Synthesis and In Situ Application of a New Fluorescent Probe for Visual Detection of Copper(II) in Plant Roots

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

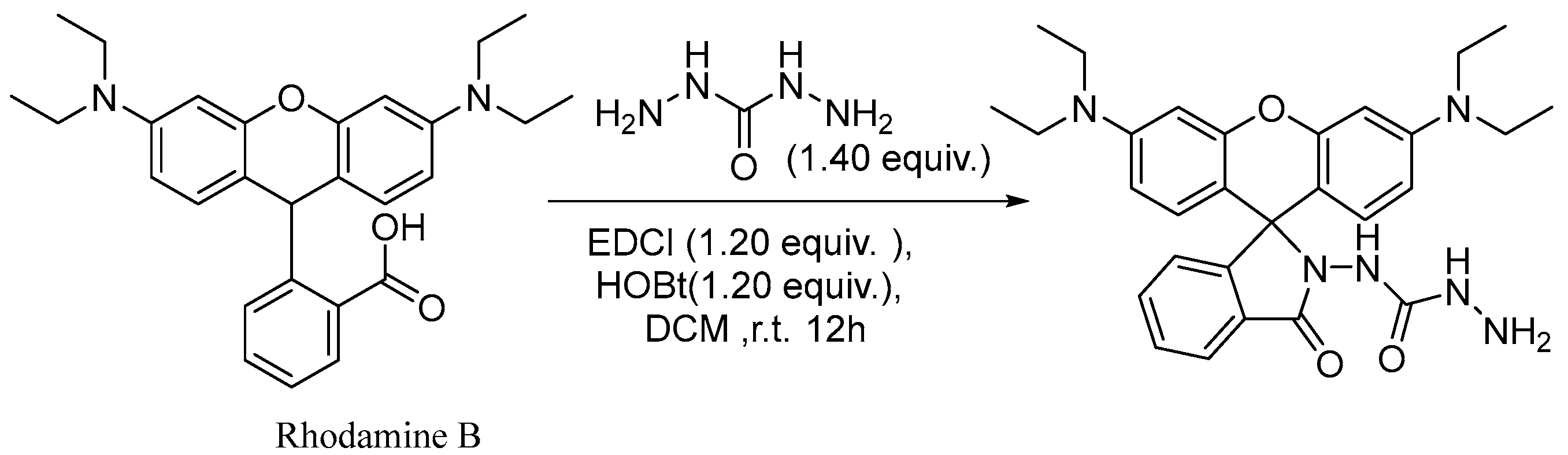

2.1. Design and Synthesis of RDC

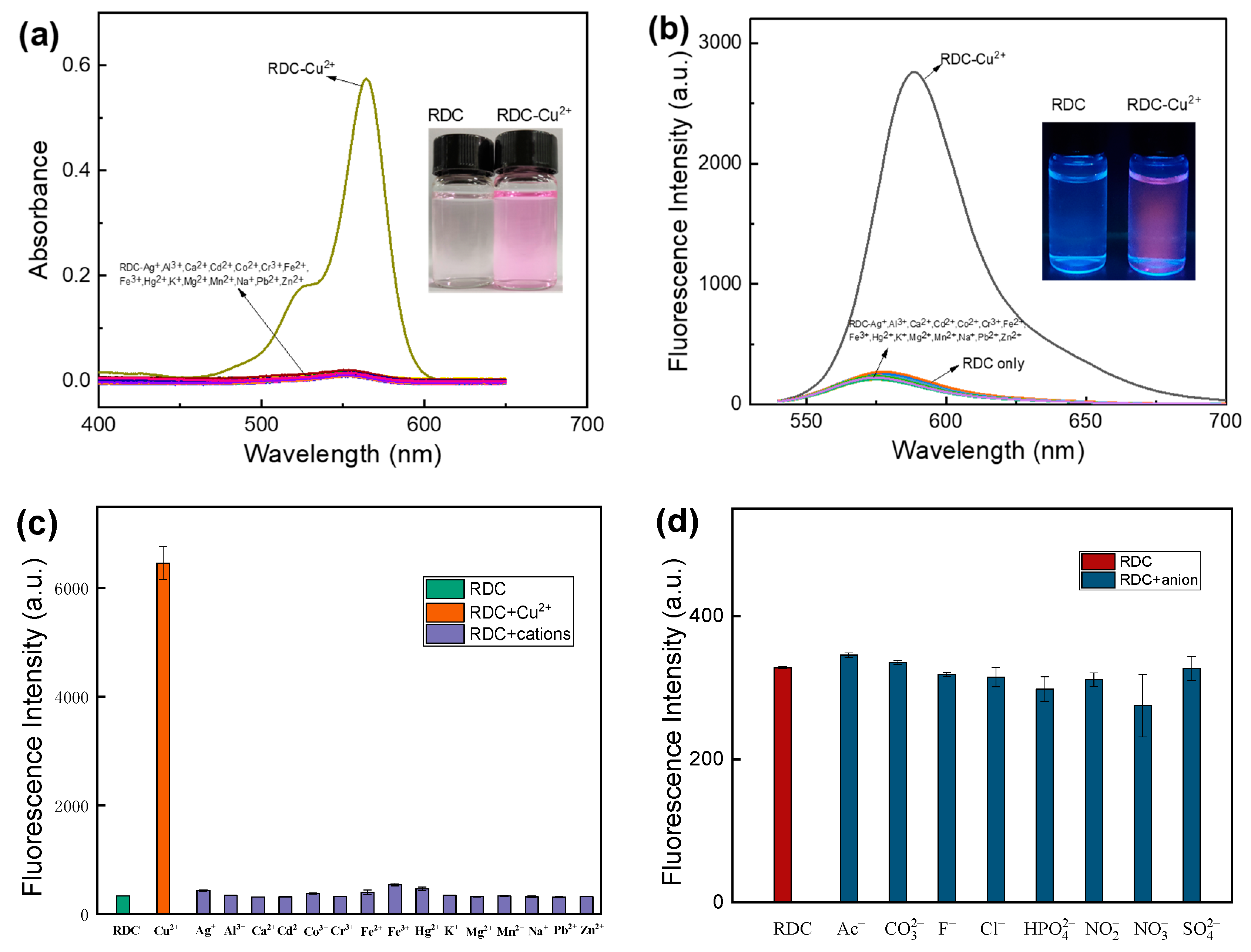

