Chromatographic and Molecular Insights into Fatty Acid Profiles of Thermophilic Lactobacillus Strains: Influence of Tween 80TM Supplementation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Extraction of Fatty Acids from Bacterial Biomass

4.3. Conditions for Separating and Detecting Fatty Acid Methyl Esters Using GC-MS

4.4. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Montanari, C.; Sado Kamdem, S.L.; Serrazanetti, D.I.; Etoa, F.-X.; Guerzoni, M.E. Synthesis of Cyclopropane Fatty Acids in Lactobacillus Helveticus and Lactobacillus Sanfranciscensis and Their Cellular Fatty Acids Changes Following Short Term Acid and Cold Stresses. Food Microbiol. 2010, 27, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partanen, L.; Marttinen, N.; Alatossava, T. Fats and Fatty Acids as Growth Factors for Lactobacillus Delbrueckii. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2001, 24, 500–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaręba, D.; Ziarno, M. Tween 80TM-Induced Changes in Fatty Acid Profile of Selected Mesophilic Lactobacilli. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2024, 71, 13014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnsson, T.; Nikkila, P.; Toivonen, L.; Rosenqvist, H.; Laakso, S. Cellular Fatty Acid Profiles of Lactobacillus and Lactococcus Strains in Relation to the Oleic Acid Content of the Cultivation Medium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 4497–4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beal, C.; Fonseca, F.; Corrieu, G. Resistance to Freezing and Frozen Storage of Streptococcus Thermophilus Is Related to Membrane Fatty Acid Composition. J. Dairy Sci. 2001, 84, 2347–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, Y.H.; Sugai, A.; Uda, I.; Itoh, T. The Evolution of Lipids. Adv. Space Res. 2001, 28, 719–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kankaanpää, P.; Yang, B.; Kallio, H.; Isolauri, E.; Salminen, S. Effects of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in Growth Medium on Lipid Composition and on Physicochemical Surface Properties of Lactobacilli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Murga, M.L.; Cabrera, G.; Martos, G.; Font de Valdez, G.; Seldes, A.M. Analysis by Mass Spectrometry of the Polar Lipids from the Cellular Membrane of Thermophilic Lactic Acid Bacteria. Molecules 2000, 5, 518–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitermayer, D.; Kafka, T.A.; Lenz, C.A.; Vogel, R.F. Interrelation between Tween and the Membrane Properties and High Pressure Tolerance of Lactobacillus Plantarum. BMC Microbiol. 2018, 18, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, B.M.; Stanton, C.; Fitzgerald, G.F.; Ross, R.P. Growth of Probiotic Lactobacilli in the Presence of Oleic Acid Enhances Subsequent Survival in Gastric Juice. Microbiology 2007, 153, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.-L.R.W.; Petersen, M.A.; Risbo, J.; Hümmer, M.; Clausen, A. Implications of Modifying Membrane Fatty Acid Composition on Membrane Oxidation, Integrity, and Storage Viability of Freeze-Dried Probiotic, Lactobacillus Acidophilus La-5. Biotechnol. Prog. 2015, 31, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liong, M.T.; Shah, N.P. Acid and Bile Tolerance and Cholesterol Removal Ability of Lactobacilli Strains. J. Dairy Sci. 2005, 88, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macouzet, M.; Robert, N.; Lee, B.H. Genetic and Functional Aspects of Linoleate Isomerase in Lactobacillus Acidophilus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 87, 1737–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogawa, J.; Kishino, S.; Ando, A.; Sugimoto, S.; Mihara, K.; Shimizu, S. Production of Conjugated Fatty Acids by Lactic Acid Bacteria. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2005, 100, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Alcalá, L.M.; Braga, T.; Xavier Malcata, F.; Gomes, A.; Fontecha, J. Quantitative and Qualitative Determination of CLA Produced by Bifidobacterium and Lactic Acid Bacteria by Combining Spectrophotometric and Ag+-HPLC Techniques. Food Chem. 2011, 125, 1373–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Lin, C.W.; Wang, Y.J. Linoleic Acid Isomerase Activity in Enzyme Extracts from Lactobacillus Acidophilus and Propionibacterium Freudenreichii Ssp. Shermanii. J. Food Sci. 2002, 67, 1502–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Lin, C.-W.; Wang, Y.-J. Production of Conjugated Linoleic Acid by Enzyme Extract of Lactobacillus Acidophilus CCRC 14079. Food Chem. 2003, 83, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Hung, T.-H.; Cheng, T.-S.J. Conjugated Linoleic Acid Production by Immobilized Cells of Lactobacillus Delbrueckii Ssp. Bulgaricus and Lactobacillus Acidophilus. Food Chem. 2005, 92, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y. Conjugated Linoleic Acid Production by Cells and Enzyme Extract of Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus with Additions of Different Fatty Acids. Food Chem. 2006, 94, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, A.F.; Korkeala, H.; Mononen, I. Gas chromatography analysis of cellular fatty acids and neutral monosaccharides in the identification of lactobacilli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1987, 53, 2883–2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanauchi, M. Hydroxylation of Fatty Acids by Lactic Acid Bacteria. In Lactic Acid Bacteria: Methods and Protocols; Kanauchi, M., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 107–114. ISBN 978-1-0716-4096-8. [Google Scholar]

