Solvent-Mediated Control of Twisted Intramolecular Charge Transfer in 7-(Diethylamino)coumarin-3-carboxylic Acid

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Kamlet-Taft Model and Catalán 4P Model

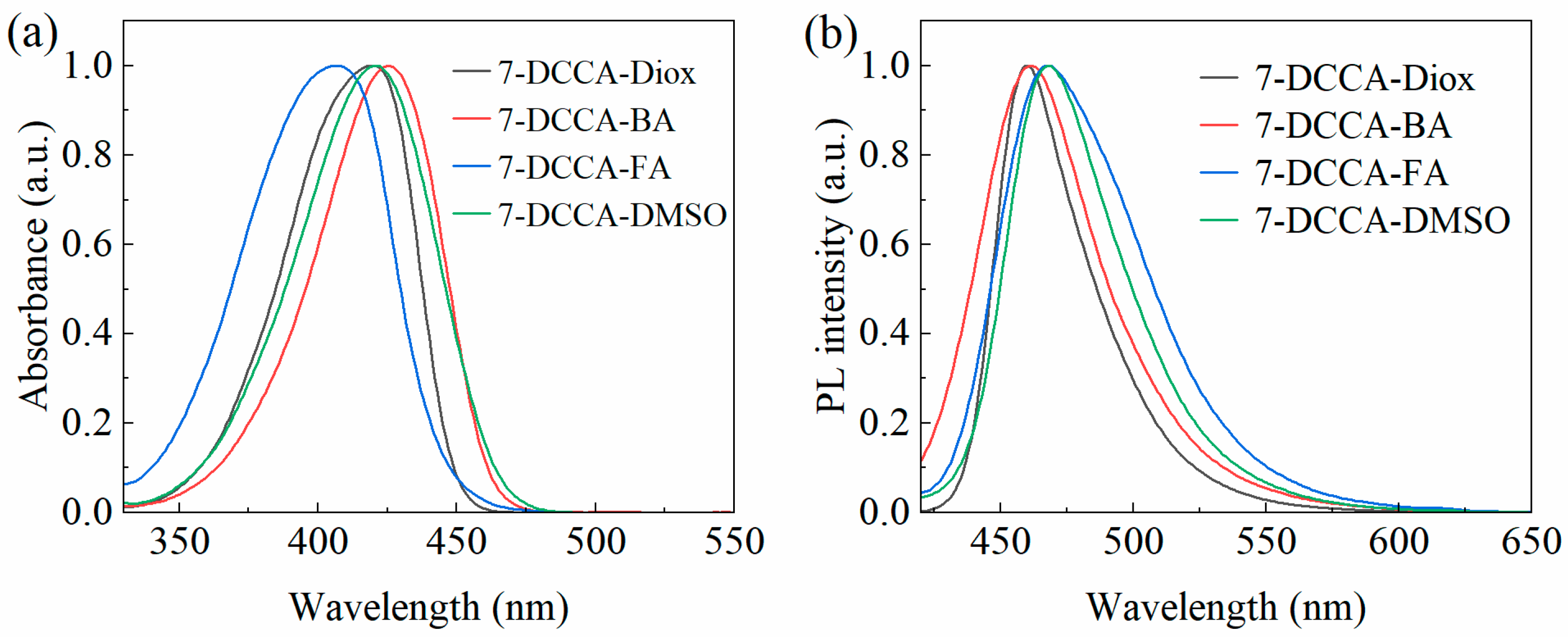

2.2. Steady-State Absorption and Fluorescence Spectra

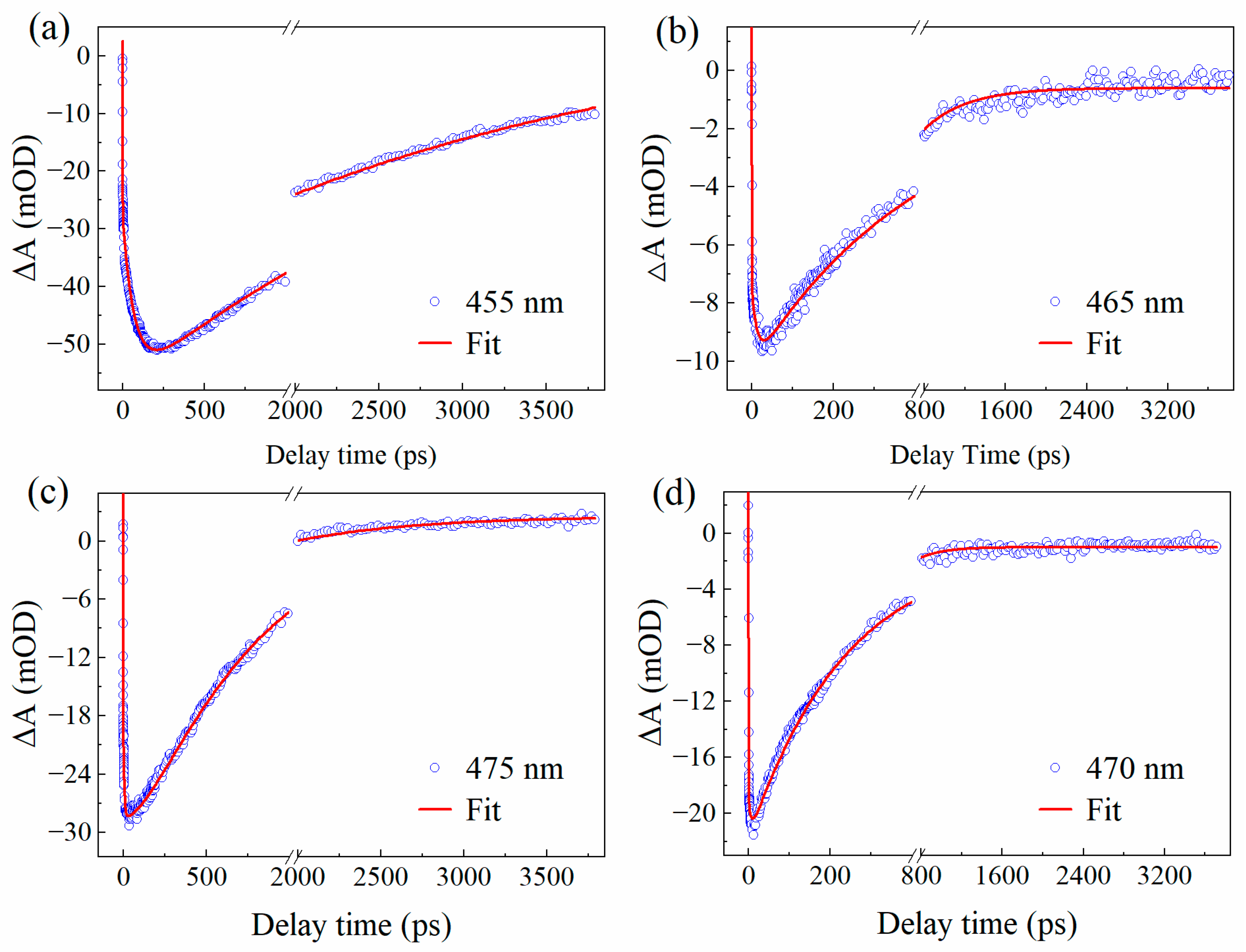

2.3. Transient Absorption Spectroscopy

2.4. Theoretical Calculations

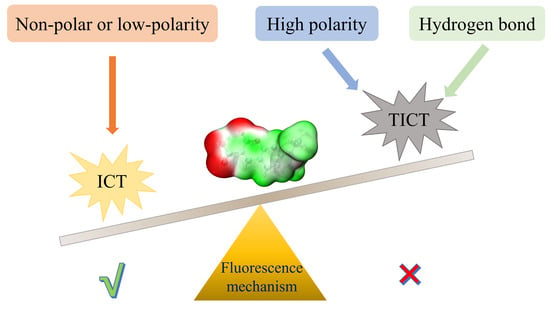

2.5. Excited-State Deactivation Mechanism of 7-DCCA Hydrogen-Bonded Complexes

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Experimental Methods

3.3. Computational Methods

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yan, X.J.; Feng, R.C.; Fu, J.J.; Han, Q.Q.; Liu, Y.L.; Song, Q. Supramolecular Engineering of Twisted Intramolecular Charge Transfer (TICT) Dyes into Bright Fluorophores with Large Stokes Shifts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202516458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.N.; Tan, S.J.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, S.T.; Li, W.J.; Song, Q.B.; Dong, Y.J.; Zhang, C.; Wong, W.-Y. Direct observation of excited state conversion in solid state from a TICT-Type mechanochromic luminogen. J. Lumin. 2021, 237, 118179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.N.; Qi, S.; Zhao, M.; Liu, J.; Jia, T.; Liu, G.N.; Liu, F.M.; Sun, P.; Li, B.; Wang, C.G. Donor-Acceptor molecule with TICT character: A new design strategy for organic photothermal material in solar energy. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 471, 144745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chi, W.; Qiao, Q.; Tan, D.; Xu, Z.; Liu, X. Twisted intramolecular charge transfer (TICT) and twists beyond TICT: From mechanisms to rational designs of bright and sensitive fluorophores. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 12656–12678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joulaei-Zonouz, S.; Wiebe, H.; Prüfert, C.; Loock, H.-P. Twisted-internal charge transfer (TICT) state mechanisms may be less common than expected. New J. Chem. 2024, 48, 4077–4087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippert, E.; Lüder, W.; Moll, F.; Nägele, W.; Boos, H.; Prigge, H.; Seibold-Blankenstein, I. Umwandlung von elektronenanregungsenergie. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1961, 73, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rettig, W. Ladungstrennung in angeregten Zuständen entkoppelter Systeme–TICT-Verbindungen und Implikationen für die Entwicklung neuer Laserfarbstoffe sowie für den Primärprozeß von Sehvorgang und Photosynthese. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1986, 98, 969–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, N.; Rommens, J.; Van der Auweraer, M.; De Schryver, F.C. Laser-induced optoacoustic studies of the non-radiative deactivation of ICT probes DMABN and DMABA. