Recent Updates on Molecular and Physical Therapies for Organ Fibrosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Understanding the Pathophysiology of Organ Fibrosis

2.1. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Fibrosis

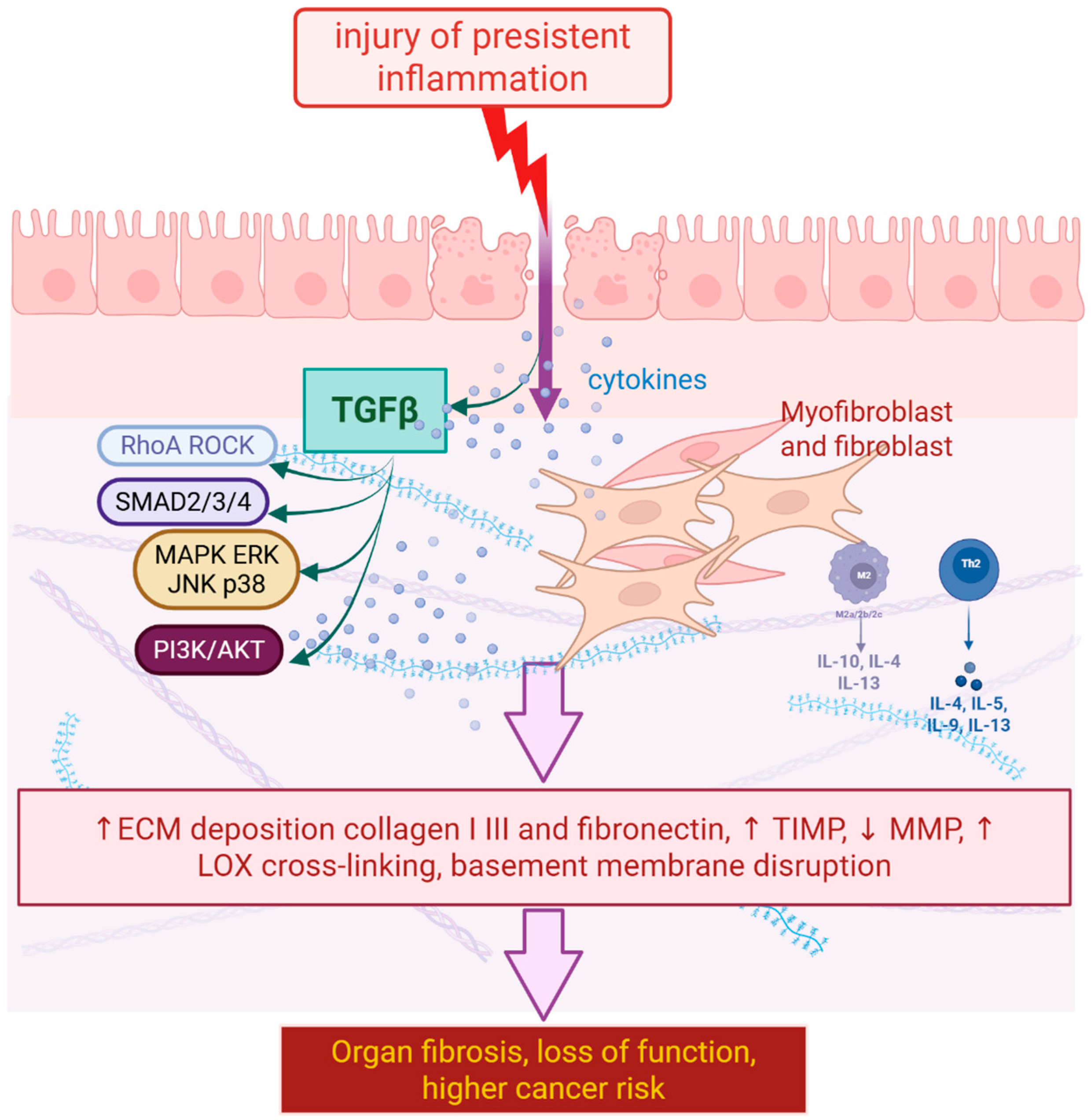

2.2. Role of Inflammation, Fibroblasts, and Extracellular Matrix Remodeling

2.3. Signaling Pathways as a Key Target

2.4. Non-Classical Mechanisms of Fibrosis: Metabolic and Epigenetic Reprogramming

3. Innovative Therapeutic Approaches

3.1. Small Molecule Inhibitors and Targeted Therapies

3.2. Biologics and Gene Therapies

3.3. Cell-Based Therapies

4. Preclinical and Clinical Studies

4.1. In Vitro and Animal Model Studies Evaluating Efficacy and Safety

4.2. Phase I–III Clinical Trials Assessing Novel Therapies in Patients

5. Biophysical and Nanomaterials-Based Antifibrotic Therapies

5.1. Magnetic Fields as an Antifibrotic Factor

5.2. Magnetic Nanocarriers for Targeted Antifibrotic Delivery

6. Future Directions and Challenges

6.1. Integration of Multi-Omics Approaches for Personalized Therapy

6.2. Development of Combination Therapies Targeting Multiple Pathways

6.3. Optimization of Drug Delivery Systems for Enhanced Efficacy and Specificity

6.4. Addressing Issues Related to Patient Heterogeneity and Disease Progression

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACEi | Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor |

| AD-MSCs | Adipose-derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells |

| ARB | Angiotensin II Receptor Blocker |

| BM-MSCs | Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells |

| BLM-induced PF | Bleomycin-induced Pulmonary Fibrosis |

| CCL | C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand |

| CLDN1 | Claudin-1 |

| CRISPR/dCas9 | Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats/Dead Cas9 |