- Guerzoni, M.E.; Lanciotti, R.; Cocconcelli, P.S. Alteration in Cellular Fatty Acid Composition as a Response to Salt, Acid, Oxidative and Thermal Stresses in Lactobacillus Helveticus. Microbiology 2001, 147, 2255–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buyer, J.S. Rapid Sample Processing and Fast Gas Chromatography for Identification of Bacteria by Fatty Acid Analysis. J. Microbiol. Methods 2002, 51, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haack, S.K.; Garchow, H.; Odelson, D.A.; Forney, L.J.; Klug, M.J. Accuracy, Reproducibility, and Interpretation of Fatty Acid Methyl Ester Profiles of Model Bacterial Communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1994, 60, 2483–2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basconcillo, L.S.; McCarry, B.E. Comparison of Three GC/MS Methodologies for the Analysis of Fatty Acids in Sinorhizobium Meliloti: Development of a Micro-Scale, One-Vial Method. J. Chromatogr. B 2008, 871, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionisi, F.; Golay, P.-A.; Elli, M.; Fay, L.B. Stability of Cyclopropane and Conjugated Linoleic Acids during Fatty Acid Quantification in Lactic Acid Bacteria. Lipids 1999, 34, 1107–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutter, M.E.; Dick, R.P. Comparison of Fatty Acid Methyl Ester (FAME) Methods for Characterizing Microbial Communities. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2000, 64, 1659–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Špitsmeister, M.; Adamberg, K.; Vilu, R. UPLC/MS Based Method for Quantitative Determination of Fatty Acid Composition in Gram-Negative and Gram-Positive Bacteria. J. Microbiol. Methods 2010, 82, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, K.; Jarvis, Å.; Smårs, S.; Sundh, I. Comparison of Signature Lipid Methods to Determine Microbial Community Structure in Compost. J. Microbiol. Methods 2003, 55, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mjøs, S.A. Identification of Fatty Acids in Gas Chromatography by Application of Different Temperature and Pressure Programs on a Single Capillary Column. J. Chromatogr. A 2003, 1015, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, W.W.; Dobson, G.; Adlof, R.O. A Practical Guide to the Isolation, Analysis and Identification of Conjugated Linoleic Acid. Lipids 2007, 42, 1073–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brondz, I. Development of Fatty Acid Analysis by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography, Gas Chromatography, and Related Techniques. Anal. Chim. Acta 2002, 465, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fatty Acid (Acid Name)/Strain Symbol | Class | Precursor of cyc/CLA | ATCC 4356 | NCFM | La-5 | La-14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C10:0 (caproic/decanoic) | saturated | – | 0.23 a ± 0.01 | 0.44 b ± 0.10 | 0.56 b ± 0.24 | 0.33 a,b ± 0.13 |

| C12:0 (lauric/dodecanoic) | saturated | – | 3.38 a ± 0.34 | 4.58 b ± 0.55 | 3.36 a ± 2.52 | 4.75 b ± 0.54 |

| C14:0 (myristic/tetradecanoic) | saturated | – | 3.69 a ± 0.19 | 3.44 a ± 0.30 | 2.45 b ± 1.03 | 3.72 a ± 0.31 |

| 15:0,iso (iso-13-methyltetradecanoic) | saturated (branched) | – | 0.10 a ± 0.02 | 0.08 a ± 0.02 | 0.08 a ± 0.01 | 0.10 a ± 0.02 |

| 15:0,anteiso (anteiso-12-methyltetradecanoic) | saturated (branched) | – | 0.21 a ± 0.02 | 0.25 a,b ± 0.03 | 0.28 b ± 0.03 | 0.28 b ± 0.04 |

| C15:0 (pentadecanoic) C16:0 (palmitic/hexadecanoic) | saturated | – | 0.11 a ± 0.02 | 0.17 b ± 0.02 | 0.14 b ± 0.04 | 0.20 b ± 0.05 |

| saturated | – | 5.55 a ± 0.35 | 11.88 b ± 0.72 | 10.77 b ± 1.53 | 12.66 b ± 1.13 | |

| C16:1,trans-9 (palmitelaidic/trans-9-hexadecenoic) C16:1,cis-9 (palmitoleic/cis-9-hexadecenoic) | unsaturated (trans) | – | 0.11 a ± 0.01 | 0.15 a,b ± 0.02 | 0.18 b ± 0.02 | 0.17 b ± 0.03 |

| unsaturated (cis) | – | 1.54 a ± 0.09 | 1.73 a,b ± 0.18 | 2.29 b ± 0.54 | 1.87 a,b ± 0.20 | |

| C12:0,2OH (2-hydroxydodecanoic) | saturated hydroxyacid | – | 0.10 a ± 0.02 | 0.17 a ± 0.02 | 0.18 a ± 0.06 | 0.16 a ± 0.03 |

| cycC17:0,cis-9,10 (cis-9,10-methylenehexadecanoic) | cyclic | – | 0.00 a ± 0.00 | 0.00 a ± 0.00 | 0.00 a ± 0.00 | 0.00 a ± 0.00 |

| C18:0 (stearic/octadecanoic) | saturated | – | 0.98 a ± 0.11 | 1.33 b ± 0.17 | 1.25 b ± 0.16 | 1.34 b ± 0.30 |

