Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Visible Light-Driven BiVO4 Nanoparticles: Effects of Eu3+ Ions on the Luminescent, Structural, and Photocatalytic Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Structural and Morphological Properties of the Bi1−xEuxVO4 (x = 0, 0.03, 0.06, 0.09, and 0.12) Samples

2.1.1. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis

2.1.2. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

2.2. Optical Properties of the Bi1−xEuxVO4 (x = 0, 0.03, 0.06, 0.09, and 0.12) Samples

2.2.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

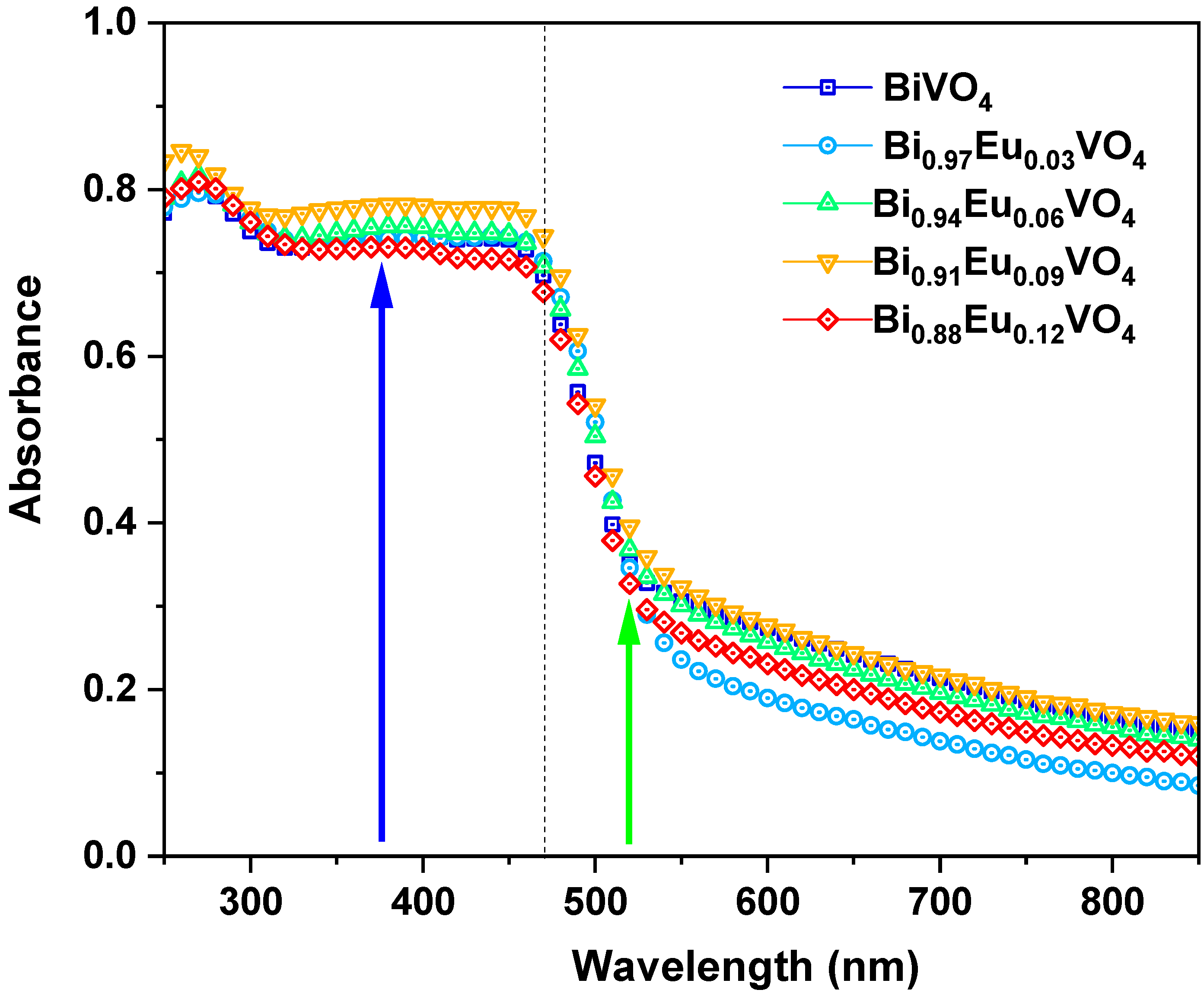

2.2.2. Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy (DRS)

