Recent Advances in Synthetic Isoquinoline-Based Derivatives in Drug Design

Abstract

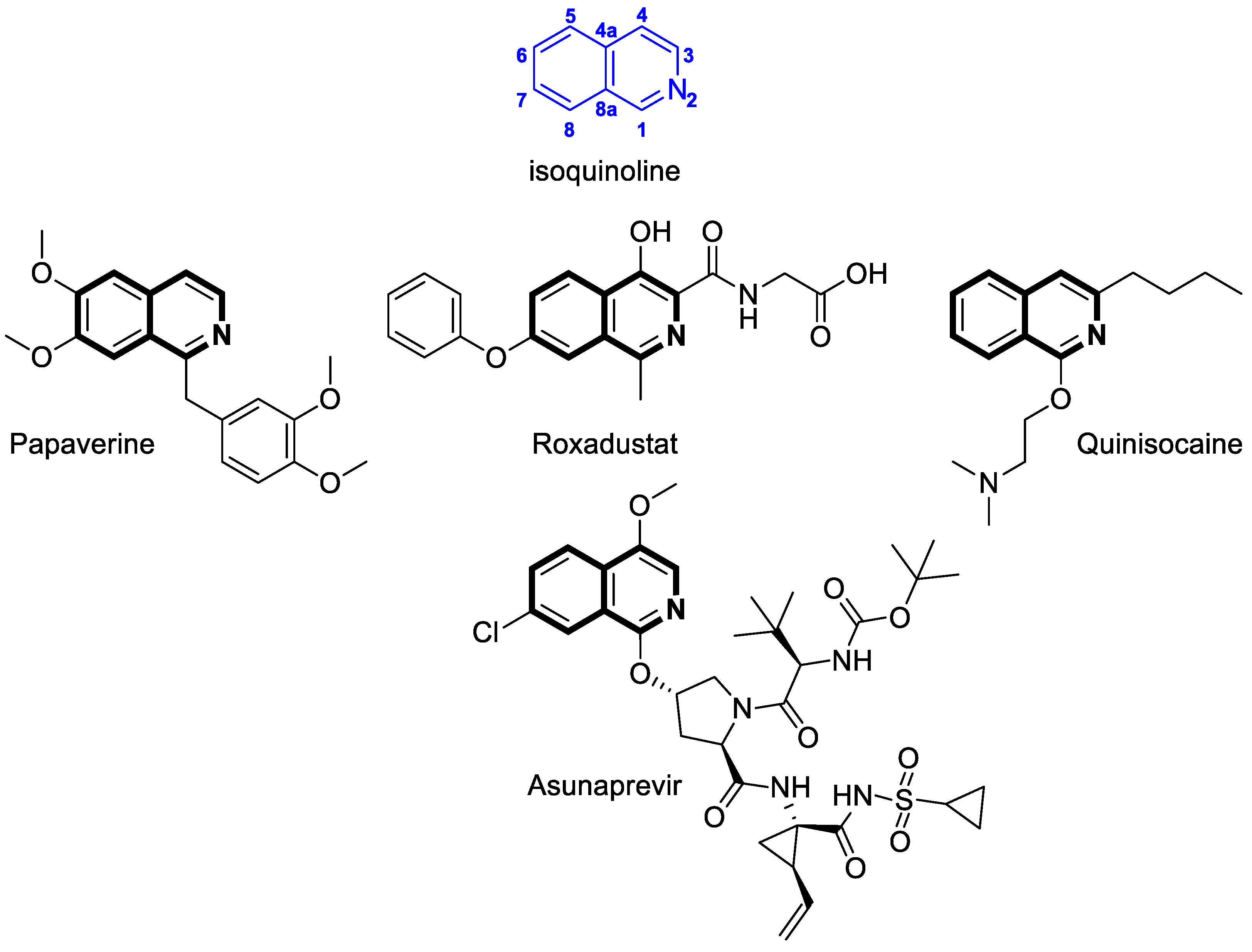

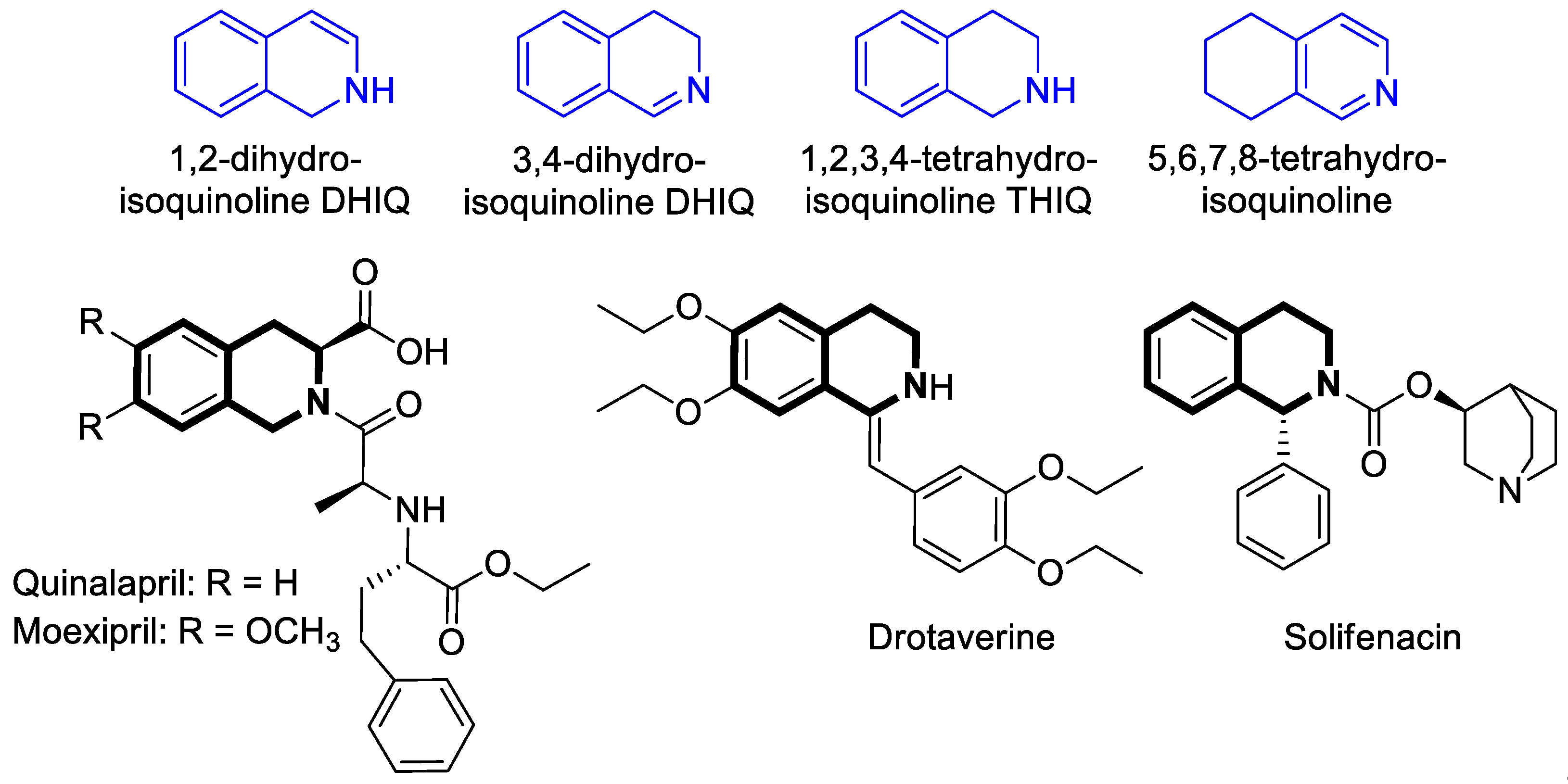

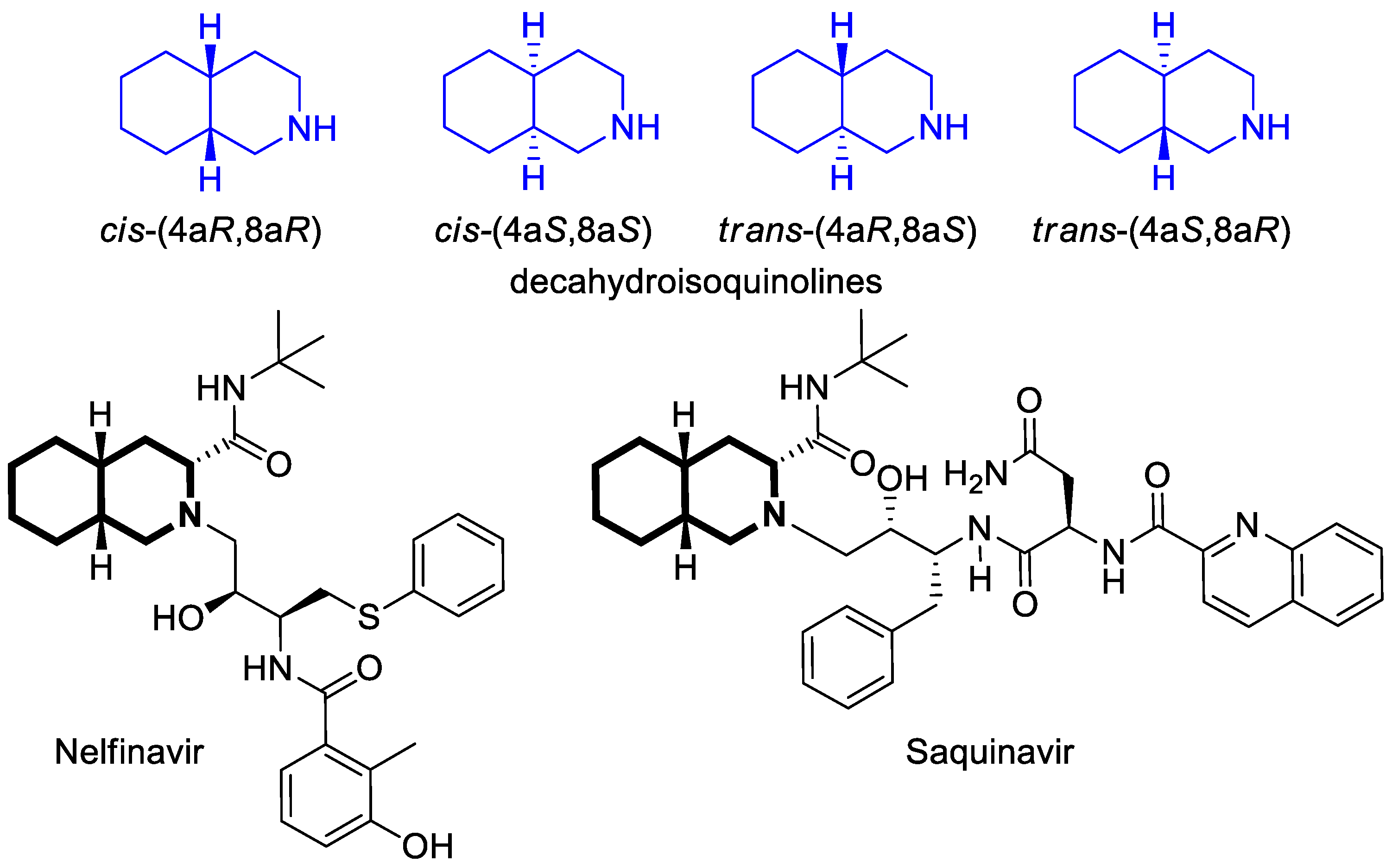

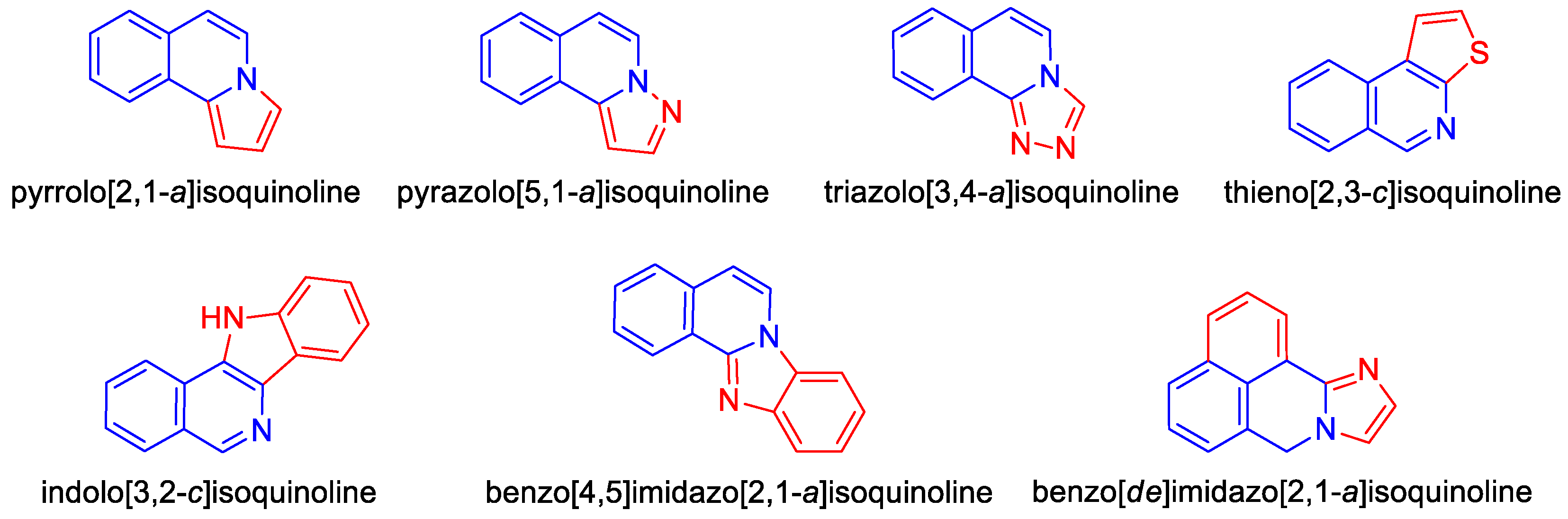

1. Introduction

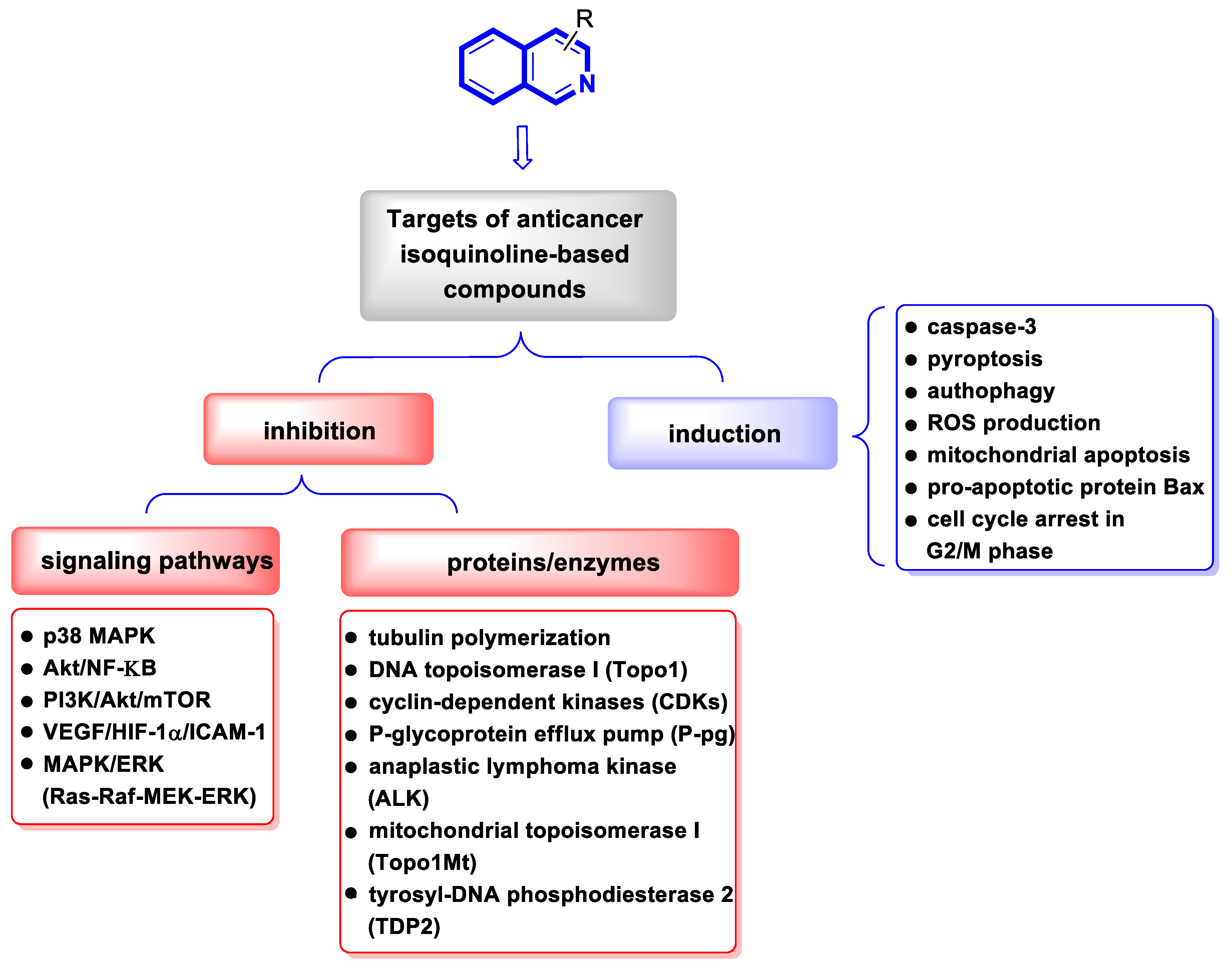

2. Chemotherapeutic Activity

2.1. Anticancer Agents

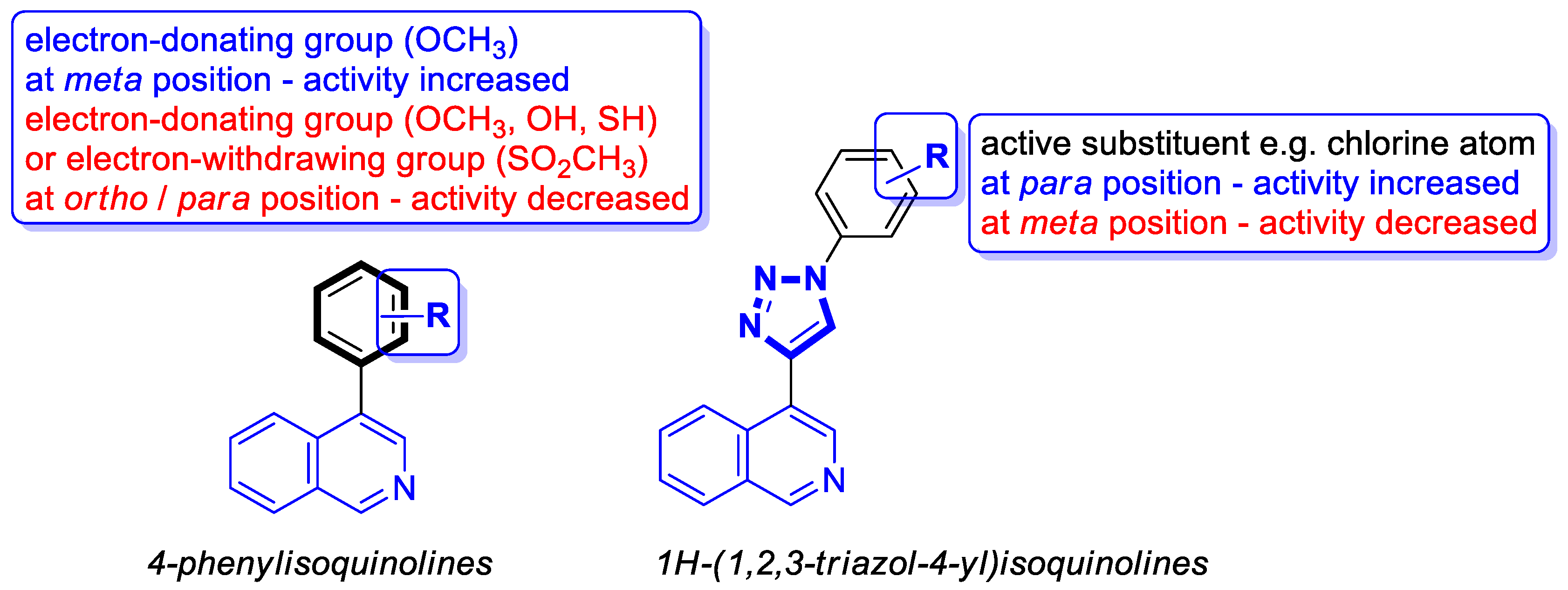

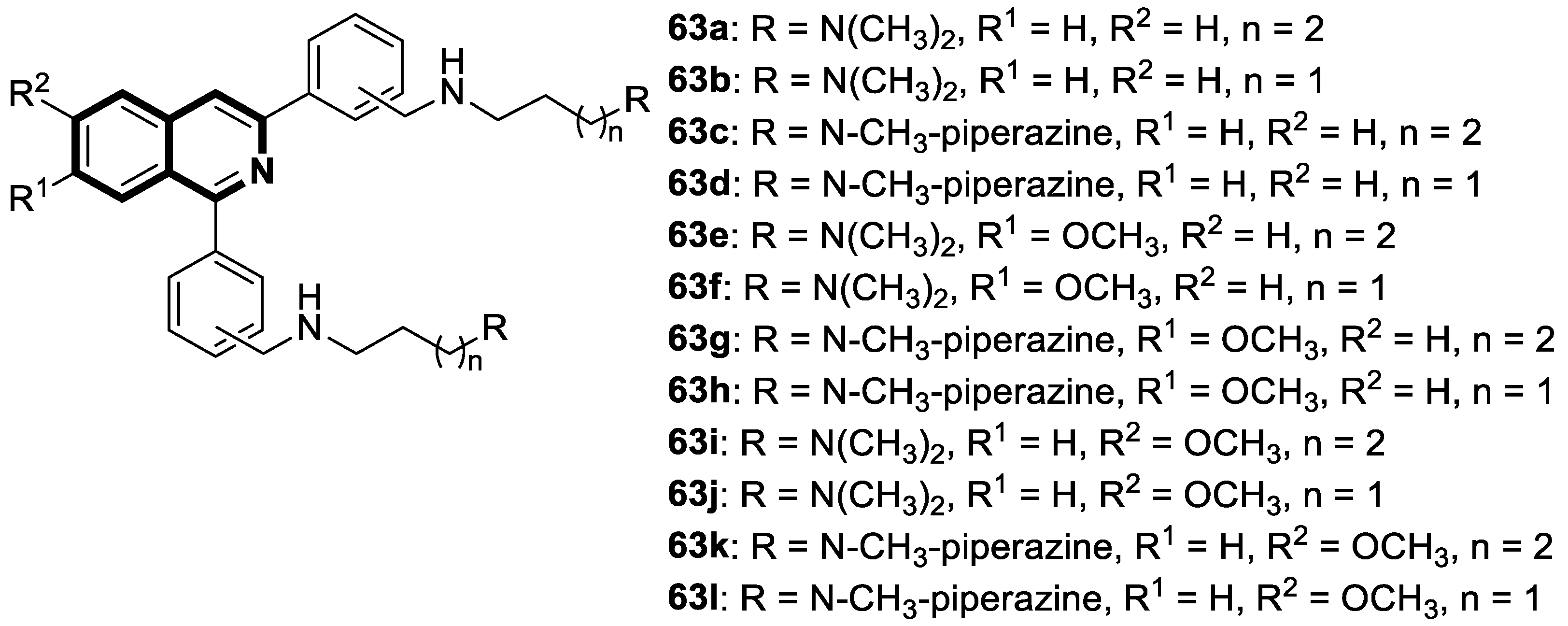

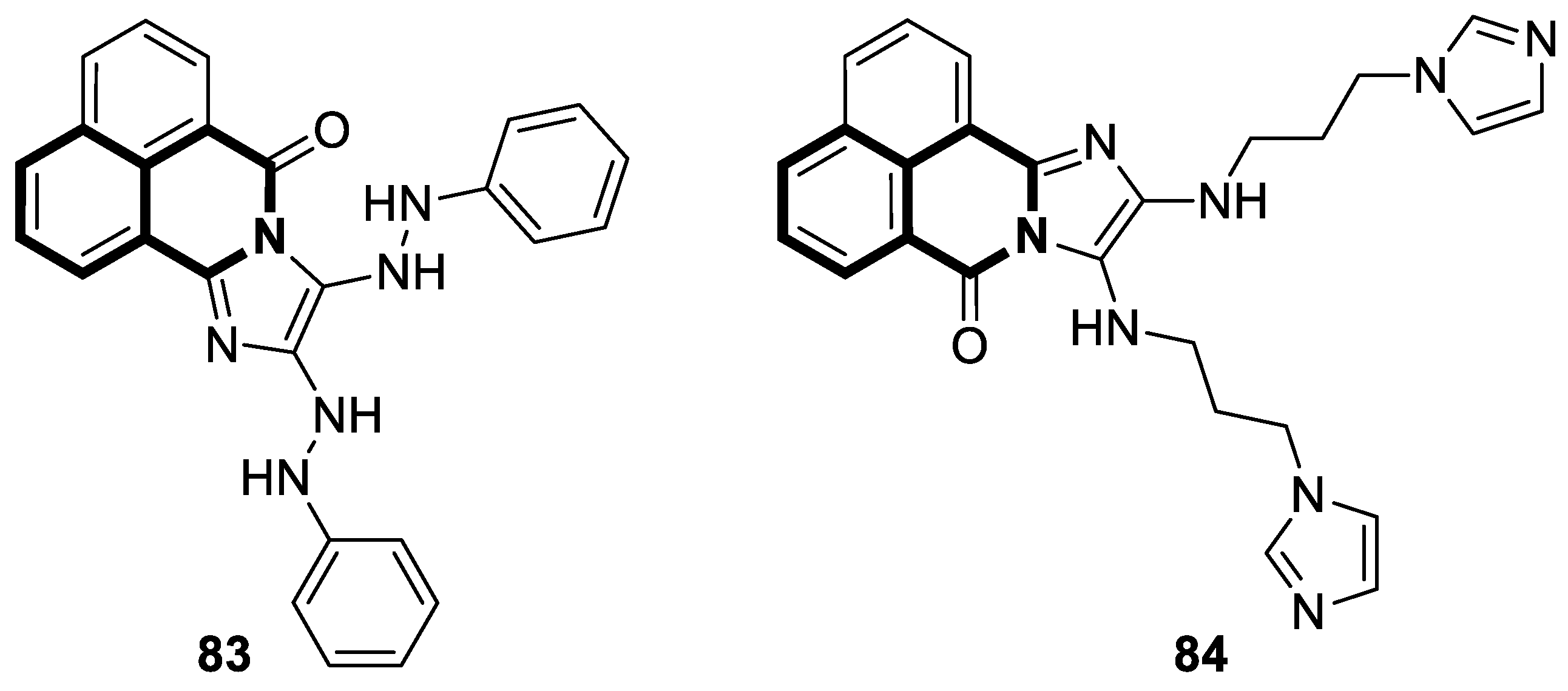

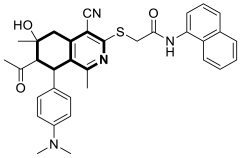

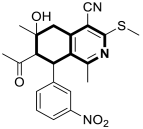

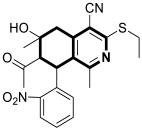

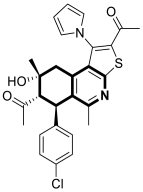

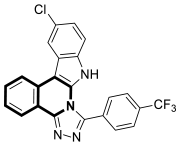

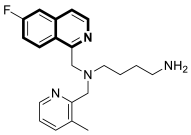

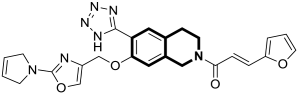

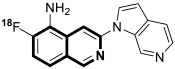

2.1.1. Isoquinoline-Based Compounds

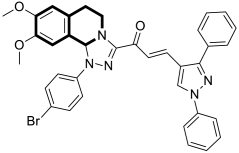

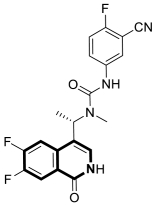

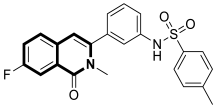

2.1.2. Dihydroisoquinoline-Based Compounds

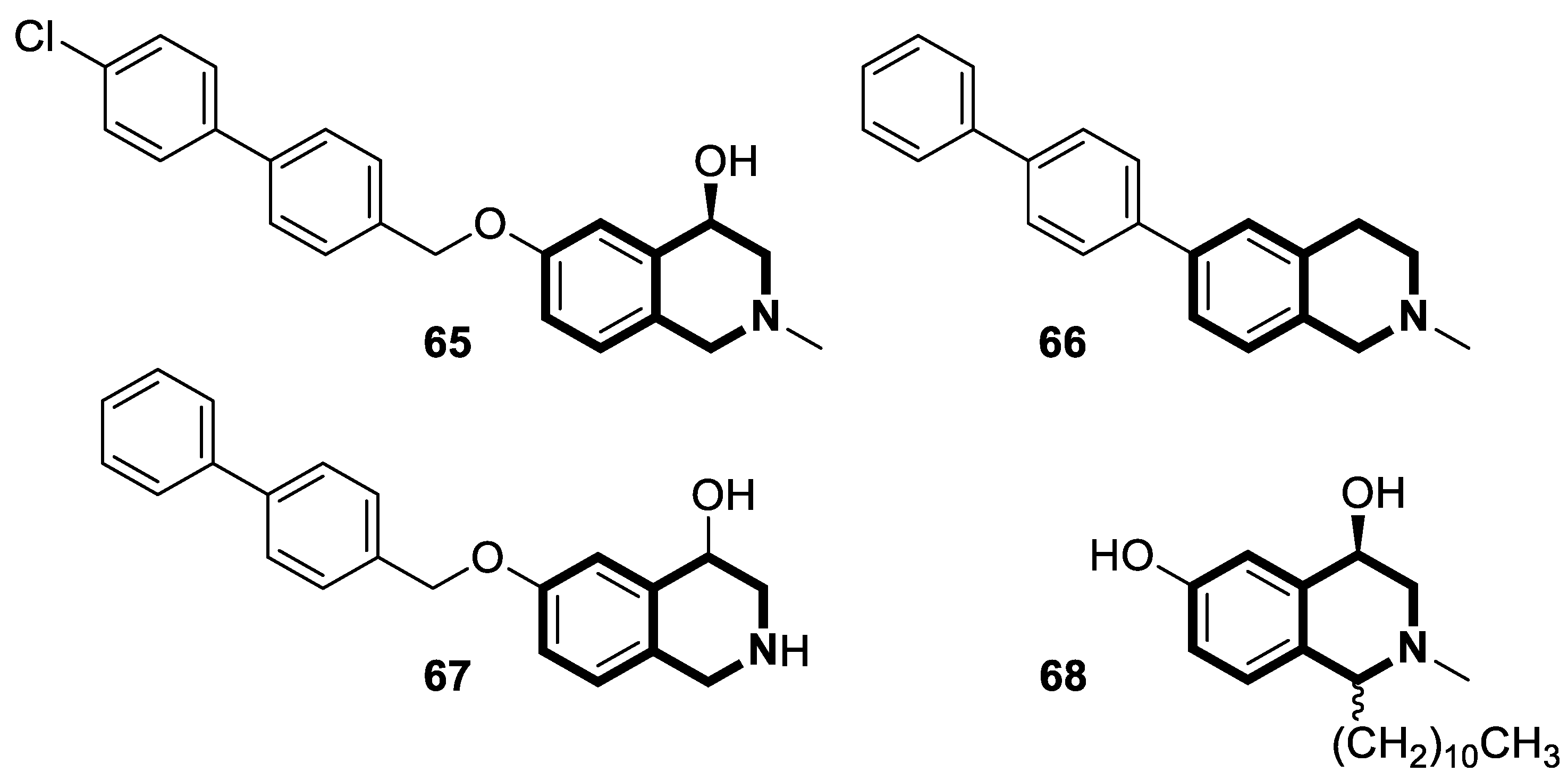

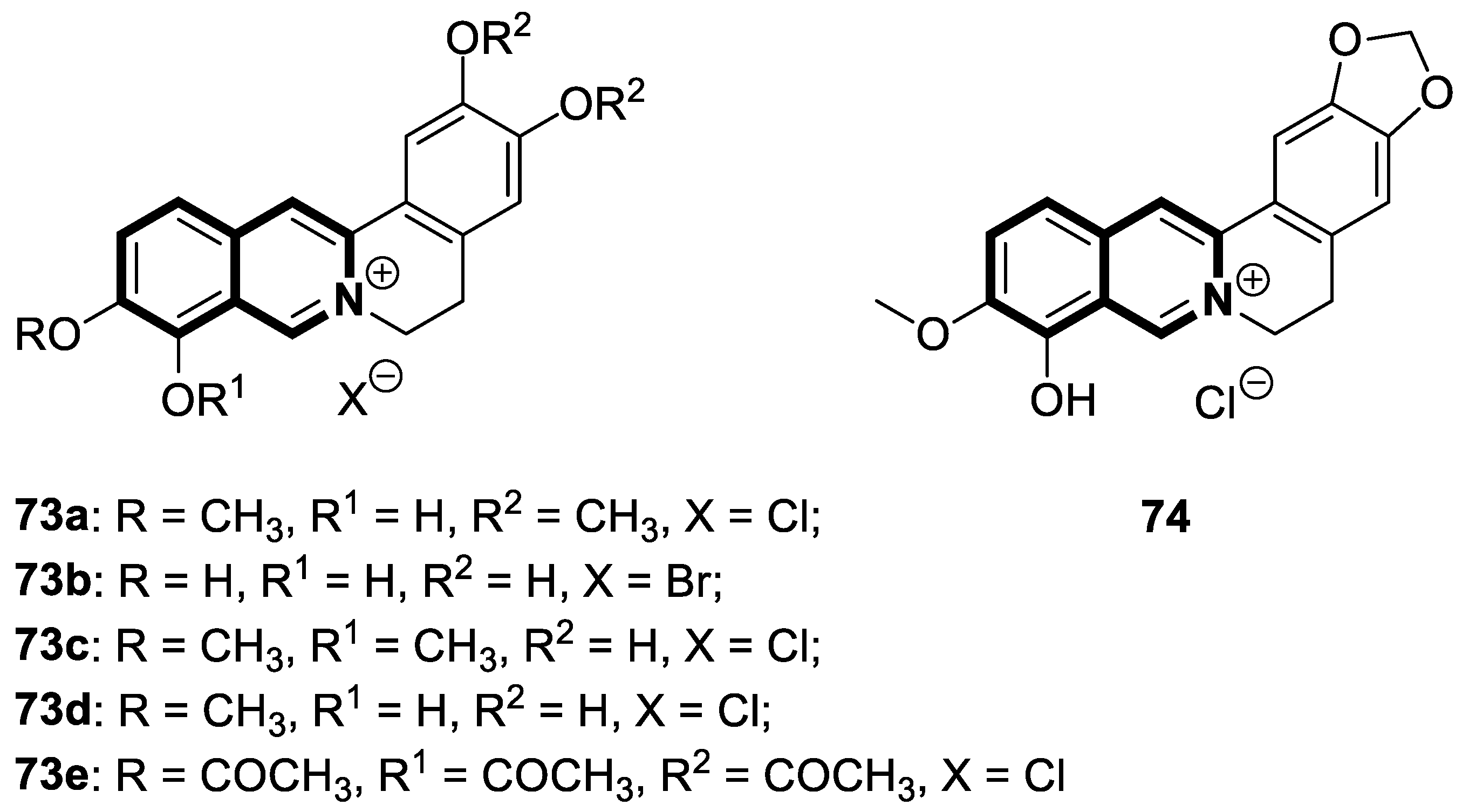

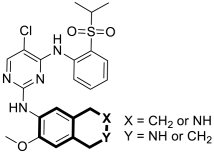

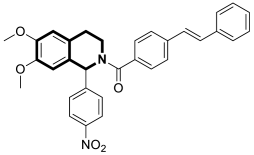

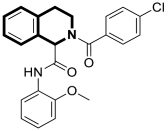

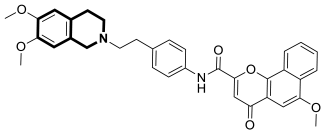

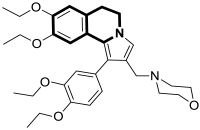

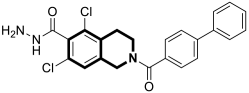

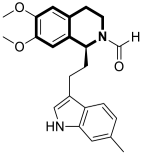

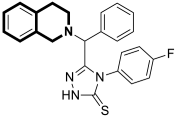

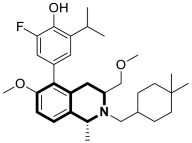

2.1.3. Tetrahydroisoquinoline-Based Compounds

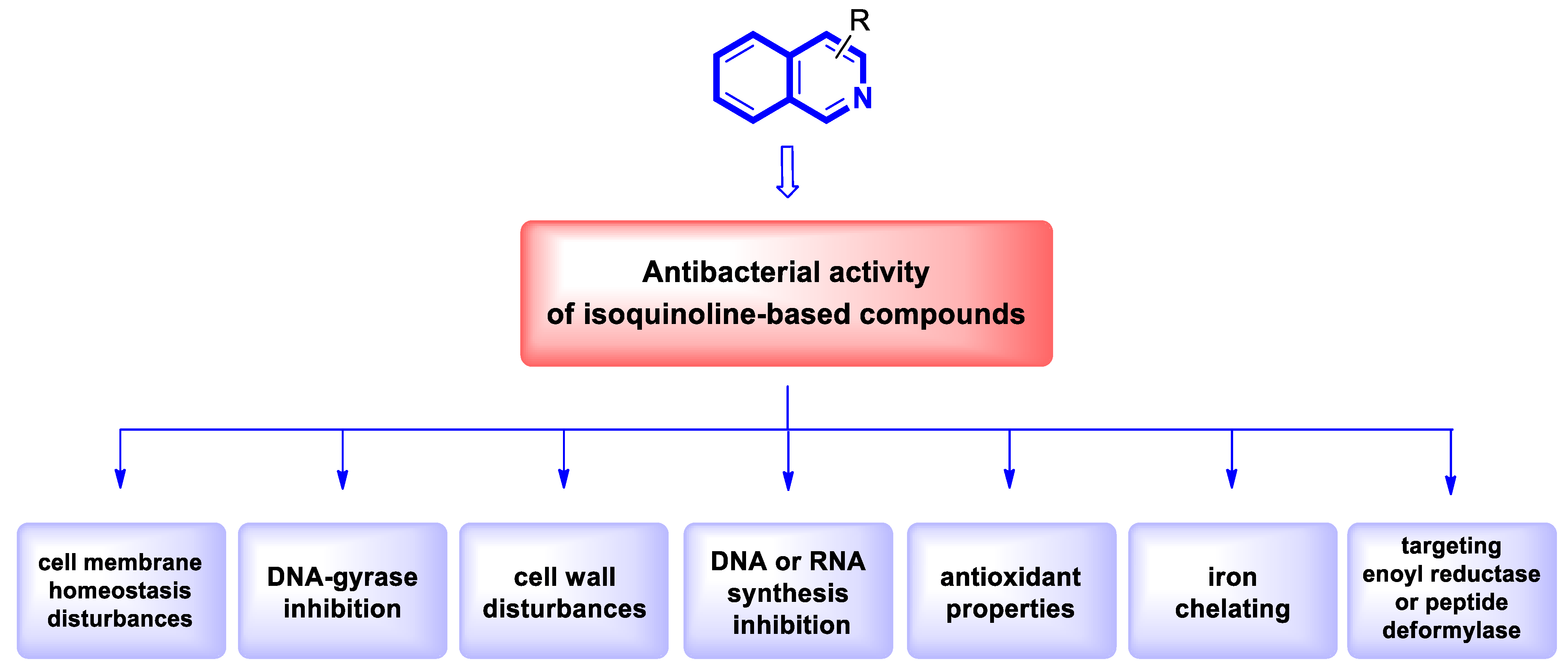

2.2. Antibacterial Agents

2.2.1. Isoquinoline-Based Compounds

2.2.2. Tetrahydroisoquinoline-Based Compounds

2.3. Anti-Mycobacterial Agents

2.3.1. Isoquinoline-Based Compounds

2.3.2. Tetrahydroisoquinoline-Based Compounds

2.4. Antifungal Agents

2.4.1. Isoquinoline-Based Compounds

2.4.2. Tetrahydroisoquinoline-Based Compounds

2.5. Antiviral Agents

2.5.1. Isoquinoline-Based Compounds

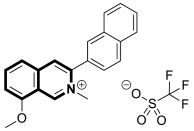

2.5.2. Dihydroisoquinoline-Based Compounds

2.5.3. Tetrahydroisoquinoline-Based Compounds

2.6. Antimalarial Agents

2.6.1. Isoquinoline-Based Compounds

2.6.2. Tetrahydroisoquinoline-Based Compounds

2.7. Anti-Trypanosoma Agents

2.8. Antileishmanial Agents

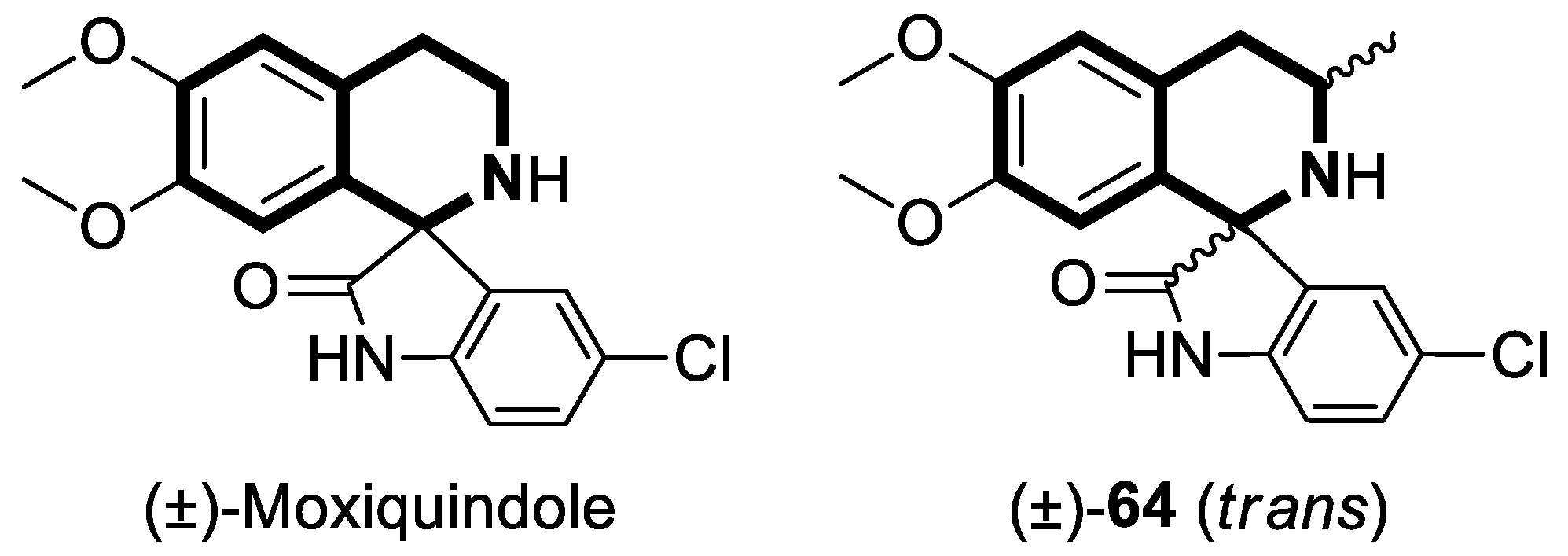

2.9. Antischistosomal Agents

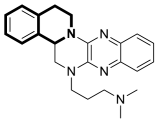

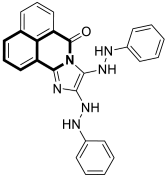

3. Anti-Alzheimer’s Disease Activity

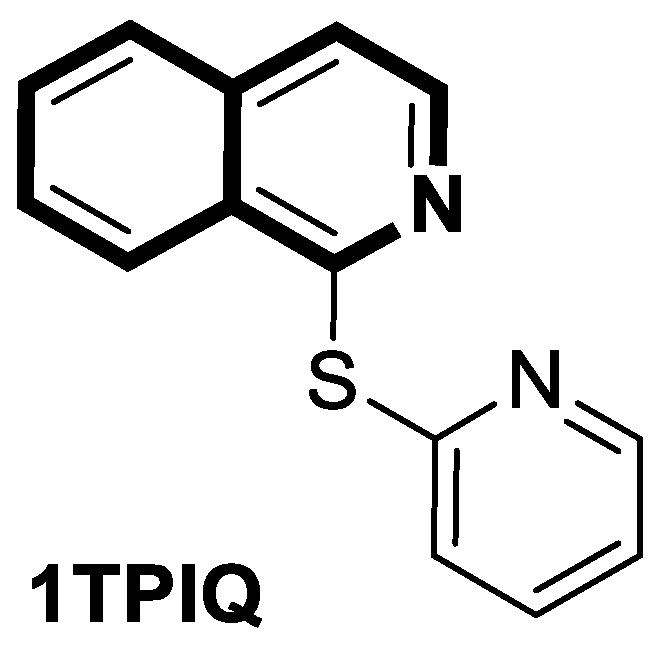

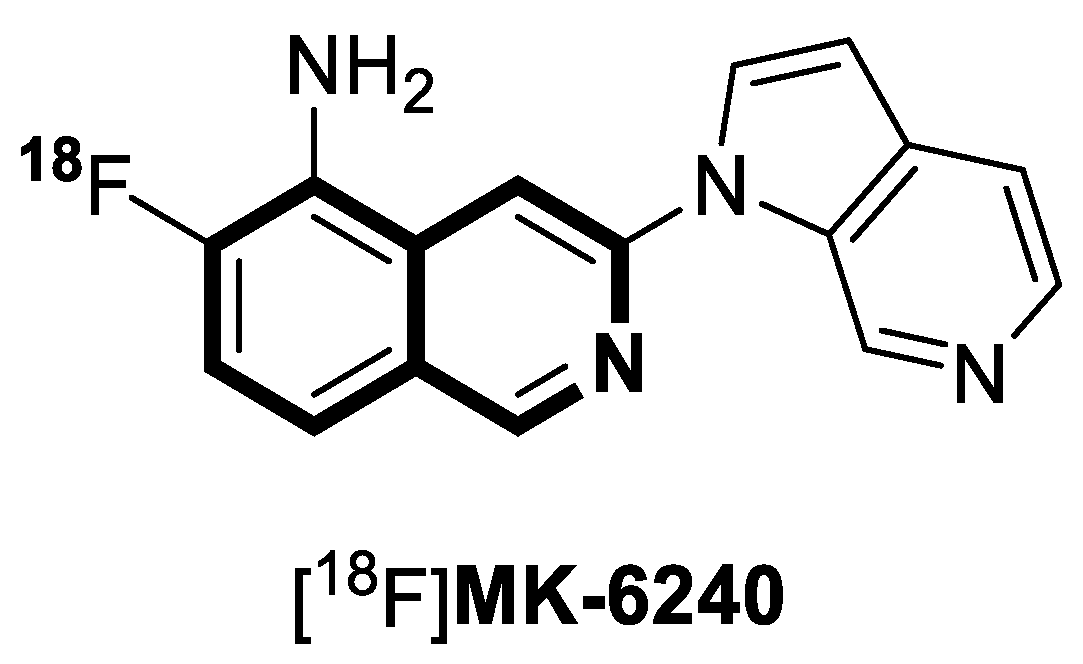

3.1. Isoquinoline-Based Compounds

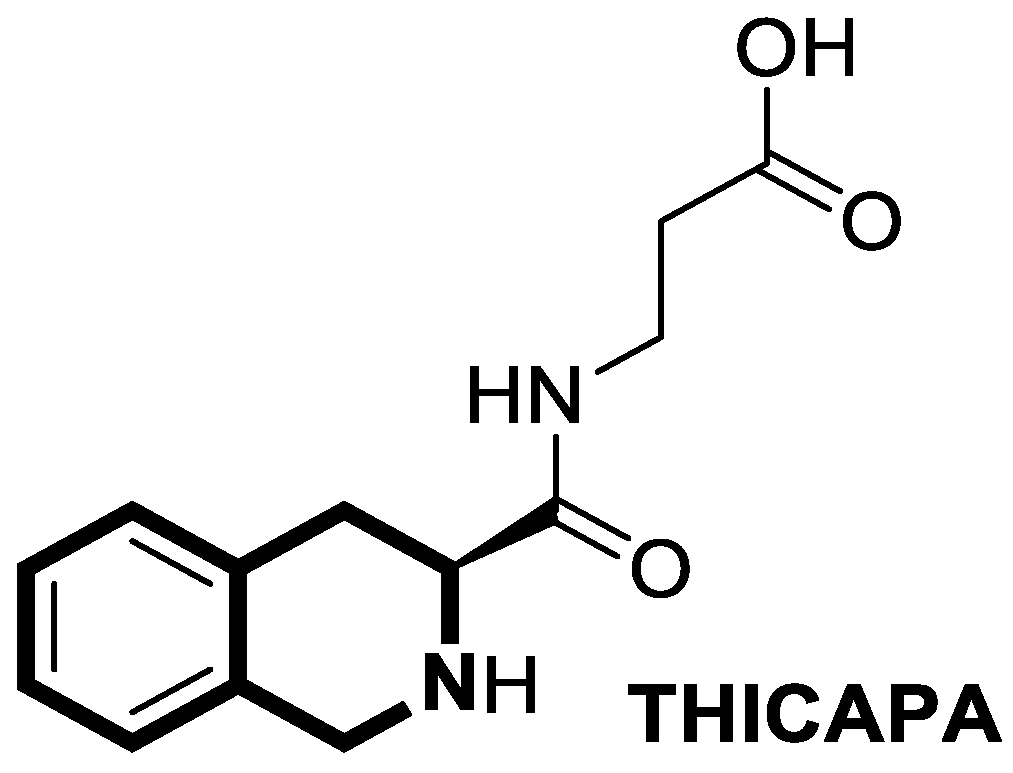

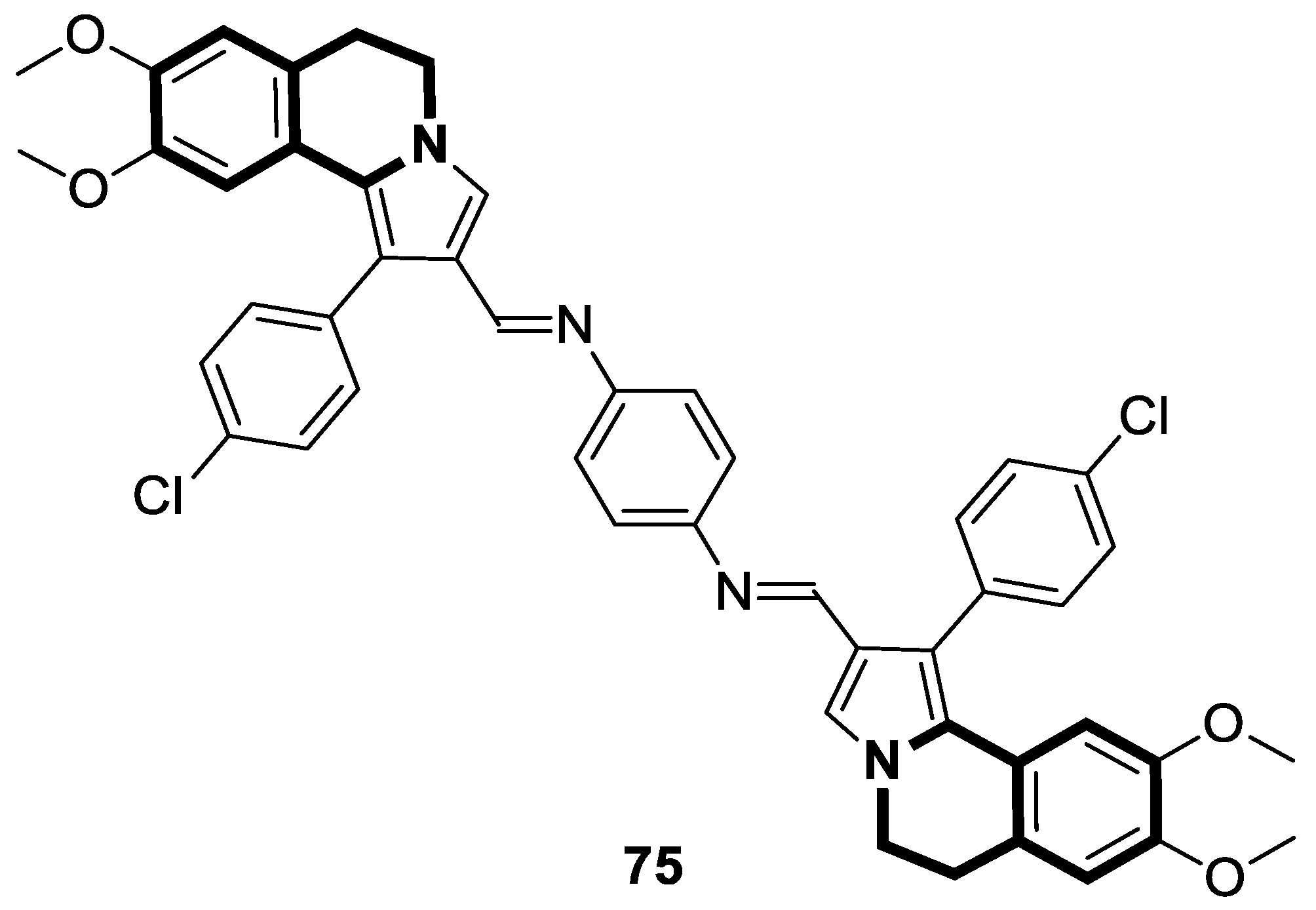

3.2. Tetrahydroisoquinoline-Based Compounds

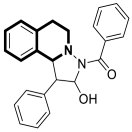

4. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

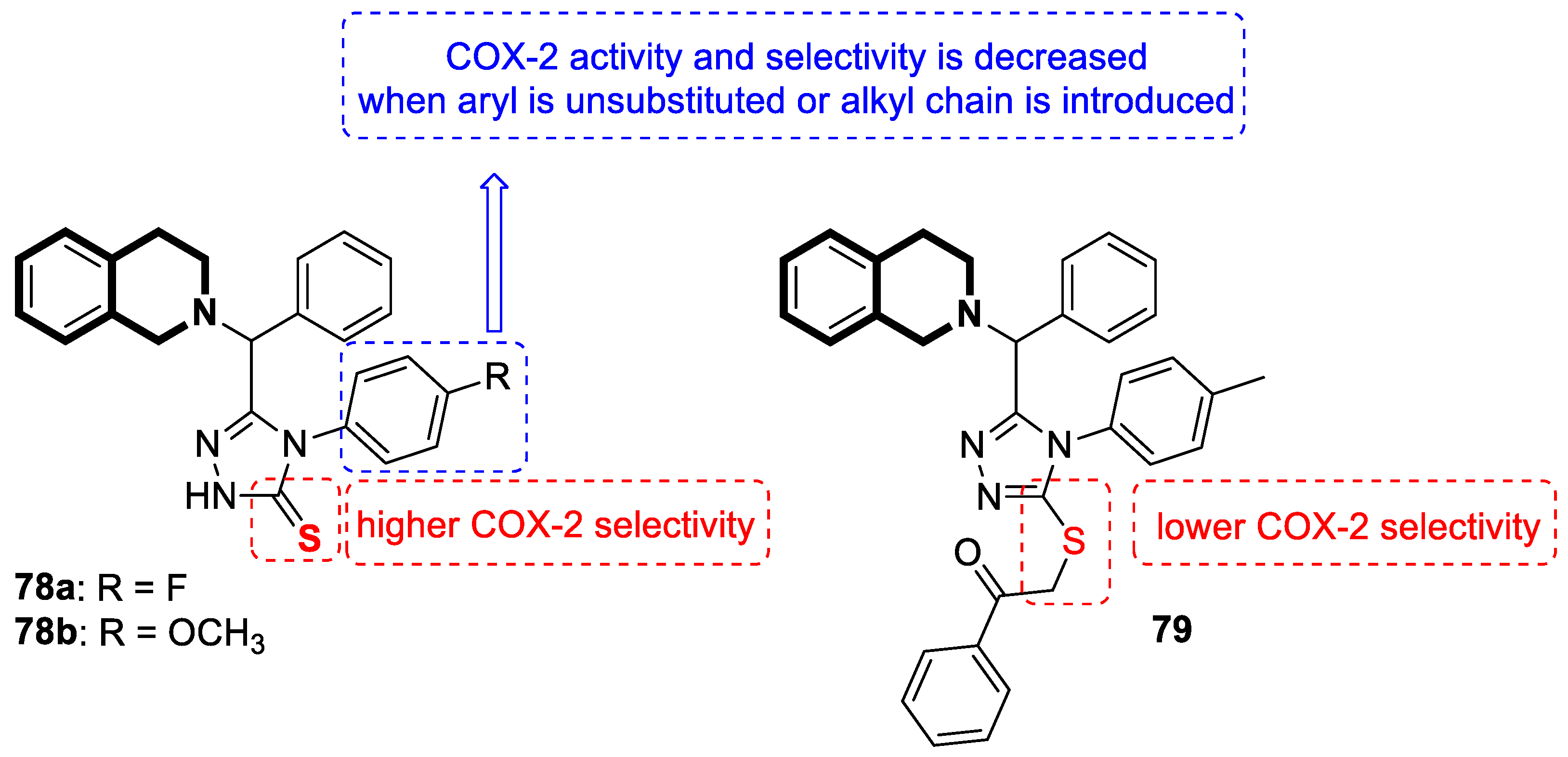

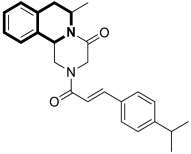

4.1. Dihydroisoquinoline-Based Compounds

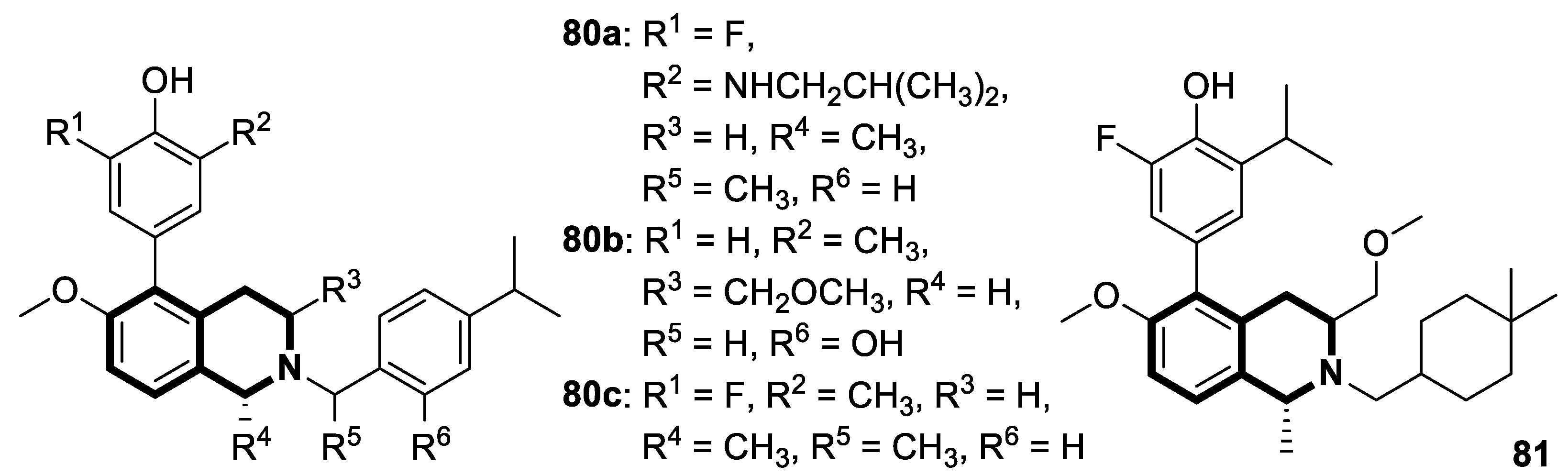

4.2. Tetrahydroisoquinoline-Based Compounds

5. Antidiabetic Activity

6. Other Biomedical Applications

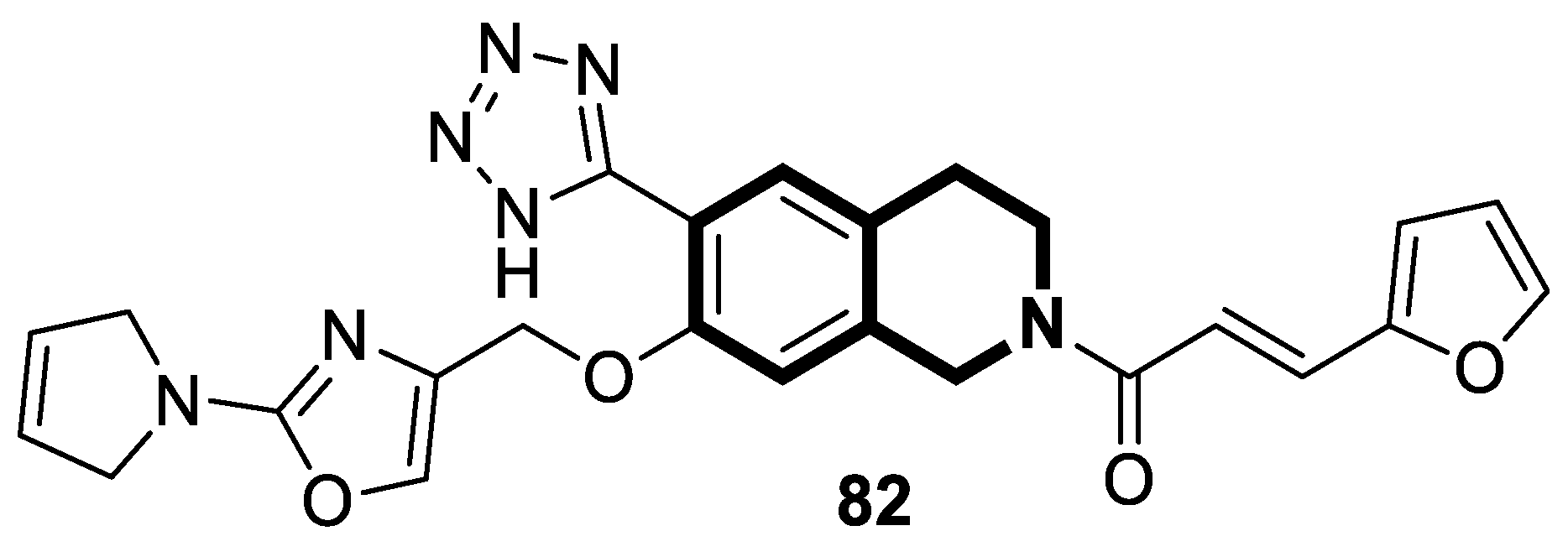

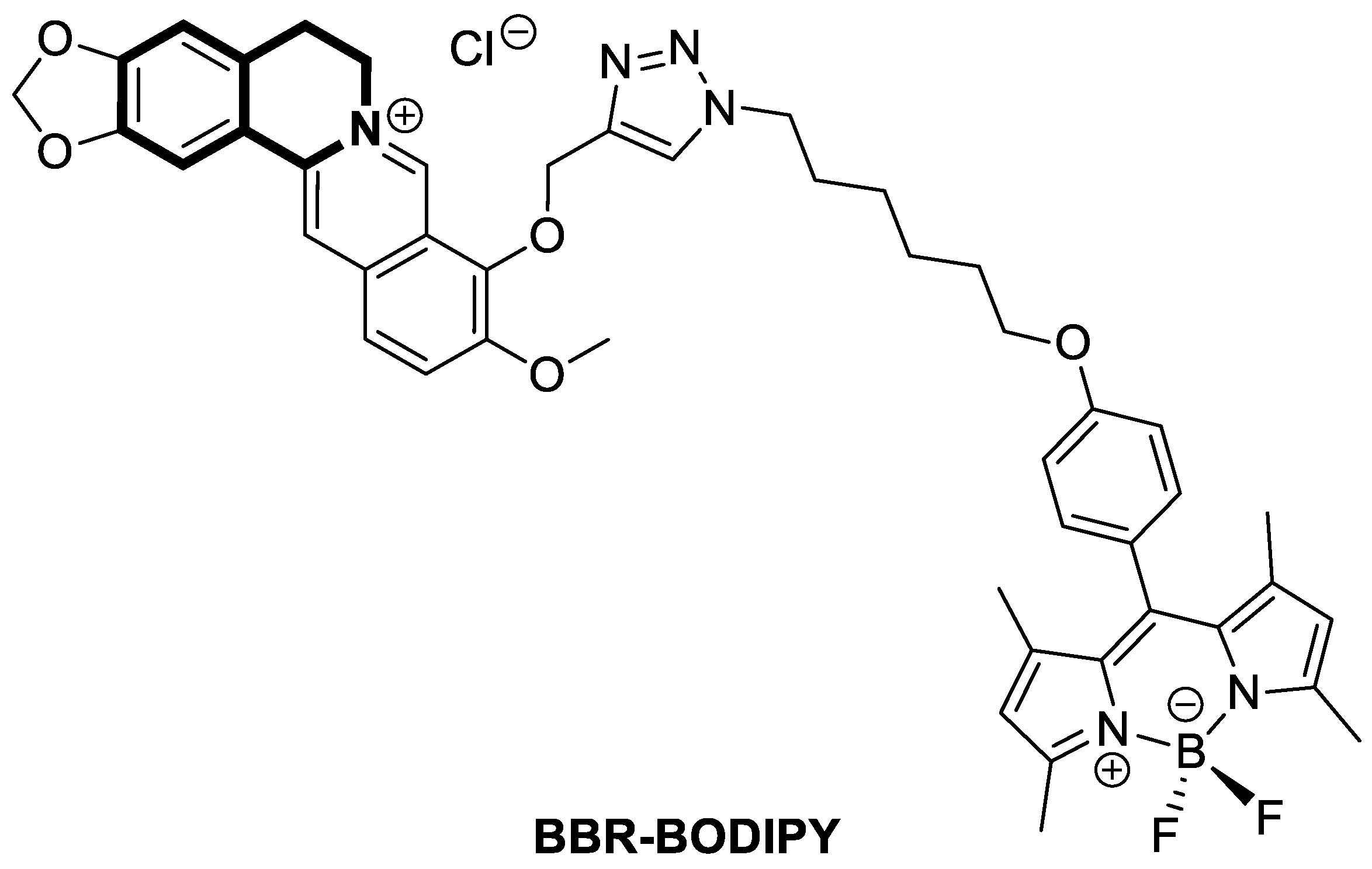

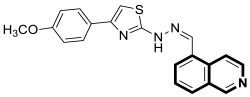

6.1. Isoquinoline-Based Compounds

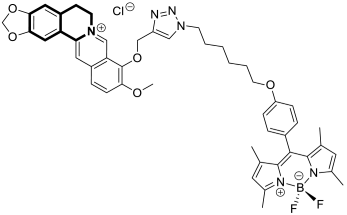

6.2. Tetrahydroisoquinoline-Based Compounds

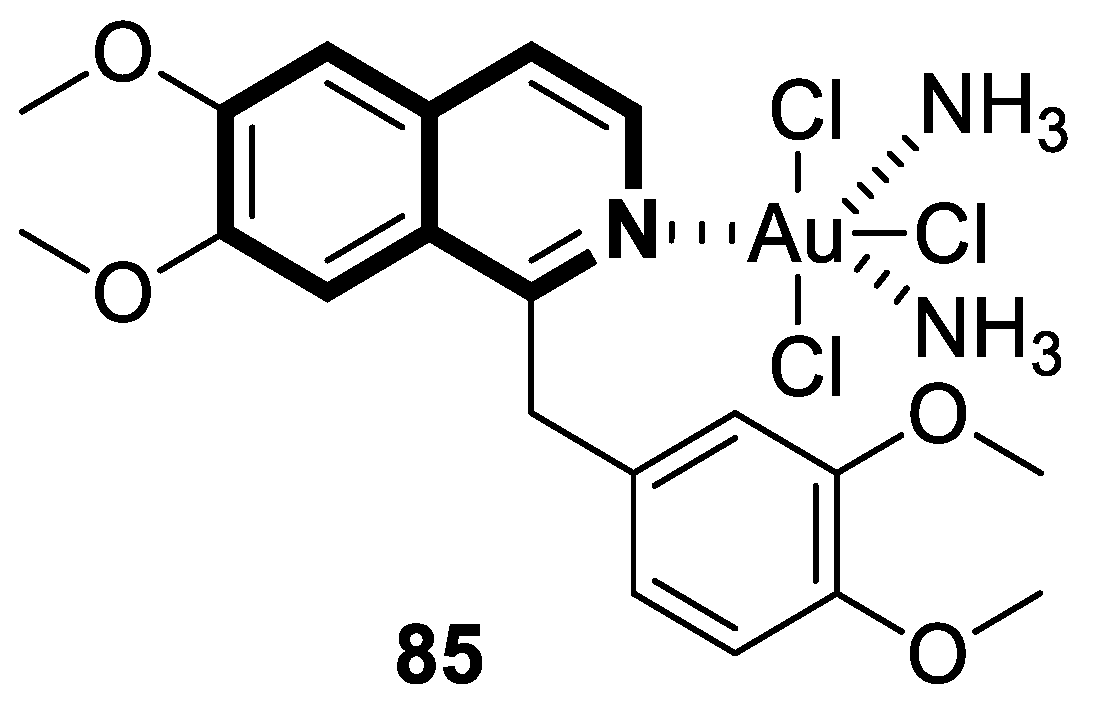

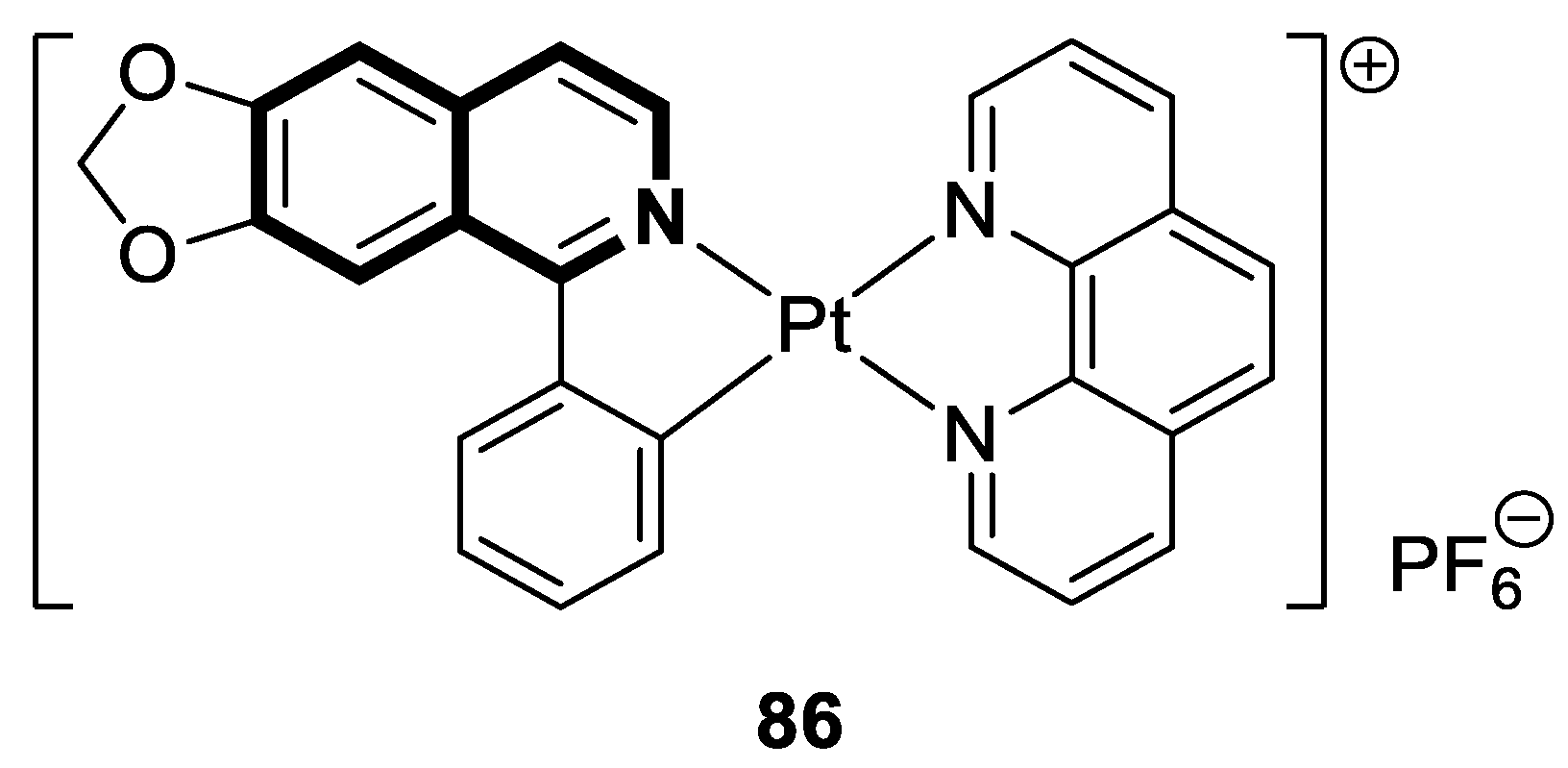

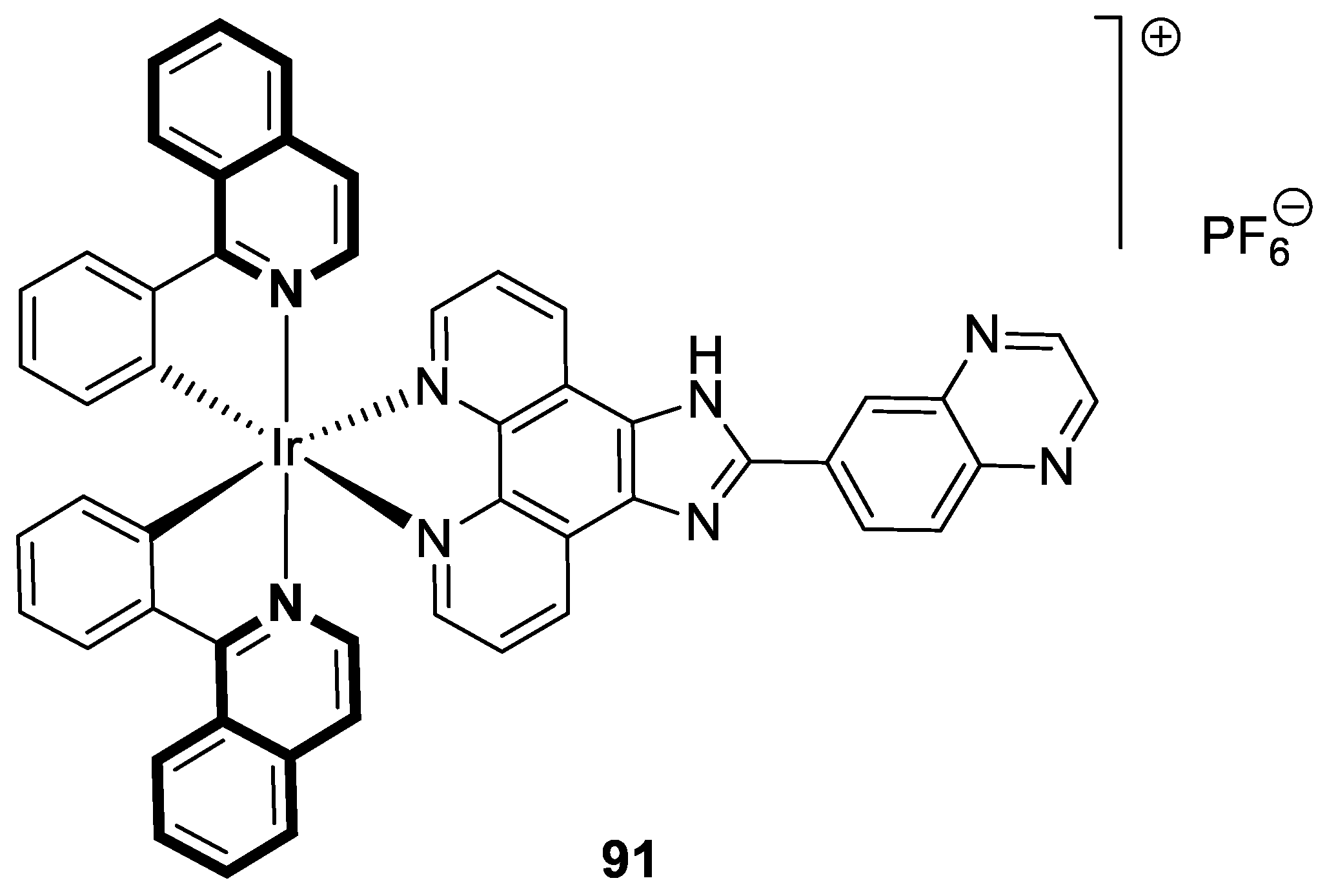

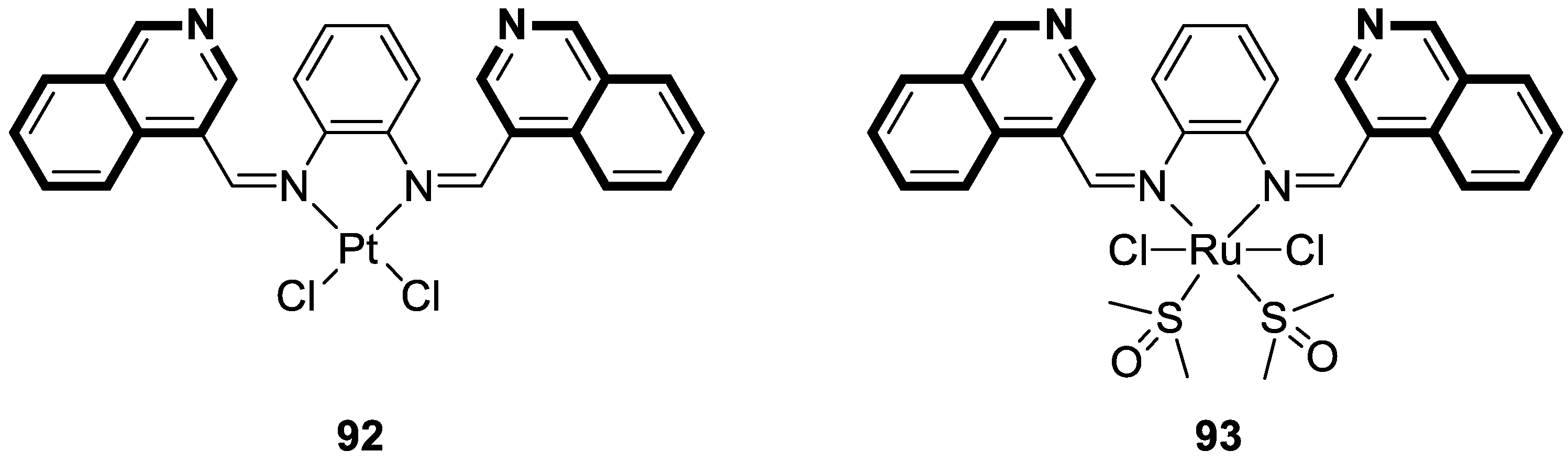

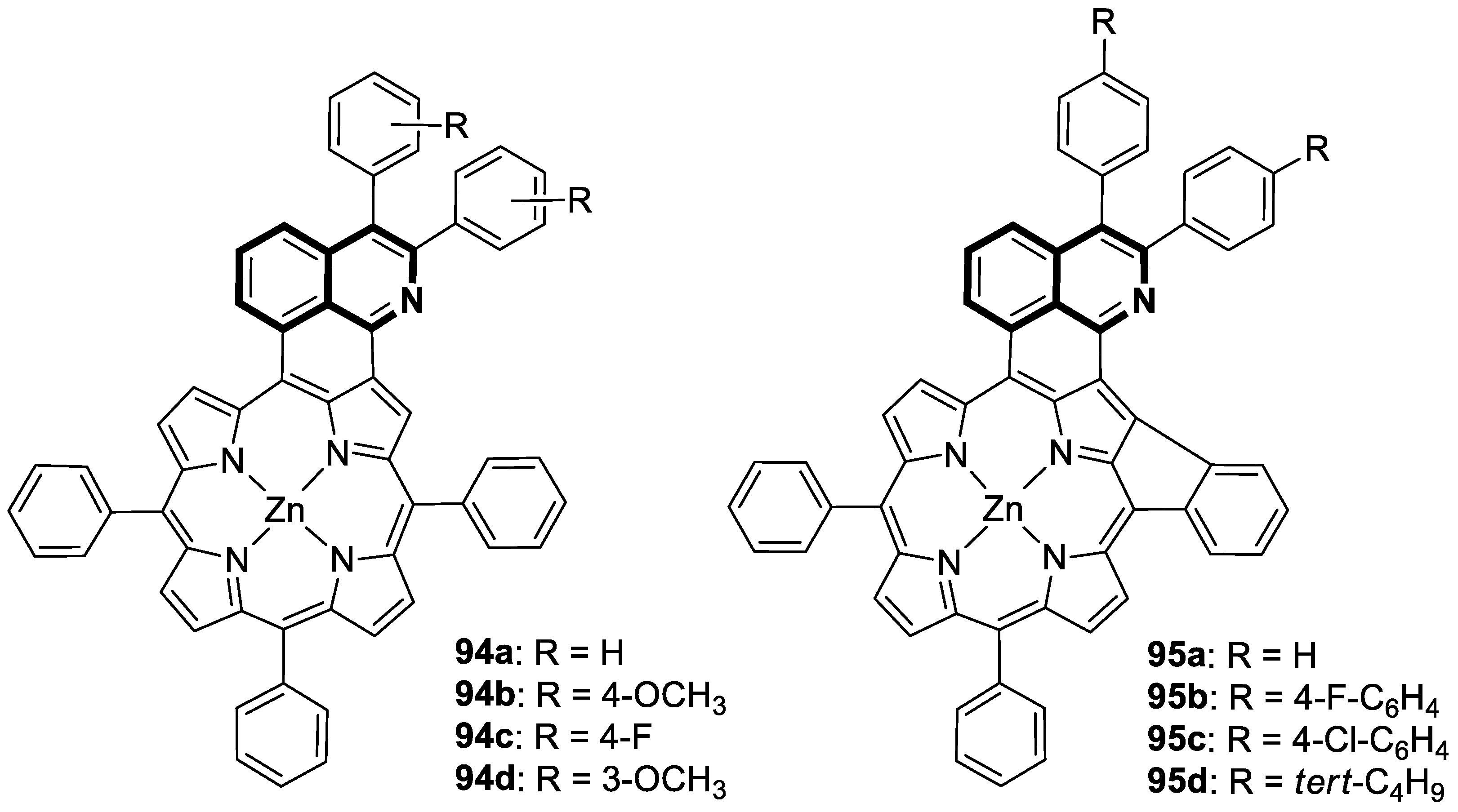

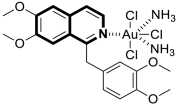

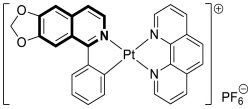

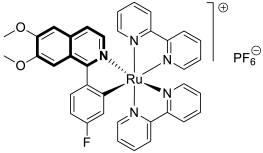

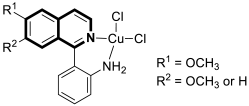

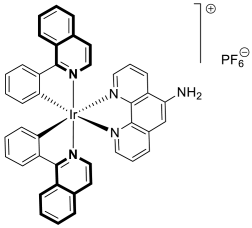

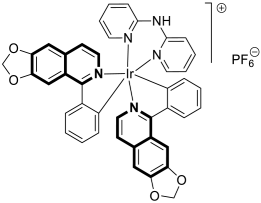

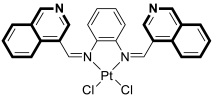

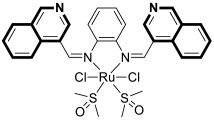

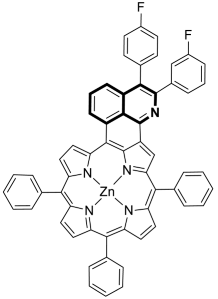

7. Metal Complexes of Isoquinoline-Based Compounds with Biological Activities

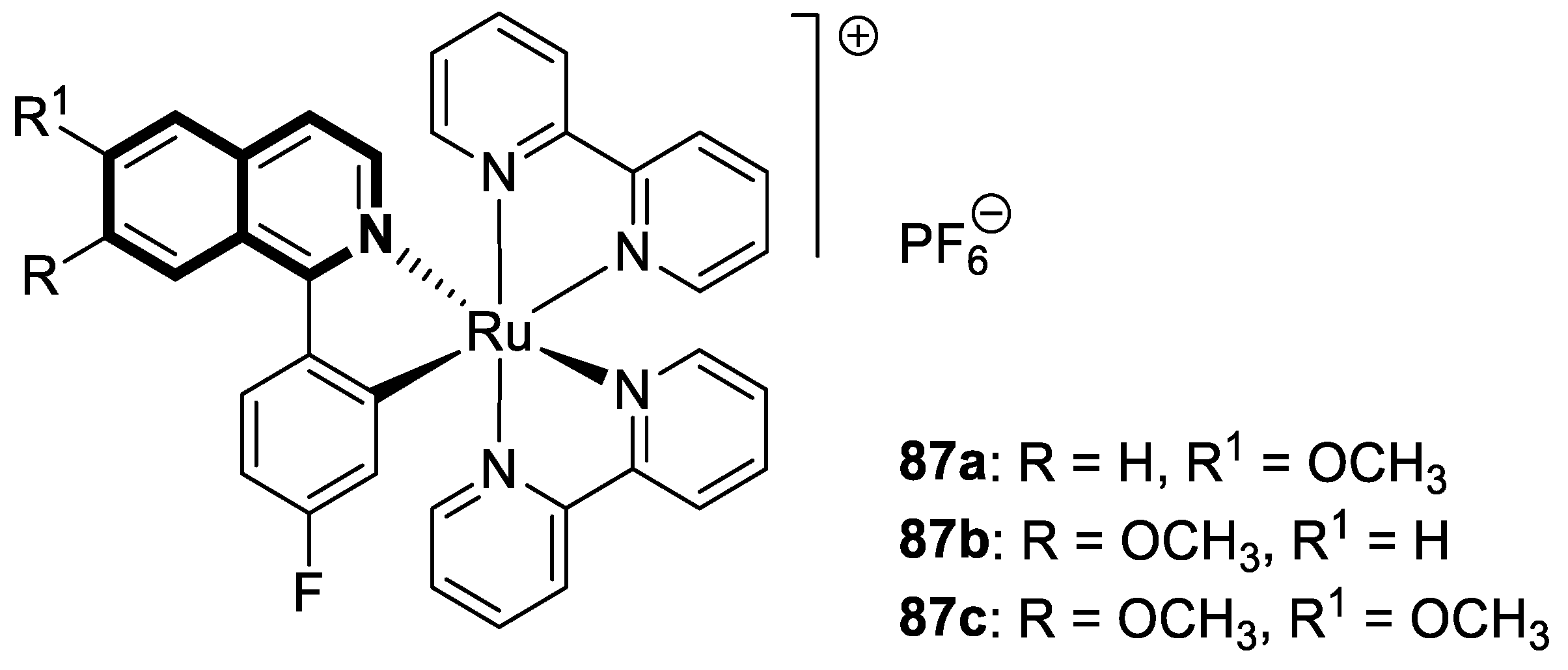

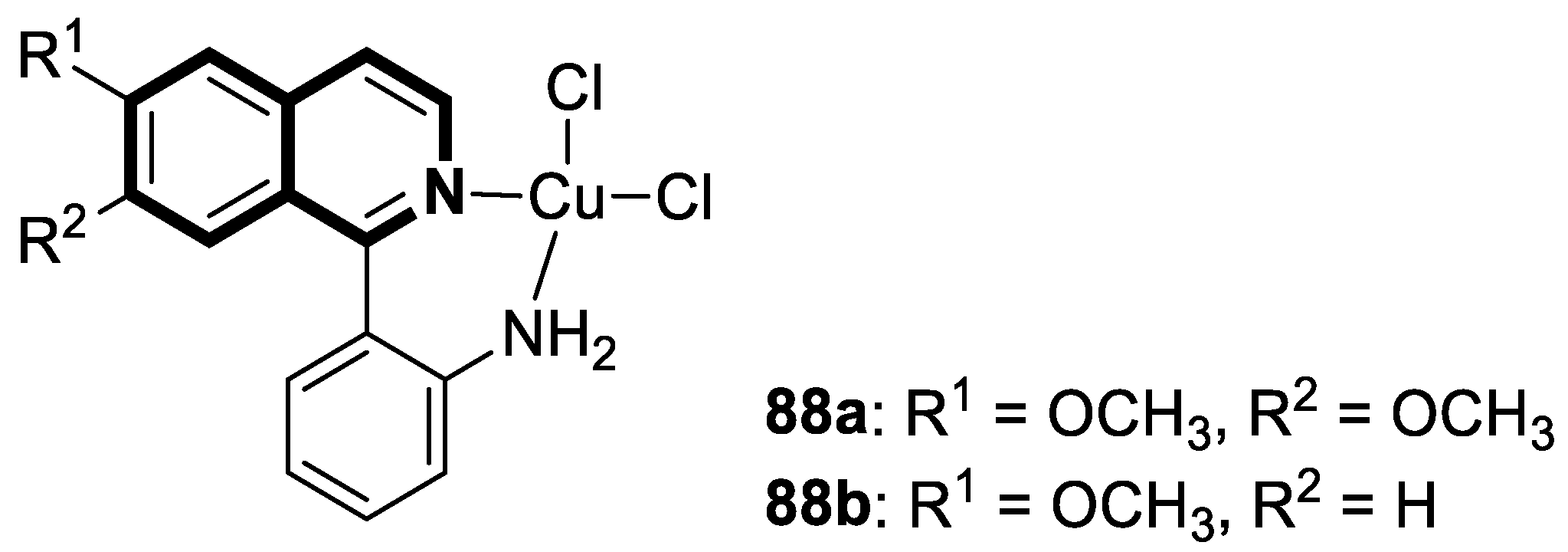

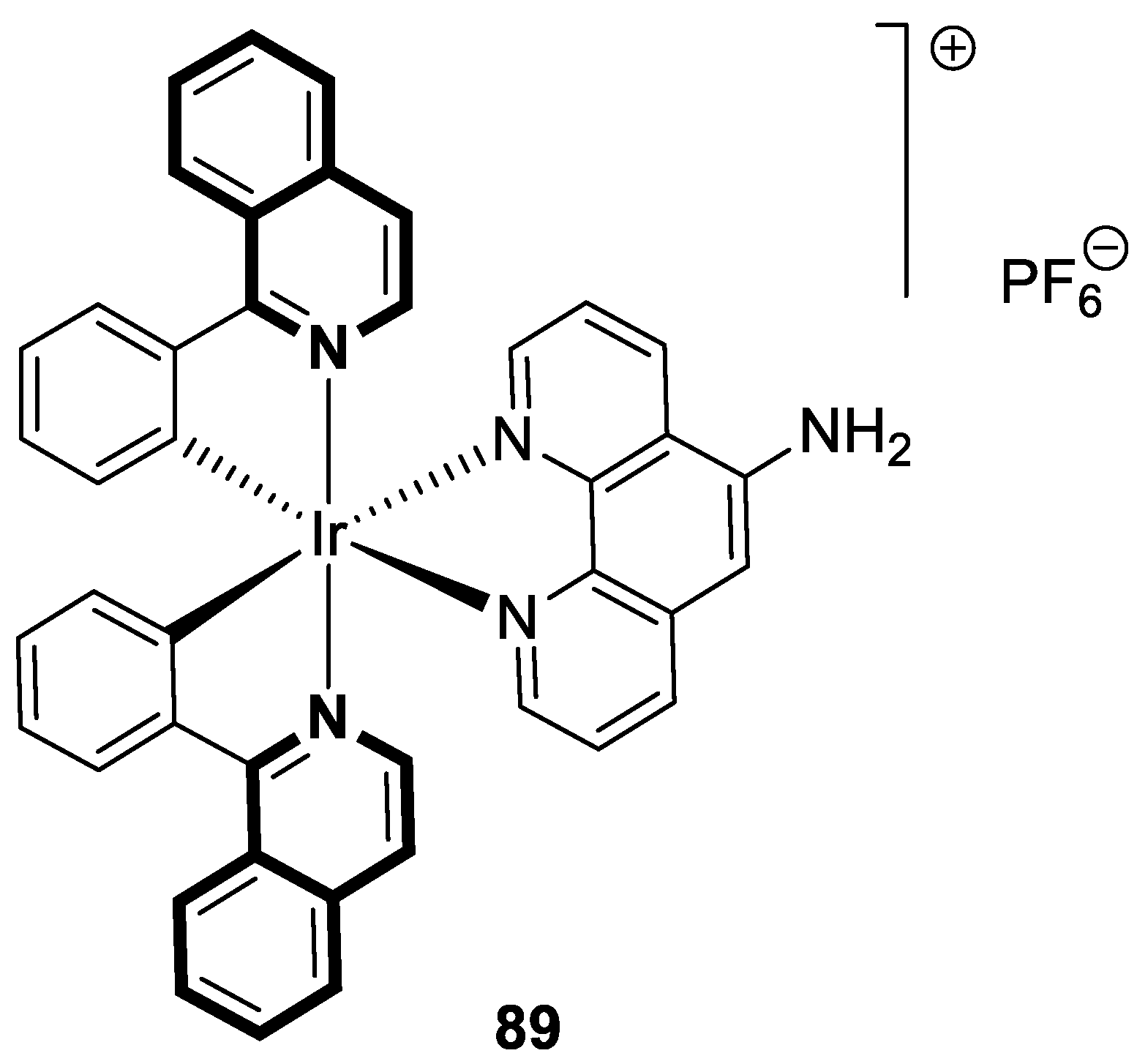

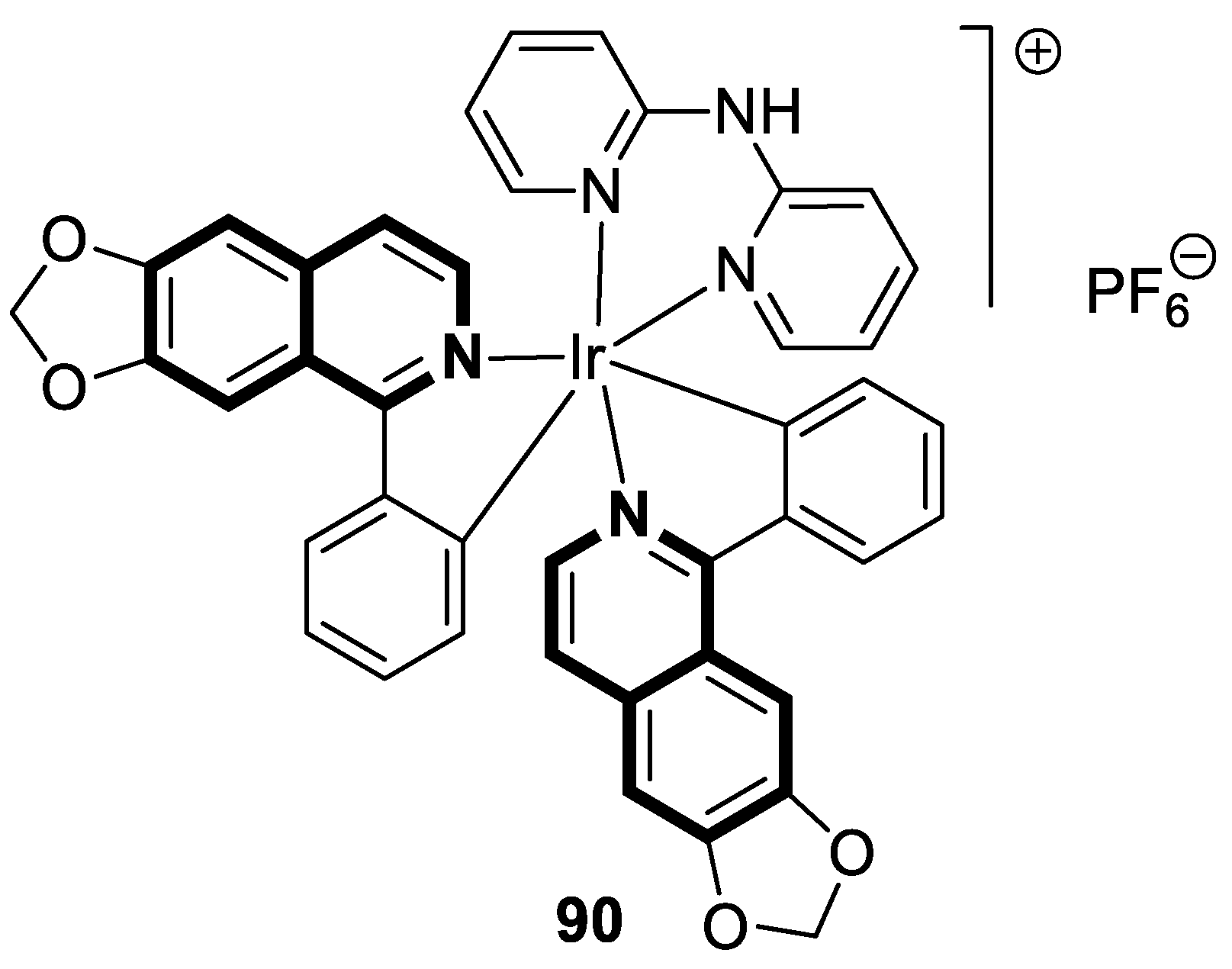

7.1. Anticancer Agents

7.2. Anti-Alzheimer Agents

7.3. Photosensitizers

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khan, A.Y.; Suresh, K.G. Natural isoquinoline alkaloids: Binding aspects to functional proteins, serum albumins, hemoglobin, and lysozyme. Biophys. Rev. 2015, 7, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuzimski, T.; Petruczynik, A. New trends in the practical use of isoquinoline alkaloids as potential drugs applicated in infectious and non-infectious diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 168, 115704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Miao, X.; Dai, L.; Guo, X.; Jenis, J.; Zhang, J.; Shang, X. Isolation, biological activity, and synthesis of isoquinoline alkaloids. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2024, 41, 1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, D.; Yoon, S.Y.; Park, S.J.; Park, Y.J. The anticancer effect of natural plant alkaloid isoquinolines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, C.; Guan, G.; Wang, H. The anticancer effect of sanguinarine: A review. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2018, 24, 2760–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achkar, I.W.; Mraiche, F.; Mohammad, R.M.; Uddin, S. Anticancer potential of sanguinarine for various human malignancies. Future Med. Chem. 2017, 9, 933–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Sagar, B.; Gaur, A.; Shukla, S.; Pandey, E.; Gulati, S. Insight into the tubulin-targeted anticancer potential of noscapine and its structural analogs. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2023, 23, 624–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, G.; Wang, J.; Hu, J.; Gan, Q.; Peng, C.; Xiong, H.; Huang, Q. Sanguinarine: A double-edged sword of anticancer and carcinogenesis and its future application prospect. