Preparation of ESAT6-Fc Fusion Protein and Its Therapeutic Efficacy and Immune Mechanisms in Allergic Asthma Mice via Intranasal Immunization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

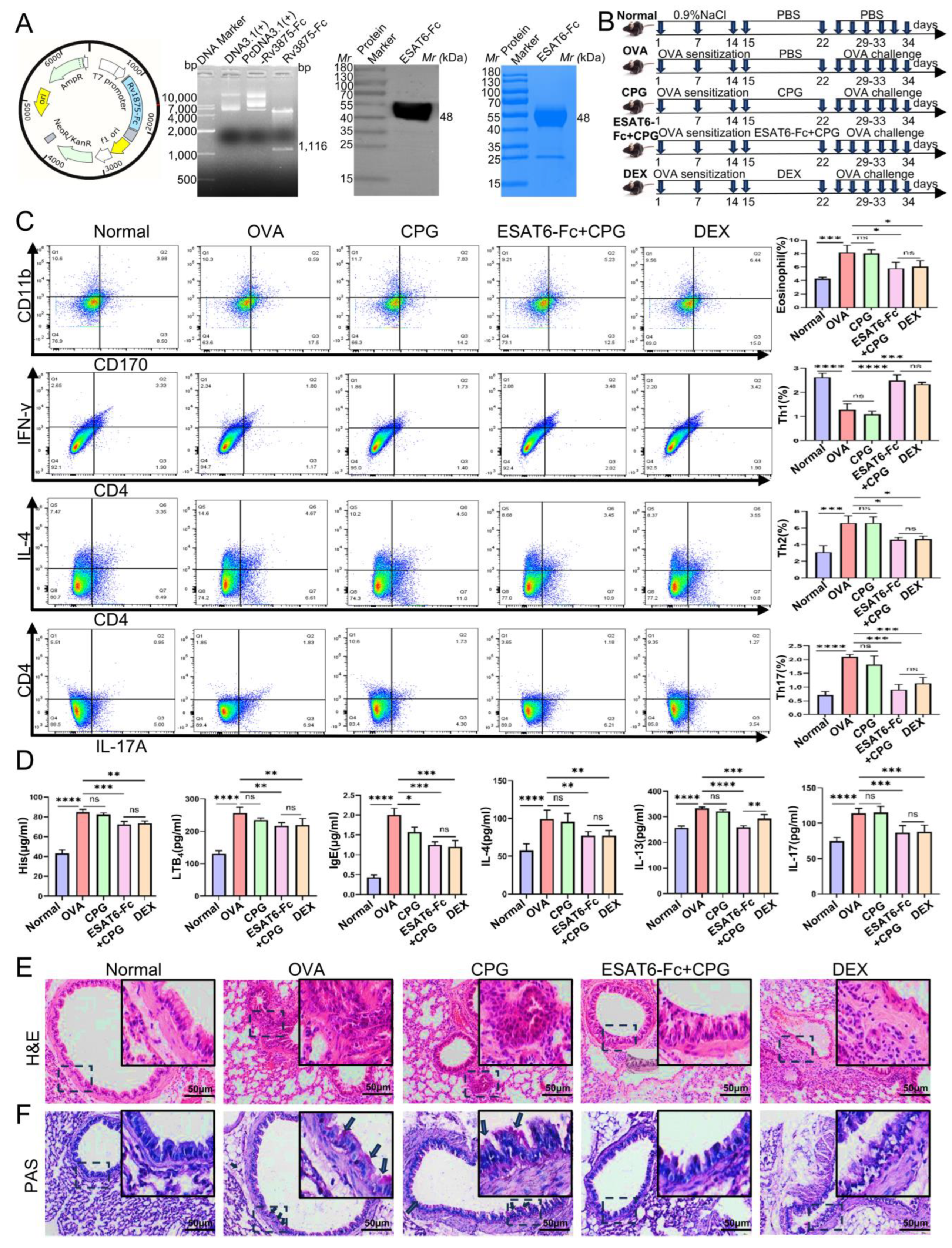

