Analytical Determination of Heavy Metals in Water Using Carbon-Based Materials

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Development of Electrochemical Systems Based on Carbon Materials for the Detection of Heavy Metals

2.1. Conventional Carbon Nanomaterials

2.2. Carbon Materials Derived from MOFs

2.3. Biomass-Based Carbon Materials

2.4. Electrochemical Sensing Mechanisms of Carbon-Based Materials

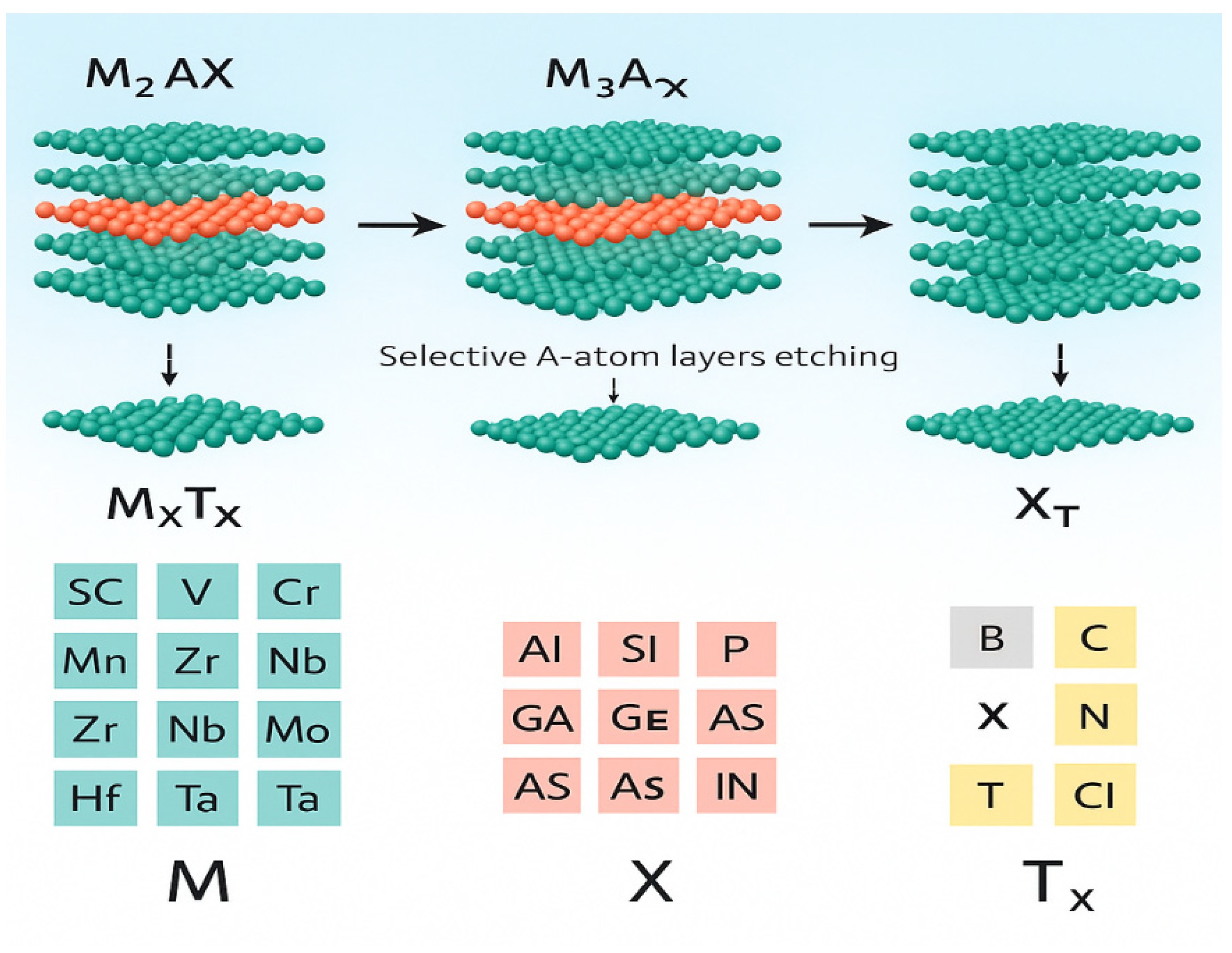

3. Development of Electrochemical Sensors Based on MXene Materials

| Etching Method | Etching Agent | Etching Temperature (°C) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluoride Acids | HF | Room-55 | [105] |

| H2O2 + HF | 40 | [106] | |

| HCl + HF | 35–55 | [107] | |

| HCl + (Na, K, or NH4F) | 30–60 | [108] | |

| NH4HF2 | Room | [109] | |

| Alkaline Methods | NaOH | 270 | [110] |

| Hydrothermal Method | NaBF4, HCl | 180 | [111] |

| Molten Salts | LiF + NaF + KF | 550 | [112] |

| Electrochemical | NH4Cl/TMAOH | Room | [113] |

| Lewis Acids | ZnCl2 | 550 | [114] |

| Chemical Vapor Phase | 3D Graphene/Ti3AlC2/PDMS membrane | - | [115] |

4. Objective and Scope of the Research

5. Experimental Section

5.1. Experimental Methods and Principles

5.2. Preparation of Required Solutions

- (1)

