Unexpected Orange Photoluminescence from Tetrahedral Manganese(II) Halide Complexes with Bidentate Phosphanimines

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

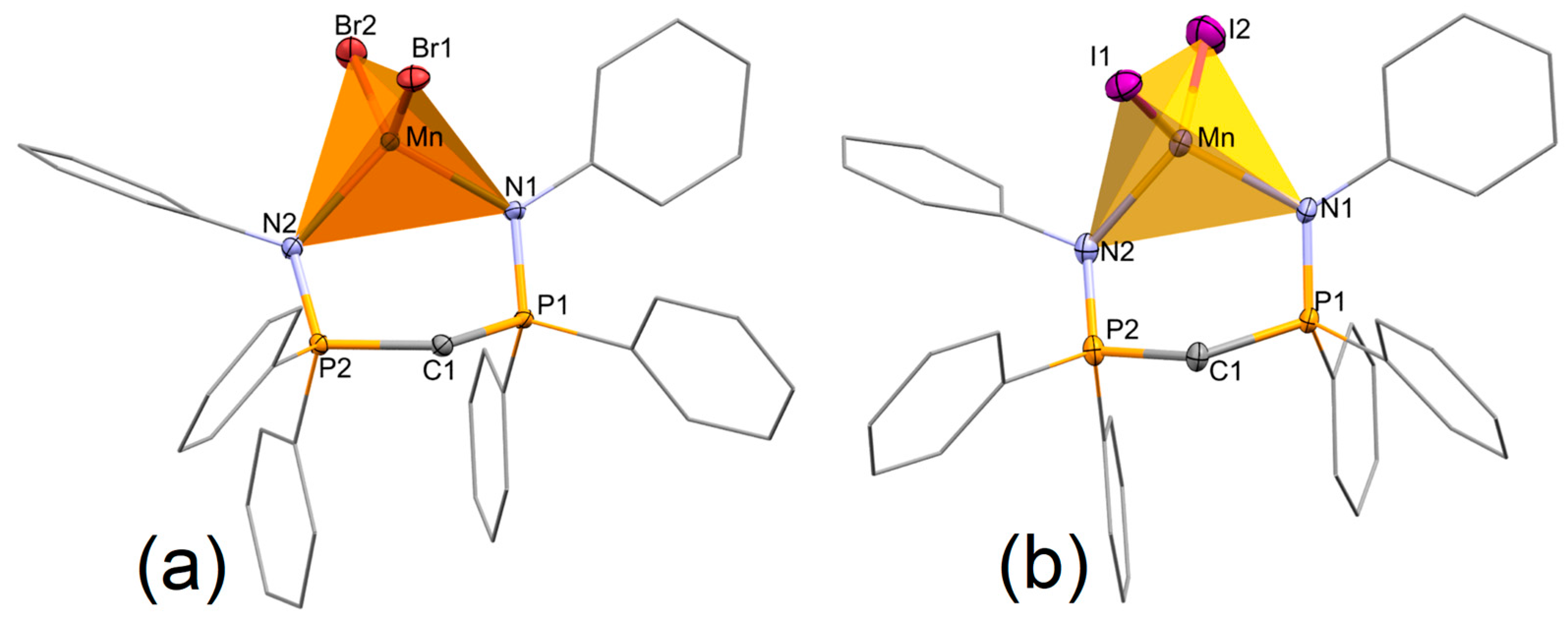

2.1. Synthesis, Characterization, and Single-Crystal X-Ray Diffraction of the Complexes

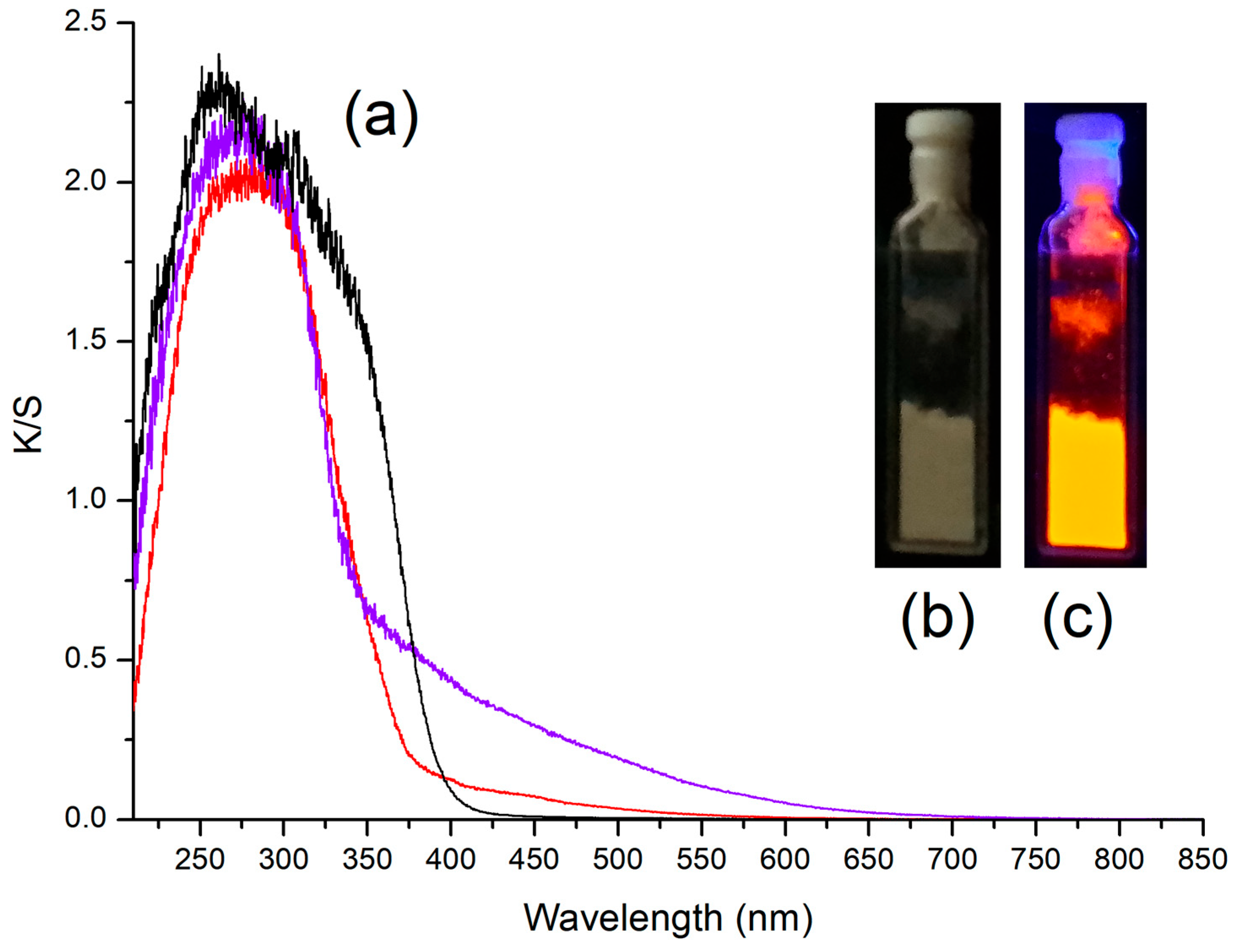

2.2. Photoluminescence of the Complexes

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Materials and Methods

3.2. Characterizations

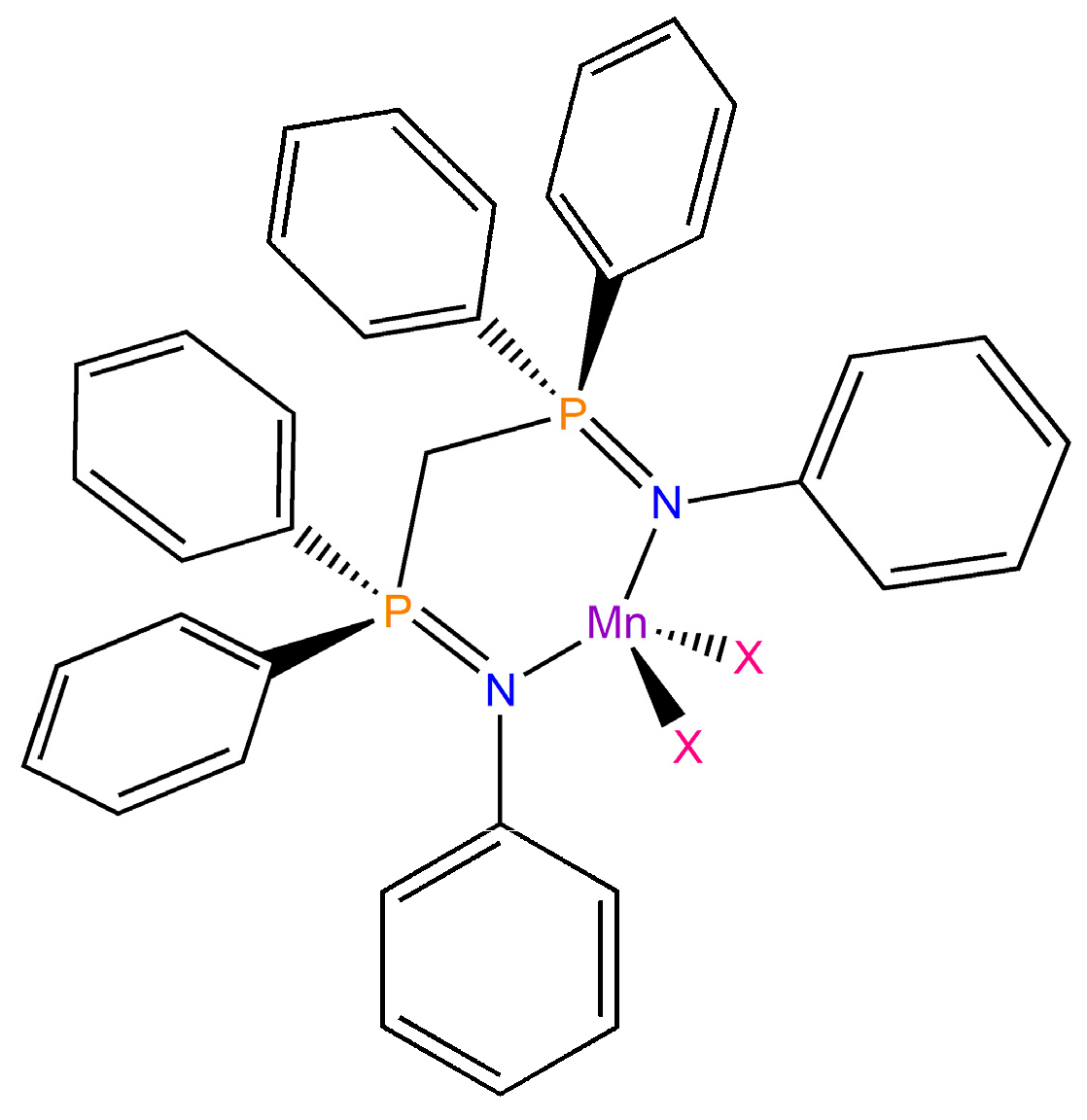

3.3. Synthesis of [MnX2{(PhN=PPh2)CH2}] (X = Br, I)

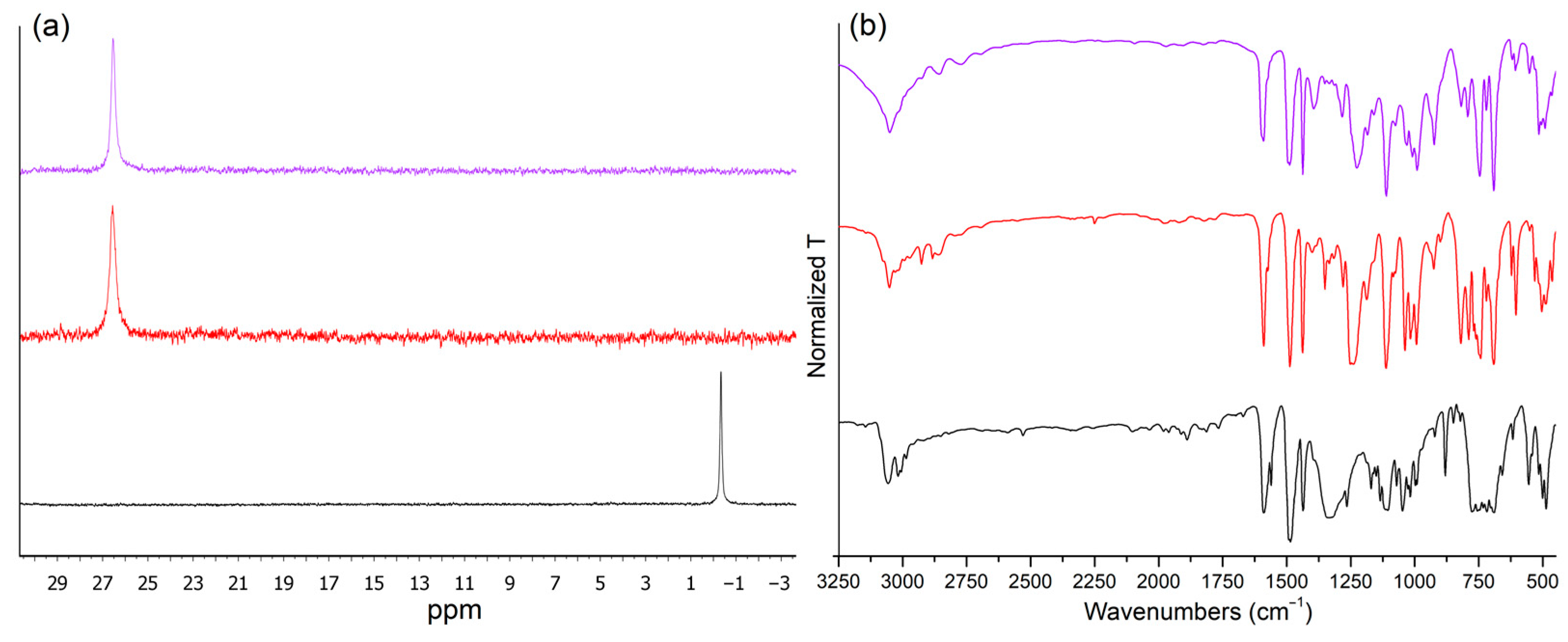

