From Elixirs to Geroscience: A Historical and Molecular Perspective on Anti-Aging Medicine

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. From Esoterism to Science: The History of Anti-Aging

3. Preclinical Evidence: Models of Aging

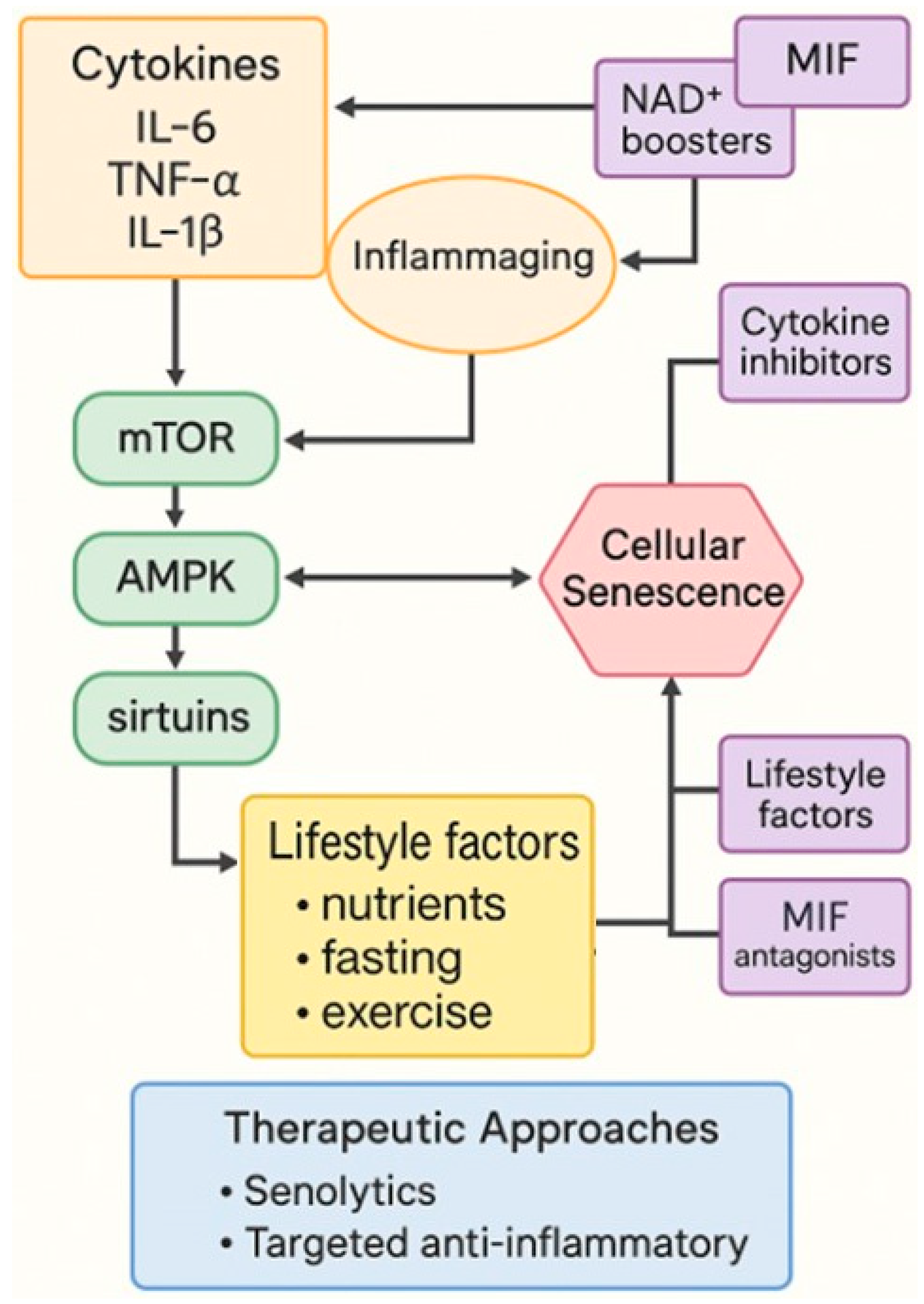

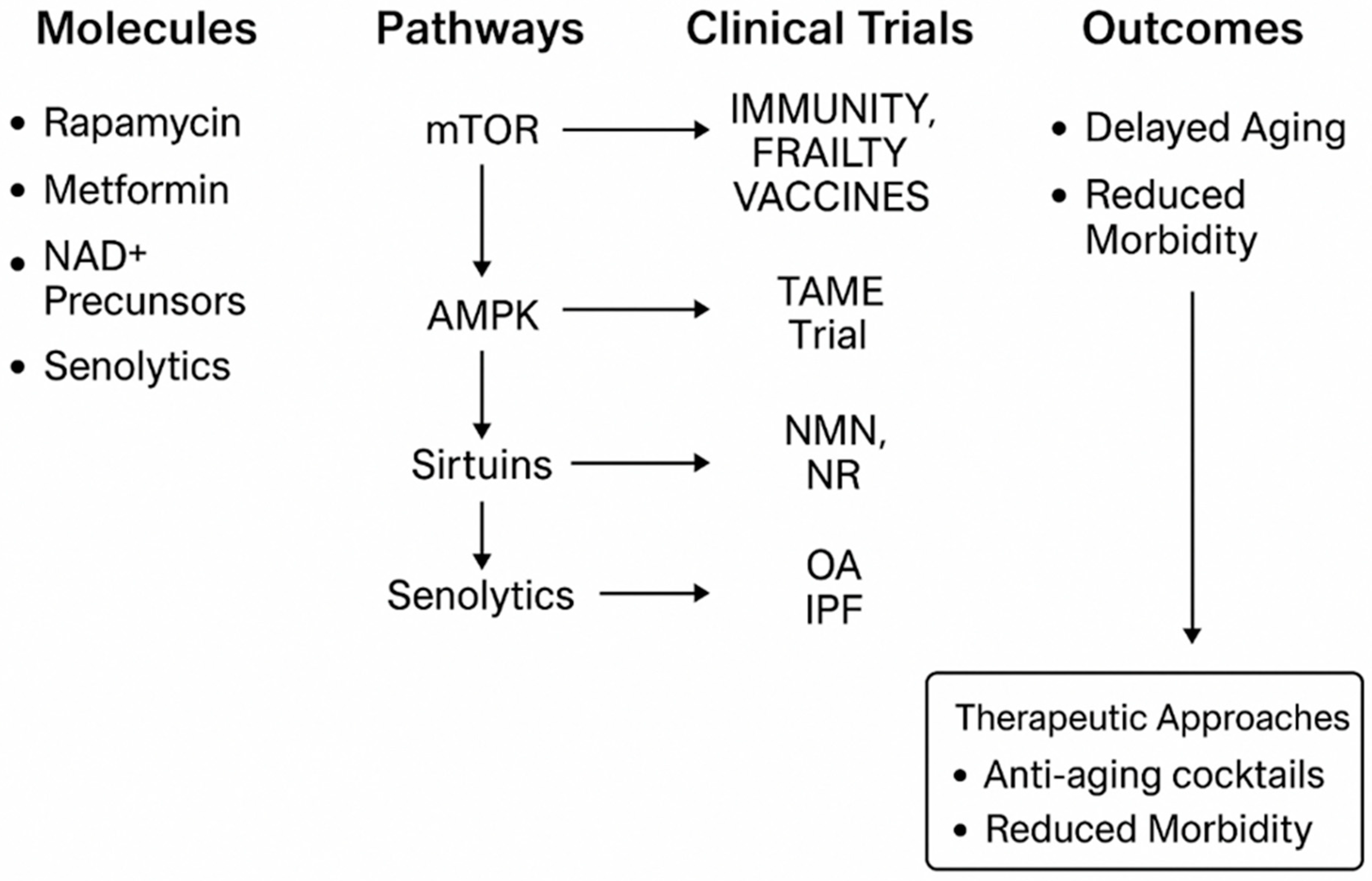

4. Molecular Pathways of Aging and Intervention

5. Cytokines, Inflammaging and MIF

6. Clinical Trials and Translational Approaches in Geroscience

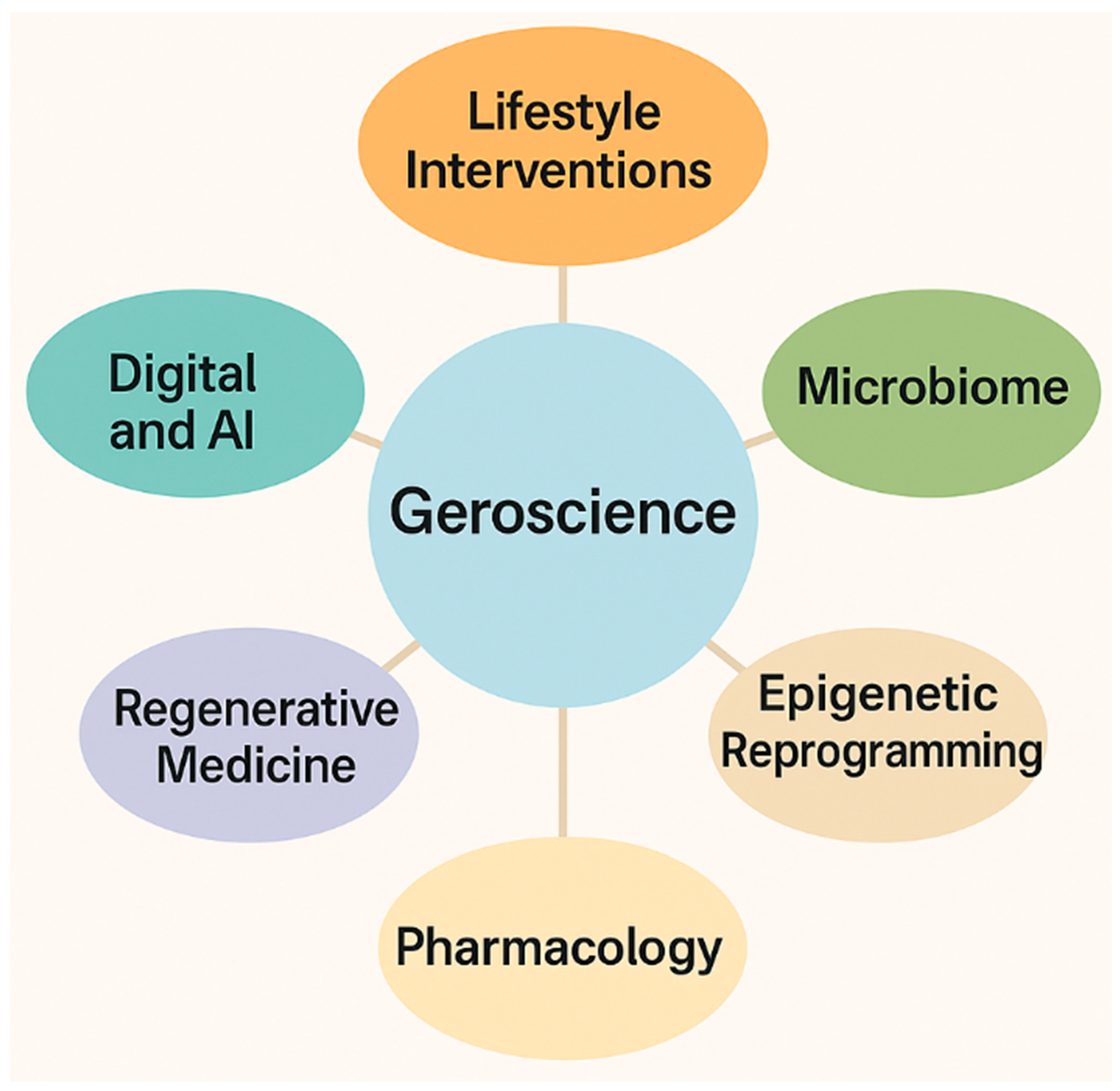

Pharmacokinetic, Safety, and Translational Considerations of Major Geroprotective Compounds

| Molecule | ADME Profile | Typical Human Doses | Adverse Effects | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rapamycin/Rapalogues | Low oral bioavailability (10–20%); CYP3A4 metabolism; long t½ (~60 h); P-gp substrate | Intermittent 2–6 mg/week; low-dose regimens in aging trials | Hyperlipidemia, stomatitis, wound-healing delay, edema, infection risk | [131,149,151,152,154] |

| Metformin | Absorbed via OCT1; not metabolized; renal excretion; t½ 4–9 h | 1–2 g/day (standard); lower doses in aging trials | GI upset, B12 deficiency; rare lactic acidosis (renal impairment) | [9,133,155] |

| Resveratrol | Rapid glucuronidation & sulfation; low systemic bioavailability | 150–1000 mg/day; enhanced forms up to 2 g/day | Occasional hepatotoxicity at high doses; GI discomfort | [157,158,159] |

| Curcumin | <1% bioavailability; rapid metabolism; improved with piperine/nanocarriers | 500–2000 mg/day; enhanced to 4–8 g/day | GI issues; rare hepatotoxicity (high-dose extracts) | [160] |

| Quercetin | Poor absorption; extensive metabolism; short t½ | 500–1000 mg/day in small clinical studies | Headache, GI discomfort; CYP3A4 interactions | [162] |

| NAD+ Boosters (NR/NMN) | NR: good oral absorption, raises NAD+ rapidly; NMN: transporter-mediated uptake | NR 250–1000 mg/day; NMN 300–600 mg/day | Generally well tolerated; theoretical cancer/metabolic risks | [153] |

7. Registered Clinical Trials in Geroscience

8. New Dimensions in Geroscience: Beyond Pharmacology

9. Sex Differences in Aging and Longevity: XX vs. XY at the Crossroads of Biology and Therapy

10. Conclusions and Future Perspectives in Geroscience

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Glossary

| Term | Definition |

| AMPK (AMP-activated protein kinase) | Cellular energy sensor promoting catabolic pathways, enhancing autophagy and stress resistance. |

| Autophagy | Catabolic process degrading damaged proteins and organelles. |

| Caloric Restriction (CR) | Reduced caloric intake without malnutrition; extends lifespan. |

| Epigenetic Clocks | DNA methylation-based predictors of biological age. |

| Geroscience | Field linking aging biology with chronic diseases. |

| GlyNAC | Glycine + NAC combination restoring glutathione and reducing oxidative stress. |

| mTOR | Regulator of growth, protein synthesis, and nutrient sensing. |

| NAD+ | Coenzyme essential for mitochondrial function; declines with age. |

| NAD+ Boosters | Compounds increasing NAD+ levels (NR, NMN). |

| Rapalogues | Rapamycin analogs with distinct PK/safety profiles. |

| SASP | Inflammatory secretome of senescent cells. |

| Senescent Cells | Cells in permanent cycle arrest producing SASP. |

| Senolytics | Drugs eliminating senescent cells selectively. |

| Sirtuins | NAD+-dependent enzymes regulating metabolism and aging. |

| Telomeres | Repetitive DNA ends shortening with cell division. |

| Telomerase | Enzyme maintaining telomere length. |

| Fasting-Mimicking Diets | Dietary protocols mimicking fasting effects. |

| Nutrient-Sensing Pathways | mTOR, AMPK, sirtuins, IGF-1 regulating lifespan. |

| IGF-1/GH axis | Hormonal axis involved in growth and longevity. |

| FOXO transcription factors | Regulators of stress resistance and longevity. |

| DNA methylation drift | Stochastic age-related methylation changes. |

| Inflammaging | Chronic low-grade inflammation increasing with age. |

| Mitophagy | Autophagic removal of damaged mitochondria. |

| Proteostasis | Maintenance of protein homeostasis. |

| Senomorphic drugs | Agents suppressing SASP without killing cells. |

| Autophagy flux | Efficiency of autophagic degradation. |

| Epigenetic reprogramming | Partial resetting of epigenetic marks. |

| Geroprotectors | Interventions slowing biological aging. |

| Polyphenols/antioxidants | Plant compounds modulating oxidative stress. |

| Xenobiotics | Foreign substances requiring detoxification. |

| ADME | Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion. |

| Half-life | Time for plasma concentration to halve. |

| Bioavailability | Fraction of active substance reaching circulation. |

| Pathway intermediates | Molecules mediating signaling events. |

| Biomarkers (proteomic/metabolomic) | Molecular signatures of aging. |

| Sex-specific differences | Aging and treatment differences by sex. |

| Metformin mechanisms | Actions via AMPK activation and mitochondrial effects. |

| mTORC1 vs. mTORC2 | Distinct complexes regulating growth and insulin signaling. |

| TOR inhibitors (2nd generation) | Selective mTOR inhibitors with improved profiles. |

References

- Crespi, O.; Rosset, F.; Pala, V.; Sarda, C.; Accorinti, M.; Quaglino, P.; Ribero, S. Cosmeceuticals for Anti-Aging: Mechanisms, Clinical Evidence, and Regulatory Insights—A Comprehensive Review. Cosmet 2025, 12, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arıcı, M. Medieval Islamic Medicine. In Nazariyat İslam Felsefe ve Bilim Tarihi Araştırmaları Derg (Journal Hist Islam Philos Sci.); Pormann, P.E., Savage-Smith, E., Eds.; Nazariyat Journal for the History of Islamic Philosophy And Sciences; İLEM–Scientific Studies Association: Istanbul, Turkey, 2014; Volume 1, pp. 174–179, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metchnikoff, E. The Prolongation of Life: Optimistic Studies; William Heinemann: London, UK, 1907. [Google Scholar]

