The Health-Promoting Potential of Wafers Enriched with Almond Peel

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. The Consumer Evaluation

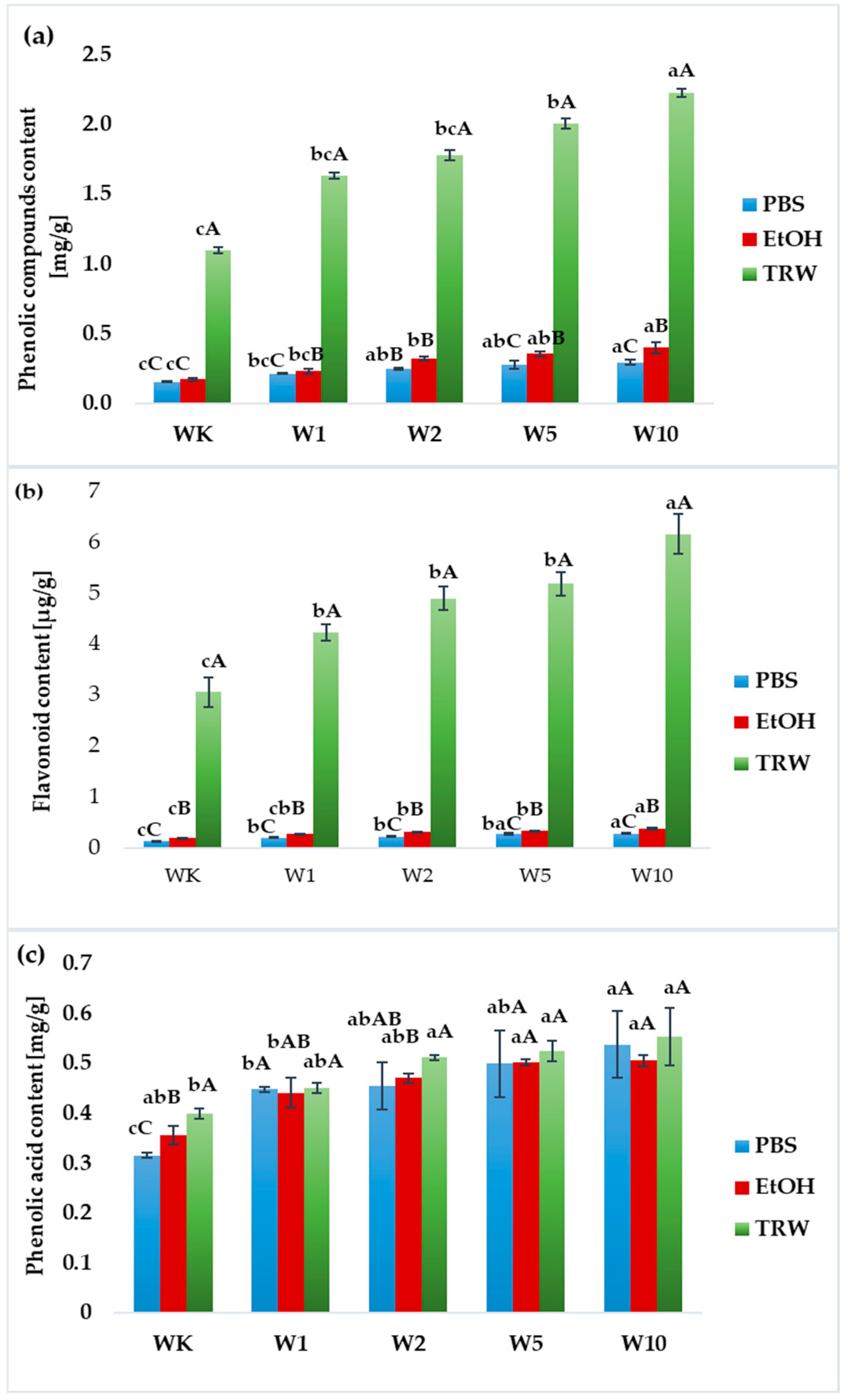

2.2. Bioactive Compound Content

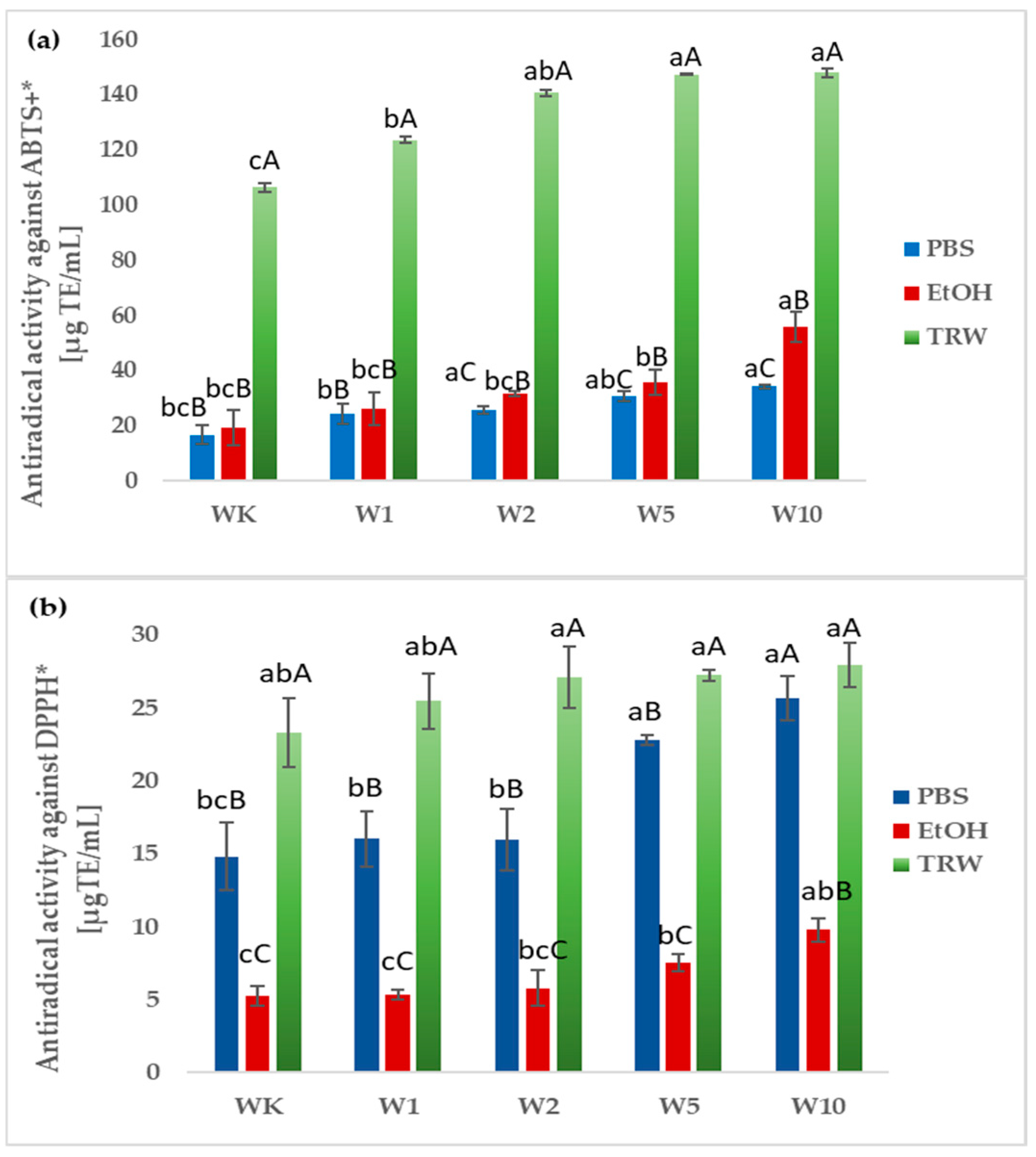

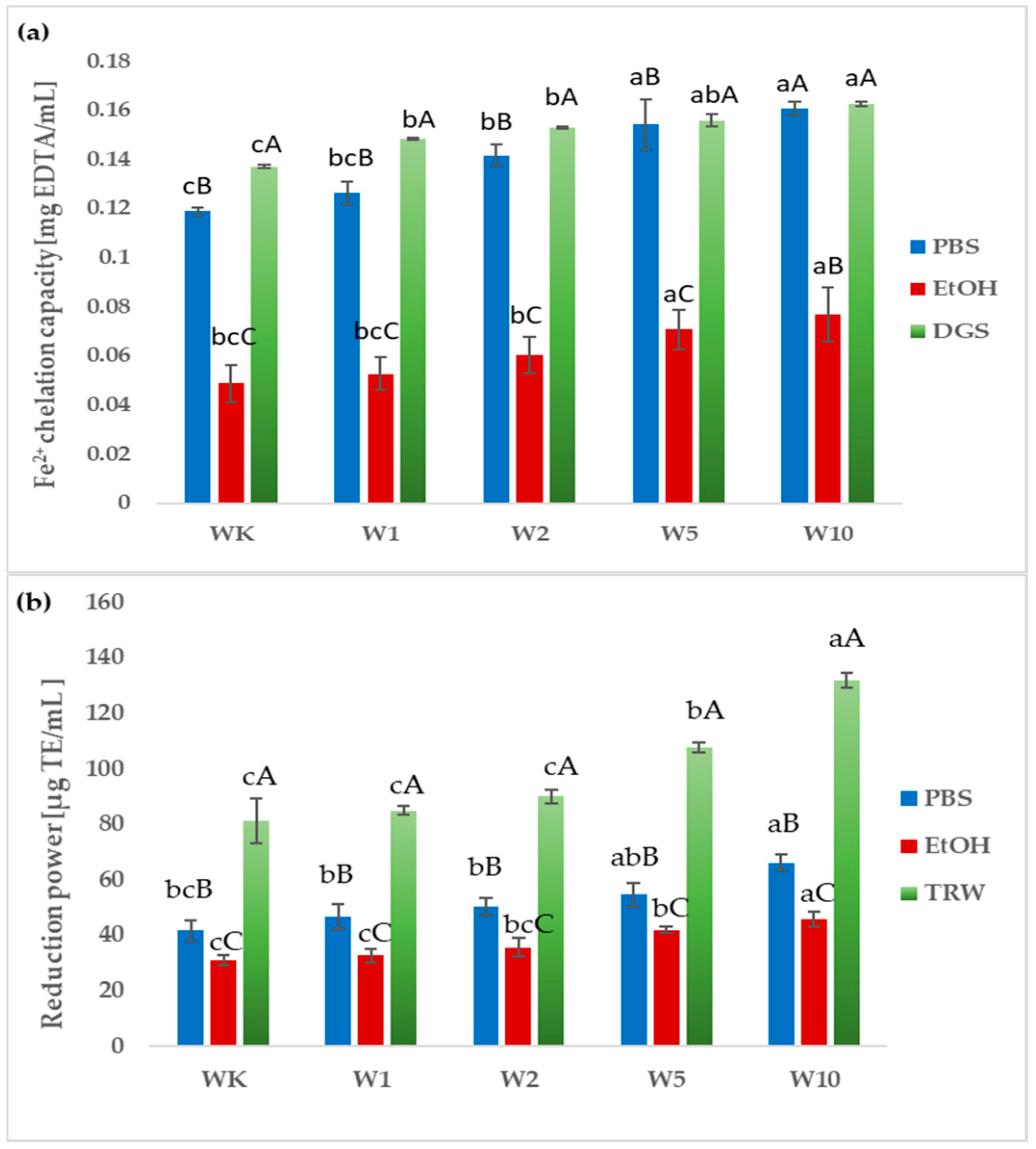

2.3. Antioxidant Properties

2.4. Inhibition of the Activity of Enzymes Involved in the Pathogenesis of Obesity, Hypertension, and Inflammation

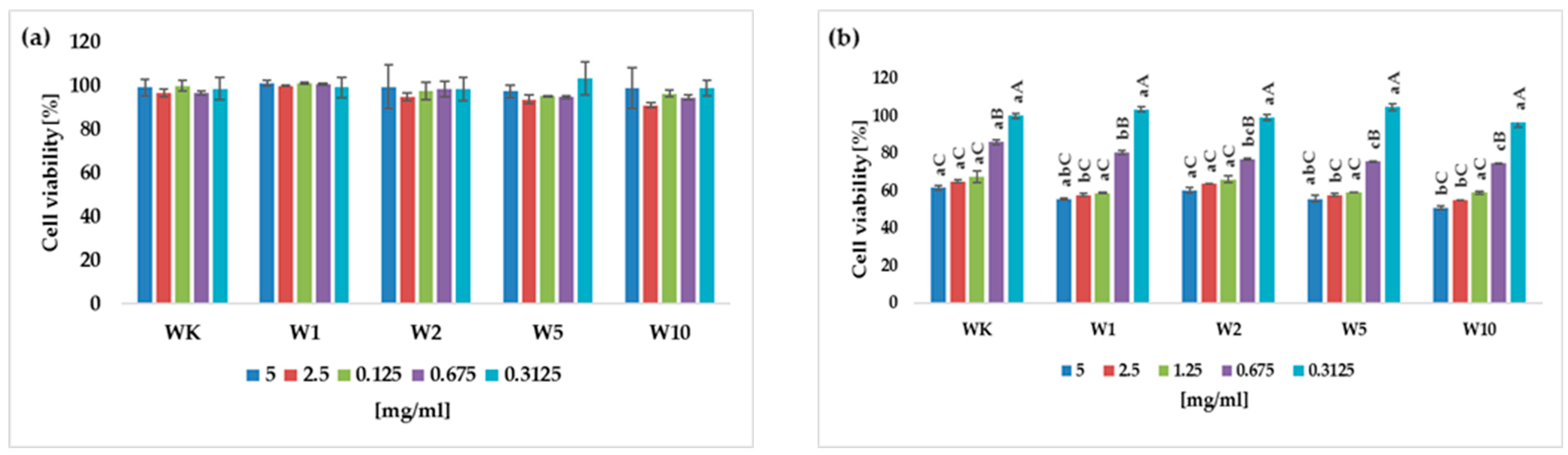

2.5. Potential Antiproliferative Activity

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals

4.2. Preparation of Almond Peels

4.3. Wafers Preparation

4.4. The Semi-Consumer Evaluation

4.5. Preparation of Extracts and Hydrolysates

4.5.1. Preparations of Ethanol Extracts

4.5.2. Preparations of PBS Extracts

4.5.3. In Vitro Digestion

4.6. Peptide Content Determination

4.7. Phenolic Content Determination

4.7.1. Total Phenolic Content

4.7.2. Flavonoid Content

4.7.3. Phenolic Acid Content

4.8. Qualitative Analysis by LC-QTOF-MS

4.9. The Antioxidant Activity

4.9.1. Determination of the DPPH Radicals Neutralization Capacity

- %—antiradical activity;

- As—absorbance of the tested sample;

- Ac—absorbance of the control sample.

4.9.2. Determination of the ABTS Radical Neutralization Capacity

- %—antiradical activity;

- As—absorbance of the tested sample;

- Ac—absorbance of the control sample.