2.2. Spectral Properties of RDC and Selective Identification

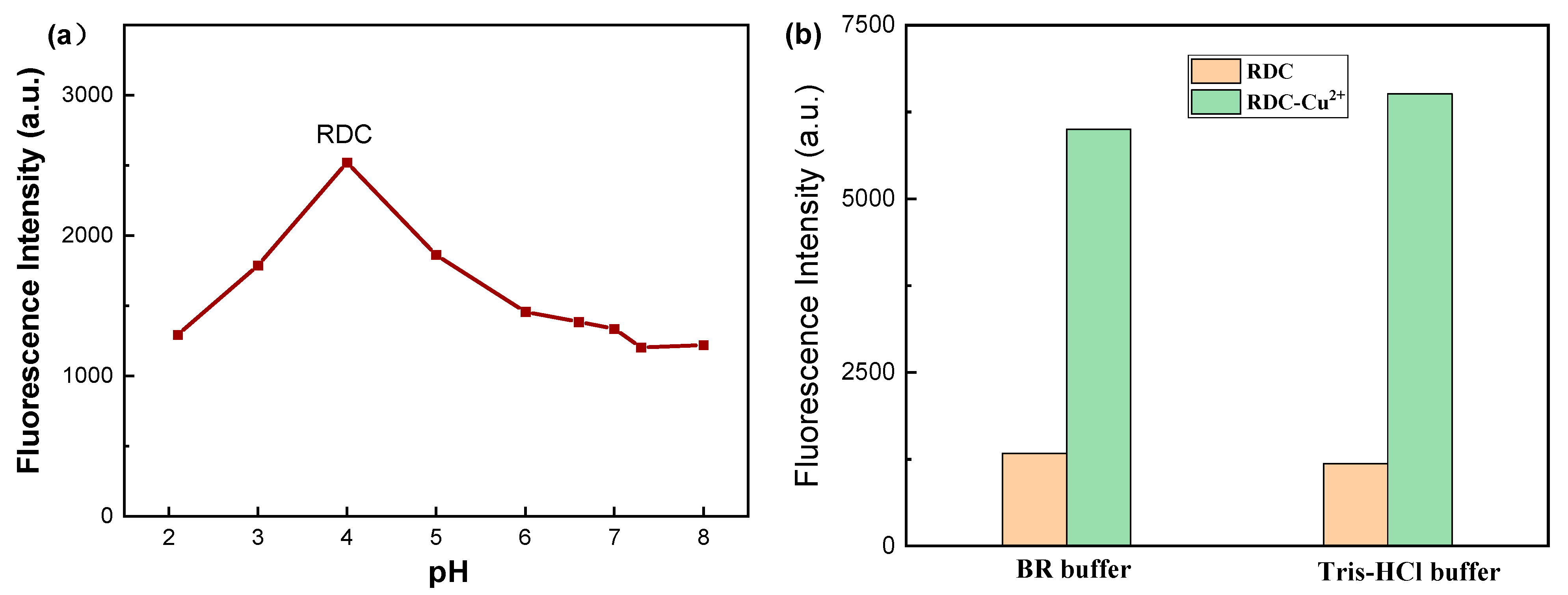

2.3. Optimization of Experimental Conditions

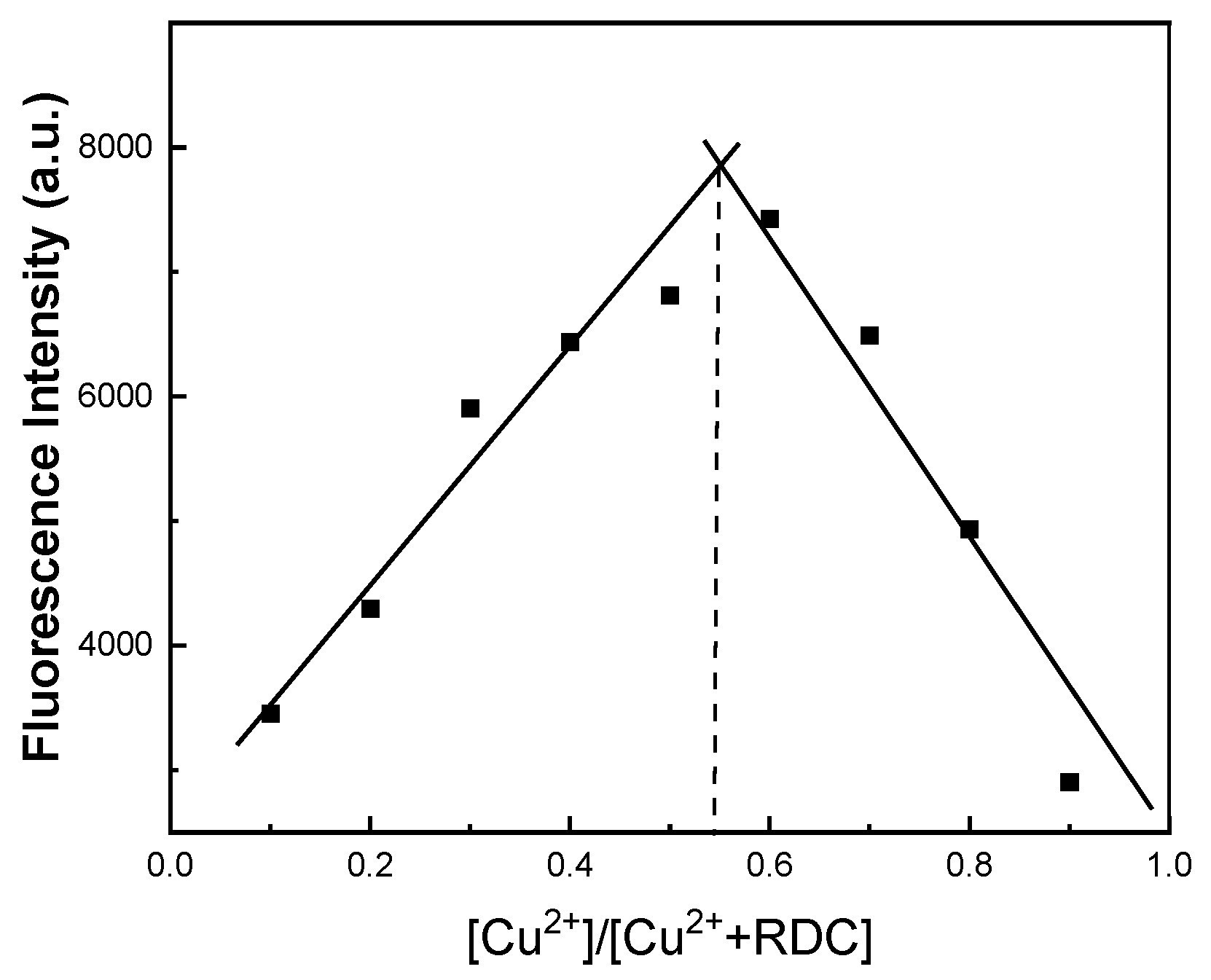

2.4. Linearity and Binding Stoichiometric Ratio

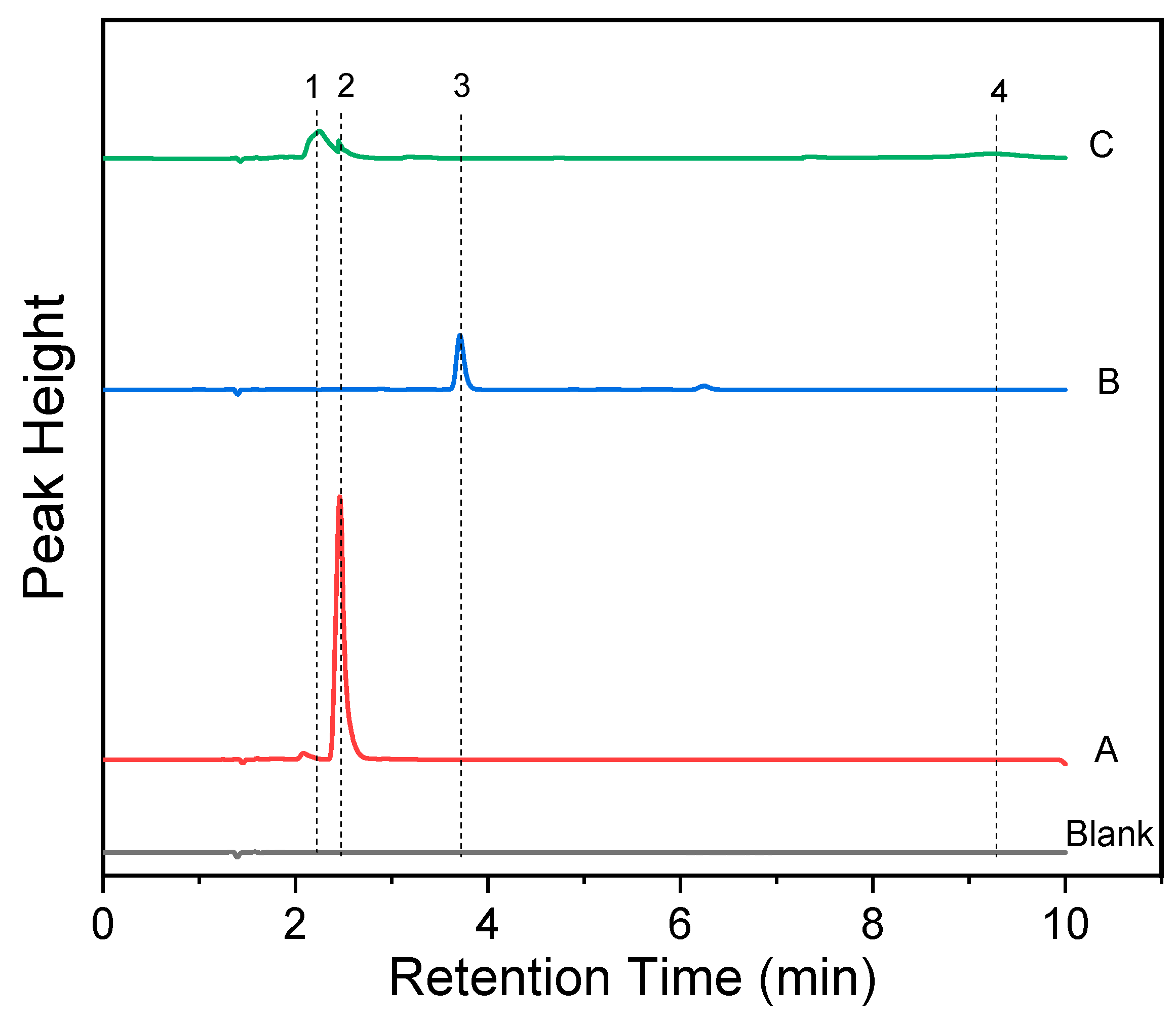

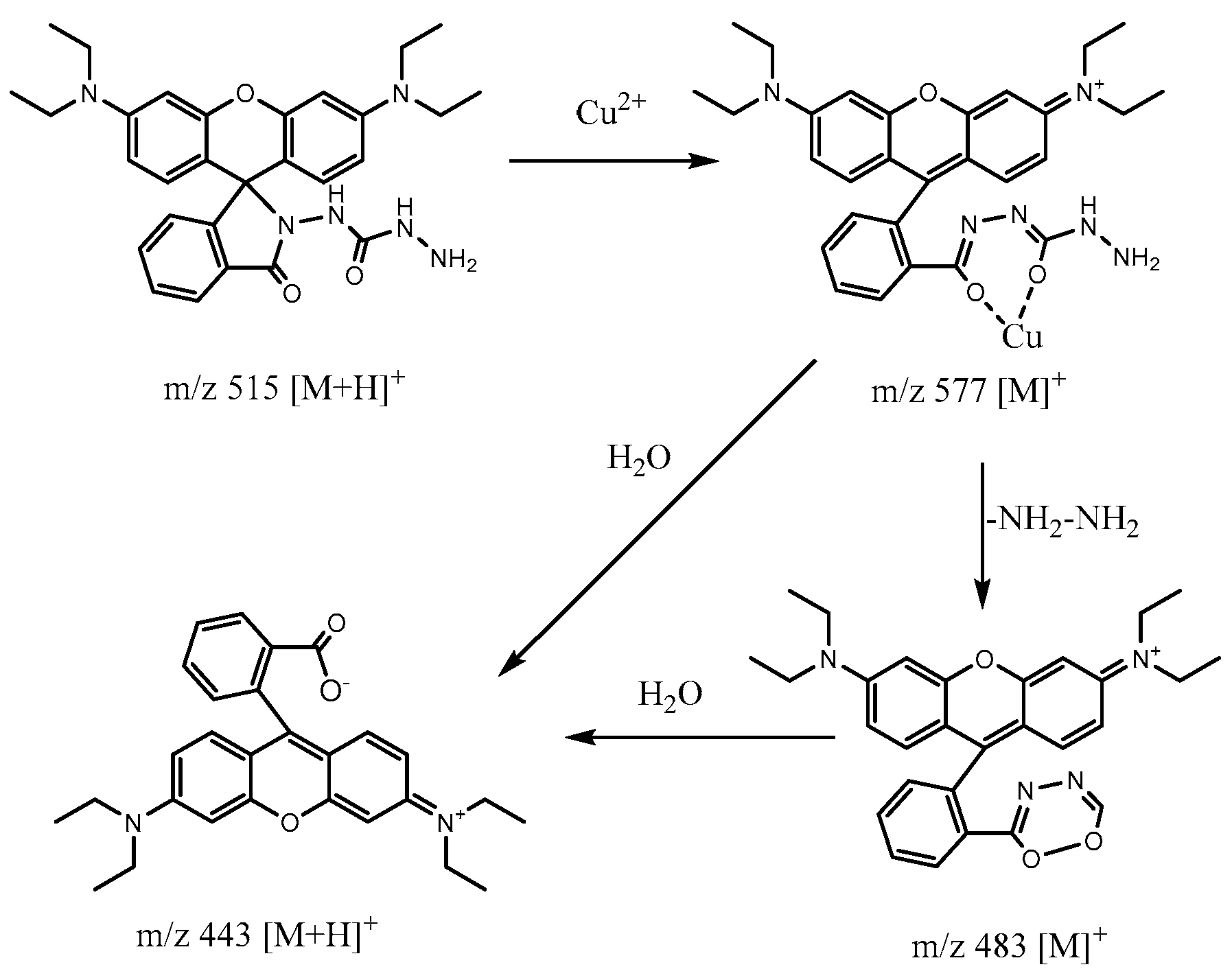

