Wheat Pasta Enriched with Green Coffee Flour: Physicochemical, Antioxidant and Sensory Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Basic Chemical Composition of Raw Materials

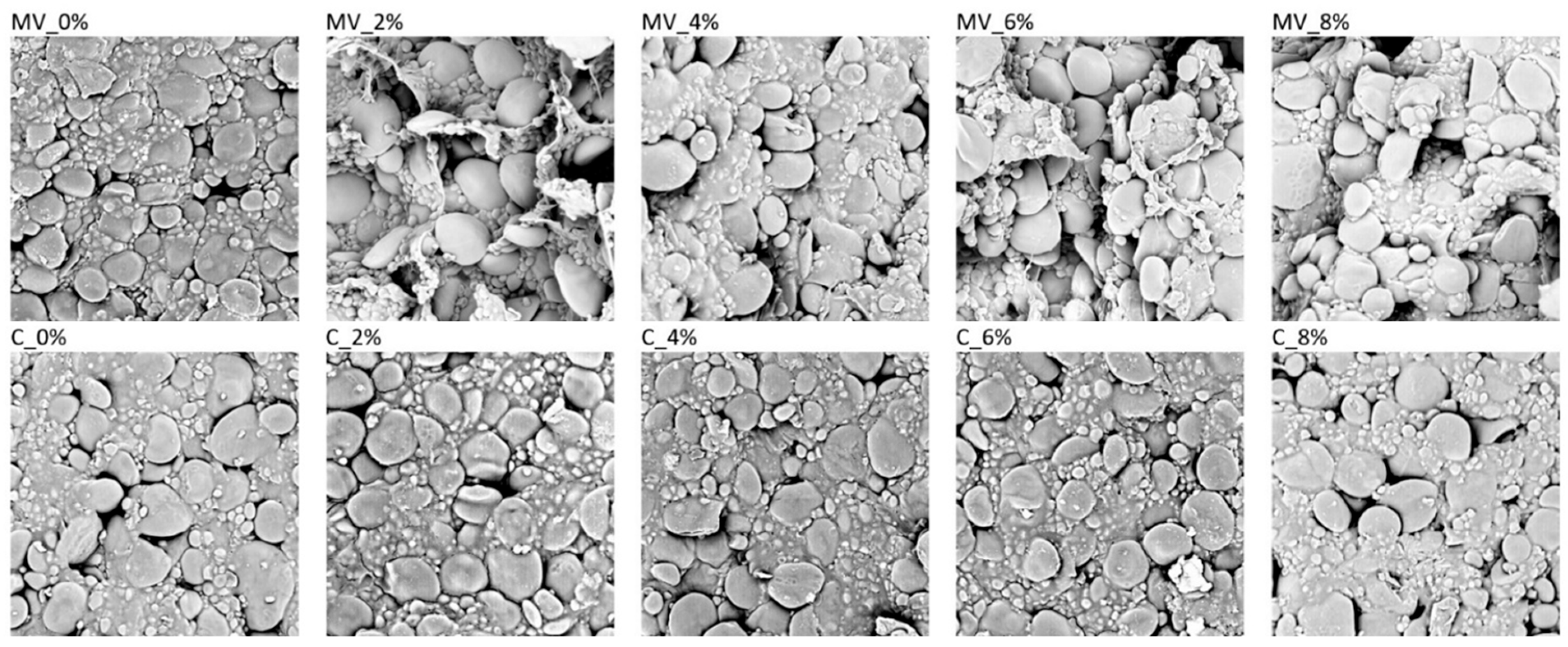

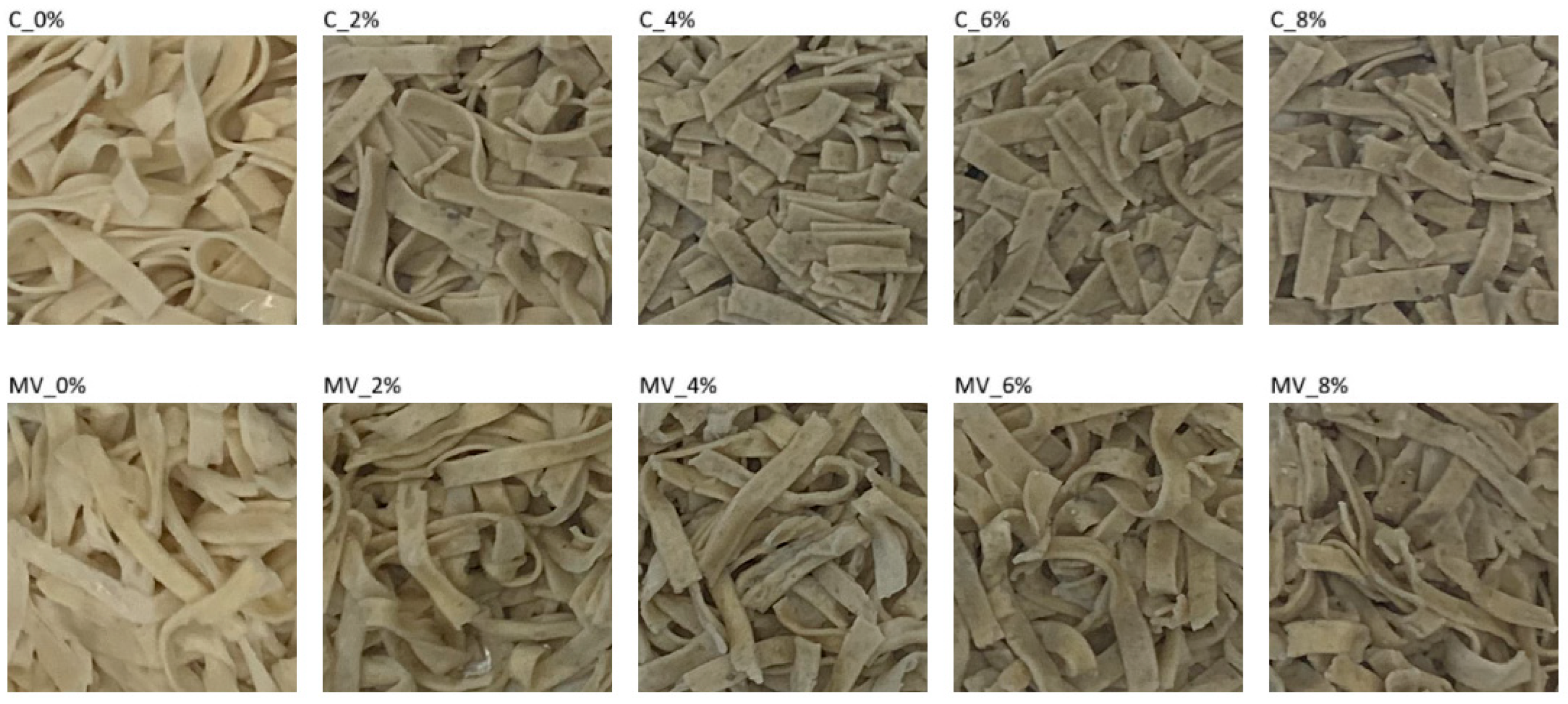

2.2. Microstructure of Pasta

2.3. Culinary Properties of Pasta

