Flux Enhancement in Hybrid Pervaporation Membranes Filled with Mixed Magnetic Chromites ZnCr2Se4, CdCr2Se4 and CuCr2Se4

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

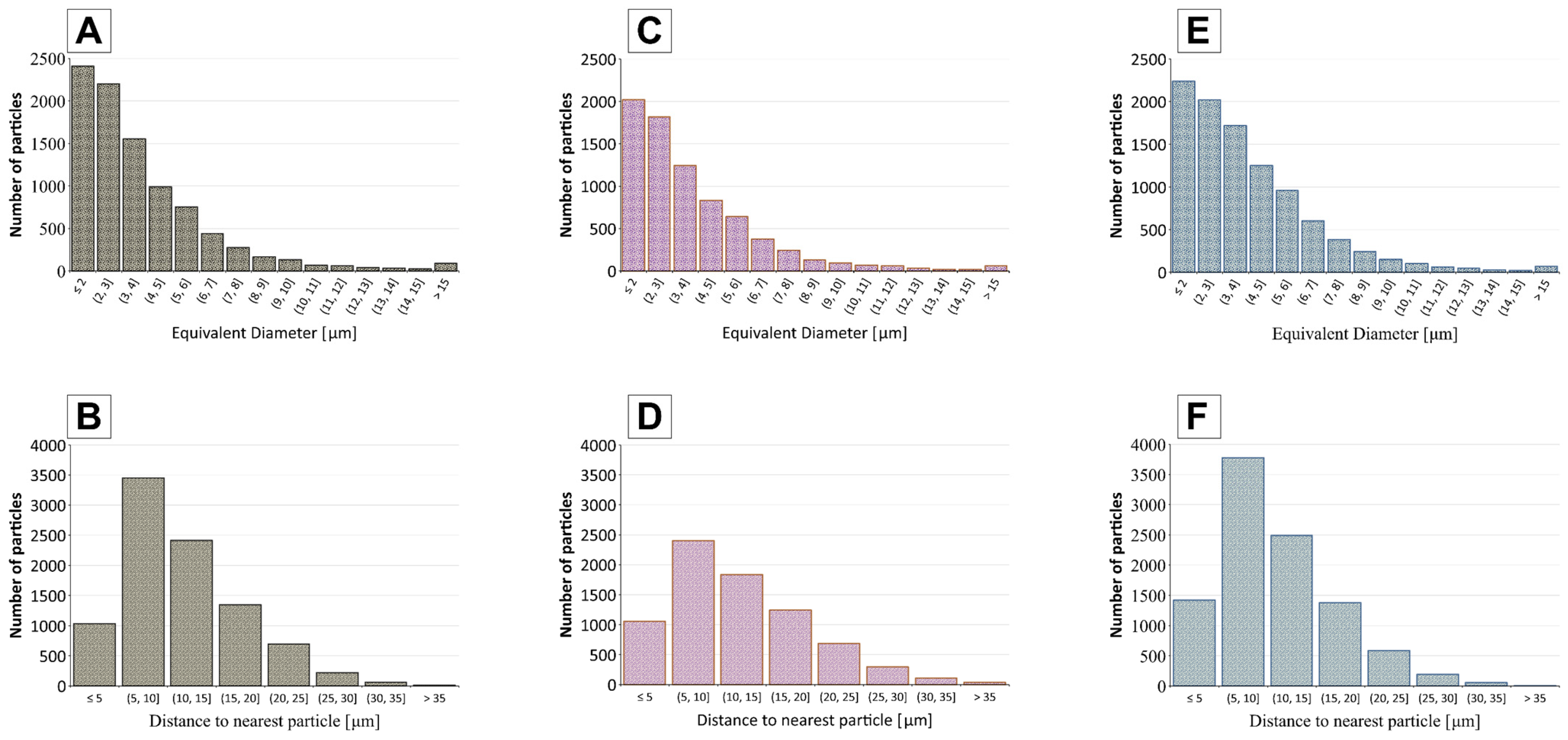

2.1. Morphological Analysis

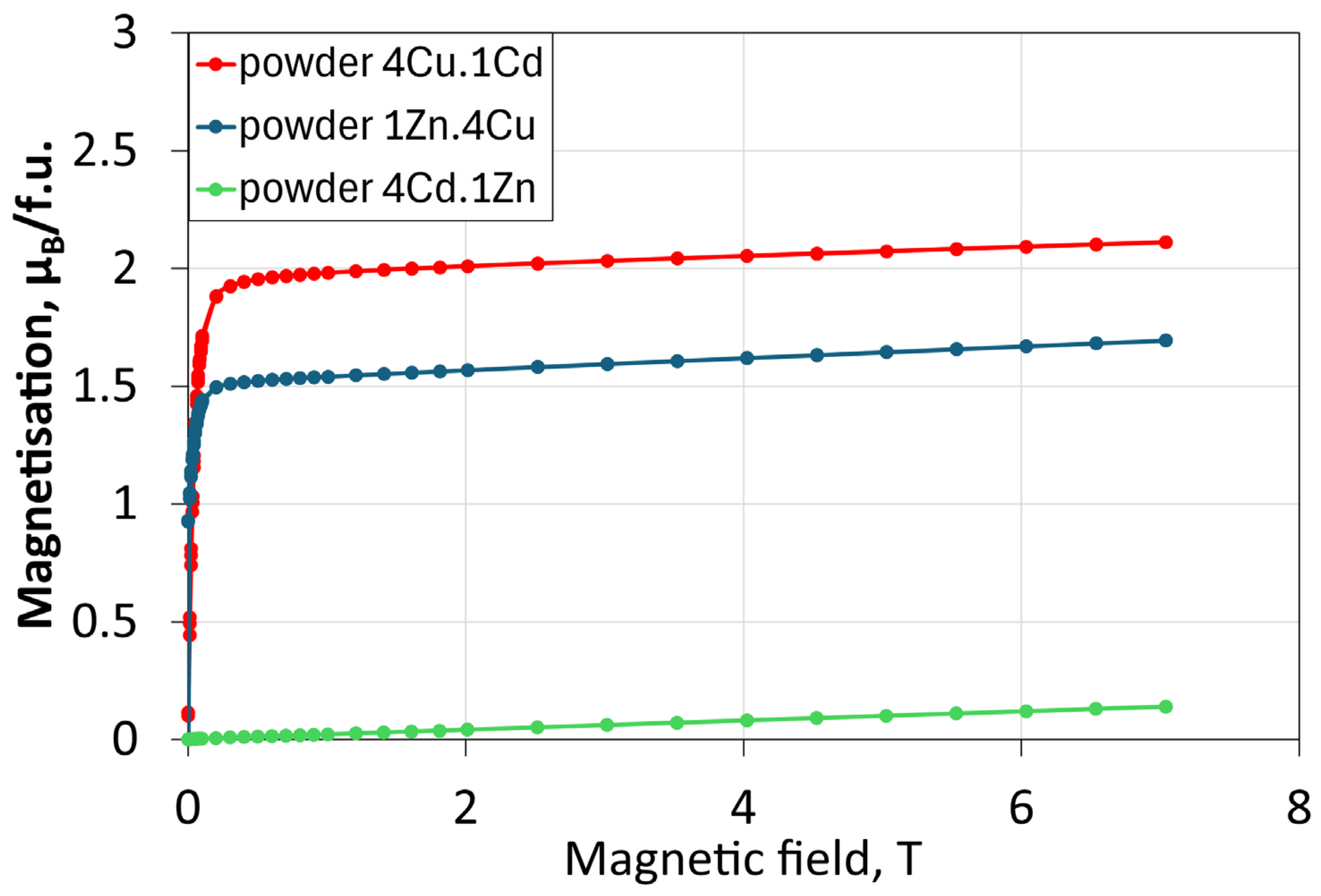

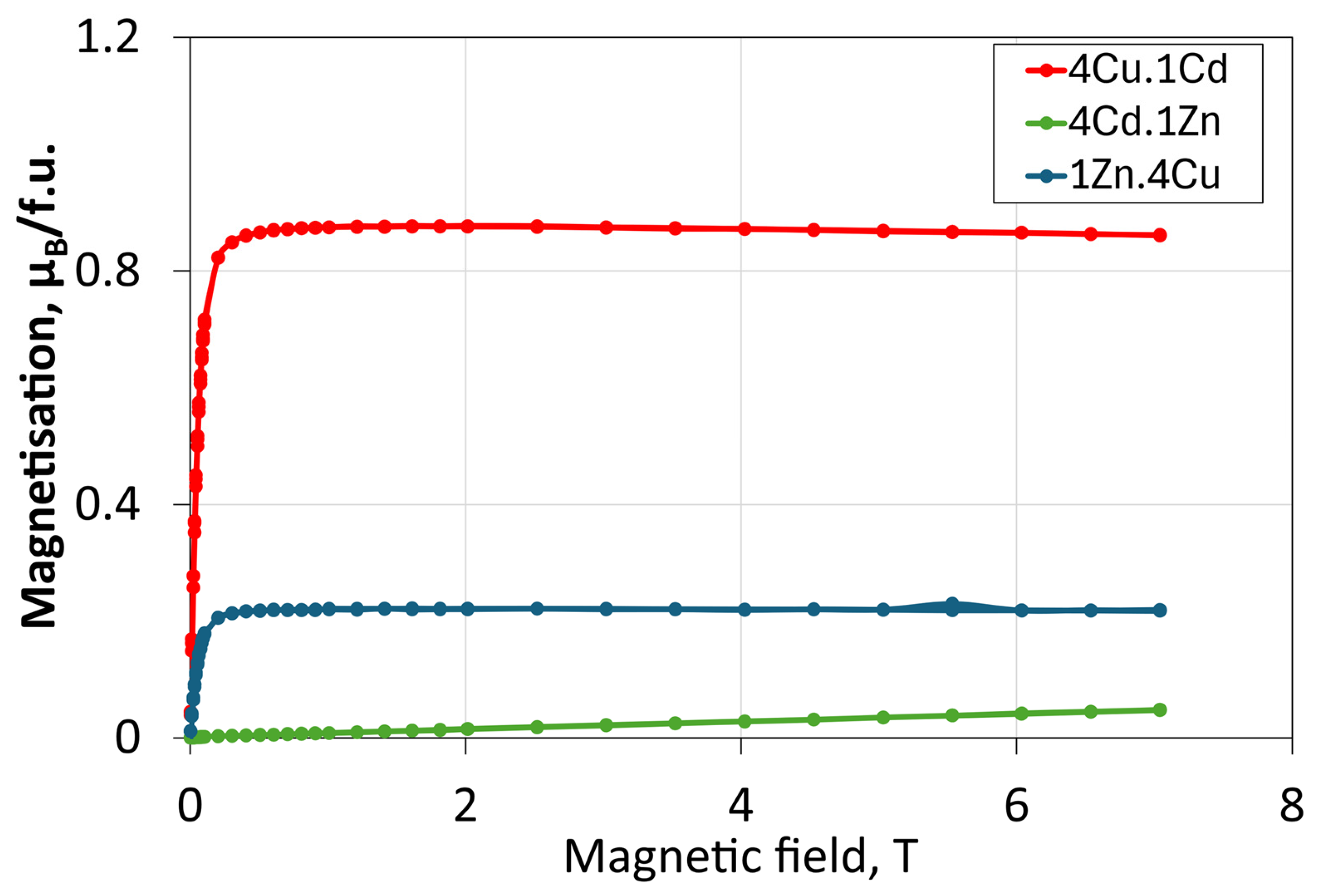

2.2. Magnetic Characteristics

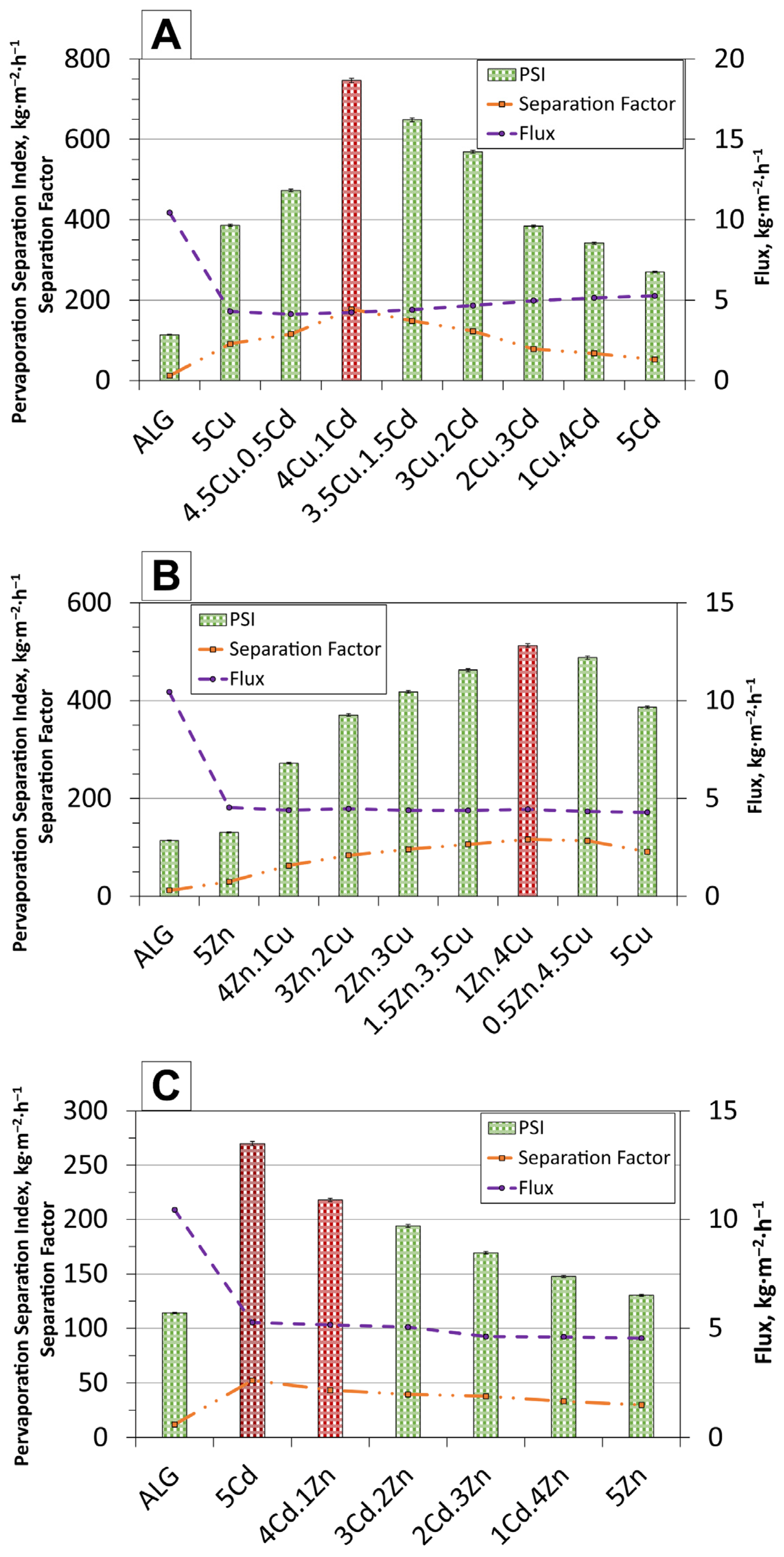

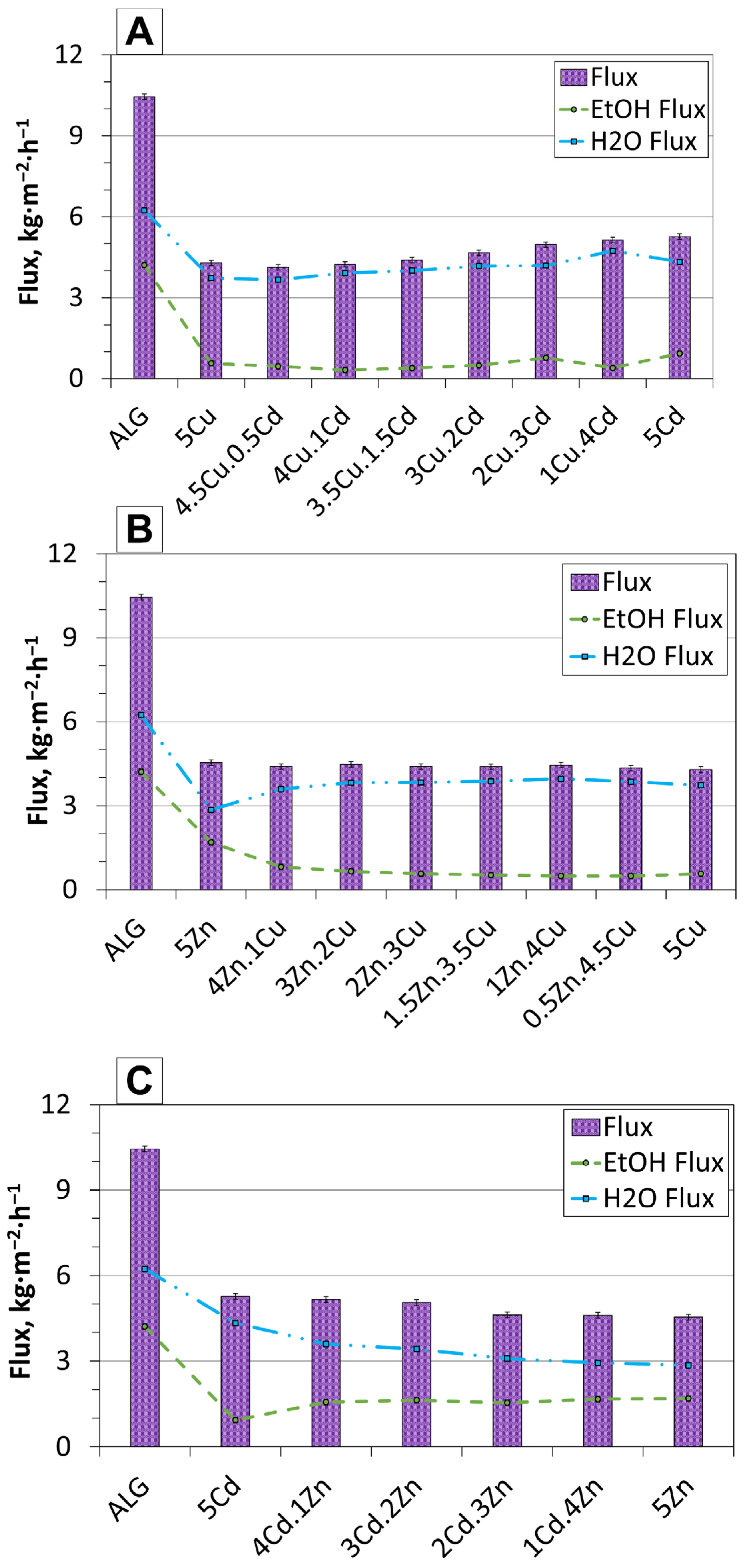

2.3. Pervaporation Performance

2.4. Comparison of Pervaporation Performance with the Literature

