Energy-Dependent Effects of Pulsed Electric Field (PEF) Treatment on the Quality Attributes, Bioactive Compounds, and Microstructure of Red Bell Pepper

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Effect of PEF Treatment on the Physical Integrity of the Red Bell Pepper

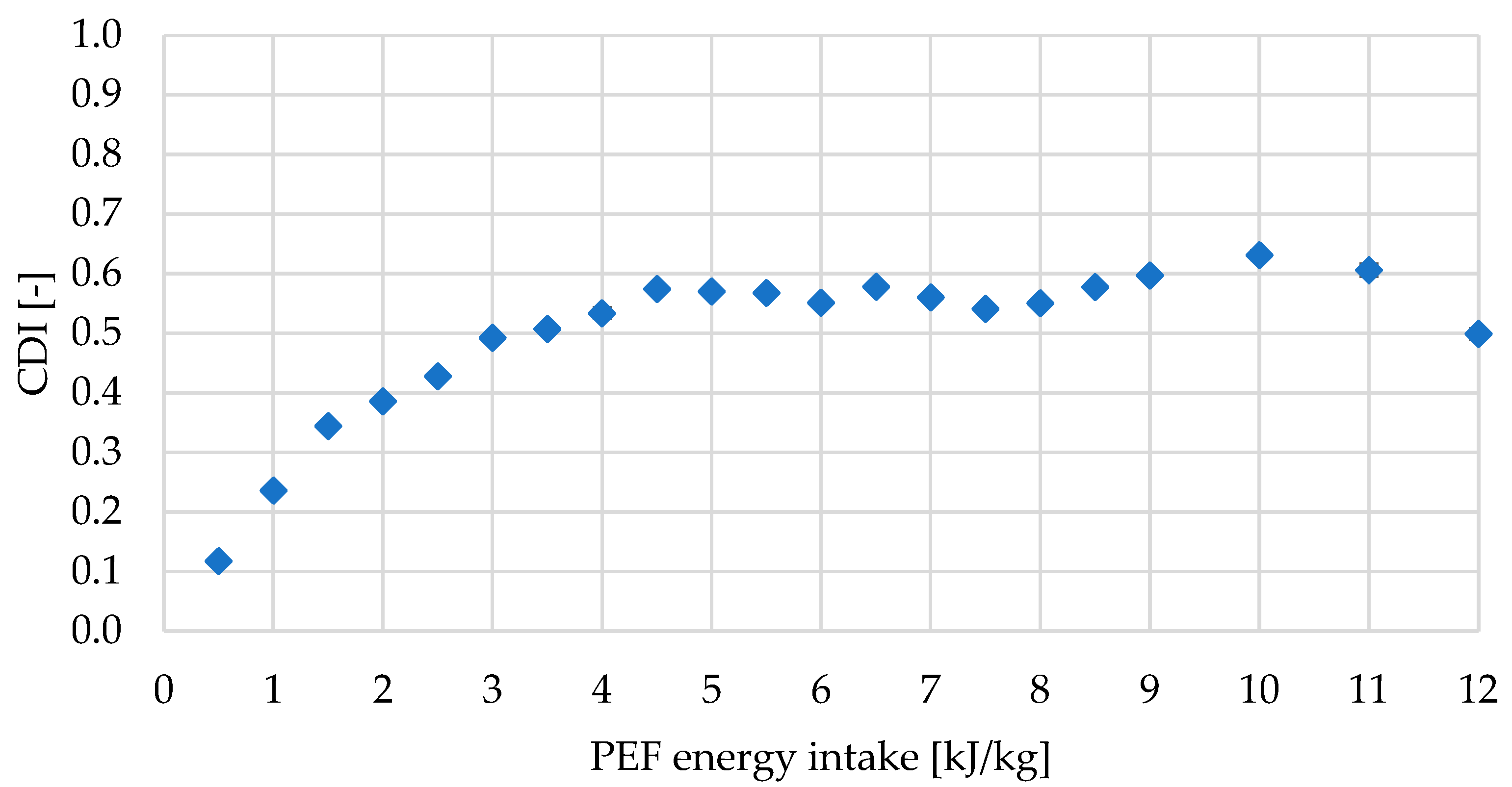

2.1.1. Cell Disintegration Index (CDI) of Red Bell Pepper Treated with PEF

2.1.2. Color of Red Bell Pepper Treated with PEF

2.1.3. Texture of Red Bell Pepper Treated with PEF

2.1.4. Structure of Red Bell Pepper Treated with PEF

2.2. Effect of PEF Treatment on the Chemical Properties of the Red Bell Pepper

2.2.1. Total Polyphenols Content (TPC), Total Flavonoids Content (TFC), Vitamin C (DHA + AsA) Content, and Total Carotenoid Content (TCC) of Red Bell Pepper Treated with PEF

