Current Research on MoS2-Based Heterojunction Photocatalysts for Persistent Organic Pollutants Degradation

Abstract

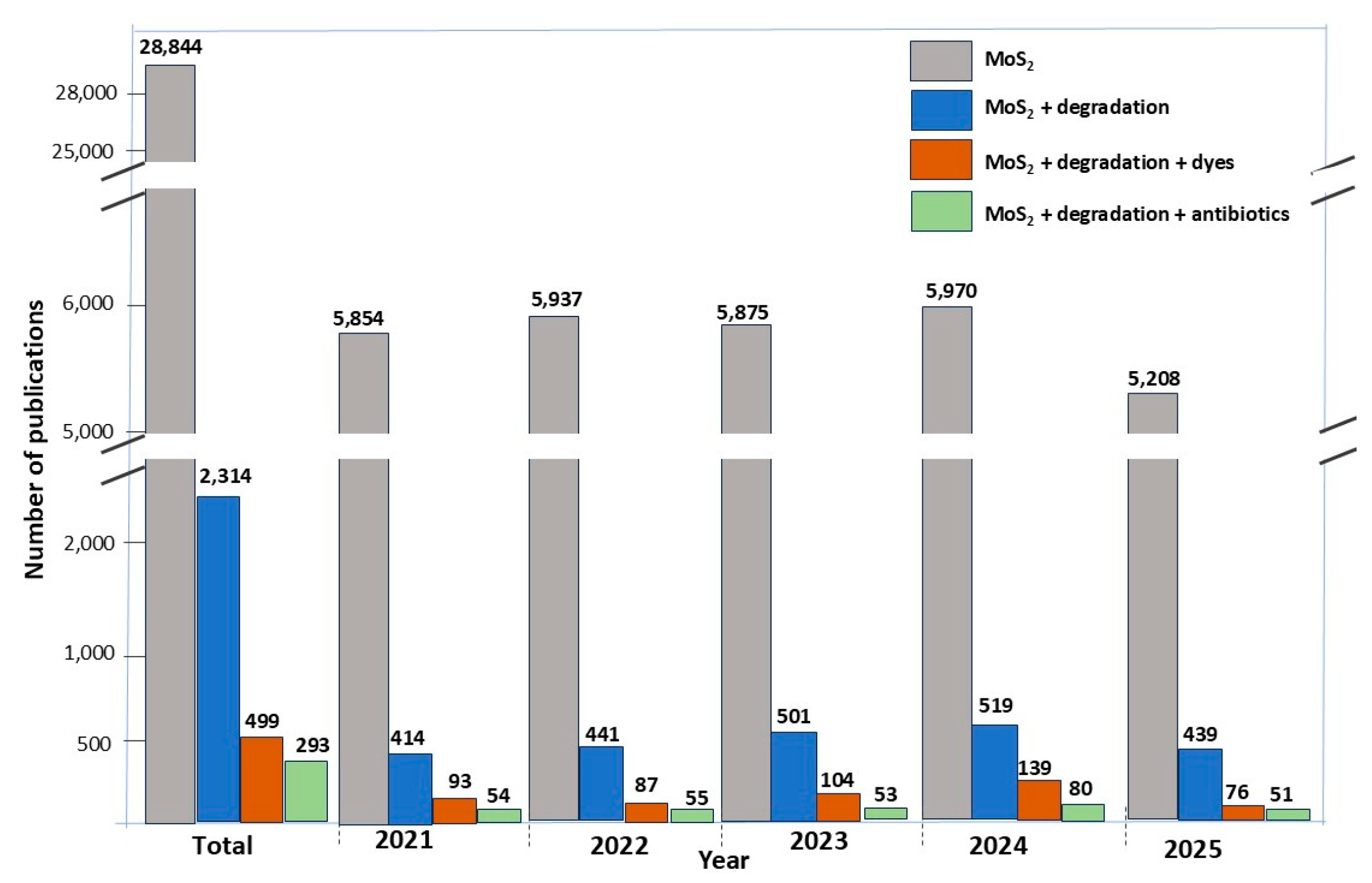

1. Introduction

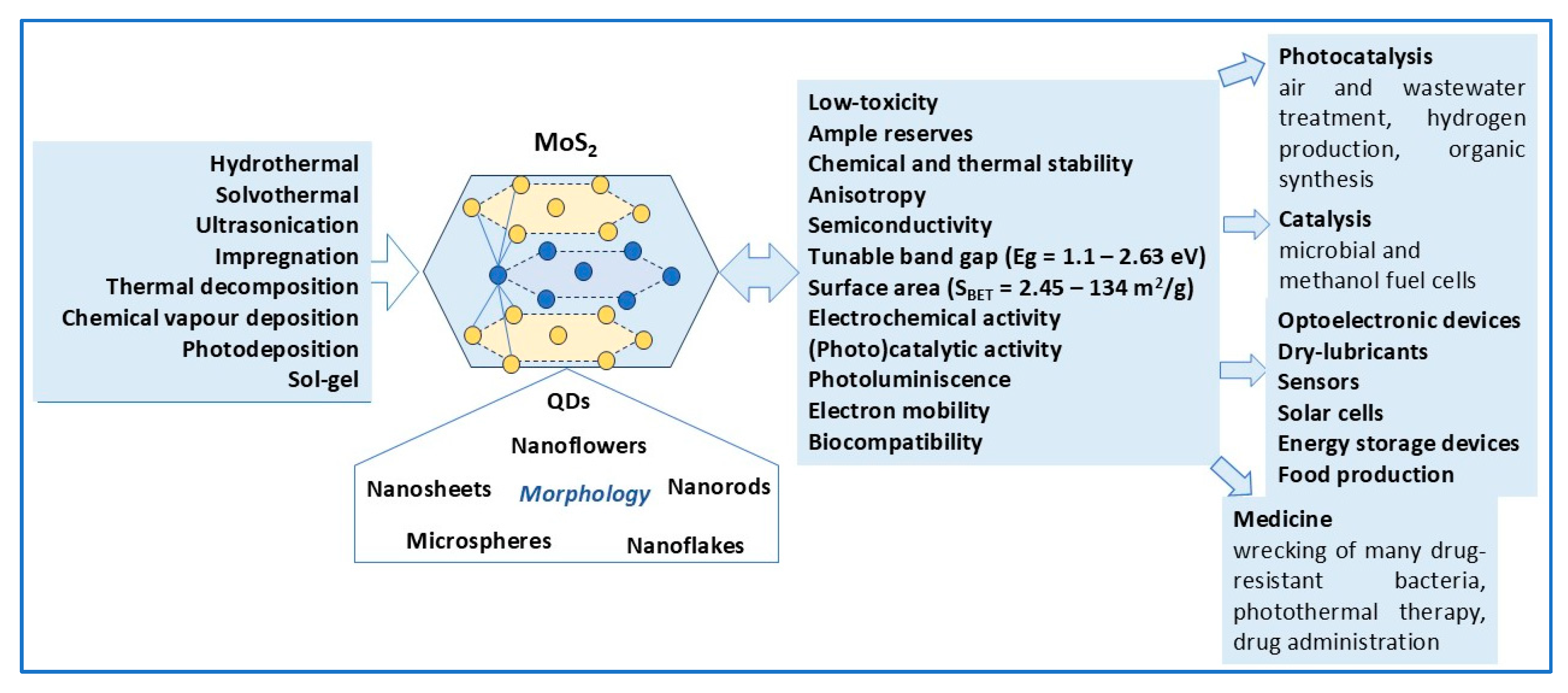

2. MoS2 as Photocatalyst

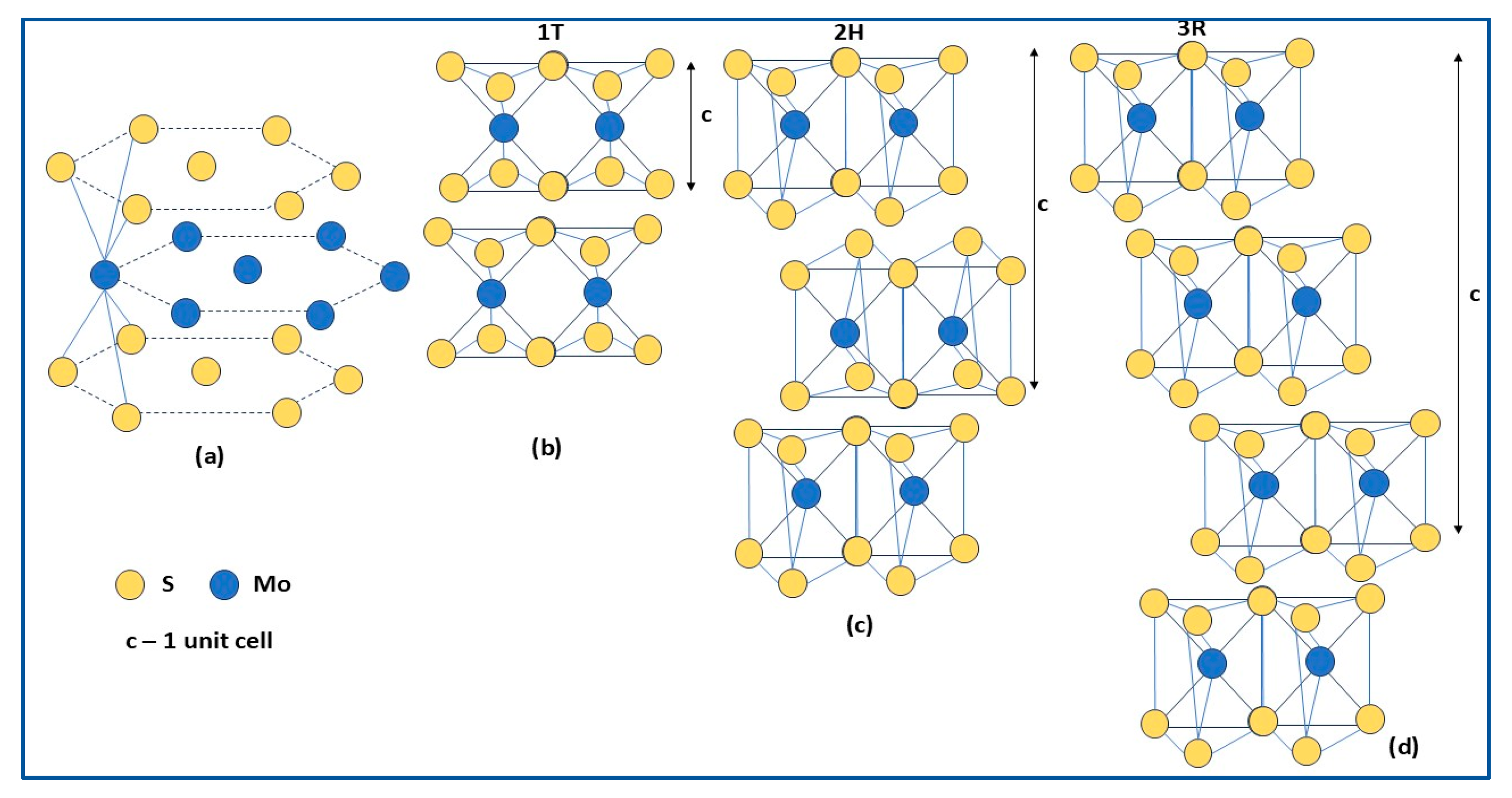

2.1. Structure

- 1T-MoS2, with a metastable octahedral structure composed of one S–Mo–S layer per unit cell, where Mo is exposed on the surface (Figure 1b); it could be stabilized by doping or by hybrid structures formation; it shows electrical behavior and relative hydrophilicity, therefore, it is more suitable for hydrogen production [48];