4.9.3. The Iron Ion-Chelating Capacity Assay

- %—chelating capacity;

- As—absorbance of the tested sample;

- Ac—absorbance of the control sample.

4.9.4. The Reduction Power Determination

4.10. Enzyme Inhibitory Assays

4.10.1. Potential Antihypertension Properties

4.10.2. Potential of Anti-Obesity Activity

4.10.3. Potential Anti-Inflammatory Properties

4.11. Cancer Cell Viability Assay

4.11.1. Cell Culture

4.11.2. Viability Assay

4.12. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ollani, S.; Peano, C.; Sottile, F. Recent Innovations on the Reuse of Almond and Hazelnut By-Products: A Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Hao, J.; Wang, W. Study of Almond Shell Characteristics. Materials 2018, 11, 1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prgomet, I.; Goncalves, B.; Domínguez-Perles, R.; Pascual-Seva, N.; Barros, A.I.R.N.A. Valorization Challenges to Almond Residues: Phytochemical Composition and Functional Application. Molecules 2017, 22, 1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Perez, P.; Xiao, J.; Munekata, P.E.S.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Barba, F.J.; Rajoka, M.S.R.; Barros, L.; Mascoloti Sprea, R.; Amaral, J.S.; Prieto, M.A.; et al. Revalorization of Almond By-Products for the Design of Novel Functional Foods: An Updated Review. Foods 2021, 10, 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barral-Martinez, M.; Fraga-Corral, M.; Garcia-Perez, P.