2.4. Color of Raw Materials and Pasta

2.5. Texture of Pasta

2.6. Total Polyphenols and Antioxidant Capacity

2.7. Results of Phenolic Acids Identification

2.8. Sensory Properties of Pasta

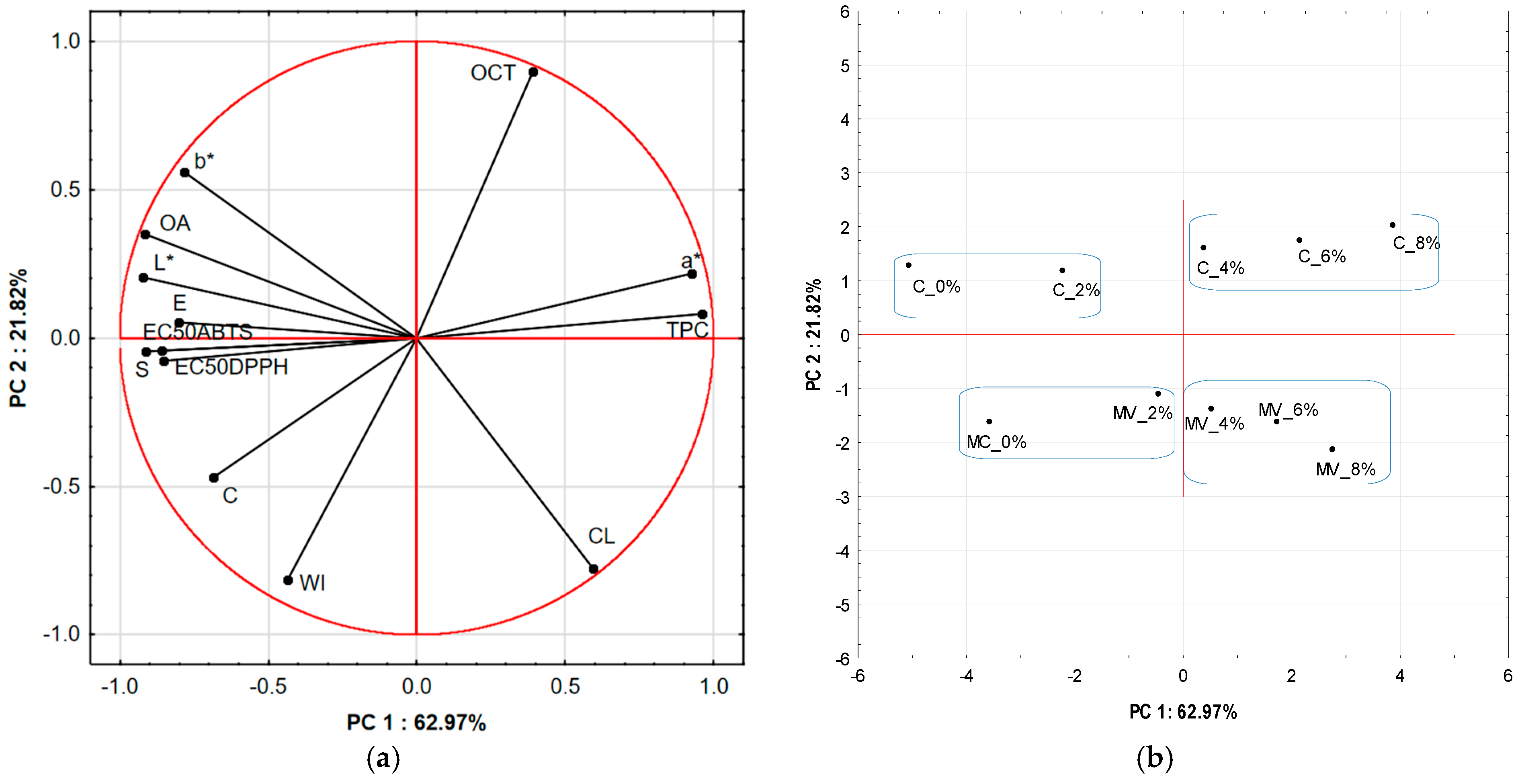

2.9. Principal Components Analysis

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Basic Composition of SE and GCF