2.2. Morphology

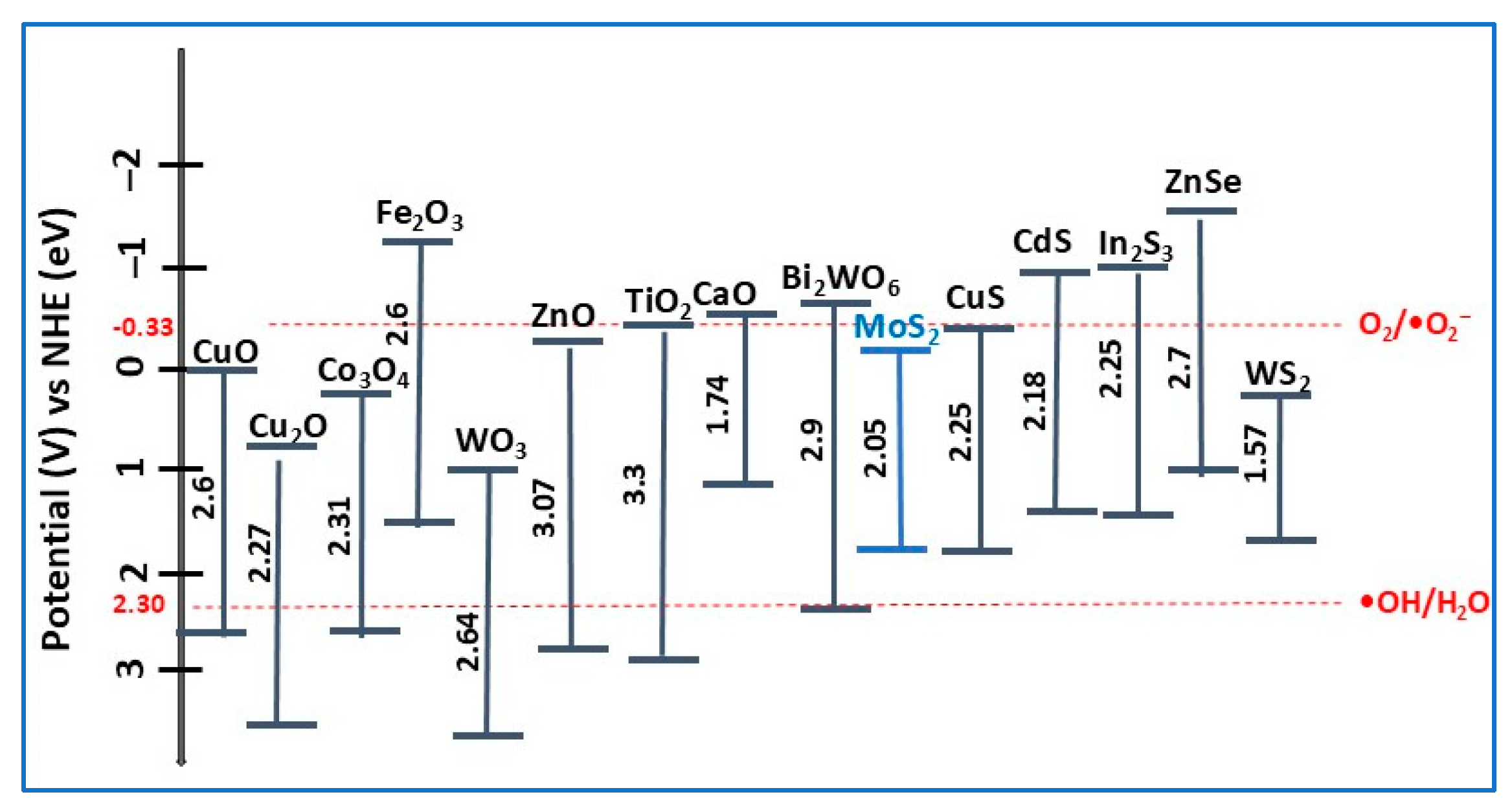

2.3. Electronic Properties

2.4. Optical Properties

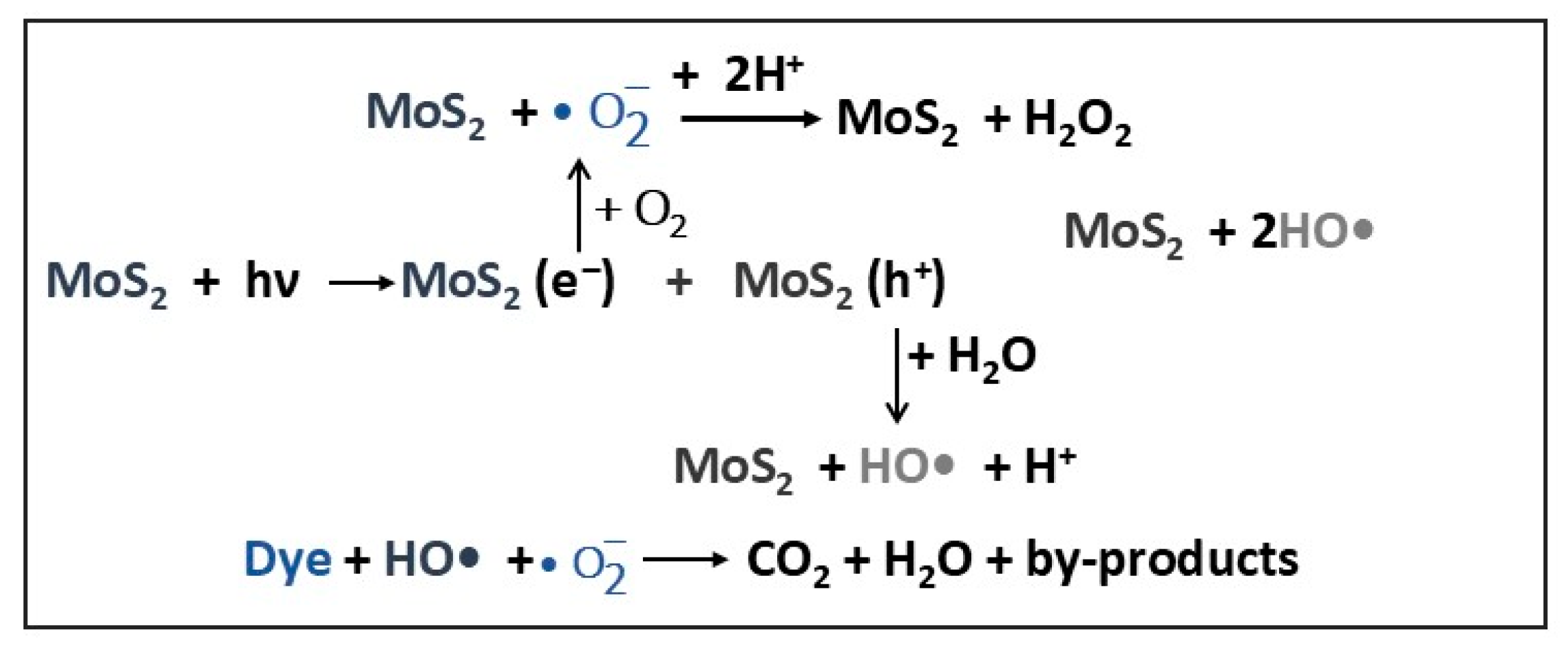

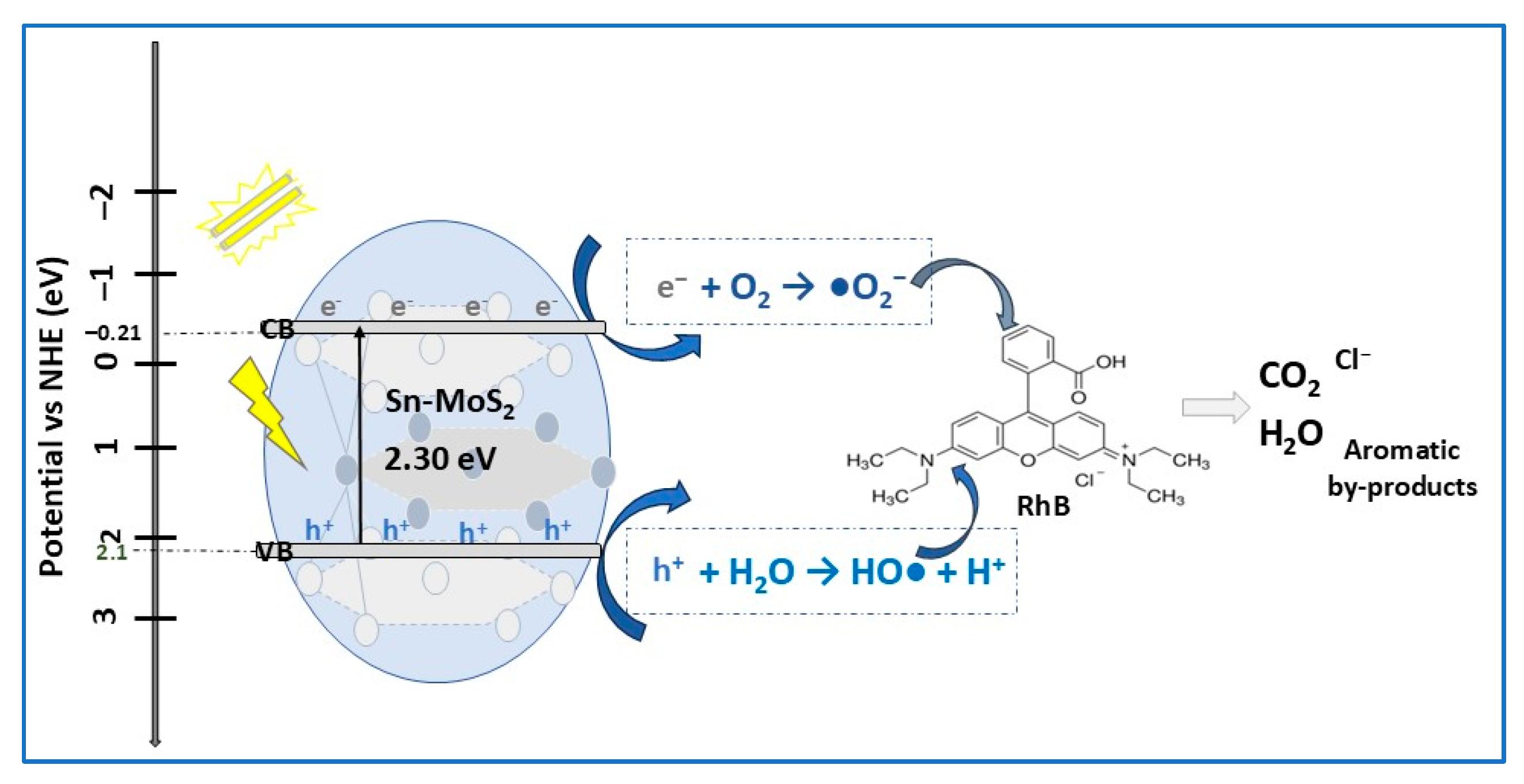

2.5. MoS2 and Metal-Doped MoS2 Photocatalysts

3. MoS2-Based Heterojunction Photocatalysts

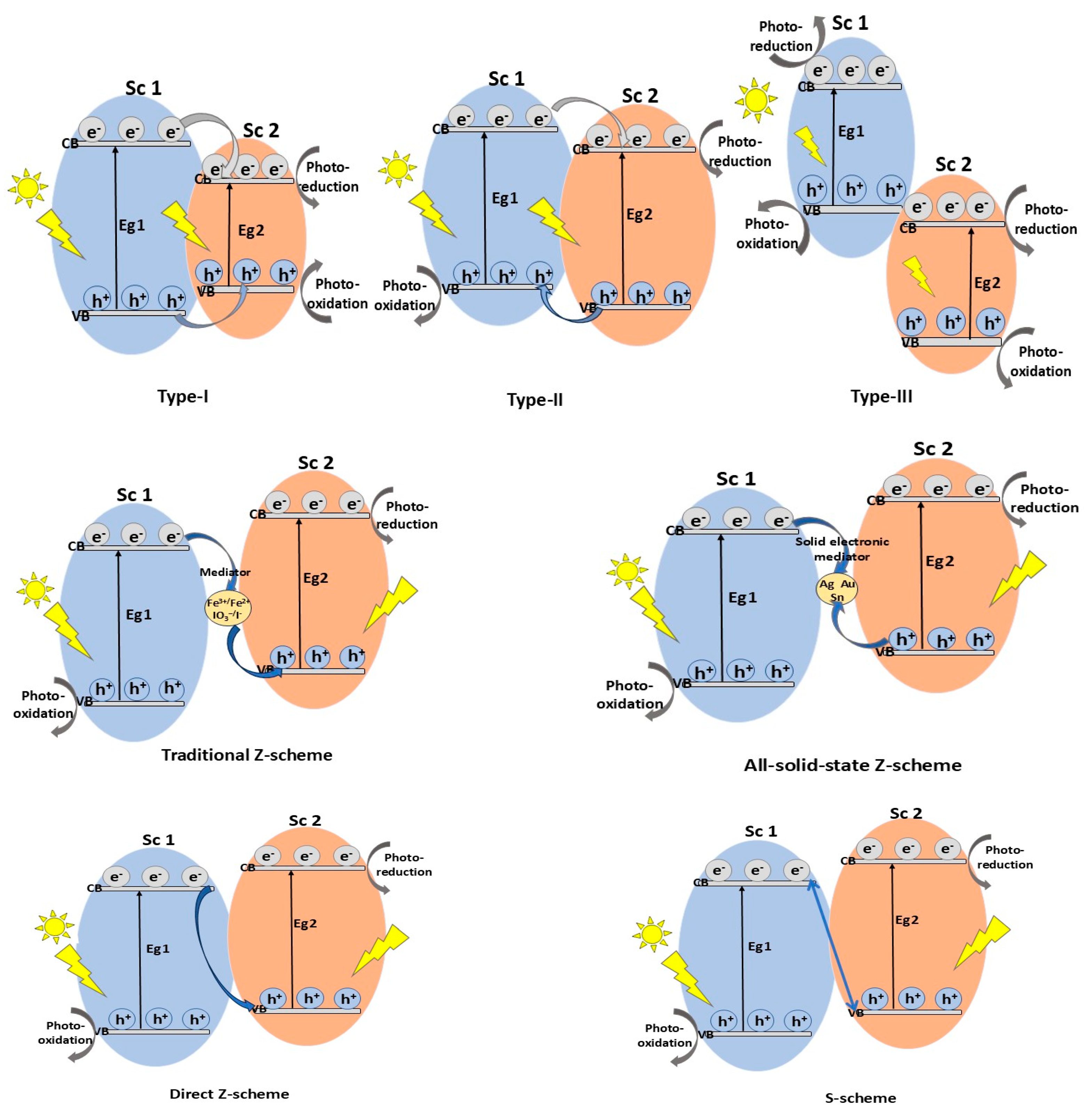

- Type-I heterojunction, with straddling bandgaps in which charge carriers transfer results in redox reactions occurring at the same semiconductor (Sc 2);

- Type-II heterojunction, with staggered bandgaps in which the CB and VB positions are at optimal levels, thus ensuring spatial charge carrier separation, enhancing photocatalytic performance compared to type-I; the oxidation and reduction reactions take place on Sc 1, with lower oxidation potential;

- Type-III heterojunction, with broken bandgaps in which there are no synergistic interactions between electrons and holes that would cause the separation of lower charge carriers, resulting in not thermodynamically favorable and stable photocatalytic reactions occurring compared with the type-II heterojunction.