2.2.2. Antioxidant Activity (ABTS, DPPH, FRAP) of Red Bell Pepper Treated with PEF

2.2.3. Sugar Composition of Red Bell Pepper Treated with PEF

2.2.4. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) of Red Bell Pepper Treated with PEF

2.2.5. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) of Red Bell Pepper Treated with PEF

2.2.6. Time Domain Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (TD-NMR) of Red Bell Pepper Treated with PEF

2.3. Effect of PEF Treatment on Microbial Stability of the Red Bell Pepper

2.4. Effect of PEF Treatment on Red Bell Pepper Tissue

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Sample Preparation (PEF Treatment)

3.3. Physico-Chemical Characterization

3.3.1. Color

3.3.2. Texture

3.3.3. Bioactive Compounds (Total Polyphenols Content, Total Flavonoids Content, Vitamin C (DHA + AsA) Content, Total Carotenoids Content) and Antioxidant Activity

Extraction for Total Phenolics, Flavonoids, and Antioxidant Assays (ABTS, DPPH, FRAP)

Total Polyphenols Content (TPC)

Total Flavonoids Content (TFC)

Vitamin C (DHA + AsA) Content

Total Carotenoid Content (TCC)

Antioxidant Activity (ABTS, DPPH, FRAP)

3.3.4. Sugar Composition

3.4. Microbiological Analysis

3.5. Structural and Molecular Analysis

3.5.1. Structural Analysis (SEM, Micro-CT)

3.5.2. Time Domain Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (TD-NMR)

3.5.3. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

3.5.4. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

3.6. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martínez-Girón, J. Ultrasound-assisted production of sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum) oleoresin and tree tomato (Solanum betaceum Cav.) juice: A potential source of bioactive compounds in margarine. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2024, 14, 10443–10457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nian, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Cao, Y. Influence of ultrasonic pretreatment on the quality attributes and pectin structure of chili peppers (Capsicum spp.). Ultrason. Sonochem. 2024, 110, 107041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiamiyu, Q.O.; Adebayo, S.E.; Ibrahim, N. Recent advances on postharvest technologies of bell pepper: A review. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rybak, K.; Wiktor, A.; Witrowa-Rajchert, D.; Parniakov, O.; Nowacka, M. The Effect of Traditional and Non-Thermal Treatments on the Bioactive Compounds and Sugars Content of Red Bell Pepper. Molecules 2020, 25, 4287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybak, K.; Wiktor, A.; Kaveh, M.; Dadan, M.; Witrowa-Rajchert, D.; Nowacka, M. Effect of Thermal and Non-Thermal Technologies on Kinetics and the Main Quality Parameters of Red Bell Pepper Dried with Convective and Microwave–Convective Methods. Molecules 2022, 27, 2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, E.M.C.; Brandão, T.R.S.; Silva, C.L.M. Impact of non-thermal technologies and sanitizer solutions on microbial load reduction and quality factor retention of frozen red bell peppers. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2013, 17, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikmetas, D.N.; Zargarchi, S.; Scharf, S.; Gökoglu, B.Z.-; Capanoglu, E.; Karbancioglu-Güler, F.; Gök, R.; Esatbeyoglu, T. Low pressure cold plasma treatment for microbial decontamination, improvement of bioaccessibility and aroma profile of dried red peppers. Food Chem. 2025, 495, 146424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punthi, F.; Yudhistira, B.; Gavahian, M.; Chang, C.; Cheng, K.; Hou, C.; Hsieh, C. Pulsed electric field-assisted drying: A review of its underlying mechanisms, applications, and role in fresh produce plant-based food preservation. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 5109–5130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llavata, B.; Clemente, G.; Bon, J.; Cárcel, J.A. Pulsed electric field (PEF) pretreatment impact on the freezing and ultrasound-assisted atmospheric freeze-drying of butternut squash and yellow turnip. J. Food Eng. 2025, 395, 112543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tylewicz, U. How does pulsed electric field work? In Pulsed Electric Fields to Obtain Healthier and Sustainable Food for Tomorrow; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Thirumdas, R.; Sarangapani, C.; Barba, F.J. Pulsed electric field applications for the extraction of compounds and fractions (fruit juices, winery, oils, by-products, etc.). In Pulsed Electric Fields to Obtain Healthier and Sustainable Food for Tomorrow; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 227–246. [Google Scholar]