2.2.3. Optical Absorption

2.2.4. Photoluminescence (PL) Emission Measurements Using Continuous-Wave Lasers

2.2.5. Time-Resolved Fluorescence Spectroscopy (TRS)

2.2.6. Micro-Raman Spectroscopy Measurements

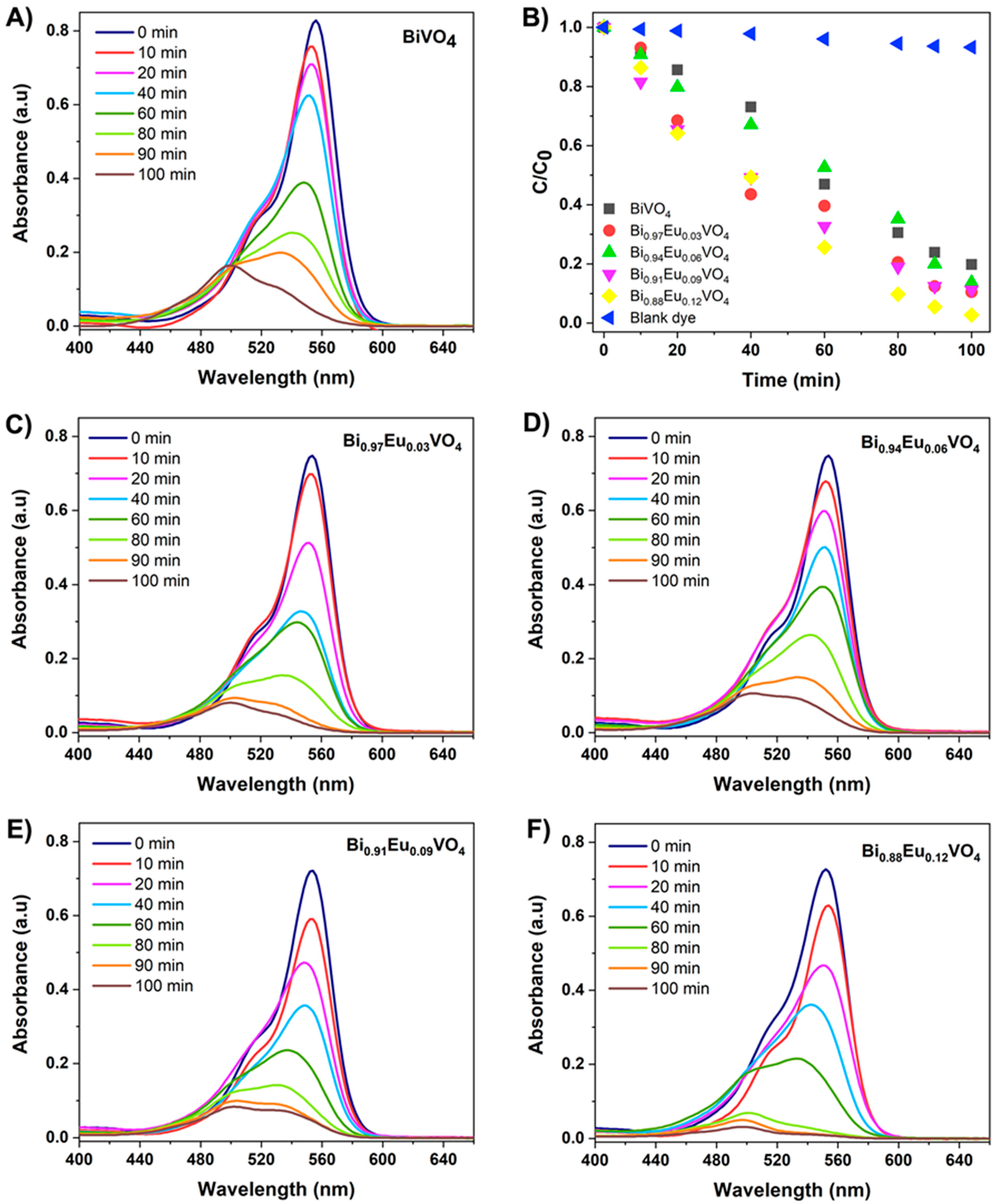

2.3. Photocatalytic Activity of Bi1−xEuxVO4 (x = 0, 0.03, 0.06, 0.09, 0.12) Samples

3. Discussion

The Formation of ms- or tz-Crystalline Phase in Bi1−xEuxVO4 (x = 0, 0.03, 0.06, 0.09, and 0.12) Samples

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Synthesis of Bi1−xEuxVO4 (x = 0.03, 0.06, 0.09, and 0.12) Samples

