Toxicity of High-Density Polyethylene Nanoparticles in Combination with Silver Nanoparticles to Caco-2 and HT29MTX Cells Growing in 2D or 3D Culture

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

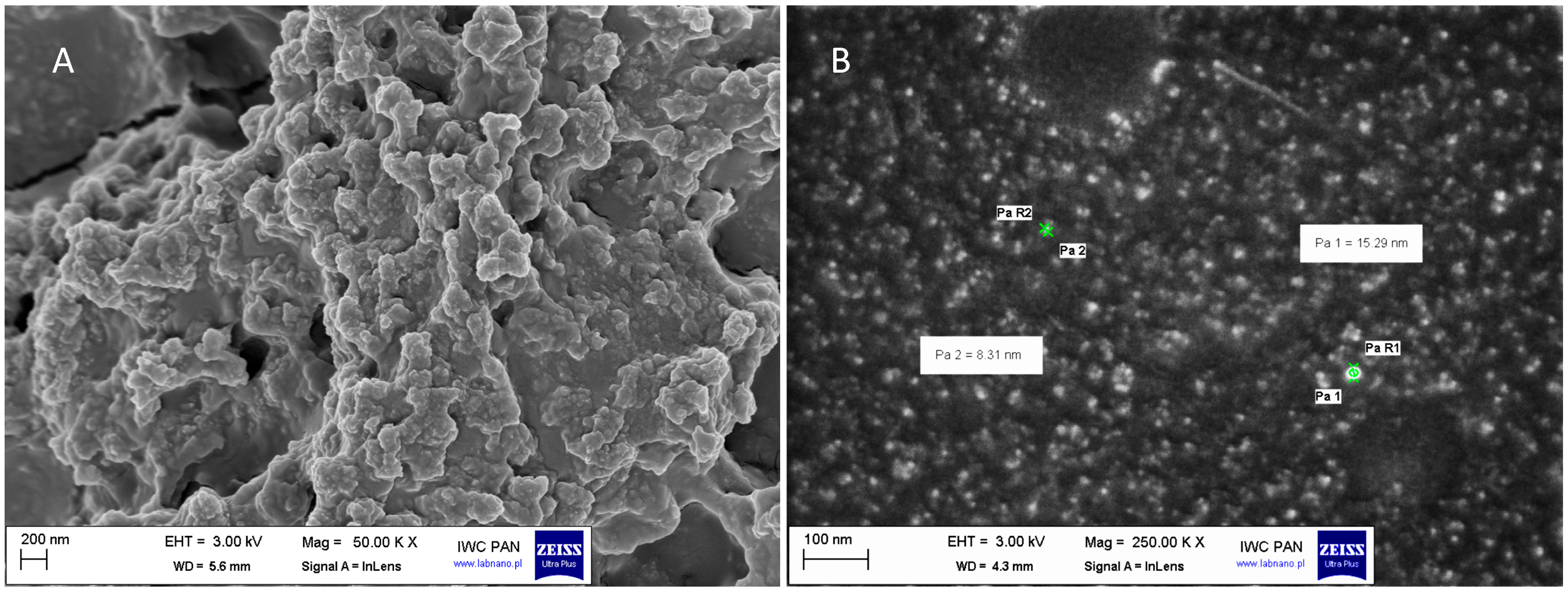

2.1. Characterisation of HDPE Particles

2.2. Characterisation of Ag Particles