- Matys, A.; Witrowa-Rajchert, D.; Parniakov, O.; Wiktor, A. Assessment of the effect of air humidity and temperature on convective drying of apple with pulsed electric field pretreatment. LWT 2023, 188, 115455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjha, M.M.A.N.; Kanwal, R.; Shafique, B.; Arshad, R.N.; Irfan, S.; Kieliszek, M.; Kowalczewski, P.Ł.; Irfan, M.; Khalid, M.Z.; Roobab, U.; et al. A Critical Review on Pulsed Electric Field: A Novel Technology for the Extraction of Phytoconstituents. Molecules 2021, 26, 4893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauster, T.; Giancaterino, M.; Pittia, P.; Jaeger, H. Effect of pulsed electric field pretreatment on shrinkage, rehydration capacity and texture of freeze-dried plant materials. LWT 2020, 121, 108937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi Sani, I.; Mehrnoosh, F.; Rasul, N.H.; Hassani, B.; Mohammadi, H.; Gholizadeh, H.; Sattari, N.; Kaveh, M.; Khodaei, S.M.; Alizadeh Sani, M.; et al. Pulsed electric field-assisted extraction of natural colorants; principles and applications. Food Biosci. 2024, 61, 104746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, Y.-C.; Min, S.C.; Lee, D.-U. Accelerated Drying and Improved Color Properties of Red Pepper by Pretreatment of Pulsed Electric Fields. Dry. Technol. 2015, 33, 926–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ade-Omowaye, B.I.O.; Taiwo, K.; Eshtiaghi, N.M.; Angersbach, A.; Knorr, D. Comparative evaluation of the effects of pulsed electric field and freezing on cell membrane permeabilisation and mass transfer during dehydration of red bell peppers. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2003, 4, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaf, N.; Siclari, C.; Dhenge, R.; Ganino, T.; Chiavaro, E.; Rinaldi, M. Application of pulsed electric field to promote peelability on peponids and drupes: Understanding the effects on cells and the physical properties of fruits. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2025, 104, 104111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashvand, M.; Kazemi, A.; Nikzadfar, M.; Javed, T.; Luke, L.P.; Kjær, K.M.; Feyissa, A.H.; Millman, C.; Zhang, H. The Potential of Pulsed Electric Field in the Postharvest Process of Fruit and Vegetables: A Comprehensive Perspective. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2025, 18, 5117–5145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Liao, L.; Zeng, X.-A.; Manzoor, M.F.; Mazahir, M. Impact of sustainable emerging pulsed electric field processing on textural properties of food products and their mechanisms: An updated review. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 15, 101076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yang, H.; Fang, W.; Huang, X.; Shi, J.; Zou, X. Effects of Variety and Pulsed Electric Field on the Quality of Fresh-Cut Apples. Agriculture 2023, 13, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Oey, I.; Leong, S.Y.; Kam, R.; Kantono, K.; Hamid, N. Pulsed Electric Field Pretreatments Affect the Metabolite Profile and Antioxidant Activities of Freeze− and Air−Dried New Zealand Apricots. Foods 2024, 13, 1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puértolas, E.; Luengo, E.; Álvarez, I.; Raso, J. Improving Mass Transfer to Soften Tissues by Pulsed Electric Fields: Fundamentals and Applications. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 3, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoshal, G. Comprehensive review on pulsed electric field in food preservation: Gaps in current studies for potential future research. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iranshahi, K.; Psarianos, M.; Rubinetti, D.; Onwude, D.I.; Schlüter, O.K.; Defraeye, T. Impact of pre-treatment methods on the drying kinetics, product quality, and energy consumption of electrohydrodynamic drying of biological materials. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2023, 85, 103338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lung, C.-T.; Chang, C.-K.; Cheng, F.-C.; Hou, C.-Y.; Chen, M.-H.; Santoso, S.P.; Yudhistira, B.; Hsieh, C.-W. Effects of pulsed electric field-assisted thawing on the characteristics and quality of Pekin duck meat. Food Chem. 2022, 390, 133137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.N.; Jaeschke, D.P.; Rech, R.; Mercali, G.D.; Marczak, L.D.F.; Pueyo, J.R. Pulsed electric field-assisted extraction of carotenoids from Chlorella zofingiensis. Algal Res. 2024, 79, 103472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Lyu, X.; Arshad, R.N.; Aadil, R.M.; Tong, Y.; Zhao, W.; Yang, R. Pulsed electric field as a promising technology for solid foods processing: A review. Food Chem. 2023, 403, 134367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribas-Agustí, A.; Martín-Belloso, O.; Soliva-Fortuny, R.; Elez-Martínez, P. Enhancing hydroxycinnamic acids and flavan-3-ol contents by pulsed electric fields without affecting quality attributes of apple. Food Res. Int. 2019, 121, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schefer, S.; Oest, M.; Rohn, S. Interactions between Phenolic Acids, Proteins, and Carbohydrates—Influence on Dough and Bread Properties. Foods 2021, 10, 2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemli, E.; Ozkan, G.; Gultekin Subasi, B.; Cavdar, H.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Zhao, C.; Capanoglu, E. Interactions between proteins and phenolics: Effects of food processing on the content and digestibility of phenolic compounds. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, 104, 2535–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renard, C.M.G.C.; Watrelot, A.A.; Le Bourvellec, C. Interactions between polyphenols and polysaccharides: Mechanisms and consequences in food processing and digestion. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 60, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei-Baktash, H.; Hamdami, N.; Torabi, P.; Fallah-Joshaqani, S.; Dalvi-Isfahan, M. Impact of different pretreatments on drying kinetics and quality of button mushroom slices dried by hot-air or electrohydrodynamic drying. LWT 2022, 155, 112894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltacioglu, C.; Yetisen, M.; Baltacioglu, H.; Karacabey, E.; Buzrul, S. Pulsed Electric Fields (PEF) Treatment Prior to Hot-Air and Microwave Drying of Yellow- and Purple-Fleshed Potatoes. Potato Res. 2024, 68, 1171–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutte, M.; Hayward, S.; Manley, M. Nonenzymatic Browning and Antioxidant Properties of Thermally Treated Cereal Grains and End Products. J. Food Biochem. 2024, 2024, 3865849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpentieri, S.; Ferrari, G.; Pataro, G. Pulsed electric fields-assisted extraction of valuable compounds from red grape pomace: Process optimization using response surface methodology. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1158019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enjie, C.; Jiankai, Z.; Hao, W.; Haobin, Z.; Jiayi, S.; Di, Z.; Siming, Z. The Effect of Pulsed Electric Field Pretreatment on the Quality and Antioxidant Activity of Dried Bird’s Eye Chili (Capsicum frutescens L.). J. Food Process Eng. 2025, 48, e70143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, L.; Giancaterino, M.; Rocchi, R.; Tylewicz, U.; Valbonetti, L.; Faieta, M.; Pittia, P. Pulsed electric fields (PEF) as hot air drying pre-treatment: Effect on quality and functional properties of saffron (Crocus sativus L.). Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2021, 67, 102592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-W.; Zeng, X.-A.; Ngadi, M. Enhanced extraction of phenolic compounds from onion by pulsed electric field (PEF). J. Food Process. Preserv. 2018, 42, e13755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahn, A.; Comett, R.; Segura-Ponce, L.A.; Díaz-Álvarez, R.E. Effect of pulsed electric field-assisted extraction on recovery of sulforaphane from broccoli florets. J. Food Process Eng. 2022, 45, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronbauer, M.; Shorstkii, I.; Botelho da Silva, S.; Toepfl, S.; Lammerskitten, A.; Siemer, C. Pulsed electric field assisted extraction of soluble proteins from nettle leaves (Urtica dioica L.): Kinetics and optimization using temperature and specific energy. Sustain. Food Technol. 2023, 1, 886–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerit, İ.; Pabuçcu, D.; Sezgin, M.; Bulut, B.; Demirkol, O. Effects of cooking on glutathione, cysteine, beta-carotene, ascorbic acid concentrations and antioxidant activity of red bell peppers (Capsicum annum L.). Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2025, 39, 101092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumpf, J.; Burger, R.; Schulze, M. Statistical evaluation of DPPH, ABTS, FRAP, and Folin-Ciocalteu assays to assess the antioxidant capacity of lignins. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 233, 123470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigore-Gurgu, L.; Dumitrașcu, L.; Aprodu, I. Aromatic Herbs as a Source of Bioactive Compounds: An Overview of Their Antioxidant Capacity, Antimicrobial Activity, and Major Applications. Molecules 2025, 30, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wołosiak, R.; Drużyńska, B.; Derewiaka, D.; Piecyk, M.; Majewska, E.; Ciecierska, M.; Worobiej, E.; Pakosz, P. Verification of the Conditions for Determination of Antioxidant Activity by ABTS and DPPH Assays—A Practical Approach. Molecules 2021, 27, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.-H.; Kim, M.-H.; Han, Y.-S. Physicochemical properties and antioxidant activity of colored peppers (Capsicum annuum L.). Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2023, 32, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segovia, F.J.; Luengo, E.; Corral-Pérez, J.J.; Raso, J.; Almajano, M.P. Improvements in the aqueous extraction of polyphenols from borage (Borago officinalis L.) leaves by pulsed electric fields: Pulsed electric fields (PEF) applications. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 65, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Feng, Z.; Aila, R.; Hou, Y.; Carne, A.; Bekhit, A.E.-D.A. Effect of pulsed electric fields (PEF) on physico-chemical properties, β-carotene and antioxidant activity of air-dried apricots. Food Chem. 2019, 291, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quitão-Teixeira, L.J.; Odriozola-Serrano, I.; Soliva-Fortuny, R.; Mota-Ramos, A.; Martín-Belloso, O. Comparative study on antioxidant properties of carrot juice stabilised by high-intensity pulsed electric fields or heat treatments. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2009, 89, 2636–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarżyńska, A.; Gondek, E.; Nowacka, M.; Wiktor, A. Pulsed Electric Fields as an Infrared–Convective Drying Pretreatment: Effect on Drying Course, Color, and Chemical Properties of Apple Tissue. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Wang, Z.; Sun, G.; Zhao, Y.; Tang, S. Pulsed Electric Field (PEF) Technology for Preserving Fruits and Vegetables: Applications, Benefits, and Comparisons. Food Rev. Int. 2025, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti, R.N.; Balthazar, C.F.; Margalho, L.P.; Freitas, M.Q.; Sant’Ana, A.S.; Cruz, A.G. Pulsed electric field-based technology for microbial inactivation in milk and dairy products. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2023, 54, 101087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Renard, C.M.G.C.; Bureau, S.; Le Bourvellec, C. Revisiting the contribution of ATR-FTIR spectroscopy to characterize plant cell wall polysaccharides. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 262, 117935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.; Yin, J.-Y.; Nie, S.-P.; Xie, M.-Y. Applications of infrared spectroscopy in polysaccharide structural analysis: Progress, challenge and perspective. Food Chem. X 2021, 12, 100168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.; Wang, L.; Cao, H.; Du, R.; Yang, S.; Yan, Y.; Zheng, B. Characterization of the Structure and Physicochemical Properties of Soluble Dietary Fiber from Peanut Shells Prepared by Pulsed. Molecules 2024, 29, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grgić, T.; Bleha, R.; Smrčkova, P.; Stulić, V.; Pavičić, T.V.; Synytsya, A.; Iveković, D.; Novotni, D. Pulsed Electric Field Treatment of Oat and Barley Flour: Influence on Enzymes, Non-starch Polysaccharides, Dough Rheological Properties, and Application in Flat Bread. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2024, 17, 4303–4324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, A.; Pozo, M.; Sánchez-Moreno, V.E.; Vera, E.; Jaramillo, L.I. Pulsed Electric Field-Assisted Extraction of Inulin from Ecuadorian Cabuya (Agave americana). Molecules 2024, 29, 3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faridnia, F.; Burritt, D.J.; Bremer, P.J.; Oey, I. Innovative approach to determine the effect of pulsed electric fields on the microstructure of whole potato tubers: Use of cell viability, microscopic images and ionic leakage measurements. Food Res. Int. 2015, 77, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parniakov, O.; Barba, F.J.; Grimi, N.; Lebovka, N.; Vorobiev, E. Extraction assisted by pulsed electric energy as a potential tool for green and sustainable recovery of nutritionally valuable compounds from mango peels. Food Chem. 2016, 192, 842–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellarosa, N.; Frontuto, D.; Laghi, L.; Dalla Rosa, M.; Lyng, J.G. The impact of pulsed electric fields and ultrasound on water distribution and loss in mushrooms stalks. Food Chem. 2017, 236, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellarosa, N.; Ragni, L.; Laghi, L.; Tylewicz, U.; Rocculi, P.; Dalla Rosa, M. Time domain nuclear magnetic resonance to monitor mass transfer mechanisms in apple tissue promoted by osmotic dehydration combined with pulsed electric fields. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2016, 37, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tylewicz, U.; Aganovic, K.; Vannini, M.; Toepfl, S.; Bortolotti, V.; Dalla Rosa, M.; Oey, I.; Heinz, V. Effect of pulsed electric field treatment on water distribution of freeze-dried apple tissue evaluated with DSC and TD-NMR techniques. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2016, 37, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersus, S.; Oztop, M.H.; McCarthy, M.J.; Barrett, D.M. Disintegration Efficiency of Pulsed Electric Field Induced Effects on Onion (Allium cepa L.) Tissues as a Function of Pulse Protocol and Determination of Cell Integrity by 1 H-NMR Relaxometry. J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, E444–E452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, A.; Mishra, A.K.; Kumari, A.; Farooq, M.A.; Alee, M.; Khalifa, I.; Siddeeg, A.; Zeng, X.; Singh, N. Impact of pulsed electric fields on membrane disintegration, drying, and osmotic dehydration of foods. J. Food Process Eng. 2024, 47, e14552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkanan, Z.T.; Altemimi, A.B.; Younis, M.I.; Ali, M.R.; Cacciola, F.; Abedelmaksoud, T.G. Trends, Recent Advances, and Application of Pulsed Electric Field in Food Processing: A Review. ChemBioEng Rev. 2024, 11, e202300078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorstkii, I.; Stuehmeier-Niehe, C.; Sosnin, M.; Mounassar, E.H.A.; Comiotto-Alles, M.; Siemer, C.; Toepfl, S. Pulsed Electric Field Treatment Application to Improve Product Yield and Efficiency of Bioactive Compounds through Extraction from Peels in Kiwifruit Processing. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2023, 2023, 8172255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebovka, N.I.; Shynkaryk, N.V.; Vorobiev, E. Pulsed electric field enhanced drying of potato tissue. J. Food Eng. 2007, 78, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.S.N.; Ali, M.; Lee, W.-H.; Cho, S.-I.; Chung, S.-O. Physicochemical Quality Changes in Tomatoes during Delayed Cooling and Storage in a Controlled Chamber. Agriculture 2020, 10, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; O’Mahony, J.A.; O’Sullivan, M.G.; Kerry, J.P. Comparative Analysis of Composition, Texture, and Sensory Attributes of Commercial Forms of Plant-Based Cheese Analogue Products Available on the Irish Market. Foods 2025, 14, 2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.-Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, M.-Y.; Ge, Y.-Y.; Geng, F.; He, X.-Q.; Xia, Y.; Guo, B.-L.; Gan, R.-Y. Antioxidant capacity, phytochemical profiles, and phenolic metabolomics of selected edible seeds and their sprouts. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1067597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma-Salgado, S.; Vargas, L.; Rababah, T.M.; Feng, H. Impact of Tissue Decay on Drying Kinetics, Moisture Diffusivity, and Microstructure of Bell Pepper and Strawberry. Foods 2025, 14, 3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, J.B.; Mani, J.S.; Naiker, M. Microplate Methods for Measuring Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Capacity in Chickpea: Impact of Shaking. In Proceedings of the CSAC 2023; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 2023; p. 57. [Google Scholar]

