Potential Nutraceutical Properties of Vicia faba L: LC-ESI-HR-MS/MS-Based Profiling of Ancient Faba Bean Varieties and Their Biological Activity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Phenolic Components and Antioxidant Activity

2.1.1. Total Polyphenols (TPC), Flavonoids (TFC) and Proanthocyanidins Content (PAs)

2.1.2. In Vitro Antioxidant Activity

2.1.3. Correlation Between Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity

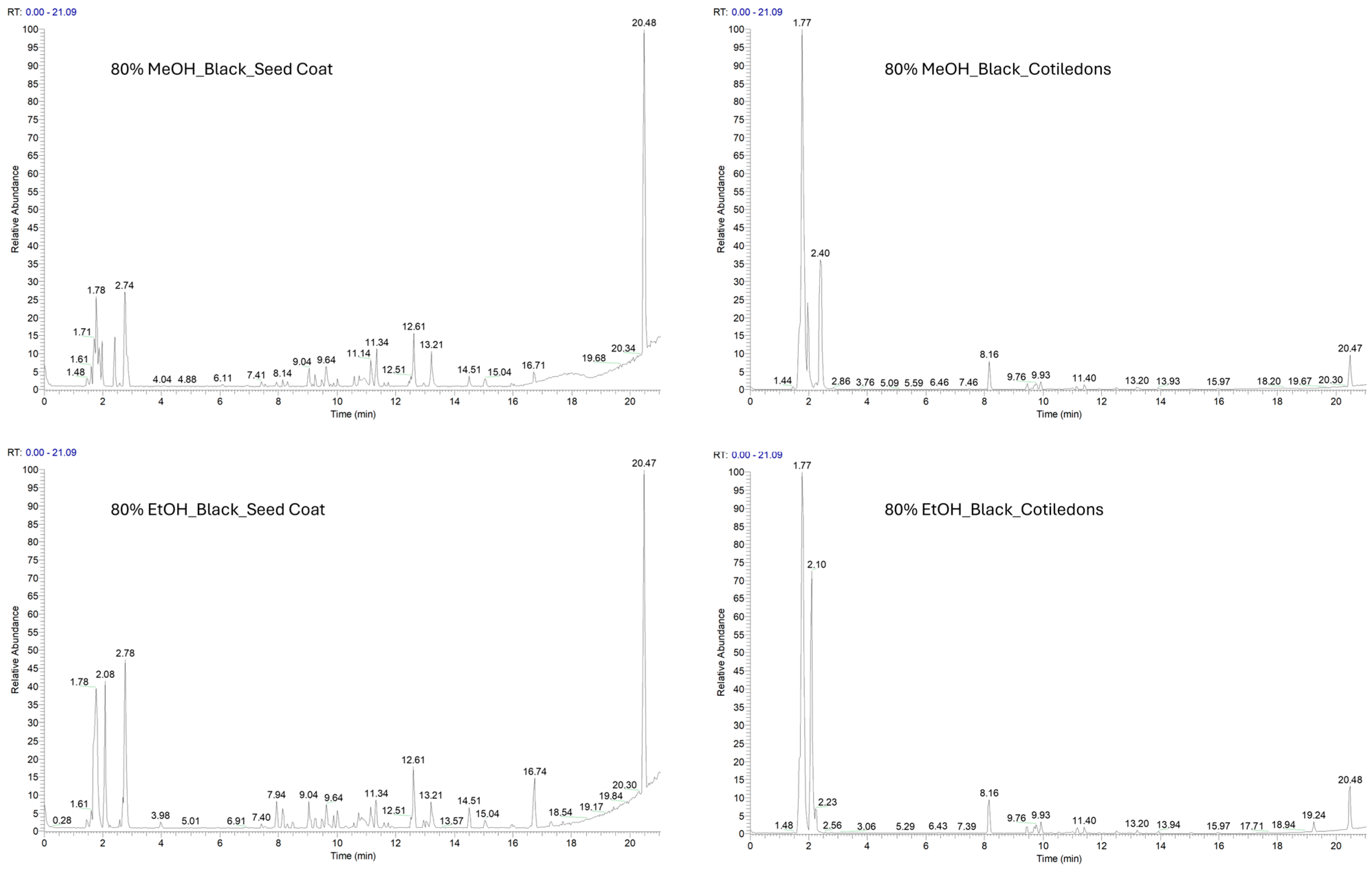

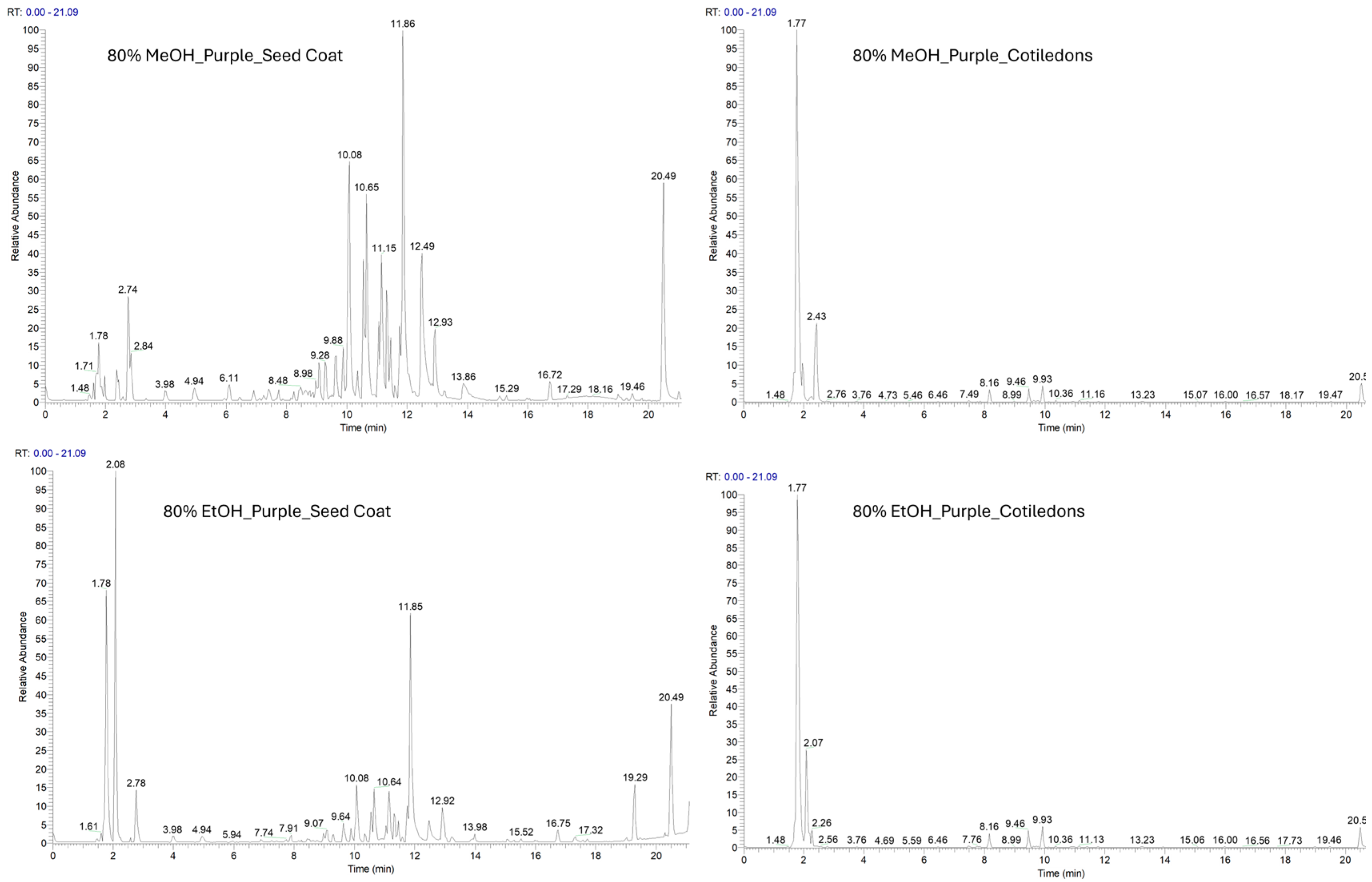

2.2. Phytochemical Investigation of Two Varieties of V. faba Beans by LC-ESI-HR-MS Analysis

2.3. Quantification of Proanthocyanidins by LC-ESI-MRM Analysis

2.4. Elemental Profiles

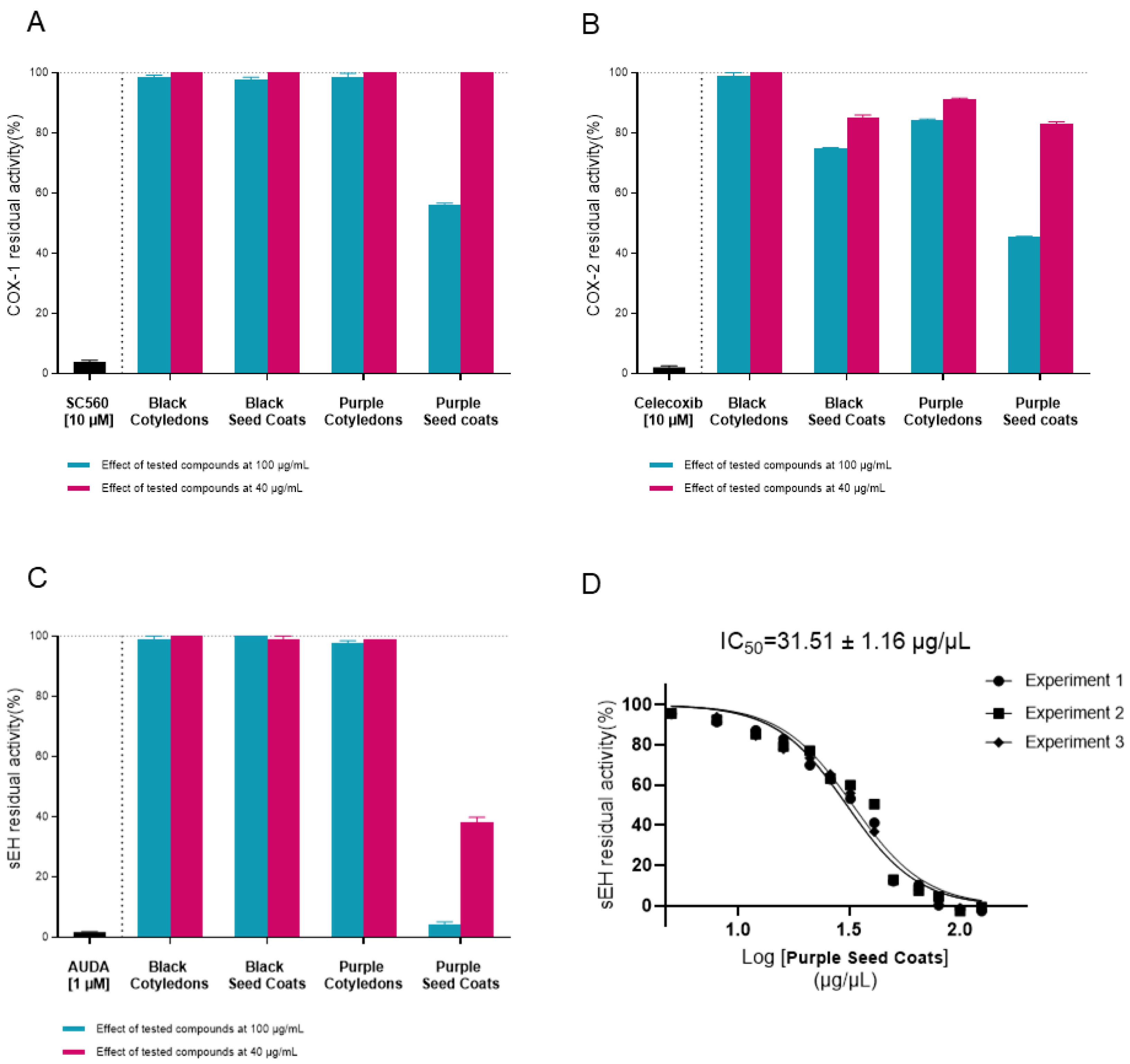

2.5. In Vitro Experimental Assay

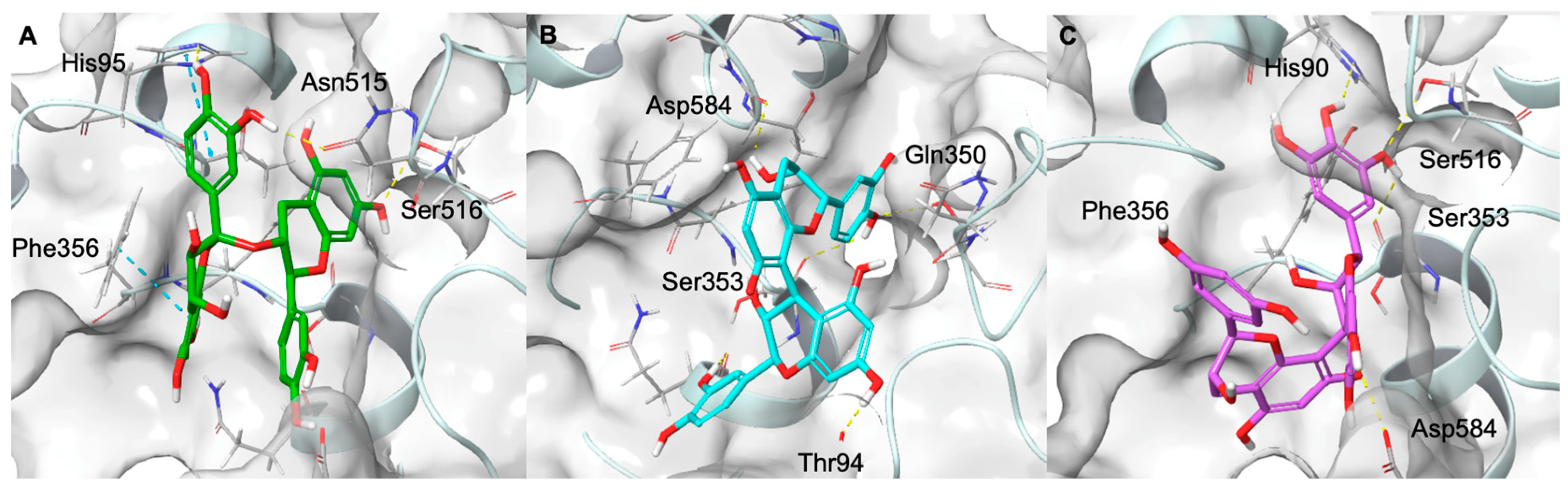

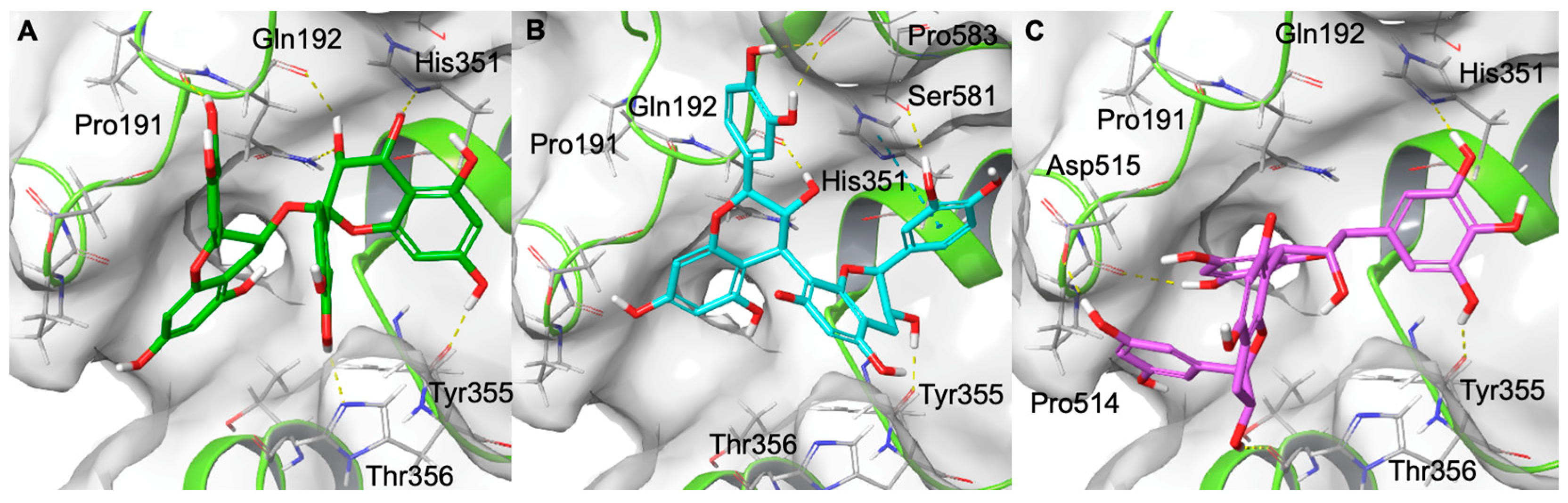

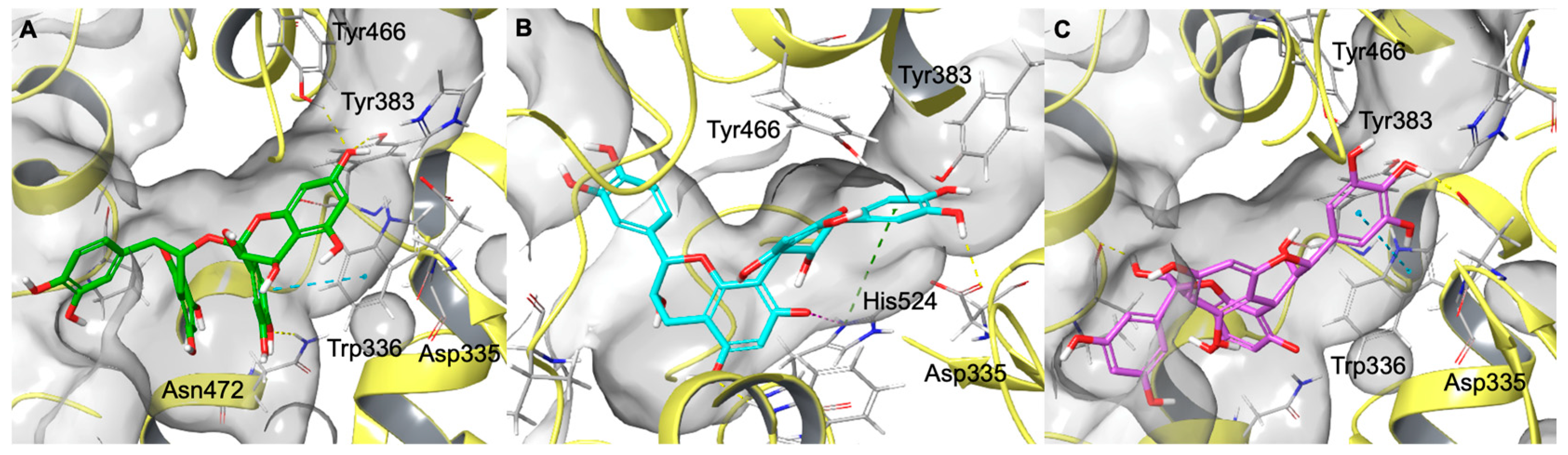

2.6. Computational Studies

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Standards and Reagents

3.2. Plant Material and Extraction Procedure

3.3. Analysis of Phenolic Compounds

3.3.1. Total Polyphenols Content (TPC)

3.3.2. Total Flavonoid Content (TFC)

3.3.3. Proanthocyanidins Content (PAs)

3.4. Antioxidant Capacity

3.4.1. DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

3.4.2. ABTS Radical Scavenging Activity

3.4.3. Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) Assay

3.5. Phytochemical Profiling of Ancient V. faba by LC-ESI-HR-MS/MS Analysis

3.6. Method for Quantification of Proanthocyanidins by LC-ESI-MRM Analysis

3.7. Elemental Composition Analysis

3.8. In Vitro Biochemical Assays

3.8.1. COXs Cell-Free Assay

3.8.2. sEH Cell-Free Assay

3.9. Molecular Docking Experiments

3.10. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abu-Reidah, I.M.; Contreras, M.D.; Arráez-Román, D.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A.; Segura-Carretero, A. UHPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS-based metabolic profiling of Vicia faba L. (Fabaceae) seeds as a key strategy for characterization in foodomics. Electrophoresis 2014, 35, 1571–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senbayram, M.; Wenthe, C.; Lingner, A.; Isselstein, J.; Steinmann, H.; Kaya, C.; Köbke, S. Legume-based mixed intercropping systems may lower agricultural born NO emissions. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2016, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labba, I.C.M.; Frokiær, H.; Sandberg, A.S. Nutritional and antinutritional composition of fava bean (Vicia faba L., var. minor) cultivars. Food Res. Int. 2021, 140, 110038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhull, S.B.; Kidwai, M.K.; Noor, R.; Chawla, P.; Rose, P.K. A review of nutritional profile and processing of faba bean (L.). Legume Sci. 2022, 4, e129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaei, S.P.; Ghorbani, M.; Tagliazucchi, D.; Martini, S.; Gotti, R.; Themelis, T.; Tesini, F.; Gianotti, A.; Toschi, T.G.; Babini, E. Functional, nutritional, antioxidant, sensory properties and comparative peptidomic profile of faba bean (Vicia faba L.) seed protein hydrolysates and fortified apple juice. Food Chem. 2020, 330, 127120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, M.; Sorensen, J.C.; Petersen, I.L.; Duque-Estrada, P.; Cappello, C.; Tlais, A.Z.A.; Di Cagno, R.; Ispiryan, L.; Sahin, A.W.; Arendt, E.K.; et al. Associating Compositional, Nutritional and Techno-Functional Characteristics of Faba Bean (Vicia faba L.) Protein Isolates and Their Production Side-Streams with Potential Food Applications. Foods 2023, 12, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.W.; Ou, X.; Wang, J.Y.; Wang, Z.L.; Du, W.T.; Zhao, J.J.; Han, Y.Z. Antifungal Peptide P852 Controls Fusarium Wilt in Faba Bean (Vicia faba L.) by Promoting Antioxidant Defense and Isoquinoline Alkaloid, Betaine, and Arginine Biosyntheses. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.M.; Yoon, H.; Shin, M.J.; Lee, S.; Yi, J.; Jeon, Y.A.; Wang, X.; Desta, K.T. Nutrient Levels, Bioactive Metabolite Contents, and Antioxidant Capacities of Faba Beans as Affected by Dehulling. Foods 2023, 12, 4063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, J.B.; Skylas, D.J.; Mani, J.S.; Xiang, J.; Walsh, K.B.; Naiker, M. Phenolic Profiles of Ten Australian Faba Bean Varieties. Molecules 2021, 26, 4642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Becerra, L.; Morimoto, S.; Arrellano-Ordoñez, E.; Morales-Miranda, A.; Guevara-Gonzalez, R.G.; Feregrino-Pérez, A.A.; Lomas-Soria, C. Polyphenolic Compounds in Fabaceous Plants with Antidiabetic Potential. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo-Silva, C.A.; Elso-Freudenberg, M.; Aranda-Bustos, M. L-DOPA Trends in Different Tissues at Early Stages of Growth: Effect of Tyrosine Treatment. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, E.F.; Hassanien, A.A.; Wong, J.H.; Bah, C.S.F.; Soliman, S.S.; Ng, T.B. Isolation of a New Trypsin Inhibitor from the Faba Bean (Vicia faba cv.) with Potential Medicinal Applications. Protein Pept. Lett. 2011, 18, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehi, B.; Abu-Reidah, I.M.; Sharopov, F.; Karazhan, N.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Akram, M.; Daniyal, M.; Khan, F.S.; Abbaass, W.; Zainab, R.; et al. ts-A comprehensive review on chemical composition and phytopharmacology. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 790–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, H.S.; Andersen, J.H. The estimation of vicine and convicine in fababeans (Vicia faba L.) and isolated fababean proteins. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1978, 29, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beretta, A.; Manuelli, M.; Cena, H. Favism: Clinical Features at Different Ages. Nutrients 2023, 15, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharan, S.; Zanghelini, G.; Zotzel, J.; Bonerz, D.; Aschoff, J.; Saint-Eve, A.; Maillard, M.N. Fava bean (Vicia faba L.) for food applications: From seed to ingredient processing and its effect on functional properties, antinutritional factors, flavor, and color. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Saf. 2021, 20, 401–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman Ali, E.A.A.M.; Awadelkareem, A.M.; Gasim, S.; Yousif, N.E.A. Nutritional composition and anti nutrients of two faba bean (Vicia faba L.) lines. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2014, 2, 538–544. [Google Scholar]