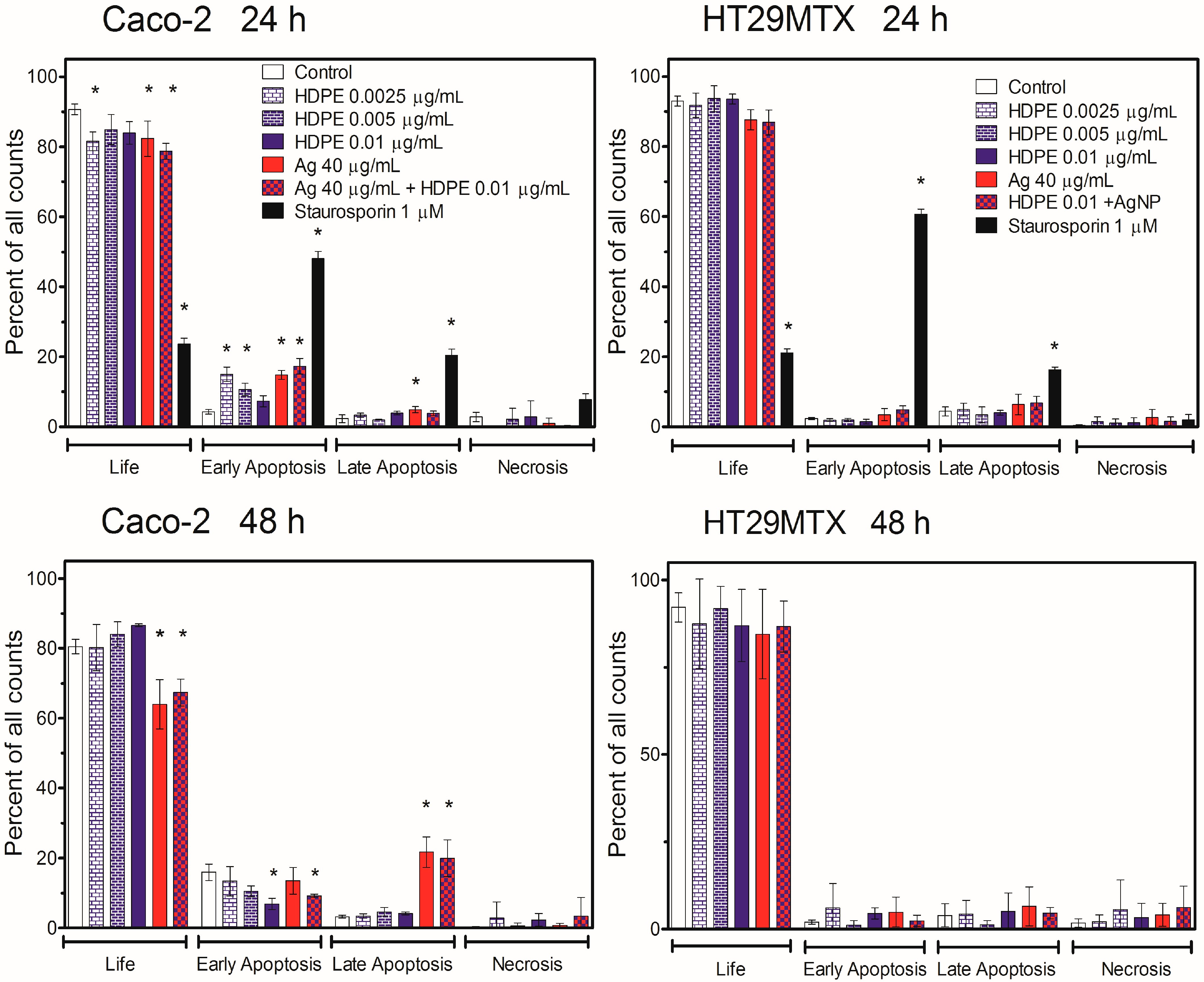

2.3. Endotoxin Content

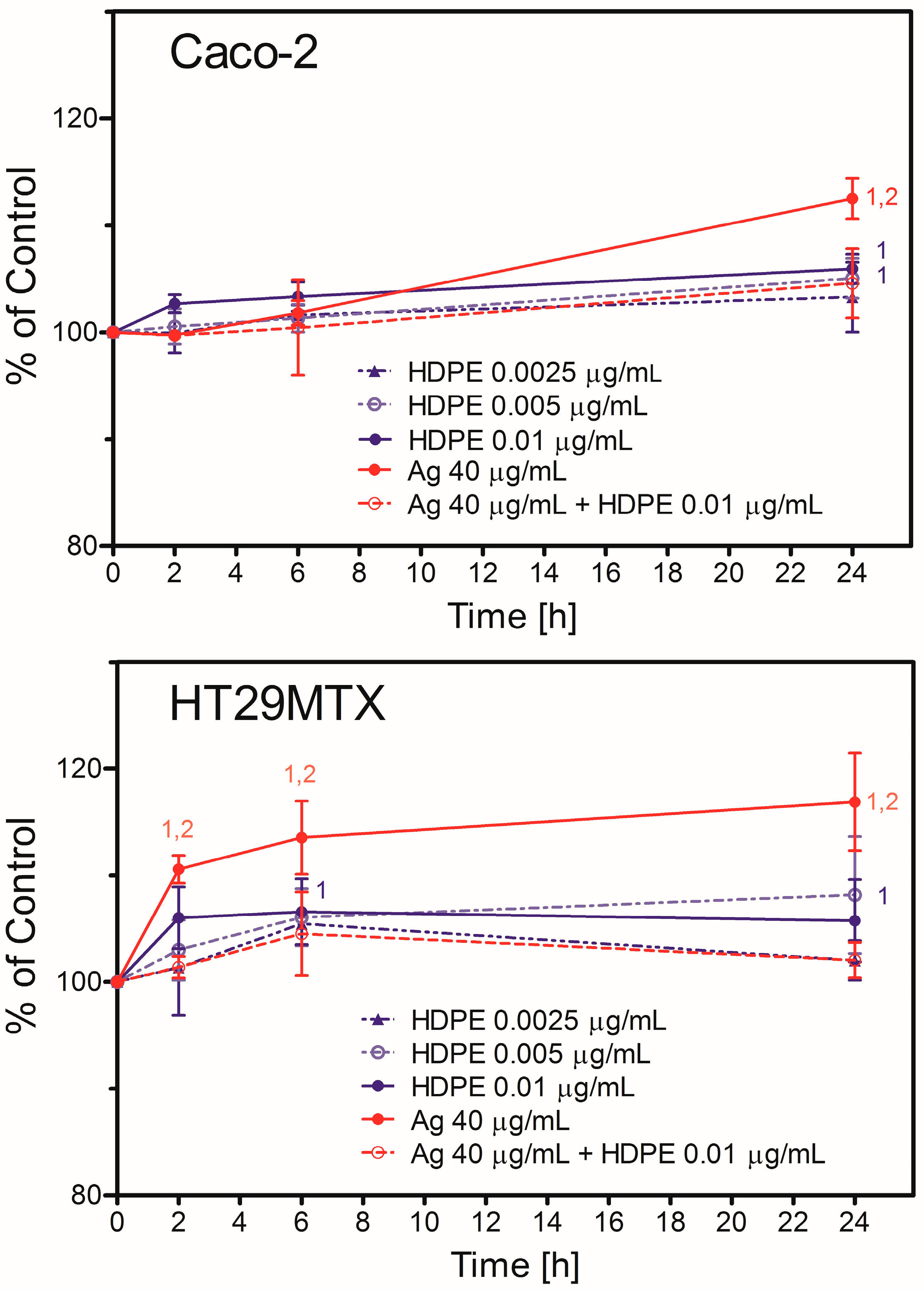

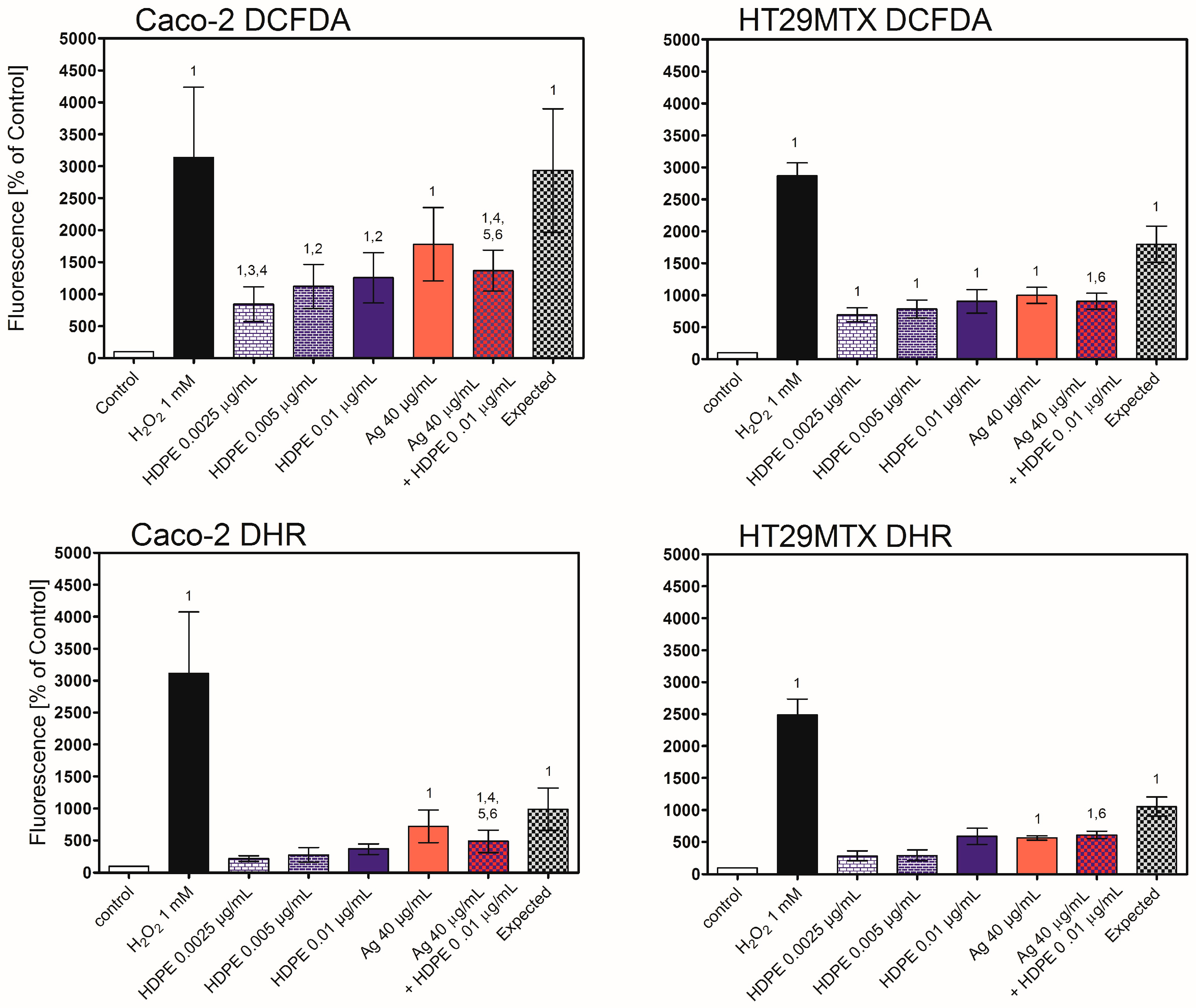

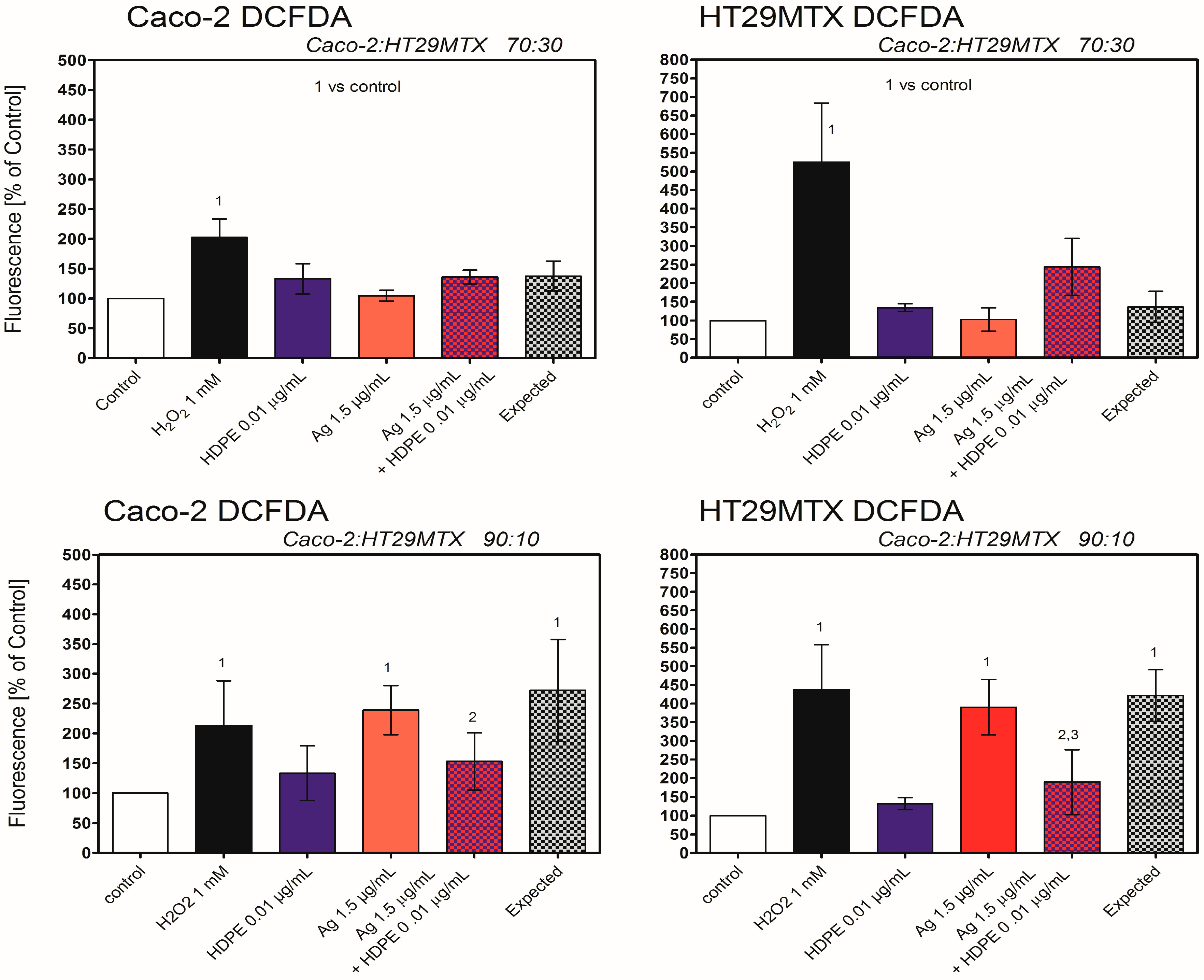

2.4. Nanoparticle Uptake by Caco-2 or HT29MTX Cells Growing in Monoculture

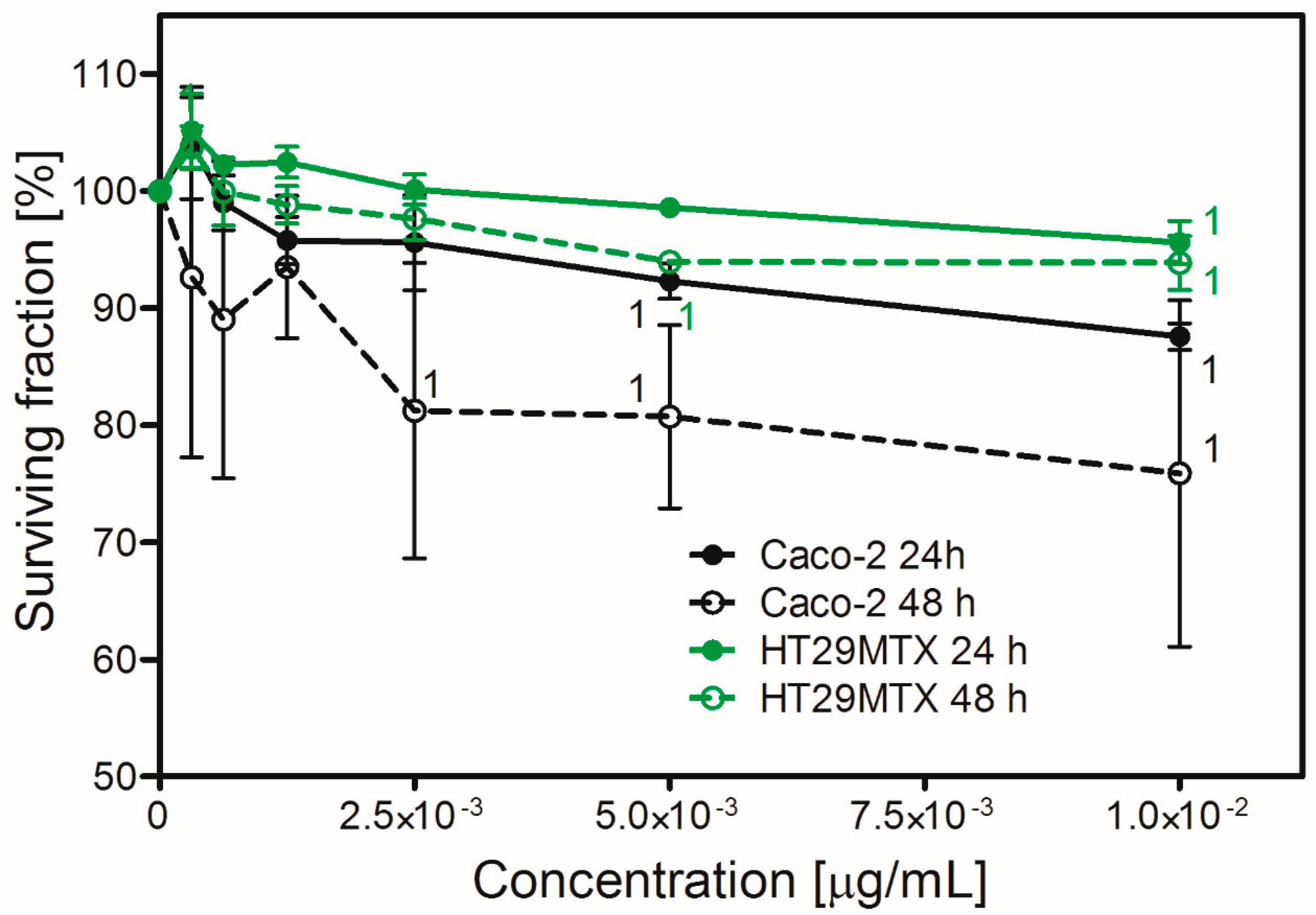