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1997, 264, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parusel, A.B. Excited state intramolecular charge transfer in N, N-heterocyclic-4-aminobenzonitriles: A DFT study. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2001, 340, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, Z.R.; Rotkiewicz, K.; Siemiarczuk, A. Dual fluorescence of donor-acceptor molecules and the twisted intramolecular charge transfer (TICT) states. J. Lumin. 1979, 18, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, Z.R.; Rotkiewicz, K.; Rettig, W. Structural changes accompanying intramolecular electron transfer: Focus on twisted intramolecular charge-transfer states and structures. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 3899–4032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, R.A.; Brown-Xu, S.E.; Nguyen, L.N.; Gustafson, T.L. Probing the solvation structure and dynamics in ionic liquids by time-resolved infrared spectroscopy of 4-(dimethylamino) benzonitrile. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 25151–25157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linet, A.; Nair, A.G.; Achankunju, S.; Rajeev, K.; Unni, N.; Neogi, I. TICT, and Deep-Blue Electroluminescence from Acceptor-Donor-Acceptor Molecules. Chem. Asian J. 2024, 19, e202400721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipem, F.A.; Mishra, A.; Krishnamoorthy, G. The role of hydrogen bonding in excited state intramolecular charge transfer. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 8775–8790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, D.; Li, C.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, K. Hydrogen bond strengthening induces fluorescence quenching of PRODAN derivative by turning on twisted intramolecular charge transfer. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2017, 187, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Gou, Z.; Dong, B.; Tian, M. Tuning the “critical polarity” of TICT dyes: Construction of polarity-sensitive platform to distinguish duple organelles. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2022, 355, 131349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngworth, R.; Roux, B. Simulating the fluorescence of the locally excited state of DMABN in solvents of different polarities. J. Phys. Chem. B 2023, 128, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, H.; Sun, Y.; Gao, J.; Xin, C.; Zhao, H.F.; Jin, G.Y.; Li, H. Switching the ESIPT and TICT process of DP-HPPI via intermolecular hydrogen bonding. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1277, 134800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, C.F.; Han, J.H.; Zhou, Q.; Cao, B.F.; Yin, H.; Shi, Y. Theoretical investigation of intermolecular hydrogen bond induces fluorescence quenching phenomenon for Coumarin-1. J. Lumin. 