Vinyl Chloride Degradation Using Ozone-Based Advanced Oxidation Processes: Bridging Groundwater Treatment and Machine Learning for Smarter Solutions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Effect of Ozonation and Ozone-Based AOPs on Vinyl Chloride Degradation

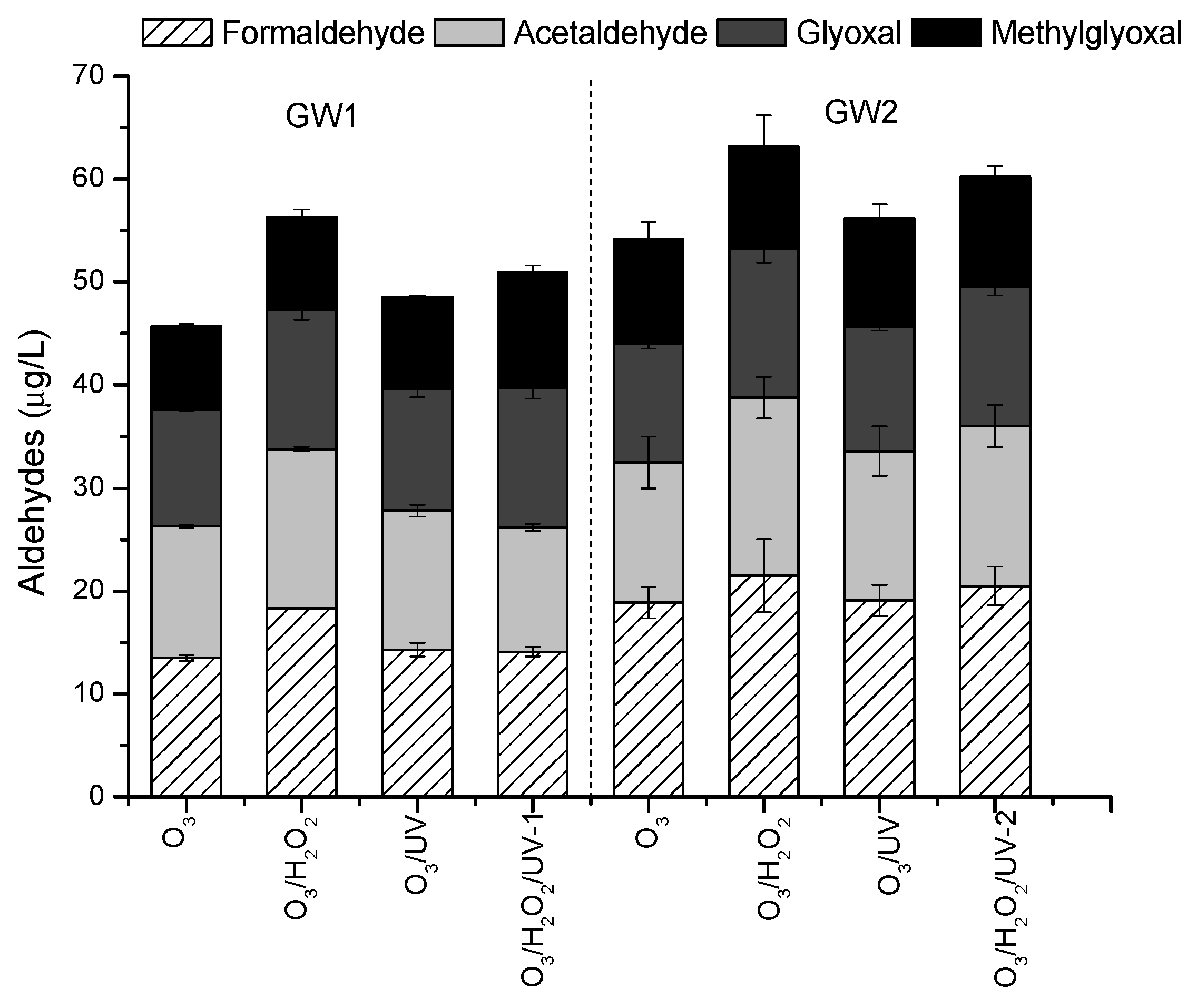

2.2. Effect of Ozonation and Ozone-Based AOPs on Oxidation By-Products Formation