3.3. Pasta Preparation

3.4. Determination of Pasta Microstructure

3.5. Determination of Culinary Properties of Pasta

3.6. Determination of the Color of Raw Materials and Pasta

3.7. Determination of Pasta Texture

3.8. Determination of Antioxidant Activity and Total Phenolics

3.8.1. Extract Preparation

3.8.2. Determination of ABTS and DPPH Radicals Scavenging Activity

3.8.3. Total Polyphenols Content

3.9. Phenolic Acids Analysis

3.10. Sensory Evaluation of Pasta

3.11. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pimpley, V.; Patil, S.; Srinivasan, K.; Desai, N.; Murthy, P.S. The Chemistry of Chlorogenic Acid from Green Coffee and Its Role in Attenuation of Obesity and Diabetes. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2020, 50, 969–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macheiner, L.; Schmidt, A.; Schreiner, M.; Mayer, H.K. Green Coffee Infusion as a Source of Caffeine and Chlorogenic Acid. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2019, 84, 103307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-González, A.; Figueroa-Hernández, C.Y.; González-Rios, O.; Suárez-Quiroz, M.L.; González-Amaro, R.M.; Hernández-Estrada, Z.J.; Rayas-Duarte, P. Coffee Chlorogenic Acids Incorporation for Bioactivity Enhancement of Foods: A Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.; Cao, J.; Feng, Q.; Peng, J.; Hu, Y. Roles of Chlorogenic Acid on Regulating Glucose and Lipids Metabolism: A Review. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 801457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, A.; Monteiro, M.; Donangelo, C.M.; Lafay, S. Chlorogenic Acids from Green Coffee Extract Are Highly Bioavailable in Humans. J. Nutr. 2008, 138, 2309–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshan, H.; Nikpayam, O.; Sedaghat, M.; Sohrab, G. Effects of Green Coffee Extract Supplementation on Anthropometric Indices, Glycaemic Control, Blood Pressure, Lipid Profile, Insulin Resistance and Appetite in Patients with the Metabolic Syndrome: A Randomised Clinical Trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2018, 119, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phung, O.J.; Baker, W.L.; Matthews, L.J.; Lanosa, M.; Thorne, A.; Coleman, C.I. Effect of Green Tea Catechins with or without Caffeine on Anthropometric Measures: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosso, H.; Barbalho, S.M.; de Alvares Goulart, R.; Otoboni, A.M.M.B. Green Coffee: Economic Relevance and a Systematic Review of the Effects on Human Health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 394–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samavat, S.; Ashtary-Larky, D.; Naeini, F.; Nazarian, B.; Kashkooli, S.; Clark, C.C.T.; Bagheri, R.; Asbaghi, O.; Babaali, M.; Goudarzi, M.A.; et al. The Effects of Green Coffee Bean Extract on Blood Pressure and Heart Rate: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2024, 18, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourmasoumi, M.; Hadi, A.; Marx, W.; Najafgholizadeh, A.; Kaur, S.; Sahebkar, A. The Effect of Green Coffee Bean Extract on Cardiovascular Risk Factors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1328, 323–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budryn, G.; Zyzelewicz, D.; Nebesny, E.; Oracz, J.; Krysiak, W. Influence of Addition of Green Tea and Green Coffee Extracts on the Properties of Fine Yeast Pastry Fried Products. Food Res. Int. 2013, 50, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahmohammadi, H.A.; Hosseini, S.A.; Hajiani, E.; Malehi, A.S.; Alipour, M. Effects of Green Coffee Bean Extract Supplementation on Patients with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Hepat. Mon. 2017, 17, e12299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, S.; Padalino, L.; Costa, C.; Del Nobile, M.A.; Conte, A. Food By-Products to Fortified Pasta: A New Approach for Optimization. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 985–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukkundur Vasudevaiah, A.; Chaturvedi, A.; Kulathooran, R.; Dasappa, I. Effect of Green Coffee Extract on Rheological, Physico-Sensory and Antioxidant Properties of Bread. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 1827–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glei, M.; Kirmse, A.; Habermann, N.; Persin, C.; Pool-Zobel, B.L. Bread Enriched with Green Coffee Extract Has Chemoprotective and Antigenotoxic Activities in Human Cells. Nutr. Cancer 2006, 56, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laily, N.; Wijayanti, S.P.; Alfakar, M.A.; Nurtama, B. Improvement of Bio-Active Compounds in Wheat-Based Functional Drink Formula with Green Coffee Extract Containing Chlorogenic Acid. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2025, 1485, 012007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.; Banerjee, D.; Sahu, D.; Tanveer, J.; Banerjee, S.; Jarzębski, M.; Jayaraman, S.; Deng, Y.; Kim, H.; Pal, K. Evaluating the Impact of Green Coffee Bean Powder on the Quality of Whole Wheat Bread: A Comprehensive Analysis. Foods 2024, 13, 2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świeca, M.; Gawlik-Dziki, U.; Dziki, D.; Baraniak, B. Wheat Bread Enriched with Green Coffee—In Vitro Bioaccessibility and Bioavailability of Phenolics and Antioxidant Activity. Food Chem. 2017, 221, 1451–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gawlik-Dziki, U.; Bryda, J.; Dziki, D.; Świeca, M.; Habza-Kowalska, E.; Złotek, U. Impact of Interactions between Ferulic and Chlorogenic Acids on Enzymatic and Non-Enzymatic Lipids Oxidation: An Example of Bread Enriched with Green Coffee Flour. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, W.P.C.; Pires, J.A.; Teixeira, N.N.; Bortoleto, G.G.; Gutierrez, E.M.R.; Melchert, W.R. Effects of Green Coffee Bean Flour Fortification on the Chemical and Nutritional Properties of Gluten-Free Cake. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2022, 16, 3451–3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, U.K.; Rahman, N.A.A.; Suzihaque, M.U.H.; Hashib, S.A.; Aziz, R.A.A. Effect of Baking Conditions on the Physical Properties of Bread Incorporated with Green Coffee Beans (GCB). IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 736, 062019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, N.M.; Mallik, B.; Sakhare, S.D.; Murthy, P.S. Prebiotic Oligosaccharide Enriched Green Coffee Spent Cookies and Their Nutritional, Physicochemical and Sensory Properties. LWT 2020, 134, 109924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdi, A.P.G.; Rousta, L.K.; Tabrizzad, A.M.H.; Amini, M.; Tavakoli, M.; Yahyavi, M. A Review: New Approach to Enrich Pasta with Fruits and Vegetables. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 17, 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, F.; Tolve, R.; Rainero, G.; Bordiga, M.; Brennan, C.S.; Simonato, B. Technological, Nutritional and Sensory Properties of Pasta Fortified with Agro-Industrial by-Products: A Review. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 4356–4366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balli, D.; Cecchi, L.; Innocenti, M.; Bellumori, M.; Mulinacci, N. Food By-Products Valorisation: Grape Pomace and Olive Pomace (Pâté) as Sources of Phenolic Compounds and Fiber for Enrichment of Tagliatelle Pasta. Food Chem. 2021, 355, 129642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, B.C.C.; Machado, M.; Machado, S.; Costa, A.S.G.; Bessada, S.; Alves, R.C.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P. Algae Incorporation and Nutritional Improvement: The Case of a Whole-Wheat Pasta. Foods 2023, 12, 3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zen, C.K.; Tiepo, C.B.V.; da Silva, R.V.; Reinehr, C.O.; Gutkoski, L.C.; Oro, T.; Colla, L.M. Development of Functional Pasta with Microencapsulated Spirulina: Technological and Sensorial Effects. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020, 100, 2018–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zweifel, C.; Handschin, S.; Escher, F.; Conde-Petit, B. Influence of High-Temperature Drying on Structural and Textural Properties of Durum Wheat Pasta. Cereal Chem. 2003, 80, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pilli, T.; Giuliani, R.; Derossi, A.; Severini, C. Study of Cooking Quality of Spaghetti Dried through Microwaves and Comparison with Hot Air Dried Pasta. J. Food Eng. 2009, 95, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drabińska, N.; Nogueira, M.; Ciska, E.; Jeleń, H. Effect of Drying and Broccoli Leaves Incorporation on the Nutritional Quality of Durum Wheat Pasta. Polish J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2022, 72, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, R.R.; Al-Ali, H.; Johnson, S.K. Extraction, Isolation and Nutritional Quality of Coffee Protein. Foods 2022, 11, 3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wieser, H. Chemistry of Gluten Proteins. Food Microbiol. 2007, 24, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poisson, L.; Blank, I.; Dunkel, A.; Hofmann, T. Chapter 12—The Chemistry of Roasting—Decoding Flavor Formation. In The Craft and Science of Coffee; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 273–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portillo, O.R.; Arévalo, A.C. Coffee’s Carbohydrates. A Critical Review of Scientific Literature. Bionatura 2022, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, P.; Joyce, S.A.; O’Toole, P.W.; O’Connor, E.M. Dietary Fibre Modulates the Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladunmoye, O.O.; Aworh, O.C.; Maziya-Dixon, B.; Erukainure, O.L.; Elemo, G.N. Chemical and Functional Properties of Cassava Starch, Durum Wheat Semolina Flour, and Their Blends. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 2, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporaso, N.; Whitworth, M.B.; Grebby, S.; Fisk, I.D. Non-Destructive Analysis of Sucrose, Caffeine and Trigonelline on Single Green Coffee Beans by Hyperspectral Imaging. Food Res. Int. 2018, 106, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacak-Pietrzak, G.; Marzec, A.; Rakocka, A.; Cendrowski, A.; Stępniewska, S.; Nowak, R.; Krajewska, A.; Dziki, D. The Effect of the Incorporation Level of Rosa Rugosa Fruit Pomace and Its Drying Method on the Physicochemical, Microstructural, and Sensory Properties of Wheat Pasta. Molecules 2025, 30, 3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.P.M.; Marzec, A. Effect of Microwave–Vacuum Drying and Pea Protein Fortification on Pasta Characteristics. Processes 2024, 12, 2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, F.; Li, C.; Ban, X.; Gu, Z.; Li, Z. Acceleration Mechanism of the Rehydration Process of Dried Rice Noodles by the Porous Structure. Food Chem. 2024, 431, 137050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teterycz, D.; Sobota, A.; Przygodzka, D.; Lysakowska, P. Hemp Seed (Cannabis sativa L.) Enriched Pasta: Physicochemical Properties and Quality Evaluation. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, B.X.; Schlichting, L.; Pozniak, C.J.; Singh, A.K. Pigment Loss from Semolina to Dough: Rapid Measurement and Relationship with Pasta Colour. J. Cereal Sci. 2013, 57, 560–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquivel, P.; Viñas, M.; Steingass, C.B.; Gruschwitz, M.; Guevara, E.; Carle, R.; Schweiggert, R.M.; Jiménez, V.M. Coffee (Coffea arabica L.) by-Products as a Source of Carotenoids and Phenolic Compounds—Evaluation of Varieties With Different Peel Color. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 590597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feillet, P.; Autran, J.C.; Icard-Vernière, C. Pasta Brownness: An Assessment. J. Cereal Sci. 2000, 32, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwińska, M.; Wyrwisz, J.; Kurek, M.A.; Wierzbicka, A. Effect of Drying Methods on the Physical Properties of Durum Wheat Pasta. CyTA J. Food 2016, 14, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verardo, V.; Riciputi, Y.; Messia, M.C.; Marconi, E.; Caboni, M.F. Influence of Drying Temperatures on the Quality of Pasta Formulated with Different Egg Products. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2017, 243, 817–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpentieri, S.; Larrea-Wachtendorff, D.; Ferrari, G. Influence of Semolina Characteristics and Pasta-Making Process on the Physicochemical, Structural, and Sensorial Properties of Commercial Durum Wheat Spaghetti. Front. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 4, 1416654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Nishizu, T.; Hayakawa, S.; Nakashima, R.; Goto, K. Effects of Different Drying Conditions on Water Absorption and Gelatinization Properties of Pasta. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2013, 6, 2000–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Shen, H.; Ma, S.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, X.; Jiang, H. Morphological Distribution and Structure Transition of Gluten Induced by Various Drying Technologies and Its Effects on Chinese Dried Noodle Quality Characteristics. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2023, 16, 1374–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altan, A.; Maskan, M. Microwave Assisted Drying of Short-Cut (Ditalini) Macaroni: Drying Characteristics and Effect of Drying Processes on Starch Properties. Food Res. Int. 2005, 38, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zain, M.Z.M.; Baba, A.S.; Shori, A.B. Effect of Polyphenols Enriched from Green Coffee Bean on Antioxidant Activity and Sensory Evaluation of Bread. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2018, 30, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, M.; Hejazi, V.; Abbas, M.; Kamboh, A.A.; Khan, G.J.; Shumzaid, M.; Ahmad, F.; Babazadeh, D.; FangFang, X.; Modarresi-Ghazani, F.; et al. Chlorogenic Acid (CGA): A Pharmacological Review and Call for Further Research. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 97, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanchanasurakit, S.; Saokaew, S.; Phisalprapa, P.; Duangjai, A. Chlorogenic Acid in Green Bean Coffee on Body Weight: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Syst. Rev. 2023, 12, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverri-Giraldo, L.F.; Osorio Pérez, V.; Tabares Arboleda, C.; Vargas Gutiérrez, L.J.; Imbachi Quinchua, L.C. Content of Acidic Compounds in the Bean of Coffea arabica L., Produced in the Department of Cesar (Colombia), and Its Relationship with the Sensorial Attribute of Acidity. Separations 2024, 11, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffo, R.A.; Cardelli-Freire, C. Coffee Flavour: An Overview. Flavour Fragr. J. 2004, 19, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yulia, M.; Analianasari, A.; Widodo, S.; Kusumiyati, K.; Naito, H.; Suhandy, D. The Authentication of Gayo Arabica Green Coffee Beans with Different Cherry Processing Methods Using Portable LED-Based Fluorescence Spectroscopy and Chemometrics Analysis. Foods 2023, 12, 4302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Association of Cereal Chemistry (AACC). Approved Methods, 10th ed.; AACC: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2000; Available online: http://methods.aaccnet.org/toc.aspx (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Biernacka, B.; Dziki, D.; Różyło, R.; Gawlik-Dziki, U.; Nowak, R.; Pietrzak, W. Common Wheat Pasta Enriched with Ultrafine Ground Oat Husk: Physicochemical and Sensory Properties. Molecules 2023, 28, 7197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujka, K.; Cacak-Pietrzak, G.; Sułek, A.; Murgrabia, K.; Dziki, D. Buckwheat Hull-Enriched Pasta: Physicochemical and Sensory Properties. Molecules 2022, 27, 4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsa, A.; Roldan, S.; Marquina, P.L.; Roncalés, P.; Beltrán, J.A.; Calanche Morales, J.B. Quality Parameters and Technological Properties of Pasta Enriched with a Fish By-Product: A Healthy Novel Food. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2022, 46, e16261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Złotek, U.; Gawlik-Dziki, U.; Dziki, D.; Świeca, M.; Nowak, R.; Martinez, E. Influence of Drying Temperature on Phenolic Acids Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Sprouts and Leaves of White and Red Quinoa. J. Chem. 2019, 2019, 7125169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowacka, N.; Nowak, R.; Drozd, M.; Olech, M.; Los, R.; Malm, A. Antibacterial, Antiradical Potential and Phenolic Compounds of Thirty-One Polish Mushrooms. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrzak, W.; Nowak, R.; Gawlik-Dziki, U.; Lemieszek, M.K.; Rzeski, W. LC-ESI-MS/MS Identification of Biologically Active Phenolic Compounds in Mistletoe Berry Extracts from Different Host Trees. Molecules 2017, 22, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wichchukit, S.; O’Mahony, M. The 9-Point Hedonic Scale and Hedonic Ranking in Food Science: Some Reappraisals and Alternatives. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015, 95, 2167–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample | Protein (% d.m.) | Ash (% d.m.) | Fat (% d.m.) | Fiber (% d.m.) | Carbohydrates (% d.m.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SE | 12.01 ± 0.05 A | 0.87 ± 0.01 A | 0.80 ± 0.03 A | 3.25 ± 0.06 A | 83.07 ± 0.03 A |