2.5. Fluorescence Reversibility of RDC and Reaction Mechanism

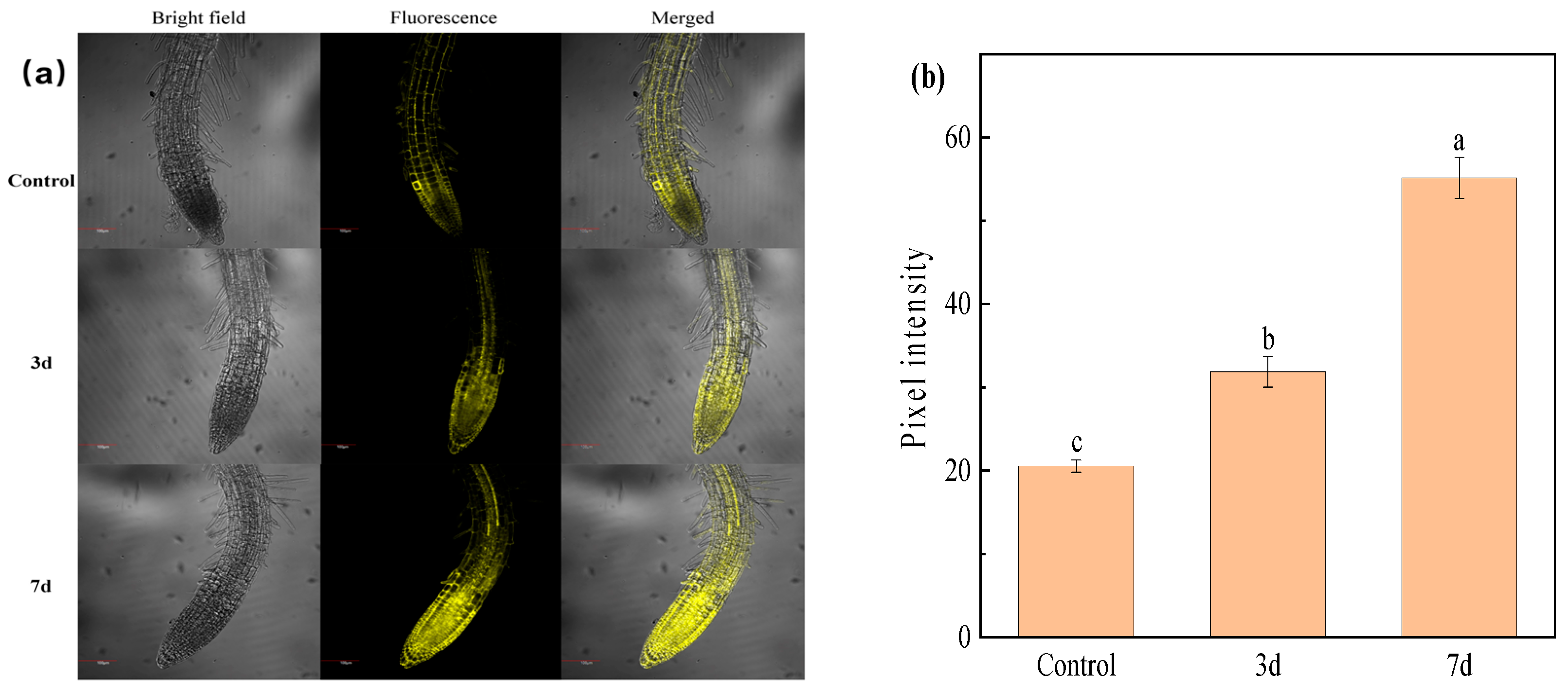

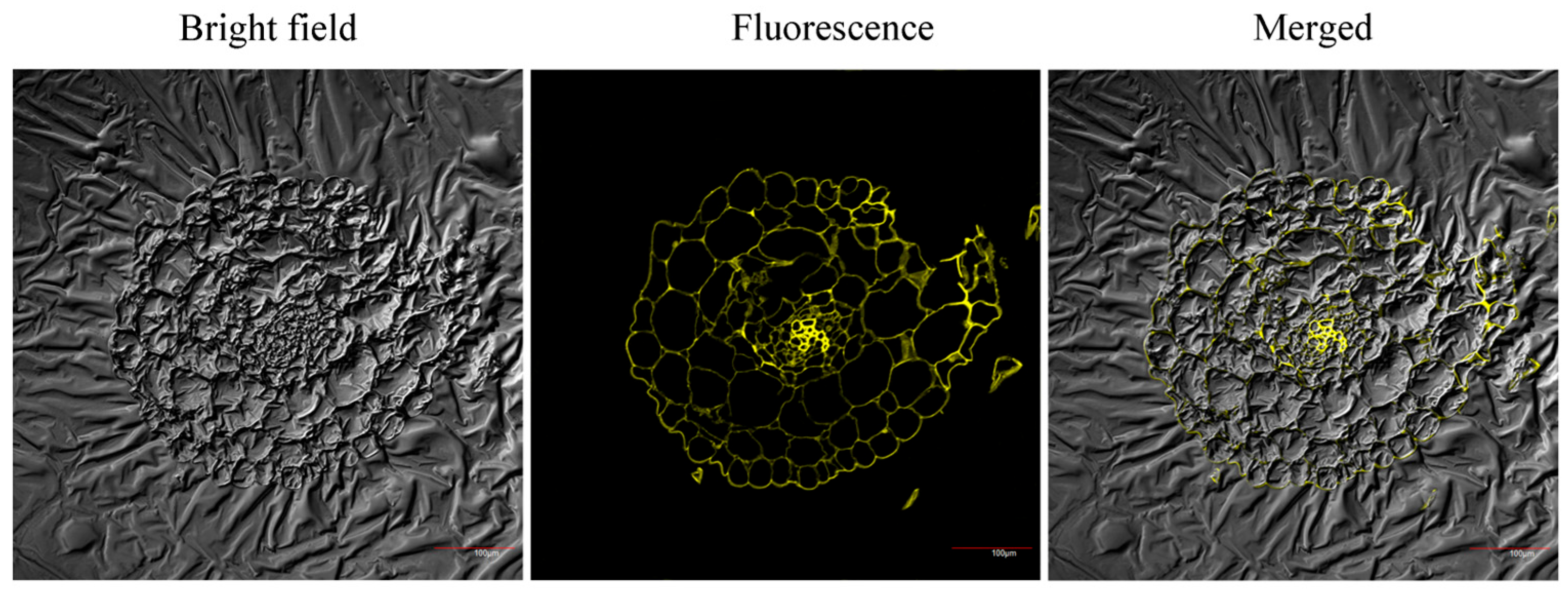

2.6. Fluorescence Imaging of Cu2+ in Plant Seedling Root Tissue

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials and Apparatus

3.2. The Optical Spectra of Probe Toward Cu2+

3.3. MTS Assays

3.4. Fluorescence Imaging of Cu2+ in Arabidopsis Thaliana and Burley Tobacco Root Tissues

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Cu2+ | Copper(II) ions |

| AES | Atomic emission spectroscopy |

| AAS | Atomic absorption spectroscopy |

| ICP-MS | Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| NIR | Near-infrared |

| RDC | Rhodamine derivative |

| DCM | Dichloromethane |

| EDCl | 1-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-3-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride |

| HOBT | 1-hydroxybenzotriazole |

| HPLC | High Performance Liquid Chromatography |

References

- Chen, G.; Li, J.; Han, H.M.; Du, R.Y.; Wang, X. Physiological and Molecular Mechanisms of Plant Responses to Copper Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, G.Z.; Cheng, S.M.; Zhang, J.; Yao, X.; Xie, X.L.; Xu, C.; Tang, Y.; Wang, X.; Tang, B. Cellular redox regulation and fluorescence imaging. Chem. Rev. 2025, 125, 7725–7810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.R.; Ouyang, Y.J.; Yin, H.; Cui, H.M.; Deng, H.D.; Liu, H.; Jian, Z.J.; Fang, J.; Zuo, Z.C.; Wang, X.; et al. Induction of autophagy via the ROS-dependent AMPK-mTOR pathway protects copper-induced spermatogenesis disorder. Redox Biol. 2022, 49, 102227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letelier, M.E.; Sánchez-Jofré, S.; Peredo-Silva, L.; Cortés-Troncoso, J.; Aracena-Parks, P. Mechanisms underlying iron and copper ions toxicity in biological systems: Pro-oxidant activity and protein-binding effects. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2010, 188, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juang, K.W.; Lo, Y.C.; Chen, T.H.; Ching, C.B. Effects of copper on root morphology, cations accumulation, and oxidative stress of grapevine seedlings. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2019, 102, 873–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, E.D.; Liu, Y.Y.; Gu, D.F.; Zhan, X.C.; Li, J.Y.; Zhou, K.N.; Zhang, P.J.; Zou, Y. Molecular mechanisms of plant responses to copper: From deficiency to excess. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopittke, P.M.; Asher, C.J.; Blamey, F.P.C.; Menzies, N.W. Toxic effects of Cu2+ on growth, nutrition, root morphology, and distribution of Cu in roots of Sabi grass. Sci. Total Environ. 2009, 407, 4616–4621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.; Schutte, B.J.; Ulery, A.; Deyholos, M.K.; Sanogo, S.; Lehnhoff, E.A.; Beck, L. Heavy metal contamination in agricultural soil: Environmental pollutants affecting crop health. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, A.R.; Pichtel, J.; Hayat, S. Copper: Uptake, toxicity and tolerance in plants and management of Cu-contaminated soil. BioMetals 2021, 34, 737–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Nkoh, J.N.; Hong, Z.N.; Dong, Y.; Lu, H.L.; Yang, J.; Pan, X.Y.; Xu, R.K. Phytotoxicity of Cu2+ and Cd2+ to the roots of four different wheat cultivars as related to charge properties and chemical forms of the metals on whole plant roots. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 196, 110545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.Y.; Kun, Q.; Kandawa-Schulz, M.; Miao, W.M.; Wang, Y.H. Direct determination of Cu2+ based on the electrochemical catalytic reaction of Fe3+/Cu2+. Electroanalysis 2020, 32, 620–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.J.; Xin, J.W.; Shen, Z.Y.; Zhang, Y.J.; Wang, H.Y.; Wu, A.G. Exploring a new rapid colorimetric detection method of Cu2+ with high sensitivity and selectivity. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2013, 176, 906–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, Y.P.; Guo, X.Y.; Wen, Y.; Yang, H.F. Rapid and selective detection of trace Cu2+ by accumulation- reaction-based Raman spectroscopy. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2019, 283, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downie, H.F.; Adu, M.O.; Schmidt, S.; Otten, W.; Dupuy, L.X.; White, P.J.; Valentine, T.A. Challenges and opportunities for quantifying roots and rhizosphere interactions through imaging and image analysis. Plant Cell Environ. 2015, 38, 1213–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzner, R.; Eggert, A.; van Dusschoten, D.; Pflugfelder, D.; Gerth, S.; Schurr, U.; Uhlmann, N.; Jahnke, S. Direct comparison of MRI and X-ray CT technologies for 3D imaging of root systems in soil: Potential and challenges for root trait quantification. Plant Methods 2015, 11, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xu, L.; Gao, H.; Song, J. Construction of dehydroabietic acid triarylamine-based “ESIPT + AIE” type molecule for “On-Off” sensing of Cu2+ and anti-counterfeiting. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2025, 469, 116565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavalishin, M.N.; Gamov, G.A.; Kiselev, A.N.; Nikitina, G.A. A fluorescein conjugate as colorimetric and red-emissive fluorescence chemosensor for selective recognition Cu2+ ions. Opt. Mater. 