The Evaluation of Eutectic Solvents as Catalysts for Mediating the Greener Synthesis of Poly(alkylene 2,5-furandicarboxylate)s

Abstract

1. Introduction

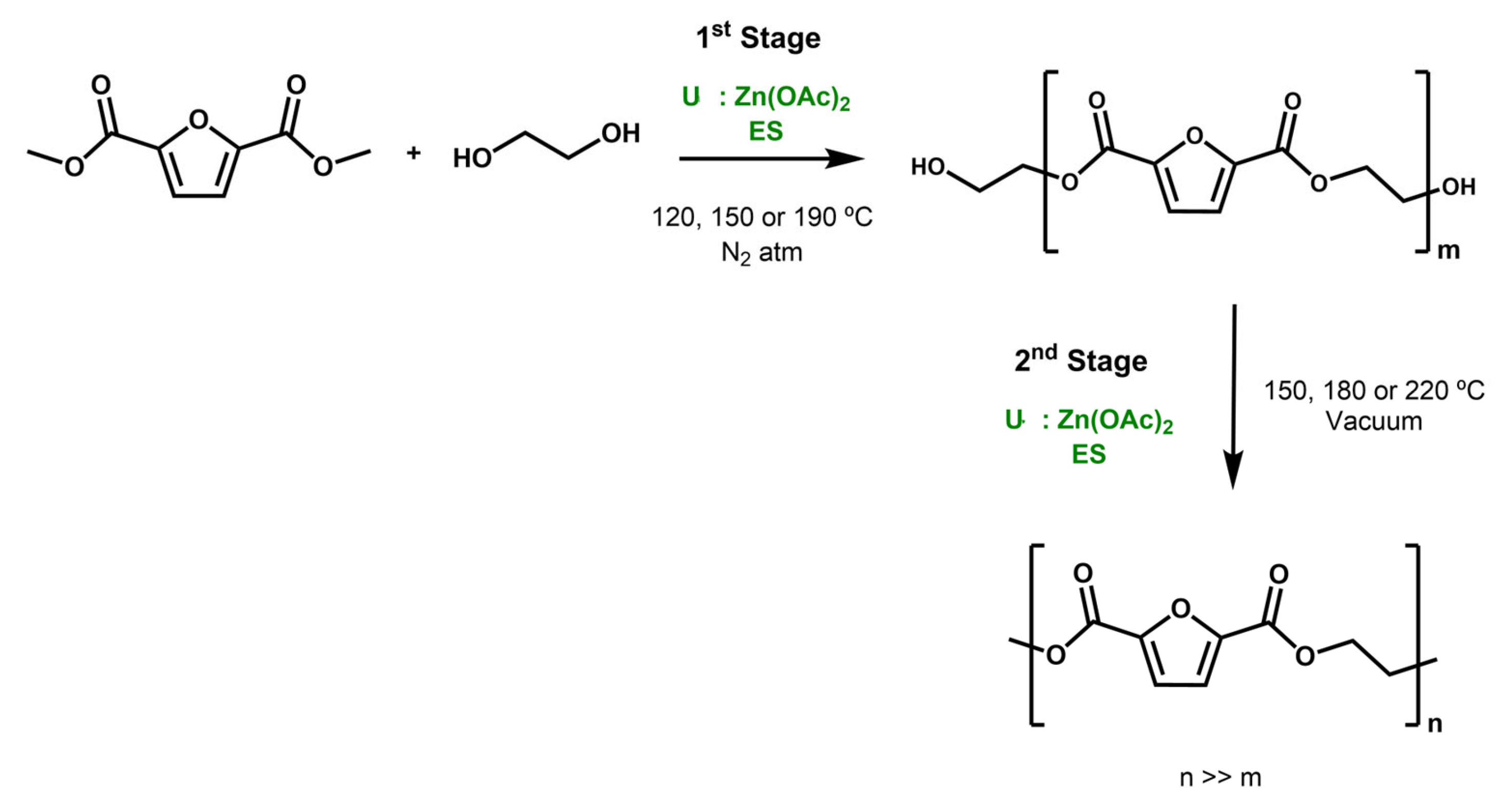

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Eutectic Solvent Preparation