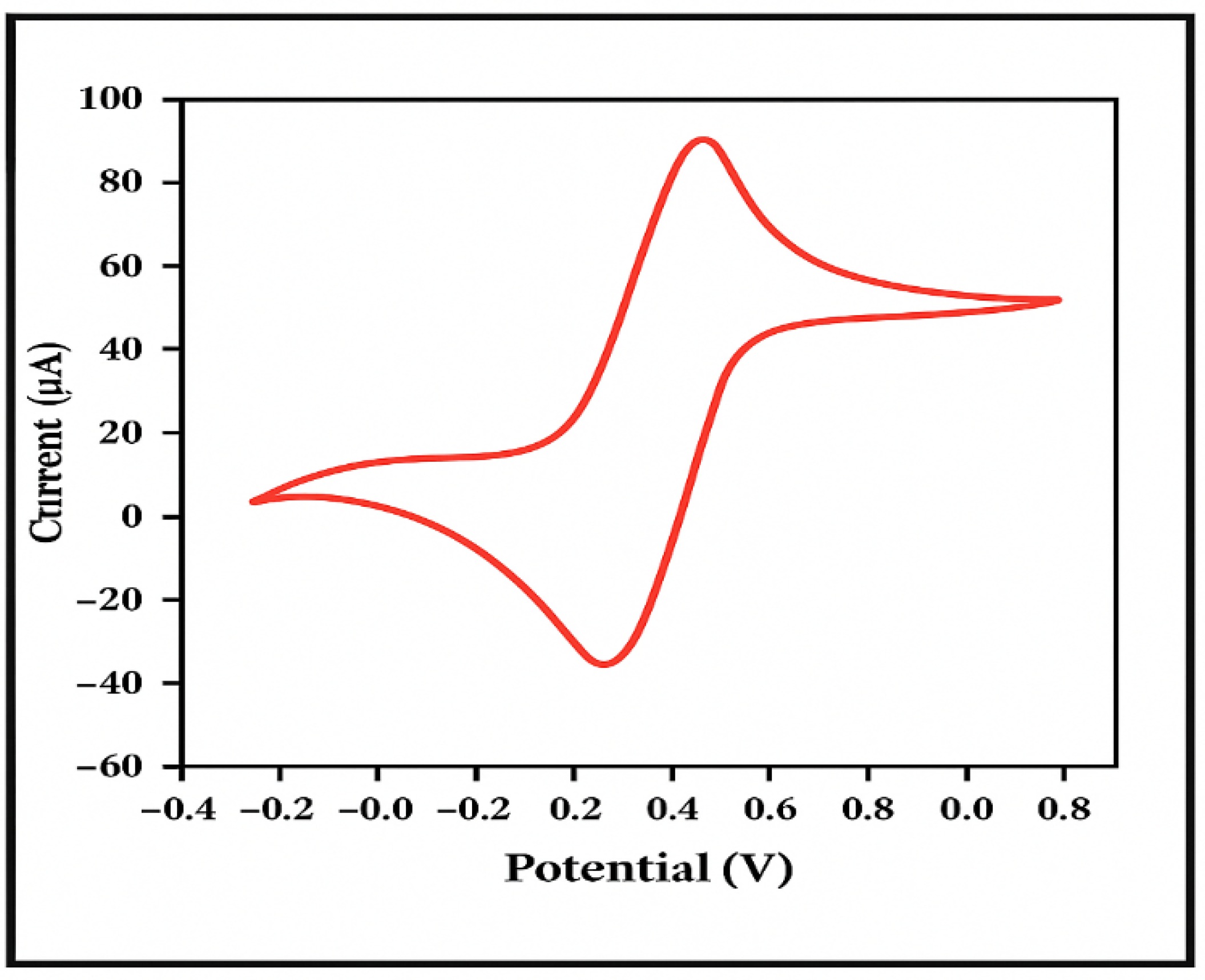

- GCE Test Solution: The GCE test solution is a mixture of aqueous solutions containing 5 mM K3Fe(CN)6, 5 mM K4Fe(CN)6, and 0.1 M KCl. Accurately weigh 0.164 g of solid K3Fe(CN)6, 0.211 g of solid K4Fe(CN)6, and 0.74 g of solid KCl. Place them in a beaker and add a small amount of deionized water to fully dissolve and mix the three solids. Then, transfer the mixture to a 100 mL volumetric flask and add deionized water to reach the final volume of 100 mL.

- (2)

- Sample Test Solution: Transfer 1 mL of the Bi3+ standard solution with a concentration of 100 μg/mL from the stock bottle into a 10 mL centrifuge tube for further use. Then, pipette 1 mL each of the Pb2+ and Cd2+ standard solutions with a concentration of 1000 μg/mL and dilute them with distilled water to a concentration of 100 μg/mL to obtain stock solutions of Pb2+ and Cd2+. During testing, dilute the 100 μg/mL Pb2+ and Cd2+ stock solutions to a working concentration of 2 μg/mL.

- (3)

- Acetate–Sodium Acetate Buffer (pH = 4.5): Since Bi3+ easily undergoes hydrolysis under neutral or alkaline conditions to form BiOCl precipitate, which can interfere with the testing process, hydrolysis is suppressed in acidic media. Therefore, a commonly used laboratory buffer solution—0.1 M acetic acid–sodium acetate buffer with pH = 4.5—was selected as the supporting electrolyte for this experiment. Accurately weigh 3.86 g of glacial acetic acid and 2.93 g of sodium acetate, place them in a beaker, add a small amount of deionized water to fully dissolve and mix, then transfer the solution to a 1 L volumetric flask and make up the volume to 1 L with deionized water. The pH of the solution was measured using a pH meter and confirmed to be 4.5. After preparation, store all solutions in a refrigerator at 4 °C.

