Enhancing Antioxidant and Flavor of Xuanwei Ham Bone Hydrolysates via Ultrasound and Microwave Pretreatment: A Backpropagation Artificial Neural Network Model Prediction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

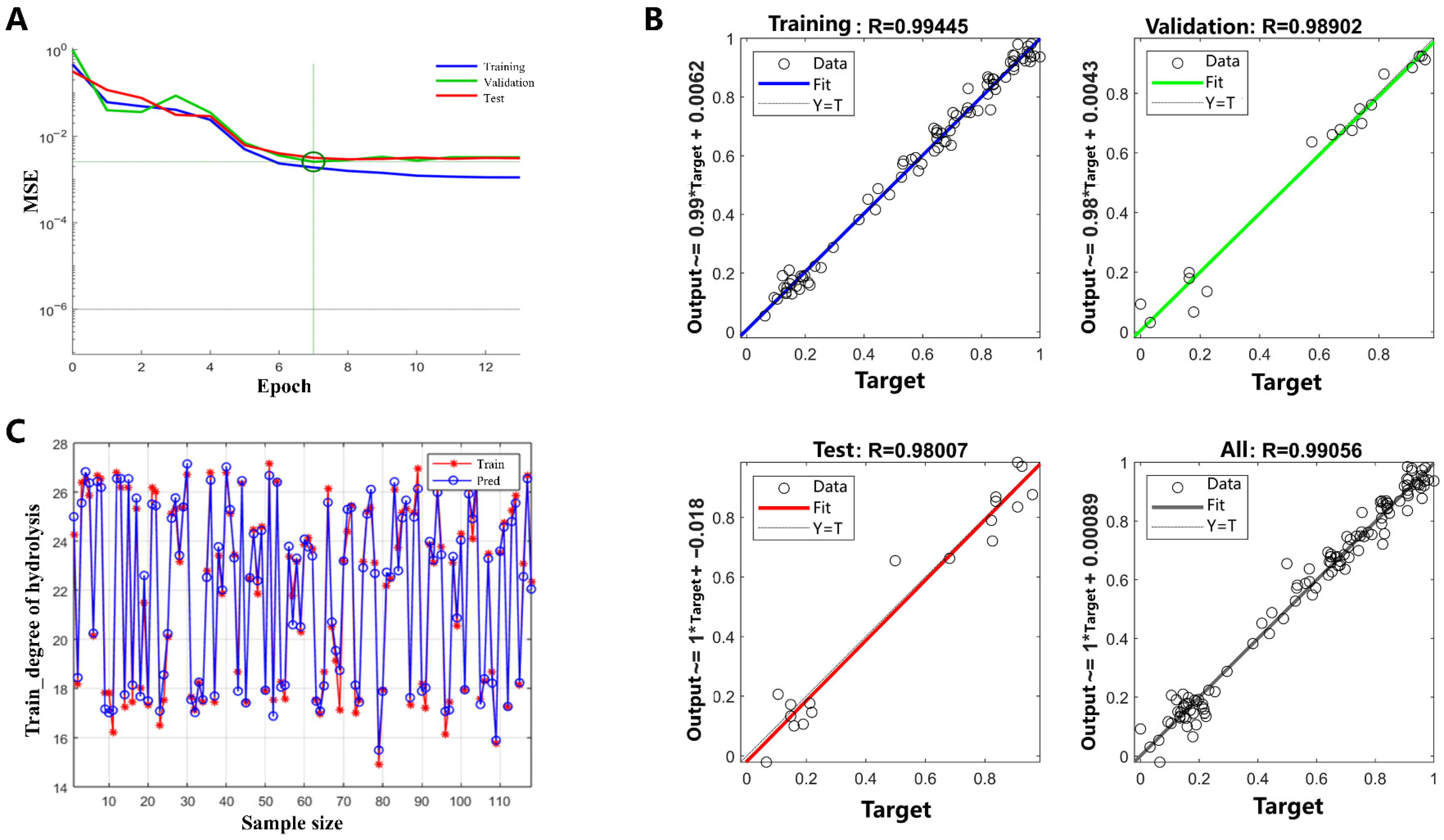

2.1. BP-ANN Model Development

2.1.1. Optimization of the Hidden Nodes Number