2.1. Effects of ESAT6-Fc Fusion Protein on Allergic Asthma Model Mice

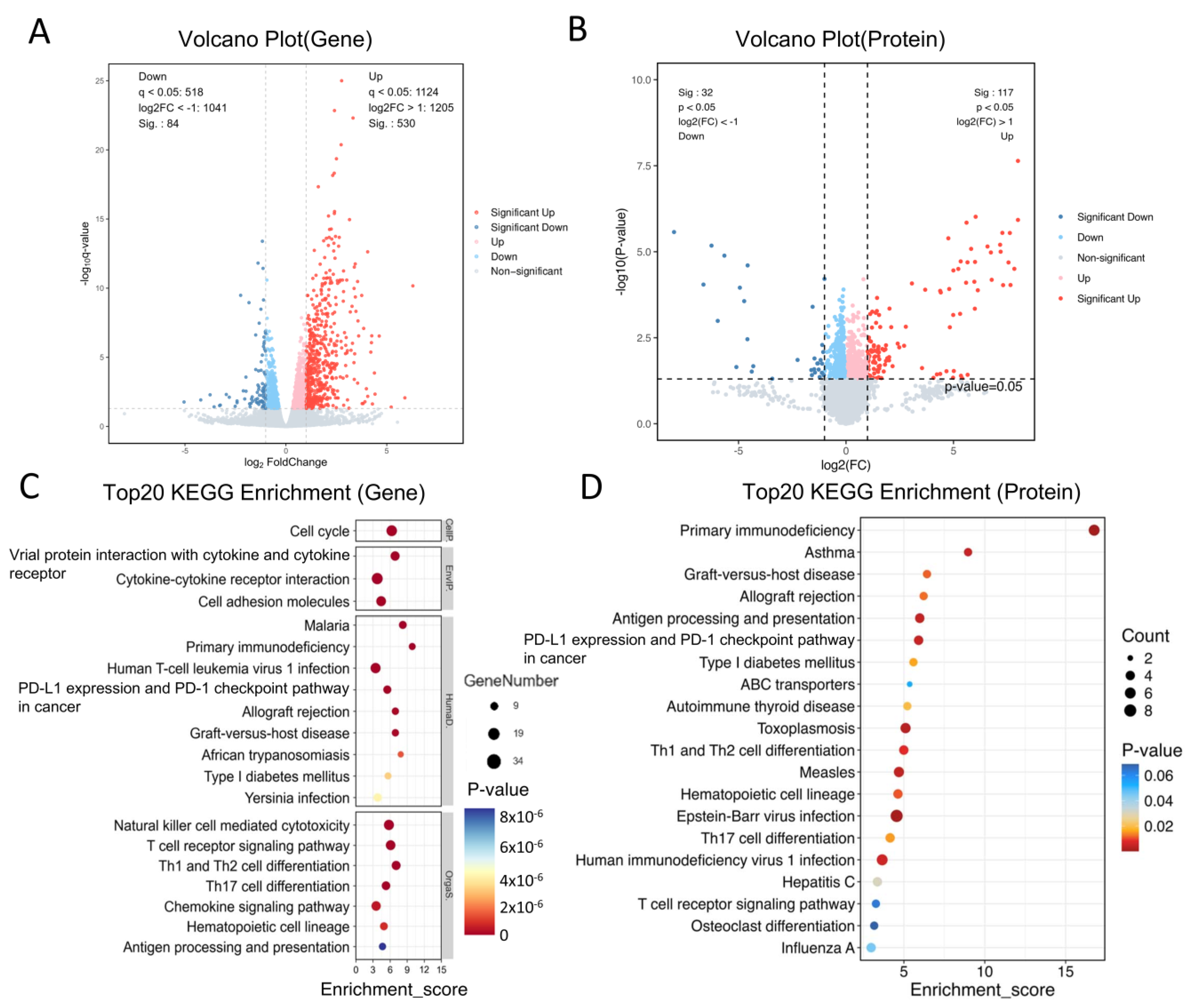

2.2. Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) and Proteins (DEPs) Between the Normal and OVA Groups