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Prieto, M.A. Almond By-Products: Valorization for Sustainability and Competitiveness of the Industry. Foods 2021, 10, 1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahlaoui, M.; Vecchia, S.B.D.; Giovine, F.; Kbaier, H.B.H.; Bouzouita, N.; Pereira, L.B.; Zeppa, G. Characterization of Polyphenolic Compounds Extracted from Different Varieties of Almond Hulls (Prunus dulcis L.). Antioxidants 2019, 8, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreca, D.; Nabavi, S.M.; Sureda, A.; Rasekhian, M.; Raciti, R.; Silva, A.S.; Annunziata, G.; Arnone, A.; Tenore, G.C.; Süntar, İ.; et al. Almonds (Prunus dulcis Mill. D. A. Webb): A Source of Nutrients and Health-Promoting Compounds. Nutrients 2020, 12, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauro, M.R.; Marzocco, S.; Rapa, S.F.; Musumeci, T.; Giannone, V.; Picerno, P.; Aquino, R.P.; Puglisi, G. Recycling of Almond By-Products for Intestinal Inflammation: Improvement of Physical-Chemical, Technological and Biological Characteristics of a Dried Almond Skins Extract. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Raptova, R.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Reactive Oxygen Species, Toxicity, Oxidative Stress, and Antioxidants: Chronic Diseases and Aging; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; Volume 97, ISBN 0123456789. [Google Scholar]