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2021, 21, 2100–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, Z.X.; Huang, J.L.; Yang, X.Y.; Liu, J.H.; Cao, H.L.; Xiang, F.; Cheng, P.; Zeng, J.G. Anticancer and reversing multidrug resistance activities of natural isoquinoline alkaloids and their structure-activity relationship. Curr. Med. Chem. 2018, 25, 5088–5114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.; Kumar, A.; Althagafi, I.; Nemaysh, V.; Rai, R.; Pratap, R. The recent development of tetrahydro-quinoline/isoquinoline based compounds as anticancer agents. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2021, 21, 1587–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhambhani, S.; Kondhare, K.R.; Giri, A.P. Diversity in chemical structures and biological properties of plant alkaloids. Molecules 2021, 26, 3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Patil, P.; Kurpiewska, K.; Kalinowska-Tluscik, J.; Dömling, A. Diverse isoquinoline scaffolds by Ugi/Pomeranz–Fritsch and Ugi/Schlittler–Müller reactions. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 3533–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barratt, J.; Andric, B.; Tataradze, A.; Schomig, M.; Reusch, M.; Valluri, U.; Mariat, C. Roxadustat for the treatment of anaemia in chronic kidney disease patients not on dialysis: A Phase 3, randomized, open-label, active-controlled study (DOLOMITES). Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2021, 36, 1616–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Jiang, L.; Wei, X.; Long, M.; Du, Y. Roxadustat: Not just for anemia. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 971795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, N.; Hao, C.; Peng, X.; Lin, H.; Yin, A.; Hao, L.; Tao, Y.; Liang, X.; Liu, Z.; Xing, C.; et al. Roxadustat for anemia in patients with kidney disease not receiving dialysis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1001–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eley, T.; Garimella, T.; Li, W.; Bertz, R.J. Asunaprevir: A review of preclinical and clinical pharmacokinetics and drug–drug interactions. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2015, 54, 1205–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajinasiri, R. A review of the synthesis of 1,2-dihydroisoquinoline, [2,1-a] isoquinoline and [5,1-a] isoquinoline since 2006. Tetrahedron 2022, 104, 132576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shklyaev, Y.V.; Nifontov, Y.V. Three-component synthesis of 3,4-dihydroisoquinoline derivatives. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2002, 51, 844–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, M.; Imaji, R.; Shiomi, S. Synthesis of substituted 1,2-dihydroisoquinolines by palladium-catalyzed cascade cyclization-coupling of trisubstituted allenamides with arylboronic acids. Molecules 2024, 29, 2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyne, M.E.; Martin, V.J.J. Microbial synthesis of natural, semisynthetic, and new-to-nature tetrahydroisoquinoline alkaloids. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2022, 33, 100561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faheem; Karan Kumar, B.; Venkata Gowri Chandra Sekhar, K.; Chander, S.; Kunjiappan, S.; Murugesan, S. 1,2,3,4-Tetrahydroisoquinoline (THIQ) as privileged scaffold for anticancer de novo drug design. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2021, 16, 1119–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, I.P.; Shah, P. Tetrahydroisoquinolines in therapeutics: A patent review (2010–2015). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2017, 27, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanwar, A.K.; Sengar, N.; Mase, N.; Singh, I.P. Tetrahydroisoquinolines—An updated patent review for cancer treatment (2016–present). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2024, 34, 873–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, A.N.; Ngamnithiporn, A.; Du, E.; Stoltz, B.M. Recent advances in the total synthesis of the tetrahydroisoquinoline alkaloids (2002–2020). Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 9447–9496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngamnithiporn, A.; Welin, E.R.; Pototschnig, G.; Stoltz, B.M. Evolution of a synthetic strategy toward the syntheses of bis-tetrahydroisoquinoline alkaloids. Acc. Chem. Res. 2024, 57, 1870–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkhordarian, M.; Lawrence, J.A.; Ulusan, S.; Erbay, M.I.; Aronow, W.S.; Gupta, R. Benefit and risk evaluation of quinapril hydrochloride. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2023, 22, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysant, G.S.; Nguyen, P.K. Moexipril and left ventricular hypertrophy. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2007, 3, 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Patai, Z.; Guttman, A.; Mikus, E.G. Potential L-type voltage-operated calcium channel blocking effect of drotaverine on functional models. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2016, 359, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doroshyenko, O.; Fuhr, U. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of solifenacin. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2009, 48, 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkop, B. Preparation of cis- and trans-decahydroisoquinolines and of bz-tetrahydroisoquinoline. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1948, 70, 2617–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathison, I.W.; Morgan, P.H.; Tidwell, R.R.; Handorf, C.R. Steric and physicochemical studies of decahydroisoquinolines possessing antiarrhythmic activity. J. Pharm. Sci. 1972, 61, 637–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, M.J.; Bond, A.; Ornstein, P.L.; Ward, M.A.; Hicks, C.A.; Hoo, K.; Bleakman, D.; Lodge, D. Decahydroisoquinolines: Novel competitive AMPA/kainate antagonists with neuroprotective effects in global cerebral ischaemia. Neuropharmacology 1998, 37, 1211–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, D.A.; Joubert, A.M.; Visagie, M.H. The biological relevance of papaverine in cancer cells. Cells 2022, 11, 3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

