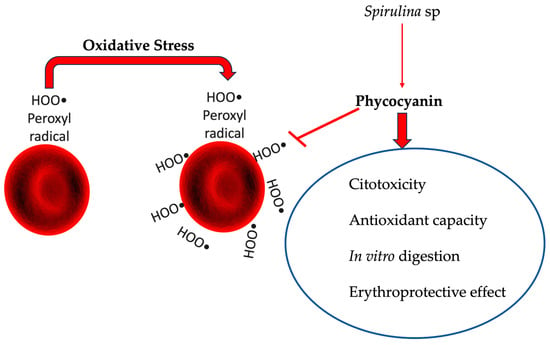

Antioxidant and Erythroprotective Effects of C-Phycocyanin from the Cyanobacterium Spirulina sp. in Attenuating Oxidative Stress Induced by Peroxyl Radicals

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Quantification of the Antioxidant Capacity of Phycocyanin Before and After Digestion In Vitro

Antioxidant Capacity

2.2. Cytotoxic and Erythroprotective Effects Before and After In Vitro Digestion

2.2.1. Cytotoxicity of C-PC from the Cyanobacterium Spirulina sp. at Different Concentrations Before In Vitro Digestion

2.2.2. Erythroprotection of C-Phycocyanin from the Cyanobacterium Spirulina sp. at Different Concentrations After an In Vitro Digestion

2.2.3. Cytotoxic Effect of IC50 of C-PC After In Vitro Digestion

2.2.4. Cytotoxic Effect of C-PC Before In Vitro Digestion

2.3. Erythroprotection Assays Before and After In Vitro Digestion

2.3.1. Erythroprotection of C-PC Using Its IC50 Before In Vitro Digestion

2.3.2. Erythroprotective Effect of C-Phycocyanin After In Vitro Digestion

2.4. Damage to Erythrocytes Observed Using Immersion Optical Microscopy

2.4.1. Microscope Images of Blood Type O+

2.4.2. Microscope Images of Blood Type O−

3. Discussion

3.1. Quantifying the Antioxidant Capacity of C-Phycocyanin Before and After Digestion In Vitro Digestion

Antioxidant Capacity

3.2. Cytotoxic and Erythroprotective Effects Before and After In Vitro Digestion

3.2.1. Cytotoxic Effect of IC50 of C-Phycocyanin

3.2.2. Cytotoxic Effect of C-Phycocyanin After In Vitro Digestion

3.2.3. Erythroprotection of C-PC Using Its IC50 Prior to In Vitro Digestion

3.2.4. Erythroprotective Effect of C-Phycocyanin After In Vitro Digestion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents

4.2. Quantification of the Antioxidant Capacity of C-Phycocyanin Before and After In Vitro Digestion

4.2.1. Assay to Evaluate the Free Radical Inhibition Capacity of 2,2-Azinobis-(3-ethylbenzothiazolin)-6-sulfonic Acid (ABTS+•)

4.2.2. Assay to Evaluate the Free Radical Inhibition Capacity of 1,1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH•)

4.2.3. Evaluation of the Reducing Capacity of Ferric Ions (Fe3+) Using the FRAP Test (Ferric Ion Reducing Antioxidant Power)

4.3. In Vitro Digestion

4.4. Cytotoxic and Erythroprotective Effect

4.4.1. Erythrocyte Cytotoxicity Assay

4.4.2. Erythroprotection Assay, Quantifying Antihemolytic Activity in Erythrocytes by 2,2′-Azobis-(2-methylpropionic acid-(2-methylpropionamidine) (AAPH)