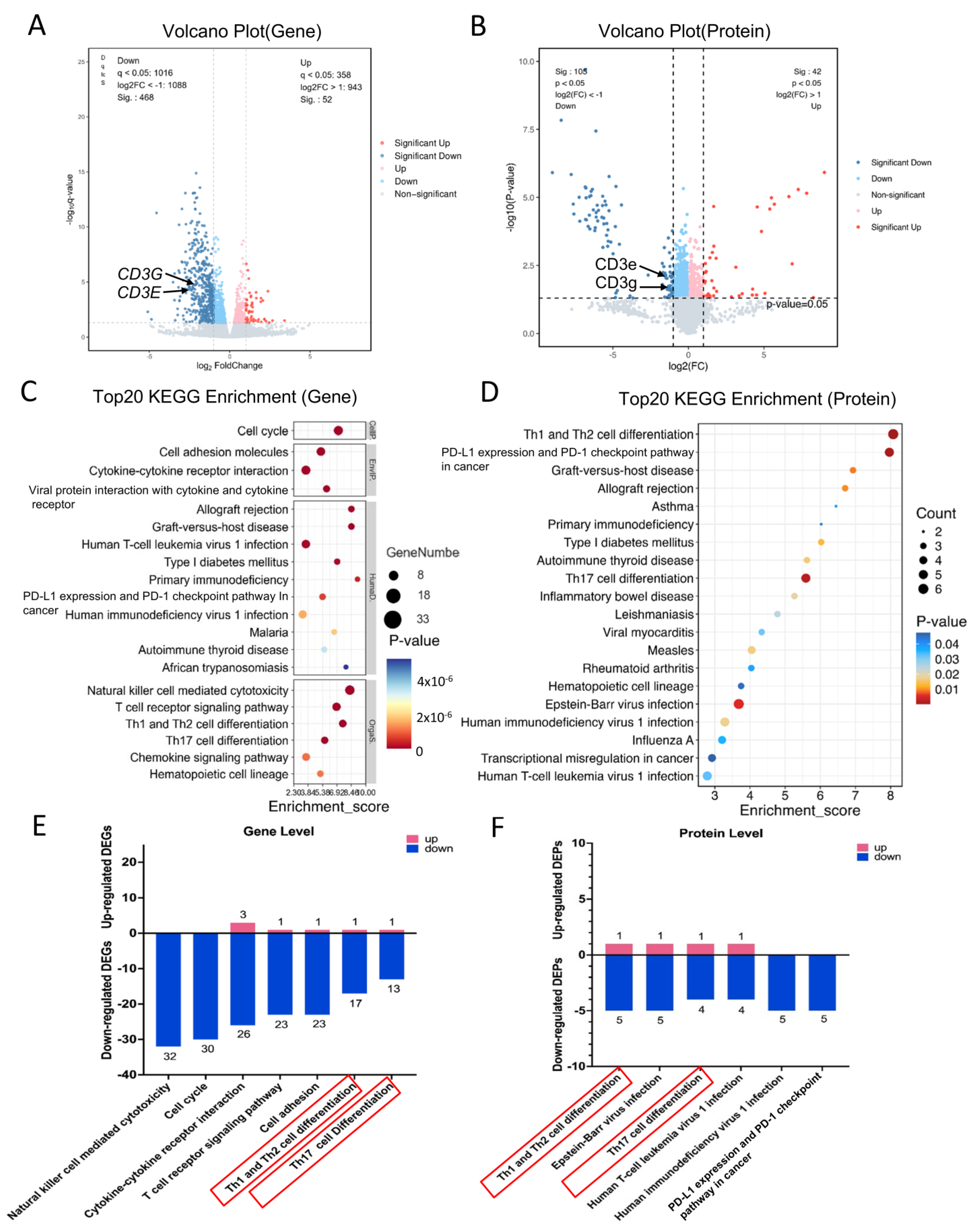

2.3. DEGs and DEPs After Treatment with the ESAT6-Fc Fusion Protein

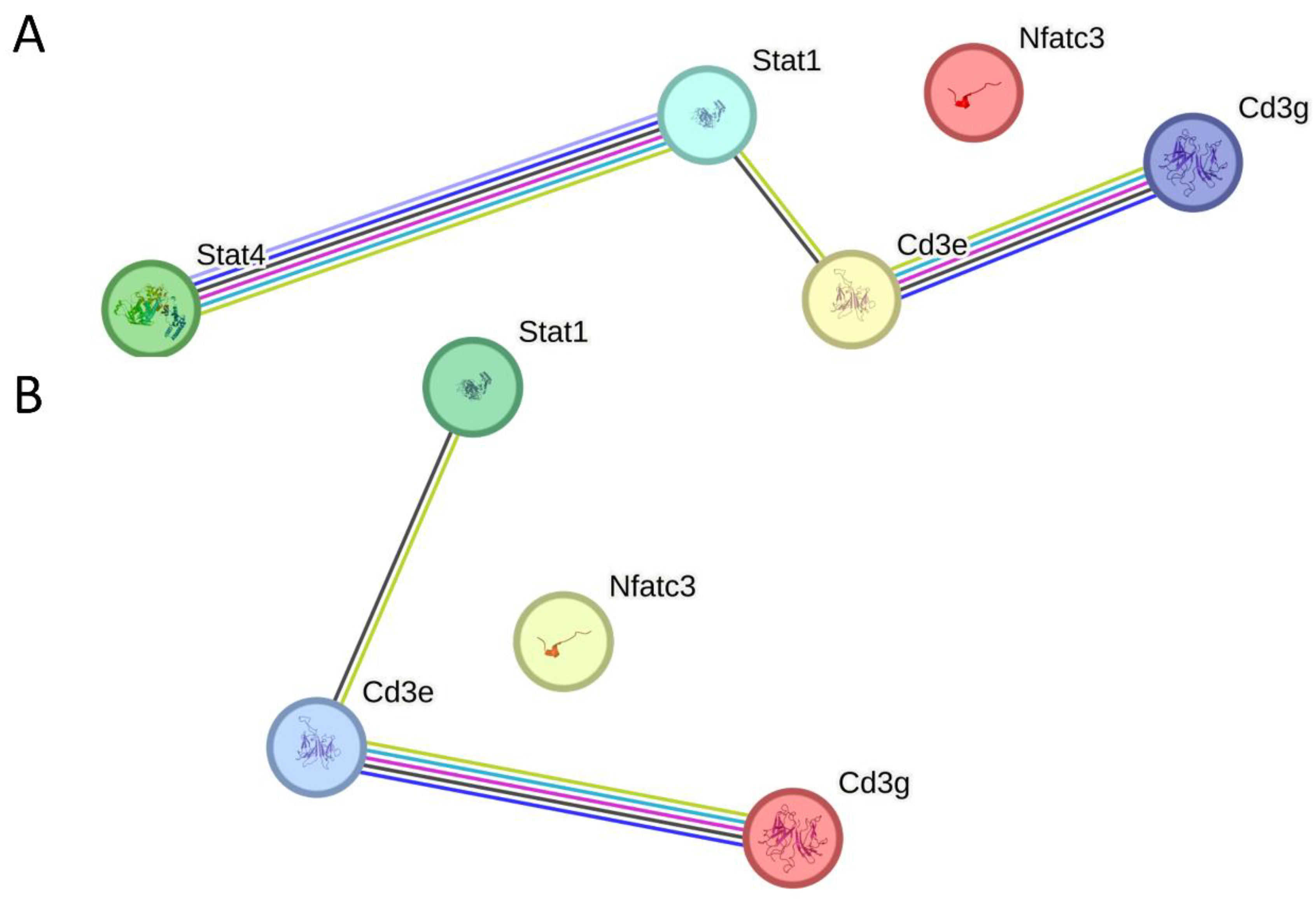

2.4. DEGs and DEPs Regulated by the ESAT6 Protein

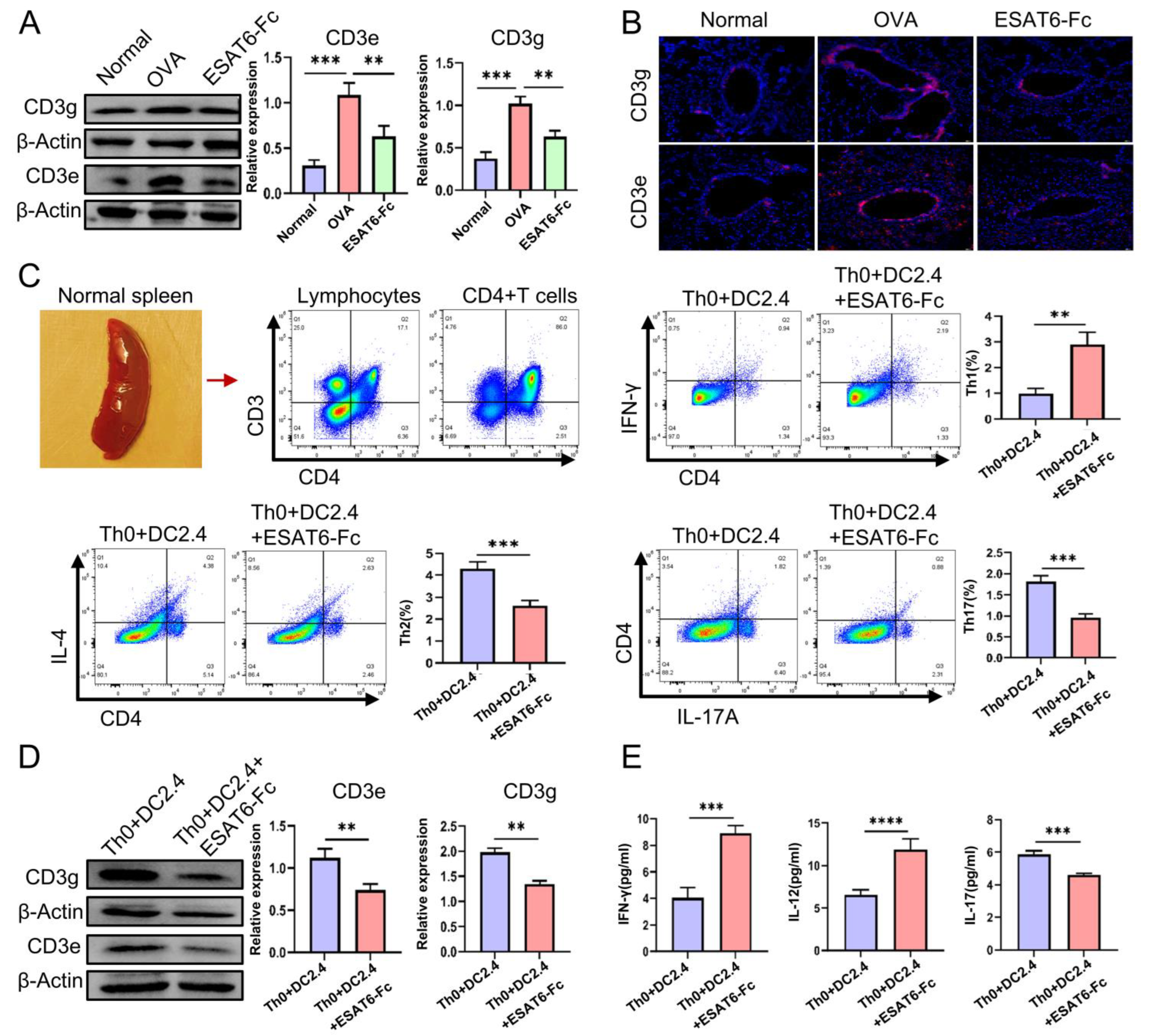

2.5. Validation Experiments

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Construction of pcDNA3.1(+)-Rv3875-Fc and Preparation of ESAT6-Fc Fusion Protein

4.2. Animal Grouping, Allergic Asthma Mouse Model and Drug Treatment

4.3. Flow Cytometry Analysis

4.4. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

4.5. Histological Analysis

4.6. cDNA Library Construction and Transcriptomic Analysis

4.7. Tandem Mass Tag (TMT)-Labeled Proteomics and Protein Quantification

4.8. Cells and Cell Treatment

4.9. Western Blot Analysis

4.10. Fluorescence Analysis

4.11. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ESAT6 | 6 kDa early secretory antigenic target |

| M.tb | Mycobacterium tuberculosis |

| AA | Allergic asthma |

| H&E | Hematoxylin and eosin |

| FCM | Flowcytometry |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| qPCR | Quantitative Real-time PCR |

| DEGs | Differently expressed genes |

| AHR | Airway hyperresponsiveness |

| FcRn | Neonatal Fc receptor |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