- Characterization of [MnBr2{(PhN=PPh2)CH2}]. Anal. calcd. for C37H32Br2MnN2P2 (781.36 g mol−1, %): C, 56.87; H, 4.13; N, 3.59; Br, 20.45. Found (%): 56.65; H, 4.15; N, 3.57; Br, 20.36. IR (KBr, cm−1): 1591, 1489 (νCC); 1250, 1237 (νPN). χMcorr (293 K, cgsu): 1.50 × 10−2 (μ = 5.9 BM). 31P{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 300 K): δ 26.6 (s, FWHM = 50 Hz). M.p. (°C): 130 (mass loss > 230 °C).

- Characterization of [MnI2{(PhN=PPh2)CH2}]. Anal. calcd. for C37H32I2MnN2P2 (875.36 g mol−1, %): C, 50.77; H, 3.68; N, 3.20; I, 28.99. Found (%): 50.58; H, 3.70; N, 3.18; I, 28.88. IR (KBr, cm−1): 1591, 1489 (νCC); 1227 (νPN). χMcorr (293 K, cgsu): 1.47 × 10−2 (μ = 5.9 BM). 31P{1H} NMR (CDCl3, 300 K): δ 26.6 (s, FWHM = 35 Hz). M.p. (°C): 132 (mass loss > 230 °C).