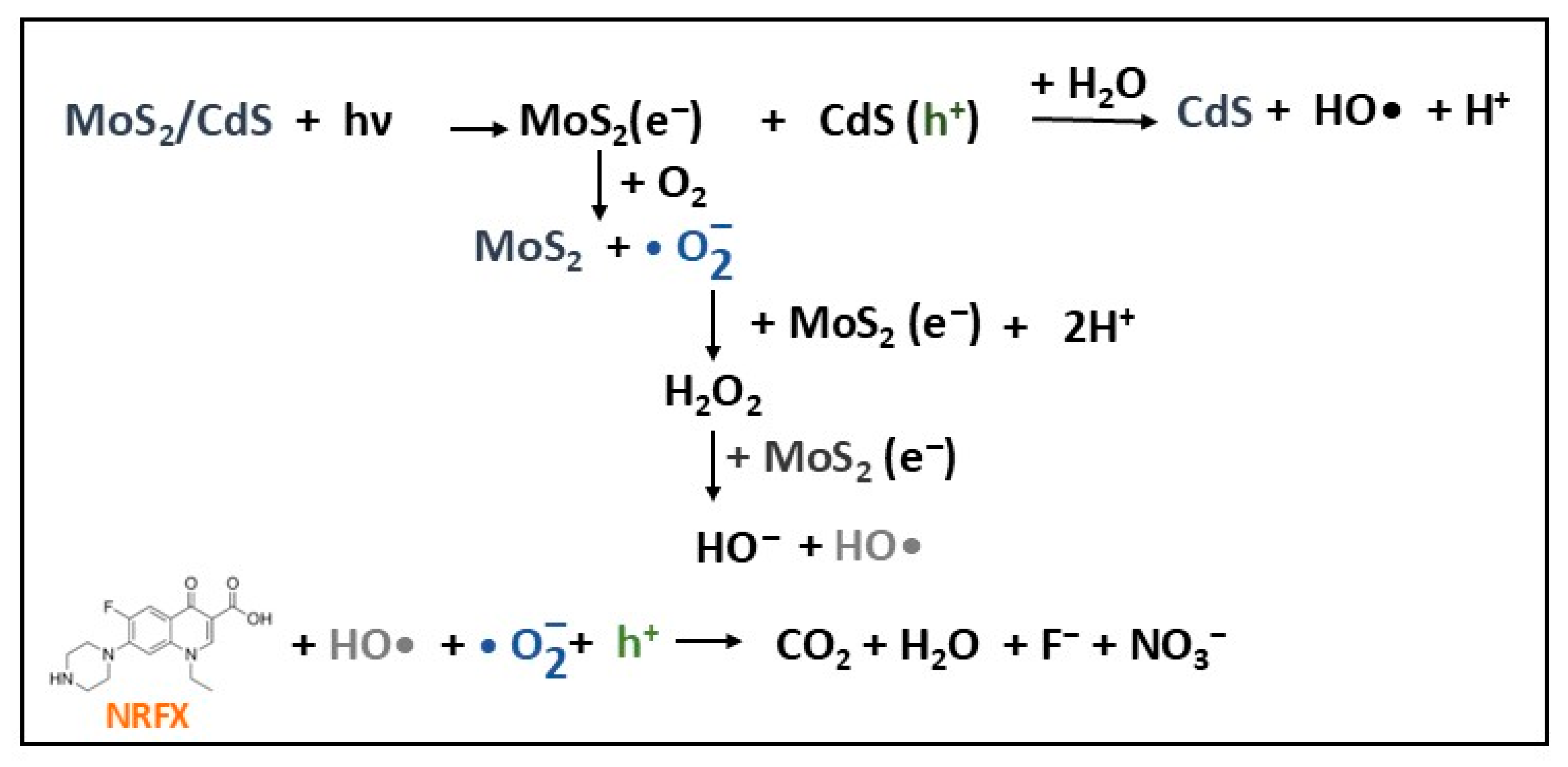

3.1. Binary MoS2-Based Heterojunction Photocatalysts

3.1.1. Type-I MoS2-Based Heterojunction Photocatalysts

3.1.2. Type-II MoS2-Based Heterojunction Photocatalysts

3.1.3. Z-Scheme MoS2-Based Heterojunction Photocatalysts

3.1.4. S-Scheme MoS2-Based Heterojunction Photocatalysts

3.2. Ternary MoS2-Based Heterojunction Photocatalysts

4. Current Challenges and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CR | Congo Red | 9-AC | 9-Anthracene Carboxylic acid |

| AZR | Alizarin Red | HQ | Hydroquinone |

| CTC | Chlortetracycline | Mt | Montmorillonite |

| CIP | Ciprofloxacin | SubPc-Br | Subphthalocyanine bromide |

| LF | Levofloxacin | PPy | Polypyrrole |

| DCF | Diclofenac | BC | Biochar |

| TBC | Thiobencarb |

References

- Zhang, X.; Suo, H.; Zhang, R.; Niu, S.; Zhao, X.Q.; Zheng, J.; Guo, C. Photocatalytic activity of 3D flower-like MoS2 hemispheres. Mater. Res. Bull. 2018, 100, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawari, D.; Pandit, V.; Jawale, N.; Kamble, P. Layered MoS2 for photocatalytic dye degradation. Mater Today Proc. 2022, 53, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandigana, P.; Mahato, S.; Dhandapani, M.; Pradhan, B.; Subramanian, B.; Panda, S.K. Lyophilized tin-doped MoS2 as an efficient photocatalyst for overall degradation of Rhodamine B dye. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 907, 164470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

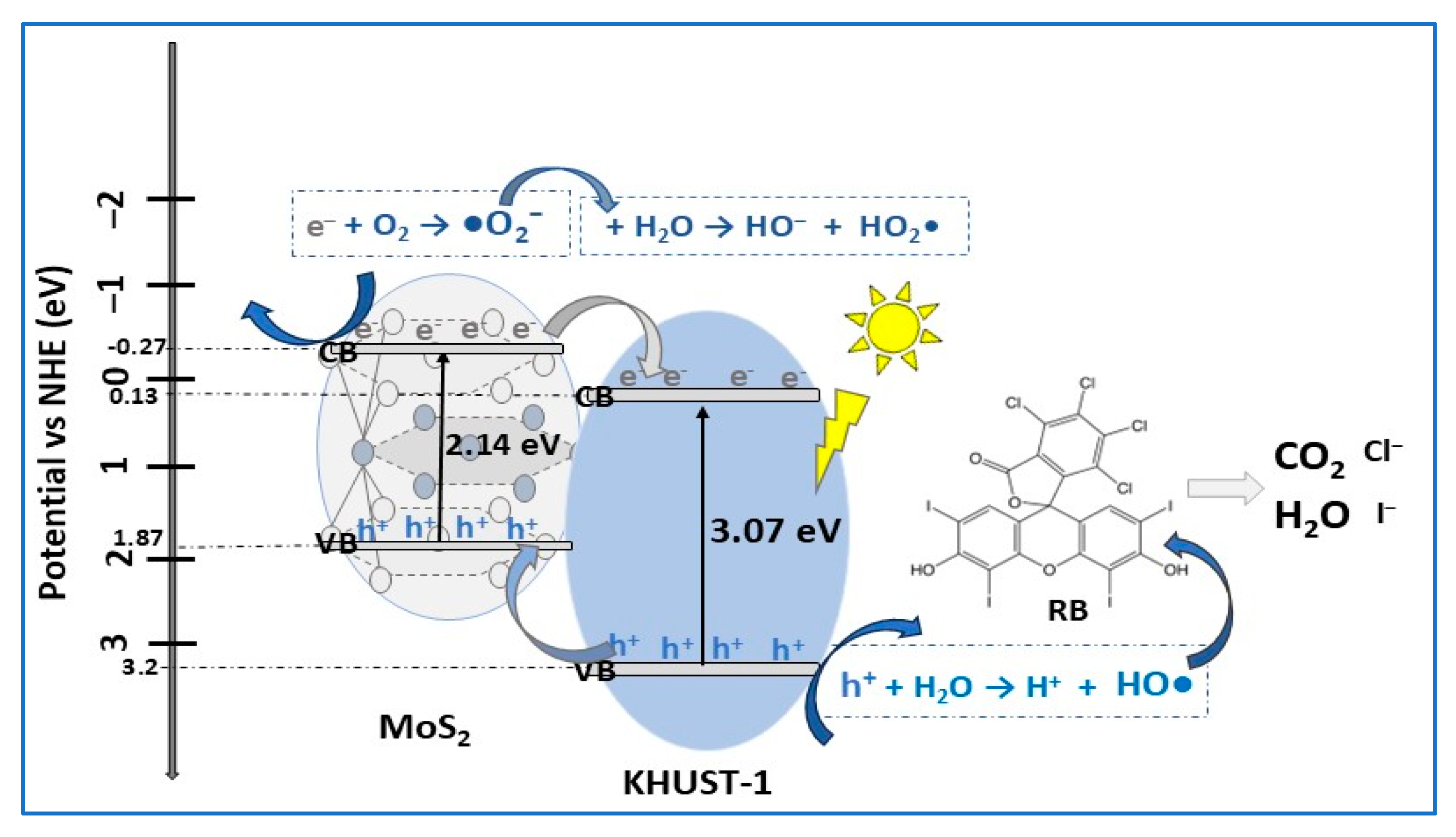

- Roy, S.; Darabdhara, I.; Ahmaruzzaman, M.d. MoS2 Nanosheets@Metal organic framework nanocomposite for enhanced visible light degradation and reduction of hazardous organic contaminants. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 430, 139517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Iqbal, T.; Mansha, M.S.; Riaz, K.N.; Nabi, G.; Sayed, M.A.; Abd El-Rehim, A.F.; Ali, A.M.; Afsheen, S. Synthesis and characterization of surfactant assisted MoS2 for degradation of industrial pollutants. Opt. Mater. 2022, 133, 113033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.-E.; Kim, M.-K.; Danish, M.; Jo, W.-K. State-of-the-art review on photocatalysis for efficient wastewater treatment: Attractive approach in photocatalyst design and parameters affecting the photocatalytic degradation. Catal. Commun. 2023, 183, 106764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Chen, C.; Tsai, H.; Shaya, J.; Lu, C. Photocatalytic degradation of thiobencarb by a visible light-driven MoS2 photocatalyst. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2018, 197, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikram, M.; Khan, M.I.; Raza, A.; Imran, M.; Ul-Hamid, A.; Ali, S. Outstanding performance of silver-decorated MoS2 nanopetals used as nanocatalyst for synthetic dye degradation. Phys. E 2020, 124, 11424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

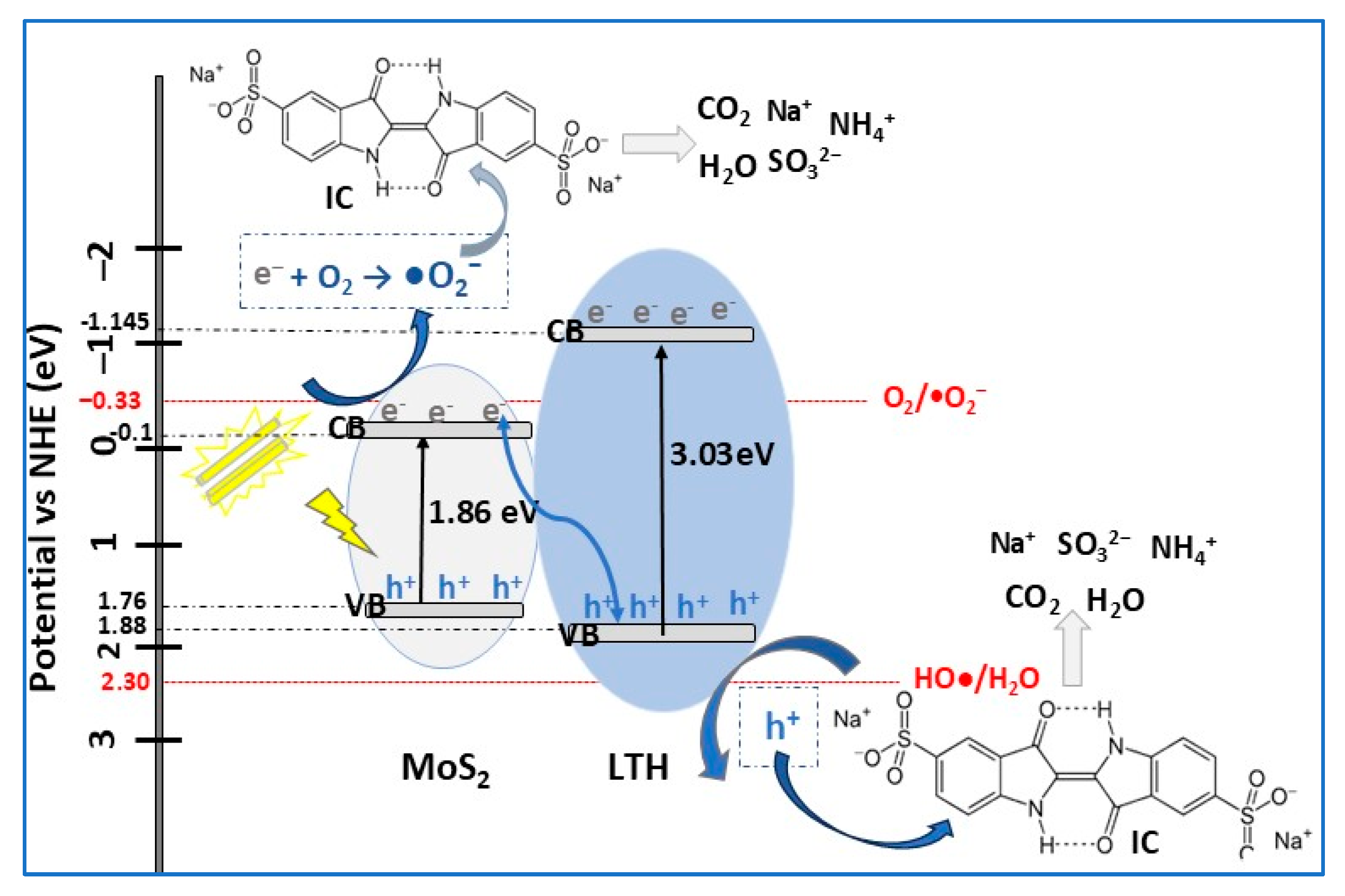

- Kim, C.-M.; Chowdhury, M.F.; Im, H.R.; Cho, K.; Jang, A. NiAlFe LTH /MoS2 p-n junction heterostructure composite as an effective visible-light-driven photocatalyst for enhanced degradation of organic dye under high alkaline conditions. Chemosphere 2024, 358, 142094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaranjani, P.R.; Janani, B.; Thomas, A.M.; Raju, L.L.; Khan, S.S. Recent development in MoS2-based nano-photocatalyst for the degradation of pharmaceutically active compounds. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 352, 131506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, J.; Tarale, P.; Sivanesan, S.; Bafana, A. Environmental persistence, hazard, and mitigation challenges of nitroaromatic compounds. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 28650–28667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishat, A.; Yusuf, M.; Qadir, A.; Ezaier, Y.; Vambol, V.; Khan, M.I.; Moussa, S.B.; Kamyab, H.; Sehgal, S.S.; Prakash, C.; et al. Wastewater treatment: A short assessment on available techniques. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 76, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