| C18:1 (octadecenoic) | unsaturated | – | 0.44 b ± 0.08 | 0.33 a ± 0.07 | 0.42 b ± 0.02 | 0.36 a ± 0.05 |

| C18:1,trans-6 (petroselaidic/trans-6-octadecenoic) | unsaturated (trans) | – | 0.00 a ± 0.00 | 0.00 a ± 0.00 | 0.00 a ± 0.00 | 0.00 a ± 0.00 |

| C18:1,trans-9 (elaidic/trans-9-octa-decenoic) | unsaturated (trans) | – | 0.00 a ± 0.00 | 0.00 a ± 0.00 | 0.00 a ± 0.00 | 0.00 a ± 0.00 |

| C18:1,trans-11 (trans-vaccenic/trans-11-octadecenoic) | unsaturated (trans) | – | 0.46 a ± 0.04 | 0.78 b ± 0.15 | 0.82 b ± 0.06 | 0.69 b ± 0.31 |

| C18:1,cis-6 (petroselinic/cis-6-octadecenoic) | unsaturated (cis) | – | 0.70 b ± 0.06 | 0.14 a ± 0.05 | 0.15 a ± 0.03 | 0.10 a ± 0.02 |

| C18:1,cis-9 (oleic/cis-9-octadecenoic) | unsaturated (cis) | * (CLA and cyclic acid precursor) | 41.81 a ± 0.79 | 40.52 a ± 3.11 | 42.62 a ± 1.11 | 40.70 a ± 2.11 |

| C18:1,cis-11 (cis-vaccenic/cis-11-octadecenoic) | unsaturated (cis) | – | 1.65 a ± 0.02 | 1.71 a ± 0.06 | 1.99 b ± 0.28 | 1.72 a ± 0.02 |

| C18:2,trans-9,trans-12 (linoelaidic/trans-9, trans-12-octadecadienoic) | unsaturated (trans) | – | 0.00 a ± 0.00 | 0.00 a ± 0.00 | 0.00 a ± 0.00 | 0.00 a ± 0.00 |

| C18:2,cis-9,cis-12 (linoleic/cis-9,cis 12-octadecadienoic) | unsaturated (cis) | * (CLA precursor) | 0.18 a ± 0.02 | 0.20 a ± 0.03 | 0.19 a ± 0.07 | 0.23 a ± 0.07 |

| cycC19:0,cis-9,10 (dihydrosterculic/cis-9,10-methyleneoctadecanoic) | cyclic | – | 33.89 a ± 0.84 | 25.12 b ± 3.01 | 25.43 b ± 5.45 | 23.63 b ± 2.55 |

| cycC19:0,cis-10,11 (lactobacillic/cis-11,12-methyleneoctadecanoic) | cyclic | – | 0.38 a ± 0.26 | 0.48 a ± 0.05 | 0.59 a ± 0.10 | 0.44 a ± 0.06 |

| 18:2,cis-9,trans-11 (conjugated octadecadienoic) | conjugated (CLA) | – | 1.70 a ± 0.05 | 1.89 a ± 0.22 | 1.92 b ± 0.10 | 1.82 a ± 0.24 |

| C18:2, CLA_1 (conjugated octadecadienoic) | conjugated (CLA) | – | 0.12 a ± 0.02 | 0.21 a ± 0.05 | 0.17 a ± 0.03 | 0.26 b ± 0.06 |

| 18:2,trans-10,cis-12 (conjugated octadecadienoic) | conjugated (CLA) | – | 1.42 a ± 0.04 | 2.04 a,b ± 0.22 | 2.09 b ± 0.12 | 1.93 a,b ± 0.25 |

| C18:2, CLA_2 (conjugated octadecadienoic) | conjugated (CLA) | – | 0.16 a ± 0.02 | 0.24 b ± 0.04 | 0.21 b ± 0.04 | 0.24 b ± 0.02 |

| C18:2, CLA_3 (conjugated octadecadienoic) | conjugated (CLA) | – | 0.13 a ± 0.01 | 0.24 b ± 0.02 | 0.21 b ± 0.03 | 0.24 b ± 0.02 |

| C18:2, CLA_4 (conjugated octadecadienoic) | conjugated (CLA) | – | 0.98 a ± 0.02 | 1.89 a,b ± 0.23 | 1.64 a,b ± 0.31 | 2.05 b ± 0.18 |

| ratio cycC19:0,cis-9,10/cycC19:0,cis-10,11 | 89.18 | 52.33 | 43.10 | 53.70 | ||