| CTGF | Connective Tissue Growth Factor |

| ECM | Extracellular Matrix |

| EMT | Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition |

| EpCAM | Epithelial Cell Adhesion Molecule |

| ESDL | End-Stage Liver Disease |

| FVC | Forced Vital Capacity |

| FXR | Farnesoid X Receptor |

| HBV | Hepatitis B Virus |

| HCV | Hepatitis C Virus |

| HLFs | Human Lung Fibroblasts |

| HPS1 | Hermansky–Pudlak Syndrome 1 |

| ILD | Interstitial Lung Disease |

| IPF | Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis |

| iPSCs | Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells |

| LDL-C | Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol |

| MMPs | Matrix Metalloproteinases |

| MOFA | Multi-Omics Factor Analysis |

| MSC | Mesenchymal Stem Cell |

| OCA | Obeticholic Acid |

| PCNA | Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen |

| PF | Pulmonary Fibrosis |

| PFD | Pirfenidone |

| PPAR | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor |

| RAAS | Renin–Angiotensin–Aldosterone System |

| R-Smads | Receptor-regulated Smad proteins |

| TGF-β | Transforming Growth Factor Beta |

| TGF-βR | Transforming Growth Factor Beta Receptor |

| Th2 | T-helper 2 |

| TIMPs | Tissue Inhibitors of Metalloproteinases |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha |

| TNIK | Traf2- and Nck-interacting kinase |

| UC-MSCs | Umbilical Cord-derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells |

| UDCA | Ursodeoxycholic Acid |

| VCAM-1 | Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1 |

References

- Lurje, I.; Gaisa, N.T.; Weiskirchen, R.; Tacke, F. Mechanisms of Organ Fibrosis: Emerging Concepts and Implications for Novel Treatment Strategies. Mol. Asp. Med. 2023, 92, 101191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parola, M.; Pinzani, M. Pathophysiology of Organ and Tissue Fibrosis. Mol. Asp. Med. 2019, 65, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wynn, T.A.; Ramalingam, T.R. Mechanisms of Fibrosis: Therapeutic Translation for Fibrotic Disease. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 1028–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, N.C.; Rieder, F.; Wynn, T.A. Fibrosis: From Mechanisms to Medicines. Nature 2020, 587, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivpuri, A.; Sharma, S.; Trehan, M.; Hivpuri, A.S. Oral Submucous Fibrosis in a 10 Year Old Girl—Case Report. Dent. Med. Probl. 2013, 50, 85–87. [Google Scholar]