3.3. Polymer Synthesis Procedure

3.4. Polymer Synthesis Optimisation

3.5. Polymer Characterisation

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Plastics Europe. Plastics Europe Plastics—The Fast Facts 2024; Plastics Europe: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, A.F.; Vilela, C.; Fonseca, A.C.; Matos, M.; Freire, C.S.R.; Gruter, G.J.M.; Coelho, J.F.J.; Silvestre, A.J.D. Biobased Polyesters and Other Polymers from 2,5-Furandicarboxylic Acid: A Tribute to Furan Excellency. Polym. Chem. 2015, 6, 5961–5983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loos, K.; Zhang, R.; Pereira, I.; Agostinho, B.; Hu, H.; Maniar, D.; Sbirrazzuoli, N.; Silvestre, A.J.D.D.; Guigo, N.; Sousa, A.F. A Perspective on PEF Synthesis, Properties, and End-Life. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, A.F.; Patrício, R.; Terzopoulou, Z.; Bikiaris, D.N.; Stern, T.; Wenger, J.; Loos, K.; Lotti, N.; Siracusa, V.; Szymczyk, A.; et al. Recommendations for Replacing PET on Packaging, Fiber, and Film Materials with Biobased Counterparts. Green Chem. 2021, 23, 8795–8820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidotti, G.; Soccio, M.; García-Gutiérrez, M.C.; Ezquerra, T.; Siracusa, V.; Gutiérrez-Fernández, E.; Munari, A.; Lotti, N. Fully Biobased Superpolymers of 2,5-Furandicarboxylic Acid with Different Functional Properties: From Rigid to Flexible, High Performant Packaging Materials. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 9558–9568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avantium YXY® Technology. Available online: https://www.avantium.com/technologies/yxy/ (accessed on 8 January 2024).

- Avantium Avantium and Carlsberg Sign Offtake Agreement on PEF. Available online: https://newsroom.avantium.com/avantium-and-carlsberg-sign-offtake-agreement-on-pef/ (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Jiang, M.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Ye, C.; Zhou, G. A Series of Furan-Aromatic Polyesters Synthesized via Direct Esterification Method Based on Renewable Resources. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2012, 50, 1026–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandini, A.; Silvestre, A.J.D.; Neto, C.P.; Sousa, A.F.; Gomes, M. The Furan Counterpart of Poly(Ethylene Terephthalate): An Alternative Material Based on Renewable Resources. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2009, 47, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PubChem Antimony Trioxide. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Antimony-trioxide (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Wu, J.; Xie, H.; Wu, L.; Li, B.G.; Dubois, P. DBU-Catalyzed Biobased Poly(Ethylene 2,5-Furandicarboxylate) Polyester with Rapid Melt Crystallization: Synthesis, Crystallization Kinetics and Melting Behavior. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 101578–101586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.-L.; Jiang, M.; Wang, B.; Deng, J.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, G.-Y.; Tang, J. A Brønsted Acidic Ionic Liquid as an Efficient and Selective Catalyst System for Bioderived High Molecular Weight Poly(Ethylene 2,5-Furandicarboxylate). ChemSusChem 2019, 12, 4927–4935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerasinghe, U.A.; Wu, T.; Chee, P.L.; Yew, P.Y.M.; Lee, H.K.; Loh, X.J.; Dan, K. Deep Eutectic Solvents towards Green Polymeric Materials. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 8497–8527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Hao, J.W.; Mo, L.P.; Zhang, Z.H. Recent Advances in the Application of Deep Eutectic Solvents as Sustainable Media as Well as Catalysts in Organic Reactions. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 48675–48704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abranches, D.O.; Coutinho, J.A.P. Everything You Wanted to Know about Deep Eutectic Solvents but Were Afraid to Be Told. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 2023, 14, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, M.A.R.; Pinho, S.P.; Coutinho, J.A.P. Insights into the Nature of Eutectic and Deep Eutectic Mixtures. J. Solution Chem. 2019, 48, 962–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pätzold, M.; Siebenhaller, S.; Kara, S.; Liese, A.; Syldatk, C.; Holtmann, D. Deep Eutectic Solvents as Efficient Solvents in Biocatalysis. Trends Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 943–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvianti, F.; Maniar, D.; Boetje, L.; Loos, K. Green Pathways for the Enzymatic Synthesis of Furan-Based Polyesters and Polyamides. ACS Symp. Ser. 2020, 1373, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvianti, F.; Maniar, D.; Boetje, L.; Woortman, A.J.J.; van Dijken, J.; Loos, K. Greener Synthesis Route for Furanic-Aliphatic Polyester: Enzymatic Polymerization in Ionic Liquids and Deep Eutectic Solvents. ACS Polym. Au 2023, 3, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paula, V.; Pandeirada, S.V.; Ribeiro-Claro, P.J.A.; Silvestre, A.J.D.; Sousa, A.F. Closing the Loop: Greener and Efficient Hydrolytic Depolymerization for the Recycling of Polyesters Using Biobased Eutectic Solvents. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 3577–3587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yao, X.; Geng, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Lu, X.; Zhang, S. Deep Eutectic Solvents as Highly Active Catalysts for the Fast and Mild Glycolysis of Poly(Ethylene Terephthalate)(PET). Green Chem. 2015, 17, 2473–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paparella, A.N.; Perrone, S.; Salomone, A.; Messa, F.; Cicco, L.; Capriati, V.; Perna, F.M.; Vitale, P. Use of Deep Eutectic Solvents in Plastic Depolymerization. Catalysts 2023, 13, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostinho, B.; Silvestre, A.J.D.; Sousa, A.F. From PEF to RPEF: Disclosing the Potential of Deep Eutectic Solvents in Continuous de-/Re-Polymerization Recycling of Biobased Polyesters. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 3115–3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, R.K.; Hayyan, M.; AlSaadi, M.A.; Ibrahim, S.; Hayyan, A.; Hashim, M.A. Physical Properties of Ethylene Glycol-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 276, 794–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