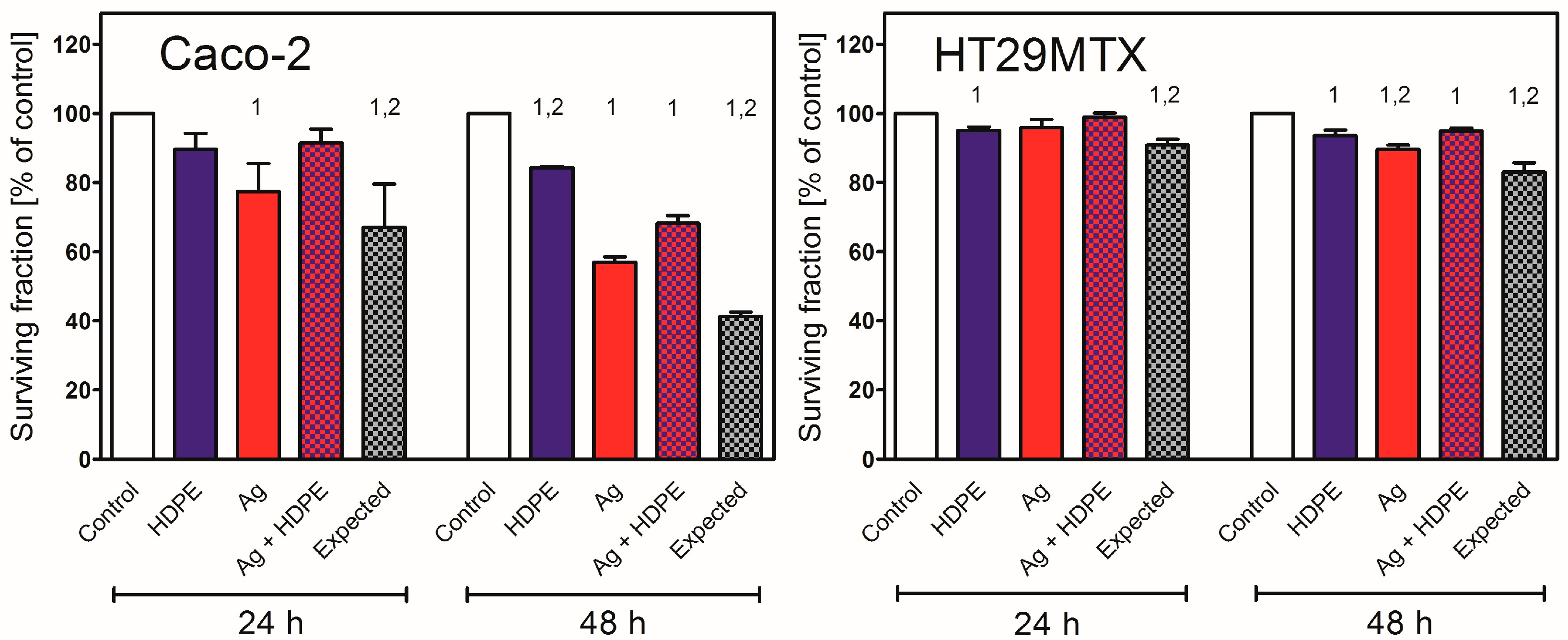

2.5. Nanoparticle Toxicity in Caco-2 or HT29MTX Cells Growing in Monoculture

2.6. Induction of Apoptosis in Caco-2 or HT29MTX Cells Growing in Monoculture or Triple-Culture Caco-2/HT29MTX/Raji

2.7. Oxidative Stress in Caco-2 or HT29MTX Cells Growing in Monoculture or Triple-Culture Caco-2/HT29MTX/Raji