3.4. Single-Crystal X-Ray Structure Determinations

3.5. Reflectance and Photoluminescence Measurements

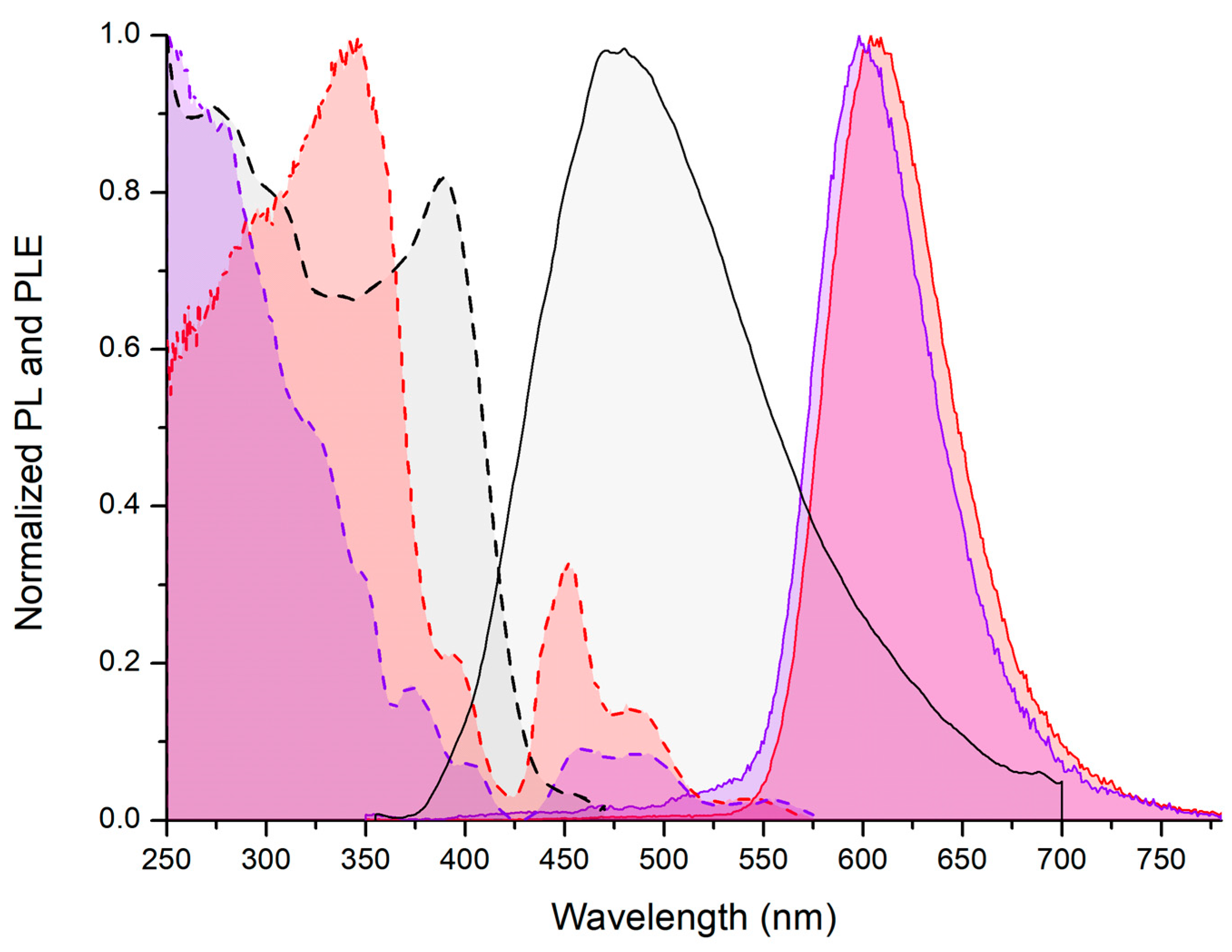

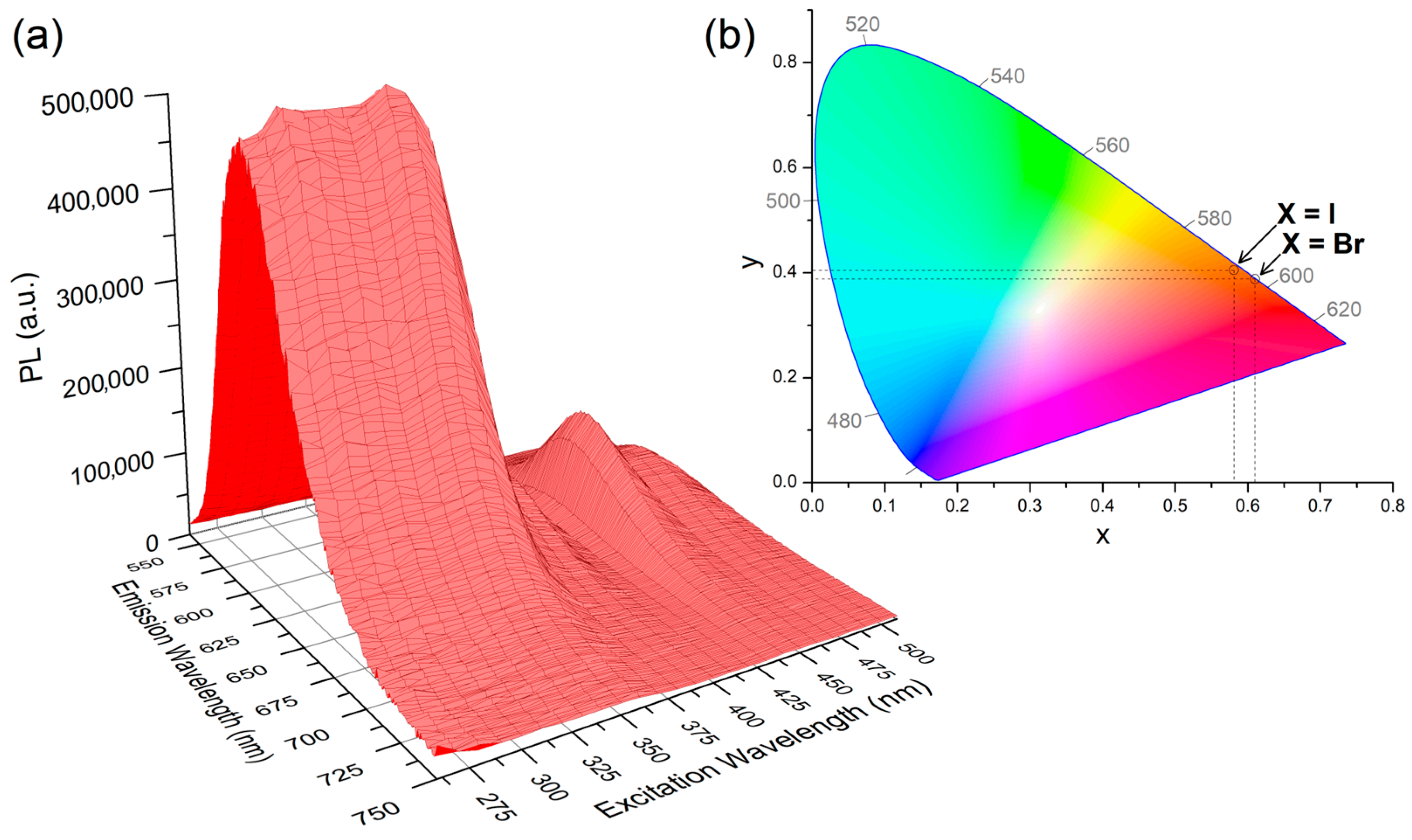

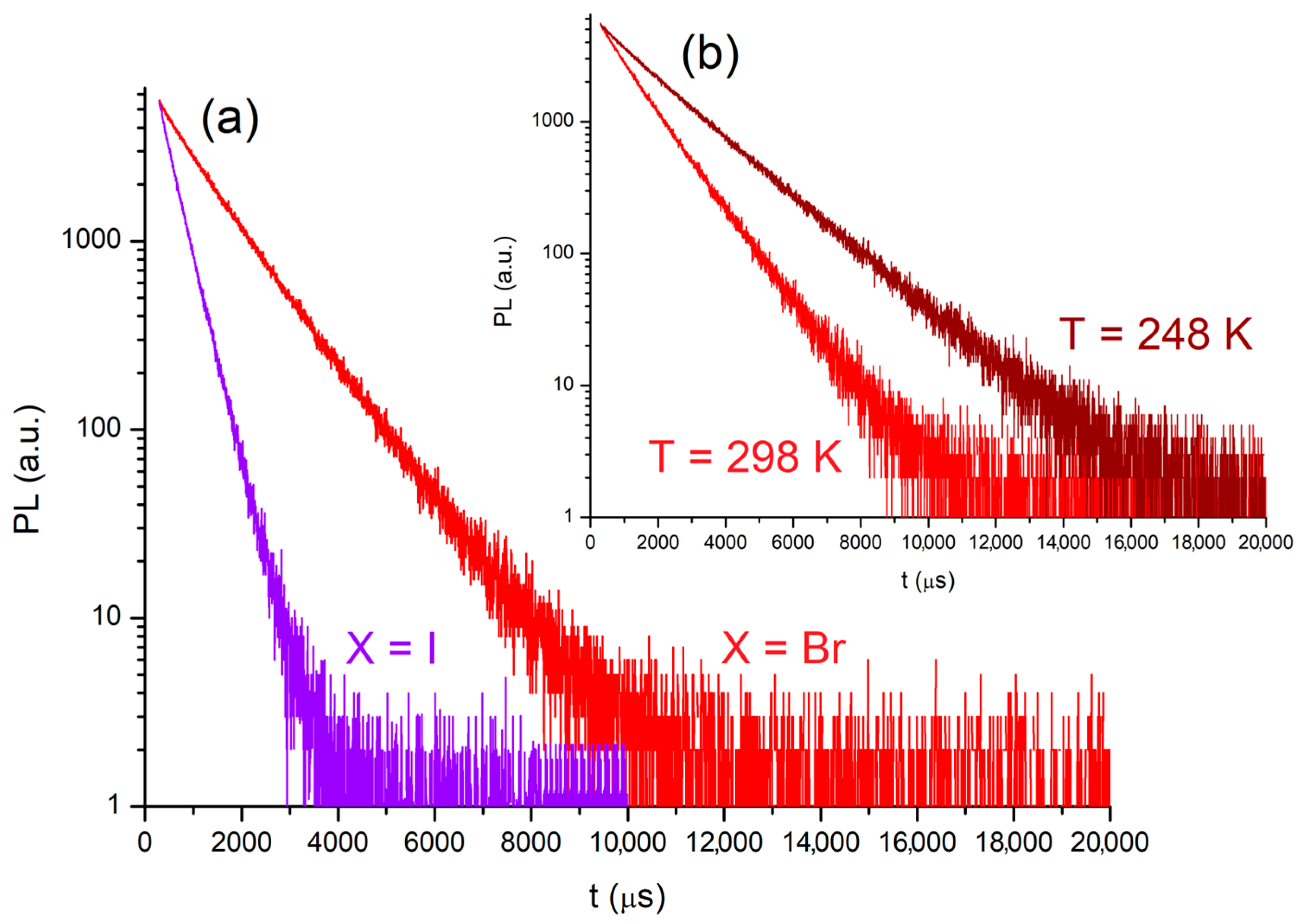

- Photoluminescence data for [MnBr2{(PhN=PPh2)CH2}]. PL (solid, λexcitation = 280 nm, 298 K, nm): 607 (FWHM = 1900 cm−1) 4T1(4G)→6A(6S). CIE 1931: x = 0.610; y = 0.388. PLE (solid, λemission = 610 nm, 298 K, nm): <385 (max 346) ligand-centred and metal-centred; 390–575 (local max 394, 450, 487, 543) metal-centred. τ (solid, λexcitation = 345 nm, λemission = 600 nm, μs): 1120 (T = 298 K), 1878 (T = 248 K). Φ (solid, λexcitation = 360 nm): 6%.