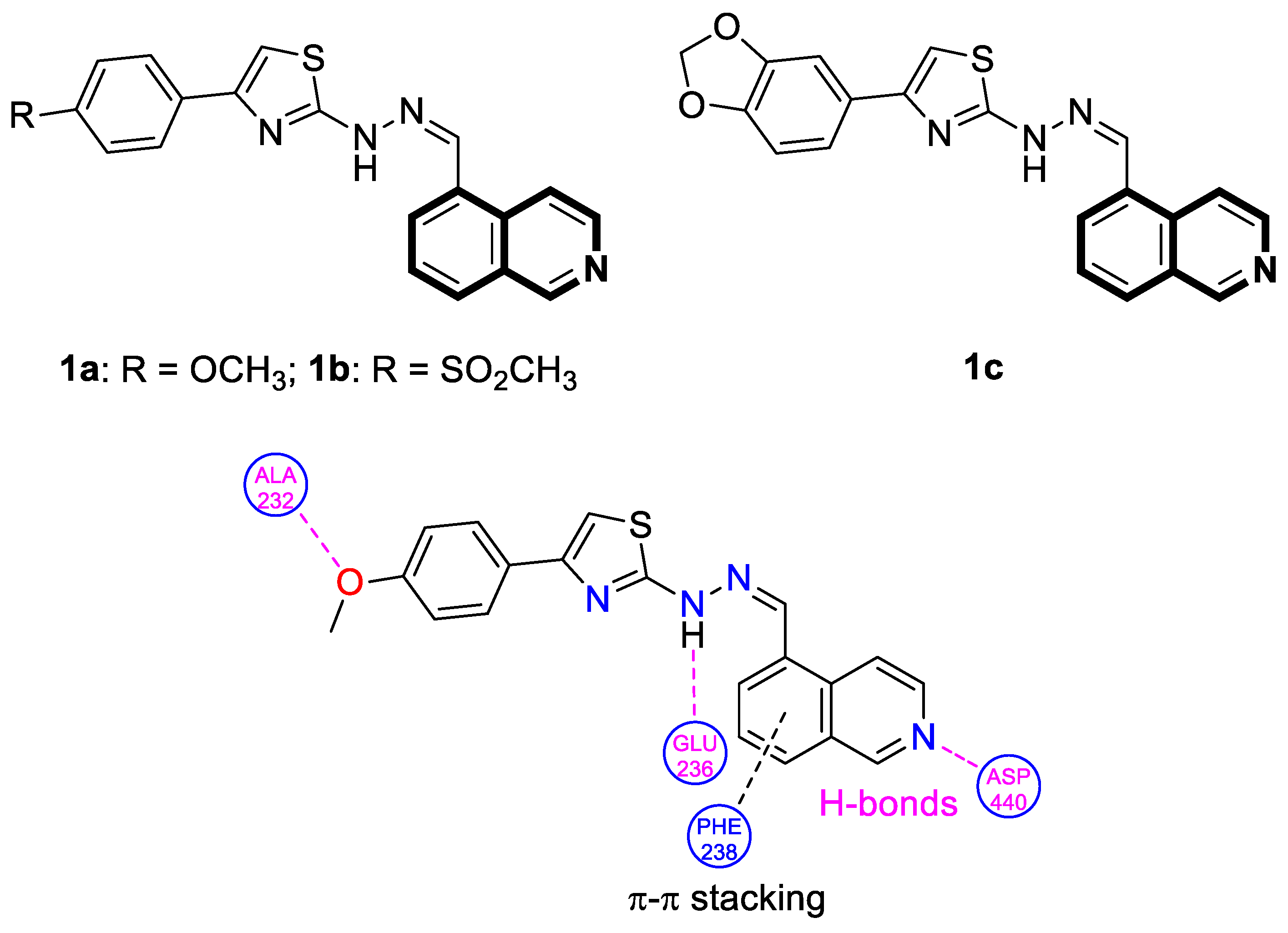

- Orujova, T.; Ece, A.; Akalın, Ç.G.; Özdemir, A.; Altıntop, M.D. A new series of thiazole-hydrazone hybrids for Akt-targeted therapy of non-small cell lung cancer. Drug Dev. Res. 2023, 84, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Yan, Z.; Miao, Y.; Ha, W.; Li, Z.; Yang, L.; Mi, D. Copper in cancer: From limiting nutrient to therapeutic target. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1209156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolmaleki, S.; Aliabadi, A.; Khaksar, S. Unveiling the promising anticancer effect of copper-based compounds: A comprehensive review. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 150, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, D.; Song, J.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ba, Y.; Luo, P.; Cheng, Q.; Xu, H.; Weng, S.; Zuo, A.; et al. Copper in cancer: Friend or foe? Metabolism, dysregulation, and therapeutic opportunities. Cancer Commun. 2025, 45, 577–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

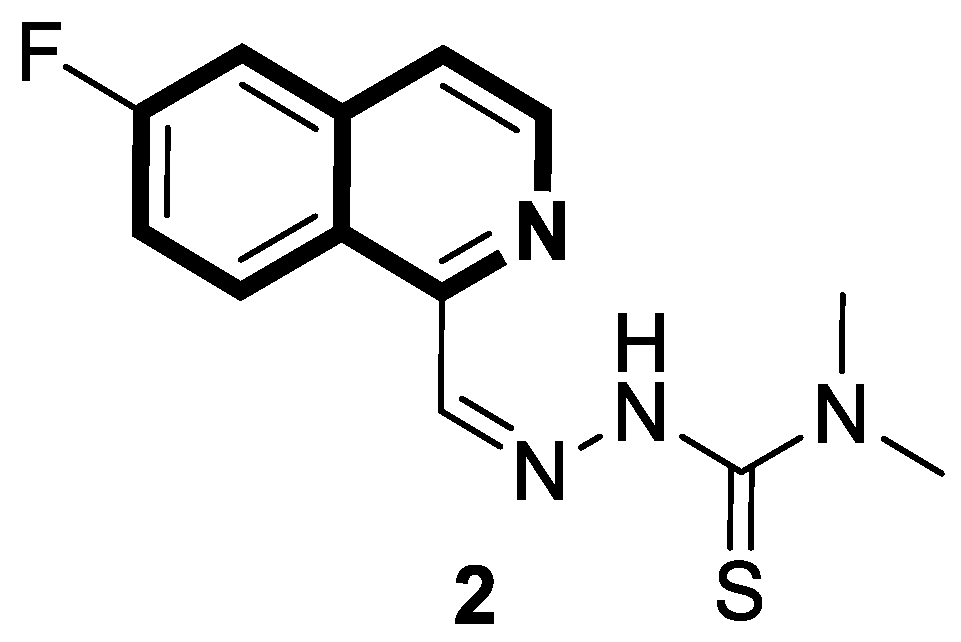

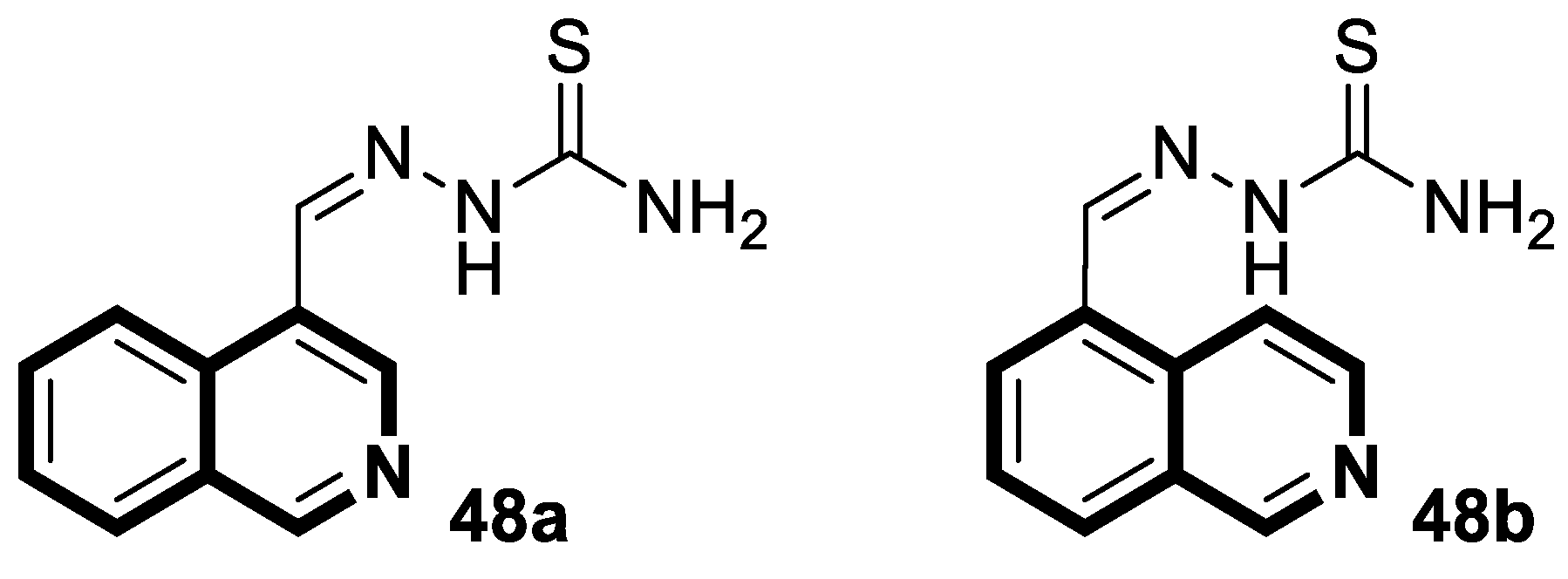

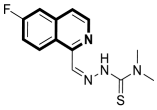

- Sun, D.L.; Poddar, S.; Pan, R.D.; Rosser, E.W.; Abt, E.R.; Van Valkenburgh, J.; Le, T.M.; Lok, V.; Hernandez, S.P.; Song, J.; et al. Isoquinoline thiosemicarbazone displays potent anticancer activity with in vivo efficacy against aggressive leukemias. RSC Med. Chem. 2020, 11, 392–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

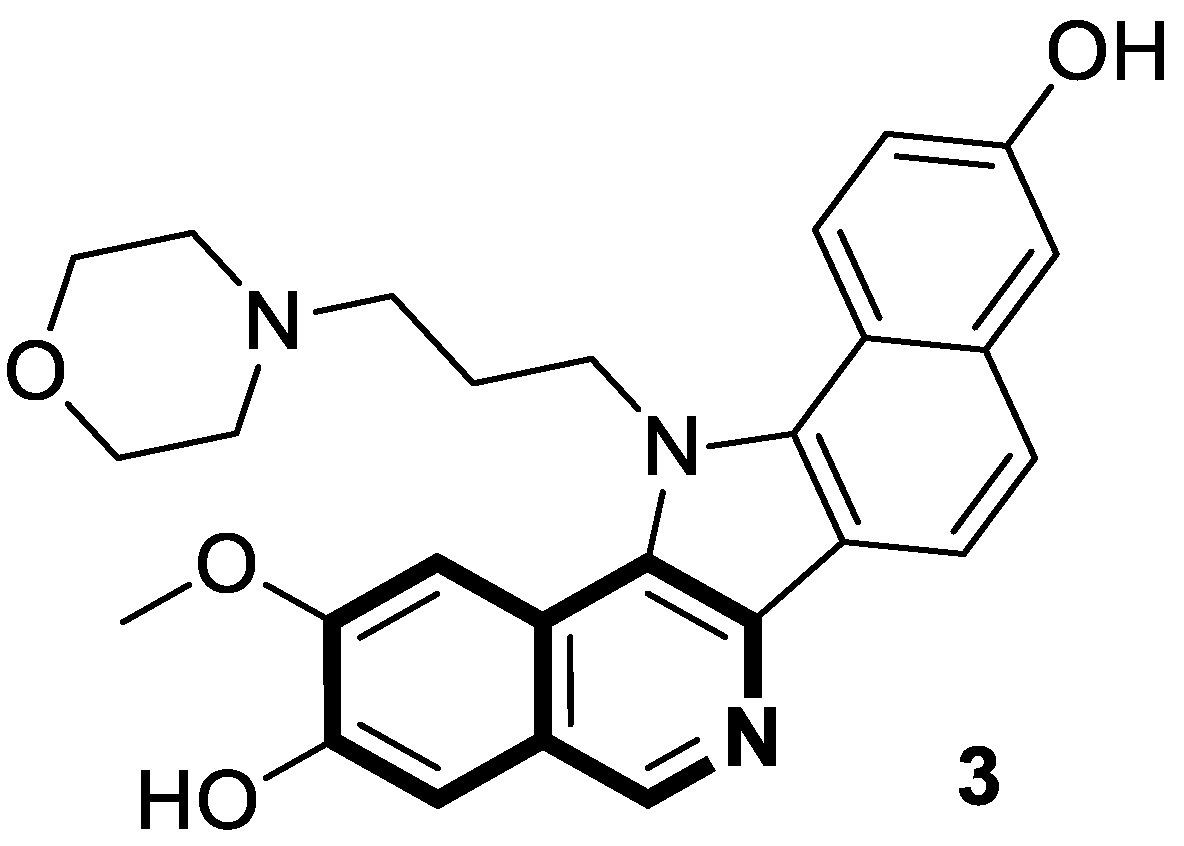

- Sakai, K.; Soshima, T.; Hirose, Y.; Ishibashi, F.; Hirao, S. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of novel benzo[6,7]indolo [3,4-c]isoquinolines as anticancer agents with topoisomerase I inhibition. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2024, 104, 129710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

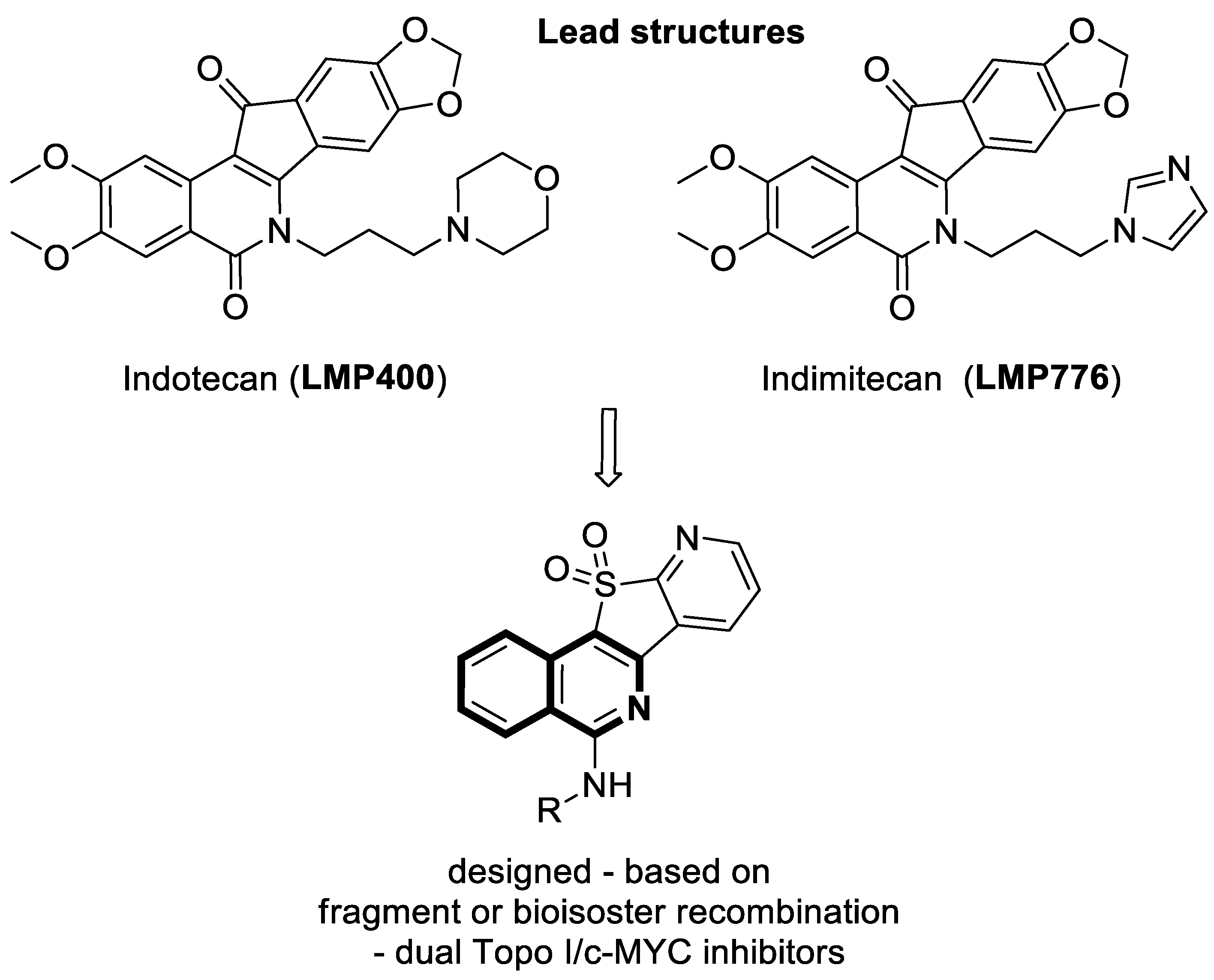

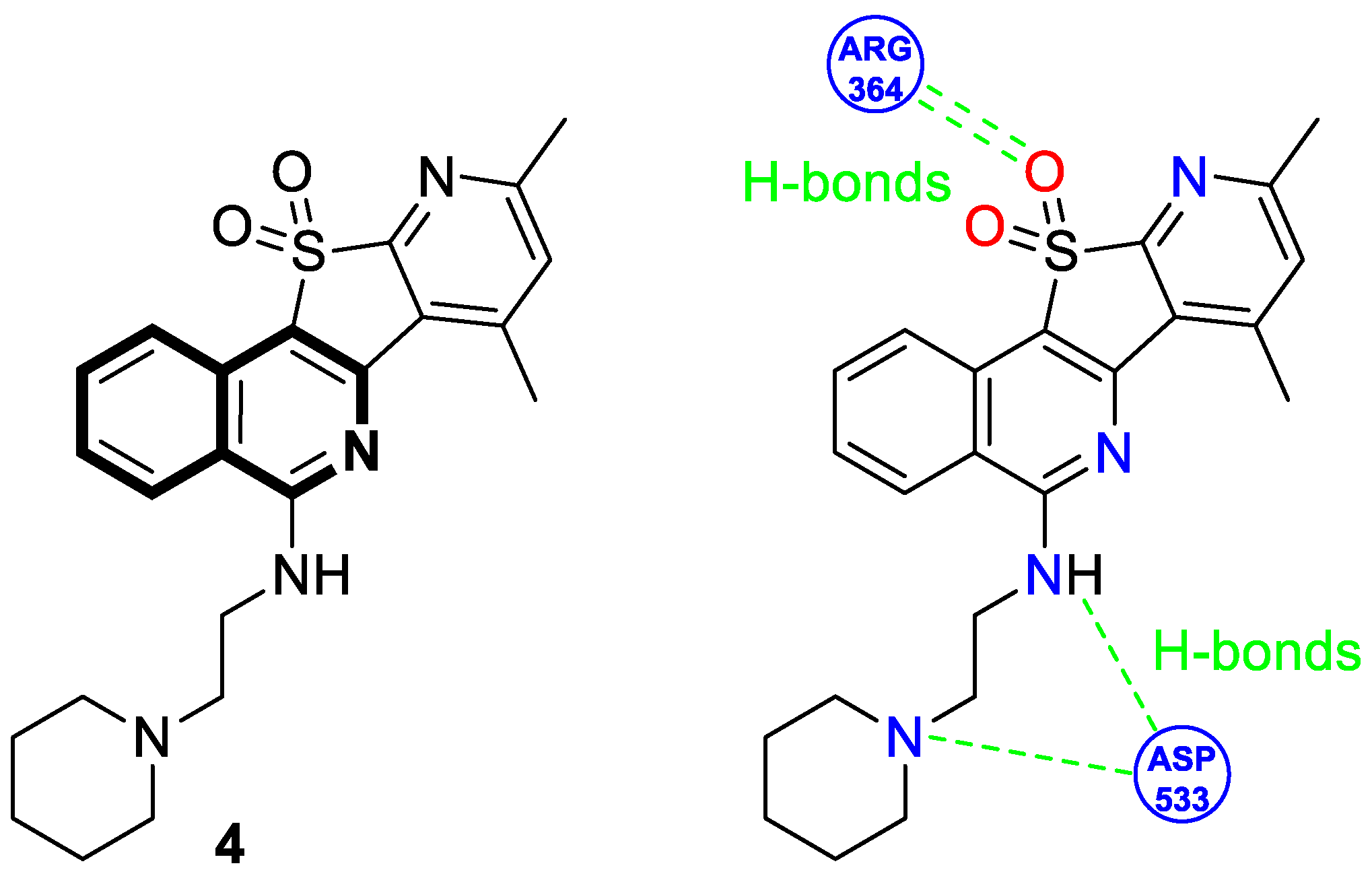

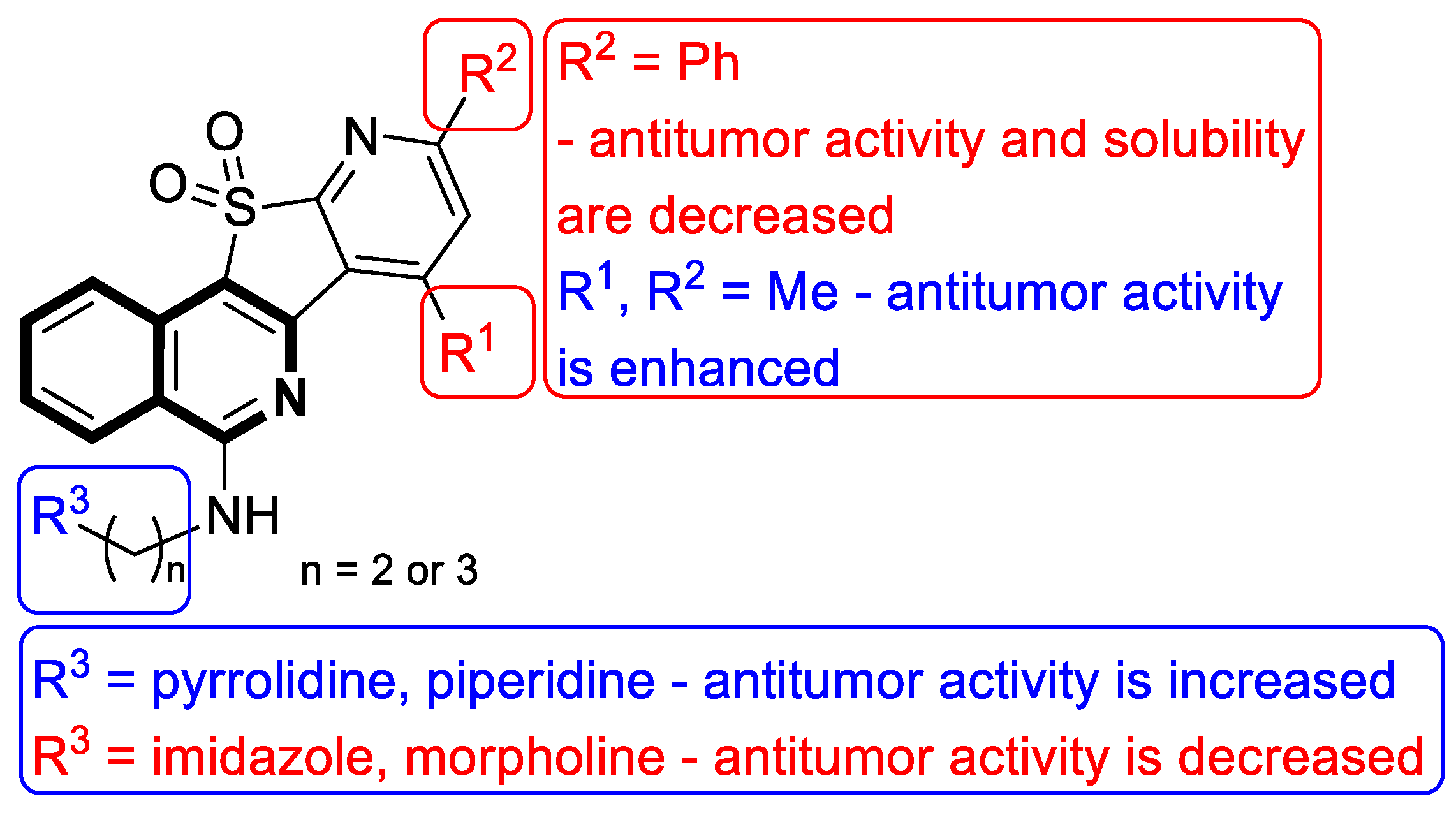

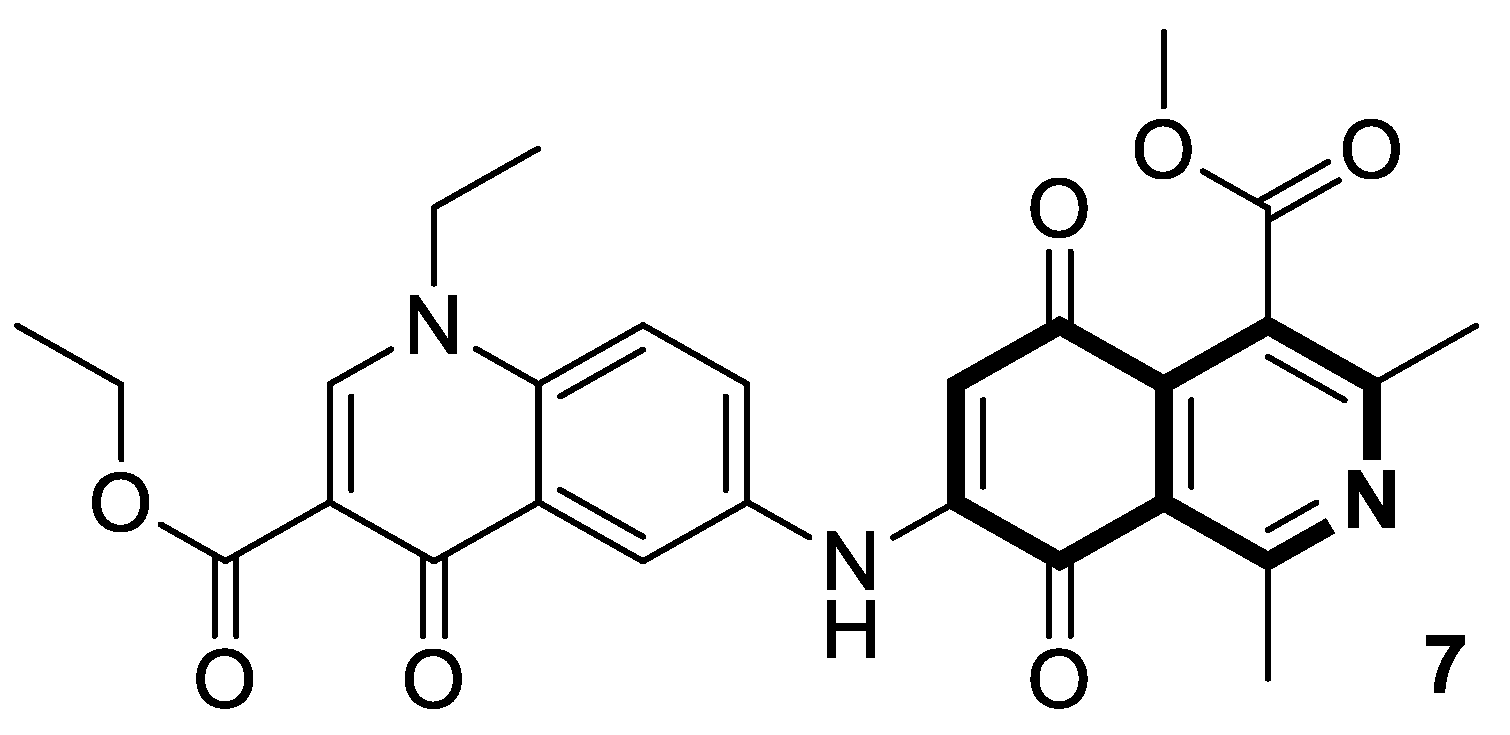

- Zheng, B.; Wang, Y.X.; Wu, Z.Y.; Li, X.W.; Qin, L.Q.; Chen, N.Y.; Su, G.F.; Su, J.C.; Pan, C.X. Design, synthesis and bioactive evaluation of Topo I/c-MYC dual inhibitors to inhibit oral cancer via regulating the PI3K/AKT/NF-κB signaling pathway. Molecules 2025, 30, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

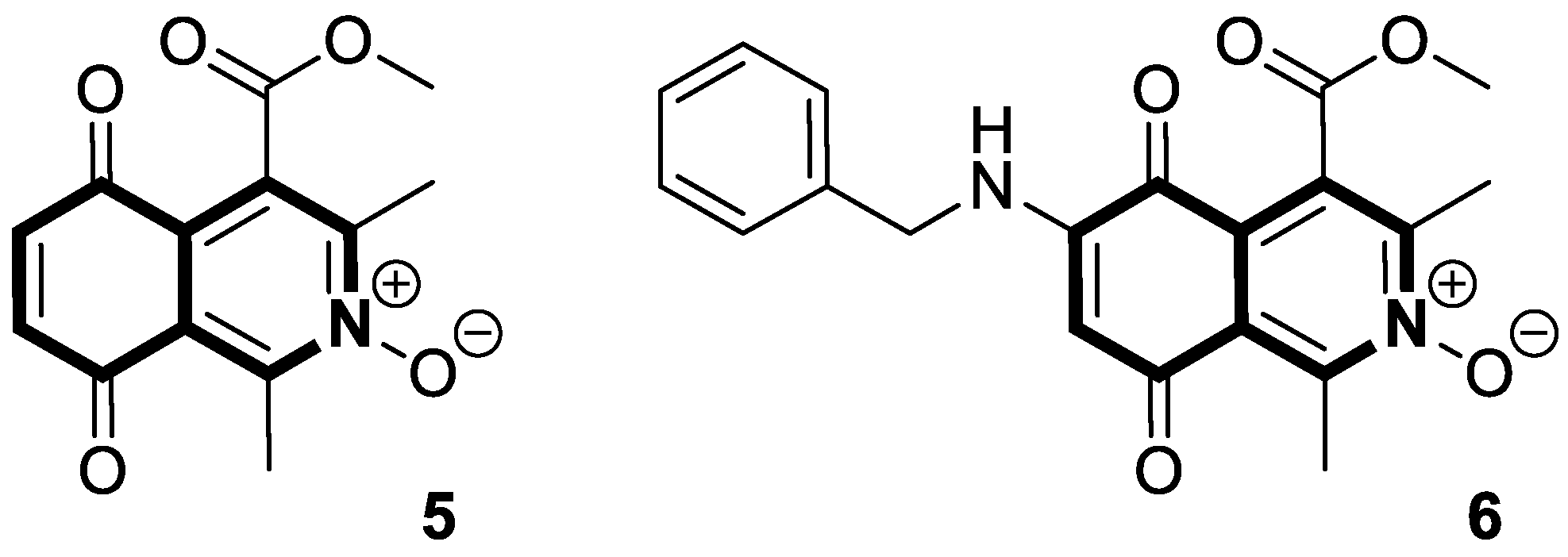

- Kruschel, R.D.; Buzid, A.; Khandavilli, U.B.R.; Lawrence, S.E.; Glennon, J.D.; McCarthy, F.O. Isoquinolinequinone N-oxides as anticancer agents effective against drug resistant cell lines. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2020, 18, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento Mello, A.L.; Sagrillo, F.S.; de Souza, A.G.; Costa, A.R.P.; Campos, V.R.; Cunha, A.C.; Imbroisi Filho, R.; da Costa Santos Boechat, F.; Sola-Penna, M.; de Souza, M.C.B.V.; et al. Selective AMPK activator leads to unfolded protein response downregulation and induces breast cancer cell death and autophagy. Life Sci. 2021, 276, 119470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolbeinsson, H.M.; Chandana, S.; Wright, G.P.; Chung, M. Pancreatic cancer: A review of current treatment and novel therapies. J. Investig. Surg. 2023, 36, 2129884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halbrook, C.J.; Lyssiotis, C.A.; Pasca di Magliano, M.; Maitra, A. Pancreatic cancer: Advances and challenges. Cell 2023, 186, 1729–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, M.H.; Beatty, G.L. Tumor microenvironment in pancreatic cancer pathogenesis and therapeutic resistance. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2023, 18, 123–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutel, A.K.; Halbrook, C.J. Barriers and opportunities for gemcitabine in pancreatic cancer therapy. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2023, 324, C540–C552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Vuthaluru, S.; Chowdhury, S.; Are, C. Global trends in the incidence and mortality of pancreatic cancer based on geographic location, socioeconomic status, and demographic shift. J. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 128, 989–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafizadeh, M.; Luo, K.; Zhang, W.; Reza Aref, A.; Zhang, X. Acquired and intrinsic gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic cancer therapy: Environmental factors, molecular profile and drug/nanotherapeutic approaches. Environ. Res. 2024, 240, 117443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayez, S.; Bruhn, T.; Feineis, D.; Assi, L.A.; Kushwaha, P.P.; Kumar, S.; Bringmann, G. Naphthylisoindolinone alkaloids: The first ring-contracted naphthylisoquinolines, from the tropical liana Ancistrocladus abbreviatus, with cytotoxic activity. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 28916–28928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajuddeen, N.; Bringmann, G. N,C-coupled naphthylisoquinoline alkaloids: A versatile new class of axially chiral natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2021, 38, 2154–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

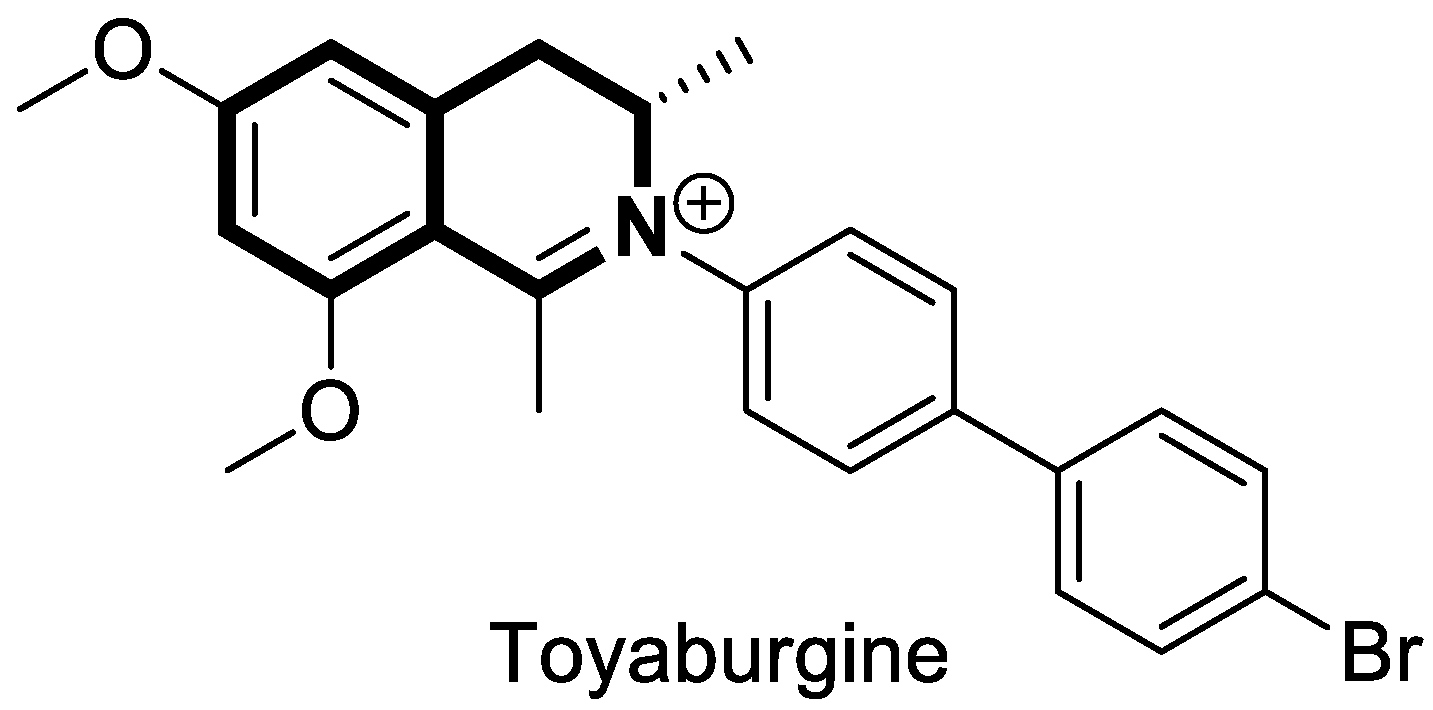

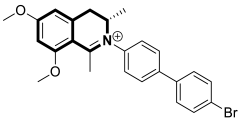

- Awale, S.; Maneenet, J.; Phan, N.D.; Nguyen, H.H.; Fujii, T.; Ihmels, H.; Soost, D.; Tajuddeen, N.; Feineis, D.; Bringmann, G. Toyaburgine, a synthetic N-biphenyl-dihydroisoquinoline inspired by related N,C-coupled naphthylisoquinoline alkaloids, with high in vivo efficacy in preclinical pancreatic cancer models. ACS Chem. Biol. 2025, 20, 917–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

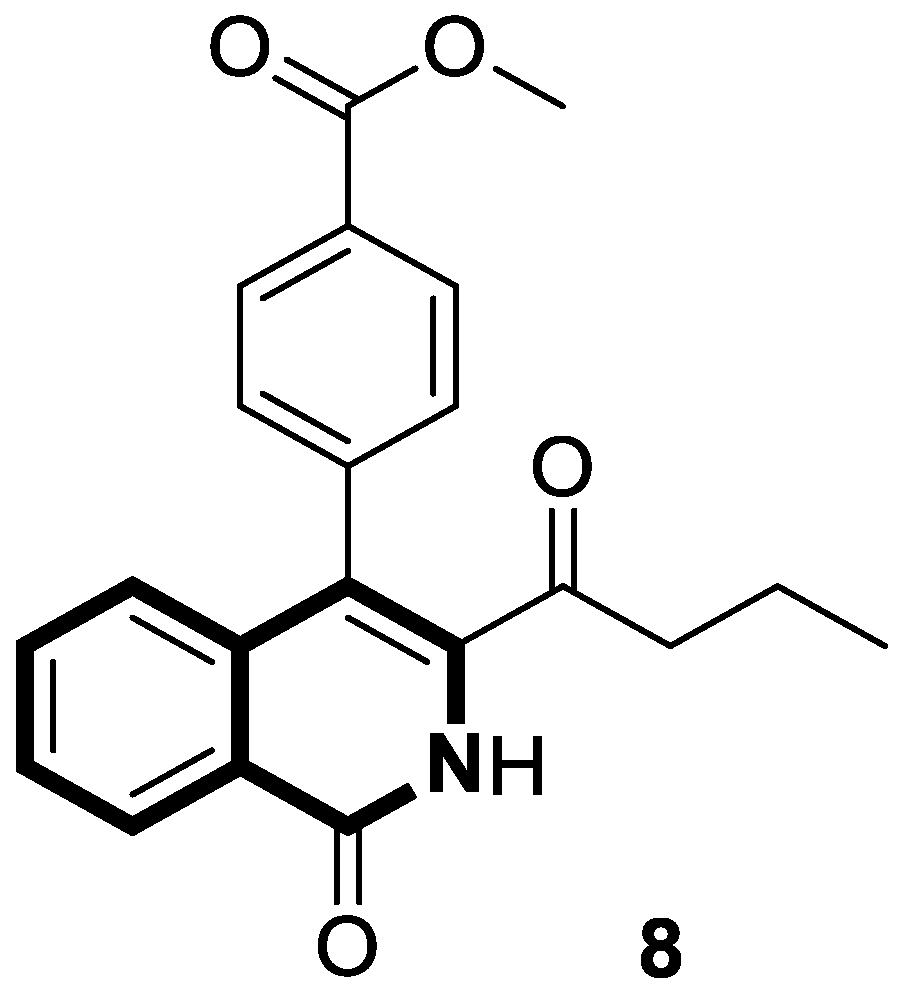

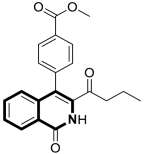

- Ma, L.; Bian, M.; Gao, H.; Zhou, Z.; Yi, W. A novel 3-acyl isoquinolin-1(2H)-one induces G2 phase arrest, apoptosis and GSDME-dependent pyroptosis in breast cancer. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