2020, 221, 117110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Zhang, X.D.; Li, Z.B.; Xue, B.Q.; Bai, X.L. The investigation of the ultrafast excited state deactivation mechanisms for coumarin 307 in different solvents. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 21746–21753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, J.; Xiao, J.; Xue, B.Q.; Liu, D.D.; Du, B.Q.; Bai, X.L. Influence of hydrogen bonding on twisted intramolecular charge transfer in coumarin dyes: An integrated experimental and theoretical investigation. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 29879–29889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, A.; Seth, D. Photophysical properties of 7-(diethylamino)coumarin-3-carboxylic acid in the nanocage of cyclodextrins and in different solvents and solvent mixtures. Photochem. Photobiol. 2013, 89, 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.G.; Cole, J.M.; Chow, P.C.; Zhang, L.; Tan, Y.Z.; Zhao, T. Dye aggregation and complex formation effects in 7-(diethylamino)-coumarin-3-carboxylic acid. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 13042–13051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A.; Maity, B.; Seth, D. Supramolecular interaction between a hydrophilic coumarin dye and macrocyclic hosts: Spectroscopic and calorimetric study. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118, 9768–9781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamlet, M.J.; Abboud, J.L.; Taft, R.W. The solvatochromic comparison method. 6. The .pi.* scale of solvent polarities. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977, 99, 6027–6038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalán, J. Toward a Generalized Treatment of the Solvent Effect Based on Four Empirical Scales: Dipolarity (SdP, a New Scale), Polarizability (SP), Acidity (SA), and Basicity (SB) of the Medium. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 5951–5960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.G.; Cole, J.M.; Low, K.S. Solvent Effects on the UV–vis Absorption and Emission of Optoelectronic Coumarins: A Comparison of Three Empirical Solvatochromic Models. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 14731–14741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emenike, B.U.; Sevimler, A.; Farshadmand, A.; Roman, A.J. Rationalizing hydrogen bond solvation with Kamlet–Taft LSER and molecular torsion balances. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25, 17808–17814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, B.; Zakerhamidi, M.S.; Shamkhali, A.N.; Kian, R.; Sadeghan, A.A. Solvent polarity effect on photophysical properties of some aromatic azo dyes with focus on tautomeric and toxicity competition. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamlet, M.J.; Abboud, J.L.M.; Abraham, M.H.; Taft, R. Linear solvation energy relationships. 