Oxime Esters as Efficient Initiators in Photopolymerization Processes

Abstract

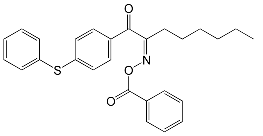

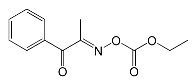

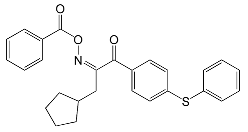

1. Characteristics of the Group

- (1)

- Their potential for use in material jetting technology has been investigated. This technology offers many advantages (for example, high printing resolution), but the main problem is oxygen inhibition. The publication not only proved the possibility of using oxime esters, but also obtained (by studying the kinetics of photopolymerization) higher monomer conversion rates, FC = 80% for Omnirad 1316 compared to the commercially used BAPO (phenylbis(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl)phosphine oxide), where the monomer conversion rate was at the level of 60% [19].

- (2)

- (3)

- From the perspective of photopolymerization, the degree of monomer conversion itself is also significant. Many studies demonstrate that oxime esters enable high monomer conversion.

2. Application of Oxime Esters as Photoinitiators

- Type I, which decays directly upon absorption of light. Radical pairs are generated through a highly efficient α-cleavage process;

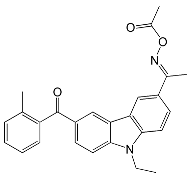

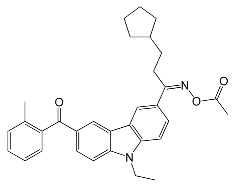

2.1. Carbazole-Based Oxime Esters

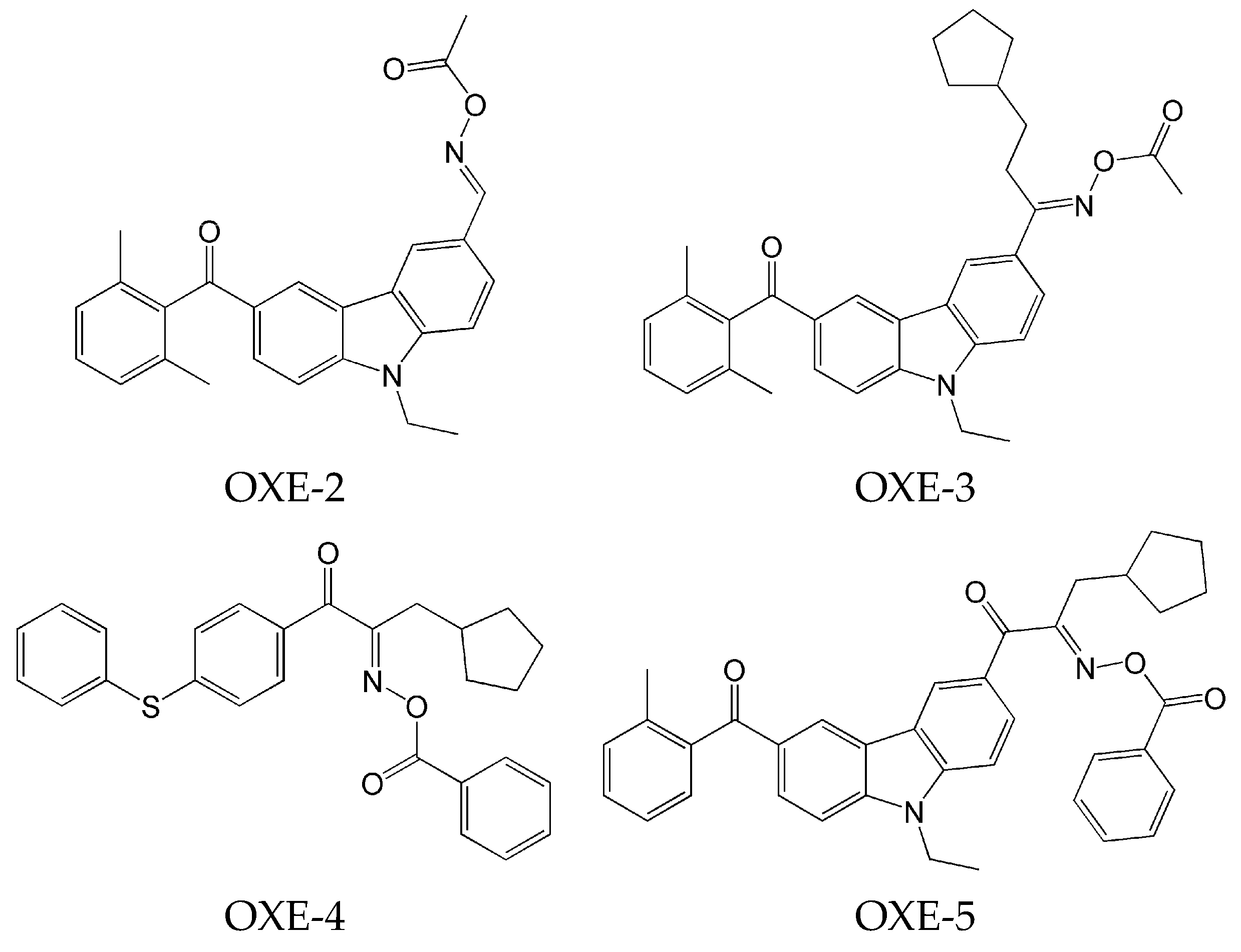

- the effect of various photoinitiators on polymerization. The use of OXE-3, OXE-4, and OXE-5 results in higher HDDA conversion (96%) compared to OXE-2, where the conversion was approximately 90%;

- the effect of the concentration of photoinitiator on polymerization. It was tested at five concentrations of OXE-4 (0.1 wt%, 0.3 wt%, 0.5 wt%, 0.8 wt%, and 1.0 wt%). The optimal concentration was determined to be 0.5 wt%. Increasing the concentration of this photoinitiator to this level increased the polymerization rate. Above this point, the rate of polymerization began to decrease;

- the effect of light intensity on polymerization. It was determined by study of the influence of four light intensities (10 mW·cm−2, 30 mW·cm−2, 50 mW·cm−2, and 80 mW·cm−2) on the photoinitiating ability of OXE-3 with a concentration of 0.3 wt%. An increase in light intensity from 10 to 50 mW·cm−2 resulted in a threefold increase in the polymerization rate. At a light intensity of 80 mW·cm−2, both the rate of polymerization and conversion slightly decreased;

- the effect of the type of monomers on polymerization. It was evaluated by photopolymerization of monomers (HDDA, TPGDA, TMPTA, and TMPTMA) in the presence of OXE-5 at a concentration of 0.3 wt%. Higher conversion rates were observed with difunctional monomers.

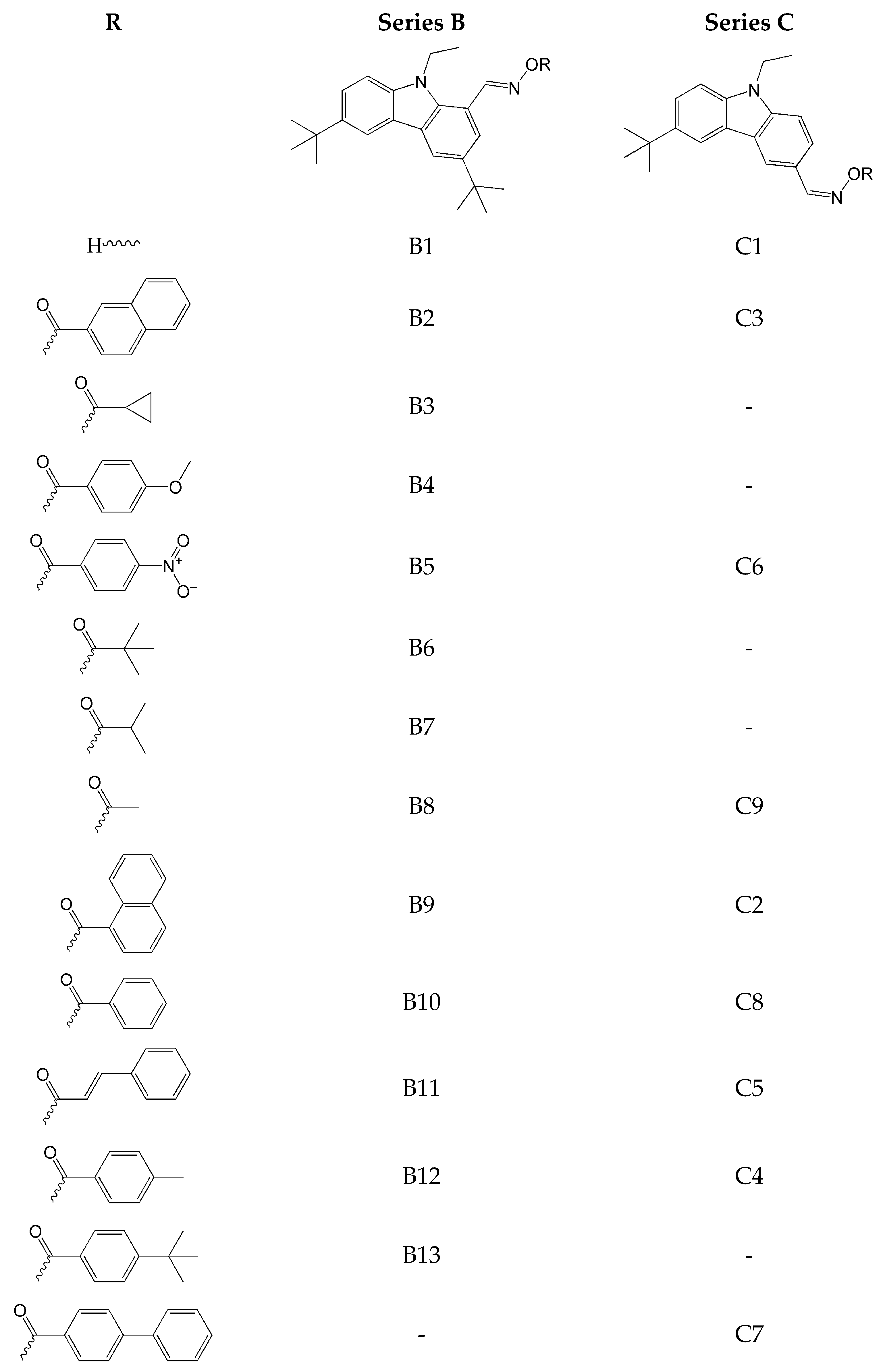

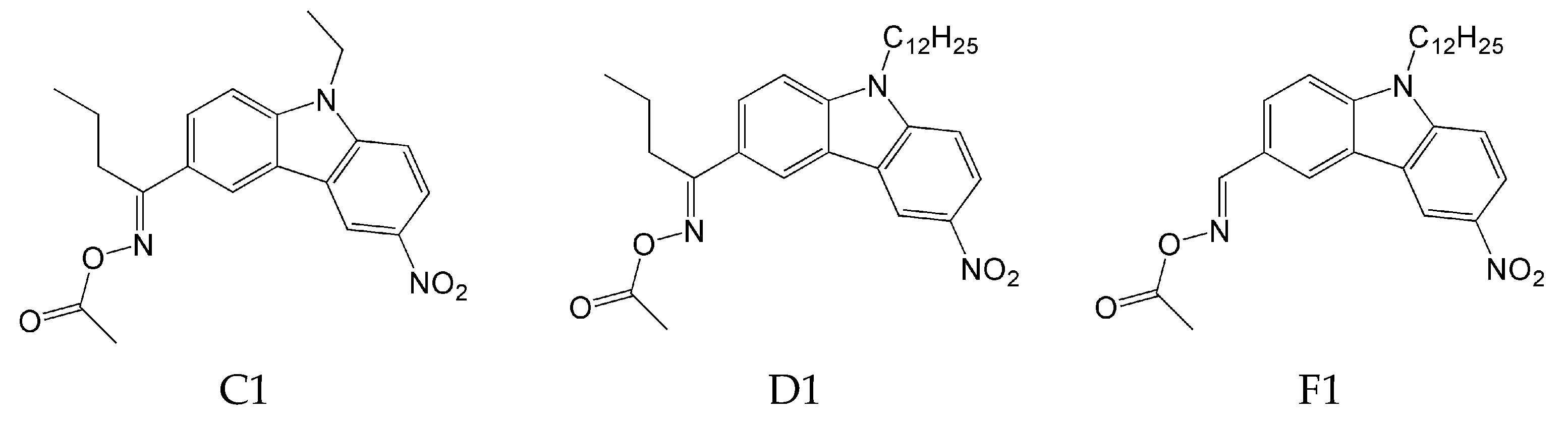

- The introduction of an oxime-ester group affects photoinitiation performance. Compounds without the oxime-ester group showed low photoinitiation ability. For example, compounds with the -OH group exhibited final conversion of monomer (FC) from 23% to 38%, in comparison to compositions with oxime esters, where FC values ranged from 38% to 68%;

- the type of substituent in OXE affects the degree of monomer conversion. Compounds with a methyl group demonstrated better photoinitiation ability compared to other compounds of the same series. The use of C1, D1, or F1 results in higher TMPTA conversion than with commercially available TPO. The chemical structures of the oxime esters with the best conversion results are shown in Figure 5.

