Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Effects of Polyphenolic Extracts from Olive Mill Vegetation Water on Wild Boar Meat Patties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

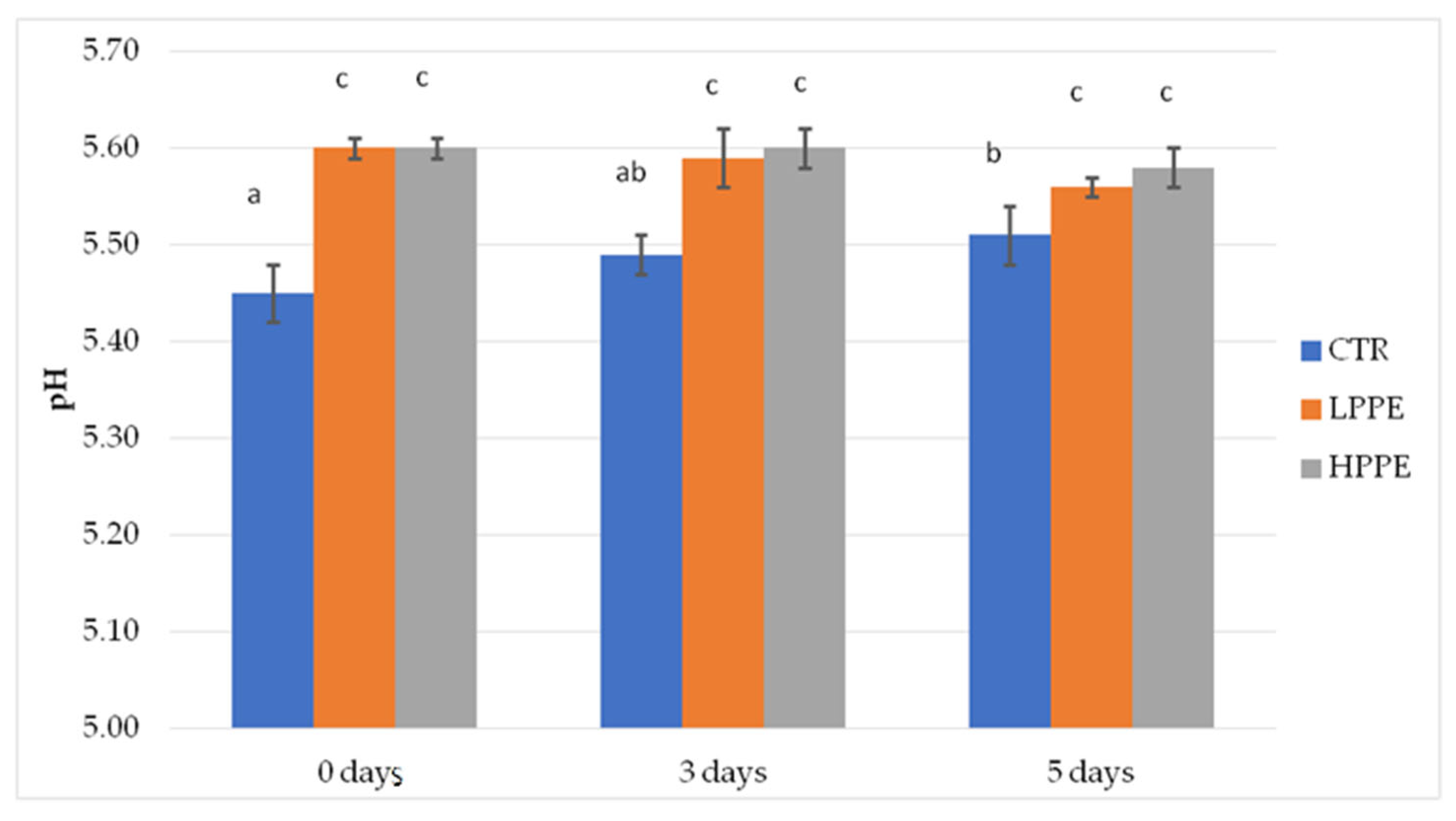

2.1. Trial 1: Effects of Two PPE Doses on Antioxidant and Microbial Contamination of Wild Boar Patties

