for Fast Reduction of Cr(VI) by Ultra-Trace Silver Enhanced Titania in Aqueous Solution. Catalysts 2018, 8, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Dhaliwal, A.S. Plasmon-Induced Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue Dye Using Biosynthesized Silver Nanoparticles as Photocatalyst. Environ. Technol. 2020, 41, 1520–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, K.; Hu, X.Y.; Chen, B.Y.; Hsueh, C.C.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, J.; Lin, Y.J.; Chang, C.T. Synthesized TiO2/ZSM-5 Composites Used for the Photocatalytic Degradation of Azo Dye: Intermediates, Reaction Pathway, Mechanism and Bio-Toxicity. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 383, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, M.N.; Cho, Y.J.; Poh, P.E.; Jin, B. Evaluation of Titanium Dioxide Photocatalytic Technology for the Treatment of Reactive Black 5 Dye in Synthetic and Real Greywater Effluents. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 89, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, M.N.; Jin, B. Photocatalytic Treatment of High Concentration Carbamazepine in Synthetic Hospital Wastewater. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 199–200, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, D.K.; Patel, U.D. Photocatalytic Degradation of Reactive Black 5 Using Ag3PO4 under Visible Light. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2021, 149, 109768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, A.; Gopalram, K.; Appunni, S. Photocatalytic Degradation of 2,4-Dicholorophenoxyacetic Acid by TiO2 Modified Catalyst: Kinetics and Operating Cost Analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 33331–33343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, G.; Xing, W.; Lan, Z.A.; Wang, S.; Pan, Z. Breaking Interfacial Charge Transport Limitations of Carbon Nitride-Based Homojunction by Lattice-Matched Interfacial Engineering for Enhanced Photocatalytic Overall Water Splitting. ACS Catal. 2025, 15, 13167–13178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mančić, L.; Del Rosario, G.; Stanojević, Z.V.M.; Milošević, O. Phase Evolution in Ce-Doped Yttrium-Aluminum-Based Particles Derived from Aerosol. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2007, 27, 4329–4332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinina, E.G.; Kundikova, N.D.; Kuznetsov, D.K.; Ivanov, M.G. Electrophoretic Deposition of One- and Two-Layer Compacts of Holmium and Yttrium Oxide Nanopowders for Magneto-Optical Ceramics Fabrication. Magnetochemistry 2023, 9, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elezović, N.R.; Babić, B.M.; Radmilovic, V.R.; Vračar, L.M.; Krstajić, N.V. Novel Pt Catalyst on Ruthenium Doped TiO2 Support for Oxygen Reduction Reaction. Appl. Catal. B 2013, 140–141, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanović, A.A.; Bugarčić, M.D.; Sokić, M.D.; Barudžija, T.S.; Pavićević, V.P.; Marinković, A.D. Photodegradation of Thiophanate-Methyl under Simulated Sunlight by Utilization of Novel Composite Photocatalysts. Chem. Ind. 2024, 78, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinshelwood, C. The Kinetics of Chemical Change in Gaseous Systems, 1st ed.; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Jovanović, A.; Stevanović, M.; Barudžija, T.; Cvijetić, I.; Lazarević, S.; Tomašević, A.; Marinković, A. Advanced Technology for Photocatalytic Degradation of Thiophanate-Methyl: Degradation Pathways, DFT Calculations and Embryotoxic Potential. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2023, 178, 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Sivey, J.D.; Dai, N. Emerging Investigator Series: Sunlight Photolysis of 2,4-D Herbicides in Systems Simulating Leaf Surfaces. Environ. Sci. Process Impacts 2018, 20, 1123–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | C | O | Ti | Cl | Y |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bTiO2 | 29 | 53.3 | 17.7 | 0 | 0 |

| Y2O3-bTiO2 | 33.7 | 45.7 | 12.7 | 4.9 | 3 |

| C0(RB5) (mg/L) | k ± SD * (min−1) | t0.5 (min) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 0.064 ± 0.0058 | 10.9 | 0.98 |

| 15 | 0.038 ± 0.0041 | 13.1 | 0.95 |

| 20 | 0.030 ± 0.0029 | 15.9 | 0.95 |

| 25 | 0.019 ± 0.0016 | 34.6 | 0.95 |

| 30 | 0.015 ± 0.00035 | 46.2 | 0.99 |

| C0(RB5) (mg/L) | Φ |

|---|---|

| 10 | 0.61 |

| 15 | 0.36 |

| 20 | 0.27 |

| 25 | 0.16 |

| 30 | 0.11 |

| Pollutant | C0 (mg/L) | Catalyst | k (min−1) | Degradation Time (min) | Efficiency (%) | Catalyst Amount (mg/L) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenol | 19.75 | Y-TiO2 | 0.0026 | - | 14 | 5 | [12] |

| Methyl orange | 10 | Y-TiO2-H2 | 0.1746 | 80 | 99 | 100 | [14] |

| Reactive Black 5 | 20 | Y2O3/TiO2-Loaded Polyester Fabric | 0.47846 | 150 | 83 | - | [15] |

| Methyl orange | 20 | Ag-TiO2/Y2O3 | 0.00984 | 180 | 80.3 | 1000 | [18] |

| Methyl orange | 25 | Y2O3/TiO2-Y2TiO5/CNTs | - | 90 | 90 | - | [20] |

| Reactive Black 5 | 10 | Y2O3/bTiO2 | 0.064 | 90 | 99 | 200 | Our study |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jovanović, A.; Bugarčić, M.; Petrović, J.; Simić, M.; Žagar Soderžnik, K.; Kovač, J.; Sokić, M. Thermally Activated Composite Y2O3-bTiO2 as an Efficient Photocatalyst for Degradation of Azo Dye Reactive Black 5. Molecules 2026, 31, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010008

Jovanović A, Bugarčić M, Petrović J, Simić M, Žagar Soderžnik K, Kovač J, Sokić M. Thermally Activated Composite Y2O3-bTiO2 as an Efficient Photocatalyst for Degradation of Azo Dye Reactive Black 5. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleJovanović, Aleksandar, Mladen Bugarčić, Jelena Petrović, Marija Simić, Kristina Žagar Soderžnik, Janez Kovač, and Miroslav Sokić. 2026. "Thermally Activated Composite Y2O3-bTiO2 as an Efficient Photocatalyst for Degradation of Azo Dye Reactive Black 5" Molecules 31, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010008

APA StyleJovanović, A., Bugarčić, M., Petrović, J., Simić, M., Žagar Soderžnik, K., Kovač, J., & Sokić, M. (2026). Thermally Activated Composite Y2O3-bTiO2 as an Efficient Photocatalyst for Degradation of Azo Dye Reactive Black 5. Molecules, 31(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010008