- Samaras, T.T. (Ed.) Human Body Size and the Laws of Scaling: Physiological, Performance, Growth, Longevity and Ecological Ramifications; Nova Science Publishers Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, E.H.; Epel, E.S.; Lin, J. Human telomere biology: A contributory and interactive factor in aging, disease risks, and protection. Science 2015, 350, 1193–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, B.K.; Berger, S.L.; Brunet, A.; Campisi, J.; Cuervo, A.M.; Epel, E.S.; Franceschi, C.; Lithgow, G.J.; Morimoto, R.I.; Pessin, J.E.; et al. Geroscience: Linking aging to chronic disease. Cell 2014, 159, 709–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, L.; Partridge, L. Promoting health and longevity through diet: From model organisms to humans. Cell 2015, 161, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madeo, F.; Carmona-Gutierrez, D.; Hofer, S.J.; Kroemer, G. Caloric Restriction Mimetics against Age-Associated Disease: Targets, Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Potential. Cell Metab. 2019, 29, 592–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzilai, N.; Crandall, J.P.; Kritchevsky, S.B.; Espeland, M.A. Metformin as a Tool to Target Aging. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 1060–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekhar, R.V. GlyNAC Supplementation Improves Glutathione Deficiency, Oxidative Stress, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Inflammation, Aging Hallmarks, Metabolic Defects, Muscle Strength, Cognitive Decline, and Body Composition: Implications for Healthy Aging. J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 3606–3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Justice, J.N.; Nambiar, A.M.; Tchkonia, T.; LeBrasseur, N.K.; Pascual, R.; Hashmi, S.K.; Prata, L.; Masternak, M.M.; Kritchevsky, S.B.; Musi, N.; et al. Senolytics in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Results from a first-in-human, open-label, pilot study. EBioMedicine 2019, 40, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, S.; Raj, K. DNA methylation-based biomarkers and the epigenetic clock theory of ageing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2018, 19, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrucci, L.; Fabbri, E. Inflammageing: Chronic inflammation in ageing, cardiovascular disease, and frailty. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2018, 15, 505–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayor, A. Gods and Robots: Myths, Machines, and Ancient Dreams of Technology; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NU, USA, 2020; p. 275. [Google Scholar]

