On the Question of the Regio-, Stereoselectivity and the Molecular Mechanism of the (3+2) Cycloaddition Reaction Between (Z)-C-Phenyl-N-alkyl(phenyl)nitrones and (E)-3-(Methylsulfonyl)-propenoic Acid Derivatives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Analysis of the Reaction Mechanism

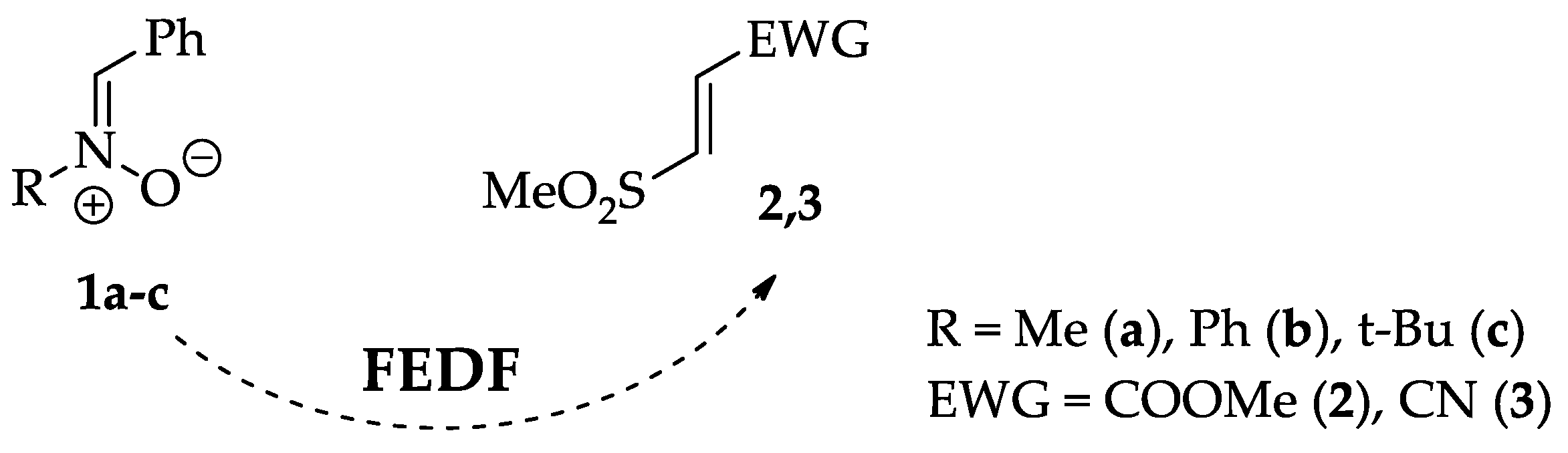

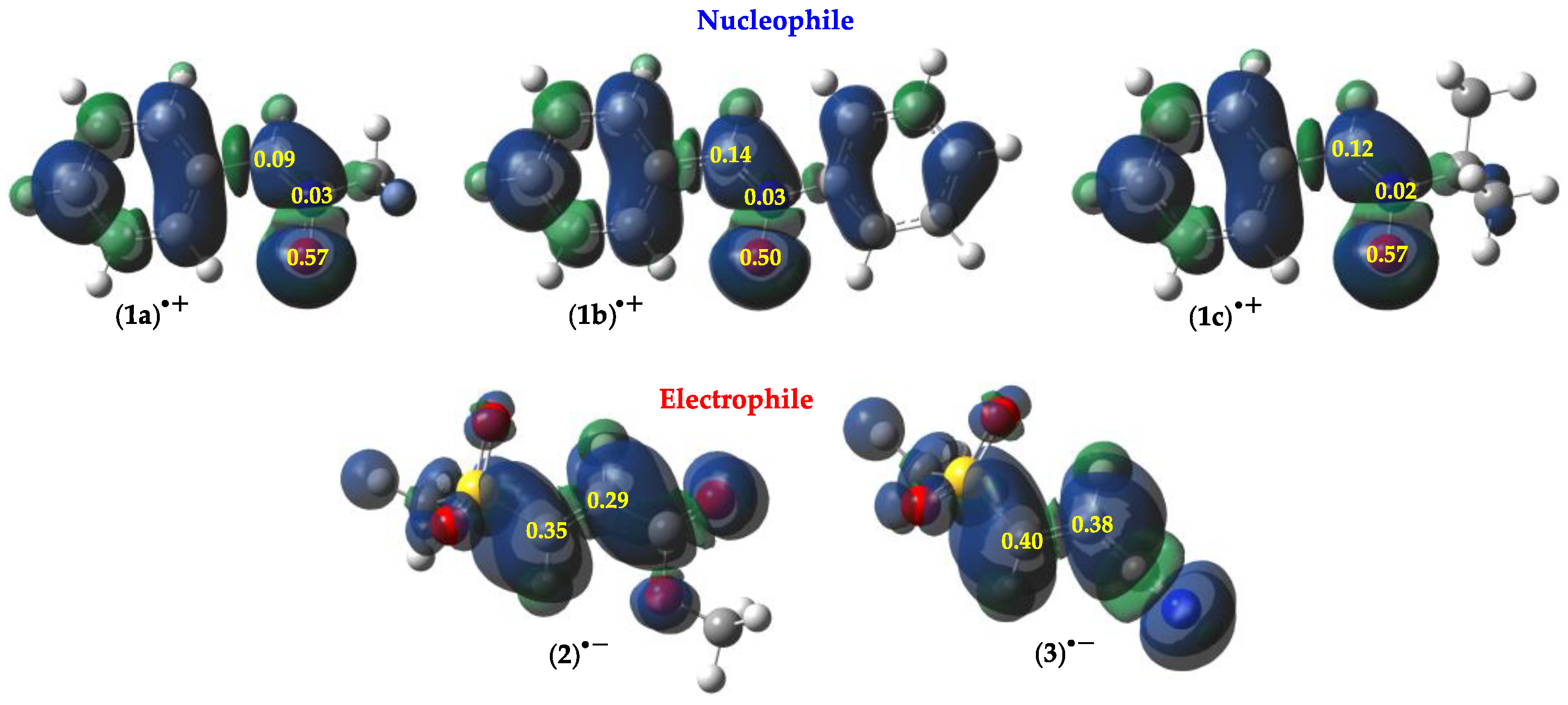

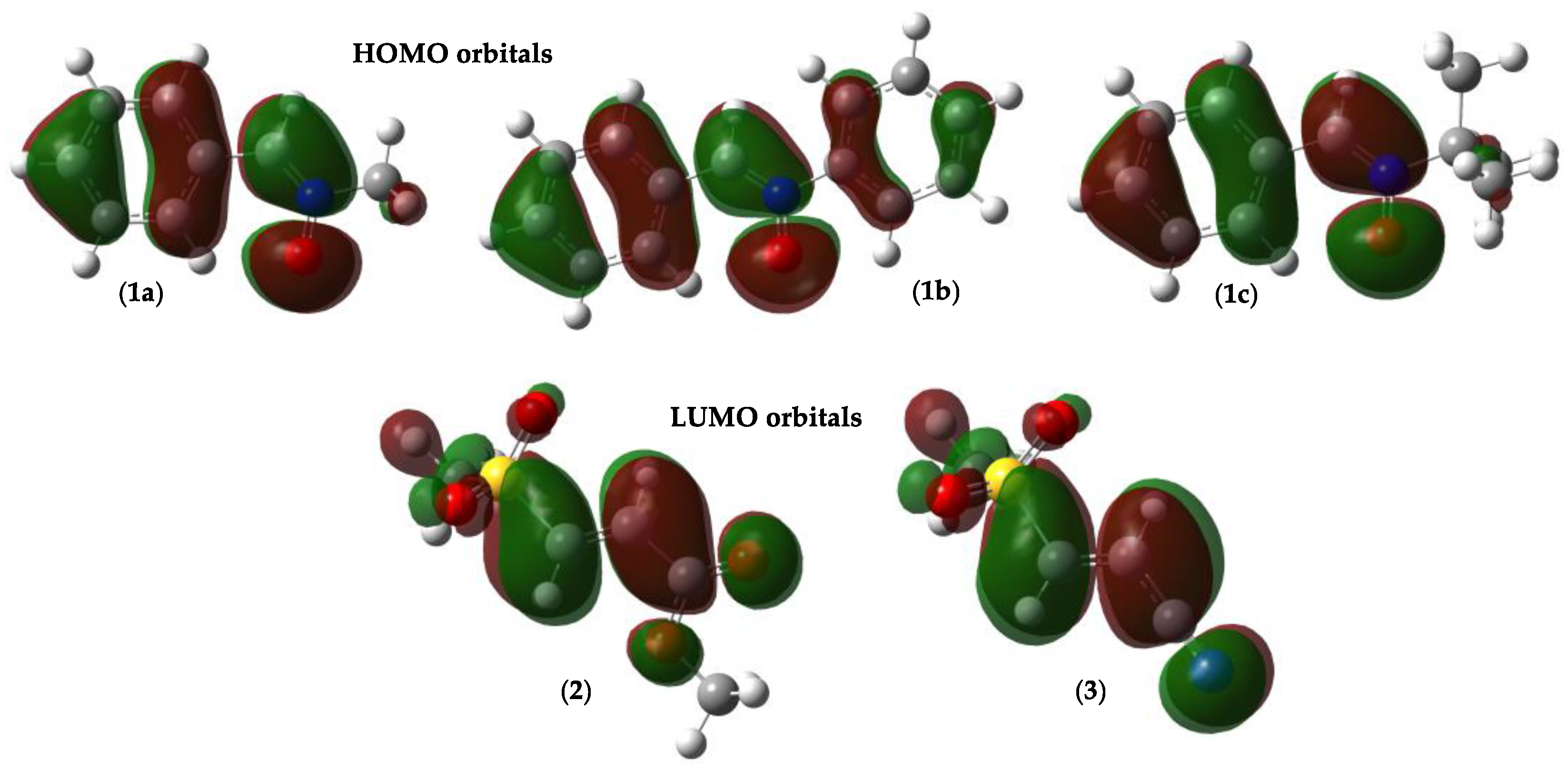

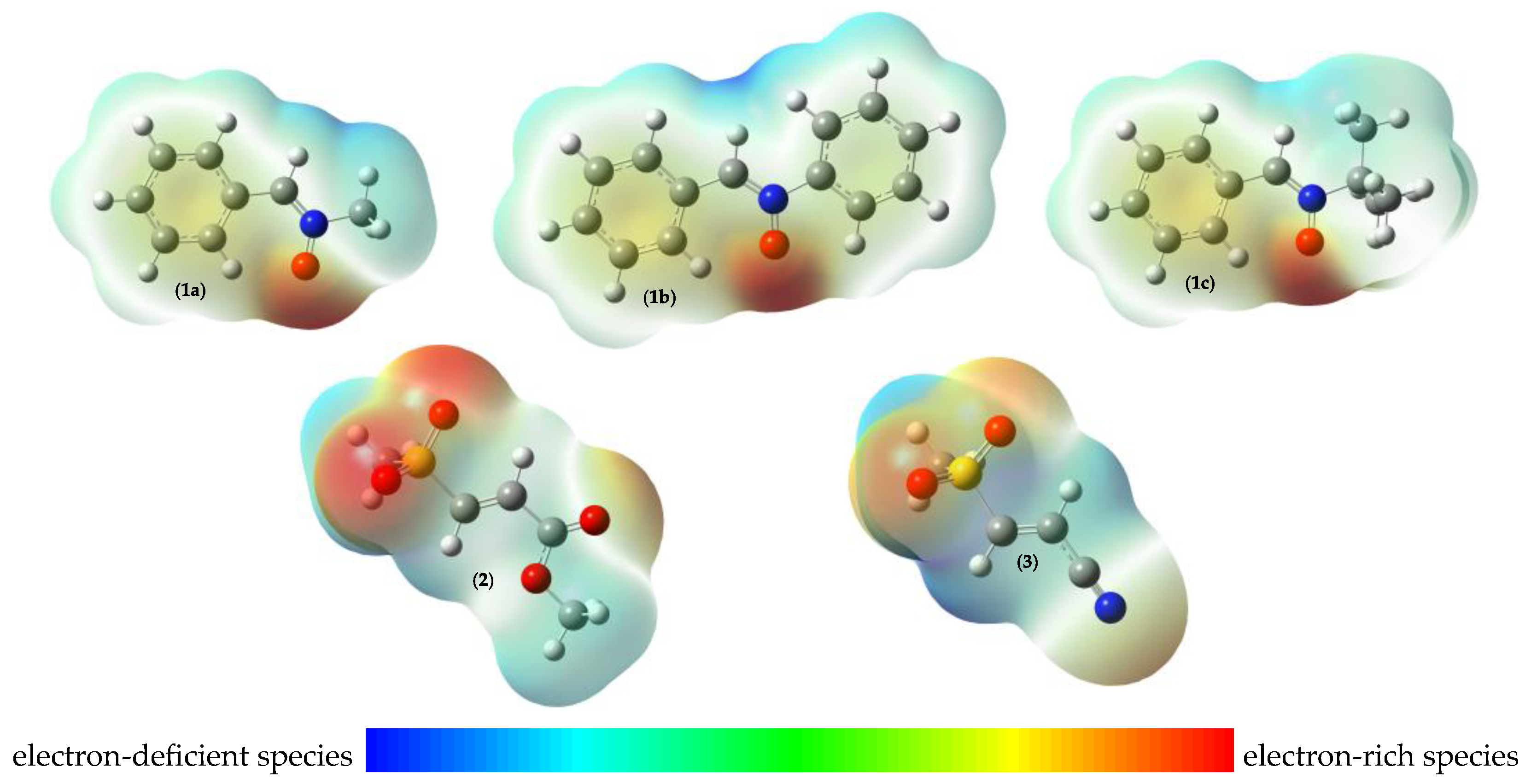

2.1.1. Global and Local Interactions Between Reactants

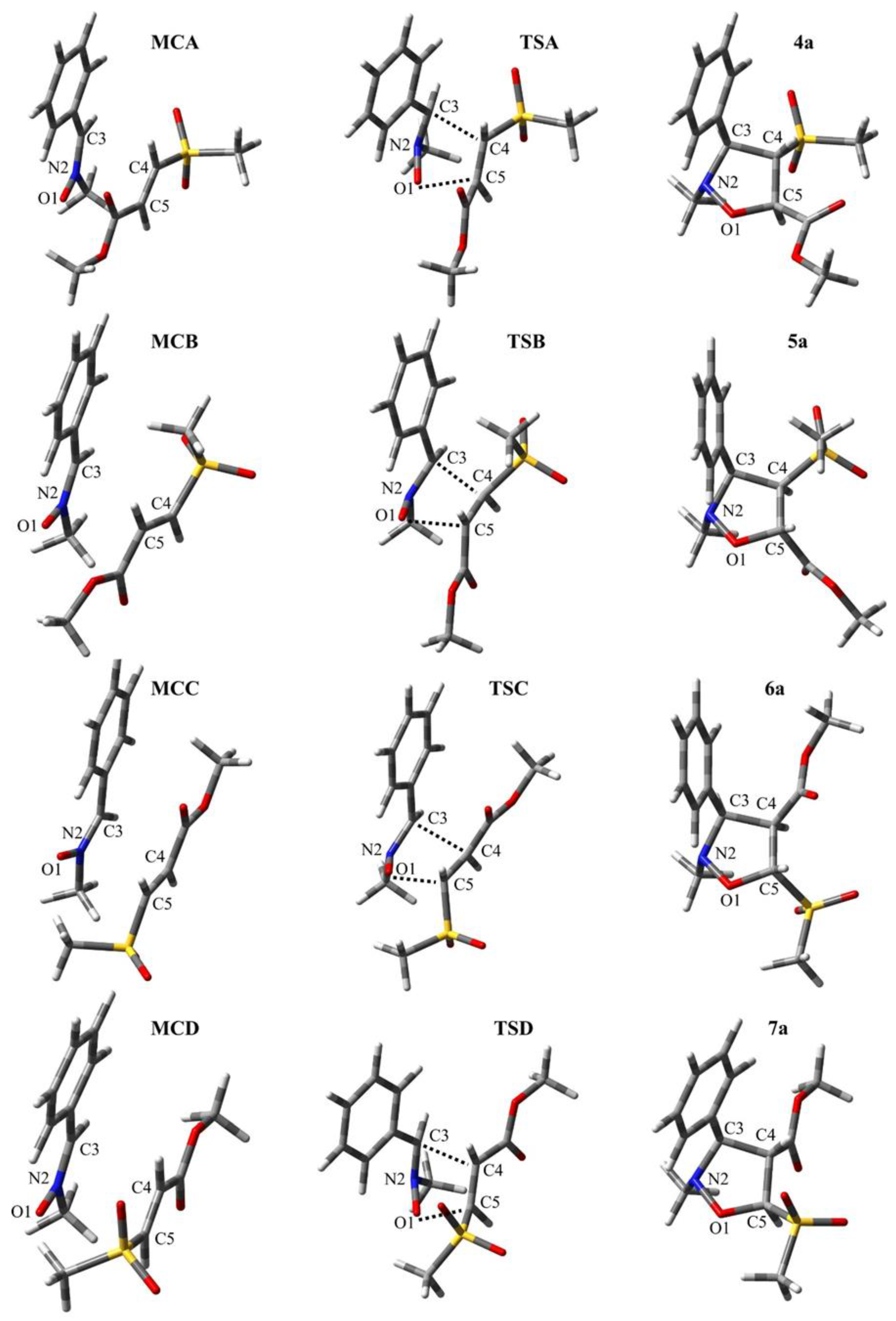

2.1.2. PES Exploration and Characterization of Critical Structures in the Studied CAs

2.2. Predicted Biological Activity of the Isoxazolidine Derivatives Formed in the Studied 32CAs

2.2.1. Computational Evaluation of ADME and Pharmacokinetic Profiles

2.2.2. PASS Computational Bioactivity Analysis

3. Materials and Methods

4. Conclusions and Future Perspective

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, X.; Hu, Q.; Tang, H.; Pan, X. Isoxazole/Isoxazoline Skeleton in the Structural Modification of Natural Products: A Review. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moncada-Basualto, M.; Saavedra-Olavarría, J.; Rivero-Jerez, P.S.; Rojas, C.; Maya, J.D.; Liempi, A.; Zúñiga-Bustos, M.; Olea-Azar, C.; Lapier, M.; Pérez, E.G.; et al. Assessment of the Activity of Nitroisoxazole Derivatives against Trypanosoma cruzi. Molecules 2024, 29, 2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, K.L.; Qi, B. Isoxazoline: A Privileged Scaffold for Agrochemical Discovery. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 14115–14128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.J.; Cao, X.Y.; Sun, N.B.; Min, L.J.; Duke, S.O.; Wu, H.K.; Zhang, L.Q.; Liu, X.H. Isoxazoline: An Emerging Scaffold in Pesticide Discovery. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 8678–8693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eneama, W.A.; Salman, H.H.; Mousa, M.N. Synthesis of a New Isoxazolidine and Evaluation Anticancer Activity against MCF 7 Breast Cancer Cell Line. Radiother. Oncol. 2023, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Łysakowska, M.; Głowacka, I.E.; Honkisz-Orzechowska, E.; Handzlik, J.; Piotrowska, D.G. New 3-(Dibenzyloxyphosphoryl)isoxazolidine Conjugates of N1-Benzylated Quinazoline-2,4-diones as Potential Cytotoxic Agents against Cancer Cell Lines. Molecules 2024, 29, 3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshamari, A.; Al-Qudah, M.; Hamadeh, F.; Al-Momani, L.; Abu-Orabi, S. Synthesis, Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activities of 2-Isoxazoline Derivatives. Molecules 2020, 25, 4271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebbar, N.K.; Taha, M.L.; Ellouz, M.; Essassi, E.M.; Zerzouf, A.; Karrouchi, K.; Ouzidan, Y.; Zakaria, M.; Mague, J.T. Synthesis, DFT Study and Antibacterial Activity of some Isoxazoline Derivatives Containing 1,4-benzothiazin-3-one Nucleus Obtained Using 1,3-dipolar Cycloaddition Reaction. Iran. J. Chem. Chem. Eng. 2020, 39, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiacchio, M.A.; Giofrè, S.V.; Romeo, R.; Romeo, G.; Chiacchio, U. Isoxazolidines as Biologically Active Compounds. Curr. Org. Synth. 2016, 13, 726–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzounthanasis, K.A.; Rizos, S.R.; Koumbis, A.E. A Convenient Synthesis of Novel Isoxazolidine and Isoxazole Isoquinolinones Fused Hybrids. Molecules 2024, 29, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederickson, M. Optically active isoxazolidines via asymmetric cycloaddition reactions of nitrones with alkenes: Applications in organic synthesis. Tetrahedron 1997, 53, 403–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthet, M.; Cheviet, T.; Dujardin, G.; Parrot, I.; Martinez, J. Isoxazolidine: A Privileged Scaffold for Organic and Medicinal Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 15235–15283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathiravan, M.K.; Salake, A.B.; Chothe, A.S.; Dudhe, P.B.; Watode, R.P.; Mukta, M.S.; Gadhwe, S. The Biology and Chemistry of Antifungal Agents: A Review. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012, 20, 5678–5698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirling, C.J. Leaving groups and nucleofugality in elimination and other organic reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 1979, 12, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kras, J.; Wróblewska, A.; Kącka-Zych, A. Unusual Regioselectivity in [3 + 2] Cycloaddition Reactions between (E)-3-Nitroacrylic Acid Derivatives and (Z)-C,N-Diphenylimine N-Oxide. Sci. Rad. 2023, 2, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasiński, R. A new mechanistic insight on β-lactam systems formation from 5-nitroisoxazolidines. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 50070–50072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padwa, A.; Koehler, K.F.; Rodriguez, A. New synthesis of β-lactams based on nitrone cycloaddition to nitroalkenes. J. Org. Chem. 1984, 49, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsarou, A.; Stathopoulos, P.; Tzvetanova, I.D.; Asimotou, C.-M.; Falagas, M.E. β-Lactam/β-Lactamase Inhibitor Combination Antibiotics Under Development. Pathogens 2025, 14, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; De Vos, A.L.; Khan, S.; St. John, M.; Hasan, T. Quantitative Insights Into β-Lactamase Inhibitor’s Contribution in the Treatment of Carbapenemase-Producing Organisms with β-Lactams. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 756410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Nolan, E.M. Enterobactin-mediated delivery of beta-lactam antibiotics enhances antibacterial activity against pathogenic Escherichia coli. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 9677–9691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasiński, R. Recent Progress in the Synthesis of Nitroisoxazoles and Their Hydrogenated Analogs via [3 + 2] Cycloaddition Reactions (Microreview). Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2023, 59, 730–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, S.; Das, A.; Das, T. 1,3-Dipolar cycloaddition of nitrones: Synthesis of multisubstituted, diverse range of heterocyclic compounds. New J. Chem. 2021, 45, 11420–11456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, D.S.C.; Crozier, R.F.; Davis, V.C. 1,3-Dipolar cycloaddition reactions of nitrones. Synthesis 1975, 1975, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, L.R. Molecular Electron Density Theory: A Modern View of Reactivity in Organic Chemistry. Molecules 2016, 21, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, L.R.; Emamian, S.R. Understanding the mechanisms of [3 + 2] cycloaddition reactions. The pseudoradical versus the zwitterionic mechanism. Tetrahedron 2014, 70, 1267–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trost, B.M. The atom economy—A search for synthetic efficiency. Science 1991, 254, 1471–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, M.I.L.; Cardoso, A.L.; Pinho e Melo, T.M.V.D. Diels–Alder Cycloaddition Reactions in Sustainable Media. Molecules 2022, 27, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasiński, R.; Żmigrodzka, M.; Dresler, E.; Kula, K. A full regio- and stereoselective synthesis of 4-nitroisoxazolidines via stepwise [3 + 2] cycloaddition reactions between (Z)-C-(9-anthryl)-N-arylnitrones and (E)-3,3,3-trichloro-1-nitroprop-1-ene: Comprehensive experimental and theoretical study. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2017, 54, 3314–3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryźlewicz, A.; Łapczuk-Krygier, A.; Kula, K.; Demchuk, O.M.; Dresler, E.; Jasiński, R. Regio- and Stereoselective Synthesis of Nitrofunctionalized 1,2-Oxazolidine Analogs of Nicotine. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2020, 56, 120–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kula, K.; Sadowski, M. Regio- and stereoselectivity of [3 + 2] cycloaddition reactions Between (Z)-C-(9-anthryl)-N-methylnitrone and analogues of trans-β-nitrostyrene in the light of MEDT computational study. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2023, 59, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, E.; Sieroń, L.; Albrecht, A. Enantioselective, Decarboxylative (3 + 2)-Cycloaddition of Azomethine Ylides and Chromone-3-Carboxylic Acids. Molecules 2022, 27, 6809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, T.; Maruoka, K. Recent Advances of Catalytic Asymmetric 1,3-Dipolar Cycloadditions. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 5366–5412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Cheng, F.; Kou, Y.-D.; Pang, S.; Shen, Y.-C.; Huang, Y.-Y.; Shibata, N. Catalytic Asymmetric 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition of β-Fluoroalkylated α,β-Unsaturated 2-Pyridylsulfones with Nitrones for Chiral Fluoroalkylated Isoxazolidines and γ-Amino Alcohols. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 1510–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmier, M.O.J.; Moussalli, N.; Chanet-Ray, J.; Chou, S. 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reactions of nitrones with unsaturated methylsulfones and substituted crotonic esters. J. Chem. Res. Synop. 1991, 9, 566–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woliński, P.; Kącka-Zych, A.; Wróblewska, A.; Wielgus, E.; Dolot, R.; Jasiński, R. Fully Selective Synthesis of Spirocyclic-1,2-oxazine N-Oxides via Non-Catalysed Hetero Diels-Alder Reactions with the Participation of Cyanofunctionalysed Conjugated Nitroalkenes. Molecules 2023, 28, 4586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woliński, P.; Kącka-Zych, A.; Demchuk, O.M.; Łapczuk-Krygier, A.; Mirosław, B.; Jasiński, R. Clean and molecularly programmable protocol for preparation of bis-heterobiarylic systems via a domino pseudocyclic reaction as a valuable alternative for TM-catalyzed cross-couplings. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 122086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawadzińska-Wrochniak, K.; Kula, K.; Ríos-Gutiérrez, M.; Gostyński, B.; Krawczyk, T.; Jasiński, R. A Comprehensive Study of the Synthesis, Spectral Characteristics, Quantum–Chemical Molecular Electron Density Theory, and In Silico Future Perspective of Novel CBr3-Functionalyzed Nitro-2-Isoxazolines Obtained via (3 + 2) Cycloaddition of (E)-3,3,3-Tribromo-1-Nitroprop-1-ene. Molecules 2025, 30, 2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisgen, R. 1,3-Dipolar cycloadditions. 76. Concerted nature of 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions and the question of diradical intermediates. J. Org. Chem. 1976, 41, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisgen, R. Kinetics and Mechanism of 1,3-Dipolar Cycloadditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1963, 2, 633–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisgen, R. 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions. Past and future. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1963, 2, 565–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisgen, R.; Pöchlauer, P.; Mlostoń, G.; Polborn, K. Reactions of Di(tert-butyl) diazomethane with Acceptor-Substituted Ethylenes. Helv. Chim. Acta 2007, 90, 983–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróblewska, A.; Sadowski, M.; Jasiński, R. Selectivity and molecular mechanism of the Au(III)-catalyzed [3 + 2] cycloaddition reaction between (Z)-C,N-diphenylnitrone and nitroethene in the light of the molecular electron density theory computational study. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2024, 60, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresler, E.; Woliński, P.; Wróblewska, A.; Jasiński, R. On the Question of Zwitterionic Intermediates in the [3 + 2] Cycloaddition Reactions between Aryl Azides and Ethyl Propiolate. Molecules 2023, 28, 8152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firestone, R.A. The Low Energy of Concert in Many Symmetry-Allowed Cycloadditions Supports a Stepwise-Diradical Mechanism. Int. J. Chem. Kinet. 2013, 45, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlostoń, G.; Urbaniak, K.; Linden, A.; Heimgartner, H. Selenophen-2-yl-substituted thiocarbonyl ylides—At the borderline of dipolar and biradical reactivity. Helv. Chim. Acta 2015, 98, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasiński, R. A new insight on the molecular mechanism of the reaction between (Z)-C,N-diphenylnitrone and 1,2-bismethylene-3,3,4,4,5,5-hexamethylcyclopentane. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2020, 94, 107461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryźlewicz, A.; Kącka-Zych, A.; Demchuk, O.M.; Mirosław, B.; Woliński, P.; Jasiński, R. Green synthesis of nitrocyclopropane-type precursors of inhibitors for the maturation of fruits and vegetables via domino reactions of diazoalkanes with 2-nitroprop-1-ene. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 292, 126079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryachi, K.; Mohammad-Salim, H.; Al-Sadoon, M.K.; Zeroual, A.; de Julián-Ortiz, J.V.; El Idrissi, M.; Tounsi, A. Quantum study of the [3 + 2] cycloaddition of nitrile oxide and carvone oxime: Insights into toxicity, pharmacokinetics, and mechanism. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2024, 60, 646–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitouna, A.O.; Syed, A.; Alfagham, A.T.; Mazoir, N.; de Julián-Ortiz, J.V.; Elgorban, A.M.; El Idrissi, M.; Wong, L.S.; Zeroual, A. Investigating the chemical reactivity and molecular docking of 2-diazo-3,3,3-trifluoro-1-nitropropane with phenyl methacrylate using computational methods. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2024, 60, 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdoul-Hakim, M.; Kenzy, C.; Subramaniam, M.; Zeroual, A.; Syed, A.; Bahkali, A.H.; Verma, M.; Wang, S.; Garmes, H. Elucidating Chemoselectivity and Unraveling the Mechanism of 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition between Diphenyl Nitrilimine and (Isoxazol-3-yl)methylbenzimidazole through Molecular Electron Density Theory. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2024, 60, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattaraj, P.K.; Roy, D.R. Update 1 of: Electrophilicity Index. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, PR46–PR74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, L.R. 1999–2024, a quarter century of the Parr’s electrophilicity ω index. Sci. Radices 2024, 3, 157–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, L.R.; Ríos-Gutiérrez, M.; Pérez, P. Electrophilicity w and Nucleophilicity N Scales for Cationic and Anionic Species. Sci. Radices 2025, 4, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, L.; Kerns, E. Drug-like Properties: Concepts, Structure Design and Methods from ADME to Toxicity Optimization; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Filimonov, D.A.; Lagunin, A.A.; Gloriozova, T.A.; Rudik, A.V.; Druzhilovskii, D.S.; Pogodin, P.V.; Poroikov, V.V. Prediction of the biological activity spectra of organic compounds using the PASS online web resource. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2014, 50, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowski, M.; Kula, K. Unexpected Course of Reaction Between (1E,3E)-1,4-Dinitro-1,3-butadiene and N-Methyl Azomethine Ylide—A Comprehensive Experimental and Quantum-Chemical Study. Molecules 2024, 29, 5066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kula, K.; Jasiński, R. On the Question of the Application Potential and the Molecular Mechanism of the Formation of 1,3-Diaryl-5-Nitropyrazoles from Trichloromethylated Diarylnitropyrazolines. Molecules 2025, 30, 4306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, R.G.; von Szentpaly, L.; Liu, S. Electrophilicity Index. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 1922–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, L.R.; Pérez, P. The Nucleophilicity N Index in Organic Chemistry. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011, 9, 7168–7175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurell, M.J.; Domingo, L.R.; Pérez, P.; Contreras, R. A Theoretical Study on the Regioselectivity Of 1,3-Dipolar Cycloadditions Using DFT-based Reactivity Indexes. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 11503–11509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryźlewicz, A.; Olszewska, A.; Zawadzińska, K.; Woliński, P.; Kula, K.; Kącka-Zych, A.; Łapczuk-Krygier, A.; Jasiński, R. On the Mechanism of the Synthesis of Nitrofunctionalised Δ2-Pyrazolines via [3 + 2] Cycloaddition Reactions between α-EWG-Activated Nitroethenes and Nitrylimine TAC Systems. Organics 2022, 3, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, L.R.; Aurell, M.J.; Pérez, P.; Contreras, R. Quantitative characterization of the global electrophilicity power of common diene/dienophile pairs in Diels–Alder reactions. Tetrahedron 2002, 58, 4417–4423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kula, K.; Jasiński, R. Synthesis of bis(het)aryl systems via domino reaction involving (2E,4E)-2,5-dinitrohexa-2,4-diene: DFT mechanistic considerations. Chem. Heterocycl. Comp. 2024, 60, 600–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, L.R.; Ríos-Gutiérrez, M. A Useful Classification of Organic Reactions Based on the Flux of the Electron Density. Sci. Radices 2023, 2, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, L.R.; Pérez, P.; Sáez, J.A. Understanding the Local Reactivity in Polar Organic Reactions Through Electrophilic and Nucleophilic Parr Functions. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 1486–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawadzińska, K.; Kula, K. Application of β-phosphorylated nitroethenes in [3 + 2] cycloaddition reactions involving benzonitrile N-oxide in the light of DFT computational study. Organics 2021, 2, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messaadia, S.; Nacereddine, A.K.; Djerourou, A. Exploring the factors controlling the mechanism and the high stereoselectivity of the polar [3 + 2] cycloaddition reaction of the N,N’-cyclic azomethine imine with 3-nitro-2-phenyl-2H-chromene. A Molecular Electron Density Theory study. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2023, 59, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kula, K.; Kącka-Zych, A.; Łapczuk-Krygier, A.; Jasiński, R. Analysis of the Possibility and Molecular Mechanism of Carbon Dioxide Consumption in the Diels-Alder Processes. Pure Appl. Chem. 2021, 93, 427–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kula, K.; Kącka-Zych, A.; Łapczuk-Krygier, A.; Wzorek, Z.; Nowak, A.K.; Jasiński, R. Experimental and Theoretical Mechanistic Study on the Thermal Decomposition of 3,3-Diphenyl-4-(Trichloromethyl)-5-Nitropyrazoline. Molecules 2021, 26, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chafaa, F.; Nacereddine, A.K. A molecular electron density theory study of mechanism and selectivity of the intramolecular [3 + 2] cycloaddition reaction of a nitrone–vinylphosphonate adduct. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2023, 59, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowski, M.; Kula, K.; Jasiński, R. On the question of the transformation of amino acids into aldimine N-oxides (nitrones): Molecular Electron Density Theory (MEDT) considerations. Monatsh. Chem. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresler, E.; Wróblewska, A.; Jasiński, R. Energetic Aspects and Molecular Mechanism of 3-Nitro-substituted 2-Isoxazolines Formation via Nitrile N-Oxide [3 + 2] Cycloaddition: An MEDT Computational Study. Molecules 2024, 29, 3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, A.; Acharjee, N. Unveiling the exclusive stereo and site selectivity in [3 + 2] cycloaddition reactions of a tricyclic strained alkene with nitrile oxides from the molecular electron density theory perspective. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2023, 59, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousfi, Y.; Benchouk, W.; Mekelleche, S.M. Prediction of the regioselectivity of the ruthenium-catalyzed [3 + 2] cycloadditions of benzyl azide with internal alkynes using conceptual DFT indices of reactivity. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2023, 59, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasiński, R. Nitroacetylene as dipolarophile in [2 + 3] cycloaddition reactions with allenyl-type three-atom components: DFT computational study. Monatshefte Für Chem. 2015, 146, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kula, K.; Dobosz, J.; Jasiński, R.; Kącka-Zych, A.; Łapczuk-Krygier, A.; Mirosław, B.; Demchuk, O.M. [3 + 2] Cycloaddition of diaryldiazomethanes with (E)-3,3,3-trichloro-1-nitroprop-1-ene: An experimental, theoretical and structural study. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1203, 127473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, H.; Ouabane, M.; Aissaoui, S.; Alaqarbeh, M.; Bouachrine, M. 1,2,4-triazole-chalcone and derivatives as antiproliferative agents: Quantum chemical studies, molecular docking, ADME-Tox and MD simulation. Curr. Chem. Lett. 2024, 14, 867–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohtat, B.; Siadati, S.A.; Khalilzadeh, M.A. Understanding the mechanism of the 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction between a thioformaldehyde S-oxide and cyclobutadiene: Competition between the stepwise and concerted routes. Prog. React. Kinet. Mec. 2019, 44, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kula, K.; Łapczuk, A.; Sadowski, M.; Kras, J.; Zawadzińska, K.; Demchuk, O.M.; Gaurav, G.K.; Wróblewska, A.; Jasiński, R. On the Question of the Formation of Nitro-Functionalized 2,4-Pyrazole Analogs on the Basis of Nitrylimine Molecular Systems and 3,3,3-Trichloro-1-Nitroprop-1-Ene. Molecules 2022, 27, 8409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kącka-Zych, A. The Molecular Mechanism of the Formation of Four-Membered Cyclic Nitronates and Their Retro (3 + 2) Cycloaddition: A DFT Mechanistic Study. Molecules 2021, 26, 4786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, C.W.; Gillies, J.Z.; Suenram, D.R.; Lovas, F.J.; Kraka, E.; Cremer, D. Van der Waals complexes in 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reactions: Ozone-ethylene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 2412–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, J.Z.; Gillies, C.W.; Lovas, F.J.; Matsumura, K.; Suenram, R.D.; Kraka, E.; Cremer, D. Van der Waals complexes of chemically reactive gases: Ozone-acetylene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 6408–6415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremer, D.; Kraka, E.; Crehuet, R.; Anglada, J.; Gräfenstein, J. The Ozone–Acetylene Reaction: Concerted Or Non-Concerted Reaction Mechanism? A Quantum Chemical Investigation. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2001, 347, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jodłowski, P.J.; Kurowski, G.; Dymek, K.; Oszajca, M.; Piskorz, W.; Hyjek, K.; Wach, A.; Pajdak, A.; Mazur, M.; Rainrer, D.N.; et al. From crystal phase mixture to pure metal-organic frameworks–Tuning pore and structure properties. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023, 95, 106377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronduda, H.; Zybert, M.; Patkowski, W.; Ostrowski, A.; Jodłowski, P.; Szymański, D.; Kępiński, L.; Raróg-Pilecka, W. A high performance barium-promoted cobalt catalyst supported on magnesium–lanthanum mixed oxide for ammonia synthesis. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 14218–14228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jodlowski, P.; Chlebda, D.; Piwowarczyk, E.; Chrzan, M.; Jędrzejczyk, R.; Sitarz, M.; Węgrzynowicz, A.; Kołodziej, A.; Łojewska, J. In situ and operando spectroscopic studies of sonically aided catalysts for biogas exhaust abatement. J. Mol. Struct. 2016, 1126, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaś, A.; Łapczuk, A. Computational Model of the Formation of Novel Nitronorbornene Analogs via Diels–Alder Process. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 2025, 138, 2671–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kącka-Zych, A.; Zeroual, A.; Syed, A.; Bahkali, A.H. Docking Survey, ADME, Toxicological Insights, and Mechanistic Exploration of the Diels-Alder Reaction between Hexachlorocyclopentadiene and Dichloroethylene. J. Comput. Chem. 2025, 46, 70092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fałowska, A.; Grzybowski, S.; Kapuściński, D.; Sambora, K.; Łapczuk, A. Modeling of the General Trends of Reactivity and Regioselectivity in Cyclopentadiene–Nitroalkene Diels–Alder Reactions. Molecules 2025, 30, 2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih, S.A.M.; Basheer, H.A.; de Julián-Ortiz, J.V.; Mohammad-Salim, H.A. Unveiling the Stereoselectivity and Regioselectivity of the [3 + 2] Cycloaddition Reaction between N-methyl-C-4-methylphenyl-nitrone and 2-Propynamide from a MEDT Perspective. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad-Salim, H.A.; Acharjee, N.; Abdallah, H. Insights into the mechanism and regioselectivity of the [3 + 2] cycloaddition reactions of cyclic nitrone to nitrile functions with a molecular electron density theory perspective. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2021, 140, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, L.R.; Chamorro, E.; Pérez, P. Understanding the mechanism of non-polar Diels-Alder reactions. A comparative ELF analysis of concerted and stepwise diradical mechanisms. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2010, 8, 5495–5504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; You, J.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Wu, W.; Liang, Y. Synthesis of New Isoxazolidine Derivatives Utilizing the Functionality of N-Carbonylpyrazol-Linked Isoxazolidines. Molecules 2024, 29, 3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moi, D.; Vittorio, S.; Angeli, A.; Balboni, G.; Supuran, C.T.; Onnis, V. Investigation on Hydrazonobenzenesulfonamides as Human Carbonic Anhydrase I, II, IX and XII Inhibitors. Molecules 2023, 28, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łapczuk, A. Zwitterionic Pathway in the Diels–Alder Reaction: Solvent and Substituent Effects from ωB97XD/6-311G(d) Calculations. Molecules 2025, 30, 4710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhawday, F.; Alminderej, F.; Ghannay, S.; Hammami, B.; Albadri, A.E.A.E.; Kadri, A.; Aouadi, K. In Silico Design, Synthesis, and Evaluation of Novel Enantiopure Isoxazolidines as Promising Dual Inhibitors of α-Amylase and α-Glucosidase. Molecules 2024, 29, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alminderej, F.; Ghannay, S.; Elsamani, M.O.; Alhawday, F.; Albadri, A.E.A.E.; Elbehairi, S.E.I.; Alfaifi, M.Y.; Kadri, A.; Aouadi, K. In Vitro and In Silico Evaluation of Antiproliferative Activity of New Isoxazolidine Derivatives Targeting EGFR: Design, Synthesis, Cell Cycle Analysis, and Apoptotic Inducers. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karcev, D.D.; Efremova, M.M.; Molchanov, A.P.; Rostovskii, N.V.; Kryukova, M.A.; Bunev, A.S.; Khochenkov, D.A. Selective and Reversible 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition of 2-(2-Oxoindoline-3-ylidene)acetates with Nitrones in the Synthesis of Functionalized Spiroisoxazolidines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi Kumar, K.R.; Mallesha, H.; Rangappa, K.S. Synthesis of Novel Isoxazolidine Derivatives and Their Antifungal and Antibacterial Properties. Arch. Pharm. 2003, 336, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasiński, R. Recent progress in the synthesis of nitropyrazoles and their hydrogenated analogs via non-catalysed [3+2] cycloaddition reactions of conjugated nitroalkenes. Chem. Heterocyclic Compd. 2025, 61, 286–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SwissADME. Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics. Available online: http://www.swissadme.ch/ (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Lipinski, C.A.; Lombardo, F.; Dominy, B.W.; Feeney, P.J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001, 46, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghose, A.K.; Viswanadhan, V.N.; Wendoloski, J.J. A knowledge-based approach in designing combinatorial or medicinal chemistry libraries for drug discovery. 1. A qualitative and quantitative characterization of known drug databases. J. Comb. Chem. 1999, 1, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veber, D.F.; Johnson, S.R.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Smith, B.R.; Ward, K.W.; Kopple, K.D. Molecular properties that influence the oral bioavailability of drug candidates. J. Med. Chem. 2002, 45, 2615–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egan, W.J.; Merz, K.M.; Baldwin, J.J. Prediction of drug absorption using multivariate statistics. J. Med. Chem. 2000, 43, 3867–3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muegge, I.; Heald, S.L.; Brittelli, D. Simple selection criteria for drug-like chemical matter. J. Med. Chem. 2001, 44, 1841–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Way2Drug, PASS Online. Available online: http://www.way2drug.com/passonline/ (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Fourches, D.; Muratov, E.; Tropsha, A. Trust, but verify: On the importance of chemical structure curation in cheminformatics and QSAR modeling research. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2010, 50, 1189–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosc, N.; Atkinson, F.; Felix, E.; Gaulton, A.; Hersey, A.; Leach, A.R. Large scale comparison of QSAR and conformal prediction methods and their applications in drug discovery. J. Cheminform. 2019, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, T.; Balderston, D.E.; Chahal, M.K.; Hilton, K.L.F.; Hind, C.K.; Keers, O.B.; Lilley, R.J.; Manwani, C.; Overton, A.; Popoola, P.I.A.; et al. Tools to Enable the Study and Translation of Supramolecular Amphiphiles. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 52, 6892–6917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: A Free Web Tool to Evaluate Pharmacokinetics, Drug-Likeness and Medicinal Chemistry Friendliness of Small Molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulsat, J.; López-Nieto, B.; Estrada-Tejedor, R.; Borrell, J.I. Evaluation of Free Online ADMET Tools for Academic or Small Biotech Environments. Molecules 2023, 28, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumontri, S.; Eiamart, W.; Tadtong, S.; Samee, W. Utilizing ADMET Analysis and Molecular Docking to Elucidate the Neuroprotective Mechanisms of a Cannabis-Containing Herbal Remedy (Suk-Saiyasna) in Inhibiting Acetylcholinesterase. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ertl, P.; Rohde, B.; Selzer, P. Fast Calculation of Molecular Polar Surface Area as a Sum of Fragment-Based Contributions and Its Application to the Prediction of Drug Transport Properties. J. Med. Chem. 2000, 43, 3714–3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauri, A.; Bertola, M. Alvascience: A New Software Suite for the QSAR Workflow Applied to the Blood–Brain Barrier Permeability. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Mercado, S.; Enríquez, C.; Valderrama, J.A.; Pino-Rios, R.; Ruiz-Vásquez, L.; Ruiz Mesia, L.; Vargas-Arana, G.; Buc Calderon, P.; Benites, J. Exploring the Antibacterial and Antiparasitic Activity of Phenylaminonaphthoquinones—Green Synthesis, Biological Evaluation and Computational Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekman, D. Exploring QSAR Fundamentals and Applications in Chemistry and Biology, Volume 1. Hydrophobic, Electronic and Steric Constants. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 10678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, J.S. ESOL: Estimating Aqueous Solubility Directly from Molecular Structure. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2004, 44, 1000–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, J.; Camilleri, P.; Brown, M.B.; Hutt, A.J.; Kirton, S.B. In Silico Prediction of Aqueous Solubility Using Simple QSPR Models: The Importance of Phenol and Phenol-like Moieties. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2012, 52, 2950–2957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnott, J.A.; Planey, S.L. The influence of lipophilicity in drug discovery and design. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2012, 7, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savjani, K.T.; Gajjar, A.K.; Savjani, J.K. Drug solubility: Importance and enhancement techniques. ISRN Pharm. 2012, 2012, 195727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannhold, R.; Poda, G.I.; Ostermann, C.; Tetko, I.V. Calculation of molecular lipophilicity: State-of-the-art and comparison of log P methods on more than 96,000 compounds. J. Pharm. Sci. 2009, 98, 861–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.; Yang, D.; Fan, X.; Zhang, M.; Li, Y.; Gu, X.; Yang, M. The Roles and Mechanisms of lncRNAs in Liver Fibrosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicze, M.; Borówka, M.; Dec, A.; Niemiec, A.; Bułdak, Ł.; Okopień, B. The Current and Promising Oral Delivery Methods for Protein- and Peptide-Based Drugs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Kwon, S.H.; Zhou, X.; Fuller, C.; Wang, X.; Vadgama, J.; Wu, Y. Overcoming Challenges in Small-Molecule Drug Bioavailability: A Review of Key Factors and Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, T.; Demizieux, L.; Troy-Fioramonti, S.; Buch, C.; Leemput, J.; Belloir, C.; Pais de Barros, J.