Nickel Phosphine Complexes: Synthesis, Characterization, and Behavior in the Polymerization of 1,3-Butadiene

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

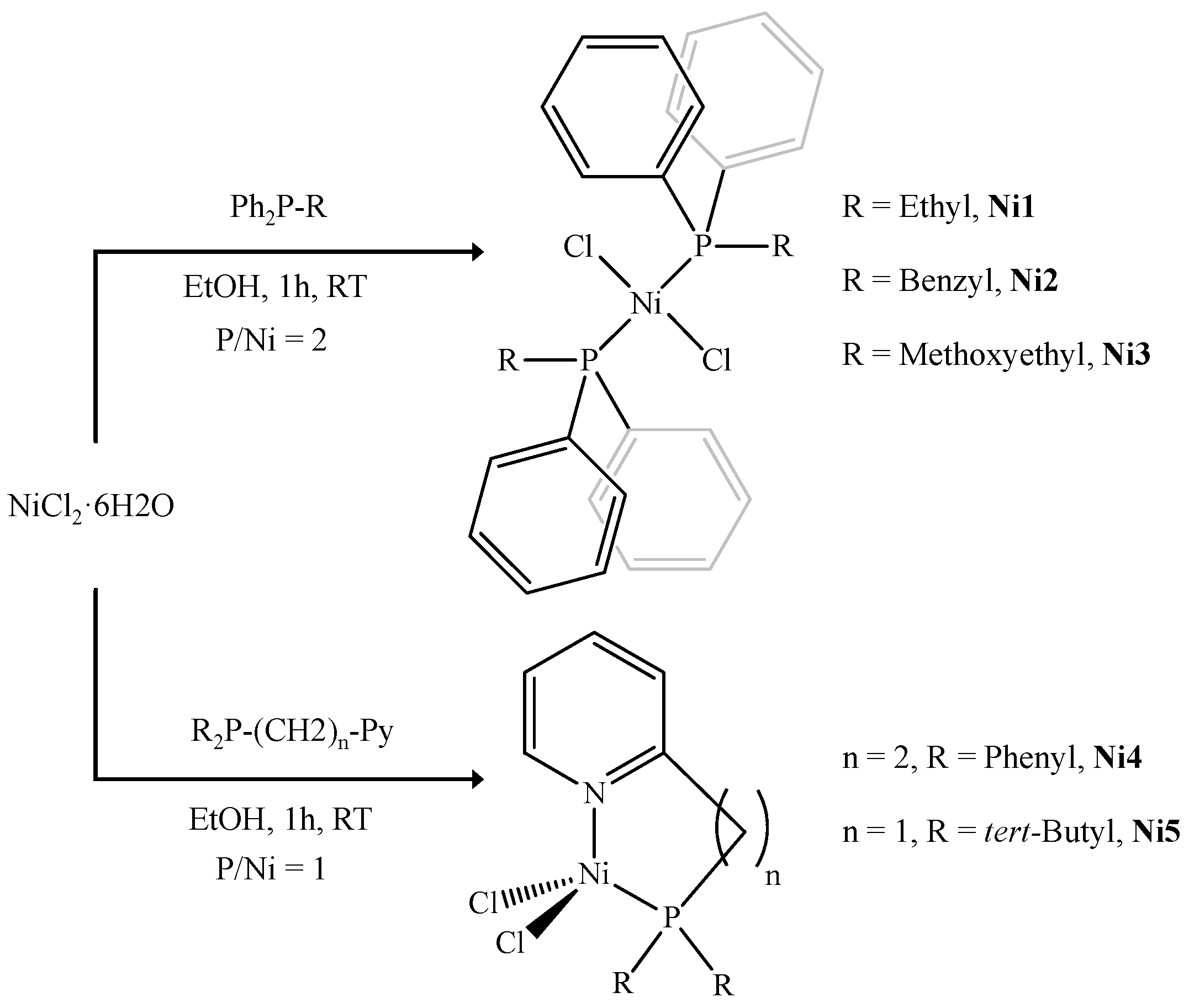

2.1. Synthesis of Nickel Complexes