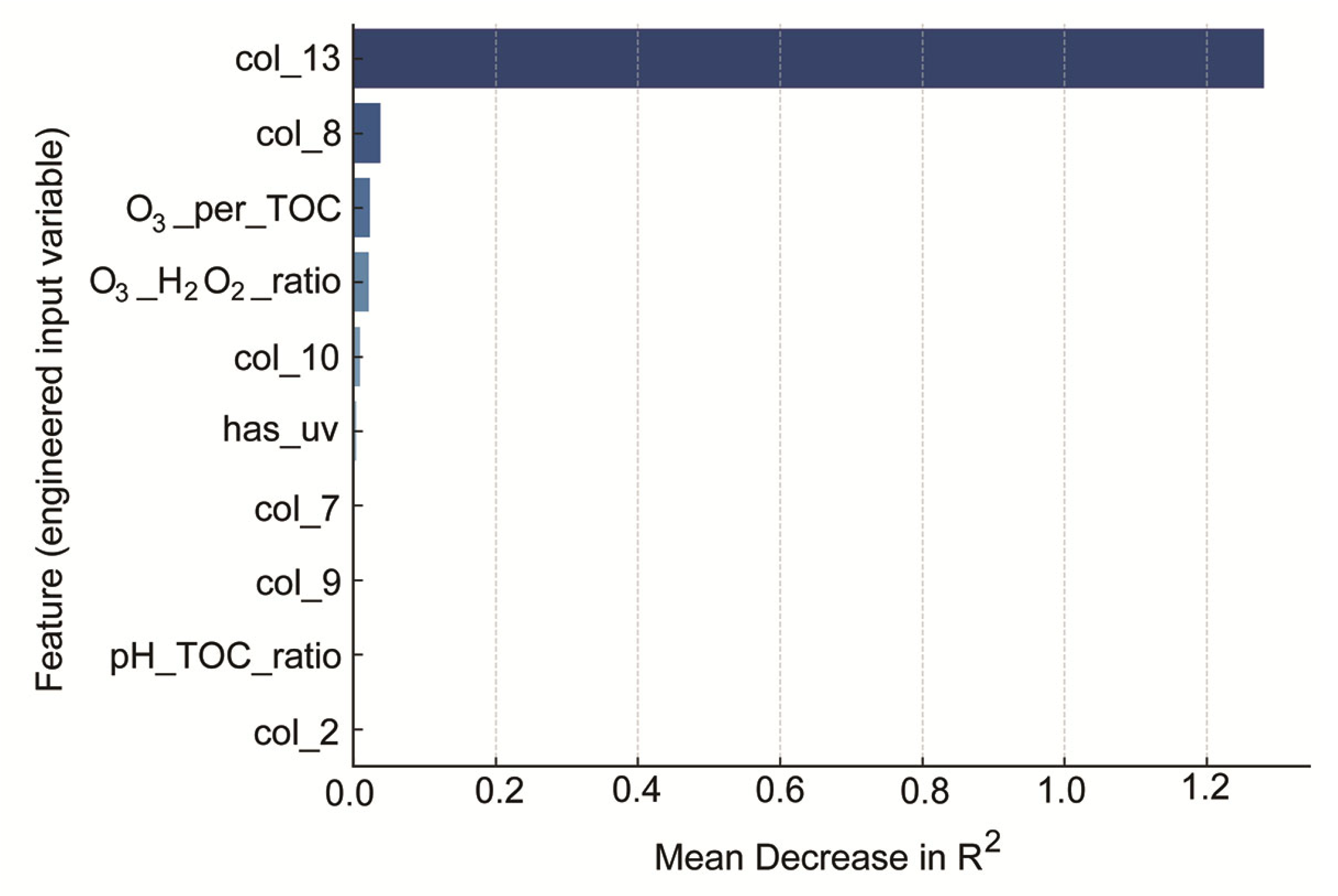

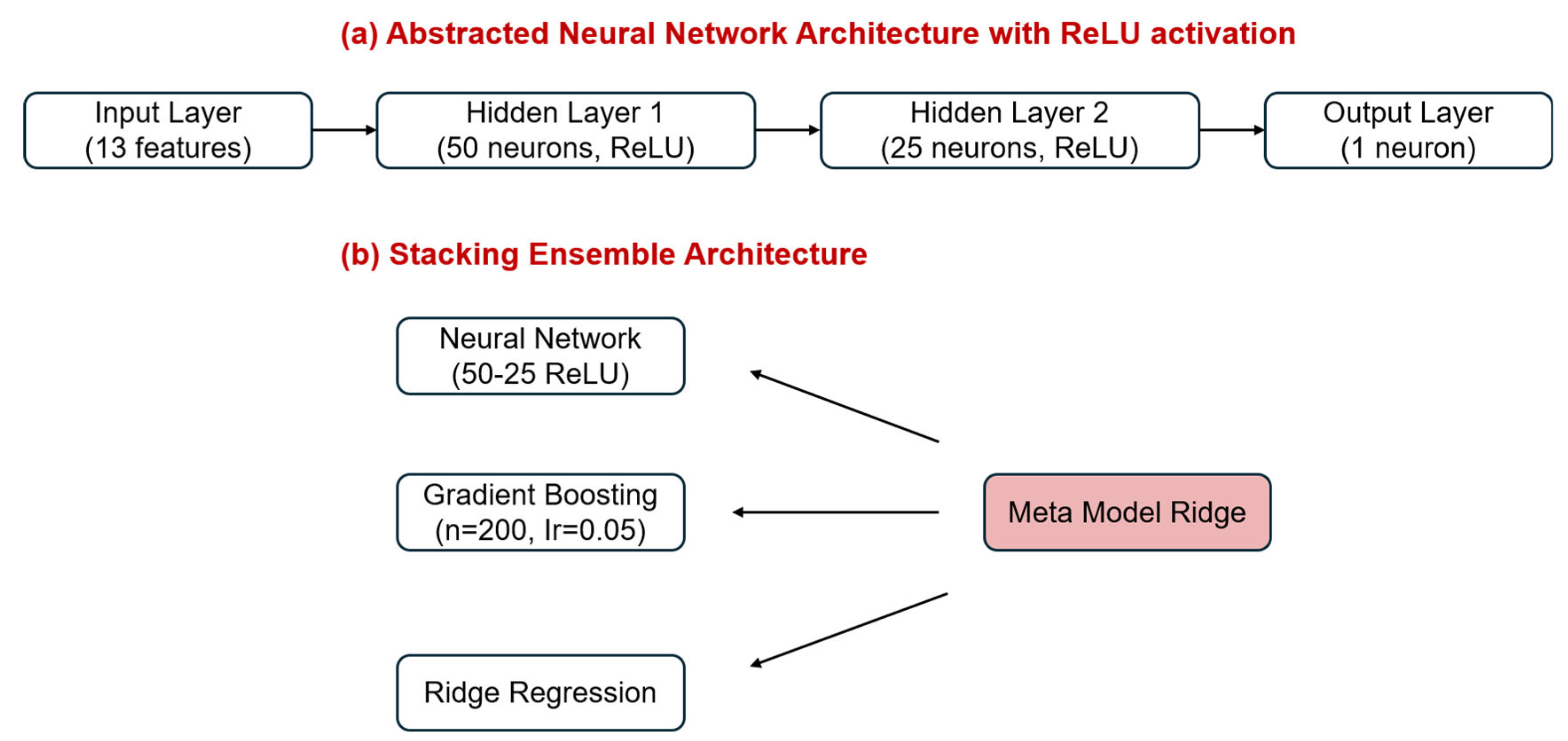

2.3. Artificial Intelligence Models for Predicting Vinyl Chloride Degradation: Performance, Interpretability, and Error Analysis