-P.; Jourdan, T.; Passilly-Degrace, P.; Fioramonti, X.; et al. Chemical Synthesis, Pharmacokinetic Properties and Biological Effects of JM-00266, a Putative Non-Brain Penetrant Cannabinoid Receptor 1 Inverse Agonist. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filimonov, D.A.; Rudik, A.V.; Dmitriev, A.V.; Poroikov, V.V. Computer-Aided Estimation of Biological Activity Profiles of Drug-Like Compounds Taking into Account Their Metabolism in Human Body. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kula, K.; Kuś, E. In Silico Study About Substituent Effects, Electronic Properties, and the Biological Potential of 1,3-Butadiene Analogues. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowski, M.; Synkiewicz-Musialska, B.; Kula, K. (1E,3E)-1,4-Dinitro-1,3-butadiene—Synthesis, Spectral Characteristics and Computational Study Based on MEDT, ADME and PASS Simulation. Molecules 2024, 29, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furge, L.L.; Guengerich, F.P. Cytochrome P450 Enzymes in Drug Metabolism and Chemical Toxicology: An Introduction. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Educ. 2006, 34, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guengerich, F.P. Cytochrome P450 and Chemical Toxicology. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2008, 21, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Stackman, R. The Role of Serotonin 5-HT 2A Receptors in Memory and Cognition. Front. Pharmacol. 2015, 6, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halford, J.C.; Harrold, J.A. 5-HT(2C) receptor agonists and the control of appetite. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2012, 209, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciranna, L.; Costa, L. Therapeutic Effects of Pharmacological Modulation of Serotonin Brain System in Human Patients and Animal Models of Fragile X Syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendic, S. Summary of information on human CYP enzymes: Human P450 metabolism data. Drug Metab. Rev. 2002, 34, 83–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16, Revision C.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, J.-D.; Head-Gordon, M. Long-range corrected hybrid density functionals with damped atom-atom dispersion corrections. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 10, 6615–6620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hehre, W.J.; Radom, L.; Schleyer, P.v.R.; Pople, J.A. Ab Initio Molecular Orbital Theory; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, R.; Binkley, J.S.; Seeger, R.; Pople, J.A. Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XX. A basis set for correlated wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 1980, 72, 650–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łapczuk-Krygier, A.; Kazimierczuk, K.; Pikies, J.; Ríos-Gutiérrez, M. A Comprehensive Experimental and Theoretical Study on the [{(η5-C5H5)2Zr[P(µ-PNEt2)2P(NEt2)2P]}]2O Crystalline System. Molecules 2021, 26, 7282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, M.; Farnia, S.M.F.; Tahghighi, A. The possibility of applying some heteroatom-decorated g-C3N4 heterocyclic nanosheets for delivering 5-aminosalicylic acid anti-inflammatory agent. Chem. Heterocycl. Comp. 2024, 60, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demchuk, O.M.; Jasiński, R.; Strzelecka, D.; Dziuba, K.; Kula, K.; Chrzanowski, J.; Krasowska, D. A clean and simple method for deprotection of phosphines from borane complexes. Pure Appl. Chem. 2018, 90, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kącka-Zych, A. Understanding of the stability of acyclic nitronic acids in the light of molecular electron density theory. J. Mol. Graph. 2024, 129, 108754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapuściński, D.; Łapczuk, A. Bicyclic 1, 2-oxazine 2-oxides as the discrete intermediates in the reactions between regioisomeric trimetylsilylcyclopentadienes and (2E)-2-nitro-3-phenylprop-2-enenitrile. Chem. Heterocycl. Comp. 2025, 61, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, L.R.; Ríos-Gutiérrez, M.; Pérez, P. Applications of the Conceptual Density Functional Theory Indices to Organic Chemistry Reactivity. Molecules 2016, 21, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, R.G.; Gadre, S.R.; Bartolotti, L.J. Local Density Functional Theory of Atoms and Molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1979, 76, 2522–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, L.R. A new C–C bond formation model based on the quantum chemical topology of electron density. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 32415–32428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro, E.; Pérez, P.; Domingo, L.R. On the nature of Parr functions to predict the most reactive sites along organic polar reactions. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2013, 582, 141–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattaraj, P.K.; Duley, S.; Domingo, L.R. Understanding local electrophilicity/nucleophilicity activation through a single reactivity difference index. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10, 2855–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegel, H.B. Optimization of equilibrium geometries and transition structures. J. Comput. Chem. 1982, 3, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegel, H.B. Geometry Optimization on Potential Energy Surfaces. In Modern Electronic Structure Theory; Yarkony, D.R., Ed.; World Scientific Publishing: Singapore, 1994; pp. 459–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukui, K. Formulation of the reaction coordinate. J. Phys. Chem. 1970, 74, 4161–4163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, C.; Schlegel, H.B. Reaction path following in mass-weighted internal coordinates. J. Phys. Chem. 1990, 94, 5523–5527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, C.; Schlegel, H.B. Improved algorithms for reaction path following: Higher order implicit algorithms. J. Chem. Phys. 1991, 95, 5853–5860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasi, J.; Persico, M. Molecular Interactions in Solution: An Overview of Methods Based on Continuous Distributions of the Solvent. Chem. Rev. 1994, 94, 2027–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossi, M.; Barone, V.; Cammi, R.; Tomasi, J. Ab initio study of solvated molecules: A new implementation of the polarizable continuum model. Chem. Phys. Chem. 1996, 225, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, V.; Cossi, M.; Tomasi, J. Geometry optimization of molecular structures in solution by the polarizable continuum model. J. Comput. Chem. 1998, 19, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, A.E.; Weinstock, R.B.; Weinhold, F. Natural population analysis. J. Chem. Phys. 1985, 83, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, A.E.; Curtiss, L.A.; Weinhold, F. Intermolecular interactions from a natural bond orbital, donor-acceptor viewpoint. Chem. Rev. 1988, 88, 899–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasiński, R. A stepwise, zwitterionic mechanism for the 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition between (Z)-C-4-methoxyphenyl-N-phenylnitrone and gem-chloronitroethene catalysed by 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium ionic liquid cations. Tetrahedron Lett. 2015, 56, 532–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresler, E.; Allnajar, R.; Jasiński, R. Sterical index: A novel, simple tool for the interpretation of organic reaction mechanisms. Sci. Radices 2023, 2, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennington, R.; Keith, T.A.; Millam, J.M. GaussView, Version 6.0; Semichem Inc.: Shawnee, KS, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| 1a | 1b | 1c | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HOMO energy | −7.67 | −7.60 | −7.64 | −10.83 | −10.23 |