- the increase in concentration of oxime ester results in an increase in the final conversion of TMPTA.

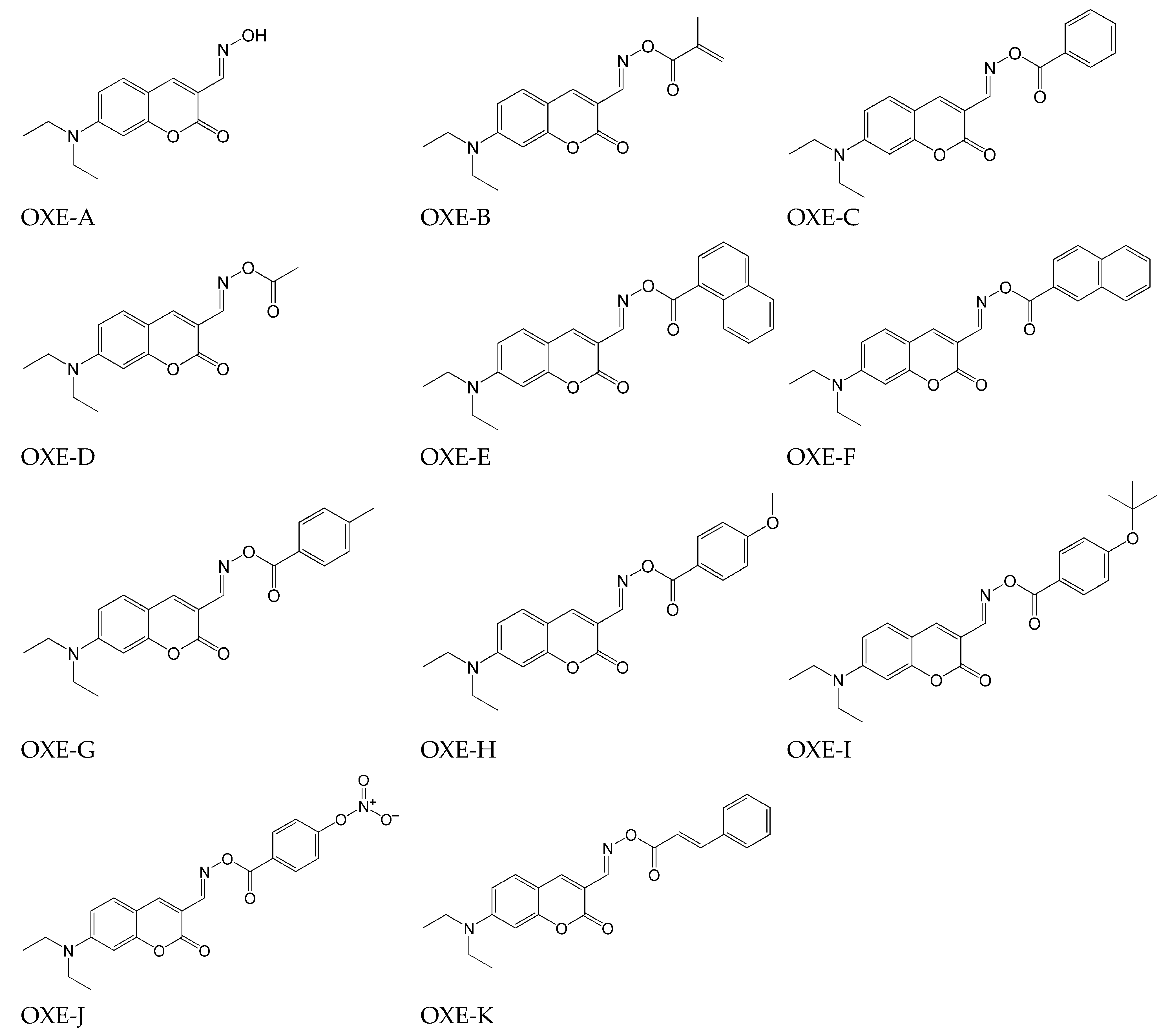

2.2. Coumarin-Based Oxime Esters

- the option of being called bio-sourced molecules. Substances of natural origin have recently been gaining increasing interest [66];

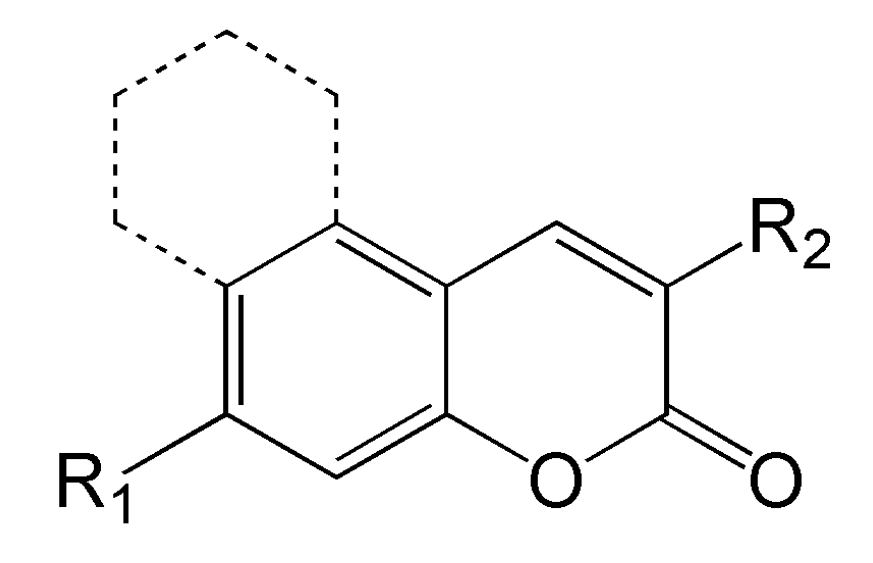

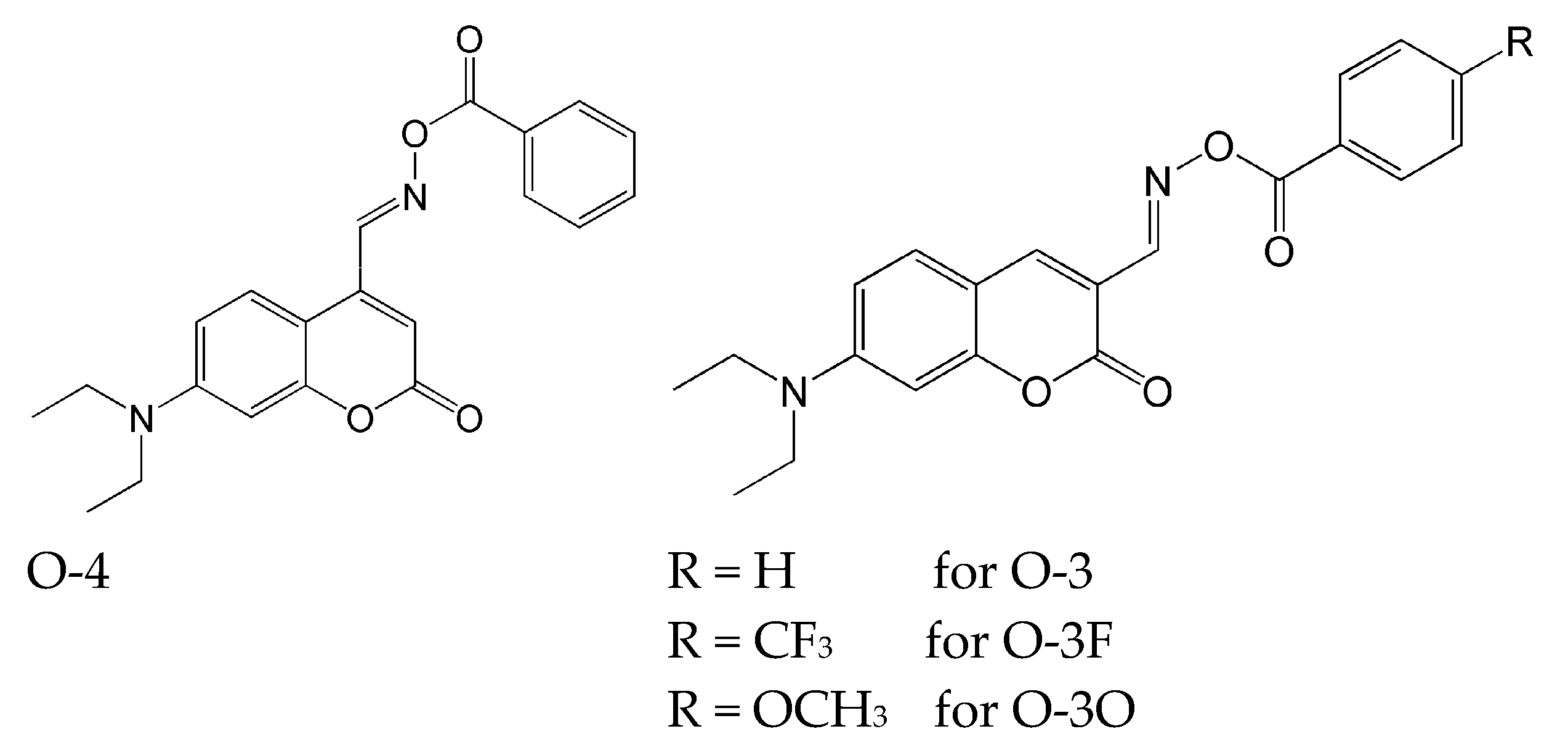

- the chemical structure that allows a wide range of modification. Figure 6 depicts the chemical structure of coumarins. Possible modification allows on, i.e., (1) in position R1 for tuning of the solubility, and (2) in position R2, also tuning of the solubility and introduction of the type I moiety [67];

- The possibility of using them as both type I and type II photoinitiators.