- Küpcü, I.H.; Tokatlı, K. Extraction and characterization of phenolic compounds of jujube (Ziziphus jujuba) by innovative techniques. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spínola, V.; Mendes, B.; Câmara, J.S.; Castilho, P.C. An improved and fast UHPLC-PDA methodology for determination of L-ascorbic and dehydroascorbic acids in fruits and vegetables. Evaluation of degradation rate during storage. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2012, 403, 1049–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiszewska-Turak, E.; Sitkiewicz, I.; Janowicz, M. Influence of Ultrasound on the Rheological Properties, Color, Carotenoid Content, and Other Physical Characteristics of Carrot Puree. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Česonienė, L.; Labokas, J.; Jasutienė, I.; Šarkinas, A.; Kaškonienė, V.; Kaškonas, P.; Kazernavičiūtė, R.; Pažereckaitė, A.; Daubaras, R. Bioactive Compounds, Antioxidant, and Antibacterial Properties of Lonicera caerulea Berries: Evaluation of 11 Cultivars. Plants 2021, 10, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo-Rodrigues, H.; Santos, D.; Campos, D.A.; Guerreiro, S.; Ratinho, M.; Rodrigues, I.M.; Pintado, M.E. Impact of Processing Approach and Storage Time on Bioactive and Biological Properties of Rocket, Spinach and Watercress Byproducts. Foods 2021, 10, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solaberrieta, I.; Mellinas, C.; Jiménez, A.; Garrigós, M.C. Recovery of Antioxidants from Tomato Seed Industrial Wastes by Microwave-Assisted and Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction. Foods 2022, 11, 3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartas, J.; Alvarenga, N.; Partidário, A.; Lageiro, M.; Roseiro, C.; Gonçalves, H.; Leitão, A.E.; Ribeiro, C.M.; Dias, J. Influence of geographical origin in the physical and bioactive parameters of single origin dark chocolate. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2024, 250, 2569–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harratt, A.; Wu, W.; Strube, P.; Ceravolo, J.; Beattie, D.; Pukala, T.; Krasowska, M.; Blencowe, A. Comparison of Preservatives for the Prevention of Microbial Spoilage of Apple Pomace During Storage. Foods 2025, 14, 2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacak-Pietrzak, G.; Marzec, A.; Onisk, K.; Kalisz, S.; Dołomisiewicz, W.; Nowak, R.; Krajewska, A.; Dziki, D. Physicochemical Properties and Quality of Bread Enriched with Haskap Berry (Lonicera caerulea L.) Pomace. Molecules 2025, 30, 3884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tappi, S.; Velickova, E.; Mannozzi, C.; Tylewicz, U.; Laghi, L.; Rocculi, P. Multi-Analytical Approach to Study Fresh-Cut Apples Vacuum Impregnated with Different Solutions. Foods 2022, 11, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinas, I.C.; Oprea, E.; Geana, E.-I.; Tutunaru, O.; Pircalabioru, G.G.; Zgura, I.; Chifiriuc, M.C. Valorization of Gleditsia triacanthos Invasive Plant Cellulose Microfibers and Phenolic Compounds for Obtaining Multi-Functional Wound Dressings with Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Properties. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 22, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierzbicka, A.; Janiszewska-Turak, E. Influence of the Salt Addition during the Fermentation Process on the Physical and Chemical Properties of Dried Yellow Beetroot. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Code | Total Color Difference ΔE [-] | Hardness [N] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| External Tissue (Peel) | Internal Tissue | ||