- DeLeon-Pennell, K.Y.; Barker, T.H.; Lindsey, M.L. Fibroblasts: The Arbiters of Extracellular Matrix Remodeling. Matrix Biol. 2020, 91–92, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.A.; Nelson, C.M. New Insights into the Regulation of Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition and Tissue Fibrosis. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2012, 294, 171–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockey, D.C.; Bell, P.D.; Hill, J.A. Fibrosis—A Common Pathway to Organ Injury and Failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 1138–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dees, C.; Chakraborty, D.; Distler, J.H.W. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms in Fibrosis. Exp. Dermatol. 2021, 30, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braga, T.T.; Agudelo, J.S.H.; Camara, N.O.S. Macrophages During the Fibrotic Process: M2 as Friend and Foe. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, R.T.; Feghali-Bostwick, C.A. Fibroblasts in Fibrosis: Novel Roles and Mediators. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 5, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M.F.; desJardins-Park, H.E.; Mascharak, S.; Borrelli, M.R.; Longaker, M.T. Understanding the Impact of Fibroblast Heterogeneity on Skin Fibrosis. Dis. Model. Mech. 2020, 13, dmm044164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damerau, A.; Rosenow, E.; Alkhoury, D.; Buttgereit, F.; Gaber, T. Fibrotic Pathways and Fibroblast-like Synoviocyte Phenotypes in Osteoarthritis. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1385006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayreuther, K.; Rodemann, H.P.; Francz, P.I.; Maier, K. Differentiation of Fibroblast Stem Cells. J. Cell Sci. Suppl. 1988, 1988, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antar, S.A.; Ashour, N.A.; Marawan, M.E.; Al-Karmalawy, A.A. Fibrosis: Types, Effects, Markers, Mechanisms for Disease Progression, and Its Relation with Oxidative Stress, Immunity, and Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannigan, K.L.; Nieves, K.M.; Szczepanski, H.E.; Serra, A.; Lee, J.W.; Alston, L.A.; Ramay, H.; Mani, S.; Hirota, S.A. The Pregnane X Receptor and Indole-3-Propionic Acid Shape the Intestinal Mesenchyme to Restrain Inflammation and Fibrosis. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 15, 765–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laudadio, I.; Carissimi, C.; Scafa, N.; Bastianelli, A.; Fulci, V.; Renzini, A.; Russo, G.; Oliva, S.; Vitali, R.; Palone, F.; et al. Characterization of Patient-Derived Intestinal Organoids for Modelling Fibrosis in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Res. 2024, 73, 1359–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Li, J.; Li, M.; Qi, G.; Wei, L.; Zhang, D. Nets in Fibrosis: Bridging Innate Immunity and Tissue Remodeling. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 137, 112516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsburgh, S.; Todryk, S.; Ramming, A.; Distler, J.H.W.; O’Reilly, S. Innate Lymphoid Cells and Fibrotic Regulation. Immunol. Lett. 2018, 195, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Cai, R.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Xiao, L.; Wang, C.; Wang, L. Macrophages in Organ Fibrosis: From Pathogenesis to Therapeutic Targets. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwanaga, T.; Chiba, T.; Nakamura, M.; Kaneko, T.; Ao, J.; Qiang, N.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, J.; Kogure, T.; Yumita, S.; et al. Miglustat, a Glucosylceramide Synthase Inhibitor, Mitigates Liver Fibrosis through TGF-β/Smad Pathway Suppression in Hepatic Stellate Cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2023, 642, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Lin, J.; Li, J.; Wang, M.; Yu, J.; Sun, J.; Tang, N.; Jiao, C.; Ma, J.; et al. Treg and Intestinal Myofibroblasts-Derived Amphiregulin Induced by TGF-β Mediates Intestinal Fibrosis in Crohn’s Disease. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasso, G.J.; Jaiswal, A.; Varma, M.; Laszewski, T.; Grauel, A.; Omar, A.; Silva, N.; Dranoff, G.; Porter, J.A.; Mansfield, K.; et al. Colon Stroma Mediates an Inflammation-Driven Fibroblastic Response Controlling Matrix Remodeling and Healing. PLoS Biol. 2022, 20, e3001532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Taboada, M.; Corrales, P.; Medina-Gómez, G.; Vila-Bedmar, R. Tackling the Effects of Extracellular Vesicles in Fibrosis. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2022, 101, 151221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Li, M.; Hou, P.; Wang, X.; Sun, Z.; Li, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Li, Y. Biofilm Dynamic Changes in Drip Irrigation Emitter Flow Channels Using Reclaimed Water. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 291, 108624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.; Kanda, H.; Zhu, F.; Okubo, M.; Koike, T.; Ohno, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Harima, Y.; Miyamichi, K.; Fukui, H.; et al. Sympathetic Overactivation Drives Colonic Eosinophil Infiltration Linked to Visceral Hypersensitivity in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, 20, 101658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enzerink, A.; Salmenperä, P.; Kankuri, E.; Vaheri, A. Clustering of Fibroblasts Induces Proinflammatory Chemokine Secretion Promoting Leukocyte Migration. Mol. Immunol. 2009, 46, 1787–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wu, W.; Liu, Q.; Wu, Q.; Ren, P.; Xi, X.; Liu, H.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Z.; et al. Specific Surface-Modified Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Trigger Complement-Dependent Innate and Adaptive Antileukaemia Immunity. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, T.; Nguyen-Tran, H.-H.; Trojanowska, M. Active Roles of Dysfunctional Vascular Endothelium in Fibrosis and Cancer. J. Biomed. Sci. 2019, 26, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.; Jung, H.J.; Kim, M.W.; Kang, J.-H.; Shin, D.; Jang, Y.-S.; Yoon, Y.S.; Oh, S.H. A Novel STAT3 Inhibitor, STX-0119, Attenuates Liver Fibrosis by Inactivating Hepatic Stellate Cells in Mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 513, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.M.; Nikolic-Paterson, D.J.; Lan, H.Y. TGF-β: The Master Regulator of Fibrosis. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2016, 12, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Félix, J.M.; González-Núñez, M.; López-Novoa, J.M. ALK1-Smad1/5 Signaling Pathway in Fibrosis Development: Friend or Foe? Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2013, 24, 523–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; An, J.N.; Hwang, J.H.; Lee, H.; Lee, J.P.; Kim, S.G. P38 MAPK Activity Is Associated with the Histological Degree of Interstitial Fibrosis in IgA Nephropathy Patients. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Q.; Gan, C.; Sun, M.; Xie, Y.; Liu, H.; Xue, T.; Deng, C.; Mo, C.; Ye, T. BRD4: An Effective Target for Organ Fibrosis. Biomark. Res. 2024, 12, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Chen, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhuo, T.; Liu, X. Advances in Novel Therapeutics for Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2025, 91, 102396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Dai, R.; Cheng, M.; Chen, Y.; Gao, Y.; Hong, X.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L. Metabolic Reprogramming and Renal Fibrosis: What Role Might Chinese Medicine Play? Chin. Med. 2024, 19, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, A.; Mann, D.A. Epigenetic Regulation of Liver Fibrosis. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2015, 39, S64–S68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulukan, B.; Sila Ozkaya, Y.; Zeybel, M. Advances in the Epigenetics of Fibroblast Biology and Fibrotic Diseases. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2019, 49, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Chen, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, S.; Xie, N. Immunometabolism Changes in Fibrosis: From Mechanisms to Therapeutic Strategies. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1243675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Jiang, L.; Long, M.; Wei, X.; Hou, Y.; Du, Y. Metabolic Reprogramming and Renal Fibrosis. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 746920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaud, L.; da Silveira, W.A.; Takamura, N.; Hardiman, G.; Feghali-Bostwick, C. Prominence of IL6, IGF, TLR, and Bioenergetics Pathway Perturbation in Lung Tissues of Scleroderma Patients With Pulmonary Fibrosis. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ung, C.Y.; Onoufriadis, A.; Parsons, M.; McGrath, J.A.; Shaw, T.J. Metabolic Perturbations in Fibrosis Disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2021, 139, 106073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, S.; Yuan, J.; Mao, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Dong, Q.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Tang, N. Tissue Regeneration: Unraveling Strategies for Resolving Pathological Fibrosis. Cell Stem Cell 2025, 32, 1639–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Zhuang, Q.; Zhao, M. Immune and Metabolic Alterations in Liver Fibrosis: A Disruption of Oxygen Homeostasis? Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 802251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, P.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Jia, S.; Jiang, X.; Chen, H.; Wang, Q. Advances in Precision Gene Editing for Liver Fibrosis: From Technology to Therapeutic Applications. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 177, 117003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Liu, M.; Zhang, L.; Fan, J.-J.; Fu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Y. Molecular Mechanisms and Targeted Intervention Strategies of Renal Tubular Epithelial Cell Glycolytic Reprogramming in Renal Fibrosis. Life Sci. 2026, 384, 124085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligresti, G.; Raslan, A.A.; Hong, J.; Caporarello, N.; Confalonieri, M.; Huang, S.K. Mesenchymal Cells in the Lung: Evolving Concepts and Their Role in Fibrosis. Gene 2023, 859, 147142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.-Q.; Yang, Y.; Tao, H.; Lu, C.; Yang, J.-J. M6A Epitranscriptomic and Epigenetic Crosstalk in Liver Fibrosis: Special Emphasis on DNA Methylation and Non-Coding RNAs. Cell. Signal. 2024, 122, 111302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonnell, F.; Irnaten, M.; Clark, A.F.; O’Brien, C.J.; Wallace, D.M. Hypoxia-Induced Changes in DNA Methylation Alter RASAL1 and TGFβ1 Expression in Human Trabecular Meshwork Cells. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, J.-B.; Cao, Y.; You, Q.-Y.; Liu, Z.-Y.; Wang, X.-C.; Ling, H.; Sha, J.-M.; Tao, H. The Landscape of Histone Modification in Organ Fibrosis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 977, 176748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wen, D.; Ho, C.; Yu, L.; Zheng, D.; O’Reilly, S.; Gao, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Y. Epigenetics as a Versatile Regulator of Fibrosis. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laduron, S.; Deplus, R.; Zhou, S.; Kholmanskikh, O.; Godelaine, D.; De Smet, C.; Hayward, S.D.; Fuks, F.; Boon, T.; De Plaen, E. MAGE-A1 Interacts with Adaptor SKIP and the Deacetylase HDAC1 to Repress Transcription. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 4340–4350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Schimenti, J.C.; Bolcun-Filas, E. A Mouse Geneticist’s Practical Guide to CRISPR Applications. Genetics 2015, 199, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Gao, J.; Chen, J.; Huang, Y.; Wang, L.; Lin, J.; Zhao, M.; Shen, Y.; Zhao, G.; Cheng, Y. Roles and Potential Mechanisms of Hepatic Stellate Cells Activation Mediated by Epigenetics through Insulin like Growth Factor 1 and Receptor: A Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 329, 147642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, Y.; Ye, W. Therapeutic Efficacy of Pirfenidone and Nintedanib in Pulmonary Fibrosis; a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann. Thorac. Med. 2025, 20, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meersseman, C.; Martínez Besteiro, E.; Romain-Scelle, N.; Crestani, B.; Marchand-Adam, S.; Nunes, H.; Wémeau-Stervinou, L.; Borie, R.; Diesler, R.; Valenzuela, C.; et al. Nintedanib Combined With Pirfenidone in Patients With Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis or Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Long-Term Retrospective Multicentre Study (Combi-PF). Arch. Bronconeumol. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Tan, Y.; Yang, T.; Xu, D.; Chen, M.; Chen, L. Efficacy and Safety of Antifibrotic Drugs for Interstitial Lung Diseases Other than IPF: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis and Trial Sequential Analysis. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0318877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargagli, E.; Piccioli, C.; Rosi, E.; Torricelli, E.; Turi, L.; Piccioli, E.; Pistolesi, M.; Ferrari, K.; Voltolini, L. Pirfenidone and Nintedanib in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Real-Life Experience in an Italian Referral Centre. Pulmonology 2019, 25, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-I.; Hossain, R.; Li, X.; Lee, H.J.; Lee, C.J. Searching for Novel Candidate Small Molecules for Ameliorating Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Narrative Review. Biomol. Ther. 2023, 31, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Li, G.; Wang, H.; Mo, C. Comprehensive Review of Potential Drugs with Anti-Pulmonary Fibrosis Properties. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 173, 116282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vistnes, M. Hitting the Target! Challenges and Opportunities for TGF-β Inhibition for the Treatment of Cardiac Fibrosis. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.N.; Le, P.H.; Yang, S.; Luong, T.; Kim, J. Rewiring the Scar: Translational Advances in Cardiac Fibrosis. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2025, 29, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgalla, G.; Flore, M.; Siciliano, M.; Richeldi, L. Antibody-Based Therapies for Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Expert. Opin. Biol. Ther. 2020, 20, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, S.; Alkhatib, A.; Kolls, J.K.; Kondoh, Y.; Lasky, J.A. Pharmacotherapy and Adjunctive Treatment for Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF). J. Thorac. Dis. 2019, 11, S1740–S1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roehlen, N.; Saviano, A.; El Saghire, H.; Crouchet, E.; Nehme, Z.; Del Zompo, F.; Jühling, F.; Oudot, M.A.; Durand, S.C.; Duong, F.H.T.; et al. A Monoclonal Antibody Targeting Nonjunctional Claudin-1 Inhibits Fibrosis in Patient-Derived Models by Modulating Cell Plasticity. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022, 14, eabj4221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Tong, X.; Liu, S.; Huang, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, T.; Wang, D.; Fan, H. AAV9-Tspyl2 Gene Therapy Retards Bleomycin-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis by Modulating Downstream TGF-β Signaling in Mice. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, N.; Zhong, W.; Li, J.; Lu, J.; Dong, R. CRISPR/DCas9 for Hepatic Fibrosis Therapy: Implications and Challenges. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 11403–11408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Alamilla, G.; Behan, M.; Hossain, M.; Gochuico, B.R.; Malicdan, M.C.V. Hermansky-Pudlak Syndrome: Gene Therapy for Pulmonary Fibrosis. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2022, 137, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, W.; Fan, C.; Song, Q.; Chen, P.; Peng, H.; Lin, L.; Liu, C.; Wang, B.; Zhou, Z. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Based Therapies for Organ Fibrosis. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1119606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouyanfard, S.; Meshgin, N.; Cruz, L.S.; Diggle, K.; Hashemi, H.; Pham, T.V.; Fierro, M.; Tamayo, P.; Fanjul, A.; Kisseleva, T.; et al. Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Macrophages Ameliorate Liver Fibrosis. Stem Cells 2021, 39, 1701–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Quan, Y.; Sun, H.; Peng, X.; Zou, Z.; Alcorn, J.L.; Wetsel, R.A.; Wang, D. A Site-Specific Genetic Modification for Induction of Pluripotency and Subsequent Isolation of Derived Lung Alveolar Epithelial Type II Cells. Stem Cells 2014, 32, 402–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Palomo, B.; Sanchez-Lopez, L.I.; Moodley, Y.; Edel, M.J.; Edel, M.J.; Edel, M.J.; Serrano-Mollar, A.; Serrano-Mollar, A. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Lung Alveolar Epithelial Type II Cells Reduce Damage in Bleomycin-Induced Lung Fibrosis. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Povero, D.; Pinatel, E.M.; Leszczynska, A.; Goyal, N.P.; Nishio, T.; Kim, J.; Kneiber, D.; de Araujo Horcel, L.; Eguchi, A.; Ordonez, P.M.; et al. Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Reduce Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation and Liver Fibrosis. JCI Insight 2019, 5, e125652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Gao, Y.; Tan, M.; Zheng, R.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, X. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Conditioned Medium Suppresses Pulmonary Fibroblast-to-Myofibroblast Differentiation via the Inhibition of TGF-Β1/Smad Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 41, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, F.; Aliper, A.; Chen, J.; Zhao, H.; Rao, S.; Kuppe, C.; Ozerov, I.V.; Zhang, M.; Witte, K.; Kruse, C.; et al. A Small-Molecule TNIK Inhibitor Targets Fibrosis in Preclinical and Clinical Models. Nat. Biotechnol. 2024, 43, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, Q.; Wang, J.; Xu, C.; Huang, X.; Ruan, Z.; Dai, Y. Pirfenidone Alleviates Pulmonary Fibrosis in Vitro and in Vivo through Regulating Wnt/GSK-3β/β-Catenin and TGF-Β1/Smad2/3 Signaling Pathways. Mol. Med. 2020, 26, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Li, Q.; Liu, W.; Zong, C.; Wei, L.; Shi, Y.; Han, Z. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in Hepatic Fibrosis/Cirrhosis: From Pathogenesis to Treatment. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2023, 20, 583–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix, R.G.; Bovolato, A.L.C.; Cotrim, O.S.; Leão, P.D.S.; Batah, S.S.; Golim, M.d.A.; Velosa, A.P.; Teodoro, W.; Martins, V.; Cruz, F.F.; et al. Adipose-Derived Stem Cells and Adipose-Derived Stem Cell-Conditioned Medium Modulate in Situ Imbalance between Collagen I- and Collagen V-Mediated IL-17 Immune Response Recovering Bleomycin Pulmonary Fibrosis. Histol. Histopathol. 2020, 35, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behr, J.; Prasse, A.; Kreuter, M.; Johow, J.; Rabe, K.F.; Bonella, F.; Bonnet, R.; Grohe, C.; Held, M.; Wilkens, H.; et al. Pirfenidone in Patients with Progressive Fibrotic Interstitial Lung Diseases Other than Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (RELIEF): A Double-Blind, Randomised, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 2b Trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021, 9, 476–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voelker, J.; Berg, P.H.; Sheetz, M.; Duffin, K.; Shen, T.; Moser, B.; Greene, T.; Blumenthal, S.S.; Rychlik, I.; Yagil, Y.; et al. Anti-TGF-β 1 Antibody Therapy in Patients with Diabetic Nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 28, 953–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincenti, F.; Fervenza, F.C.; Campbell, K.N.; Diaz, M.; Gesualdo, L.; Nelson, P.; Praga, M.; Radhakrishnan, J.; Sellin, L.; Singh, A.; et al. A Phase 2, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Randomized Study of Fresolimumab in Patients With Steroid-Resistant Primary Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. Rep. 2017, 2, 800–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrangi, E.; Feizollahi, M.; Zare, S.; Goodarzi, A.; Ghasemi, M.R.; Sadeghzadeh-Bazargan, A.; Dehghani, A.; Nouri, M.; Zeinali, R.; Roohaninasab, M.; et al. Evaluation of the Efficacy of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Derived Conditioned Medium in the Treatment of Striae Distensae: A Double Blind Randomized Clinical Trial. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yang, Y.; Fan, L.; Zhang, F.; Li, L. The Clinical Application of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Liver Disease: The Current Situation and Potential Future. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suk, K.T.; Yoon, J.H.; Kim, M.Y.; Kim, C.W.; Kim, J.K.; Park, H.; Hwang, S.G.; Kim, D.J.; Lee, B.S.; Lee, S.H.; et al. Transplantation with Autologous Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Alcoholic Cirrhosis: Phase 2 Trial. Hepatology 2016, 64, 2185–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, H.; Zekri, A.R.N.; Medhat, E.; Al Alim, S.A.; Ahmed, O.S.; Bahnassy, A.A.; Lotfy, M.M.; Ahmed, R.; Musa, S. Peripheral Vein Infusion of Autologous Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Egyptian HCV-Positive Patients with End-Stage Liver Disease. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2014, 5, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Lin, H.; Shi, M.; Xu, R.; Fu, J.; Lv, J.; Chen, L.; Lv, S.; Li, Y.; Yu, S.; et al. Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells Improve Liver Function and Ascites in Decompensated Liver Cirrhosis Patients. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 27, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staab-Weijnitz, C.A. Fighting the Fiber: Targeting Collagen in Lung Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2022, 66, 363–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eftekhari, A.; Arjmand, A.; Asheghvatan, A.; Švajdlenková, H.; Šauša, O.; Abiyev, H.; Ahmadian, E.; Smutok, O.; Khalilov, R.; Kavetskyy, T.; et al. The Potential Application of Magnetic Nanoparticles for Liver Fibrosis Theranostics. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 674786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Pei, G.; Shen, J.; Fang, Z.; Chen, T.; Wang, L.; Cheng, H.; Li, H.; Pei, H.; Feng, Q.; et al. Pulsed Electromagnetic Fields Treatment Ameliorates Cardiac Function after Myocardial Infarction in Mice and Pigs. J. Adv. Res. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koura, G.M.R.; Elshiwi, A.M.F.; Alshahrani, M.S.; Elimy, D.A.; Alshahrani, R.A.N.; Alfaya, F.F.; Alshehri, S.H.S.; Hadi, A.A.; Alshehri, M.A.; Alnakhli, H.H.; et al. Effectiveness of Electromagnetic Field Therapy in Mechanical Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Pain. Res. 2025, 18, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Yu, T.; Chai, X.; Zhang, S.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Yin, D.; Zhang, C. Gradient Rotating Magnetic Fields Impairing F-Actin-Related Gene CCDC150 to Inhibit Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Metastasis by Inactivating TGF-Β1/SMAD3 Signaling Pathway. Research 2024, 7, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawitz, E.J.; Shevell, D.E.; Tirucherai, G.S.; Du, S.; Chen, W.; Kavita, U.; Coste, A.; Poordad, F.; Karsdal, M.; Nielsen, M.; et al. BMS-986263 in Patients with Advanced Hepatic Fibrosis: 36-week Results from a Randomized, Placebo-controlled Phase 2 Trial. Hepatology 2021, 75, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Wu, B.; Guo, X.; Shi, D.; Xia, H.; Xu, H.; Liu, X. Galangin Delivered by Retinoic Acid-Modified Nanoparticles Targeted Hepatic Stellate Cells for the Treatment of Hepatic Fibrosis. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 10987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ten Hove, M.; Smyris, A.; Booijink, R.; Wachsmuth, L.; Hansen, U.; Alic, L.; Faber, C.; Höltke, C.; Bansal, R. Engineered SPIONs Functionalized with Endothelin a Receptor Antagonist Ameliorate Liver Fibrosis by Inhibiting Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 39, 406–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, S.; Hallali, N.; Lalatonne, Y.; Hillion, A.; Antunes, J.C.; Serhan, N.; Clerc, P.; Fourmy, D.; Motte, L.; Carrey, J.; et al. Magneto-Mechanical Destruction of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Using Ultra-Small Iron Oxide Nanoparticles and Low Frequency Rotating Magnetic Fields. Nanoscale Adv. 2021, 4, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattaroni, C.; Begka, C.; Cardwell, B.; Jaffar, J.; Macowan, M.; Harris, N.L.; Westall, G.P.; Marsland, B.J. Multi-Omics Integration Reveals a Nonlinear Signature That Precedes Progression of Lung Fibrosis. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 2024, 13, e1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, P.; Todd, J.L.; Zhao, H.; Liu, Y.; Vinisko, R.; Soellner, J.F.; Schmid, R.; Kaner, R.J.; Luckhardt, T.R.; Neely, M.L.; et al. Integrative Multi-Omics Analysis Reveals Novel Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Endotypes Associated with Disease Progression. Respir. Res. 2023, 24, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhou, Z.C.; Yan, Y.; Wu, S.Z.; Ma, T.; Xuan, H.; Wang, R.C.; Gu, C.Y.; Liu, Y.H.; Liu, Q.Q.; et al. Characterization of Aggrephagy-Related Genes to Predict the Progression of Liver Fibrosis from Multi-Omics Profiles. Biomed. Technol. 2024, 5, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy, S.; Mariani, L.H.; Kretzler, M. Integrated Multi-Omics Approaches to Improve Classification of Chronic Kidney Disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2020, 16, 657–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Wang, L.; Wang, M.; Zhou, S.; Lu, Y.; Cui, H.; Racanelli, A.C.; Zhang, L.; Ye, T.; Ding, B.; et al. Targeting Fibrosis, Mechanisms and Cilinical Trials. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuyts, W.A.; Antoniou, K.M.; Borensztajn, K.; Costabel, U.; Cottin, V.; Crestani, B.; Grutters, J.C.; Maher, T.M.; Poletti, V.; Richeldi, L.; et al. Combination Therapy: The Future of Management for Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis? Lancet Respir. Med. 2014, 2, 933–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Wang, X.; Jin, Y.; Zhou, L.; Ye, J. Progress of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) & MSC-Exosomes Combined with Drugs Intervention in Liver Fibrosis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 176, 116848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuppan, D.; Kim, Y.O. Evolving Therapies for Liver Fibrosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 1887–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.