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Preparation of Selenide Chromites

3.3. Membrane Preparation

3.4. Physicochemical Characterisation

3.5. Pervaporation Process

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Balat, M.; Balat, H.; Öz, C. Progress in Bioethanol Processing. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2008, 34, 551–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, S.; Kumar, D.; Singh, B.; Sachan, P.K. Biofuels and Their Sources of Production: A Review on Cleaner Sustainable Alternative against Conventional Fuel, in the Framework of the Food and Energy Nexus. Energy Nexus 2021, 4, 100036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyman, C. Handbook on Bioethanol: Production and Utilization, 1st ed.; Wyman, C.E., Ed.; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-0-203-75245-6. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard, C.P.; Anderson, J.E.; Wallington, T.J. Ethanol and Air Quality: Influence of Fuel Ethanol Content on Emissions and Fuel Economy of Flexible Fuel Vehicles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 861–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, E.; Niculescu, V.-C. Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) as Environmental Pollutants: Occurrence and Mitigation Using Nanomaterials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S.; Karri, R.R.; Tavakkoli Yaraki, M.; Koduru, J.R. Processes and Separation Technologies for the Production of Fuel-Grade Bioethanol: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 2873–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliev, S. A Comparison of Ethanol, Methanol, and Butanol Blending with Gasoline and Its Effect on Engine Performance and Emissions Using Engine Simulation. Processes 2021, 9, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tye, Y.Y.; Lee, K.T.; Wan Abdullah, W.N.; Leh, C.P. Second-Generation Bioethanol as a Sustainable Energy Source in Malaysia Transportation Sector: Status, Potential and Future Prospects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 4521–4536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betiku, E.; Ishola, M.M. (Eds.) Bioethanol: A Green Energy Substitute for Fossil Fuels; Green Energy and Technology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; ISBN 978-3-031-36541-6. [Google Scholar]