| ratio C18:1,cis-9/C18:1,cis-11 | 25.34 | 23.70 | 21.42 | 23.66 | ||

| ∑ unsaturated acids | 51.40 | 52.07 | 54.90 | 52.38 | ||

| ∑ saturated acids | 14.25 | 22.17 | 18.89 | 23.38 | ||

| ratio unsaturated/saturated | 3.61 | 2.35 | 2.91 | 2.24 | ||

| ∑ conjugated C18:2,cis-9,cis-12 acids | 4.51 | 6.51 | 6.24 | 6.54 | ||

| cis/trans | 47.37 | 44.10 | 46.85 | 44.53 | ||

| mono-/polyunsaturated | 5.89 | 4.83 | 6.50 | 5.83 | ||

| CLA/other conjugated fatty acids | 6.87 | 7.44 | 7.72 | 8.97 |

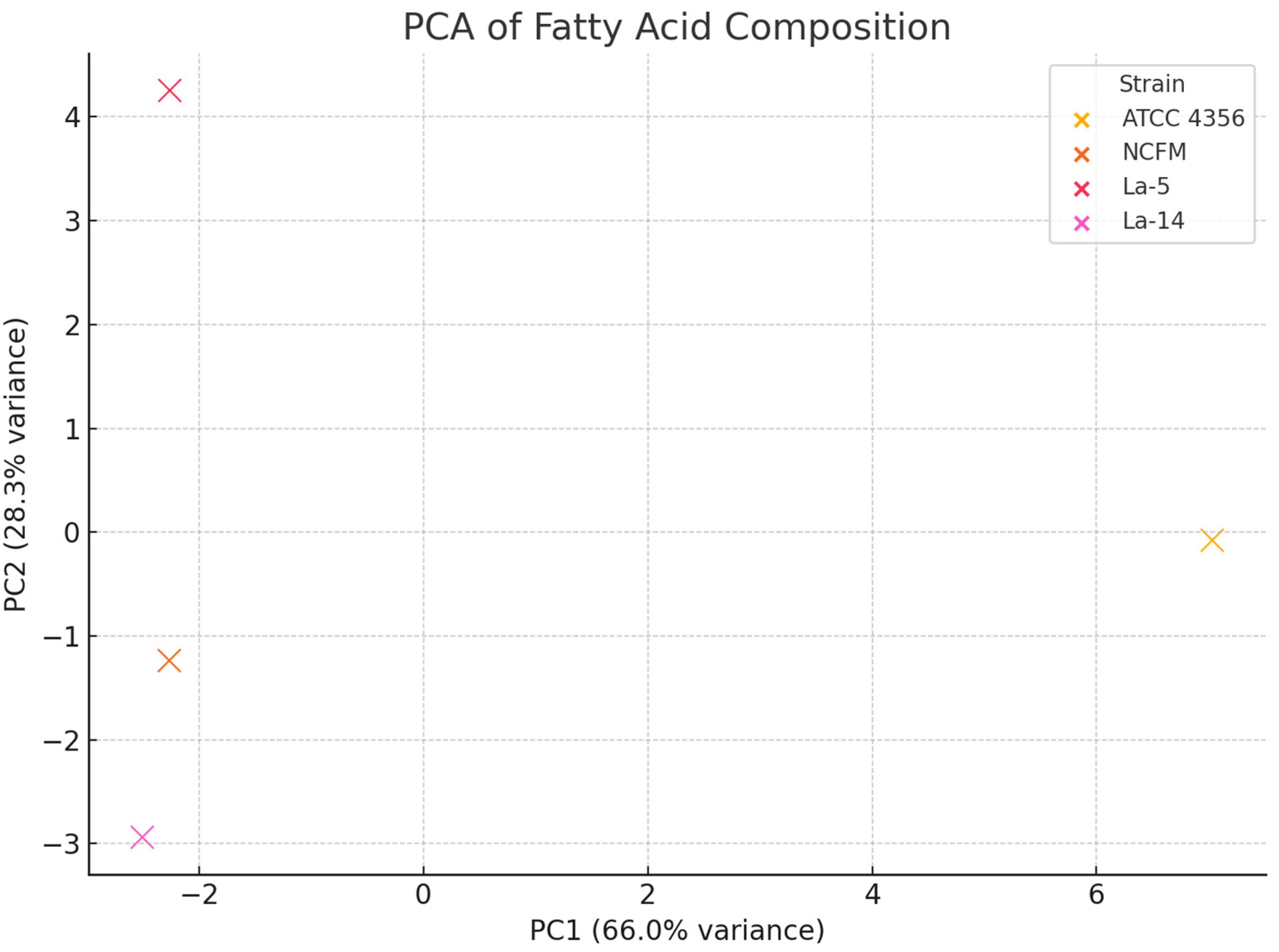

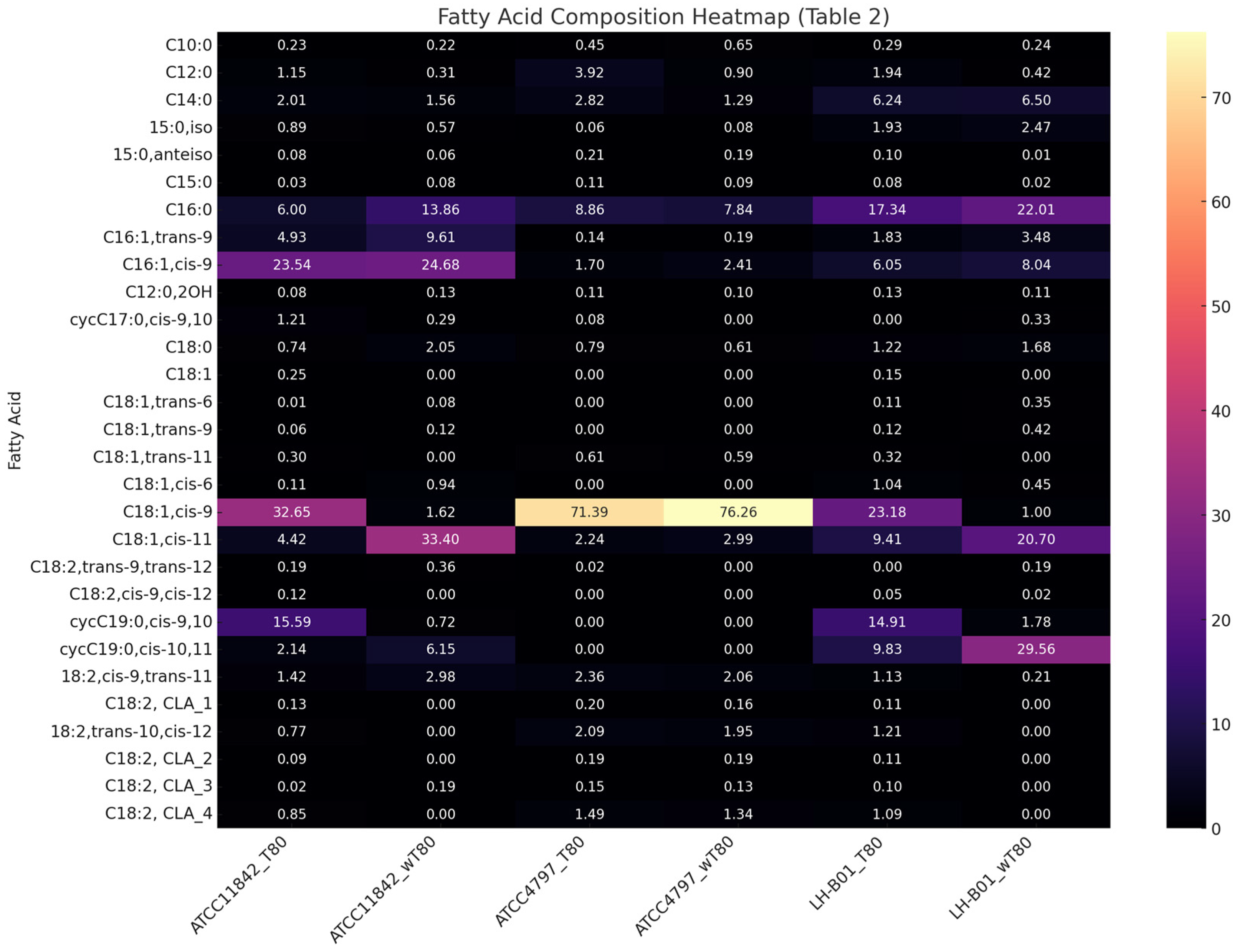

| Strain Symbol | L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus ATCC 11842 | L. delbrueckii subsp. lactis ATCC 4797 | L. helveticus LH-B01 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty Acid/Medium | T80 | wT80 | T80 | wT80 | T80 | wT80 |

| C10:0 (caproic/decanoic) | 0.23 a ± 0.07 | 0.22 a ± 0.02 | 0.45 a,b ± 0.21 | 0.65 b ± 0.20 | 0.29 a ± 0.05 | 0.24 a ± 0.15 |