2.1.2. Training, Validation and Testing of the Model

2.1.3. Contribution of Each Input Variable on DH

2.1.4. Prediction of DH by Each Input Variable

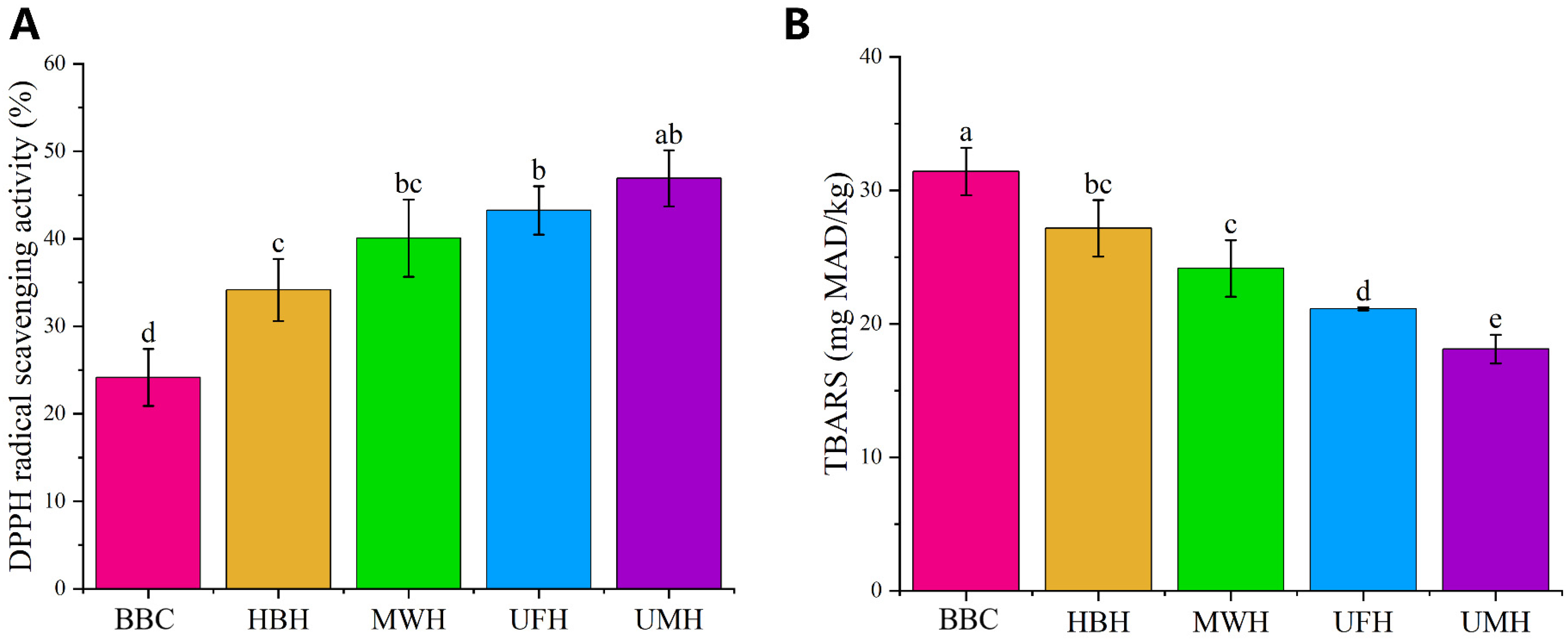

2.2. Antioxidant Capacity

2.2.1. Changes in DPPH Free Radical Scavenging Assay

2.2.2. Changes in TBARS

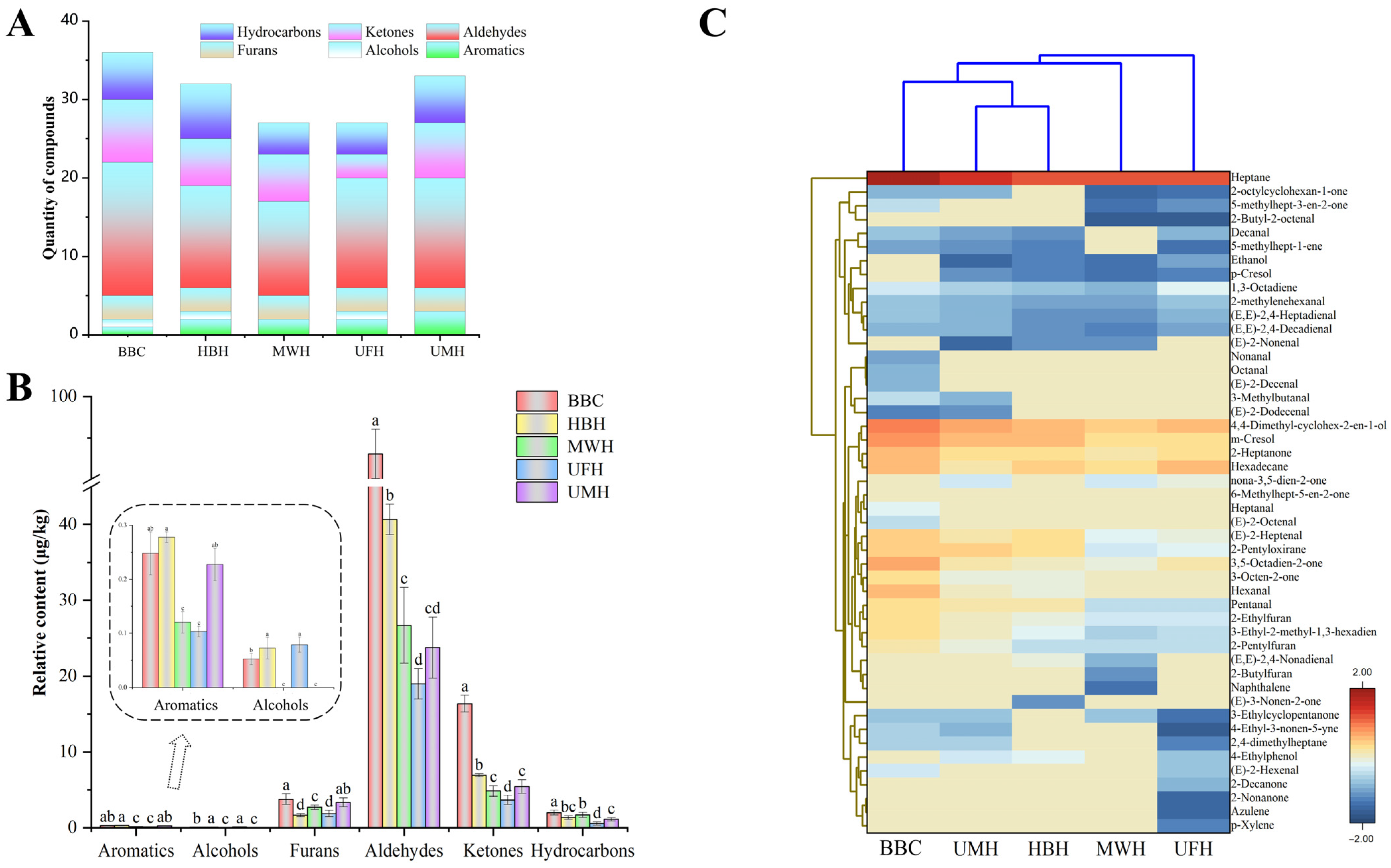

2.3. Aroma Profiles

