Functional and Rheological Properties of Gluten-Free Flour Blends from Brown Eragrostis tef (Zucc.) Trotter and Glycine max (L.) Merr

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Absorptive Characteristics

2.2. Correlation Between Particle Size and Functional Properties

2.3. Pasting Properties

2.4. Rheology

2.5. Texture Profile Analysis in Different Solvents

2.5.1. Distilled Water

2.5.2. Silver Nitrate (AgNO3)

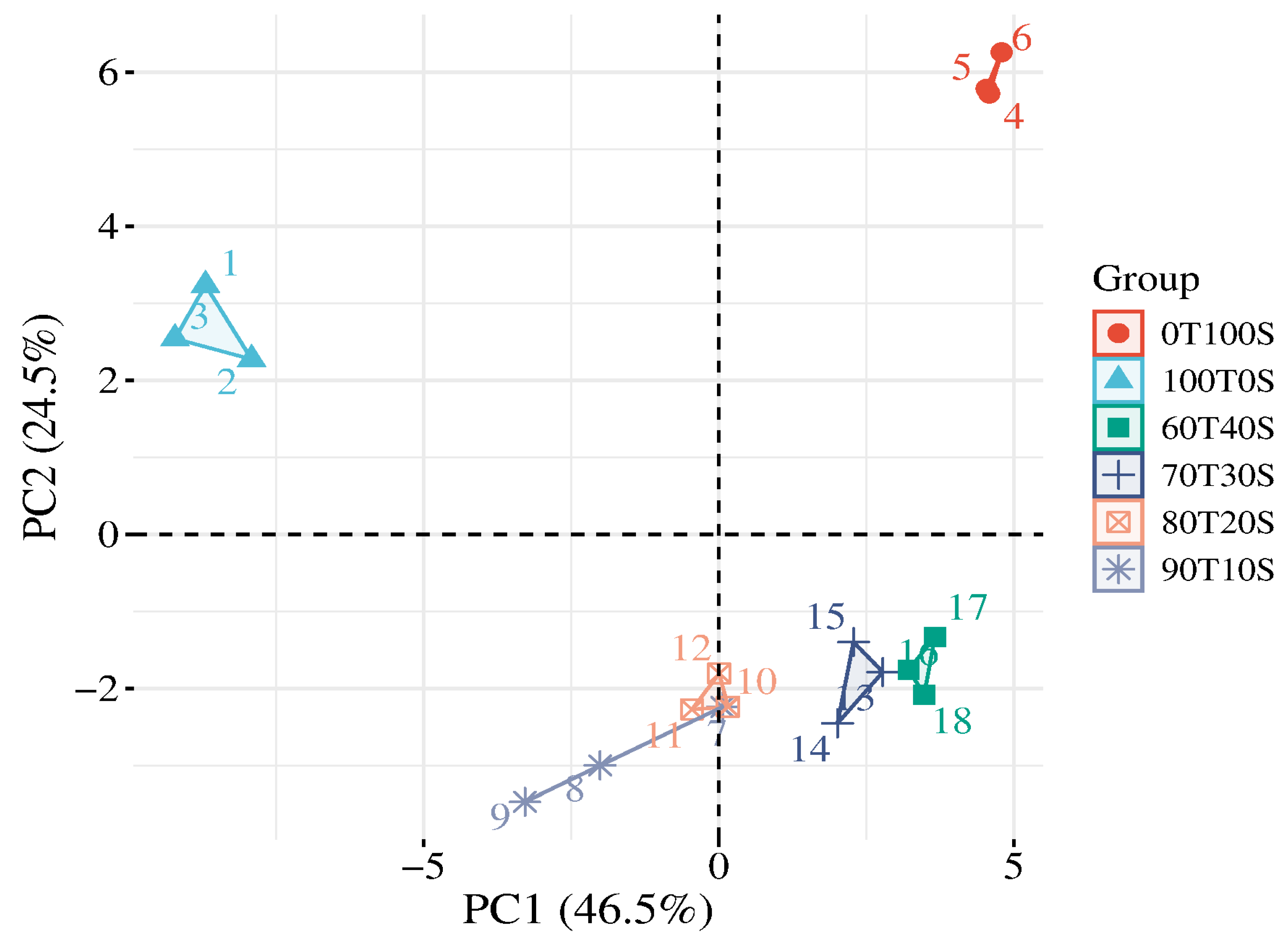

2.6. Principal Component Analysis

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Gluten-Free Flour Preparation and Formulation