- Photoluminescence data for [MnI2{(PhN=PPh2)CH2}]. PL (solid, λexcitation = 280 nm, 298 K, nm): 598 (FWHM = 1900 cm−1) 4T1(4G)→6A(6S). CIE 1931: x = 0.581; y = 0.405. PLE (solid, λemission = 610 nm, 298 K, nm): <360 ligand-centred and metal-centred; 365–575 (local max 374, 403, 456, 491, 550) metal-centred. τ (solid, λexcitation = 300 nm, λemission = 600 nm, μs): 373 (T = 298 K).

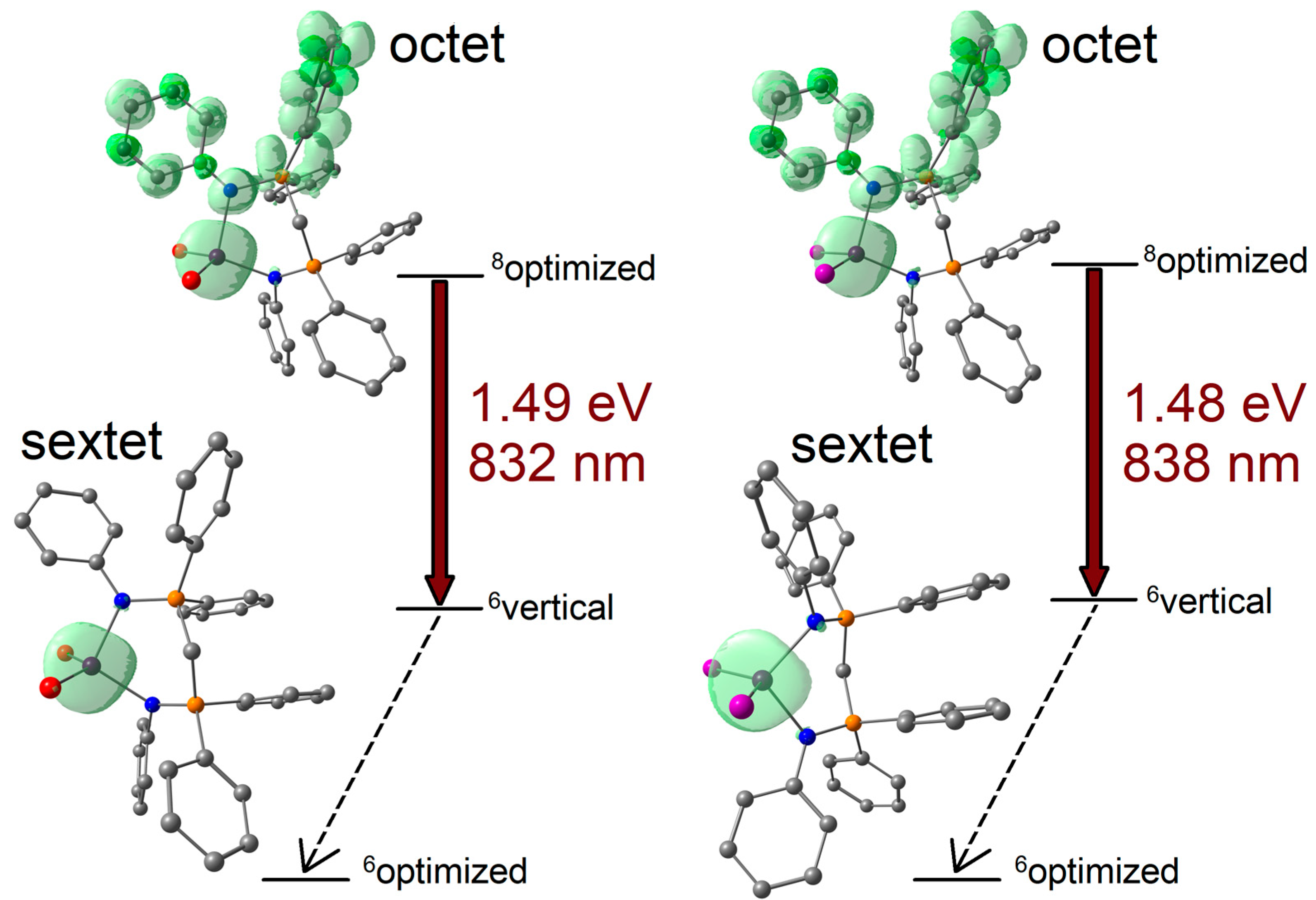

3.6. Computational Simulations of Single Molecules

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Miekisch, T.; Mai, H.J.; Meyer zu Köcker, R.; Dehnicke, K.; Magull, J.; Goesmann, H. Silylierte Phosphanimin-Komplexe von Chrom(II), Palladium(II) und Kupfer(II). Die Kristallstrukturen von [CrCl2(Me3SiNPMe3)2], [PdCl2(Me3SiNPEt3)2] und [CuCl2(Me3SiNPMe3)]2. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1996, 622, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer Zu Köcker, R.; Frenzen, G.; Neumüller, B.; Dehnicke, K.; Magull, J. Synthese und Kristallstrukturen der PhosphaniminKomplexe MCl2(Me3SiNPMe3)2 mit M = Zn und Co, und CoCl2(HNPMe3)2. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1994, 620, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhoff, P.; Elsevier, C.J.; Stam, C.H. Iminophosphorane complexes of rhodium(I) and X-ray crystal structure of [Rh(COD)Cl(Et3P=N-p-tolyl)]. Inorg. Chim. Acta 1990, 175, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, A.; Fenske, D.; Beck, J.; Strähle, J.; Böhm, E.; Dehnicke, K. Kupfer(I)-chlorid-Addukte von Phosphoraniminen Die Kristallstrukturen von Ph3PNPh·CuCl und von 2,3-Bis(triphenylphosphoranylidenamino)maleinsäure-N-methylimid-Kupfer(I)-chlorid. Z. Naturforsch. B 1988, 43, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenske, D.; Böhm, E.; Dehnicke, K.; Strähle, J. N-Trimethylsilyl-iminotriphenylphosphoran-Kupfer(II)-chlorid, [Me3SiNPPh3·CuCl2]2 Synthese und Kristallstruktur. Z. Naturforsch. B 1988, 43, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, E.W.; Mucklejohn, S.A.; Cameron, T.S.; Cordes, R.E. The Dimeric Phosphinimine Complex [CdI2(HN:PPh3)2]2 Containing N-H···I Hydrogen Bonds. Z. Naturforsch. B 1978, 33, 339–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, T.P.; Gutsch, P.A.; Zimmer, H. Complexes of N-Aryltriphenylphosphinimines with Mercury(II) Halides. Z. Naturforsch. B 1999, 54, 858–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venderbosch, B.; Oudsen, J.-P.H.; van der Vlugt, J.I.; Korstanje, T.J.; Tromp, M. Cationic Copper Iminophosphorane Complexes as CuAAC Catalysts: A Mechanistic Study. Organometallics 2020, 39, 3480–3489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Álvarez, J.; García-Garrido, S.E.; Cadierno, V. Iminophosphorane–phosphines: Versatile ligands for homogeneous catalysis. J. Organomet. Chem. 2014, 751, 792–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchard, A.; Auffrant, A.; Klemps, C.; Vu-Do, L.; Boubekeur, L.; Le Goffa, X.F.; Le Floch, P. Highly efficient P–N nickel(II) complexes for the dimerisation of ethylene. Chem. Commun. 2007, 15, 1502–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imhoff, P.; van Asselt, R.; Elsevier, C.J.; Zoutberg, M.C.; Stam, C.H. Reactions of bis(iminophosphoranyl)methanes with chlorobridged rhodium or iridium dimers giving complexes in which the ligand is coordinated either as a σ-N,σ-N′ or as a σ-N, σ-C chelate. X-ray crystal structure of the σ-N, σ-N′ Rh(I) complex Rh{(4-CH3-C6H4-N=PPh2)2CH2}(COD)]PF6. Inorg. Chim. Acta 1991, 184, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannoux, T.; Auffrant, A. Complexes featuring tridentate iminophosphorane ligands: Synthesis, reactivity, and catalysis. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 474, 214845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Benna, S.; Sarsfield, M.J.; Thornton-Pett, M.; Ormsby, D.L.; Maddox, P.J.; Brès, P.; Bochmann, M. Sterically hindered iminophosphorane complexes of vanadium, iron, cobalt and nickel: A synthetic, structural and catalytic study. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 2000, 23, 4247–4257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Karmakar, H.; Roesky, P.W.; Panda, T.K. Role of Bis(phosphinimino)methanides as Universal Ligands in the Coordination Sphere of Metals across the Periodic Table. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 13323–13373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, E.W.; Mucklejohn, S.A. The chemistry of phosphinimines. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 1981, 9, 235–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, F.A.; Daniels, L.M.; Huang, P. Correlation of structure and triboluminescence for tetrahedral manganese(II) compounds. Inorg. Chem. 2001, 40, 3576–3578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.-Y.; Wang, Z.-X.; Li, P.-F.; You, Y.-M.; Stroppa, A.; Xiong, R.-G. Brilliant triboluminescence in a potential organic–inorganic hybrid ferroelectric: (Ph3PO)2MnBr2. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2017, 4, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Qin, Y.; She, P.; Meng, H.; Liu, S.; Zhao, Q. Functionalized triphenylphosphine oxide-based manganese(II) complexes for luminescent printing. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 8831–8836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezin, A. Birefringence and polarized luminescence of a manganese(II) chloride–triphenylphosphine oxide compound: Application in LEDs and photolithography. Mater. Chem. Front. 2023, 7, 2475–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Gao, J.; Wang, S.; Xie, M.-J.; Li, B.-Y.; Wang, W.-F.; Mi, J.-R.; Zheng, F.-K.; Guo, G.-C. Improving X-ray Scintillating Merits of Zero-Dimensional Organic–Manganese(II) Halide Hybrids via Enhancing the Ligand Polarizability for High-Resolution Imaging. Nano Lett. 2023, 23, 4351–4358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; She, P.; Huang, X.; Huang, W.; Zhao, Q. Luminescent manganese(II) complexes: Synthesis, properties and optoelectronic applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2020, 416, 213331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, P.; Liu, S.-J.; Wong, W.