- Mandalari, G.; Tomaino, A.; Arcoraci, T.; Martorana, M.; Turco, V.L.; Cacciola, F.; Rich, G.T.; Bisignano, C.; Saija, A.; Dugo, P.; et al. Characterization of Polyphenols, Lipids and Dietary Fibre from Almond Skins (Amygdalus communis L.). J. Food Compos. Anal. 2010, 23, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isfahlan, A.J.; Mahmoodzadeh, A.; Hassanzadeh, A.; Heidari, R.; Jamei, R. Antioxidant and Antiradical Activities of Phenolic Extracts from Iranian Almond (Prunus amygdalus L.) Hulls and Shells. Turk. J. Biol. 2010, 34, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, V.; Oliveira, I.; Pereira, J.A.; Gonçalves, B. Almond By-Products: A Comprehensive Review of Composition, Bioactivities, and Influencing Factors. Foods 2025, 14, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubczyk, A.; Karaś, M.; Złotek, U.; Szymanowska, U.; Baraniak, B.; Bochnak, J. Peptides Obtained from Fermented Faba Bean Seeds (Vicia faba) as Potential Inhibitors of an Enzyme Involved in the Pathogenesis of Metabolic Syndrome. LWT 2019, 105, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanyo, P.; Chamsai, T.; Toontom, N.; Nghiep, L.K.; Tudpor, K. Evaluation of In Vitro Digested Mulberry Leaf Tea Kombucha: A Functional Fermented Beverage with Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, Antihyperglycemic, and Antihypertensive Potentials. Fermentation 2025, 11, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajfathalian, M.; Ghelichi, S.; Jacobsen, C. Anti-Obesity Peptides from Food: Production, Evaluation, Sources, and Commercialization. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva-Velasco, D.L.; Cervantes-Pérez, L.G.; Sánchez-Mendoza, A. ACE Inhibitors and Their Interaction with Systems and Molecules Involved in Metabolism. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Wang, H.; Weng, N.; Wei, T.; Tian, X.; Lu, J.; Lyu, M.; Wang, S. Novel Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme and Pancreatic Lipase Oligopeptide Inhibitors from Fermented Rice Bran. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1010005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.T.; Liu, X.T.; Chen, Q.X.; Shi, Y. Lipase Inhibitors for Obesity: A Review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 128, 110314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasqualone, A.; Laddomada, B.; Boukid, F.; de Angelis, D.; Summo, C. Use of Almond Skins to Improve Nutritional and Functional Properties of Biscuits: An Example of Upcycling. Foods 2020, 9, 1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandalari, G.; Vardakou, M.; Faulks, R.; Bisignano, C.; Martorana, M.; Smeriglio, A.; Trombetta, D. Food Matrix Effects of Polyphenol Bioaccessibility from Almond Skin during Simulated Human Digestion. Nutrients 2016, 8, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, I.; Marinho, B.; Szymanowska, U.; Karas, M.; Vilela, A. Chemical and Sensory Properties of Waffles Supplemented with Almond Skins. Molecules 2023, 28, 5674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Zhu, M.; Wan, X.; Zhai, X.; Ho, C.-T.; Zhang, L. Food Polyphenols and Maillard Reaction: Regulation Effect and Chemical Mechanism. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 4904–4920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Guo, X.; Guo, R.; Zhu, L.; Qiu, X.; Yu, X.; Chai, J.; Gu, C.; Feng, Z. Insights into the Effects of Extractable Phenolic Compounds and Maillard Reaction Products on the Antioxidant Activity of Roasted Wheat Flours with Different Maturities. Food Chem. X 2023, 17, 100548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez, M.; Ronda, F.; Blanco, C.A.; Caballero, P.A.; Apesteguía, A. Effect of Dietary Fibre on Dough Rheology and Bread Quality. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2003, 216, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudha, M.L.; Vetrimani, R.; Leelavathi, K. Influence of Fibre from Different Cereals on the Rheological Characteristics of Wheat Flour Dough and on Biscuit Quality. Food Chem. 2007, 100, 1365–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevallier, S.; Colonna, P.; Della Valle, G.; Lourdin, D. Contribution of Major Ingredients during Baking of Biscuit Dough Systems. J. Cereal Sci. 2000, 31, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, C.; Debonne, E.; Versele, S.; Van Bockstaele, F.; Eeckhout, M. Technological Evaluation of Fiber Effects in Wheat-Based Dough and Bread. Foods 2024, 13, 2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanowska, U.; Karaś, M.; Bochnak-Niedźwiecka, J. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Potential and Consumer Acceptance of Wafers Enriched with Freeze-Dried Raspberry Pomace. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaś, M.; Szymanowska, U.; Borecka, M.; Jakubczyk, A.; Kowalczyk, D. Antioxidant Properties of Wafers with Added Pumpkin Seed Flour Subjected to In Vitro Digestion. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weldeyohanis Gebremariam, F.; Tadesse Melaku, E.; Sundramurthy, V.P.; Woldemichael Woldemariam, H. Development of Functional Cookies Form Wheat-Pumpkin Seed Based Composite Flour. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, D.; Moreira, M.M.; Švarc-Gajić, J.; Vallverdú-Queralt, A.; Brezo-Borjan, T.; Delerue-Matos, C.; Rodrigues, F. In-Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion of Functional Cookies Enriched with Chestnut Shells Extract: Effects on Phenolic Composition, Bioaccessibility, Bioactivity, and α-Amylase Inhibition. Food Biosci. 2023, 53, 102766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, S.; Hossain, M.L.; Sostaric, T.; Lim, L.Y.; Foster, K.J.; Locher, C. Investigating Flavonoids by HPTLC Analysis Using Aluminium Chloride as Derivatization Reagent. Molecules 2024, 29, 5161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolescu, A.; Bunea, C.I.; Mocan, A. Total Flavonoid Content Revised: An Overview of Past, Present, and Future Determinations in Phytochemical Analysis. Anal. Biochem. 2025, 700, 115794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, G.; Kay, C.D.; Crozier, A. The Bioavailability, Transport, and Bioactivity of Dietary Flavonoids: A Review from a Historical Perspective. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2018, 17, 1054–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.A. Anti-Hypertensive Effect of Cereal Antioxidant Ferulic Acid and Its Mechanism of Action. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamać, M. Antioxidant Activity of Tannin Fractions Isolated from Buckwheat Seeds and Groats. JAOCS J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2010, 87, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roychoudhury, S.; Sinha, B.; Choudhury, B.P.; Jha, N.K.; Palit, P.; Kundu, S.; Mandal, S.C.; Kolesarova, A.; Yousef, M.I.; Ruokolainen, J.; et al. Scavenging Properties of Plant-Derived Natural Biomolecule Para-Coumaric Acid in the Prevention of Oxidative Stress-Induced Diseases. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adefegha, S.A.; Adesua, O.; Oboh, G. Ameliorative Influence of Co-Administration of p-Coumaric Acid and Lisinopril on Blood Pressure and Crucial Enzymes Relevant to Hypertension in L-Arginine N-ω-Nitro-L-Arginine Methyl Ester (L-NAME)-Induced Hypertension in Rats. Comp. Clin. Path. 2025, 34, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponnian, S.M.P.; Stanely, S.P.; Roy, A.J. Cardioprotective Effects of P-Coumaric Acid on Tachycardia, Inflammation, Ion Pump Dysfunction, and Electrolyte Imbalance in Isoproterenol-Induced Experimental Myocardial Infarction. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2024, 38, e23668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parcheta, M.; Świsłocka, R.; Świderski, G.; Matejczyk, M.; Lewandowski, W. Spectroscopic Characterization and Antioxidant Properties of Mandelic Acid and Its Derivatives in a Theoretical and Experimental Approach. Materials 2022, 15, 5413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maneesai, P.; Potue, P.; Khamseekaew, J.; Sangartit, W.; Rattanakanokchai, S.; Poasakate, A.; Pakdeechote, P. Kaempferol Protects against Cardiovascular Abnormalities Induced by Nitric Oxide Deficiency in Rats by Suppressing the TNF-α Pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 960, 176112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Takahashi, Y.; Yamaki, K. Inhibitory Effect of Catechin-Related Compounds on Renin Activity. Biomed. Res. 2013, 34, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wang, R.; Huang, J.; Cai, Q.; Yang, C.S.; Wan, X.; Xie, Z. Effects and Mechanisms of Tea Regulating Blood Pressure: Evidences and Promises. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiñones, M.; Margalef, M.; Arola-Arnal, A.; Muguerza, B.; Miguel, M.; Aleixandre, A. The Blood Pressure Effect and Related Plasma Levels of Flavan-3-Ols in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Food Funct. 