| GCF | 17.59 ± 0.00 B | 3.37 ± 0.04 B | 10.45 ± 0.12 B | 22.05 ± 0.18 B | 46.54 ± 0.03 B |

| Drying Method | Green Coffee Flour Content (%) | Optimal Cooking Time (min) | Weight Increase Index (-) | Cooking Loss (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Convective | 0 | 7.0 ± 0.05 e | 2.5 ± 0.0 a | 5.10 ± 0.00 a |

| 2 | 8.5 ± 0.00 f | 2.6 ± 0.1 ab | 5.30 ± 0.01 b | |

| 4 | 9.0 ± 0.10 g | 2.6 ± 0.1 ab | 5.98 ± 0.01 c | |

| 6 | 10.5 ± 0.05 h | 2.8 ± 0.0 c | 6.88 ± 0.02 d | |

| 8 | 11.5 ± 0.00 i | 2.8 ± 0.0 c | 7.31 ± 0.04 e | |

| Microwave-Vacuum | 0 | 3.5 ± 0.00 a | 3.0 ± 0.0 d | 7.54 ± 0.02 f |

| 2 | 4.0 ± 0.10 b | 2.9 ± 0.0 cd | 7.75 ± 0.00 g | |

| 4 | 4.5 ± 0.10 c | 3.0 ± 0.1 d | 8.05 ± 0.02 h | |

| 6 | 5.5 ± 0.05 d | 3.0 ± 0.1 d | 9.08 ± 0.00 i | |

| 8 | 5.5 ± 0.00 d | 3.3 ± 0.1 e | 10.40 ± 0.00 j | |

| Factor | Two-factor analysis of variance | |||

| p-value | ||||

| Drying method (DM) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Green coffee flour (GCF) content | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| DM × GCF | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Sample | L* (-) | a* (-) | b* (-) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SE | 84.57 ± 0.35 B | 1.66 ± 0.18 A | 22.31 ± 0.41 B |

| GCF | 71.65 ± 0.47 A | 2.16 ± 0.12 B | 16.42 ± 0.24 A |

| Drying Method | Green Coffee Flour Content (%) | L* (-) | a* (-) | b* (-) | ΔE (-) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Convective | 0 | 83.30 ± 0.69 d | 0.92 ± 0.03 ab | 16.51 ± 0.66 g | - |

| 2 | 81.18 ± 0.43 c | 0.99 ± 0.05 bc | 15.46 ± 0.36 ef | 2.37 b | |

| 4 | 78.71 ± 0.57 b | 1.21 ± 0.06 d | 15.27 ± 0.32 def | 4.76 d | |

| 6 | 77.88 ± 0.55 b | 1.40 ± 0.15 ef | 14.69 ± 0.30 cde | 5.74 e | |

| 8 | 76.23 ± 0.43 a | 1.56 ± 0.09 f | 14.48 ± 0.36 cd | 7.37 f | |

| Microwave-vacuum | 0 | 83.06 ± 0.47 d | 0.78 ± 0.03 a | 15.83 ± 0.60 fg | - |

| 2 | 82.37 ± 0.37 d | 0.96 ± 0.06 bc | 14.06 ± 0.44 bc | 1.91 a | |

| 4 | 80.65 ± 0.69 c | 1.13 ± 0.08 cd | 13.90 ± 0.39 bc | 3.12 c | |

| 6 | 78.44 ± 0.52 b | 1.29 ± 0.11 de | 13.49 ± 0.46 ab | 6.01 ef | |

| 8 | 78.01 ± 0.19 b | 1.45 ± 0.08 ef | 12.64 ± 0.32 a | 7.85 f | |

| Factor | Two-factor analysis of variance | ||||

| p-value | |||||

| Drying method (DM) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Green coffee flour (GCF) content | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| DM × GCF | <0.001 | 0.598 | 0.077 | <0.001 | |

| Drying Method | Green Coffee Flour Content (%) | Elasticity (-) | Springiness (-) | Cohesiveness (-) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Convective | 0 | 0.35 ± 0.02 c | 0.84 ± 0.01 c | 0.71 ± 0.01 f |

| 2 | 0.30 ± 0.00 c | 0.74 ± 0.01 bc | 0.69 ± 0.01 ef | |

| 4 | 0.23 ± 0.00 b | 0.51 ± 0.02 ab | 0.57 ± 0.02 c | |

| 6 | 0.20 ± 0.04 ab | 0.49 ± 0.03 b | 0.43 ± 0.03 b | |

| 8 | 0.15 ± 0.01 a | 0.39 ± 0.05 a | 0.36 ± 0.05 a | |

| Microwave-vacuum | 0 | 0.23 ± 0.00 b | 0.62 ± 0.00 abc | 0.61 ± 0.00 cd |

| 2 | 0.21 ± 0.01 ab | 0.56 ± 0.18 ab | 0.63 ± 0.18 cde | |

| 4 | 0.23 ± 0.02 b | 0.57 ± 0.01 ab | 0.66 ± 0.01 def | |

| 6 | 0.23 ± 0.02 b | 0.52 ± 0.00 ab | 0.64 ± 0.00 de | |

| 8 | 0.23 ± 0.01 b | 0.59 ± 0.02 ab | 0.61 ± 0.02 cd | |

| Factor | Two-factor analysis of variance | |||

| p-value | ||||

| Drying method (DM) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Green coffee flour (GCF) content | 0.025 | 0.485 | <0.001 | |

| DM × GCF | <0.001 | 0.004 | <0.001 | |

| Sample | TPC (mg GAE/g d.m.) | EC50ABTS (mg d.m./mL) | EC50DPPH (mg d.m./mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SE | 0.729 ± 0.08 A | 127.17 ± 1.63 A | 315.23 ± 3.62 A |