References

- Conde, E.; Bertrand, R.; Balbino, B.; Bonnefoy, J.; Stackowicz, J.; Caillot, N.; Colaone, F.; Hamdi, S.; Houmadi, R.; Loste, A. Dual vaccination against IL-4 and IL-13 protects against chronic allergic asthma in mice. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Córdova, V.; Berra-Romani, R.; Mendoza, L.K.F.; Reyes-Leyv, J. Th17 Lymphocytes in Children with Asthma: Do They Influence Control? Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. Pulmonol. 2021, 34, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morianos, I.; Semitekolou, M. Dendritic Cells: Critical Regulators of Allergic Asthma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Yamane, H.; Paul, W.E. Differentiation of effector CD4 T cell populations. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 28, 445–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maspero, J.; Adir, Y.; Al-Ahmad, M.; Celis-Preciado, C.A.; Colodenco, F.D.; Giavina-Bianchi, P.; Lababidi, H.; Ledanois, O.; Mahoub, B.; Perng, D.W. Type 2 inflammation in asthma and other airway diseases. Eur. Respir. J. Open Res. 2022, 8, 00576-2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Hu, J.; Xu, W. Distinct spatial and temporal roles for Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells in asthma. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 974066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdis, C.A.; Arkwright, P.D.; Brüggen, M.C. Type 2 immunity in the skin and lungs. Allergy 2020, 75, 1582–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, K.; Ogasawara, M. The Role of Histamine in the Pathophysiology of Asthma and the Clinical Efficacy of Antihistamines in Asthma Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Liu, Q.; Canning, B.J. Evidence for autocrine and paracrine regulation of allergen-induced mast cell mediator release in the guinea pig airways. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 822, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olewicz-Gawlik, A.; Kowala-Piaskowska, A. Self-reactive IgE and anti-IgE therapy in autoimmunediseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1112917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemelka-Wiacek, M.; Agache, I.; Akdis, C.A.; Akdis, M.; Casale, T.B.; Dramburg, S.; Jahnz-Różyk, K.; Kosowska, A.; Matricardi, P.M.; Pfaar, O. Hot topics in allergen immunotherapy, Current status and future perspective. Allergy 2020, 41, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.C.; Ownby, D.R. The infant gut bacterial microbiota and risk of pediatric asthma and allergic diseases. Transl. Res. 2017, 179, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalewicz-Kulbat, M.; Locht, C. BCG for the prevention and treatment of allergic asthma. Vaccine 2021, 39, 7341–7352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, H.; Tang, A.Z.; Xu, M.L.; Chen, H.L.; Wang, F.; Li, C.Q. Mycobacterium vaccae attenuates airway inflammation by inhibiting autophagy and activating PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in OVA-induced allergic airway inflammation mouse model. Mol. Immunol. 2024, 173, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Sun, J. Mechanism of ESAT-6 membrane interaction and its roles in pathogenesis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Toxicon 2016, 116, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zonghai, C.; Tao, L.; Pengjiao, M.; Liang, G.; Rongchuan, Z.; Xinyan, W.; Weny, N.; Wei, L.; Yi, W.; Lang, B. Mycobacterium tuberculosis ESAT6 modulates host innate immunity by downregulating miR-222-3p target PTEN. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2022, 1868, 166292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zeng, Y.; Lin, J.; Liu, H.; Liang, C.L.; Chen, Y.; Qiu, F.; Bromberg, J.S.; Dai, Z. ESAT-6 protein suppresses allograft rejection by inducing CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells through IκBα/cRel pathway. Front. Immunol. 2025, 5, 1529226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safar, H.A.; El-Hashim, A.Z.; Amoudy, H.; Mustafa, A.S. Mycobacteriumtuberculosis-Specific Antigen Rv3619c Effectively Alleviates Allergic Asthma in Mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 532199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyzik, M.; Kozicky, L.K.; Gandhi, A.K.; Blumberg, R.S. The therapeutic age of the neonatal Fc receptor. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 23, 415–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, S.; Zhang, D.; Yang, Z.; Li, R.; Zhang, X.; Gao, F.; Yu, F.L. The role of immunoglobulin transport receptor, neonatal Fc receptor in mucosal infection and immunity and therapeutic intervention. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 138, 112583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Wu, C.; Yang, Y.; Sniderhan, L.F.; Maggirwar, S.B.; Dewhurst, S.; Lu, Y. Lentiviral vector-mediated stable expression of sTNFR-Fc in human macrophage and neuronal cells as a potential therapy for neuro AIDS. J. Neuroinflammation 2011, 8, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancuso, M.E.; Mannucci, P.M. Fc-fusion technology and recombinant FVIII and FIX in the management of the hemophilias. Drug Des. Devel Ther. 2014, 28, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Gao, D.; Zhang, Z. Telitacicept, a novel humanized, recombinant TACI-Fc fusion protein, for the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Drugs Today 2022, 58, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, R.G.; Wu, Y.F.; Lu, H.W.; Weng, D.; Xu, J.Y.; Wang, L.L.; Zhang, L.S.; Zhao, C.Q.; Li, J.X.; Yu, Y. Th2-skewed peripheral T-helper cells drive B-cells in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2024, 63, 2400386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Dong, P.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, W.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, Y.; Mei, C.; Guo, F.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, J.Q. PKCλ/ι regulates Th17 differentiation and house dust mite-induced allergic airway inflammation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2018, 1864, 934941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, O.; Wada, N.A.; Kinoshita, Y.; Hino, H.; Kakefuda, M.; Ito, T.; Fujii, E.; Noguchi, M.; Sato, K.; Morita, M. Entire CD3ε, δ, and γ humanized mouse to evaluate human CD3-mediated therapeutics. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 45839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariuzza, R.A.; Agnihotri, P.; Orban, J. The structural basis of T-cell receptor (TCR) activation: An enduring enigma. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 914–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, R.; Satia, I.; Ojanguren, I. European Respiratory Society guidelines for the diagnosis of asthma in adults. Eur. Respir. J. 2022, 60, 2101585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, N.G.; Miligkos, M.; Xepapadaki, P. A Current Perspective of Allergic Asthma: From Mechanisms to Management. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2022, 268, 69–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffler, E.; Madeira, L.N.G.; Ferrando, M.; Puggioni, F.; Racca, F.; Malvezzi, L.; Passalacqua, G.; Canonica, G.W. Inhaled Corticosteroids Safety and Adverse Effects in Patients with Asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2018, 6, 776–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuberi, F.F.; Haroon, M.A.; Haseeb, A.; Khuhawar, S.M. Role of Montelukast in Asthma and Allergic rhinitis patients. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 36, 1517–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, N.; Mushtaq, F.; Leitner, C.; Ilchyshyn, A.; Smith, G.T.; Cree, I.A. Chronic tarsal conjunc-tivitis. BMC Ophthalmol. 2016, 16, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Chen, S.; Han, Y.; Chen, H.; Wu, J.; Zhang, M. Bcl11b Regulates IL-17 Through the TGF-β/Smad Pathway in HDM-Induced Asthma. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2018, 10, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Chen, X.; Hu, H. CD4+ T-Cell Differentiation In Vitro. Methods Mol. Biol. 2020, 2111, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.; Iijima, K.; Checkel, J.L.; Kita, H. IL-1 family cytokines drive Th2 and Th17 cells to innocuous airborne antigens. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2013, 49, 989998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailis, W.; Shyer, J.A.; Zhao, J.; Canaveras, J.C.G.; Al Khazal, F.J.; Qu, R.; Steach, H.R.; Bielecki, P.; Khan, O.; Jackson, R.; et al. Distinct modes of mitochondrial metabolism uncouple T cell differentiation and function. Nature 2019, 571, 403–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamane, H.; Paul, W.E. Early signaling events that underlie fate decisions of naive CD4(+) T cells toward distinct T-helper cell subsets. Immunol. Rev. 2013, 252, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibbitt, C.A.; Stark, J.M.; Martens, L.; Ma, J.; Mold, J.E.; Deswarte, K.; Oliynyk, G.; Feng, X.; Lambrecht, B.N.; Nylén, S.; et al. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing of the T Helper Cell Response to House Dust Mites Defines a Distinct Gene Expression Signature in Airway Th2 Cells. Immunity 2019, 51, 169–184.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, W.; Lu, C.; Xu, F. The YAP/HIF-1α/miR-182/EGR2 axis is implicated in asthma severity through the control of Th17 cell differentiation. Cell Biosci. 2021, 11, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Chen, G.; Xu, F.; Sun, B.; Chen, X.; Hu, W.; Li, F.; Syeda, M.Z.; Chen, H.; Wu, Y.; et al. Treatment of allergic eosinophilic asthma through engineered IL-5-anchored chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Cell Discov. 2022, 8, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Borght, K.; Brimnes, J.; Haspeslagh, E.; Brand, S.; Neyt, K.; Gupta, S.; Knudsen, N.P.H.; Hammad, H.; Andersen, P.S.; Lambrecht, B.N.; et al. Sublingual allergen immunotherapy prevents house dustmiteinhalanttype2 immunity through dendritic cell mediated induction of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Mucosal Immunol. 