4.3. Synthesis of BiVO4 4samples

4.4. Characterization Instrumentation

4.5. Photocatalytic Test

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jabbar, Z.H.; Graimed, B.H.; Ammar, S.H.; Sabit, D.A.; Najim, A.A.; Radeef, A.Y.; Taher, A.G. The Latest Progress in the Design and Application of Semiconductor Photocatalysis Systems for Degradation of Environmental Pollutants in Wastewater: Mechanism Insight and Theoretical Calculations. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2024, 173, 108153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Zou, Y.; Yan, J.; Liu, Y.; Shukrullah, S.; Naz, M.Y.; Hussain, H.; Khan, W.Q.; Khalid, N.R. Semiconductor Photocatalysts: A Critical Review Highlighting the Various Strategies to Boost the Photocatalytic Performances for Diverse Applications. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 311, 102830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basavarajappa, P.S.; Patil, S.B.; Ganganagappa, N.; Raghava, K.; Raghu, A.V.; Venkata, C. ScienceDirect Recent Progress in Metal-Doped TiO2, Non-Metal Doped/Codoped TiO2 and TiO2 Nanostructured Hybrids for Enhanced Photocatalysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 7764–7778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, M.; Rauf, S.; Irfan, M.; Hayat, A. Recent Developments, Advances and Strategies in Heterogeneous Photocatalysts for Water Splitting. Nanoscale Adv. 2024, 6, 1286–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wafi, A.; Aji, D.; Mansoob, M. Results in Chemistry Recent Advances in Photocatalysis: From Laboratory to Market. Results Chem. 2025, 18, 102672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Jia, S.; Wei, J. A visible light active, carbon–nitrogen–sulfur co- doped TiO2/g-C3N4 Z-scheme heterojunction as an effective photocatalyst to remove dye pollutants. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 16747–16754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, L.; Marschall, R. Recent Advances in Semiconductor Heterojunctions and Z-Schemes for Photocatalytic Hydrogen Generation; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 380, ISBN 0123456789. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.; Ma, Y.; Vequizo, J.J.M.; Nakabayashi, M.; Gu, C.; Tao, X.; Yoshida, H.; Pihosh, Y.; Nishina, Y.; Yamakata, A.; et al. Efficient and Stable Visible-Light-Driven Z-Scheme Overall Water Splitting Using an Oxysulfide H2 Evolution Photocatalyst. Nat. Comm. 2024, 15, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Cook, S.; Wang, P.; Hwang, H. Science of the Total Environment In Vitro Evaluation of Cytotoxicity of Engineered Metal Oxide Nanoparticles. Sci. Total Environ. 2009, 407, 3070–3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivaji, K.; Sridharan, K.; Kirubakaran, D.D.; Velusamy, J.; Emadian, S.S.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Devadoss, A.; Nagarajan, S.; Das, S.; Pitchaimuthu, S. Biofunctionalized CdS Quantum Dots: A Case Study on Nanomaterial Toxicity in the Photocatalytic Wastewater Treatment Process. ACS Omega 2023, 22, 19413–19424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sharma, G.; Naushad, M.; Al-muhtaseb, A.H.; García-peñas, A.; Tessema, G.; Si, C.; Stadler, F.J. Bio-Inspired and Biomaterials-Based Hybrid Photocatalysts for Environmental Detoxification: A Review. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 382, 122937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradiprao, A.; Bobade, R.G.; Doong, R.; Pandit, B.; Minh, N.; Ambare, R.C.; Hoang, T.; Jashvant, K. Bio-Based Nanomaterials as Effective, Friendly Solutions and Their Applications for Protecting Water, Soil, and Air. Mater. Today Chem. 2025, 46, 102688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Q. Alijani, H.; Iravani, S.; Varma, R.S. Bismuth Vanadate (BiVO4) Nanostructures: Eco-Friendly Synthesis and Their Photocatalytic Applications. Catalysts 2023, 13, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinković, D.; Righini, G.C.; Ferrari, M. Synthesis, Optical, and Photocatalytic Properties of the BiVO4 Semiconductor Nanoparticles with Tetragonal Zircon-Type Structure. Photonics 2025, 12, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinković, D.; Righini, G.C.; Ferrari, M. Advances in Synthesis and Applications of Bismuth Vanadate-Based Structures. Inorganics 2025, 13, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut, D.T. Exploring the Dual Role of BiVO4 Nanoparticles: Unveiling Enhanced Antimicrobial Efficacy and Photocatalytic Performance. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2025, 114, 198–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tot, N.; Vasiljević, B.; Davidović, S.; Pustak, A.; Marić, I.; Prekodravac Filipović, J.; Marinković, D. Facile Microwave Production and Photocatalytic Activity of Bismuth Vanadate Nanoparticles over the Acid Orange 7. Processes 2025, 13, 3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalrindiki, F.; Premjit Singh, N.; Mohondas Singh, N. A Review of Synthesis, Photocatalytic, Photoluminescence and Antibacterial Properties of Bismuth Vanadate-Based Nanomaterial. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2024, 168, 112846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamble, G.S.; Natarajan, T.S.; Patil, S.S.; Thomas, M.; Chougale, R.K.; Sanadi, P.D.; Siddharth, U.S.; Ling, Y.C. BiVO4 As a Sustainable and Emerging Photocatalyst: Synthesis Methodologies, Engineering Properties, and Its Volatile Organic Compounds Degradation Efficiency. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Peng, B.; Wang, Z.; Han, Q. Advances in Metal or Nonmetal Modification of Bismuth-Based Photocatalysts. Wuli Huaxue Xuebao/Acta Phys.-Chim. Sin. 2024, 40, 2305048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N.A.; Kiong, T.S.; Ismail, A.F. Pioneering Sustainable Energy Solutions with Rare-Earth Nanomaterials: Exploring Pathways for Energy Conversion and Storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 93, 607–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, Z.; Suo, H.; Chen, Y.; Xiang, J.; Guo, C. Temperature Self-Monitoring Photothermal Nano-Particles of Er3+/Yb3+ Co-Doped Zircon-Tetragonal BiVO4. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gschwend, P.M.; Starsich, F.H.L.; Keitel, R.C.; Pratsinis, S.E. Nd3+-Doped BiVO4 Luminescent Nanothermometers of High Sensitivity. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 7147–7150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nexha, A.; Carvajal, J.J.; Pujol, M.C.; Díaz, F.; Aguiló, M. Lanthanide Doped Luminescence Nanothermometers in the Biological Windows: Strategies and Applications. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 7913–7987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starsich, F.H.L.; Gschwend, P.; Sergeyev, A.; Grange, R.; Pratsinis, S.E. Deep Tissue Imaging with Highly Fluorescent Near-Infrared Nanocrystals after Systematic Host Screening. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 8158–8166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurga, N.; Runowski, M.; Grzyb, T. Lanthanide-Based Nanothermometers for Bioapplications: Excitation and Temperature Sensing in Optical Transparency Windows. J. Mater. Chem. C 2024, 12, 12218–12248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, B.S.; Hudry, D.; Busko, D.; Turshatov, A.; Howard, I.A. Photon Upconversion for Photovoltaics and Photocatalysis: A Critical Review. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 9165–9195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, K.; Wu, L.; Han, T.; Gao, L.; Wang, P.; Chai, H.; Jin, J. Dual Modification of BiVO4 Photoanode by Rare Earth Element Neodymium Doping and Further NiFe2O4 Co-Catalyst Deposition for Efficient Photoelectrochemical Water Oxidation. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 923, 166352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, S.; Jamil, A.; Khan, M.S.; Alazmi, A.; Abuilaiwi, F.A.; Shahid, M. Gd-Doped BiVO4 Microstructure and Its Composite with a Flat Carbonaceous Matrix to Boost Photocatalytic Performance. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 913, 165214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orona-Návar, C.; Park, Y.; Srivastava, V.; Hernández, N.; Mahlknecht, J.; Sillanpää, M.; Ornelas-Soto, N. Gd3+ Doped BiVO4 and Visible Light-Emitting Diodes (LED) for Photocatalytic Decomposition of Bisphenol A, Bisphenol S and Bisphenol AF in Water. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yin, X.; Zhao, H.; Shu, W.; Xin, F.; Wang, H.; Luo, X.; Gong, N.; Xue, X.; Pang, Q.; et al. Near-Infrared-Emitting Upconverting BiVO4 Nanoprobes for in Vivo Fluorescent Imaging. Spectrochim. Acta-Part. A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2022, 270, 120811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Tan, G.; Zhao, C.; Xu, C.; Su, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ren, H.; Xia, A.; Shao, D.; Yan, S. Enhanced Photocatalytic Mechanism of the Nd-Er Co-Doped Tetragonal BiVO4 Photocatalysts. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 213, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regmi, C.; Kshetri, Y.K.; Jeong, S.H.; Lee, S.W. BiVO4 as Highly Efficient Host for Near-Infrared to Visible Upconversion. J. Appl. Phys. 2019, 125, 43101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regmi, C.; Kshetri, Y.K.; Ray, S.K.; Pandey, R.P.; Lee, S.W. Utilization of Visible to NIR Light Energy by Yb+3, Er+3 and Tm+3 Doped BiVO4 for the Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 392, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obregón, S.; Colón, G. On the Origin of the Photocatalytic Activity Improvement of BiVO4 through Rare Earth Tridoping. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2015, 501, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Z.; Jia, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, P.; Liu, Y.; Cui, W.; Xu, J.; Xie, J. A One-Pot Hydrothermal Synthesis of Eu/BiVO4 Enhanced Visible-Light-Driven Photocatalyst for Degradation of Tetracycline. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2019, 20, 3053–3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Zhang, J. Effects of Europium Doping on the Photocatalytic Behavior of BiVO4. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 173, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, L.; Ding, J.; Sun, W.; Han, Z.; Jin, L. Core–Shell Heterostructured BiVO4/BiVO4:Eu3+ with Improved Photocatalytic Activity. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2017, 27, 1750–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Che, Y.; Niu, C.; Dang, M.; Dong, D. Effective Visible Light-Active Boron and Europium Co-Doped BiVO4 Synthesized by Sol-Gel Method for Photodegradion of Methyl Orange. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 262, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praxmair, J.; Creazzo, F.; Tang, D.; Zalesak, J.; Hörndl, J.; Luber, S.; Pokrant, S. Hydrothermally Synthesized BiVO4: The Role of KCl as Additive for Improved Photoelectrochemical and Photocatalytic Oxygen Evolution Activity. ChemElectroChem 2025, 12, 202500280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Han, J.; Lv, C.; Zhang, Y.; You, M.; Liu, T.; Li, S.; Zhu, T. Ag, B, and Eu Tri-Modified BiVO4 Photocatalysts with Enhanced Photocatalytic Performance under Visible-Light Irradiation. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 753, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, D.R.; Kshetri, Y.K.; Chaudhary, B.; Choi, J.-h.; Murali, G.; Kim, T.H. Enhancement of Upconversion Luminescence in Yb3+/Er3+-Doped BiVO4 through Calcination. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 37, 107258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenczewska, K.; Szymański, D.; Hreniak, D. Control of Optical Properties of Luminescent BiVO4:Tm3+ by Adjusting the Synthesis Parameters of Microwave-Assisted Hydrothermal Method. Mater. Res. Bull. 2022, 154, 111940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kuang, Y.; Liang, Z.; Sun, X. Microwave Chemistry, Recent Advancements, and Eco-Friendly Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Nanoarchitectures and Their Applications: A Review. Mater. Today Nano 2020, 11, 100076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, R.; Shibu, S.N.; Poelman, D.; Badyal, A.K.; Kunti, A.K.; Swart, H.C.; Menon, S.G. Recent Advances in Microwave Synthesis for Photoluminescence and Photocatalysis. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 32, 103890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, N.; Sahoo, S.; Kumar, R.; Singh, R.K. A Review of the Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Carbon Nanomaterials, Metal Oxides/Hydroxides and Their Composites for Energy Storage Applications. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 11679–11711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, Q.; Torabfam, M.; Fidan, T.; Kurt, H.; Yüce, M.; Clarke, N.; Bayazit, M.K. Microwave-Promoted Continuous Flow Systems in Nanoparticle Synthesis—A Perspective. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 9988–10015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaffouli, A. Eco-Friendly Nanomaterials Synthesized Greenly for Electrochemical Sensors and Biosensors. Microchem. J. 2025, 217, 115051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reda, A.T.; Park, Y.T. Sustainable Synthesis of Functional Nanomaterials: Renewable Resources, Energy-Efficient Methods, Environmental Impact and Circular Economy Approaches. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 516, 163894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatimah, S.; Ragadhita, R.; Al Husaeni, D.F.; Nandiyanto, A.B.D. How to Calculate Crystallite Size from X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Using Scherrer Method. ASEAN J. Sci. Eng. 2022, 2, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeli, S.T.; Podlogar, M.; Mitri, J.; Brankovi, G.; Brankovi, Z. High Efficiency Solar Light Photocatalytic Degradation of Mordant Blue 9 by Monoclinic BiVO4 Nanopowder. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2025, 333, 130341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Chen, F. Microwave-Assisted Preparation of Inorganic Nanostructures in Liquid Phase. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 6462–6555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longchin, P.; Pookmanee, P.; Satienperakul, S.; Sangsrichan, S.; Puntharod, R.; Kruefu, V.; Kangwansupamonkon, W.; Phanichphant, S. Characterization of Bismuth Vanadate (BiVO4) Nanoparticle Prepared by Solvothermal Method. Integr. Ferroelectr. 2016, 175, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolić, S.D.; Jovanović, D.J.; Štrbac, D.; Far, L.Đ.; Dramićanin, M.D. Improved Coloristic Properties and High NIR Reflectance of Environment-Friendly Yellow Pigments Based on Bismuth Vanadate. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 22731–22737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolić, S.D.; Jovanović, D.J.; Smits, K.; Babić, B.; Marinović-Cincović, M.; Porobić, S.; Dramićanin, M.D. A Comparative Study of Photocatalytically Active Nanocrystalline Tetragonal Zyrcon-Type and Monoclinic Scheelite-Type Bismuth Vanadate. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 17953–17961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Zhang, Z.; Han, W.; Cheng, X.; Li, X.; Xie, E. Efficient Hydrogen Evolution under Visible Light Irradiation over BiVO4 Quantum Dot Decorated Screw-like SnO2 Nanostructures. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 10338–10346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukowiak, A.; Chiasera, A.; Chiappini, A.; Righini, G.C.; Ferrari, M. Active Sol-Gel Materials, Fluorescence Spectra, and Lifetimes. In Handbook of Sol-Gel Science and Technology: Processing, Characterization and Applications; Klein, L., Aparicio, M., Jitianu, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1607–1649. ISBN 9783319321011. [Google Scholar]

