Electron Scattering from NO2: Cross Sections in the Energy Range of 1–1000 eV

Abstract

1. Introduction

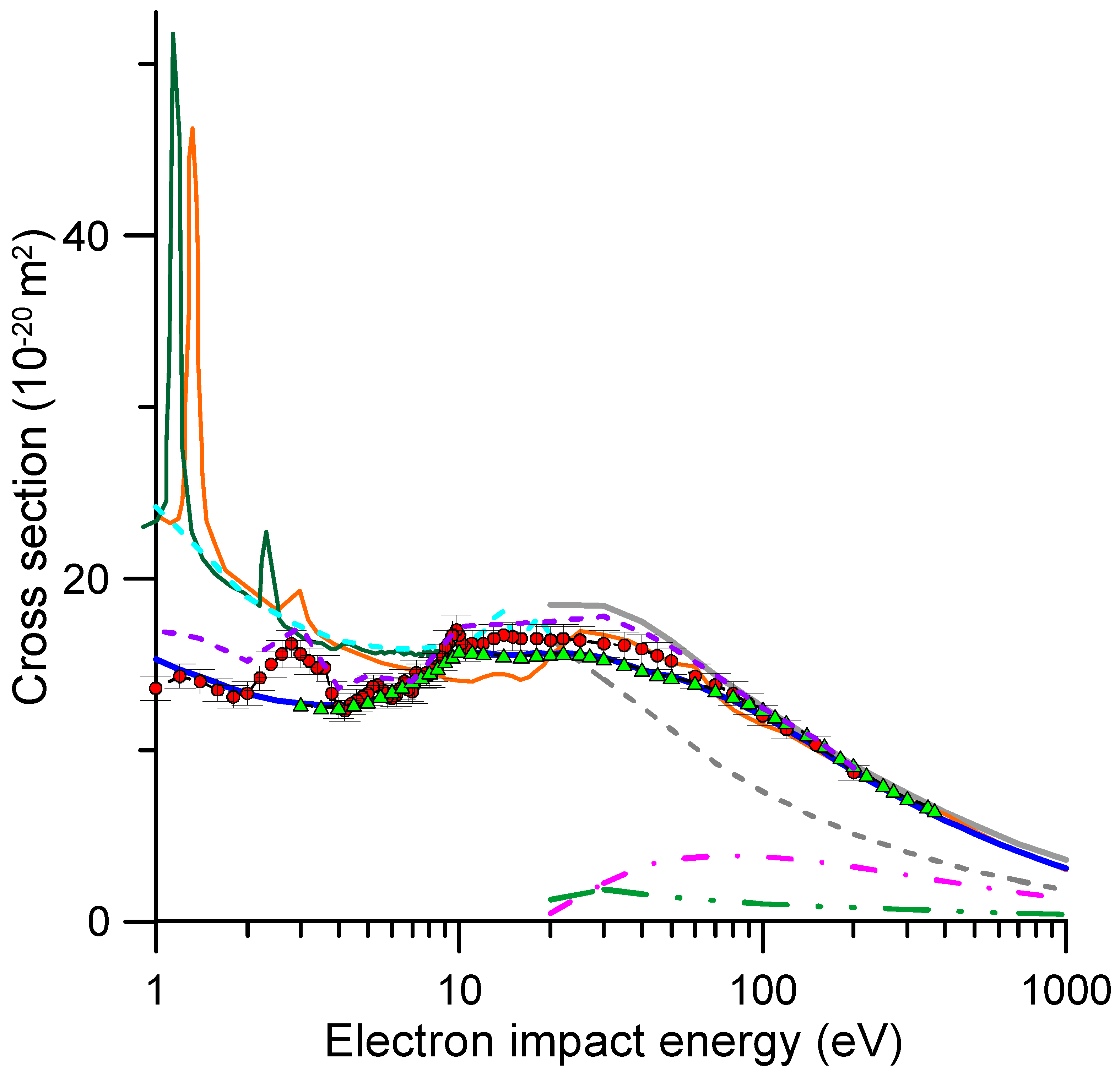

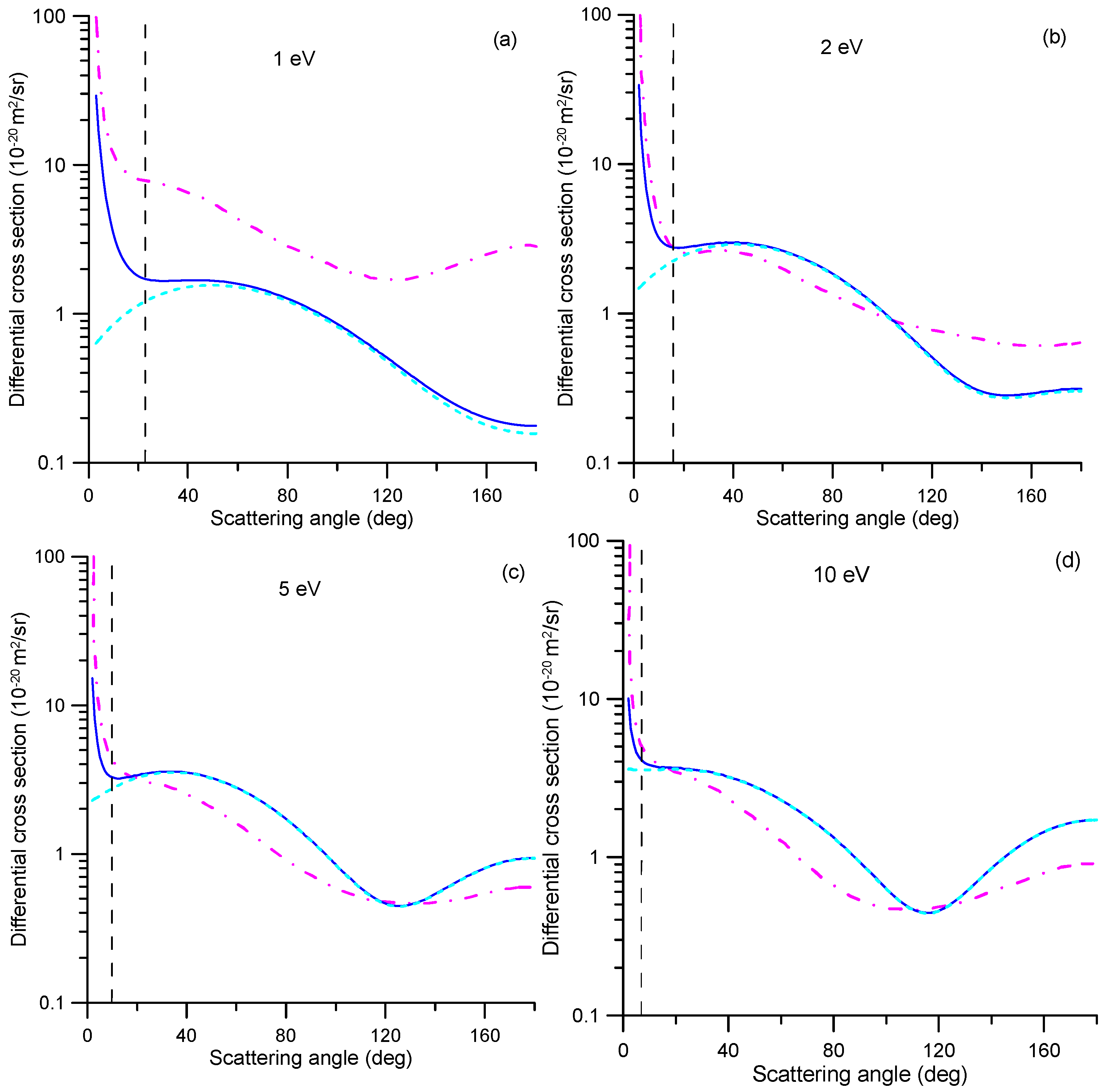

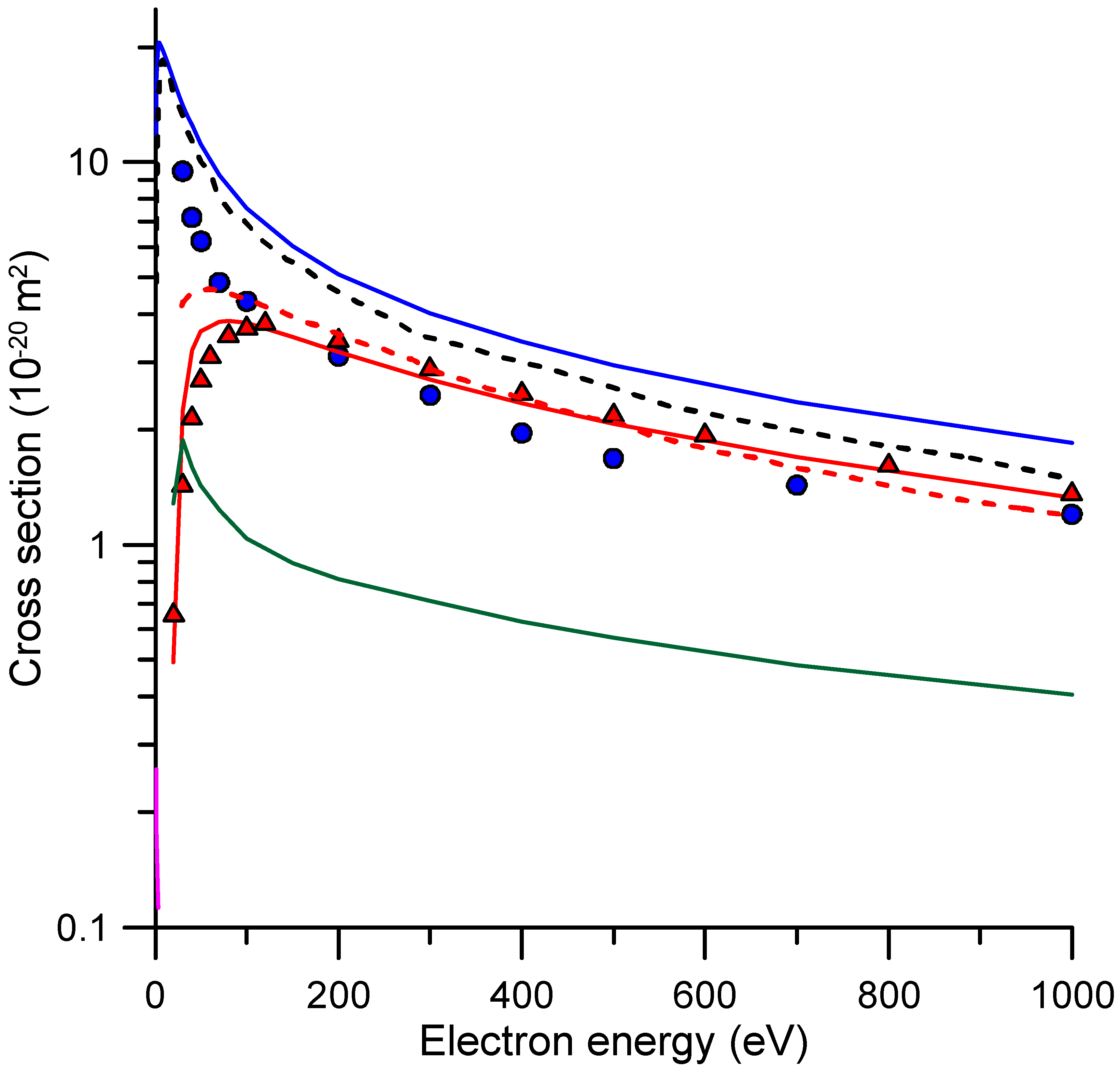

2. Results

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Experimental Methods

3.2. Theoretical Methods

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lorente, A.; Boersma, K.F.; Eskes, H.J.; Veefkind, J.P.; van Geffen, J.H.G.M.; de Zeeuw, M.B.; Denier van der Gon, H.A.C.; Beirle, S.; Krol, M.C. Quantification of Nitrogen Oxides Emissions from Build-up of Pollution over Paris with TROPOMI. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 20033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Zhu, Q.; Chen, C.; Liang, J.; Li, M.; Yang, Z.; Lin, K.; Han, C.; Liu, D.; Yang, J. Long-Term Exposure to PM2.5 Components and Mortality in 237 Chinese Cities: A Modelling Study. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2025, 19, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott Downen, R.; Dong, Q.; Chorvinsky, E.; Li, B.; Tran, N.; Jackson, J.H.; Pillai, D.K.; Zaghloul, M.; Li, Z. Personal NO2 Sensor Demonstrates Feasibility of In-Home Exposure Measurements for Pediatric Asthma Research and Management. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2022, 32, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, V.; Jacob, D.J.; Dang, R.; Lamsal, L.N.; Strode, S.A.; Steenrod, S.D.; Boersma, K.F.; Eastham, S.D.; Fritz, T.M.; Thompson, C.; et al. Nitrogen Oxides in the Free Troposphere: Implications for Tropospheric Oxidants and the Interpretation of Satellite NO2 Measurements. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2023, 23, 1227–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curik, R.; Gianturco, F.A.; Lucchese, R.R.; Sanna, N. Low-Energy Electron Scattering and Resonant States of NO2(2A1). J. Phys. B At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 2001, 34, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, R.E. Negative Ion Formation in NO2 by Electron Attachment. J. Chem. Phys. 1960, 32, 285–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockdale, J.A.D.; Compton, R.N.; Hurst, G.S.; Reinhardt, P.W. Collisions of Monoenergetic Electrons with NO2: Possible Lower Limits to Electron Affinities of O2 and NO. J. Chem. Phys. 1969, 50, 2176–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rallis, D.A.; Goodings, J.M. Dissociative Electron Attachment Processes in SO2 and NO2. Can. J. Chem. 1971, 49, 1571–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouaf, R.; Paineau, R.; Fiquet-Fayard, F. Dissociative Attachment in NO2 and CO2. J. Phys. B At. Mol. Phys. 1976, 9, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangwala, S.A.; Krishnakumar, E.; Kumar, S.V.K. Dissociative-Electron-Attachment Cross Sections: A Comparative Study of NO2 and O3. Phys. Rev. A—At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 2003, 68, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, D.; Krishnakumar, E. Dissociative Electron Attachment to Polyatomic Molecules: Ion Kinetic Energy Measurements. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2010, 289, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Fan, M.; Tian, S.X. Dissociation Dynamics of Anionic Nitrogen Dioxide in the Low-Lying Resonant States. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2023, 14, 598–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munjal, H.; Baluja, K.L.; Tennyson, J. Electron Collisions with the NO2 Radical Using the R-Matrix Method. Phys. Rev. A 2009, 79, 032712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.; Naghma, R.; Vinodkumar, M.; Antony, B. Electron Scattering Studies of Nitrogen Dioxide. J. Electron Spectros. Relat. Phenomena 2013, 191, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Jiang, X.; Yuen, C.H.; Kokoouline, V.; Ayouz, M. Formation of Negative-Ion Resonance and Dissociative Attachment in Collisions of NO2 with Electrons. J. Phys. B 2021, 54, 185201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshipura, K.N.; Patel, P.M. Total Electron Scattering Cross Sections for NO, CO, NO2, N2O, CO2 and NH3 (Ei ≥ 50 EV). J. Phys. B At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 1996, 29, 3925–3932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshipura, K.N.; Gangopadhyay, S.; Vaishnav, B.G. Electron Scattering and Ionization of NO, N2O, NO2, NO3 and N2O5 Molecules: Theoretical Cross Sections. J. Phys. B At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 2007, 40, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zecca, A.; Nogueira, J.C.; Karwasz, G.P.; Brusa, R.S. Total Cross Sections for Electron Scattering on NO2, OCS, SO2 at Intermediate Energies. J. Phys. B At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 1995, 28, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Heng, S.; Jin-Feng, S.; Zun-Lue, Z.; Yu-Fang, L. A Modification Potential Method for Electron Scattering Total Cross Section Calculations on Several Molecules at 30–5000eV. Chin. Phys. 2005, 14, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin-Feng, S.; Bin, X.; Yu-Fang, L.; De-Heng, S. Total Cross Sections for Electron Scattering on Polyatomic Molecules (CH4, CO2, NO2, and N2O) at 10∼3000 EV. Commun. Theor. Phys. 2005, 43, 895–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumer, T.; Shorifuddoza, M.; Das, P.K.; Watabe, H.; Shahmohammadi Beni, M.; Haque, A.K.F.; Uddin, M.A. Scattering of Electrons and Positrons by Nitrogen Dioxide. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2025, 125, e27475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmytkowski, C.; Macia̧g, K.; Krzysztofowicz, A.M. NO2 Total Absolute Electron-Scattering Cross Sections. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1992, 190, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmytkowski, C.; Mozejko, P. Electron-Scattering Total Cross Sections for Triatomic Molecules: NO2 and H2O. Opt. Appl. 2006, 36, 543–550. [Google Scholar]