- Robotto, A.; Barbero, S.; Bracco, P.; Cremonini, R.; Ravina, M.; Brizio, E. Improving Air Quality Standards in Europe: Comparative Analysis of Regional Differences, with a Focus on Northern Italy. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.T.; Lee, K.T.; Mohamed, A.R. Role of Energy Policy in Renewable Energy Accomplishment: The Case of Second-Generation Bioethanol. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 3360–3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imad, M.; Castro-Muñoz, R. Ongoing Progress on Pervaporation Membranes for Ethanol Separation. Membranes 2023, 13, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X.; Ge, R.; Gao, Z.; Gao, T.; Wang, L.; Li, J. PVA-Based MMMs for Ethanol Dehydration via Pervaporation: A Comparison Study between Graphene and Graphene Oxide. Separations 2022, 9, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmy, K.S.; Lal, D.; Nair, A.; Babu, A.; Das, H.; Govind, N.; Dmitrenko, M.; Kuzminova, A.; Korniak, A.; Penkova, A.; et al. Pervaporation as a Successful Tool in the Treatment of Industrial Liquid Mixtures. Polymers 2022, 14, 1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.-J.; Kim, S.-J.; Lee, K.; Foster, R.I. A Short Review on Hydrophobic Pervaporative Inorganic Membranes for Ethanol/Water Separation Applications. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2022, 39, 2263–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghbanzadeh, M.; Rana, D.; Lan, C.Q.; Matsuura, T. Effects of Inorganic Nano-Additives on Properties and Performance of Polymeric Membranes in Water Treatment. Sep. Purif. Rev. 2016, 45, 141–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Xie, Z.; Cran, M.; Wu, C.; Gray, S. Dimensional Nanofillers in Mixed Matrix Membranes for Pervaporation Separations: A Review. Membranes 2020, 10, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubski, Ł.; Jendrzejewska, I.; Chrobak, A.; Gołombek, K.; Dudek, G. Advanced Magnetic Membranes with Chromite Fillers: Role of Structure and Magnetism in Ethanol Pervaporation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 378, 134796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.-C.; Chen, X.-L.; Yang, Z.-R. Electronic, Transport and Magnetic Properties of Cr-Based Chalcogenide Spinels. In Magnetic Spinels—Synthesis, Properties and Applications; Seehra, M.S., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2017; ISBN 978-953-51-2973-8. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, R.J.; Craig, J.R.; Gibbs, G.V. Systematics of the Spinel Structure Type. Phys. Chem. Miner. 1979, 4, 317–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotgering, F.K. Exchange Interactions in Semiconducting Chalcogenides with Normal Spinel Structure from an Experimental Point of View. J. Phys. Colloq. 1971, 32, C1-34–C1-38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadehnazari, A. Metal Oxide/Polymer Nanocomposites: A Review on Recent Advances in Fabrication and Applications. Polym.-Plast. Technol. Mater. 2023, 62, 655–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burts, K.S.; Plisko, T.V.; Prozorovich, V.G.; Melnikova, G.B.; Ivanets, A.I.; Bildyukevich, A.V. Modification of Thin Film Composite PVA/PAN Membranes for Pervaporation Using Aluminosilicate Nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubski, Ł.; Chrobak, A.; Gołombek, K.; Matus, K.; Krzywiecki, M.; Turczyn, R.; Dudek, G. Synergistic Effect of Tetranuclear Iron (III) Molecular Magnet and Magnetite towards High-Performance Ethanol Dehydration through an Alginate Membrane. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 320, 124222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubski, Ł.; Dudek, G.; Turczyn, R. Applicability of Composite Magnetic Membranes in Separation Processes of Gaseous and Liquid Mixtures—A Review. Membranes 2023, 13, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakubski, Ł.; Jakubska, J.; Chrobak, A.; Gołombek, K.; Dudek, G. Beneficent Impact of Mixed Molecular Magnet/Neodymium Powder for Facilitating Ethanol Dehydration in the Pervaporation Process. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 352, 128160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahdan, D.; Flaifel, M.H.; Ahmad, S.H.; Chen, R.S.; Razak, J.A. Enhanced Magnetic Nanoparticles Dispersion Effect on the Behaviour of Ultrasonication-Assisted Compounding Processing of PLA/LNR/NiZn Nanocomposites. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 15, 5988–6000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberbeck, D.; Wiekhorst, F.; Steinhoff, U.; Trahms, L. Aggregation Behaviour of Magnetic Nanoparticle Suspensions Investigated by Magnetorelaxometry. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2006, 18, S2829–S2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodenough, J.B. Tetrahedral-Site Copper in Chalcogenide Spinels. Solid State Commun. 1967, 5, 577–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotgering, F.K. Ferromagnetic Interactions in Sulphides, Selenides and Tellurides with Spinel Structure. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Magnetism, Nottingham, UK, 7–11 September 1964; pp. 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Baltzer, P.K.; Robbins, M.; Wojtowicz, P.J. Magnetic Properties of the Systems HgCr2S4–CdCr2S4 and ZnCr2Se4–CdCr2Se4. J. Appl. Phys. 1967, 38, 953–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotgering, F.K. Proceedings of the International Conference on Magnetism, Nottingham September 1964; Institute of Physics (IOP): London, UK; Bristol, UK, 1965; p. 533. [Google Scholar]