- Duverger, C.; Ferrari, M.; Mazzoleni, C.; Montagna, M.; Pucker, G.; Turrell, S. Optical Spectroscopy of Pr3+ Ions in Sol-Gel Derived GeO2-SiO2 Planar Waveguides. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1999, 245, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Matos Rodrigues, M.H.; Borges, K.C.M.; de Fátima Gonçalves, R.; Carreno, N.L.V.; Alano, J.H.; Teodoro, M.D.; Godinho Junior, M. Exposed (040) Facets of BiVO4 Modified with Pr3+ and Eu3+: Photoluminescence Emission and Enhanced Photocatalytic Performance. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 934, 167925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczkan, M.; Kowalczyk, M.; Szostak, S.; Majchrowski, A.; Malinowski, M. Transition Intensity Analysis and Emission Properties of Eu3+: Bi2ZnOB2O6 Acentric Biaxial Single Crystal. Opt. Mater. 2020, 107, 110045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, D.L.; Vlad, M.O. Statistical Model for Stretched Exponential Relaxation with Backtransfer and Leakage. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 1997, 242, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, D.L. Stretched Exponential Relaxation and Optical Phenomena in Glasses. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. Sci. Technol. Sect. A Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 1996, 291, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatryb, G.; Klak, M.M. On the Choice of Proper Average Lifetime Formula for an Ensemble of Emitters Showing Non-Single Exponential Photoluminescence Decay. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2020, 32, 415902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thor, W.; Bünzli, J.-C.G.; Wong, K.-L.; Tanner, P.A. Shedding Light on Luminescence Lifetime Measurement and Associated Data Treatment. Adv. Photonics Res. 2025, 6, 2400081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Huang, Y.; Bai, J.; Seo, H.J. Manipulating Luminescence and Photocatalytic Activities of BiVO4 by Eu3+ Ions Incorporation. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 11767–11779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.; Li, W.; Wang, F.; Li, H.; Zhou, H. Substitution of Ce(III,IV) Ions for Bi in BiVO4 and Its Enhanced Impact on Visible Light-Driven Photocatalytic Activities. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 1870–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, S.; He, H.; Wu, Z.; Yu, C.; Fan, Q.; Peng, G.; Yang, K. An Interesting Eu,F-Codoped BiVO4 microsphere with Enhanced Photocatalytic Performance. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 694, 989–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regmi, C.; Kim, T.H.; Ray, S.K.; Yamaguchi, T.; Lee, S.W. Cobalt-Doped BiVO4 (Co-BiVO4) as a Visible-Light-Driven Photocatalyst for the Degradation of Malachite Green and Inactivation of Harmful Microorganisms in Wastewater. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2017, 43, 5203–5216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Qi, F.; Zhao, K.; Lv, D.; Ma, H.; Ma, C.; Padervand, M. Enhanced Degradation of Oxytetracycline Antibiotic Under Visible Light over Bi2WO6 Coupled with Carbon Quantum Dots Derived from Waste Biomass. Molecules 2024, 29, 5725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakhtiarnia, S.; Sheibani, S.; Aubry, E.; Sun, H.; Briois, P. Applied Surface Science One-Step Preparation of Ag-Incorporated BiVO4 Thin Films: Plasmon-Heterostructure Effect in Photocatalytic Activity Enhancement. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 580, 152253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabodiya, T.S.; Selvarasu, P.; Murugan, A.V. Tetragonal to Monoclinic Crystalline Phases Change of BiVO4 via Microwave-Hydrothermal Reaction: In Correlation with Visible-Light-Driven Photocatalytic Performance. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 5096–5110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obregón, S.; Lee, S.W.; Colón, G. Exalted Photocatalytic Activity of Tetragonal BiVO4 by Er3+ Doping through a Luminescence Cooperative Mechanism. Dalt. Trans. 2014, 43, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usai, S.; Obregón, S.; Becerro, A.I.; Colón, G. Monoclinic-Tetragonal Heterostructured BiVO4 by Yttrium Doping with Improved Photocatalytic Activity. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 24479–24484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wu, L.; Zhang, F.; Gao, L.; Geng, L.; Ge, J.; Tian, K.; Chai, H.; Niu, H.; Liu, Y.; et al. Doping with Rare Earth Elements and Loading Cocatalysts to Improve the Solar Water Splitting Performance of BiVO4. Inorganics 2023, 11, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Liu, X.; He, Q.; Zhou, W.; Yang, K.; Tao, L.; Li, F.; Yu, C. Preparation and Characterization of Sm3+/Tm3+ Co-Doped BiVO4 Micro-Squares and Their Photocatalytic Performance for CO2 Reduction. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2023, 144, 104737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.S.; Wu, M.H.; Wu, J.Y. Effects of Tb-Doped BiVO4 on Degradation of Methylene Blue. Sustainbility 2023, 15, 6994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, F.; Hua, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhao, X.; Liu, X.; Li, H. Microwave Synthesis and Photocatalytic Activity of Tb3+ Doped BiVO4 Microcrystals. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016, 483, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.; Bao, X.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, H.; Dai, Y.; Huang, B.; Wang, P. Construction of Y-Doped BiVO4 Photocatalysts for Efficient Two-Electron O2 Reduction to H2O2. Chem.-Eur. J. 2023, 29, e202203765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guardiano, M.G.; Ribeiro, L.K.; Gonzaga, I.M.D.; Mascaro, L.H. Effect of Cerium Precursors on Ce-Doped BiVO4 Nanoscale-Thick Films as Photoanodes: Implications for Water Splitting. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 19569–19578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghamri, J.; Baussart, H.; Le Bras, M.; Leroy, J.-M. Spectroscopic Study of BixEu1−xVO4 and BiyGd1−yVO Mixed Oxides. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 1989, 50, 1237–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blin, J.L.; Lorriaux-Rubbens, A.; Wallart, F.; Wignacourt, J.P. Synthesis and Structural Investigation of the Eu1−XBixVO4 Scheelite Phase: X-Ray Diffraction, Raman Scattering and Eu3+ Luminescence. J. Mater. Chem. 1996, 6, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, D.; Ma, C.; Cao, Y.; Qiu, J. Monophasic Zircon-Type Tetragonal Eu1−XBixVO4 Solid-Solution: Synthesis, Characterization, and Optical Properties. Mater. Res. Bull. 2014, 57, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.Y.; Gao, D.M.; Xu, Z.Z.; Gao, Y. Synthesis, Characterization, and Photocatalytic Activities of Eu3+-Doped BiVO4 Catalysts. Dig. J. Nanomater. Biostruct. 2025, 20, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.S.; Rai, S.B. Structural Analysis and Enhanced Photoluminescence via Host Sensitization from a Lanthanide Doped BiVO4 Nano-Phosphor. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2017, 110, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | τ Lifetime [ns] | 1/e Lifetime [ns] | Average Lifetime [µs] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bi0.97Eu0.03VO4 | 80 | 2868 | 60 |