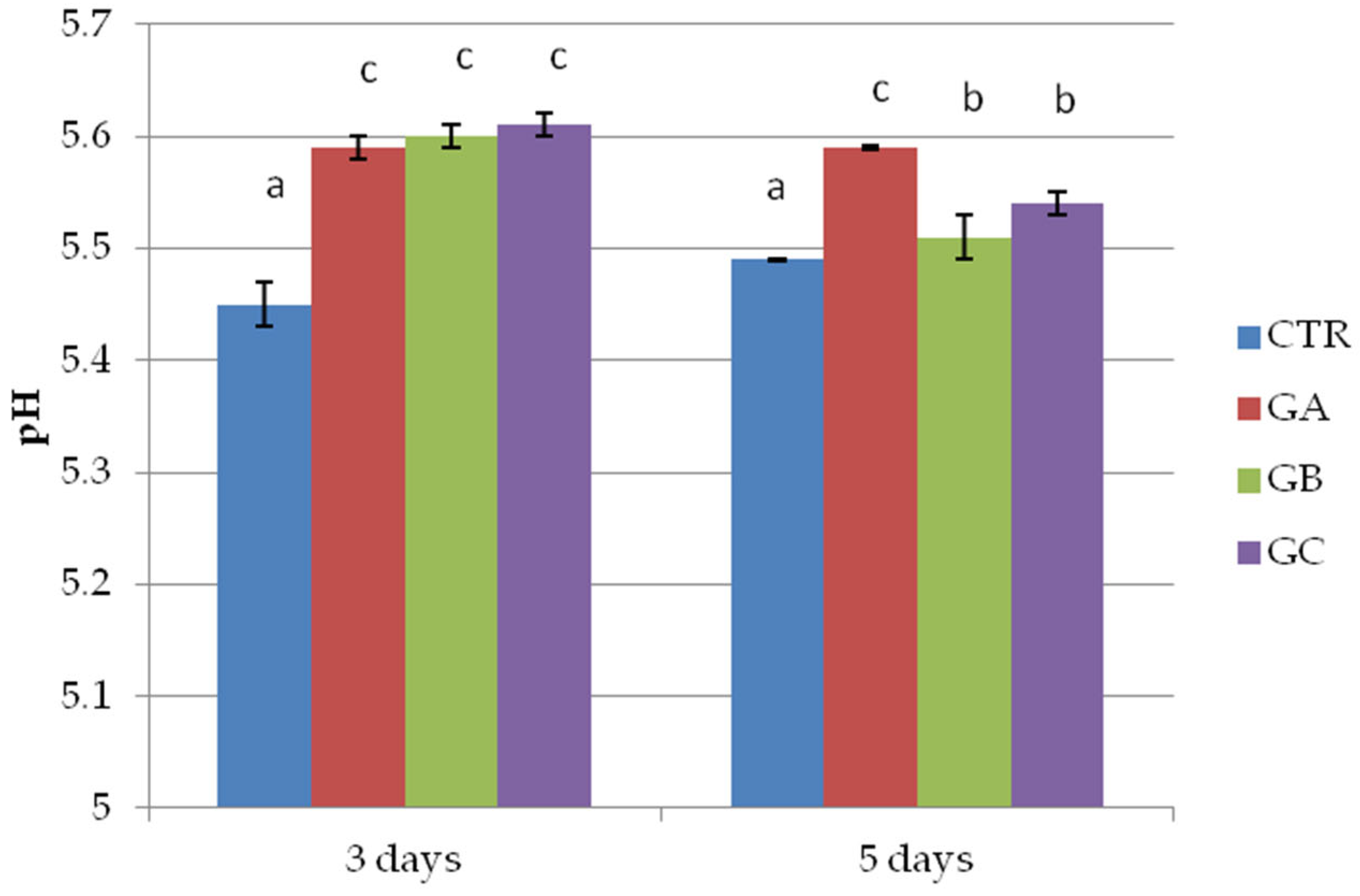

2.2. Trial 2: Patties with and Without PPE 2% and NaCl 1.5%

3. Discussion

3.1. Antioxidant Activity of Phenols

3.2. Antimicrobial Activity of Phenols

3.3. Effects of PPE on Wild Boar Patty Quality Traits

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sample Preparation and Outline of the Experiments