23. A comprehensive collection of the solvatochromic parameters,. pi.*,. alpha., and. beta., and some methods for simplifying the generalized solvatochromic equation. J. Org. Chem. 1983, 48, 2877–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, B.; Chatterjee, A.; Seth, D. Photophysics of a coumarin in different solvents: Use of different solvatochromic models. Photochem. Photobiol. 2014, 90, 734–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basavaraja, J.; Kumar, H.S.; Inamdar, S.; Wari, M. Estimation of ground and excited state dipole moment of laser dyes C504T and C521T using solvatochromic shifts of absorption and fluorescence spectra. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2016, 154, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debnath, T.; Maity, P.; Lobo, H.; Singh, B.; Shankarling, G.S.; Ghosh, H.N. Extensive Reduction in Back Electron Transfer in Twisted Intramolecular Charge-Transfer (TICT) Coumarin-Dye-Sensitized TiO2 Nanoparticles/Film: A Femtosecond Transient Absorption Study. Chem. Eur. J. 2014, 20, 3510–3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, L.; Yin, H.; Shi, Y.; Jin, M.X.; Ding, D.J. Different mechanisms of ultrafast excited state deactivation of coumarin 500 in dioxane and methanol solvents: Experimental and theoretical study. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 1205–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Cao, B.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Sun, C.; Li, B.; Yin, H.; Shi, Y. The role played by solvent polarity in regulating the competitive mechanism between ESIPT and TICT of coumarin (E-8-((4-dimethylamino-phenylimino)-methyl)-7-hydroxy-4-methyl-2H-chromen-2-one). Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2020, 231, 118086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barik, A.; Kumbhakar, M.; Nath, S.; Pal, H. Evidence for the TICT mediated nonradiative deexcitation process for the excited coumarin-1 dye in high polarity protic solvents. J. Chem. Phys. 2005, 315, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabavathi, N.; Nilufer, A.; Krishnakumar, V. Vibrational spectroscopic (FT-IR and FT-Raman) studies, natural bond orbital analysis and molecular electrostatic potential surface of Isoxanthopterin. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2013, 114, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadam, M.M.; Patil, D.; Sekar, N. 4-(Diethylamino) salicylaldehyde based fluorescent Salen ligand with red-shifted emission–A facile synthesis and DFT investigation. J. Lumin. 2018, 204, 354–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yin, H.; Liu, X.; Shi, Y.; Jin, M.; Ding, D. An experimental and theoretical study of solvent hydrogen-bond-donating capacity effects on ultrafast intramolecular charge transfer of LD 490. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2017, 184, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cao, B.