3.2. Flour Blending

3.3. Techno-Functional Properties of Blends

3.3.1. Water Holding Capacity (WHC)

3.3.2. Water Absorption Capacity (WAC), Oil Absorption Capacity (OAC), Hydrophilic–Lipophilic Index (HLI)

3.3.3. Water Absorption Index (WAI), Water Solubility Index (WSI), Swelling Power SP

3.4. Pasting Properties: Viscoamylographic Tests (RVA)

3.5. Rheological Analysis: Viscoelastic Behaviour: Oscillatory Tests

3.6. Texture Gel Analysis

3.7. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kutlu, G.; Özsüer, E.; Madenlioğlu, M.; Eroğlu, G.; Akbaş, İ. Teff: Its applicability in various food uses and potential as a key component in gluten-free food formulations—An overview of existing literature research. Eur. Food Sci. Eng. 2024, 5, 30–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culetu, A.; Susman, I.E.; Duta, D.E.; Belc, N. Nutritional and functional properties of gluten-free flours. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neji, C.; Semwal, J.; Máthé, E.; Sipos, P. Dough rheological properties and macronutrient bioavailability of cereal products fortified through legume proteins. Processes 2023, 11, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerarathna, A.; Wansapala, M.A.J. Compatibility of Whole Wheat-Based Composite Flour in the Development of Functional Foods. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2024, 62, 425–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abebe, B.S.; Aprodu, I.; Istrati, D.I.; Vizireanu, C. Nutritional Characteristics, Health-Related Properties, and Food Application of Teff (Eragrostis tef): An Overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villanueva, M.; Abebe, W.; Pérez-Quirce, S.; Ronda, F. Impact of the Variety of Tef [Eragrostis tef (Zucc.) Trotter] on Physical, Sensorial and Nutritional Properties of Gluten-Free Breads. Foods 2022, 11, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yisak, H.; Redi-Abshiro, M.; Chandravanshi, B.S.; Yaya, E.E. Total phenolics and antioxidant capacity of the white and brown teff [Eragrostic tef (Zuccagni) Trotter] varieties cultivated in different parts of Ethiopia. Bull. Chem. Soc. Ethiop. 2022, 36, 749–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akansha, C.; Chauhan, E. Teff millet: Nutritional, phytochemical and antioxidant potential. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2020, 11, 6005–6009. [Google Scholar]