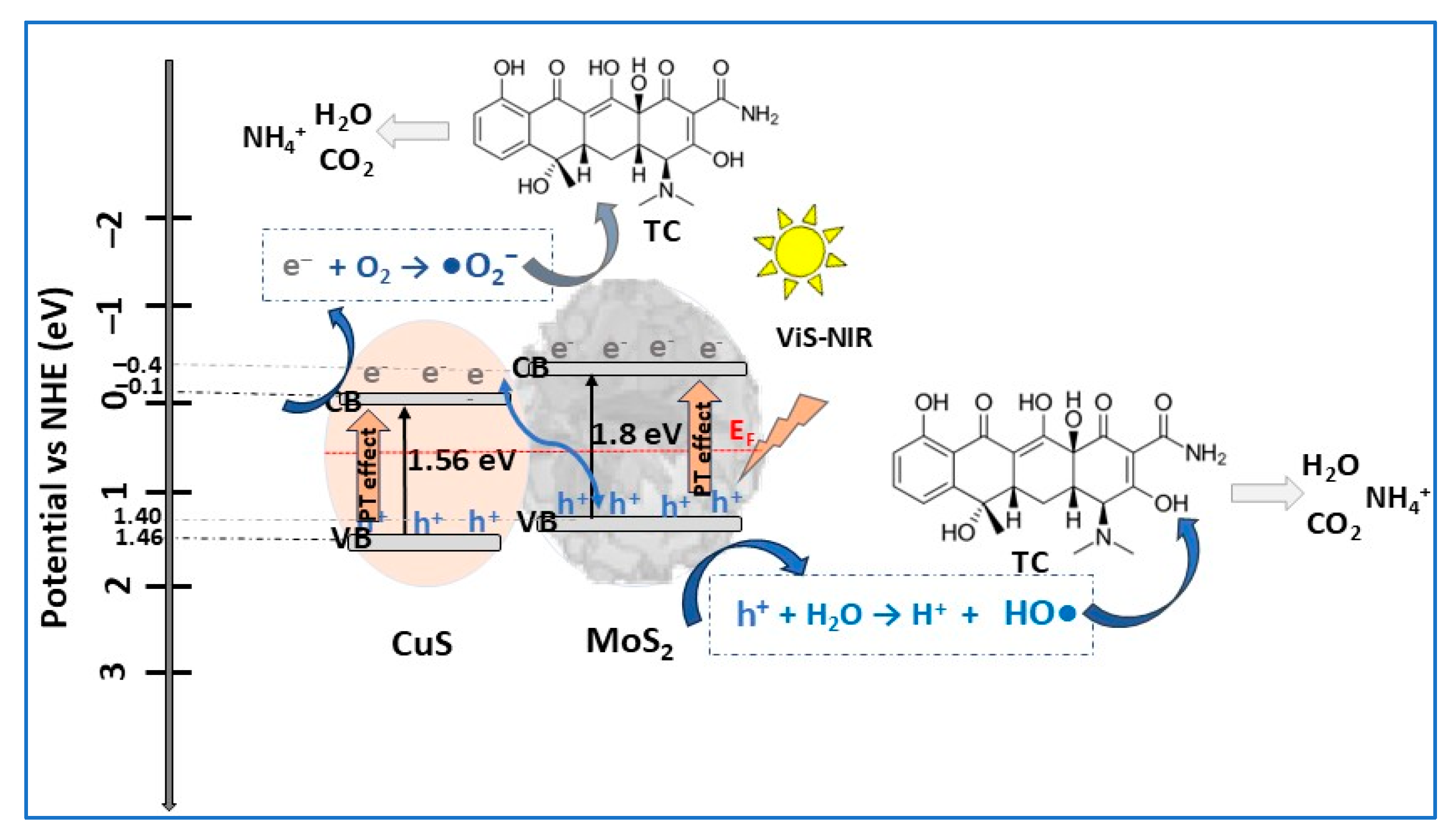

- Tran, V.-T.; Chen, D.-H. CuS@MoS2 pn heterojunction photocatalyst integrating photothermal and piezoelectric enhancement effects for tetracycline degradation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrkhah, R.; Park, S.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, B.H. A comparative study of advanced oxidation-based hybrid technologies for industrial wastewater treatment: An engineering perspective. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2024, 286, 119675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khader, E.H.; Mohammed, T.J.; Albayati, T.M.; Harharah, H.N.; Amari, A.; Saady, N.M.C.; Zendehboudi, S. Current trends for wastewater treatment technologies with typical configurations of photocatalytic membrane reactor hybrid systems: A review. Chem. Eng. Process 2023, 192, 109503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.V.P.; Shankar, K.R. Next-generation hybrid technologies for the treatment of pharmaceutical industry effluents. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 353, 120197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniyandi, G.R.; Mahalingam, S.; Gnanarani, S.V.; Jayashree, C.; Ganeshraja, A.S.; Pugazhenthiran, N.; Rahaman, M.; Abinaya, S.; Senthil, B.; Kim, J. TiO2 nanorod decorated with MoS2 nanospheres: An efficient dual-functional photocatalyst for antibiotic degradation and hydrogen production. Chemosphere 2024, 357, 142033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K.H.; Hamza, M.; Lai, S.Y.; Imanuella, N.; Tan, L.S.; Liu, C.-L.; Wu, H.-T. Unravelling the promotional roles of MoS2 in enhancing photo-activity of ZnCdS for photo-treatment of wastewater containing tetracycline (TC). Environ. Res. 2025, 275, 121402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beil, S.B.; Bonnet, S.; Casadevall, C.; Detz, R.J.; Eisenreich, F.; Glover, S.D.; Kerzig, C.; Næsborg, L.; Pullen, S.; Storch, G.; et al. Challenges and Future Perspectives in Photocatalysis: Conclusions from an Interdisciplinary Workshop. JACS Au 2024, 4, 2746−2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wang, K.; Li, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y. Strategies for optimizing the efficiency and selectivity of photocatalytic aqueous CO2 reduction: Catalyst design and operating conditions. Nano Energy 2025, 133, 110460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, S.; Li, Z.; Liu, C.; Miao, R.; He, G.; Zhao, M.; Xue, J.; Xia, Z.; Wang, Y.; et al. Hydrothermal synthesis of MoS2 nanosheet loaded TiO2 nanoarrays for enhanced visible light photocatalytic applications. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, U.; Sinha, I.; Mishra, T. Synthesis and photocatalytic evaluation of 2D MoS2/TiO2 heterostructure photocatalyst for organic pollutants degradation. Mater Today Proc. 2024, 112, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Chuang, Y.; Chen, C.-W.; Dong, C.-D. Facile synthesis of MoS2/ZnO quantum dots for enhanced visible-light photocatalytic performance and antibacterial applications. Nano-Struct. Nano-Objects 2022, 30, 100873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, R.; Ali, M.E.M.; Gomaa, E.; Mohsen, M. Promising MoS2—ZnO hybrid nanocomposite photocatalyst for antibiotics, and dyes remediation in wastewater applications. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2023, 19, 100772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmadi, N.; Mohamed, R.M. Construction of MoS2/WO3 S-scheme heterojunction photocatalyst for rapid reduction of Cr(VI) under visible illumination. Opt. Mater. 2025, 159, 116603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

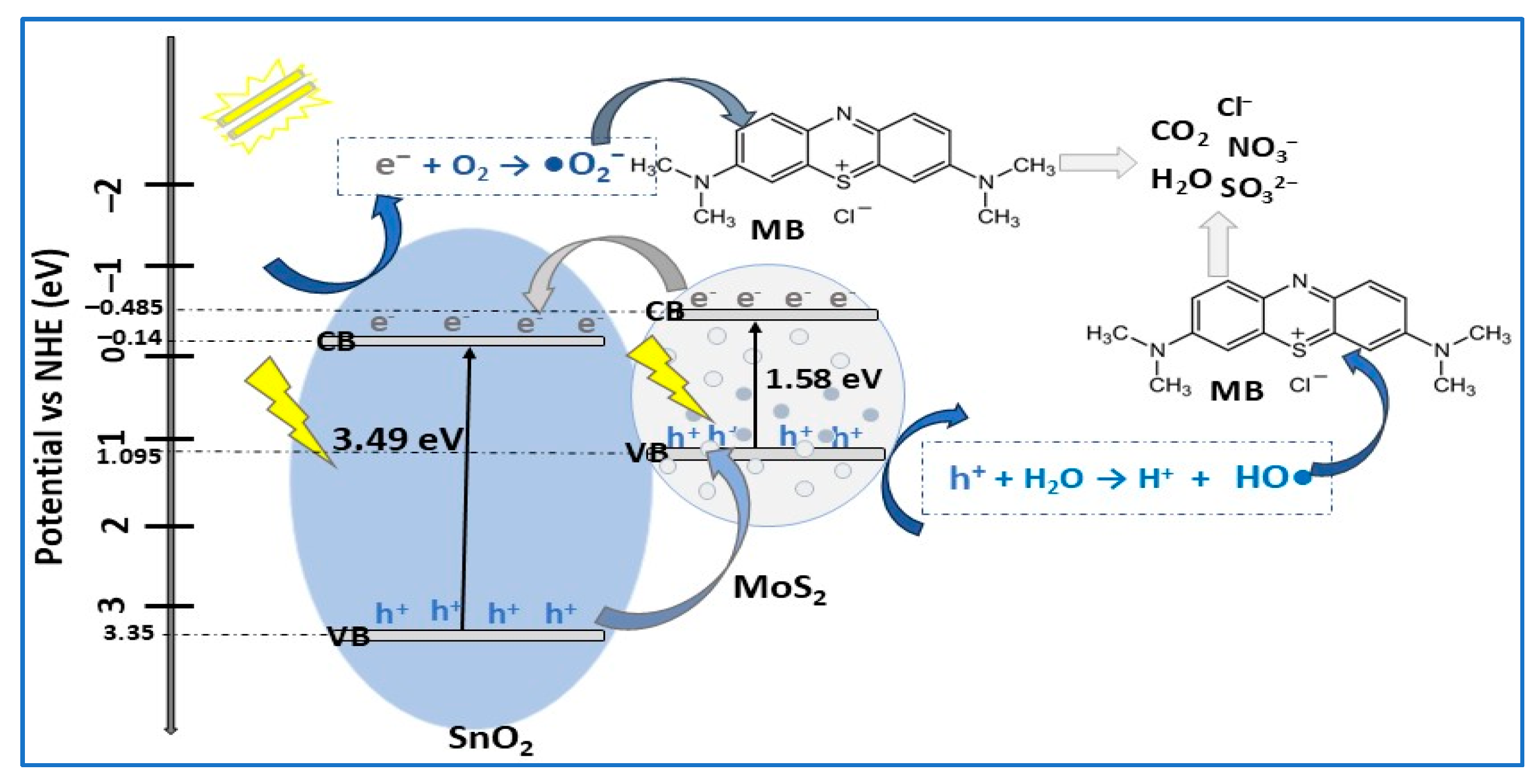

- Szkoda, M.; Zarach, Z.; Nadolska, M.; Trykowski, G.; Trzciński, K. SnO2 nanoparticles embedded onto MoS2 nanoflakes—An efficient catalyst for photodegradation of methylene blue and photoreduction of hexavalent chromium. Electrochim. Acta 2022, 414, 140173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isac, L.; Enesca, A. Recent Developments in ZnS-Based Nanostructures Photocatalysts for Wastewater Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isac, L.; Cazan, C.; Andronic, L.; Enesca, A. CuS-Based Nanostructures as Catalysts for Organic Pollutants Photodegradation. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.-L.; Han, S.-R.; Li, L.-L. CdS@MoS2 core@shell nanorod heterostructures for efficient photocatalytic pollution degradation with good stability. Optik 2020, 220, 165252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Kar, S.; Pal, T.; Ghosh, S. MoS2–CdS composite photocatalyst for enhanced degradation of norfloxacin antibiotic with improved apparent quantum yield and energy consumption. Phys. Chem. Solids 2024, 193, 112144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Qaydi, M.; Rajput, N.S.; Lejeune, M.; Bouchalkha, A.; El Marssi, M.; Cordette, S.; Kasmi, C.; Jouiad, M. Intermixing of MoS2 and WS2 photocatalysts toward methylene blue photodegradation. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2024, 15, 817–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Soni, R.K. Enhanced sunlight driven photocatalytic activity of In2S3 nanosheets functionalized MoS2 nanoflowers heterostructures. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 15352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazneen, A.; Khan, M.I.; Naeem, M.A.; Atif, M.; Iqbal, M.; Yaqub, N.; Farooq, W.A. Structural, morphological, optical, and photocatalytic properties of Ag-doped MoS2 nanoparticles. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1220, 128735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, J.S.; Dugas, G.; Morency, S.; Messaddeq, Y. Rapid degradation of Rhodamine B using enhanced photocatalytic activity of MoS2 nanoflowers under concentrated sunlight irradiation. Phys. E 2020, 120, 114114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathishkumar, M.; Anitha, A.; Ponmurugan, P.; Arunkumar, D.; Esath Natheer, S.; Kannan, S. Oxytetracycline degradation and antidermatophytic activity of novel biosynthesized MoS2 photocatalysts. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2024, 301, 117164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Tsai, M.-L.; Chuang, Y.; Chen, C.-W.; Dong, C.-D. Construction of carbon nanotubes bridged MoS2/ZnO Z-scheme nanohybrid towards enhanced visible light driven photocatalytic water disinfection and antibacterial activity. Carbon 2022, 196, 877–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