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, X.; Li, B.; Su, X.; Shi, Y. Enhancing fluorescence of benzimidazole derivative via solvent-regulated ESIPT and TICT process: A TDDFT study. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2021, 258, 119862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, W.; Cheng-Ze, H.; Yi, L.; Li-Wei, L.; Guang-Yue, L. Long-range substituent effect on the TICT process of a fluorescent probe for reactive oxidative species. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2023, 829, 140772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Qiang, N.; Liu, Z.; Lu, M.; Shen, Y.; Zou, J.; Yang, J.; Liu, G. Multi-Stimuli-Responsive Fluorescent Molecule with AIE and TICT Properties Based on 1, 8-Naphthalimide. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wang, X.; Gao, H.; Song, J. D-π-A type red/NIR BioAIEgens derived from rosin: Synthesis, structure-activity relationship, and application in cell imaging. J. Lumin. 2025, 281, 121133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, A.D.; Jacquemin, D. TD-DFT benchmarks: A review. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2013, 113, 2019–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, Y.; Xing, J.; Qu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gao, J. Separation of ethyl acetate and ethanol by imidazole ionic liquids based on mechanism analysis and liquid–liquid equilibrium experiment. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 371, 121108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.; Srivastava, A.; Kumar, P.; Tandon, P.; Maurya, R.; Singh, R. Vibrational spectroscopic, NBO, AIM, and multiwfn study of tectorigenin: A DFT approach. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1217, 128443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emamian, S.; Lu, T.; Kruse, H.; Emamian, H. Exploring nature and predicting strength of hydrogen bonds: A correlation analysis between atoms-in-molecules descriptors, binding energies, and energy components of symmetry-adapted perturbation theory. J. Comput. Chem. 2019, 40, 2868–2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, J.; Zhang, X.D.; Peng, Y.; Bai, X.L. Unraveling the effect of solvents on the excited state dynamics of C540A by experimental and theoretical study. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 4924–4931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, T.; Chen, F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T. A comprehensive electron wavefunction analysis toolbox for chemists. Multiwfn. J. Chem. Phys. 2024, 161, 082503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Petersson, G.A. Gaussian 09; Revision D. 01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2009; Volume 620, Available online: http://www.gaussian.com (accessed on 15 September 2024).