- Khamassi, K.; Ben Jeddi, F.; Hobbs, D.; Irigoyen, J.; Stoddard, F.; O’Sullivan, D.M.; Jones, H. A baseline study of vicine-convicine levels in faba bean (Vicia faba L.) germplasm. Plant Genet. Resour.-C 2013, 11, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berni, R.; Cantini, C.; Romi, M.; Hausman, J.F.; Guerriero, G.; Cai, G. Agrobiotechnology Goes Wild: Ancient Local Varieties as Sources of Bioactives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.J.; Chang, S.K.C. A comparative study on phenolic profiles and antioxidant activities of legumes as affected by extraction solvents. J. Food Sci. 2007, 72, S159–S166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaieb, N.; González, J.L.; López-Mesas, M.; Bouslama, M.; Valiente, M. Polyphenols content and antioxidant capacity of thirteen faba bean (Vicia faba L.) genotypes cultivated in Tunisia. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 970–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.H.; Tian, C.R.; Gao, C.Y.; Wang, B.N.; Yang, W.Y.; Kong, X.; Chai, L.Q.; Chen, G.C.; Yin, X.F.; He, Y.H. Phenolic composition, antioxidant capacity and inhibitory effects on -glucosidase and lipase of immature faba bean seeds. Int. J. Food Prop. 2018, 21, 2366–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baginsky, C.; Peña-Neira, A.; Cáceres, A.; Hernández, T.; Estrella, I.; Morales, H.; Pertuzé, R. Phenolic compound composition in immature seeds of fava bean (Vicia faba L.) varieties cultivated in Chile. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2013, 31, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Morton, J.D.; Maes, E.; Kumar, L.; Serventi, L. Exploring faba beans (Vicia faba L.): Bioactive compounds, cardiovascular health, and processing insights. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 4354–4367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rybiński, W.; Karamać, M.; Sulewska, K.; Amarowicz, R. Antioxidant activity of faba bean extracts. In Plant Extracts; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cosme, F.; Aires, A.; Pinto, T.; Oliveira, I.; Vilela, A.; Goncalves, B. A Comprehensive Review of Bioactive Tannins in Foods and Beverages: Functional Properties, Health Benefits, and Sensory Qualities. Molecules 2025, 30, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojo, M.A. Tannins in Foods: Nutritional Implications and Processing Effects of Hydrothermal Techniques on Underutilized Hard-to-Cook Legume Seeds—A Review. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2022, 27, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Yang, X.; Gao, X.; Yang, H.; Ma, S.; Huang, S.; Zhu, J.; Zhou, H.; Li, X.; Gu, X.; et al. Multiomics Analyses Reveal the Dual Role of Flavonoids in Pigmentation and Abiotic Stress Tolerance of Soybean Seeds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 3231–3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desta, K.T.; Hur, O.S.; Lee, S.; Yoon, H.; Shin, M.J.; Yi, J.; Lee, Y.; Ro, N.Y.; Wang, X.; Choi, Y.M. Origin and seed coat color differently affect the concentrations of metabolites and antioxidant activities in soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merrill) seeds. Food Chem. 2022, 381, 132249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matias, A.; Nunes, S.L.; Poejo, J.; Mecha, E.; Serra, A.T.; Madeira, P.J.; Bronze, M.R.; Duarte, C.M. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity of a flavonoid-rich concentrate recovered from Opuntia ficus-indica juice. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 3269–3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ressaissi, A.; Attia, N.; Fale, P.L.; Pacheco, R.; Victor, B.L.; Machuqueiro, M.; Serralheiro, M.L.M. Isorhamnetin derivatives and piscidic acid for hypercholesterolemia: Cholesterol permeability, HMG-CoA reductase inhibition, and docking studies. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2017, 40, 1278–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabakam, G.T.; Njoya, E.M.; Chukwuma, C.I.; Mashele, S.S.; Nguekeu, Y.M.M.; Tene, M.; Awouafack, M.D.; Makhafola, T.J. The Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of the Methanolic Extract, Fractions, and Isolated Compounds from Eriosema montanum Baker f. (Fabaceae). Molecules 2024, 29, 5885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartel, I.; Mandryk, I.; Horbanczuk, J.O.; Wierzbicka, A.; Koszarska, M. Nutraceutical Properties of Syringic Acid in Civilization Diseases-Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, S.C.; Lee, B.S.; Yi, S.A.; Yu, J.S.; Lee, J.; Ko, Y.J.; Pang, C.; Kim, K.H. Discovery of Dihydrophaseic Acid Glucosides from the Florets of Carthamus tinctorius. Plants 2020, 9, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Kim, M.C.; Choi, C.W.; Kim, J.; Jin, H.S.; Lee, R.; Lee, J.W.; Park, J.H.; Huh, D.; Jeong, S.Y. Effects of Dihydrophaseic Acid 3’-O-beta-d-Glucopyranoside Isolated from Lycii radicis Cortex on Osteoblast Differentiation. Molecules 2016, 21, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karolkowski, A.; Meudec, E.; Bruguiere, A.; Mitaine-Offer, A.C.; Bouzidi, E.; Levavasseur, L.; Sommerer, N.; Briand, L.; Salles, C. Faba Bean (Vicia faba L. minor) Bitterness: An Untargeted Metabolomic Approach to Highlight the Impact of the Non-Volatile Fraction. Metabolites 2023, 13, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samukha, V.; Fantasma, F.; D’Urso, G.; Colarusso, E.; Schettino, A.; Marigliano, N.; Chini, M.G.; Saviano, G.; De Felice, V.; Lauro, G.; et al. Chemical Profiling of Polar Lipids and the Polyphenolic Fraction of Commercial Italian Phaseolus Seeds by UHPLC-HRMS and Biological Evaluation. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crescenzi, M.A.; D’Urso, G.; Piacente, S.; Montoro, P. UPLC-ESI-QTRAP-MS/MS Analysis to Quantify Bioactive Compounds in Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare Mill.) Waste with Potential Anti-Inflammatory Activity. Metabolites 2022, 12, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Urso, G.; Maldini, M.; Pintore, G.; d’Aquino, L.; Montoro, P.; Pizza, C. Characterisation of fruit from Italy following a metabolomics approach through integrated mass spectrometry techniques. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 74, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, K.; Nastic, N.; Ilic, M.; Skendi, A.; Stefanou, S.; Acanski, M.; Rocha, J.M.; Papageorgiou, M. A screening study of elemental composition in legume Fabaceae sp.) cultivar from Serbia: Nutrient accumulation and risk assessment. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 130, 6127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, M.; Platel, K. Impact of soaking, germination, fermentation, and thermal processing on the bioaccessibility of trace minerals from food grains. J. Food Process Pres. 2020, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, I.J.S.; da Silva, M.M.; da Silva, R.; De Franca, E.J.; da Silva, M.J.; Kato, M.T. Microwave-assisted digestion for multi-elemental determination in beans, basil, and mint by ICP OES and flame photometry: An eco-friendly alternative. Food Chem. 2025, 481, 143970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Panel on Micronutrients. Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, V.K., Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Copper, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and Zinc; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222316/ (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Ribeiro, D.; Freitas, M.; Tome, S.M.; Silva, A.M.; Laufer, S.; Lima, J.L.; Fernandes, E. Flavonoids inhibit COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes and cytokine/chemokine production in human whole blood. Inflammation 2015, 38, 858–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Jin, C.H. Inhibitory Activity of Flavonoids, Chrysoeriol and Luteolin-7-O-Glucopyranoside, on Soluble Epoxide Hydrolase from Capsicum chinense. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, W.H.; Zhu, Q.M.; Huo, X.K.; Sun, C.P.; Ma, X.C.; Xiao, H.T. Total flavonoids of Inula japonica alleviated the inflammatory response and oxidative stress in LPS-induced acute lung injury via inhibiting the sEH activity: Insights from lipid metabolomics. Phytomedicine 2022, 107, 154380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, D.X.; Luo, D.; Tanigawa, S.; Hashimoto, F.; Uto, T.; Masuzaki, S.; Fujii, M.; Sakata, Y. Prodelphinidin B-4 3’-O-gallate, a tea polyphenol, is involved in the inhibition of COX-2 and iNOS via the downregulation of TAK1-NF-kappaB pathway. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2007, 74, 742–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, D.X.; Masuzaki, S.; Hashimoto, F.; Uto, T.; Tanigawa, S.; Fujii, M.; Sakata, Y. Green tea proanthocyanidins inhibit cyclooxygenase-2 expression in LPS-activated mouse macrophages: Molecular mechanisms and structure-activity relationship. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2007, 460, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringbom, T.; Huss, U.; Stenholm, A.; Flock, S.; Skattebol, L.; Perera, P.; Bohlin, L. Cox-2 inhibitory effects of naturally occurring and modified fatty acids. J. Nat. Prod. 2001, 64, 745–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blobaum, A.L.; Marnett, L.J. Structural and functional basis of cyclooxygenase inhibition. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 1425–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouzer, C.A.; Marnett, L.J. Structural and Chemical Biology of the Interaction of Cyclooxygenase with Substrates and Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 7592–7641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amano, Y.; Yamaguchi, T.; Tanabe, E. Structural insights into binding of inhibitors to soluble epoxide hydrolase gained by fragment screening and X-ray crystallography. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2014, 22, 2427–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farag, M.A.; Sharaf El-Din, M.G.; Selim, M.A.; Owis, A.I.; Abouzid, S.F.; Porzel, A.; Wessjohann, L.A.; Otify, A. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Metabolomics Approach for the Analysis of Major Legume Sprouts Coupled to Chemometrics. Molecules 2021, 26, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L. Colorimetry of Total Phenolics with Phosphomolybdic-Phosphotungstic Acid Reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimler, D.; Vignolini, P.; Dini, M.G.; Romani, A. Rapid tests to assess the antioxidant activity of Vicia faba L. dry beans. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 3053–3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, L.J.; Hrstich, L.N.; Chan, B.G. The Conversion of Procyanidins and Prodelphinidins to Cyanidin and Delphinidin. Phytochemistry 1985, 25, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabber, J.H.; Zeller, W.E. Direct versus Sequential Analysis of Procyanidin-and Prodelphinidin-Based Condensed Tannins by the HCl-Butanol-Acetone-Iron Assay. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 2906–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shay, P.E.; Trofymow, J.A.; Constabel, C.P. An improved butanol-HCl assay for quantification of water-soluble, acetone: Methanol-soluble, and insoluble proanthocyanidins (condensed tannins). Plant Methods 2017, 13, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benzie, I.F.; Strain, J.J. Ferric reducing/antioxidant power assay: Direct measure of total antioxidant activity of biological fluids and modified version for simultaneous measurement of total antioxidant power and ascorbic acid concentration. Methods Enzymol. 1999, 299, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fantasma, F.; Samukha, V.; Aliberti, M.; Colarusso, E.; Chini, M.G.; Saviano, G.; De Felice, V.; Lauro, G.; Casapullo, A.; Bifulco, G.; et al. Essential Oils of Laurus nobilis L.: From Chemical Analysis to In Silico Investigation of Anti-Inflammatory Activity by Soluble Epoxide Hydrolase (sEH) Inhibition. Foods 2024, 13, 2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colarusso, E.; Lauro, G.; Potenza, M.; Galatello, P.; Garigliota, M.L.D.; Ferraro, M.G.; Piccolo, M.; Chini, M.G.; Irace, C.; Campiglia, P.; et al. 5-methyl-2-carboxamidepyrrole-based novel dual mPGES-1/sEH inhibitors as promising anticancer candidates. Arch. Der Pharm. 2025, 358, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimon, G.; Sidhu, R.S.; Lauver, D.A.; Lee, J.Y.; Sharma, N.P.; Yuan, C.; Frieler, R.A.; Trievel, R.C.; Lucchesi, B.R.; Smith, W.L. Coxibs interfere with the action of aspirin by binding tightly to one monomer of cyclooxygenase-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlando, B.J.; Malkowski, M.G. Substrate-selective Inhibition of Cyclooxygeanse-2 by Fenamic Acid Derivatives Is Dependent on Peroxide Tone. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 15069–15081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrödinger, Release 2025-2; Protein Preparation Workflow; Epik, S., LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2024; Impact, Schrödinger, LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2024; Prime, Schrödinger, LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.schrodinger.com/citations/ (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Sastry, G.M.; Adzhigirey, M.; Day, T.; Annabhimoju, R.; Sherman, W. Protein and ligand preparation: Parameters, protocols, and influence on virtual screening enrichments. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2013, 27, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrödinger, Release 2025-2; LigPrep, S., LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2025.