| LUMO energy | 0.34 | 0.44 | −0.25 | −0.93 | −0.52 |

| Electronic chemical potential, μ | −3.67 | −3.58 | −3.95 | −5.88 | −5.38 |

| Chemical hardness, η | 8.01 | 8.05 | 7.39 | 9.90 | 9.72 |

| Global electrophilicity, ω | 0.84 | 0.80 | 1.05 | 1.75 | 1.49 |

| Global nucleophilicity, N | 3.73 | 3.79 | 3.75 | 0.57 | 1.16 |

| Reaction | Path | Transition | ΔH | ΔS | ΔG | ΔH | ΔS | ΔG | Transition | Path | Reaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a+2 | A | 1a+2→MCA | −11.9 | −40.9 | 0.3 | −11.3 | −39.1 | 0.4 | 1a+3→MCA | A | 1a+3 |

| 1a+2→TSA | 3.3 | −50.3 | 18.3 | 3.8 | −48.5 | 18.3 | 1a+3→TSA | ||||

| 1a+2→4a | −28.4 | −48.5 | −13.9 | −25.6 | −49.6 | −10.8 | 1a+3→8a | ||||

| B | 1a+2→MCB | −12.5 | −43.2 | 0.4 | −10.3 | −38.2 | 1.1 | 1a+3→MCB | B | ||

| 1a+2→TSB | 8.4 | −51.9 | 23.9 | 11.2 | −50.5 | 26.2 | 1a+3→TSB | ||||

| 1a+2→5a | −26.3 | −53.2 | −10.4 | −22.9 | −53.4 | −7.0 | 1a+3→9a | ||||

| C | 1a+2→MCC | −13.6 | −42.8 | −0.8 | −10.7 | −39.7 | 1.1 | 1a+3→MCC | C | ||

| 1a+2→TSC | 4.4 | −52.6 | 20.0 | 6.1 | −49.4 | 20.8 | 1a+3→TSC | ||||

| 1a+2→6a | −30.3 | −52.7 | −14.6 | −27.1 | −50.7 | −11.9 | 1a+3→10a | ||||

| D | 1a+2→MCD | −11.5 | −38.3 | −0.1 | −8.9 | −41.2 | 3.3 | 1a+3→MCD | D | ||

| 1a+2→TSD | 5.5 | −49.0 | 20.1 | 6.5 | −48.7 | 21.0 | 1a+3→TSD | ||||

| 1a+2→7a | −28.1 | −50.1 | −13.2 | −26.2 | −54.1 | −10.1 | 1a+3→11a | ||||

| 1b+2 | A | 1b+2→MCA | −13.1 | −32.0 | −3.6 | −11.6 | −33.1 | −2.0 | 1b+3→MCA | A | 1b+3 |

