Label-Free Aptamer–Silver Nanoparticles Abs Biosensor for Detecting Hg2+

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

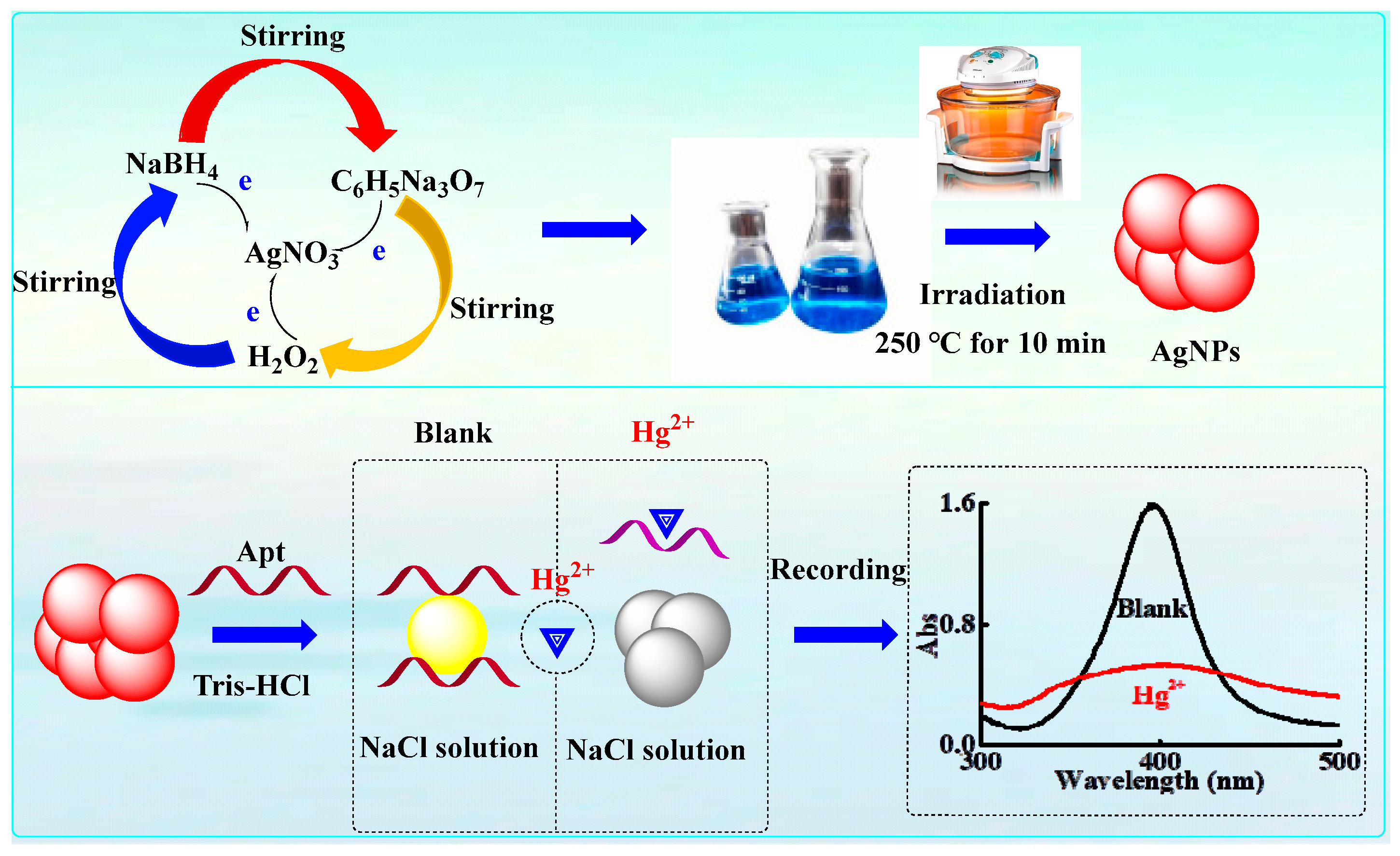

2.1. Analytical Principle

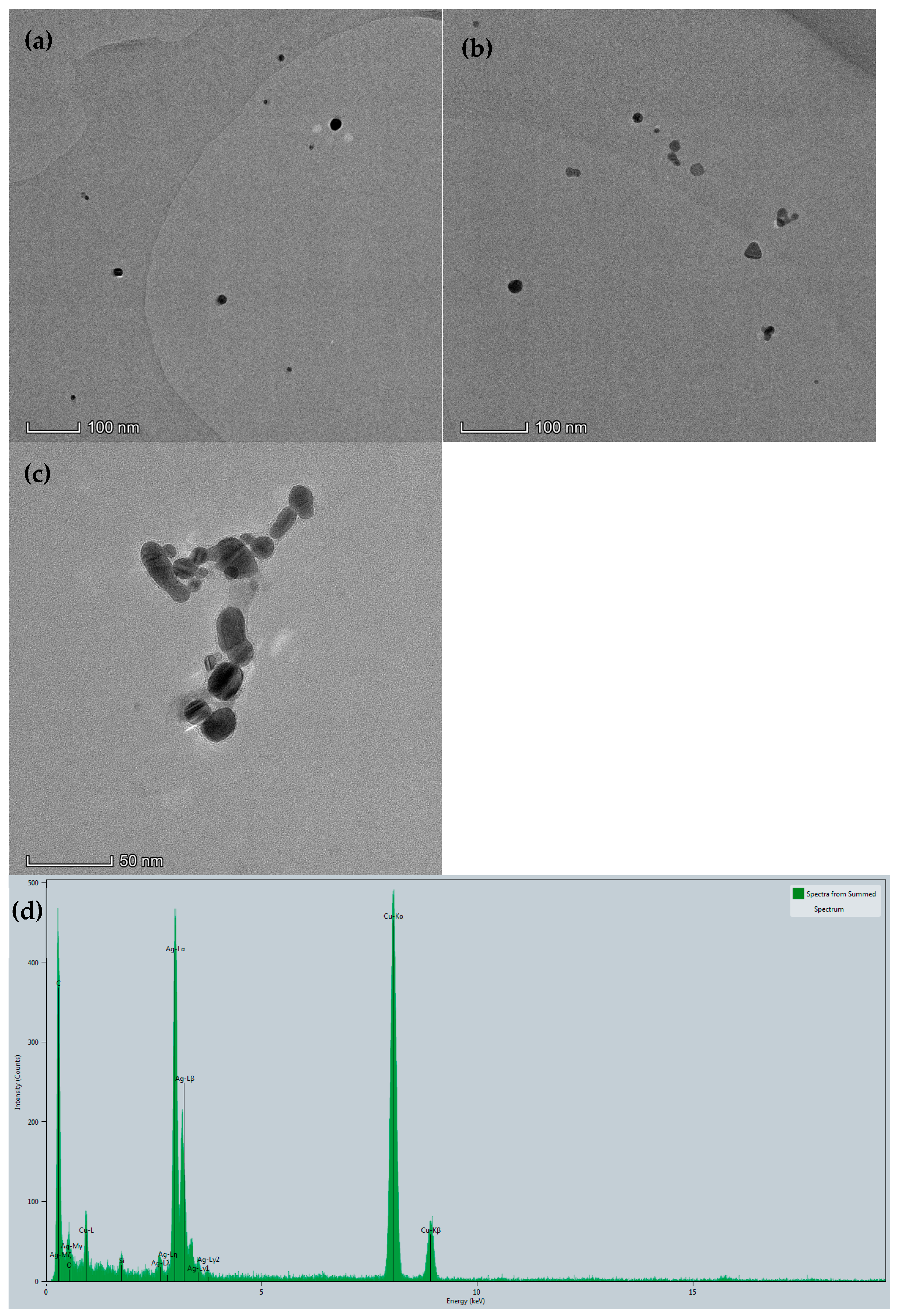

2.2. TEM

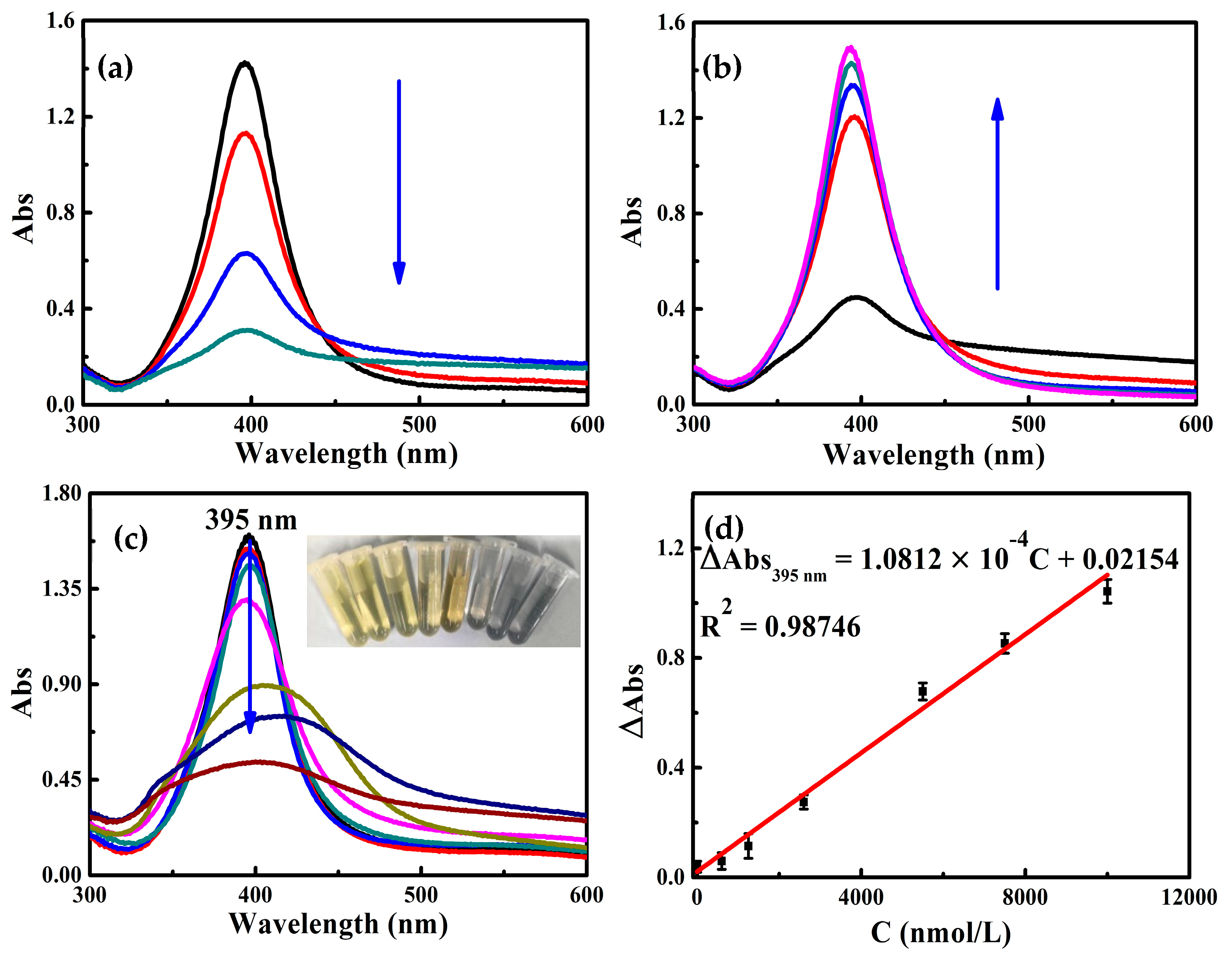

2.3. Abs Spectra

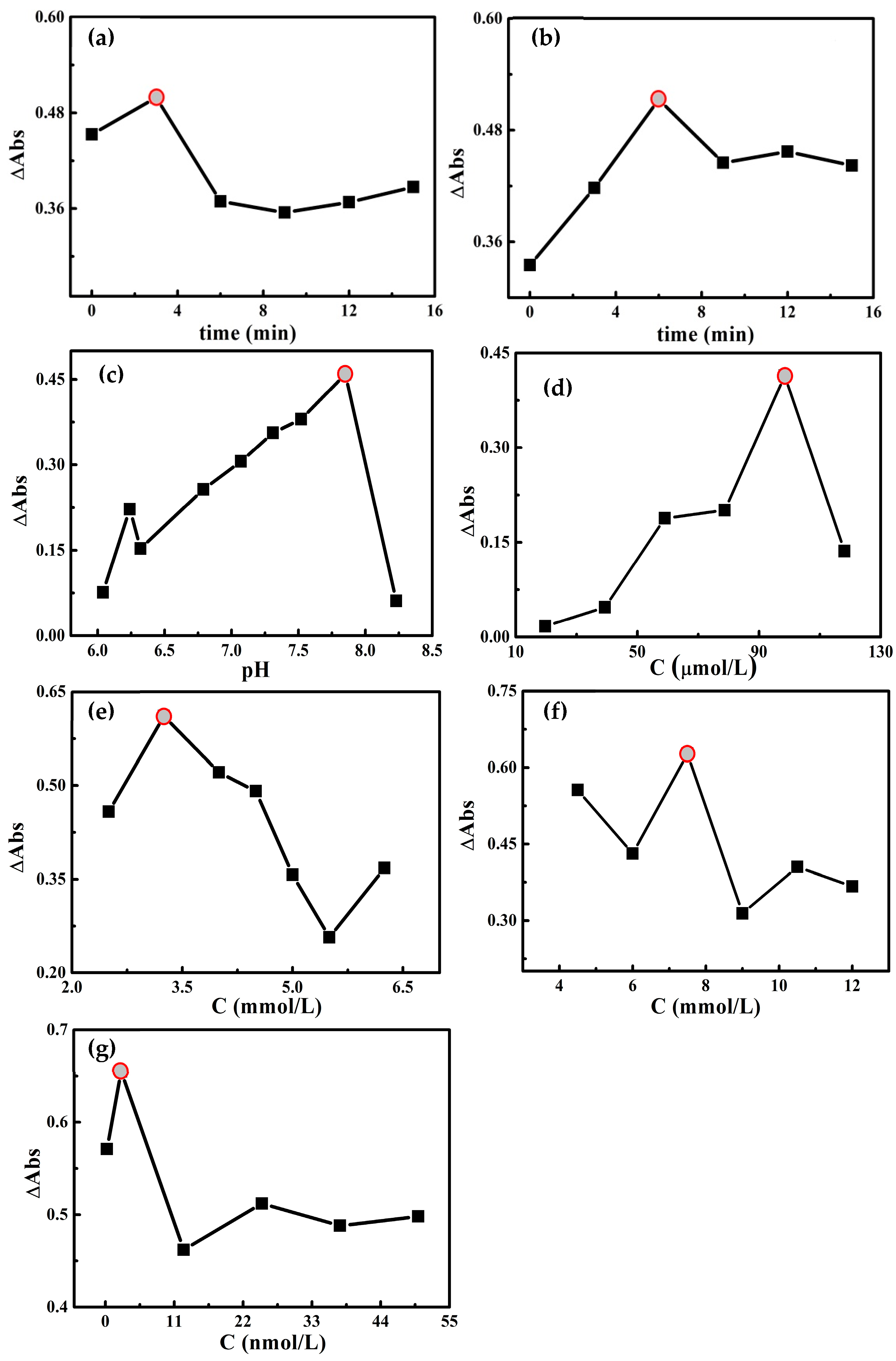

2.4. Conditional Optimization

2.5. Working Curve

2.6. Effects of Coexisting Interfering Ions

2.7. Stability

2.8. Analysis of Real Samples

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Instruments and Reagents

3.2. Procedure

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fahim, M.; Shahzaib, A.; Nishat, N.; Jahan, A.; Bhat, T.A.; Inam, A. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles: A Comprehensive Review of Methods, Influencing Factors, and Applications. JCIS Open 2024, 16, 100125–100148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sani Aliero, A.; Hasmoni, S.H.; Haruna, A.; Isah, M.; Malek, N.A.N.N.; Ahmad Zawawi, N. Bibliometric Exploration of Green Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles for Antibacterial Activity. Emerg. Contam. 2025, 11, 100411–100427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.; Gonsalves, R.A.; Jose, J.; Zyoud, S.H.; Prasad, A.R.; Garvasis, J. Plant-Based Synthesis, Characterization Approaches, Applications and Toxicity of Silver Nanoparticles: A Comprehensive Review. J. Biotechnol. 2024, 394, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Goksen, G.; Khan, M.R.; Ahmad, N.; Zhang, W. Green-Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles Immobilized on Graphene Oxide for Fruit Preservation in Alginate Films. Food Biosci. 2024, 62, 105127–105141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieu, M.D.; Dang, T.K.T.; Nguyen, T.H. Green Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles, a Sustainable Approach for Fruit and Vegetable Preservation: An Overview. Food Chem. X 2024, 23, 101664–101679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Singh, J.; Pandey, B.K.; Dhar, R. Green Synthesis of Oscimum Sanctum Mediated Silver Nanoparticles to Fabricate Sensors for Hydrogen Peroxide Detection. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 414, 126188–126198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Liu, L.; Zhang, W.; Wu, W.; Zhao, X.; Chen, N.; Zhang, M.; Guo, F.; Qin, Y. Visual Determination of Azodicarbonamide in Flour by Label-Free Silver Nanoparticle Colorimetry. Food Chem. 2021, 337, 127990–127996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Wu, S.; Luo, Z.; Lin, L.L.; Ye, J. Oppositely-Charged Silver Nanoparticles Enable Selective SERS Molecular Enhancement through Electrostatic Interactions. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2024, 322, 124852–124862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinayagam, R.; Nagendran, V.; Goveas, L.C.; Narasimhan, M.K.; Varadavenkatesan, T.; Chandrasekar, N.; Selvaraj, R. Structural Characterization of Marine Macroalgae Derived Silver Nanoparticles and Their Colorimetric Sensing of Hydrogen Peroxide. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2024, 313, 128787–128795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Chu, S.; Wang, L.; Zhan, X.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, D. Dual-Mode Colorimetric Determination of As(III) Based on Negatively-Charged Aptamer-Mediated Aggregation of Positively-Charged AuNPs. Anal. Chim. Acta 2022, 1221, 340111–340119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.K.; Jang, C.-H. Ultrasensitive Colorimetric Detection of Amoxicillin Based on Tris-HCl-Induced Aggregation of Gold Nanoparticles. Anal. Biochem. 2022, 645, 114634–114640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Xu, J.; Xiong, L.; Wang, S.; Yu, C.; Lv, J.; Lin, J.-M. Recent Development of Chemiluminescence for Bioanalysis. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 166, 117213–117235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duo, Y.; Xiang, Z.; Gao, G.; Luo, G.; Tang, B.Z. Biomedical Application of Aggregation-Induced Emission Luminogen-Based Fluorescent Sensors. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 167, 117252–117282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.-Y.; Liang, X.; Liu, J.; Zhao, T.-Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, G.; Zhang, Z.; Zeng, J. An Achromatic Colorimetric Nanosensor for Sensitive Multiple Pathogen Detection by Coupling Plasmonic Nanoparticles with Magnetic Separation. Talanta 2023, 256, 124271–124278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Zhang, L.; Liu, W.; Jin, Y.; Li, B. Simple and Low-Cost Colorimetric Method for Quantification of Surface Oxygen Vacancy in Zinc Oxide. Talanta 2025, 282, 126969–126975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Y.; Yin, X.; Wei, X.; Xu, R.; Wei, L.; Chen, Y.; Ding, L.; Song, D. A Facile Colorimetric Sensor for Ketoprofen Detection in Milk: Integrating Molecularly Imprinted Polymers with Cu-Doped Fe3O4 Nanozymes. Food Chem. 2025, 463, 141207–141216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, H.P. Recent Advances in Colorimetric and Photoluminescent Fibrillar Devices, Photonic Crystals and Carbon Dot-Based Sensors for Mercury (II) Ion Detection. Talanta 2025, 282, 127018–127029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, T.; Li, W.; Wen, H.; Kong, L.; Zheng, M.; Ma, L.; Guo, W.; Meng, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; et al. Biocompatibility Evaluation and Imaging Application of a New Fluorescent Chemodosimeter for the Specific Detection of Mercury Ions in Environmental and Biological Samples. Microchem. J. 2024, 207, 111859–111868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.; Sun, T.; Grattan, K.T.V. A Turn-On Fluorescence-Based Fibre Optic Sensor for the Detection of Mercury. Sensors 2019, 19, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H.; Tong, Y.; Sheng, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, Q. Simultaneous Enrichment and Determination of Cadmium and Mercury Ions Using Magnetic PAMAM Dendrimers as the Adsorbents for Magnetic Solid Phase Extraction Coupled with High Performance Liquid Chromatography. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 386, 121658–121666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Di, K.; Jia, M.; Ding, L.; You, F.; Wang, K. ZIF-71/MWCNTs Membrane with Good Mechanical Properties and High Selectivity for Simultaneous Removal and Electrochemical Detection of Hg(II). Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 354, 129389–129400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicentino, P.D.O.; Brum, D.M.; Cassella, R.J. Development of a Method for Total Hg Determination in Oil Samples by Cold Vapor Atomic Absorption Spectrometry after Its Extraction Induced by Emulsion Breaking. Talanta 2015, 132, 733–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Yao, L.; Yao, B.; Meng, X.; Wu, Q.; Chen, Z.; Chen, W. Low-Cost Signal Enhanced Colorimetric and SERS Dual-Mode Paper Sensor for Rapid and Ultrasensitive Screening of Mercury Ions in Tea. Food Chem. 2025, 463, 141375–141385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lesang Madingwane, M.; Hendricks-Leukes, N.R.; Tadele Alula, M. Gold Nanoparticles Decorated Magnetic Nanozyme for Colorimetric Detection of Mercury (II) Ions via Enhanced Peroxidase-like Activity. Microchem. J. 2024, 204, 110962–110970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Ahmad, N.; Jadeja, Y.; Ganesan, S.; Abd Hamid, J.; Singh, P.; Kaur, K.; Hassen Jaseem, L. Fluorescence Sensor for Mercury Ions in Aqueous Mediums Based on Reduced Graphene Oxide Linked with Molybdenum Disulfide. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2025, 196, 112305–112312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, F.; Yang, X. Colorimetric Detection of Mercury(II) Ion Using Unmodified Silver Nanoparticles and Mercury-Specific Oligonucleotides. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2010, 2, 339–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, E.; Gao, R.; Ko, J.; Choi, N.; Lim, D.W.; Lee, E.K.; Chang, S.-I.; Choo, J. Trace Analysis of Mercury (II) Ions Using Aptamer-Modified Au/Ag Core–Shell Nanoparticles and SERS Spectroscopy in a Microdroplet Channel. Lab Chip 2013, 13, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciniak, L.; Nowak, M.; Trojanowska, A.; Tylkowski, B.; Jastrzab, R. The Effect of pH on the Size of Silver Nanoparticles Obtained in the Reduction Reaction with Citric and Malic Acids. Materials 2020, 13, 5444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernando, I.; Zhou, Y. Impact of pH on the Stability, Dissolution and Aggregation Kinetics of Silver Nanoparticles. Chemosphere 2019, 216, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khachornsakkul, K.; Trakoolwilaiwan, T.; Leelasattarathkul, T. Distance-Based Paper Microfluidic Analytical Device Using Aptamer Functionalized Silver Nanomaterial for Aflatoxin B1 Quantification in Food Products. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2026, 448, 138999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekmohamadi, M.; Mirzaei, S.; Rezayan, A.H.; Abbasi, V.; Abouei Mehrizi, A. µPAD-Based Colorimetric Nanogold Aptasensor for CRP and IL-6 Detection as Sepsis Biomarkers. Microchem. J. 2024, 197, 109744–109754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebanks, F.; Nasrallah, H.; Garant, T.M.; McConnell, E.M.; DeRosa, M.C. Colorimetric Detection of Aflatoxins B1 and M1 Using Aptamers and Gold and Silver Nanoparticles. Adv. Agrochem 2023, 2, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Yin, Z.; Cui, H.; Wei, X.; Yu, F.; Zhang, J.; Liao, F.; Wei, G.