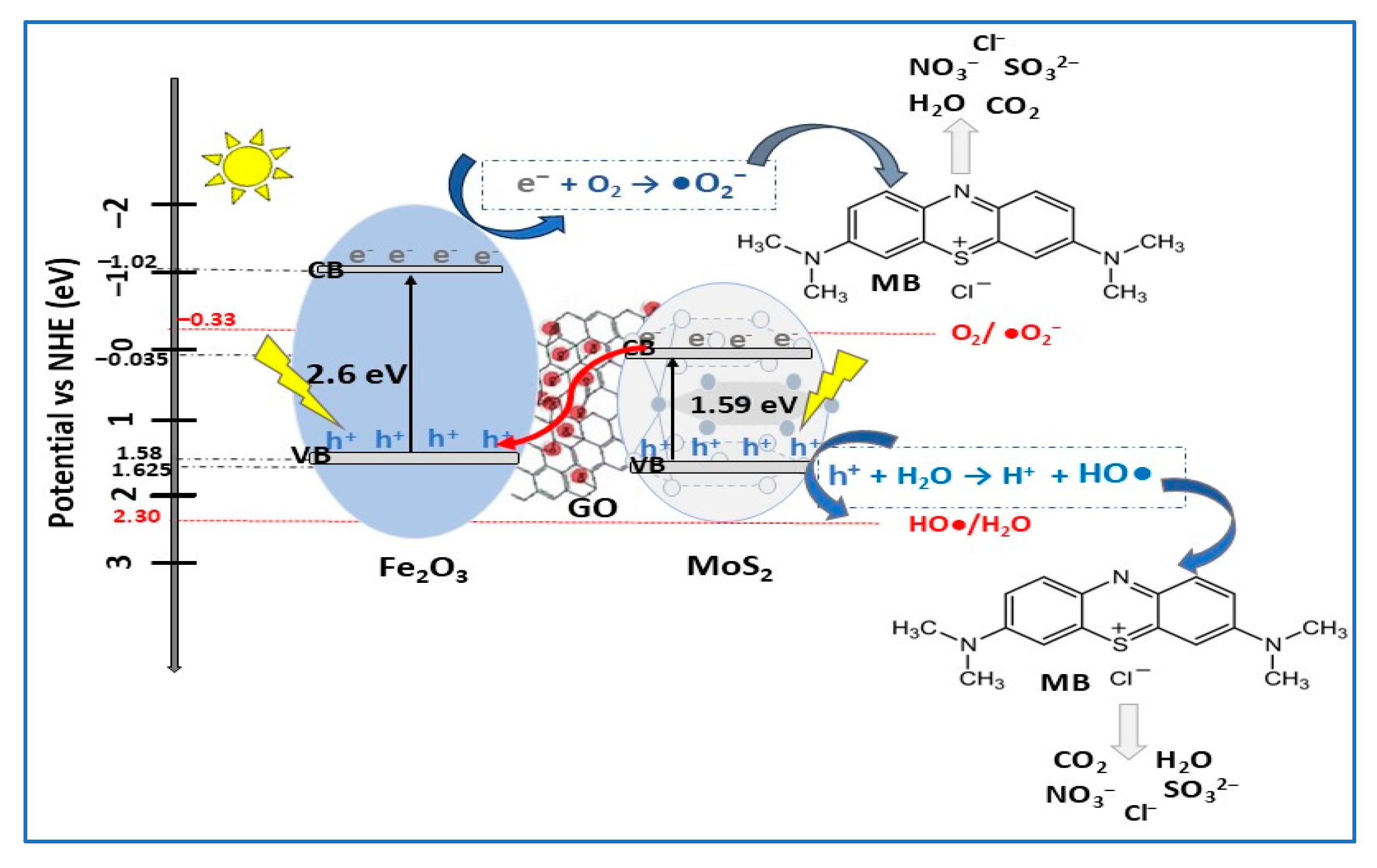

- Samarasinghe, L.V.; Muthukumaran, S.; Baskaran, K. Magnetically recoverable MoS2/Fe2O3/graphene oxide ternary Z-scheme heterostructure photocatalyst for wastewater contaminant removal: Mechanism and performance. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agboola, P.O.; Shakir, I. Facile fabrication of SnO2/MoS2/rGO ternary composite for solar light-mediated photocatalysis for water remediation. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 18, 4303–4313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

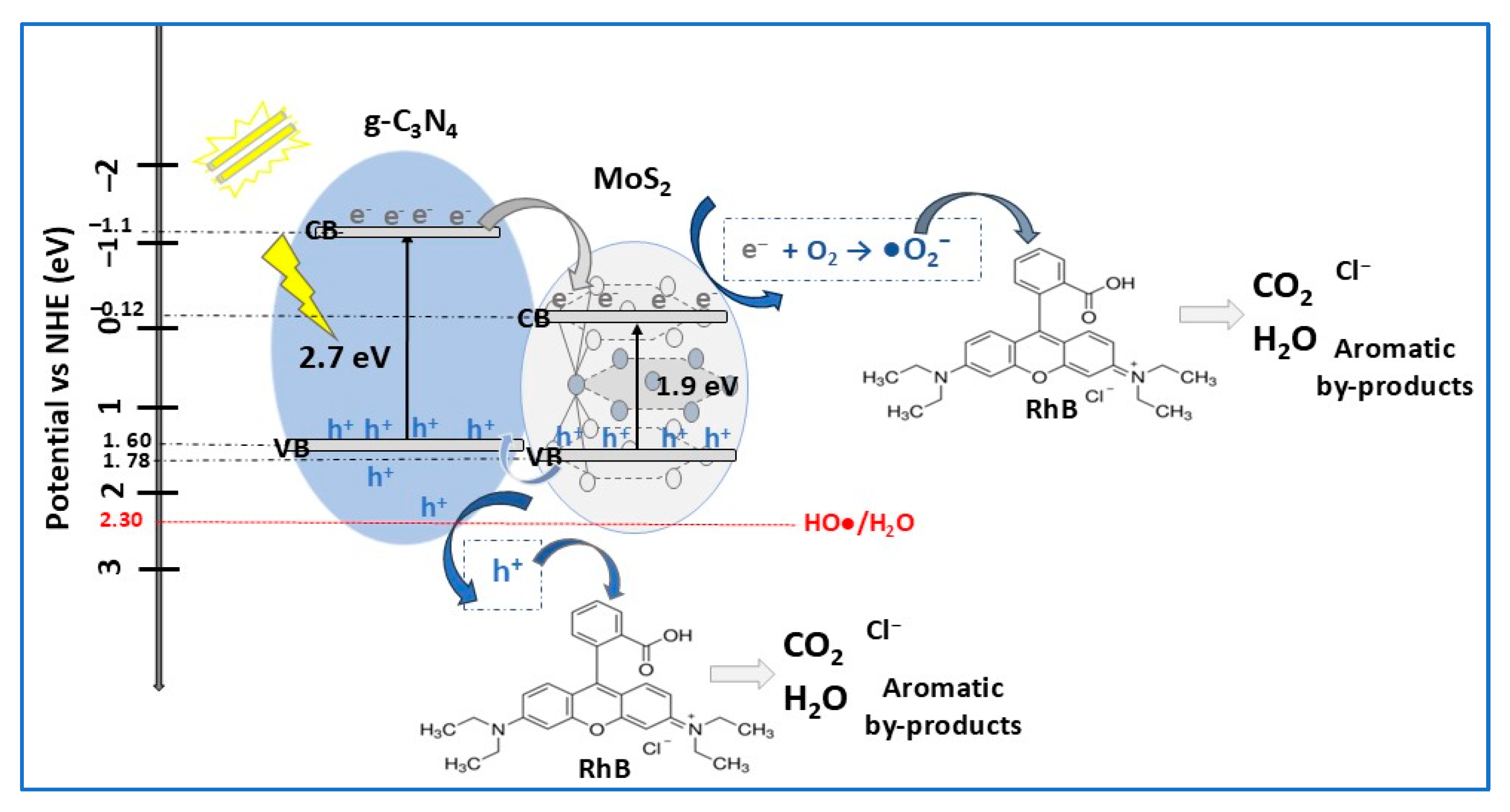

- Rapti, I.; Bairamis, F.; Konstantinou, I. g-C3N4/MoS2 Heterojunction for Photocatalytic Removal of Phenol and Cr(VI). Photochem 2021, 1, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Wu, H.; Bai, K.; Chen, X.; Li, E.; Shen, Y.; Wang, M. Fabrication of a g-C3N4/MoS2 photocatalyst for enhanced RhB degradation. Phys. E 2022, 144, 115361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Li, J.; Cao, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y. Rational design of novel Ag-MoS2@COF ternary heterojunctions and their photocatalytic applications. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1328, 141395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anushya, G.; Benjamin, M.; Sarika, R.; Pravin, J.C.; Sridevi, R.; Nirmal, D. A review on applications of molybdenum disulfide material: Recent developments. Micro Nanostructures 2024, 186, 207742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmaruzzaman, M.d.; Gadore, V. MoS2 based nanocomposites: An excellent material for energy and environmental applications. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Meng, G.; Mishra, P.; Tripathi, N.; Bannov, A.G. A systematic review on 2D MoS2 for nitrogen dioxide (NO2) sensing at room temperature. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 34, 105045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Wei, G.; Yao, Z.; De, Z.; Xuemin, Q.; Guo, J. Molybdenum Sulfide (MoS2)/Ordered Mesoporous Carbon (OMC) Tubular Mesochannel Photocatalyst for Enhanced Photocatalytic Oxidation for Removal of Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs). Front. Chem. 2022, 9, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Gong, W.; Yan, Z.; Gao, A.; Li, Y.; Luo, Y.; Zhao, B.; Lin, J. A honeycomb-rod-like hierarchical MoO3@MoS2@ZnIn2S4 p-n heterojunction composite photocatalyst for efficient solar hydrogen production. Fuel 2025, 399, 135674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.-X.; Lou, Q.; Shan, C.-X.; Du, W.-J. A novel MoS2-modified hybrid nanodiamond/g-C3N4 photocatalyst for photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Chem. Phys. 2024, 577, 112135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfa, I.; Hafeez, H.Y.; Mohammed, J.; Abdu, S.; Suleiman, A.B.; Ndikilar, C.E. A recent progress and advancement on MoS2-based photocatalysts for efficient solar fuel (hydrogen) generation via photocatalytic water splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 71, 1006–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdu, S.; Hafeez, H.Y.; Mohammed, J.; Safana, A.A.; Ndikilar, C.E.; Suleiman, A.B.; Alfa, I. Advances and challenges in MoS2-based photocatalyst for hydrogen production via photocatalytic water splitting. Mater. Today Sustain. 2025, 31, 101142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adabala, S.; Dutta, D.P. A review on recent advances in metal chalcogenide-based photocatalysts for CO2 reduction. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, P.Y.; Guo, R.; Pan, W.; Huang, C.; Tang, J.; Liu, X.; Qin, H.; Xu, Q. The MoS2/TiO2 heterojunction composites with enhanced activity for CO2 photocatalytic reduction under visible light irradiation. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2019, 570, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Punia, R.; Pant, K.K.; Biswas, P. Effect of work-function and morphology of heterostructure components on CO2 reduction photo-catalytic activity of MoS2-Cu2O heterostructure. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 433, 132709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, P.; Mohammad, A.; Ripathi, B.; Yoon, T. Recent advancements in molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) and its functional nanostructures for photocatalytic and non-photocatalytic organic transformations. FlatChem 2022, 34, 100395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarshenas, M.; Sangiovanni, D.G.; Sarakinos, K. Diffusion and magnetization of metal adatoms on single-layer molybdenum disulfide at elevated temperatures. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2024, 42, 023409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Jin, Y.; Lei, B.; Zhao, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, Y. Studies on Electronic Structure and Optical Properties of MoS2/X (X = WSe2, MoSe2, AlN, and ZnO) Heterojunction by First Principles. Catalysts 2024, 14, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.; Liu, B.; Zhen, D. Synthesis of Z-scheme Mn-CdS/MoS2/TiO2 ternary photocatalysts for high-efficiency sunlight-driven photocatalysis. Adv. Compos. Lett. 2019, 28, 2633366X1989502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Xie, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Shi, Y.; Fan, J.; Tang, Z. In-situ construction of step-scheme MoS2/Bi4O5Br2 heterojunction with improved photocatalytic activity of Rhodamine B degradation and disinfection. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 623, 500–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, H.; Haneef, Z.; Ahmad, A.; Butler, I.S.; Dara, R.N.; Rehman, Z. MoS2 and CdS photocatalysts for water decontamination: A review. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2023, 153, 110775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Sharma, A. Importance and challenges of hydrothermal technique for synthesis of transition metal oxides and composites as supercapacitor electrode materials. J. Energy Storage 2021, 44, 103295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbi, Z.D. Electronic and optical properties of molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) mono layer using density functional theory (DFT) calculations. AIP Adv. 2025, 15, 025313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.M.; Guo, S.D.; Duan, Y.F.; Xu, W.; Zhang, J. Electronic and optical properties of single-layer MoS2. Front. Phys. 2018, 13, 137307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Meng, X.; Zhang, Z. Recent development on MoS2-based photocatalysis: A review. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C 2018, 35, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, O.K.; Chihaia, V.; Pham-Ho, M.-P.; Son, D.N. Electronic and optical properties of monolayer MoS2 under the influence of polyethyleneimine adsorption and pressure. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 4201–4210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamiyev, Z.; Balayeva, N.O. Metal Sulfide Photocatalysts for Hydrogen Generation: A Review of Recent Advances. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samy, O.; Zeng, S.; Birowosuto, M.D.; El Moutaouakil, A. A Review on MoS2 Properties, Synthesis, Sensing Applications and Challenges. Crystals 2021, 11, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, J.Y. Absorption coefficient estimation of thin MoS2 film using attenuation of silicon substrate Raman signal. Results Phys. 2019, 13, 102202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, T.-M.; Chan, S.-W.; Lin, Y.-J.; Yang, P.-K.; Liu, C.-C.; Lin, Y.-J.; Wu, J.-M.; Lee, J.-T.; Lin, Z.-H. A highly efficient Au-MoS2 nanocatalyst for tunable piezocatalytic and photocatalytic water disinfection. Nano Energy 2019, 57, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, C.-Y.; Wu, J.M. Localized surface plasmon resonance coupling with piezophototronic effect for enhancing hydrogen evolution reaction with Au@MoS2 nanoflowers. Nano Energy 2021, 87, 106131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, P.-H.; Lin, K.-H.; Lee, Y.-S.; Liao, P.-C.; Juan, J.C.; Chen, C.-Y. H2O2-free catalytic dye degradation at dye/night circumstances using CuS@Au heterostructures decorating on MoS2 nanoflowers. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1002, 175355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayyab, M.; Xie, Y.; Tan, X.; Usman, M.; Tang, M.-C.; Chen, S.S. A ternary dumbbell MoS2 tipped Zn0.1Cd0.9S nanorods visible light driven photocatalyst for simultaneous hydrogen production with organics degradation in wastewater. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 505, 159064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, B.; Fan, J.; Yu, J. S-Scheme Heterojunction Photocatalyst. Chem 2020, 6, 1543–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koladia, G.C.; Bhole, A.; Bora, N.V.; Bora, L.V. Biowaste derived UV–Visible-NIR active Z-scheme CaO/MoS2 photocatalyst as a low-cost, waste-to-resource strategy for rapid wastewater treatment. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 2024, 446, 115172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoseini, A.; Yarmand, B. Photoelectrocatalytic and photocorrosion behavior of MoS2- and rGO-containing TiO2 bilayer photocatalyst immobilized by plasma electrolytic oxidation. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 984, 173976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasikala, V.; Lavanya, V.; Karthik, P.; Sarala, S.; Prakash, N.; Mukkannan, A. Enhanced photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants via TiO2-integrated 2D MoS2 nanostructures. Surf. Interfaces 2025, 72, 107089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitara, E.; Ehsan, M.F.; Nasir, H.; Iram, S.; Bukhari, S.A.B. Synthesis, Characterization and Photocatalytic Activity of MoS2/ZnSe Heterostructures for the Degradation of Levofloxacin. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borthakur, P.; Boruah, P.K.; Dasab, P.; Das, M.R. CuS nanoparticles decorated MoS2 sheets as an efficient nanozyme for selective detection and photocatalytic degradation of hydroquinone in water. New J. Chem. 2021, 45, 8714–8727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Du, X.; Xia, C.; Wang, X.; Yang, T.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zhu, D.; Yin, F. Fabrication and photocatalytic properties of nano CuS/MoS2 composite catalyst by dealloying amorphous Ti–Cu–Mo alloy. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 467–468, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Pal, T.; Ghosh, S. MoS2–CdS Composite Photocatalyst for Dye Degradation: Enhanced Apparent Quantum Yield and Reduced Energy Consumption. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, e202403559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Wang, S.; Jiang, J.; Shao, L.; Li, D.; Yuan, J.; Xu, F. Magnetic Fe3S4/MoS2 with visible-light response as an efficient photo-Fenton-like catalyst: Validation in degrading tetracycline hydrochloride under mild pH conditions. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 921, 166023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