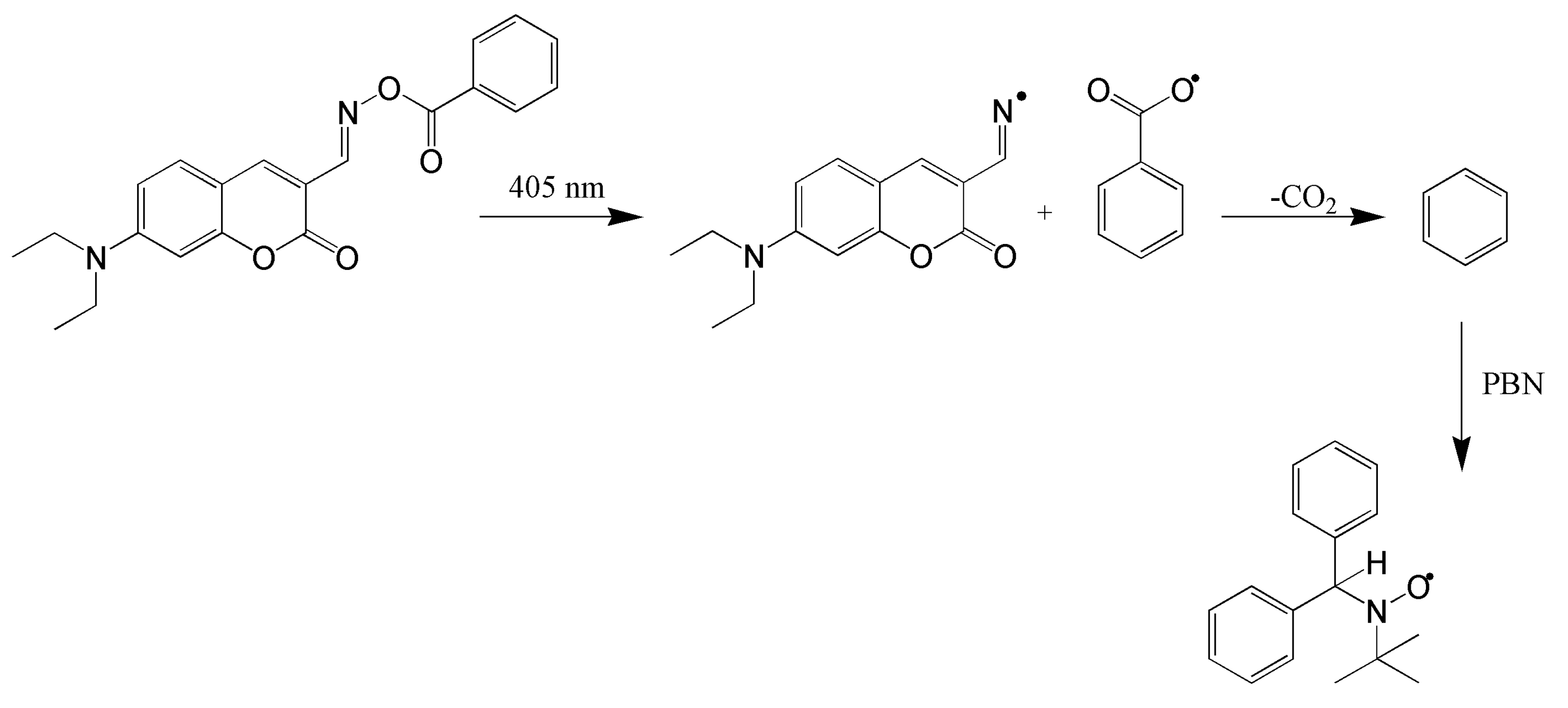

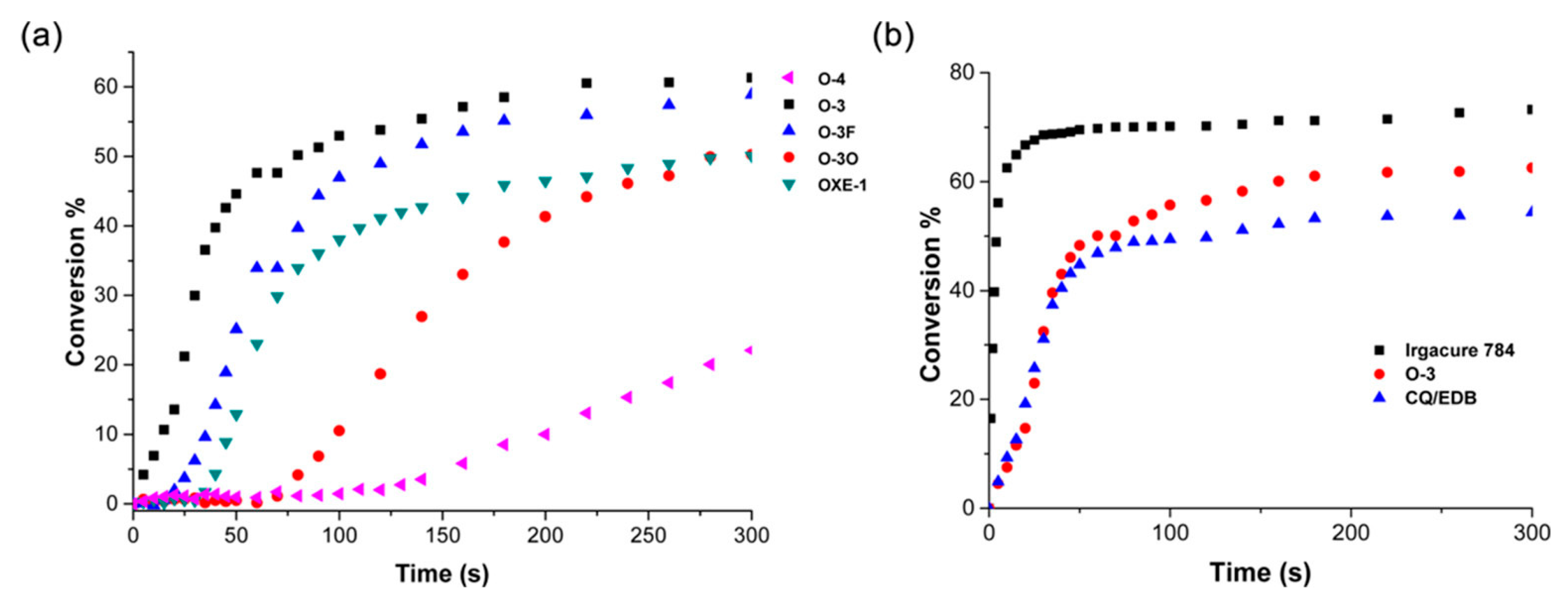

- O-4: the initial exposure to the light caused a slight shift of the maximum of absorption to red light, and the absorbance increased. Further irradiation causes the absorption maximum to shift slightly to blue light, and a slight decrease in the corresponding absorption was observed.

- O-3, O-3F and O-3O: where the maximum absorption decreased with the light exposure. After 10 min, a loss of yellow colour was observed.

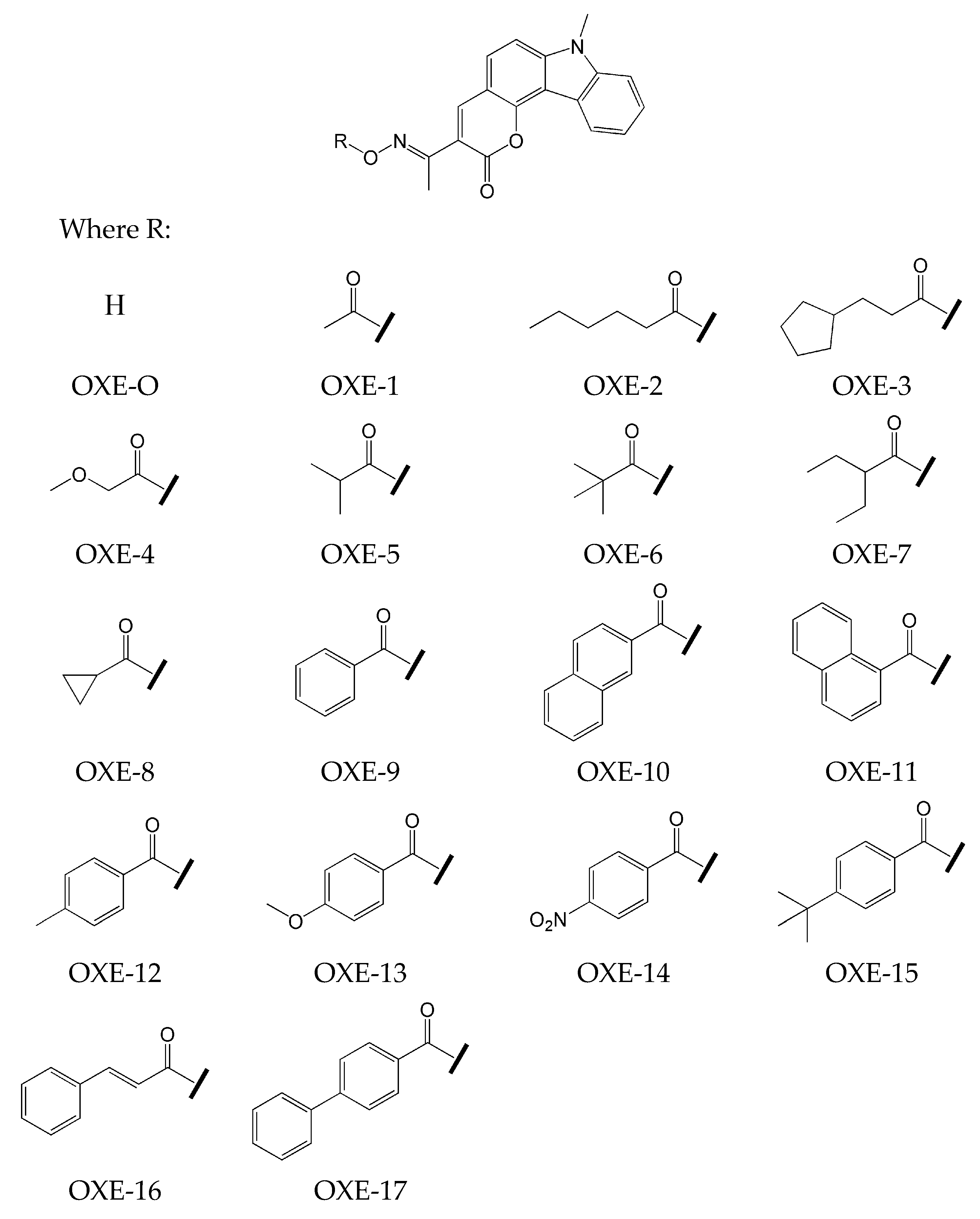

2.3. Carbazole-Coumarin-Based Oxime Esters

- oxime esters OXE-1, OXE-2, OXE-5, and OXE-7 showed higher conversion of monomer (about 67%) than the commercially available photoinitiator TPO (FC = 63%) (TMPTA) (concentration of photoinitiator was 2 × 10−5 mol/g).

- the highest rates of polymerization were achieved for OXE-1, OXE-2, OXE-5, OXE-7, and OXE-12, where the values of Rp/[M0] × 100 were 5.6 s−1, 6.9 s−1, 5.9 s−1, 6.5 s−1, and 8.9 s−1, respectively.

- for OXE-1 with TMPTA—15.4%; with Ebecryl605 52%;

- For OXE-5 with TMPTA—9.2%; with Ebecryl605 44.5%.