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Nanoparticles

4.1.1. Silver Nanoparticles

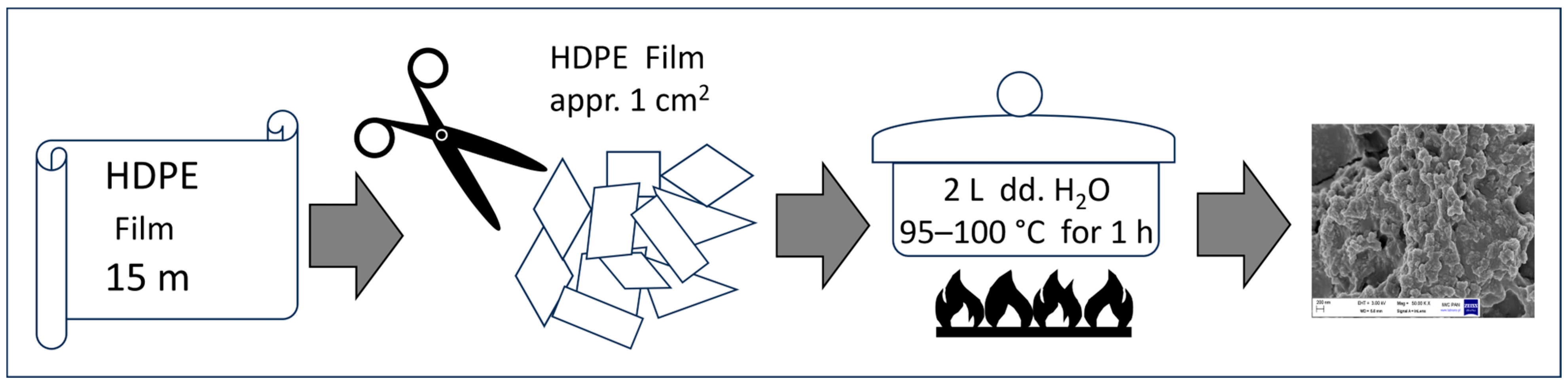

4.1.2. HDPE Nanoparticles

4.2. Nanoparticle Characterisation

4.2.1. High-Resolution Scanning Electron Microscopy (HR-SEM)

4.2.2. Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA)