| F | - | - | 52.3 ± 4.52 a * |

| PEF1 | 3.25 ± 1.25 c | 14.8 ± 1.69 a | 41.6 ± 3.57 b |

| PEF2 | 6.59 ± 1.76 b | 10.0 ± 1.52 cd | 43.3 ± 3.75 b |

| PEF4 | 5.38 ± 0.97 bc | 10.8 ± 1.38 bc | 38.3 ± 2.89 b |

| PEF5 | 4.24 ± 1.17 bc | 13.7 ± 0.93 ab | 39.2 ± 4.25 b |

| PEF10 | 15.6 ± 1.84 a | 7.6 ± 2.79 d | 38.9 ± 3.98 b |

| Sample Code | TPC [mg Chlorogenic Acid/100 g d.m.] | TFC [mg QE/100 g d.m.] | Vitamin C [mg/100 g d.m.] | TCC [mg β-Carotene/100 g d.m.] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | 4152 ± 210 a * | 452 ± 28 a | 2099 ± 85 ab | 1264 ± 38 c |

| PEF1 | 3933 ± 93 ab | 360 ± 17 b | 2325 ± 158 a | 1310 ± 50 bc |

| PEF2 | 3906 ± 104 ab | 326 ± 7 bcd | 2130 ± 150 ab | 1325 ± 76 abc |

| PEF4 | 3698 ± 176 b | 292 ± 6 d | 2009 ± 60 b | 1456 ± 53 a |

| PEF5 | 3729 ± 61 b | 352 ± 12 bc | 2173 ± 90 ab | 1413 ± 31 ab |

| PEF10 | 3617 ± 37 b | 318 ± 4 cd | 2232 ± 57 ab | 1209 ± 37 c |

| Sample Code | ABTS [mg TE/g d.m.] | DPPH [mg TE/g d.m.] | FRAP [mg TE/g d.m.] |