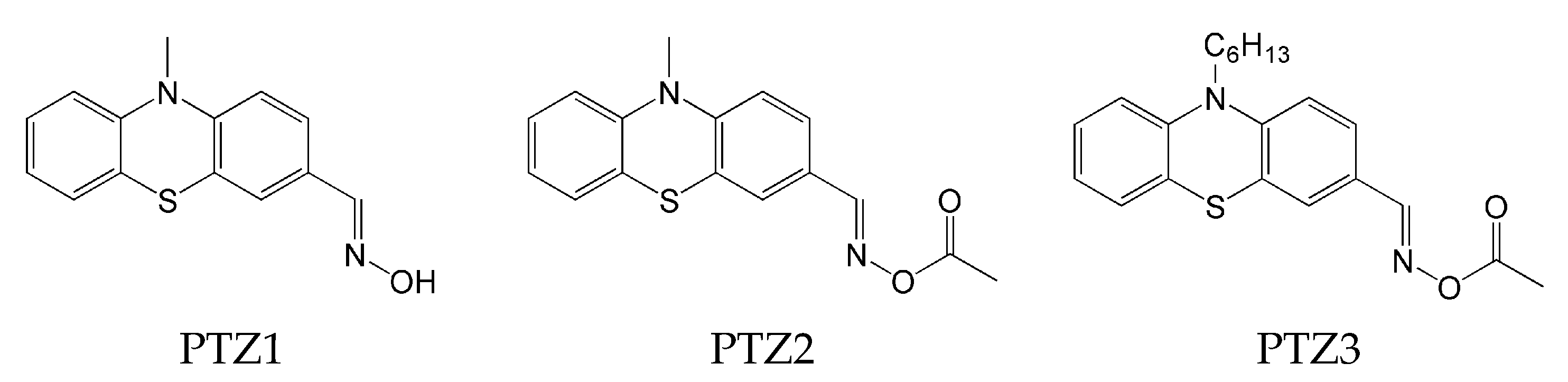

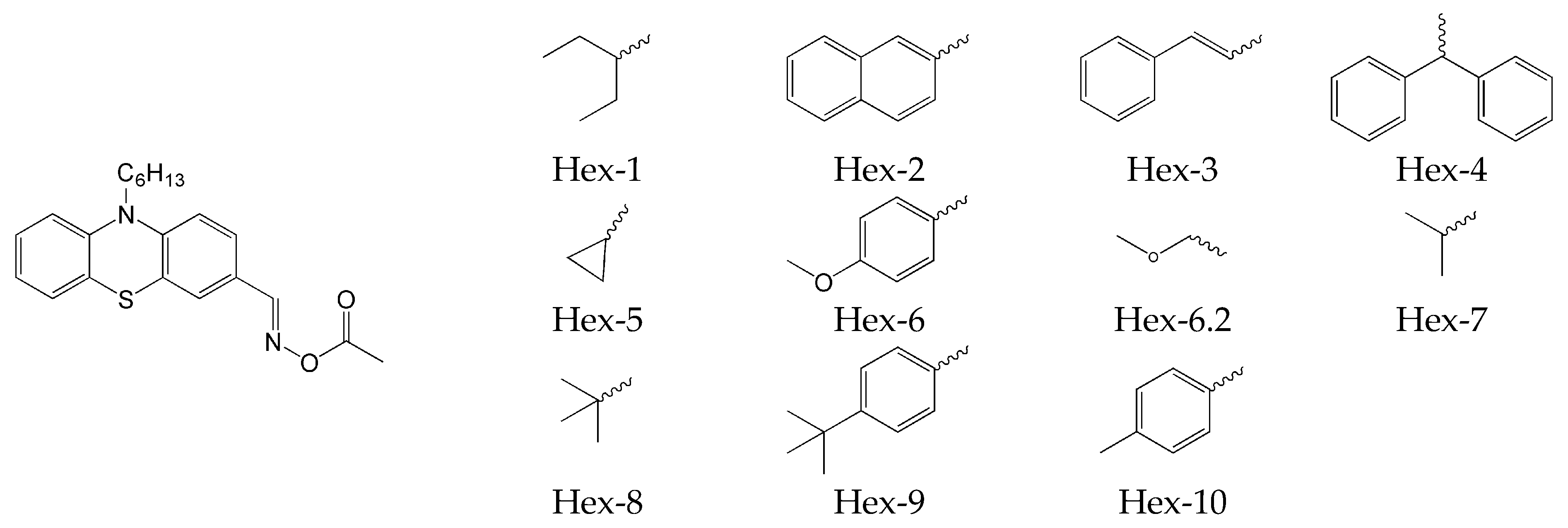

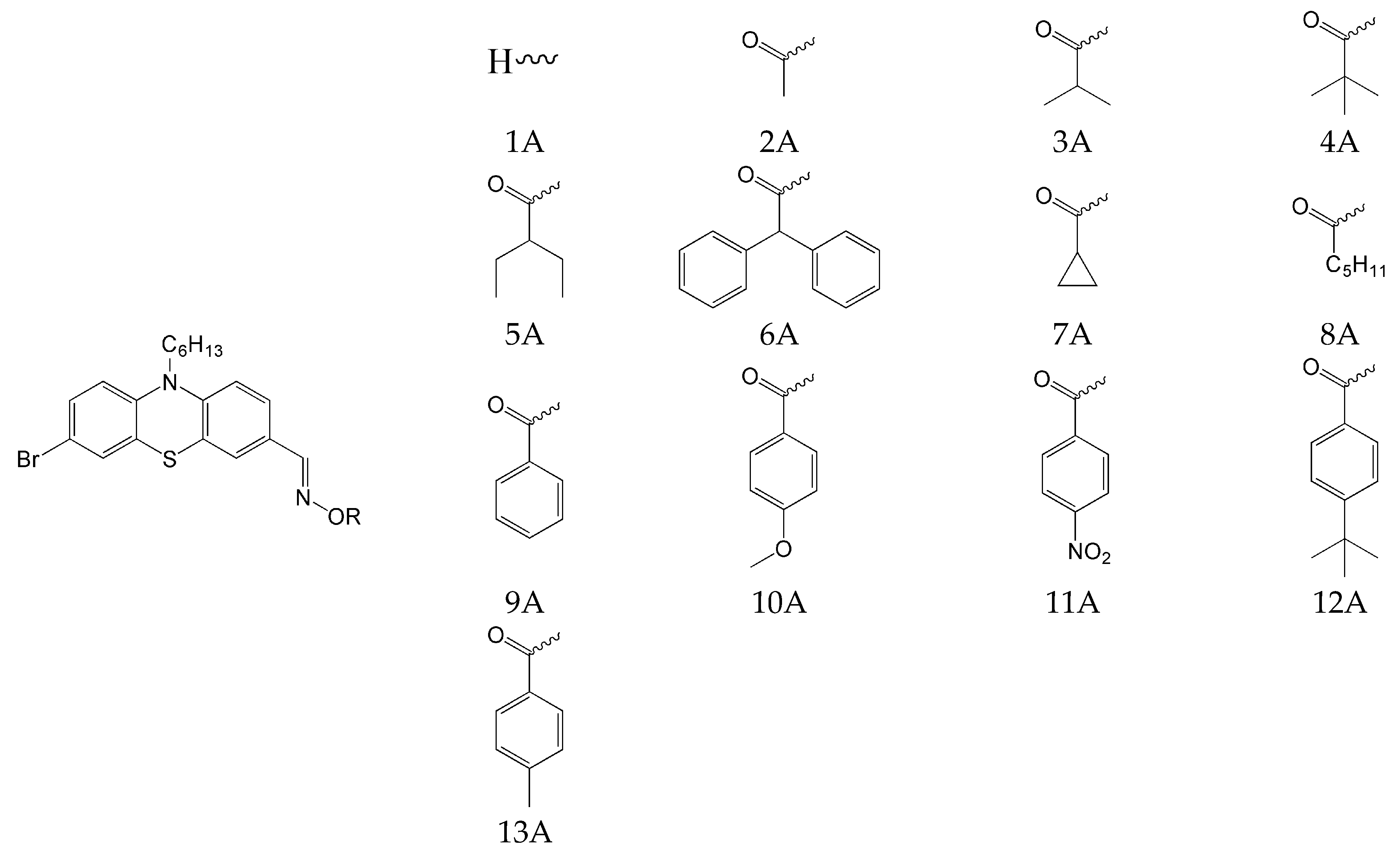

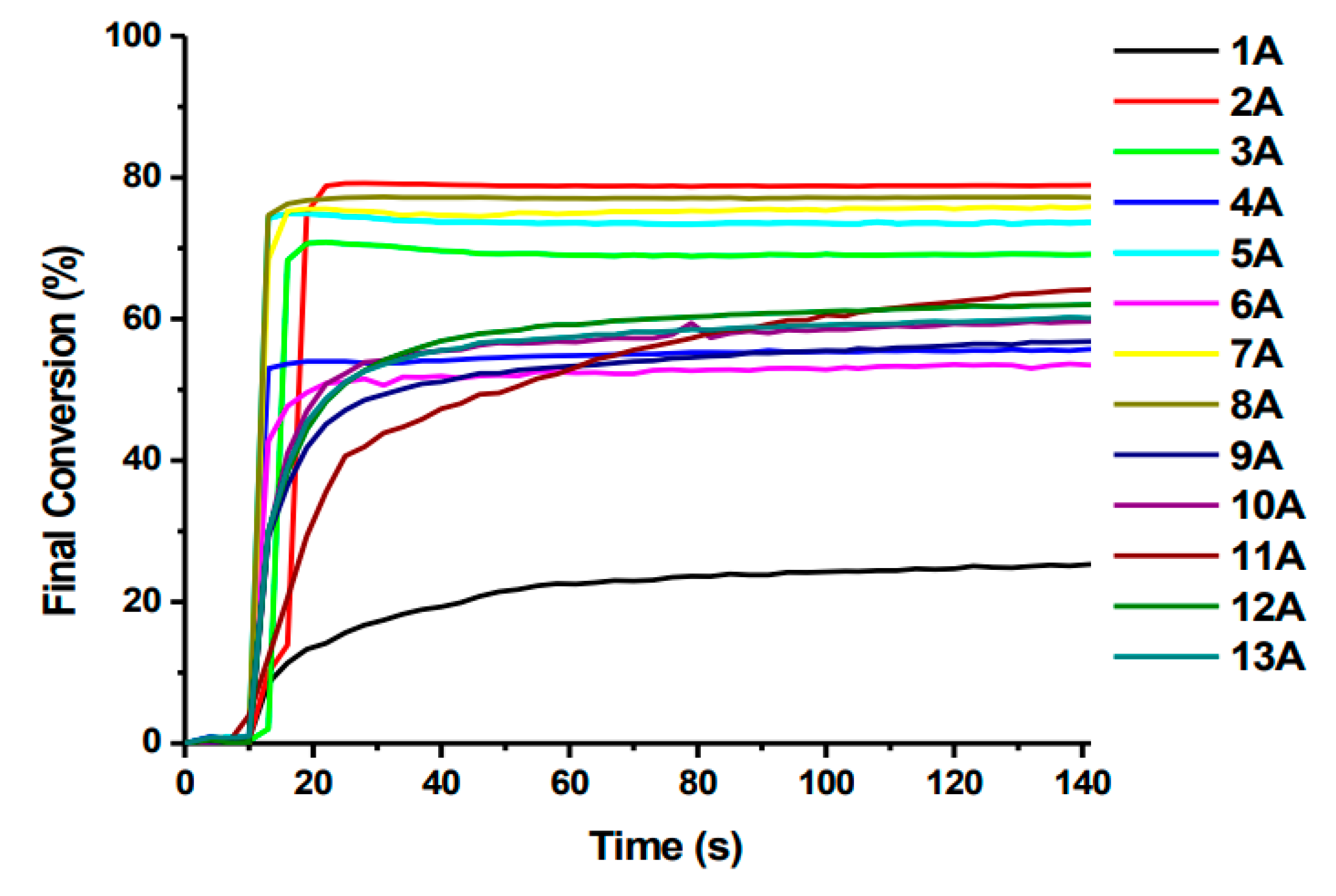

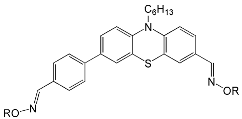

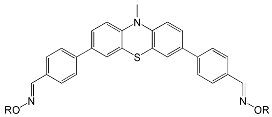

2.4. Phenothiazine-Based Oxime Esters

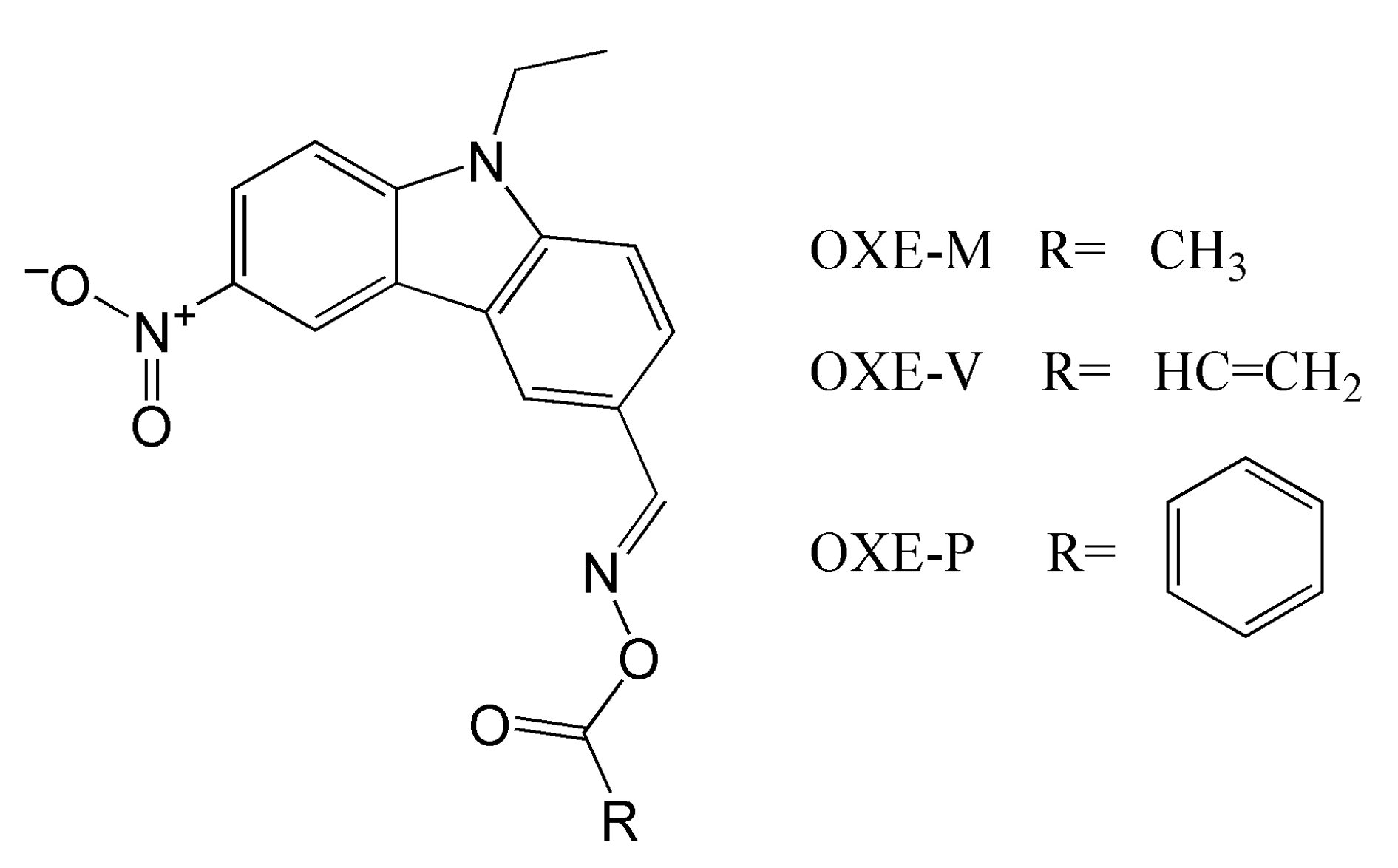

- Absence of decay of compounds and no decrease in absorbance intensity under the influence of light @405 nm for compounds: OXE-A0 and OXE-B0 (with -NOH group);