4.2.3. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

4.2.4. Endotoxins

4.3. Cell Culture

4.4. Nanoparticle Uptake Analysis

4.5. Neutral Red Uptake (NRU) Assay

4.6. Apoptosis Detection by Annexin V-FITC/PI Staining in 2D Model and by Annexin V-FITC/Sytox Blue Staining in 3D Model

4.7. Intracellular Reactive Oxygen Species Measurement by Flow Cytometry

4.8. The Concept of Expected Value

4.9. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AgNPcit | Citrate-stabilised silver nanoparticles |

| PS NPs | Polystyrene nanoparticles |

| DLS | Dynamic light scattering |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| EMEM | Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium |

| EU | Endotoxin Unit |

| FBS | Foetal bovine serum |

| HDPE | High-density polyethylene |

| NPs | Nanoparticles |

| NRU | Neutral Red assay |

| NTA | Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PDI | Polydispersity index |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| SSC | Side scatter |

References

- Abdullah, M.; Obayedullah, M.; Shariful, M.; Shuvo, I.; Abul Khair, M.; Hossain, D.; Nahidul Islam, M. A Review on Multifunctional Applications of Nanoparticles: Analyzing Their Multi-Physical Properties. Results Surf. Interfaces 2025, 21, 100635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eker, F.; Duman, H.; Akdaşçi, E.; Bolat, E.; Sarıtaş, S.; Karav, S.; Witkowska, A.M. A Comprehensive Review of Nanoparticles: From Classification to Application and Toxicity. Molecules 2024, 29, 3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musee, N.; Zvimba, J.N.; Schaefer, L.M.; Nota, N.; Sikhwivhilu, L.M.; Thwala, M. Fate and Behavior of ZnO- and Ag-Engineered Nanoparticles and a Bacterial Viability Assessment in a Simulated Wastewater Treatment Plant. J. Environ. Sci. Health A 2014, 49, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simelane, S.; Dlamini, L.N. An Investigation of the Fate and Behaviour of a Mixture of WO3 and TiO2 Nanoparticles in a Wastewater Treatment Plant. J. Environ. Sci. 2019, 76, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgantzopoulou, A.; Farkas, J.; Ndungu, K.; Coutris, C.; Carvalho, P.A.; Booth, A.M.; Macken, A. Wastewater-Aged Silver Nanoparticles in Single and Combined Exposures with Titanium Dioxide Affect the Early Development of the Marine Copepod Tisbe battagliai. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 12316–12325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, D.; Kumar, A. Binary Mixture of Nanoparticles in Sewage Sludge: Impact on Spinach Growth. Chemosphere 2020, 254, 126794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forest, V. Combined Effects of Nanoparticles and Other Environmental Contaminants on Human Health—An Issue Often Overlooked. NanoImpact 2021, 23, 100344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Wang, Z.; Peijnenburg, W.J.G.M.; Vijver, M.G. Review and Prospects on the Ecotoxicity of Mixtures of Nanoparticles and Hybrid Nanomaterials. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 15238–15250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auclair, J.; Turcotte, P.; Gagnon, C.; Peyrot, C.; Wilkinson, K.J.; Gagné, F. Investigation on the Toxicity of Nanoparticle Mixture in Rainbow Trout Juveniles. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihtisham, M.; Noori, A.; Yadav, S.; Sarraf, M.; Kumari, P.; Brestic, M.; Imran, M.; Jiang, F.; Yan, X.; Rastogi, A. Silver Nanoparticle’s Toxicological Effects and Phytoremediation. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.; Liu, X.; Qu, M. Nanoplastics and Human Health: Hazard Identification and Biointerface. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehner, R.; Weder, C.; Petri-Fink, A.; Rothen-Rutishauser, B. Emergence of Nanoplastic in the Environment and Possible Impact on Human Health. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 1748–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, C.Q.Y.; Valiyaveettil, S.; Tang, B.L. Toxicity of Microplastics and Nanoplastics in Mammalian Systems. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Palić, D. Micro- and Nano-Plastics Activation of Oxidative and Inflammatory Adverse Outcome Pathways. Redox Biol. 2020, 37, 101620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.M.; Gokulan, K.; Cerniglia, C.E.; Khare, S. Size- and Dose-Dependent Effects of Silver Nanoparticle Exposure on Intestinal Permeability in an In Vitro Model. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2016, 14, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Q.; Ma, J.; Li, X.; Meng, Q.; Wu, S.; Xie, Y.; Qi, Y.; Liu, S.; Chen, R. Intestinal Toxicity of Metal Nanoparticles: Silver Nanoparticles Disorder the Intestinal Immune Microenvironment. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 27774–27788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Cui, X.; Wu, J.; Bao, L.; Chen, C. Oral Administration of Silver Nanomaterials Affects the Gut Microbiota and Metabolic Profile Altering 5-HT Secretion in Mice. J. Mater. Chem. B 2023, 11, 1904–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grafmueller, S.; Manser, P.; Diener, L.; Diener, P.A.; Maeder-Althaus, X.; Maurizi, L.; Jochum, W.; Krug, H.F.; Buerki-Thurnherr, T.; von Mandach, U.; et al. Bidirectional Transfer of Polystyrene Nanoparticles across the Placental Barrier. Environ. Health Perspect. 2015, 123, 1280–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forte, M.; Iachetta, G.; Tussellino, M.; Carotenuto, R.; Prisco, M.; De Falco, M.; Laforgia, V.; Valiante, S. Polystyrene Nanoparticles Internalization in Human Gastric Adenocarcinoma Cells. Toxicol. In Vitro 2016, 31, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walczak, A.P.; Kramer, E.; Hendriksen, P.J.; Tromp, P.; Helsper, J.P.; van der Zande, M.; Rietjens, I.M.; Bouwmeester, H. Translocation of Differently Sized and Charged Polystyrene Nanoparticles in Intestinal Cell Models. Nanotoxicology 2015, 9, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walczak, A.P.; Kramer, E.; Hendriksen, P.J.; Helsdingen, R.M.; van der Zande, M.; Rietjens, I.M.; Bouwmeester, H. In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion Increases the Translocation of Polystyrene Nanoparticles. Nanotoxicology 2015, 9, 886–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, V.; Bohmert, L.; Lisicki, E.; Block, R.; Cara-Carmona, J.; Pack, L.K.; Selb, R.; Lichtenstein, D.; Voss, L.; Henderson, C.J.; et al. Uptake and Effects of Polystyrene Microplastics In Vitro and In Vivo. Arch. Toxicol. 2019, 93, 1817–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Męczyńska-Wielgosz, S.; Sikorska, K.; Czerwińska, M.; Kapka-Skrzypczak, L.; Kruszewski, M. Uptake and Toxicity of Polystyrene Nanoparticles in Three Human Cell Lines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, P.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, H. Synthesis, Applications, Toxicity and Toxicity Mechanisms of Silver Nanoparticles: A Review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 253, 114636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröter, L.; Ventura, N. Nanoplastic Toxicity: Insights and Challenges from Experimental Model Systems. Small 2022, 18, 2201680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, H.; Tian, X.; Lin, X.; Chen, R.; Hameed, S.; Wang, L.; Yu, Y.-L.; Li, B.; Li, Y.-F. Nanoplastic-Induced Biological Effects In Vivo and In Vitro: An Overview. Rev. Environ. Contam. 2023, 261, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Ibrahim, M.S.; Tan, L.Y.; Yeo, X.Y.; Lee, Y.A.; Park, S.J.; Wüstefeld, T.; Park, J.W.; Jung, S.; Cho, N.J. Microplastics from Food Containers Suppress Lysosomal Activity in Macrophages. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 435, 128980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Wang, J.; Wang, M.; Ying, R.; Li, X.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, Y. Disposable Plastic Materials Release Microplastics and Harmful Substances in Hot Water. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 818, 151685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, T.; Zhou, Y.; He, J.; Dong, R.; Xu, A.; Liu, Y. The released micro/nano-plastics from plastic containers amplified the toxic response of disinfection by-products in human cells. Food Chem. 2025, 470, 142636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trent, M.S.; Stead, C.M.; Tran, A.X.; Hankins, J.V. Diversity of endotoxin and its impact on pathogenesis. J. Endotoxin Res. 2006, 12, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Walle, J.; Hendrickx, A.; Romier, B.; Larondelle, Y.; Schneider, Y.-J. Inflammatory Parameters in Caco-2 Cells. Toxicol. Vitr. 2010, 24, 1441–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, G.W.; Gao, P. Emulsions and Microemulsions for Topical Drug Delivery. In Handbook of Non-Invasive Drug Delivery Systems; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 59–94. [Google Scholar]