4.5. Erythrocyte Cell Membrane

5. Statistical Analysis

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAPH | 2,2-Azobis(2-methylpropionamidine) dihydrochloride |

| ABTS | 2,2-azino-bis-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid |

| APC | Allophycocyanin |

| B-PE | B-Phycoerythrin |

| C-PC | C-Phycocyanin |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| DW | Dry Weight |

| FRAP | Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power |

| PBP | Phycobiliprotein |

| PSU | Practical Salinity Units |

| PS | Physiological Solution |

| R-PC | R-Phycocyanin |

| TPTZ | 2,4,6-Tripridil-s-triazine |

| Trolox | 6-hydroxy -2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid |

References

- Alcides González Gil, L.; Yisel González Madariaga, I.; Dra Grecia Martínez Leyva, I.; Felipe Hernández Ugalde, I.; Adalberto Suárez González, I.V. Daño oxidativo en un modelo experimental de hiperglicemia e hiperlipidemia inducida por sacarosa en ratas wistar. Rev. Médica Electrónica 2012, 34, 406–416. [Google Scholar]

- Alfaro-Alfaro, Á.E.; Alpízar-Cambronero, V.; Duarte-Rodríguez, A.I.; Feng-Feng, J.; Rosales-Leiva, C.; Mora-Román, J.J. C-ficocianinas: Modulación del sistema inmune y su posible aplicación como terapia contra el cáncer. Rev. Tecnol. Marcha 2020, 33, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, N.A.V.; Caicedo, C.R. Análisis bibliométrico del efecto de la luz en la producción de ficobiliproteínas. TecnoLógicas 2022, 25, e2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlos, S.-B.; Celestino, G.-G.; Claudio, G.-B.; Julia, M.-R.; Juan, N.-A.; Julio, B.-R.; Villa, F.S.; Escobedo, G.; León, N. Optimización para la extracción de ficocianina de la cianobacteria Spirulina maxima. Investig. Desarro. Cienc. Tecnol. Aliment. 2023, 8, 834–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citi, V.; Torre, S.; Flori, L.; Usai, L.; Aktay, N.; Dunford, N.T.; Lutzu, G.A.; Nieri, P. Nutraceutical Features of the Phycobiliprotein C-Phycocyanin: Evidence from Arthrospira platensis (Spirulina). Nutrients 2024, 16, 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, X.; Liang, Z.P.; Chang, X.Y.; Li, F.T.; Wang, X.Q.; Lian, X.J. Progress of Microencapsulated Phycocyanin in Food and Pharma Industries: A Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 5854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minic, S.L.; Stanic-Vucinic, D.; Mihailovic, J.; Krstic, M.; Nikolic, M.R.; Cirkovic Velickovic, T. Digestion by pepsin releases biologically active chromopeptides from C-phycocyanin, a blue-colored biliprotein of microalga Spirulina. J. Proteom. 2016, 147, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, M.N.; Orrico, F.; Villar, S.F.; López, A.C.; Silva, N.; Donzé, M.; Thomson, L.; Denicola, A. Oxidants and Antioxidants in the Redox Biochemistry of Human Red Blood Cells. ACS Omega 2022, 8, 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Kunwar, A.; Mishra, B.; Priyadarsini, K.I. Concentration dependent antioxidant/pro-oxidant activity of curcumin. Studies from AAPH induced hemolysis of RBCs. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2008, 174, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeagu, E.I.; Igwe, M.C.; Obeagu, G.U. Oxidative stress’s impact on red blood cells: Unveiling implications for health and disease. Medicine 2024, 103, e37360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orrico, F.; Laurance, S.; Lopez, A.C.; Lefevre, S.D.; Thomson, L.; Möller, M.N.; Ostuni, M.A. Oxidative Stress in Healthy and Pathological Red Blood Cells. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Alarcón, C.; Fuentes-Lemus, E.; Figueroa, J.D.; Dorta, E.; Schöneich, C.; Davies, M.J. Azocompounds as generators of defined radical species: Contributions and challenges for free radical research. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 160, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tawa, M.; Okamura, T. Factors influencing the soluble guanylate cyclase heme redox state in blood vessels. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2022, 145, 107023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvajal Carvajal, C. Especies reactivas del oxígeno: Formación, funcion y estrés oxidativo. Med. Leg. Costa Rica 2019, 36, 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Alchazal, R.; Zaitoun, K.J.; Al-Qudah, M.; Zaitoun, G.; Taha, A.M.; Saleh, O.; Alqudah, M.; Abuawwad, M.; Taha, M.; Aldalati, A.Y. Relationship between ABO blood group antigens and Rh factor with breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2025, 16, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi-Pooya, A.A.; Namjoo-Moghadam, A.; Cheraghipour, M. ABO blood group and Rh factor dis-tributions in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2022, 128, 