-J. Phosphorescent manganese(II) complexes and their emerging applications. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2020, 8, 2000985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zheng, F.-K.; Liu, Z.-F.; Wang, S.-H.; Wu, A.-Q.; Guo, G.-C. Intense photo- and tribo-luminescence of three tetrahedral manganese(II) dihalides with chelating bidentate phosphine oxide ligand. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 3289–3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Y.; Tao, P.; Gao, L.; She, P.; Liu, S.; Li, X.; Li, F.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Q.; Miao, Y.; et al. Designing Highly Efficient Phosphorescent Neutral Tetrahedral Manganese(II) Complexes for Organic Light-Emitting Diodes. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2019, 7, 1801160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artem’ev, A.V.; Davydova, M.P.; Rakhmanova, M.I.; Bagryanskaya, I.Y.; Pishchur, D.P. A family of Mn(II) complexes exhibiting strong photo- and triboluminescence as well as polymorphic luminescence. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2021, 8, 3767–3774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, G.-H.; Chen, Y.-N.; Chuang, Y.-T.; Lin, H.-C.; Hsieh, C.-A.; Chen, Y.-S.; Lee, T.-Y.; Miao, W.-C.; Kuo, H.-C.; Chen, L.-Y.; et al. Highly Luminescent Earth-Benign Organometallic Manganese Halide Crystals with Ultrahigh Thermal Stability of Emission from 4 to 623 K. Small 2023, 19, 2205981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- She, P.; Zheng, Z.; Qin, Y.; Li, F.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, D.; Xie, Z.; Duan, L.; Wong, W.-Y. Color Tunable Phosphorescent Neutral Manganese(II) Complexes Through Steric Hindrance Driven Bond Angle Distortion. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2024, 12, 2302132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Z.-Z.; Wang, Y.; Yang, B.; Liang, J.-Q.; Hong, X.-F.; An, Q.; Yuan, L.; Ma, H.; Zuo, J.-L.; Zheng, Y.-X. Circularly Polarized Electroluminescence from Chiral Manganese(II) Complexes. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2025, 13, 2402684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artem’ev, A.V.; Davydova, M.P.; Berezin, A.S.; Brel, V.K.; Morgalyuk, V.P.; Bagryanskaya, I.Y.; Samsonenko, D.G. Luminescence of the Mn2+ ion in non-Oh and Td coordination environments: The missing case of square pyramid. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 16448–16456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, H.; Zhu, W.; Li, F.; Huang, X.; Qin, Y.; Liu, S.; Yang, Y.; Huang, W.; Zhao, Q. Highly emissive and stable five-coordinated manganese(II) complex for X-ray imaging. Laser Photonics Rev. 2021, 15, 2100309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Meng, H.; Li, F.; Jiang, T.; Yang, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhao, Q. Highly Luminescent Nonclassical Binuclear Manganese(II) Complex Scintillators for Efficient X-ray Imaging. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 62, 5279–5736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Jiang, T.; Yang, Y.; Deng, Y.; Wang, M.; Ma, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhao, Q. Multifunctional Chiral Five-Coordinated Manganese(II) Complexes for White LED and X-Ray Imaging Applications. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2024, 12, 2302185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortoluzzi, M.; Castro, J.; Trave, E.; Dallan, D.; Favaretto, S. Orange-emitting manganese(II) complexes with chelating phosphine oxides. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2018, 90, 105–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezin, A.S.; Samsonenko, D.G.; Brel, V.K.; Artem’ev, A.V. “Two-in-one” organic–inorganic hybrid MnII complexes exhibiting dual-emissive phosphorescence. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 7306–7315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezin, A.S.; Davydova, M.P.; Bagryanskaya, I.Y.; Artyushin, O.I.; Brel, V.K.; Artem’ev, A.V. A red-emitting Mn(II)-based coordination polymer build on 1,2,4,5-tetrakis(diphenylphosphinyl)benzene. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2019, 107, 107473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydova, M.P.; Bauer, I.A.; Brel, V.K.; Rakhmanova, M.I.; Bagryanskaya, I.Y.; Artem’ev, A.V. Manganese(II) thiocyanate complexes with bis(phosphine oxide) ligands: Synthesis and excitation wavelength-dependent multicolor luminescence. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 2020, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xu, L.-J.; Yang, M.; Chen, Z.-N. Luminescent vapochromism due to a change of the ligand field in a one-dimensional manganese(II) coordination polymer. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 9175–9181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.-Q.; Yang, M.; Chen, Z.-N. Achievement of ligand-field induced thermochromic luminescence via two-step single-crystal to single-crystal transformations. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 13961–13964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artem’ev, A.V.; Davydova, M.P.; Berezin, A.S.; Sukhikh, T.S.; Samsonenko, D.G. Photo- and triboluminescent robust 1D polymers made of Mn(II) halides and meta-carborane based bis(phosphine oxide). Inorg. Chem. Front. 2021, 8, 2261–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydova, M.P.; Meng, L.; Rakhmanova, M.I.; Jia, Z.; Berezin, A.S.; Bagryanskaya, I.Y.; Lin, Q.; Meng, H.; Artem’ev, A.V. Strong Magnetically-Responsive Circularly Polarized Phosphorescence and X-Ray Scintillation in Ultrarobust Mn(II)–Organic Helical Chains. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2303611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, H.-J.; Wocadlo, S.; Massa, W.; Weller, F.; Dehnicke, K.; Maichle-Mössmer, C.; Strähle, J. Phosphanimin-Komplexe von Mangan(II)halogeniden. Die Kristallstrukturen von [MnCl2(Me3SiNPEt3)]2, [MnI2(Me3SiNPEt3)2] und [MnI2(Me2Si(NPEt3)2)]. Z. Naturforsch. B 1995, 50, 1215–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.J.; Hill, M.S.; Hitchcock, P.B. Tuning low-coordinate metal environments: High spin d5–d7 complexes supported by bis(phosphinimino)methyl ligation. Dalton Trans. 