- Samimi, S.; Maghsoudnia, N.; Eftekhari, R.B.; Dorkoosh, F. Lipid-Based Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery. In Characterization and Biology of Nanomaterials for Drug Delivery; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 47–76. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.L.; Lin, X.; Wang, J.J.; Gowen, A.A. Human Health Impacts of Micro- and Nanoplastics Exposure. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 851, 158111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabuncu, A.C.; Grubbs, J.; Qian, S.; Abdel-Fattah, T.M.; Stacey, M.W.; Beskok, A. Probing Nanoparticle Interactions. Colloids Surf. B 2012, 95, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derkani, M.H.; Fletcher, A.J.; Fedorov, M.; Abdallah, W.; Sauerer, B.; Anderson, J.; Zhang, Z.J. Mechanisms of surface charge modification of carbonates in aqueous electrolyte solutions. Colloids Interfaces 2019, 3, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partikel, K.; Korte, R.; Mulac, D.; Humpf, H.U.; Langer, K. Serum type and concentration both affect the protein-corona composition of PLGA nanoparticles. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2019, 10, 1002–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rycenga, M.; Cobley, C.M.; Zeng, J.; Li, W.; Moran, C.H.; Zhang, Q.; Qin, D.; Xia, Y. Controlling the synthesis and assembly of silver nanostructures for plasmonic applications. Chem. Rev. 2011, 8; 111, 3669–3712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastús, N.G.; Merkoçi, F.; Piella, J.; Puntes, W. Synthesis of Highly Monodisperse Citrate-Stabilized Silver Nanoparticles of up to 200 nm: Kinetic Control and Catalytic Properties. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 2836–2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbalinardo, M.; Ori, G.; Lungaro, L.; Caio, G.; Migliori, A.; Gentili, D. Direct Cationization of Citrate-Coated Gold and Silver Nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. C 2024, 128, 16220–16226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, J.; Löhr, K.; Karabudak, E.; Reis, W.; Mikhae, J.; Peukert, W.; Wohlleben, W.; Cölfen, H. Multidimensional Analysis of Nanoparticles with Highly Disperse Properties Using Multiwavelength Analytical Ultracentrifugation. ACS Nano 2014, 9, 8871–8886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, S.; Wang, B.; Dutta, P. Nanoparticle processing: Understanding and controlling aggregation. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 279, 102162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Loya, J.; Lerma, M.; Gardea-Torresdey, J.L. Dynamic Light Scattering and Its Application to Control Nanoparticle Aggregation in Colloidal Systems: A Review. Micromachines 2023, 15, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McComiskey, K.P.M.; Tajber, L. Comparison of particle size methodology and assessment of nanoparticle tracking 684 analysis (NTA) as a tool for live monitoring of crystallisation pathways. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2018, 130, 314–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankoff, A.; Sandberg, W.J.; Wegierek-Ciuk, A.; Lisowska, H.; Refsnes, M.; Sartowska, B.; Schwarze, P.E.; Meczynska-Wielgosz, S.; Wojewodzka, M.; Kruszewski, M. The effect of the agglomeration state of silver and titanium dioxide nanoparticles on cellular response of HepG2, A549 and THP-1 cells. Toxicol. Lett. 2012, 208, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehn, D.; Caputo, F.; Rösslein, M.; Calzolai, L.; Saint-Antonin, F.; Courant, T.; Wick, P.; Gilliland, D. Larger or more? 691 Nanoparticle characterization methods for recognition of dimers. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 27747–27754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikorska, K.; Grądzka, I.; Sochanowicz, B.; Presz, A.; Męczyńska-Wielgosz, S.; Brzóska, K.; Kruszewski, M.K. Di-694 minished amyloid-β uptake by mouse microglia upon treatment with quantum dots, silver or cerium oxide nanoparti-695 cles: Nanoparticles and amyloid-β uptake by microglia. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2019, 39, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Męczyńska-Wielgosz, S.; Wojewódzka, M.; Matysiak-Kucharek, M.; Czajka, M.; Jodłowska-Jędrych, B.; Kruszewski, M.; Kapka-Skrzypczak, L. Susceptibility of HepG2 Cells to Silver Nanoparticles in Combination with other Metal/Metal Oxide Nanoparticles. Materials 2020, 13, 2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikorska, K.; Grądzka, I.; Wasyk, I.; Brzóska, K.; Stępkowski, T.M.; Czerwińska, M.; Kruszewski, M.K. The Impact of Ag Nanoparticles and CdTe Quantum Dots on Expression and Function of Receptors Involved in Amyloid-β Uptake by BV-2 Microglial Cells. Materials 2020, 13, 3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behzadi, S.; Serpooshan, V.; Tao, W.; Hamaly, M.A.; Alkawareek, M.Y.; Dreaden, E.C.; Brown, D.; Alkilany, A.M.; Farokhzad, O.C.; Mahmoudi, M. Cellular uptake of nanoparticles: Journey inside the cell. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 4218–4244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustine, R.; Anwarul, H.; Primavera, R.; Wilson, R.J.; Avnesh, S.; Bhavesh, T.; Kevadiya, D. Cellular uptake and retention of nanoparticles: Insights on particle properties and interaction with cellular components. Mater. Today Commun. 2020, 25, 101692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, G.; Gruenberg, J.; Marsh, M.; Wohlmann, J.; Jones, A.T.; Parton, R.G. Nanoparticle entry into cells; the cell biology weak link. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2022, 188, 114403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscano, F.; Torres-Arias, M. Nanoparticles cellular uptake, trafficking, activation, toxicity and in vitro evaluation. Curr. Res. Immunol. 2023, 4, 100073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, F.; Shrestha, N.; Shahbazi, M.-A.; Fonte, P.; Mäkilä, E.M.; Salonen, J.J.; Hirvonen, J.T.; Granja, P.L.; Santos, H.A.; Sarmento, B. The impact of nanoparticles on the mucosal translocation and transport of GLP-1 across the intestinal epithelium. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 9199–9207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, M.; Komori, H.; Fujita, D.; Tamai, I. Uptake Pathway of Apple-derived Nanoparticle by Intestinal Cells to Deliver its Cargo. Pharm. Res. 2021, 38, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohal, I.S.; DeLoid, G.M.; O’Fallon, K.S.; Gaines, P.; Demokritou, P.; Bello, D. Effects of ingested food-grade titanium dioxide, silicon dioxide, iron (III) oxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles on an in vitro model of intestinal epithelium: Comparison between monoculture vs. a mucus-secreting coculture model. NanoImpact 2020, 17, 100209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, C.E.; Wheeler, K.M.; Ribbeck, K. Mucins and Their Role in Shaping the Functions of Mucus Barriers. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 34, 189–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marczynski, M.; Balzer, B.N.; Jiang, K.; Lutz, T.M.; Crouzier, T.; Lieleg, O. Charged glycan residues critically contribute to the adsorption and lubricity of mucins. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2020, 187, 110614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.D.; Crouzier, T.; Sarkar, A.; Dunphy, L.; Han, J.; Ribbeck, K. Spatial configuration and composition of charge modulates transport into a mucin hydrogel barrier. Biophys. J. 2013, 105, 1357–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najahi, H.; Alessio, N.; Venditti, M.; Lettiero, I.; Aprile, D.; Oliveri, C.G.; Cappello, T.; Di Bernardo, G.; Galderisi, U.; Minucci, S.; et al. Impact of environmental microplastic exposure on HepG2 cells: Unraveling proliferation, mitochondrial dynamics and autophagy activation. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2025, 22, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Leng, X.; Gao, J.; Huang, D. Polystyrene microplastics with absorbed nonylphenol induce intestinal dysfunction in human Caco-2 cells. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2024, 107, 104426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, S.; Kyong, H.; Sanghyun, S.; Lee, E. Effective removal of Micro- and nanoplastics from water using Iron oxide nanoparticles: Mechanisms and optimization. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 519, 165739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadac-Czapska, K.; Trzebiatowska, P.; Mazurkiewicz, M.; Kowalczyk, P.; Knez, E.; Behrendt, M.; Mahlik, S.; Zaleska-Medynska, A.; Grembecka, M. Isolation and identification of microplastics in infant formulas—A potential health risk for children. Food Chem. 2024, 440, 138246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.; Chen, S.; Li, L.; Wang, K.; Pang, A.; Niu, M.; Peng, X.; Li, N.; Wu, H.; Nie, P. Impact of polystyrene nanoplastics on apoptosis and inflammation in zebrafish larvae: Insights from reactive oxygen species perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 948, 174737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, A.; Fernandes, E.; Lima, J.L.F.C. Fluorescence probes used for detection of reactive oxygen species. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 2005, 65, 45–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruszewski, M.; Grzelak, A. Nanoparticle toxicity and reactive species: An overview. In Toxicology: Oxidative Stress and Dietary Antioxidants, 1st ed.; Patel, V.B., Preedy, V.R., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2020; pp. 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kruszewski, M.; Brzoska, K.; Brunborg, G.; Asare, N.; Dobrzyńska, M.; Dušinská, M.; Fjellsbø, L.M.; Georgantzopoulou, A.; Gromadzka-Ostrowska, J.; Gutleb, A.C.; et al. Toxicity of silver nanomaterials in higher eukaryotes. In Advances in Molecular Toxicology, 1st ed.; Fishbein, J.C., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; Chapter 5; pp. 179–218. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Niu, S.; Guo, M.; Xue, Y. Molecular mechanisms of silver nanoparticle-induced neurotoxic injury and 729 new perspectives for its neurotoxicity studies: A critical review. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 362, 124934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Shelver, W.L. Micro- and nanoplastic induced cellular toxicity in mammals: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 755, 142518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foroozandeh, P.; Aziz, A.A. Insight into Cellular Uptake and Intracellular Trafficking of Nanoparticles. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- des Rieux, A.; Fievez, V.; Théate, I.; Mast, J.; Préat, V.; Schneider, Y.-J. An improved in vitro model of human intestinal follicle-associated epithelium to study nanoparticle transport by M cells. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2007, 30, 380–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.M.; Fedorov, Y.; Brown, D.D.; Suh, M.; Proctor, D.M.; Kuriakose, L.; Haws, L.C.; Harris, M.A. Assessment of Cr(VI)-Induced Cytotoxicity and Genotoxicity Using High Content Analysis. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerloff, K.; Pereira, D.I.A.; Faria, N.; Boots, A.W.; Kolling, J.; Förster, I.; Albrecht, C.; Powell, J.J.; Schins, R.P.F. Influence of Simulated Gastrointestinal Conditions on Particle-Induced Cytotoxicity and Interleukin-8 Regulation in Differentiated and Undifferentiated Caco-2 Cells. Nanotoxicology 2012, 7, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bindels, D.S.; Haarbosch, L.; van Weeren, L.; Postma, M.; Wiese, K.E.; Mastop, M.; Aumonier, S.; Gotthard, G.; Royant, A.; Hink, M.A.; et al. mScarlet: A Bright Monomeric Red Fluorescent Protein for Cellular Imaging. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Time [h] | PBS | HT29MTX Medium (DMEM + 10% FBS) | Caco-2 Medium (EMEM + 10% FBS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrodynamic diameter [nm] | |||