- Yang, Y.; Yao, K.; Repasky, M.P.; Leswing, K.; Abel, R.; Shoichet, B.K.; Jerome, S.V. Efficient Exploration of Chemical Space with Docking and Deep Learning. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2021, 17, 7106–7119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesner, R.A.; Murphy, R.B.; Repasky, M.P.; Frye, L.L.; Greenwood, J.R.; Halgren, T.A.; Sanschagrin, P.C.; Mainz, D.T. Extra precision glide: Docking and scoring incorporating a model of hydrophobic enclosure for protein-ligand complexes. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 6177–6196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halgren, T.A.; Murphy, R.B.; Friesner, R.A.; Beard, H.S.; Frye, L.L.; Pollard, W.T.; Banks, J.L. Glide: A new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 2. Enrichment factors in database screening. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 1750–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friesner, R.A.; Banks, J.L.; Murphy, R.B.; Halgren, T.A.; Klicic, J.J.; Mainz, D.T.; Repasky, M.P.; Knoll, E.H.; Shelley, M.; Perry, J.K.; et al. Glide: A new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 1. Method and assessment of docking accuracy. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 1739–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrödinger, Release 2025-2; Glide, Schrödinger, LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2025.

| VFB Extract | VFP Extract | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seed Coats | Cotyledons | Seed Coats | Cotyledons | |||||

| Ext_MeOH | Ext_EtOH | Ext_MeOH | Ext_EtOH | Ext_MeOH | Ext_EtOH | Ext_MeOH | Ext_EtOH | |

| TPC (mg GAE g−1 DW) | 0.88 ± 0.1 b | 1.07 ± 0.3 b | 0.80 ± 0.2 b | 0.62 ± 0.1 b | 1.96 ± 0.1 a | 1.82 ± 0.4 a | 0.72 ± 0.1 b | 0.93 ± 0.1 b |

| TFC (mg CE g−1 DW) | 0.94 ± 0.1 b | 1.00 ± 0.04 b | 0.54 ± 0.1 c | 0.43 ± 0.1 c | 1.75 ± 0.3 a | 1.18 ± 0.1 b | 0.80 ± 0.2 c | 0.58 ± 0.2 c |

| PAs (AU g−1 DW) | 0.0478 bc | 0.0321 bc | 0.0024 c | 0.0008 c | 1.1531 a | 0.1322 b | 0.0982 bc | 0.0012 c |

| VFB | VFP | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seed Coats | Cotyledons | Seed Coats | Cotyledons | |||||

| Ext_MeOH | Ext_EtOH | Ext_MeOH | Ext_EtOH | Ext_MeOH | Ext_EtOH | Ext_MeOH | Ext_EtOH | |

| DPPH (mg TE g−1) | 3.13 ± 0.1 c | 2.78 ± 0.1 c | 1.58 ± 0.1 a | 1.67 ± 0.1 b | 14.84 ± 1.0 d | 10.16 ± 0.6 d | 0.96 ± 0.1 d | 0.99 ± 0.1 d |

| ABTS (mg TE g−1) | 6.30 ± 0.2 c | 5.82 ± 0.2 cd | 4.26 ± 0.3 f | 3.81 ± 0.2 f | 16.88 ± 0.3 a | 9.50 ± 0.1 b | 5.59 ± 0.1 d | 4.93 ± 0.1 e |

| FRAP (mg TE g−1) | 90.36 ± 2.9 c | 85.20 ± 0.8 c | 62.06 ± 2.1 d | 56.21 ± 0.6 d | 388.79 ± 20.4 a | 226.22 ± 17.7 b | 39.10 ± 2.1 d | 37.74 ± 1.3 d |

| Correlation Coefficient (R) | Total Phenolic | Flavonoids | Proanthocyanidins | DPPH | ABTS | FRAP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPC | 1 | |||||

| TFC | 0.889 ** | 1 | ||||

| PAs | 0.740 * | 0.854 ** | 1 | |||

| DPPH | 0.958 ** | 0.911 ** | 0.856 ** | 1 | ||

| ABTS | 0.899 ** | 0.952 ** | 0.951 ** | 0.959 ** | 1 | |

| FRAP | 0.932 ** | 0.920 ** | 0.906 ** | 0.993 ** | 0.977 ** | 1 |

| Name | Formula | Δppm | m/z | RT [min] | M/MS | VFBC | VFBS | VFPC | VFPS | Ion Mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FLAVONOIDS | ||||||||||

| Myricetin hexose dehoxyhexose | C27H30O17 | 0.39 | 625.1413 | 10.89 | 315.01/479.08/151.00 | nd | x | nd | x | neg |

| Quercetin 3,7-dirhamnoside | C27H30O15 | 0.09 | 593.1513 | 11.48 | 277.22/315.05/241.01/153 | x | x | x | x | neg |

| Di-C-glucopyranosylphloretin | C27H34O15 | 2.6 | 597.1832 | 11.61 | 307.0984/387.1087/417.1195 | nd | x | nd | x | neg |

| Quercetin 3-robinobioside | C27H30O16 | 0.42 | 609.1464 | 11.64 | 301.0355 | x | x | x | x | neg |

| Kaempferol-rutinoside | C27H30O15 | 0.91 | 593.1517 | 12.53 | 285.0406/430.0907/447.0927 | x | x | x | x | neg |

| 6-Hydroxyluteolin 3′-methyl ether 7-sophoroside | C28H32O17 | 0.55 | 639.1570 | 11.77 | 331.05/316.02 | x | x | x | x | neg |

| myricetin arabinoside | C20H18O12 | 0.79 | 449.0729 | 11.8 | 317.0286 | nd | x | x | x | neg |

| Myricetin-robinobioside | C27H30O17 | 0.41 | 625.1413 | 11.81 | 317.03/463.09/179.00 | x | x | x | x | neg |

| Myricitrin | C21H20O12 | 0.15 | 463.0882 | 11.9 | 317.0293 | x | x | x | x | neg |

| Hyperin | C21H20O12 | −0.66 | 463.0879 | 12.6 | 301.04 | x | x | x | x | neg |

| Rhamnetin-galactoside | C22H22O12 | 0.13 | 477.1039 | 12.95 | 315.0496/331.0461 | nd | nd | x | x | neg |

| myricetin | C15H10O8 | 0.23 | 317.0304 | 13.9 | 178.9979/151.0028/137.0234 | nd | x | nd | x | neg/pos |

| Astragalin | C21H20O11 | 0.34 | 447.0934 | 14.40 | 301.0355/151.0028 | nd | nd | x | x | neg |

| Kaempferol rutinoside | C39H50O24 | 1.86 | 901.2625 | 8.81 | 739.21/285.04/447.09 | x | x | nd | nd | neg |

| Quercetin 3-galactosyl-galactoside | C27H30O17 | 0.34 | 625.1412 | 9.16 | 463.09/301.04 | x | nd | x | nd | neg |

| Kaempferol 3-sophorotrioside | C33H40O21 | 2.26 | 771.1999 | 9.24 | 462.0809/315.0148 | x | x | x | x | neg |

| Quercetin 3,4′-diglucoside | C27H30O17 | 1.22 | 625.1407 | 10.11 | 301.0358/463.0901 | nd | x | nd | x | neg |

| Robinin | C33H40O19 | 2.9 | 739.2100 | 10.26 | 593.15/431.10/285.04 | x | nd | x | nd | neg |

| rutin | C27H30O16 | 1.41 | 609.1459 | 10.7 | 463.0857/301.0343 | x | x | x | x | neg |