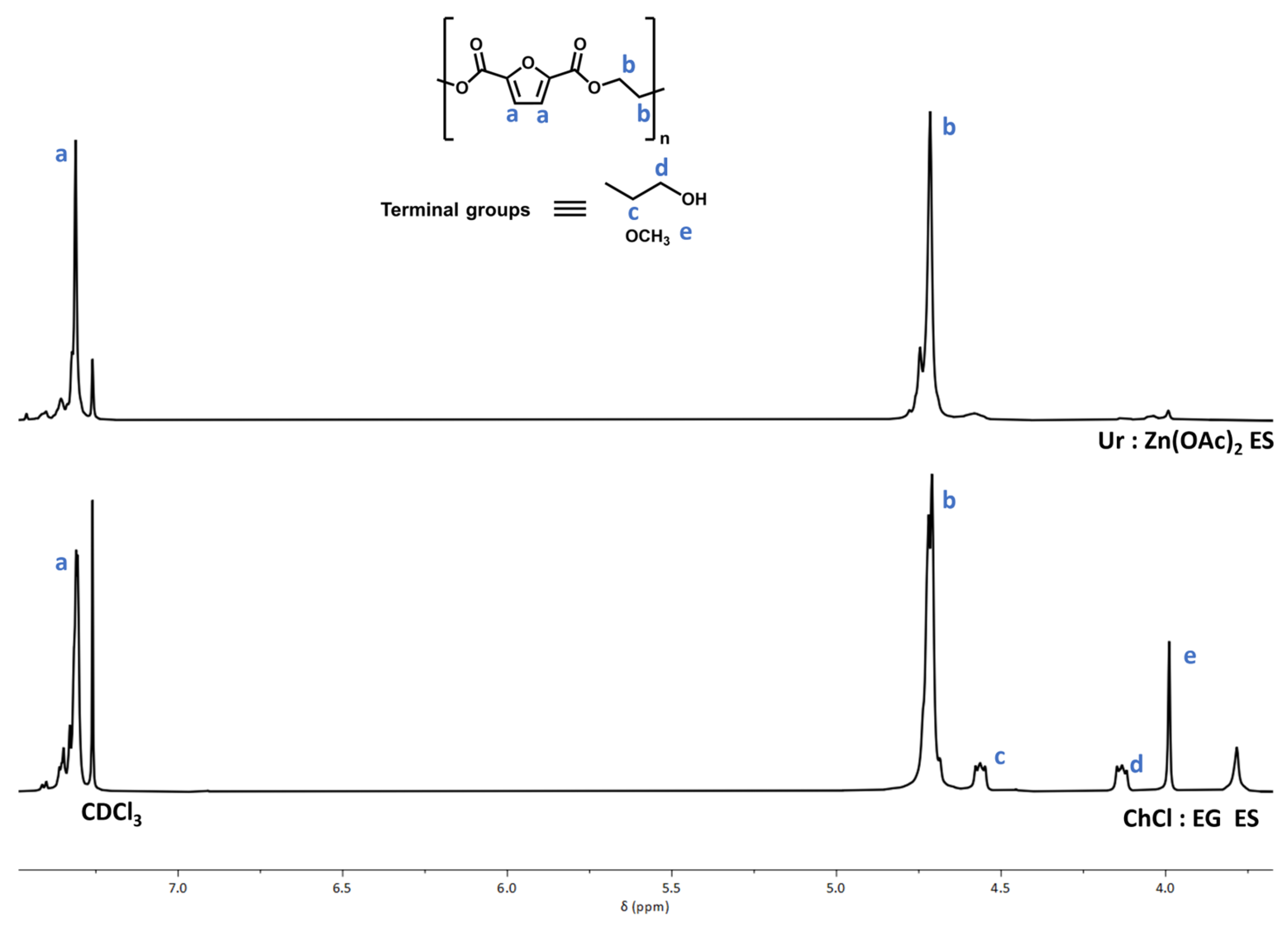

- Izunobi, J.U.; Higginbotham, C.L. Polymer Molecular Weight Analysis by 1H NMR Spectroscopy. J. Chem. Educ. 2011, 88, 1098–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubkiewicz, A.; Paszkiewicz, S.; Szymczyk, A. The Effect of Annealing on Tensile Properties of Injection Molded Biopolyesters Based on 2,5-Furandicarboxylic Acid. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2021, 61, 1536–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, S.; Thiyagarajan, S.; Bougarech, A.; Sebti, F.; Abid, S.; Majdi, A.; Silvestre, A.J.D.; Sousa, A.F. Highly Transparent Films of New Copolyesters Derived from Terephthalic and 2,4-Furandicarboxylic Acids. Polym. Chem. 2019, 10, 5324–5332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, M.; Sousa, A.F.; Silva, N.H.C.S.; Freire, C.S.R.; Andrade, M.; Mendes, A.; Silvestre, A.J.D. Furanoate-Based Nanocomposites: A Case Study Using Poly(Butylene 2,5-Furanoate) and Poly(Butylene 2,5-Furanoate)-Co-(Butylene Diglycolate) and Bacterial Cellulose. Polymers 2018, 10, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ES | Isolation Yield (%) | [η]/dL·g−1 | DPn 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| U:Zn(OAc)2 (4:1 mol:mol) | 71 | 0.2 | 25 |

| ChCl:EG (1:2 mol:mol) | 53 | 0.1 | 10 |

| Catalyst | Temperature/°C | Isolation Yield (%) | [η]/dL·g−1 | DPn 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Stage | 2nd Stage | ||||

| U:Zn(OAc)2 ES | 190 | 220 | 71 | 0.2 | 25 |

| 150 | 180 | 63 | 0.2 | 10 | |

| 120 | 150 | 55 | 0.1 | 9 | |

