On the Mechanism of Random Handedness Generation in the Reactions of Heterocyclic Aldehydes with Diallylboronates

Abstract

1. Introduction

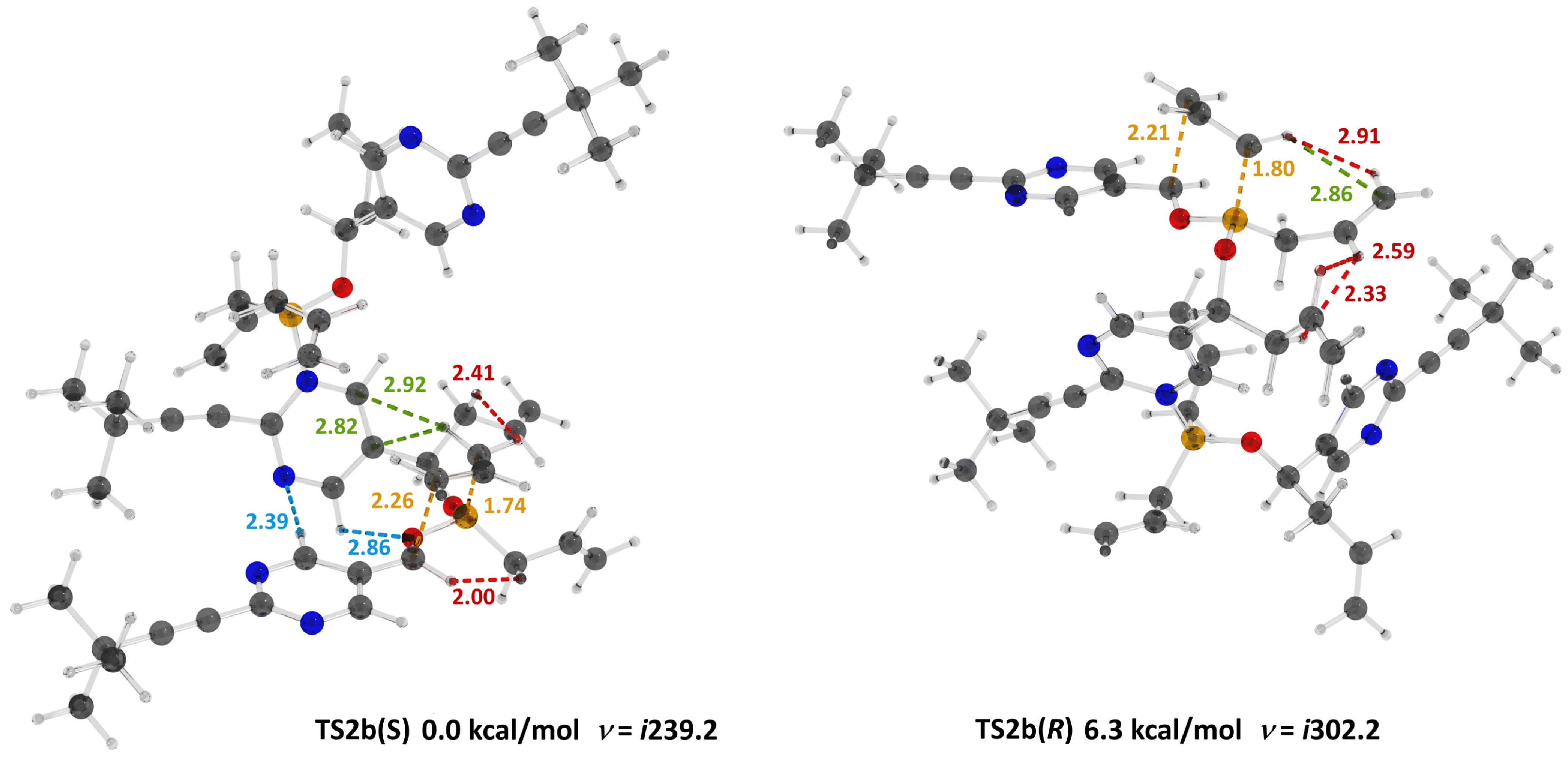

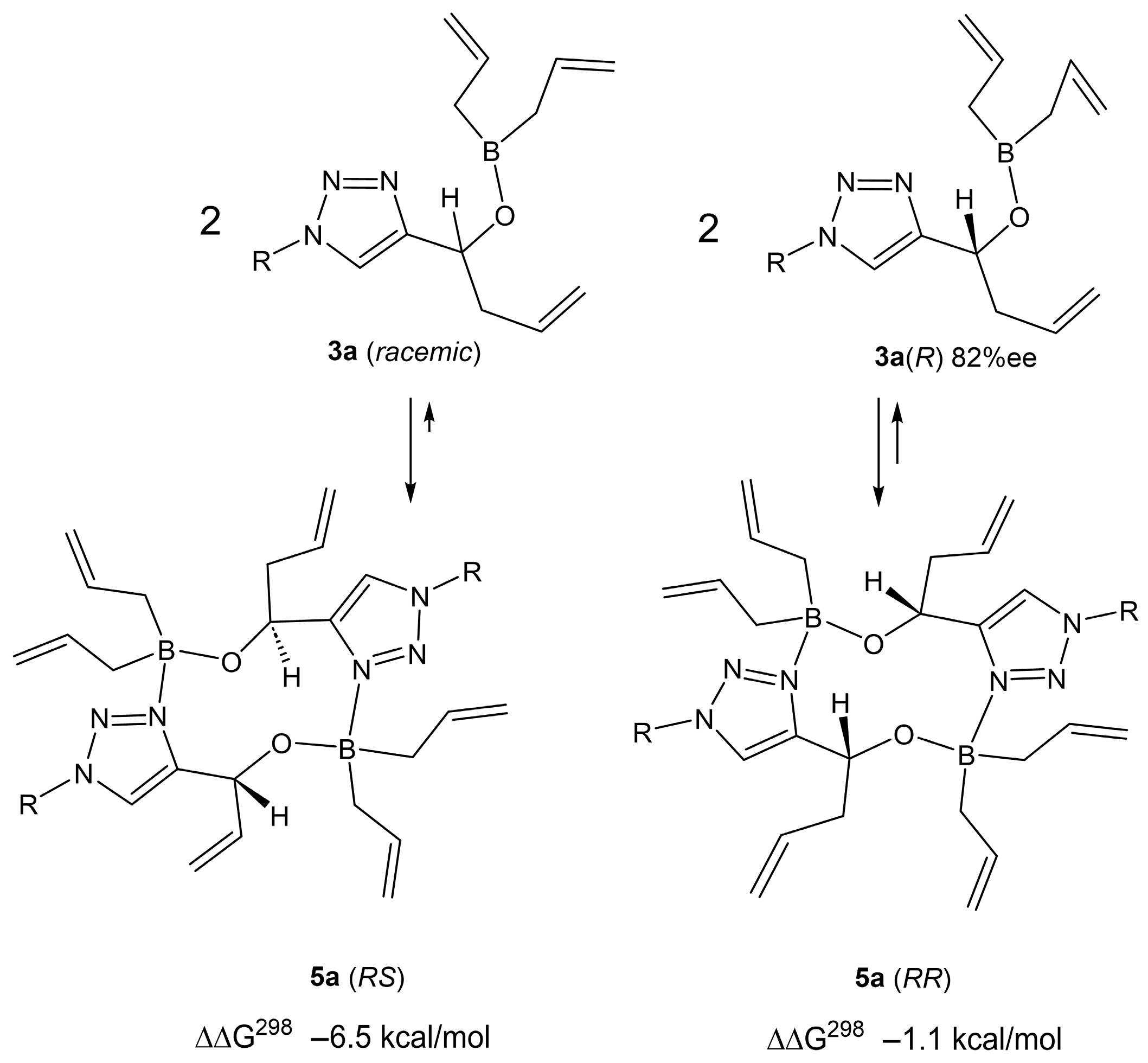

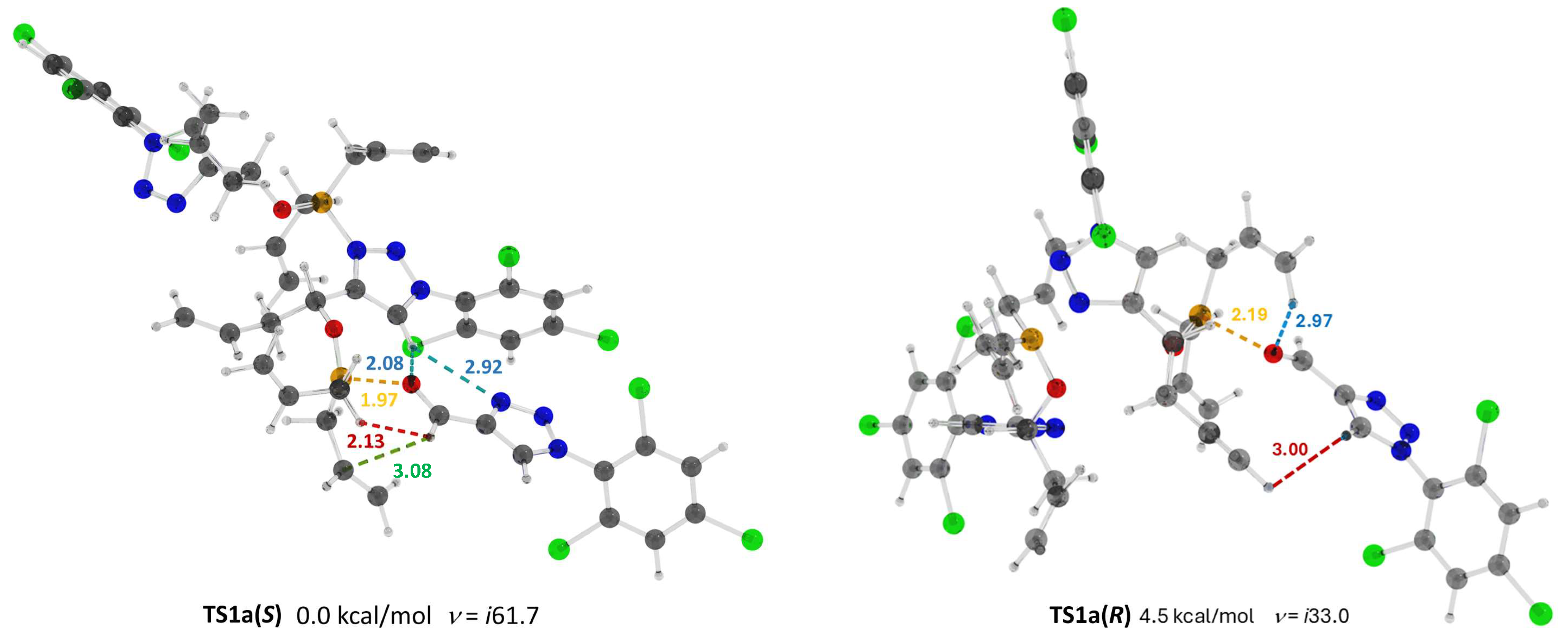

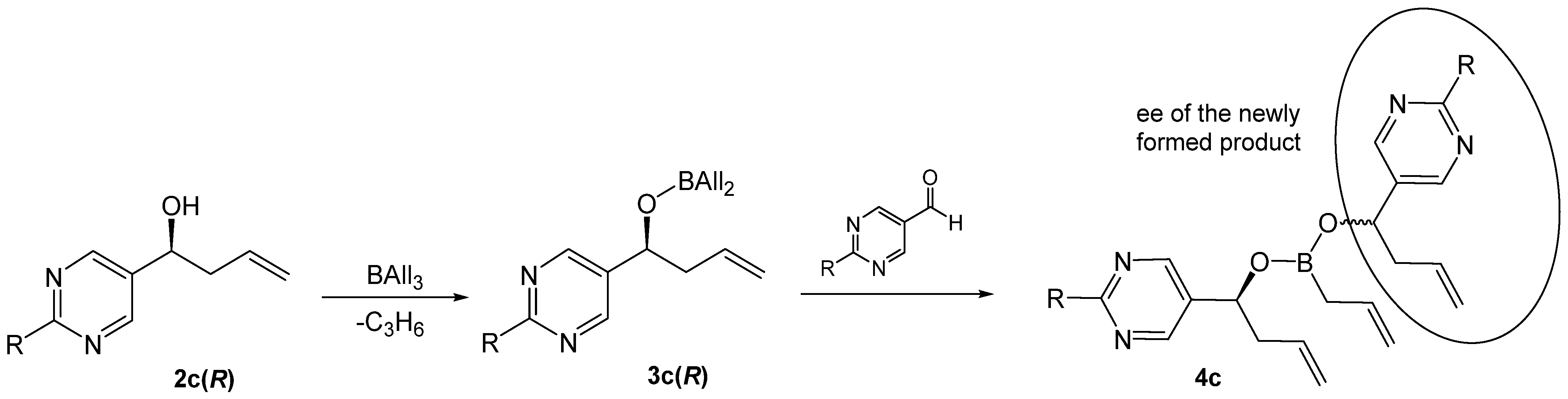

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Details

4.2. Chemical Synthesis

4.3. Computationall Details

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Senkuttuvan, N.; Komarasamy, B.; Krishnamoorthy, R.; Sarkar, S.; Dhanasekarand, S.; Anaikutti, P. The significance of chirality in contemporary drug discovery-a mini review. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 33429–33448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabré, A.; Verdaguer, X.; Riera, A. Recent advances in the enantioselective synthesis of chiral amines via transition metal-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation. Chem. Rev. 2021, 122, 269–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, J.; Zhang, W.; Muhammad, U.; Li, W.; Xie, Y. Recent advances in asymmetric synthesis of chiral benzoheterocycles via Earth-abundant metal catalysis. Org. Chem. Front. 2024, 11, 6534–6557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soai, K.; Niwa, S.; Hori, H. Asymmetric Self-Catalytic Reaction. Self-Production of Chiral 1-(3-Pyridyl)Alkanols as Chiral Self-Catalysts in the Enantioselective Addition of Dialkylzinc Reagents to Pyridine-3-Carbaldehyde. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1990, 14, 982–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soai, K.; Niwa, S. Enantioselective addition of organozinc reagents to aldehydes. Chem. Rev. 1992, 92, 833–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soai, K.; Shibata, T.; Morioka, H.; Choji, K. Asymmetric autocatalysis and amplification of enantiomeric excess of a chiral molecule. Nature 1995, 378, 767–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soai, K.; Kawasaki, T.; Matsumoto, A. Absolute Asymmetric Synthesis in the Soai Reaction. In Asymmetric Autocatalysis: The Soai Reaction; Soai, K., Kawasaki, T., Matsumoto, A., Eds.; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 2022; Volume 43, pp. 