Evaluation of Pyrrole Heterocyclic Derivatives as Selective MAO-B Inhibitors and Neuroprotectors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

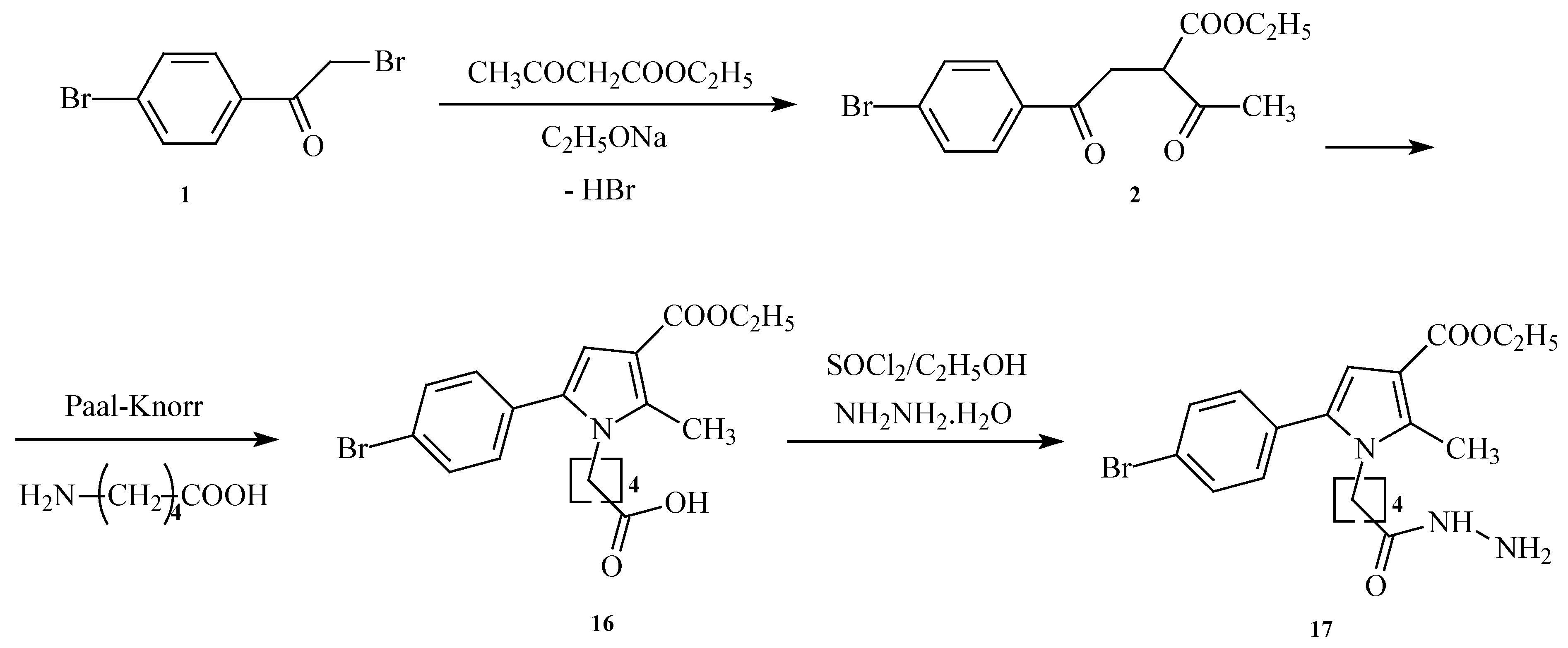

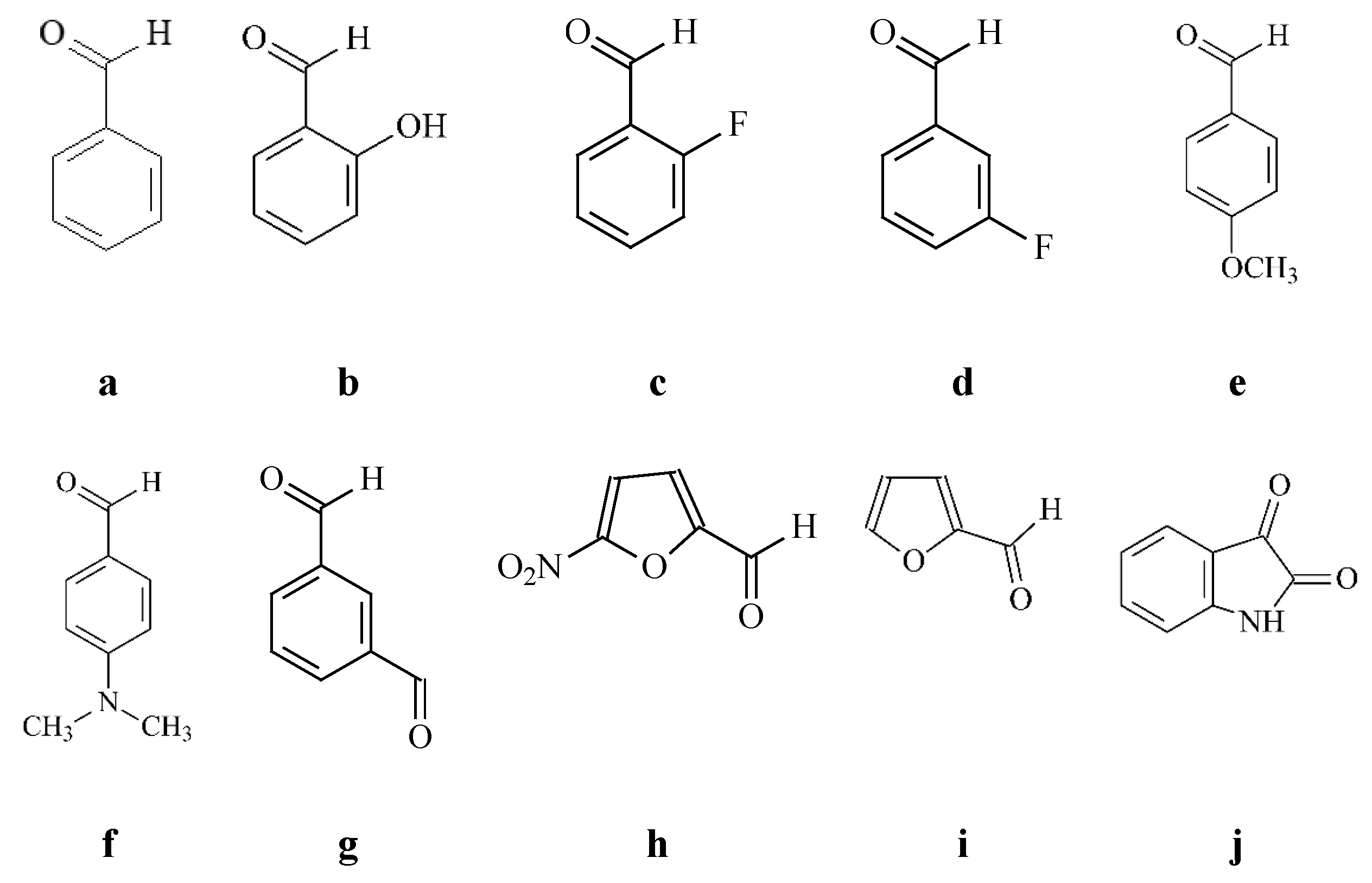

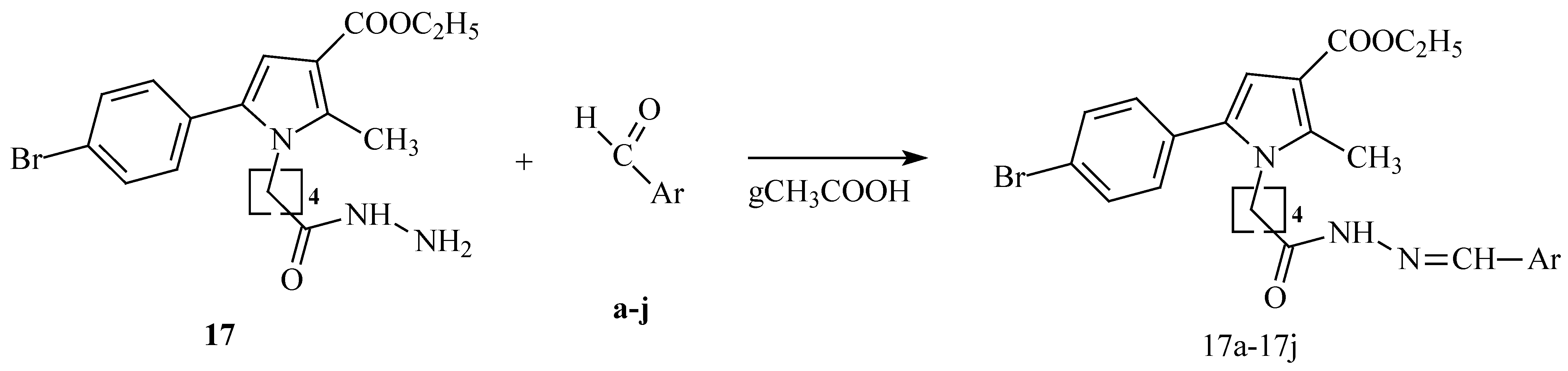

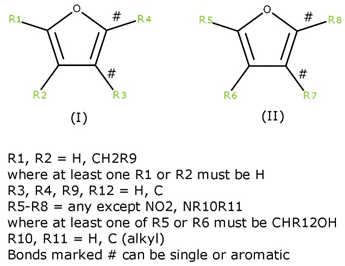