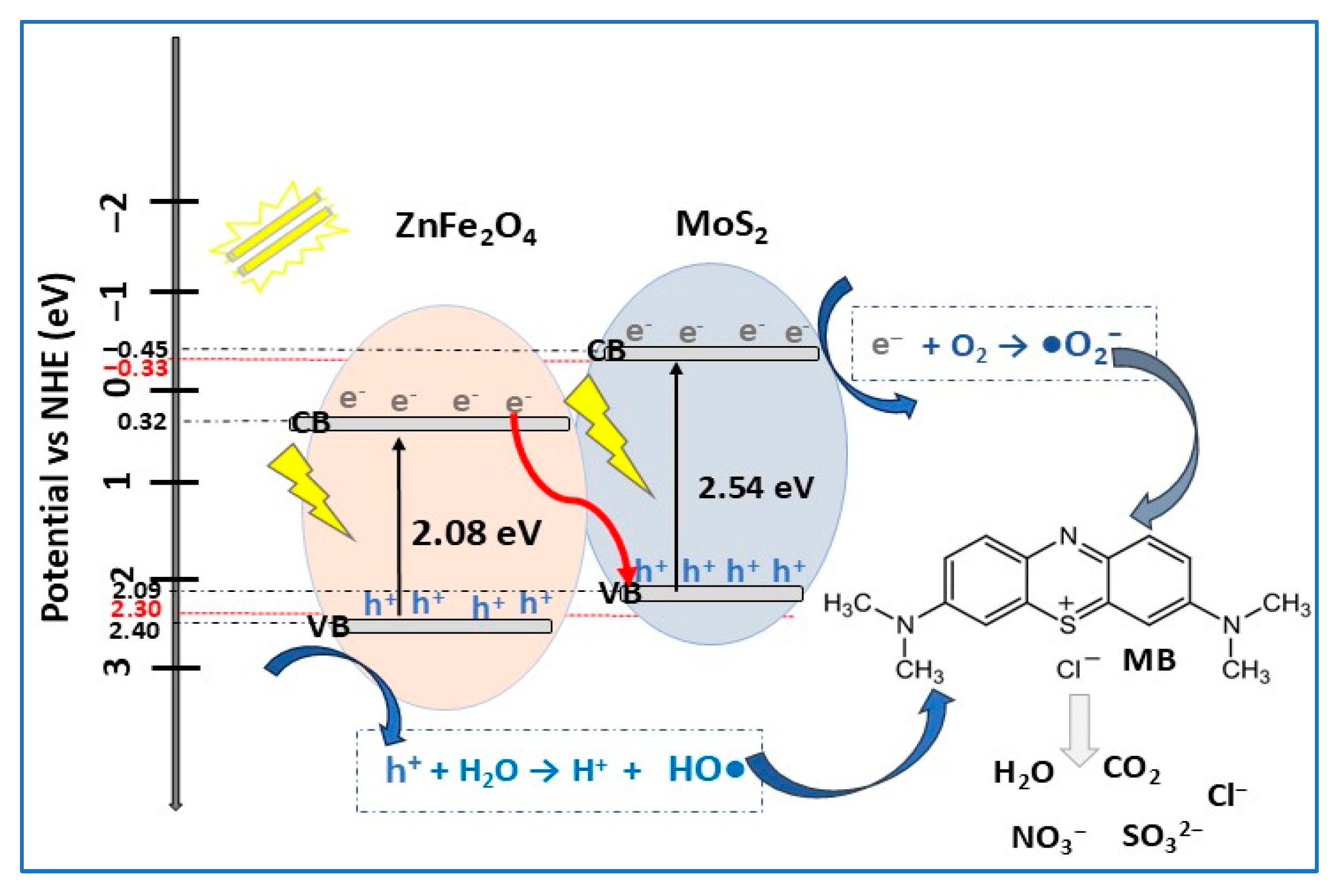

- Laxmiputra; Nityashree, D.B.; Udayabhanu; Anush, S.M.; Pramoda, K.; Prashantha, K.; Beena ullala mata, B.N.; Girish, Y.R.; Nagarajaiah, H. Construction of Z-Scheme MoS2/ZnFe2O4 heterojunction photocatalyst with enhanced photocatalytic activity under visible light. Mater. Res. Bull. 2024, 169, 112489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

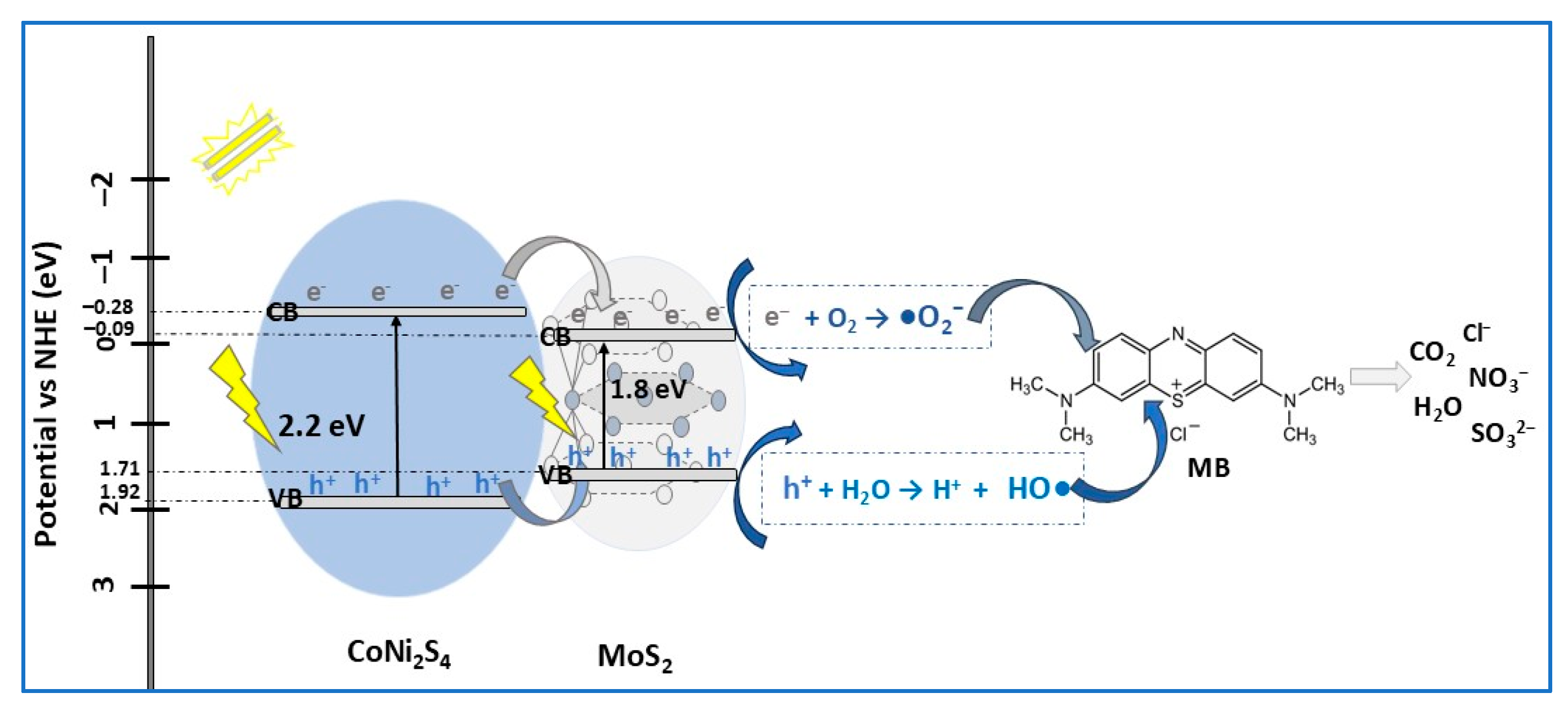

- Anusha, B.R.; Udayabhanu; Appu, S.; Alharethy, F.; Reddy, G.S.; Abhijna; Sangamesha, M.A.; Nagaraju, G.; Kumar, S.G.; Prashantha, K. Enhanced charge carrier separation in stable Type-1 CoNi2S4/MoS2 nanocomposite photocatalyst for sustainable water treatment. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2025, 198, 112444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Xia, J. Fabrication of MoS2/FeOCl composites as heterogeneous photo-fenton catalysts for the efficient degradation of water pollutants under visible light irradiation. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 648, 129357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Xu, J.; Xu, W.; Zheng, Y.; Wu, G.; Jeong, T. Photocatalytic Activity of MoS2 Nanoflower-Modified CaTiO3 Composites for Degradation of RhB Under Visible Light. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, M.T.L.; Lee, K.M.; Yang, T.C.K.; Lai, C.W.; Chen, C.-Y.; Johan, M.R.; Juan, J.C. Highly effective interlayer expanded MoS2 coupled with Bi2WO6 as p-n heterojunction photocatalyst for photodegradation of organic dye under LED white light. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 953, 169834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atla, R.; Oh, T.H. Novel fabrication of the recyclable MoS2/Bi2WO6 heterostructure and its effective photocatalytic degradation of tetracycline under visible light irradiation. Chemosphere 2022, 303, 134922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Shi, L.; Wang, Z.; Ren, T.; Geng, Z.; Qi, W. 2D layered MoS2 loaded on Bi12O17Cl2 nanosheets: An effective visible-light photocatalyst. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 7438–7445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Li, Y.; Fu, Q.; Chen, M. Fabrication of a novel biochar decorated nano-flower-like MoS2 nanomaterial for the enhanced photodegradation activity of ciprofloxacin: Performance and mechanism. Mater. Res. Bull. 2022, 147, 111650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wei, L.; Luo, S.; Yang, X. High-efficiency PPy@MoS2 Core-Shell Heterostructure Photocatalysts for enhanced pollutant degradation activity. Results Chem. 2025, 14, 102091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, R.; Li, Z.; Tian, B.; Ma, H.; Zheng, Z.; Zhou, B.; Ji, M.T.; Shi, J.; et al. Supramolecularly engineered S-scheme SubPc-Br/MoS2 photocatalyst nanosheets for enhanced photocatalytic degradation of antibiotics. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 477, 147193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trang Phan, T.T.; Truong, T.T.; Huu, H.T.; Nguyen, L.T.; Nguyen, V.T.; Nguyen, H.L.; Vo, V. Visible Light-Driven Mn-MoS2/rGO Composite Photocatalysts for the Photocatalytic Degradation of Rhodamine B. J. Chem. 2020, 2020, 6285484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutlag, A.S.; Rafiee, E.; Khodayari, M.; Eavani, S. Glass coated-nanostructure semiconductor TiO2/RGO/MoS2 for dye removal and disinfection of wastewater: Design and construction of a novel fixed-bed photocatalytic reactor. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2022, 148, 106821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Luo, L.; Shi, Z.; Shen, X.; Peng, C.; Liu, J.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, L. Synthesis of MoS2/CdS Heterostructures on Carbon-Fiber Cloth as Filter-Membrane-Shaped Photocatalyst for Purifying the Flowing Wastewater under Visible-Light Illumination. ChemCatChem 2019, 11, 2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomayrah, N.; Ikram, M.; Alomairy, S.; Al-Buriahi, M.S.; Khan, M.N.; Warsi, M.F.; Irshad, A. Fabrication of CuO/MoS2@gCN nanocomposite for effective degradation of methyl orange and phenol photocatalytically. Results Phys. 2024, 64, 107902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