5.3. Pre-Treatment of GCE (Glassy Carbon Electrode)

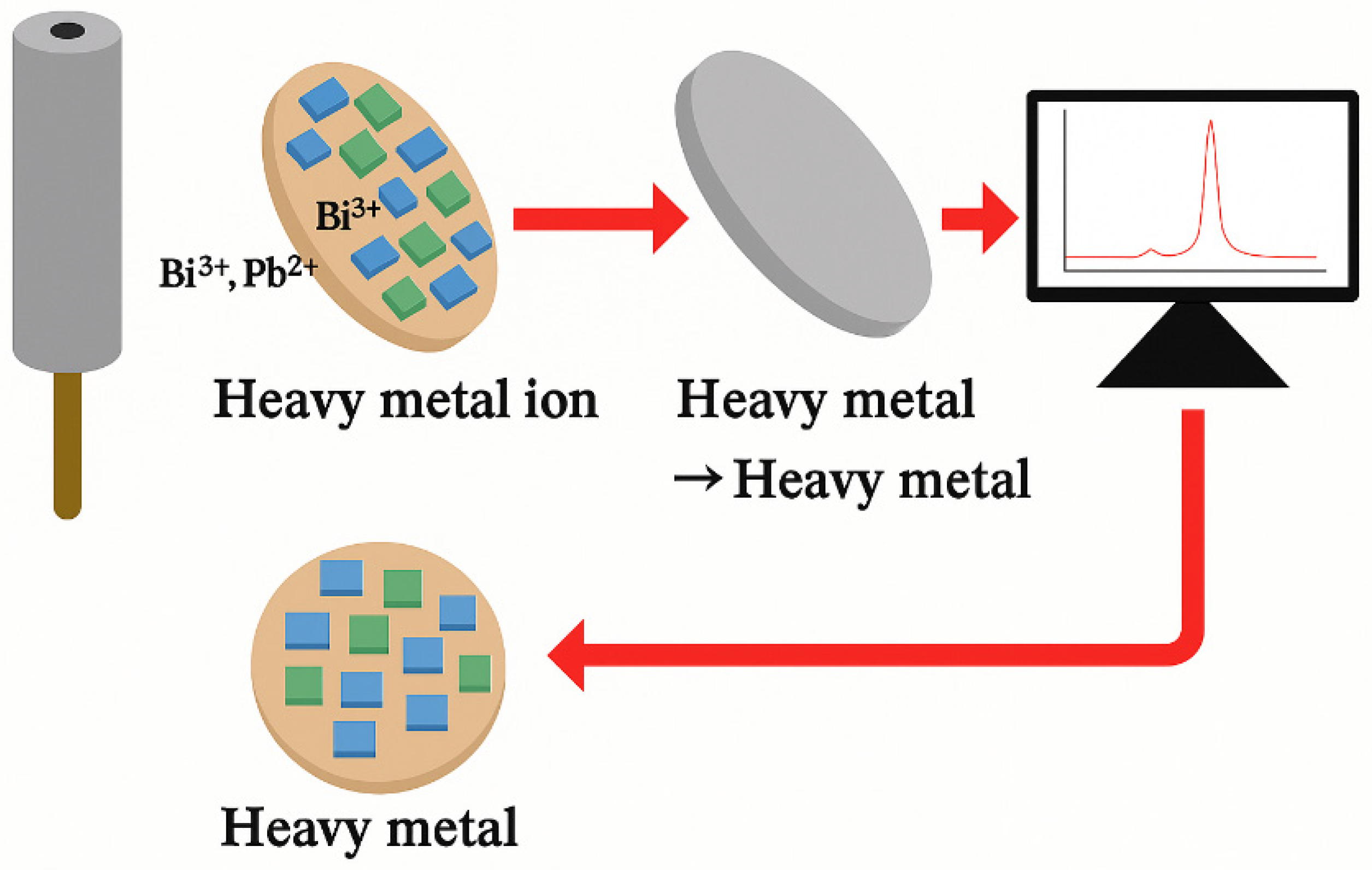

5.4. Voltammetric Testing of Pb2+ and Cd2+ Stripping

5.5. MXene-Anode-Glucose Oxidase/Prussian Blue/ITO-Cathode Self-Powered System for the Determination of Mercury (II) in Water

6. Results and Discussion

6.1. Determination of Trace Lead (II) and Cadmium (II) in Water Using a Glassy Carbon Electrode

6.2. Analytical Performance of the MXene–GOD/PB/ITO Self-Powered Sensor for Hg2+ Detection

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, L.; Guo, D.K.; Liu, K.; Meng, H.; Zheng, Y.; Yuan, F.; Zhu, G. Levels, sources, and spatial distribution of heavy metals in soils from a typical coal industrial city of Tangshan, China. Catena 2019, 175, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.P.; Li, Z.A.; Gascó, G.; Méndez, A.; Shen, Y.; Paz-Ferreiro, J. Use of magnetic biochars for the immobilization of heavy metals in a multi-contaminated soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 622–623, 892–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, A.; Hoadley, F.A.A. An evaluation of a hybrid ion exchange electrodialysis process in the recovery of heavy metals from simulated dilute industrial wastewater. Water Res. 2012, 46, 3364–3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashir, A.; Malik, L.A.; Ahad, S.; Manzoor, T.; Bhat, M.A.; Dar, G.N.; Pandith, A.H. Removal of heavy metal ions from aqueous system by ion-exchange and biosorption methods. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2019, 17, 729–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D. Heavy Metal Pollution and Prevention in Water Bodies. Chem. Ind. Manag. 2019, 511, 37–38. [Google Scholar]

- Tchounwou, P.B.; Yedjou, C.G.; Patlolla, A.K.; Sutton, D.J. Heavy Metal Toxicity and the Environment. In Molecular, Clinical and Environmental Toxicology; Springer: Basel, Switzerland, 2012; Volume 3, pp. 133–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.L.; Yang, X.E.; Stoffella, P.J. Trace elements in agro-ecosystems and impacts on the environment. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2005, 10, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasharathy, S.; Arjunan, S.; Basavaraju, A.M.; Murugasen, V.; Ramachandran, S.; Keshav, R.; Murugan, R. Mutagenic, carcinogenic, and teratogenic effect of heavy metals. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2022, 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran, K.; Flora, S.J.S. Strategies for safe and effective therapeutic measures for chronic arsenic and lead poisoning. J. Occup. Health 2005, 47, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, J.R.; Zhou, L.; Zhao, Y.; Jin, W.; Shen, H.; Zhang, F. Effects of long-term high-level lead exposure on the immune function of workers. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health 2022, 77, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekong, E.B.; Jaar, B.; Weaver, V.M. Lead-related nephrotoxicity: A review of the epidemiologic evidence. Kidney Int. 2006, 70, 2074–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theron, A.J.; Tintinger, G.R.; Anderson, R. Harmful interactions of non-essential heavy metals with cells of the innate immune system. J. Clin. Toxicol. 2012, S3, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman, A.J. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. J. Clin. Pathol. 1995, 48, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.; Zheng, W.; Gao, Y. Health hazards of cadmium and advances in intervention treatment research. J. Environ. Health 2007, 147, 739–742. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y. A brief discussion on the hazards of heavy metals in water and detection methods. Rural Econ. Technol. 2016, 27, 64–65. [Google Scholar]