| C12:0 (lauric/dodecanoic) | 1.15 a ± 0.58 | 0.31 b ± 0.06 | 3.92 c ± 1.51 | 0.90 b ± 0.13 | 1.94 a,b ± 0.20 | 0.42 b ± 0.17 |

| C14:0 (myristic/tetradecanoic) | 2.01 a ± 0.24 | 1.56 a ± 0.43 | 2.82 a ± 0.65 | 1.29 b ± 0.13 | 6.24 c ± 1.93 | 6.50 c ± 2.60 |

| 15:0,iso (iso-13-methyltetradecanoic) | 0.89 a ± 0.15 | 0.57 b ± 0.07 | 0.06 c ± 0.00 | 0.08 c ± 0.03 | 1.93 d ± 0.55 | 2.47 d ± 0.71 |

| 15:0,anteiso (anteiso-12-methyltetradecanoic) | 0.08 a ± 0.07 | 0.06 a ± 0.03 | 0.21 b ± 0.02 | 0.19 b ± 0.01 | 0.10 a ± 0.01 | 0.01 c ± 0.01 |

| C15:0 (pentadecanoic) C16:0 (palmitic/hexadecanoic) | 0.03 a ± 0.05 | 0.08 a ± 0.05 | 0.11 b ± 0.01 | 0.09 b ± 0.02 | 0.08 a,b ± 0.04 | 0.02 a ± 0.03 |

| 6.00 a ± 0.87 | 13.86 b ± 0.67 | 8.86 c ± 0.49 | 7.84 c ± 0.48 | 17.34 d ± 1.24 | 22.01 e ± 2.78 | |

| C16:1,trans-9 (palmitelaidic/trans-9-hexadecenoic) C16:1,cis-9 (palmitoleic/cis-9-hexadecenoic) | 4.93 a ± 1.26 | 9.61 b ± 0.30 | 0.14 c ± 0.03 | 0.19 c ± 0.04 | 1.83 d ± 0.84 | 3.48 d ± 1.05 |