2015, 6, 3479–3489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Yao, R.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Huang, Z.; Du, B.; Zhang, D.; Wu, L.; Xiao, L.; Zhang, Y. Isorhamnetin Protects against Cardiac Hypertrophy through Blocking PI3K–AKT Pathway. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2017, 429, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.Y.; Qin, L.Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, J.; Arigoni, F.; Zhang, W. Effect of Oral L-Arginine Supplementation on Blood Pressure: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trials. Am. Heart J. 2011, 162, 959–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardiansyah, N.; Shirakawa, H.; Inagawa, Y.; Koseki, T.; Komai, M. Regulation of Blood Pressure and Glucose Metabolism Induced by L-Tryptophan in Stroke-Prone Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Nutr. Metab. 2011, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gad, M.Z.; Abu el Maaty, M.A.; El-Maraghy, S.A.; Fahim, A.T.; Hamdy, M.A. Investigating the Cardio-Protective Abilities of Supplemental L-Arginine on Parameters of Endothelial Function in a Hypercholesterolemic Animal Model. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2014, 60, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouayed, J.; Hoffmann, L.; Bohn, T. Total Phenolics, Flavonoids, Anthocyanins and Antioxidant Activity Following Simulated Gastro-Intestinal Digestion and Dialysis of Apple Varieties: Bioaccessibility and Potential Uptake. Food Chem. 2011, 128, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, S.H.; Jang, J.S.; Lee, M.H. Synergistic Effect of Fruit–Seed Mixed Juice on Inhibition of Angiotensin I-Converting Enzyme and Activation of NO Production in EA.Hy926 Cells. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2019, 28, 881–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubczyk, A.; Kiersnowska, K.; Ömeroğlu, B.; Gawlik-Dziki, U.; Tutaj, K.; Rybczyńska-Tkaczyk, K.; Szydłowska-Tutaj, M.; Złotek, U.; Baraniak, B. The Influence of Hypericum perforatum L. Addition to Wheat Cookies on Their Antioxidant, Anti-Metabolic Syndrome, and Antimicrobial Properties. Foods 2021, 10, 1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanowska, U.; Karaś, M.; Jakubczyk, A.; Kocki, J.; Szymanowski, R.; Kapusta, I.T. Raspberry Pomace as a Good Additive to Apple Freeze-Dried Fruit Bars: Biological Properties and Sensory Evaluation. Molecules 2024, 29, 5690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Yin, R.; Howell, K.; Zhang, P. Activity and Bioavailability of Food Protein-Derived Angiotensin-I-Converting Enzyme–Inhibitory Peptides. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 1150–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faraoni, P.; Campo, M.; Gnerucci, A.; Vignolini, P.; Ranaldi, F.; Iantomasi, T.; Bini, L.; Gori, M.; Giordani, E.; Natale, R.; et al. Polyphenolic Profile and Biological Activities in HT29 Intestinal Epithelial Cells of Feijoa sellowiana Fruit Extract. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crascì, L.; Lauro, M.R.; Puglisi, G.; Panico, A. Natural Antioxidant Polyphenols on Inflammation Management: Anti-Glycation Activity vs Metalloproteinases Inhibition. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 893–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandalari, G.; Bisignano, C.; Genovese, T.; Mazzon, E.; Wickham, M.S.J.; Paterniti, I.; Cuzzocrea, S. Natural Almond Skin Reduced Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in an Experimental Model of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2011, 11, 915–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Lu, P.; Wu, H.; de Souza, T.S.P.; Suleria, H.A.R. In Vitro Digestion and Colonic Fermentation of Phenolic Compounds and Their Bioaccessibility from Raw and Roasted Nut Kernels. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 2727–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, D.; López-Yerena, A.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.; Vallverdú-Queralt, A.; Delerue-Matos, C.; Rodrigues, F. Predicting the Effects of In-Vitro Digestion in the Bioactivity and Bioaccessibility of Antioxidant Compounds Extracted from Chestnut Shells by Supercritical Fluid Extraction—A Metabolomic Approach. Food Chem. 2024, 435, 137581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Saez, N.; Fernandez-Gomez, B.; Cai, W.; Uribarri, J.; del Castillo, M.D. In Vitro Formation of Maillard Reaction Products during Simulated Digestion of Meal-Resembling Systems. Food Res. Int. 2019, 118, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeriglio, A.; Mandalari, G.; Bisignano, C.; Filocamo, A.; Barreca, D.; Bellocco, E.; Trombetta, D. Polyphenolic content and biological properties of Avola almond (Prunus dulcis Mill. DA Webb) skin and its industrial byproducts. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 83, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussio, C.; Garcia-Perez, P.; Moret, E.; Catena, S.; Lucini, L. The Role, Mechanisms and Evaluation of Natural Chelating Agents in Food Stability: A Review. Food Chem. 2025, 496, 146682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, S.M.G.; Reis, R.S.; Cardoso, S.M.; Pezzani, R.; Paredes-Osses, E.; Seilkhan, A.; Ydyrys, A.; Martorell, M.; Sönmez Gürer, E.; Setzer, W.N.; et al. Phytates as a Natural Source for Health Promotion: A Critical Evaluation of Clinical Trials. Front. Chem. 2023, 11, 1174109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloot, A.P.M.; Kalschne, D.L.; Amaral, J.A.S.; Baraldi, I.J.; Canan, C. A review of phytic acid sources, obtention, and applications. Food Rev. Int. 2023, 39, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picerno, P.; Crascì, L.; Iannece, P.; Esposito, T.; Franceschelli, S.; Pecoraro, M.; Giannone, V.; Panico, A.M.; Aquino, R.P.; Lauro, M.R. A Green Bioactive By-Product Almond Skin Functional Extract for Developing Nutraceutical Formulations with Potential Antimetabolic Activity. Molecules 2023, 28, 7913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rein, M.J.; Renouf, M.; Cruz-Hernandez, C.; Actis-Goretta, L.; Thakkar, S.K.; da Silva Pinto, M. Bioavailability of Bioactive Food Compounds: A Challenging Journey to Bioefficacy. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 75, 588–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Pan, S.; Li, F.; Xu, X.; Xing, H. Plant-Derived Bioactive Compounds and Potential Health Benefits: Involvement of the Gut Microbiota and Its Metabolic Activity. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakrim, S.; El Omari, N.; El Hachlafi, N.; Bakri, Y.; Lee, L.H.; Bouyahya, A. Dietary Phenolic Compounds as Anticancer Natural Drugs: Recent Update on Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Trials. Foods 2022, 11, 3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodavirdipour, A.; Zarean, R.; Safaralizadeh, R. Evaluation of the Anti-Cancer Effect of Syzygium Cumini Ethanolic Extract on HT-29 Colorectal Cell Line. J. Gastrointest. Cancer 2021, 52, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siedlecka-Kroplewska, K.; Wrońska, A.; Kmieć, Z. Piceatannol, a Structural Analog of Resveratrol, Is an Apoptosis Inducer and a Multidrug Resistance Modulator in Hl-60 Human Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Jia, R.; Wang, C.; Hu, T.; Wang, F. Piceatannol Promotes Apoptosis via Up-Regulation of MicroRNA-129 Expression in Colorectal Cancer Cell Lines. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 452, 775–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minekus, M.; Alminger, M.; Alvito, P.; Ballance, S.; Bohn, T.; Bourlieu, C.; Carrière, F.; Boutrou, R.; Corredig, M.; Dupont, D.; et al. A Standardised Static in Vitro Digestion Method Suitable for Food—An International Consensus. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodkorb, A.; Egger, L.; Alminger, M.; Alvito, P.; Assunção, R.; Ballance, S.; Bohn, T.; Bourlieu-Lacanal, C.; Boutrou, R.; Carrière, F.; et al. INFOGEST Static in Vitro Simulation of Gastrointestinal Food Digestion. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 991–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler-Nissen, J. Determination of the Degree of Hydrolysis of Food Protein Hydrolysates by Trinitrobenzenesulfonic Acid. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1979, 27, 1256–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of Total Phenolics with Phosphomolybdic-Phosphotungstic Acid Reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamaison, J.L.C.; Carnet, A. Contents in Main Flavonoid Compounds of Crataegus Monogyna Jacq. and Crataegus Laevigata (Poiret) DC Flowers at Different Development Stages. Pharm. Acta Helv. 1990, 65, 315–320. [Google Scholar]