| myricetin-galactopyranoside | C21H20O13 | 1.6 | 479.0832 | 11.21 | 317.0292 | nd | x | x | x | neg |

| vicenin 2 | C27H30O15 | 0.57 | 593.1515 | 11.33 | 353.06/383.07/473.1093 | x | x | x | x | neg |

| Isoschaftoside | C26H28O14 | 0.92 | 565.1557 | 11.39 | 379.0813/391.0812/409.0923 | nd | x | x | x | neg |

| PROANTHOCYANIDINS | ||||||||||

| Catechin * | C15H14O6 | 5.2 | 289.0722 | 9.07 | 109.03/245.08 | x | x | x | x | neg |

| Epicatechin * | C15H14O6 | 5.1 | 289.0721 | 10.01 | 109.03/245.08 | x | x | x | x | neg |

| (Epi)gallocatechin-(epi)gallocatechin I | C30H26O14 | 2 | 609.1256 | 7.83 | 305.0674/423.0724/177.084/125.0234 | nd | x | nd | x | neg |

| (Epi)gallocatechin-(epi)catechin I | C30H26O13 | 2.7 | 593.1306 | 8.73 | 305.0673/177.0187/407.0772 | nd | x | nd | x | neg |

| 2 × [(Epi)gallocatechin]-(epi)catechin I | C45H38O20 | 3.11 | 897.1896 | 8.67 | 125.0231/177.0183/ | nd | x | nd | x | neg |

| procyanidin B * | C30H25O12 | 1.4 | 577.1354 | 8.84 | 289.0723/407.0758/125.0233 | x | x | x | x | neg |

| epigallocatechin | C15H14O7 | 4.1 | 305.1242 | 8.5 | 125.0234/167.0342/219.0660 | nd | x | nd | x | neg |

| procyanidin A * | C30H24O12 | 2.98 | 575.1201 | 5.84 | nd | x | nd | x | neg | |

| LIPIDS and Derivatives | ||||||||||

| 9,12,13-Trihydroxy-15-octadecenoic acid | C18H34O5 | 0.97 | 329.2337 | 17.74 | 171.1018/211.1334/229.1442 | x | x | x | x | neg |

| 12(13)-DiHOME | C18H34O4 | 1.04 | 313.2388 | 22.50 | 129.0910/183.1384/295.2277 | x | x | x | x | neg |

| 9,10-dihydroxy-octadecenoic acid | C18H34O4 | 0.65 | 313.2386 | 22.74 | 157.086 | x | x | x | x | neg |

| Lyso PE(18:2/0:0) | C23H44NO7P | −0.25 | 476.2781 | 23.91 | 279.2331/196.0367 | x | x | x | nd | neg/pos |

| 13-HOTrE | C18H30O3 | 0.63 | 293.2124 | 24.31 | 96.9589/179.0734 | nd | x | nd | x | neg |

| 12-Oxo phytodienoic acid | C18H28O3 | 1.5 | 275.2011 | 17.17 | 174.1169/133.1013 | nd | x | nd | x | pos |

| Sphingosine | C18H37NO2 | 0.81 | 300.2900 | 22.15 | 62.0607 | x | x | x | x | pos |

| Lyso PI(18:2/0:0) | C27H49O12P | 0.86 | 597.3040 | 22.15 | 337.2734 | x | x | x | nd | pos |

| 9,12,13-Trihydroxyoctadeca-10,15-dienoic acid | C18H32O5 | −1.36 | 327.2176 | 16.81 | 211.13/183.14 | nd | x | nd | x | neg |

| AMINOACIDS and PEPTIDES | ||||||||||

| Alanyl-valyl-prolyl-tyrosyl-proline | C27H39N5O7 | −0.26 | 544.2764 | 13.31 | 502.27/484.26/296.22/130.09 | x | x | x | x | neg |

| Tyrosine methyl ester | C10H13NO3 | −3.45 | 194.0816 | 22.93 | 149.06 | x | x | x | x | neg |

| N6,N6,N6-Trimethyl-lysine | C9H20N2O2 | −0.38 | 189.1597 | 1.69 | 143.0855 | x | x | x | nd | pos |

| Arginine | C6H14N4O2 | −1.08 | 175.1187 | 1.72 | 116.0707/70.0656 | x | x | x | x | pos |

| Glutathione (reduced) | C10H17N3O6S | 0.64 | 308.0913 | 2.20 | nd | nd | x | x | pos | |

| Tyrosine | C9H11NO3 | 2.15 | 182.0816 | 2.49 | x | x | x | x | pos | |

| N6-Acetyl-lysine | C8H16N2O3 | 1.45 | 189.1236 | 2.50 | nd | nd | x | x | pos | |

| L-DOPA | C9H11NO4 | 1.45 | 198.0764 | 2.66 | 192.0705/139.0390 | x | x | x | x | pos |

| N-Acetyl-tyrosine | C11H13NO4 | 1.07 | 224.0920 | 2.70 | 178.0861 | x | x | x | x | pos |

| Leucylproline | C11H20N2O3 | 1.74 | 229.1551 | 2.76 | 109.0651 | x | x | x | x | pos |

| Phenylalanine | C9H11NO2 | 2.14 | 166.0866 | 5.88 | 120.0808 | x | x | x | x | pos |

| PHENOLIC ACIDS | ||||||||||

| Gallic acid | C7H6O5 | 1.48 | 169.0135 | 4.11 | 125.0233 | nd | x | nd | x | neg |

| Protocatechuic acid hexoside | C13H16O9 | 0.64 | 315.0724 | 7.30 | 169.0134/151.0027 | nd | nd | nd | x | neg |

| Diphenol glucuronide | C12H14O8 | 0.61 | 285.0618 | 7.47 | 195.07/209.05/223.06/72.99 | x | x | x | x | neg |

| Methyl gallate | C8H8O5 | −4.25 | 183.0291 | 8.06 | 139.04/97.03 | x | x | nd | nd | neg |

| 3′-O-methyl(3′,4′-dihydroxybenzyl tartaricacid) (3′-O-methylfukiic acid) | C13H10N4O4 | −3.52 | 285.0619 | 8.39 | 195.0656/209.0452 | nd | nd | x | x | neg |

| Derric acid | C12H14O7 | 3.9 | 269.0667 | 9.73 | 209.05/179.05/137.06 | x | x | x | x | neg |

| 8-O-Glucopyranosyloxy-2,7-dimethyl-2,4-decadiene-1,10-dioic acid | C18H28O10 | 2.6 | 403.1609 | 11.40 | 223.10/179.11/119.03 | x | x | x | x | neg |

| Piscidic acid | C11H12O7 | −0.05 | 255.0510 | 7.86 | 165.05/179.03/193.05/72.99 | x | x | x | x | neg |

| Eucomic acid | C11H12O6 | −1.08 | 239.0559 | 9.08 | 195.10/141.05/59.01 | x | x | x | x | neg |

| Syringic acid | C9H10O5 | 1.16 | 181.0498 | 13.26 | nd | x | x | nd | pos | |

| ACIDS and derivatives | ||||||||||

| Galactonic acid | C6H12O7 | −4.26 | 195.0502 | 1.74 | 129.02/75.01/135.04/179.03 | x | x | x | x | neg |

| 3-Carboxy-4-methyl-5-propyl-2-furanpropionic acid | C12H16O5 | −1.28 | 239.0922 | 10.87 | 195.10/141.05/59.01 | nd | x | nd | x | neg |

| Gallicynoic acid F | C18H32O6 | 0.28 | 343.2127 | 13.16 | 229.14/209.12/171.10135.08 | nd | x | nd | x | neg |