- generally, oxime esters undergo photolysis when exposed to light at a wavelength of 405 nm. Additionally, for OXE-B2 and OXE-B4, an increase in absorbance intensity was observed at a wavelength of 350 nm, which is explained by the formation of a new product.

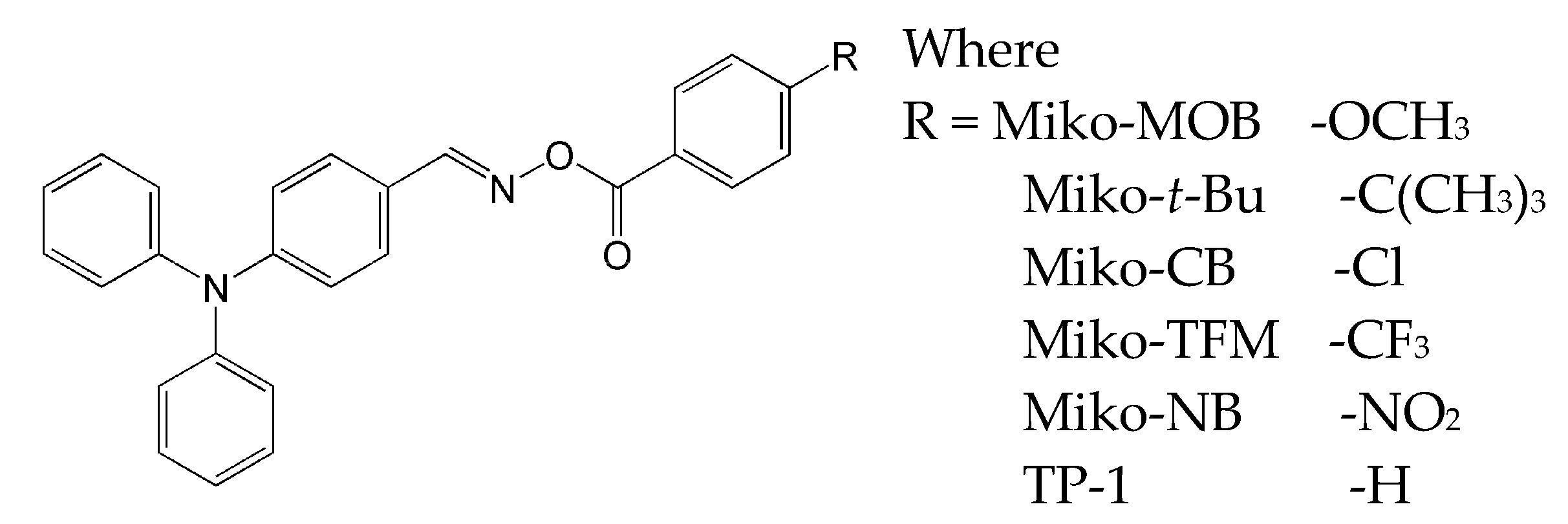

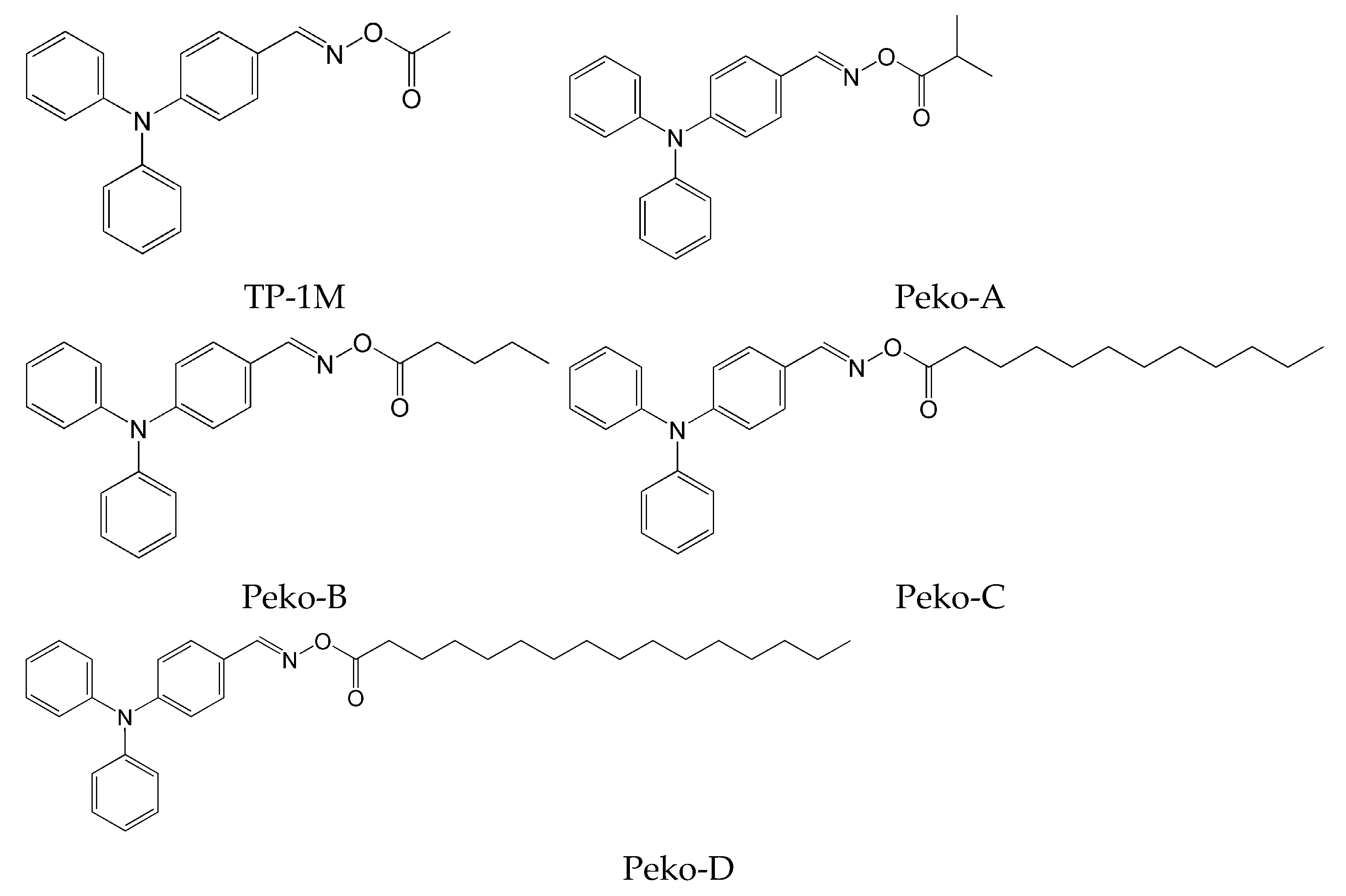

2.5. Triphenylamine-Based Oxime Esters

- ease of structural modification, it is also possible to easily adjust the absorption band to the entire visible range,

- ease of purification of triphenylamine derivatives,

- good solubility in most organic solvents,

- triphenylamine is readily available and cheap [72].