| 23.54 a ± 4.80 | 24.68 a ± 1.35 | 1.70 b ± 0.44 | 2.41 b ± 0.02 | 6.05 c ± 1.22 | 8.04 c ± 2.28 | |

| C12:0,2OH (2-hydroxydodecanoic) | 0.08 a ± 0.07 | 0.13 a ± 0.04 | 0.11 a ± 0.03 | 0.10 a ± 0.02 | 0.13 a ± 0.01 | 0.11 a ± 0.04 |

| cycC17:0,cis-9,10 (cis-9,10-methylenehexadecanoic) | 1.21 a ± 0.41 | 0.29 b ± 0.05 | 0.08 b ± 0.13 | 0.00 b ± 0.00 | 0.00 b ± 0.00 | 0.33 b ± 0.11 |

| C18:0 (stearic/octadecanoic) | 0.74 a ± 0.07 | 2.05 b ± 0.04 | 0.79 a ± 0.10 | 0.61 a ± 0.06 | 1.22 c ± 0.22 | 1.68 c ± 0.87 |

| C18:1 (octadecenoic) | 0.25 a ± 0.06 | 0.00 b ± 0.00 | 0.00 b ± 0.00 | 0.00 b ± 0.00 | 0.15 a ± 0.02 | 0.00 b ± 0.00 |

| C18:1,trans-6 (petroselaidic/trans-6-octadecenoic) | 0.01 a ± 0.02 | 0.08 a ± 0.02 | 0.00 a ± 0.00 | 0.00 a ± 0.00 | 0.11 b ± 0.04 | 0.35 c ± 0.07 |

| C18:1,trans-9 (elaidic/trans-9-octa-decenoic) | 0.06 a ± 0.03 | 0.12 a ± 0.02 | 0.00 b ± 0.00 | 0.00 b ± 0.00 | 0.12 a ± 0.07 | 0.42 c ± 0.06 |

| C18:1,trans-11 (trans-vaccenic/trans-11-octadecenoic) | 0.30 a ± 0.07 | 0.00 b ± 0.00 | 0.61 c ± 0.19 | 0.59 c ± 0.26 | 0.32 a ± 0.07 | 0.00 b ± 0.00 |

| C18:1,cis-6 (petroselinic/cis-6-octadecenoic) | 0.11 a ± 0.06 | 0.94 b ± 0.09 | 0.00 c ± 0.00 | 0.00 c ± 0.00 | 1.04 b ± 0.30 | 0.45 a,b ± 0.34 |

| C18:1,cis-9 (oleic/cis-9-octadecenoic) | 32.65 a ± 4.99 | 1.62 b ± 0.70 | 71.39 c ± 2.67 | 76.26 c ± 1.33 | 23.18 d ± 2.22 | 1.00 b ± 0.21 |

| C18:1,cis-11 (cis-vaccenic/cis-11-octadecenoic) | 4.42 a ± 0.68 | 33.40 b ± 2.22 | 2.24 c ± 0.31 | 2.99 c ± 0.13 | 9.41 d ± 1.84 | 20.70 e ± 7.19 |

| C18:2,trans-9,trans-12 (linoelaidic/trans-9, trans-12-octadecadienoic) | 0.19 a ± 0.03 | 0.36 a ± 0.06 | 0.02 b ± 0.04 | 0.00 b ± 0.00 | 0.00 b ± 0.00 | 0.19 a ± 0.10 |

| C18:2,cis-9,cis-12 (linoleic/cis-9,cis 12-octadecadienoic) | 0.12 a ± 0.06 | 0.00 b ± 0.00 | 0.00 b ± 0.00 | 0.00 b ± 0.00 | 0.05 a,b ± 0.05 | 0.02 a,b ± 0.03 |

| cycC19:0,cis-9,10 (dihydrosterculic/cis-9,10-methyleneoctadecanoic) | 15.59 a ± 2.33 | 0.72 b ± 0.37 | 0.00 c ± 0.00 | 0.00 c ± 0.00 | 14.91 a ± 0.95 | 1.78 b ± 0.42 |

| cycC19:0,cis-10,11 (lactobacillic/cis-11,12-methyleneoctadecanoic) | 2.14 a ± 0.52 | 6.15 b ± 0.93 | 0.00 c ± 0.00 | 0.00 c ± 0.00 | 9.83 d ± 1.69 | 29.56 e ± 3.23 |

| 18:2,cis-9,trans-11 (conjugated octadecadienoic) | 1.42 a ± 0.33 | 2.98 b ± 0.24 | 2.36 b ± 0.24 | 2.06 b ± 0.08 | 1.13 a ± 0.16 | 0.21 c ± 0.13 |

| C18:2, CLA_1 (conjugated octadecadienoic) | 0.13 a ± 0.02 | 0.00 b ± 0.00 | 0.20 c ± 0.03 | 0.16 c ± 0.01 | 0.11 a ± 0.04 | 0.00 b ± 0.00 |

| 18:2,trans-10,cis-12 (conjugated octadecadienoic) | 0.77 a ± 0.20 | 0.00 b ± 0.00 | 2.09 c ± 0.32 | 1.95 c ± 0.28 | 1.21 d ± 0.14 | 0.00 b ± 0.00 |