- Shuluwa, E.-M.; Famuwagun, A.A.; Ahure, D.; Ukeyima, M.; Aluko, R.E.; Gbenyi, D.I.; Girgih, A.T. Amino acid profiles and in vitro antioxidant properties of cereal-legume flour blends. J. Food Bioact. 2021, 14, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Singh, J.P.; Kaur, A.; Singh, N. Phenolic composition and antioxidant potential of grain legume seeds: A review. Food Res. Int. 2017, 101, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavanya, A.; Rani, V.; Sangwan, V.; Godara, P. Optimization for Incorporating Teff, Sorghum and Soybean Blends in Traditional Food Preparations. IAHRW Int. J. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2020, 2022, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Awol, S.J.; Kidane, S.W.; Bultosa, G. The effect of extrusion condition and blend proportion on the physicochemical and sensory attributes of teff-soybean composite flour gluten free extrudates. Meas. Food 2024, 13, 100120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatzy, L.M.; Kern, K.; Muranyi, I.S.; Alpers, T.; Becker, T.; Gola, S.; Schweiggert-Weisz, U. Thermal, rheological, and microstructural characterization of composite gels from fava bean protein and pea starch. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 172, 111883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roccia, P.; Ribotta, P.D.; Pérez, G.T.; León, A.E. Influence of soy protein on rheological properties and water retention capacity of wheat gluten. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2009, 42, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, S.M.S.; Harasym, J.; Sánchez-García, J.; Kelaidi, M.; Betoret, E.; Betoret, N. Suitability of almond bagasse powder as a wheat flour substitute in biscuit formulation. J. Food Qual. 2024, 2024, 7152554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jima, B.R.; Abera, A.A.; Kuyu, C.G. Effect of particle size on compositional, functional, pasting, and rheological properties of teff [Eragrostis teff (zucc.) Trotter] flour. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 100986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balet, S.; Guelpa, A.; Fox, G.; Manley, M. Rapid visco analyser (RVA) as a tool for measuring starch-related physiochemical properties in cereals: A review. Food Anal. Methods 2019, 12, 2344–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekuria, S.A.; Kinyuru, J.N.; Mokua, B.K.; Tenagashaw, M.W. Nutritional quality and safety of complementary foods developed from blends of staple grains and honey bee larvae (Apis mellifera). Int. J. Food Sci. 2021, 2021, 5581585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijarotimi, O.S.; Fatiregun, M.R.; Oluwajuyitan, T.D. Nutritional, antioxidant and organoleptic properties of therapeutic-complementary-food formulated from locally available food materials for severe acute malnutrition management. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2022, 46, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwurafor, E.; Umego, E.; Uzodinma, E.; Samuel, E. Chemical, functional, pasting and sensory properties of sorghum-maize-mungbean malt complementary food. Pak. J. Nutr. 2017, 16, 826–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenn, D.; Lukow, O.M.; Humphreys, G.; Fields, P.G.; Boye, J.I. Wheat-Legume Composite Flour Quality. Int. J. Food Prop. 2010, 13, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olamiti, G.R.; Shonisani, E. Impact of Composite Flour on Nutritional, Bioactive and Sensory Characteristics of Pastry Foods: A Review. Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. 2024, 12, 1018–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, F.A.; Esin, U.D. Effect of cowpea and coconut pomace flour blend on the proximate composition, antioxidant and pasting properties of maize flour. Food Sci. Appl. Biotechnol. 2023, 6, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, S.; Zheng, Y.; Li, M.; Feng, X.; Yang, X. Effects of heat-moisture extrusion on the structure and functional properties of protein-fortified whole potato flour. Food Chem. X 2024, 24, 102048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikegwu, O.; Okechukwu, P.; Ekumankana, E. Physico-chemical and pasting characteristics of flour and starch from achi Brachystegia eurycoma seed. J. Food Technol. 2010, 8, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.; Meng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; McClements, D.J.; Li, G.; Jiang, L.; Wen, J.; Jin, Z.; Ji, H. Enhancement of soy protein functionality by conjugation or complexation with polysaccharides or polyphenols: A review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walle, H.; Moges, D. Optimization of cereal-legume blend ratio to enhance the nutritional quality and functional property of complementary food. Ethiop. J. Sci. Technol. 2017, 10, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wei, T.; Wei, Z.; Yuan, F.; Gao, Y. Influence of soybean soluble polysaccharides and beet pectin on the physicochemical properties of lactoferrin-coated orange oil emulsion. Food Hydrocoll. 2015, 44, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boka, A.L.; Tolesa, G.N.; Abera, S. Effects of variety and particles size on functional properties of Teff (Eragrostis tef (Zucc.) Trotter) flour. Cogent Food Agric. 2023, 9, 2242635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alija, D.; Olędzki, R.; Daniela Nikolovska, N.; Wojciechowicz-Budzisz, A.; Xhabiri, G.; Pejcz, E.; Alija, E.; Harasym, J. The Addition of Pumpkin Flour Impacts the Functional and Bioactive Properties of Soft Wheat Composite Flour Blends. Foods 2025, 14, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.; Bourouis, I.; Sun, M.; Cao, J.; Liu, P.; Sun, R.; Chen, C.; Li, H.; Liu, X. Physicochemical properties and microstructural behaviors of rice starch/soy proteins mixtures at different proportions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 209, 2061–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Ke, F.; Zhou, H.; Wang, J.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, F.; Duan, Y.; et al. The correlation of starch composition, physicochemical and structural properties of different sorghum grains. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1515022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyango, C.; Mutungi, C.; Unbehend, G.; Lindhauer, M.G. Rheological and textural properties of sorghum-based formulations modified with variable amounts of native or pregelatinised cassava starch. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 43, 1197–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Tao, J.; Wang, Q.; Ge, J.; Li, J.; Gao, F.; Gao, S.; Yang, Q.; Feng, B.; Gao, J. A comparative study: Functional, thermal and digestive properties of cereal and leguminous proteins in ten crop varieties. LWT 2023, 187, 115288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Khoddami, A.; Copeland, L.; Atwell, B.J.; Roberts, T.H. Optimal silver nitrate concentration to inhibit α-amylase activity during pasting of rice flour. Starch-Stärke 2020, 73, 2000150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.N.; Modupalli, N.; Rahman, M.M. Fabrication of Antibacterial and Functional Films from Starch-Polyvinylpyrrolidone Composite Using Plasma Treatment and Silver Nanoparticles. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 37419–37431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, H. Effect of cation valence on the retrogradation, gelatinization and gel characteristics of maize starch. Food Chem. 2024, 450, 139307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemneh, S.T.; Emire, S.A.; Hitzmann, B.; Zettel, V. Comparative Study of Chemical Composition, Pasting, Thermal and Functional properties of Teff (Eragrostis tef) Flours Grown in Ethiopia and South Africa. Int. J. Food Prop. 2022, 25, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, X.; Zhu, L.; Xiang, M.; Zhao, S.; Cheng, Z.; Qiao, D.; Zhang, B. Insight of soy protein isolate to decrease the gel properties corn starch based binary system: Rheological and structural investigation. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 160, 110750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wu, X.; Zhang, J.; Yan, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, B. Effects of adding proteins from different sources during heat-moisture treatment on corn starch structure, physicochemical and in vitro digestibility. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 273, 133079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreechithra, T.V.; Sakhare, S.D. Development of novel process for production of high-protein soybean semolina and its functionality. Food Res. Int. 2025, 203, 115865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymońska, J.; Molenda, M.; Wieczorek, J. Study of quantitative interactions of potato and corn starch granules with ions in diluted solutions of heavy metal salts. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 134, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, Y.; Jiao, R.; Wu, Y.; Xu, F.; Li, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Mao, L. Physicochemical and functional properties of the protein-starch interaction in Chinese yam. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 1499–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Xiao, X. The effect of protein-starch interaction on the structure and properties of starch, and its application in flour products. Foods 2025, 14, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, G.; Awika, J.M. Effect of protein-starch interactions on starch retrogradation and implications for food product quality. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2023, 22, 2081–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.-S.; Yang, Y.; Chen, F.-L.; Fan, J.; Wang, B.; Fu, Y.; Bian, X.; Yu, D.-H.; Wu, N.; Shi, Y.-G.; et al. Soybean protein isolate-rice starch interactions during the simulated gluten-free rice bread making process. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 57, 2093–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladeji, O.S.; Said, F.M.; Daud, N.F.S.; Adam, F. Advancing gluten-free noodles development through sustainable and nutritional interventions. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 101209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yolcu, Z.; Demircan, E.; Mertdinç, Z.; Aydar, E.F.; Ozcelik, B. Alternative Plant-Based Gluten-Free Sourdough Pastry Snack Production by Using Beetroot and Legumes: Characterization of Physical and Sensorial Attributes. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 19451–19460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M.; Johansson, D.; Ström, A.; Ryden, J.; Nilsson, K.; Karlsson, J.; Moriana, R.; Langton, M. Effect of starch and fibre on faba bean protein gel characteristics. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 131, 107741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.L.S.; Chen, D.C.D.; Xu, J.X.J. The effect of partially substituted lupin, soybean, and navy bean flours on wheat bread quality. Food Nutr. Sci. 2018, 9, 840–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, T.; Sun, M.; Cao, S.; Hao, J.; Rao, H.; Zhao, D.; Liu, X. Enhancing water retention and mechanisms of citrus and soya bean dietary fibres in pre-fermented frozen dough. Food Chem. X 2024, 22, 101269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, J.; Zhang, W.; Yang, X.; Ma, P. Controlling pea starch gelatinization behavior and rheological properties by modulating granule structure change with pea protein isolate. Food Chem. X 2025, 25, 102218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Kumar, K.; Singh, L.; Sharanagat, V.S.; Nema, P.K.; Mishra, V.; Bhushan, B. Gluten-free grains: Importance, processing and its effect on quality of gluten-free products. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 1988–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnet, A.-F.; Laleg, K.; Michon, C.; Micard, V. Legume enriched cereal products: A generic approach derived from material science to predict their structuring by the process and their final properties. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 86, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojňanská, T.; Musilová, J.; Vollmannová, A. Effects of adding legume flours on the rheological and breadmaking properties of dough. Foods 2021, 10, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AACC. International Method 66-20.01: Determination of Granularity of Semolina and Farina by Sieving. In Approved Methods of the AACC, 11th ed.; AACC International: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- AACC. AACC Method 76-21.02: Pasting Properties of Starch Using the Rapid Visco Analyser. In Approved Methods of Analysis, 11th ed.; AACC International: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, N.; Gasparre, N.; Rosell, C.M. Expanding the application of germinated wheat by examining the impact of varying alpha-amylase levels from grain to bread. J. Cereal Sci. 2024, 120, 104059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Chen, M.; Huang, X.; Zhang, G.; Zeng, L.; Zhang, G.; Wu, S.; Wang, Y. SRplot: A free online platform for data visualization and graphing. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0294236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Samples | WHC | WAC | WAI | SP | HLI | WSI | OAC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g H2O/g DM | g H2O/100 g DM | g H2O/g DM | |||||