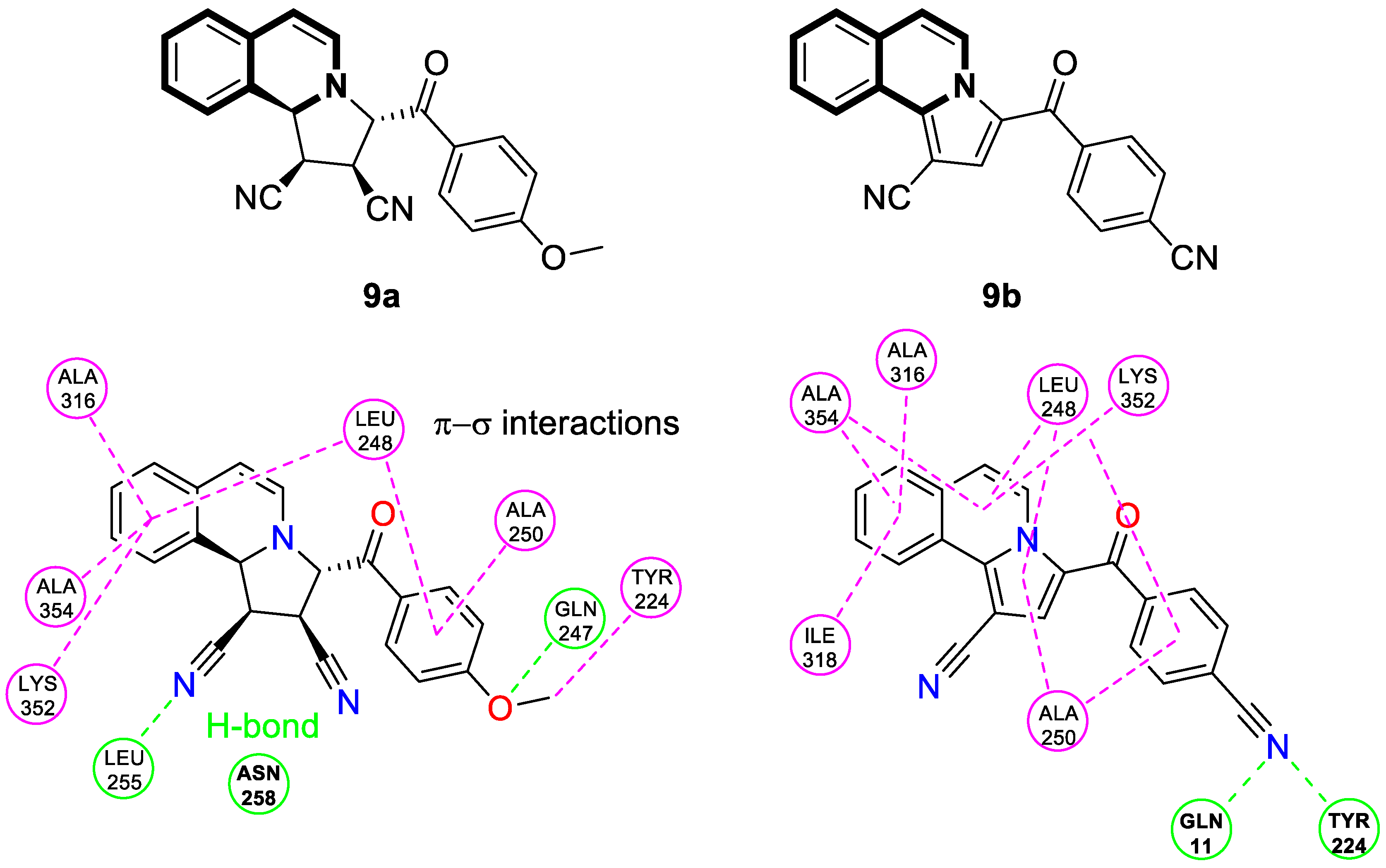

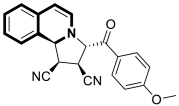

- Al-Matarneh, M.C.; Amărandi, R.M.; Mangalagiu, I.I.; Danac, R. Synthesis and biological screening of new cyano-substituted pyrrole fused (iso)quinoline derivatives. Molecules 2021, 26, 2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagawara, A.; Li, Y.; Izumi, H.; Muramori, K.; Inada, H.; Nishi, M. Neuroblastoma. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 48, 214–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, P.T.; Zannoupa, D.; Son, M.H.; Dahal, L.N.; Woolley, J.F. Neuroblastoma: An ongoing cold front for cancer immunotherapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e007798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; AlSayyad, K.; Siddiqui, K.; AlAnazi, A.; AlSeraihy, A.; AlAhmari, A.; ElSolh, H.; Ghemlas, I.; AlSaedi, H.; AlJefri, A.; et al. Pediatric high risk neuroblastoma with autologous stem cell transplant—20 years of experience. Int. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2021, 8, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainero-Alcolado, L.; Sjöberg Bexelius, T.; Santopolo, G.; Yuan, Y.; Liaño-Pons, J.; Arsenian-Henriksson, M. Defining neuroblastoma: From origin to precision medicine. Neuro-Oncology 2024, 26, 2174–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

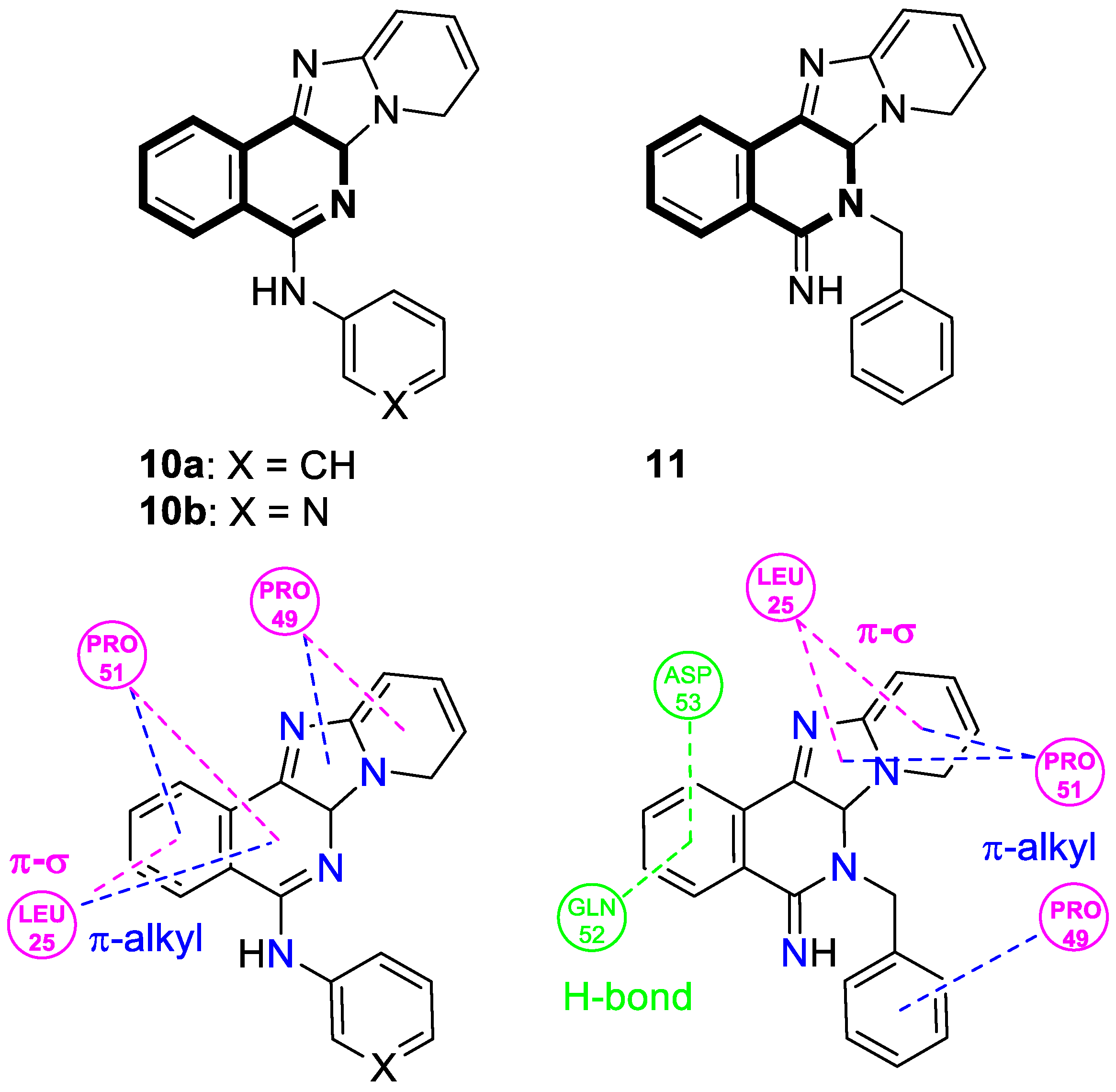

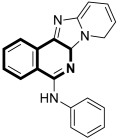

- Tber, Z.; Loubidi, M.; Jouha, J.; Hdoufane, I.; Erdogan, M.A.; Saso, L.; Armagan, G.; Berteina-Raboin, S. Pyrido[2′,1′:2,3]imidazo[4,5-c]isoquinolin-5-amines as potential cytotoxic agents against human neuroblastoma. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

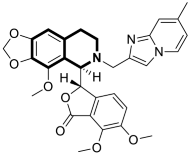

- Nemati, F.; Ata Bahmani Asl, A.; Salehi, P. Synthesis and modification of noscapine derivatives as promising future anticancer agents. Bioorganic Chem. 2024, 153, 107831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

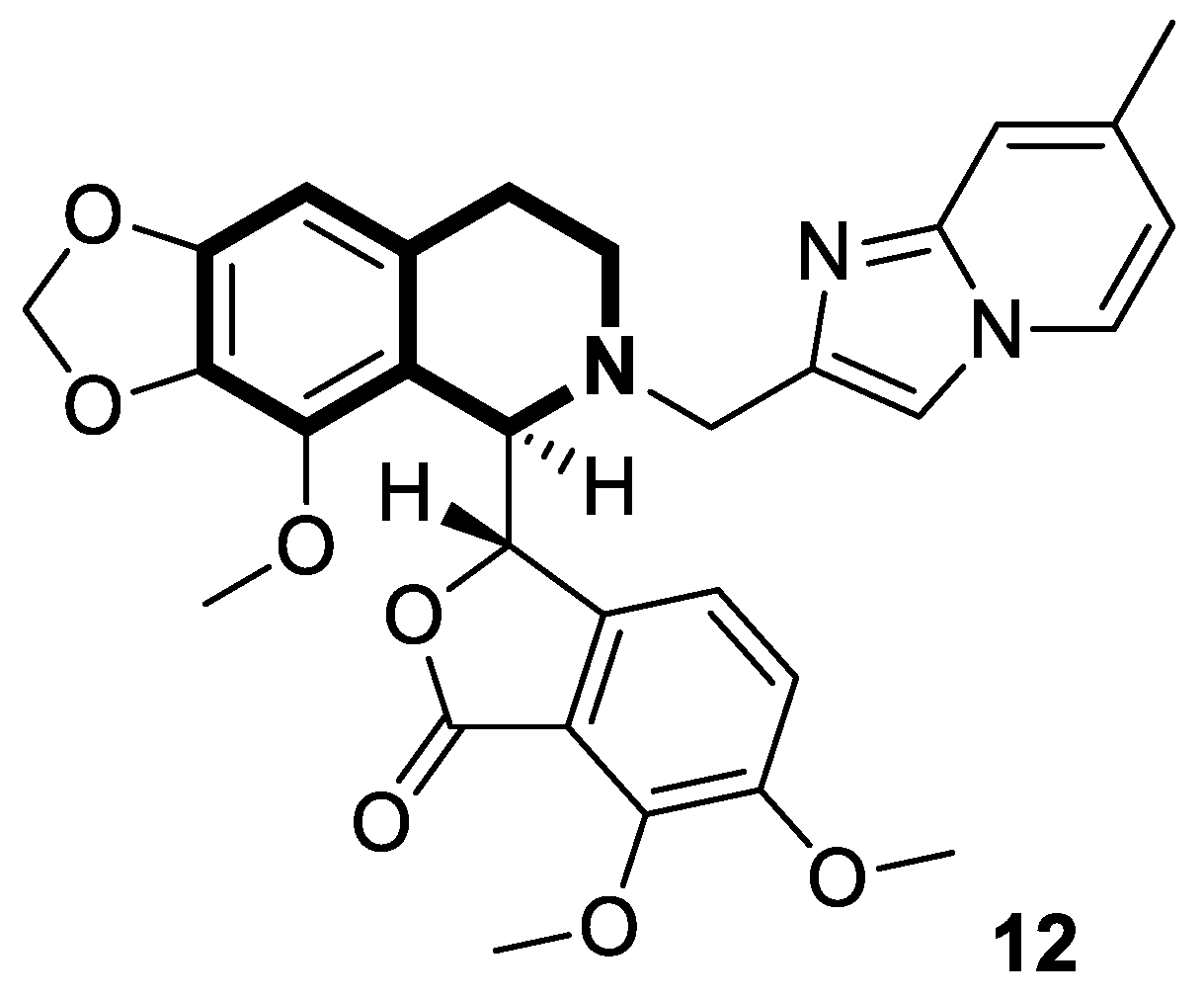

- Dash, P.; Pragyandipta, P.; Kantevari, S.; Naik, P.K. N-imidazopyridine derivatives of noscapine as potent tubulin-binding anticancer agents: Chemical synthesis and cellular evaluation. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2025, 39, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

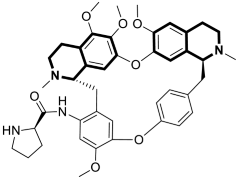

- Bhagya, N.; Chandrashekar, K.R. Tetrandrine—A molecule of wide bioactivity. Phytochemistry 2016, 125, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

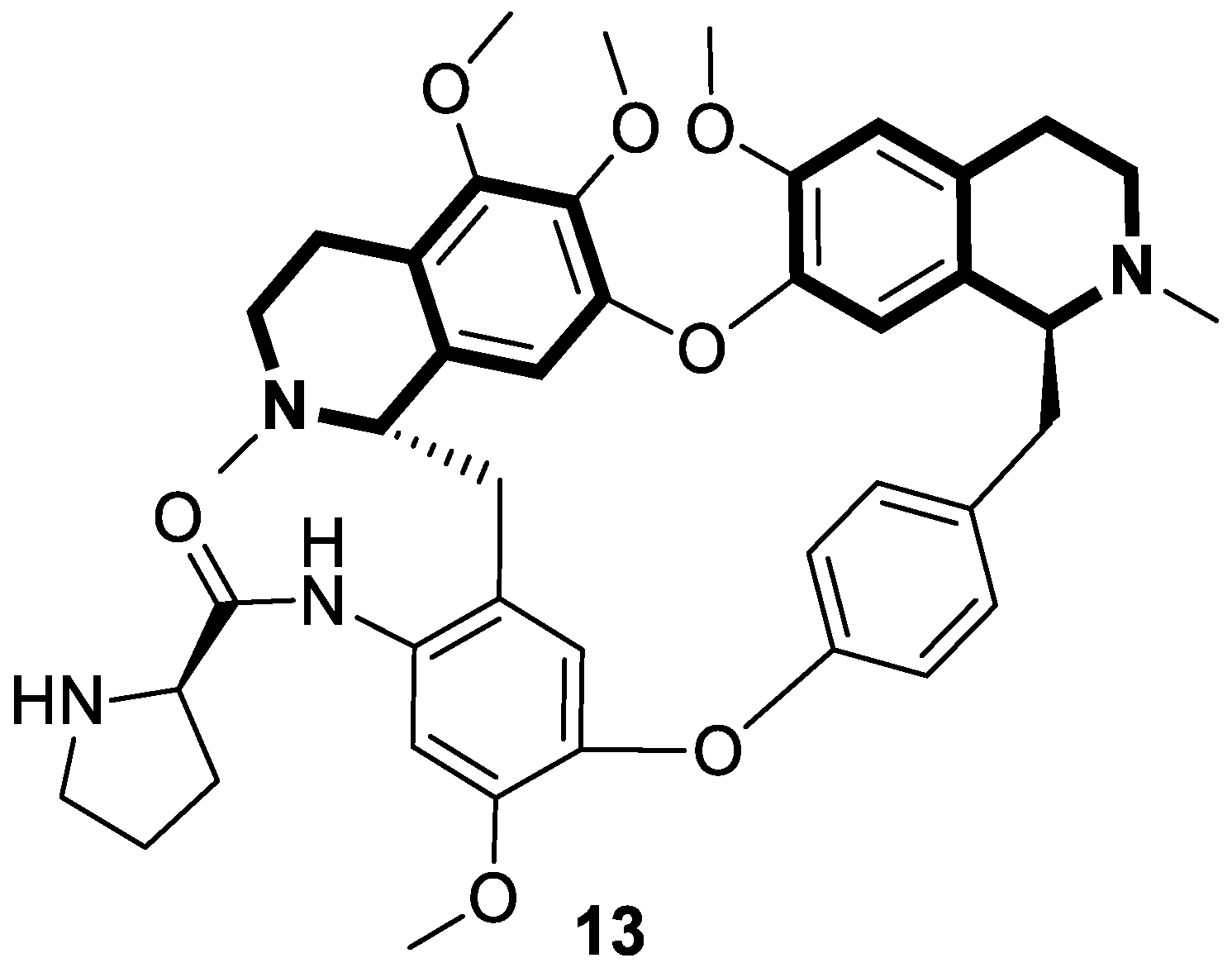

- Gao, X.Z.; Lv, X.T.; Zhang, R.R.; Luo, Y.; Wang, M.X.; Chen, J.S.; Zhang, Y.K.; Sun, B.; Sun, J.Y.; Liu, Y.F.; et al. Design, synthesis and in vitro anticancer research of novel tetrandrine and fangchinoline derivatives. Bioorganic Chem. 2021, 109, 104694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, J.; Huang, L.; Lou, H.; Chen, C.; Liu, T.; Hu, S.; Yao, Y.; Song, J.; Luo, J.; Liu, Y.; et al. Design and synthesis of novel C14-urea-tetrandrine derivatives with potent anti-cancer activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 143, 1968–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, J.; Wang, N.; Huang, L.; Liu, Y.; Ma, X.; Lou, H.; Chen, C.; Feng, Y.; Pan, W. Design and synthesis of novel tetrandrine derivatives as potential anti-tumor agents against human hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 127, 554–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Qu, T.L.; Yang, Y.F.; Xu, J.F.; Li, X.W.; Zhao, Z.B.; Guo, Y.W. Design and synthesis of new tetrandrine derivatives and their antitumor activities. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2016, 18, 966–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Lan, J.; Chen, C.; Hu, S.; Song, J.; Liu, W.; Zeng, X.; Lou, H.; Ben-David, Y.; Pan, W. Design, synthesis and bioactivity investigation of tetrandrine derivatives as potential anti-cancer agents. Med. Chem. Comm. 2018, 9, 1131–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, C.; Zhao, S.; Jiao, B. Design, synthesis and biological activities of tetrandrine and fangchinoline derivatives as antitumer agents. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 533–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütz, R.; Müller, M.; Geisslinger, F.; Vollmar, A.; Bartel, K.; Bracher, F. Synthesis, biological evaluation and toxicity of novel tetrandrine analogues. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 207, 112810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhao, L.; Zhao, F.; Yang, G.; Wang, J.J. Tetrandrine suppresses lung cancer growth and induces apoptosis, potentially via the VEGF/HIF-1α/ICAM-1 signaling pathway. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 15, 7433–7437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Xu, J.; Guo, J.; Shang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, T. The enhancement of tetrandrine to gemcitabine-resistant PANC-1 cytochemical sensitivity involves the promotion of PI3K/Akt/mTOR-mediated apoptosis and AMPK-regulated autophagy. Acta Histochem. 2021, 123, 151769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.C.; Zhang, R.; Hu, S.C.; Zhang, H.; Yang, D.; Zhang, W.L.; Zhao, Y.L.; Cui, D.B.; Li, Y.J.; Pan, W.D.; et al. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of N14-amino acid-substituted tetrandrine derivatives as potential antitumor agents against human colorectal cancer. Molecules 2022, 27, 4040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.C.; Yang, J.; Chen, C.; Song, J.R.; Pan, W.D. Design, synthesis of novel Tetrandrine-14-l-amino acid and tetrandrine-14-l-amino acid-urea derivatives as potential anti-cancer agents. Molecules 2020, 25, 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

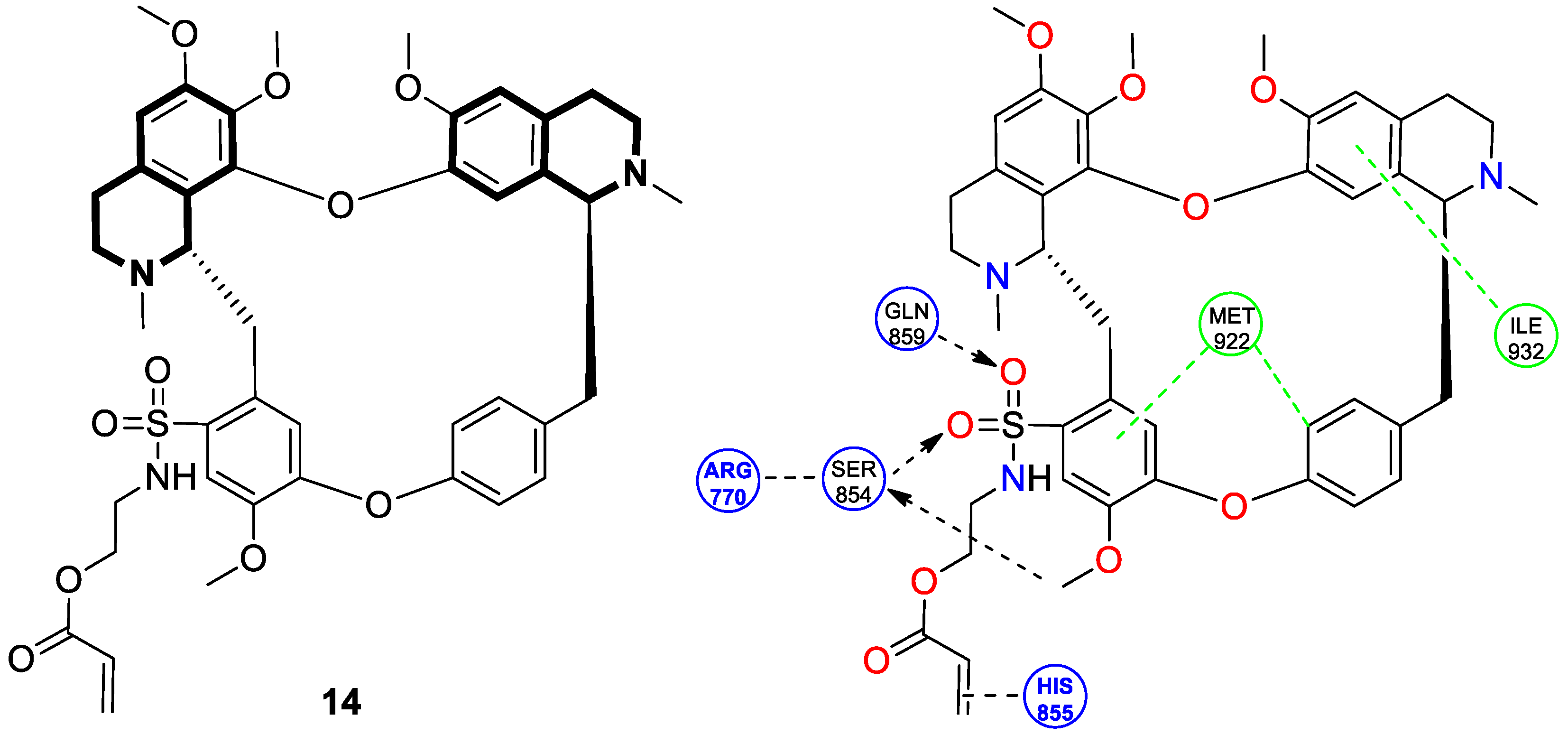

- Ling, J.; Li, X.; Wang, M.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, C.; Ren, Q.; Zeng, Y.; Wang, C.; et al. Novel sulfonyl-substituted tetrandrine derivatives for colon cancer treatment by inducing mitochondrial apoptosis and inhibiting PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Bioorganic Chem. 2024, 143, 107069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faheem; Karan Kumar, B.; Chandra Sekhar, K.V.G.; Chander, S.; Kunjiappan, S.; Murugesan, S. Medicinal chemistry perspectives of 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline analogs—Biological activities and SAR studies. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 12254–12287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

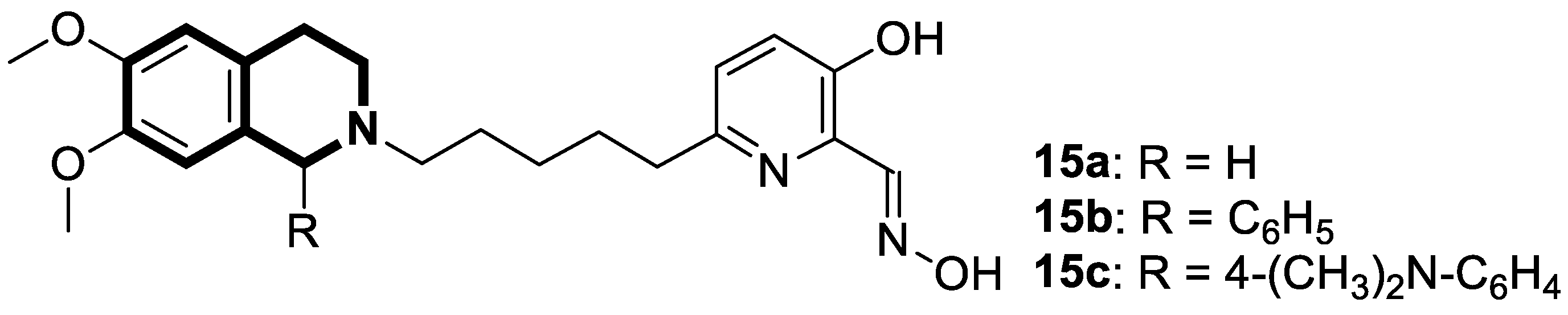

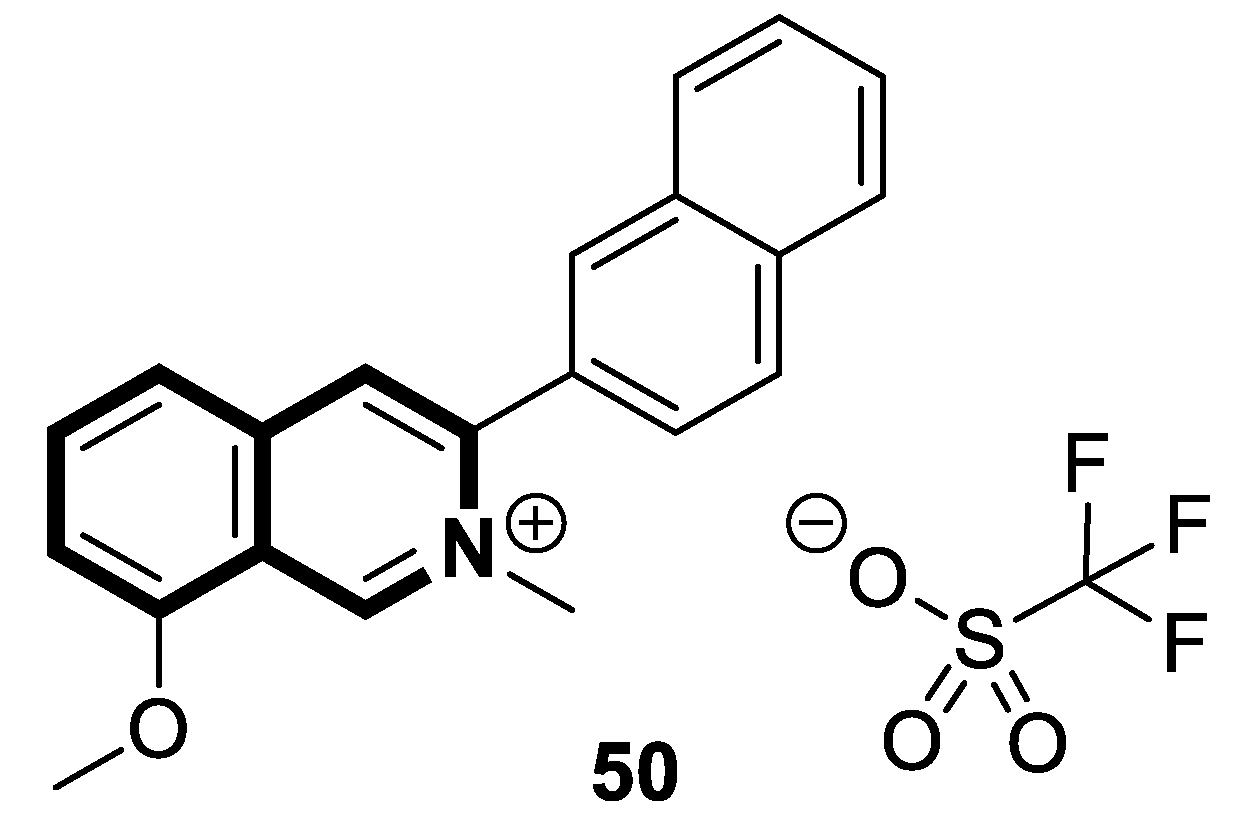

- Jin, Y.; Chen, F.; Long, Y.; Luo, J.; Guo, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, W. Design, synthesis, and mechanism study of novel isoquinoline derivatives containing an oxime moiety as antifungal agents. Mol. Divers. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zandona, A.; Madunić, J.; Miš, K.; Maraković, N.; Dubois-Geoffroy, P.; Cavaco, M.; Mišetić, P.; Padovan, J.; Castanho, M.; Jean, L.; et al. Biological response and cell death signaling pathways modulated by tetrahydroisoquinoline-based aldoximes in human cells. Toxicology 2023, 494, 153588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandona, A.; Jurić, M.; Jean, L.; Renard, P.Y.; Katalinić, M. Assessment of cytotoxic properties of tetrahydroisoquinoline oximes in breast, prostate and glioblastoma cancer cells. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2025, 48, 856–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heigener, D.F.; Reck, M. Crizotinib. In Small Molecules in Oncology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 211, pp. 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timm, A.; Kolesar, J.M. Crizotinib for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2013, 70, 943–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Qi, X.; Huang, Y.; Liu, D.; Zhou, F.; Zhou, C. Ceritinib (LDK378): A potent alternative to crizotinib for ALK-rearranged non–small-cell lung cancer. Clin. Lung Cancer 2015, 16, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

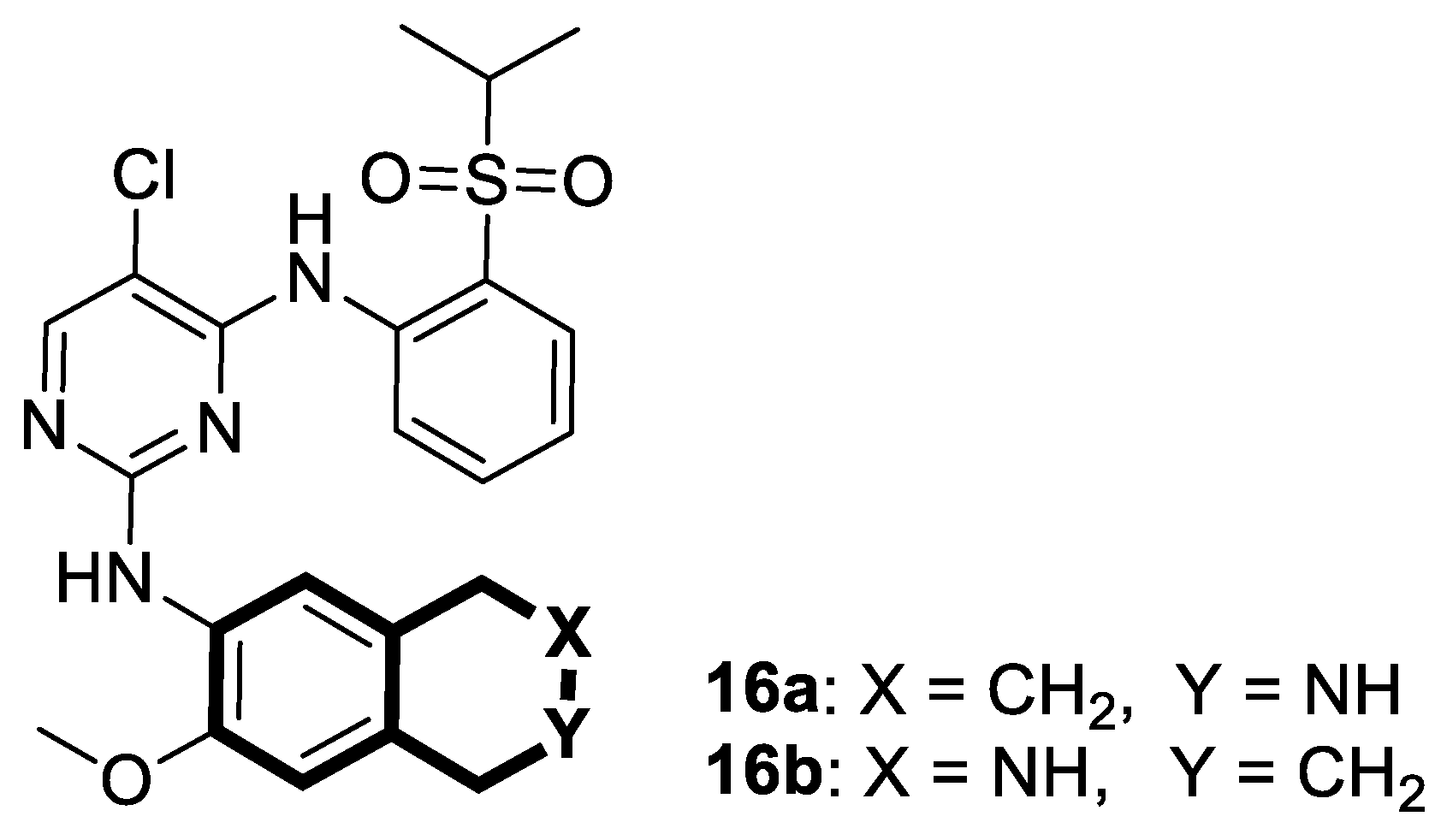

- Achary, R.; Yun, J.I.; Park, C.; Mathi, G.R.; Lee, J.Y.; Ha, J.D.; Chae, C.H.; Ahn, S.; Park, C.; Lee, C.O.; et al. Discovery of novel tetrahydroisoquinoline-containing pyrimidines as ALK inhibitors. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2016, 24, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

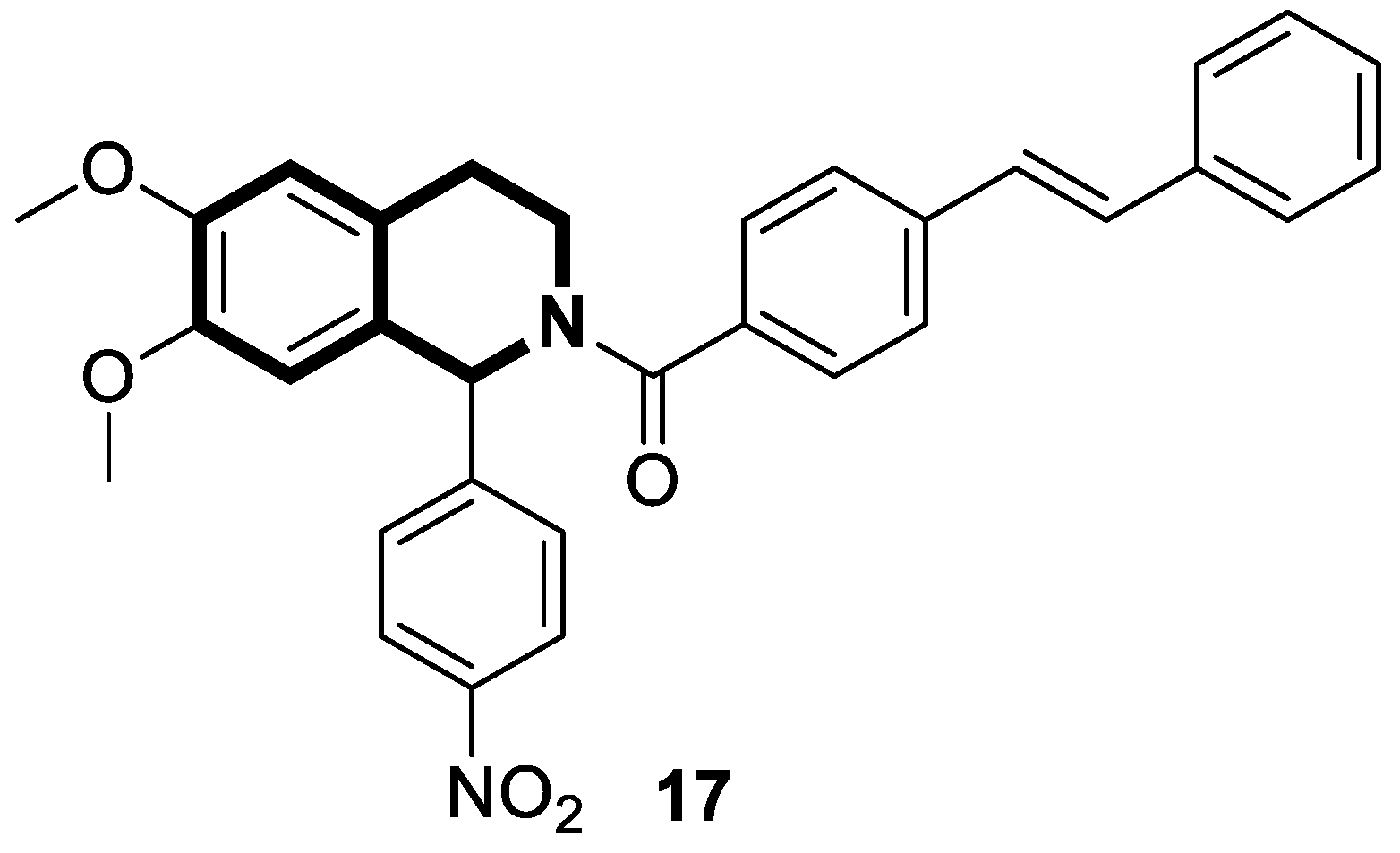

- Li, B.; Wang, J.; Yuan, M.; Miao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of tetrahydroisoquinoline stilbene derivatives as potential antitumor candidates. Chem. Biol. Drug 2023, 101, 364–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

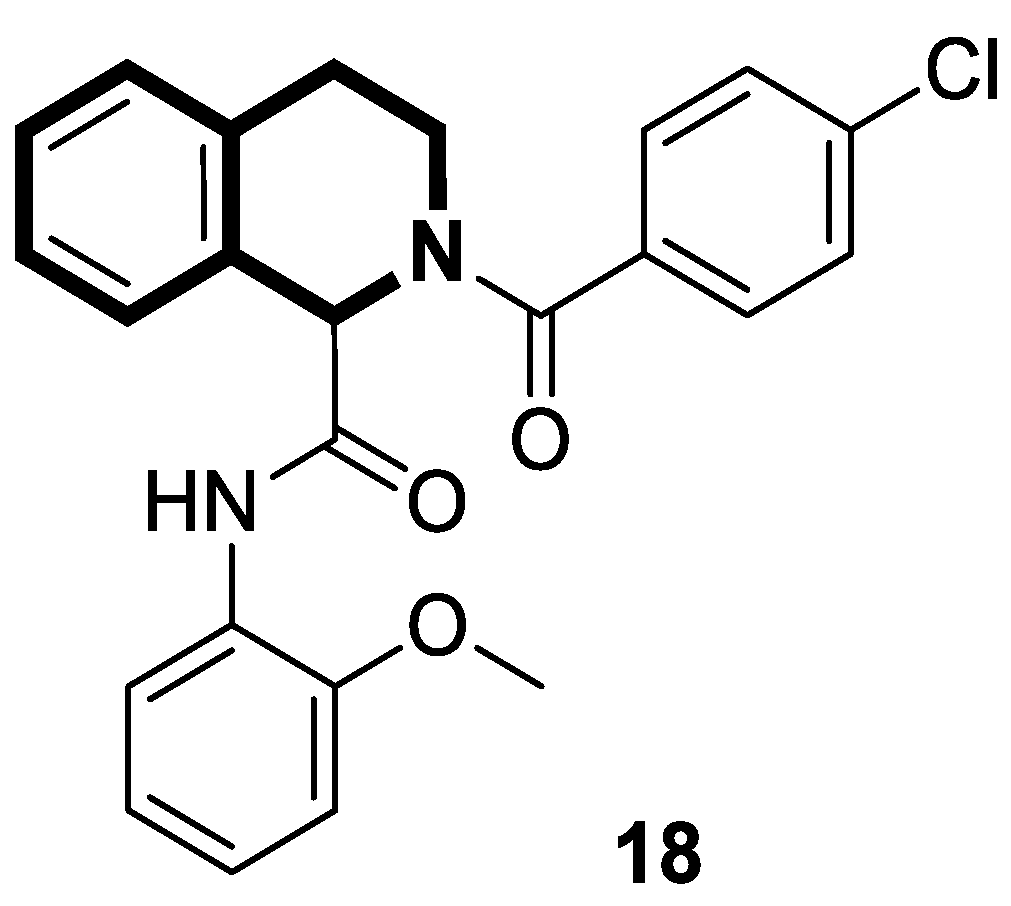

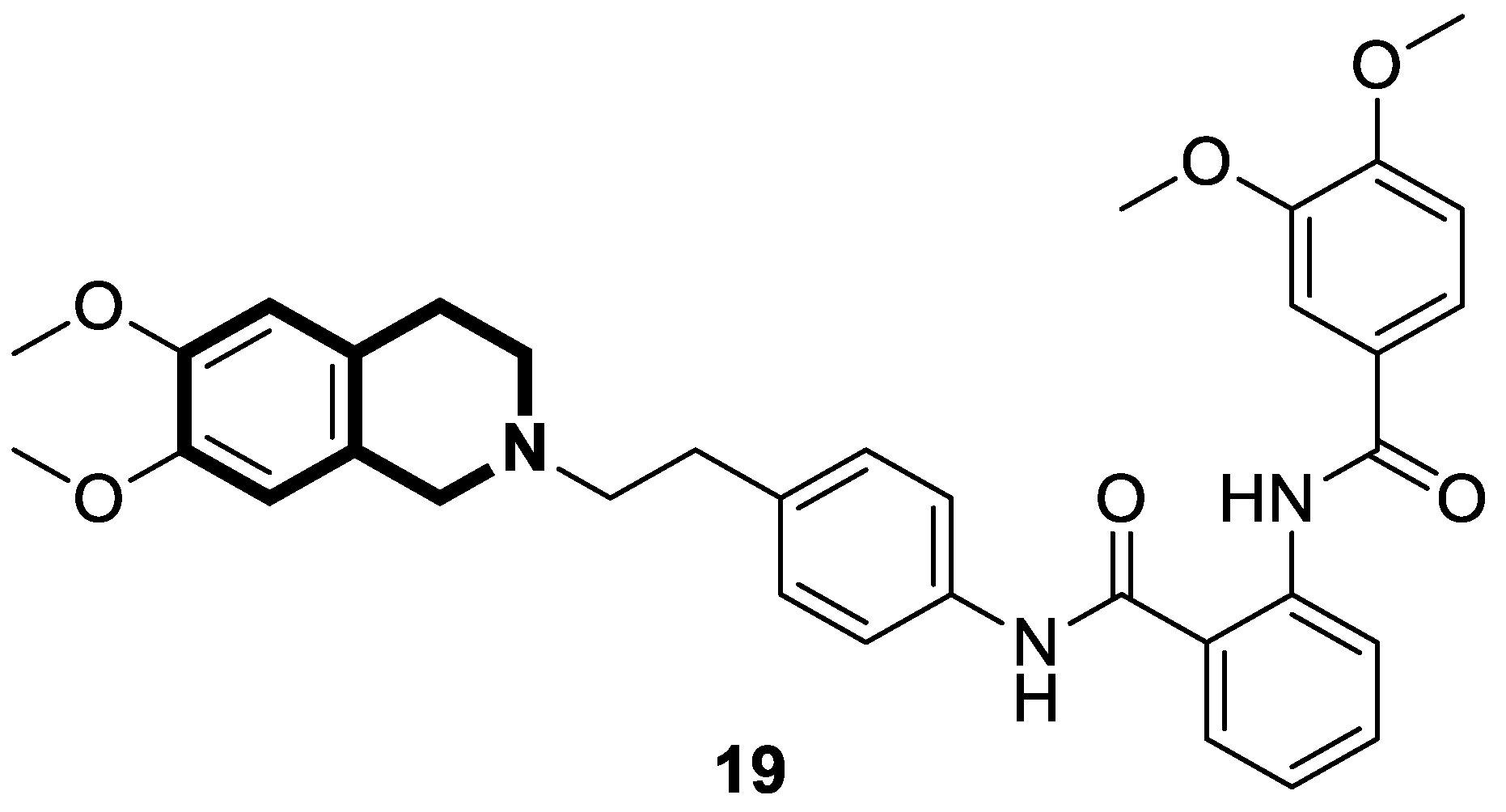

- Sim, S.; Lee, S.; Ko, S.; Phuong Bui, B.; Linh Nguyen, P.; Cho, J.; Lee, K.; Kang, J.S.; Jung, J.K.; Lee, H. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of potent 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline derivatives as anticancer agents targeting NF-κB signaling pathway. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2021, 46, 116371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Li, Y.; Ma, F.; Wu, Z.; Li, Z.; Chen, Z.S.; Cheng, X.; Qin, J.J.; Dong, J. Synthesis and evaluation of WK-X-34 derivatives as P-glycoprotein (P-gp/ABCB1) inhibitors for reversing multidrug resistance. RSC Med. Chem. 2023, 15, 506–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.; Sun, S.; Feng, H.; Tan, Z.; Zhao, J.; Wu, Y.; Yuan, W.; Li, Z.; Qiu, J.; Niu, M.; et al. Discovery of novel third generation P-glycoprotein inhibitors bearing an azo moiety with MDR-reversing effect. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 280, 116943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kono, Y.; Kawahara, I.; Shinozaki, K.; Nomura, I.; Marutani, H.; Yamamoto, A.; Fujita, T. Characterization of P-glycoprotein inhibitors for evaluating the effect of P-glycoprotein on the intestinal absorption of drugs. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