| GCF | 44.90 ± 0.65 B | 8.77 ± 0.06 B | 10.47 ± 0.25 B |

| Drying Method | Green Coffee Flour Content (%) | TPC (mg GAE/g d.m.) | EC50ABTS (mg d.m./mL) | EC50DPPH (mg d.m./mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Convective | 0 | 0.49 ± 0.02 a | 138.57 ± 0.35 g | 322.27 ± 1.80 e |

| 2 | 1.14 ± 0.01 b | 46.03 ± 1.33 e | 149.47 ± 0.75 d | |

| 4 | 1.91 ± 0.08 c | 40.07 ± 0.74 cd | 120.43 ± 1.17 c | |

| 6 | 2.36 ± 0.01 d | 36.93 ± 0.51 b | 96.83 ± 0.32 b | |

| 8 | 3.09 ± 0.06 e | 31.57 ± 0.81 a | 81.20 ± 0.70 a | |

| Microwave-vacuum | 0 | 0.46 ± 0.01 a | 142.80 ± 1.51 h | 329.67 ± 3.07 f |

| 2 | 1.02 ± 0.02 b | 49.17 ± 1.23 f | 152.97 ± 3.35 d | |

| 4 | 1.89 ± 0.02 c | 41.80 ± 0.70 d | 116.47 ± 0.93 c | |

| 6 | 2.20 ± 0.06 d | 37.83 ± 0.78 bc | 93.73 ± 1.79 b | |

| 8 | 2.93 ± 0.04 e | 32.50 ± 0.70 a | 77.67 ± 0.74 a | |

| Factor | Two-factor analysis of variance | |||

| p-value | ||||

| Drying method (DM) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.087 | |

| Green coffee flour (GCF) content | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| DM × GCF | 0.018 | 0.022 | 0.022 | |

| Sample | Gallic | Protocate Chuic | p-Coumaric | Salicylic | Chlorogenic | Crypto -Chlorogenic | Neochlorogenic | Caffeic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SE | nd | Trace | 200 ± 1 A | trace | 58,467 ± 701 A | 2871 ± 19 A | 2618 ± 10 A | trace |

| GCF | 317 ± 6 | 1997 ± 9 | 2973 ± 28 B | 648 ± 6 | 224,437 ± 4734 B | 91,460 ± 808 B | 165,477 ± 2831 B | 191,500 ± 527 |

| DM | GCF (%) | Gallic | Protocate- Chuic | p-Coumaric | Chlorogenic | Neochloro- Genic | Cryptochlorogenic | Caffeic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Convective | 0 | trace | nd | 327 ± 4 a | 58,063 ± 1045 a | 2503 ± 222 a | 2867 ± 96 a | trace |

| 2 | 42 ± 1 c | 886 ± 8 a | 692 ± 13 c | 184,319 ± 1799 c | 35,533 ± 311 c | 23506 ± 83 c | 12,792 ± 244 c | |

| 4 | 53 ± 2 d | 1007 ± 3 c | 773 ± 9 d | 213,004 ± 1994 f | 65,723 ± 891 d | 33,020 ± 285 d | 13,269 ± 48 e | |

| 6 | 86 ± 1 e | 1061 ± 7 d | 843 ± 8 e | 212,956 ± 1268 f | 65,861 ± 191 f | 37,216 ± 353 f | 13,962 ± 104 f | |

| 8 | 93 ± 2 f | 1077 ± 16 d | 903± 4 f | 211,366 ± 2174 f | 72,670 ± 306 g | 42,166 ± 312 h | 14,610 ± 189 d | |

| Microwave -vacuum | 0 | trace | nd | 303 ± 4 a | 60,352 ± 151 a | 2508 ± 50 a | 2717 ± 49 a | trace |

| 2 | 34 ± 1 b | trace | 567 ± 8 b | 177,167 ± 1041 b | 26,816 ± 509 b | 20,762 ± 411 b | 7915 ± 28 a | |

| 4 | 45 ± 2 c | 892 ± 7 a | 625 ± 18 c | 196,759 ± 1641 d | 54,130 ± 476 d | 30,419 ± 495 d | 8244 ± 144 a | |

| 6 | 30 ± 0 a | 956 ± 10 b | 790 ± 5 d | 199,705 ± 388 de | 50,946 ± 259 e | 32,378 ± 184 e | 10,632 ± 115 b | |

| 8 | 29 ± 1 a | 971 ± 6 b | 798 ± 12 d | 203,421 ± 2758 e | 79,355 ± 655 h | 39,911 ± 192 g | 10,567 ± 182 b | |

| Factor | Two-factor analysis of variance p-value | |||||||

| DM | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| GCF | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| DM × GCF | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Drying Method | GCF (%) | Taste | Smell | Color | Texture | OA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Convective | 0 | 8.3 ± 1.1 d | 8.2 ± 0.7 c | 8.5 ± 0.5 e | 8.3 ± 1.5 d | 8.3 ± 0.9 d |

| 2 | 6.7 ± 1.5 bcd | 6.9 ± 1.9 bc | 6.1 ± 1.6 cd | 7.3 ± 1.3 cd | 6.8 ± 0.9 cd | |

| 4 | 5.5 ± 1.7 abc | 6.3 ± 2.0 abc | 5.4 ± 1.8 bcd | 6.1 ± 1.3 bcd | 5.8 ± 1.2 bc | |

| 6 | 4.8 ± 2.3 abc | 5.5 ± 1.9 ab | 4.5 ± 2.1 abc | 5.1 ± 1.8 abc | 5.0 ± 1.6 ab | |