|---|---|---|---|

| F | 17.1 ± 0.66 a * | 29.4 ± 0.86 a | 43.0 ± 1.52 a |

| PEF1 | 14.3 ± 0.53 a | 20.2 ± 1.32 b | 28.0 ± 0.48 cd |

| PEF2 | 15.6 ± 0.46 ab | 21.8 ± 0.64 b | 30.4 ± 1.34 bc |

| PEF4 | 17.1 ± 0.74 c | 19.3 ± 1.23 b | 31.6 ± 1.10 b |

| PEF5 | 17.7 ± 0.94 ab | 20.5 ± 0.28 b | 31.4 ± 0.74 b |

| PEF10 | 17.6 ± 0.73 bc | 20.9 ± 1.67 b | 25.1 ± 0.76 d |

| Sample Code | Sucrose [g/100 g d.m.] | Glucose [g/100 g d.m.] | Fructose [g/100 g d.m.] |

|---|---|---|---|

| F | 0.73 ± 0.15 b * | 24.6± 1.22 bc | 35.3 ± 0.73 a |

| PEF1 | 1.08 ± 0.10 a | 26.5 ± 1.05 ab | 32.8 ± 2.74 a |

| PEF2 | 1.18 ± 0.05 a | 27.3 ± 0.26 a | 36.1 ± 0.76 a |

| PEF4 | 0.54 ± 0.09 b | 24.4 ± 1.40 bc | 33.7 ± 0.80 a |

| PEF5 | 0.53 ± 0.05 b | 23.2 ± 0.57 c | 27.9 ± 1.27 b |

| PEF10 | 0.27 ± 0.03 c | 24.7 ± 0.19 bc | 26.5 ± 2.50 b |

| Sample Code | Step 1 (30–110 °C) | Step 2 (110–250 °C) | Step 3 (250–480 °C) | Step 4 (480–600 °C) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mass Loss [%] | Decomposition Temperature [°C] | Mass Loss [%] | Decomposition Temperature [°C] | Mass Loss [%] | Decomposition Temperature [°C] | Mass Loss [%] | Decomposition Temperature [°C] | |

| F | 4.4 | 77 | 32.1 | 181 | 29.4 | 310 | 2.3 | - * |

| PEF1 | 4.8 | 63 | 34.5 | 183 | 30.7 | 311 | 2.5 | - |

| PEF2 | 4.8 | 64 | 34.4 | 182 | 29.4 | 310 | 2.4 | - |

| PEF4 | 4.4 | 67 | 34.4 | 183 | 29.0 | 311 | 2.4 | - |

| PEF5 | 3.9 | 68 | 35.1 | 184 | 29.3 | 311 | 2.5 | - |

| PEF10 | 4.1 | 68 | 34.5 | 183 | 29.0 | 311 | 2.5 | - |

| Sample Code | Description | Specific Energy Input [kJ/kg] |

|---|---|---|

| F | Fresh, untreated sample (control) | 0 |

| PEF1 * | Pulsed Electric Field treated | 1 |

| PEF2 | Pulsed Electric Field treated | 2 |

| PEF4 | Pulsed Electric Field treated | 4 |

| PEF5 | Pulsed Electric Field treated | 5 |

| PEF10 | Pulsed Electric Field treated | 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rybak, K.; Skarżyńska, A.; Ossowski, S.; Dadan, M.; Pobiega, K.; Nowacka, M. Energy-Dependent Effects of Pulsed Electric Field (PEF) Treatment on the Quality Attributes, Bioactive Compounds, and Microstructure of Red Bell Pepper. Molecules 2026, 31, 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010088

Rybak K, Skarżyńska A, Ossowski S, Dadan M, Pobiega K, Nowacka M. Energy-Dependent Effects of Pulsed Electric Field (PEF) Treatment on the Quality Attributes, Bioactive Compounds, and Microstructure of Red Bell Pepper. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):88. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010088

Chicago/Turabian StyleRybak, Katarzyna, Aleksandra Skarżyńska, Szymon Ossowski, Magdalena Dadan, Katarzyna Pobiega, and Małgorzata Nowacka. 2026. "Energy-Dependent Effects of Pulsed Electric Field (PEF) Treatment on the Quality Attributes, Bioactive Compounds, and Microstructure of Red Bell Pepper" Molecules 31, no. 1: 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010088

APA StyleRybak, K., Skarżyńska, A., Ossowski, S., Dadan, M., Pobiega, K., & Nowacka, M. (2026). Energy-Dependent Effects of Pulsed Electric Field (PEF) Treatment on the Quality Attributes, Bioactive Compounds, and Microstructure of Red Bell Pepper. Molecules, 31(1), 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010088