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, J.; Liu, X.; Xu, S.M.; Xu, M.; Wang, Y.; Lyu, Y.; Lyu, Y.; Li, A.Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. Sustainable oxime production via the electrosynthesis of hydroxylamine in a free state. Nat. Synth. 2025, 4, 1598–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, J.C. Functionalised oximes: Emergent precursors for carbon-, nitrogen-and oxygen-centred radicals. Molecules 2016, 21, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Song, J.; Shang, S.; Wang, D.; Li, J. Synthesis and antibacterial activity of oxime esters from dihydrocumic acid. BioResources 2012, 7, 4150–4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rykaczewski, K.A.; Wearing, E.R.; Blackmun, D.E.; Schindler, C.S. Reactivity of oximes for diverse methodologies and synthetic applications. Nat. Synth. 2022, 1, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Xu, R.; Gu, S.; Chen, K.; Li, J.; He, X.; Shang, S.; Song, Z.; Song, J. Discovery of natural rosin derivatives containing oxime ester moieties as potential antifungal agents to control tomato gray mould caused by Botrytis cinerea. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 5551–5560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Chen, W.T.; Min, L.J.; Han, L.; Sun, N.B.; Liu, X.H. Synthesis, Structure, and Antifungal Activities of 3-(Difluoromethyl)-Pyrazole-4-Carboxylic Oxime Ester Derivatives. Heteroat. Chem. 2022, 2022, 6078017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, P.; Ma, Z.; Xue, H.; Xie, K.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Xia, Q.; Zhang, M.; Gu, Y.C.; Zhang, W. Discovery of novel D/L-camphor derivatives containing oxime ester as fungicide candidates: Antifungal activity, structure-activity relationship and preliminary mechanistic study. Adv. Agrochem. 2025, 4, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Zhang, W.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Guo, Z.; Gao, Y.; Lei, P.; Liu, X. Synthesis and antifungal activity of coumarin oxime esters. Chin. J. Pestic. Sci. 2022, 24, 1189–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, S.; Ling, D.; Pang, C.; Jin, Z.; Lv, W.X.; Chi, Y.R. Design, Synthesis, and Herbicidal Evaluation of Novel Synthetic auxin herbicides containing 6-Indolylpyridine oxime ester/amine. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2025, 73, 4555–4562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groswald, A.M.; Gripshover, T.C.; Watson, W.H.; Wahlang, B.; Luo, J.; Jophlin, L.L.; Cave, M.C. Investigating the acute metabolic effects of the N-Methyl carbamate insecticide, methomyl, on mouse liver. Metabolites 2023, 13, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsushita, T.; Hirata, S.; Shirasaki, N.; Matsui, Y. Methomyl, a carbamate insecticide, forms oxygenated transformation products that inhibit acetylcholinesterase upon chlorination. Water Res. 2025, 285, 124068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Hou, J.; Li, M.; Liu, Z.; He, M.; Li, C.; Du, X.; Chen, L. Chronic Low-Dose Phoxim Exposure Impairs Silk Production in Bombyx mori L. (Lepidoptera: Bombycidae) by Disrupting Juvenile Hormone Signaling-Mediated Fibroin Synthesis. Toxics 2025, 13, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