2.1. Synthesis of the Target Derivatives

2.2. Pharmacological In Vitro Assessment of the Target Pyrrole-Based Derivatives

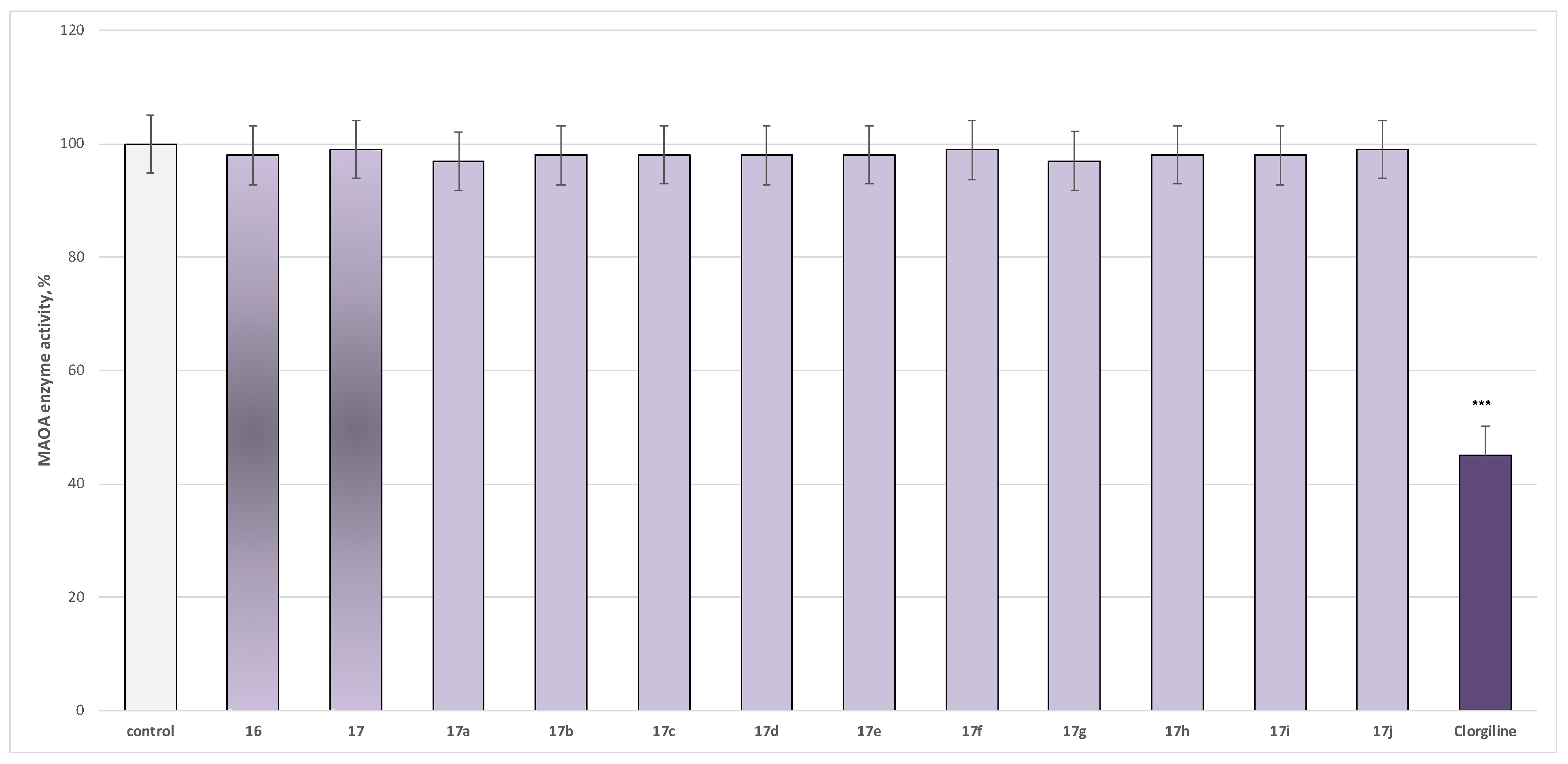

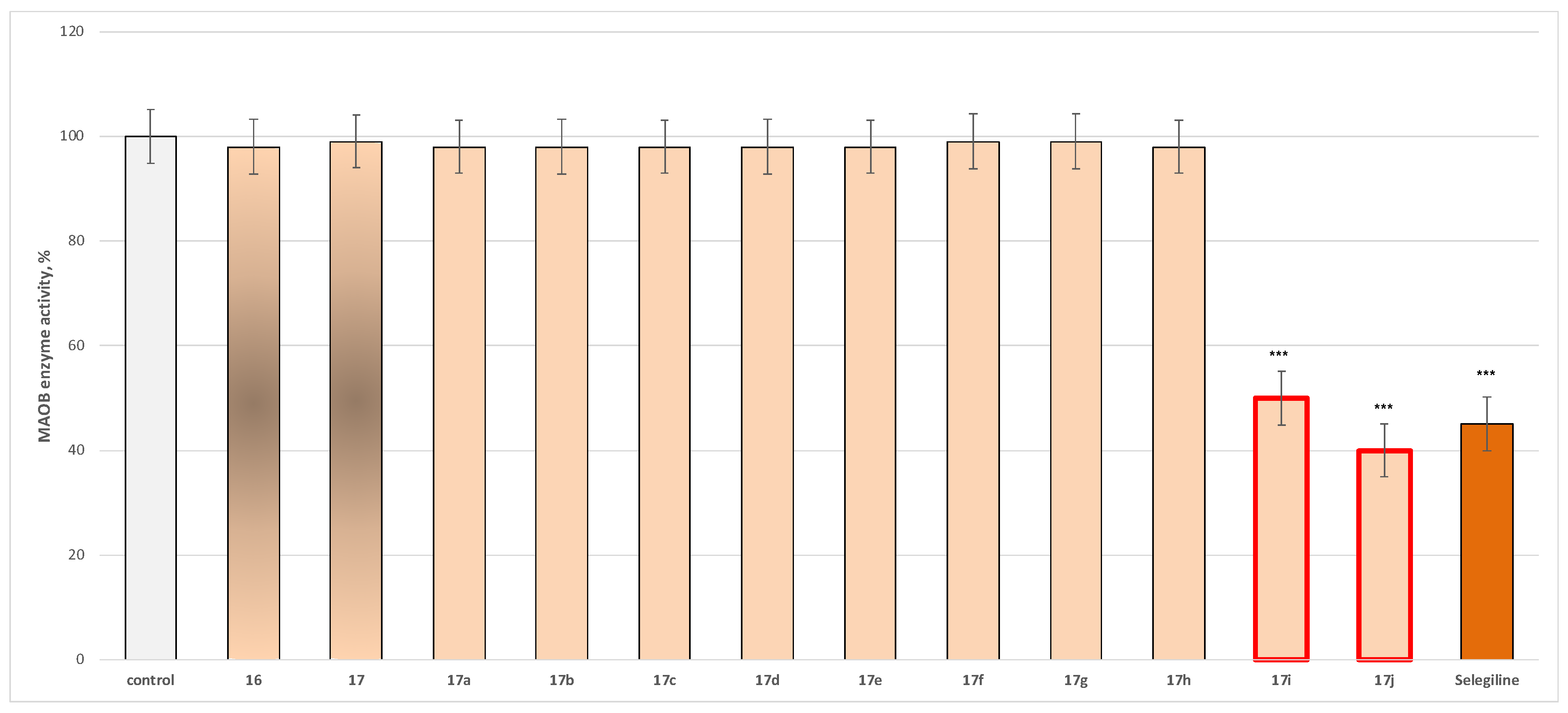

2.2.1. In Vitro Evaluation of MAO Inhibitory Activity

2.2.2. Neurotoxicity Determination

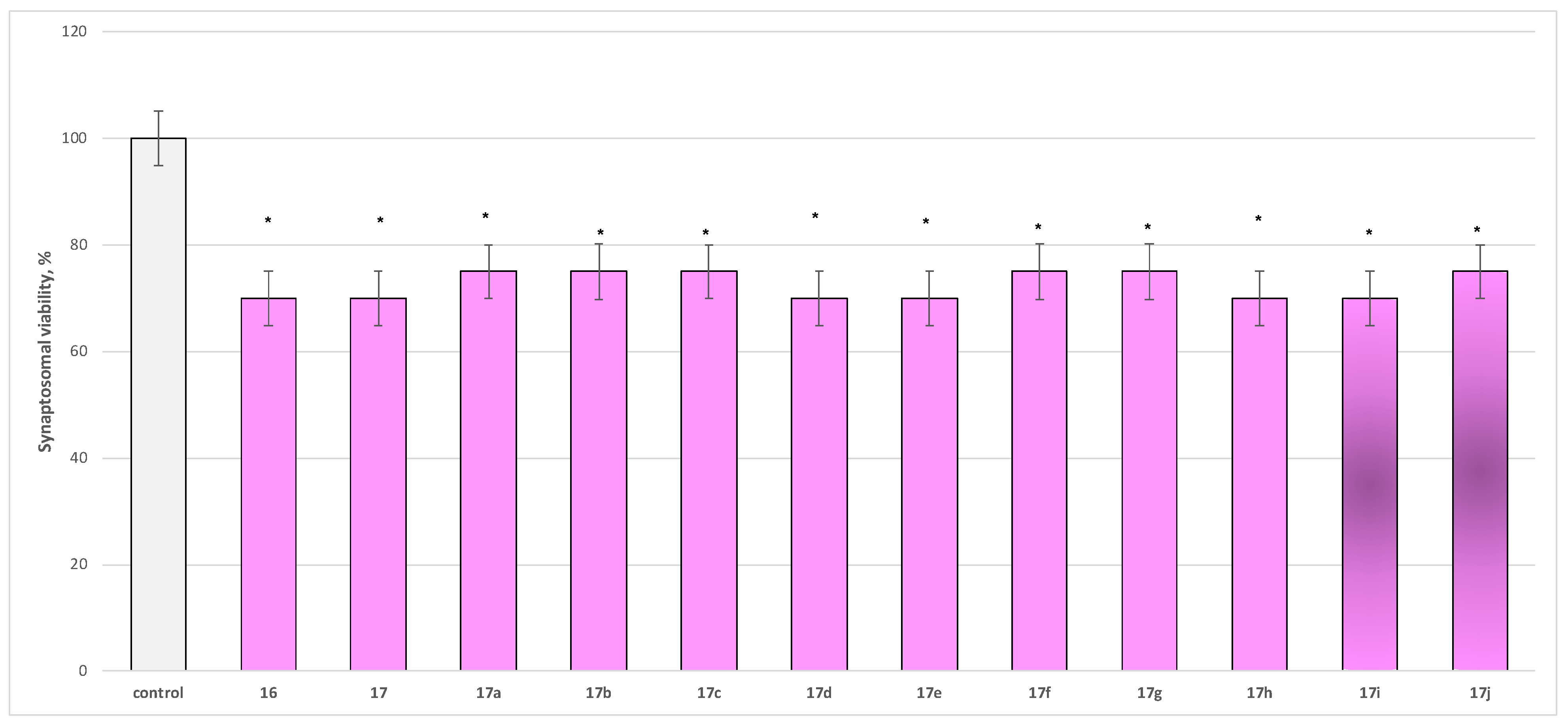