- Zecca, A.; Karwasz, G.P.; Brusa, R.S.; Wróblewski, T. Low-Energy Electron Collisions in Nitrogen Oxides: A Comparative Study. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2003, 223–224, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, J.; Tarnovsky, V.; Gutkin, M.; Becker, K. Electron-Impact Ionization of NO, NO2, and N2O. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2003, 225, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, C.Q.; DeJoseph, C.A.; Garscadden, A. Absolute Cross Sections for Electron Impact Ionization of NO2. J. Chem. Phys. 2002, 117, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukić, D.; Josifov, G.; Kurepa, M.V. Total Electron-Ionization Cross Sections of the NO2 Molecule. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2001, 205, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, B.G.; Mangan, M.A.; Straub, H.C.; Stebbings, R.F. Absolute Partial Cross Sections for Electron-Impact Ionization of NO and NO2 from Threshold to 1000 EV. J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 112, 9404–9410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antony, B.K.; Joshipura, K.N.; Mason, N.J. Electron Impact Ionization Studies with Aeronomic Molecules. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2004, 233, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-K.; Hwang, W.; Weinberger, N.M.; Ali, M.A.; Rudd, M.E. Electron-Impact Ionization Cross Sections of Atmospheric Molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1997, 106, 1026–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karwasz, G.P.; Brusa, R.S.; Zecca, A. One Century of Experiments on Electron-Atom and Molecule Scattering: A Critical Review of Integral Cross-Sections. Riv. Nuovo Cim. 2001, 24, 1–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.-Y.; Yoon, J.-S.; Cho, H.; Karwasz, G.P.; Kokoouline, V.; Nakamura, Y.; Tennyson, J. Cross Sections for Electron Collisions with NO, N2O, and NO2. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 2019, 48, 043104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, F.; García, G. Screening Corrections for Calculation of Electron Scattering Differential Cross Sections from Polyatomic Molecules. Phys. Lett. A 2004, 330, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, F.; Ellis-Gibbings, L.; García, G. Screening Corrections for the Interference Contributions to the Electron and Positron Scattering Cross Sections from Polyatomic Molecules. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2016, 645, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanna, N.; Giantirco, F.A. Differential cross sections for electron/positron scattering from polyatomic molecules. Comput. Phys. Commun. 1998, 14, 142–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, A.I.; Oller, J.C.; Krupa, K.; Ferreira da Silva, F.; Limão-Vieira, P.; Blanco, F.; Muñoz, A.; Colmenares, R.; García, G. Magnetically Confined Electron Beam System for High Resolution Electron Transmission-Beam Experiments. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2018, 89, 063105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, A.G.; Fuss, M.C.; Blanco, F.; Sebastianelli, F.; Gianturco, F.A.; García, G. Electron scattering cross sections from HCN over a broad energy range (0.1–10000 eV): Influence of the permanent dipole moment on the scattering process. J. Chem Phys. 2012, 137, 124103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgeson, J.A.; Sibert, E.E.; Curl, R.F. Dipole Moment of Nitrogen Dioxide1a. J. Phys. Chem. 1963, 67, 2833–2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, A.I.; Rosado, J.; Blanco, F.; Limão-Vieira, P.; García, G. Integral Electron Scattering Cross Sections from N2O for Impact Energies Ranging from 1 to 1000 EV. J. Phys. Chem. A 2024, 128, 699–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Abenza, A.; Lozano, A.I.; Álvarez, L.; Oller, J.C.; Blanco, F.; Stokes, P.; White, R.D.; de Urquijo, J.; Limão-Vieira, P.; Jones, D.B.; et al. A Complete Data Set for the Simulation of Electron Transport through Gaseous Tetrahydrofuran in the Energy Range 1–100 EV. Eur. Phys. J. D 2021, 75, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| E (eV) | TCSexp | Δθ | σ(Δθ) | E (eV) | TCSexp | Δθ | σ(Δθ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | 13.6 | 22.8 | 3.4 | 8.0 | 14.4 | 7.9 | |