| 0 | 198.7 ± 23.5 | 207.0 ± 20.1 | 209.3 ± 25.4 |

| 0.5 | 205.0 ± 28.1 | 208.0 ± 25.4 | 211.0 ± 19.2 |

| 2 | 212.0 ± 32.1 | 219.0 ± 29.8 | 221.0 ± 35.6 |

| 6 | 224.0 ± 33.9 | 232.0 ± 32.0 | 235.0 ± 33.1 |

| 24 | 239.0 ± 30.4 | 243.0 ± 29.4 | 245.0 ± 38.7 |

| Concentration [particles/mL] | |||

| 0 | 5.0 ± 0.5 (×109) | 4.8 ± 0.5 (×109) | 5.3 ± 0.6 (×109) |

| 0.5 | 4.5 ± 0.6 (×109) | 4.8 ± 0.6 (×109) | 5.2 ± 0.5 (×109) |

| 2 | 4.1 ± 0.6 (×109) | 4.2 ± 0.6 (×109) | 4.4 ± 0.6 (×109) |

| 6 | 3.5 ± 0.5 (×109) | 3.6 ± 0.5 (×109) | 3.7 ± 0.5 (×109) |

| 24 | 2.9 ± 0.4 (×109) | 3.1 ± 0.4 (×109) | 3.2 ± 0.5 (×109) |

| Time [h] | PBS | HT29MTX Medium (DMEM + 10% FBS) | Caco-2 Medium (EMEM + 10% FBS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrodynamic diameter [nm] | |||