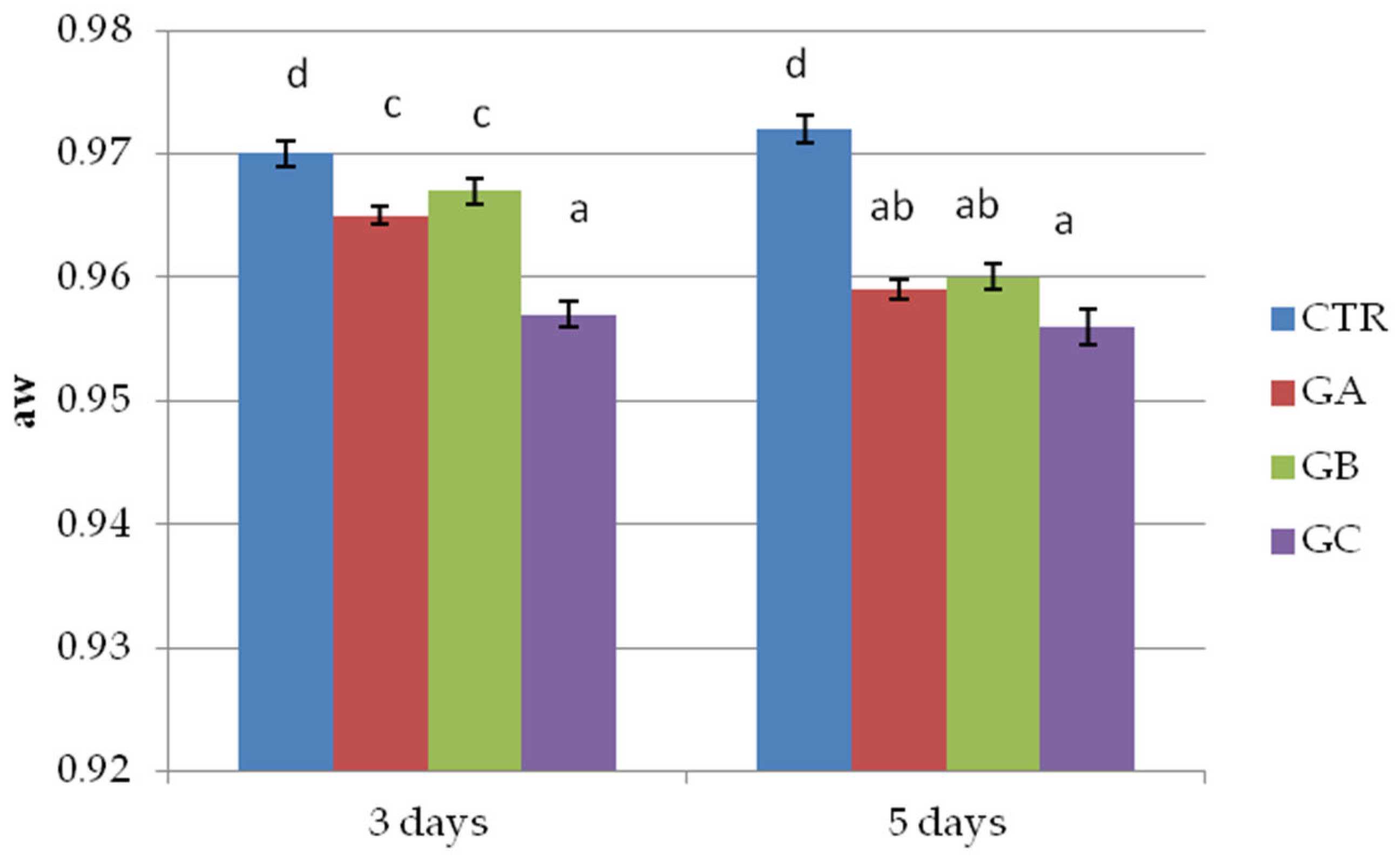

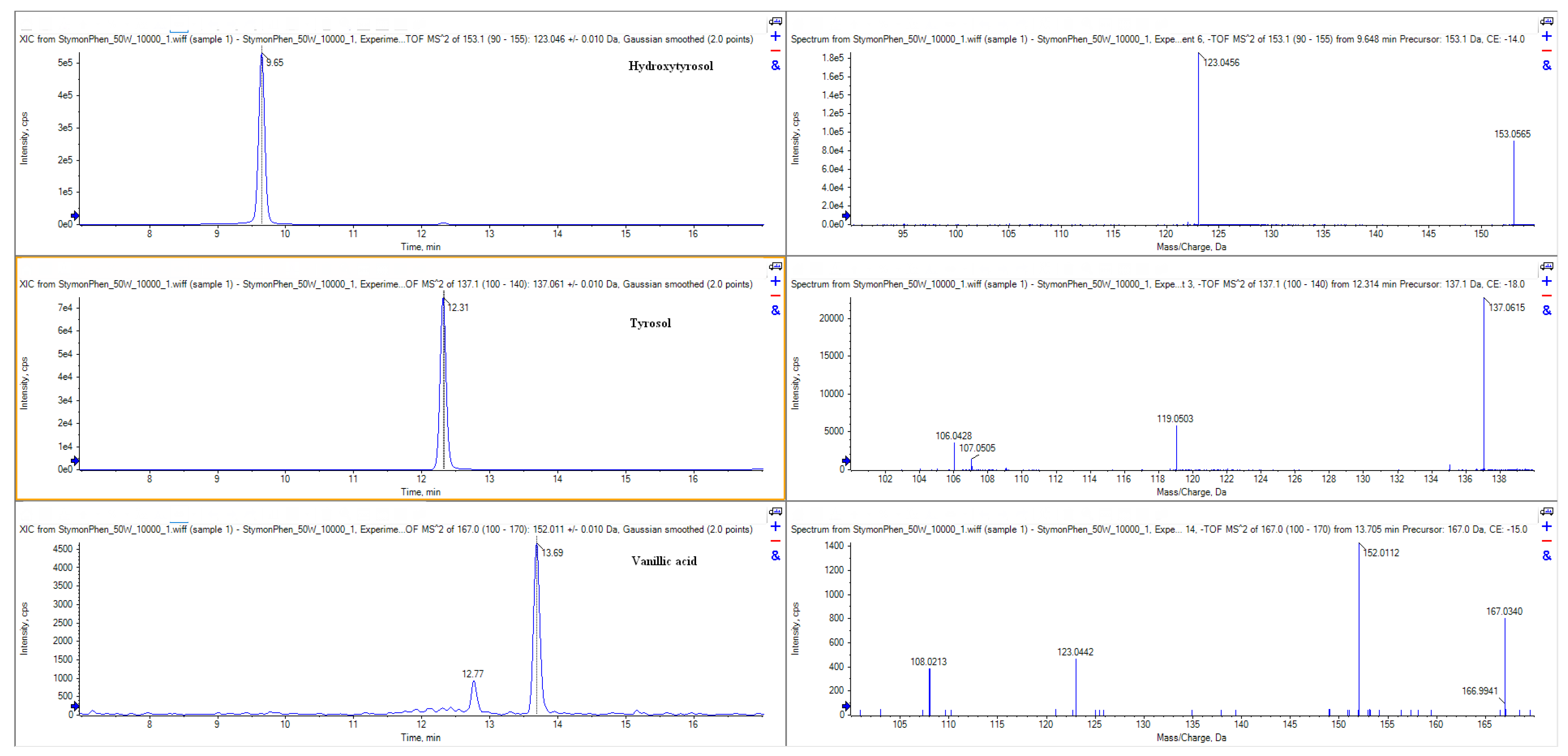

4.1.1. Polyphenolic Extract Characterization

4.1.2. Wild Boar Patty Formulation

4.2. Description of the Trials

4.3. Statistical Analyses

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Papageorgiou, C.S.; Lyri, P.; Xintaropoulou, I.; Diamantopoulos, I.; Zagklis, D.P.; Paraskeva, C.A. High-yield production of a rich-in-hydroxytyrosol extract from olive (Olea europaea) leaves. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Fernández, M.; Gonzalez-Ramirez, M.; Cerezo, A.B.; Troncoso, A.M.; Garcia-Parrilla, M.C. Hydroxytyrosol in foods: Analysis, food sources, EU dietary intake, and potential uses. Foods 2022, 11, 2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karkovic Markovic, A.; Toric, J.; Barbaric, M.; Jakobušic Brala, C. Hydroxytyrosol, Tyrosol and Derivatives and Their Potential Effects on Human Health. Molecules 2019, 24, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-del-Río, I.; López-Ibáñez, S.; Magadán-Corpas, P.; Fernández-Calleja, L.; Pérez-Valero, Á.; Tuñón-Granda, M.; Miguélez, E.M.; Villar, C.J.; Lombó, F. Terpenoids and polyphenols as natural antioxidant agents in food preservation. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obied, H.K.; Bedgood, D.R., Jr.; Prenzler, P.D.; Robards, K. Bioscreening of Australian olive mill waste extracts: Biophenol content, antioxidant, antimicrobial and molluscicidal activities. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2007, 45, 1238–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladhari, A.; Zarrelli, A.; Ghannem, M.; Ben Mimoun, M. Olive wastes as a high-potential by-product: Variability of their phenolic profiles, antioxidant and phytotoxic properties. Waste Biomass Valori. 2021, 12, 3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roila, R.; Sordini, B.; Esposto, S.; Ranucci, D.; Primavilla, S.; Valiani, A.; Taticchi, A.; Branciari, R.; Servili, M. Effect of the Application of a Green Preservative Strategy on Minced Meat Products: Antimicrobial Efficacy of Olive Mill Wastewater Polyphenolic Extract in Improving Beef Burger Shelf-Life. Foods 2022, 11, 2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitznerova, A.; Semjon, B.; Bartkovský, M.; Šuleková, M.; Nagy, J.; Klempová, T.; Marcinčák, S. Comparison of lipid profile and oxidative stability of vacuum-packed and long time-frozen fallow deer, wild boar, and pig meat. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranucci, D.; Roila, R.; Onofri, A.; Cambiotti, F.; Primavilla, S.; Miraglia, D.; Andoni, E.; Di Cerbo, A.; Branciari, R. Improving hunted wild boar carcass hygiene: Roles of different factors involved in the harvest phase. Foods 2021, 10, 1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, M.M.; Lidon, F.C. An overview on applications and side effects of antioxidant food additives. Emir. J. Food Agric. 2016, 28, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, E.; Spallarossa, A.; Comite, A.; Pagliero, M.; Guida, P.; Belotti, V.; Caviglia, D.; Schito, A.M. Valorization and potential antimicrobial use of olive mill wastewater (OMW) from Italian olive oil production. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Zamora, L.; Ros, G.; Nieto, G. Synthetic vs. Natural Hydroxytyrosol for Clean Label Lamb Burgers. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, G. Biological activities of three essential oils of the Lamiaceae family. Medicines 2017, 4, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanakis, C.M. Phenols Recovered from Olive Mill Wastewater as Additives in Meat Products. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 79, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papuc, C.; Goran, G.V.; Predescu, C.N.; Nicorescu, V.; Stefan, G. Plant Polyphenols as Antioxidant and Antibacterial Agents for Shelf-Life Extension of Meat and Meat Products: Classification, Structures, Sources, and Action Mechanisms. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2017, 16, 1243–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouarab Chibane, L.; Degraeve, P.; Ferhout, H.; Bouajila, J.; Oulahal, N. Plant Antimicrobial Polyphenols as Potential Natural Food Preservatives. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 1457–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez, M.; Morcuende, D.; Cava, R. Oxidative and colour changes in meat from three lines of free-range reared Iberian pigs slaughtered at 90 kg live weight and from industrial pig during refrigerated storage. Meat Sci. 2003, 65, 1139–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haak, L.; Raes, K.; De Smet, S. Effect of plant phenolics, tocopherol and ascorbic acid on oxidative stability of pork patties. J. Sci. Food Agricult. 