-D.; Zhou, J.; Chen, E.Q. Molecular Mechanisms and Potential New Therapeutic Drugs for Liver Fibrosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 787748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonella, F.; Spagnolo, P.; Ryerson, C. Current and Future Treatment Landscape for Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Drugs 2023, 83, 1581–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancheri, C.; Kreuter, M.; Richeldi, L.; Ryerson, C.J.; Valeyre, D.; Grutters, J.C.; Wiebe, S.; Stansen, W.; Quaresma, M.; Stowasser, S.; et al. Nintedanib with Add-on Pirfenidone in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Results of the INJOURNEY Trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 197, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaherty, K.R.; Fell, C.D.; Huggins, J.T.; Nunes, H.; Sussman, R.; Valenzuela, C.; Petzinger, U.; Stauffer, J.L.; Gilberg, F.; Bengus, M.; et al. Safety of Nintedanib Added to Pirfenidone Treatment for Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2018, 52, 1800230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Q.; Bao, H.; Wang, J.; Shi, W.; Zou, X.; Sheng, J.; Gao, J.; Guan, C.; Xia, H.; Li, J.; et al. Liver Fibrosis and MAFLD: The Exploration of Multi-Drug Combination Therapy Strategies. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1120621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pockros, P.J.; Fuchs, M.; Freilich, B.; Schiff, E.; Kohli, A.; Lawitz, E.J.; Hellstern, P.A.; Owens-Grillo, J.; Van Biene, C.; Shringarpure, R.; et al. CONTROL: A Randomized Phase 2 Study of Obeticholic Acid and Atorvastatin on Lipoproteins in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Patients. Liver Int. 2019, 39, 2082–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-Félix, J.M.; González-Núñez, M.; Martínez-Salgado, C.; López-Novoa, J.M. TGF-β/BMP Proteins as Therapeutic Targets in Renal Fibrosis. Where Have We Arrived after 25 Years of Trials and Tribulations? Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 156, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Pan, Z. Ovarian Fibrosis: Mechanistic Insights and Emerging Therapeutic Horizons. Gene 2025, 940, 149190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, K.; Wang, Y.; Lou, P.; Liu, S.; Zhou, P.; Yang, L.; Lu, Y.; Cheng, J.; Liu, J. Extracellular Vesicles as Advanced Therapeutics for the Resolution of Organ Fibrosis: Current Progress and Future Perspectives. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1042983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, Z.; Chaurasia, A.; Neha; Sharma, N.; Bachheti, R.K.; Gupta, P.C. Exploring Inflammatory and Fibrotic Mechanisms Driving Diabetic Nephropathy Progression. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev. 2025, 84, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macias-Ceja, D.C.; Mendoza-Ballesteros, M.T.; Ortega-Albiach, M.; Barrachina, M.D.; Ortiz-Masià, D. Role of the Epithelial Barrier in Intestinal Fibrosis Associated with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Relevance of the Epithelial-to Mesenchymal Transition. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1258843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Song, Y.; Wei, L.; Guo, J.; Xu, W.; Li, M. The Emerging Roles of Ferroptosis in Organ Fibrosis and Its Potential Therapeutic Effect. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 116, 109812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Z.-H.; Wang, X.-H.; Zhao, Y.; Ou, Y.; Yang, J.-Y.; Tang, H.-F.; Hu, H.-J. Ferroptosis in Organ Fibrosis: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Approaches. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2025, 151, 114341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Wu, K.; Jiang, X.; Gao, Y.; Ding, D.; Wang, H.; Yu, C.; Wang, X.; Jia, N.; Zhu, L. The Role of Ferroptosis-Related Non-Coding RNA in Liver Fibrosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1517401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, L.; Lin, L.-C.; Mao, S.; Liu, Z.-Y.; Liu, P.; Li, R.; Tao, H.; Zhang, Y. Piezo-Mediated Mechanically Activated Currents in Organ Fibrosis: Novel Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies. Life Sci. 2025, 382, 124050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikami, Y.; Takada, Y.; Hagihara, Y.; Kanai, T. Innate Lymphoid Cells in Organ Fibrosis. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev. 2018, 42, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, M.; Zhang, Y.; Song, X.; Xu, B. The Role and Mechanism of TXNDC5 in Disease Progression. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1354952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.-N.; Yang, Q.; Shen, X.-L.; Yu, W.-K.; Zhou, L.; Zhu, Q.-R.; Shan, Q.-Y.; Wang, Z.-C.; Cao, G. Targeting Tumor Suppressor P53 for Organ Fibrosis Therapy. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramachandran, P.; Henderson, N.C. Antifibrotics in Chronic Liver Disease: Tractable Targets and Translational Challenges. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 1, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Dang, Y.; Liu, M.; Gao, L.; Lin, H. Fibroblasts in Heterotopic Ossification: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targets. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2025, 21, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Blasio, M.J.; Ohlstein, E.H.; Ritchie, R.H. Therapeutic Targets of Fibrosis: Translational Advances and Current Challenges. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 180, 2839–2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Cheng, H.; Dai, R.; Shang, L.; Zhang, X.; Wen, H. Macrophage Polarization in Tissue Fibrosis. PeerJ 2023, 11, e16092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Ma, Z.; Jiang, S.; Fan, C.; Deng, C.; Yan, X.; Di, S.; Lv, J.; Reiter, R.J.; Yang, Y. Melatonin: The Dawning of a Treatment for Fibrosis? J. Pineal Res. 2016, 60, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacke, F.; Zimmermann, H.W. Macrophage Heterogeneity in Liver Injury and Fibrosis. J. Hepatol. 2014, 60, 1090–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mechanism | Key Features/Pathways | Therapeutic Strategies | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Reprogramming | Glycolysis, lipid/amino acid metabolism, mitochondrial dysfunction, lactate lactylation | Glycolytic enzyme inhibitors, mitochondrial repair, metabolic pathway modulators | Preclinical/experimental [36,40,41,46] |