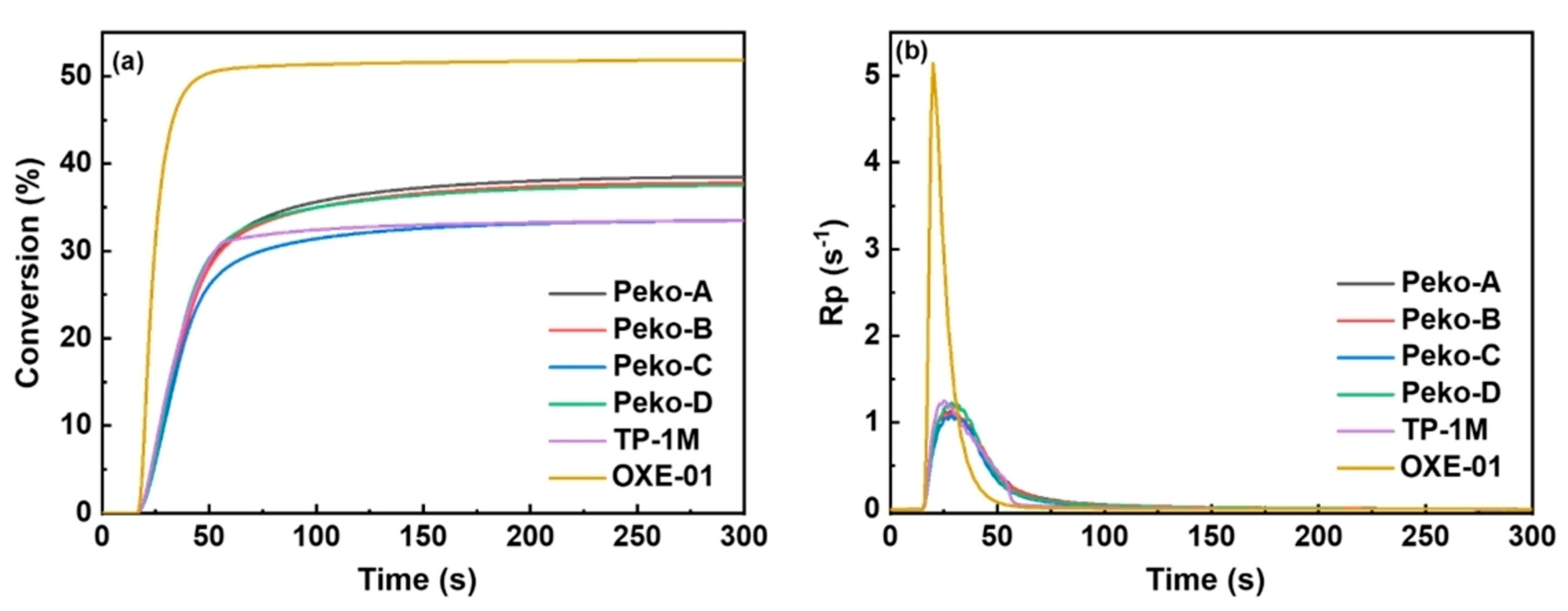

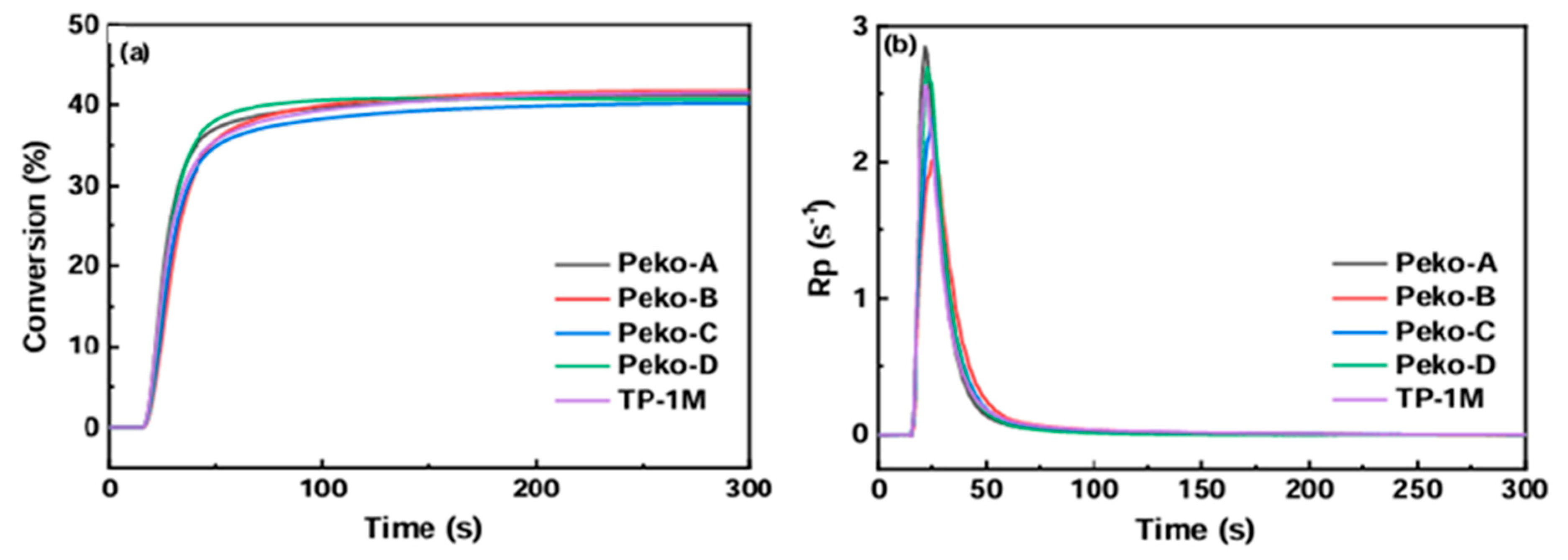

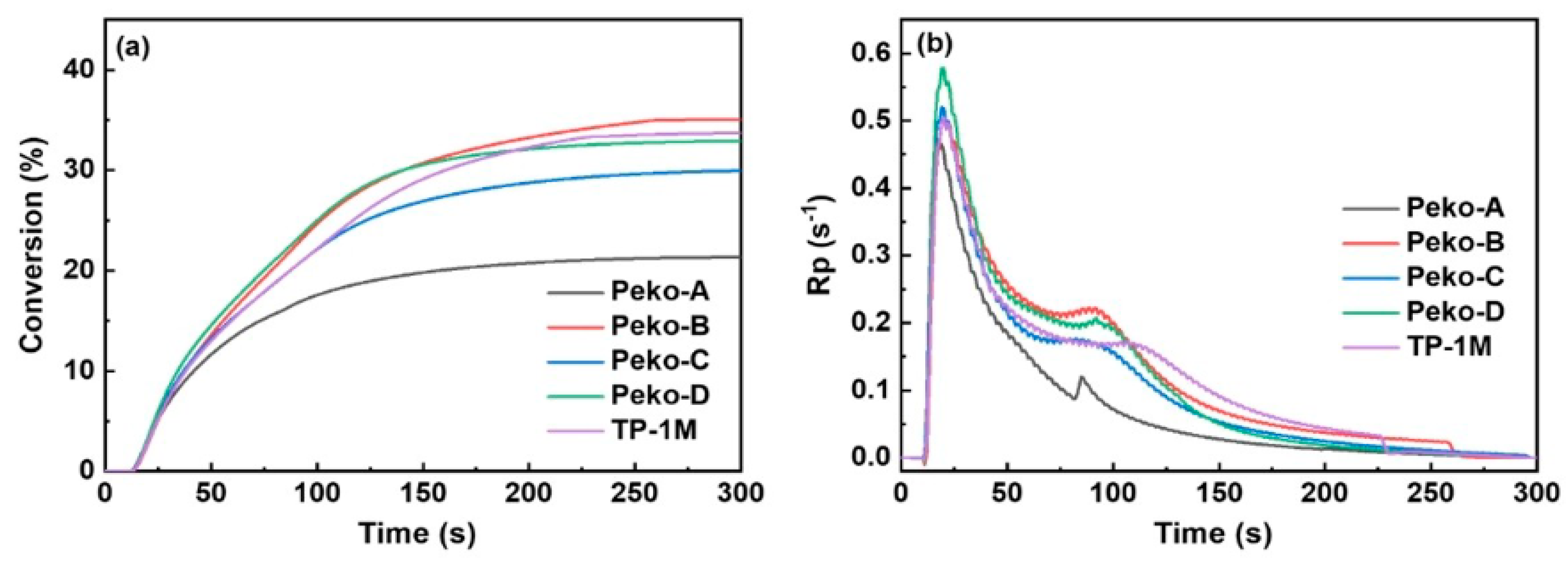

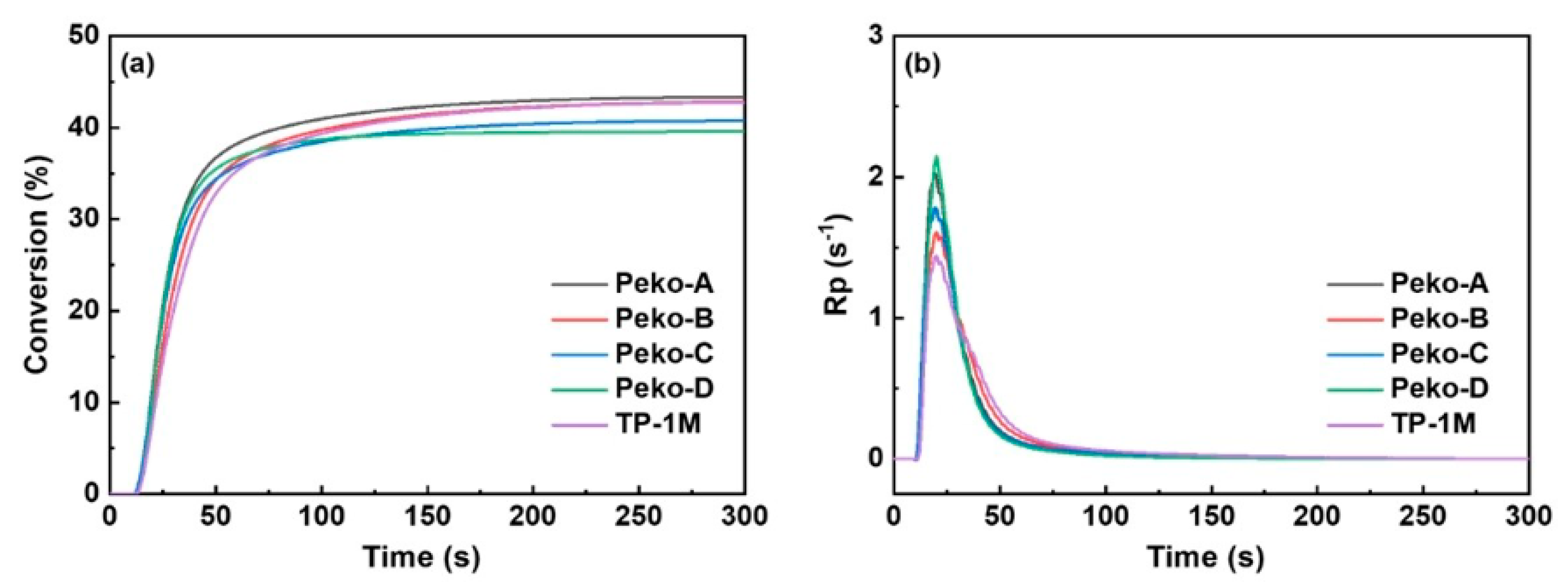

- Kuo, Y.C.; Hsieh, J.B.; Tu, W.H.; Dietlin, C.; Chang, T.W.; Lalevée, J.; Chen, Y.C. Linker unit modification of visible-light absorbing divergent triphenylamine-based oxime esters in free radical photopolymerization. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2025, 473, 116876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumur, F. Recent advances on carbazole-based oxime esters as photoinitiators of polymerization. Eur. Polym. J. 2022, 175, 111330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, J.B.; Chen, Y.C. The role of the Terminal Benzene Derivatives in Triphenylamine-Based Oxime Esters for Free Radical Photopolymerization. ChemPhotoChem 2024, 8, e202400082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammoud, F.; Giacoletto, N.; Noirbent, G.; Graff, B.; Hijazi, A.; Nechab, M.; Gigmed, D.; Dumur, F.; Lalevée, J. Substituent effects on the photoinitiation ability of coumarin-based oxime-ester photoinitiators for free radical photopolymerization. Mater. Chem. Front. 2021, 5, 8361–8370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammoud, F.; Giacoletto, N.; Nechab, M.; Graff, B.; Hijazi, A.; Dumur, F.; Lalevée, J. 5, 12-Dialkyl-5, 12-dihydroindolo [3, 2-a] carbazole-based oxime-esters for LED photoinitiating systems and application on 3D printing. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2022, 307, 2200082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammoud, F.; Lee, Z.H.; Graff, B.; Hijazi, A.; Lalevée, J.; Chen, Y.C. Novel phenylamine-based oxime ester photoinitiators for LED-induced free radical, cationic, and hybrid polymerization. J. Polym. Sci. 2021, 59, 1711–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozen, S.; Petrov, F.; Graff, B.; Roettger, M.; Morlet-Savary, F.; Schmitt, M.; Asmacher, A.; Lalevee, J. Oxime esters: Potential alternatives to phosphine oxides, for overcoming oxygen inhibition in material jetting applications. Eur. Polym. J. 2024, 220, 113459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Gao, T.; Zhang, Y.; Dietlin, C.; Morlet-Savary, F.; Schmitt, M.; Gigmes, D.; Dumur, F.; Lalevée, J. Carbazole-fused coumarin bis oxime esters (CCOBOEs) as efficient photoinitiators of polymerization for 3D printing with 405 nm LED. Eur. Polym. J. 2024, 215, 113186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elian, C.; Sanosa, N.; Bogliotti, N.; Herrero, C.; Sampedro, D.; Versace, D.L. An anthraquinone-based oxime ester as a visible-light photoinitiator for 3D photoprinting applications. Polym. Chem. 2023, 14, 3262–3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartomer Photoinitiators Product Catalog. Available online: https://coatingresins.arkema.com/files/live/sites/coatingresins_arkema/files/downloads/product-guides/uv-eb/sartomer-photoinitators-product-catalog-2022_en.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Karatsu, T.; Narusawa, M.; Yagai, S.; Kitamura, A.; Suzuki, H.; Okamura, H. Effect of alkyl group on the photocrosslinking of alkyl methacrylate based copolymers. J. Photopolym. Sci. Technol. 2013, 26, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Jin, M.; Pan, H.; Wan, D. Phenylthioether thiophene-based oxime esters as novel photoinitiators for free radical photopolymerization under LED irradiation wavelength exposure. Prog. Org. Coat. 2021, 151, 106019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, S.R.; An, J.; Choi, J.W.; Kim, S.; Park, J.; Park, C.B.; Lee, J.H. Moisture-resistant and highly adhesive acrylate-based sealing materials embedded with oxime-based photoinitiators for hermetic optical devices. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2021, 38, 2567–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zang, L.; Xin, Y.; Zou, Y. An overview of photopolymerization and its diverse applications. Appl. Res. 2023, 2, e202300030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, M.; Hirner, S.; Wiesbrock, F.; Fuchs, P. A review on modeling cure kinetics and mechanisms of photopolymerization. Polymers 2022, 14, 2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierau, L.; Elian, C.; Akimoto, J.; Ito, Y.; Caillol, S.; Versace, D.L. Bio-sourced monomers and cationic photopolymerization—The green combination towards eco-friendly and non-toxic materials. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2022, 127, 101517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumur, F. Recent advances on core-extended thioxanthones as efficient photoinitiators of polymerization. Eur. Polym. J. 2024, 206, 112794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y. Recent trends in advanced photoinitiators for vat photopolymerization 3D printing. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2022, 43, 2200202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noirbent, G.; Dumur, F. Photoinitiators of polymerization with reduced environmental impact: Nature as an unlimited and renewable source of dyes. Eur. Polym. J. 2021, 142, 110109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, D.; Peng, X.; Gigmes, D.; Schmitt, M.; Xiao, P.; Dumur, F.; Lalevée, J. Photoinitiating ability of pyrene–chalcone-based oxime esters with different substituents. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2023, 224, 2300293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauci, S.C.; Vranic, A.; Blasco, E.; Bräse, S.; Wegener, M.; Barner-Kowollik, C. Photochemically activated 3D printing inks: Current status, challenges, and opportunities. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2306468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geisler, E.; Lecompère, M.; Soppera, O. 3D printing of optical materials by processes based on photopolymerization: Materials, technologies, and recent advances. Photonics Res. 2022, 10, 1344–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, Y.; Wu, K.; Sun, G.; Liu, R.; Luo, J. One-pot efficient synthesis of amino-functionalized polyurethane capsules via photopolymerization for self-healing anticorrosion coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 2024, 189, 108348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuts, Y.; Bohley, M.; Krivitsky, A.; Bao, Y.; Luo, Z.; Leroux, J.C. Photopolymerization inks for 3D printing of elastic, strong, and biodegradable oral delivery devices. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2310111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, A.; Sokolowski, J.; Bociong, K. The photoinitiators used in resin based dental composite—A review and future perspectives. Polymers 2021, 13, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Gao, T.; Morlet-Savary, F.; Schmitt, M.; Dietlin, C.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, P.; Dumur, F.; Lalevée, J. Sunlight-driven photoinitiating systems for photopolymerization and application in direct laser writing. Polym. Chem. 2024, 15, 2899–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyszka, I.; Skowroński, Ł.; Jędrzejewska, B. Study on New Dental Materials Containing Quinoxaline-Based Photoinitiators in Terms of Exothermicity of the Photopolymerization Process. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzwonkowska-Zarzycka, M.; Sionkowska, A. Photoinitiators for medical applications—The latest advances. Molecules 2024, 29, 3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifkovits, J.L.; Burdick, J.A. Review: Photopolymerizable and degradable biomaterials for tissue engineering applications. Tissue Eng. 2007, 13, 2369–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, A.; He, X.; Ji, X.; Hu, D.; Pan, M.; Zhang, L.; Qian, Z. Current research progress of photopolymerized hydrogels in tissue engineering. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2021, 32, 2117–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Sun, X.; Chen, J.; Lei, Y. Natural or Natural-Synthetic Hybrid Polymer-Based Fluorescent Polymeric Materials for Bio-Imaging-Related Applications. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2017, 183, 461–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Q.; Dong, H.; Su, J.; Han, J.; Song, B.; Wei, Q.; Shi, Y. A Review of 3D Printing Technology for Medical Applications. Eng. 2018, 4, 729–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bella, F.; Ozzello, E.D.; Bianco, S.; Bongiovanni, R. Photo-polymerization of acrylic/methacrylic gel–polymer electrolyte membranes for dye-sensitized solar cells. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 225, 873–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickens, S.H.; Stansbury, J.W.; Choi, K.M.; Floyd, C.J.E. Photopolymerization Kinetics of Methacrylate Dental Resins. Macromolecules 2003, 36, 6043–6053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, D. Recent progress of the vat photopolymerization technique in tissue engineering: A brief review of mechanisms, methods, materials, and applications. Polymers 2023, 15, 3940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikova, T.; Maximov, J.; Todorov, V.; Georgiev, G.; Panov, V. Optimization of Photopolymerization Process of Dental Composites. Processes 2021, 9, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreu, A.; Su, P.C.; Kim, J.H.; Ng, C.S.; Kim, S.; Kim, I.; Lee, J.; Noh, J.; Subramanian, A.S.; Yoon, Y.-J. 4D Printing Materials for Vat Photopolymerization. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 44, 102024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabatc, J. The influence of a radical structure on the kinetics of photopolymerization. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2017, 55, 1575–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Allonas, X.; Ibrahim, A.; Liu, X. Progress in the Development of Polymeric and Multifunctional Photoinitiators. Progr. Polym. Sci. 2019, 99, 101165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, A.; Gallegos, I.T.; Felix, C.M. Photoinitiators in dentistry: A review. Prim. Dent. J. 2013, 2, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrzejewska, E. Photopolymerization kinetics of multifunctional monomers. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2001, 26, 605–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, N.S.; Marin, M.C.; Edge, M.; Davies, D.W.; Garrett, J.; Jones, F.; Navaratnam, S.; Parsons, B.J. Photochemistry and photoinduced chemical crosslinking activity of type I & II co-reactive photoinitiators in acrylated prepolymers. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 1999, 126, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meereis, C.T.; Leal, F.B.; Lima, G.S.; de Carvalho, R.V.; Piva, E.; Ogliari, F.A. BAPO as an alternative photoinitiator for the radical polymerization of dental resins. Dent. Mater. 2014, 30, 945–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomal, W.; Petko, F.; Galek, M.; Świeży, A.; Tyszka-Czochara, M.; Środa, P.; Mokrzyński, K.; Ortyl, J. Water-soluble type I radical photoinitiators dedicated to obtaining microfabricated hydrogels. Chem. Mater. 2024, 36, 6421–6439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