2024, 153, 115580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, K.; Koblova, A.; Pezacki, A.T.; Chang, C.J.; New, E.J. Small-molecule fluorescent probes for binding- and activity-based sensing of redox-active biological metals. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 5846–5929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.J.; Zhou, J.; Yuan, L.C.; Hou, J.C.; Wu, J.; Lin, P.C. A novel “off–on” peptide fluorescent probe for the detection of copper and sulphur ions in living cells. New J. Chem. 2024, 48, 5068–5073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.Y.; Zhu, H.C.; Wang, K.; Zhang, X.H.; Li, X.K.; Yu, M.H.; Zhu, B.C.; Sheng, W.L.; Liu, C.Y. A novel fluorescent chemodosimeter for discriminative detection of Cu2+ in environmental, food, and biological samples. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 3, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziya, A.; Bing, Y.; Bin, W.Y.; Lin, G.M. A novel near-infrared turn-on and ratiometric fluorescent probe capable of copper(ii) ion determination in living cells. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 6043–6046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.K.; Huang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, B.; Cao, D. A hydroxyl coumarin-chalcone-based fluorescent probe for sensing copper ions in plant and living cells. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2025, 270, 113218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, Y.Y.; Chen, W.L.; Hao, G.S.; Sun, J.P.; Shi, Q.F.; Tian, F.; Ma, R.T. A salicylaldehyde benzoyl hydrazone based near-infrared probe for copper(ii) and its bioimaging applications. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 3073–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F.Y.; Chen, L.; Yu, M.; Zhao, L.; Jiang, L.; Shi, T.Z.; Guo, J.; Zheng, H.Y.; Wang, R.X.; Liao, M.R. Triazine calixarene as a dual-channel chemosensor for the reversible detection of Cu2+ and I- Ions via water content modulation. Molecules 2025, 30, 2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.P.; Graziotto, M.E.; Cottam, V.; Hawtrey, T.; Adair, L.D.; Trist, B.G.; Pham, N.T.H.; Rouaen, J.R.C.; Ohno, C.; Heisler, M.; et al. Near-infrared ratiometric fluorescent probe for detecting endogenous Cu2+ in the Brain. ACS Sens. 2024, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtiar, A.; Najma, M.; Manthar, A.; Sami, C.A.; Rashmi, G.; Ye, J.H. Recent development in fluorescent probes for copper ion detection. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2022, 22, 835–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prajapati, M.; Pandey, N.; Kalla, S.; Bandaru, S.; Sivaiah, A. Synthesis and characterization of a rhodamine derivative as a selective switch-on fluorescent sensor for Cu2+ ions in aqueous PBS buffer and living cells. Sens. Diagn. 2024, 3, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, W.Y.; Jun, W.X.; Yu, M.W.; Hua, L.R.; Feng, Z.W.; Xiang, G.H. Recent developments in rhodamine-based chemosensors: A Review of the Years 2018–2022. Chemosensors 2022, 10, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soma, S.; Abhik, C.; Kinkar, B. A recent update on rhodamine dye based sensor molecules: A review. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2023, 54, 2351–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.L.; Li, H.; Long, L.P.; Xiao, G.Q.; Xie, D. Fast responsive fluorescence turn-on sensor for Cu2+ and its application in live cell imaging. J. Lumin. 2012, 132, 2456–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.M.; Mei, S.; Gang, C.Z.; You, L.F.; Xin, L.X.; Hong, G.Y.; Jia, X.; Hong, Y.; Guo, Z.Z.; Tao, Y.; et al. Highly sensitive and fast responsive fluorescence turn-on chemodosimeter for Cu2+ and its application in live cell imaging. Chemistry 2008, 14, 6892–6900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, L. Synthesis of rhodamine-helicin fluorescent probe for colorimetric detection of Cu2+ and fluorescent recognition of Fe3+. Sens. Int. 2024, 5, 100282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaviya, K.; Rajamanikandan, R.; Santhamoorthy, M.; Farah, M.A.; Mani, K.S. A rhodamine-conjugated fluorescent and colorimetric receptor for the detection of Cu2+ ions: Environmental utility and smartphone integration. Anal. Methods 2025, 17, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Z.; Li, S.; Ye, J.H.; Lin, F.; Chen, Y.; Guo, Z.; Gong, X. A rhodamine based near-infrared fluorescent probe for selective detection of Cu2+ ions and its applications in bioimaging. Anal. Methods Adv. Methods Appl. 2024, 17, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, T.; Xu, Y.Q.; Li, H.J.; Liu, F.Y.; Sun, S.G. A Rhodamine B-based fluorescent probe for imaging Cu2+ in maize roots. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2018, 26, 1448–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Hao, C.; Ding, C.; Zheng, X.; Liu, L.; Xie, P.; Guo, F. A near-infrared colorimetric and fluorometric chemodosimeter for Cu2+ based on a bis-spirocyclic rhodamine and its application in imagings. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2023, 49, 1771–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.X.; Luo, J.; Ndikuryayo, F.; Chen, Y.X.; Liu, G.Z.; Yang, W.C. Advances in fluorescence-based probes for abiotic stress detection in plants. ACS Sens. 2025, 10, 2474–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da, P.Y.; Jiao, L.M.; Ji, R.H.; Chao, Y.W.; Amit, S.; Yao, S.; Seung, K.J. Lighting up plants with near-infrared fluorescence probes. Sci. China Chem. 2023, 67, 774–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.P.; Zhang, S.Y.; Wang, H.Y.; Lai, M.; Zhang, D.; Ji, X.M. Recent advances in fluorescent probe for detecting biorelevant analytes during stress in plants. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 10701–10735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.Q.; Jia, J.; Ma, H.M.; Wang, S.J.; Wang, X.C. Characterization of rhodamine B hydroxylamide as a highly selective and sensitive fluorescence probe for copper(II). Anal. Chim. Acta 2007, 632, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Sun, S.N.; Li, X.H.; Ma, H.M. Imaging different interactions of mercury and silver with live cells by a designed fluorescence probe rhodamine B selenolactone. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 1206–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadia, B.; Cosimo, T.; Lucia, M.; Ana, R.; Francesco, S.; Cristiana, G.; Stefania, C.; Massimo, G.; Elisa, A.; Stefano, M. Zn2+-induced changes at the root level account for the increased tolerance of acclimated tobacco plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 4931–4942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaschenko, A.E.; Alonso, J.M.; Stepanova, A.N. Arabidopsis as a model for translational research. Plant Cell 2024, 37, koae065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wairich, A.; De Conti, L.; Lamb, T.I.; Keil, R.; Neves, L.O.; Brunetto, G.; Sperotto, R.A.; Ricachenevsky, F.K. Throwing Copper Around: How Plants Control Uptake, Distribution, and Accumulation of Copper. Agronomy 2022, 12, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopittke, P.M.; Menzies, N.W.; de Jonge, M.D.; McKenna, B.A.; Donner, E.; Webb, R.I.; Paterson, D.J.; Howard, D.L.; Ryan, C.G.; Glover, C.J.; et al. In situ distribution and speciation of toxic copper, nickel, and zinc in hydrated roots of cowpea. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, M.C. Metal complexation in xylem fluid: II. theoretical equilibrium model and computational computer program. Plant Physiol. 1981, 67, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, E.J.; Bush, A.I.; Casini, A.; Cobine, P.A.; Cross, J.R.; DeNicola, G.M.; Dou, Q.P.; Franz, K.J.; Gohil, V.M.; Gupta, S.; et al. Connecting copper and cancer: From transition metal signalling to metalloplasia. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2021, 22, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, D.; Guan, J.; Chen, W.; Zhang, L.; Fan, X.; Zhou, G.; Bao, Z. Synthesis and In Situ Application of a New Fluorescent Probe for Visual Detection of Copper(II) in Plant Roots. Molecules 2025, 30, 4783. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244783

Hu D, Guan J, Chen W, Zhang L, Fan X, Zhou G, Bao Z. Synthesis and In Situ Application of a New Fluorescent Probe for Visual Detection of Copper(II) in Plant Roots. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4783. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244783

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Dongyan, Jiao Guan, Wengao Chen, Liushuang Zhang, Xingrong Fan, Guisu Zhou, and Zhijuan Bao. 2025. "Synthesis and In Situ Application of a New Fluorescent Probe for Visual Detection of Copper(II) in Plant Roots" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4783. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244783

APA StyleHu, D., Guan, J., Chen, W., Zhang, L., Fan, X., Zhou, G., & Bao, Z. (2025). Synthesis and In Situ Application of a New Fluorescent Probe for Visual Detection of Copper(II) in Plant Roots. Molecules, 30(24), 4783. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244783