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; et al. A Novel Dual-Detection Electrochemiluminescence Sensor for the Selective Detection of Hg2+ and Zn2+: Signal Suppression and Activation Mechanisms. Anal. Chim. Acta 2024, 1330, 343283–343292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Dong, C.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Leng, Y.; Wang, G.; Chen, Z. Colorimetric Sensors Constructed with One Dimensional PtNi Nanowire and Pt Nanowire Nanozymes for Hg2+ Detection. Anal. Chim. Acta 2024, 1321, 343039–343049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Chai, K.; Kim, W.; Yoon, T.; Park, H.; Kim, W.; You, J.; Na, S.; Park, J. Highly Enhanced Hg2+ Detection Using Optimized DNA and a Double Coffee Ring Effect-Based SERS Map. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2024, 264, 116646–116656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, S.; Fan, Y.; Hu, X.; Yin, L.; Fu, H.; She, Y. A Highly Sensitive Fluorescent Probe Based on Functionalised Ionic Liquids for Timely Detection of Trace Hg2+ and CH3Hg+ in Food. Food Chem. 2025, 463, 141343–141353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Onazi, W.A.; Abdel-Lateef, M.A. Catalytic Oxidation of O-Phenylenediamine by Silver Nanoparticles for Resonance Rayleigh Scattering Detection of Mercury (II) in Water Samples. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2022, 264, 120258–120265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diao, Q.; Bu, Z.; Feng, R.; Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Tang, Z.; Liang, H.; Tian, Q.; Li, S.; Niu, X. Performance-Complementary Colorimetric/Electrochemical Bimodal Detection of Hg2+ Based on Analyte-Accelerated Peroxidase-Mimicking Activity of GO-AuNPs. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2025, 422, 136598–136606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Linear Range | Detection Limit | Comments | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemiluminescence sensor | 1 × 10−3–1 μmol/L | 4.71 nmol/L | Complex operation | [33] |