2024, 17, 618632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sethi, G.S.; Gracias, D.T.; Gupta, R.K.; Carr, D.; Miki, H.; Da Silva Antunes, R.; Croft, M. Anti-CD3 inhibits circulatory and tissue-resident memory CD4 T cells that drive asthma exacerbations in mice. Allergy 2023, 78, 2168–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellings, P.W.; Steelant, B. Epithelial barriers in allergy and asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 145, 1499–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Yang, Y.; Yang, M.; Wang, J.; Hai, M.; Zhang, W.; Ma, R.; Ma, G.; Wang, N.; Qin, Y.; et al. Mechanisms of Mt.b Ag85B-Fc fusion protein against allergic asthma in mice by intranasal immunization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 283, 137535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, A.; Mazón, A.; Nieto, M.; Calderón, R.; Calaforra, S.; Selva, B.; Uixera, S.; Palao, M.J.; Brandi, P.; Conejero, L.; et al. Bacterial Mucosal Immunotherapy with MV130 Prevents Recurrent Wheezing in Children: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-controlled Clinical Trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 204, 462–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, A.; Velmurugu, Y.; Flores, M.B.; Dibba, F.; Beesam, S.; Kikvadze, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Li, T.; Shin, H.W.; et al. In situ cell-surface conformation of the TCR-CD3 signaling complex. Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ. Rep. 2024, 25, 5719–5742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcillán, B.; Fuentes, P.; Marin, A.V.; Megino, R.F.; Chacon-Arguedas, D.; Mazariegos, M.S.; Jiménez-Reinoso, A.; Muñoz-Ruiz, M.; Laborda, R.G.; Cárdenas, P.P.; et al. CD3G or CD3D Knockdown in Mature, but Not Immature, T Lymphocytes Similarly Cripples the Human TCRαβ Complex. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 608490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, B.E.; Ahn, J.H.; Park, E.K.; Jeong, H.; Lee, H.J.; Jung, Y.J.; Shin, S.J.; Jeong, H.S.; Yoo, J.S.; Shin, E.; et al. B Cell-Based Vaccine Transduced With ESAT6-Expressing Vaccinia Virus and Presenting α-Galactosylceramide Is a Novel Vaccine Candidate Against ESAT6-Expressing Mycobacterial Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpande, C.A.M.; Rozot, V.; Mosito, B.; Musvosvi, M.; Dintwe, O.B.; Bilek, N.; Hatherill, M.; Scriba, T.J.; Nemes, E.; ACS Study Team. Immune profiling of Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific T cells in recent and remote infection. EBioMedicine 2021, 64, 103233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, M.; Dickson, A.J. Reprogramming of Chinese hamster ovary cells towards enhanced proteinsecretion. Metab. Eng. 2022, 69, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böll, S.; Ziemann, S.; Ohl, K.; Klemm, P.; Rieg, A.D.; Gulbins, E.; Becker, K.A.; Kamler, M.; Wagner, N.; Uhlig, S. Acid sphingomyelinase regulates TH 2 cytokine release and bronchial asthma. Allergy 2019, 75, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, T.; Rajendrakumar, A.M.; Acharya, G.; Miao, Z.; Varghese, B.P.; Yu, H.; Dhakal, B.; LeRoith, T.; Karunakaran, A. An FcRn-targeted mucosal vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infection and transmission. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myou, S.; Leff, A.R.; Myo, S.; Boetticher, E.; Tong, J.; Meliton, A.Y.; Liu, J.; Munoz, N.M.; Zhu, X. Blockade of inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness in immune-sensitized mice by dominant-negative phosphoinositide 3-kinase-TAT. J. Exp. Med. 2003, 198, 1573–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, H.; Masuda, T.; Tokuoka, S.; Komai, M.; Nagao, K.; Takahashi, Y.; Nagai, H. The effect of allergen-induced airway inflammation on airway remodeling in a murine model of allergic asthma. Inflamm. Res. 2001, 50, 616–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Hai, M.; Yang, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhang, W.; Ma, R.; Sun, M.; Qin, Y.; Yang, Y.; Dong, Z.; et al. Preparation of ESAT6-Fc Fusion Protein and Its Therapeutic Efficacy and Immune Mechanisms in Allergic Asthma Mice via Intranasal Immunization. Molecules 2026, 31, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010007

Wang J, Hai M, Yang Y, Wang T, Zhang W, Ma R, Sun M, Qin Y, Yang Y, Dong Z, et al. Preparation of ESAT6-Fc Fusion Protein and Its Therapeutic Efficacy and Immune Mechanisms in Allergic Asthma Mice via Intranasal Immunization. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jing, Maiyan Hai, Yuxin Yang, Tiansong Wang, Wei Zhang, Rui Ma, Miao Sun, Yanyan Qin, Yuan Yang, Zihan Dong, and et al. 2026. "Preparation of ESAT6-Fc Fusion Protein and Its Therapeutic Efficacy and Immune Mechanisms in Allergic Asthma Mice via Intranasal Immunization" Molecules 31, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010007

APA StyleWang, J., Hai, M., Yang, Y., Wang, T., Zhang, W., Ma, R., Sun, M., Qin, Y., Yang, Y., Dong, Z., Yang, M., & Wan, Q. (2026). Preparation of ESAT6-Fc Fusion Protein and Its Therapeutic Efficacy and Immune Mechanisms in Allergic Asthma Mice via Intranasal Immunization. Molecules, 31(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010007