| 1.2 | 14.3 | 20.7 | 8.2 | 14.7 | 7.8 | ||

| 1.4 | 14.4 | 19.1 | 2.5 | 8.5 | 14.9 | 7.6 | |

| 1.6 | 13.5 | 17.8 | 8.8 | 15.4 | 7.5 | ||

| 1.8 | 13.1 | 16.8 | 9.0 | 16.0 | 7.4 | ||

| 2.0 | 13.3 | 15.9 | 1.9 | 9.2 | 16.2 | 7.3 | |

| 2.2 | 14.2 | 15.1 | 9.5 | 16.7 | 7.2 | ||

| 2.4 | 15.0 | 14.5 | 9.8 | 17.0 | 7.1 | ||

| 2.6 | 15.6 | 13.9 | 10.0 | 16.7 | 7.0 | 0.52 | |

| 2.8 | 16.2 | 13.4 | 10.2 | 16.2 | 6.9 | ||

| 3.0 | 15.6 | 12.9 | 1.6 | 10.5 | 16.0 | 6.9 | |

| 3.2 | 15.2 | 12.5 | 11.0 | 16.2 | 6.7 | ||

| 3.4 | 14.8 | 12.1 | 12.0 | 16.2 | 6.4 | ||

| 3.6 | 14.8 | 11.8 | 13.0 | 16.5 | 6.2 | ||

| 3.8 | 13.3 | 11.5 | 14.0 | 16.7 | 5.9 | ||

| 4.0 | 12.5 | 11.2 | 1.1 | 15.0 | 16.6 | 5.7 | 0.77 |

| 4.2 | 12.3 | 10.9 | 16.0 | 16.5 | 5.6 | ||

| 4.4 | 12.7 | 10.6 | 18.0 | 16.5 | 5.2 | ||

| 4.6 | 12.9 | 10.4 | 20.0 | 16.4 | 5.0 | 1.1 | |

| 4.8 | 13.1 | 10.2 | 22.0 | 16.5 | 5.5 | ||

| 5.0 | 13.3 | 10.0 | 1.0 | 25.0 | 16.4 | 5.1 | |

| 5.2 | 13.7 | 9.8 | 30.0 | 16.2 | 4.7 | 1.6 | |

| 5.4 | 13.8 | 9.6 | 35.0 | 16.1 | 4.3 | ||

| 5.6 | 13.5 | 9.4 | 40.0 | 15.9 | 4.0 | 1.0 | |

| 5.8 | 13.1 | 9.2 | 45.0 | 15.5 | 3.8 | ||

| 6.0 | 13.0 | 9.1 | 50.0 | 15.2 | 3.6 | 0.81 | |

| 6.2 | 13.2 | 8.9 | 60.0 | 14.3 | 3.3 | ||

| 6.4 | 13.6 | 8.8 | 70.0 | 13.8 | 3.1 | 0.58 | |

| 6.6 | 14.0 | 8.7 | 80.0 | 13.3 | 2.9 | ||

| 6.8 | 13.5 | 8.5 | 90.0 | 12.7 | 2.7 | ||

| 7.0 | 13.4 | 8.4 | 0.6 | 100 | 12.0 | 2.6 | 0.45 |

| 7.1 | 13.8 | 8.3 | 120 | 11.2 | 2.3 | ||

| 7.2 | 14.5 | 8.3 | 150 | 10.3 | 2.1 | 0.34 | |

| 7.5 | 14.3 | 8.1 | 200 | 8.7 | 1.8 | 0.27 | |

| 7.8 | 14.5 | 8.0 |

| E (eV) | Elastic | Ionization | EE | RE | TCS | TCS-MA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 16.5 | 0.49 | 1.28 | 0.26 | 18.5 | 17.4 |