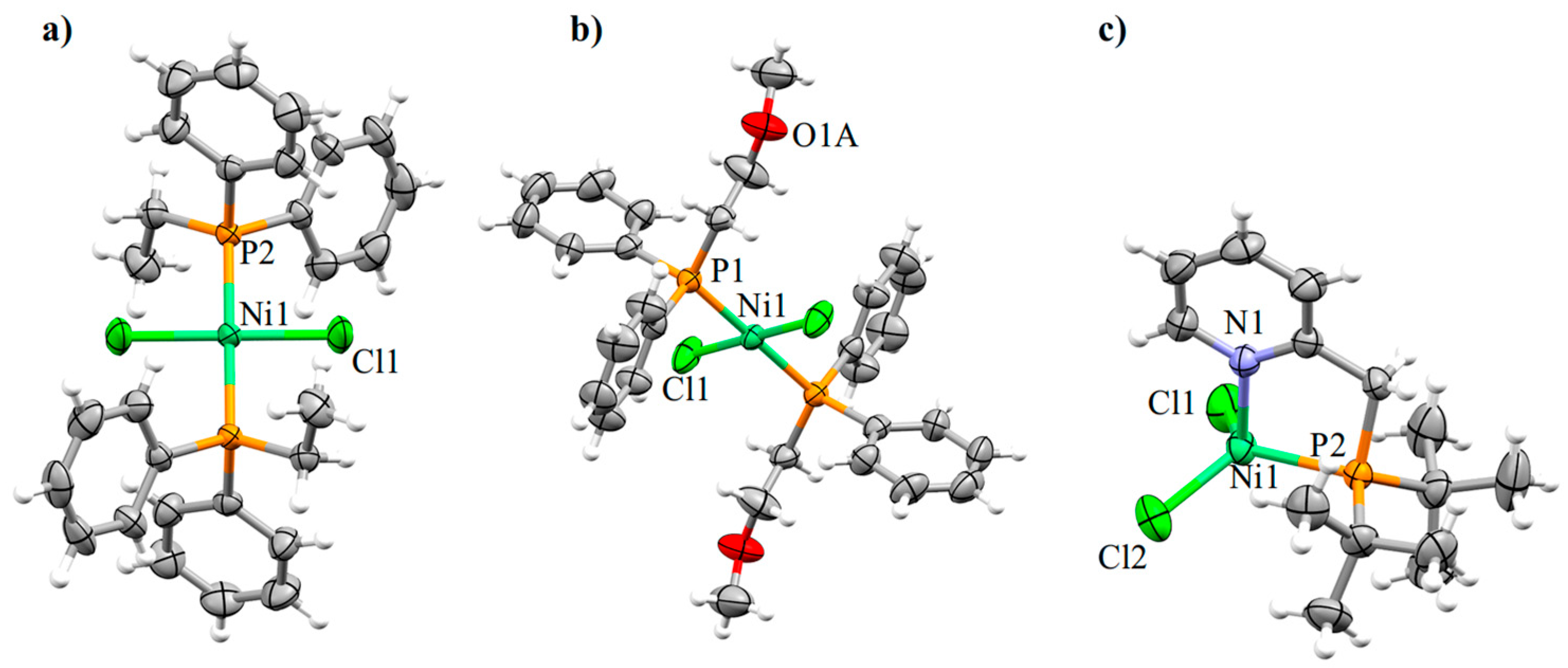

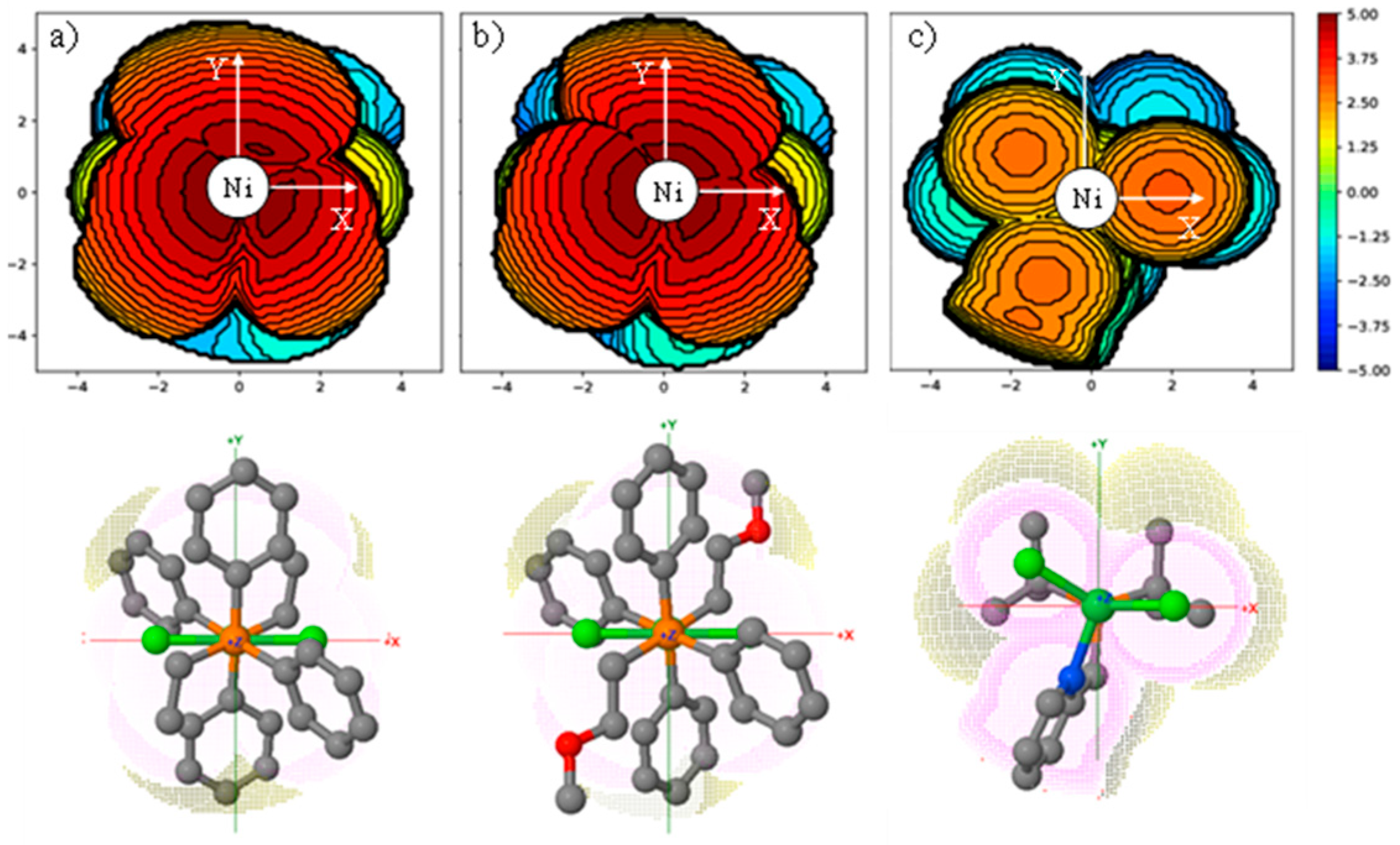

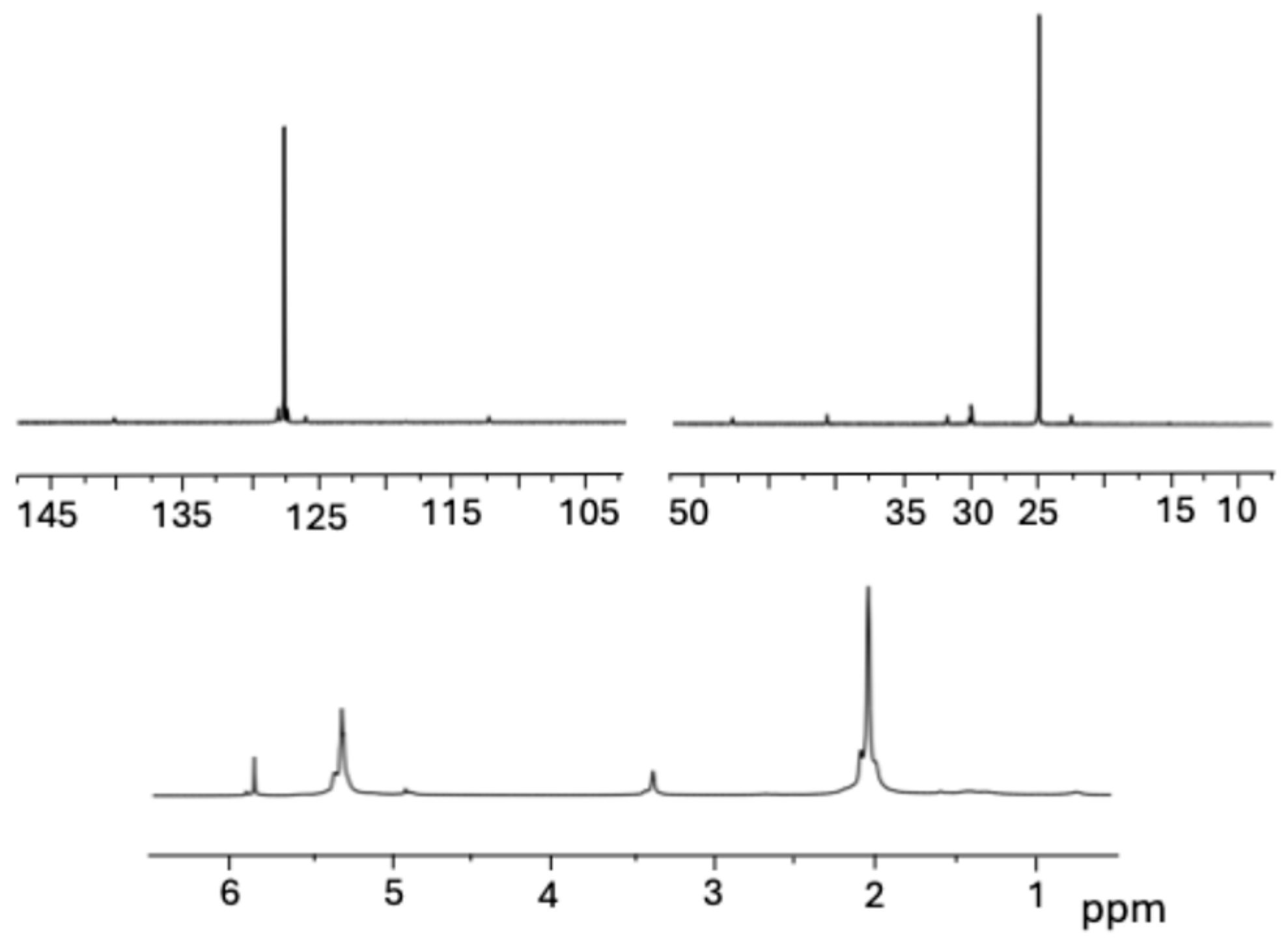

2.2. Crystallographic Characterization

2.3. Polymerization of 1,3-Butadiene

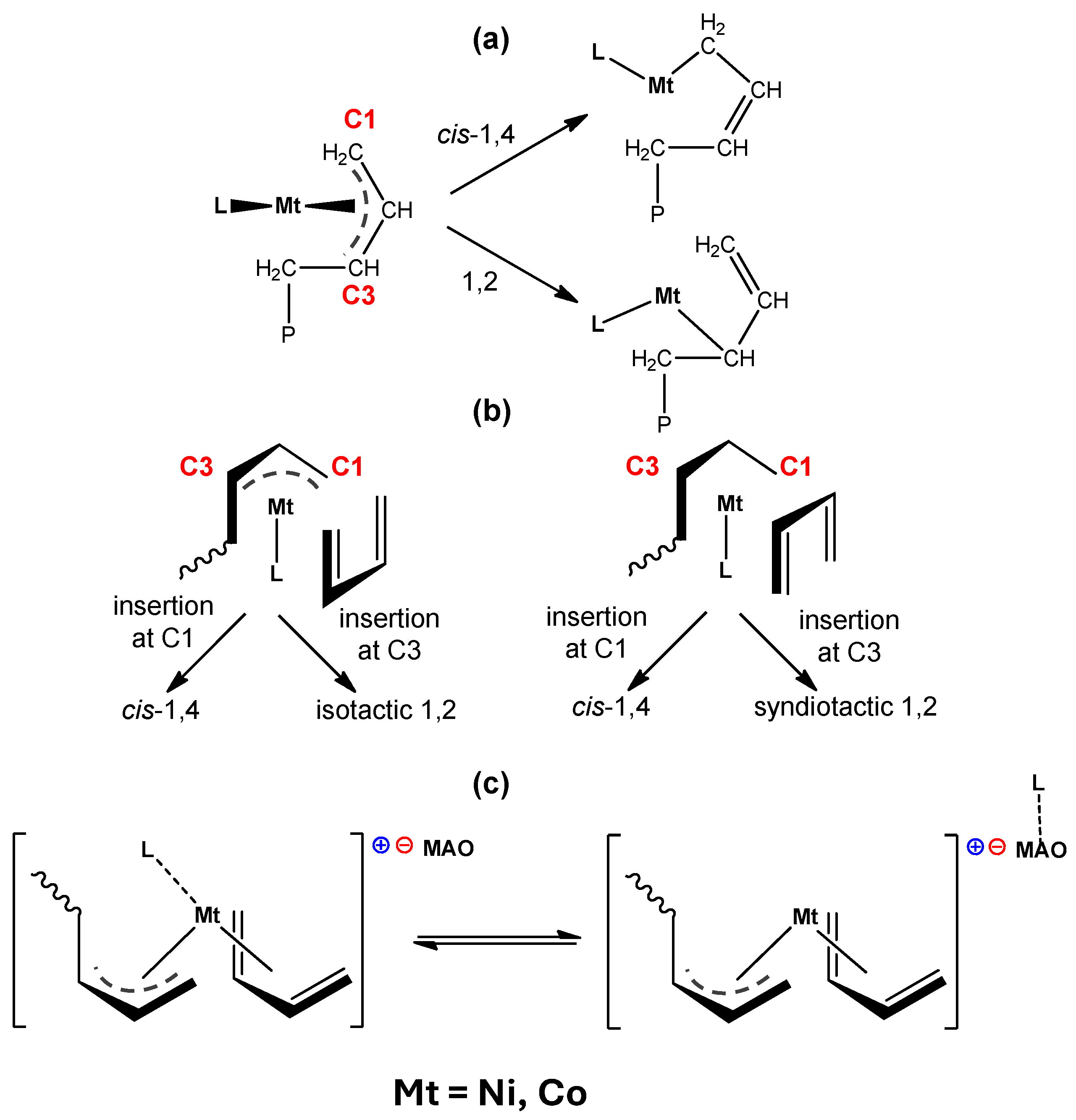

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. General Procedures and Materials

4.2. Synthesis of [NiCl2(ethyldiphenylphosphine)2] (Ni1)

4.3. Synthesis of [NiCl2(benzyldiphenylphosphine)2] (Ni2)

4.4. Synthesis of [NiCl2(2-methoxyethyldiphenylphosphine)2] (Ni3)

4.5. Synthesis of [NiCl2(k2-N,P-2-(2-(diphenylphosphino)ethyl)pyridine)] (Ni4)

4.6. Synthesis of [NiCl2(k2-N,P-2-((di-tert-butylphosphino)methyl)pyridine)] (Ni5)

4.7. SCXRD

4.8. Polymerization of 1,3-Butadiene

4.9. Polymer Characterization

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Porri, L.; Giarrusso, A. Conjugated Diene Polymerization. In Comprehensive Polymer Science; Eastmond, G., Edwith, A., Russo, S., Sigwalt, P., Eds.; Pergamon Press Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 1989; pp. 53–108. [Google Scholar]