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Soai, K.; Hori, H.; Niwa, S. Enantioselective addition of dialkylzincs to pyridinecarbaldehyde in the presence of chiral aminoalcohols: Asymmetric synthesis of pyridylalkyl alcohols. Heterocycles 1989, 29, 2065–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, T.; Morioka, H.; Hayase, T.; Choji, K.; Soai, K. Highly enantioselective catalytic asymmetric automultiplication of chiral pyrimidyl alcohol. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 471–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, T.; Yonekubo, S.; Soai, K. Practically perfect asymmetric autocatalysis with (2-Alkynyl-5-pyrimidyl) alkanols. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 659–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, I.; Urabe, H.; Ishiguro, S.; Shibata, T.; Soai, K. Amplification of chirality from extremely low to greater than 99.5% ee by asymmetric autocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 315–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, I.; Yanagi, T.; Soai, K. Highly enantioselective asymmetric autocatalysis of 2-alkenyl-and 2-vinyl-5-pyrimidyl alkanols with significant amplification of enantiomeric excess. Chirality 2002, 14, 166–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soai, K.; Shibata, T.; Kowata, Y. Kokai Tokkyo Koho. JP 9-268179, 18 April 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Soai, K.; Sato, I.; Shibata, T.; Komiya, S.; Hayashi, M.; Matsueda, Y.; Imamura, H.; Hayase, T.; Morioka, H.; Tabira, H.; et al. Asymmetric synthesis of pyrimidyl alkanol without adding chiral substances by the addition of diisopropylzinc to pyrimidine-5-carbaldehyde in conjunction with asymmetric autocatalysis. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2003, 14, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, D.A.; Vo, L.K. A Few Molecules Can Control the Enantiomeric Outcome. Evidence Supporting Absolute Asymmetric Synthesis Using the Soai Asymmetric Autocatalysis. Org. Lett. 2003, 23, 4337–4339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gridnev, I.D.; Serafimov, J.M.; Quiney, H.; Brown, J.M. Reflections on spontaneous asymmetric synthesis by amplifying autocatalysis. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2003, 1, 3811–3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikhailov, O.A.; Saigitbatalova, E.S.H.; Latypova, L.Z.; Gerasimova, D.P.; Lodochnikova, O.A.; Kurbangalieva, A.R.; Gridnev, I.D. Allylboration of Azolic Aldehydes. Enantioselective Synthesis of Azolic Homoallylic Alcohols. Reconsideration of the Mechanism of Enantioselection. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2024, 73, 2910–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhailov, O.A.; Gurskii, M.E.; Kurbangalieva, A.R.; Gridnev, I.D. Exploring Border Conditions for Spontaneous Emergence of Chirality in Allylboration of 1,2,3-Triazolic Aldehydes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhailov, O.A.; Saigitbatalova, E.S.H.; Latypova, L.Z.; Kurbangalieva, A.R.; Gridnev, I.D. Reaction of Triazolic Aldehydes with Diisopropyl Zinc: Chirality Dissipation versus Amplification. Symmetry 2023, 15, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soai, K.; Osanai, S.; Kadowaki, K.; Yonekubo, S.; Shibata, T.; Sato, I. Asymmetric Autocatalysis Induced by Left- and Right-Handed Quartz. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 11235–11236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murygin, I.I.; Gridnev, I.D. Chiral surface control in the Soai reaction: A DFT study of α-quartz-induced enantioselective autocatalysis. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2025, 27, 21406–21409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharkin, L.I.; Stanko, V.I. Simple synthesis of triallylboron and some of its conversions. Russ. Chem. Bull. 1960, 9, 1774–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, H.C.; Jadhav, P.K. Asymmetric carbon-carbon bond formation via. beta.-allyldiisopinocampheylborane. Simple synthesis of secondary homoallylic alcohols with excellent enantiomeric purities. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983, 105, 2092–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athavale, S.V.; Simon, A.; Houk, K.N.; Denmark, S.E. Structural Contributions to Autocatalysis and Asymmetric Amplification in the Soai Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 18387–18406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, J.-D.; Head-Gordon, M. Long-Range Corrected Hybrid Density Functionals with Damped Atom–Atom Dispersion Corrections. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 10, 6615–6620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Petersson, G.A.; et al. Gaussian 09, rev. D.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Becke, A.D. Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior. Phys. Rev. A 1988, 38, 3098–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditchfield, R.; Hehre, W.J.; Pople, J.A. Self-Consistent Molecular-Orbital Methods. IX. An Extended Gaussian-Type Basis for Molecular-Orbital Studies of Organic Molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1971, 54, 724–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hehre, W.J.; Ditchfield, R.; Pople, J.A. Self-Consistent Molecular Orbital Methods. XII. Further Extensions of Gaussian-Type Basis Sets for Use in Molecular Orbital Studies of Organic Molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1972, 56, 2257–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariharan, P.C.; Pople, J.A. The influence of polarization functions on molecular orbital hydrogenation energies. Theor. Chim. Acta 1973, 28, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francl, M.M.; Pietro, W.J.; Hehre, W.J.; Binkley, J.S.; Gordon, M.S.; DeFrees, D.J.; Pople, J.A. Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XXIII. A polarization-type basis set for second-row elements. J. Chem. Phys. 1982, 77, 3654–3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, M.S.; Binkley, J.S.; Pople, J.A.; Pietro, W.J.; Hehre, W.J. Self-consistent molecular-orbital methods. Small split-valence basis sets for second-row elements. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982, 104, 2797–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassolov, V.A.; Pople, J.A.; Ratner, M.A.; Windus, T.L. 6-31G * basis set for atoms K through Zn. J. Chem. Phys. 1998, 109, 1223–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marenich, A.V.; Cramer, C.J.; Truhlar, D.G. Universal Solvation Model Based on Solute Electron Density and on Continuum Model of the Solvent Defined by the Bulk Dielectric Constant and Atomic Surface Tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 6378–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mikhailov, O.; Gridnev, I.D. On the Mechanism of Random Handedness Generation in the Reactions of Heterocyclic Aldehydes with Diallylboronates. Molecules 2026, 31, 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010128

Mikhailov O, Gridnev ID. On the Mechanism of Random Handedness Generation in the Reactions of Heterocyclic Aldehydes with Diallylboronates. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):128. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010128

Chicago/Turabian StyleMikhailov, Oleg, and Ilya D. Gridnev. 2026. "On the Mechanism of Random Handedness Generation in the Reactions of Heterocyclic Aldehydes with Diallylboronates" Molecules 31, no. 1: 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010128

APA StyleMikhailov, O., & Gridnev, I. D. (2026). On the Mechanism of Random Handedness Generation in the Reactions of Heterocyclic Aldehydes with Diallylboronates. Molecules, 31(1), 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010128