- Siblerud, R.; Mutter, J.; Moore, J.; Walach, H. A hypothesis and evidence that mercury may be an etiological factor in Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 5152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.Y.; Murphy, A.; Sun, H.; Costa, M. Molecular and epigenetic mechanisms of Cr(VI)-induced carcinogenesis. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2019, 377, 114636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, D.F.; de Castro, B.S.; Recktenvald, M.C.N.; da Costa Júniorc, W.A.; da Silva, F.X.; de Menezes Alves, C.L.; Froehlich, J.D.; Bastos, W.R.; Ott, A.M.T. Mercury in wild animals and fish and health risk for indigenous Amazonians. Food Addit. Contam. Part B 2021, 14, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeneli, L.; Sekovanić, L.; Ajvazi, A.; Kurti, L.; Daci, N. Alterations in antioxidant defense system of workers chronically exposed to arsenic, cadmium and mercury from coal flying ash. Environ. Geochem. Health 2016, 38, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, A.P.; Mazzella, M.J.; Malin, A.J.; Hair, G.M.; Busgang, S.A.; Saland, J.M.; Curtin, P. Combined exposure to lead, cadmium, mercury, and arsenic and kidney health in adolescents age 12–19 in NHANES 2009–2014. Environ. Int. 2019, 131, 104993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zheng, Y.X.; Dong, X.Y.; Zou, X.T. Effect of mercury chloride on oxidative stress and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 signalling molecule in liver and kidney of laying hens. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2018, 102, 1199–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.Y.; Sanders, A.P.; Saland, J.M.; Wright, R.O.; Arora, M. Environmental exposures and pediatric kidney function and disease: A systematic review. Environ. Res. 2017, 158, 625–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Brocato, J.; Costa, M. Oral chromium exposure and toxicity. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2015, 2, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhitkovich, A. Importance of chromium-DNA adducts in mutagenicity and toxicity of chromium(VI). Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2005, 18, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, T.J.; Ceryak, S.; Patierno, S.R. Complexities of chromium carcinogenesis: Role of cellular response, repair and recovery mechanisms. Mutat. Res./Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2003, 533, 3–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickens, K.P.; Steven, S.R.; Ceryak, S. Chromium genotoxicity: A double-edged sword. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2010, 188, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.L.; Zheng, P.; Su, Z.K.; Hu, G.; Jia, G. Perspectives of genetic damage and epigenetic alterations by hexavalent chromium: Time evolution based on a bibliometric analysis. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2021, 34, 684–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.S.; Song, K.H.; Chung, J.Y. Health effects of chronic arsenic exposure. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2014, 47, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, A.; Zok, D.; Reinhard, S.; Woche, S.K.; Guggenberger, G.; Steinhauser, G. Separation of ultratraces of radiosilver from radiocesium for environmental nuclear forensics. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 5249–5257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.S.; Gao, X.; Pan, B. Nanoconfinement-mediated water treatment: From fundamental to application. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 8509–8526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Liu, W.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y. Recent advance of detection method of heavy metal ions in water. Phys. Test. Chem. Anal. Part B Chem. Anal. 2012, 48, 496–503. [Google Scholar]

- Divrikli, U.; Kartal, A.A.; Soylak, M.; Elci, L. Preconcentration of Pb(II), Cr(III), Cu(II), Ni(II) and Cd(II) ions in environmental samples by membrane filtration prior to their flame atomic absorption spectrometric determinations. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 145, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Lin, N.; Zhang, J.; He, R. Determination of Pb and Cr in drinking water by graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometry. Metall. Anal. 2001, 21, 55–57. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.J.; Gan, W.E.; Wan, L.Z.; Zhang, H.; He, Y. Determination of mercury by electrochemical cold vapor generation atomic fluorescence spectrometry using polyaniline modified graphite electrode as cathode. Spectrochim. Acta Part B At. Spectrosc. 2010, 65, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhang, H.; Huang, Q.; Ju, W.; Zhang, S. Determination of trace molybdenum in water samples by wavelength-dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectrometry. Chem. Propellants Polym. Mater. 2014, 12, 72–74. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Z.; Shan, G.; Qi, D. Detection of heavy metal content in lake bottom sediments using EDXRF. J. Changchun Univ. Sci. Technol. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2015, 38, 99–102. [Google Scholar]

- Arain, M.A.; Wattoo, F.H.; Wattoo, M.H.S.; Ghanghro, A.B.; Tirmizi, S.A.; Iqbal, J.; Arain, S.A. Simultaneous determination of metal ions as complexes of pentamethylene dithiocarbamate in Indus river water, Pakistan. Arab. J. Chem. 2009, 2, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruzzoniti, M.C.; Mentasti, E.; Sarzanini, C. Simultaneous determination of inorganic anions and metal ions by suppressed ion chromatography. Anal. Chim. Acta 1999, 382, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H. Determination of heavy metals in water samples by ICP-MS. Chem. Ind. Manag. 2020, 34, 172–173. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Regan, F. Rapid detection of copper ions in industrial wastewater using a test strip method. Ind. Water Wastewater 2013, 44, 86–89. [Google Scholar]