| Colorimetry | 1.0 × 10−3–200 μmol/L | 0.6748 nmol/L | Poor selectivity, narrow linear range | [34] |

| SERS | 1.0 × 10−6–100 μmol/L | 2.0871 × 10−4 nmol/L | High sensitivity, but complex operation | [35] |

| Fluorescence | 1.0 × 10−3–4 × 10−2 μmol/L | 0.1 nmol/L | Narrow linear range | [36] |

| RRS | 1.0 × 10−2–2 μmol/L | 4 nmol/L | Low sensitivity and narrow linear range | [37] |

| Colorimetry electrochemical method | 10–60 μg/L 0.001–20 μg/L | 3.33 μg/L 3.33 × 10−4 μg/L | Poor selectivity | [38] |

| Abs | 2.5 × 10−3–10.00 µmol/L | 2.03 nmol/L | Wide linear range, easy to operate, and fast | This work |

| Interfering Substances | Times | Relative Error | Interfering Substances | Times | Relative Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu2+ | 100 | 0.74% | SO32− | 80 | 3.02% |

| NH4+ | 100 | 1.23% | CO32− | 80 | −4.56% |

| K+ | 90 | 2.52% | P2O74− | 50 | 2.52% |

| SO42− | 100 | −0.15% | Pb2+ | 40 | 3.68% |

| Co2+ | 80 | 3.14% | HCO3− | 50 | −2.09% |

| NO3− | 80 | 3.25% | Ca2+ | 50 | 0.52% |

| HPO42− | 100 | 1.39% | Mn4+ | 10 | 4.03% |

| H2PO42− | 100 | 0.73% | Cr6+ | 10 | −4.53% |

| CH3COO− | 90 | −1.85% | Zn2+ | 80 | −2.39% |

| NO2− | 80 | −2.49% | Ba2+ | 5 | −0.49% |

| Fe3+ | 60 | −3.16% | Al3+ | 5 | −2.48% |

| Samples | Detected Value (μmol/L) | Average (μmol/L) (n = 5) | Added (μmol/L) | Found (μmol/L) | Recovery (%) | RSD (%) | Hg2+ Value (μmol/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.320, 0.312, 0.291, 0.301, 0.316 | 0.308 | 2.50 | 2.730 | 96.9 | 3.91 | 0.308 |

| 2 | 2.868, 2.592, 2.548, 2.653, 2.453 | 2.623 | 1.25 | 3.905 | 102.6 | 5.29 | 2.623 |

| 3 | 2.523, 2.292, 2.262, 2.429, 2.408 | 2.383 | 2.50 | 4.815 | 97.3 | 4.46 | 2.383 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, H.; Liang, X.; Ye, L.; Fu, L.; Jiang, Z.; Qin, D. Label-Free Aptamer–Silver Nanoparticles Abs Biosensor for Detecting Hg2+. Molecules 2025, 30, 4785. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244785

Wang H, Liang X, Ye L, Fu L, Jiang Z, Qin D. Label-Free Aptamer–Silver Nanoparticles Abs Biosensor for Detecting Hg2+. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4785. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244785

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Haolin, Xingan Liang, Lan Ye, Licong Fu, Zhiliang Jiang, and Dongmiao Qin. 2025. "Label-Free Aptamer–Silver Nanoparticles Abs Biosensor for Detecting Hg2+" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4785. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244785

APA StyleWang, H., Liang, X., Ye, L., Fu, L., Jiang, Z., & Qin, D. (2025). Label-Free Aptamer–Silver Nanoparticles Abs Biosensor for Detecting Hg2+. Molecules, 30(24), 4785. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244785