| 1b+2→TSA | 1.1 | −45.2 | 14.6 | 1.8 | −43.5 | 21.5 | 1b+3→TSA | ||||

| 1b+2→4b | −32.1 | −44.7 | −18.8 | −28.9 | −44.2 | −12.4 | 1b+3→8b | ||||

| B | 1b+2→MCB | −14.0 | −39.7 | −2.1 | −11.8 | −32.8 | −2.0 | 1b+3→MCB | B | ||

| 1b+2→TSB | 6.6 | −47.4 | 20.7 | 7.5 | −46.9 | 21.5 | 1b+3→TSB | ||||

| 1b+2→5b | −30.4 | −50.7 | −15.3 | −26.8 | −48.1 | −12.4 | 1b+3→9b | ||||

| C | 1b+2→MCC | −14.7 | −35.9 | −4.0 | −11.6 | −34.3 | −3.5 | 1b+3→MCC | C | ||

| 1b+2→TSC | 3.8 | −47.3 | 17.9 | 5.8 | −45.4 | 19.3 | 1b+3→TSC | ||||

| 1b+2→6b | −32.3 | −45.2 | −18.8 | −29.5 | −45.3 | −16.0 | 1b+3→10b | ||||

| D | 1b+2→MCD | −12.1 | −34.4 | −1.8 | −11.6 | −33.1 | −1.7 | 1b+3→MCD | D | ||

| 1b+2→TSD | 2.7 | −44.8 | 16.1 | 4.9 | −43.1 | 17.8 | 1b+3→TSD | ||||

| 1b+2→7b | −32.7 | −45.6 | −19.2 | −27.3 | −42.3 | −14.7 | 1b+3→11b | ||||

| 1c+2 | A | 1c+2→MCA | −8.1 | −42.3 | 4.5 | −11.8 | −40.5 | 0.3 | 1c+3→MCA | A | 1c+3 |

| 1c+2→TSA | 4.6 | −51.0 | 19.8 | 5.2 | −50.2 | 20.2 | 1c+3→TSA | ||||

| 1c+2→4c | −26.3 | −49.4 | −11.5 | −24.0 | −49.8 | −9.1 | 1c+3→8c | ||||

| B | 1c+2→MCB | −12.7 | −42.1 | −0.1 | −8.8 | −35.3 | 1.7 | 1c+3→MCB | B | ||

| 1c+2→TSB | 8.3 | −54.7 | 24.6 | 11.0 | −52.4 | 26.6 | 1c+3→TSB | ||||

| 1c+2→5c | −25.2 | −54.3 | −9.0 | −22.1 | −52.2 | −6.5 | 1c+3→9c | ||||

| C | 1c+2→MCC | −13.3 | −42.8 | −0.6 | −11.9 | −40.6 | 0.2 | 1c+3→MCC | C | ||

| 1c+2→TSC | 6.0 | −55.5 | 22.5 | 7.5 | −52.9 | 23.2 | 1c+3→TSC | ||||

| 1c+2→6c | −28.1 | −52.2 | −12.5 | −25.2 | −50.3 | −10.2 | 1c+3→10c | ||||

| D | 1c+2→MCD | −13.9 | −47.4 | 0.3 | −9.7 | −33.7 | 0.4 | 1c+3→MCD | D | ||

| 1c+2→TSD | 6.0 | −49.9 | 20.9 | 6.5 | −50.0 | 21.4 | 1c+3→TSD | ||||

| 1c+2→7c | −29.0 | −50.5 | −13.9 | −24.9 | −46.4 | −11.0 | 1c+3→11c |

| Reaction | Path | Structure | Interatomic Distances [Å] | l | Δl | GEDT * | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O1–N2 | N2–C3 | C3–C4 | C4–C5 | C5–O1 | C3–C4 | C5–O1 | [e] | ||||