| 0 | 245.23 ± 1.23 | 260.66 ± 0.77 | 265.20 ± 1.32 |

| 0.5 | 249.01 ± 0.92 | 272.23 ± 1.45 | 272.45 ± 2.22 |

| 2 | 256.92 ± 3.12 | 298.13 ± 2.45 | 301.24 ± 3.42 |

| 6 | 273.06 ± 2.08 | 315.87 ± 5.73 | 320.33 ± 3.76 |

| 24 | 299.31 ± 2.98 | 352.43 ± 4.33 | 361.82 ± 1.02 |

| Zeta potential [mV] | |||

| 0 | −37.91 ± 1.55 | −35.16 ± 5.21 | −35.63 ± 2.03 |

| 0.5 | −36.04 ± 2.06 | −34.23 ± 3.22 | −34.98 ± 1.67 |

| 2 | −35.03 ± 4.12 | −32.56 ± 1.37 | −31.32 ± 3.21 |

| 6 | −33.08 ± 0.23 | −30.44 ± 2.25 | −30.98 ± 1.03 |

| 24 | −30.92 ± 1.79 | −29.83 ± 4.02 | −29.80 ± 2.84 |

| Polydispersity index (PDI) | |||

| 0 | 0.42 ± 0.02 | 0.50 ± 0.03 | 0.50 ± 0.03 |

| 0.5 | 0.45 ± 0.03 | 0.50 ± 0.03 | 0.50 ± 0.04 |

| 2 | 0.52 ± 0.04 | 0.58 ± 0.05 | 0.57 ± 0.05 |

| 6 | 0.62 ± 0.05 | 0.68 ± 0.06 | 0.70 ± 0.07 |

| 24 | 0.73 ± 0.06 | 0.82 ± 0.07 | 0.90 ± 0.09 |

| Time [h] | PBS | HT29MTX Medium (DMEM + 10% FBS) | Caco-2 Medium (EMEM + 10% FBS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrodynamic diameter [nm] | |||

| 0 | 36.2 ± 3.1 | 34.9 ± 0.4 | 41.6 ± 3.7 |

| 0.5 | 48.3 ± 3.7 | 52.6 ± 4.1 | 42.2 ± 4.3 |

| 2 | 21.8 ± 4.9 | 56.1 ± 3.9 | 32.0 ± 4.9 |

| 6 | 59.5 ± 4.1 | 71.5 ± 4.5 | 61.1 ± 4.1 |

| 24 | 31.9 ± 3.9 | 65.7 ± 4.4 | 48.5 ± 4.7 |

| Concentration [particles/mL] | |||

| 0 | 1.8 ± 1.1 (×108) | 4.6 ± 4.9 (×108) | 6.6 ± 3.6 (×107) |

| 0.5 | 2.1 ± 4.8 (×108) | 5.1 ± 3.7 (×107) | 5.7 ± 2.2 (×107) |

| 2 | 3.0 ± 3.9 (×108) | 4.6 ± 3.8 (×107) | 4.9 ± 4.5 (×107) |

| 6 | 5.6 ± 3.5 (×107) | 5.7 ± 4.6 (×107) | 7.1 ± 1.6 (×107) |

| 24 | 3.8 ± 2.1 (×107) | 7.3 ± 1.9 (×107) | 6.8 ± 4.9 (×107) |

| Time [h] | PBS | HT29MTX Medium (DMEM + 10% FBS) | Caco-2 Medium (EMEM + 10% FBS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrodynamic diameter [nm] | |||

| 0 | 28.32 ± 2.94 | 84.32 ± 3.21 | 80.24 ± 4.23 |

| 0.5 | 30.24 ± 3.11 | 99.10 ± 4.09 | 95.12 ± 2.34 |

| 2 | 34.67 ± 4.91 | 120.45 ± 2.23 | 116.23 ± 3.41 |

| 6 | 38.21 ± 4.12 | 138.73 ± 2.32 | 134.23 ± 4.34 |

| 24 | 46.12 ± 5.43 | 163.43 ± 4.37 | 158.67 ± 3.04 |

| Zeta potential [mV] | |||

| 0 | −36.7 ± 3.21 | −35.0 ± 3.33 | −35.0 ± 3.21 |

| 0.5 | −35.9 ± 3.41 | −34.5 ± 3.30 | −34.6 ± 2.12 |

| 2 | −34.8 ± 3.60 | −33.2 ± 2.13 | −33.8 ± 1.21 |

| 6 | −31.6 ± 4.21 | −32.7 ± 2.14 | −32.5 ± 2.45 |

| 24 | −28.2 ± 3.54 | −30.01 ± 4.31 | −31.0 ± 4.20 |

| Polydispersity index (PDI) | |||

| 0 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 0.22 ± 0.03 | 0.22 ± 0.02 |

| 0.5 | 0.13 ± 0.02 | 0.26 ± 0.04 | 0.25 ± 0.03 |

| 2 | 0.16 ± 0.03 | 0.28 ± 0.02 | 0.30 ± 0.04 |

| 6 | 0.18 ± 0.04 | 0.34 ± 0.05 | 0.34 ± 0.04 |

| 24 | 0.21 ± 0.05 | 0.38 ± 0.03 | 0.35 ± 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Męczyńska-Wielgosz, S.; Sikorska, K.; Czerwińska, M.; Grzelak, A.; Lankoff, A.; Kruszewski, M. Toxicity of High-Density Polyethylene Nanoparticles in Combination with Silver Nanoparticles to Caco-2 and HT29MTX Cells Growing in 2D or 3D Culture. Molecules 2026, 31, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010003

Męczyńska-Wielgosz S, Sikorska K, Czerwińska M, Grzelak A, Lankoff A, Kruszewski M. Toxicity of High-Density Polyethylene Nanoparticles in Combination with Silver Nanoparticles to Caco-2 and HT29MTX Cells Growing in 2D or 3D Culture. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleMęczyńska-Wielgosz, Sylwia, Katarzyna Sikorska, Malwina Czerwińska, Agnieszka Grzelak, Anna Lankoff, and Marcin Kruszewski. 2026. "Toxicity of High-Density Polyethylene Nanoparticles in Combination with Silver Nanoparticles to Caco-2 and HT29MTX Cells Growing in 2D or 3D Culture" Molecules 31, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010003

APA StyleMęczyńska-Wielgosz, S., Sikorska, K., Czerwińska, M., Grzelak, A., Lankoff, A., & Kruszewski, M. (2026). Toxicity of High-Density Polyethylene Nanoparticles in Combination with Silver Nanoparticles to Caco-2 and HT29MTX Cells Growing in 2D or 3D Culture. Molecules, 31(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010003