2003, 4, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.S.; Hitchcock, P.B. Three-coordinate bis(phosphinimino)methanide derivatives of ‘open shell’ [M(II)] (M = Mn, Fe, Co) transition metals. J. Organomet. Chem. 2004, 689, 3163–3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccolo, D.; Castro, J.; Rosa-Gastaldo, D.; Bortoluzzi, M. Luminescent Manganese(II) Iminophosphorane Derivatives. Molecules 2025, 30, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bader, R.F.W.; Hernández-Trujillo, J.; Cortés-Guzmán, F. Chemical bonding: From Lewis to atoms in molecules. J. Comput. Chem. 2007, 28, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortoluzzi, M.; Castro, J.; Gobbo, A.; Ferraro, V.; Pietrobon, L. Light harvesting indolyl-substituted phosphoramide ligand for the enhancement of Mn(II) luminescence. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 7525–7534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riese, U.; Faza, N.; Massa, W.; Harms, K.; Breyhan, T.; Knochel, P.; Ensling, J.; Ksenofontov, V.; Gütlich, P.; Dehnicke, K. Phosphoraneiminato Complexes of Manganese and Cobalt with Heterocubane Structure. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1999, 625, 1494–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortoluzzi, M.; Castro, J. Dibromomanganese(II) complexes with hexamethylphosphoramide and phenylphosphonic bis(amide) ligands. J. Coord. Chem. 2019, 72, 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortoluzzi, M.; Castro, J.; Gobbo, A.; Ferraro, V.; Pietrobon, L.; Antoniutti, S. Tetrahedral photoluminescent manganese(II) halide complexes with 1,3-dimethyl-2-phenyl-1,3-diazaphospholidine-2-oxide as a ligand. New J. Chem. 2020, 44, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremer, D.; Pople, J.A. General definition of ring puckering coordinates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975, 97, 1354–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodgame, D.M.L.; Cotton, F.A. Phosphine oxide complexes. Part V. Tetrahedral complexes of manganese(II) containing triphenylphosphine oxide, and triphenylarsine oxide as ligands. J. Chem. Soc. 1961, 3735–3741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrighton, M.; Ginley, D. Excited state decay of tetrahalomanganese(II) complexes. Chem. Phys. 1974, 4, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortoluzzi, M.; Ferraro, V.; Castro, J. Synthesis and photoluminescence of manganese(II) naphtylphosphonic diamide complexes. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 3132–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortoluzzi, M.; Castro, J.; Ferraro, V. Dual emission from Mn(II) complexes with carbazolyl-substituted phosphoramides. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2022, 536, 120896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, V.; Castro, J.; Agostinis, L.; Bortoluzzi, M. Dual-emitting Mn(II) and Zn(II) halide complexes with 9,10-dihydro-9-oxa-10-phosphaphenanthrene-10-oxide as ligand. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2023, 545, 121285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, V.; Castro, J.; Bortoluzzi, M. Luminescent Behavior of Zn(II) and Mn(II) Halide Derivatives of 4-Phenyldinaphtho[2,1-d:1′,2′-f][1,3,2]dioxaphosphepine 4-Oxide and Single-Crystal X-ray Structure Determination of the Ligand. Molecules 2024, 29, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.-H.; Wu, Y.; Shi, C.-M.; Zeng, H.; Xu, L.-J.; Chen, Z.-N. Highly efficient circularly polarized electroluminescence based on chiral manganese(II) complexes. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 16698–16704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Dronskowski, R.; Glaum, R.; Tchougréeff, A.L. Experimental and Quantum-Chemical Investigations of the UV/Vis Absorption Spectrum of Manganese Carbodiimide, MnNCN. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2010, 636, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortoluzzi, M.; Castro, J.; Enrichi, F.; Vomiero, A.; Busato, M.; Huang, W. Green-emitting manganese(II) complexes with phosphoramide and phenylphosphonic diamide ligands. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2018, 92, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortoluzzi, M.; Castro, J.; Di Vera, A.; Palù, A.; Ferraro, V. Manganese(II) bromo- and iodo-complexes with phosphoramidate and phosphonate ligands: Synthesis, characterization and photoluminescence. New J. Chem. 2021, 45, 12871–12878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yersin, H.; Rausch, A.F.; Czerwieniec, R.; Hofbeck, T.; Fischer, T. The triplet state of organo-transition metal compounds. Triplet harvesting and singlet harvesting for efficient OLEDs. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2011, 255, 2622–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armarego, W.L.F.; Chai, C.L.L. Purification of Laboratory Chemicals, 4th ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 1996; pp. 67–68, 176, 215–216. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay, R.O.; Allen, C.F.H. Phenyl azide. Org. Synth. 1942, 22, 96–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhoff, P.; Van Asselt, R.; Elsevier, C.J.; Vrieze, K.; Goubitz, K.; Van Malssen, K.F.; Stam, C.H. Synthesis, structure and reactivity of bis(N-aryl-iminophosphoranyl)methanes. X-Ray crystal structures of (4-CH3-C6H4-N=PPh2)2CH2 and (4-NO2-C6H4-N=PPh2)2CH2. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 1990, 47, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deucher, N.C.; Silva de Souza, R., Jr.; Borges, E.M. Teaching Precipitation Titration Methods: A Statistical Comparison of Mohr, Fajans, and Volhard Techniques. J. Chem. Educ. 2025, 102, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, G.A.; Berry, J.F. Diamagnetic corrections and Pascal’s constants. J. Chem. Educ. 2008, 85, 532–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APEX5; v.2023.9-4; Bruker AXS Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 2023.