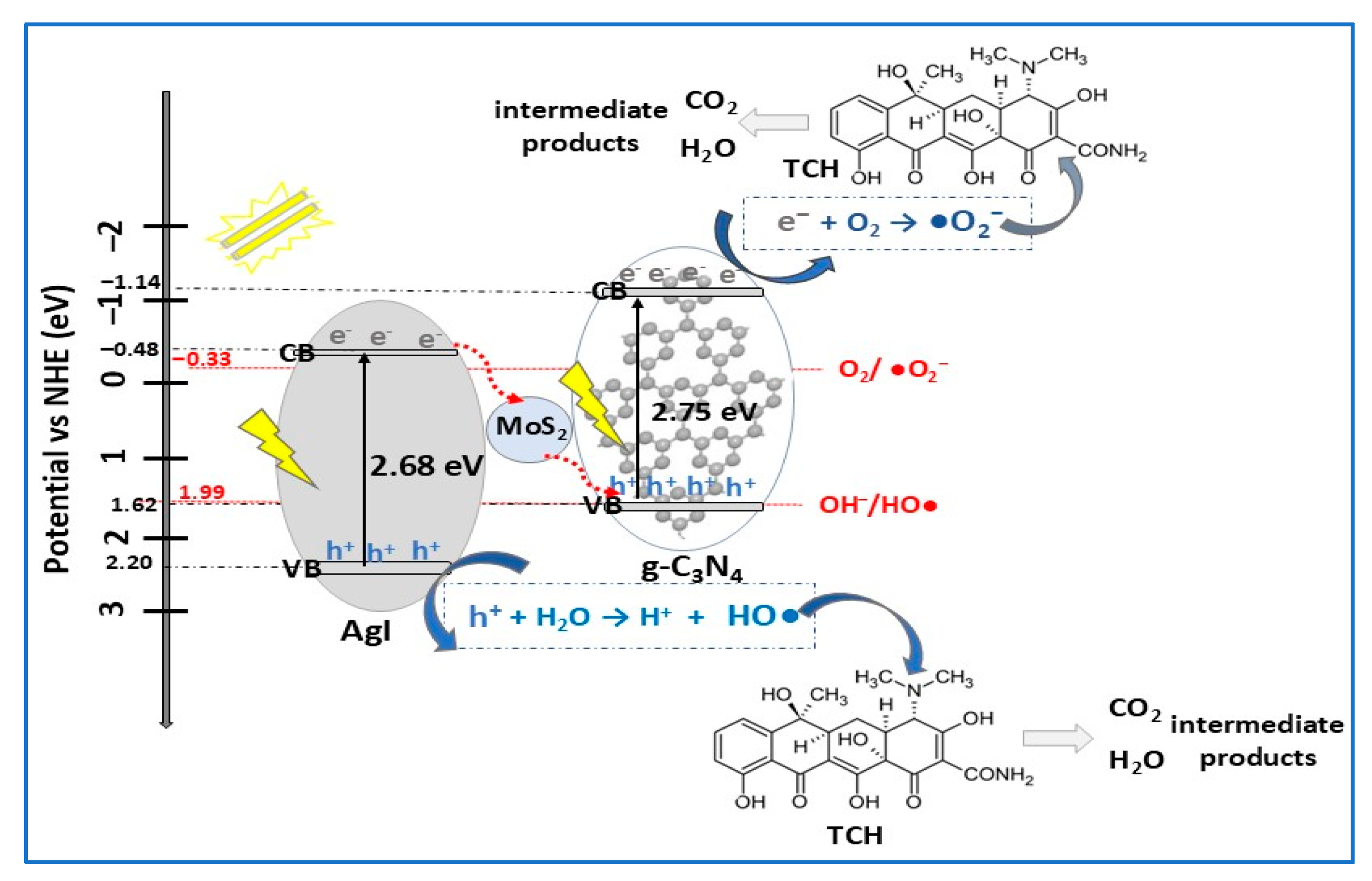

- Liu, B.; Wang, G.; Li, J.; Liu, B.; Li, R.; Huang, H.; Shi, H.; Zhang, J. MoS2 quantum dots-bridged g-C3N4/AgI Z-scheme photocatalyst for efficient antibiotic degradation and bacteria inactivation under visible light. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 63, 105419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

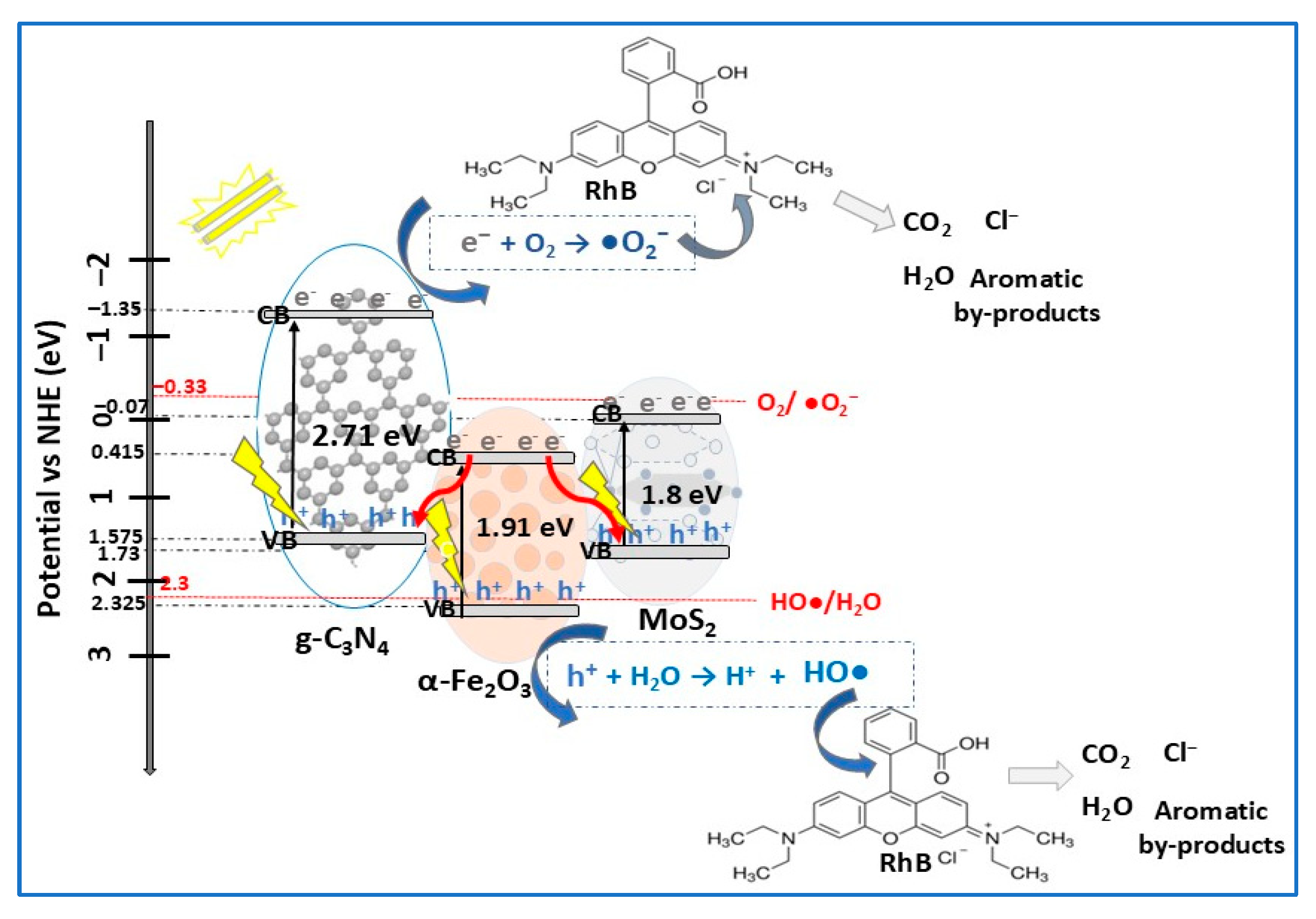

- Vignesh, S.; Suganthi, S.; Chandrasekaran, S.; Arumugam, E.; Oh, T.H. Developing of α-Fe2O3/MoS2 embedded g-C3N4 nanocomposite photocatalyst for improved environmental dye degradation and electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction performance. Opt. Mater. 2024, 154, 115727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Shen, S.; Cheng, W.; Han, G.; Wu, Q.; Jiang, J. Construction of mechanically robust and recyclable photocatalytic hydrogel based on nanocellulose-supported CdS/MoS2/Montmorillonite hybrid for antibiotic degradation. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 636, 128035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

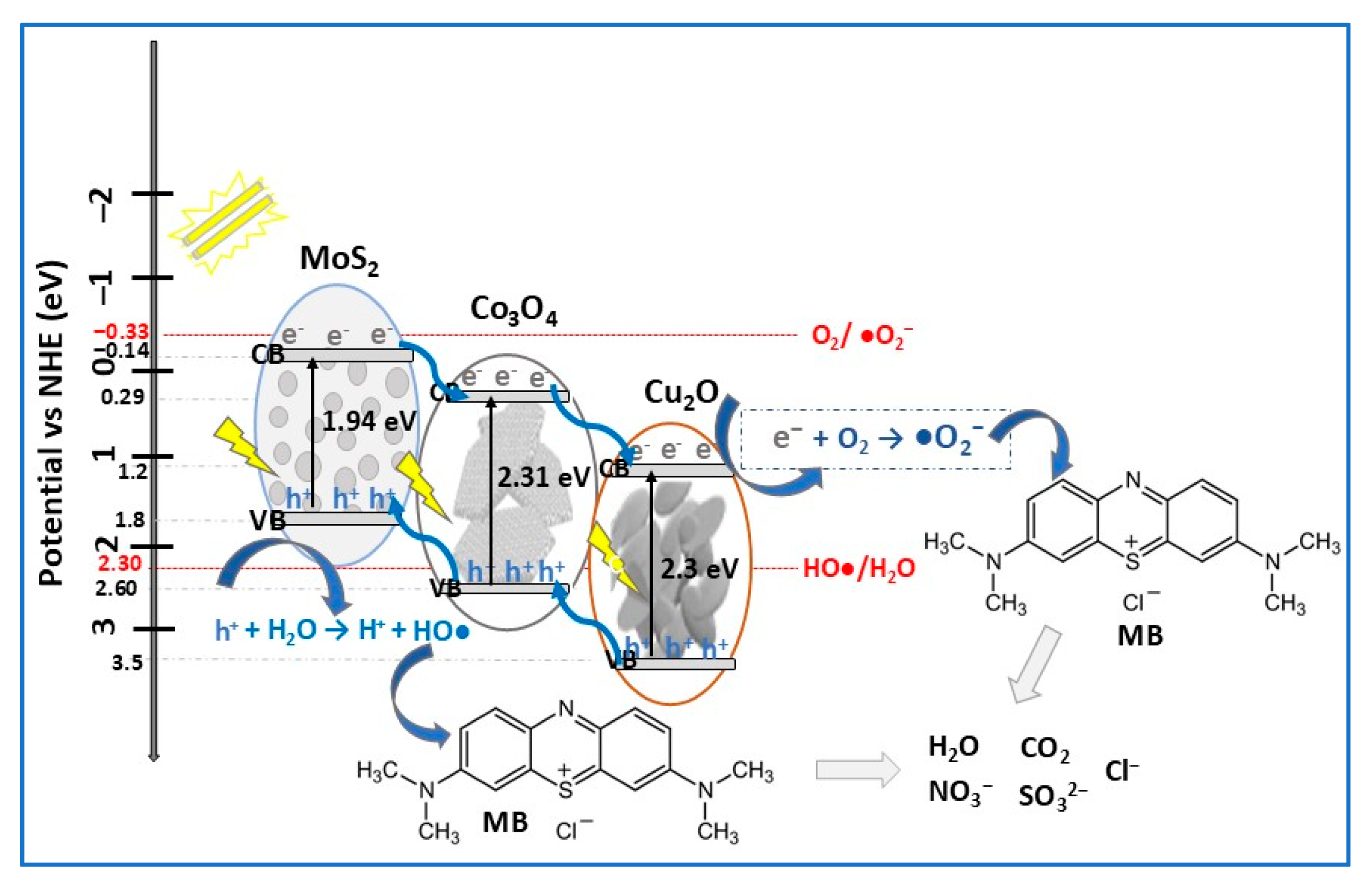

- Karthigaimuthu, D.; Bojarajan, A.K.; Thangavel, E.; Maram, P.S.; Venkidusamy, S.; Sangaraju, S.; Mourad, A.-H.I. Synergistic effects in MoS2/Co3O4/Cu2O nanocomposites for superior solar cell and photodegradation efficiency. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 177672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Lu, M.; Yang, H.; Wu, X. Novel MoS2-based heterojunction as an efficient and magnetically retrievable piezo-photocatalyst for diclofenac sodium degradation. Mater. Today Sustain. 2024, 28, 101000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yang, Y.-L.; Chen, H.-J.; Liu, J.; Shi, X.-L.; Suo, G.; Hou, X.; Ye, X.; Zhang, L.; Lu, S.; et al. Flexible, recoverable, and efficient photocatalysts: MoS2/TiO2 heterojunctions grown on amorphous carbon-coated carbon textiles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 651, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, N.; Du, Y.; Ji, P.; Liu, S.; He, B.; Qu, J.; Wang, J.; Sun, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, H. Enhanced photocatalytic activity of novel TiO2/Ag/MoS2/Ag nanocomposites for water-treatment. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 4889–4896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armaković, S.J.; Savanović, M.M.; Armaković, S. Titanium Dioxide as the Most Used Photocatalyst for Water Purification: An Overview. Catalysts 2023, 13, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balayeva, N.O.; Mamiyev, Z.; Dillert, R.; Zheng, N.; Bahneman, D.W. Rh/TiO2-Photocatalyzed Acceptorless Dehydrogenation of N-Heterocycles upon Visible-Light Illumination. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 5542–5553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, A.; Yi, H. Progress and Challenges of SnO2 Electron Transport Layer for Perovskite Solar Cells: A Critical Review. Sol. RRL 2022, 6, 2100983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, P.; Lai, C.; Qin, H.; He, Y.; Li, Y.; Huo, X.; Tian, Q.; Wang, C. Fenton chemistry rising star: Iron oxychloride. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 518, 216051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Yadav, A.; Zhou, H.; Roy, K.; Thanasekaran, P.; Lee, C. Advances and Applications of Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) in Emerging Technologies: A Comprehensive Review. Glob. Chall. 2024, 8, 2300244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.; Guo, C.; Wang, T.; Cheng, X.; Huo, L.; Zhang, X.; Huang, C.; Major, Z.; Xu, Y. A review of g-C3N4-based photocatalytic materials for photocatalytic CO2 reduction. Carbon Neutraliz 2024, 3, 557–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabesh, F.; Mallakpour, S.; Hussain, C.M. Recent advances in magnetic semiconductor ZnFe2O4 nanoceramics: History, properties, synthesis, characterization, and applications. J. Solid State Chem. 2023, 322, 123940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawky, A.; Mohamed, R.M. S-scheme heterojunctions: Emerging designed photocatalysts toward green energy and environmental remediation redox reactions. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, S.; Kumar, A.; Wang, T.-t.; Sharma, G.; Dhiman, P.; García-Penas, A. A review of carbon material-based Z-scheme and S-scheme heterojunctions for photocatalytic clean energy generation. New Carbon Mater. 2024, 39, 458–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subagyo, R.; Yudhowijoyo, A.; Sholeha, N.A.; Hutagalung, S.S.; Prasetyoko, D.; Birowosuto, M.D.; Arramel, A.; Jiang, J.; Kusumawati, Y. Recent advances of modification effect in Co3O4-based catalyst towards highly efficient photocatalysis. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 650, 1550–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Zuo, C.; Liu, M.; Tai, X. A Review on Cu2O-Based Composites in Photocatalysis: Synthesis, Modification, and Applications. Molecules 2023, 28, 5576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaral, L.O.; Daniel-da-Silva, A.L. MoS2 and MoS2 Nanocomposites for Adsorption and Photodegradation of Water Pollutants: A Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 6782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saber, M.A.; Khabiri, G.; Ahmed, A.; Maarouf, A.; Ulbricht, M.; Khali, A.S.G. A comparative study on the photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes using hybridized 1T/2H, 1T/3R and 2H MoS2 nano-sheets. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 26364–26370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Hu, Y.; Li, Q.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Shi, Y.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, J. Carbon-doped defect MoS2 co-catalytic Fe3+/peroxymonosulfate process for efficient sulfadiazine degradation: Accelerating Fe3+/Fe2+ cycle and 1O2 dominated oxidation. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 858, 159587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Huang, X.; Liao, W.; Zhao, Y. MoS2-based membranes in water treatment and purification. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 422, 130082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, H.H.; Umar, M.; Nawaz, I.; Ihsan, R.M.; Razzak, H.; Gong, H.; Liu, X. Photo responsive single layer MoS2 nanochannel membranes for photocatalytic degradation of contaminants in water. Npj Clean Water 2024, 7, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Cho, K.-H.; Presser, V.; Su, X. Recent advances in wastewater treatment using semiconductor photocatalysts. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2022, 36, 100644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Photocatalyst Morphology | Eg eV | SBET m2/g | Dye | λmax nm | η* % | t min | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MoS2 3D flower-like hemispheres (d ≈ 2.5 μm) | 2.05 | - | RhB MB | 554 665 | 81.5 91.6 | 120 | [1] |