| 0T100S | 5.54 ± 0.55 b | 2.63 ± 0.20 b | 3.15 ± 0.32 a | 5.27 ± 0.27 a | 1.39 ± 0.14 a | 40.18 ± 3.73 e | 1.89 ± 0.05 d |

| 100T0S | 4.60 ± 0.23 a | 2.85 ± 0.19 b | 5.62 ± 0.38 c | 6.18 ± 0.40 b | 1.56 ± 0.21 a | 9.05 ± 0.63 a | 1.84 ± 0.14 d |

| 90T10S | 4.72 ± 0.16 a | 0.69 ± 0.08 a | 4.73 ± 0.16 b | 5.26 ± 0.18 a | 32.07 ± 5.98 c | 10.01 ± 0.40 ba | 0.02 ± 0.00 a |

| 80T20S | 4.93 ± 0.44 ab | 0.77 ± 0.02 a | 4.54 ± 0.11 b | 5.26 ± 0.15 a | 2.80 ± 0.41 a | 13.68 ± 1.16 cb | 0.28 ± 0.04 c |

| 70T30S | 4.69 ± 0.28 a | 0.59 ± 0.01 a | 4.56 ± 0.11 b | 5.39 ± 0.16 a | 2.98 ± 0.29 a | 15.47 ± 0.83 cd | 0.20 ± 0.02 bc |

| 60T40S | 4.73 ± 0.66 a | 0.72 ± 0.04 a | 4.50 ± 0.06 b | 5.61 ± 0.06 ab | 21.42 ± 2.16 b | 19.93 ± 0.23 d | 0.04 ± 0.01 ab |