- Gharehbaghi, M.; Shemirani, F.; Farahani, M.D. Cold-induced aggregation microextraction based on ionic liquids and fiber optic-linear array detection spectrophotometry of cobalt in water samples. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 165, 1049–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.B.; Qiao, B.; Zhang, N.; He, L. Direct detection of ultra-trace vanadium (V) in natural waters by flow-injection chemiluminescence with controlled-reagent-release technology. J. Geochem. Explor. 2009, 103, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Feng, C.; Liu, X.; Qi, S.; Xing, W.; Yuan, C. Research progress on detection method for heavy metal ions. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2020, 20, 3404–3413. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, T.; Li, L.; Yang, H. Advances in phosphate ion-selective electrode research. Sens. Microsyst. 2015, 34, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.W.; Li, L.; Yu, S.T.; He, L. Polymerization of fatty acid methyl ester using acidic ionic liquid as catalyst. Chin. J. Catal. 2010, 31, 1433–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedlechowicz, I.; Sokalski, T.; Lewenstam, A.; Maj-Zurawska, M. Calcium ion-selective electrodes under galvanostatic current control. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2005, 108, 836–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.; Wang, X.; Fan, Y.C.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Hu, G.; He, C.; Jin, C. Determination of total mercury in seafood by ion-selective electrodes based on a thiol functionalized ionic liquid. J. Food Drug Anal. 2018, 26, 670–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Wang, B.; Li, J.; Wang, F.; Yuan, Q.; Hu, G.; Dong, A.; Gan, W. An efficient electrochemical sensor based on three-dimensionally interconnected mesoporous graphene framework for simultaneous determination of Cd(II) and Pb(II). Electrochim. Acta 2016, 222, 1371–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalaby, E.A.; Beltagi, A.M.; Hathoot, A.A.; Abdelazzem, M. Development of a sensor based on poly(1,2-diaminoanthraquinone) for individual and simultaneous determination of mercury(II) and bismuth(III). Electroanalysis 2022, 34, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somer, G.; Kalaycı, S. New and simple method for the simultaneous determination of Fe, Cu, Pb, Zn, Bi, Cr, Mo, Se, and Ni in dried red grapes using differential pulse polarography. Food Anal. Methods 2014, 8, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Liang, Q.; Li, J. Determination of zinc, cadmium and lead by antimony electrode potential stripping method. Chin. J. Inorg. Anal. Chem. 2011, 1, 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Mukatayeva, Z.; Bakytkarim, Y.; Nuerbaheti, W.; Tileuberdi, Y.; Shadin, N.; Assirbayeva, Z.; Zhussupova, L. Electrochemical Sensor based on Silicon Carbide and cokederived Carbon Nanocomposites for Sensitive Detection of Lead Ions. ES Mater. Manuf. 2025, 29, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akanji, S.P.; Ama, O.M.; Ray, S.S.; Osifo, P.O. Metal oxide nanomaterials for electrochemical detection of heavy metals in water. In Nanostructured Metal-Oxide Electrode Materials for Water Purification: Fabrication, Electrochemistry and Applications; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2020; pp. 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodkhe, G.A.; Hedau, B.S.; Deshmukh, M.A.; Patil, H.K.; Shirsat, S.M.; Phase, D.M.; Pandey, K.K.; Shirsat, M.D. Selective and sensitive detection of Pb(II) ions using Au/SWNT nanocomposite-embedded MOF-199. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, M.A.; Bodkhe, G.A.; Shirsat, S.; Ramanavicius, A.; Shirsat, M.D. Nanocomposite platform based on EDTA-modified polypyrrole/SWNTs for electrochemical sensing of Pb(II) ions. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deshmukh, M.A.; Celiesiute, R.; Ramanaviciene, A.; Shirsat, M.D.; Ramanavicius, A. EDTA–PANI/SWCNT nanocomposite modified electrode for electrochemical determination of Cu(II), Pb(II), and Hg(II) ions. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 259, 930–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, N.C.; Gururani, P. Advances of graphene oxide based nanocomposite materials in the treatment of wastewater containing heavy metal ions and dyes. Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem. 2022, 5, 100306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlou, G.G.; Nkosi, D.; Pillay, K.; Arotiba, O. Electrochemical detection of Hg(II) in water using self-assembled single walled carbon nanotube-poly(m-amino benzene sulfonic acid) on gold electrode. Sens. Bio-Sens. Res. 2016, 10, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Shi, G.; Peng, C.; Ding, Y. Thiacalixarene covalently functionalized multiwalled carbon nanotubes as chemically modified electrode material for detection of ultratrace Pb2+ ions. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 10560–10567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Cao, D.; Feng, X. Research progress on graphene-based electrochemical biosensors. J. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 38, 503–517. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, H.N.; Peng, B.; Xue, Y.; Wu, Q.Y.; Sun, L.; Chi, D.F.; Z, N. Detection of heavy metals by graphene-modified enzyme liposome biosensor. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 2021, 42, 247–251. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Zang, F. Preparation of nitrogen-doped graphene and its application in heavy metal ions detection. J. Qingdao Univ. Sci. Technol. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2021, 426, 28–34. [Google Scholar]