2.3.1. HS–SPME/GC–MS Analysis

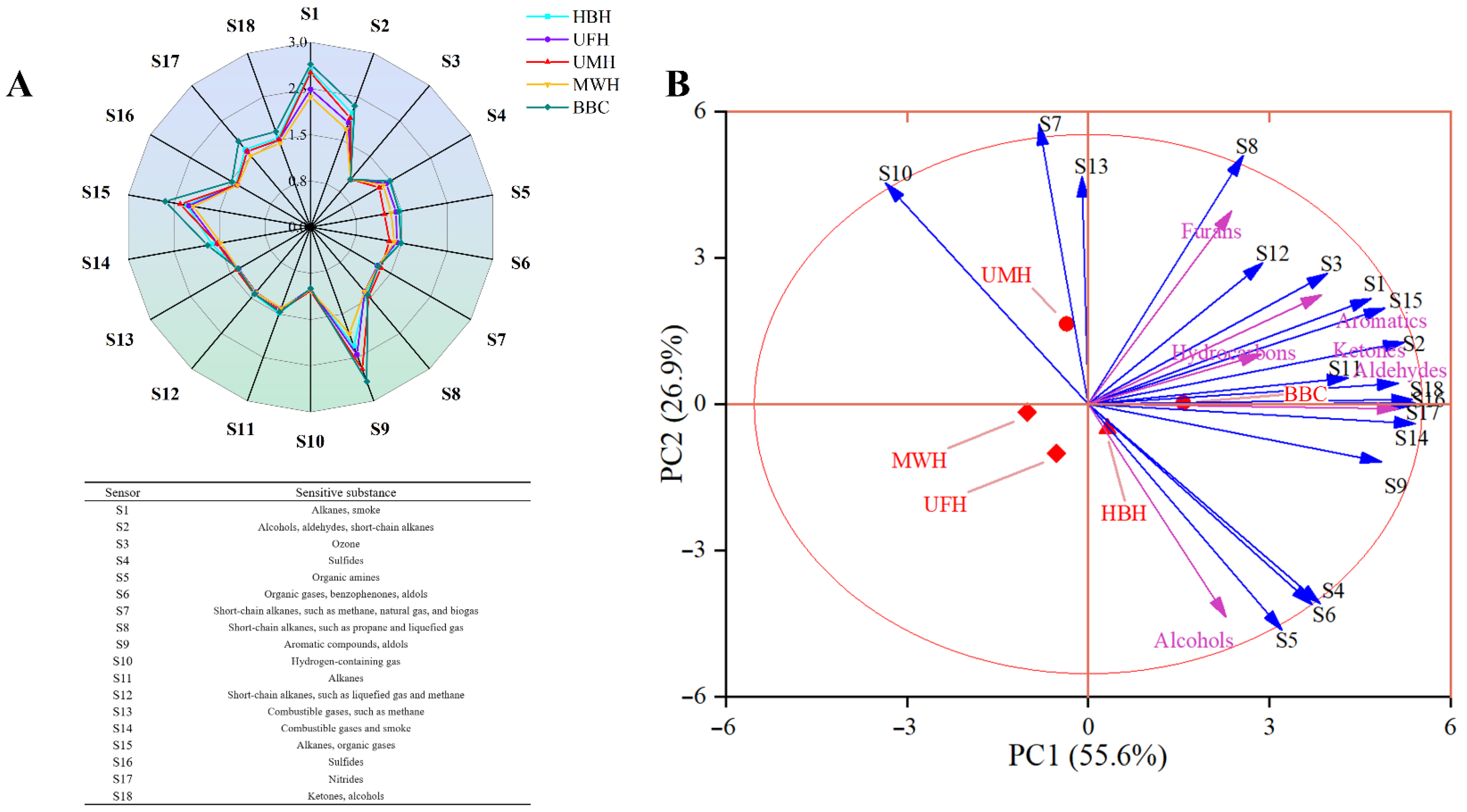

2.3.2. E-Nose Analysis

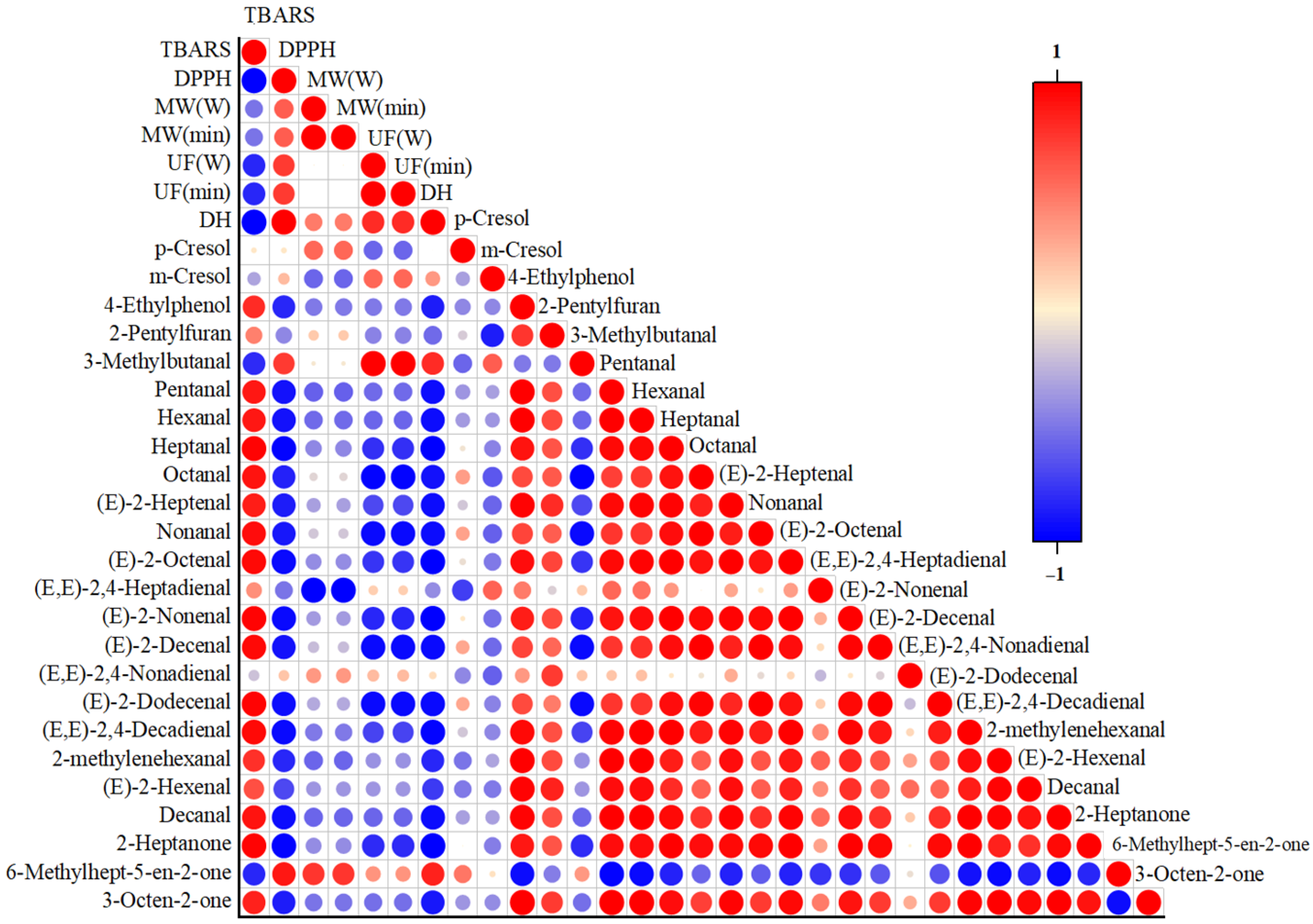

2.4. Correlation Between Basic Properties and Aroma

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Sample Preparation Before Enzymatic Hydrolysis

3.3. Preparation of Enzymatic Hydrolysates

3.4. Degree of Hydrolysis (DH) Detection

3.5. Back Propagation Artificial Neural Network Mode (BP-ANN) Design

3.6. DPPH Free Radical Scavenging Assay

3.7. Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances (TBARS) Value Determination

3.8. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC–MS) Measurement Based on Headspace-Solid Phase Microextraction (HS-SPME)