- Racanelli, P.; Porri, L. Cis-1,4-polybutadiene by cobalt catalysts. Some features of the catalysts prepared from alkyl aluminium compounds containing Al-O-Al bonds. Eur. Polym. J. 1970, 5, 751–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimoto, T.; Komatskii, K.; Sakata, R.; Yamamoto, K.; Takeuchi, Y.; Onishi, A.; Ueda, K. Kinetic study of cis-1.4 polymerization of butadiene with nickel carboxylate/boron trifluoride etherate/triethylaluminum catalyst. Makromol. Chem. 1970, 139, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throckmorton, M.C.; Saltman, W.M. Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co. Germany Patent DE2257137A1, 24 October 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Ricci, G.; Italia, S.; Comitani, C.; Porri, L. Polymerization of conjugated dialkenes with transition metal catalysts. Influence of methylaluminoxane on catalyst activity and stereospecificity. Polym. Commun. 1991, 32, 514–517. [Google Scholar]

- Oliva, L.; Longo, P.; Grassi, A.; Ammendola, P.; Pellecchia, C. Polymerization of 1,3-alkadienes in the presence of Ni- and Ti-based catalytic systems containing methylalumoxane. Makromol. Chem. Rapid Commun. 1990, 11, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, G.; Zetta, L.; Porri, L.; Meille, S.V. Synthesis and characterization of isotactic cis-1,4 Poly(3-methyl-1,3-pentadiene). Macromol. Chem. Phys. 1995, 196, 2785–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, G.; Sommazzi, A.; Masi, F.; Ricci, M.; Boglia, A.; Leone, G. Well Defined Transition Metal Complexes with Phosphorus and Nitrogen Ligands for 1,3-Dienes Polymerization. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2010, 254, 661–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, G.; Leone, G. Recent progresses in the polymerization of butadiene over the last decade. Polyolefins J. 2014, 1, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, G.; Pampaloni, G.; Sommazzi, A.; Masi, F. Dienes polymerization: Where we are and what lies ahead. Macromolecules 2021, 54, 5879–5914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, M.; Shiono, T.; Soga, K. Polymerization of 1,3-butadiene with the catalyst system composed of a cobalt compound and methylaluminoxane. Polym. Int. 1992, 29, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, G.; Forni, A.; Boglia, A.; Motta, T.; Zannoni, G.; Canetti, M.; Bertini, F. Synthesis and X-Ray structure of CoCl2(PiPrPh2)2. A new highly active and stereospecific catalyst for 1,2 polymerization of conjugated dienes when used associated with MAO. Macromolecules 2005, 38, 1064–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, G.; Forni, A.; Boglia, A.; Sommazzi, A.; Masi, F. Synthesis, structure and butadiene polymerization behavior of CoCl2(PRxPh3−x)2 (R = methyl, ethyl, propyl, allyl, isopropyl, cyclohexyl; x = 1, 2). Influence of the phosphorous ligand on polymerization stereoselectivity. J. Organomet. Chem. 2005, 690, 1845–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, G.; Boccia, A.C.; Leone, G.; Forni, A. Novel Allyl Cobalt Phosphine Complexes: Synthesis, Characterization, and Behavior in the Polymerization of Allene and 1,3-Dienes. Catalysts 2017, 7, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, G.; Leone, G.; Pierro, I.; Zanchin, G.; Forni, A. Novel Cobalt Dichloride Complexes with Hindered Diphenylphosphine Ligands: Synthesis, Characterization, and Behavior in the Polymerization of Butadiene. Molecules 2019, 24, 2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricci, G.; Leone, G.; Zanchin, G.; Palucci, B.; Forni, A.; Sommazzi, A.; Masi, F.; Zacchini, S.; Guelfi, M.; Pampaloni, G. Some novel cobalt diphenylphosphine complexes: Synthesis, characterization, and behavior in the polymerization of 1,3-butadiene. Molecules 2021, 26, 4067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricci, G.; Leone, G.; Zanchin, G.; Sommazzi, A.; Masi, F.; Forni, A. Cobalt dichloride complexes with pyridyl-phosphine bidentate ligands: Synthesis, characterization, and behavior in the polymerization of 1,3-butadiene. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2023, 550, 121424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, A.; Sommazzi, F.; Masi, A. Forni Polymerization of 1,3-Butadiene with Catalysts Based on Cobalt Dichloride Complexes with Aminophosphines: Switching the Regioselectivity by Varying the MAO/Co Molar Ratio. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 2024, 42, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venanzi, L.M. Tetrahedral nickel(II) complexes and the factor determining their formation. Part I. Bistriphenylphosphine nickel(II) compounds. J. Chem. Soc. 1958, 719–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garton, G.; Henn, D.E.; Powell, H.M.; Venanzi, L.M. Tetrahedral nickel(II) complexes and the factor determining their formation. Part V. The tetrahedral co-ordination of nickel in dichlorobis(triphenylphosphine)nickel. J. Chem. Soc. 1963, 3625–3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hecke, G.R.; Horrocks, W.D., Jr. Approximate Force Constants for Tetrahedral Metal Carbonyls and Nitrosyls. Inorg. Chem. 1966, 5, 1960–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, K.W. Nickel Complexes with Organic and Phosphorus Ligands: An integrated set of inorganic experiments. J. Chem. Educ. 1974, 51, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, L.; Stevens, E.D. Structure of dichlorobis(triphenylphosphine)nickel(II). Acta Crystallogr. C 1989, 45, 400–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standley, E.A.; Smith, S.J.; Müller, P.; Jamison, T.F. A Broadly Applicable Strategy for Entry into Homogeneous Nickel(0) Catalysts from Air-Stable Nickel(II) Complexes. Organometallics 2014, 33, 2012–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flapper, J.; Kooijman, H.; Lutz, M.; Spek, A.L.; van Leeuwen, P.W.N.M.; Elsevier, C.J.; Kamer, P.C.J. Nickel and Palladium Complexes of Pyridine−Phosphine Ligands as Ethene Oligomerization Catalysts. Organometallics 2009, 28, 1180–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kermagoret, A.; Braunstein, P. Mono- and Dinuclear Nickel Complexes with Phosphino-, Phosphinito-, and Phosphonitopyridine Ligands: Synthesis, Structures, and Catalytic Oligomerization of Ethylene. Organometallics 2008, 27, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.F. The determination of the paramagnetic susceptibility of substances in solution by nuclear magnetic resonance. J. Chem. Soc. 1959, 2003–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, G.A.; Berry, J.F. Diamagnetic Corrections and Pascal’s Constants. J. Chem. Educ. 2008, 85, 532–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corain, B.; Longato, B.; Angeletti, R.; Valle, G. trans-[Dichlorobis(triphenylphosphine)nickel(II)]·(C2H4Cl2)2: A clathrate of the allogon of venanzi’s tetrahedral complex. In. Chim. Acta 1985, 104, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Powell, D.R.; Houser, R.P. Structural variation in copper(I) complexes with pyridylmethylamide ligands: Structural analysis with a new four-coordinate geometry index, τ4. Dalton Trans. 2007, 9, 955–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, L.; Niewa, R. Polynator: A tool to identify and quantitatively evaluate polyhedra and other shapes in crystal structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2003, 56, 1855–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falivene, L.; Cao, Z.; Petta, A.; Serra, L.; Poater, A.; Oliva, R.; Scarano, V.; Cavallo, L. Towards the online computer-aided design of catalytic pockets. Nat. Chem. 2019, 11, 872–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poater, A.; Ragone, F.; Giudice, S.; Costabile, C.; Dorta, R.; Nolan, S.P.; Cavallo, L. Thermodynamics of N-heterocyclic carbene dimerization: The balance of sterics and electronics. Organometallics 2008, 27, 2679–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poater, A.; Ragone, F.; Mariz, R.; Dorta, R.; Cavallo, L. Comparing the Enantioselective Power of Steric and Electrostatic Effects in Transition-Metal-Catalyzed Asymmetric Synthesis. Chem. Eur. J. 2010, 16, 14348–14353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porri, L.; Giarrusso, A.; Ricci, G. Recent views on the mechanism of diolefin polymeization with transition metal initiator systems. Prog. Polym. Sci. 1991, 16, 405–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snook, J.H.; Foxman, B.H. CCDC 2171959: Experimental Crystal Structure Determination; CCDC: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruker. APEX4 V2021.10-0, Bruker AXS Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 2021.