| Epigenetic Regulation | DNA methylation, histone modification, ncRNAs, m6A modification | DNMT/HDAC inhibitors, ncRNA/CRISPR-based editing, m6A targeting | Preclinical, limited clinical translation [38,43,48,50,53,54] |

| Drug/Method Name | Mechanism | Class | Target Disease | Phase | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nintedanib | Inhibitor of differentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts, their migration and proliferation | Small molecule | Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) | Approved | [59,60] |

| Pirfenidone | Inhibitor of TGF-β | Small molecule | Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) | Approved | [59,60] |

| Lisinopril | Inhibitor of angiotensin converting enzyme -> inhibitor of angiotensin II and TGF-β1 | Small molecule | Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), an organ fibrosis | Research | [60] |

| Metformin | Activation of AMPK pathways, inhibition of TGF-β signaling, reduction in collagen and fibronectin production, deactivation of myofibroblasts, and suppression of macrophage and fibroblast activation | Small molecule | Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), an organ fibrosis | Research | [60] |

| INS018_055 | TNIK inhibitor | Small molecule inhibitor generated by AI-based design | Organ fibrosis | Completed Phase I clinical trials | [75] |

| Pamrevlumab | Human antibody against CTGF | Monoclonal antibody | Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) | Phase 3 RCT | [63,64] |

| BG00011 | Anti-αvβ6 integrin monoclonal antibody | Monoclonal antibody | Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) | 2a randomized, placebo-controlled trial | [63,64] |

| Lebrikizumab | Monoclonal antibody to IL-13 | Monoclonal antibody | Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) | Research | [3,4] |

| Therapeutic antibodies to TGF-β1 | activates myofibroblasts and humanized monoclonal antibody targeting lysyl oxidase-like-2 (catalyzes the cross-linking of collagen) | Monoclonal antibody | cardiac fibrosis, IPF and liver fibrosis | Clinical trial | [65] |

| Human monoclonal antibody to CCL2 | Recruits inflammatory monocytes | Monoclonal antibody | Organ fibrosis | Phase 1 | [65] |

| AAV9-Tspyl2 gene therapy | Restores cell division autoantigen-1 (CDA1) expression | Gene therapy | Renal fibrosis | Research | [66] |

| CRISPR/dCas9 system | Acts on liver fibrosis effector cells | Gene therapy | Liver fibrosis | Research | [67] |

| Pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) | Differentiates into specific cell types, blocks the TGF-β/Smad pathway | Cell | Organ fibrosis | Research | [69,70,71,72,73,74] |

| Substance/Treatment | Key Findings and Effects | References |

|---|---|---|

| Pirfenidone | Reduces inflammation, fibroblast activity, and collagen deposition; improves alveolar structure | [76,79] |

| Gene-Modified MSCs | Enhance anti-inflammatory effects, reduce fibrosis markers, and promote tissue regeneration | [77] |

| AD-MSCs and Conditioned Medium | Reduce inflammation and fibrosis markers; CM is slightly more effective than MSCs | [78] |

| Anti-TGF-β Antibodies | Fresolimumab and similar antibodies show no significant improvement in fibrosis outcomes | [80,81] |

| Microneedling + CM | Improves skin thickness and density; increases patient satisfaction | [82] |

| BM-MSCs and UC-MSCs (Liver Use) | Improve liver function in fibrosis and cirrhosis; minimal tumorigenesis risk | [83,84,85,86] |

| Strategy/Target | Mechanism/Pathway | Organ/System(s) | Status/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| TGF-β inhibitors | TGF-β signaling | Multiple | Developed, some approved [32,54,110,111,112] |

| RAAS blockers, antioxidants | Profibrotic/inflammatory | Kidney, others | Under investigation [113,114] |

| NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitors | Inflammation | Ovary | Developing [112] |

| Ferroptosis pathway inhibitors | Lipid peroxidation/cell death | Lung, heart, liver, kidney | Promising, drugs identified [115,116,117] |

| Piezo channel inhibitors | Mechanosensitive signaling | Multiple | Basic research stage [118] |

| Wnt pathway inhibitors | Wnt/β-catenin signaling | Liver | Preclinical/clinical [45] |

| IL-13/IL-4 pathway inhibitors | Immune modulation | Lung, IBD, others | Mixed results [119] |

| ECM degradation, myofibroblast elimination | ECM remodeling, cell targeting | Multiple | Clinical trials ongoing [112,114] |

| TXNDC5 deletion | Molecular target | Multiple | Potential strategy [120] |

| p53 targeting | Cell-type specific modulation | Multiple | Investigational [121] |

| miRNA-based therapies | Gene regulation | Multiple | Emerging [113,117] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Filipski, M.; Libergal, N.; Mikołajczyk, M.; Sznajderowicz, D.; Novickij, V.; Želvys, A.; Malakauskaitė, P.; Michel, O.; Kulbacka, J.; Choromańska, A. Recent Updates on Molecular and Physical Therapies for Organ Fibrosis. Molecules 2025, 30, 4766. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244766

Filipski M, Libergal N, Mikołajczyk M, Sznajderowicz D, Novickij V, Želvys A, Malakauskaitė P, Michel O, Kulbacka J, Choromańska A. Recent Updates on Molecular and Physical Therapies for Organ Fibrosis. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4766. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244766

Chicago/Turabian StyleFilipski, Michał, Natalia Libergal, Maksymilian Mikołajczyk, Daria Sznajderowicz, Vitalij Novickij, Augustinas Želvys, Paulina Malakauskaitė, Olga Michel, Julita Kulbacka, and Anna Choromańska. 2025. "Recent Updates on Molecular and Physical Therapies for Organ Fibrosis" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4766. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244766

APA StyleFilipski, M., Libergal, N., Mikołajczyk, M., Sznajderowicz, D., Novickij, V., Želvys, A., Malakauskaitė, P., Michel, O., Kulbacka, J., & Choromańska, A. (2025). Recent Updates on Molecular and Physical Therapies for Organ Fibrosis. Molecules, 30(24), 4766. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244766