| 8 | 3.5 ± 2.5 a | 4.4 ± 2.5 a | 3.2 ± 1.9 a | 4.7 ± 1.9 ab | 3.9 ± 1.7 a | |

| Microwave-vacuum | 0 | 7.0 ± 2.0 cd | 6.1 ± 1.8 abc | 6.7 ± 2.4 de | 4.5 ± 2.8 ab | 6.1 ± 1.7 bc |

| 2 | 5.6 ± 2.0 abc | 6.5 ± 1.9 abc | 4.7 ± 1.9 abcd | 4.5 ± 2.5 ab | 5.3 ± 1.5 abc | |

| 4 | 4.7 ± 1.6 ab | 6.1 ± 1.8 abc | 4.3 ± 1.9 abc | 4.7 ± 2.4 ab | 5.0 ± 1.5 ab | |

| 6 | 3.3 ± 1.8 a | 4.7 ± 2.2 ab | 3.8 ± 1.8 ab | 3.4 ± 2.4 a | 3.8 ± 1.5 a | |

| 8 | 3.6 ± 2.8 a | 4.9 ± 2.6 ab | 3.5 ± 1.8 ab | 3.5 ± 2.3 a | 3.9 ± 1.8 a | |

| Factor | Two-factor analysis of variance p-value | |||||

| Drying method (DM) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Green coffee flour (GCF) content | 0.006 | 0.062 | 0.002 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| DM × GCF | 0.623 | 0.167 | 0.213 | 0.091 | 0.075 | |

| Compound | Retention Time (min) | [M-H]− (m/z) | Fragment Ions (m/z) | Colision Energy (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenolic acids | ||||

| Gallic acid | 5.16 | 168.7 | 78.9 124.9 | −36 −14 |

| 3-O-caffeoylquinic acid (neochlorogenic acid) | 6.9 | 353 | 191 178.9 | −3 −3 |

| Protocatechuic acid | 8.42 | 152.9 | 80.9 107.8 | −26 −38 |

| 5-caffeoylquinic acid (chlorogenic acid) | 9.30 10.42 | 352.9 | 190.8 84.9 | −24 −60 |

| 4-caffeoylquinic acid (cryptochlorogenic acid) | 9.4 | 353 | 173 135 | −3 −3 |

| 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid | 10.84 | 136.8 | 92.9 | −18 |

| Caffeic acid | 11.38 | 178.7 | 88.9 134.9 | −46 −16 |

| Syringic acid | 11.42 | 196.9 | 122.8 181.9 | −24 −12 |

| 4-Hydroxycinnamic acid (p-coumaric acid) | 14.10 | 162.7 | 119 93 | −14 −44 |

| Ferulic acid | 14.80 15.22 | 192.8 | 133.9 177.9 | −16 −12 |

| Salicylic acid | 17.91 | 136.8 | 93 75 | −16 −48 |

| Compound | LOD (ng/mL) | LOQ (ng/mL) | R2 | Linearity Range (ng/ mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenolic acids | ||||

| Gallic acid | 10 | 20 | 0.9995 | 20–18,500 |

| 3-O-caffeoylquinic acid (neochlorogenic acid) | 20 | 40 | 0.9996 | 40–10,000 |

| Protocatechuic acid | 200 | 400 | 0.9988 | 1890–18,900 |

| 5-caffeoylquinic acid (chlorogenic acid) | 72 | 180 | 0.9991 | 180–18,000 |

| 4-caffeoylquinic acid (cryptochlorogenic acid) | 20 | 40 | 0.9979 | 40–4000 |

| 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid | 200 | 250 | 0.9994 | 700–19,250 |

| Caffeic acid | 195 | 389 | 0.9991 | 389–19,500 |

| Syringic acid | 500 | 732 | 0.9993 | 732–18,300 |

| 4-Hydroxycinnamic acid (p-coumaric acid) | 83 | 200 | 0.9990 | 400–13,800 |

| Ferulic acid | 1250 | 1830 | 0.9985 | 1830–36,500 |

| Salicylic acid | 500 | 600 | 0.9984 | 600–18,000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dziki, D.; Cacak-Pietrzak, G.; Kopyto-Krzepicka, J.; Marzec, A.; Stępniewska, S.; Krajewska, A.; Dołomisiewicz, W.; Nowak, R.; Kanak, S. Wheat Pasta Enriched with Green Coffee Flour: Physicochemical, Antioxidant and Sensory Properties. Molecules 2025, 30, 4765. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244765

Dziki D, Cacak-Pietrzak G, Kopyto-Krzepicka J, Marzec A, Stępniewska S, Krajewska A, Dołomisiewicz W, Nowak R, Kanak S. Wheat Pasta Enriched with Green Coffee Flour: Physicochemical, Antioxidant and Sensory Properties. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4765. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244765

Chicago/Turabian StyleDziki, Dariusz, Grażyna Cacak-Pietrzak, Julia Kopyto-Krzepicka, Agata Marzec, Sylwia Stępniewska, Anna Krajewska, Wioleta Dołomisiewicz, Renata Nowak, and Sebastian Kanak. 2025. "Wheat Pasta Enriched with Green Coffee Flour: Physicochemical, Antioxidant and Sensory Properties" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4765. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244765

APA StyleDziki, D., Cacak-Pietrzak, G., Kopyto-Krzepicka, J., Marzec, A., Stępniewska, S., Krajewska, A., Dołomisiewicz, W., Nowak, R., & Kanak, S. (2025). Wheat Pasta Enriched with Green Coffee Flour: Physicochemical, Antioxidant and Sensory Properties. Molecules, 30(24), 4765. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244765