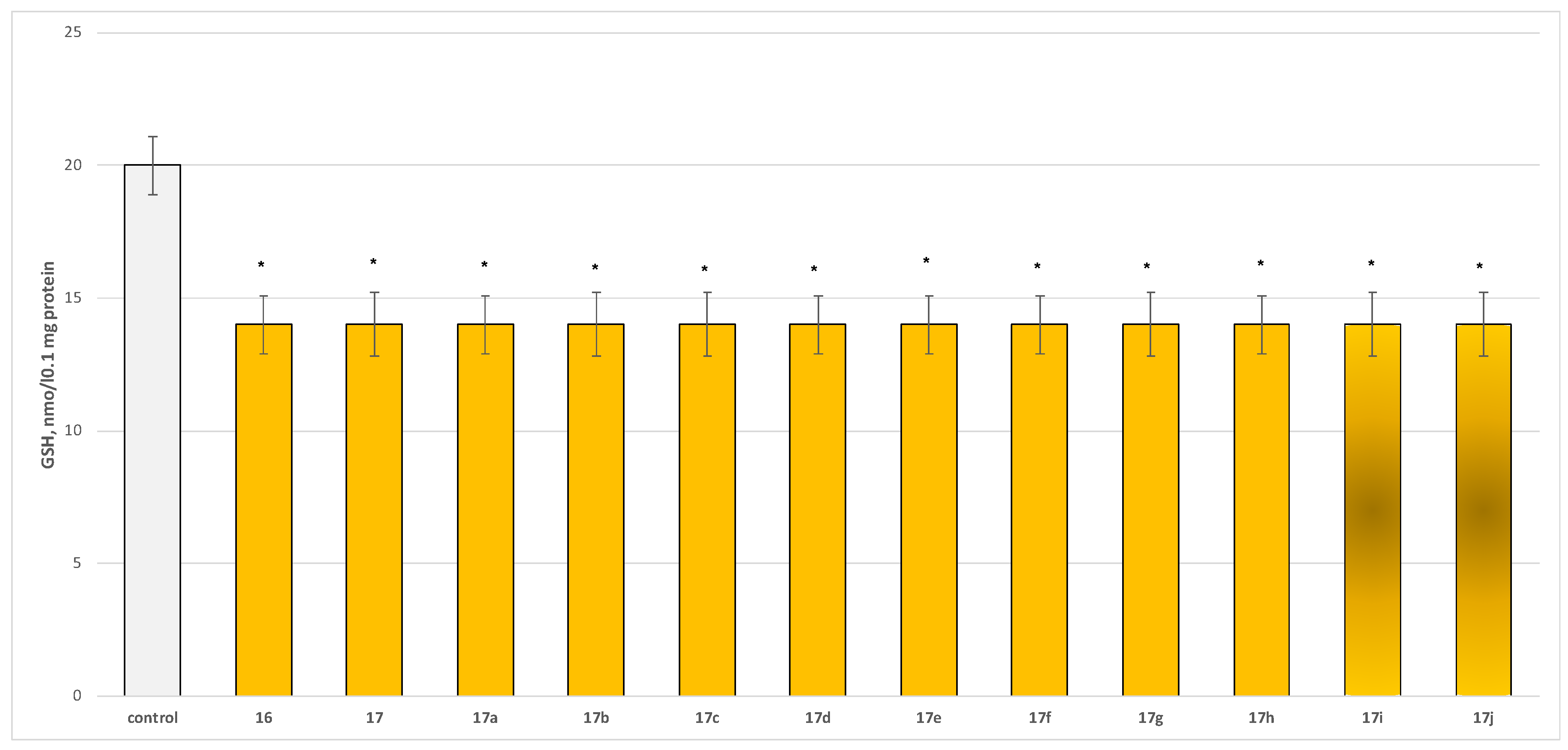

- Neurotoxicity determination of isolated rat brain synaptosomes

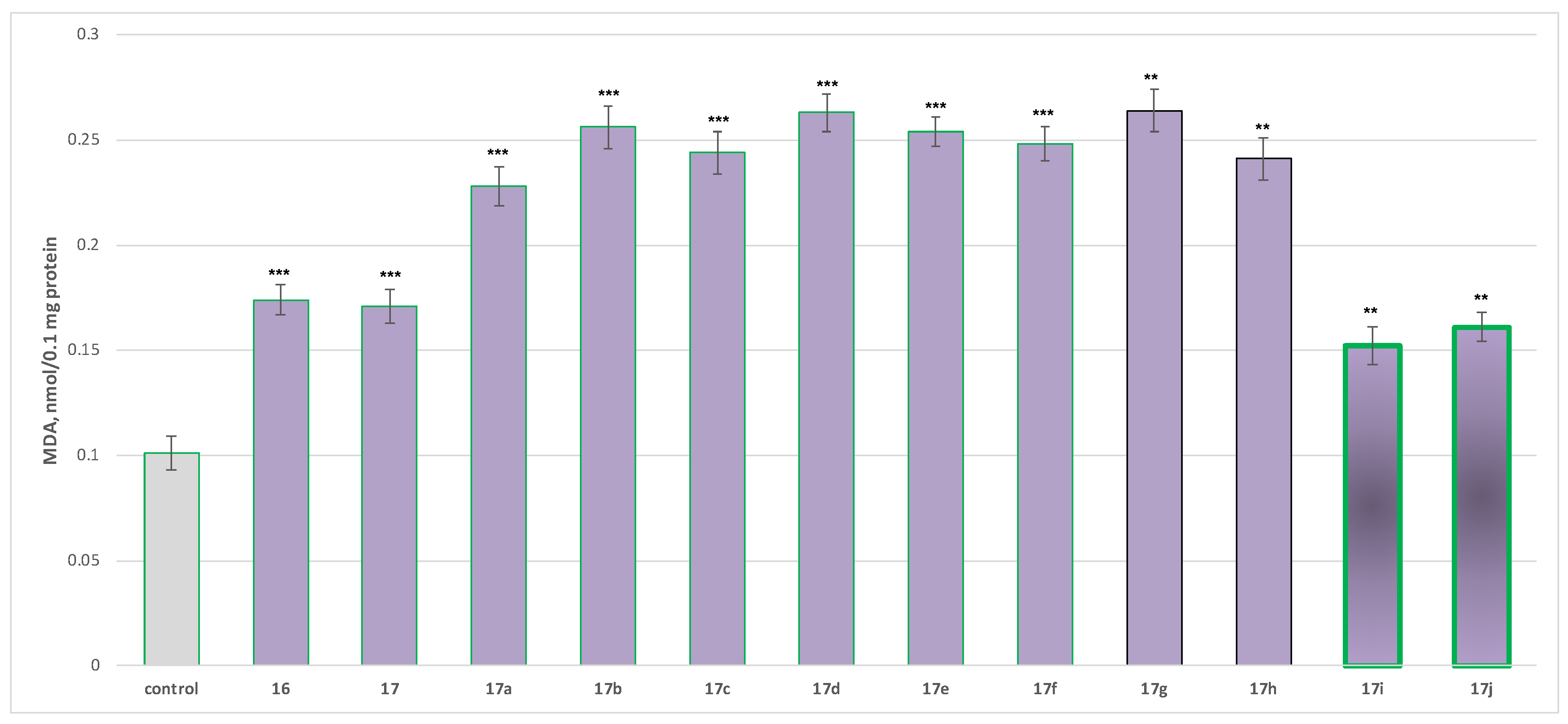

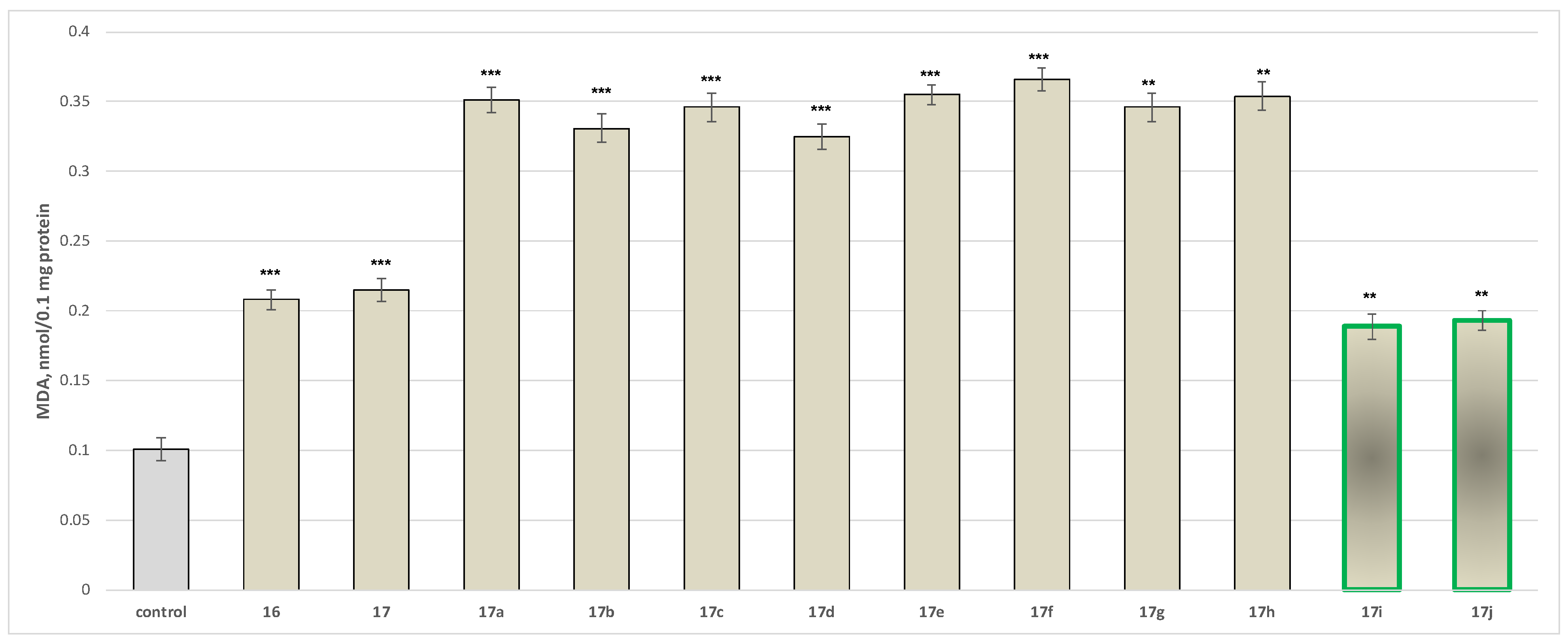

- Neurotoxicity determination of isolated rat brain mitochondria

- Neurotoxicity determination of isolated rat brain microsomes

2.2.3. Neuroprotective Properties