| Solvent | α | β | π* | SA | SB | SP | SdP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,4-dioxane | 0.00 | 0.37 | 0.55 | 0.000 | 0.444 | 0.737 | 0.312 |

| Butanol | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.47 | 0.341 | 0.809 | 0.674 | 0.655 |

| Formamide | 0.71 | 0.48 | 0.97 | 0.549 | 0.414 | 0.814 | 1.006 |

| Dimethyl sulfoxide | 0.00 | 0.76 | 1.00 | 0.072 | 0.647 | 0.830 | 1.000 |

| Acetonitrile | 0.19 | 0.40 | 0.75 | 0.044 | 0.286 | 0.645 | 0.974 |

| Tetrahydrofuran | 0.00 | 0.55 | 0.58 | 0.000 | 0.591 | 0.714 | 0.634 |

| N,N-dimethyIformamide | 0.00 | 0.69 | 0.88 | 0.031 | 0.613 | 0.977 | 0.759 |

| Ethanol | 0.86 | 0.75 | 0.54 | 0.400 | 0.658 | 0.633 | 0.783 |

| Methanol | 0.98 | 0.66 | 0.60 | 0.605 | 0.545 | 0.608 | 0.904 |

| Ethyl acetate | 0.00 | 0.45 | 0.55 | 0.000 | 0.542 | 0.656 | 0.603 |

| Acetic acid | 1.12 | 0.45 | 0.64 | 0.689 | 0.390 | 0.651 | 0.676 |

| dichloromethane | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.82 | 0.040 | 0.178 | 0.761 | 0.769 |

| H2O | 1.17 | 0.47 | 1.09 | 1.062 | 0.025 | 0.681 | 0.997 |

| chloroform | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.58 | 0.047 | 0.071 | 0.783 | 0.614 |

| 2-propanol | 0.76 | 0.84 | 0.48 | 0.283 | 0.830 | 0.633 | 0.808 |

| Cyclohexane | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.000 | 0.073 | 0.683 | 0.000 |

| Solvent | Abs | Em | Stokes Shift |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1,4-dioxane | 2.952 | 2.695 | 2017 |

| Butanol | 2.924 | 2.689 | 1893 |

| Formamide | 3.046 | 2.638 | 3293 |

| Dimethyl sulfoxide | 2.938 | 2.644 | 2375 |

| Acetonitrile | 2.945 | 2.666 | 2070 |

| Tetrahydrofuran | 2.890 | 2.684 | 1665 |

| N,N-dimethyIformamide | 2.897 | 2.610 | 2313 |

| Ethanol | 2.960 | 2.678 | 2268 |

| Methanol | 2.986 | 2.689 | 2404 |

| Ethyl acetate | 2.910 | 2.683 | 1828 |

| Acetic acid | 3.031 | 2.701 | 2663 |

| dichloromethane | 2.980 | 2.661 | 2580 |

| H2O | 3.084 | 2.588 | 3999 |

| chloroform | 2.959 | 2.672 | 2315 |

| 2-propanol | 2.924 | 2.713 | 1703 |

| Cyclohexane | 2.966 | 2.850 | 934 |

| Kamlet-Taft Model | Catalán 4P Model | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ν0 | a | b | s | R2 | ν0 | CSA | CSB | CSP | CSdP | R2 | |

| Abs | 23.67 | 0.80 | −1.15 | 0.67 | 0.875 | 23.90 | 1.01 | −0.84 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.881 |

| Em | 22.75 | 0.02 | −0.26 | −1.55 | 0.881 | 23.01 | −0.23 | 0.35 | −1.71 | −0.48 | 0.922 |

| Stokes shift | 0.91 | 0.81 | −0.88 | 2.20 | 0.961 | 0.87 | 1.31 | −1.14 | 1.88 | 0.40 | 0.958 |