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals and Reagents

3.2. Water Samples

3.3. Ozonation and Ozone-Based AOPs

3.4. Analytical Methods

3.5. Artificial Intelligence Modelling of Vinyl Chloride Degradation

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, R.; Ding, L.; Cai, B.; Zhao, P.; Ding, M.; Wang, C.; Qu, C. Recent developments in electrochemical reduction for remediation of chlorinated hydrocarbons contaminated groundwater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Jiang, Q.; Zhu, H.; Chen, Y.; Xu, L.; Ma, H.; Pu, S. Electrochemical reduction for chlorinated hydrocarbons contaminated groundwater remediation: Mechanisms, challenges, and perspectives. Water Res. 2025, 274, 123149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkoli, A.; Agerholm, N.; Andersen, H.R.; Kaarsholm, K.M.S. Synergy between ozonation and GAC filtration for chlorinated ethenes-contaminated groundwater treatment. J. Water Process Eng. 2021, 44, 102356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.-W.; Chang, S.-C. Potential Microbial Indicators for Better Bioremediation of an Aquifer Contaminated with Vinyl Chloride or 1,1-Dichloroethene. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2020, 231, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Li, H.; Wei, Z.; Liang, C.; Dong, X.; Lin, D.; Chen, M. Enhanced removal of cis-1,2-dichloroethene and vinyl chloride in groundwater using ball-milled sulfur- and biochar-modified zero-valent iron: From the laboratory to the field. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 336, 122424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y. Analyzing degradation pathways in the conversion of trichloroethylene to vinyl chloride: The role of S/Fe ratios. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 196, 106887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive (Eu) 2020/2184 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2020 on the Quality of Water Intended for Human Consumption (Recast). EN Official Journal of the European Union. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2020/2184/oj/eng (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- von Sonntag, C.; von Gunten, U. Chemistry of Ozone in Water and Wastewater Treatment: From Basic Principles to Applications; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Das, P.P.; Dhara, S.; Samanta, N.S.; Purkait, M.K. Advancements on ozonation process for wastewater treatment: A comprehensive review. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2024, 202, 109852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar Jazić, J.; Gross, A.; Glaser, B.; Agbaba, J.; Simetić, T.; Nikić, J.; Maletić, S. Boosting advanced oxidation processes by biochar-based catalysts to mitigate pesticides and their metabolites in water treatment: A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 114260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Zhan, H.; Kuo, C.-H. Advanced Oxidation and Degradation of Vinyl Chloride in Water. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2002, 25, 433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Gunten, U. Ozonation of drinking water: Part I. Oxidation kinetics and product formation. Water Res. 2003, 37, 1443–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutschke, M.; Schnabel, T.; Schütz, F.; Springer, C. Degradation of chlorinated volatile organic compounds from contaminated ground water using a carrier-bound TiO2/UV/O3-system. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 304, 114236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ault, B.S. Matrix isolation investigation of the wavelength-dependent photochemical reaction of ozone with vinyl chloride. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1212, 128123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krystynik, P.; Masin, P.; Kluson, P. Pilot scale application of UV-C/H2O2 for removal of chlorinated ethenes from contaminated groundwater. J. Water Supply Res. T 2018, 67, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, N.; Topudurti, K.; Welshans, G.; Foster, R. A Field Demonstration of the UV/Oxidation Technology to Treat Ground Water Contaminated with VOCs. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 1990, 40, 540–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagpal, M.; Siddique, M.A.; Sharma, K.; Sharma, N.; Mittal, A. Optimizing wastewater treatment through artificial intelligence: Recent advances and future prospects. Water Sci. Technol. 2024, 90, 731–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, S.; Karanfil, T. Applications of artificial intelligence (AI) in drinking water treatment processes: Possibilities. Chemosphere 2024, 356, 141958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, S.K.; Karthika, S.; Mahanty, B.; Meher, S.K.; Zafar, M.; Baskaran, D.; Rajamanickam, R.; Das, R.; Pakshirajan, K.; Bilyaminu, A.M.; et al. Application of artificial intelligence tools in wastewater and waste gas treatment systems: Recent advances and prospects. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadebo, D.; Obura, D.; Etyang, N.; Kimera, D. Economic and social perspectives of implementing artificial intelligence in drinking water treatment systems for predicting coagulant dosage: A transition toward sustainability. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 23, 100987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obidallah, W.J. Artificial intelligence modeling and simulation of membrane-based separation of water pollutants via ozone Process: Evaluation of separation. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2024, 51, 102627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Rong, S.; Wang, R.; Yu, S. Recent advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning for nonlinear relationship analysis and process control in drinking water treatment: A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 405, 126673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Sun, Q.; Lin, Y.; Ping, Q.; Peng, N.; Wang, L.; Li, Y. Application of artificial intelligence in (waste)water disinfection: Emphasizing the regulation of disinfection by-products formation and residues prediction. Water Res. 2024, 253, 121267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Yu, J.; Shao, X.; Jiang, Y.; Yu, J.; Deng, S.; Li, P. Interpretable artificial intelligence for advanced oxidation systems: Principle, operations and performance. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2023, 180, 242–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serna-Carrizales, J.C.; Zárate-Guzmán, A.I.; Flores-Ramírez, R.; Díaz de León-Martínez, L.; Aguilar-Aguilar, A.; Warren-Vega, W.M.; Bailón-García, E.; Ocampo-Pérez, R. Application of artificial intelligence for the optimization of advanced oxidation processes to improve the water quality polluted with pharmaceutical compounds. Chemosphere 2024, 351, 141216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Sun, W.; Wei, H.; Sun, C. Application of artificial intelligence for predicting reaction results in advanced oxidation processes. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 23, 101550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Wang, X.; Xu, D.; Liu, H.; Zhang, H.; Yu, Q.; Bi, Y.; Li, L. Machine Learning-Assisted Catalysts for Advanced Oxidation Processes: Progress, Challenges, and Prospects. Catalysts 2025, 15, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekhate, C.; Srivastava, J.K. Recent advances in ozone-based advanced oxidation processes for treatment of wastewater—A review. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2020, 3, 100031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowideit, P.; von Sonntag, C. Reaction of Ozone with Ethene and Its Methyl- and Chlorine-Substituted Derivatives in Aqueous Solution. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1998, 32, 1112–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality, 4th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Popov, M.; Kragulj Isakovski, M.; Molnar Jazić, J.; Tubić, A.; Watson, M.; Šćiban, M.; Agbaba, J. Fate of natural organic matter and oxidation/disinfection by-products formation at a full-scale. Environ. Technol. 2021, 42, 3475–3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simetić, T.; Nikić, J.; Kuč, M.; Tamindžija, D.; Tubić, A.; Agbaba, J.; Molnar Jazić, J. New insight into the degradation of sunscreen agents in water treatment using UV-driven advanced oxidation processes. Processes 2024, 12, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar Jazić, J.; Đurkić, T.; Bašić, B.; Watson, M.; Apostolović, T.; Tubić, A.; Agbaba, J. Degradation of a chloroacetanilide herbicide in natural waters using UV activated hydrogen peroxide, persulfate and peroxymonosulfate processes. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2020, 6, 2800–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APHA-AWWA-WEF. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 23rd ed; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.H. Greedy Function Approximation: A Gradient Boosting Machine. Ann. Stat. 2001, 29, 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, V.; Hinton, G.E. Rectified Linear Units Improve Restricted Boltzmann Machines. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML-10), Haifa, Israel, 21–24 June 2010; pp. 807–814. [Google Scholar]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Duchesnay, E. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2012, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | R2 | MSE | MAE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | 0.987 | 10.78 | 2.488 |