- Szaufer-Hajdrych, M.; Goślińska, O. The Quantitative Determination of Phenolic Acids and Antimicrobial Activity of Symphoricarpos albus (L.) Blake. Acta Pol. Pharm. 2004, 1, 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a Free Radical Method to Evaluate Antioxidant Activity. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant Activity Applying an Improved ABTS Radical Cation Decolorization Assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, E.A.; Welch, B. Role of Ferritin as a Lipid Oxidation Catalyst in Muscle Food. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1990, 38, 674–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido, R.; Bravo, L.; Saura-Calixto, F. Antioxidant Activity of Dietary Polyphenols as Determined by a Modified Ferric Reducing/Antioxidant Power Assay. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 3396–3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaś, M.; Jakubczyk, A.; Szymanowska, U.; Jęderka, K.; Lewicki, S.; Złotek, U. Different Temperature Treatments of Millet Grains Affect the Biological Activity of Protein Hydrolyzates and Peptide Fractions. Nutrients 2019, 11, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymanowska, U.; Baraniak, B.; Bogucka-Kocka, A. Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, and Postulated Cytotoxic Activity of Phenolic and Anthocyanin-Rich Fractions from Polana Raspberry (Rubus idaeus L.) Fruit and Juice—In Vitro Study. Molecules 2018, 23, 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| PBS | EtOH | TRW | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WK | W10 | WK | W10 | WK | W10 | |