| 1a+2 | A | MCA | 1.274 | 1.303 | 3.203 | 1.325 | 2.788 | ||||

| TSA | 1.288 | 1.344 | 2.119 | 1.392 | 2.008 | 0.640 | 0.591 | 0.049 | 0.147 | ||

| 4a | 1.419 | 1.461 | 1.558 | 1.530 | 1.425 | ||||||

| B | MCB | 1.274 | 1.303 | 3.410 | 1.324 | 3.019 | |||||

| TSB | 1.279 | 1.348 | 2.078 | 1.390 | 2.122 | 0.659 | 0.517 | 0.142 | 0.146 | ||

| 5a | 1.432 | 1.462 | 1.550 | 1.526 | 1.431 | ||||||

| C | MCC | 1.273 | 1.303 | 3.532 | 1.322 | 3.332 | |||||

| TSC | 1.306 | 1.332 | 2.291 | 1.393 | 1.867 | 0.536 | 0.673 | 0.137 | 0.141 | ||

| 6a | 1.437 | 1.461 | 1.565 | 1.520 | 1.407 | ||||||

| D | MCD | 1.271 | 1.304 | 3.256 | 1.323 | 3.108 | |||||

| TSD | 1.299 | 1.337 | 2.211 | 1.392 | 1.916 | 0.588 | 0.646 | 0.058 | 0.117 | ||

| 7a | 1.425 | 1.460 | 1.566 | 1.524 | 1.414 | ||||||

| 1b+2 | A | MCA | 1.276 | 1.307 | 3.173 | 1.323 | 3.176 | ||||

| TSA | 1.286 | 1.348 | 2.123 | 1.387 | 2.052 | 0.637 | 0.564 | 0.073 | 0.125 | ||

| 4b | 1.404 | 1.464 | 1.558 | 1.526 | 1.429 | ||||||

| B | MCB | 1.275 | 1.307 | 3.431 | 1.324 | 3.031 | |||||

| TSB | 1.272 | 1.356 | 2.035 | 1.386 | 2.244 | 0.683 | 0.419 | 0.264 | 0.128 | ||

| 5b | 1.431 | 1.469 | 1.545 | 1.526 | 1.419 | ||||||

| C | MCC | 1.281 | 1.305 | 4.293 | 1.322 | 4.788 | |||||

| TSC | 1.307 | 1.335 | 2.278 | 1.392 | 1.892 | 0.539 | 0.659 | 0.120 | 0.127 | ||

| 6b | 1.425 | 1.461 | 1.559 | 1.515 | 1.411 | ||||||

| D | MCD | 1.277 | 1.307 | 4.025 | 1.322 | 3.294 | |||||

| TSD | 1.294 | 1.344 | 2.171 | 1.385 | 1.996 | 0.605 | 0.595 | 0.010 | 0.097 | ||

| 7b | 1.414 | 1.462 | 1.556 | 1.523 | 1.420 | ||||||

| 1c+2 | A | MCA | 1.274 | 1.302 | 3.223 | 1.324 | 2.973 | ||||

| TSCA | 1.283 | 1.347 | 2.060 | 1.395 | 2.027 | 0.671 | 0.572 | 0.099 | 0.138 | ||

| 4c | 1.423 | 1.467 | 1.550 | 1.523 | 1.420 | ||||||

| B | MCB | 1.274 | 1.301 | 3.730 | 1.323 | 2.982 | |||||

| TSB | 1.263 | 1.355 | 1.996 | 1.391 | 2.245 | 0.707 | 0.406 | 0.301 | 0.161 | ||

| 5c | 1.449 | 1.466 | 1.544 | 1.525 | 1.409 | ||||||

| C | MCC | 1.278 | 1.300 | 4.070 | 1.322 | 4.779 | |||||

| TSC | 1.305 | 1.331 | 2.273 | 1.394 | 1.856 | 0.544 | 0.674 | 0.130 | 0.129 | ||

| 6c | 1.444 | 1.460 | 1.561 | 1.515 | 1.400 | ||||||

| D | MCD | 1.273 | 1.302 | 3.329 | 1.323 | 3.454 | |||||

| TSD | 1.299 | 1.336 | 2.170 | 1.395 | 1.900 | 0.599 | 0.623 | 0.024 | 0.094 | ||

| 7c | 1.453 | 1.477 | 1.549 | 1.514 | 1.379 | ||||||

| 1a+3 | A | MCA | 1.274 | 1.304 | 3.229 | 1.329 | 2.760 | ||||

| TSA | 1.284 | 1.346 | 2.097 | 1.401 | 2.003 | 0.658 | 0.595 | 0.063 | 0.195 | ||

| 8a | 1.419 | 1.461 | 1.562 | 1.538 | 1.426 | ||||||

| B | MCB | 1.283 | 1.299 | 5.174 | 1.329 | 3.092 | |||||

| TSB | 1.278 | 1.347 | 2.110 | 1.396 | 2.099 | 0.646 | 0.528 | 0.118 | 0.199 | ||

| 9a | 1.425 | 1.462 | 1.559 | 1.541 | 1.426 | ||||||

| C | MCC | 1.275 | 1.303 | 3.312 | 1.329 | 2.979 | |||||

| TSC | 1.314 | 1.328 | 2.359 | 1.406 | 1.790 | 0.494 | 0.725 | 0.231 | 0.201 | ||

| 10a | 1.438 | 1.457 | 1.566 | 1.534 | 1.404 | ||||||

| D | MCD | 1.277 | 1.302 | 4.682 | 1.325 | 3.211 | |||||

| TSD | 1.301 | 1.335 | 2.222 | 1.398 | 1.899 | 0.586 | 0.654 | 0.068 | 0.049 | ||

| 11a | 1.425 | 1.456 | 1.571 | 1.540 | 1.411 | ||||||

| 1b+3 | A | MCA | 1.281 | 1.305 | 5.586 | 1.326 | 2.975 | ||||

| TSA | 1.281 | 1.351 | 2.095 | 1.395 | 2.059 | 0.658 | 0.559 | 0.099 | 0.175 | ||

| 8b | 1.405 | 1.464 | 1.561 | 1.534 | 1.428 | ||||||

| B | MCB | 1.278 | 1.303 | 4.754 | 1.328 | 3.063 | |||||

| TSB | 1.270 | 1.355 | 2.059 | 1.392 | 2.226 | 0.673 | 0.448 | 0.225 | 0.179 | ||

| 9b | 1.416 | 1.464 | 1.551 | 1.534 | 1.434 | ||||||

| C | MCC | 1.284 | 1.305 | 3.879 | 1.327 | 3.150 | |||||

| TSC | 1.314 | 1.330 | 2.347 | 1.404 | 1.812 | 0.496 | 0.713 | 0.217 | 0.189 | ||

| 10b | 1.432 | 1.462 | 1.561 | 1.526 | 1.408 | ||||||

| D | MCD | 1.281 | 1.305 | 4.778 | 1.326 | 3.457 | |||||

| TSD | 1.301 | 1.340 | 2.256 | 1.396 | 1.882 | 0.556 | 0.659 | 0.103 | 0.213 | ||

| 11b | 1.413 | 1.476 | 1.563 | 1.528 | 1.404 | ||||||

| 1c+3 | A | MCA | 1.275 | 1.303 | 3.241 | 1.328 | 2.856 | ||||

| TSCA | 1.278 | 1.351 | 2.034 | 1.403 | 2.038 | 0.688 | 0.560 | 0.128 | 0.194 | ||

| 8c | 1.427 | 1.472 | 1.550 | 1.532 | 1.415 | ||||||

| B | MCB | 1.278 | 1.301 | 5.492 | 1.327 | 2.898 | |||||

| TSB | 1.268 | 1.351 | 2.062 | 1.396 | 2.156 | 0.672 | 0.485 | 0.187 | 0.200 | ||

| 9c | 1.428 | 1.460 | 1.554 | 1.535 | 1.423 | ||||||

| C | MCC | 1.278 | 1.299 | 4.411 | 1.326 | 4.861 | |||||

| TSC | 1.316 | 1.325 | 2.367 | 1.407 | 1.764 | 0.483 | 0.736 | 0.253 | 0.194 | ||

| 10c | 1.449 | 1.460 | 1.561 | 1.526 | 1.396 | ||||||

| D | MCD | 1.279 | 1.300 | 5.092 | 1.326 | 3.339 | |||||

| TSD | 1.303 | 1.334 | 2.192 | 1.402 | 1.875 | 0.603 | 0.661 | 0.058 | 0.163 | ||

| 11c | 1.429 | 1.466 | 1.569 | 1.535 | 1.400 | ||||||

| 4,5a | 6,7a | 4,5b | 6,7b | 4,5c | 6,7c | 8,9a | 10,11a | 8,9b | 10,11b | 8,9c | 10,11c | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physchem. properties | MW [g/mol] | 299 | 299 | 361 | 361 | 341 | 341 | 266 | 266 | 328 | 328 | 308 | 308 |

| #heavy atoms | 20 | 20 | 25 | 25 | 23 | 23 | 18 | 18 | 23 | 23 | 21 | 21 | |

| #arom. heavy atoms | 6 | 6 | 12 | 12 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 12 | 12 | 6 | 6 | |

| #rotatable bonds | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| #H-bond acceptors | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | |

| #H-bond donors | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Molar refractivity | 76.28 | 76.28 | 96.52 | 96.52 | 90.74 | 90.74 | 69.94 | 69.94 | 90.18 | 90.18 | 84.40 | 84.40 | |

| TPSA [Å2] | 81.29 | 81.29 | 81.29 | 81.29 | 81.29 | 81.29 | 78.78 | 78.78 | 78.78 | 78.78 | 78.78 | 78.78 | |

| Lipophilicity | Log Po/w (iLOGP) | 1.91 | 2.21 | 2.20 | 2.58 | 2.38 | 2.62 | 1.37 | 1.62 | 1.75 | 2.13 | 1.85 | 2.04 |

| Log Po/w (XLOGP3) | 1.01 | 1.01 | 2.79 | 2.79 | 1.99 | 1.99 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 2.66 | 2.66 | 1.86 | 1.86 | |

| Log Po/w (WLOGP) | 0.94 | 1.14 | 2.51 | 2.72 | 2.10 | 2.31 | 1.29 | 1.49 | 2.86 | 2.97 | 2.45 | 2.66 | |

| Log Po/w (MLOGP) | 0.82 | 0.82 | 2.10 | 2.10 | 1.59 | 1.59 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 1.87 | 1.87 | 1.34 | 1.34 | |

| Log Po/w (SILICOS-IT) | 0.13 | 0.13 | 1.22 | 1.22 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 1.28 | 1.28 | 0.99 | 0.99 | |

| Consensus Log Po/w | 0.96 | 1.06 | 2.17 | 2.28 | 1.80 | 1.89 | 0.85 | 0.94 | 2.08 | 2.20 | 1.70 | 1.78 | |

| Water solubility | Log S (ESOL) | −2.29 | −2.29 | −3.86 | −3.86 | −3.07 | −3.07 | −2.16 | −2.16 | −3.74 | −3.74 | −2.94 | −2.94 |

| solubility [mg/mL] | 1.53 | 1.53 | 0.049 | 0.049 | 0.288 | 0.288 | 1.84 | 1.84 | 0.059 | 0.059 | 0.356 | 0.356 | |

| Log S (Ali) | −2.31 | −2.31 | −4.15 | −4.15 | −3.32 | −3.32 | −2.12 | −2.12 | −3.97 | −3.97 | −3.14 | −3.14 | |

| solubility [mg/mL] | 1.48 | 1.48 | 0.025 | 0.025 | 0.162 | 0.162 | 2.03 | 2.03 | 0.035 | 0.035 | 0.226 | 0.226 | |

| Log S (SILICOS-IT) | −2.38 | −2.38 | −4.47 | −4.47 | −3.18 | −3.18 | −2.40 | −2.40 | −4.50 | −4.50 | −3.21 | −3.21 | |

| solubility [mg/mL] | 1.25 | 1.25 | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.227 | 0.227 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.191 | 0.191 | |

| Pharmacokinetics | CYP1A2 inhibitor | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| CYP2C19 inhibitor | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | |

| CYP2C9 inhibitor | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

| CYP2D6 inhibitor | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

| CYP3A4 inhibitor | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | |

| IG absorption | High | High | High | High | High | High | High | High | High | High | High | High | |

| BBB permeant | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Druglikeness | Lipinski et al. (Pfizer) [102] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Ghose et al. (Amgen) [103] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Veber et al. (GSK) [104] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Egan et al. (Pharmacia) [105] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Muegge et al. (Bayer) [106] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 4,5a | 6,7a | 4,5b | 6,7b | 4,5c | 6,7c | 8,9a | 10,11a | 8,9b | 10,11b | 8,9c | 10,11c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP2H substrate | 0.788 | 0.882 | 0.718 | 0.853 | 0.76 | 0.870 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 5 Hydroxytryptamine 2C antagonist | - | - | 0.759 | - | - | - | - | - | 0.877 | - | - | - |

| 5 Hydroxytryptamine 2A antagonist | - | - | 0.724 | - | - | - | - | - | 0.820 | - | - | - |

| 5 Hydroxytryptamine 2 antagonist | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.733 | - | - | - |

| 5 Hydroxytryptamine release stimulant | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.719 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ząbkowska, M.; Kula, K.; Diychuk, V.; Jasiński, R. On the Question of the Regio-, Stereoselectivity and the Molecular Mechanism of the (3+2) Cycloaddition Reaction Between (Z)-C-Phenyl-N-alkyl(phenyl)nitrones and (E)-3-(Methylsulfonyl)-propenoic Acid Derivatives. Molecules 2025, 30, 4738. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244738

Ząbkowska M, Kula K, Diychuk V, Jasiński R. On the Question of the Regio-, Stereoselectivity and the Molecular Mechanism of the (3+2) Cycloaddition Reaction Between (Z)-C-Phenyl-N-alkyl(phenyl)nitrones and (E)-3-(Methylsulfonyl)-propenoic Acid Derivatives. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4738. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244738

Chicago/Turabian StyleZąbkowska, Martyna, Karolina Kula, Volodymyr Diychuk, and Radomir Jasiński. 2025. "On the Question of the Regio-, Stereoselectivity and the Molecular Mechanism of the (3+2) Cycloaddition Reaction Between (Z)-C-Phenyl-N-alkyl(phenyl)nitrones and (E)-3-(Methylsulfonyl)-propenoic Acid Derivatives" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4738. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244738

APA StyleZąbkowska, M., Kula, K., Diychuk, V., & Jasiński, R. (2025). On the Question of the Regio-, Stereoselectivity and the Molecular Mechanism of the (3+2) Cycloaddition Reaction Between (Z)-C-Phenyl-N-alkyl(phenyl)nitrones and (E)-3-(Methylsulfonyl)-propenoic Acid Derivatives. Molecules, 30(24), 4738. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244738