- Bruker. SAINT v8.30A, Bruker AXS Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 2012.

- Bruker. XPREP V2014/2, Bruker AXS Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 2014.

- Bruker. SADABS V2016/2, Bruker AXS Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 2016.

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXL-2019/1, Bruker AXS Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 2019.

- Mochel, V.D. Carbon-13 NMR of polybutadiene. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 1972, 10, 1009–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgert, K.F.; Quack, G.; Stutzel, B. Zur struktur des polybutadiens, 2. Das 13C-NMR-Spektrum des 1,2-polybutadiens. Makromol. Chem. 1974, 175, 1955–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Entry | Ni_Complex | MAO/Ni (Molar Ratio) | Time (h) | Yield (g) | N b (h−1) | cis-1,4 c (%) | Mw d (g/mol) | Mw/Mn d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry 1 | Ni1 | 100 | 3 | 1.4 | 864 | 92.3 | 41,000 | 2.5 |

| entry 2 | Ni1 | 1000 | 3 | 1.4 | 864 | 94.2 | 44,000 | 1.5 |

| entry 3 | Ni2 | 100 | 3 | 1.4 | 864 | 92.0 | 32,000 | 3.0 |

| entry 4 | Ni2 | 1000 | 3 | 1.4 | 864 | 94.2 | 56,000 | 2.1 |

| entry 5 | Ni3 | 100 | 4 | 1.19 | 550 | 95.3 | 46,000 | 3.1 |

| entry 6 | Ni3 | 1000 | 4 | 1.4 | 648 | 97.1 | 48,500 | 2.8 |

| entry 7 | Ni4 | 100 | 3 | 1.12 | 691 | 96.0 | 30,000 | 2.4 |

| entry 8 | Ni4 | 1000 | 3 | 1.30 | 802 | 96.4 | 35,000 | 2.2 |

| entry 9 | Ni5 | 100 | 4 | 0.77 | 356 | 93.0 | 44,500 | 2.0 |

| entry 10 | Ni5 | 1000 | 4 | 0.90 | 417 | 93.7 | 46,500 | 1.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guelfi, M.; Bresciani, G.; Pampaloni, G.; Sommazzi, A.; Masi, F.; Palucci, B.; Losio, S.; Ricci, G. Nickel Phosphine Complexes: Synthesis, Characterization, and Behavior in the Polymerization of 1,3-Butadiene. Molecules 2025, 30, 4655. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234655

Guelfi M, Bresciani G, Pampaloni G, Sommazzi A, Masi F, Palucci B, Losio S, Ricci G. Nickel Phosphine Complexes: Synthesis, Characterization, and Behavior in the Polymerization of 1,3-Butadiene. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4655. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234655

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuelfi, Massimo, Giulio Bresciani, Guido Pampaloni, Anna Sommazzi, Francesco Masi, Benedetta Palucci, Simona Losio, and Giovanni Ricci. 2025. "Nickel Phosphine Complexes: Synthesis, Characterization, and Behavior in the Polymerization of 1,3-Butadiene" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4655. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234655

APA StyleGuelfi, M., Bresciani, G., Pampaloni, G., Sommazzi, A., Masi, F., Palucci, B., Losio, S., & Ricci, G. (2025). Nickel Phosphine Complexes: Synthesis, Characterization, and Behavior in the Polymerization of 1,3-Butadiene. Molecules, 30(23), 4655. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234655