| Phenolic acids | ||||||

| Caffeic acid | + | + | ||||

| Ferulic acid | + | + | ||||

| p-Coumaric acid | + | + | ||||

| Fatty acids and amino acids | ||||||

| Linoleic acid | + | + | + | |||

| Methionine | + | + | ||||

| Tryptophan | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Valine | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Phenylalanine | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Tyrosine | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Arginine | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Leucine | + | + | ||||

| Isoleucine | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Vitamins | ||||||

| Vitamin B2 (riboflavin) | + | |||||

| Vitamin B3 (niacin) | + | |||||

| Vitamin B5 (pantothenic acid) | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Vitamin E (γ tocopherol) | + | + | ||||

| Flavonoids and other polyphenols | ||||||

| Kaempferol | + | |||||

| Apigenin7-O-apiosyl-glucoside | + | + | + | + | ||

| Isorhamnetin-3-O-rutinoside | + | |||||

| Isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside | + | |||||

| Catechin | + | |||||

| Epicatechin | + | |||||

| Naringenin | + | |||||

| Eriodictyol | + | |||||

| Secoisolariciresinol | + | |||||

| Piceatannol 3-O-glucoside | + | + | ||||

| Benzaldehyde | + | + | ||||

| Mandelic acid | + | |||||

| Molecular Formula | Rt (min) | Observed Mass | m/z | Detected Ion | Score | Dif (ppm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenolic acids | |||||||

| Caffeic acid | C9H8O4 | 1.953 | 180.0423 | 239.0575 | [M+CH3COO]− | 75.3 | 8.53 |

| Ferulic acid | C10H10O4 | 1.953 | 194.0579 | 239.0575 | [M+HCOO]− | 75.3 | 7.92 |

| p-Coumaric acid | C9H8O3 | 0.582 | 164.0473 | 165.0539 | [M+H]+ | 76.93 | −2.10 |

| Fatty acids and amino acids | |||||||

| Linoleic acid | C18H32O2 | 14.734 | 280.2402 | 281.2469 | [M+H]+ | 78.83 | −0.20 |

| Methionine | C5H11NO2S | 0.549 | 149.0510 | 150.0591 | [M+H]+ | 96.19 | 5.44 |

| Tryptophan | C11H12N2O2 | 1.914 | 204.0899 | 205.0979 | [M+H]+ | 97.27 | 3.30 |

| Valine | C5H11NO2 | 9.157 | 117.0792 | 118.0865 | [M+H]+ | 95.93 | 1.97 |

| Phenylalanine | C9H11NO2 | 0.932 | 165.079 | 166.0861 | [M+H]+ | 99.8 | −1.01 |

| Tyrosine | C9H11NO3 | 0.582 | 181.0739 | 182.0811 | [M+H]+ | 99.84 | −0.17 |

| Arginine | C6H14N4O2 | 0.383 | 174.1117 | 175.1184 | [M+H]+ | 98.42 | −3.27 |

| Leucine | C6H13NO2 | 1.165 | 131.0946 | 132.1013 | [M+H]+ | 97.42 | −4.09 |

| Isoleucine | C6H13NO2 | 0.616 | 131.0947 | 132.1020 | [M+H]+ | 99.56 | 0.72 |

| Vitamins | |||||||

| Vitamin B2 (riboflavin) | C17H20N4O6 | 4.295 | 376.1383 | 377.1446 | [M+H]+ | 92.76 | −1.26 |