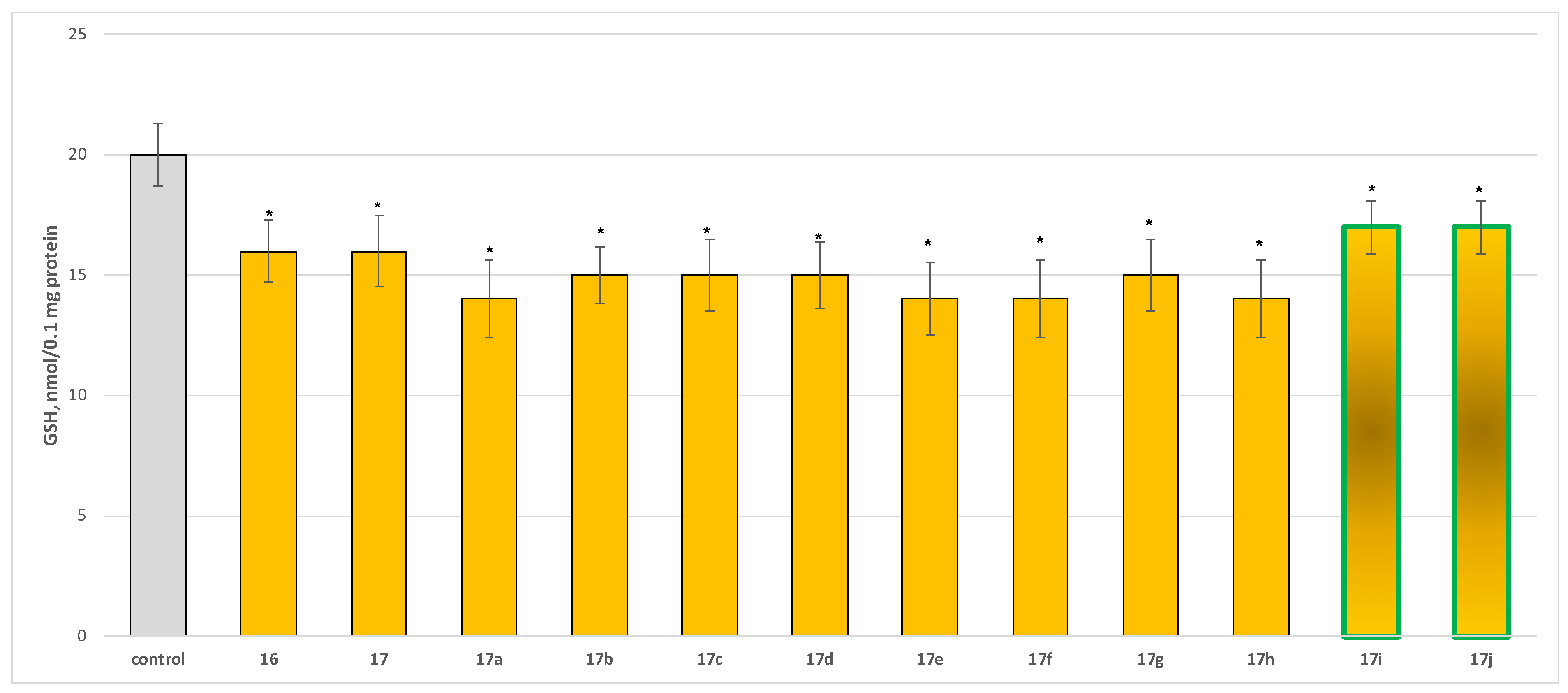

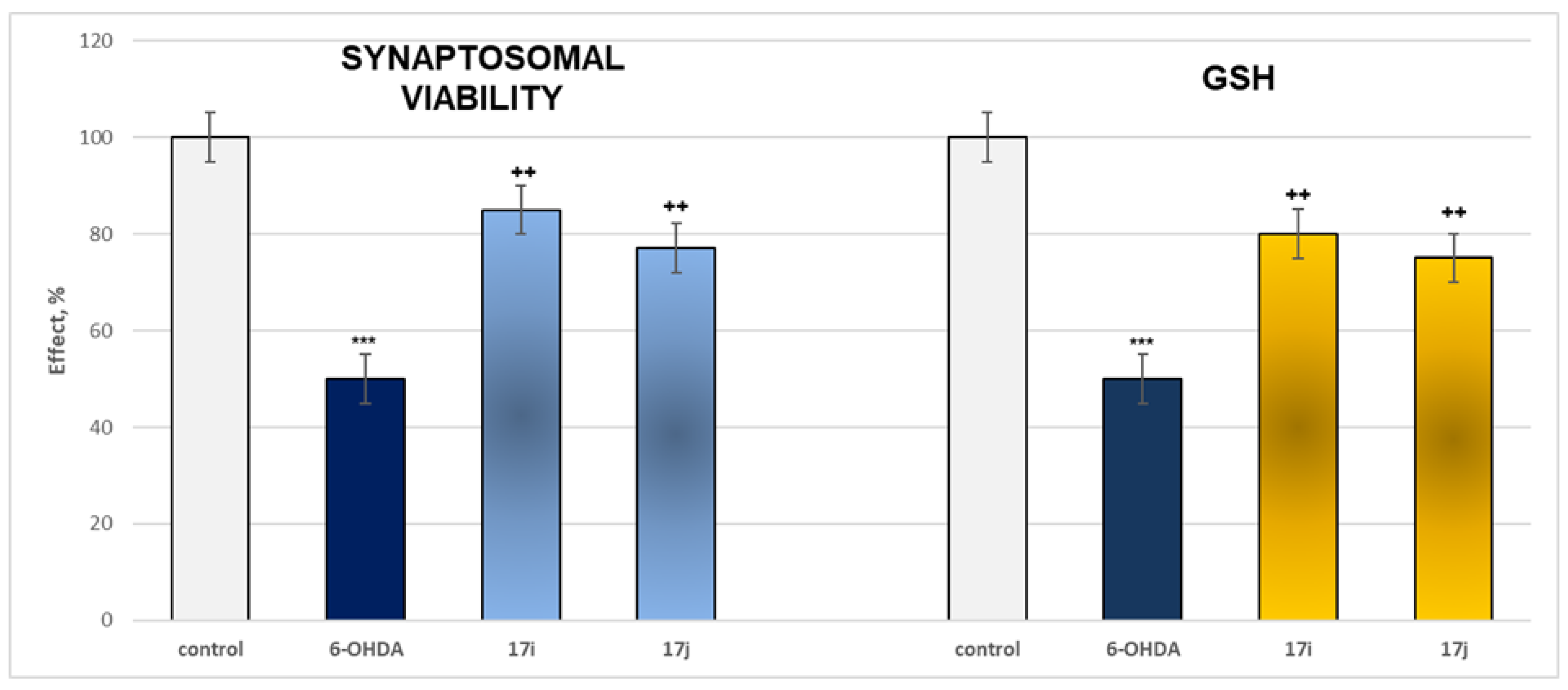

- Neuroprotection properties in isolated rat brain synaptosomes

- Neuroprotection properties in isolated rat brain mitochondria

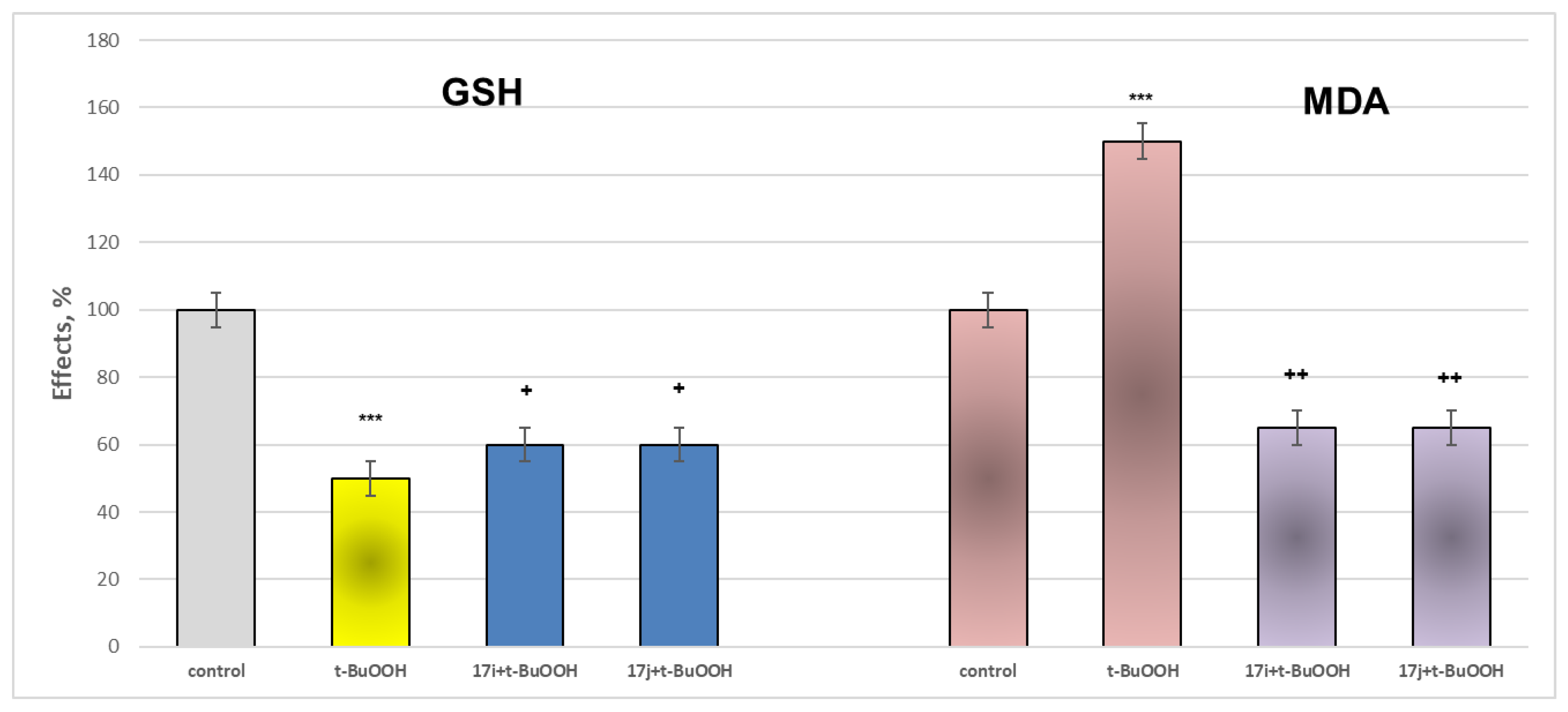

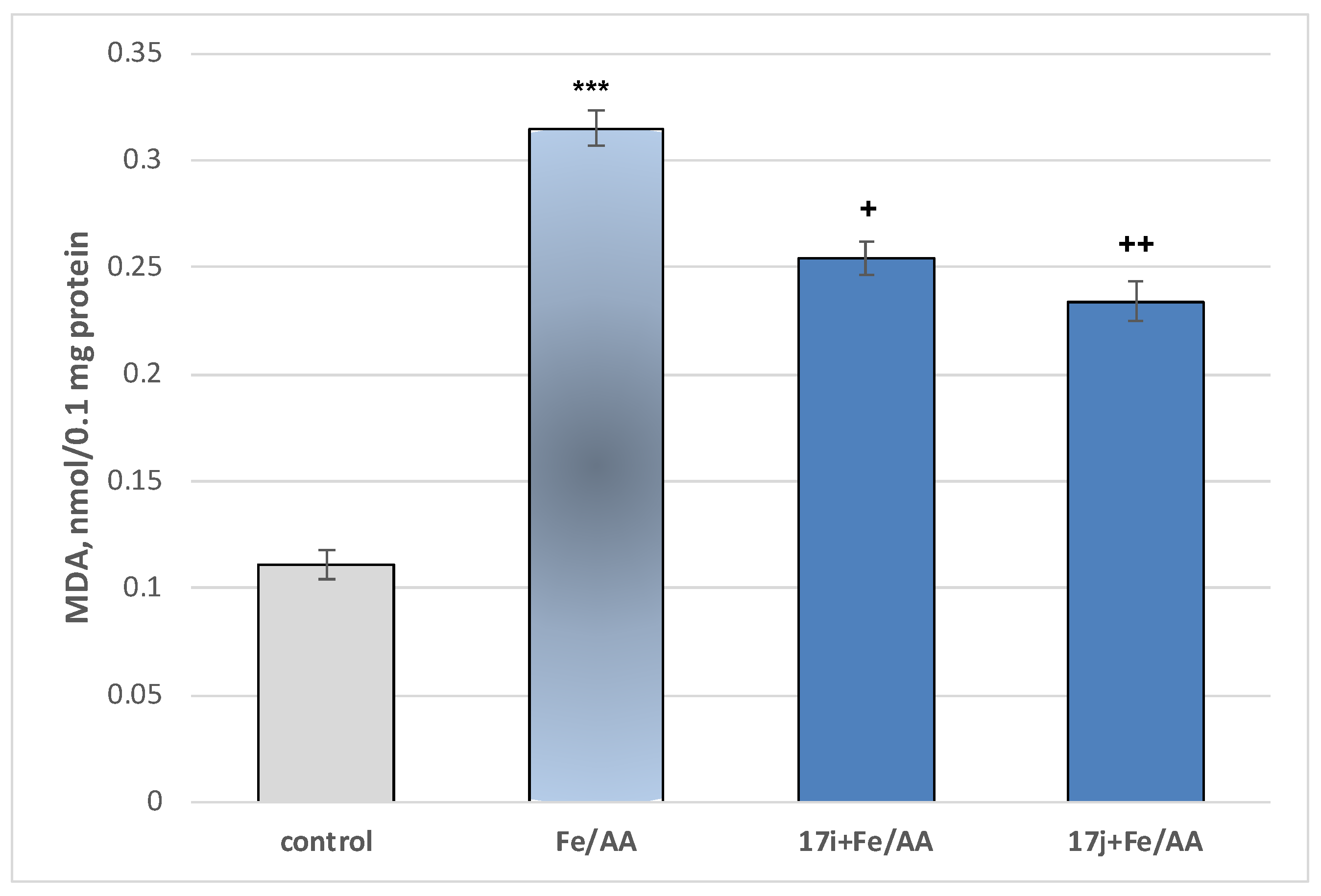

- Neuroprotection properties in isolated rat brain microsomes

2.3. In Silico Characterization

2.3.1. In Silico Assessment of the Possible Toxicity

2.3.2. In Silico Metabolic Profiling

3. Discussion

3.1. Chemistry

3.2. Pharmacological Studies

3.2.1. Evaluation of MAO Inhibitory Activity Through In Vitro Methodology

3.2.2. Neurotoxicity and Neuroprotection of the Target Azomethines in Brain Subcellular Fractions

3.3. In Silico Toxicity Assessment and Metabolic Profiling

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemistry

4.1.1. Synthesis of the Initial N-Pyrrolyl Carboxylic Acid 16

- 5-(5-(4-bromophenyl)-3-(ethoxycarbonyl)-2-methyl-1H-pyrrol-1-yl)pentanoic acid (16)