| 100 | 100T0S | 90T10S | 80T20S | 70T30S | 60T40S | 0T100S | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % >355 μm | 58.67 ± 3.53 a | 52.49 ± 5.65 a | 74.82 ± 2.78 b | 80.43 ± 1.33 b | 88.26 ± 2.21 c | 94.81 ± 5.19 c | ||||

| % <355 μm–250 μm> | 35.42 ± 3.51 e | 39.43 ± 3.77 e | 21.15 ± 3.19 d | 16.32 ± 1.01 c | 9.49 ± 2.12 b | 2.12 ± 1.34 a | ||||

| % <150 μm | 3.71 ± 0.43 bc | 8.54 ± 2.19 d | 4.34 ± 0.47 c | 3.54 ± 0.42 bc | 2.57 ± 0.21 b | 0.67 ± 0.64 a | ||||

| WHC | WAC | OAC | HLI | WAI | WSI | SP | >0.355 μm | 0.255 μm–0.355 μm | <0.25 μm | |

| <0.2 μm | −0.57 | −0.47 | −0.53 | 0.67 | 0.52 | −0.74 | −0.14 | −0.88 * | 0.84 * | 1.00 |

| <0.25 μm–0.355 μm> | −0.64 | 0.00 | −0.08 | 0.34 | 0.78 | −0.81 * | 0.35 | −1.00 * | 1.00 | |

| >0.355 μm | 0.64 | 0.07 | 0.15 | −0.40 | −0.76 | 0.82 * | −0.28 | 1.00 | ||

| SP | −0.50 | 0.54 | 0.46 | −0.22 | 0.70 | −0.37 | 1.00 | |||

| WSI | 0.92 * | 0.38 | 0.45 | −0.29 | −0.92 * | 1.00 | ||||

| WAI | −0.91 * | −0.06 | −0.15 | 0.12 | 1.00 | |||||

| HLI | −0.33 | −0.52 | −0.61 | 1.00 | ||||||

| OAC | 0.48 | 0.99 * | 1.00 | |||||||

| WAC | 0.40 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| WHC | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Samples | Solvent | PV mPa·s | TV mPa·s | BV mPa·s | FV mPa·s | SBV mPa·s | PT s | Ptemp °C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0T100S | AgNo3 | 169 ± 15 d | 109 ± 13 d | 60 ± 90 d | 234 ± 21 d | 125 ± 10 d | 7.0 ± 0 a | 0 ± 0 c |

| D. Water | 257 ± 25 c | 116 ± 90 c | 142 ± 16 c | 611 ± 41 c | 496 ± 32 c | 7.0 ± 0 a | 0 ± 0 c | |

| 100T0S | AgNo3 | 1839 ± 30 b | 1068 ± 4 b | 771 ± 28 b | 2019 ± 14 b | 951 ± 18 b | 5.4 ± 0.10 b | 76.2 ± 0.5 a |

| D. Water | 12,198 ± 133 a | 2473 ± 23 a | 9725 ± 13 a | 6611 ± 36 a | 4137 ± 33 a | 7.5 ± 0.31 a | 68.9 ± 0.3 b | |

| 90T10S | AgNo3 | 1714 ± 505 b | 994 ± 19 b | 720 ± 28 b | 1817 ± 35 b | 822 ± 15 b | 5.48 ± 0.18 b | 75.85 ± 0.35 a |

| D. Water | 644 ± 60 c | 455 ± 40 c | 190 ± 30 c | 1037 ± 11 c | 583 ± 70 c | 5.31 ± 0.03 b | 71.00 ± 0 b | |

| 80T20S | AgNo3 | 1248 ± 63 b | 805 ± 33 b | 443 ± 28 b | 1403 ± 64 b | 598 ± 32 b | 5.31 ± 0.03 b | 76.63 ± 0.05 a |