| Vitamin B3 (niacin) | C6H5NO2 | 0.489 | 123.0325 | 124.0398 | [M+H]+ | 77.74 | 3.90 |

| Vitamin B5 (pantothenic acid) | C9H17NO5 | 1.215 | 219.1107 | 220.1181 | [M+H]+ | 99.19 | 0.89 |

| Vitamin E (γ tocopherol) | C28H48O2 | 15.932 | 416.3654 | 461.3636 | [M+HCOO]− | 84.9 | −3.22 |

| Flavonoids and other polyphenols | |||||||

| Kaempferol | C15H10O6 | 6.992 | 286.0477 | 287.0534 | [M+H]+ | 81.77 | −5.36 |

| Apigenin7-O-apiosyl-glucoside | C26H28O14 | 4.330 | 564.1488 | 565.1558 | [M+H]+ | 84.21 | 2.10 |

| Isorhamnetin-3-O-rutinoside | C28H32O16 | 5.170 | 624.169 | 625.1766 | [M+H]+ | 99.74 | 0.50 |

| Isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside | C22H22O12 | 5.270 | 478.1111 | 479.1182 | [M+H]+ | 91.68 | 0.75 |

| Catechin | C15H14O6 | 4.278 | 290.079 | 291.0872 | [M+H]+ | 76.23 | −0.29 |

| Epicatechin | C15H14O6 | 3.662 | 290.079 | 291.0874 | [M+H]+ | 75.5 | 2.33 |

| Naringenin | C15H12O5 | 6.826 | 272.0685 | 273.0765 | [M+H]+ | 78 | 1.47 |

| Eriodictyol | C15H12O6 | 5.610 | 288.0634 | 289.0720 | [M+H]+ | 80.94 | 4.81 |

| Secoisolariciresinol | C20H26O6 | 8.889 | 362.1729 | 361.1660 | [M-H]− | 92.5 | −4.34 |

| Piceatannol 3-O-glucoside | C20H20O8 | 0.399 | 406.1264 | 407.1327 | [M+H]+ | 88.1 | −0.30 |

| Benzaldehyde | C7H6O | 0.932 | 106.0419 | 107.0490 | [M+H]+ | 81.74 | −0.08 |

| Mandelic acid | C8H8O3 | 3.563 | 152.0473 | 153.0558 | [M+H]+ | 78.18 | 8.04 |

| Sample | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WK | W1 | W2 | W5 | W10 | ||

| ACE EC50 [mg/mL] | PBS EtOH TRW | 9.680 ± 1.065 aA 3.859 ± 0.367 aB 0.280 ± 0.013 aC | 6.137 ± 1.04 bA 2.160 ± 0.162 bB 0.268 ± 0.020 aC | 4.239 ± 0.210 cA 0.907 ± 0.050 cB 0.254 ± 0.014 abC | 4.064 ± 0.244 cA 0.879 ± 0.057 cB 0.239 ± 0.015 bC | 3.615 ± 0.398 cA 0.803 ± 0.100 cB 0.226 ± 0.027 bC |

| Lipase EC50 [mg/mL] | PBS EtOH TRW | 12.711 ± 1.398 aA 4.388 ± 0.219 aB 1.780 ± 0.178 aC | 8.571 ± 0.717 bA 3.846 ± 0.153 bB 0.586 ± 0.053 bC | 7.227 ± 0.578 cA 3.452 ± 0.138 cB 0.310 ± 0.019 cC | 7.169 ± 0.476 dA 3.100 ± 0.123 dB 0.247 ± 0.022 cC | 5.948 ± 0.686 dA 3.014 ± 0.180 dB 0.232 ± 0.024 cC |

| LOX EC50 [mg/mL] | PBS EtOH TRW | nd. nd. 0.288 ± 0.011 a | nd. 2.655 ± 0.273 aA 0.273 ± 0.009 aB | nd. 2.673 ± 0.299 aA 0.267 ± 0.0089 aB | nd. 2.762 ± 0.428 aA 0.265 ± 0.013 aB | nd. 2.042 ± 0.397 bA 0.234 ± 0.008 bB |

| COX-2 EC50 [mg/mL] | PBS EtOH TRW | nd. 2.639 ± 0.157 aA 1.154 ± 0.111 aB | nd. 2.029 ± 0.107 bA 0.720 ± 0.062 bB | nd. 2.029 ± 0.141 bA 0.461 ± 0.026 cB | nd. 1.649 ± 0.079 cA 0.411 ± 0.014 cB | nd. 1.388 ± 0.018 dA 0.339 ± 0.011 dB |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Szymanowska, U.; Karaś, M.; Oliveira, I.; Afonso, S.; Chilczuk, B.; Lisiecka, K. The Health-Promoting Potential of Wafers Enriched with Almond Peel. Molecules 2026, 31, 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010129

Szymanowska U, Karaś M, Oliveira I, Afonso S, Chilczuk B, Lisiecka K. The Health-Promoting Potential of Wafers Enriched with Almond Peel. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):129. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010129

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzymanowska, Urszula, Monika Karaś, Ivo Oliveira, Sílvia Afonso, Barbara Chilczuk, and Katarzyna Lisiecka. 2026. "The Health-Promoting Potential of Wafers Enriched with Almond Peel" Molecules 31, no. 1: 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010129

APA StyleSzymanowska, U., Karaś, M., Oliveira, I., Afonso, S., Chilczuk, B., & Lisiecka, K. (2026). The Health-Promoting Potential of Wafers Enriched with Almond Peel. Molecules, 31(1), 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010129