4.1.2. Synthesis of the Target Hydrazide 17

- ethyl 5-(4-bromophenyl)-1-(5-hydrazinyl-5-oxopentyl)-2-methyl-1H-pyrrole-3-carboxylate (17)

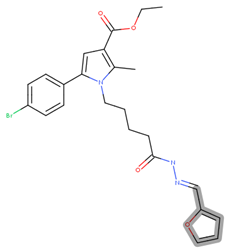

4.1.3. General Synthesis of the New Hydrazones 17a–17j

- ethyl 1-(5-(2-benzylidenehydrazinyl)-5-oxopentyl)-5-(4-bromophenyl)-2-methyl-1H-pyrrole-3-carboxylate (17a)

- ethyl 5-(4-bromophenyl)-1-(5-(2-(2-hydroxybenzylidene)hydrazinyl)-5-oxopentyl)-2-methyl-1H-pyrrole-3-carboxylate (17b)

- ethyl 5-(4-bromophenyl)-1-(5-(2-(2-fluorobenzylidene)hydrazinyl)-5-oxopentyl)-2-methyl-1H-pyrrole-3-carboxylate (17c)

- ethyl 5-(4-bromophenyl)-1-(5-(2-(3-fluorobenzylidene)hydrazinyl)-5-oxopentyl)-2-methyl-1H-pyrrole-3-carboxylate (17d)

- ethyl 5-(4-bromophenyl)-1-(5-(2-(4-methoxybenzylidene)hydrazinyl)-5-oxopentyl)-2-methyl-1H-pyrrole-3-carboxylate (17e)

- ethyl 5-(4-bromophenyl)-1-(5-(2-(4-(dimethylamino)benzylidene)hydrazinyl)-5-oxopentyl)-2-methyl-1H-pyrrole-3-carboxylate (17f)

- ethyl 5-(4-bromophenyl)-1-(5-(2-(3-formylbenzylidene)hydrazinyl)-5-oxopentyl)-2-methyl-1H-pyrrole-3-carboxylate (17g)

- ethyl 5-(4-bromophenyl)-2-methyl-1-(5-(2-((5-nitrofuran-2-yl)methylene) hydrazinyl)-5-oxopentyl)-1H-pyrrole-3-carboxylate (17h)

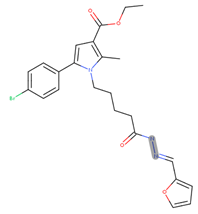

- ethyl 5-(4-bromophenyl)-1-(5-(2-(furan-2-ylmethylene)hydrazinyl)-5-oxopentyl)-2-methyl-1H-pyrrole-3-carboxylate (17i)

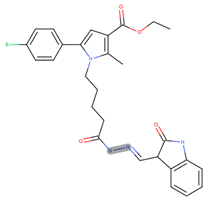

- ethyl 5-(4-bromophenyl)-2-methyl-1-(5-oxo-5-(2-((3-oxoindolin-2-yl)methylene) hydrazinyl)pentyl)-1H-pyrrole-3-carboxylate (17j)

4.2. Pharmacological In Vitro Evaluations

4.2.1. Determination of Human Recombinant MAO-A/B Enzyme Activity

4.2.2. Neurotoxicity and Neuroprotection Assessment

4.3. In Silico Toxicity Assessment

4.3.1. Software and Configuration

4.3.2. Compound Input and Preparation

4.3.3. Endpoint Evaluation

4.3.4. Metabolic Analysis

4.4. Statistical Methods

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shih, J.C. Monoamine oxidase isoenzymes: Genes, functions and targets for behavior and cancer therapy. J. Neural Transm. 2018, 125, 1553–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordio, G.; Piazzola, F.; Cozza, G.; Rossetto, M.; Cervelli, M.; Minarini, A.; Basagni, F.; Tassinari, E.; Dalla Via, L.; Milelli, A.; et al. From Monoamine Oxidase Inhibition to Antiproliferative Activity: New Biological Perspectives for Polyamine Analogs. Molecules 2023, 28, 6329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, J.; Meyer, J.H.; Furukawa, Y.; Boileau, I.; Chang, L.J.; Wilson, A.A.; Houle, S.; Kish, S.J. Distribution of monoamine oxidase proteins in human brain: Implications for brain imaging studies. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2013, 33, 863–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behl, T.; Kaur, D.; Sehgal, A.; Singh, S.; Sharma, N.; Zengin, G.; Andronie-Cioara, F.L.; Toma, M.M.; Bungau, S.; Bumbu, A.G. Role of Monoamine Oxidase Activity in Alzheimer’s Disease: An Insight into the Therapeutic Potential of Inhibitors. Molecules 2021, 26, 3724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carradori, S.; Fantacuzzi, M.; Ammazzalorso, A.; Angeli, A.; De Filippis, B.; Galati, S.; Petzer, A.; Petzer, J.P.; Poli, G.; Tuccinardi, T.; et al. Resveratrol Analogues as Dual Inhibitors of Monoamine Oxidase B and Carbonic Anhydrase VII: A New Multi-Target Combination for Neurodegenerative Diseases? Molecules 2022, 27, 7816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, M.A.; Saber-Ayad, M.M. MAO Inhibitors. In StatPearlsi; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ives, N.J.; Stowe, R.L.; Marro, J.; Counsell, C.; Macleod, A.; Clarke, C.E.; Gray, R.; Wheatley, K. Monoamine oxidase type B inhibitors in early Parkinson’s disease: Meta-analysis of 17 randomised trials involving 3525 patients. Br. Med. J. 2004, 329, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulcin, İ.; Petrova, O.V.; Taslimi, P.; Malysheva, S.F.; Schmidt, E.Y.; Sobenina, L.N.; Gusarova, N.K.; Trofimov, B.A.; Tuzun, B.; Farzaliyev, V.M.; et al. Synthesis, Characterization, Molecular Docking, Acetylcholinesterase and α-Glycosidase Inhibition Profiles of Nitrogen-Based Novel Heterocyclic Compounds. ChemistrySelect 2022, 7, e202200370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puranik, N.; Song, M. Therapeutic Role of Heterocyclic Compounds in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Insights from Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases. Neurol. Int. 2025, 17, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadam, M.; Jadhao, N.L.; Gajbhiye, J.M. Synthesis of pyrazole and 1,3,4-oxadiazole derivatives of pharmaceutical potential. Prospect. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 22, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pibiri, I. Recent Advances: Heterocycles in Drugs and Drug Discovery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, A.; Salahuddin, S.; Mazumder, A.; Kumar, R.; Jawed Ahsan, M.; Shahar Yar, M.; Maqsood, R.; Singh, K. Targeted Development of Pyrazoline Derivatives for Neurological Disorders: A Review. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, e202400738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, P.; Jesus, J.; Santos, S.; Raposo, L.R.; Roma-Rodrigues, C.; Baptista, P.V.; Fernandes, A.R. Heterocyclic Anticancer Compounds: Recent Advances and the Paradigm Shift towards the Use of Nanomedicine’s Tool Box. Molecules 2015, 20, 16852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, A.H.; Freeman, W.M.; Mitchell, S.G.; Burnette, T.A.; Hellmann, G.M.; Vrana, K.E. Induction of GADD45 and GADD153 in neuroblastoma cells by dopamine-induced toxicity. Neurotoxicology 2002, 23, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rynkowska, A.; Stępniak, J.; Karbownik-Lewińska, M. Fenton Reaction-Induced Oxidative Damage to Membrane Lipids and Protective Effects of 17β-Estradiol in Porcine Ovary and Thyroid Homogenates. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, J.; Emgard, M.; Brundin, P.; Burkitt, M. Trans-Resveratrol protects embryonic mesencephalic cells from tert-butyl hydroperoxide: Electron paramagnetic resonance spin trapping evidence for a rdical scavenging mechanism. J. Neurochem. 2000, 75, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drahota, Z.; Krivakova, P.; Cervinkova, Z.; Kmonickova, E.; Lotkova, H.; Kucera, O.; Houstek, J. Tert-butyl hydroperoxide selectively inhibits mitochondrial respiratory-chain enzymes in isolated rat hepatocytes. Physiol. Res. 2005, 54, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlede, E.; Aberer, W.; Fuchs, T.; Gerner, I.; Lessmann, H.; Maurer, T.; Rossbacher, R.; Stropp, G.; Wagner, E.; Kayser, D. Chemical substances and contact allergy—244 substances ranked according to allergenic potency. Toxicology 2003, 193, 219–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Furan. In IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans; International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC): Lyon, France, 1995; Volume 63. [Google Scholar]