| C18:2, CLA_2 (conjugated octadecadienoic) | 0.09 a ± 0.03 | 0.00 b ± 0.00 | 0.19 c ± 0.03 | 0.19 c ± 0.02 | 0.11 a ± 0.01 | 0.00 b ± 0.00 |

| C18:2, CLA_3 (conjugated octadecadienoic) | 0.02 a ± 0.03 | 0.19 b ± 0.01 | 0.15 c ± 0.04 | 0.13 c ± 0.03 | 0.10 a,b ± 0.01 | 0.00 d ± 0.00 |

| C18:2, CLA_4 (conjugated octadecadienoic) | 0.85 a ± 0.14 | 0.00 b ± 0.00 | 1.49 c ± 0.23 | 1.34 c ± 0.11 | 1.09 b ± 0.12 | 0.00 d ± 0.00 |

| ratio cycC19:0,cis-9,10/cycC19:0,cis-10,11 | 7.30 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.52 | 0.06 |

| ratio C18:1,cis-9/C18:1,cis-11 | 7.38 | 0.05 | 31.80 | 25.51 | 2.47 | 0.05 |

| ∑ unsaturated acids | 69.86 | 73.99 | 82.58 | 88.26 | 46.01 | 34.86 |

| ∑ saturated acids | 11.12 | 18.72 | 17.22 | 11.64 | 29.13 | 33.35 |

| ratio unsaturated/saturated | 6.28 | 3.95 | 4.80 | 7.58 | 1.58 | 1.05 |

| ∑ conjugated C18:2,cis-9,cis-12 acids | 3.27 | 3.18 | 6.48 | 5.83 | 3.75 | 0.21 |

| cis/trans | 31.75 | 81.37 | 27.12 | 31.28 | 20.18 | 26.72 |

| mono-/polyunsaturated | 12.46 | 14.38 | 11.38 | 13.63 | 9.37 | 111.43 |

| CLA/other conjugated fatty acids | 0.77 | 0.06 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 1.25 | 0.00 |

| Fatty Acid | Acid Name | Retention Time (min) | ECL | Electron Ionisation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C11:0 | undecanoic | 15.466 | 11.000 | 74, 87, 143, 157, 200 |

| C12:0 | lauric/dodecanoic | 17.655 | 12.000 | 74, 87, 143, 214 |

| C13:0 | tridecanoic | 19.751 | 13.000 | 74, 87, 143, 185, 228 |

| C14:0 | myristic/tetradecanoic | 21.757 | 14.000 | 74, 87, 143, 199, 242 |

| C10:0,2OH | 2-hydroxydecanoic | 22.658 | 14.481 | 69, 83, 143, 228 |

| C15:0,iso | iso-13-methyltetradecanoic | 22.777 | 14.542 | 74, 87, 143, 213, 256 |

| C15:0,anteiso | anteiso-12-methyltetradecanoic | 23.084 | 14.701 | 74, 87, 143, 213, 256 |

| C15:0 | pentadecanoic | 23.673 | 15.000 | 74, 87, 143, 213, 256 |

| C16:0,iso | iso-14-methylpentadecanoic | 24.647 | 15.541 | 74, 87, 143, 227, 270 |

| C16:0 | palmitic/hexadecanoic | 25.505 | 16.000 | 74, 87, 143, 227, 270 |

| C17:0,iso | iso-15-methylhexadecanoic | 26.442 | 16.541 | 74, 87, 143, 241, 284 |

| C16:1,cis-9 | palmitoleic/hexadecenoic | 26.485 | 16.565 | 69, 83, 96, 152, 236 |

| C12:0,2OH | 2-hydroxydodecanoic | 26.636 | 16.653 | 69, 83, 97, 171, 230 |

| C17:0 | heptadecanoic | 27.255 | 17.000 | 74, 87, 143, 241, 284 |

| cycC17:0,cis-9,10 | cis-9,10-methylenehexadecanoic | 27.965 | 17.432 | 69, 74, 83, 97, 250 |

| C18:0 | stearic/octadecanoic | 28.934 | 18.000 | 74, 87, 143, 255, 298 |

| C12:0,3OH | 3-hydroxydodecanoic | 29.175 | 18.159 | 71, 74, 83, 103 |

| C18:1,trans-9 | elaidic/octadecenoic | 29.492 | 18.351 | 69, 74, 83, 97, 123, 264 |

| C18:1,cis-9 | oleic/octadecenoic | 29.705 | 18.486 | 69, 74, 83, 97, 123, 264 |

| C14:0,2OH | 2-hydroxytetradecanoic | 30.221 | 18.797 | 69, 83, 97, 199 |

| C19:0 | nonadecanoic | 30.545 | 19.000 | 74, 87, 143, 312 |

| C18:2,cis-9,cis-12 | linoleic/cis-9,cis12-octadecadienoic | 31.015 | 19.307 | 97, 81, 95, 123, 294 |

| cycC19:0,cis-9,10 | dihydrosterculic/cis-9,10-methylene-octadecanoic | 31.122 | 19.376 | 69, 74, 83, 97, 123, 278 |