| Gradient Boosting | 0.982 | 14.97 | 2.796 |

| Stacked Ensemble (NN + GB + Ridge) | 0.981 | 15.73 | 2.390 |

| Linear Regression | 0.956 | 36.20 | 4.535 |

| Ridge Regression | 0.953 | 38.89 | 4.252 |

| Neural Network (MLP) | 0.899 | 82.97 | 6.194 |

| Parameter | Unit of Measurement | GW1 | GW2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | - | 7.14 ± 0.17 | 6.83 ± 0.25 |

| Electrical conductivity | µS/cm | 1317 ± 136 | 1652 ± 52 |

| Turbidity | NTU | 59.9 ± 11.3 | 68.7 ± 9.3 |

| Total organic carbon (TOC) | mg/L C | 4.05 ± 1.6 | 4.35 ± 1.6 |

| Total aldehydes | µg/L | 4.30 ± 1.65 | 6.32 ± 1.55 |

| Formaldehyde | µg/L | 2.50 ± 0.55 | 3.81 ± 0.73 |

| Acetaldehyde | µg/L | 1.30 ± 0.31 | 1.93 ± 0.22 |

| Glyoxal | µg/L | 0.32 ± 0.18 | 0.38 ± 0.15 |

| Methylglyoxal | µg/L | 0.18 ± 0.05 | 0.20 ± 0.10 |

| Permanganate index | mg/L | 12.6 ± 0.25 | 14.2 ± 0.15 |

| Ammonia | mg N/L | 1.10 ± 0.33 | 3.30 ± 1.18 |

| Nitrates | mg N/L | 0.21 ± 0.09 | 0.24 ± 0.06 |

| Nitrites | mg N/L | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.01 |

| Orthophosphates | mg P/L | 0.24 ± 0.13 | 0.26 ± 0.10 |

| Hydrogencarbonates | mg/L | 676 ± 35 | 788 ± 25 |

| Bromide | mg/l | 0.02 ± 0.03 | 0.03 ± 0.1 |

| Hardness | mg/L | 494 ± 120 | 700 ± 56 |

| Iron | mg/L | 6.06 ± 2.2 | 16.5 ± 2.1 |

| Manganese | mg/L | 0.26 ± 0.06 | 0.3 ± 0.06 |

| Vinyl chloride | µg/L | 11.6 ± 0.61 | 17.8 ± 0.74 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Molnar Jazić, J.; Arsenović, M.; Simetić, T.; Tenodi, S.; Kragulj Isakovski, M.; Tubić, A.; Agbaba, J. Vinyl Chloride Degradation Using Ozone-Based Advanced Oxidation Processes: Bridging Groundwater Treatment and Machine Learning for Smarter Solutions. Molecules 2025, 30, 4737. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244737

Molnar Jazić J, Arsenović M, Simetić T, Tenodi S, Kragulj Isakovski M, Tubić A, Agbaba J. Vinyl Chloride Degradation Using Ozone-Based Advanced Oxidation Processes: Bridging Groundwater Treatment and Machine Learning for Smarter Solutions. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4737. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244737

Chicago/Turabian StyleMolnar Jazić, Jelena, Marko Arsenović, Tajana Simetić, Slaven Tenodi, Marijana Kragulj Isakovski, Aleksandra Tubić, and Jasmina Agbaba. 2025. "Vinyl Chloride Degradation Using Ozone-Based Advanced Oxidation Processes: Bridging Groundwater Treatment and Machine Learning for Smarter Solutions" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4737. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244737

APA StyleMolnar Jazić, J., Arsenović, M., Simetić, T., Tenodi, S., Kragulj Isakovski, M., Tubić, A., & Agbaba, J. (2025). Vinyl Chloride Degradation Using Ozone-Based Advanced Oxidation Processes: Bridging Groundwater Treatment and Machine Learning for Smarter Solutions. Molecules, 30(24), 4737. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244737