108567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, O. Are ABO/Rh blood groups A risk factor for polycystic ovary syndrome? Medicine 2023, 102, e34944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Alarcón, C.G.; García-Ruíz, A.; Cañete-Ibáñez, C.R.; Morales-Pogoda, I.I.; Muñoz-Arce, C.M.; Cid-Domínguez, B.E.; Montalvo-Bárcenas, M.; Maza-de la Torre, G.; Sandoval-López, C.; Gaytán-Guzmán, E.; et al. Antígenos del sistema sanguíneo ABO como factor de riesgo para la gravedad de la infección por SARS-CoV-2. Gac. Médica México 2021, 157, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Yang, Y.; Huang, H.; Li, D.; Gu, D.; Lu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, L.; Liu, T.; Liu, Y.; et al. Relationship between the ABO Blood Group and the COVID-19 Susceptibility. MedRxiv 2020, 2020.03.11.20031096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.F.; Strain, J.J. The Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma (FRAP) as a Measure of “Antioxidant Power”: The FRAP Assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Vega, R.I.; Robles-García, M.Á.; Mendoza-Urizabel, L.Y.; Cárdenas-Enríquez, K.N.; Ruiz-Cruz, S.; Gutié-rrez-Lomelí, M.; Iturralde-García, R.D.; Avila-Novoa, M.G.; Villalpando-Vargas, F.V.; Del-Toro-Sánchez, C.L. Impact of the ABO and RhD Blood Groups on the Evaluation of the Erythroprotective Potential of Fucoxanthin, β-Carotene, Gallic Acid, Quercetin and Ascorbic Acid as Therapeutic Agents against Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halliwell, B. Reactive species and antioxidants. Redox biology is a fundamental theme of aerobic life. Plant Physiol. 2006, 141, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 10993-4; Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices—Part 4: Selection of Tests for Interactions with Blood. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Hernández-Ruiz, K.L.; Ruiz-Cruz, S.; Cira-Chávez, L.A.; Gassos-Ortega, L.E.; de Jesús Ornelas-Paz, J.; Del-Toro-Sánchez, C.L.; Márquez-Ríos, E.; López-Mata, M.A.; Rodríguez-Félix, F. Evaluation of antioxidant capacity, protective effect on human erythrocytes and phenolic compound identification in two varieties of plum fruit (Spondias spp.) by UPLC-MS. Molecules 2018, 23, 3200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Su, H.N.; Pu, Y.; Chen, J.; Liu, L.N.; Liu, Q.; Qin, S. Phycobiliproteins: Molecular structure, production, applications, and prospects. Biotechnol. Adv. 2019, 37, 340–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, M.F. Clinical potential of Spirulina as a source of phycocyanobilin. J. Med. Food 2007, 10, 566–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozgen, M.; Reese, R.N.; Tulio, A.Z.; Scheerens, J.C.; Miller, A.R. Modified 2,2-azino-bis-3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS) method to measure antioxidant capacity of selected small fruits and comparison to ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) and 2,2′-diphenyl-1- picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) methods. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 1151–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parcheta, M.; Świsłocka, R.; Orzechowska, S.; Akimowicz, M.; Choińska, R.; Lewandowski, W. Recent developments in effective antioxidants: The structure and antioxidant properties. Materials 2021, 14, 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an im-proved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Roque, M.J.; Del-Toro-sánchez, C.L.; Chávez-Ayala, J.M.; González-Vega, R.I.; Pérez-Pérez, L.M.; Sán-chez-Chávez, E.; Salas-Salazar, N.A.; Soto-Parra, J.M.; Iturralde-García, R.D.; Flores-Córdova, M.A. Digestibility, Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Pecan Nutshell (Carya illioinensis) Extracts. J. Renew. Mater. 2022, 10, 2569–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Hernández, Y.A.; Garza-Valverde, E.; Márquez-Reyes, J.R.; García-Gómez, C. Extracción de ficocianina para uso como colorante natural: Optimización por metodología de superficie de respuesta. Investig. Desarro. Cienc. Tecnol. Aliment. 2023, 8, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeer, N.B.; Montesano, D.; Albrizio, S.; Zengin, G.; Mahomoodally, M.F. The versatility of antioxidant assays in food science and safety—Chemistry, applications, strengths, and limitations. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddeeg, A.; AlKehayez, N.M.; Abu-Hiamed, H.A.; Al-Sanea, E.A.; AL-Farga, A.M. Mode of action and determination of antioxidant activity in the dietary sources: An overview. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 1633–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample | ABTS+• | DPPH• | FRAP |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-PC before digestion in vitro | 1.58 Ba ± 0.42 | 1.32 ABa ± 0.08 | 0.03 Cb ± 0.02 |