- Nutton, V. Ancient Medicine; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2013; p. 488. Available online: https://books.google.com/books/about/Ancient_Medicine.html?hl=it&id=uWGr2Be9NjMC (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Ding, X.; Ma, X.; Meng, P.; Yue, J.; Li, L.; Xu, L. Potential Effects of Traditional Chinese Medicine in Anti-Aging and Aging-Related Diseases: Current Evidence and Perspectives. Clin. Interv. Aging 2024, 19, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, L.C.; Machado, J.P.; Monteiro, F.J.; Greten, H.J. Understanding Traditional Chinese Medicine Therapeutics: An Overview of the Basics and Clinical Applications. Healthcare 2021, 9, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Journal of Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine | ScienceDirect.com by Elsevier. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/journal-of-ayurveda-and-integrative-medicine (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Rao, R.V. Ayurveda and the science of aging. J. Ayurveda Integr. Med. 2017, 9, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, Y. Review on Health Preservation in Traditional Chinese Medicine; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 592–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guluma, E.H.; Lemma, T.M.; Workineh, S.S.; Kitolo, G.K.; Gello, B.M.; Robi, M.K.; Desalegn, A.G.; Bayleyegn, G.M. Indigenous medicinal knowledge and therapeutic practices of the endangered Ongota/Birale of Southwest Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2025, 21, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siraisi, N.G. Avicenna in Renaissance Italy: The Canon and Medical Teaching in Italian Universities After 1500. 2014. Available online: https://books.google.com/books/about/Avicenna_in_Renaissance_Italy.html?hl=it&id=CPf_AwAAQBAJ (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Principe, L. The Secrets of Alchemy; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2013; p. 281. Available online: https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Secrets_of_Alchemy.html?hl=it&id=sR2qKWpO-ssC (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- O’Toole, P.W.; Jeffery, I.B. Gut microbiota and aging. Science 2015, 350, 1214–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stark, J.F. Hormones, 1918–1929. In The Cult of Youth; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 24–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayflick, L. The limited in vitro lifetime of human diploid cell strains. Exp. Cell Res. 1965, 37, 614–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shay, J.W.; Wright, W.E. Hayflick, his limit, and cellular ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000, 1, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, D. Aging: A theory based on free radical and radiation chemistry. J. Gerontol. 1956, 11, 298–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladyshev, V.N. The Free Radical Theory of Aging Is Dead. Long Live the Damage Theory! Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014, 20, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, V.D.; Antebi, A.; Bartke, A.; Barzilai, N.; Brown-Borg, H.M.; Caruso, C.; Curiel, T.J.; Cabo, R.; Franceschi, C.; Gems, D.; et al. Interventions to Slow Aging in Humans: Are We Ready? Aging Cell 2015, 14, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. Hallmarks of aging: An expanding universe. Cell 2023, 186, 243–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaib, S.; Tchkonia, T.; Kirkland, J.L. Cellular senescence and senolytics: The path to the clinic. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1556–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, A.S.; Gubbi, S.; Barzilai, N. Benefits of Metformin in Attenuating the Hallmarks of Aging. Cell Metab. 2020, 32, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackey, T. An ethical assessment of anti-aging medicine. J. Anti Aging Med. 2003, 6, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longo, V.D.; Shadel, G.S.; Kaeberlein, M.; Kennedy, B. Replicative and chronological aging in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell Metab. 2012, 16, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deprez, M.A.; Eskes, E.; Winderickx, J.; Wilms, T. The TORC1-Sch9 pathway as a crucial mediator of chronological lifespan in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res. 2018, 18, foy048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutphin, G.L.; Backer, G.; Sheehan, S.; Bean, S.; Corban, C.; Liu, T.; Peters, M.J.; van Meurs, J.B.J.; Murabito, J.M.; Johnson, A.D.; et al. Caenorhabditis elegans orthologs of human genes differentially expressed with age are enriched for determinants of longevity. Aging Cell. 2017, 16, 672–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Driscoll, M. EGF signaling comes of age: Promotion of healthy aging in C. elegans. Exp. Gerontol. 2011, 46, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, N.M.; Tran, S.H.; Shim, Y.H.; Kang, K. Caenorhabditis elegans as a powerful tool in natural product bioactivity research. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2022, 65, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogina, B.; Reenan, R.A.; Nilsen, S.P.; Helfand, S.L. Extended life-span conferred by cotransporter gene mutations in Drosophila. Science 2000, 290, 2137–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrns, C.N.; Perlegos, A.E.; Miller, K.N.; Jin, Z.; Carranza, F.R.; Manchandra, P.; Beveridge, C.H.; Randolph, C.E.; Chaluvadi, V.S.; Zhang, S.L.; et al. Senescent glia link mitochondrial dysfunction and lipid accumulation. Nature 2024, 630, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.K.; Brunet, A. The African turquoise killifish: A research organism to study vertebrate aging and diapause. Aging Cell 2018, 17, e12757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boos, F.; Chen, J.; Brunet, A. The African Turquoise Killifish: A Scalable Vertebrate Model for Aging and Other Complex Phenotypes. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2024, 2024, 107737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva-Álvarez, S.; Guerra-Varela, J.; Sobrido-Cameán, D.; Quelle, A.; Barreiro-Iglesias, A.; Sánchez, L.; Collado, M. Cell senescence contributes to tissue regeneration in zebrafish. Aging Cell 2019, 19, e13052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva-Álvarez, S.; Guerra-Varela, J.; Sobrido-Cameán, D.; Quelle, A.; Barreiro-Iglesias, A.; Sánchez, L.; Collado, M. Developmentally-programmed cellular senescence is conserved and widespread in zebrafish. Aging 2020, 12, 17895–17901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Walters, H.E.; Pasquini, G.; Singh, S.P.; Lachnit, M.; Oliveira, C.R.; León-Periñán, D.; Petzold, A.; Kesavan, P.; Adrados, C.S.; et al. Cellular senescence promotes progenitor cell expansion during axolotl limb regeneration. Dev. Cell 2023, 58, 2416–2427.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansfield, L.; Ramponi, V.; Gupta, K.; Stevenson, T.; Mathew, A.B.; Barinda, A.J.; Herbstein, F.; Morsli, S. Emerging insights in senescence: Pathways from preclinical models to therapeutic innovations. npj Aging 2024, 10, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weindruch, R.; Walford, R.L.; Fligiel, S.; Guthrie, D. The retardation of aging in mice by dietary restriction: Longevity, cancer, immunity and lifetime energy intake. J. Nutr. 1986, 116, 641–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berryman, D.E.; Christiansen, J.S.; Johannsson, G.; Thorner, M.O.; Kopchick, J.J. Role of the GH/IGF-1 axis in lifespan and healthspan: Lessons from animal models. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2008, 18, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, D.E.; Strong, R.; Sharp, Z.D.; Nelson, J.F.; Astle, C.M.; Flurkey, K.; Nadon, N.L.; Wilkinson, J.E.; Frenkel, K.; Carter, C.S.; et al. Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice. Nature 2009, 460, 392–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahour, N.; Bleichmar, L.; Abarca, C.; Wilmann, E.; Sanjines, S.; Aguayo-Mazzucato, C. Clearance of p16Ink4a-positive cells in a mouse transgenic model does not change β-cell mass and has limited effects on their proliferative capacity. Aging 2023, 15, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Wang, L.; Gasek, N.S.; Zhou, Y.; Kim, T.; Guo, C.; Jellison, E.R.; Haynes, L.; Yadav, S.; Tchkonia, T.; et al. An inducible p21-Cre mouse model to monitor and manipulate p21-highly-expressing senescent cells in vivo. Nat. Aging 2021, 1, 962–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, S.J.; MacArthur, M.R.; Kane, A.E. Optimizing preclinical models of ageing for translation to clinical trials. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 91, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iglesias-Carres, L.; Neilson, A.P. Utilizing preclinical models of genetic diversity to improve translation of phytochemical activities from rodents to humans and inform personalized nutrition. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 11077–11105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kõks, S.; Dogan, S.; Tuna, B.G.; González-Navarro, H.; Potter, P.; Vandenbroucke, R.E. Mouse models of ageing and their relevance to disease. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2016, 160, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermogenous, C.; Green, C.; Jackson, T.; Ferguson, M.; Lord, J.M. Treating age-related multimorbidity: The drug discovery challenge. Drug Discov. Today 2020, 25, 1403–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koert, A.; Ploeger, A.; Bockting, C.L.H.; Schmidt, M.V.; Lucassen, P.J.; Schrantee, A.; Mul, J.D. The social instability stress paradigm in rat and mouse: A systematic review of protocols, limitations, and recommendations. Neurobiol. Stress 2021, 15, 100410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, K.; Dicks, N.; Glanzner, W.G.; Agellon, L.B.; Bordignon, V. Efficacy of the porcine species in biomedical research. Front. Genet. 