| C20:0 | eicosanic | 32.086 | 20.000 | 74, 87, 143, 326 |

| C14:0,3-OH | 3-hydroxytetradecanoic | 32.592 | 20.318 | 71, 74, 103 |

| C16:0,2-OH | 2-hydroxyhexadecanoic | 33.475 | 20.864 | 69, 83, 97, 227 |

| Fatty Acid | Acid Name | Retention Time (min) | ECL | Electron Ionisation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C10:0 | caproic/decanoic | 13.165 | 10.000 | 74, 87, 143 |

| C12:0 | lauric/dodecanoic | 17.629 | 12.000 | 74, 87, 143, 157, 200 |

| C14:0 | myristic/tetradecanoic | 21.722 | 14.000 | 74, 87, 143, 199, 242 |

| C15:0,iso | iso-13-methyltetradecanoic | 22.740 | 14.545 | 74, 87, 97 |

| C15:0,anteiso | anteiso-12-methyltetradecanoic | 23.035 | 14.698 | 74, 87, 143, 256 |

| C15:0 | pentadecanoic | 23.626 | 15.000 | 74, 87, 143, 256 |

| C 16:0 | palmitic/hexadecanoic | 25.477 | 16.000 | 74, 87, 143, 227, 270 |

| C16:1,trans-9 | palmitelaidic/trans-9-hexadecenoic | 26.162 | 16.394 | 69, 83, 96, 152, 236 |

| C16:1,cis-9 | palmitoleic/cis-9-hexadecenoic | 26.442 | 16.552 | 69, 83, 96, 152, 236 |

| C12:0,2OH | 2-hydroxydodecanoic | 26.680 | 16.633 | 69, 83, 97 |

| cycC17:0,cis-9,10 | cis-9,10-methylenehexadecanoic | 27.919 | 17.420 | 69, 74, 83, 250 |

| C18:0 | stearic/octadecanoic | 28.869 | 18.000 | 74, 87, 143, 255, 298 |

| C18:1 | octadecenoic | 28.935 | 18.040 | 69, 74, 83 |

| C18:1,trans-6 | petroselaidic/trans-6-octadecenoic | 29.063 | 18.118 | 69, 74, 83 |

| C18:1,trans-9 | elaidic/trans-9-octa-decenoic | 29.143 | 18.167 | 69, 74, 83, 97, 143 |

| C18:1,trans-11 | trans-vaccenic/trans-11-octadecenoic | 29.436 | 18.343 | 69, 74, 83, 97, 264 |

| C18:1,cis-6 | petroselinic/cis-6-octadecenoic | 29.538 | 18.404 | 69, 74, 83, 97, 143 |

| C18:1,cis-9 | oleic/cis-9-octadecenoic | 29.660 | 18.477 | 69, 74, 83, 97, 123, 264 |

| C18:1,cis-11 | cis-vaccenic/cis-11-octadecenoic | 29.808 | 18.565 | 69, 74, 83, 97, 123, 264 |

| C18:2,trans-9,trans-12 | linoelaidic/trans-9, trans-12-octadecadienoic | 30.289 | 18.847 | 67, 81, 95 |

| C18:2,cis-9,cis-12 | linoleic/cis-9,cis-12-octadecadienoic | 30.963 | 19.272 | 67, 81, 95, 294 |

| cycC19:0,cis-9,10 | dihydrosterculic/cis-9,10-methyleneoctadecanoic | 31.071 | 19.343 | 69, 74, 83, 97, 123, 278 |

| cycC19:0,cis-10,11 | lactobacillic/cis-11,12-methyleneoctadecanoic | 31.159 | 19.401 | 69, 74, 83, 97, 123, 278 |

| 18:2,cis-9,trans-11 | conjugated octadecadienoic | 32.868 | 20.492 | 67, 81, 95, 123, 294 |

| C18:2, CLA_1 | conjugated octadecadienoic | 32.965 | 20.552 | 67, 81, 95, 123, 294 |

| 18:2,trans-10,cis-12 | conjugated octadecadienoic | 33.098 | 20.634 | 67, 81, 95, 109, 263, 294 |

| C18:2_CLA_2 | conjugated octadecadienoic | 33.219 | 20.709 | 67, 81, 95, 123, 294 |

| C18:2_CLA_3 | conjugated octadecadienoic | 33.323 | 20.773 | 67, 81, 95, 294 |

| C18:2_CLA_4 | conjugated octadecadienoic | 33.631 | 20.961 | 67, 81, 95, 123, 294 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zaręba, D.; Ziarno, M. Chromatographic and Molecular Insights into Fatty Acid Profiles of Thermophilic Lactobacillus Strains: Influence of Tween 80TM Supplementation. Molecules 2026, 31, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010014

Zaręba D, Ziarno M. Chromatographic and Molecular Insights into Fatty Acid Profiles of Thermophilic Lactobacillus Strains: Influence of Tween 80TM Supplementation. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleZaręba, Dorota, and Małgorzata Ziarno. 2026. "Chromatographic and Molecular Insights into Fatty Acid Profiles of Thermophilic Lactobacillus Strains: Influence of Tween 80TM Supplementation" Molecules 31, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010014

APA StyleZaręba, D., & Ziarno, M. (2026). Chromatographic and Molecular Insights into Fatty Acid Profiles of Thermophilic Lactobacillus Strains: Influence of Tween 80TM Supplementation. Molecules, 31(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010014