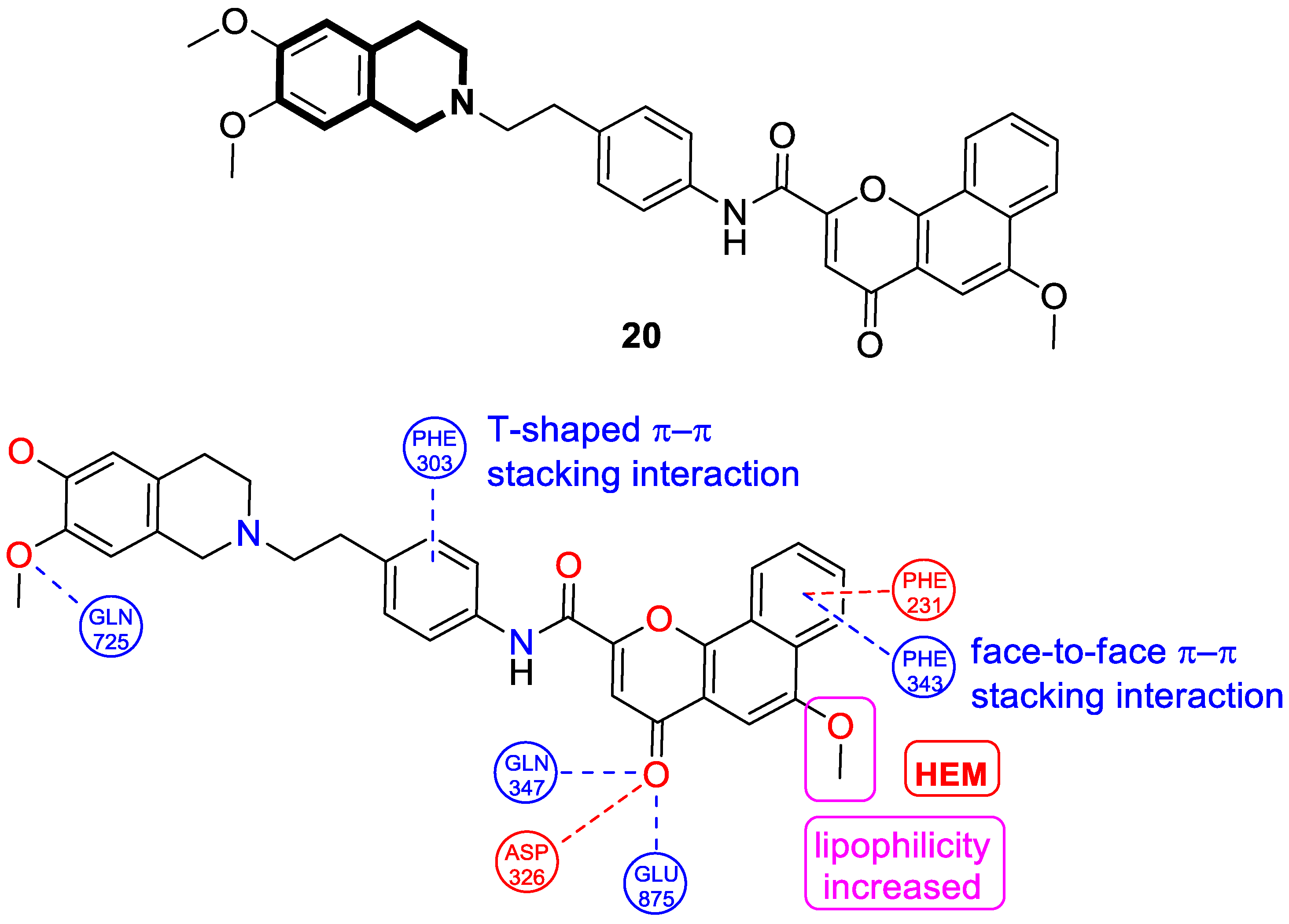

- Dong, J.; Li, Y.; Jin, Z.; Wu, Z.; Cai, M.; Pan, G.; Ye, W.; Zhou, W.; Li, Z.; Tian, S.; et al. Synthesis and evaluation of novel tetrahydroisoquinoline-benzo[h]chromen-4-one conjugates as dual ABCB1/CYP1B1 inhibitors for overcoming MDR in cancer. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2024, 114, 117944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

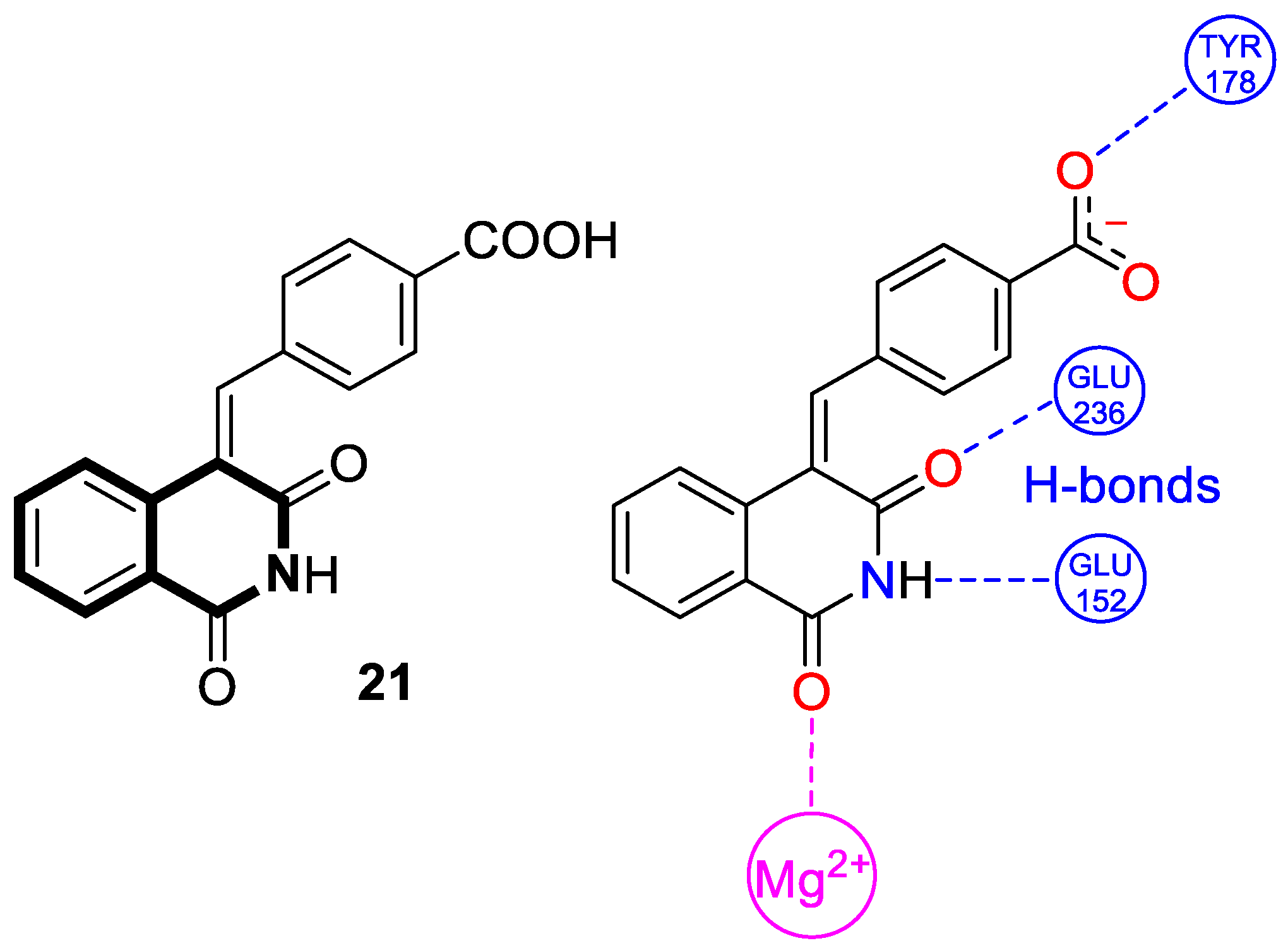

- Kankanala, J.; Marchand, C.; Abdelmalak, M.; Aihara, H.; Pommier, Y.; Wang, Z. Isoquinoline-1,3-diones as selective inhibitors of tyrosyl DNA phosphodiesterase II (TDP2). J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 2734–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senaweera, S.; He, T.; Cui, H.; Aihara, H.; Wang, Z. 4-Benzylideneisoquinoline-1,3(2H,4H)-diones as tyrosyl DNA phosphodiesterase 2 (TDP2) inhibitors. Med. Chem. Res. 2021, 30, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

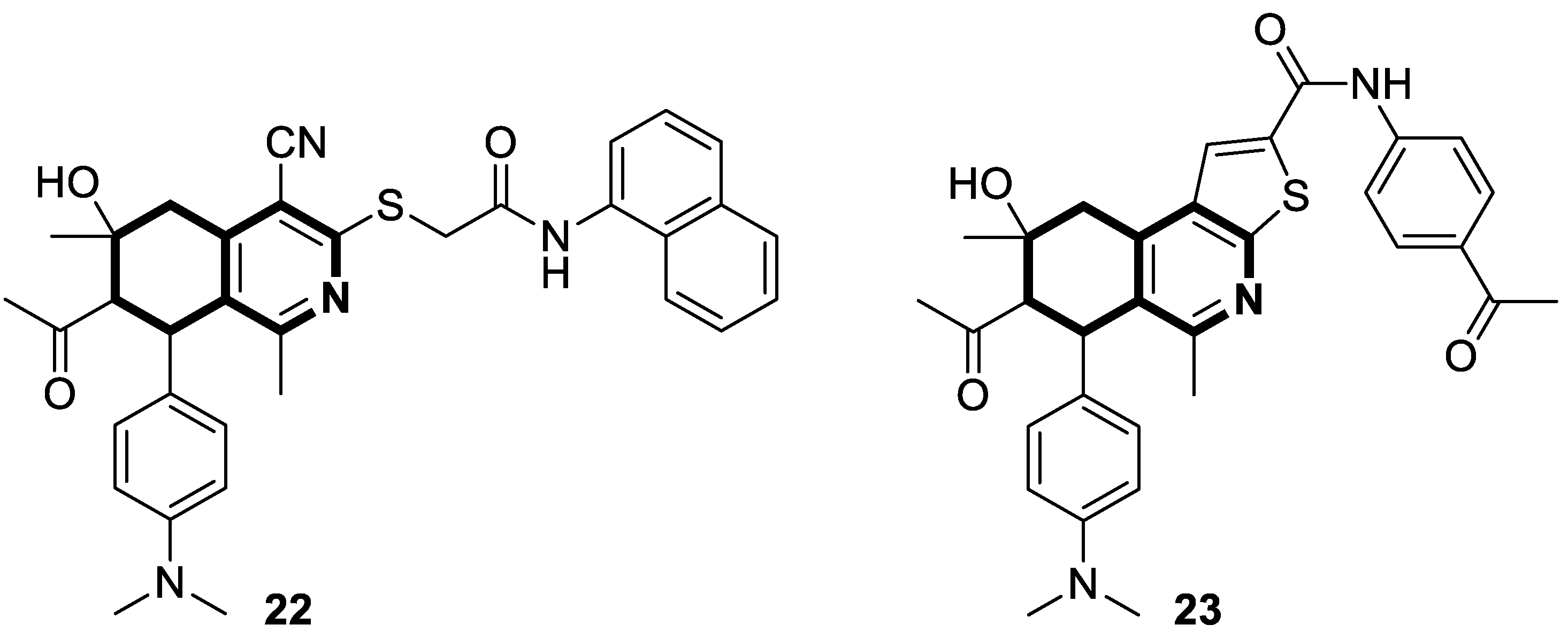

- Sayed, E.M.; Bakhite, E.A.; Hassanien, R.; Farhan, N.; Aly, H.F.; Morsy, S.G.; Hassan, N.A. Novel tetrahydroisoquinolines as DHFR and CDK2 inhibitors: Synthesis, characterization, anticancer activity and antioxidant properties. BMC Chem. 2024, 18, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

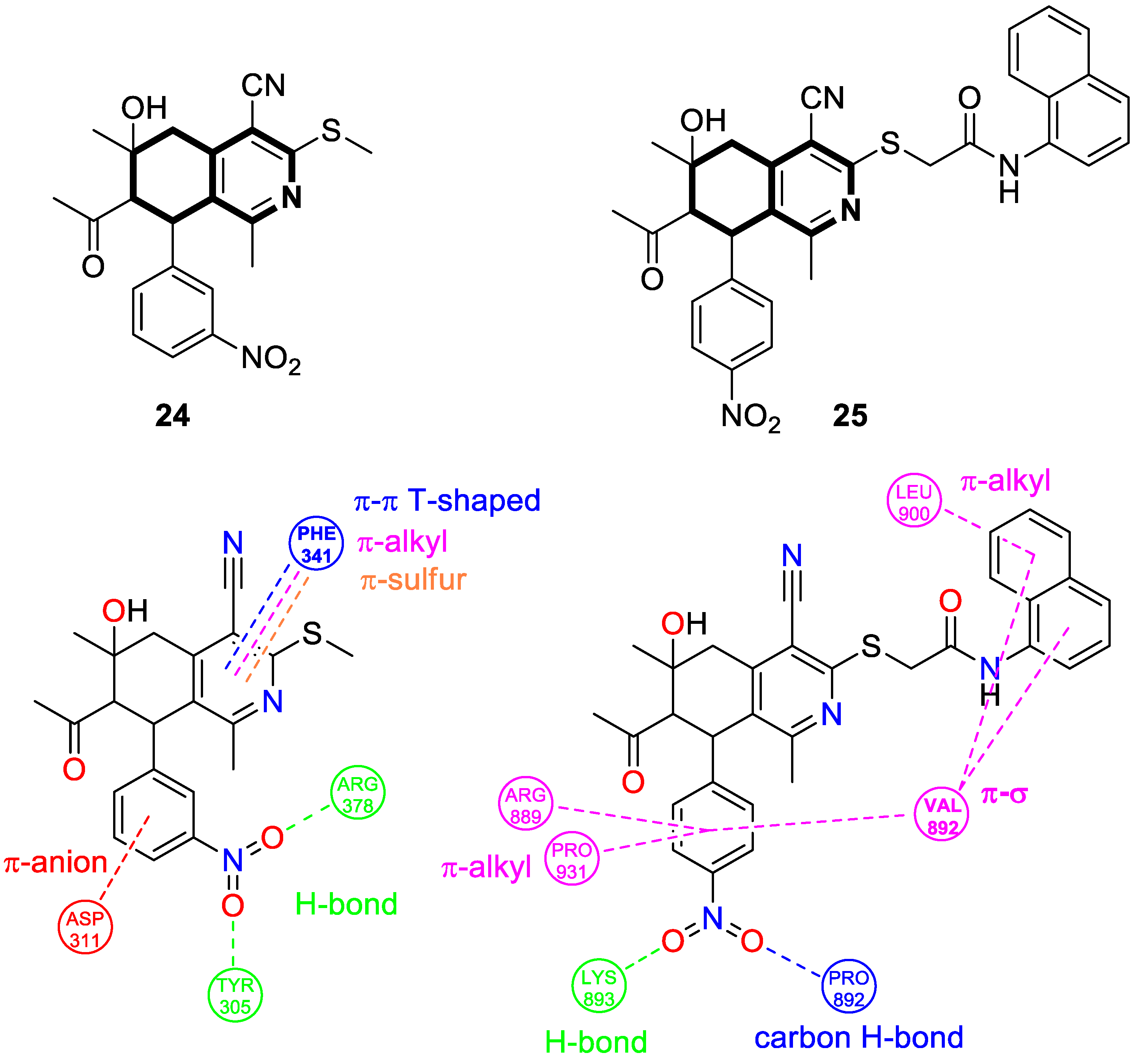

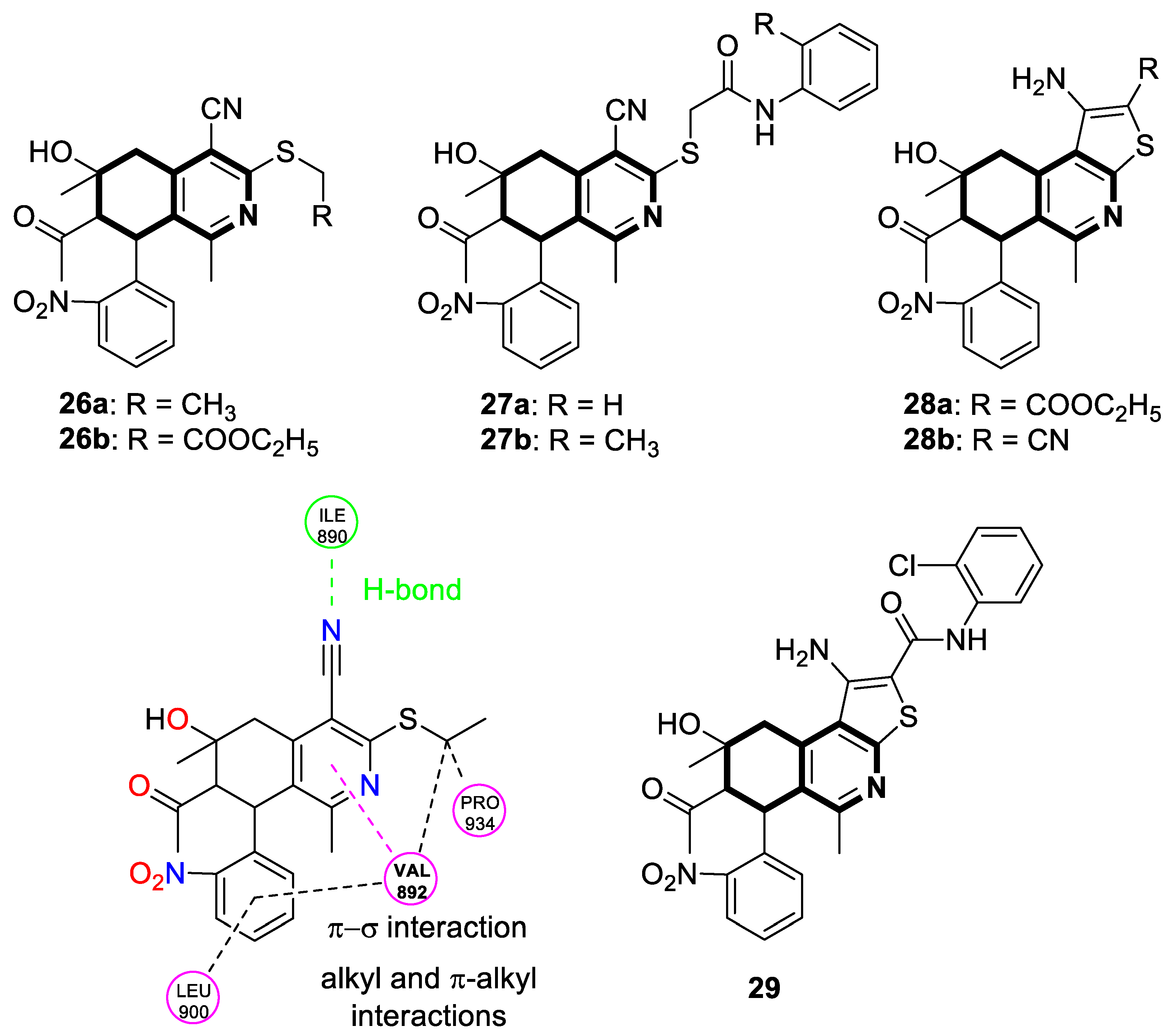

- Bakhite, E.A.; Hassanien, R.; Farhan, N.; Sayed, E.M.; Sharaky, M. New tetrahydroisoquinolines bearing nitrophenyl group targeting HSP90 and RET enzymes: Synthesis, characterization and biological evaluation. BMC Chem. 2025, 19, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saddik, A.A.; Bakhite, E.A.; Hassanien, R.; Farhan, N.; Sayed, E.M.; Sharaky, M. New 5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-isoquinolines bearing 2-nitrophenyl group targeting RET enzyme: Synthesis, anticancer activity, apoptotic induction and cell cycle arrest. Chem. Biodivers. 2025, 22, e202402758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

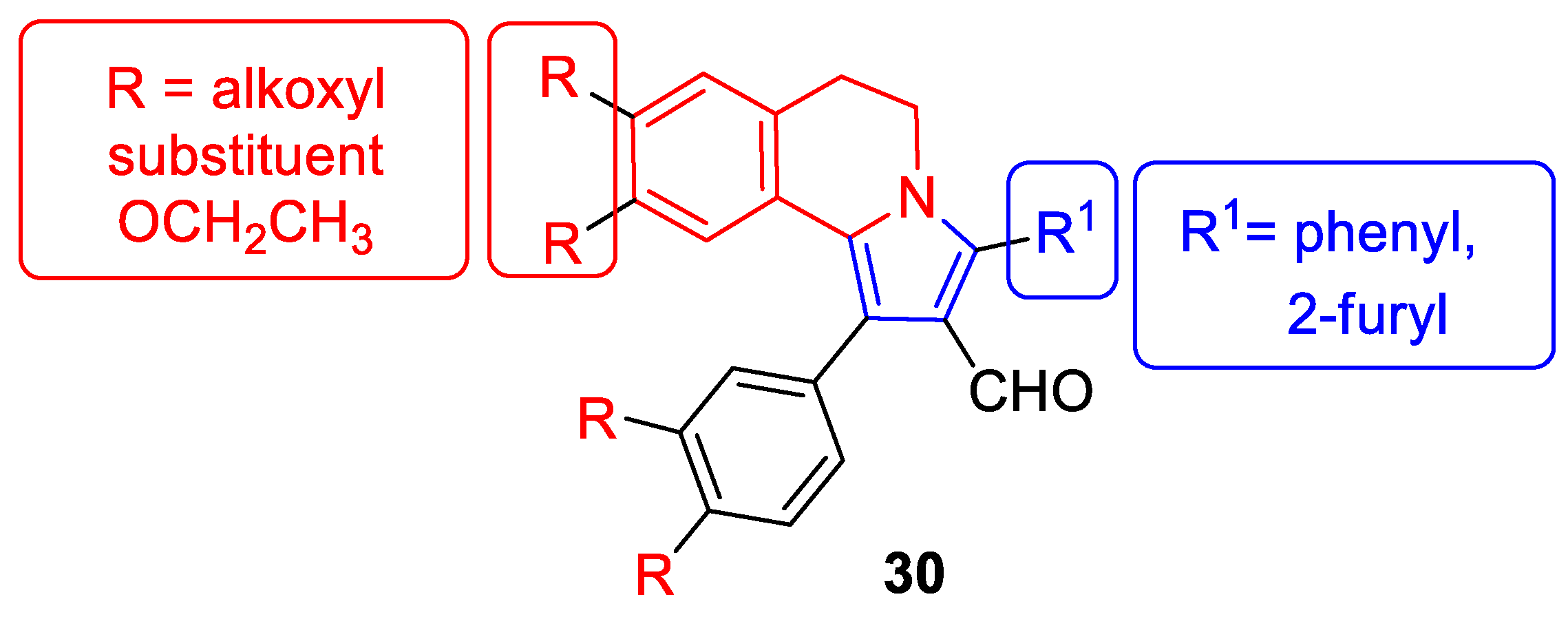

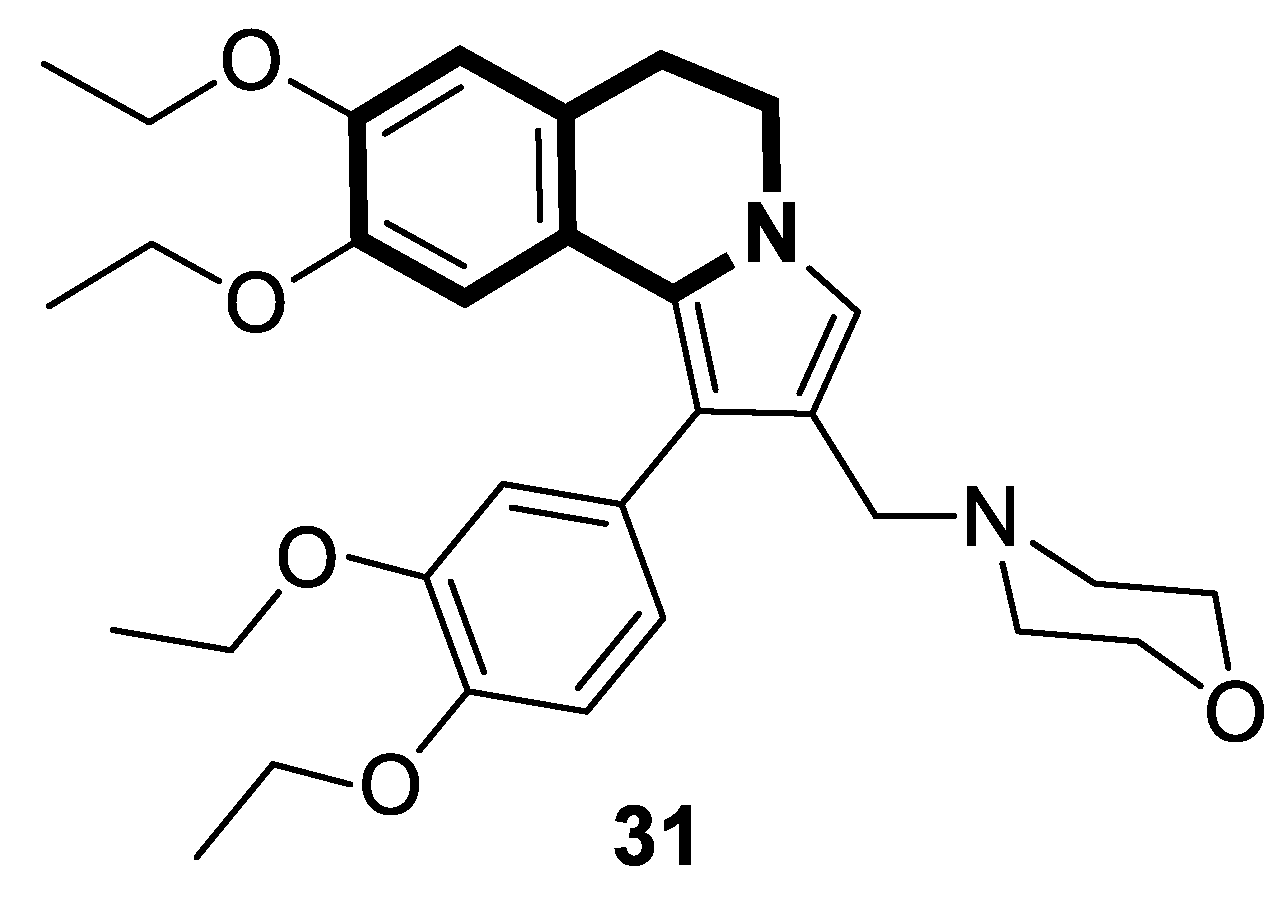

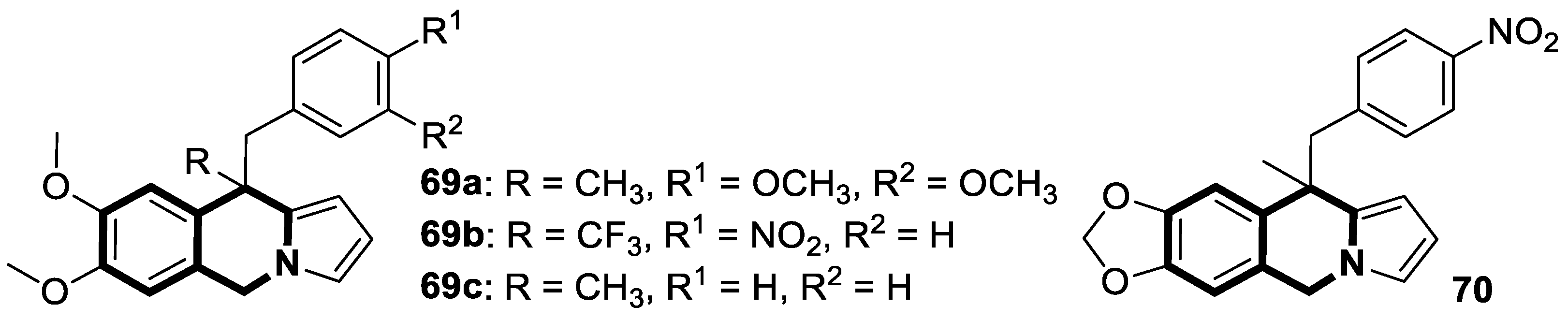

- García Maza, L.J.; Salgado, A.M.; Kouznetsov, V.V.; Meléndez, C.M. Pyrrolo[2,1-a]isoquinoline scaffolds for developing anti-cancer agents. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 1710–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matveeva, M.D.; Purgatorio, R.; Voskressensky, L.G.; Altomare, C.D. Pyrrolo[2,1-a]isoquinoline scaffold in drug discovery: Advances in synthesis and medicinal chemistry. Future Med. Chem. 2019, 11, 2735–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pässler, U.; Knölker, H.J. The pyrrolo[2,1-a]isoquinoline alkaloids. In The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Biology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 70, pp. 79–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.L. Recent progress in the synthesis of pyrrolo[2,1-a]isoquinolines. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2022, 20, 2779–2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Santos, R.M.; Reyes-Gutiérrez, P.E.; Torres-Ochoa, R.O.; Ramírez-Apan, M.T.; Martínez, R. 5,6-dihydropyrrolo[2,1-a]isoquinolines as alternative of new drugs with cytotoxic activity. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2017, 65, 973–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevskaya, A.A.; Matveeva, M.D.; Borisova, T.N.; Niso, M.; Colabufo, N.A.; Boccarelli, A.; Purgatorio, R.; de Candia, M.; Cellamare, S.; Voskressensky, L.G.; et al. A new class of 1-aryl-5,6-dihydropyrrolo[2,1-a]isoquinoline derivatives as reversers of P-glycoprotein-mediated multidrug resistance in tumor cells. ChemMedChem 2018, 13, 1588–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevskaya, A.A.; Purgatorio, R.; Borisova, T.N.; Varlamov, A.V.; Anikina, L.V.; Obydennik, A.Y.; Nevskaya, E.Y.; Niso, M.; Colabufo, N.A.; Carrieri, A.; et al. Nature-inspired 1-phenylpyrrolo[2,1-a]isoquinoline scaffold for novel antiproliferative agents circumventing P-glycoprotein-dependent multidrug resistance. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

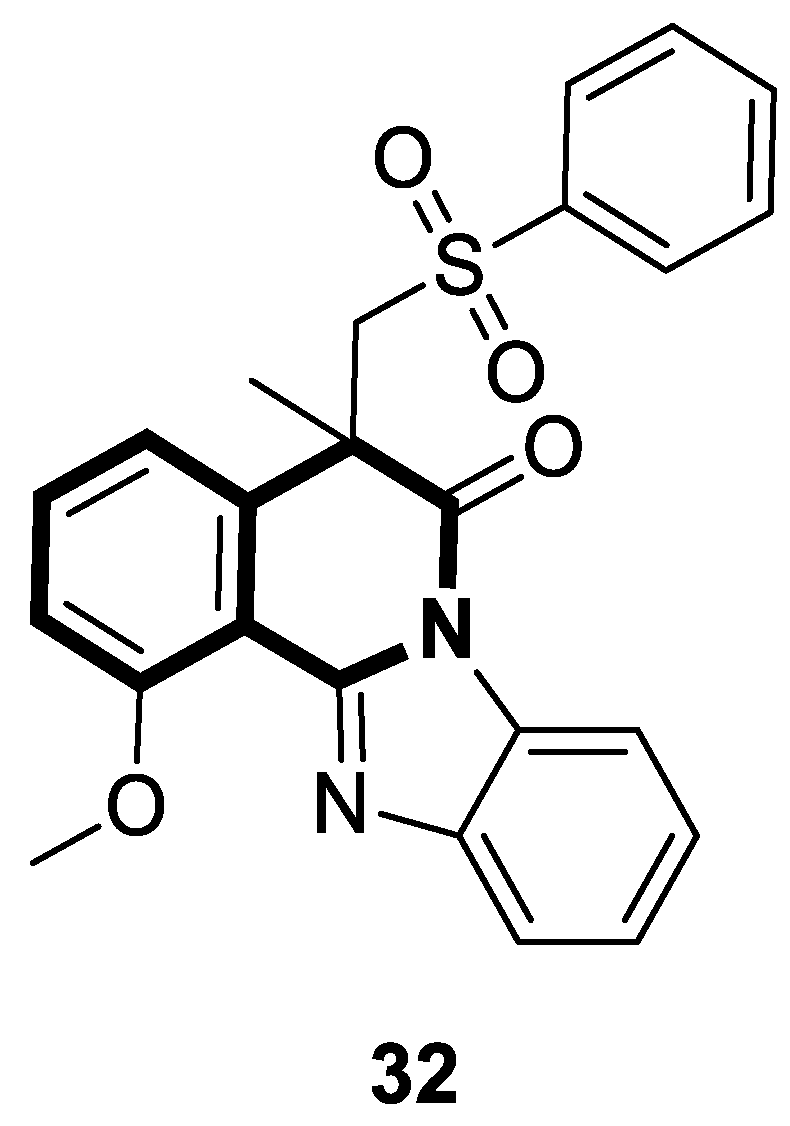

- Pan, Y.L.; Gong, X.M.; Hao, R.R.; Zeng, S.X.; Shen, Z.R.; Huang, W.H. The synthesis of anticancer sulfonated indolo[2,1-a]isoquinoline and benzimidazo[2,1-a]isoquinolin-6(5H)-ones derivatives via a free radical cascade pathway. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 9763–9772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

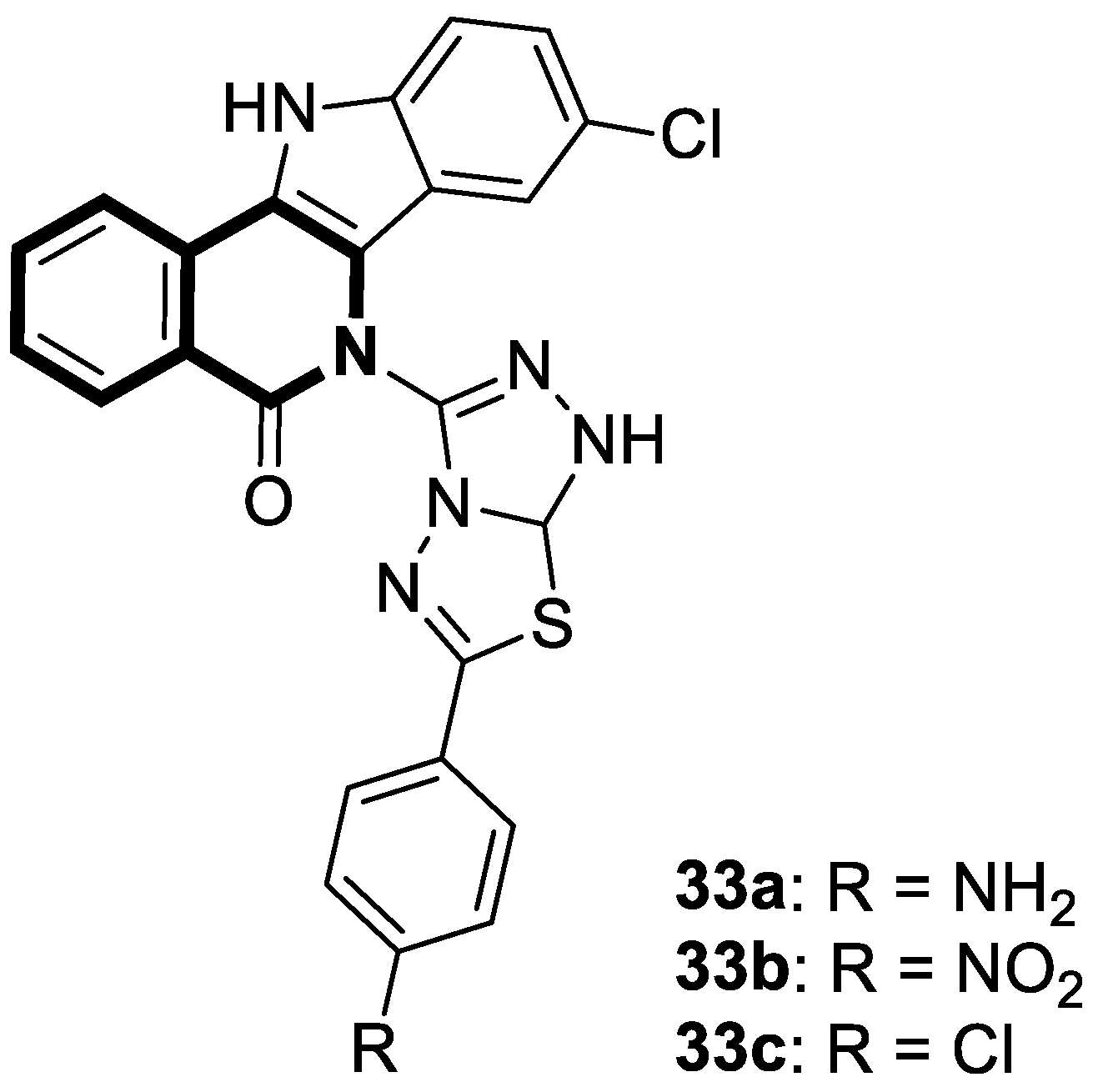

- Verma, V.A.; Saundane, A.R.; Shamrao, R.; Meti, R.S.; Shinde, V.M. Novel indolo[3,2-c]isoquinoline-5-one-6-yl[1,2,4]triazolo [3,4-b][1,3,4]thiadiazole analogues: Design, synthesis, anticancer activity, docking with SARS-CoV-2 omicron protease and MESP/TD-DFT approaches. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1264, 133153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

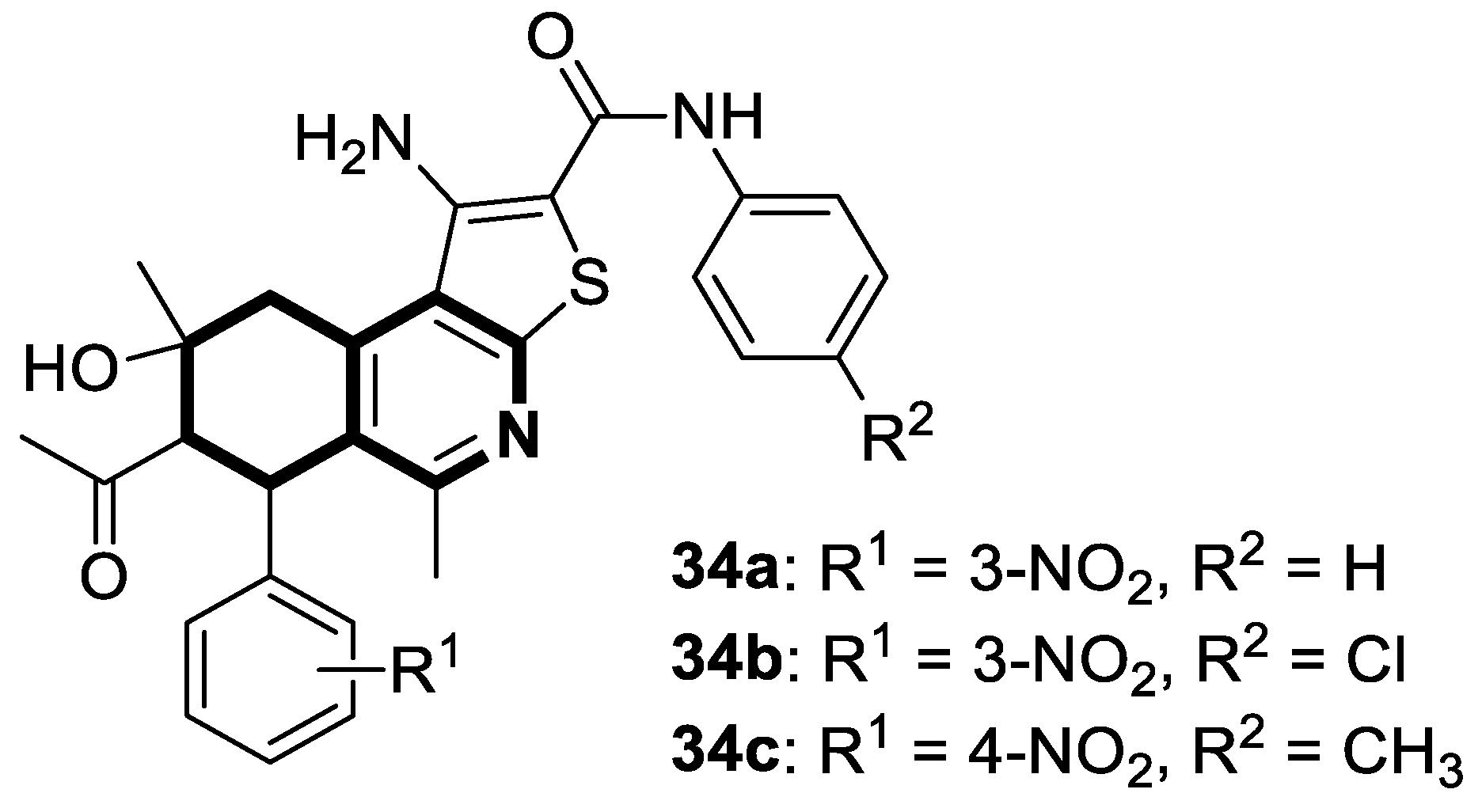

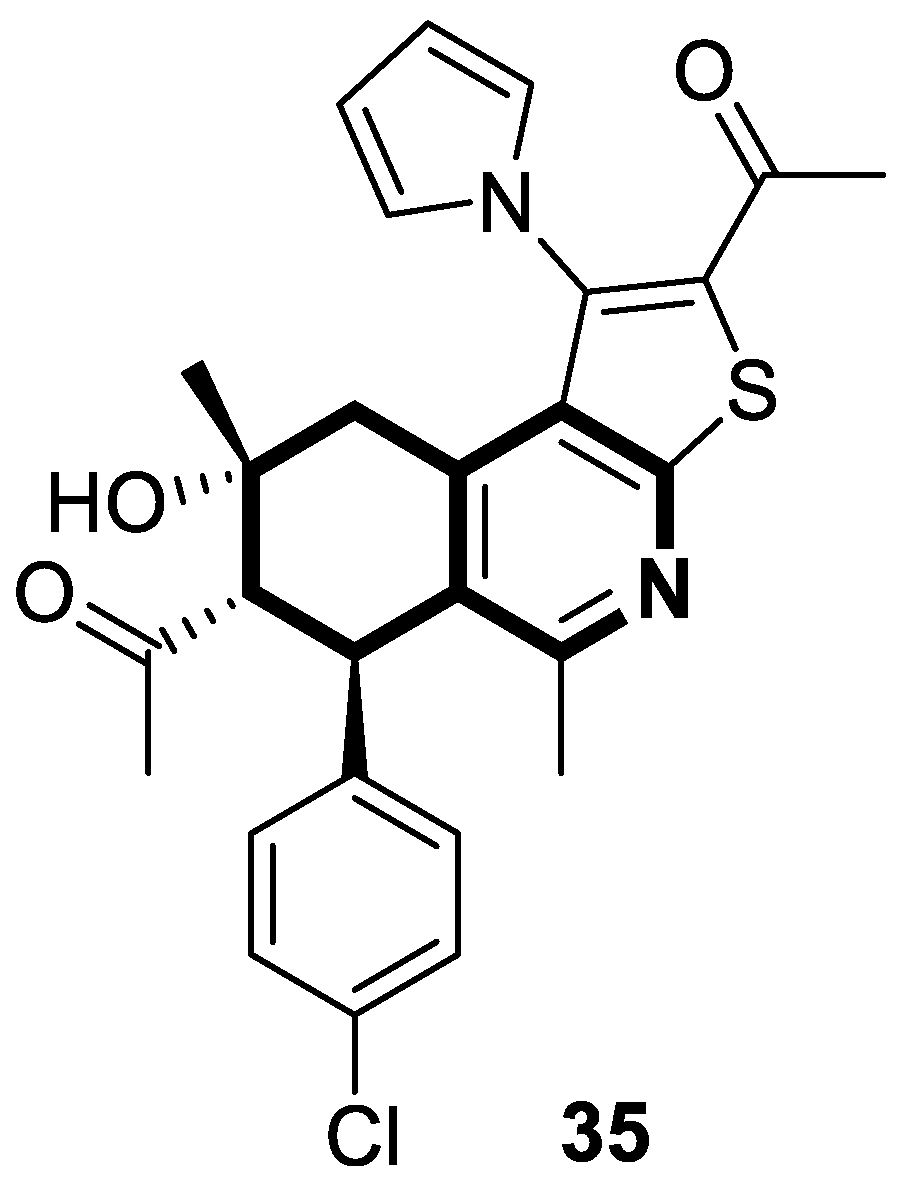

- Sayed, E.M.; Hassanien, R.; Farhan, N.; Aly, H.F.; Mahmoud, K.; Mohamed, S.K.; Mague, J.T.; Bakhite, E.A. Nitrophenyl-group-containing heterocycles. I. Synthesis, characterization, crystal structure, anticancer activity, and antioxidant properties of some new 5,6,7,8-tetrahydroisoquinolines bearing 3(4)-nitrophenyl group. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 8767–8776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marae, I.S.; Maklad, R.M.; Samir, S.; Bakhite, E.A.; Sharmoukh, W. Thieno [2,3-c]isoquinolines: A novel chemotype of antiproliferative agents inducing cellular apoptosis while targeting the G2/M phase and tubulin. Drug Dev. Res. 2023, 84, 747–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

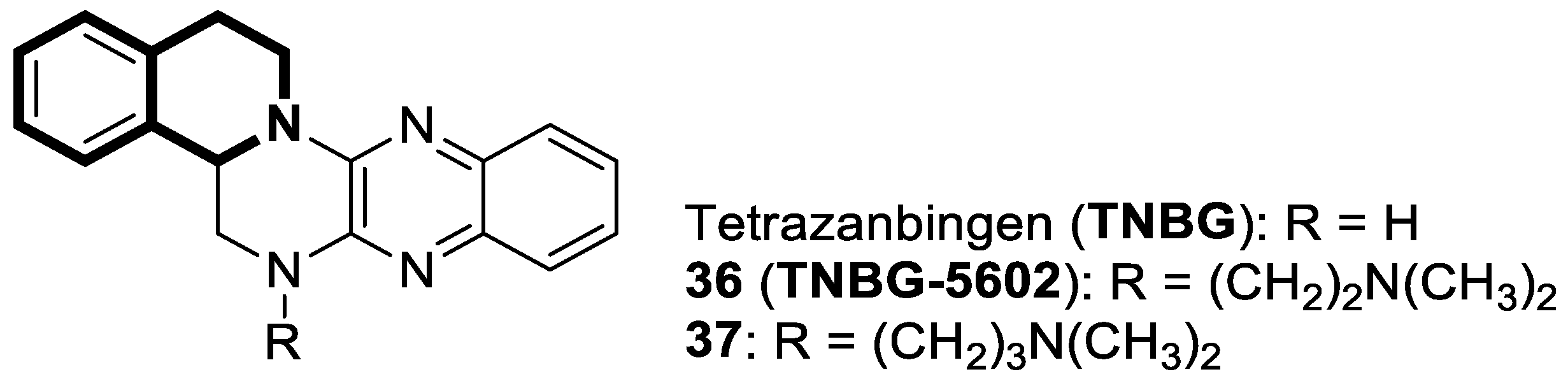

- Zheng, X.; Li, W.; Lan, Z.; Yang, X.; Li, L.; Yuan, Y.; Xia, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Yu, Y. Antitumour effects of tetrazanbigen against human hepatocellular carcinoma QGY-7701 through inducing lipid accumulation in vitro and in vivo. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2015, 67, 1593–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Wan, C.; Gan, Z.; Liu, R.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Gan, L.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; He, B.; et al. TNBG-5602, a novel derivative of quinoxaline, inhibits liver cancer growth via upregulating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ in vitro and in vivo. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2019, 71, 1684–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Gan, Y.J.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Synthesis and evaluation of new sterol derivatives as potential antitumor agents. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 26528–26537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.; Gan, Z.; Dan, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, P.; Chen, S.; Ye, Z.; Pan, T.; Wan, C.; Hu, X.; et al. Tetrazanbigen derivatives as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) partial agonists: Design, synthesis, structure-activity relationship, and anticancer activities. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 1018–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