- Bautista-Aguilera, O.M.; Esteban, G.; Bolea, I.; Nikolic, K.; Agbaba, D.; Moraleda, I.; Iriepa, I.; Samadi, A.; Soriano, E.; Unzeta, M.; et al. Design, synthesis, pharmacological evaluation, QSAR analysis, molecular modeling and ADMET of novel donepezil-indolyl hybrids as multipotent cholinesterase/monoamine oxidase inhibitors for the potential treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 21, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taupin, P.; Zini, S.; Cesselin, F.; Ben-Ari, Y.; Roisin, M.P. Subcellular fractionation on Percoll gradient of mossy fiber synaptosomes: Morphological and biochemical characterization in control and degranulated rat hippocampus. J. Neurochem. 1994, 62, 1586–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mungarro-Menchaca, X.; Ferrera, P.; Morán, J.; Arias, C. β-Amyloid peptide induces ultrastructural changes in synaptosomes and potentiates mitochondrial dysfunction in the presence of ryanodine. J. Neurosci. Res. 2002, 68, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robyt, J.F.; Ackerman, R.J.; Chittenden, C.G. Reaction of protein disulfide groups with Ellman’s reagent: A case study of the number of sulfhydryl and disulfide groups in Aspergillus oryzae α-amylase, papain, and lysozyme. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1971, 147, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirani, M.; Alizadeh, S.; Mahdavinia, M.; Dehghani, M.A. The ameliorative effect of quercetin on bisphenol A-induced toxicity in mitochondria isolated from rats. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 7688–7696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindranath, V.; Anandatheerthavarada, H.K. Preparation of brain microsomes with cytochrome P450 activity using calcium aggregation method. Anal. Biochem. 1990, 187, 310–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansuy, D.; Sassi, A.; Dansette, P.M.; Plat, M. A new potent inhibitor of lipid peroxidation in vitro and in vivo, the hepatoprotective drug anisyldithiolthione. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1986, 135, 1015–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ID | m.p. °C | Rf | MS Data [M+H]+ (m/z) | Yields % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | 90.3–92.1 | 0.65 | 408.29 | 86 |

| 17 | 97.3–102.2 | 0.73 | 422.32 | 83 |

| 17a | 121.8–123.4 | 0.79 | 510.43 | 88 |

| 17b | 122.2–125.7 | 0.71 | 526.43 | 84 |

| 17c | 127.8–131.2 | 0.73 | 528.42 | 81 |

| 17d | 126.4–130.3 | 0.53 | 528.42 | 80 |

| 17e | 157.6–158.9 | 0.75 | 540.46 | 72 |

| 17f | 138.7–140.2 | 0.62 | 545.39 | 52 |

| 17g | 166.2–168.1 | 0.67 | 553.50 | 64 |

| 17h | 99.2–103.3 | 0.50 | 500.39 | 74 |

| 17i | 144.5–147.3 | 0.68 | 538.44 | 72 |

| 17j | 95.4–96.3 | 0.30 | 551.44 | 78 |

| Compounds | IC50 (EC50), (µM ± SD) hMAO-A | IC50 (EC50), (µM ± SD) hMAO-B | SI |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5i | >100 | 0.712 ± 0.19 | >140 |

| 5j | >100 | 0.444 ± 0.12 | >225 |

| Selegiline | - | 0.318 ± 0.18 | |

| Clorgiline | 18.74 ± 0.096 | - |

| Endpoint | Toxicity Allert |

|---|---|

| 5alpha-reductase inhibition | Mutagenicity in vivo |

| Adrenal gland toxicity | Nephrotoxicit |

| Anaphylaxis | Neurotoxicity |

| Androgen receptor modulation | Non-specific genotoxicity in vitro |

| Bladder disorders | Non-specific genotoxicity in vivo |

| Bladder urothelial hyperplasia | Occupational asthma |

| Blood in urine | Ocular toxicity |

| Bone marrow toxicity | Oestrogen receptor modulation |

| Bradycardia | Oestrogenicity |

| Cardiotoxicity | Peroxisome proliferation |

| Cerebral oedema | Phospholipidosis |

| Chloracne | Photo-induced chromosome damage |

| Cholinesterase inhibition | Photo-induced non-specific genotoxicity |

| Chromosome damage in vitro | Photo-induced non-specific genotoxicity |

| Chromosome damage in vivo | Photoallergenicity |

| Cumulative effect on white cell count and immunology | Photocarcinogenicity |

| Cyanide-type effects | Photomutagenicity in vitro |

| Developmental toxicity | Phototoxicity |

| Glucocorticoid receptor agonism | Pulmonary toxicity |

| HERG channel inhibition in vitro | Respiratory sensitisation |

| High acute toxicity | Skin irritation/corrosion |

| Irritation (of the eye) | Skin sensitisation HPC |

| Irritation (of the gastrointestinal tract) | Splenotoxicity |

| Irritation (of the respiratory tract) | Teratogenicity |

| Kidney disorders | Testicular toxicity |

| Kidney function-related toxicity | Thyroid toxicity |

| Lachrymation | Uncoupler of oxidative phosphorylation |

| Methaemoglobinaemia | Urolithiasis |

| Mitochondrial dysfunction |

| Alert Description | Match with Query Compounds |

|---|---|

|  |

|

| Alert Description | Match with 17i |

|---|---|

|  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Georgieva, M.; Sharkov, M.; Mateev, E.; Mateeva, A.; Kondeva-Burdina, M. Evaluation of Pyrrole Heterocyclic Derivatives as Selective MAO-B Inhibitors and Neuroprotectors. Molecules 2026, 31, 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010186

Georgieva M, Sharkov M, Mateev E, Mateeva A, Kondeva-Burdina M. Evaluation of Pyrrole Heterocyclic Derivatives as Selective MAO-B Inhibitors and Neuroprotectors. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):186. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010186

Chicago/Turabian StyleGeorgieva, Maya, Martin Sharkov, Emilio Mateev, Alexandrina Mateeva, and Magdalena Kondeva-Burdina. 2026. "Evaluation of Pyrrole Heterocyclic Derivatives as Selective MAO-B Inhibitors and Neuroprotectors" Molecules 31, no. 1: 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010186

APA StyleGeorgieva, M., Sharkov, M., Mateev, E., Mateeva, A., & Kondeva-Burdina, M. (2026). Evaluation of Pyrrole Heterocyclic Derivatives as Selective MAO-B Inhibitors and Neuroprotectors. Molecules, 31(1), 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010186