2009, 89, 1360–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Carpena, J.G.; Morcuende, D.; Estévez, M. Avocado, sunflower and olive oils as replacers of pork back-fat in burger patties: Effect on lipid composition, oxidative stability and quality traits. Meat Sci. 2012, 90, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lara, M.S.; Gutierrez, J.I.; Timón, M.; Andrés, A.I. Evaluation of two natural extracts (Rosmarinus officinalis L. and Melissa officinalis L.) as antioxidants in cooked pork patties packed in MAP. Meat Sci. 2011, 88, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badr, H.M. Antioxidative activity of carnosine in gamma irradiated ground beef and beef patties. Food Chem. 2007, 104, 665–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, M.D.; Auqui, M.; Martí, N.; Linares, M.B. Effect of two different red grape pomace extracts obtained under different extraction systems on meat quality of pork burgers. LWT 2011, 44, 2238–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, J.M.; Sineiro, J.; Amado, I.R.; Franco, D. Influence of natural extracts on the shelf life of modified atmosphere-packaged pork patties. Meat Sci. 2014, 96, 526–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawashin, M.D.; Al-Juhaimi, F.; Ahmed, I.A.M.; Ghafoor, K.; Babiker, E.E. Physicochemical, microbiological and sensory evaluation of beef patties incorporated with destoned olive cake powder. Meat Sci. 2016, 122, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roila, R.; Stefanetti, V.; Carboni, F.; Altissimi, C.; Ranucci, D.; Valiani, A.; Branciari, R. Antilisterial activity of olive-derived polyphenols: An experimental study on meat preparations. Ital. J. Food Saf. 2024, 13, 12447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faustman, C.; Sun, Q.; Mancini, R.; Suman, S.P. Myoglobin and lipid oxidation interactions: Mechanistic bases and control. Meat Sci. 2010, 86, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, E.; De Castro, A.; Romero, C.; Brenes, M. Comparison of the concentrations of phenolic compounds in olive oils and other plant oils: Correlation with antimicrobial activity. J. Agricult. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 4954–4961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.K.; Penesyan, A.; Hassan, K.A.; Loper, J.E.; Paulsen, I.T. Effect of tannic acid on the transcriptome of the soil bacterium Pseudomonas protegens Pf-5. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 3141–3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altissimi, C.; Roila, R.; Ranucci, D.; Branciari, R.; Cai, D.; Paulsen, P. Preventing Microbial Growth in Game Meat by Applying Polyphenolic Extracts from Olive Mill Vegetation Water. Foods 2024, 13, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez Vaquero, M.J.; Aredes Fernández, P.A.; Manca de Nadra, M.C.; Strasser de Saad, A.M. Phenolic Compound Combinations on Escherichia coli Viability in a Meat System. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 6048–6052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruusunen, M.; Vainionpää, J.; Lyly, M.; Lähteenmäki, L.; Niemistö, M.; Ahvenainen, R.; Puolanne, E. Reducing the sodium content in meat products: The effect of the formulation in low-sodium ground meat patties. Meat Sci. 2005, 69, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiesteban-López, N.A.; Gómez-Salazar, J.A.; Santos, E.M.; Campagnol, P.C.B.; Teixeira, A.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Sosa-Morales, M.E.; Domínguez, R. Natural Antimicrobials: A Clean Label Strategy to Improve the Shelf Life and Safety of Reformulated Meat Products. Foods 2022, 11, 2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machácková, K.; Zelený, J.; Lang, D.; Vinš, Z. Wild Boar Meat as a Sustainable Substitute for Pork: A Mixed Methods Approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roila, R.; Valiani, A.; Servili, M.; Ranucci, D.; Galarini, R.; Ortenzi, R.; Primavilla, S.; Branciari, R. Control of Listeria monocytogenes on Frankfurters by Surface Treatment with Olive Mill Wastewater Polyphenolic Extract. Foods 2025, 14, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, B.D.; O’Sullivan, M.G.; Hamill, R.M.; Kerry, J.P. Effect of varying salt and fat levels on the sensory quality of beef patties. Meat Sci. 2012, 91, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashazadeh, H.; Zannou, O.; Ghellam, M.; Koca, I.; Galanakis, C.M.; Aldawoud, T.M.S. Optimization and Encapsulation of Phenolic Compounds Extracted from Maize Waste by Freeze-Drying, Spray-Drying, and Microwave-Drying Using Maltodextrin. Foods 2021, 10, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roila, R.; Primavilla, S.; Ranucci, D.; Galarini, R.; Paoletti, F.; Altissimi, C.; Valiani, A.; Branciari, R. The effects of encapsulation on the in vitro anti-clostridial activity of olive mill wastewater polyphenolic extracts: A promising strategy to limit microbial growth in food systems. Molecules 2024, 29, 1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Untersuchung von Lebensmitteln—Bestimmung Der Asche in Fleisch, Fleischerzeugnissen Und Wurstwaren—Gravimetrisches Verfahren (Referenzverfahren). In Amtliche Sammlung von Untersuchungsverfahren Nach §64 LFGB; Beuth: Berlin, Germany, 2017; p. L06.00-4.