| Bioaccessible Fraction | 6.97 Aa ± 0.42 | 1.21 bA ± 0.48 | 0.13 Ac ± 0.01 |

| Bioavailable Fraction | 7.34 Aa ± 0.08 | 0.89 Ab ± 0.42 | 0.07 Bc ± 0.01 |

| µg/mL | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABO Rh +/− * | 50 | 75 | 100 | 125 | 150 | 300 | AAPH |

| A+ | 0 A ± 1.35 | 0 A ± 1.10 | 0.58 A ± 0.59 | 0.29 A ± 0.54 | 2.26 A ± 1.58 | 1.47 B ± 0.47 | 25.13 ABC ± 2.53 |

| A− | 0 B ± 0.21 | 0.12 A ± 0.77 | 0 A ± 0.78 | 0 A ± 1.68 | 0 B ± 1.66 | 0.65 B ± 1.44 | 20.95 E ± 0.96 |

| O+ | 0 A ± 0.97 | 0.03 A ± 1.26 | 0 A ± 0.83 | 0.34 A ± 0.85 | 0.04 B ± 0.81 | 1.13 A ± 0.94 | 27.01 AB ± 0.49 |

| O− | 0 A ± 0.89 | 0 A ± 0.39 | 0 A ± 0.37 | 0 A ± 0.93 | 0 B ± 0.91 | 0 B ± 1.31 | 26.23 BC ± 0.97 |

| B+ | 0.97 A ± 0.75 | 0.43 A ± 0.95 | 0 A ± 0.44 | 0 A ± 0.35 | 0 B ± 1.41 | 0.98 A ± 2.03 | 25.29 C ± 0.55 |

| AB+ | 0 A ± 0.73 | 0.25 A ± 0.90 | 0 A ± 0.51 | 0 A ± 2 | 1.01 B ± 0.61 | 2 A ± 0.5 | 23.35 D ± 1.24 |

| AB− | 0 A ± 0.77 | 0 A ± 0.50 | 0 A ± 0.91 | 0.70 A ± 0.39 | 0.28 B ± 0.95 | 1.75 AB ± 0.30 | 28.10 A ± 1.00 |

| ABO Rh +/− * | C-PC µg/mL | Equation | R2 | Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A+ | 82.66 | y = 0.5216x + 6.8853 | 0.9593 | Linear |