| D. Water | 331 ± 80 c | 263 ± 50 c | 68 ± 30 c | 616 ± 14 c | 353 ± 80 c | 5.00 ± 0.00 b | 70.33 ± 0.58 b | |

| 70T30S | AgNo3 | 638 ± 70 d | 476 ± 20 d | 163 ± 70 d | 797 ± 60 d | 321 ± 60 d | 5.22 ± 0.04 b | 77.98 ± 0.48 a |

| D. Water | 218 ± 20 e | 190 ± 15 e | 28 ± 40 e | 447 ± 33 e | 256 ± 16 e | 4.73 ± 0.06 b | 68.33 ± 0.58 b | |

| 60T40S | AgNo3 | 462 ± 46 e | 368 ± 43 e | 94 ± 40 e | 575 ± 43 e | 207 ± 30 e | 5.07 ± 0.07 b | 82.90 ± 5.5 a |

| D. Water | 129 ± 90 f | 125 ± 70 f | 3 ± 30 f | 284 ± 13 f | 159 ± 90 f | 4.67 ± 0.12 b | 68.67 ± 1.15 b |

| Sample | Treatment | G′ [Pa] | a | G″ [Pa] | B | Tan δ | c | G′ = G″ [Pa] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0T100S | AgNO3 | 48.96 ± 7.93 ab | 0.01 ± 0.00 a | 9.99 ±2.09 abc | 0.18 ±0.02 a | 0.20 ± 0.01 c | 0.18 ± 0.02 ef | 2.23 ± 1.00 a |

| D. Water | 132.71 ± 33.66 abcd | 0.15 ± 0.01 cde | 32.54 ± 7.62 e | 0.24 ±0.02 b | 0.25 ± 0.01 d | 0.10 ± 0.01 a | 29.02 ± 6.47 a | |

| 100T0S | AgNO3 | 195.27 ± 58.83 cd | 0.12 ± 0.02 c | 25.22 ±3.91 de | 0.26 ± 0.02 bc | 0.14 ± 0.02 b | 0.14 ± 0.01 bcde | 216.85 ± 48.75 c |

| D. Water | 1947.98 ± 129.94 e | 0.07 ± 0.01 b | 142.85 ± 15.99 f | 0.18 ±0.01 a | 0.07 ± 0.01 a | 0.11 ± 0.01 ab | 1789.56 ± 158.40 d | |

| 90T10S | AgNO3 | 231.21 ± 93.95 d | 0.11 ± 0.03 c | 29.86 ± 7.92 e | 0.24 ± 0.05 bc | 0.14 ± 0.03 b | 0.13 ± 0.02 abc | 212.08 ± 89.03 bc |

| D. Water | 103.83 ± 12.59 abc | 0.14 ± 0.01 cde | 16.59 ± 2.37 bcd | 0.28 ± 0.01 cd | 0.16 ± 0.01 b | 0.14 ± 0.02 bcde | 62.85 ± 6.79 a | |

| 80T20S | AgNO3 | 142.25 ± 19.67 bcd | 0.12 ± 0.01 cd | 21.25 ± 3.62 cde | 0.26 ± 0.01 bc | 0.15 ± 0.01 b | 0.14 ± 0.02 abcd | 110.10 ± 16.09 ab |

| D. Water | 67.12 ± 10.94 ab | 0.13 ± 0.02 cd | 10.44 ± 1.44 abc | 0.30 ± 0.01 de | 0.16 ± 0.01 b | 0.17 ± 0.02 de | 33.55 ± 2.84 a | |

| 70T30S | AgNO3 | 59.21 ± 6.19 ab | 0.16 ± 0.01 e | 12.12 ± 1.23 abc | 0.30 ± 0.01 de | 0.21 ± 0.01 c | 0.13 ± 0.01 abc | 33.67 ± 2.53 a |

| D. Water | 57.66 ± 3.35 ab | 0.14 ± 0.02 cde | 9.20 ± 0.46 ab | 0.30 ± 0.01 de | 0.16 ± 0.01 b | 0.16 ± 0.02 cde | 27.17 ± 2.62 a | |