3.9. Electronic Nose (E-Nose) Detection

3.10. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| E-Nose | Electronic Nose |

| BBC | Bone Broth Control |

| DH | Degree of Hydrolysis |

| GC–MS | Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry |

| HBH | Ham Bone Hydrolysates |

| HS-SPME | Headspace-Solid Phase Microextraction |

| MWH | Microwave Pretreatment Hydrolysates |

| TBARS | Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances |

| UFH | Ultrasound Pretreatment Hydrolysates |

| UMH | Ultrasound Combined Microwave Pretreatment Hydrolysates |

References

- Cui, H.; Li, H.; Wu, Y.; Hu, X. Identification, flavor characteristics and molecular docking of umami taste peptides of Xuanwei ham. Food Res. Int. 2023, 173, 113211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, M.; Mora, L.; Hayes, M.; Reig, M.; Toldrá, F. Peptides with Potential Cardioprotective Effects Derived from Dry-Cured Ham Byproducts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 1115–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Z.; Zhang, M.; Liu, W.; Liu, Y. Effect of beef tallow, phospholipid and microwave combined ultrasonic pretreatment on Maillard reaction of bovine bone enzymatic hydrolysate. Food Chem. 2022, 377, 131902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Z.; Zhang, M.; Fan, H.; Liu, Y. Effect of microwave combined with ultrasonic pretreatment on flavor and antioxidant activity of hydrolysates based on enzymatic hydrolysis of bovine bone. Food Biosci. 2021, 44, 101399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Wang, M.; Liu, Y.; Han, L.; Liu, X. Insights into the improvement of the enzymatic hydrolysis of bovine bone protein using lipase pretreatment. Food Chem. 2020, 302, 125199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, X.; Luan, J.; Zhu, W.; Xu, Y.; Yi, S.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Li, X. Effects of ultrasound pretreatment at different powers on flavor characteristics of enzymatic hydrolysates of cod (Gadus macrocephalus) head. Food Res. Int. 2022, 159, 111612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Chen, W.; Fan, K. Recent advances in combined ultrasound and microwave treatment for improving food processing efficiency and quality: A review. Food Biosci. 2024, 58, 103683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Law, C.L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, K. Optimization of Ultrasonic-Assisted Enzymatic Hydrolysis to Extract Soluble Substances from Edible Fungi By-products. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2023, 16, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Li, Y.; Sun, G.; Wang, C.; Liang, Y.; Zhao, X.; He, J.; Mo, H. Influence of ultrasound treatment on the physicochemical and antioxidant properties of mung bean protein hydrolysate. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022, 84, 105964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Li, Y.; Li, C.; Ruan, S.; Roknul Azam, S.M.; Ou Yang, N.; Ye, X.; Wang, Y.; Ma, H. Effects of ultrasound-assisted sodium bisulfite pretreatment on the preparation of cholesterol-lowering peptide precursors from soybean protein. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 183, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhag, R.; Dhiman, A.; Deswal, G.; Thakur, D.; Sharanagat, V.S.; Kumar, K.; Kumar, V. Microwave processing: A way to reduce the anti-nutritional factors (ANFs) in food grains. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 150, 111960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habinshuti, I.; Mu, T.H.; Zhang, M. Ultrasound microwave-assisted enzymatic production and characterisation of antioxidant peptides from sweet potato protein. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020, 69, 105262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Ruan, G.; Qin, Z.; Li, H.; Zheng, Y. Antioxidant activity measurement and potential antioxidant peptides exploration from hydrolysates of novel continuous microwave-assisted enzymolysis of the Scomberomorus niphonius protein. Food Chem. 2017, 223, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; You, Y.; Zeng, X.; Liu, Q.; Dong, H.; Qian, M.; Xiao, S.; Yu, L.; Hu, X. Back propagation artificial neural network (BP-ANN) for prediction of the quality of gamma-irradiated smoked bacon. Food Chem. 2024, 437, 137806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Ma, J.; Wang, Q.; Sun, D. Applications of machine learning techniques for enhancing nondestructive food quality and safety detection. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 1649–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.; Ren, G.; Law, C.L.; Li, L.; Cao, W.; Luo, Z.; Pan, L.; Duan, X.; Chen, J.; Liu, W. Novel strategy for optimizing of corn starch-based ink food 3D printing process: Printability prediction based on BP-ANN model. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 276, 133921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Z.; Gao, J. Pixel-level aflatoxin detecting based on deep learning and hyperspectral imaging. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 164, 104888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gong, H.; Shi, C.; Yuan, H.; Zuo, X.; Chang, Y.; Li, X. Modeling and optimization of the hydrolysis and acidification via liquid fraction of digestate from corn straw by response surface methodology and artificial neural network. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 361, 132241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Hu, Y.; Hong, Y.; Xu, L.; Zhou, M.; Fu, C.; Wang, C.; Xu, N.; Li, D. Analysis of the hydrolytic capacities of Aspergillus oryzae proteases on soybean protein using artificial neural networks. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2016, 40, 918–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Shi, X.; Xue, J.; Zhao, S.; Jia, C.; Niu, M.; Zhang, B.; Xu, Y. Quality prediction of whole-grain rice noodles using backpropagation artificial neural network. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, 104, 4371–4382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagya Raj, G.V.S.; Dash, K.K. Comprehensive study on applications of artificial neural network in food process modeling. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 2756–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Cai, K.; Tu, Z.; Nie, W.; Ji, T.; Hu, B.; Chen, C.; Jiang, S. Prediction of benzo[a]pyrene content of smoked sausage using back-propagation artificial neural network. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 3022–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, P.L.; Koh, X.J. Ultrasound-assisted enzymatic hydrolysis enhances anti-inflammatory and hypoglycemic activities of edible Bird’s nest. Food Biosci. 2023, 56, 103221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayim, I.; Ma, H.; Alenyorege, E.A.; Ali, Z.; Donkor, P.O. Influence of ultrasound pretreatment on enzymolysis kinetics and thermodynamics of sodium hydroxide extracted proteins from tea residue. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 1037–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Pei, J.; Ma, H.; Wang, Z. Effects of ultrasound on molecular properties, structure, chain conformation and degradation kinetics of carboxylic curdlan. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 121, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, X.; Liu, J.; Ren, S.; Zhu, L.; Li, B.; Zhang, B. Research progress in ultrasound and its assistance treatment to reduce food allergenicity: Mechanisms, influence factor, application and prospect. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 278, 134687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Lamsal, B.P. Ultrasound-assisted extraction and modification of plant-based proteins: Impact on physicochemical, functional, and nutritional properties. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 1457–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Yan, L.; Ma, X.; Wang, W.; Zou, M.; Zhong, J.; Ding, T.; Ye, X.; Liu, D. Ultrasound promotes enzymatic reactions by acting on different targets: Enzymes, substrates and enzymatic reaction systems. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 119, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdualrahman, M.A.Y.; Ma, H.; Zhou, C.; Yagoub, A.E.A.; Hu, J.; Yang, X. Thermal and single frequency counter-current ultrasound pretreatments of sodium caseinate: Enzymolysis kinetics and thermodynamics, amino acids composition, molecular weight distribution and antioxidant peptides. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 4861–4873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wali, A.; Ma, H.; Hayat, K.; Ren, X.; Ali, Z.; Duan, Y.; Rashid, M.T. Enzymolysis reaction kinetics and thermodynamics of rapeseed protein with sequential dual-frequency ultrasound pretreatment. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 53, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, F.; Liceaga, A. Effect of microwave-assisted enzymatic hydrolysis of cricket (Gryllodes sigillatus) protein on ACE and DPP-IV inhibition and tropomyosin-IgG binding. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 64, 103634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, J.; Lin, S.; Yang, Z.; Jin, H. Preparation of Antioxidant Peptide by Microwave- Assisted Hydrolysis of Collagen and Its Protective Effect Against H2O2-Induced Damage of RAW264.7 Cells. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.C.; Zou, Y.H.; Cheng, Y.P.; Xing, L.J.; Zhou, G.H.; Zhang, W.G. Effects of power ultrasound on oxidation and structure of beef proteins during curing processing. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2016, 33, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawalbeh, D.; Al-U’datt, M.H.; Wan Ahmad, W.A.; Ahmad, F.; Sarbon, N.M. Recent Advances in In Vitro and In Vivo Studies of Antioxidant, ACE-Inhibitory and Anti-Inflammatory Peptides from Legume Protein Hydrolysates. Molecules 2023, 28, 2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Zhao, Y.; Dong, H.; Su, G.; Zhao, M. Structure–activity relationship of antioxidant dipeptides: Dominant role of Tyr, Trp, Cys and Met residues. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 21, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Zheng, Y.; Zhu, X.; Li, S.; Zhou, C. L-lysine and L-arginine inhibit the oxidation of lipids and proteins of emulsion sausage by chelating iron ion and scavenging radical. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 31, 905–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Ma, C.M.; Bian, X.; Liu, X.F.; Wang, Y.; Chen, F.L.; Wang, B.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, N. Characterization of the structure, antioxidant activity and hypoglycemic activity of soy (Glycine max L.) protein hydrolysates. Food Res. Int. 2023, 173, 113473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketnawa, S.; Liceaga, A.M. Effect of Microwave Treatments on Antioxidant Activity and Antigenicity of Fish Frame Protein Hydrolysates. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2017, 10, 582–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lone, A.B.; Bhat, H.F.; AïtKaddour, A.; Hassoun, A.; Aadil, R.M.; Dar, B.N.; Bhat, Z.F. Cricket protein hydrolysates pre-processed with ultrasonication and microwave improved storage stability of goat meat emulsion. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2023, 86, 103364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Wang, F.; Yu, L.; Jiang, B.; Cao, J.; Sun, Z.; Cheng, J. Effect of ultrasound on the characterization and peptidomics of foxtail millet bran protein hydrolysates. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2024, 110, 107044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinthusamran, S.; Benjakul, S.; Kijroongrojana, K.; Prodpran, T.; Agustini, T.W. Yield and chemical composition of lipids extracted from solid residues of protein hydrolysis of Pacific white shrimp cephalothorax using ultrasound-assisted extraction. Food Biosci. 2018, 26, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Xu, Y.; Yi, S.; Zhu, W.; Mi, H.; Li, T.; Li, J. Combined ultrasound and heat pretreatment improve the enzymatic hydrolysis of clam (Aloididae aloidi) and the flavor of hydrolysates. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2021, 67, 102596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Kao, T.; Chen, B. Development of a GC–MS/MS method coupled with HS-SPME-Arrow for studying formation of furan and 10 derivatives in model systems and commercial foods. Food Chem. 2022, 395, 133572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Liu, Z.; Liu, H.; Sun, J.; Chen, H.; Sun, B. Characterization of key volatile flavor compounds in dried sausages by HS-SPME and SAFE, which combined with GC-MS, GC-O and OAV. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 133, 106438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, M.; Mujumdar, A.S.; Liu, Y. Maillard reaction products of pea protein hydrolysate as a flavour enhancer for beef flavors: Effects on flavor and physicochemical properties. Food Chem. 2023, 417, 135769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czelej, M.; Garbacz, K.; Czernecki, T.; Wawrzykowski, J.; Waśko, A. Protein Hydrolysates Derived from Animals and Plants—A Review of Production Methods and Antioxidant Activity. Foods 2022, 11, 1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquaticci, L.; Schouten, M.A.; Angeloni, S.; Caprioli, G.; Vittori, S.; Romani, S. Influence of baking conditions and formulation on furanic derivatives, 3-methylbutanal and hexanal and other quality characteristics of lab-made and commercial biscuits. Food Chem. 2024, 437, 137791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Mora, L.; Toldrá, F.; Zhang, W.; Flores, M. Effects of ultrasound pretreatment on flavor characteristics and physicochemical properties of dry-cured ham slices during refrigerated vacuum storage. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 199, 116132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grebenteuch, S.; Kroh, L.W.; Drusch, S.; Rohn, S. Formation of Secondary and Tertiary Volatile Compounds Resulting from the Lipid Oxidation of Rapeseed Oil. Foods 2021, 10, 2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ke, J.; Long, P.; Wen, M.; Han, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, M. Formation of Furan from Linoleic Acid Thermal Oxidation: (E,E)-2,4-Decadienal as a Critical Intermediate Product. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 4384–4392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Cai, Y.; Fu, X.; Zheng, L.; Xiao, Z.; Zhao, M. Comparison of aroma-active compounds in broiler broth and native chicken broth by aroma extract dilution analysis (AEDA), odor activity value (OAV) and omission experiment. Food Chem. 2018, 265, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasunaga, M.; Takai, E.; Hattori, S.; Tatematsu, K.; Kuroda, S.i. Effects of 3-octen-2-one on human olfactory receptor responses to vanilla flavor. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2022, 86, 1562–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Ikram, S.; Zhao, T.; Shao, Y.; Liu, R.; Song, F.; Sun, B.; Ai, N. 2-Heptanone, 2-nonanone, and 2-undecanone confer oxidation off-flavor in cow milk storage. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 8538–8550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, G.; Min, S.; Jo, Y. Anti-Oxidative and Anti-Aging Activities of Porcine By-Product Collagen Hydrolysates Produced by Commercial Proteases: Effect of Hydrolysis and Ultrafiltration. Molecules 2019, 24, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merz, M.; Eisele, T.; Berends, P.; Appel, D.; Rabe, S.; Blank, I.; Stressler, T.; Fischer, L. Flavourzyme, an Enzyme Preparation with Industrial Relevance: Automated Nine-Step Purification and Partial Characterization of Eight Enzymes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 5682–5693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 5009.5; Determination of Protein in Food. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2016; Volume Chinese Standard GB 5009.5.