| 30 | 14.1 | 2.24 | 1.88 | 0.18 | 18.4 | 16.8 |

| 40 | 12.5 | 3.22 | 1.60 | 0.14 | 17.5 | 16.4 |

| 50 | 11.2 | 3.61 | 1.43 | 0.11 | 16.3 | 15.6 |

| 70 | 9.24 | 3.84 | 1.23 | 0.08 | 14.39 | 13.8 |

| 100 | 7.59 | 3.81 | 1.04 | 0.06 | 12.5 | 12.1 |

| 150 | 6.05 | 3.50 | 0.90 | 0.04 | 10.5 | 10.2 |

| 200 | 5.10 | 3.19 | 0.81 | 0.03 | 9.1 | 8.8 |

| 300 | 4.03 | 2.70 | 0.71 | 0.02 | 7.5 | 7.3 |

| 400 | 3.39 | 2.34 | 0.63 | 0.02 | 6.4 | 6.2 |

| 500 | 2.94 | 2.07 | 0.57 | 0.01 | 5.6 | 5.5 |

| 700 | 2.36 | 1.69 | 0.48 | 0.01 | 4.5 | 4.4 |

| 1000 | 1.84 | 1.33 | 0.41 | 0.01 | 3.6 | 3.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lozano, A.I.; García-Abenza, A.; Rosado, J.; Blanco, F.; Oller, J.C.; Limão-Vieira, P.; García, G. Electron Scattering from NO2: Cross Sections in the Energy Range of 1–1000 eV. Molecules 2026, 31, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010006

Lozano AI, García-Abenza A, Rosado J, Blanco F, Oller JC, Limão-Vieira P, García G. Electron Scattering from NO2: Cross Sections in the Energy Range of 1–1000 eV. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleLozano, Ana I., Adrián García-Abenza, Jaime Rosado, Francisco Blanco, Juan C. Oller, Paulo Limão-Vieira, and Gustavo García. 2026. "Electron Scattering from NO2: Cross Sections in the Energy Range of 1–1000 eV" Molecules 31, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010006

APA StyleLozano, A. I., García-Abenza, A., Rosado, J., Blanco, F., Oller, J. C., Limão-Vieira, P., & García, G. (2026). Electron Scattering from NO2: Cross Sections in the Energy Range of 1–1000 eV. Molecules, 31(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010006