| Tsynthesis/°C | Tg/°C | Tc/°C | Tm/°C | Td,5%/°C | Td,max/°C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 150–180 | 73.4 | 140 | 211 | 327 | 383 |

| 190–220 | 80.6 | 170 | 206 | 310 | 373 |

| Polymer | Isolation Yield (%) | [η]/dL·g−1 | DPn 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| PTF | 83 | 0.4 | 75 |

| PBF | 74 | 0.2 | 10 |

| Polymer | Tg/°C | Tc/°C | Tm/°C | Td,5%/°C | Td,max/°C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTF | 55 | - | 174 | 339 | 382 |

| PBF | 26 | 109 | 163 | 332 | 389 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Agostinho, B.; de Paula, V.; Silvestre, A.J.D.; Sousa, A.F. The Evaluation of Eutectic Solvents as Catalysts for Mediating the Greener Synthesis of Poly(alkylene 2,5-furandicarboxylate)s. Molecules 2026, 31, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010077

Agostinho B, de Paula V, Silvestre AJD, Sousa AF. The Evaluation of Eutectic Solvents as Catalysts for Mediating the Greener Synthesis of Poly(alkylene 2,5-furandicarboxylate)s. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010077

Chicago/Turabian StyleAgostinho, Beatriz, Vinícius de Paula, Armando J. D. Silvestre, and Andreia F. Sousa. 2026. "The Evaluation of Eutectic Solvents as Catalysts for Mediating the Greener Synthesis of Poly(alkylene 2,5-furandicarboxylate)s" Molecules 31, no. 1: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010077

APA StyleAgostinho, B., de Paula, V., Silvestre, A. J. D., & Sousa, A. F. (2026). The Evaluation of Eutectic Solvents as Catalysts for Mediating the Greener Synthesis of Poly(alkylene 2,5-furandicarboxylate)s. Molecules, 31(1), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010077