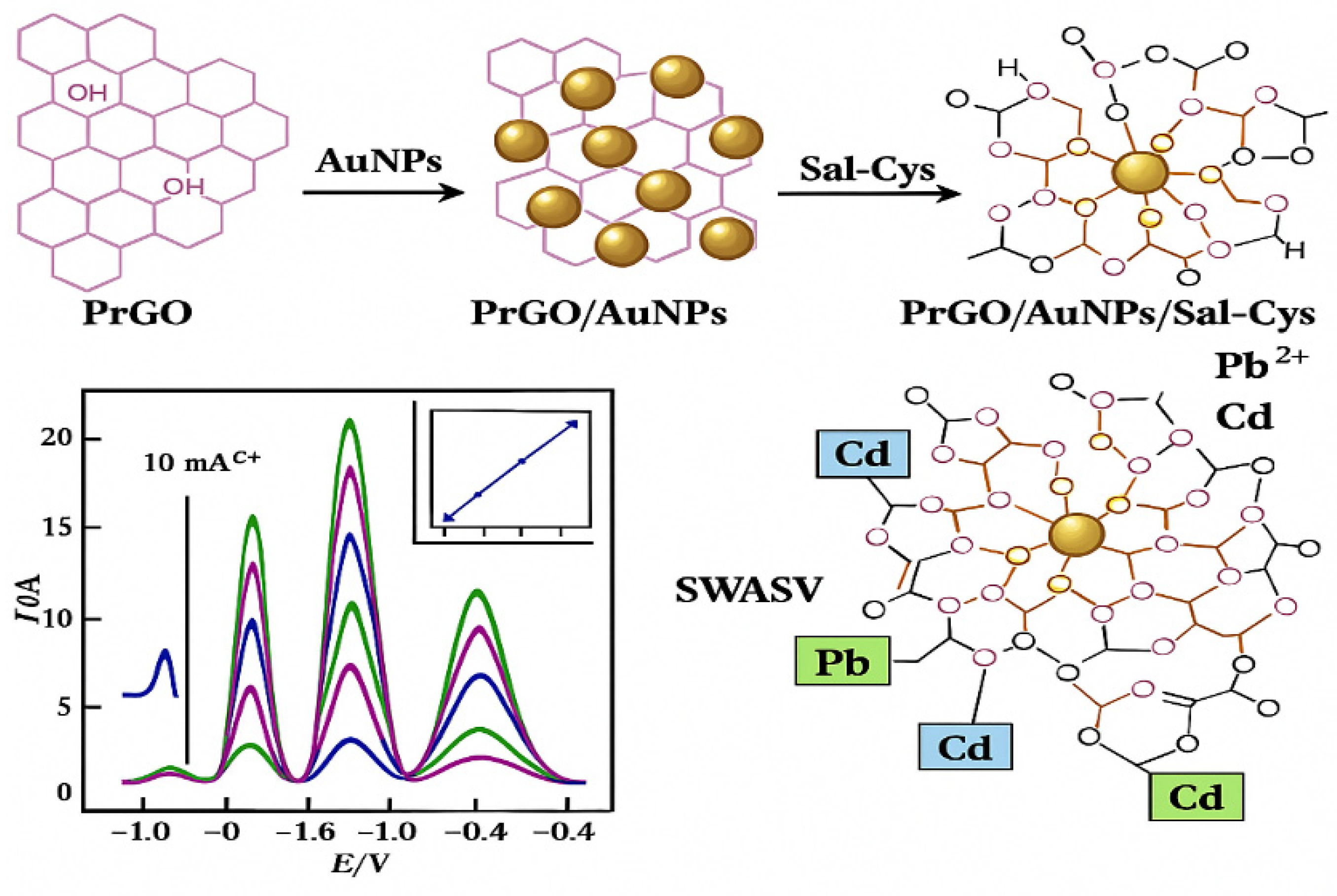

- Priya, T.; Dhanalakshmi, N.; Thennarasu, S.; Karthikeyan, V.; Thinakaran, N. Ultra sensitive electrochemical detection of Cd2+ and Pb2+ using penetrable nature of graphene/gold nanoparticles/modified L-cysteine nanocomposite. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2019, 731, 136621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Pan, Z.; Xie, Y.; Gu, X.; Liu, J. Electrochemical detection of heavy metals and chloramphenicol using Nafion/graphene quantum dot-modified electrodes. J. Anal. Sci. 2019, 35, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherigara, B.; Kutner, W.; D’Souza, F. Electrocatalytic properties and sensor applications of fullerenes and carbon nanotubes. Electroanalysis 2010, 15, 753–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.J.; Meng, Z.C.; Zhang, H.F. Fullerene-based anodic stripping voltammetry for simultaneous determination of Hg(II), Cu(II), Pb(II) and Cd(II) in foodstuff. Mikrochim. Acta 2018, 185, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, H. Research progress on metal-organic framework materials in liquid-phase catalytic hydrogen production. J. High. Educ. Chem. 2022, 43, 70–83. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, K.; Chen, X.D.; Chen, J.Y.; Li, Y. Development of MOF-derived carbon-based nanomaterials for efficient catalysis. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 5887–5903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.X.; Liu, W.W.; Cheng, N.C.; Banis, M.N.; Li, X.; Sun, Q.; Xiao, B.; Liu, Y.; Lushington, A.; Li, R.; et al. Origin of the high oxygen reduction reaction of nitrogen and sulfur co-doped MOF-derived nanocarbon electrocatalyst. Mater. Horiz. 2017, 4, 900–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, R.N.; Jiang, P.P.; Pan, C.C.; Pan, J.; Gao, N.; Cai, Z.; Wu, F.; Chang, G.; Xie, A.; He, Y. Core-shell architectured NH2-UiO-66@ZIF-8/multi-walled carbon nanotubes nanocomposite-based sensitive electrochemical sensor towards simultaneous determination of Pb2+ and Cu2+. Microchim. Acta 2022, 190, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, K.H.; Kwon, E.E. Biochar as a catalyst. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 77, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Mei, J.; Liu, G.; Kou, Q.; Yi, T.-F.; Xiao, S. Nitrogen-doped hierarchical porous carbon from wheat straw for supercapacitors. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 11595–11605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andres, B.A.; Childs, B.R.; Vallier, H.A. Treatment of hypovitaminosis D in an orthopaedic trauma population. J. Orthop. Trauma 2018, 32, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, J.; Yu, J.; Meng, B.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, W.; Fang, Z. Hierarchical porous biomass activated carbon for hybrid battery capacitors derived from persimmon branches. Mater. Express 2020, 10, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Senthil, R.A.; Pan, J.; Osman, S.; Sun, Y.; Shu, X. A new biomass derived rod-like porous carbon from tea-waste as inexpensive and sustainable energy material for advanced supercapacitor application. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 335, 135588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.M.; Huang, Q.B.; Lu, J.J.; Niu, J. Green synthesis of high-performance supercapacitor electrode materials from agricultural corncob waste by mild potassium hydroxide soaking and a one-step carbonization. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 161, 113215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdemir, M. Electrochemical performance of Quercus infectoria as a supercapacitor carbon electrode material. Int. J. Energy Res. 2022, 46, 7722–7731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.P.; Chen, C.; Wang, H.; Li, P.; Jiang, X.; Yang, J.; Liu, J. Hierarchical porous carbon induced by inherent structure of eggplant as sustainable electrode material for high performance supercapacitor. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 17, 1540–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punon, M.; Jarernboon, W.; Laokul, P. Electrochemical performance of Palmyra palm shell activated carbon prepared by carbonization followed by microwave reflux treatment. Mater. Res. Express 2022, 9, 065603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Ma, S.; Pan, Y.; Guan, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, H.; Du, M. Honeycomb-like carbon materials derived from pomelo peels for the simultaneous detection of heavy metal ions. Chin. J. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 35, 674–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naguib, M.; Kurtoglu, M.; Presser, V.; Lu, J.; Niu, J.; Heon, M.; Barsoum, M.W. Two-dimensional nanocrystals produced by exfoliation of Ti3AlC2. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 4207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, L.A.; Bashir, A.; Qureashi, A.; Pandith, A.H. Detection and removal of heavy metal ions: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2019, 17, 1495–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lu, J.; Hocevar, S.B.; Farias, P.A.M.; Ogorevc, B. Bismuth-coated carbon electrodes for anodic stripping voltammetry. Anal. Chem. 2000, 72, 3218–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deore, K.B.; Patil, S.S.; Narwade, V.N.; Takte, M.A.; Khune, A.S.; Mohammed, H.Y.; Farea, M.; Sayyad, P.W.; Tsai, M.-L.; Shirsat, M.D. Chromium-benzenedicarboxylates metal organic framework for supersensitive and selective electrochemical sensor of Toxic Cd2+, Pb2+, and Hg2+ metal ions: Study of their interactive mechanism. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2023, 170, 046505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Chen, T.; Liu, X.; Ma, H. Ultrasensitive and simultaneous detection of heavy metal ions based on three-dimensional graphene–carbon nanotube hybrid electrode materials. Anal. Chim. Acta 2014, 852, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, F.; Tong, C.; Wang, Z.; Han, H.; Liu, P.; Pan, D.; Zhu, R. Nanocomposite based on graphene and intercalated covalent organic frameworks with hydrosulphonyl groups for electrochemical determination of heavy metal ions. Microchim. Acta 2021, 188, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, G.; Yu, Z.; Tong, P.; Tang, D. Ti3C2 MXene quantum dot–encapsulated liposomes for photothermal immunoassays using a portable near-infrared imaging camera on a smartphone. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 15659–15667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Zhao, P.; Hu, Z.; Liang, Y.; Han, H.; Yang, M.; Luo, X.; Hou, C.; Huo, D. Amino-functionalized multilayer Ti3C2Tx enabled electrochemical sensor for simultaneous determination of Cd2+ and Pb2+ in food samples. Food Chem. 2023, 402, 134269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Li, Z.; Zhai, C.; Zeng, L.; Zhu, M. Photo-assisted simultaneous electrochemical detection of multiple heavy metal ions with a metal-free carbon black anchored graphitic carbon nitride sensor. Anal. Chim. Acta 2021, 1183, 338951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celiesiute, R.; Ramanaviciene, A.; Gicevicius, M.; Ramanavicius, A. Electrochromic sensors based on conducting polymers, metal oxides, and coordination complexes. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2019, 49, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaraj, M.; Sasikumar, Y.; Rajendran, S.; Ponce, L.C. Metal–organic framework based nanomaterials for electrochemical sensing of toxic heavy metal ions: Progress and prospects. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2021, 168, 037513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.B.; Nga, D.T.N.; Thu, V.T.; Piro, B.; Truong, T.N.P.; Yen, P.T.H.; Le, G.H.; Hung, L.Q.; Vu, T.A.; Ha, V.T.T. Novel nanoscale Yb-MOF used as a highly efficient electrode for simultaneous detection of heavy metal ions. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56, 8172–8185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Qi, Y.; Shen, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, C.; Sun, Y. A ratiometric electrochemical sensor for simultaneous detection of multiple heavy metal ions based on ferrocene-functionalized metal–organic framework. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 310, 127756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Oh, J.; Kim, D.; Piao, Y. A sensitive electrochemical sensor using an iron oxide/graphene composite for detection of heavy metal ions. Talanta 2016, 160, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhabeb, M.; Maleski, K.; Anasori, B.; Lelyukh, P.; Clark, L.; Sin, S.; Gogotsi, Y. Guidelines for synthesis and processing of two-dimensional titanium carbide (Ti3C3Tx MXene). Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 7633–7644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyad, P.W.; Ingle, N.N.; Al-Gahouari, T.; Mahadik, M.M.; Bodkhe, G.A.; Shirsat, S.M.; Shirsat, M.D. Sensitive and selective detection of Cu2+ and Pb2+ ions using FET based on L-cysteine anchored PEDOT:PSS/rGO composite. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2020, 761, 138056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyad, P.W.; Ingle, N.N.; Al-Gahouari, T.; Mahadik, M.M.; Bodkhe, G.A.; Shirsat, S.M.; Shirsat, M.D. Selective Hg2+ sensor based on rGO-blended PEDOT:PSS conducting polymer OFET. Appl. Phys. A 2021, 127, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotolan, N.; Mureșan, L.M.; Salis, A.; Barbu-Tudoran, L.; Turdean, G.L. Electrochemical detection of lead ions with ordered mesoporous silica–modified glassy carbon electrodes. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2020, 231, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Wang, H.; Urbankowski, P.; Gogotsi, Y. Topochemical synthesis of 2D materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 8744–8765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghidiu, M.; Lukatskaya, M.R.; Zhao, M.Q.; Gogotsi, Y.; Barsoum, M.W. Conductive two-dimensional titanium carbide ‘clay’ with high volumetric capacitance. Nature 2014, 516, 78–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, G.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, J.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Q.; Fernandez, C.; Peng, Q. Synthesis of MXene/Ag composites for extraordinary long cycle lifetime lithium storage at high rates. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 22280–22286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, N.; Zhou, Z. Adsorptive environmental applications of MXene nanomaterials: A review. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 19895–19905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Savchenkov, A.A.; Dale, E.; Liang, W.; Eliyahu, D.; Ilchenko, V.; Matsko, A.B.; Maleki, L.; Wong, C.W. Chasing the thermodynamical noise limit in whispering-gallery-mode resonators for ultrastable laser frequency stabilization. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasool, K.; Helal, M.; Ali, A.; Ren, C.E.; Gogotsi, Y.; Mahmoud, K.A. Antibacterial activity of Ti3C2TX Mxene. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 3674–3684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Ma, L.; Zhou, L.Y.; Liu, G.; Jiang, Y.; Gao, J. Preparation and application of bismuth/MXene nano-composite as electrochemical sensor for heavy metal ions detection. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, F.; Li, J.; He, Y.; Zheng, X.; Dai, Z.; Ma, S. Comparison of three LOD determination approaches in TLC. Chin. Pharm. 2019, 18, 1515–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. Gas chromatography validation of detection limits and quantification limits for petroleum hydrocarbons (C10–C40) in soil. Coal Chem. Ind. 2022, 45, 139–143. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, C.; Zhu, H.; Wang, Y.; Wu, M.; Ding, W.; Liu, S.; Zhao, H. Study on the effect of physical grinding on the performance of glassy carbon electrode. Guangzhou Chem. Ind. 2020, 48, 73–76. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Cui, J.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Pei, Y. Direct electrodeposition of carbon dots modifying bismuth film electrode for sensitive detection of Cd2+ and Pb2+. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2022, 169, 017501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pha, S.; Nguyên, H.; Berisha, A.; Tesfalidet, S. In situ Bi/carboxyphenyl-modified glassy carbon electrode as a sensor platform for detection of Cd2+ and Pb2+ using square wave anodic stripping voltammetry. Sens. Bio-Sens. Res. 2021, 34, 100455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhateria, R.; Jain, D. Water quality assessment of lake water: A review. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2016, 2, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Bi, H.; Han, X. Advances in the electrochemical detection of heavy metal ions. Anal. Chem. 2021, 49, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wygant, B.R.; Lambert, T.N. Thin film electrodes for anodic stripping voltammetry: A mini review. Front. Chem. 2022, 9, 809535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arduini, F.; Calvo, J.Q.; Palleschi, G.; Moscone, D.; Amine, A. Bismuth-modified electrodes for lead detection. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2010, 29, 1295–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, C.; Bayraktepe, D.E.; Yazan, Z.; Önal, M. Bismuth nanoparticles decorated on Na-montmorillonite multiwall carbon nanotube for simultaneous determination of heavy metal ions-electrochemical methods. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2022, 910, 116205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, G.; Nguyen, T.D.; Piro, B. Modified electrodes used for electrochemical detection of metal ions in environmental analysis. Biosensors 2015, 5, 241–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legeai, S.; Vittori, O.A. Cu/Nafion/Bi electrode for on-site monitoring of trace heavy metals in natural waters using anodic stripping voltammetry: An alternative to mercury-based electrodes. Anal. Chim. Acta 2006, 560, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Lin, Y.; Tu, Y.; Ren, Z. Ultrasensitive voltammetric detection of trace heavy metal ions using carbon nanotube nanoelectrode array. Analyst 2005, 130, 1098–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lu, J.; Ülkü, A.; Hocevar, S.B.; Ogorevc, B. Insights into the anodic stripping voltammetric behavior of bismuth film electrodes. Anal. Chim. Acta 2001, 434, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sb, H.; Ogorevc, B.; Wang, J.; Pihlar, B. A study on operational parameters for advanced use of bismuth film electrode in anodic stripping voltammetry. Electroanalysis 2002, 14, 1701–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buledi, J.A.; Amin, S.; Haider, S.I.; Bhanger, M.I.; Solangi, A.R. A review on detection of heavy metals from aqueous media using nanomaterial-based sensors. Environment. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 58994–59002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumunda, C.; Adekunle, A.S.; Mamba, B.B.; Hlongwa, N.W.; Nkambule, T.T. Electrochemical detection of environmental pollutants based on graphene derivatives: A review. Front. Mater. 2021, 7, 616787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrotra, P. Biosensors and their applications—A review. J. Oral Biol. Craniofac. Res. 2016, 6, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Qin, Y.; Xu, C.; Wei, Y.; Yang, R.; Wang, Z.L. Self-powered nanowire devices. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2010, 5, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cracknell, J.A.; Vincent, K.A.; Armstrong, F.A. Enzymes as working or inspirational electrocatalysts for fuel cells and electrolysis. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 2439–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barton, S.C.; Gallaway, J.; Atanassov, P. Enzymatic biofuel cells for implantable and microscale devices. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 4867–4886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinquin, P.; Gondran, C.; Giroud, F.; Mazabrard, S.; Pellissier, A.; Boucher, F.; Alcaraz, J.-P.; Gorgy, K.; Lenouvel, F.; Mathé, S.; et al. A glucose biofuel cell implanted in rats. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Chapter 3—Electrochemical glucose biosensors. Electrochem. Sens. Biosens. Biomed. Appl. 2008, 108, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, L.; Tam, T.K.; Pita, M.; Meijler, M.M.; Alfonta, L.; Katz, E. Biofuel cell controlled by enzyme logic systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 826–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grattieri, M.; Minteer, S.D. Self-powered biosensors. ACS Sens. 2017, 2, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, P.; Yang, M.J.; Wang, Z.W.; Li, X.; Miao, R.; Compton, R.G. Single-entity Ti3C2TX MXene electro-oxidation. Appl. Mater. Today 2022, 26, 101335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djebbi, M.A.; Allagui, L.; Ayachi, M.S.E.; Boubakri, S.; Jaffrezic-Renault, N.; Namour, P.; Amara, A.B.H. Zero-valent iron nanoparticles supported on biomass-derived porous carbon for simultaneous detection of Cd2+ and Pb2+. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 546–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, X.B.; Wang, J.; Qin, Y.; Wang, T.; He, C.; Shao, Q.; Zhu, H.W.; Cao, N. Enhancing capacitance performance of Ti3C2Tx MXene as electrode materials of supercapacitor: From controlled preparation to composite structure construction. Nano-Micro Lett. 2020, 12, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthy, R.; Yu, X.C.; Zhu, P.L.; Hu, Y.; Sun, R.; Wong, C. Exfoliation and defect control of two-dimensional few-layer MXene Ti3C2TX for electromagnetic interference shielding coatings. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 49737–49747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komkova, M.A.; Pasquarelli, A.; Andreev, E.A.; Galushin, A.A.; Karyakin, A.A. Prussian blue modified boron-doped diamond interfaces for advanced H2O2 electrochemical sensors. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 339, 135924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubino, A.; Queirós, R. Electrochemical determination of heavy metal ions applying screen-printed electrodes based sensors. A review on water and environmental samples analysis. Talanta 2023, 7, 100203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Metal | LOD (µg/L) | MDL (µg/L) | WHO Limit (µg/L) | EPA Limit (µg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pb2+ | 0.405 | 0.424 | 10 | 15 |