| Azelaic acid | C9H16O4 | −3.32 | 187.0970 | 13.89 | 125.0965/99.9480 | nd | nd | x | x | neg |

| 3-Hydroxymethylglutaric acid | C6H10O5 | 1.35 | 163.0603 | 2.45 | 105.0337 | x | x | x | x | pos |

| Argininosuccinic acid | C10H18N4O6 | 0.01 | 291.1299 | 2.61 | x | x | x | x | pos | |

| ALKALOIDS | ||||||||||

| Vicine | C10H16N4O7 | −0.48 | 303.0945 | 1.89 | 141.0408 | x | x | x | x | neg |

| Convicine | C10H15N3O8 | −0.84 | 304.0784 | 2.50 | 174.96/158.98/79.96 | x | x | x | x | neg |

| CARBOHYDRATES | ||||||||||

| Trehalose | C12H22O11 | −0.42 | 341.1086 | 1.89 | 89.0232 | x | x | x | x | neg |

| Glucose butyrate | C10H18O8 | 0.17 | 265.0929 | 2.82 | 89.02/85.03/119.03/ | x | x | x | x | neg |

| Maltotriose | C18H32O16 | −1.29 | 543.1317 | 1.87 | 381.0794/212.8517 | x | x | x | x | pos |

| Lactose | C12H22O11 | −1.46 | 381.0788 | 1.89 | 109.1014/337.0875 | x | x | x | x | pos |

| SAPONIN | ||||||||||

| Soyasaponin I | C48H78O18 | −0.26 | 941.5112 | 19.26 | 615.39457.37/205.07 | x | x | x | x | neg |

| TERPENOIDS | ||||||||||

| Dihydrophaseic acid glucopyranoside (DPA3G) | C21H32O10 | 2.6 | 443.1925 | 8.26 | 101.02 | x | x | x | x | neg |

| Metabolite | VFBS-M | VFBS-E | VFBC-M | VFBC-E | VFPS-M | VFPS-E | VFPC-M | VFPC-E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catechin * | 195.6 ± 2.09 | 260.5 ± 4.8 | 136.6 ± 0.63 | 134.1 ± 0.85 | 322.9 ± 67.2 | 393.2 ± 0.1 | 134.7 ± 0.89 | 136.9 ± 0.63 |

| Epicatechin * | 187.2 ± 2.7 | 253.1 ± 2.1 | 128.7 ± 0.27 | 126.4 ± 0.10 | 238.7 ± 31.5 | 292.6 ± 16.7 | 126.0 ± 0.1 | 127.2 ± 0.4 |

| epigallocatechin | 152.1 ± 2.7 | 169.0 ± 1.04 | nd | nd | 148.5 ± 10.3 | 150.8 ± 1.04 | nd | nd |

| epigallocatechin catechin I | 70.3 ± 1.3 | 64.7 ± 1.3 | nd | nd | 130.4 ± 22.7 | 108.8 ± 5.5 | nd | nd |

| (Epi)gallocatechin-(epi)gallocatechin I | 515.8 ± 0.01 | 355.6 ± 36.7 | nd | nd | 475.8 ± 50.0 | 371.6 ± 83.2 | nd | nd |

| 2 × [(Epi)gallocatechin]-(epi)catechin I | 35.5 ± 0.01 | 35.5 ± 0.09 | nd | nd | 36.7 ± 0.4 | 35.6 ± 0.1 | nd | nd |

| procyanidin A * | 39.7 ± 0.13 | 47.9 ± 1.3 | nd | nd | 41.4 ± 1.6 | 51.1 ± 1.6 | nd | nd |

| procyanidin B * | 175.3 ± 12.2 | 98.2 ± 27.9 | 36.0 ± 0.35 | 35.2 ± 0.02 | 260.3 ± 23.8 | 240.8 ± 34.4 | 36.8 ± 0.36 | 36.1 ± 0.76 |

| Total proanthocyanidin | 1371.5 | 1284.5 | 301.3 | 295.7 | 1654.7 | 1644.5 | 297.5 | 300.2 |

| VFB | VFP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elements | Seed Coats | Cotyledons | Seed Coats | Cotyledons |

| Cu (λ 327.395 nm) | 4.80 ± 0.07 | 16.55 ± 0.40 | 1.12 ± 0.02 | 14.55 ± 0.04 |

| Fe (λ 259.940 nm) | 4.89 ± 0.09 | 65.09 ± 1.58 | 25.36 ± 0.65 | 44.21 ± 1.05 |

| K (λ 766.491 nm) | 7675.95 ± 2.30 | 12,615.34 ± 5.88 | 6242.13 ± 2.28 | 13,548.84 ± 4.65 |

| B (λ 249.772 nm) | 19.61 ± 0.11 | 6.11 ± 0.02 | 20.16 ± 0.23 | 8.99 ± 0.06 |

| Mg (λ 280.270 nm) | 2539.25 ± 1.04 | 953.41 ± 1.87 | 1977.69 ± 1.03 | 927.30 ± 1.52 |

| Mn (λ 257.610 nm) | 39.96 ± 0.22 | 16.35 ± 0.11 | 7.46 ± 0.03 | 13.00 ± 0.02 |

| Ni (λ 216.555 nm) | 0.65 ± 0.02 | 2.00 ± 0.06 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 2.74 ± 0.03 |

| Zn (λ 206.200 nm) | 88.04 ± 0.94 | 85.15 ± 1.32 | 23.08 ± 0.11 | 47.50 ± 0.09 |

| P (λ 213.618 nm) | 387.35 ± 1.02 | 5080.98 ± 1.16 | 366.55 ± 0.09 | 6159.66 ± 1.64 |

| S (λ 181.972 nm) | 329.35 ± 4.18 | 1934.99 ± 1.61 | 297.27 ± 2.23 | 1721.12 ± 1.45 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fantasma, F.; D’Urso, G.; Capuano, A.; Colarusso, E.; Aliberti, M.; Grassi, F.; Brunese, M.C.; Saviano, G.; De Felice, V.; Lauro, G.; et al. Potential Nutraceutical Properties of Vicia faba L: LC-ESI-HR-MS/MS-Based Profiling of Ancient Faba Bean Varieties and Their Biological Activity. Molecules 2026, 31, 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010184

Fantasma F, D’Urso G, Capuano A, Colarusso E, Aliberti M, Grassi F, Brunese MC, Saviano G, De Felice V, Lauro G, et al. Potential Nutraceutical Properties of Vicia faba L: LC-ESI-HR-MS/MS-Based Profiling of Ancient Faba Bean Varieties and Their Biological Activity. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):184. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010184

Chicago/Turabian StyleFantasma, Francesca, Gilda D’Urso, Alessandra Capuano, Ester Colarusso, Michela Aliberti, Francesca Grassi, Maria Chiara Brunese, Gabriella Saviano, Vincenzo De Felice, Gianluigi Lauro, and et al. 2026. "Potential Nutraceutical Properties of Vicia faba L: LC-ESI-HR-MS/MS-Based Profiling of Ancient Faba Bean Varieties and Their Biological Activity" Molecules 31, no. 1: 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010184

APA StyleFantasma, F., D’Urso, G., Capuano, A., Colarusso, E., Aliberti, M., Grassi, F., Brunese, M. C., Saviano, G., De Felice, V., Lauro, G., Reginelli, A., Chini, M. G., Casapullo, A., Bifulco, G., & Iorizzi, M. (2026). Potential Nutraceutical Properties of Vicia faba L: LC-ESI-HR-MS/MS-Based Profiling of Ancient Faba Bean Varieties and Their Biological Activity. Molecules, 31(1), 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010184