| A− | 95.25 | y = −0.0055x2 + 1.0478x + 1.0108 | 0.9352 | Polynomial |

| O+ | 92.53 | y = 0.5512x − 1.0054 | 0.9896 | Linear |

| O− | 82.05 | y = −0.0072x2 + 1.1813x + 1.5912 | 0.9316 | Polynomial |

| B+ | 88.26 | y = 0.4973x + 6.1085 | 0.9677 | Linear |

| AB+ | 104.37 | y = −0.0057x2 + 1.1897x + 1.3272 | 0.9704 | Polynomial |

| AB− | 101.94 | y = −0.0051x2 + 1.0397x + 0.0859 | 0.9986 | Polynomial |

| Bood Type | µg/mL | % Hemolysis Inhibition |

|---|---|---|

| A+ | 82.66 | 50.08 ± 1.7 |

| A− | 95.25 | 48.58 ± 1.9 |

| O+ | 92.53 | 50.07 ± 1.3 |

| O− | 82.05 | 50.70 ± 0.7 |

| B+ | 88.26 | 50.96 ± 1.1 |

| AB+ | 104.37 | 50.27 ± 1.9 |

| AB− | 101.94 | 49.95 ± 1.7 |

| In Vitro Digestion | Sample or Reagent | Volume | Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-phycocyanin | C-PC | 0.5 mL | 1 mg/mL |

| α-amylase | 1 mL | Human origin | |

| Physiological solution | 1 mL | 0.9% | |

| Pepsin | 1 mL | 315 U/mL | |

| Pancreatin | 700 µL | 4 mg/mL |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gaxiola-Calvo, C.J.; Fimbres-Olivarría, D.; González-Vega, R.I.; Cornejo-Ramírez, Y.I.; Bernal-Mercado, A.T.; Ruiz-Cruz, S.; Ornelas-Paz, J.d.J.; Robles-García, M.Á.; Ramos-Enríquez, J.R.; Del-Toro-Sánchez, C.L. Antioxidant and Erythroprotective Effects of C-Phycocyanin from the Cyanobacterium Spirulina sp. in Attenuating Oxidative Stress Induced by Peroxyl Radicals. Molecules 2026, 31, 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010169

Gaxiola-Calvo CJ, Fimbres-Olivarría D, González-Vega RI, Cornejo-Ramírez YI, Bernal-Mercado AT, Ruiz-Cruz S, Ornelas-Paz JdJ, Robles-García MÁ, Ramos-Enríquez JR, Del-Toro-Sánchez CL. Antioxidant and Erythroprotective Effects of C-Phycocyanin from the Cyanobacterium Spirulina sp. in Attenuating Oxidative Stress Induced by Peroxyl Radicals. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):169. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010169

Chicago/Turabian StyleGaxiola-Calvo, Cinthia Jael, Diana Fimbres-Olivarría, Ricardo Iván González-Vega, Yaeel Isbeth Cornejo-Ramírez, Ariadna Thalía Bernal-Mercado, Saul Ruiz-Cruz, José de Jesús Ornelas-Paz, Miguel Ángel Robles-García, José Rogelio Ramos-Enríquez, and Carmen Lizette Del-Toro-Sánchez. 2026. "Antioxidant and Erythroprotective Effects of C-Phycocyanin from the Cyanobacterium Spirulina sp. in Attenuating Oxidative Stress Induced by Peroxyl Radicals" Molecules 31, no. 1: 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010169

APA StyleGaxiola-Calvo, C. J., Fimbres-Olivarría, D., González-Vega, R. I., Cornejo-Ramírez, Y. I., Bernal-Mercado, A. T., Ruiz-Cruz, S., Ornelas-Paz, J. d. J., Robles-García, M. Á., Ramos-Enríquez, J. R., & Del-Toro-Sánchez, C. L. (2026). Antioxidant and Erythroprotective Effects of C-Phycocyanin from the Cyanobacterium Spirulina sp. in Attenuating Oxidative Stress Induced by Peroxyl Radicals. Molecules, 31(1), 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010169