2015, 6, 159179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, S.; Yin, W.; Wang, Z.; Kusunoki, M.; Lian, X.; Koike, T.; Fan, J.; Zhang, Q. A minipig model of high-fat/high-sucrose diet-induced diabetes and atherosclerosis. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 2004, 85, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Niu, M.; Zhao, C.; Li, X.; Chen, H. Preliminary study of metabonomic changes during the progression of atherosclerosis in miniature pigs. Anim. Model. Exp. Med. 2024, 7, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerholz, D.K.; Burrough, E.R.; Kirchhof, N.; Anderson, D.J.; Helke, K.L. Swine models in translational research and medicine. Vet. Pathol. 2024, 61, 512–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Q.; Chen, T.Y.; Wang, L.; Cheng, H.-X.; Li, H.-B.; He, C.-Q.; Fu, C.-Y.; Wei, Q. Cardiac rehabilitation in porcine models: Advances in therapeutic strategies for ischemic heart disease. Zool. Res. 2025, 46, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tian, X.; Luo, J.; Bao, T.; Wang, S.; Wu, X. Molecular mechanisms of aging and anti-aging strategies. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunney, J.K.; Van Goor, A.; Walker, K.E.; Hailstock, T.; Franklin, J.; Dai, C. Importance of the pig as a human biomedical model. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eabd5758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattison, J.A.; Colman, R.J.; Beasley, T.M.; Allison, D.B.; Kemnitz, J.W.; Roth, G.S.; Ingram, D.K.; Weindruch, R.; de Cabo, R.; Anderson, R.M. Caloric restriction improves health and survival of rhesus monkeys. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pifferi, F.; Aujard, F. Caloric restriction, longevity and aging: Recent contributions from human and non-human primate studies. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2019, 95, 109702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardif, S.D.; Mansfield, K.G.; Ratnam, R.; Ross, C.N.; Ziegler, T.E. The Marmoset as a Model of Aging and Age-Related Diseases. ILAR J. 2011, 52, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadoun, A.; Rosito, M.; Fonta, C.; Girard, P. Key periods of cognitive decline in a nonhuman primate model of cognitive aging, the common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus). Neurobiol. Aging 2019, 74, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanderlip, C.R.; Jutras, M.L.; Asch, P.A.; Zhu, S.Y.; Lerma, M.N.; Buffalo, E.A.; Glavis-Bloom, C. Parallel patterns of age-related working memory impairment in marmosets and macaques. Aging 2025, 17, 778–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emery Thompson, M.; Rosati, A.G.; Snyder-Mackler, N. Insights from evolutionarily relevant models for human ageing. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2020, 375, 20190605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamroo, A.; Kakroudi, M.H.; Sarmadian, A.J.; Firouzabadi, A.; Mousavi, S.; Yazdanpanah, N.; Saleki, K.; Rezaei, N. Immunosenescence and organoids: Pathophysiology and therapeutic opportunities. Immun. Ageing 2025, 22, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, V.; Singh, B.N.; Singh, A.K. Transformative advances in modeling brain aging and longevity: Success, challenges and future directions. Ageing Res. Rev. 2025, 108, 102753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehninger, D.; Neff, F.; Xie, K. Longevity, aging and rapamycin. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2014, 71, 4325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxton, R.A.; Sabatini, D.M. mTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease. Cell 2017, 168, 960–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Liu, H.; Hu, Q.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, W.; Ren, J.; Zhu, F.; Liu, G.-H. Epigenetic regulation of aging: Implications for interventions of aging and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther 2022, 7, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, J.; Kongsberg, W.H.; Pan, Y.; Hao, C.; Wang, X.; Sun, J. Caloric restriction induced epigenetic effects on aging. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 10, 1079920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballesteros-Álvarez, J.; Andersen, J.K. mTORC2: The other mTOR in autophagy regulation. Aging Cell 2021, 20, e13431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivimey-Cook, E.R.; Sultanova, Z.; Maklakov, A.A. Rapamycin, Not Metformin, Mirrors Dietary Restriction-Driven Lifespan Extension in Vertebrates: A Meta-Analysis. Aging Cell 2025, 24, e70131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, Z.D.; Strong, R. Rapamycin, the only drug that consistently demonstrated to increase mammalian longevity. An update. Exp. Gerontol. 2023, 176, 112166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghdadi, M.; Nespital, T.; Monzó, C.; Deelen, J.; Grönke, S.; Partridge, L. Intermittent rapamycin feeding recapitulates some effects of continuous treatment while maintaining lifespan extension. Mol. Metab. 2024, 81, 101902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moel, M.; Harinath, G.; Lee, V.; Nyquist, A.; Morgan, S.L.; Isman, A.; Zalzala, S. Influence of rapamycin on safety and healthspan metrics after one year: PEARL trial results. Aging 2025, 17, 908–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roark, K.M.; Iffland, P.H. Rapamycin for longevity: The pros, the cons, and future perspectives. Front. Aging 2025, 6, 1628187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkioni, L.; Nespital, T.; Baghdadi, M.; Monzó, C.; Bali, J.; Nassr, T.; Cremer, A.L.; Beyer, A.; Deelen, J.; Backes, H.; et al. The geroprotectors trametinib and rapamycin combine additively to extend mouse healthspan and lifespan. Nat. Aging 2025, 5, 1249–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewald, F.; Nörz, D.; Grottke, A.; Hofmann, B.T.; Nashan, B.; Jücker, M. Dual Inhibition of PI3K-AKT-mTOR- and RAF-MEK-ERK-signaling is synergistic in cholangiocarcinoma and reverses acquired resistance to MEK-inhibitors. Investig. New Drugs 2014, 32, 1144–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardie, D.G. AMP-activated protein kinase: Maintaining energy homeostasis at the cellular and whole-body levels. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2014, 34, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantó, C.; Gerhart-Hines, Z.; Feige, J.N.; Lagouge, M.; Noriega, L.; Milne, J.C.; Elliott, P.J.; Puigserver, P.; Auwerx, J. AMPK regulates energy expenditure by modulating NAD+ metabolism and SIRT1 activity. Nature 2009, 458, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korotkov, A.; Seluanov, A.; Gorbunova, V. Sirtuin 6: Linking longevity with genome and epigenome stability. Trends Cell Biol. 2021, 31, 994–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, P.; Rai, A.K.; Syiem, D.; Garay, R.P. Sirtuin activators as an anti-aging intervention for longevity. Open Explor. 2025, 3, 100881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carollo, C.; Sorce, A.; Cirafici, E.; Mulè, G.; Caimi, G. Sirtuins and Resveratrol in Cardiorenal Diseases: A Narrative Review of Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshino, M.; Yoshino, J.; Kayser, B.D.; Patti, G.J.; Franczyk, M.P.; Mills, K.F.; Sindelar, M.; Pietka, T.; Patterson, B.W.; Imai, S.-I.; et al. Nicotinamide mononucleotide increases muscle insulin sensitivity in prediabetic women. Science 2021, 372, 1224–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantó, C.; Jiang, L.Q.; Deshmukh, A.S.; Mataki, C.; Coste, A.; Lagouge, M.; Zierath, J.R.; Auwerx, J. Interdependence of AMPK and SIRT1 for metabolic adaptation to fasting and exercise in skeletal muscle. Cell Metab. 2010, 11, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, S.N.; Lamming, D.W. Next Generation Strategies for Geroprotection via mTORC1 Inhibition. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2019, 75, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, K.H.; Arriola Apelo, S.I.; Yu, D.; Brinkman, J.A.; Velarde, M.C.; Syed, F.A.; Liao, C.-Y.; Baar, E.L.; Carbajal, K.A.; Sherman, D.S.; et al. A novel rapamycin analog is highly selective for mTORC1 in vivo. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hands, J.M.; Lustgarten, M.S.; Frame, L.A.; Rosen, B. What is the clinical evidence to support off-label rapamycin therapy in healthy adults? Aging 2025, 17, 2079–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, V.M.; Gururaj, S.B.; Thumbigere-Math, V.; Kugaji, M.S.; Kandaswamy, E. Rapamycin’s Role in Periodontal Health and Therapeutics: A Scoping Review. JDR Clin. Transl. Res. 2025, 23800844251366967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.Y.; Kerns, K.A.; Ouellette, A.; Robinson, L.; Morris, H.D.; Kaczorowski, C.; Park, S.-I.; Mekvanich, T.; Kang, A.; McLean, J.S.; et al. Rapamycin rejuvenates oral health in aging mice. Elife 2020, 9, e54318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, X.; Sun, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Hao, D.; Liu, W.; Wu, R.; Kong, F.; Peng, X.; Li, J. Short-term rapamycin treatment increases ovarian lifespan in young and middle-aged female mice. Aging Cell 2017, 16, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, Y.; Ren, J.; Qu, J.; Liu, G.H. Gene therapy strategies for aging intervention. Cell Insight 2025, 4, 100254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franceschi, C.; Garagnani, P.; Parini, P.; Giuliani, C.; Santoro, A. Inflammaging: A new immune-metabolic viewpoint for age-related diseases. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 14, 576–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulop, T.; Larbi, A.; Dupuis, G.; Le Page, A.; Frost, E.H.; Cohen, A.A.; Witkowski, J.M.; Franceschi, C. Immunosenescence and Inflamm-Aging As Two Sides of the Same Coin: Friends or Foes? Front. Immunol. 2018, 8, 1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaud, M.; Balardy, L.; Moulis, G.; Gaudin, C.; Peyrot, C.; Vellas, B.; Cesari, M.; Nourhashemi, F. Proinflammatory cytokines, aging, and age-related diseases. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2013, 14, 877–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youm, Y.H.; Kanneganti, T.D.; Vandanmagsar, B.; Zhu, X.; Ravussin, A.; Adijiang, A.; Owen, J.S.; Thomas, M.J.; Francis, J.; Parks, J.S.; et al. The Nlrp3 inflammasome promotes age-related thymic demise and immunosenescence. Cell Rep. 2012, 1, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arosio, B.; Ferri, E.; Mari, D.; Tobaldini, E.; Vitale, G.; Montano, N. The influence of inflammation and frailty in the aging continuum. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2023, 215, 111872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, C.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Qian, P.; Huang, H. Inflammation and aging: Signaling pathways and intervention therapies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faust, H.J.; Zhang, H.; Han, J.; Wolf, M.T.; Jeon, O.H.; Sadtler, K.; Peña, A.N.; Chung, L.; Maestas, D.R.; Tam, A.J.; et al. IL-17 and immunologically induced senescence regulate response to injury in osteoarthritis. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 5493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, A.; Kuchroo, V.K. Th17 cells: From precursors to players in inflammation and infection. Int. Immunol. 2009, 21, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robello Ede, C.; Cipolli, G.C.; Lima, N.A.; Nonato, I.F.; Yassuda, M.S.; Assunção, D.M.X.; Mamoni, R.L.; Pain, A.d.O.; Kemp, A.M.; Voshaar, R.C.O.; et al. Association between IL-17 and sarcopenia in older adults. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. Plus 2025, 2, 100200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.A.; Flores, R.R.; Jang, I.H.; Saathoff, A.; Robbins, P.D. Immune Senescence, Immunosenescence and Aging. Front. Aging 2022, 3, 900028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stosic-Grujicic, S.; Stojanovic, I.; Nicoletti, F. MIF in autoimmunity and novel therapeutic approaches. Autoimmun. Rev. 2009, 8, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliyarbayova, A.; Sultanova, T.; Yaqubova, S.; Najafova, T.; Sadiqova, G.; Salimova, A. Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor: Its Multifaceted Role in Inflammation and Immune Regulation Across Organ Systems. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 59, 569–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calandra, T.; Bernhagen, J.; Metz, C.N.; Spiegel, L.A.; Bacher, M.; Donnelly, T.; Cerami, A.; Bucala, R. MIF as a glucocorticoid-induced modulator of cytokine production. Nature 1995, 377, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangano, K.; Diamantopoulos, A.; Vallianou, N.G.; Stratigou, T.; Panagopoulos, F.; Kounatidis, D.; Dalamaga, M.; Fagone, P.; Nicoletti, F. Serum and urinary levels of MIF, CD74, DDT and CXCR4 among patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus, type 2 diabetes and healthy individuals: Implications for further research. Metab. Open 2024, 24, 100320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petralia, M.C.; Battaglia, G.; Bruno, V.; Pennisi, M.; Mangano, K.; Lombardo, S.D.; Fagone, P.; Cavalli, E.; Saraceno, A.; Nicoletti, F.; et al. The Role of Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor in Alzheimer′s Disease: Conventionally Pathogenetic or Unconventionally Protective? Molecules 2020, 25, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, M.S.; Battaglia, G.; Bruno, V.; Mangano, K.; Fagone, P.; Petralia, M.C.; Nicoletti, F.; Cavalli, E. The dichotomic role of macrophage migration inhibitory factor in neurodegeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stosic-Grujicic, S.; Stojanovic, I.; Maksimovic-Ivanic, D.; Momcilovic, M.; Popadic, D.; Harhaji, L.; Miljkovic, D.; Metz, C.; Mangano, K.; Papaccio, G.; et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) is necessary for progression of autoimmune diabetes mellitus. J. Cell. Physiol. 2008, 215, 665–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouda, H.; Ibrahim, W.N.; Shi, Z.; Alahmadi, F.; Almohammadi, Y.; Al-Haidose, A.; Abdallah, A.M. Impact of the MIF -173G/C variant on cardiovascular disease risk: A meta-analysis of 9047 participants. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1323423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krammer, C.; Yang, B.; Reichl, S.; Besson-Girard, S.; Ji, H.; Bolini, V.; Schulte, C.; Noels, H.; Schlepckow, K.; Jocher, G.; et al. Pathways linking aging and atheroprotection in Mif-deficient atherosclerotic mice. FASEB J. 2023, 37, e22752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauler, M.; Bucala, R.; Lee, P.J. Role of macrophage migration inhibitory factor in age-related lung disease. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2015, 309, L1–L10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.C.; Lee, Y.H. Associations between circulating macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) levels and rheumatoid arthritis, and between MIF gene polymorphisms and disease susceptibility: A meta-analysis. Postgrad. Med. J. 2018, 94, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coperchini, F.; Greco, A.; Teliti, M.; Croce, L.; Chytiris, S.; Magri, F.; Gaetano, C.; Rotondi, M. Inflamm-ageing: How cytokines and nutrition shape the trajectory of ageing. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2025, 82, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panwar, V.; Singh, A.; Bhatt, M.; Tonk, R.K.; Azizov, S.; Raza, A.S.; Sengupta, S.; Kumar, D.; Garg, M. Multifaceted role of mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) signaling pathway in human health and disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salminen, A.; Hyttinen, J.M.T.; Kaarniranta, K. AMP-activated protein kinase inhibits NF-κB signaling and inflammation: Impact on healthspan and lifespan. J. Mol. Med. 2011, 89, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imai, S.I.; Guarente, L. NAD+ and Sirtuins in Aging and Disease. Trends Cell Biol. 2014, 24, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aratani, S.; Nakanishi, M. Recent Advances in Senolysis for Age-Related Diseases. Physiology 2023, 38, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orkaby, A.R.; Thomson, A.; MacFadyen, J.; Besdine, R.; Forman, D.E.; Travison, T.G.; Ridker, P.M. Effect of canakinumab on frailty: A post hoc analysis of the CANTOS trial. Aging Cell 2023, 23, e14029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelle Kahlenberg, J. Anti-inflammatory panacea? The Expanding Therapeutics of IL-1 Blockade. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2016, 28, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, E.; Sankowski, R.; Dietrich, H.; Oikonomidi, A.; Huerta, P.T.; Popp, J.; Al-Abed, Y.; Bacher, M. Key role of MIF-related neuroinflammation in neurodegeneration and cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Med. 2020, 26, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Hu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Zhao, Y.; Li, S.; Luo, A. Macrophage migration inhibitor factor (MIF): Potential role in cognitive impairment disorders. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2024, 77, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangrazzi, L.; Meryk, A. Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Immunosenescence: Modulation Through Interventions and Lifestyle Changes. Biology 2024, 14, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannick, J.B.; Del Giudice, G.; Lattanzi, M.; Valiante, N.M.; Praestgaard, J.; Huang, B.; Lonetto, M.A.; Maecker, H.T.; Kovarik, J.; Carson, S.; et al. mTOR inhibition improves immune function in the elderly. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 268ra179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.J.W.; Hodzic Kuerec, A.; Maier, A.B. Targeting ageing with rapamycin and its derivatives in humans: A systematic review. Lancet Heal. Longev. 2024, 5, e152–e162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Cao, Y.; Qu, Z.; Sun, Y.; Tian, X. The impact of metformin on mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A prospective cohort study. Endocrine 2025, 87, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou Zaki, R.; El-Osta, A. Metformin: Decelerates biomarkers of aging clocks. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buczyńska, A.; Malinowski, P.; Żbikowski, A.; Krętowski, A.J.; Zbucka-Krętowska, M. Metformin modulates oxidative stress via activation of AMPK/NF-κB signaling in Trisomy 21 fibroblasts: An in vitro study. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2025, 12, 1577044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, J.M.; Bellman, S.M.; Stephenson, M.D.; Lisy, K. Metformin reduces all-cause mortality and diseases of ageing independent of its effect on diabetes control: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2017, 40, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covarrubias, A.J.; Perrone, R.; Grozio, A.; Verdin, E. NAD+ metabolism and its roles in cellular processes during ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 22, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, C.R.; Denman, B.A.; Mazzo, M.R.; Armstrong, M.L.; Reisdorph, N.; McQueen, M.B.; Chonchol, M.; Seals, D.R. Chronic nicotinamide riboside supplementation is well-tolerated and elevates NAD+ in healthy middle-aged and older adults. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, T.; Nakagawa, T. The therapeutic perspective of NAD+ precursors in age-related diseases. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2024, 702, 149590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA Reverses NMN Decision: Risks, Quality Concerns, & Consumer Safety | AboutNAD. Available online: https://www.aboutnad.com/blogs/blog/fda-reverses-nmn-decision-risks-quality-concerns-and-alternative-options (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Zhang, L.; Pitcher, L.E.; Yousefzadeh, M.J.; Niedernhofer, L.J.; Robbins, P.D.; Zhu, Y. Cellular senescence: A key therapeutic target in aging and diseases. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 132, e158450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martel, J.; Ojcius, D.M.; Wu, C.Y.; Peng, H.; Voisin, L.; Perfettini, J.; Ko, Y.; Young, J.D. Emerging use of senolytics and senomorphics against aging and chronic diseases. Med. Res. Rev. 2020, 40, 2114–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Kobbe, C. Targeting senescent cells: Approaches, opportunities, challenges. Aging 2019, 11, 12844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.H.; Petty, C.A.; Dixon-McDougall, T.; Lopez, M.V.; Tyshkovskiy, A.; Maybury-Lewis, S.; Tian, X.; Ibrahim, N.; Chen, Z.; Griffin, P.T.; et al. Chemically induced reprogramming to reverse cellular aging. Aging 2023, 15, 5966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönstein, A. (Re-)Defining “Successful Aging” as the Endpoint in Clinical Trials? Current Methods, Challenges, and Emerging Solutions. Gerontologist 2024, 65, gnae058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrucci, L.; Kuchel, G.A. Heterogeneity of Aging: Individual Risk Factors, Mechanisms, Patient Priorities, and Outcomes. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 69, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, A.A.; Beard, J.R.; Ferrucci, L.; Fülöp, T.; Gladyshev, V.N.; Moqri, M.; Rikkert, M.G.M.O.; Picard, M. Balancing the promise and risks of geroscience interventions. Nat. Aging 2025, 5, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins-Chen, A.T.; Thrush, K.L.; Wang, Y.; Minteer, C.J.; Kuo, P.-L.; Wang, M.; Niimi, P.; Sturm, G.; Lin, J.; Moore, A.Z.; et al. A computational solution for bolstering reliability of epigenetic clocks: Implications for clinical trials and longitudinal tracking. Nat. Aging 2022, 2, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yücel, A.D.; Gladyshev, V.N. The long and winding road of reprogramming-induced rejuvenation. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, L.Y.; Lim, H.K.; Abell, M.W.; Zimmerman, J.J. Pharmacokinetics and metabolic disposition of sirolimus in healthy male volunteers after a single oral dose. Ther. Drug Monit. 2006, 28, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, J.E.; Bolin, M.; Thor, D.; Williams, P.A.; Brautaset, R.; Carlsson, M.; Sörensson, P.; Marlevi, D.; Spin-Neto, R.; Probst, M.; et al. Evaluating the effect of rapamycin treatment in Alzheimer’s Disease and aging using in vivo imaging: The ERAP phase IIa clinical study protocol. BMC Neurol. 2024, 24, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trepanier, D.J.; Gallant, H.; Legatt, D.F.; Yatscoff, R.W. Rapamycin: Distribution, pharmacokinetics and therapeutic range investigations: An update. Clin. Biochem. 1998, 31, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emoto, C.; Fukuda, T.; Cox, S.; Christians, U.; Vinks, A.A. Development of a physiologically-based pharmacokinetic model for sirolimus: Predicting bioavailability based on intestinal CYP3A content. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2013, 2, e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeberg, K.A.; Udovich, C.A.C.; Martens, C.R.; Seals, D.R.; Craighead, D.H. Dietary Supplementation With NAD+-Boosting Compounds in Humans: Current Knowledge and Future Directions. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2023, 78, 2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallgren, H.A.; Kivipelto, M.; Plavén-Sigray, P.; Svensson, J.E. Pharmacokinetic analysis of intermittent rapamycin administration in early-stage Alzheimer’s Disease. GeroScience 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, I.; Hollenberg, M.D.; Ding, H.; Triggle, C.R. A Critical Review of the Evidence That Metformin Is a Putative Anti-Aging Drug That Enhances Healthspan and Extends Lifespan. Front. Endocrinol 2021, 12, 718942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Study Details | NCT02432287 | Metformin in Longevity Study (MILES). | ClinicalTrials.gov. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT02432287 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Kemper, C.; Behnam, D.; Brothers, S.; Wahlestedt, C.; Volmar, C.-H.; Bennett, D.; Hayward, M. Safety and pharmacokinetics of a highly bioavailable resveratrol preparation (JOTROL TM). AAPS Open 2022, 8, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smoliga, J.M.; Blanchard, O. Enhancing the Delivery of Resveratrol in Humans: If Low Bioavailability is the Problem, What is the Solution? Molecules 2014, 19, 17154–17172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapetanovic, I.M.; Muzzio, M.; Huang, Z.; Thompson, T.N.; McCormick, D.L. Pharmacokinetics, oral bioavailability, and metabolic profile of resveratrol and its dimethylether analog, pterostilbene, in rats. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2011, 68, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, M.; Girisa, S.; BharathwajChetty, B.; Vishwa, R.; Kunnumakkara, A.B. Curcumin Formulations for Better Bioavailability: What We Learned from Clinical Trials Thus Far? ACS Omega 2023, 8, 10713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajman, L.; Chwalek, K.; Sinclair, D.A. Therapeutic potential of NAD-boosting molecules: The in vivo evidence. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solnier, J.; Zhang, Y.; Roh, K.; Kuo, Y.C.; Du, M.; Wood, S.; Hardy, M.; Gahler, R.J.; Chang, C. A Pharmacokinetic Study of Different Quercetin Formulations in Healthy Participants: A Diet-Controlled, Crossover, Single- and Multiple-Dose Pilot Study. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2023, 2023, 9727539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Study Details | NCT05835999 | Everolimus Aging Study | ClinicalTrials.gov. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05835999 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Study Details | NCT06208527 | The NADage Study: Nicotinamide Riboside Replenishment Therapy Against Functional Decline in Aging | ClinicalTrials.gov. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06208527 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Study Details | NCT02921659 | Safety & Efficacy of Nicotinamide Riboside Supplementation for Improving Physiological Function in Middle-Aged and Older Adults | ClinicalTrials.gov. Available online: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT02921659 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Study Details | NCT04691986 | Impacts of Nicotinamide Riboside on Functional Capacity and Muscle Physiology in Older Veterans | ClinicalTrials.gov. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04691986 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Study Details | NCT04407390 | Effects of Nicotinamide Riboside on the Clinical Outcome of COVID-19 in the Elderly | ClinicalTrials.gov. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04407390 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Espinoza, S.E.; Khosla, S.; Baur, J.A.; De Cabo, R.; Musi, N. Drugs Targeting Mechanisms of Aging to Delay Age-Related Disease and Promote Healthspan: Proceedings of a National Institute on Aging Workshop. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2023, 78 (Suppl. S1), 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Liu, C.; Suliburk, J.; Hsu, J.W.; Muthupillai, R.; Jahoor, F.; Minard, C.G.; E Taffet, G.; Sekhar, R.V. Supplementing Glycine and N-Acetylcysteine (GlyNAC) in Older Adults Improves Glutathione Deficiency, Oxidative Stress, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Inflammation, Physical Function, and Aging Hallmarks: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2023, 78, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, R.E.; Laughlin, G.A.; LaCroix, A.Z.; Hartman, S.J.; Natarajan, L.; Senger, C.M.; Martínez, M.E.; Villaseñor, A.; Sears, D.D.; Marinac, C.R.; et al. Intermittent Fasting and Human Metabolic Health. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 115, 1203–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, E.W.; Most, J.; Mey, J.T.; Redman, L.M. Calorie Restriction and Aging in Humans. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2020, 40, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawamura, T.; Higuchi, M.; Radak, Z.; Taki, Y. Exercise as a geroprotector: Focusing on epigenetic aging. Aging 2025, 17, 1583–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattis, J.; Sehgal, A. Circadian Rhythms, Sleep, and Disorders of Aging. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 27, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odamaki, T.; Kato, K.; Sugahara, H.; Hashikura, N.; Takahashi, S.; Xiao, J.-Z.; Abe, F.; Osawa, R. Age-related changes in gut microbiota composition from newborn to centenarian: A cross-sectional study. BMC Microbiol. 2016, 16, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, A.; Romano, S.; Ansorge, R.; Aboelnour, A.; Le Gall, G.; Savva, G.M.; Pontifex, M.G.; Telatin, A.; Baker, D.; Jones, E.; et al. Fecal microbiota transfer between young and aged mice reverses hallmarks of the aging gut, eye, and brain. Microbiome 2022, 10, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, E.; Fabrizi, E.; Rivabene, R.; Cappella, M.; Fortini, P.; Conti, L.; Locuratolo, N.; Lorenzini, P.; Lacorte, E.; Piscopo, P. Human oral microbiome in aging: A systematic review. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2025, 226, 112080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, C.G.; Lowe, R.; Adams, P.D.; Baccarelli, A.A.; Beck, S.; Bell, J.T.; Christensen, B.C.; Gladyshev, V.N.; Heijmans, B.T.; Horvath, S.; et al. DNA methylation aging clocks: Challenges and recommendations. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antón-Fernández, A.; Ruiz de Alegría, Á.; Mariscal-Casero, A.; Roldán-Lázaro, M.; Peinado-Cauchola, R.; Ávila, J.; Hernández, F. Partial reprogramming by cyclical overexpression of Yamanaka factors improves pathological phenotypes of tauopathy mouse model of human Alzheimer’s disease. Prog. Neurobiol. 2025, 247, 102743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, B.; Correia, F.P.; Alves, I.A.; Costa, M.; Gameiro, M.; Martins, A.P.; Saraiva, J.A. Epigenetic reprogramming as a key to reverse ageing and increase longevity. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 95, 102204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Ji, X.; Leak, R.K.; Chen, F.; Cao, G. Stem cell therapies in age-related neurodegenerative diseases and stroke. Ageing Res. Rev. 2016, 34, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Ye, W.; Gao, Y.; Yi, Z.; Chen, Z.; Qu, C.; Huang, J.; Liu, F.; Liu, Z. Application of Organoids in Regenerative Medicine. Stem Cells 2023, 41, 1101–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooka, T. The Era of Preemptive Medicine: Developing Medical Digital Twins through Omics, IoT, and AI Integration. JMA J. 2025, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhavoronkov, A.; Bischof, E.; Lee, K.F. Artificial intelligence in longevity medicine. Nat. Aging 2021, 1, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, P.; Neill, M. Delivering on the promise of digital transformation. World Oil 2017, 238, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olshansky, S.J.; Kirkland, J.L. Geroscience and Its Promise. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2024, 14, a041725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, W.C. Medicalization of Aging: The Upside and the Downside. Marq. Elder’s Advis. 2011, 13, 55. Available online: https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/marqelad13&id=57&div=&collection= (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Kritchevsky, S.B.; Cummings, S.R. Geroscience: A Translational Review. JAMA 2025, 334, 1094–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, J.L. Biomarker development for translational geroscience: Considerations for a strategic framework focusing on early clinical development. Aging Cell 2023, 22, e13837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austad, S.N.; Fischer, K.E. Sex Differences in Lifespan. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarulli, V.; Barthold Jones, J.A.; Oksuzyan, A.; Lindahl-Jacobsen, R.; Christensen, K.; Vaupel, J.W. Women live longer than men even during severe famines and epidemics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E832–E840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tower, J. Sex-specific regulation of aging and apoptosis. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2006, 127, 705–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukiainen, T.; Villani, A.C.; Yen, A.; Rivas, M.A.; Marshall, J.L.; Satija, R.; Aguirre, M.; Gauthier, L.; Fleharty, M.; Kirby, A.; et al. Landscape of X chromosome inactivation across human tissues. Nature 2017, 550, 244–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsberg, L.A.; Rasi, C.; Malmqvist, N.; Davies, H.; Pasupulati, S.; Pakalapati, G.; Sandgren, J.; de Ståhl, T.D.; Zaghlool, A.; Giedraitis, V.; et al. Mosaic loss of chromosome Y in peripheral blood is associated with shorter survival and higher risk of cancer. Nat. Genet. 2014, 46, 624–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, E.L.B.; Richardson, D.S. Sex differences in telomeres and lifespan. Aging Cell. 2011, 10, 913–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teschendorff, A.E.; Horvath, S. Epigenetic ageing clocks: Statistical methods and emerging computational challenges. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2025, 26, 350–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silaidos, C.; Pilatus, U.; Grewal, R.; Matura, S.; Lienerth, B.; Pantel, J.; Eckert, G.P. Sex-associated differences in mitochondrial function in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and brain. Biol. Sex Differ. 2018, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, E. Estrogen Signaling and Cardiovascular Disease. Circ. Res. 2011, 109, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Khoudary, S.R.; Aggarwal, B.; Beckie, T.M.; Hodis, H.N.; Johnson, A.E.; Langer, R.D.; Limacher, M.C.; Manson, J.E.; Stefanick, M.L.; Allison, M.A.; et al. Menopause Transition and Cardiovascular Disease Risk: Implications for Timing of Early Prevention: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020, 142, E506–E532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittert, G.; Bracken, K.; Robledo, K.P.; Grossmann, M.; Yeap, B.B.; Handelsman, D.J.; Stuckey, B.; Conway, A.; Inder, W.; McLachlan, R.; et al. Testosterone treatment to prevent or revert type 2 diabetes in men enrolled in a lifestyle programme (T4DM): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 2-year, phase 3b trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021, 9, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallis, C.J.D.; Lo, K.; Lee, Y.; Krakowsky, Y.; Garbens, A.; Satkunasivam, R.; Herschorn, S.; Kodama, R.T.; Cheung, P.; A Narod, S.; et al. Survival and cardiovascular events in men treated with testosterone replacement therapy: An intention-to-treat observational cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016, 4, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.L.; Flanagan, K.L. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 626–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Márquez, E.J.; Chung, C.; Marches, R.; Rossi, R.J.; Nehar-Belaid, D.; Eroglu, A.; Mellert, D.J.; Kuchel, G.A.; Banchereau, J.; Ucar, D. Sexual-dimorphism in human immune system aging. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peckham, H.; de Gruijter, N.M.; Raine, C.; Radziszewska, A.; Ciurtin, C.; Wedderburn, L.R.; Rosser, E.C.; Webb, K.; Deakin, C.T. Male sex identified by global COVID-19 meta-analysis as a risk factor for death and ITU admission. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 6317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Women Live Longer than Men in Every Country in the World-Our World in Data. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/data-insights/women-live-longer-than-men-in-every-country-in-the-world (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Park, C.; Ko, F.C. The Science of Frailty: Sex differences. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2021, 37, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merz, A.A.; Cheng, S. Sex differences in cardiovascular ageing. Heart 2016, 102, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Wang, B.; Alu, A.; Hong, W.; Lei, H.; He, X.; Shi, H.; Cheng, P.; Yang, X. Immunosenescence: Signaling pathways, diseases and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, A.; Accardi, G.; Aiello, A.; Caruso, C.; Candore, G. Sex and gender affect immune aging. Front. Aging 2023, 4, 1272118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aphkhazava, D.; Gabisonia, G.; Migriauli, I.; Chakhnashvili, K.; Bedinashvili, Z.; Jangavadze, M. Advances in Rejuvenation Research: Molecular Mechanisms and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies. Transl. Clin. Med.-Georg. Med. J. 2025, 10, 51–58. Available online: https://www.tcm.tsu.ge/index.php/TCM-GMJ/article/view/580 (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Rachakatla, A.; Kalashikam, R.R. Calorie Restriction-Regulated Molecular Pathways and Its Impact on Various Age Groups: An Overview. DNA Cell Biol. 2022, 41, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofer, S.J.; Carmona-Gutierrez, D.; Mueller, M.I.; Madeo, F. The ups and downs of caloric restriction and fasting: From molecular effects to clinical application. EMBO Mol. Med. 2021, 14, e14418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Cho, M.K.; Chung, Y.-J.; Hong, S.-H.; Hwang, K.R.; Jeon, G.-H.; Kil Joo, J.; Kim, S.K.; Lee, D.O.; Lee, D.-Y.; et al. The 2025 Menopausal Hormone Therapy Guidelines-Korean Society of Menopause. J. Menopausal Med. 2025, 31, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manson, J.A.E.; Chlebowski, R.T.; Stefanick, M.L.; Aragaki, A.K.; Rossouw, J.E.; Prentice, R.L.; Anderson, G.L.; Howard, B.V.; Thomson, C.A.; Lacroix, A.Z.; et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA 2013, 310, 1353–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaeberlein, M.; Rabinovitch, P.S.; Martin, G.M. Healthy aging: The ultimate preventative medicine. Science 2015, 350, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroemer, G.; Maier, A.B.; Cuervo, A.M.; Gladyshev, V.N.; Ferrucci, L.; Gorbunova, V.; Kennedy, B.K.; Rando, T.A.; Seluanov, A.; Sierra, F.; et al. From geroscience to precision geromedicine: Understanding and managing aging. Cell 2025, 188, 2043–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TAME-Targeting Aging with Metformin-American Federation for Aging Research. Available online: https://www.afar.org/tame-trial (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Macip, C.C.; Hasan, R.; Hoznek, V.; Kim, J.; Lu, Y.R.; Metzger, L.E.; Sethna, S.; Davidsohn, N. Gene Therapy-Mediated Partial Reprogramming Extends Lifespan and Reverses Age-Related Changes in Aged Mice. Cell. Reprogram. 2024, 26, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Model Organism | Key Characteristics | Main Uses in Aging Research |