| MoS2 nanoflowers (d ≈ 100 nm) | 2.2 | - | RhB | 554 | 39.9 | 120 | [34] |

| MoS2 layered nanostructures | - | 50 | MB CV | 665 590 | 83 (UV) 73 (sun) 71 (UV) 57 (sun) | 90 | [2] |

| MoS2 NPs (d ≈ 70 nm) MoS2 (M-UREA) NRs (d ≈ 25 nm) | 2 1.96 | 45 29 | industrial (leather) wastewater | - | 45 59 | 180 | [5] |

| MoS2 irregular microspheres (d ≈ 500 nm) | - | - | TBC | 221 | 95 | 720 | [7] |

| MoS2 nanoflakes (d ≈ 13 nm) MoS2 biosynthesized nanoflakes (d ≈ 4–6 nm) | 2.37 2.03 | 79 121–134 | OTC | 376 | 96 98–99 | 120 | [35] |

| MoS2 nanopetals Ag-MoS2 nanopetals (reduced d and thickness) | 2.35 1.55 | - | MB | 665 | 40 100 | 20 0.67 | [8] |

| MoS2 spherical flowers (d ≈ 400 nm) Sn-MoS2 spherical flowers (d ≈ 800 nm) | 2.4 2.3 | 53 127 | RhB | 554 | 100 100 | 40 20 | [3] |

| Photocatalyst | Heterojun-ction Type | Synthesis Method | Pollutant Conc. (mg/L) | Catalyst Dosage (g/L) | Light Source | η* % | t Min | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MoS2/SnO2 | II | hydrothermal | MB (8) | 2 | VIS (150 W Xenon lamp) | 99.5 | 5 | [26] |

| CaO/MoS2 | Z-scheme | ball milling + calcination (900 °C, 2 h) | MB (57.14) | 1 | sunlight | 70 | 10 | [72] |

| MoS2/ZnO | I | hydrothermal | SMX (20) MX, MB TMP, MG CV | 0.8 | VIS (1500 W Xenon lamp) | 100 100 100 100 | 30 30 90 120 | [24] |

| MoS2/ZnO QDs MoS2 | I | hydrothermal | TC (20) | 0.01 | VIS (300 W halogen lamp) | 96.5 38.4 | 120 | [23] |

| MoS2/TiO2 | II | two-step hydrothermal | MB (5) | 6.25 cm2/ 10 mL MB | VIS (Xenon lamp) | 86 | 180 | [1] |

| MoS2/TiO2 | II | hydrothermal | MB (10) | 0.5 | VIS (100 W Xe lamp) | 74.4 | 120 | [73] |

| 2D MoS2/TiO2 MoS2 | I | hydrothermal | RhB (10) | 0.3 | VIS (125 W Hg lamp) | 75 60 | 25 | [22] |

| MoS2/TiO2 | Z-scheme | hydrothermal | CV (122.4) | 0.2 | UV (400 W Xe lamp) | 94.4 | 60 | [74] |

| MoS2/ZnSe MoS2 | II | ultrasonication | Levofloxacin (11) | 0.3 | VIS (500 W Xe lamp) | 73.2 29 | 120 | [75] |

| CuS/MoS2 | S-scheme p–n | hydrothermal | TC (20) | 0.7 | VIS, VIS–NIR (LCS-100 solar simulator) | 95 | 30 | [13] |

| CuS/MoS2 | S-scheme | hydrothermal | HQ (11) | 0.5 | sunlight | 83 | 240 | [76] |

| CuS/MoS2 | II | dealloying amorphous Ti-Cu−Mo ribbons in acid solution | MB (10) | 0.5 | VIS (500 W Xe lamp) | 99.9 | 80 | [77] |

| MoS2/CdS | I | solvothermal | NRFX (20) | 0.5 | VIS (Tungsten halogen lamp) | 87.5 | 25 | [30] |

| MoS2/CdS | I | solvothermal | RhB (10) | 0.1 | VIS (300 W Xe lamp) | 83 | 120 | [29] |

| MoS2/CdS | I | solvothermal | RhB (10) | 0.5 | VIS (300 W Xe lamp) | 91.9 | 60 | [78] |

| MoS2/In2S3 | II | hydrothermal | MB (4.8) OTC (0.3) | 0.0025 | Sunlight (800 W/m2) | 97.67 76.3 | 8 40 | [32] |

| MoS2/Fe3S4 | - | hydrothermal | TCH (50) | 2.5 | VIS (300 W Xe lamp) | 79.9 | 60 | [79] |

| MoS2/WS2 MoS2 | II | chemical vapor deposition | MB (5) | - | Solar simulator | 66.7 43.5 | 180 | [31] |

| MoS2/Zn0.1Cd0.9S | I | solvothermal | OFX (20) | 0.25 | VIS (300 W Xe lamp) | 90 | 120 | [70] |

| MoS2/ZnCdS | I | photodeposition | TC (30) | 0.2 | VIS (1 W LED lamp) | 75 | 240 | [18] |

| MoS2/ZnFe2O4 | Z-scheme | hydrothermal | MB (10) | 0.1 | VIS (160 W tungsten-mercury lamp) | 92.3 | 150 | [80] |

| CoNi2S4/MoS2 | I | hydrothermal | MB (10) | 0.2 | VIS (500 W Xe lamp) | 100 | 90 | [81] |

| MoS2/FeOCl | II | ultrasonic | TC (50) RhB (10) + 20 μL H2O2 | 0.1 | VIS (300 W Xe arc lamp) | 90 85.4 | 40 30 | [82] |

| MoS2/NiAlFe LTH | S-scheme p–n | hydrothermal | IC (20) | 1 | VIS (105 W Xe arc lamp) | 100 | 100 | [9] |

| MoS2/CaTiO3 (CTO) | I | hydrothermal, template-free | RhB (1) | 0.033 | VIS (15 W LED lamp) | 96.88 | 180 | [83] |

| MoS2 /Bi2WO6 | S-scheme p–n | solvothermal | MB (20) | 0.2 | VIS (1 W LED white light) | 97 | 40 | [84] |

| MoS2/Bi2WO6 | S-scheme p–n | solvothermal | TC (10) | 0.15 | VIS (100 W solar simulator) | 96.3 | 90 | [85] |

| MoS2/Bi4O5Br2 | S-scheme | In situ mechanical agitation | RhB (10) | 0.03 | VIS (300 W Xe lamp) | 100 | 24 | [57] |

| MoS2/Bi12O17Cl2 | S-scheme | ultrasonic assisted | RhB (10) | 0.6 | VIS (300 W Xe lamp) | 92 | 30 | [86] |

| MoS2/g-C3N4 | II | impregnation + calcination | RhB (10) | 0.4 | VIS (350 W Xe lamp) | 99.4 | 90 | [40] |

| MoS2/g-C3N4 | II | hydrothermal | Phenol (10) | 0.1 | VIS (2.2 kW Xe lamp) | 89 | 20 | [39] |

| MoS2/BC | II | hydrothermal | CIP (7) | 0.2 | VIS (300 W Xe lamp) | 92.01 | 90 | [87] |

| MoS2/PPy | II | oxidative polymerization (Ppy) + hydrothermal | MB (5) | 0.03 | VIS (500 W Xe lamp) | 99.3 | 60 | [88] |

| MoS2/SubPc-Br | S-scheme | commercial MoS2 calcination with SubPc-Br | CTC (30) CIP (30) | 1 | VIS (300 WXe lamp) | 99.22 98.21 | 30 | [89] |

| MoS2/Cu-MOF | II | hydrothermal | RB (50) CR (50) AZR (50) MO (50) NGB (50) | 0.24 | sunlight | 96.3 80.2 73.7 82.1 63.6 | 30 | [4] |

| Ag-MoS2/COF | Z-scheme | hydrothermal | TC (20) | 0.5 | VIS (250 W Xe lamp) | 90.1 | 50 | [41] |

| Mn-MoS2/rGO | Z-scheme | hydrothermal | RhB (20) | 0.25 | VIS (60 W compact lamp) | 90 | 240 | [90] |

| MoS2/SnO2/rGO MoS2 | II | hydrothermal + ultrasonication | MB | 0.2 | sunlight | 90 51 | 75 | [38] |

| TiO2/RGO/MoS2 coatings | - | ultrasonication + dip coating | RhB (4) | 1 | VIS (LEDs 30,000 lumen) | 95 | 90 | [91] |

| MoS2/Fe2O3/GO MoS2 | Z-scheme | ball milling + ultrasonication | MB (10) | 1 | VIS (Xe lamp) sunlight | 97.9 88.2 | 180 | [37] |

| MoS2/CdS/CF | II | hydrothermal (MoS2) + CBD (CdS) | RHB (10) MB (10) TCH (20) | cloth (4 × 4 cm2) | VIS (Xe lamp) | 97.3 97.2 55.6 | 100 70 100 | [92] |

| MoS2/ZnO/CNT | Z-scheme | hydrothermal | TC (20) | 20 | VIS (tungsten light lamp) | 95.6 | 60 | [36] |

| MoS2/CuO/gCN | II | hydrothermal+ coprecipitation+ ultrasonication | MO (10) Phenol (10) | 0.2 | UV (200 W tungsten lamp) | 85.14 63.5 | 35 | [93] |

| AgI/MoS2/g-C3N4 | Z-scheme | solvothermal | TCH (10) | 0.5 | VIS (300 W Xe lamp) | 82.8 | 50 | [94] |

| α-Fe2O3/MoS2/g-C3N4 | Z-scheme | hydrothermal + calcination | RhB (10) MB (10) | 0.5 | VIS (300 W Xe lamp) | 95.5 91.1 | 80 | [95] |

| CdS/MoS2/Mt | I | hydrothermal | TC (20) | 40 | VIS (LED lamp) | 90.03 | 120 | [96] |

| MoS2/Au/CuS | Z-scheme | hydrothermal + in situ chemical reduction | MB (2) | 0.25 | VIS (PanChum multi-lamp photoreactor) | 90.5 day 41 night | 60 | [69] |

| MoS2/Co3O4/Cu2O | S-scheme | sonication + hydrothermal | MB (30) RhB (30) | 1 | VIS (500 W halogen lamp) | 91 92 | 100 90 | [97] |

| MoS2/TiO2/Fe3O4 | - | solvothermal | DCF (5) | 0.2 | VIS (300 W Xe lamp) | 99.6 | 6 | [98] |

| CT-C-MoS2/TiO2 textile | I | hydrothermal | RhB (10) | 2.5 cm × 5 cm/200 mL RhB | VIS (300 W Xe lamp) | 98.8 | 30 | [99] |

| TiO2/Ag/MoS2/Ag | - | hydrothermal + Tollen reaction | RhB (20) | 0.1 | VIS (300 W Xe lamp) | 100 | 60 | [100] |

| ZnS/CdS-Mn/MoS2 /TiO2 | Z-scheme | hydrothermal + successive ionic layer deposition | MO (20) 9-AC (20) | - | VIS (300 W Xe arc lamp) | 98 100 | 100 35 | [56] |

| Hetero-junction Type | Advantages | Limitations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Photocatalytic Mechanism | Photocatalytic System | ||

| I |

|

|

|

| II |

|

|

|

| Z-scheme |

|

|

|

| S-scheme |

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Isac, L.; Cazan, C. Current Research on MoS2-Based Heterojunction Photocatalysts for Persistent Organic Pollutants Degradation. Molecules 2025, 30, 4727. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244727

Isac L, Cazan C. Current Research on MoS2-Based Heterojunction Photocatalysts for Persistent Organic Pollutants Degradation. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4727. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244727

Chicago/Turabian StyleIsac, Luminita, and Cristina Cazan. 2025. "Current Research on MoS2-Based Heterojunction Photocatalysts for Persistent Organic Pollutants Degradation" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4727. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244727

APA StyleIsac, L., & Cazan, C. (2025). Current Research on MoS2-Based Heterojunction Photocatalysts for Persistent Organic Pollutants Degradation. Molecules, 30(24), 4727. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244727