| Bi0.94Eu0.06VO4 | <10 | 2675 | 100 |

| Bi0.91Eu0.09VO4 | <10 | 1280 | 30 |

| Bi0.88Eu0.12VO4 | <10 | 1638 | 36 |

| Wavelength [cm−1] | Description | Attribution |

|---|---|---|

| (a) 179 | External lattice mode | ms-BiVO4 distortions |

| (b) 197 | External lattice mode | ms-BiVO4 distortions |

| (c) 211 | External lattice mode | ms/tz-BiVO4 |

| (d) 247 | Bi–O stretching mode | tz-BiVO4 |

| (e) 327 | Symmetric bending mode of VO43 | ms/tz-BiVO4 |

| (f) 367 | Asymmetric bending mode of VO43 | ms/tz-BiVO4 |

| (g) 708 | Asymmetric stretching mode of V-O bond | ms-BiVO4 |

| (h) 778 | Antisymmetric stretching mode V-O bond | tz-BiVO4 |

| (i) 829 | Symmetric stretching mode of V-O | ms-BiVO4 |

| (j) 854 | Symmetric stretching mode V-O bond | tz-BiVO4 |

| Sample | (min−1) | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BiVO4 | 1.67 × 10−2 | 0.9678 | 1.00 |

| Bi0.97Eu0.03VO4 | 2.26 × 10−2 | 0.9684 | 1.35 |

| Bi0.94Eu0.06VO4 | 1.84 × 10−2 | 0.9511 | 1.10 |

| Bi0.91Eu0.09VO4 | 2.21 × 10−2 | 0.9863 | 1.33 |

| Bi0.88Eu0.12VO4 | 3.46 × 10−2 | 0.9508 | 2.07 |

| Sample/ Method of Synthesis | xEu3+ x = conc.(Eu3+) (mmol) | Crystalline Phase | Luminescent and Photocatalytic Properties | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eu3+-uniformly-doped BiVO4 NPs * | x = 0.0–0.5 | ms | 5D0 → 7F0,1,2,3,4 PL quenched; cutoff edge 530 nm and ~518 nm. | |

| x = 0.6–0.9 | Mixture ms-tz | Blue shift appears of the absorption edges. | [65] | |

| x = 0.9–1.0 | tz | 5D0 → 7F0,1,2,3,4 PL observed.Blue shift appears of the absorption edges. | ||

| Eu3+-surface- localized BiVO4 NPs | x = 0~0.6 | ms | Enhanced Eu3+-PL and improved photocatalysis. | [65] |

| BixEu1−xVO4 | 0 < x < 0.60 | tz | DRS: The broad bands attributed to charge transfer processes. The sharp peaks are ascribed to intra-configurational 4f–4f transitions of the Eu3+ ion in BixEu1−xVO4. | [80] |

| 0.94 < x < 1 | ms | |||

| EuVO4–BiVO4 | 0.35 < x < 0.70 | tz | - | [81] |

| 0.75 < x < 0.90 | Mixture ms-tz | - | ||

| Eu1−xBixVO4/P | x = 0.05 | tz | PL: The energy transfer and modification of the lifetime of the electron/hole pair formation of the Eu1−xBixVO4; higher photocatalytic degradation efficiency of MB compared to the undoped material. | [59] |

| Eu1−xBixVO4/MWHT | x = 0.05 | ms | ||

| Eu1−xBixVO4/P-HT | 0 < x < 1 | tz | Strong red emission under both near-UV and Vis excitation. | [82] |

| BixEu1−xVO4/SG | x = 0, 0.01, 0.03, 0.05, 0.07 and 0.10 | ms | DRS: Reduction in Eg from 2.43 to 2.38 eV with Eu3+ doping, indicating the formation of new low-energy-level transitions within the band gap; Eu3+ doping significantly improved photocatalytic efficiency. | [83] |

| BixEu1−xVO4/NPss/SC | x = 0.5, 1.0 and 1.5 | ms | PL: An intense red emission at 615 nm under excitation wavelength with 266 and 355 nm. | [84] |

| BixEu1−xVO4/MW | x = 0 | ms | PL: The Bi1−xEuxVO4 samples display dominant emission corresponding to 5D0 → 7F2 transition; the BiVO4 does not show any emission. Photocalysis: The Bi1−xEuxVO4 samples exhibit much higher photocatalytic activity in the degradation of RhB than undoped BiVO4. | This work |

| x = 0.3, 0.06, 0.09 | Mixture ms-tz | |||

| x = 0.12 | Dominant tz |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marinković, D.; Vasiljević, B.; Tot, N.; Barudžija, T.; Scaria, S.M.L.; Varas, S.; Dell’Anna, R.; Chiasera, A.; Fickl, B.; Bayer, B.C.; et al. Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Visible Light-Driven BiVO4 Nanoparticles: Effects of Eu3+ Ions on the Luminescent, Structural, and Photocatalytic Properties. Molecules 2025, 30, 4757. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244757

Marinković D, Vasiljević B, Tot N, Barudžija T, Scaria SML, Varas S, Dell’Anna R, Chiasera A, Fickl B, Bayer BC, et al. Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Visible Light-Driven BiVO4 Nanoparticles: Effects of Eu3+ Ions on the Luminescent, Structural, and Photocatalytic Properties. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4757. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244757

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarinković, Dragana, Bojana Vasiljević, Nataša Tot, Tanja Barudžija, Sudha Maria Lis Scaria, Stefano Varas, Rossana Dell’Anna, Alessandro Chiasera, Bernhard Fickl, Bernhard C. Bayer, and et al. 2025. "Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Visible Light-Driven BiVO4 Nanoparticles: Effects of Eu3+ Ions on the Luminescent, Structural, and Photocatalytic Properties" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4757. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244757

APA StyleMarinković, D., Vasiljević, B., Tot, N., Barudžija, T., Scaria, S. M. L., Varas, S., Dell’Anna, R., Chiasera, A., Fickl, B., Bayer, B. C., Righini, G. C., & Ferrari, M. (2025). Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Visible Light-Driven BiVO4 Nanoparticles: Effects of Eu3+ Ions on the Luminescent, Structural, and Photocatalytic Properties. Molecules, 30(24), 4757. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244757