| 60T40S | AgNO3 | 45.84 ± 6.17 ab | 0.15 ± 0.02 de | 8.94 ± 1.23 ab | 0.31 ± 0.01 de | 0.20 ± 0.01 c | 0.16 ± 0.03 cde | 21.51 ± 1.36 a |

| D. Water | 36.47 ± 4.60 a | 0.12 ± 0.03 cd | 5.27 ± 0.80 a | 0.33 ± 0.01 e | 0.14 ± 0.01 b | 0.21 ± 0.03 f | 15.70 ± 1.73 a |

| Sample | Hardness N | Cohesiveness | Springiness | Chewiness N | Resilience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0T100S | 0.02 ± 0.00 a | 0.64 ± 0.15 b | 0.57 ± 0.56 ab | 0.01 ± 0.01 a | 2.22 ± 1.23 c |

| 100T0S | 7.60 ± 0.78 d | 0.46 ± 0.11 a | 1.39 ± 0.61 c | 4.87 ± 2.84 d | 0.61 ± 0.04 a |

| 90T10S | 0.49 ± 0.17 b | 0.83 ± 0.40 bc | 1.21 ± 0.67 c | 0.57 ± 0.61 b | 0.57 ± 0.07 a |

| 80T20S | 0.11 ± 0.11 ab | 1.50 ± 1.47 cd | 1.60 ± 1.24 c | 0.47 ± 0.70 b | 0.60 ± 0.22 ab |

| 70T30S | 0.03 ± 0.01 a | 3.58 ± 4.71 d | 2.13 ± 2.43 c | 0.53 ± 0.77 b | 1.69 ± 1.07 bc |

| 60T40S | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Sample | Hardness N | Cohesiveness | Springiness | Chewiness N | Resilience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0T100S | 1.82 ± 0.19 d | 0.69 ± 0.02 d | 1.07 ± 0.08 b | 1.35 ± 0.16 d | 1.18 ± 0.72 c |

| 100T0S | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 90T10S | 1.54 ± 0.47 c | 0.65 ± 0.02 c | 1.09 ± 0.14 b | 1.07 ± 0.26 c | 0.94 ± 0.61 c |

| 80T20S | 0.91 ± 0.08 b | 0.86 ± 0.28 d | 1.38 ± 0.36 c | 1.11 ± 0.61 c | 0.69 ± 0.09 b |

| 70T30S | 0.19 ± 0.04 a | 0.56 ± 0.38 b | 0.64 ± 0.67 ab | 0.09 ± 0.10 b | 0.44 ± 0.09 a |

| 60T40S | 0.06 ± 0.01 a | 0.36 ± 0.10 a | 0.18 ± 0.15 a | 0.00 ± 0.00 a | 0.50 ± 0.18 ab |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mekuria, S.A.; Marcinkowski, D.; Harasym, J. Functional and Rheological Properties of Gluten-Free Flour Blends from Brown Eragrostis tef (Zucc.) Trotter and Glycine max (L.) Merr. Molecules 2025, 30, 4817. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244817

Mekuria SA, Marcinkowski D, Harasym J. Functional and Rheological Properties of Gluten-Free Flour Blends from Brown Eragrostis tef (Zucc.) Trotter and Glycine max (L.) Merr. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4817. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244817

Chicago/Turabian StyleMekuria, Shewangzaw Addisu, Damian Marcinkowski, and Joanna Harasym. 2025. "Functional and Rheological Properties of Gluten-Free Flour Blends from Brown Eragrostis tef (Zucc.) Trotter and Glycine max (L.) Merr" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4817. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244817

APA StyleMekuria, S. A., Marcinkowski, D., & Harasym, J. (2025). Functional and Rheological Properties of Gluten-Free Flour Blends from Brown Eragrostis tef (Zucc.) Trotter and Glycine max (L.) Merr. Molecules, 30(24), 4817. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244817