|---|---|---|

| Yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) | Very short replicative lifespan; easy genetic manipulation; conserved TOR & sirtuin pathways | Discovery of nutrient-sensing pathways (TOR, sirtuins); high-throughput drug screening |

| Nematode (C. elegans) | ~20 days lifespan; ~60% gene homology with humans; transparent body | Identification of >400 longevity genes; stress resistance; senotherapeutic screening |

| Drosophila (D. melanogaster) | Lifespan ~60–80 days; powerful genetics; well-mapped organs | Indy gene longevity models; neural senescence studies; metabolic regulation |

| Fish (Killifish, Zebrafish, Axolotl) | Killifish lifespan 3–6 months; transparent zebrafish embryos; axolotl regeneration | Rapid drug testing; vertebrate regeneration models; transient senescence in repair |

| Rodents (mice, rats) | Lifespan 2–3 years; advanced genetic tools; disease models | Caloric restriction; rapamycin studies; GH/IGF-1 modulation; senescence clearance; frailty models |

| Swine (mini-pigs) | Strong physiological similarity to humans; cardiovascular & metabolic resemblance | Atherosclerosis & metabolic aging models; cardiovascular aging; translational testing of interventions |

| Non-human primates (macaques, marmosets) | High similarity to human physiology; age-related pathologies | Long-term CR studies; immune/metabolic aging; preclinical translational research |

| Human stem-cell–derived organoids | 3D human-specific tissues modeling aging features (stem-cell exhaustion, mitochondrial dysfunction, DNA damage) | High capture human aging signatures better than animal models |

| Molecule/Intervention | ClinicalTrials.Gov ID (NCT) | Description/Status | Main Findings/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rapalogues (Everolimus–mTORC1) | NCT05835999 | EVERLAST–safety and anti-aging effects (24 weeks, ongoing) | Awaiting results; focus on immunosenescence and safety. |

| Metformin | NCT02432287 | MILES—biomarkers of aging (completed, preliminary results) | Transcriptomic shifts consistent with anti-aging; no definitive clinical outcomes yet. |

| NAD+ boosters (NR, NMN) | NCT06208527, NCT02921659, NCT04691986, NCT04407390 | NADage and others—frailty, NAD+ metabolism, muscle function (ongoing) | Early data suggest improved vascular/muscle function; modest overall effects. |

| Senolytics (Dasatinib + Quercetin) | NCT04313634, NCT04946383, NCT04733534, NCT05422885 | Cellular senescence, epigenetics, physical function (ongoing) | Pilot study in IPF showed improved function; mixed outcomes in OA. |

| GlyNAC (Glycine + NAC) | NCT01870193 | Pilot RCT—glutathione, oxidative stress, mitochondrial function (completed, promising results) | J Gerontol A 2022: improved GSH, mitochondrial function, inflammation, cognition, strength. |

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Digital biomarker profiling & wearable phenotyping | Acquisition of continuous physiological, behavioral, and functional data through wearables, sensors, and smartphone-based monitoring. |

| 2. Multi-omic & functional stratification | Integration of genomics, epigenomics, metabolomics, proteomics, and functional tests to classify individuals into biologically meaningful risk/aging clusters. |

| 3. Personalized combination therapy | Selection and implementation of multi-target interventions (senolytics, metabolic modulators, NAD+ boosters, lifestyle therapies) tailored to the individual profile. |

| 4. AI-assisted monitoring & adaptive adjustment | Real-time tracking of responses with algorithm-driven adjustment of dosages, combinations, or timing based on predictive analytics. |

| 5. Long-term evaluation & clinical outcomes | Assessment of safety, adherence, functional improvements, and reduction in biological age trajectories using integrated digital platforms. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nicoletti, G.R.P.; Mangano, K.; Nicoletti, F.; Cavalli, E. From Elixirs to Geroscience: A Historical and Molecular Perspective on Anti-Aging Medicine. Molecules 2025, 30, 4728. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244728

Nicoletti GRP, Mangano K, Nicoletti F, Cavalli E. From Elixirs to Geroscience: A Historical and Molecular Perspective on Anti-Aging Medicine. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4728. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244728

Chicago/Turabian StyleNicoletti, Giuseppe Rosario Pietro, Katia Mangano, Ferdinando Nicoletti, and Eugenio Cavalli. 2025. "From Elixirs to Geroscience: A Historical and Molecular Perspective on Anti-Aging Medicine" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4728. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244728

APA StyleNicoletti, G. R. P., Mangano, K., Nicoletti, F., & Cavalli, E. (2025). From Elixirs to Geroscience: A Historical and Molecular Perspective on Anti-Aging Medicine. Molecules, 30(24), 4728. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244728