- Plumier, R. Étude Par Diffraction de Neutrons de l’antiferromagnétisme Hélicoïdal Du Spinelle ZnCr2Se4 En Présence d’un Champ Magnétique. J. Phys. 1966, 27, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemberger, J.; Von Nidda, H.-A.K.; Tsurkan, V.; Loidl, A. Large Magnetostriction and Negative Thermal Expansion in the Frustrated Antiferromagnet ZnCr2 Se4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 98, 147203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Pan, F.; Wang, M.; Cao, C.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, H.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Jiang, Z. Vertically Oriented Fe3O4 Nanoflakes within Hybrid Membranes for Efficient Water/Ethanol Separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 620, 118916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kwon, S.; Lee, S.; Khim, S.; Bhoi, D.; Park, C.B.; Kim, K.H. Interactions in the Bond-Frustrated Helimagnet ZnCr2Se4 Investigated by NMR. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 16627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, X.-F.; Deng, B.; Tang, B. Influences of Magnetic Field on Macroscopic Properties of Water. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 2012, 26, 1250069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachipudi, P.S.; Kittur, A.A.; Sajjan, A.M.; Kamble, R.R.; Kariduraganavar, M.Y. Solving the Trade-off Phenomenon in Separation of Water–Dioxan Mixtures by Pervaporation through Crosslinked Sodium–Alginate Membranes with Polystyrene Sulfonic Acid-Co-Maleic Acid. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2013, 94, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borys, P.; Pawelek, K.; Grzywna, Z.J. On the Magnetic Channels in Polymer Membranes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 17122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, G.; Turczyn, R.; Djurado, D. Collation Efficiency of Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) and Alginate Membranes with Iron-Based Magnetic Organic/Inorganic Fillers in Pervaporative Dehydration of Ethanol. Materials 2020, 13, 4152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, A.; Toth, A.J.; Fozer, D.; Haaz, E.; Valentínyi, N.; Nagy, T.; Keri, O.; Bakos, L.P.; Szilágyi, I.M.; Mizsey, P. Effect of Silver-Nanoparticles Generated in Poly (Vinyl Alcohol) Membranes on Ethanol Dehydration via Pervaporation. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2019, 27, 1595–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.B.; Kamcev, J.; Robeson, L.M.; Elimelech, M.; Freeman, B.D. Maximizing the Right Stuff: The Trade-off between Membrane Permeability and Selectivity. Science 2017, 356, eaab0530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, C.; Mao, H.; Wang, Y.-J.; Liu, W.-M.; Li, Z.-Z.; Xie, W.-W.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Z.-P. Boosting Pervaporation Performance of ZIF-L/PDMS Mixed Matrix Membranes by Surface Plasma Etching for Ethanol/Water Separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 318, 124025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Liu, M.; Sun, D.; Yue, D.; Ge, Y.; Li, F.; Shi, M.; Shi, Z. Asymmetric PDMS/PVDF Pervaporation Membrane for Separation of Ethanol/Water System. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, e202401075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, T.; Wang, Y.; Pan, F.; Zhao, J.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhao, J.; Jiang, Z. COF Membranes with Fast and Selective of Water-transport Channels for Efficient Ethanol Dehydration. AIChE J. 2025, 71, e18921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crank, J. The Mathematics of Diffusion, 2nd ed.; Oxford Science Publications; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1975; ISBN 978-0-19-853411-2. [Google Scholar]