| Cd2+ | 0.565 | 0.592 | 3 | 5 |

| Hg2+ | 1–5 | — | 1 | 2 |

| Electrode | Technique | Metal | LOD | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bare GCE | DPV | Pb2+ | 0.405 µg/L | This work |

| Bare GCE | DPV | Cd2+ | 0.565 µg/L | This work |

| MXene/GOD-PB/ITO | Self-powered | Hg2+ | 1–5 µg/L | This work |

| Sb electrode | PSA | Pb2+ | 0.03 µg/L | Wei et al. [51] |

| Metal | Linear Range | Sensitivity | Repeatability (RSD %) | Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pb2+ | µg/L range | High | ≤5% | Good |

| Cd2+ | µg/L range | High | ≤6% | Good |

| Hg2+ | 1–5 µg/L | Moderate | ≤7% | Good |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mukatayeva, Z.; Konarbay, D.; Bakytkarim, Y.; Shadin, N.; Tileuberdi, Y. Analytical Determination of Heavy Metals in Water Using Carbon-Based Materials. Molecules 2026, 31, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010005

Mukatayeva Z, Konarbay D, Bakytkarim Y, Shadin N, Tileuberdi Y. Analytical Determination of Heavy Metals in Water Using Carbon-Based Materials. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleMukatayeva, Zhazira, Diana Konarbay, Yrysgul Bakytkarim, Nurgul Shadin, and Yerbol Tileuberdi. 2026. "Analytical Determination of Heavy Metals in Water Using Carbon-Based Materials" Molecules 31, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010005

APA StyleMukatayeva, Z., Konarbay, D., Bakytkarim, Y., Shadin, N., & Tileuberdi, Y. (2026). Analytical Determination of Heavy Metals in Water Using Carbon-Based Materials. Molecules, 31(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010005