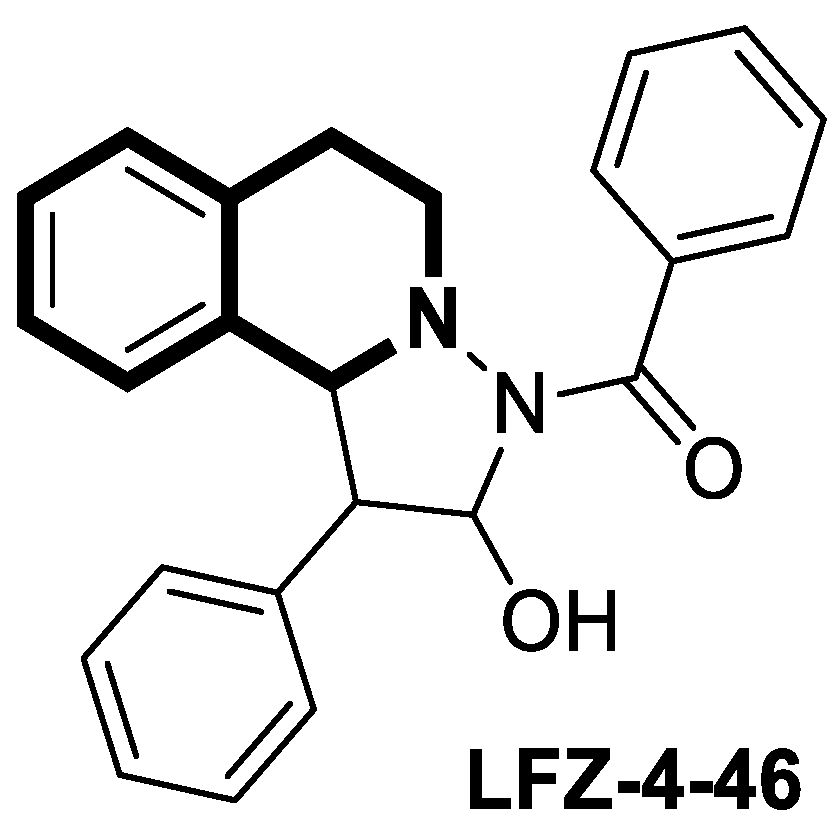

- Xu, L.; Huang, G.; Zhu, Z.; Tian, S.; Wei, Y.; Hong, H.; Lu, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhao, H. LFZ-4-46, a tetrahydroisoquinoline derivative, induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest via induction of DNA damage and activation of MAPKs pathway in cancer cells. Anti-Cancer Drugs 2021, 32, 842–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

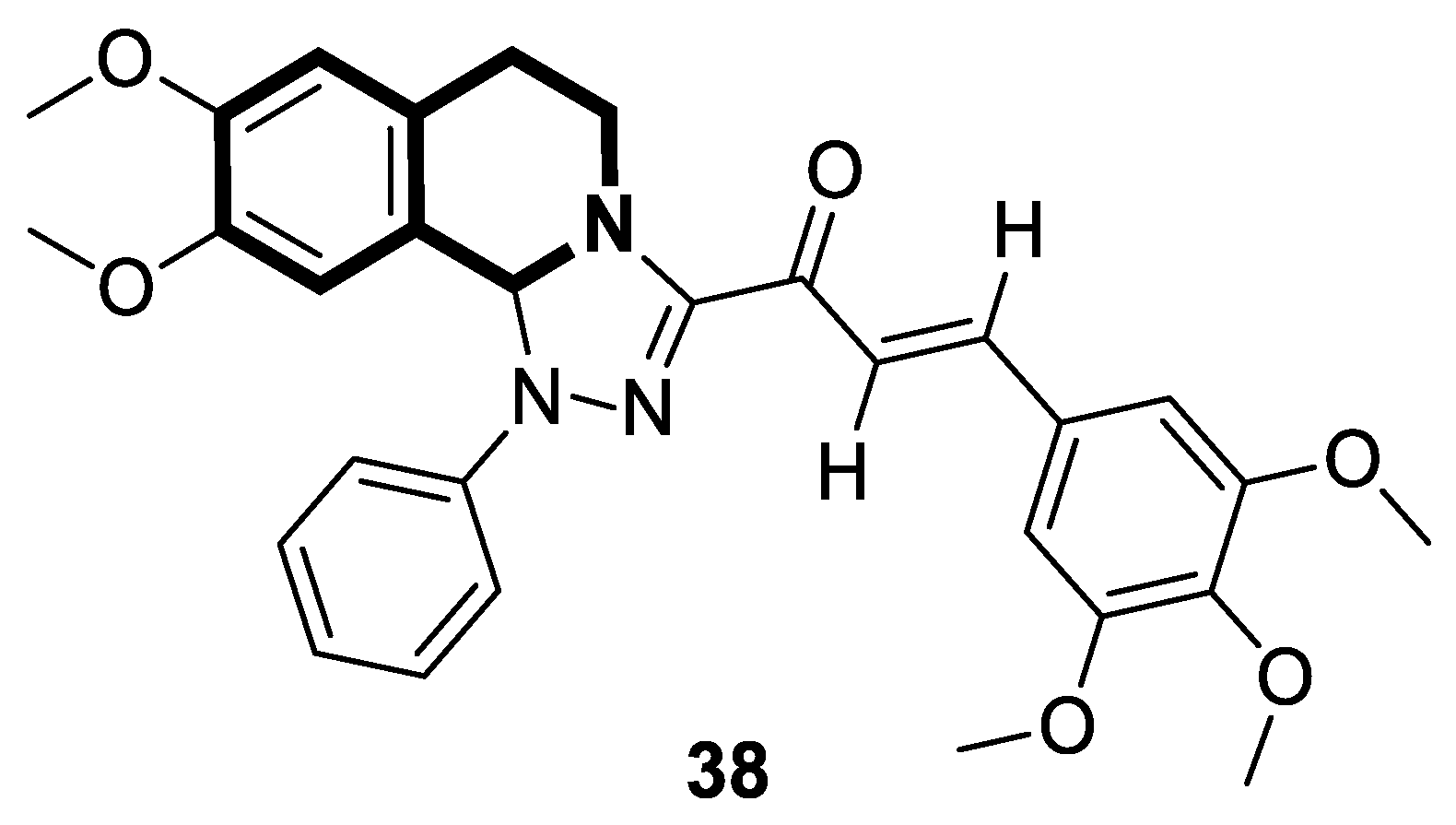

- Mazumder, R.; Ichudaule; Ghosh, A.; Deb, S.; Ghosh, R. Significance of chalcone scaffolds in medicinal chemistry. Top. Curr. Chem. 2024, 382, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandawate, P.; Ahmed, K.; Padhye, S.; Ahmad, A.; Biersack, B. Anticancer active heterocyclic chalcones: Recent developments. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2021, 21, 558–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, F.F.; de Sousa, N.F.; de Oliveira, B.H.M.; Duarte, G.D.; Ferreira, M.D.L.; Scotti, M.T.; Filho, J.M.B.; Rodrigues, L.C.; de Moura, R.O.; Mendonça-Junior, F.J.B.; et al. Anticancer activity of chalcones and its derivatives: Review and in silico studies. Molecules 2023, 28, 4009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toublet, F.X.; Laurent, A.; Pouget, C. A review of natural and synthetic chalcones as anticancer agents targeting topoisomerase enzymes. Molecules 2025, 30, 2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, J.M.T.; Silva, S.A.N.M.; Rocha, R.B.D.; Machado, F.D.S.; Marinho Filho, J.D.B.; Araújo, A.J. Uncovering the potential of chalcone-sulfonamide hybrids: A systematic review on their anticancer activity and mechanisms of action. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2024, 42, e70001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WalyEldeen, A.A.; El-Shorbagy, H.M.; Hassaneen, H.M.; Abdelhamid, I.A.; Sabet, S.; Ibrahim, S.A. [1,2,4] Triazolo [3,4-a]isoquinoline chalcone derivative exhibits anticancer activity via induction of oxidative stress, DNA damage, and apoptosis in Ehrlich solid carcinoma-bearing mice. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2022, 395, 1225–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

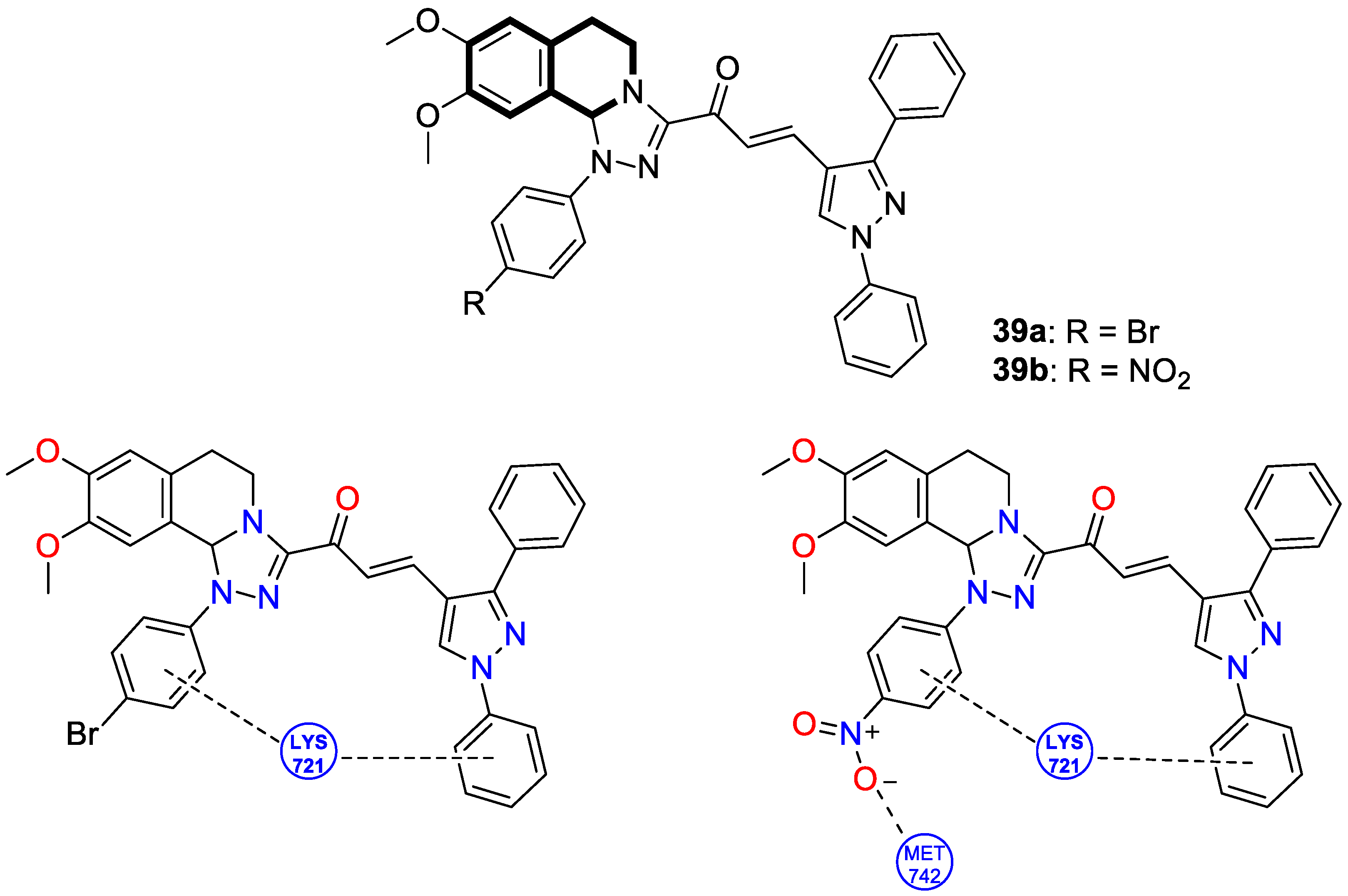

- Abdelaal, N.; Ragheb, M.A.; Hassaneen, H.M.; Elzayat, E.M.; Abdelhamid, I.A. Design, in silico studies and biological evaluation of novel chalcones tethered triazolo[3,4-a]isoquinoline as EGFR inhibitors targeting resistance in non-small cell lung cancer. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darwish, M.I.M.; Moustafa, A.M.; Youssef, A.M.; Mansour, M.; Yousef, A.I.; El Omri, A.; Shawki, H.H.; Mohamed, M.F.; Hassaneen, H.M.; Abdelhamid, I.A.; et al. Novel tetrahydro-[1,2,4]triazolo[3,4-a]isoquinoline chalcones suppress breast carcinoma through cell cycle arrests and apoptosis. Molecules 2023, 28, 3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantawy, M.A.; Sroor, F.M.; Mohamed, M.F.; El-Naggar, M.E.; Saleh, F.M.; Hassaneen, H.M.; Abdelhamid, I.A. Molecular docking study, cytotoxicity, cell cycle arrest and apoptotic induction of novel chalcones incorporating thiadiazolyl isoquinoline in cervical cancer. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2020, 20, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teleb, M.A.M.; Kamel, M.G.; Mikhail, M.S.; Hassaneen, H.M.; Erian, A.W.; Helmy, M.T. Synthesis, reactions, antitumor and antimicrobial activity of new 5,6-dihydropyrrolo[2,1-a]isoquinoline chalcones. BMC Chem. 2025, 19, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

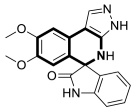

- de Castro Alves, C.E.; Bogza, S.L.; Bohdan, N.; Rozhenko, A.B.; de Freitas Gomes, A.; de Oliveira, R.C.; de Azevedo, R.G.; Maciel, L.R.S.; Dhyani, A.; Grafov, A.; et al. Pharmacological assessment of the antineoplastic and immunomodulatory properties of a new spiroindolone derivative (7′,8′-dimethoxy-1′,3′-dimethyl-1,2,3′,4′-tetrahydrospiro[indole-3,5′-pyrazolo [3,4-c]isoquinolin]-2-one) in chronic myeloid leukemia. Investig. New Drugs 2023, 41, 629–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

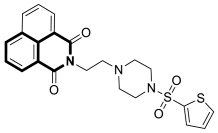

- Haque, A.; Alenezi, K.M.; Al-Otaibi, A.; Alsukaibi, A.K.D.; Rahman, A.; Hsieh, M.F.; Tseng, M.W.; Wong, W.Y. Synthesis, characterization, cytotoxicity, cellular imaging, molecular docking, and ADMET studies of piperazine-linked 1,8-naphthalimide-arylsulfonyl derivatives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, W.; Xie, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xia, L.; Guo, Y.; Qiao, D. An overview of naphthylimide as specific scaffold for new drug discovery. Molecules 2024, 29, 4529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, R.; Luxami, V.; Tandon, N.; Paul, K. Recent developments on 1,8-naphthalimide moiety as potential target for anticancer agents. Bioorganic Chem. 2022, 121, 105677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, B.; Estalayo-Adrián, S.; Umadevi, D.; la Cour Poulsen, B.; Blasco, S.; McManus, G.J.; Gunnlaugsson, T.; Shanmugaraju, S. Design, synthesis, and anticancer studies of a p-cymene-Ru(II)-curcumin organometallic conjugate based on a fluorescent 4-amino-1,8-naphthalimide Tröger’s base scaffold. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 11592–11599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rykowski, S.; Gurda-Woźna, D.; Orlicka-Płocka, M.; Fedoruk-Wyszomirska, A.; Giel-Pietraszuk, M.; Wyszko, E.; Kowalczyk, A.; Stączek, P.; Biniek-Antosiak, K.; Rypniewski, W.; et al. Design of DNA intercalators based on 4-carboranyl-1,8-naphthalimides: Investigation of their DNA-binding ability and anticancer activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nekvinda, J.; Różycka, D.; Rykowski, S.; Wyszko, E.; Fedoruk-Wyszomirska, A.; Gurda, D.; Orlicka-Płocka, M.; Giel-Pietraszuk, M.; Kiliszek, A.; Rypniewski, W.; et al. Synthesis of naphthalimide-carborane and metallacarborane conjugates: Anticancer activity, DNA binding ability. Bioorganic Chem. 2020, 94, 103432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rykowski, S.; Gurda-Woźna, D.; Orlicka-Płocka, M.; Fedoruk-Wyszomirska, A.; Giel-Pietraszuk, M.; Wyszko, E.; Kowalczyk, A.; Stączek, P.; Bak, A.; Kiliszek, A.; et al. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of novel 3-carboranyl-1,8-naphthalimide derivatives as potential anticancer agents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, S.; Luxami, V.; Paul, K. Synthesis of triphenylethylene-naphthalimide conjugates as topoisomerase-IIα inhibitor and HSA binder. ChemMedChem 2021, 16, 1822–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wang, L.; Shang, Z.; Yang, X.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; Zhu, M.; Meng, Q. A series of DNA targeted Cu(II) complexes containing 1,8-naphthalimide ligands: Synthesis, characterization and in vitro anticancer activity. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2024, 261, 112721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, U.; Kandemir, I.; Cömert, F.; Akkoç, S.; Coban, B. Synthesis of naphthalimide derivatives with potential anticancer activity, their comparative ds- and G-quadruplex-DNA binding studies and related biological activities. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 1563–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, M.; Xiong, X.Q.; Yang, H.; Wang, P.; Zhang, K.; Awadasseid, A.; Narva, S.; Wu, Y.L.; Zhang, W. Design, synthesis and bioactivity of novel naphthalimide-benzotriazole conjugates against A549 cells via targeting BCL2 G-quadruplex and inducing autophagy. Life Sci. 2022, 302, 120651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, F.; Cao, Y.; Zhu, C.; Li, Y.; Ma, X.; Wang, S.; Liu, H.; Xie, X.; Gao, L.; Wang, Y.; et al. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of naphthalimide-polyamine conjugate as a potential anti-colorectal cancer agent. Chem. Biodivers. 2025, 22, e202401873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.R.; Wang, B.J.; Jia, D.G.; Yang, X.B.; Huang, Y. Synthesis, electrochemistry, DNA binding and in vitro cytotoxic activity of tripodal ferrocenyl bis-naphthalimide derivatives. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2021, 219, 111425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canonico, B.; Cangiotti, M.; Montanari, M.; Papa, S.; Fusi, V.; Giorgi, L.; Ciacci, C.; Ottaviani, M.F.; Staneva, D.; Grabchev, I. Characterization of a fluorescent 1,8-naphthalimide-functionalized PAMAM dendrimer and its Cu(II) complexes as cytotoxic drugs: EPR and biological studies in myeloid tumor cells. Biol. Chem. 2021, 403, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Yue, K.; Li, L.; Niu, J.; Liu, H.; Ma, J.; Xie, S. A Pt(IV)-based mononitro-naphthalimide conjugate with minimized side-effects targeting DNA damage response via a dual-DNA-damage approach to overcome cisplatin resistance. Bioorganic Chem. 2020, 101, 104011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, F.; Meng, Q.; Zhang, S.; Jia, H.; Wang, C.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, Z. A novel fluorescence probe for the reversible detection of bisulfite and hydrogen peroxide pair in vitro and in vivo. Chem. Asian J. 2021, 16, 3419–3426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, N.; Wang, Y.; Lu, S.; Sheng, J.; Liu, X.; Wei, Y.; Shangguan, D. A naphthalimide-based fluorescent platform for endoplasmic reticulum targeted imaging. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 8565–8568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cai, Z.; Gu, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y. Naphthalimide-based functional glycopolymeric nanoparticles as fluorescent probes for selective imaging of tumor cells. Chemistry 2024, 30, e202304165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Pattanaik, P.P.K.M.N.; Moitra, P.; Dandela, R. Rational design and syntheses of naphthalimide-based fluorescent probes for targeted detection of diabetes biomarkers. Bioorganic Chem. 2025, 154, 108013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Pan, S.; Sivaram, S.; De, P. Naphthalimide-based fluorescent polymeric probe: A dual-phase sensor for formaldehyde detection. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2025, 26, 2469493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yan, D.X.; Rong, R.X.; Shi, B.Y.; Zhang, M.; Liu, J.; Xin, J.; Xu, T.; Ma, W.J.; Li, X.L.; et al. Nucleolus imaging based on naphthalimide derivatives. Bioorganic Chem. 2024, 142, 106969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jama-Kmiecik, A.; Mączyńska, B.; Frej-Mądrzak, M.; Choroszy-Król, I.; Dudek-Wicher, R.; Piątek, D.; Kujawa, K.; Sarowska, J. The changes in the antibiotic resistance of Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium in the clinical isolates of a multiprofile hospital over 6 years (2017–2022). J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanja, C.W.; Naganna, N.; Abutaleb, N.S.; Dayal, N.; Onyedibe, K.I.; Aryal, U.; Seleem, M.N.; Sintim, H.O. Isoquinoline antimicrobial agent: Activity against intracellular bacteria and effect on global bacterial proteome. Molecules 2022, 27, 5085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

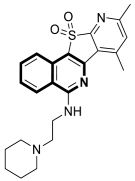

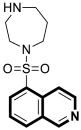

- Bakker, A.T.; Kotsogianni, I.; Avalos, M.; Punt, J.M.; Liu, B.; Piermarini, D.; Gagestein, B.; Slingerland, C.J.; Zhang, L.; Willemse, J.J.; et al. Discovery of isoquinoline sulfonamides as allosteric gyrase inhibitors with activity against fluoroquinolone-resistant bacteria. Nat. Chem. 2024, 16, 1462–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alipour Noghabi, S.; Ghamari Kargar, P.; Bagherzade, G.; Beyzaei, H. Comparative study of antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of berberine-derived Schiff bases, nitro-berberine and amino-berberine. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payne, M.; Bottomley, A.L.; Och, A.; Hiscocks, H.G.; Asmara, A.P.; Harry, E.J.; Ung, A.T. Synthesis and biological evaluation of tetrahydroisoquinoline-derived antibacterial compounds. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2022, 57, 116648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, V.A.; Saundane, A.R.; Meti, R.S.; Vennapu, D.R. Synthesis of novel indolo[3,2-c]isoquinoline derivatives bearing pyrimidine, piperazine rings and their biological evaluation and docking studies against COVID-19 virus main protease. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1229, 129829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatiya, M.; Merid, Y.; Mola, A.; Belayneh, F.; Ali, M.M. Prevalence of drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis and its associated factors among tuberculosis patients attending Dilla university referral hospital, Ethiopia. BMC Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, K.L.; Anibarro, L.; Chang, Z.Y.; Palasuberniam, P.; Mustapha, Z.A.; Sarmiento, M.E.; Acosta, A. Impacts of MDR/XDR-TB on the global tuberculosis epidemic: Challenges and opportunities. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2024, 7, 100295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mase, S.; Chorba, T.; Parks, S.; Belanger, A.; Dworkin, F.; Seaworth, B.; Warkentin, J.; Barry, P.; Shah, N. Bedaquiline for the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 1010–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbehiry, A.; Marzouk, E.; Edrees, H.M.; AlShaqi, R.; Ellethy, A.T.; Alzaben, F.; Anagreyyah, S.; Algarni, A.; Almuhaydili, K.; Alotaibi, I.; et al. Advancing the fight against tuberculosis: Integrating innovation and public health in diagnosis, treatment, vaccine development, and implementation science. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1596579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.X.; Zhao, X.; Wang, L.; Yang, Z.C. Quinoline derivatives as potential anti-tubercular agents: Synthesis, molecular docking and mechanism of action. Microb. Pathog. 2022, 165, 105507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

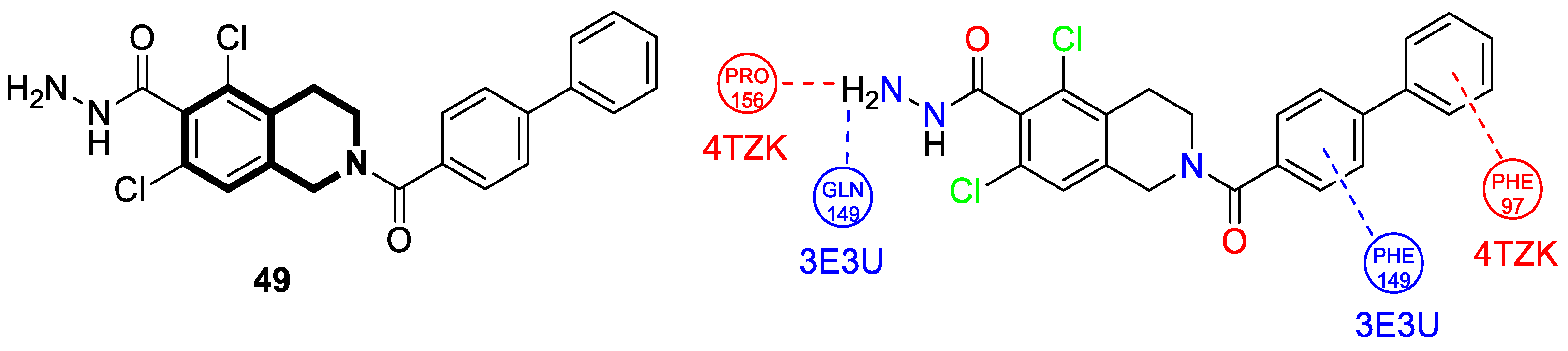

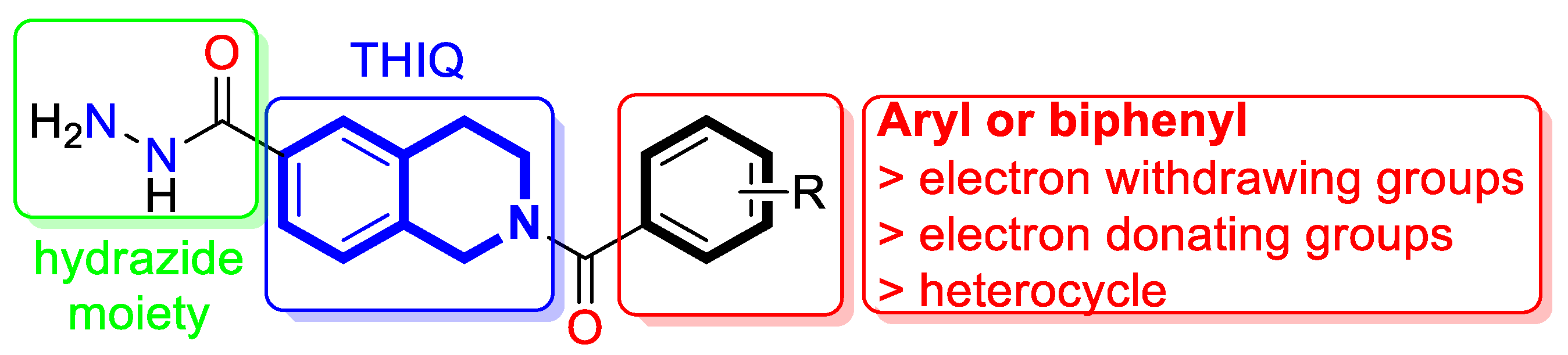

- Kumar, B.V.S.; Khetmalis, Y.M.; Nandikolla, A.; Kumar, B.K.; Van Calster, K.; Murugesan, S.; Cappoen, D.; Sekhar, K.V.G.C. Design, synthesis, and antimycobacterial evaluation of novel tetrahydroisoquinoline hydrazide analogs. Chem. Biodivers. 2023, 20, e202200939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habschied, K.; Krstanović, V.; Zdunić, Z.; Babić, J.; Mastanjević, K.; Šarić, G.K. Mycotoxins biocontrol methods for healthier crops and stored products. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latiffah, Z. An overview of Aspergillus species associated with plant diseases. Pathogens 2024, 13, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Shaarani, A.A.Q.A.; Pecoraro, L. A review of pathogenic airborne fungi and bacteria: Unveiling occurrence, sources, and profound human health implication. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1428415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Zhang, R.; Chen, Y.; Yu, P.; Lan, Y.; Xu, H.; Lei, S. Design, synthesis and mechanism study of novel natural-derived isoquinoline derivatives as antifungal agents. Mol. Divers. 2023, 27, 1011–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

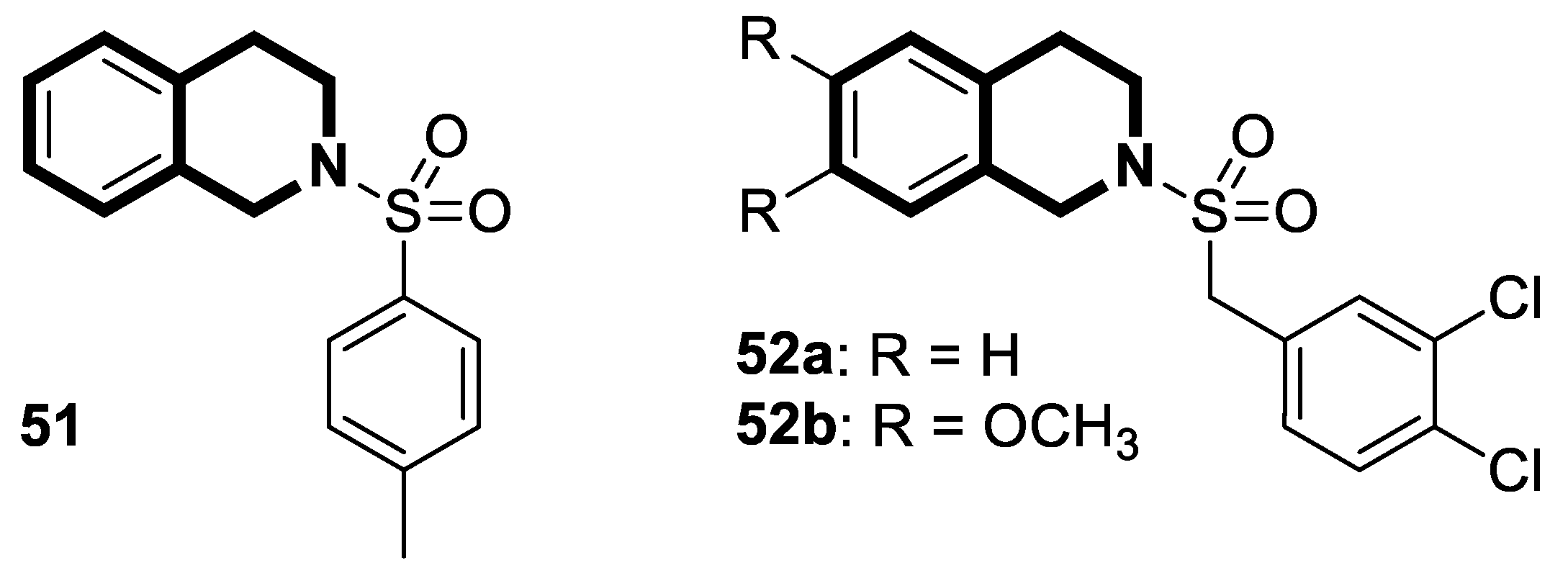

- Rinaldi Tosi, M.E.; Palermo, V.; Giannini, F.A.; Fernández Baldo, M.A.; Díaz, J.R.A.; Lima, B.; Feresin, G.E.; Romanelli, G.P.; Baldoni, H.A. N-sulfonyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline derivatives: Synthesis, antimicrobial evaluations, and theoretical insights. Chem. Biodivers. 2023, 20, e202300905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

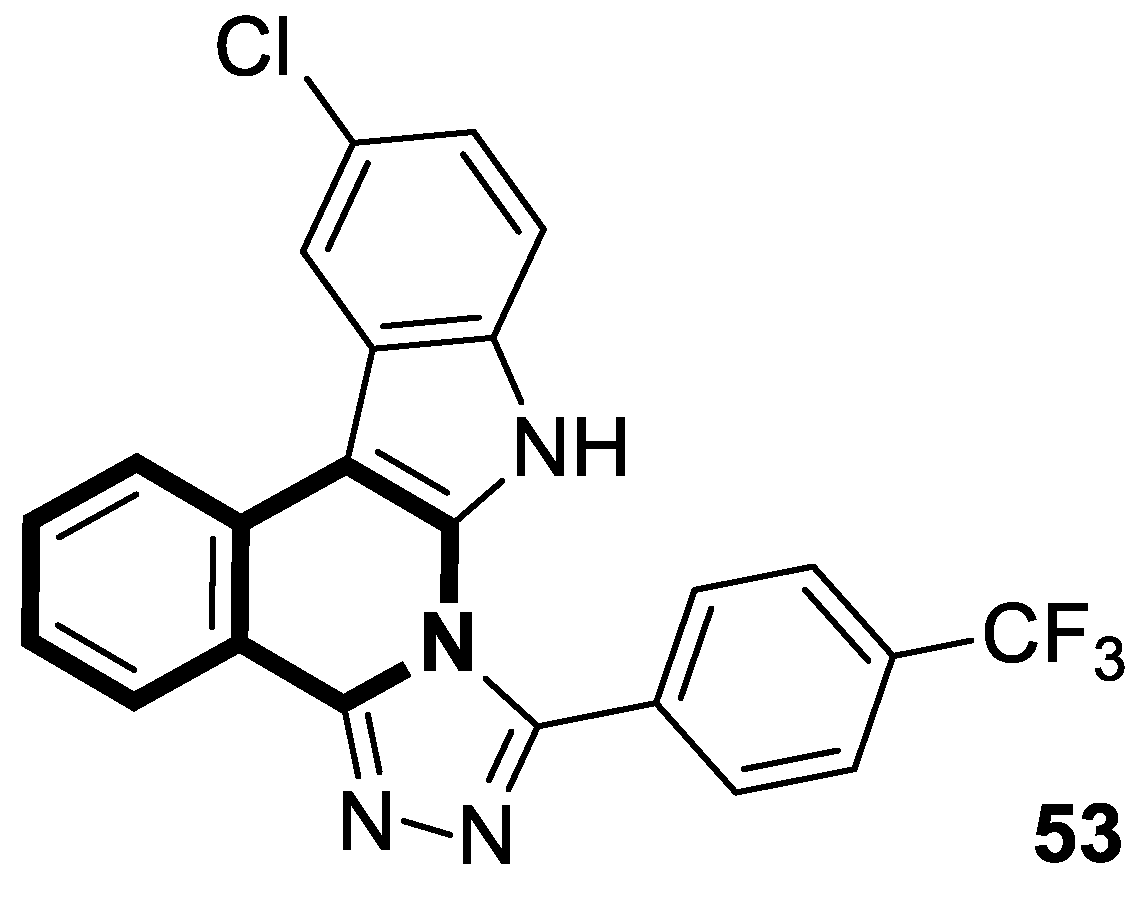

- Basavarajaiah, S.M.; Badiger, J.; Yernale, N.G.; Gupta, N.; Karunakar, P.; Sridhar, B.T.; Javeed, M.; Kiran, K.S.; Rakesh, B. Exploration of indolo [3,2c]isoquinoline derived triazoles as potential antimicrobial and DNA cleavage agents: Synthesis, DFT calculations, and molecular modeling studies. Bioorganic Chem. 2023, 137, 106598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingala, S.; Ghany, M.G. Hepatitis B: Screening, awareness, and the need to treat. Fed. Pract. 2016, 33, 19S–23S. [Google Scholar]

- Trickey, A.; Artenie, A.; Feld, J.J.; Vickerman, P. Estimating the annual number of hepatitis C virus infections through vertical transmission at country, regional, and global levels: A data synthesis study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, 10, 904–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, S.A.A.; Noor, T.; Mylavarapu, M.; Sahotra, M.; Bashir, H.A.; Bhat, R.R.; Jindal, U.; Amin, U.V.A.; Siddiqui, H.F. Double trouble co-infections: Understanding the correlation between COVID-19 and HIV viruses. Cureus 2023, 15, e38678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feehan, J.; Apostolopoulos, V. Is COVID-19 the worst pandemic? Maturitas 2021, 149, 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Chen, J.; Cao, J.X.; Zhang, S.S.; Gu, S.X.; Chen, F.E. Quinolines and isoquinolines as HIV-1 inhibitors: Chemical structures, action targets, and biological activities. Bioorganic Chem. 2023, 136, 106549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

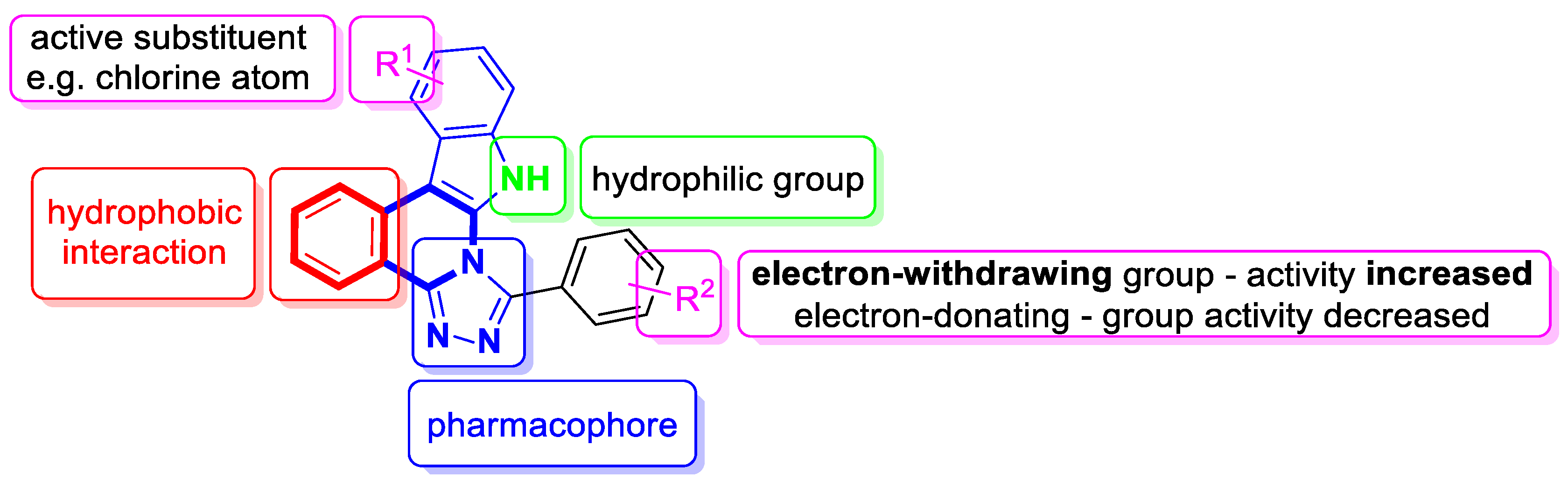

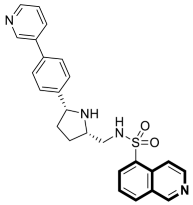

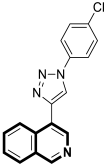

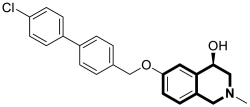

- Shad, M.S.; Claes, S.; Goffin, E.; Van Loy, T.; Schols, D.; De Jonghe, S.; Dehaen, W. Synthesis and anti-HIV activity of a novel series of isoquinoline-based CXCR4 antagonists. Molecules 2021, 26, 6297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, J.; Chen, J. Interferon and hepatitis B: Current and future perspectives. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 733364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonneveld, M.J.; Janssen, H.L. Chronic hepatitis B: Peginterferon or nucleos(t)ide analogues? Liver Int. 2011, 31, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

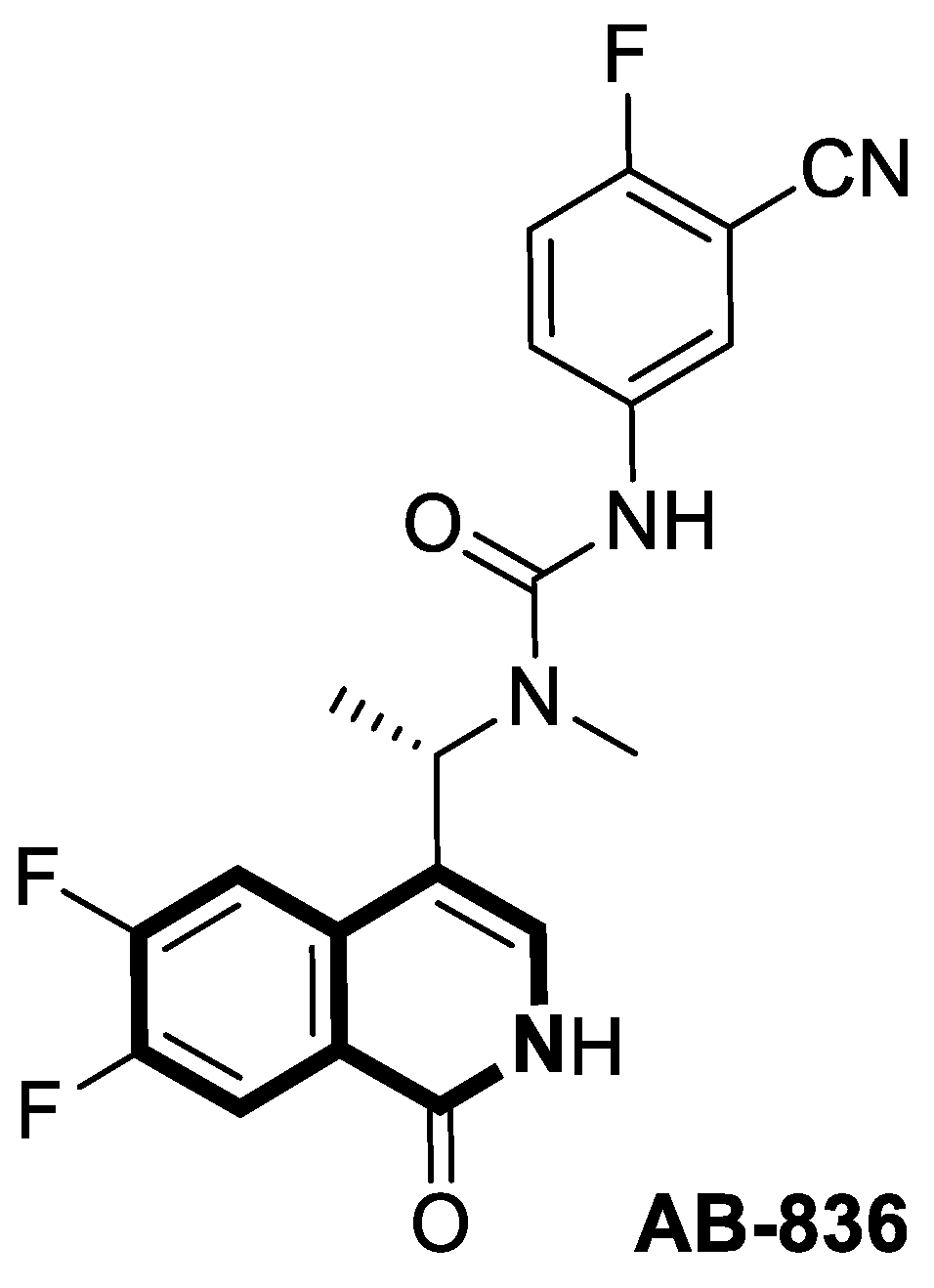

- Cole, A.G.; Kultgen, S.G.; Mani, N.; Fan, K.Y.; Ardzinski, A.; Stever, K.; Dorsey, B.D.; Mesaros, E.F.; Thi, E.P.; Graves, I.; et al. Rational design, synthesis, and structure–activity relationship of a novel isoquinolinone-based series of HBV capsid assembly modulators leading to the identification of clinical candidate AB-836. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 16773–16795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangeel, L.; Chiu, W.; De Jonghe, S.; Maes, P.; Slechten, B.; Raymenants, J.; André, E.; Leyssen, P.; Neyts, J.; Jochmans, D. Remdesivir, Molnupiravir and Nirmatrelvir remain active against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron and other variants of concern. Antivir. Res. 2022, 198, 105252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, V.C.; Moreira, I.B.G.; Dias, S.S.G. SARS-CoV-2 infection and antiviral strategies: Advances and limitations. Viruses 2025, 17, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Pang, Z.; Li, M.; Lou, F.; An, X.; Zhu, S.; Song, L.; Tong, Y.; Fan, H.; Fan, J. Molnupiravir and its antiviral activity against COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 855496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najjar-Debbiny, R.; Gronich, N.; Weber, G.; Khoury, J.; Amar, M.; Stein, N.; Goldstein, L.H.; Saliba, W. Effectiveness of Paxlovid in reducing severe coronavirus disease 2019 and mortality in high-risk patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 76, e342–e349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

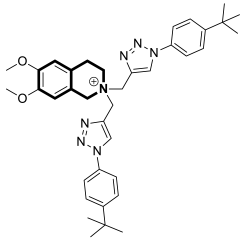

- Wang, X.; Burdzhiev, N.T.; Hu, H.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Lozanova, V.V.; Kandinska, M.I.; Wang, M. Novel tetrahydroisoquinoline-based heterocyclic compounds efficiently inhibit SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro. Viruses 2023, 15, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

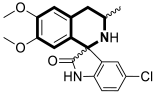

- Kandinska, M.I.; Burdzhiev, N.T.; Cheshmedzhieva, D.V.; Ilieva, S.V.; Grozdanov, P.P.; Vilhelmova-Ilieva, N.; Nikolova, N.; Lozanova, V.V.; Nikolova, I. Synthesis of novel 1-oxo-2,3,4-trisubstituted tetrahydroisoquinoline derivatives, bearing other heterocyclic moieties and comparative preliminary study of anti-coronavirus activity of selected compounds. Molecules 2023, 28, 1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

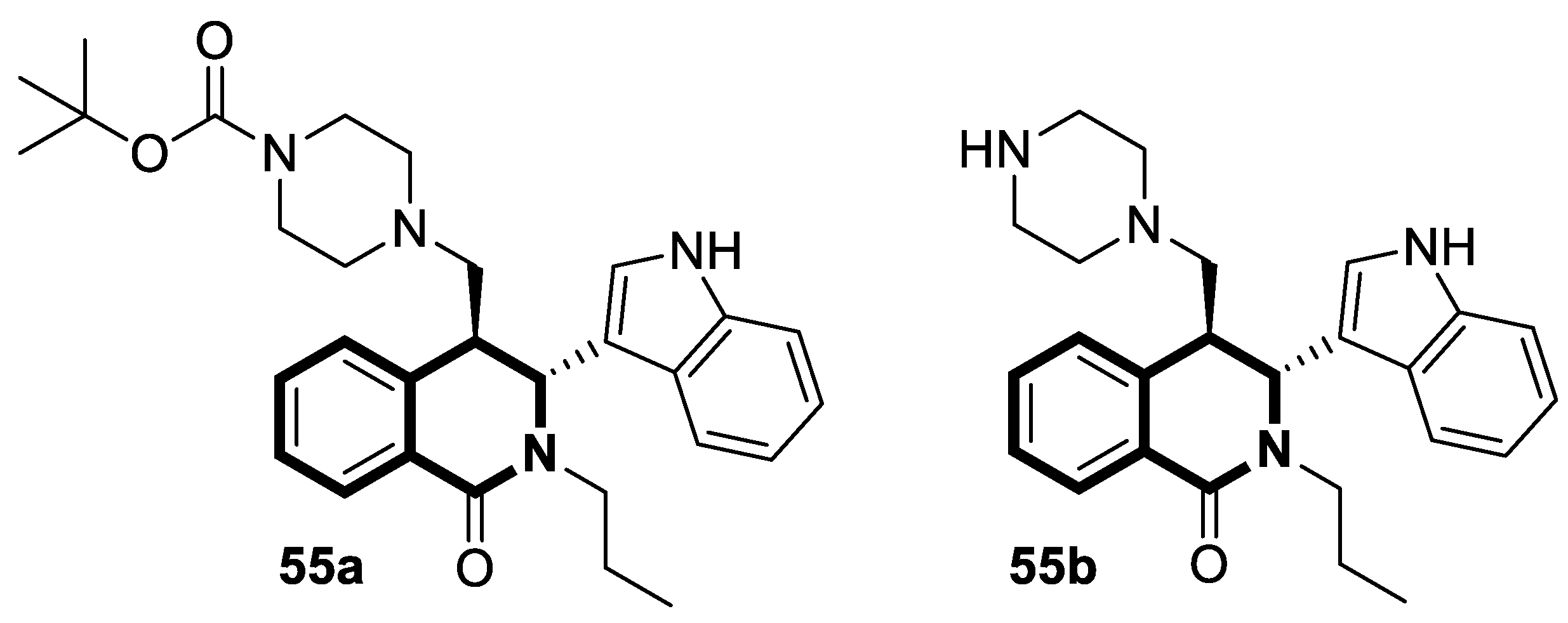

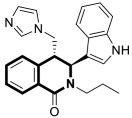

- Burdzhiev, N.T.; Baramov, T.I.; Stanoeva, E.R.; Yanev, S.G.; Stoyanova, T.D.; Dimitrova, D.H.; Kostadinova, K.A. Synthesis of novel trans-4-(phthalimidomethyl)- and 4-(imidazol-1-ylmethyl)-3-indolyl-tetrahydroisoquinolinones as possible aromatase inhibitors. Chem. Pap. 2019, 73, 1263–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, Y.; Peng, B.; Ni, S.; Wang, S.; Zhu, Q.; Li, H.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Pan, P.; et al. Design and synthesis of PAN endonuclease inhibitors through spirocyclization strategy against influenza A virus. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 68, 13393–13407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

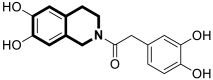

- Liao, Y.; Ye, Y.; Li, S.; Zhuang, Y.; Chen, L.; Chen, J.; Cui, Z.; Huo, L.; Liu, S.; Song, G. Synthesis and SARs of dopamine derivatives as potential inhibitors of influenza virus PAN endonuclease. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 189, 112048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