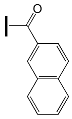

- Borjigin, T.; Feng, J.; Giacoletto, N.; Schmitt, M.; Morlet-Savary, F.; Graff, B.; Xiao, P.; Nechab, M.; Gigmes, D.; Dumur, F.; et al. Naphthoquinone-imidazolyl derivatives-based oxime esters as photoinitiators for blue LED-induced free radical photopolymerization. Eur. Polym. J. 2024, 206, 112801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Qiu, W.; Naumov, S.; Scherzer, T.; Hu, Z.; Chen, Q.; Knolle, W.; Li, Z. Conjugated bifunctional carbazole-based oxime esters: Efficient and versatile photoinitiators for 3D Printing under one-and two-photon excitation. ChemPhotoChem 2020, 4, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.; Li, M.; Yang, Y.; Li, Z.; Dietliker, K. Cleavable coumarin-based oxime esters with terminal heterocyclic moieties: Photobleachable initiators for deep photocuring under visible LED light irradiation. Polym. Chem. 2020, 11, 1356–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Li, Z. Synthesis and structure-activity relationship of N-substituted carbazole oxime ester photoinitiators. J. Photopolym. Sci. Technol. 2021, 34, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaca, N.; Balta, D.K.; Ocal, N.; Arsu, N. Mechanistic studies of thioxanthone–carbazole as a one-component type II photoinitiator. J. Lumin. 2014, 146, 424–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Ma, G.; Wang, K.; Gu, J.; Jiang, S.; Nie, J. Synthesis and photopolymerization kinetics of oxime ester photoinitiators. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2012, 123, 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, D.; Morlet-Savary, F.; Schmitt, M.; Graff, B.; Xiao, P.; Dumur, F.; Lalevée, J. Study on the photoinitiation mechanism of carbazole-based oxime esters (OXEs) as novel photoinitiators for free radical photopolymerization under near UV/visible-light irradiation exposure and the application of 3D printing. Eur. Polym. J. 2024, 202, 112662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Graff, B.; Xiao, P.; Dumur, F.; Lalevée, J. Nitro-carbazole based oxime esters as dual photo/thermal initiators for 3D printing and composite preparation. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2021, 42, 2100207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Giacoletto, N.; Schmitt, M.; Nechab, M.; Graff, B.; Morlet-Savary, F.; Xiao, P.; Dumur, F.; Lalevee, J. Effect of decarboxylation on the photoinitiation behavior of nitrocarbazole-based oxime esters. Macromolecules 2022, 55, 2475–2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahal, M.; Mokbel, H.; Graff, B.; Toufaily, J.; Hamieh, T.; Dumur, F.; Lalevée, J. Mono vs. difunctional coumarin as photoinitiators in photocomposite synthesis and 3D printing. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumur, F. Recent advances on coumarin-based photoinitiators of polymerization. Eur. Polym. J. 2022, 163, 110962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zou, X.; Zhu, G.; Liu, X.; Liu, R. Coumarin-based oxime esters: Photobleachable and versatile unimolecular initiators for acrylate and thiol-based click photopolymerization under visible light-emitting diode light irradiation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 16113–16123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Borjigin, T.; Graff, B.; Morlet-Savary, F.; Schmitt, M.; Gigmes, D.; Dumur, F.; Lalevée, J. Carbazole-fused coumarin based oxime esters (OXEs): Efficient photoinitiators for sunlight driven free radical photopolymerization. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 6881–6891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noon, A.; Hammoud, F.; Graff, B.; Hamieh, T.; Toufaily, J.; Morlet-Savary, F.; Schmitt, M.; Bui, T.T.; Rico, A.; Goubard, F.; et al. Photoinitiation Mechanisms of Novel Phenothiazine-Based Oxime and Oxime Esters Acting as Visible Light Sensitive Type I and Multicomponent Photoinitiators. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2023, 8, 2300205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Morlet-Savary, F.; Schmitt, M.; Graff, B.; Rico, A.; Ibrahim-Ouali, M.; Dumur, F.; Lalevée, J. Photoinitiation behavior of phenothiazines containing two oxime ester functionalities (OXEs) in free radical photopolymerization and 3D printing application. Dyes Pigm 2023, 215, 111202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumur, F. Recent advances on visible light Triphenylamine-based photoinitiators of polymerization. Eur. Polym. J. 2022, 166, 111036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, J.B.; Yen, S.C.; Hammoud, F.; Lalevée, J.; Chen, Y.C. Effect of terminal alkyl chains for free radical photopolymerization based on triphenylamine oxime ester visible-light absorbing type I photoinitiators. ChemistrySelect 2023, 8, e202301297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Z.H.; Huang, T.L.; Hammoud, F.; Chen, C.C.; Hijazi, A.; Graff, B.; Lalevee, J.; Chen, Y.C. Effect of the steric hindrance and branched substituents on visible phenylamine oxime ester photoinitiators: Photopolymerization kinetics investigation through photo-DSC experiments. Photochem. Photobiol. 2022, 98, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Chemical Structure | Abbreviation or Trade Name | Maximum Absorption, nm | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| OXE-1 Omnirad 1314 | 330 | UV-curable filter, resin formulation, electronics |

| OXE-2 Irgacure | 338 | pigments, LED curing, electronics |

| Speedcure PDO | 259 | electronics, adhe-sives, pigments |

| Speedcure 8001 | 240 and 331 | pigments, LED curing |

| Speedcure 8002 | 340 | pigments, LED curing, electronics |

| Compound | εmax (M−1 cm−1) | Ε405nm (M−1 cm−1) |

|---|---|---|

| OXE-P | 13,800 | 4100 |

| OXE-M | 13,000 | 4100 |

| OXE-V | 12,400 | 3900 |

| PI | Final Conversion (FC) (%) One-Component | Rp/[M]0 × 100 (s−1) One-Component | Final Conversion (FC) (%) Two-Component |

|---|---|---|---|

| OXE-A | 34 | 1.14 | 71 |

| OXE-B | 55 | 5.17 | 63 |

| OXE-C | 60 | 1.16 | 73 |

| OXE-D | 72 | 6.03 | 78 |

| OXE-E | 52 | 1.22 | 56 |

| OXE-F | 61 | 2.39 | 65 |

| OXE-G | 59 | 1.58 | 71 |

| OXE-H | 42 | 1.05 | 66 |

| OXE-I | 56 | 0.99 | 57 |

| OXE-J | 73 | 5.61 | 79 |

| OXE-K | 54 | 1.09 | 59 |

| PIs | FC in Laminate LED@405 nm |

|---|---|

| TPO | 83% |

| PTZ1 | 14% |

| PTZ2 | 71% |

| PTZ3 | 81% |

| PIs | Tonset [°C] | Tmax [°C] | Conversion [%] |

|---|---|---|---|

| PTZ1 | 206 | 241 | 37 |

| PTZ2 | 135 | 169 | 34 |

| PTZ3 | 125 | 171 | 36 |

| PI | Conversion of TA [%] | Conversion of Epoxy [%] |

|---|---|---|

| PTZ1/Iod | 68 | 81 |

| PTZ1/Iod | 82 | 83 |

| PTZ2/Iod | 83 | 69 |

| Iod | 23 | 38 |

| R | Series A | Series B |

|---|---|---|

|  | |

| OXE-A0 | OXE-B0 |

| OXE-A1 | OXE-B1 |

| OXE-A2 | OXE-B2 |

| OXE-A3 | OXE-B3 |

| - | OXE-B4 |

| - | OXE-B5 |

| - | OXE-B6 |

| - | OXE-B7 |

| - | OXE-B8 |

| - | OXE-B9 |

| Sample | λabs (ε × 104 M−1 cm−1) (nm) a | λPL (nm) a | Eox (V) b | Ered (V) c | Eg (eV) d | Td (°C) e | Tm (°C) f |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miko-TFM | 295 (2.23), 367 (5.25) | 485 | 0.82 | −1.36 | 3.07 | 165 | N.D. |

| Miko-CB | 295 (1.88), 364 (4.52) | 467 | 0.81 | −1.37 | 3.06 | 178 | N.D. |

| Miko-NB | 256 (2.73), 368 (3.06) | N.D. | 0.84 | −1.20 | 3.10 | 191 | N.D. |

| Miko-MOB | 263 (2.95), 361 (3.81) | 466 | 0.82 | −1.27 | 3.09 | 186 | N.D. |

| Miko-t-Bu | 296 (1.49), 361 (3.30) | 465 | 0.85 | −1.20 | 3.10 | 177 | 123 |

| TP-1 | 294 (0.91), 360 (2.23) | 467 | 0.90 | −1.34 | 3.05 | 174 | 129 |

| Sample | λabs [ε × 104 M−1 cm−1] [nm] a | λPL [nm] a | Eox [V] b | Ered [V] c | Eg [eV] d | ΔGET [kJ mol−1] e | Td [°C] f | Tm [°C] g | BDE N-O [kcal mol−1] h | ET [kcal mol−1] i |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peko-A | 294 (1.68), 354 (3.13) | 460 | 0.86 | −1.28 | 3.13 | −95.4 | 172 | N.D. | 48.21 | 53.87 |

| Peko-B | 294 (1.20), 356 (2.50) | 467 | 0.57 | −1.44 | 3.13 | −107.9 | 177 | 67 | 48.87 | 53.89 |

| Peko-C | 294 (1.65), 354 (3.02) | 460 | 0.73 | −1.41 | 3.13 | −95.4 | 183 | 64 | 48.83 | 53.89 |

| Peko-D | 294 (1.85), 354 (3.57) | 461 | 0.80 | −1.39 | 3.12 | −89.6 | 209 | 76 | 48.83 | 53.89 |

| TP-1M | 294 (1.08), 356 (2.25) | - | 0.57 | −1.18 | 3.15 | −134.8 | - | - | 48.75 | 53.89 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dzwonkowska-Zarzycka, M.; Balcerak-Woźniak, A.; Kabatc-Borcz, J. Oxime Esters as Efficient Initiators in Photopolymerization Processes. Molecules 2026, 31, 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010187

Dzwonkowska-Zarzycka M, Balcerak-Woźniak A, Kabatc-Borcz J. Oxime Esters as Efficient Initiators in Photopolymerization Processes. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):187. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010187

Chicago/Turabian StyleDzwonkowska-Zarzycka, Monika, Alicja Balcerak-Woźniak, and Janina Kabatc-Borcz. 2026. "Oxime Esters as Efficient Initiators in Photopolymerization Processes" Molecules 31, no. 1: 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010187

APA StyleDzwonkowska-Zarzycka, M., Balcerak-Woźniak, A., & Kabatc-Borcz, J. (2026). Oxime Esters as Efficient Initiators in Photopolymerization Processes. Molecules, 31(1), 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010187