- SAINT; v.8.40B; Bruker AXS Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 2022.

- Krause, L.; Herbst-Irmer, R.; Sheldrick, G.M.; Stalke, D. Comparison of silver and molybdenum microfocus X-ray sources for single-crystal structure determination. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2015, 48, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McArdle, P. Oscail, a program package for small-molecule single-crystal crystallography with crystal morphology prediction and molecular modelling. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2017, 50, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT—Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. 2015, A71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. 2015, C71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spek, A.L. checkCIF validation ALERTS: What they mean and how to respond. Acta Crystallogr. 2020, E76, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staroverov, V.N.; Scuseria, E.; Tao, J.; Perdew, J.P. Comparative assessment of a new nonempirical density functional: Molecules and hydrogen-bonded complexes. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 119, 12129–12137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigend, F.; Ahlrichs, R. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigend, F. Accurate Coulomb-fitting basis sets for H to Rn. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2006, 8, 1057–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, K.A.; Figgen, D.; Goll, E.; Stoll, H.; Dolg, M. Systematically convergent basis sets with relativistic pseudopotentials. II. Small-core pseudopotentials and correlation consistent basis sets for the post-d group 16–18 elements. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 119, 11113–11123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeweyher, E.; Ehlert, S.; Hansen, A.; Neugebauer, H.; Spicher, S.; Bannwarth, C.; Grimme, S.A. Generally applicable atomic-charge dependent London dispersion correction. J. Chem. Phys. 2019, 150, 154122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, C.J. Essentials of Computational Chemistry, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Neese, F. The ORCA program system. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012, 2, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F. Software update: The ORCA program system-Version 5.0. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2022, 12, e1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Chen, F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T. A comprehensive electron wavefunction analysis toolbox for chemists. Multiwfn. J. Chem. Phys. 2024, 161, 082503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, S.; Alemany, P.; Casanova, D.; Cirera, J.; Llunell, M.; Avnir, D. Shape maps and polyhedral interconversion paths in transition metal chemistry. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2005, 249, 1693–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirera, J.; Alemany, P.; Álvarez, S. Mapping the Stereochemistry and Symmetry of Tetracoordinate Transition-Metal Complexes. Chem. Eur. J. 2004, 10, 190–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Powell, D.R.; Houser, R.P. Structural variation in copper(I) complexes with pyridylmethylamide ligands: Structural analysis with a new four-coordinate geometry index, τ4. Dalton Trans. 2007, 9, 955–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuniewski, A.; Rosiak, D.; Chojnacki, J.; Becker, B. Coordination polymers and molecular structures among complexes of mercury(II) halides with selected 1-benzoylthioureas. Polyhedron 2015, 90, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Ruzsinszky, A.; Csonka, G.I.; Vydrov, O.A.; Scuseria, G.E.; Constantin, L.A.; Zhou, X.; Burke, K. Restoring the Density-Gradient Expansion for Exchange in Solids and Surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 136406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.S.; Qteish, A.; Payne, M.C.; Heine, V. Optimized and transferable nonlocal separable ab initio pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. B 1993, 47, 4174–4180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tkatchenko, A.; Scheffler, M. Accurate Molecular Van Der Waals Interactions from Ground-State Electron Density and Free-Atom Reference Data. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 102, 073005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelling, D.D.; Harmon, B.N. A technique for relativistic spin-polarised calculations. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 1977, 10, 3107–3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S.J.; Segall, M.D.; Pickard, C.J.; Hasnip, P.J.; Probert, M.I.J.; Refson, K.; Payne, M.C. First principles methods using CASTEP. Z. Krist. 2005, 220, 567–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, M.J. C2x: A tool for visualisation and input preparation for Castep and other electronic structure codes. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2018, 225, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Piccolo, D.; Castro, J.; Beghetto, V.; Rosa-Gastaldo, D.; Bortoluzzi, M. Unexpected Orange Photoluminescence from Tetrahedral Manganese(II) Halide Complexes with Bidentate Phosphanimines. Molecules 2026, 31, 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010161

Piccolo D, Castro J, Beghetto V, Rosa-Gastaldo D, Bortoluzzi M. Unexpected Orange Photoluminescence from Tetrahedral Manganese(II) Halide Complexes with Bidentate Phosphanimines. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):161. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010161

Chicago/Turabian StylePiccolo, Domenico, Jesús Castro, Valentina Beghetto, Daniele Rosa-Gastaldo, and Marco Bortoluzzi. 2026. "Unexpected Orange Photoluminescence from Tetrahedral Manganese(II) Halide Complexes with Bidentate Phosphanimines" Molecules 31, no. 1: 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010161

APA StylePiccolo, D., Castro, J., Beghetto, V., Rosa-Gastaldo, D., & Bortoluzzi, M. (2026). Unexpected Orange Photoluminescence from Tetrahedral Manganese(II) Halide Complexes with Bidentate Phosphanimines. Molecules, 31(1), 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010161