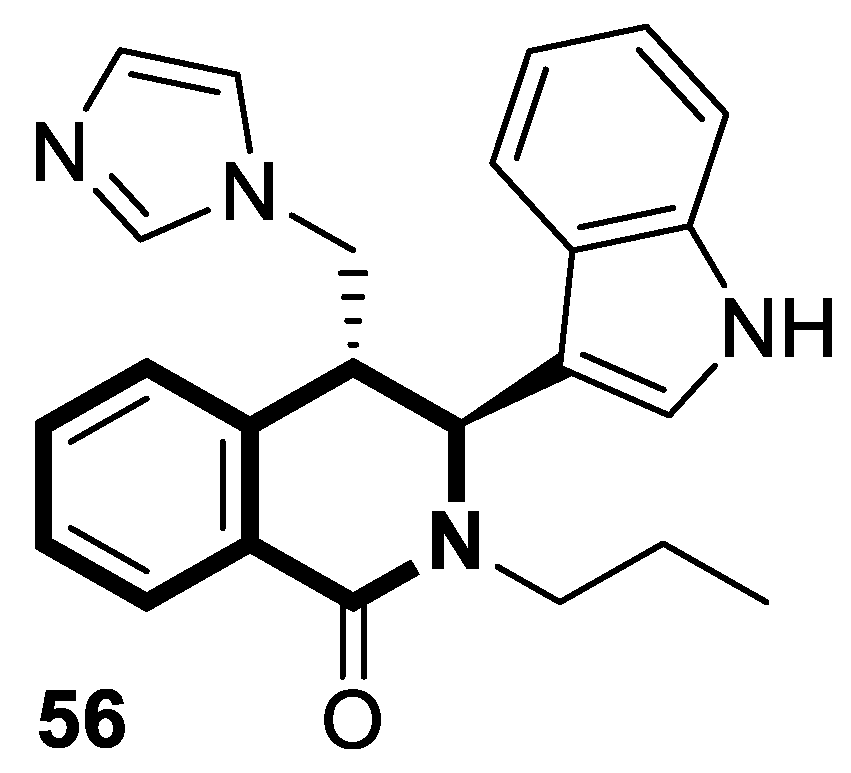

- Liu, Z.; Gu, S.; Zhu, X.; Liu, M.; Cao, Z.; Qiu, P.; Li, S.; Liu, S.; Song, G. Discovery and optimization of new 6,7-dihydroxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline derivatives as potent influenza virus PAN inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 227, 113929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Shrivastava, N.; Akhtar, M.; Ahmad, A.; Husain, A. Current updates on the epidemiology, pathogenesis and development of small molecule therapeutics for the treatment of Ebola virus infections. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2024, 17, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

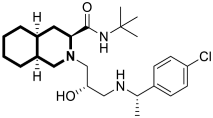

- Han, S.; Li, H.; Chen, W.; Yang, L.; Tong, X.; Zuo, J.; Hu, Y. Discovery of potent Ebola entry inhibitors with (3S,4aS,8aS)-2-(3-amino-2-hydroxypropyl) decahydroisoquinoline-3-carboxamide scaffold. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 240, 114608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Xiao, F.; Han, S.; Hu, Y.; Zuo, J.; Tong, X.; Chen, W. Discovery of novel Ebola entry inhibitors with 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline-3-carboxamide based on (3S,4aS,8aS)-2-(3-amino-2-hydroxypropyl)decahydroisoquinoline-3-carboxamide scaffold. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2025, 123, 130230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahalan, F.A.; Churcher, T.S.; Windbichler, N.; Lawniczak, M.K.N. The male mosquito contribution towards malaria transmission: Mating influences the Anopheles female midgut transcriptome and increases female susceptibility to human malaria parasites. PLoS Pathog. 2019, 15, e1008063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savi, M.K. An overview of malaria transmission mechanisms, control, and modeling. Med. Sci. 2022, 11, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poespoprodjo, J.R.; Douglas, N.M.; Ansong, D.; Kho, S.; Anstey, N.M. Malaria. Lancet 2023, 402, 2328–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

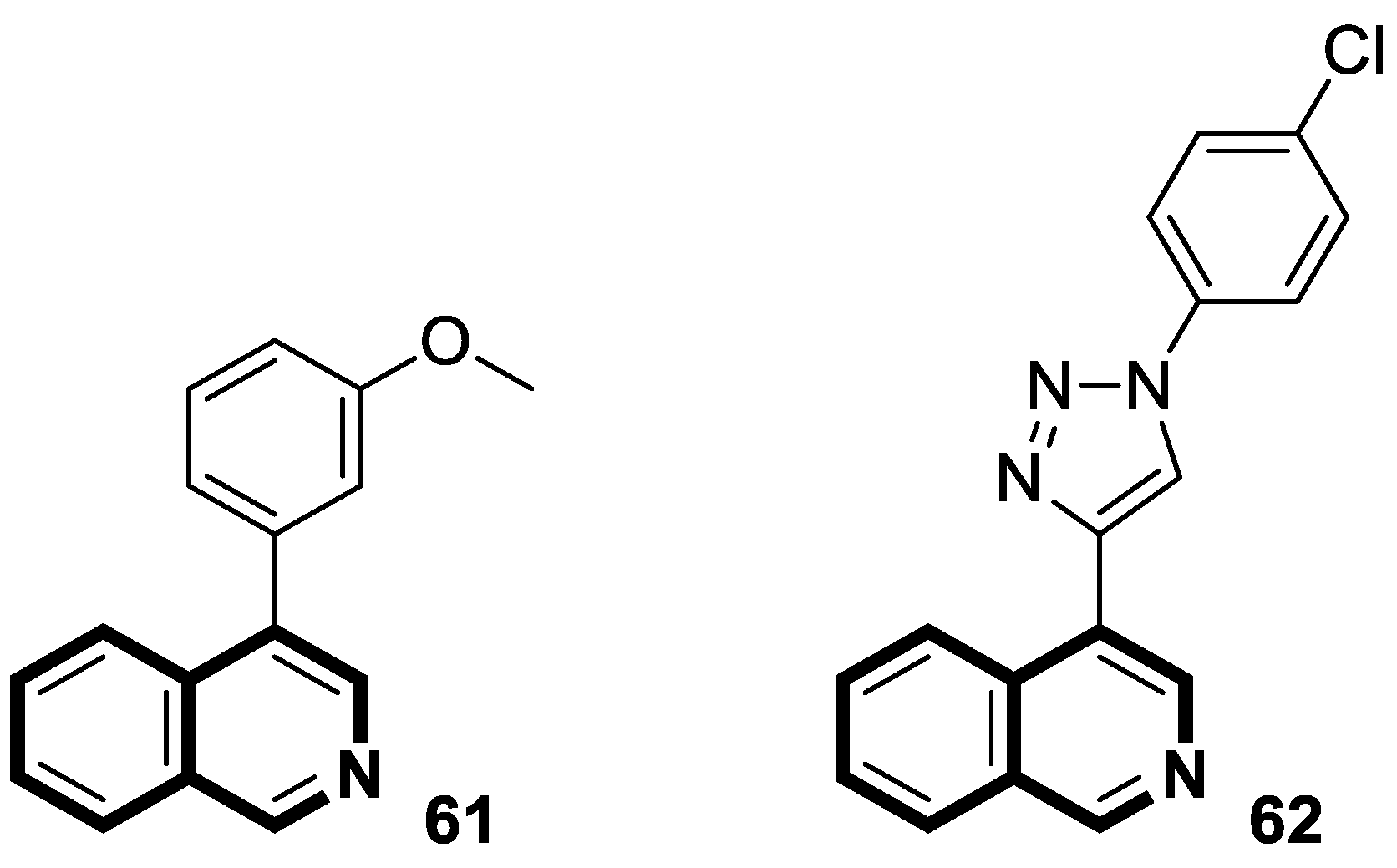

- Theeramunkong, S.; Thiengsusuk, A.; Vajragupta, O.; Muhamad, P. Synthesis, characterization and antimalarial activity of isoquinoline derivatives. Med. Chem. Res. 2021, 30, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillon, J.; Cohen, A.; Boudot, C.; Valle, A.; Milano, V.; Das, R.N.; Guédin, A.; Moreau, S.; Ronga, L.; Savrimoutou, S.; et al. Design, synthesis, and antiprotozoal evaluation of new 2,4-bis[(substituted-aminomethyl)phenyl]quinoline, 1,3-bis[(substituted-aminomethyl)phenyl]isoquinoline and 2,4-bis[(substituted-aminomethyl)phenyl]quinazoline derivatives. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2020, 35, 432–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rottmann, M.; McNamara, C.; Yeung, B.K.; Lee, M.C.; Zou, B.; Russell, B.; Seitz, P.; Plouffe, D.M.; Dharia, N.V.; Tan, J.; et al. Spiroindolones, a potent compound class for the treatment of malaria. Science 2010, 329, 1175–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efange, N.M.; Lobe, M.M.M.; Keumoe, R.; Ayong, L.; Efange, S.M.N. Spirofused tetrahydroisoquinoline-oxindole hybrids as a novel class of fast acting antimalarial agents with multiple modes of action. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobe, M.M.M.; Efange, S.M.N. 3′,4′-Dihydro-2′H-spiro[indoline-3,1′-isoquinolin]-2-ones as potential anti-cancer agents: Synthesis and preliminary screening. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 191316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efange, N.M.; Lobe, M.M.M.; Yamthe, L.R.T.; Pekam, J.N.M.; Tarkang, P.A.; Ayong, L.; Efange, S.M.N. Spirofused tetrahydroisoquinoline-oxindole hybrids (Spiroquindolones) as potential multitarget antimalarial agents: Preliminary hit optimization and efficacy evaluation in mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2022, 66, e0060722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papagni, R.; Novara, R.; Minardi, M.L.; Frallonardo, L.; Panico, G.G.; Pallara, E.; Cotugno, S.; Ascoli Bartoli, T.; Guido, G.; DeVita, E.; et al. Human African Trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness): Currentknowledge and future challenges. Front. Trop. Dis. 2023, 4, 1087003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendt, E.M.; Tobolowsky, F.A.; Priotto, G.; Franco, J.R.; Chancey, R. Notes from the field: Rhodesiense Human African Trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness) in a traveler returning from Zimbabwe—United States, August 2024. MMWR–Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2025, 74, 158–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, D.R.; Gallagher, A.; Duncan, C.L.; Pengon, J.; Rattanajak, R.; Chaplin, J.; Gunosewoyo, H.; Kamchonwongpaisan, S.; Payne, A.; Mocerino, M. Synthesis and evaluation of tetrahydroisoquinoline derivatives against Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 226, 113861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, S.; Schwartz, R.A.; Patil, A.; Grabbe, S.; Goldust, M. Treatment options for leishmaniasis. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2022, 47, 516–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, S.; Madhukar, P.; Kumar, R. Anti-leishmanial therapies: Overcoming current challenges with emerging therapies. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2025, 23, 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorlo, T.P.C.; Chu, W.Y. Skin pharmacokinetics of miltefosine in the treatment of post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis in South Asia—Authors’ response. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2025, 80, 1162–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundar, S.; Singh, V.K.; Agrawal, N.; Singh, O.P.; Kumar, R. Investigational new drugs for the treatment of leishmaniasis. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2024, 33, 1029–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majoor, A.; Michel, G.; Marty, P.; Boyer, L.; Pomares, C. Leishmaniases: Strategies in treatment development. Parasite 2025, 32, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbolla, I.; Sotomayor, N.; Lete, E. Carbopalladation/Suzuki coupling cascade for the generation of quaternary centers: Access to pyrrolo[1,2-b]isoquinolines. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 10183–10196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbolla, I.; Hernández-Suárez, L.; Quevedo-Tumailli, V.; Nocedo-Mena, D.; Arrasate, S.; Dea-Ayuela, M.A.; González-Díaz, H.; Sotomayor, N.; Lete, E. Palladium-mediated synthesis and biological evaluation of C-10b substituted dihydropyrrolo[1,2-b]isoquinolines as antileishmanial agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 220, 113458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waechtler, A.; Cezanne, B.; Maillard, D.; Sun, R.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Harder, A. Praziquantel—50 years of research. ChemMedChem 2023, 18, e202300154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, N.; Gouveia, M.J.; Rinaldi, G.; Brindley, P.J.; Gärtner, F.; Correia da Costa, J.M. Praziquantel for schistosomiasis: Single-drug metabolism revisited, mode of action, and resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e02582-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

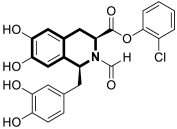

- Kasago, F.M.; Häberli, C.; Keiser, J.; Masamba, W. Design, synthesis and evaluation of praziquantel analogues and new molecular hybrids as potential antimalarial and anti-schistosomal agents. Molecules 2023, 28, 5184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plazas, E.; Hagenow, S.; Avila, M.M.; Stark, H.; Cuca, L.E. Isoquinoline alkaloids from the roots of Zanthoxylum rigidum as multi-target inhibitors of cholinesterase, monoamine oxidase A and Aβ1-42 aggregation. Bioorganic Chem. 2020, 98, 103722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cahlíková, L.; Vrabec, R.; Pidaný, F.; Peřinová, R.; Maafi, N.; Mamun, A.A.; Ritomská, A.; Wijaya, V.; Blunden, G. Recent progress on biological activity of amaryllidaceae and further isoquinoline alkaloids in connection with Alzheimer’s disease. Molecules 2021, 26, 5240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Chen, X.; Zhou, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Ren, X.; Zhu, F.; Guo, Y.; Huang, X.; Liu, J.; et al. The isoquinoline alkaloid dauricine targets multiple molecular pathways to ameliorate Alzheimer-like pathological changes in vitro. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 2025914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plazas, E.; Avila, M.M.C.; Muñoz, D.R.; Cuca, S.L.E. Natural isoquinoline alkaloids: Pharmacological features and multi-target potential for complex diseases. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 177, 106126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, Y.; Dong, S.; Yu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Xiang, B.; Li, Q. Research progress on neuroprotective effects of isoquinoline alkaloids. Molecules 2023, 28, 4797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

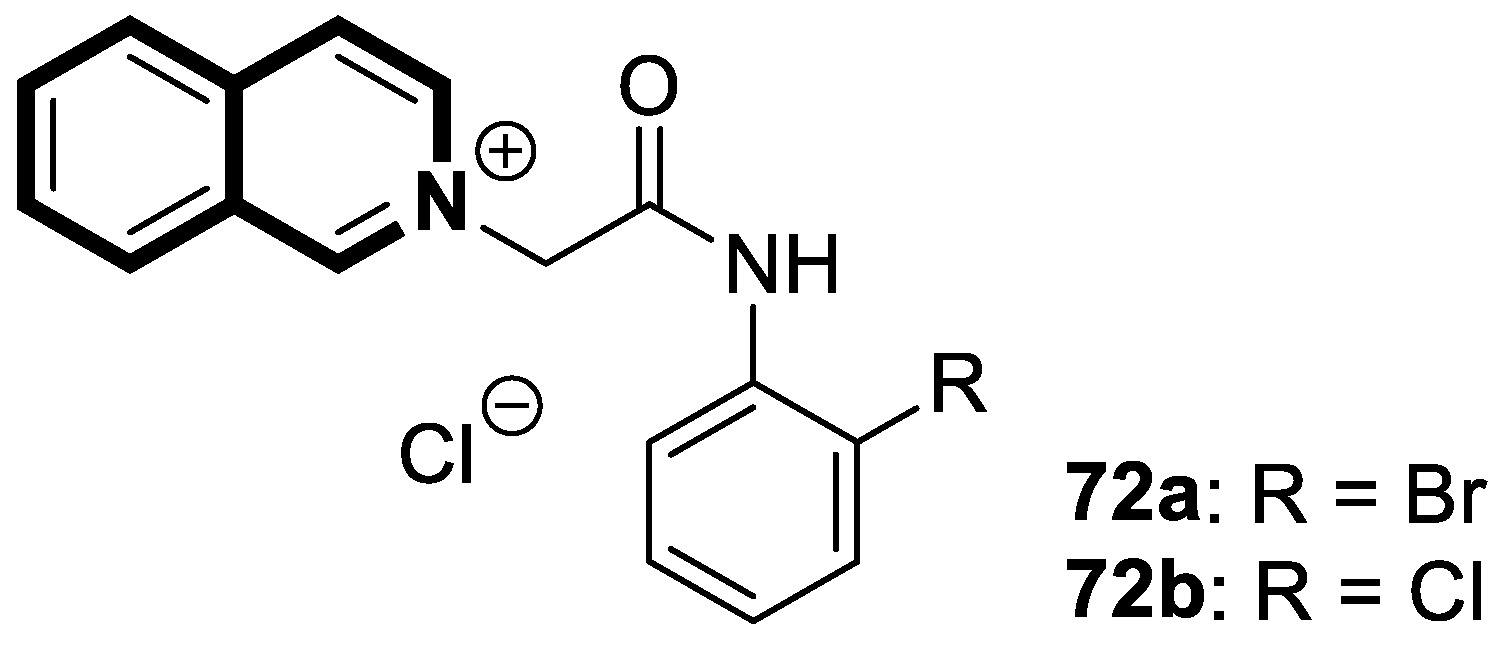

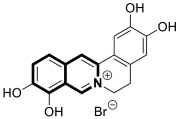

- Chakravarty, H.; Ju, Y.; Chen, W.H.; Tam, K.Y. Dual targeting of cholinesterase and amyloid beta with pyridinium/isoquinolium derivatives. Drug Dev. Res. 2020, 81, 242–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, R.; He, J.Q.; Chen, W.H.; Tam, K.Y. Evaluations of the neuroprotective effects of a dual-target isoquinoline inhibitor in the triple transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci. Lett. 2023, 802, 137166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.; Chakravarty, H.; Tam, K.Y. An isoquinolinium dual inhibitor of cholinesterases and amyloid β aggregation mitigates neuropathological changes in a triple-transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2020, 11, 3346–3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

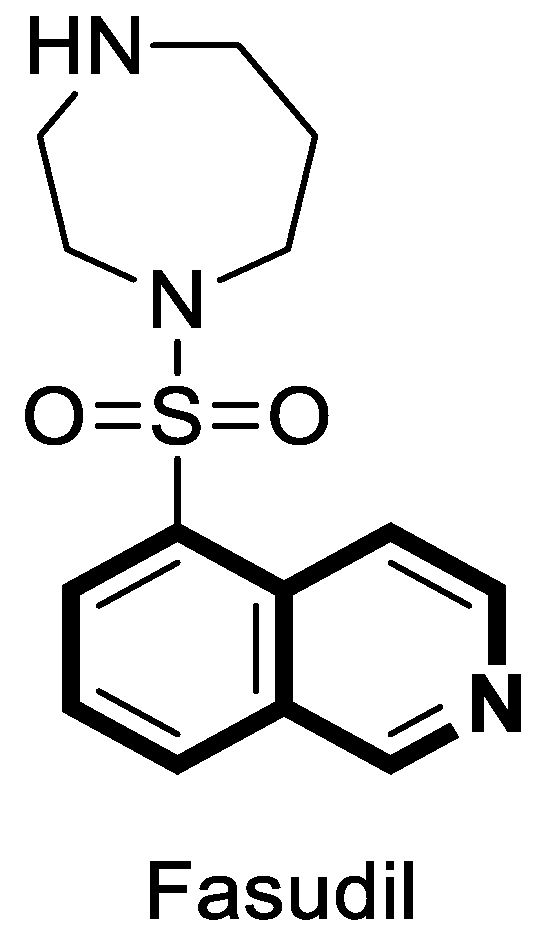

- Roskoski, R., Jr. Small molecule protein kinase inhibitors approved by regulatory agencies outside of the United States. Pharmacol. Res. 2023, 194, 106847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, A.W.; Peine, J.; Höfler, J.; Zurek, G.; Hemker, C.; Lingor, P. SAFE-ROCK: A phase I trial of an oral application of the ROCK inhibitor fasudil to assess bioavailability, safety, and tolerability in healthy participants. CNS Drugs 2024, 38, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kuraishy, H.M.; Sulaiman, G.M.; Mohammed, H.A.; Al-Gareeb, A.I.; Albuhadily, A.K.; Mohammed, S.G. Role of RhoA-ROCK signaling inhibitor fasudil in Alzheimer disease. Behav. Brain Res. 2025, 484, 115524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, X.; Collu, R.; Benavides, G.A.; Tian, R.; Darley-Usmar, V.; Xia, W.; Zhang, J. ROCK inhibitor fasudil attenuates neuroinflammation and associated metabolic dysregulation in the tau transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2024, 21, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crnich, E.; Sanchez, E.; Havens, M.A.; Kissel, D.S. Sulfur-bridging the gap: Investigating the electrochemistry of novel copper chelating agents for Alzheimer’s disease applications. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 28, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, C.; Zhuang, X.X.; Niu, Z.; Ai, R.; Lautrup, S.; Zheng, S.; Jiang, Y.; Han, R.; Gupta, T.S.; Cao, S.; et al. Amelioration of Alzheimer’s disease pathology by mitophagy inducers identified via machine learning and a cross-species workflow. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 6, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, E.F.; Hou, Y.; Palikaras, K.; Adriaanse, B.A.; Kerr, J.S.; Yang, B.; Lautrup, S.; Hasan-Olive, M.M.; Caponio, D.; Dan, X.; et al. Mitophagy inhibits amyloid-beta and tau pathology and reverses cognitive deficits in models of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2019, 22, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, J.H.; Shin, D.J.; Choi, S.M.; Nathan, A.B.P.; Kim, Y.Y.; Lee, D.Y.; Jeong, D.J.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, K.H.; Kim, Y.H.; et al. Selective induction of Rab9-dependent alternative mitophagy using a synthetic derivative of isoquinoline alleviates mitochondrial dysfunction and cognitive deficits in Alzheimer’s disease models. Theranostics 2024, 14, 56–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.J.; Kim, Y.Y.; Ma, R.; Choi, S.T.; Choi, S.M.; Cho, J.H.; Hur, J.Y.; Yoo, Y.; Han, K.; Park, H.; et al. Pharmacological targeting of mitophagy via ALT001 improves herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV1)-mediated microglial inflammation and promotes amyloid β phagocytosis by restricting HSV1 infection. Theranostics 2025, 15, 4890–4908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, F.H.P.; Ting, A.C.J.; Najimudin, N.; Watanabe, N.; Shamsuddin, S.; Zainuddin, A.; Osada, H.; Azzam, G. 3-[[(3S)-1,2,3,4-Tetrahydroisoquinoline-3-carbonyl]amino]propanoic acid (THICAPA) is protective against Aβ42-induced toxicity in vitro and in an Alzheimer’s disease drosophila. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2023, 78, 1944–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangeswaran, D.; Shamsuddin, S.; Balakrishn, V. A comprehensive review on the progress and challenges of tetrahydroisoquinoline derivatives as a promising therapeutic agent to treat Alzheimer’s disease. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

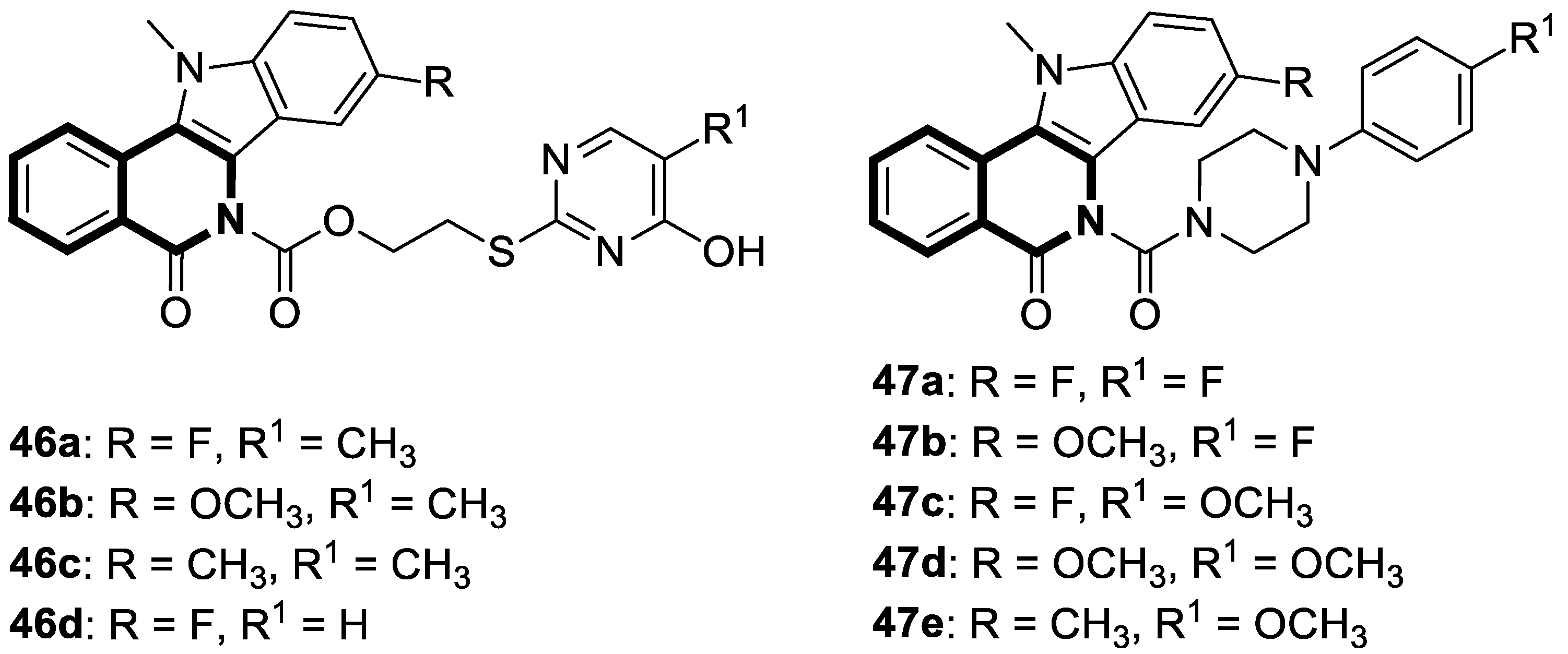

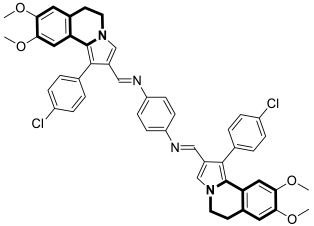

- Nevskaya, A.A.; Anikina, L.V.; Purgatorio, R.; Catto, M.; Nicolotti, O.; de Candia, M.; Pisani, L.; Borisova, T.N.; Miftyakhova, A.R.; Varlamov, A.V.; et al. Homobivalent lamellarin-like Schiff bases: In vitro evaluation of their cancer cell cytotoxicity and multitargeting anti-Alzheimer’s disease potential. Molecules 2021, 26, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberga, D.; Trisciuzzi, D.; Montaruli, M.; Leonetti, F.; Mangiatordi, G.F.; Nicolotti, O. A new approach for drug target and bioactivity prediction: The multifingerprint similarity search algorithm (MuSSeL). J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2019, 59, 586–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valipour, M.; Hosseini, A.; Di Sotto, A.; Irannejad, H. Dual action anti-inflammatory/antiviral isoquinoline alkaloids as potent naturally occurring anti-SARS-CoV-2 agents: A combined pharmacological and medicinal chemistry perspective. Phytother. Res. 2023, 37, 2168–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, C.; Li, K.; Peng, X.X.; Yao, T.J.; Wang, Z.Y.; Hu, P.; Cai, D.; Liu, H.Y. Berberine a traditional Chinese drug repurposing: Its actions in inflammation-associated ulcerative colitis and cancer therapy. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1083788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yahiaoui, S.; Khamtache-Abderrahim, S.; Kati, D.E.; Bettache, N.; Bachir-Bey, M. Anti-inflammatory potential of isoquinoline alkaloids from Fumaria officinalis: In vitro, in vivo, and in silico evaluation. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2025, 39, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, J.J.; van Staden, J. Anti-inflammatory principles of the plant family Amaryllidaceae. Planta Medica 2024, 90, 900–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.L.; Zhao, Y.L.; Qin, X.J.; Liu, Y.P.; Yang, X.W.; Luo, X.D. Diverse isoquinolines with anti-inflammatory and analgesic bioactivities from Hypecoum erectum. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 270, 113811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Leng, A.; Zhang, W.; Ying, X.; Stien, D. A novel alkaloid from Portulaca oleracea L. and its anti-inflammatory activity. Nat. Prod. Res. 2022, 36, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, P.; Liu, C. Anti-inflammatory effects of reticuline on the JAK2/STAT3/SOCS3 and p38 MAPK/NF-κB signaling pathway in a mouse model of obesity-associated asthma. Clin. Respir. J. 2024, 18, e13729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kem, W.R.; Soti, F.; Rocca, J.R.; Johnson, J.V. New pyridyl and dihydroisoquinoline alkaloids isolated from the Chevron Nemertean Amphiporus angulatus. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Peng, C.; Li, J.; Cheng, X.; Fan, X.; Li, J.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, Y. The anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities of 2Br-crebanine and stephanine from Stephania yunnanenses H. S.Lo. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 13, 1092583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Murata, T.; Shimizu, K.; Degerman, E.; Maurice, D.; Manganiello, V. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: Important signaling modulators and therapeutic targets. Oral Dis. 2015, 21, e25–e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurice, D.H.; Ke, H.; Ahmad, F.; Wang, Y.; Chung, J.; Manganiello, V.C. Advances in targeting cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014, 13, 290–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverberg, J.I.; French, L.E.; Warren, R.B.; Strober, B.; Kjøller, K.; Sommer, M.O.A.; Andres, P.; Felding, J.; Weiss, A.; Tutkunkardas, D.; et al. Pharmacology of orismilast, a potent and selective PDE4 inhibitor. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2023, 37, 721–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakkas, L.I.; Mavropoulos, A.; Bogdanos, D.P. Phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors in immune-mediated diseases: Mode of action, clinical applications, current and future perspectives. Curr. Med. Chem. 2017, 24, 3054–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Fan, C.; Feng, C.; Wu, Y.; Lu, H.; He, P.; Yang, X.; Zhu, F.; Qi, Q.; Gao, Y.; et al. Inhibition of phosphodiesterase-4 attenuates murine ulcerative colitis through interference with mucosal immunity. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 176, 2209–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

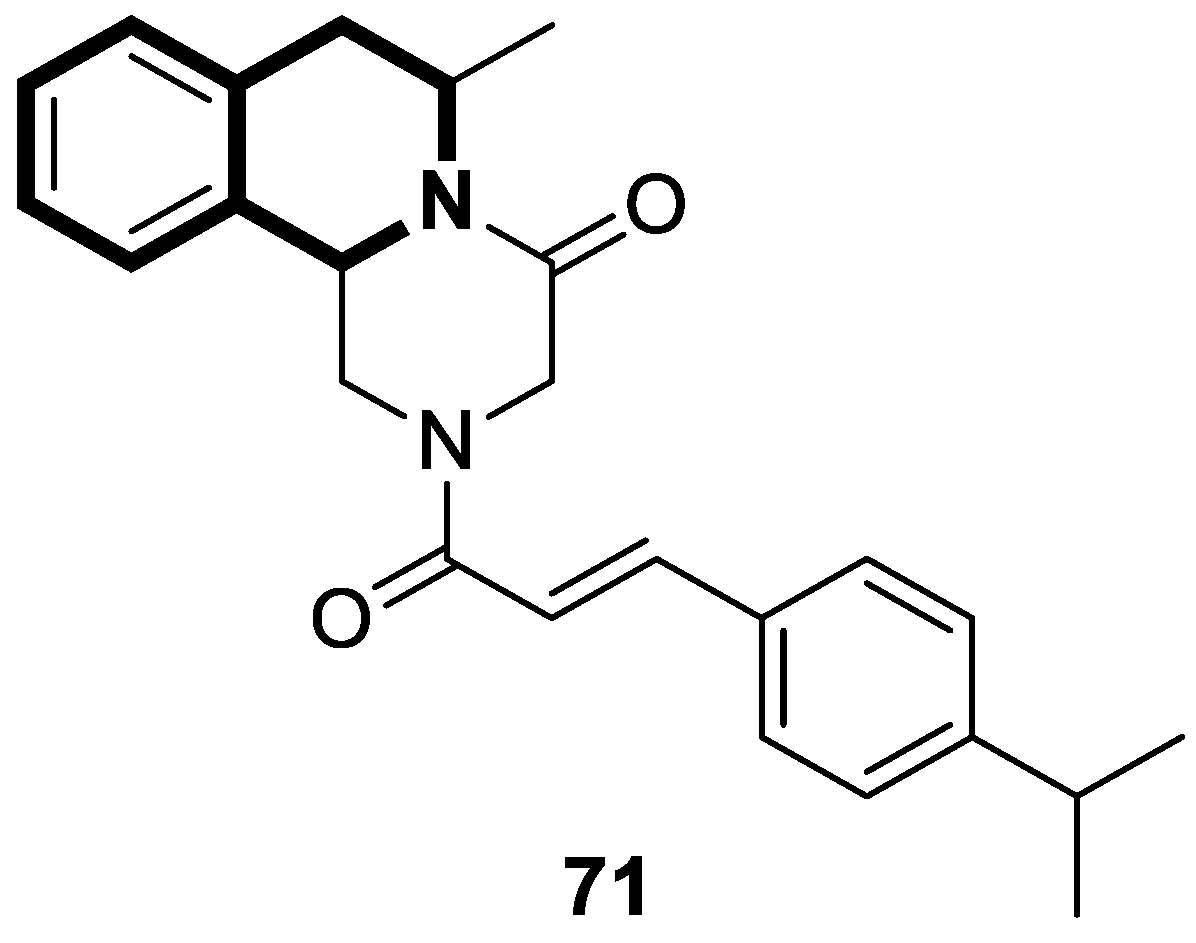

- Thirupataiah, B.; Mounika, G.; Sujeevan, R.G.; Sandeep, K.J.; Kapavarapu, R.; Medishetti, R.; Mudgal, J.; Mathew, J.E.; Shenoy, G.G.; Mallikarjuna, R.C.; et al. CuCl2-catalyzed inexpensive, faster and ligand/additive free synthesis of isoquinolin-1(2H)-one derivatives via the coupling-cyclization strategy: Evaluation of a new class of compounds as potential PDE4 inhibitors. Bioorganic Chem. 2021, 115, 105265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

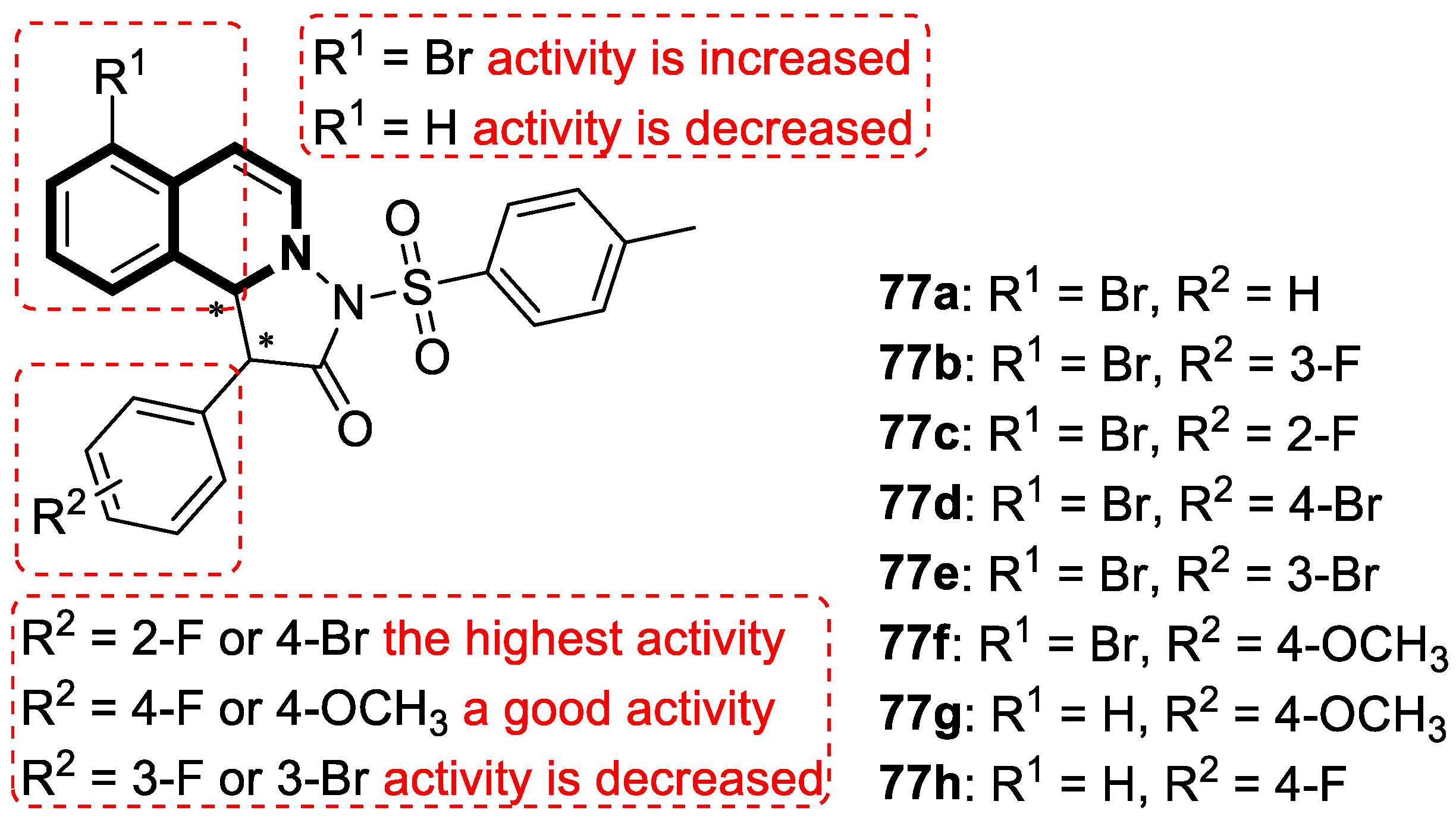

- Akhtar, M.; Niu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Luo, Z.; Tian, T.; Dong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Fareed, M.S.; Lin, L. Anti-inflammatory efficacy and relevant SAR investigations of novel chiral pyrazolo isoquinoline derivatives: Design, synthesis, in-vitro, in-vivo, and computational studies targeting iNOS. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 256, 115412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