- Wijmans, J.G.; Baker, R.W. The Solution-Diffusion Model: A Review. J. Membr. Sci. 1995, 107, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marszałek, J.; Kamiński, W. Concentration of Butanol-Ethanol-Acetone-Water Using Pervaporation. Proceeding ECOpole. 2012, 6, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Membrane | Parameter | Median (µm) | Mean (µm) | Standard Deviation (µm) | Interquartile Range (µm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4Cu.1Cd | Particle Size | 3.39 | 4.05 | 2.72 | 2.09–5.18 |

| 4Cu.1Cd | Neighbour Distance | 9.62 | 10.95 | 5.91 | 6.40–14.34 |

| 1Zn.4Cu | Particle Size | 3.01 | 3.82 | 2.84 | 1.95–4.74 |

| 1Zn.4Cu | Neighbour Distance | 10.21 | 11.53 | 6.13 | 6.82–15.07 |

| 4Cd.1Zn | Particle Size | 2.99 | 3.79 | 2.74 | 1.95–4.79 |

| 4Cd.1Zn | Neighbour Distance | 10.97 | 12.32 | 7.01 | 6.66–16.52 |

| Type of Membrane | 5Cu | 4.5Cu.0.5Cd | 4Cu.1Cd | 3.5Cu.1.5Cd | 3Cu.2Cd | 2Cu.3Cd | 1Cu.4Cd | 5Cd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flux value [kg·m−2·h−1] | 4.29 | 4.12 | 4.24 | 4.40 | 4.67 | 4.97 | 5.14 | 5.27 |

| Type of Membrane | ZnCr2Se4 | CdCr2Se4 | CuCr2Se4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALG | x | x | x |

| 5Cu | x | x | 5 wt.% |

| 4.5Cu.0.5Cd | x | 0.5 wt.% | 4.5 wt.% |

| 4Cu.1Cd | x | 1 wt.% | 4 wt.% |

| 3.5Cu.1.5Cd | x | 1.5 wt.% | 3.5 wt.% |

| 3Cu.2Cd | x | 2 wt.% | 3 wt.% |

| 2Cu.3Cd | x | 3 wt.% | 2 wt.% |

| 1Cu.4Cd | x | 4 wt.% | 1 wt.% |

| 5Cd | x | 5 wt.% | x |

| 4Cd.1Zn | 1 wt.% | 4 wt.% | x |

| 3Cd.2Zn | 2 wt.% | 3 wt.% | x |

| 2Cd.3Zn | 3 wt.% | 2 wt.% | x |

| 1Cd.4Zn | 4 wt.% | 1 wt.% | x |

| 5Zn | 5 wt.% | x | x |

| 4Zn.1Cu | 4 wt.% | x | 1 wt.% |

| 3Zn.2Cu | 3 wt.% | x | 2 wt.% |

| 2Zn.3Cu | 2 wt.% | x | 3 wt.% |

| 1.5Zn.3.5Cu | 1.5 wt.% | x | 3.5 wt.% |

| 1Zn.4Cu | 1 wt.% | x | 4 wt.% |

| 0.5Zn.4.5Cu | 0.5 wt.% | x | 4.5 wt.% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jakubski, Ł.; Jendrzejewska, I.; Chrobak, A.; Gołombek, K.; Dudek, G. Flux Enhancement in Hybrid Pervaporation Membranes Filled with Mixed Magnetic Chromites ZnCr2Se4, CdCr2Se4 and CuCr2Se4. Molecules 2025, 30, 4784. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244784

Jakubski Ł, Jendrzejewska I, Chrobak A, Gołombek K, Dudek G. Flux Enhancement in Hybrid Pervaporation Membranes Filled with Mixed Magnetic Chromites ZnCr2Se4, CdCr2Se4 and CuCr2Se4. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4784. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244784

Chicago/Turabian StyleJakubski, Łukasz, Izabela Jendrzejewska, Artur Chrobak, Klaudiusz Gołombek, and Gabriela Dudek. 2025. "Flux Enhancement in Hybrid Pervaporation Membranes Filled with Mixed Magnetic Chromites ZnCr2Se4, CdCr2Se4 and CuCr2Se4" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4784. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244784

APA StyleJakubski, Ł., Jendrzejewska, I., Chrobak, A., Gołombek, K., & Dudek, G. (2025). Flux Enhancement in Hybrid Pervaporation Membranes Filled with Mixed Magnetic Chromites ZnCr2Se4, CdCr2Se4 and CuCr2Se4. Molecules, 30(24), 4784. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244784