- Cervera Gascó, J.; Rabadán, A.; López Mata, E.; Álvarez Ortí, M.; Pardo, J.E. Development of the POLIVAR model using neural networks as a tool to predict and identify monovarietal olive oils. Food Control 2023, 143, 109278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garson, D.G. Interpreting neural network connection weights. Al Expert 1991, 6, 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kothakota, A.; Pandiselvam, R.; Siliveru, K.; Pandey, J.P.; Sagarika, N.; Srinivas, C.H.S.; Kumar, A.; Singh, A.; Prakash, S.D. Modeling and Optimization of Process Parameters for Nutritional Enhancement in Enzymatic Milled Rice by Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) and Artificial Neural Network (ANN). Foods 2021, 10, 2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Chen, C.; Song, Z.; Chang, M.; Yao, L.; Jin, Q.; Wang, X. Effect of microwave pretreatment of perilla seeds on minor bioactive components content and oxidative stability of oil. Food Chem. 2022, 388, 133010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Liu, Q.; Ni, X.; Chen, C.; Deng, X.; Fang, Y.; Wang, X.; Shen, Q.; Yu, R. Lipidomics reveals the effect of hot-air drying on the quality characteristics and lipid oxidation of Tai Lake whitebait (Neosalanx taihuensis Chen). LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 197, 115942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.; Wang, X.; Guo, C.; Zang, L.; He, H.; Yin, X.; Wei, J.; Cao, J. Quality and Flavor Difference in Dry-Cured Meat Treated with Low-Sodium Salts: An Emphasis on Magnesium. Molecules 2024, 29, 2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Neuron Number (j) | Weight to Hidden Layer from Input Variable | To Output Variable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 1 | −1.367 | −0.472 | −0.641 | −0.315 | 0.830 |

| 2 | −1.982 | 2.0567 | −0.909 | −0.548 | 0.3361 |

| 3 | 2.253 | −0.668 | 0.389 | 0.347 | −0.7664 |

| 4 | −2.720 | −0.049 | −0.209 | −0.009 | −1.198 |

| 5 | 0.833 | −0.535 | 0.667 | 0.439 | 0.998 |

| 6 | 2.638 | 0.457 | −1.089 | −0.498 | 0.473 |

| Experiment Number | Ultrasound | Microwave | DH (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power (W/gbone) | Time (min) | Power (W/gbone) | Time (min) | Expt. | BP-ANN Pred. | |