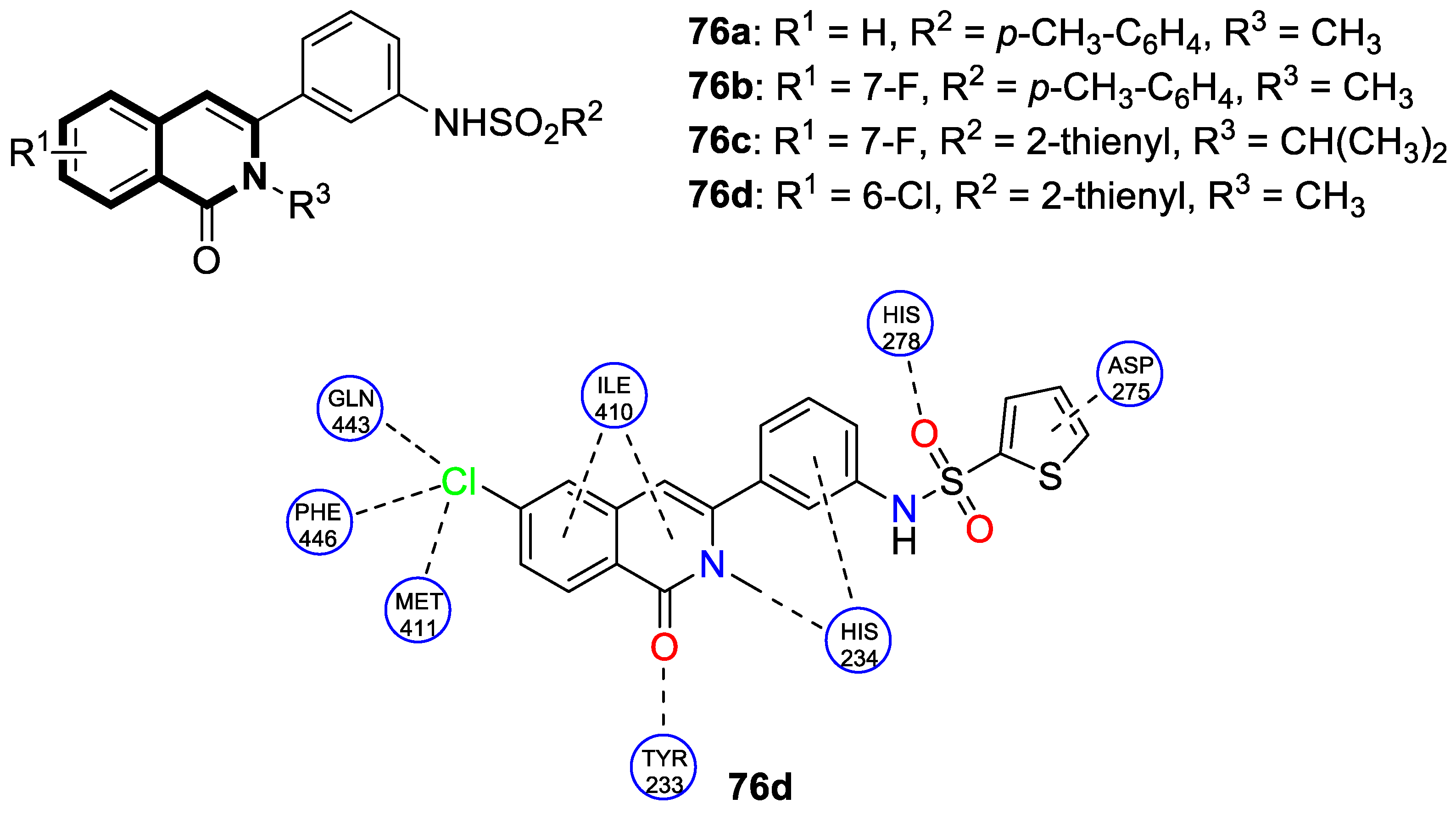

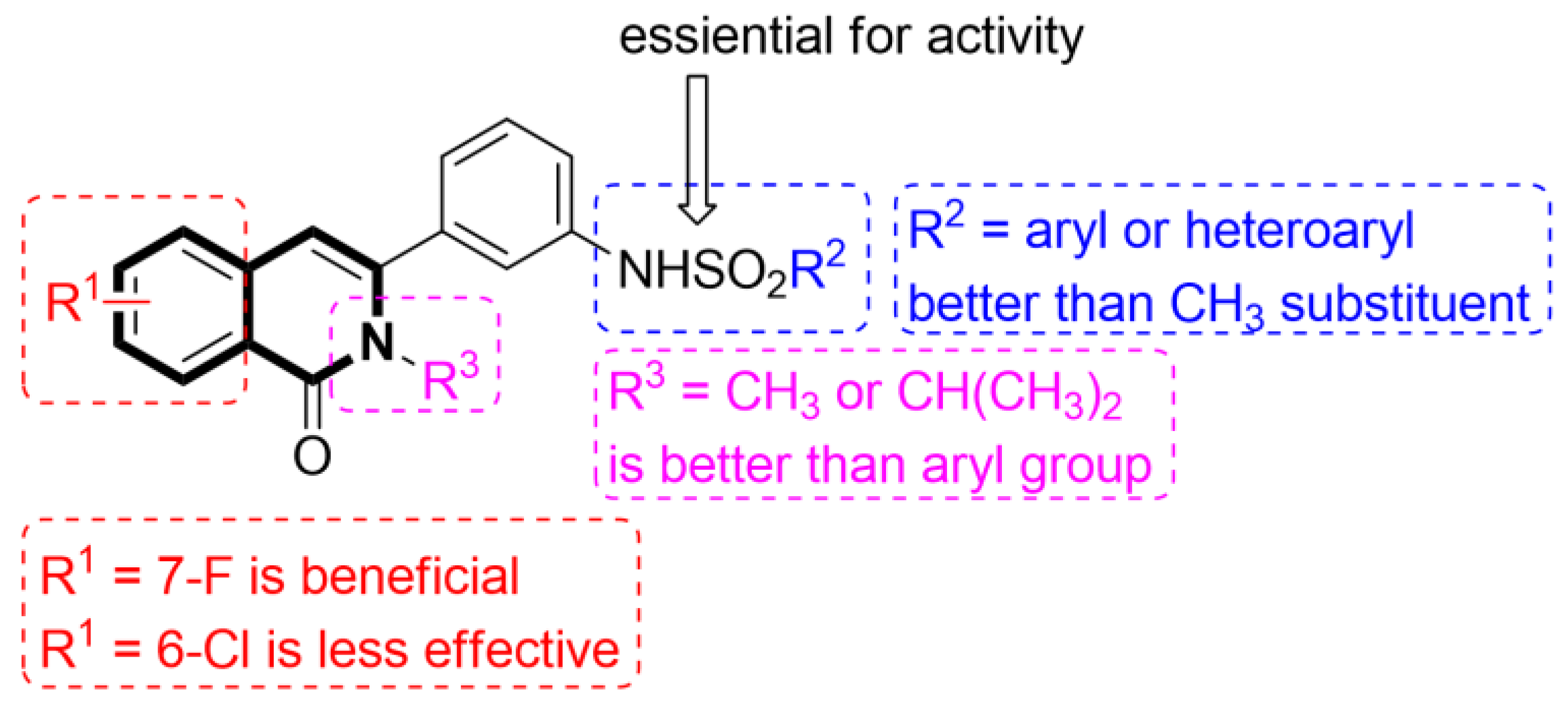

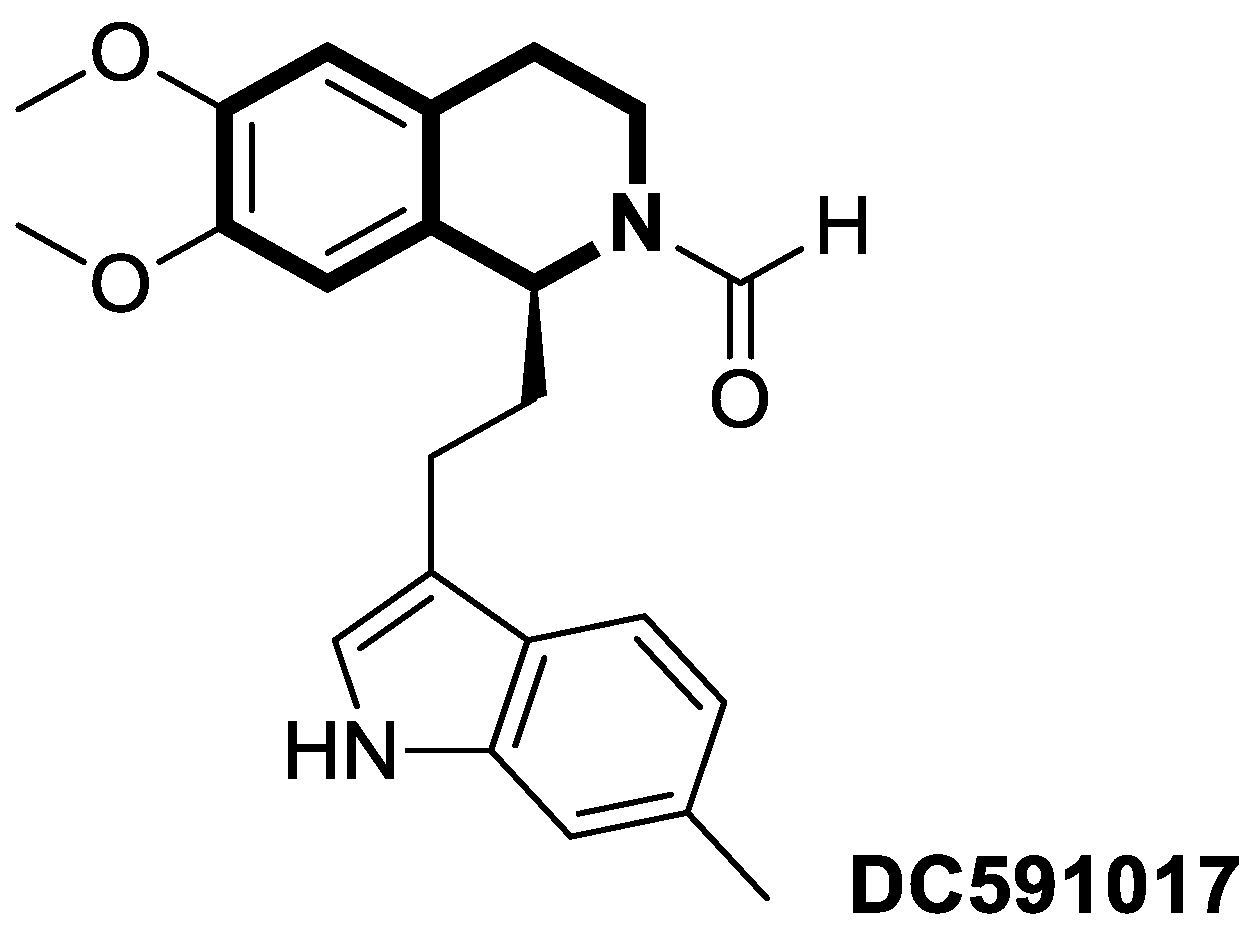

- Zhang, X.; Dong, G.; Li, H.; Chen, W.; Li, J.; Feng, C.; Gu, Z.; Zhu, F.; Zhang, R.; Li, M.; et al. Structure-aided identification and optimization of tetrahydro-isoquinolines as novel PDE4 inhibitors leading to discovery of an effective antipsoriasis agent. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 5579–5593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Feng, C.; Fan, C.; Yang, X.; Zhang, R.; Zhu, F.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, Y.; et al. DC591017, a phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE4) inhibitor with robust anti-inflammation through regulating PKA-CREB signaling. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020, 177, 113958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, T.; Lafforgue, P.; Pham, T. NSAID: Current limits to prescription. Jt. Bone Spine 2024, 91, 105685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfeen, M.; Srivastava, A.; Srivastava, N.; Khan, R.A.; Almahmoud, S.A.; Mohammed, H.A. Design, classification, and adverse effects of NSAIDs: A review on recent advancements. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2024, 112, 117899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, F.W.D.; McAlindon, M.E. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the gastrointestinal tract. Clin. Med. 2021, 21, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abo-Elmagd, M.I.; Hassan, R.M.; Aboutabl, M.E.; Amin, K.M.; El-Azzouny, A.A.; Aboul-Enein, M.N. Design, synthesis and anti-inflammatory assessment of certain substituted 1,2,4-triazoles bearing tetrahydroisoquinoline scaffold as COX 1/2-inhibitors. Bioorganic Chem. 2024, 150, 107577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antar, S.A.; Ashour, N.A.; Sharaky, M.; Khattab, M.; Ashour, N.A.; Zaid, R.T.; Roh, E.J.; Elkamhawy, A.; Al-Karmalawy, A.A. Diabetes mellitus: Classification, mediators, and complications; a gate to identify potential targets for the development of new effective treatments. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 168, 115734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabnis, R.W. Novel 6-methoxy-3,4-dihydro-1H-isoquinoline compounds for treating diabetes. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 891–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eli Lilly and Company. 6-Methoxy-3,4-dihydro-1H-isoquinoline Compounds Useful in the Treatment of Diabetes. International Application No. PCT/US2021/053691, 14 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Skoczyńska, A.; Ołdakowska, M.; Dobosz, A.; Adamiec, R.; Gritskevich, S.; Jonkisz, A.; Lebioda, A.; Adamiec-Mroczek, J.; Małodobra-Mazur, M.; Dobosz, T. PPARs in clinical experimental medicine after 35 years of worldwide scientific investigations and medical experiments. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, O.; Pradhan, T.; Chawla, G. Structural and Functional Insights into PPAR-γ: Review of its potential and drug design innovations for the development of antidiabetic agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 302, 118264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, A.A.; de Assis, R.N.F. Idealized PPARγ-based therapies: Lessons from bench and bedside. PPAR Res. 2012, 2012, 978687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morishita, K.; Ito, Y.; Otake, K.; Takahashi, K.; Yamamoto, M.; Kitao, T.; Ozawa, S.I.; Hirono, S.; Shirahase, H. Synthesis and evaluation of a novel series of 2,7-substituted-6-tetrazolyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline derivatives as selective peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ partial agonists. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2021, 69, 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morishita, K.; Miike, T.; Takeda, S.; Fukui, M.; Ito, Y.; Kitao, T.; Ozawa, S.I.; Hirono, S.; Shirahase, H. (S)-1,2,3,4-Tetrahydroisoquinoline derivatives substituted with an acidic group at the 6-position as a selective peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ partial agonist. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2019, 67, 1211–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, T.; Zhao, H.; Hu, L.; Shao, X.; Lu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ling, P.; Li, Y.; Zeng, K.; Chen, Q. Enhanced optical imaging and fluorescent labeling for visualizing drug molecules within living organisms. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2024, 14, 2428–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, D.B.; Lee, J.S. Natural-product-based fluorescent probes: Recent advances and applications. RSC Med. Chem. 2022, 14, 412–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, F.M.; Yuan, Z. PET/SPECT molecular imaging in clinical neuroscience: Recent advances in the investigation of CNS diseases. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2015, 5, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herholz, K.; Carter, S.F.; Jones, M. Positron emission tomography imaging in dementia. Br. J. Radiol. 2007, 80, S160–S167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gérard, T.; Colmant, L.; Malotaux, V.; Salman, Y.; Huyghe, L.; Quenon, L.; Dricot, L.; Ivanoiu, A.; Lhommel, R.; Hanseeuw, B. The spatial extent of tauopathy on [18F]MK-6240 tau PET shows stronger association with cognitive performances than the standard uptake value ratio in Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2024, 51, 1662–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasekar, M.; Ranjitha, V.; Rajasekar, K. Recent advances in fluorescent-based cation sensors for biomedical applications. Results Chem. 2023, 5, 100850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugaperumal, P.; Sriram, V.; Nallathambi, S.; Ayyanar, S.; Balasubramaniem, A. isoquinoline-fused benzimidazoles based highly selective fluorogenic receptors for detection of Cu2+, Fe3+, and Cl− ions: Cytotoxicity and HepG2 cancer cell imaging. Luminescence 2025, 40, e70137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, M.; Ji, X.; Stoika, R.; Liu, K.; Wang, L.; Song, Y. Synthesis of a novel fluorescent berberine derivative convenient for its subcellular localization study. Bioorganic Chem. 2020, 101, 104021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, S.; Nath, P.; Das, A.; Datta, A.; Baildya, N.; Duttaroy, A.K.; Pathak, S. A review on metal complexes and its anticancer activities: Recent updates from in vivo studies. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 171, 116211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndagi, U.; Mhlongo, N.; Soliman, M.E. Metal complexes in cancer therapy—An up-date from drug design perspective. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2017, 11, 599–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bormio Nunes, J.H.; Hager, S.; Mathuber, M.; Pósa, V.; Roller, A.; Enyedy, É.A.; Stefanelli, A.; Berger, W.; Keppler, B.K.; Heffeter, P.; et al. Cancer cell resistance against the clinically investigated thiosemicarbazone COTI-2 is based on formation of intracellular copper complex glutathione adducts and ABCC1-mediated efflux. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 13719–13732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaber, A.; Alsanie, W.F.; Kumar, D.N.; Refat, M.S.; Saied, E.M. Novel papaverine metal complexes with potential anticancer activities. Molecules 2020, 25, 5447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.Y.; Yang, L.M.; Wang, S.S.; Lu, H.; Wang, X.S.; Lu, Y.; Ni, W.X.; Liang, H.; Huang, K.B. Cycloplatinated (II) complex based on isoquinoline alkaloid elicits ferritinophagy-dependent ferroptosis in triple-negative breast cancer cells. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 6738–6748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Li, Y.; Shi, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Q. Ruthenium complexes as promising candidates against lung cancer. Molecules 2021, 26, 4389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Kim, C.Y.; Nam, T.G. Ruthenium complexes as anticancer agents: A brief history and perspectives. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2020, 14, 5375–5392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, X.Y.; Fong, K.W.; Kiew, L.V.; Chung, P.Y.; Liew, Y.K.; Delsuc, N.; Zulkefeli, M.; Low, M.L. Ruthenium(II) polypyridyl complexes as emerging photosensitisers for antibacterial photodynamic therapy. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2024, 250, 112425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Pan, C.; Shi, H.; Huang, T.; Huang, Y.L.; Deng, Y.Y.; Ni, W.X.; Man, W.L. Cytotoxic cis-ruthenium(III) bis(amidine) complexes. Dalton Trans. 2023, 52, 8540–8548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanenko, I.; Zalibera, M.; Schaniel, D.; Telser, J.; Arion, V.B. Ruthenium-nitrosyl complexes as NO-releasing molecules, potential anticancer drugs, and photoswitches based on linkage isomerism. Dalton Trans. 2022, 51, 5367–5393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Wang, J.; Cai, X.; Chen, S.; Zhang, J.; Li, B.; Chen, W.; Guo, X.; Luo, H.; Chen, J. Cyclometalated Ru(II)-isoquinoline complexes overcome cisplatin resistance of A549/DDP cells by downregulation of Nrf2 via Akt/GSK-3β/Fyn pathway. Bioorganic Chem. 2022, 119, 105516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, N.S.; Khan, T.M.; Chen, M.; Huang, K.B.; Hou, C.; Choudhary, M.I.; Liang, H.; Chen, Z.F. New copper complexes inducing bimodal death through apoptosis and autophagy in A549 cancer cells. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2020, 213, 111260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, J.; Gu, X.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Chemotherapeutic and targeted drugs-induced immunogenic cell death in cancer models and antitumor therapy: An update review. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1152934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.B.; Pan, N.L.; Liao, J.X.; Huang, M.Y.; Jiang, D.C.; Wang, J.J.; Qiu, H.J.; Chen, J.X.; Li, L.; Sun, J. Cyclometalated iridium(III) complexes as mitochondria-targeted anticancer and antibacterial agents to induce both autophagy and apoptosis. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2021, 219, 111450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.; Chan, D.S.-H.; Kwong, D.W.J.; He, H.-Z.; Leung, C.-H.; Ma, D.-L. Detection of nicking endonuclease activity using a G-quadruplex-selective luminescent switch-on probe. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 4561–4568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, S.S.; Li, M.Y.; Liu, R.; Zhu, M.F.; Yang, L.M.; Wang, F.Y.; Huang, K.B.; Liang, H. Cyclometalated iridium(III) complex based on isoquinoline alkaloid synergistically elicits the ICD response and IDO inhibition via autophagy-dependent ferroptosis. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2025, 15, 424–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, M.; Liang, Z.; Gong, Y.; Liu, B.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Wu, W.; Huang, Z.; et al. Cyclometalated iridium(III) complexes induce immunogenic cell death in HepG2 cells via paraptosis. Bioorganic Chem. 2023, 140, 106837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinicropi, M.S.; Ceramella, J.; Iacopetta, D.; Catalano, A.; Mariconda, A.; Rosano, C.; Saturnino, C.; El-Kashef, H.; Longo, P. Metal complexes with Schiff bases: Data collection and recent studies on biological activities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulechfar, C.; Ferkous, H.; Delimi, A.; Djedouani, A.; Kahlouche, A.; Boublia, A.; Darwish, A.S.; Lemaoui, T.; Verma, R.; Benguerba, Y. Schiff bases and their metal complexes: A review on the history, synthesis, and applications. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2023, 150, 110451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günnaz, S.; Yildiz, E.; Tunçel, O.A.; Yurt, F.; Erdem, A.; Irişli, S. Schiff base-platinum and ruthenium complexes and anti-Alzheimer properties. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2025, 264, 112790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grebinyk, A.; Chepurna, O.; Frohme, M.; Qu, J.; Patil, R.; Vretik, L.O.; Ohulchansky, T.Y. Molecular and nanoparticulate agents for photodynamic therapy guided by near infrared imaging. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 2024, 58, 100652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Wu, S.; Zhuang, W.; Huang, Z.; Zhou, L.; Li, Y.; Chen, M.; You, J. Direct [4 + 2] Cycloaddition to Isoquinoline-Fused Porphyrins for Near-Infrared Photodynamic Anticancer Agents. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

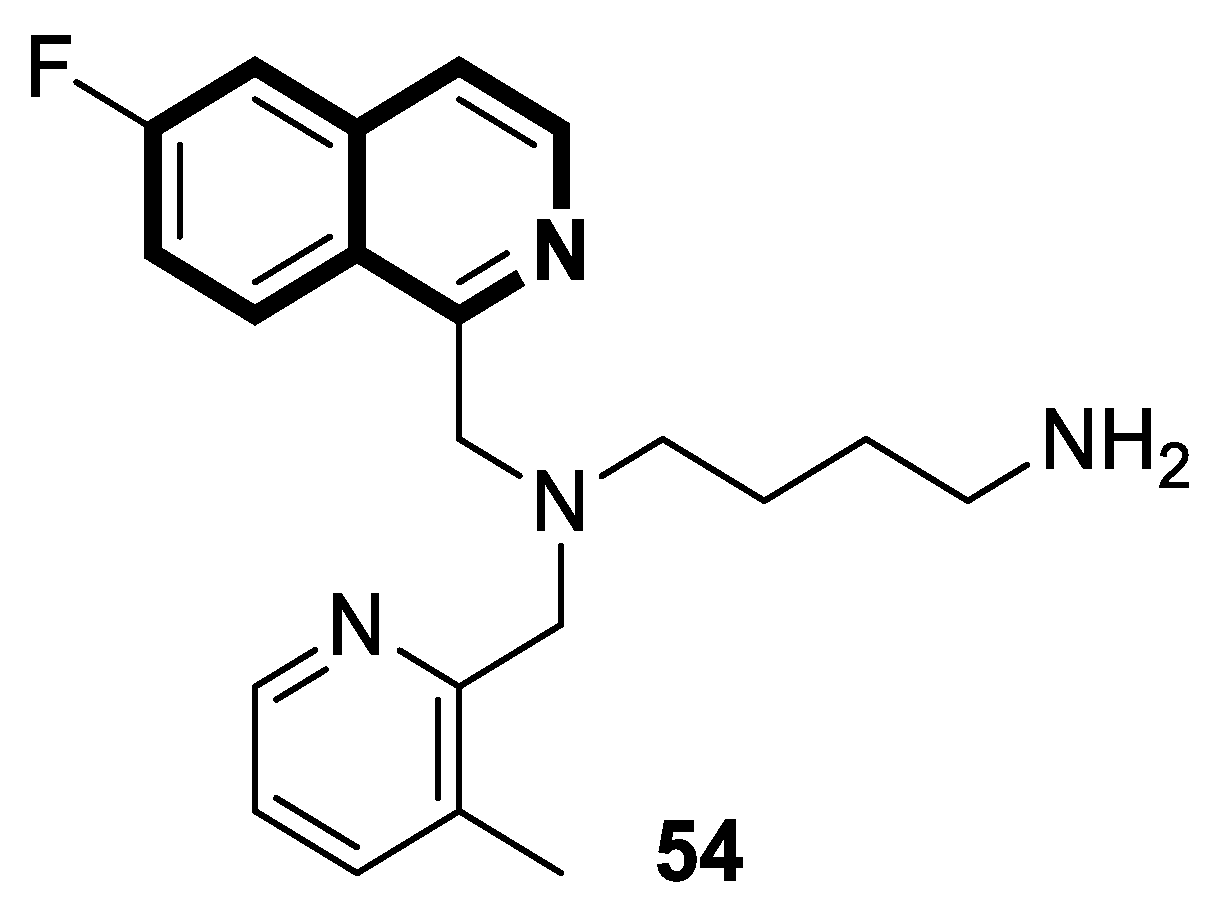

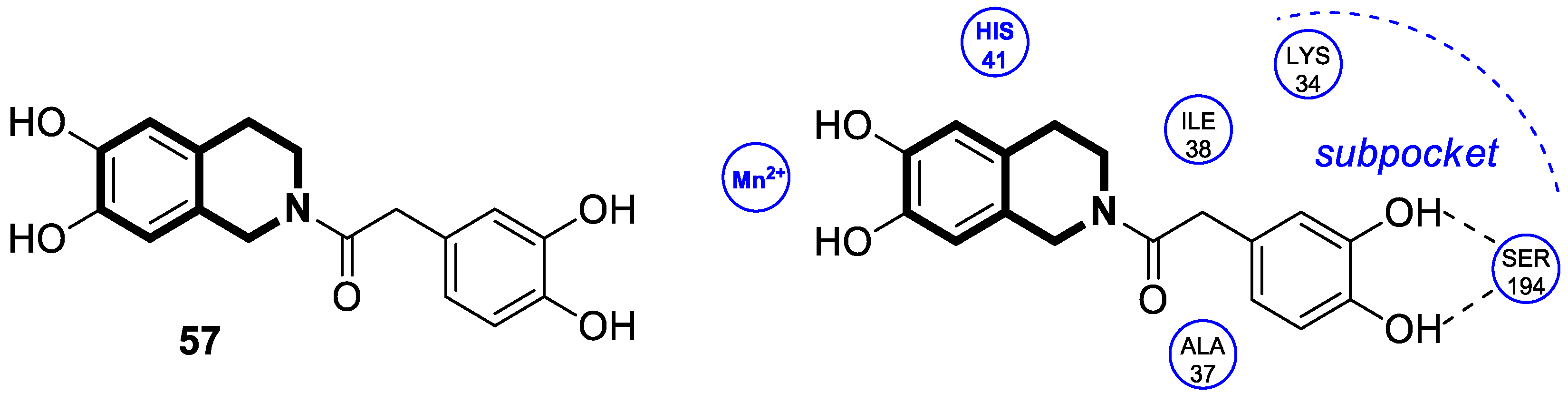

| Structure | Biological Activity | Molecular Target | Name/ Number | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anticancer | Akt | 1a | [34] |

| Anticancer | Oxidative stress, mitochondrial-dependent toxicity, oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) | 2 | [38] |

| Anticancer | Topo I | 4 | [40] |

| Anticancer | PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway | Toyaburgine | [51] |

| Anticancer | MAPK/ERK or Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK and p38 MAPK signaling pathways, caspase-3 clevage of GSDME | 8 | [52] |

| Anticancer | α,β-tubulin colchicine binding site | 9a | [53] |

| Anticancer | Apoptosis via mitochondrial dysfunction, caspase-3 and PARP-1 | 10a | [58] |

| Anticancer | Apoptosis, G2/M phase | 12 | [60] |

| Anticancer | Autophagy, anti-angiogenic effect | 13 | [71] |

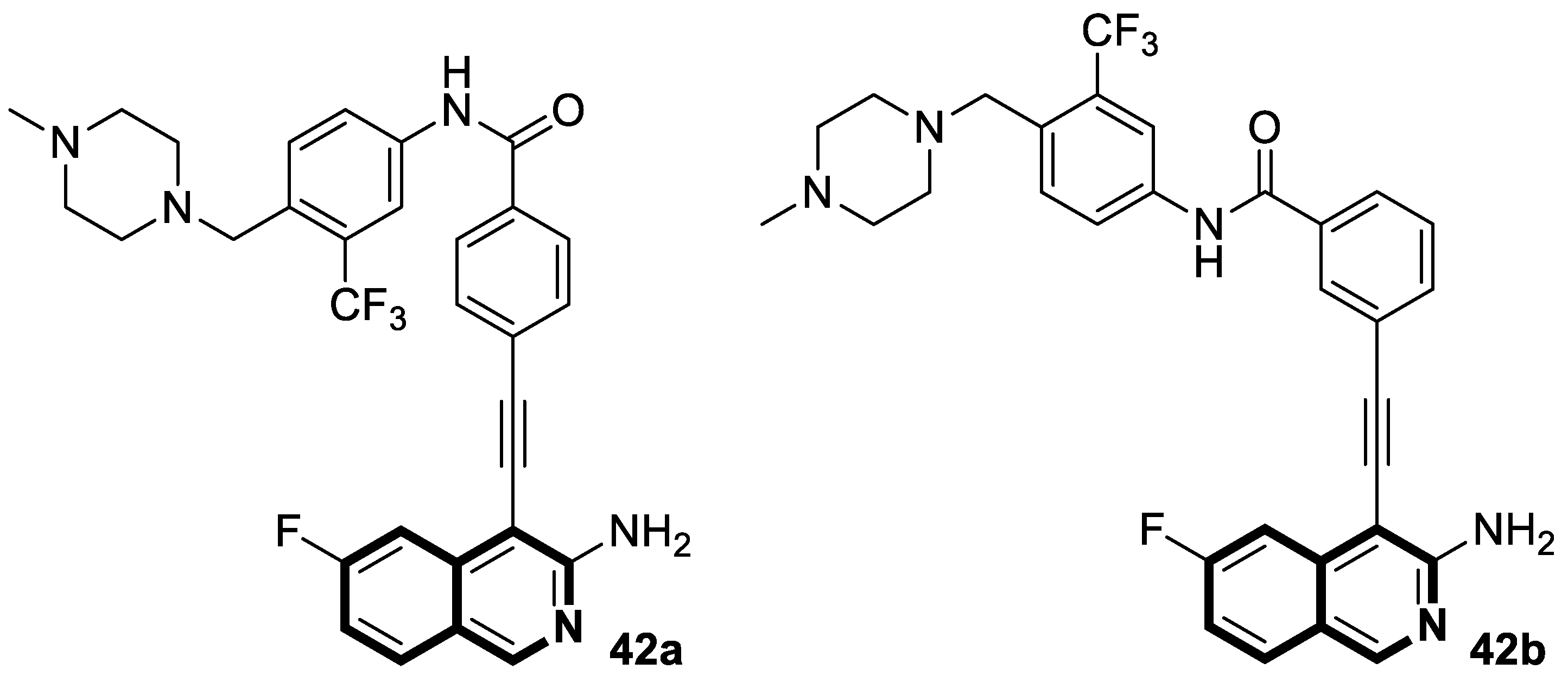

| Anticancer | ALK | 16a-b | [81] |

| Anticancer | G2/M phase, mitochondrial-dependent apoptotic pathway | 17 | [82] |

| Anticancer | NF-κB signaling pathway | 18 | [83] |

| Anticancer | gp-P and CYP1B1 | 20 | [87] |

| Anticancer | G2/M phase, CDK2 | 22 | [90] |

| Anticancer | Apoptosis, G0-G1 and G2/M phases, HSP90 | 24 | [91] |

| Anticancer | G2/M phase, RET | 26a | [92] |

| Anticancer | P-gp/MRP1 | 31 | [99] |

| Anticancer | G2/M phase, cellular apoptosis, tubulin polymerization | 35 | [103] |

| Anticancer | PPARγ, AKT | 37 | [107] |

| Anticancer | MAPKs signaling pathway | LFZ-4-46 | [108] |

| Anticancer | EGFR | 39a | [115] |

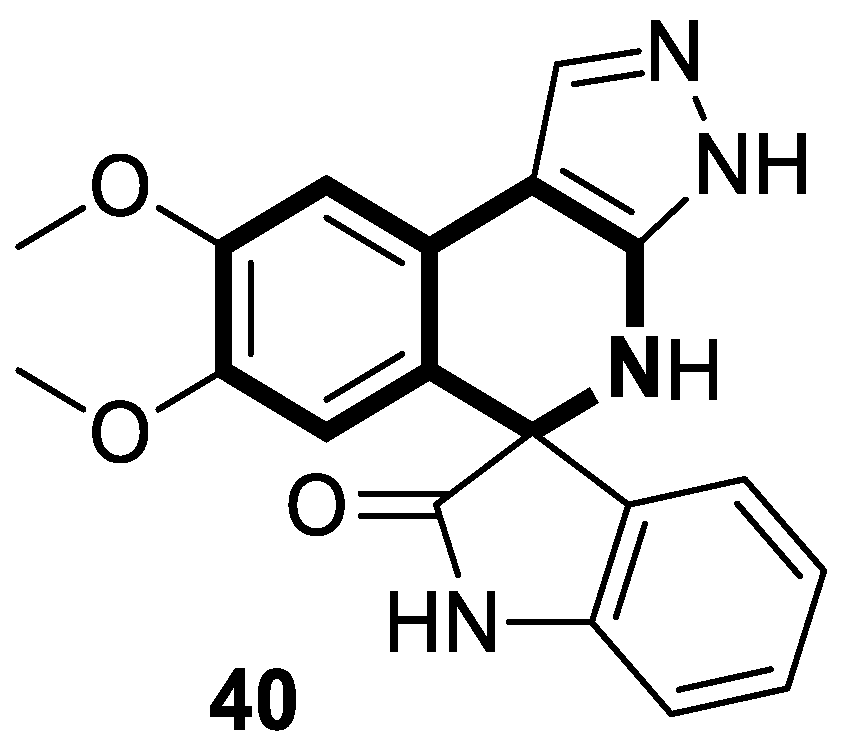

| Anticancer | IL-6 | 40 | [119] |

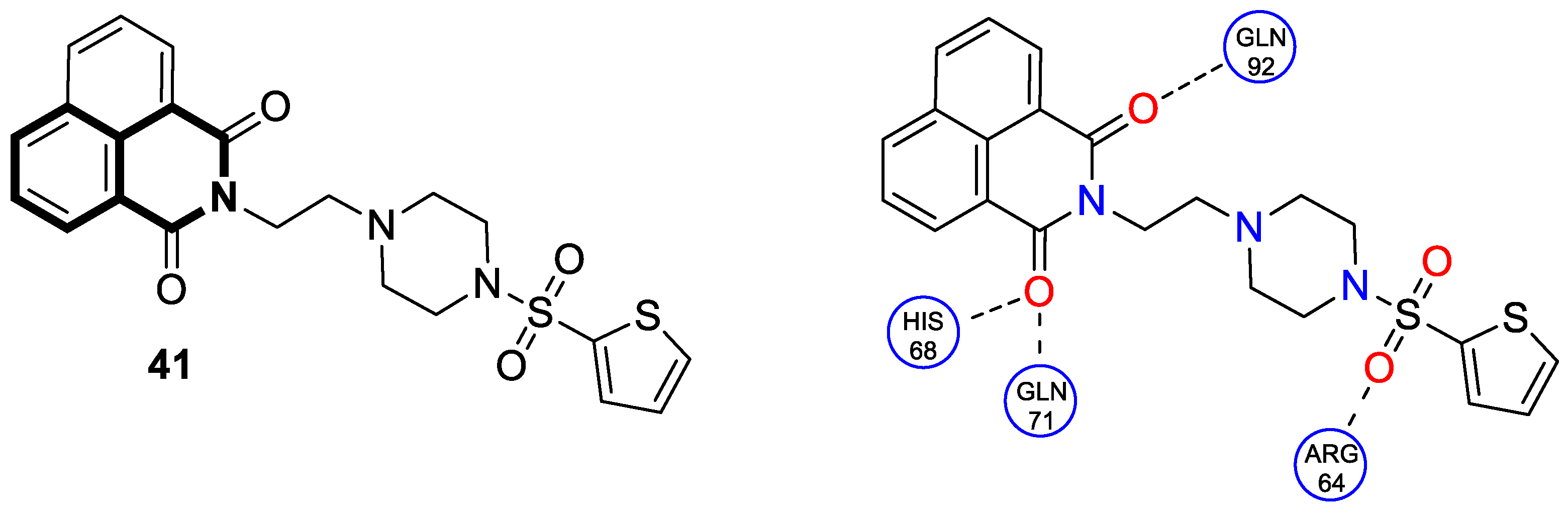

| Anticancer | Carbonic anhydrase isoform IX (CAIX) | 41 | [120] |

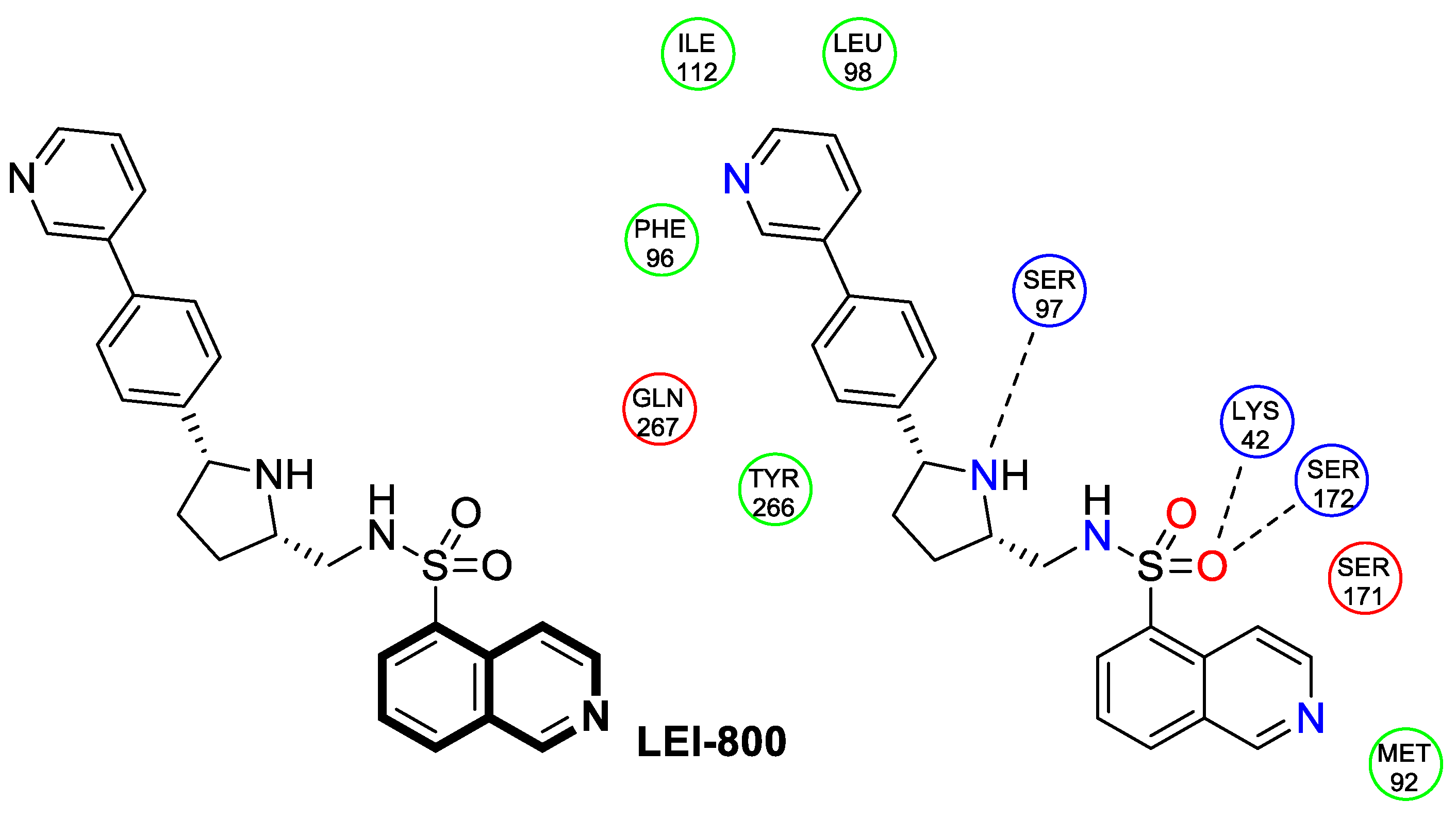

| Antibacterial | DNA-gyrase | LEI-800 | [143] |

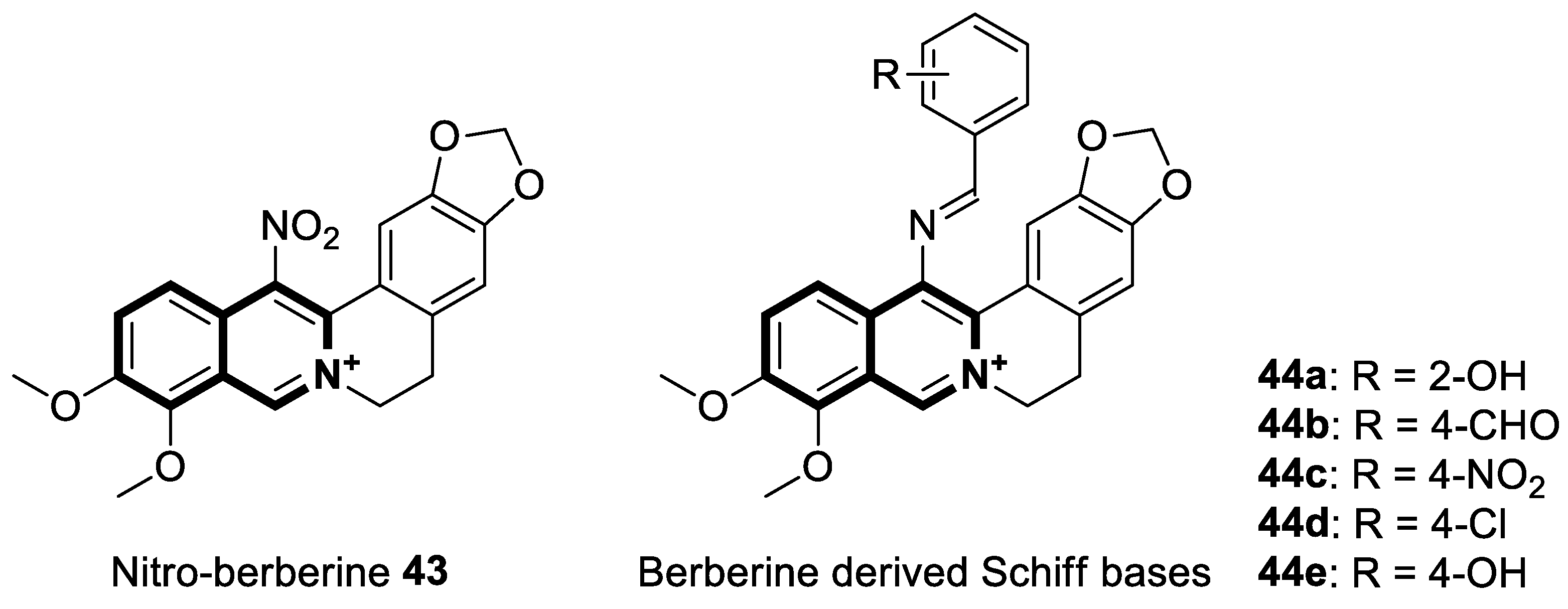

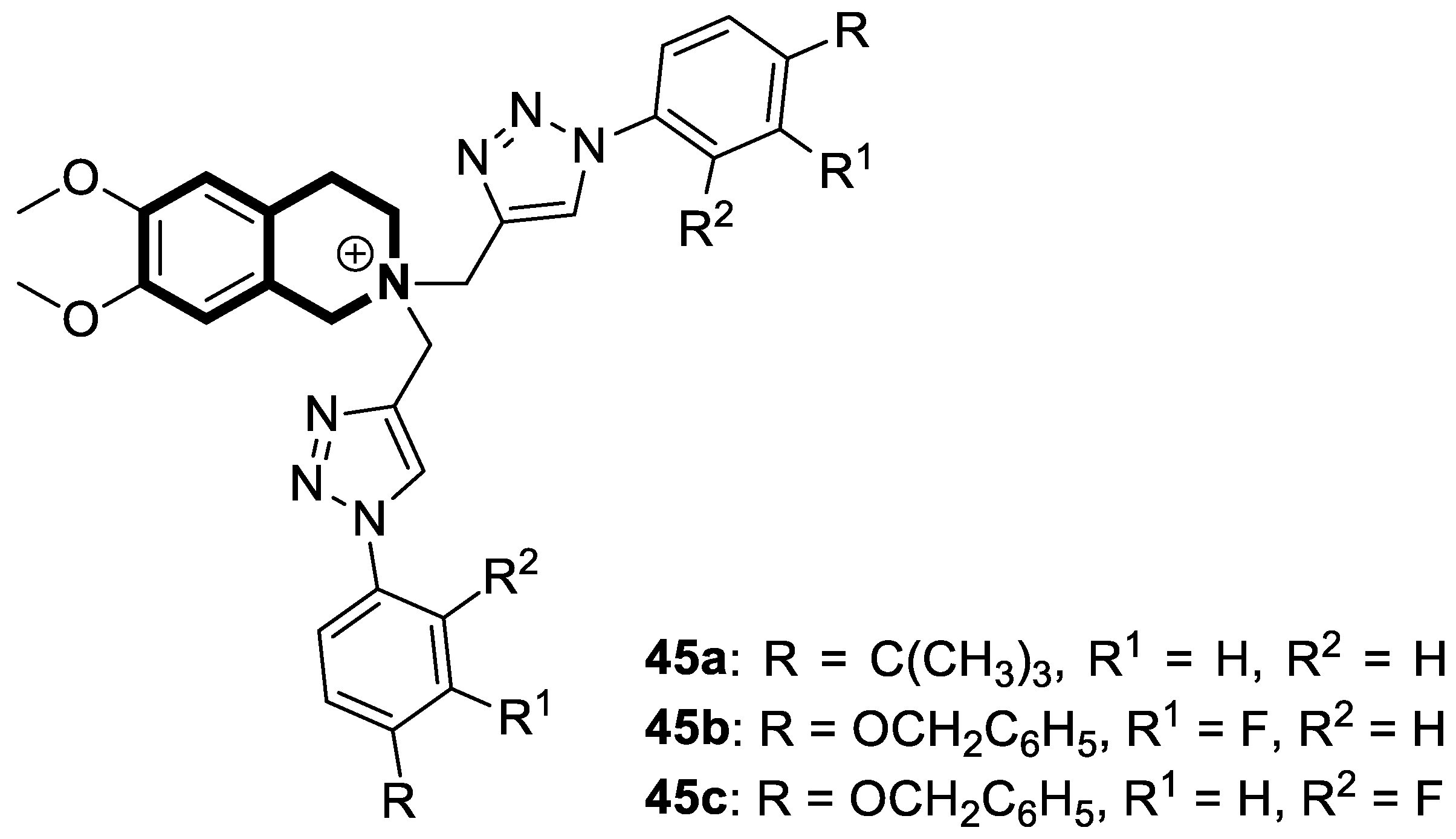

| Antibacterial | S. aureus, B. subtilis, M. tuberculosis H37Rv | 45a | [145] |

| Anti-mycobacterial | Enoyl reductase 4TZK | 49 | [152] |

| Antifungal | A. solani, A. alternata, P. piricola | 50 | [156] |

| Antimicrobial | S. aureus, B. subtilis, E. coli, C. albicans, F. oxysporum, A. flavus, supercoiled DNA | 53 | [158] |

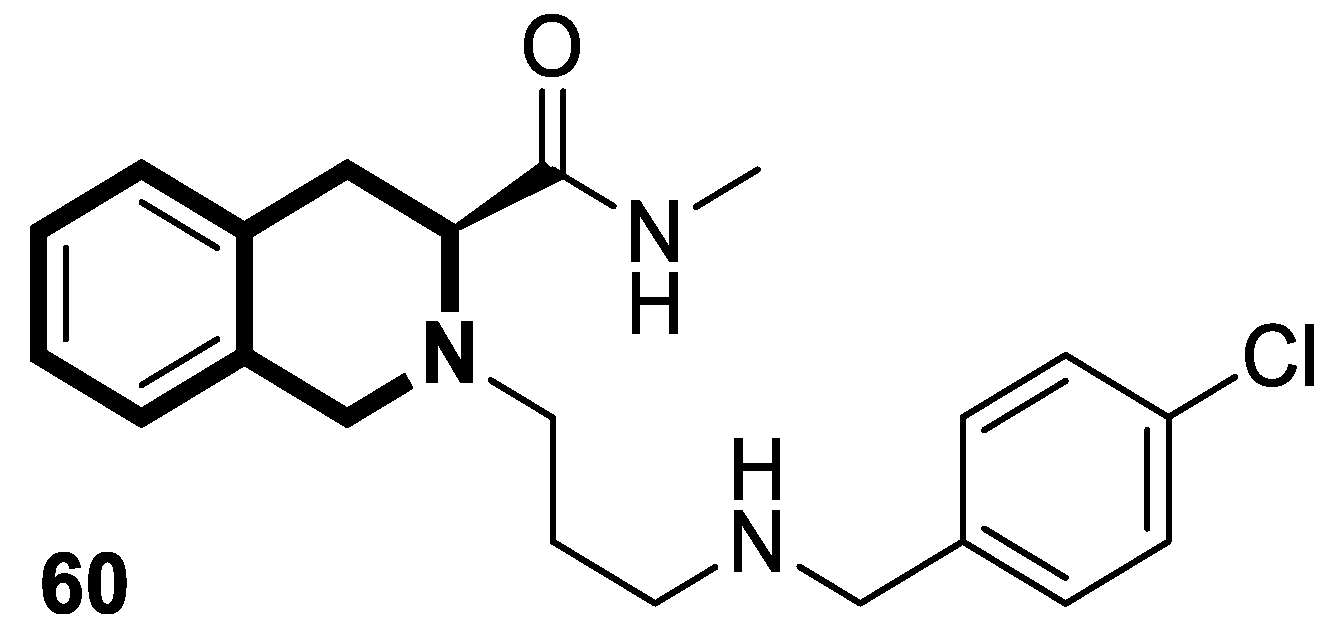

| Antiviral | Chemokine receptor CXCR4, HIV-1 and HIV-2 | 54 | [164] |

| Antiviral | HBV capsid assembly | AB-836 | [167] |

| Antiviral | Coronavirus OC-43 and 229 | 56 | [173] |

| Antiviral | Influenza A, PAN endonuclease | 57 | [176] |

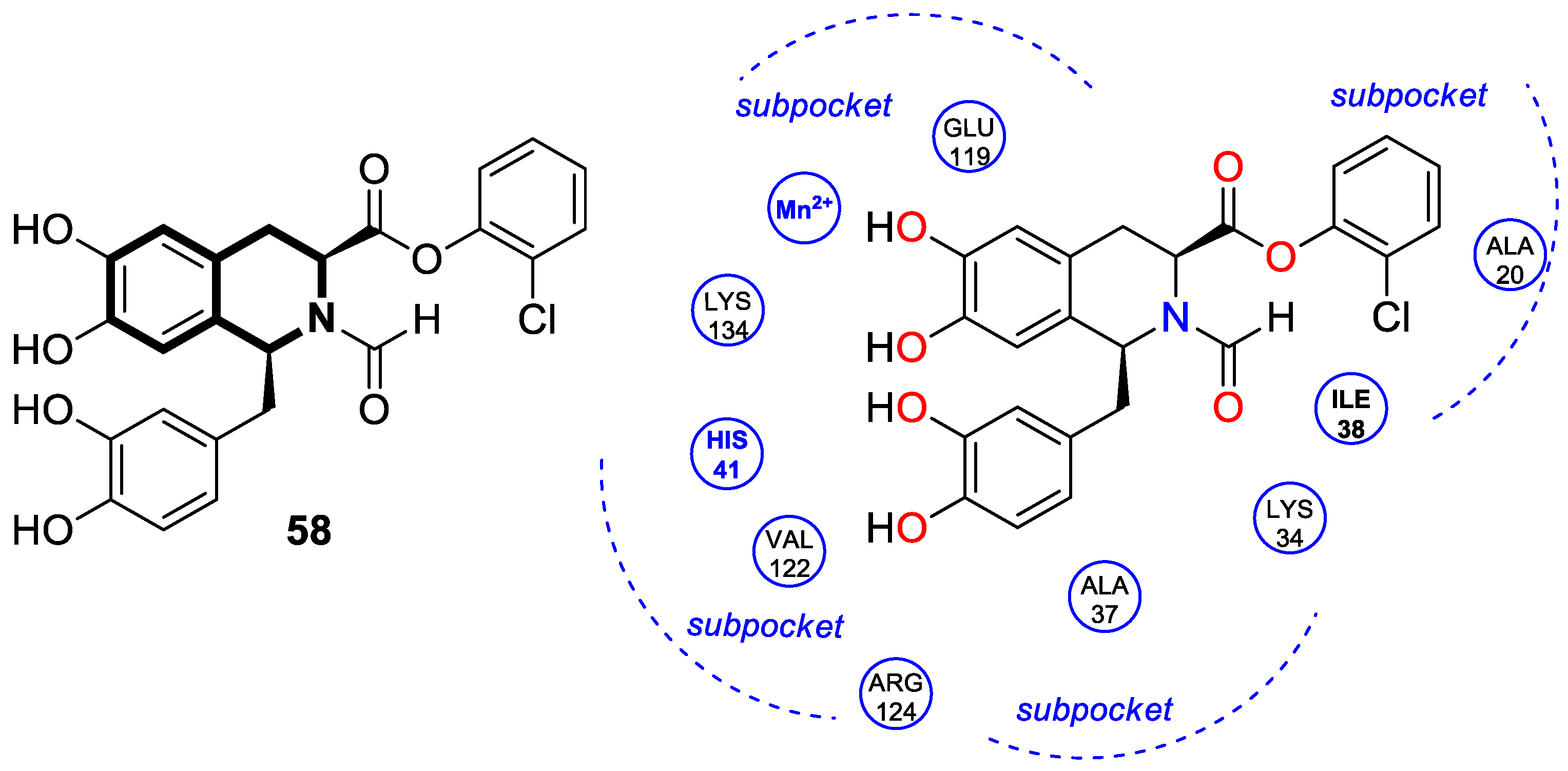

| Antiviral | Influenza A, PAN endonuclease | 58 | [177] |

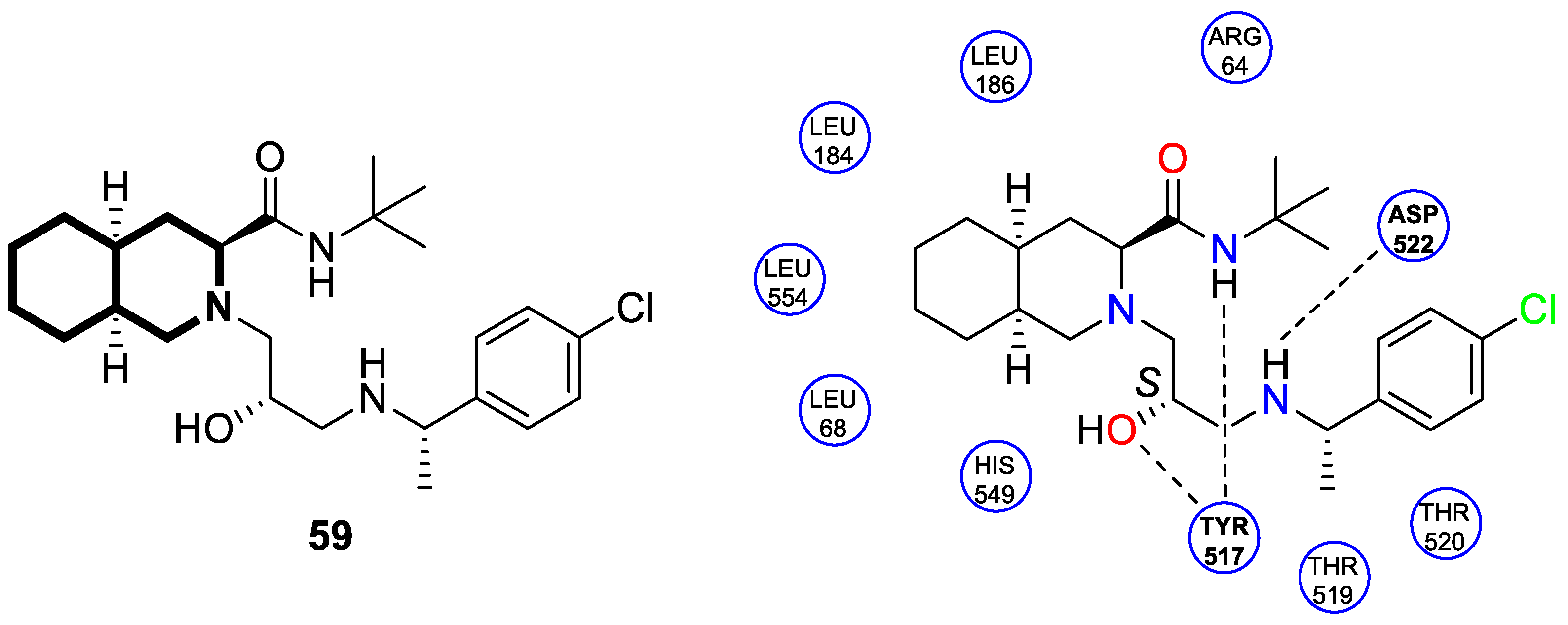

| Antiviral | Ebola virus glycoprotein (EBOV-GP) | 59 | [179] |