| Molecule | 7-DCCA-Diox | 7-DCCA-BA | 7-DCCA-FA | 7-DCCA-DMSO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 3.06 (0.744) H → L98.4% | 3.01 (0.760) H → L98.6% | 3.08 (0.845) H → L98.4% | 3.05 (0.791) H → L98.4% |

| S2 | 3.42 (0.000) | 3.56 (0.002) | 3.75 (0.004) | 3.23 (0.000) |

| S3 | 3.84 (0.000) | 4.10 (0.002) | 4.33 (0.000) | 3.26 (0.000) |

| S4 | 4.12 (0.007) | 4.11 (0.000) | 4.38 (0.038) | 4.1.0 (0.004) |

| S5 | 4.16 (0.000) | 4.41 (0.167) | 4.39 (0.138) | 4.22 (0.000) |

| S6 | 4.48 (0.123) | 4.66 (0.000) | 4.56 (0.001) | 4.26 (0.000) |

| Molecule | 7-DCCA-Diox | 7-DCCA-BA | 7-DCCA-FA | 7-DCCA-DMSO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 2.78 (0.446) H → L99.1% | 2.77 (0.916) H → L99.1% | 2.74 (0.999) H → L99.1% | 2.76 (0.924) H → L99.2% |

| S2 | 3.04 (0.000) | 3.85 (0.015) | 3.85 (0.021) | 3.04 (0.000) |

| S3 | 3.51 (0.004) | 3.90 (0.064) | 4.15 (0.000) | 3.06 (0.000) |

| Sample | Solvent | τ1/ps | τ2/ps | τ3/ps | τ4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7-DCCA | Diox (a) | 0.43 ± 0.01 | — | 69.77 ± 1.21 | 2806.31 ± 82.63 |

| BA (b) | 0.45 ± 0.01 | — | 25.08 ± 0.84 | 418.35 ± 6.57 | |

| FA (c) | 0.40 ± 0.02 | 5.51 ± 0.32 | 154.05 ± 18.59 | 730.33 ± 17.31 | |

| DMSO (d) | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 3.01 ± 0.51 | 41.45 ± 6.57 | 216.73 ± 2.21 |

| BCP | ρ(rBCP) (au) | ΔE (kcal/mol) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7DCCA-Diox | C1-O1···H1 | 0.0061 | −0.6185 |

| C3-O2···H2 | 0.0052 | −0.4177 | |

| 7DCCA-BA | C1-O1···H1 | 0.2585 | −56.9239 |

| C3-O2···H2 | 0.2741 | −60.4039 | |

| 7DCCA-FA | C1-O1···H1 | 0.3191 | −70.4425 |

| C3-O2···H2 | 0.2815 | −62.0547 | |

| 7DCCA-DMSO | C1-O1···H1 | 0.2708 | −59.6678 |

| C3-O2···H2 | 0.2717 | −59.8685 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bai, X.; Xiao, J.; Du, B.; Liu, D.; Wang, Y.; Shi, S.; Ge, J. Solvent-Mediated Control of Twisted Intramolecular Charge Transfer in 7-(Diethylamino)coumarin-3-carboxylic Acid. Molecules 2026, 31, 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010076

Bai X, Xiao J, Du B, Liu D, Wang Y, Shi S, Ge J. Solvent-Mediated Control of Twisted Intramolecular Charge Transfer in 7-(Diethylamino)coumarin-3-carboxylic Acid. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):76. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010076

Chicago/Turabian StyleBai, Xilin, Jing Xiao, Bingqi Du, Duidui Liu, Yanzhuo Wang, Shujing Shi, and Jing Ge. 2026. "Solvent-Mediated Control of Twisted Intramolecular Charge Transfer in 7-(Diethylamino)coumarin-3-carboxylic Acid" Molecules 31, no. 1: 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010076

APA StyleBai, X., Xiao, J., Du, B., Liu, D., Wang, Y., Shi, S., & Ge, J. (2026). Solvent-Mediated Control of Twisted Intramolecular Charge Transfer in 7-(Diethylamino)coumarin-3-carboxylic Acid. Molecules, 31(1), 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010076