| 1 | 15 | 15 | 5 | 20 | 26.65 ± 0.20 b | 26.15 |

| 2 | 15 | 15 | 5 | 30 | 28.33 ± 0.18 a | 27.69 |

| 3 | 15 | 15 | 7 | 20 | 27.05 ± 0.63 b | 26.49 |

| 4 | 15 | 15 | 7 | 30 | 28.16 ± 0.42 a | 27.53 |

| 5 | 20 | 15 | 5 | 30 | 26.05 ± 0.32 c | 25.63 |

| 6 | 20 | 15 | 7 | 30 | 25.21 ± 0.10 c | 25.49 |

| Volatile Compounds | Threshold (μg/kg) | BBC | HBH | MWH | UFH | UMH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-Cresol | 0.00024 | ND | ND | 250.16 | ND | ND |

| m-Cresol | 0.00044 | ND | ND | ND | 95.35 | ND |

| 4-Ethylphenol | 0.021 | 11.81 | 11.81 | ND | ND | 2.43 |

| 2-Pentylfuran | 0.27 | 12.78 | 5.37 | 9.40 | 6.38 | 11.46 |

| 3-Methylbutanal | 0.00035 | ND | ND | ND | 66.94 | 62.80 |

| Pentanal | 0.85 | 1.75 | 0.88 | 0.35 | 0.39 | 0.40 |

| Hexanal | 5 | 13.27 | 4.92 | 2.72 | 2.62 | 3.25 |

| Heptanal | 0.26 | 11.57 | 4.23 | 3.28 | ND | ND |

| Octanal | 0.00088 | 2587.01 | 3181.82 | 1955.86 | 453.44 | 678.04 |

| (E)-2-Heptenal | 2.4 | 1.56 | 0.88 | 0.80 | 0.53 | 0.78 |

| Nonanal | 0.0031 | 799.29 | 451.61 | 597.00 | 199.66 | 230.34 |

| (E)-2-Octenal | 0.0027 | 2236.00 | 1111.11 | 1113.32 | 667.38 | 767.18 |

| (E, E)-2,4-Heptadienal | 0.057 | 2.81 | 3.16 | ND | 2.88 | 0.70 |

| (E)-2-Nonenal | 0.00009 | 17,402.65 | 12,222.22 | 9352.11 | 4184.33 | 4964.80 |

| (E)-2-Decenal | 0.0027 | 620.61 | 481.48 | 437.22 | 114.68 | 111.71 |

| (E, E)-2,4-Nonadienal | 0.0002 | 1910.11 | 1050.00 | 922.96 | 655.56 | 3074.36 |

| (E)-2-Dodecenal | 0.011 | 103.27 | 90.91 | 68.01 | 13.06 | ND |

| (E, E)-2,4-Decadienal | 0.0023 | 702.85 | 491.30 | 210.15 | 103.63 | 114.61 |

| 2-Methylenehexanal | 0.1 | 2.98 | ND | ND | 0.43 | 0.74 |

| (E)-2-Hexenal | 0.0031 | 123.54 | ND | ND | ND | 50.52 |

| Decanal | 0.0026 | 54.63 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 2-Heptanone | 0.0035 | 554.92 | 228.57 | 186.37 | ND | ND |

| 6-Methylhept-5-en-2-one | 0.01889 | ND | 3.71 | 2.88 | 2.00 | 2.60 |

| 3-Octen-2-one | 0.0067 | 1273.34 | 671.64 | 437.67 | 414.55 | 542.94 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, X.; Feng, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, N.; Jin, Y.; Cao, J.; Wang, X.; Guo, C. Enhancing Antioxidant and Flavor of Xuanwei Ham Bone Hydrolysates via Ultrasound and Microwave Pretreatment: A Backpropagation Artificial Neural Network Model Prediction. Molecules 2026, 31, 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010188

Chen X, Feng X, Wang X, Zhang N, Jin Y, Cao J, Wang X, Guo C. Enhancing Antioxidant and Flavor of Xuanwei Ham Bone Hydrolysates via Ultrasound and Microwave Pretreatment: A Backpropagation Artificial Neural Network Model Prediction. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):188. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010188

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Xin, Xianchao Feng, Xingwei Wang, Nianwen Zhang, Yuxia Jin, Jianxin Cao, Xuejiao Wang, and Chaofan Guo. 2026. "Enhancing Antioxidant and Flavor of Xuanwei Ham Bone Hydrolysates via Ultrasound and Microwave Pretreatment: A Backpropagation Artificial Neural Network Model Prediction" Molecules 31, no. 1: 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010188

APA StyleChen, X., Feng, X., Wang, X., Zhang, N., Jin, Y., Cao, J., Wang, X., & Guo, C. (2026). Enhancing Antioxidant and Flavor of Xuanwei Ham Bone Hydrolysates via Ultrasound and Microwave Pretreatment: A Backpropagation Artificial Neural Network Model Prediction. Molecules, 31(1), 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010188