- Untersuchung von Lebensmitteln—Bestimmung des Gesamtfettgehaltes in Fleisch und Fleischerzeugnissen—Gravimetrisches Verfahren nach Weibull-Stoldt—Referenzverfahren. In Amtliche Sammlung von Untersuchungsverfahren Nach §64 LFGB; Beuth: Berlin, Germany, 2014; p. L06.00-6.

- Untersuchung von Lebensmitteln—Bestimmung des Rohproteingehaltes in Fleisch und Fleischerzeugnissen; Titrimetrisches Verfahren nach Kjeldahl—Referenzverfahren. In Amtliche Sammlung von Untersuchungsverfahren Nach §64 LFGB; Beuth: Berlin, Germany, 2014; p. L06.00-7.

- Untersuchung von Lebensmitteln—Bestimmung des Wassergehaltes in Fleisch und Fleischerzeugnissen—Gravimetrisches Verfahren—Referenzverfahren. In Amtliche Sammlung von Untersuchungsverfahren Nach §64 LFGB; Beuth: Berlin, Germany, 2014; p. L06.00-3.

- Csadek, I.; Vankat, U.; Schrei, J.; Graf, M.; Bauer, S.; Pilz, B.; Schwaiger, K.; Smulders, F.J.M.; Paulsen, P. Treatment of Ready-To-Eat Cooked Meat Products with Cold Atmospheric Plasma to Inactivate Listeria and Escherichia coli. Foods 2023, 12, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CIE (Commission Internationale de L’Éclairage (International Commission on Illumination)). Recommendations on Uniform Color Spaces, Color-Difference Equations, Psychometric Color Terms; Commission Internationale de l’Eclairage: Paris, France, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Mokrzycki, W.S.; Tatol, M. Colour difference ∆E A survey. Mach. Graph. Vis. 2011, 20, 383. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 4833-2:2013; Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Enumeration of Microorganisms—Part 2: Colony Count at 30 °C by the Surface Plating Technique. ISO: Geneve, Switzerland, 2013.

- ISO 21528-2:2017; Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Detection and Enumeration of Enterobacteriaceae—Part 2: Colony-Count Technique. ISO: Geneve, Switzerland, 2017.

- Kielwein, G. Ein Nährboden Zur Selektiven Züchtung von Pseudomonaden Und Aeromonaden. Arch. Lebensmittelhyg. 1969, 20, 131–133. [Google Scholar]

- Witte, V.C.; Krause, G.F.; Bailey, M.E. A New Extraction Method for Determining 2-Thiobarbituric Acid Values of Pork and Beef During Storage. J. Food Sci. 1970, 35, 582–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PPE (g/100 g) | Moisture (g/100 g) | Crude Protein (g/100 g) | Crude Fat (g/100 g) | Ash (g/100 g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTR | 72.2 c ± 0.3 | 21.4 a ± 0.3 | 4.2 a ± 0.3 | 1.2 a ± 0.2 |

| LPPE | 71.6 b ± 0.3 | 21.3 a ± 0.2 | 4.3 a ± 0.2 | 1.1 a ± 0.1 |

| HPPE | 70.9 a ± 0.3 | 21.0 a ± 0.2 | 4.2 a ± 0.3 | 1.2 a ± 0.1 |

| Colour | CTR | LPPE | HPPE | SEM | p Value | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 Days | 3 Days | 5 Days | 0 Days | 3 Days | 5 Days | 0 Days | 3 Days | 5 Days | Group | Time | GxT | ||

| L* value | 40.04 a | 42.51 b | 43.29 c | 40.10 a | 42.06 ab | 42.90 bc | 40.34 a | 41.06 ab | 41.66 ab | 0.440 | 0.032 | <0.001 | 0.179 |

| a* value | 14.25 c | 13.10 b | 12.95 ab | 13.37 b | 14.12 bc | 14.90 c | 12.37 a | 13.69 b | 14.81 c | 0.309 | 0.018 | 0.002 | <0.001 |

| b* value | 13.37 b | 13.18 b | 13.21 b | 12.61 a | 13.48 b | 14.12 c | 12.19 a | 13.40 b | 14.21 c | 0.181 | 0.595 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Saturation index | 19.54 c | 18.59 bc | 18.54 bc | 18.43 b | 19.54 c | 20.54 d | 17.41 a | 19.17 c | 20.55 d | 0.305 | 0.039 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Hue angle | 43.29 | 45.31 | 45.86 | 43.30 | 43.77 | 43.47 | 44.60 | 44.38 | 43.82 | 0.677 | 0.062 | 0.333 | 0.154 |

| ΔE value | - | 3.39 ab | 4.87 c | - | 2.33 a | 4.33 c | - | 3.90 b | 4.50 c | 0.362 | 0.030 | <0.001 | 0.150 |

| Microbial Counts (Log cfu/g) | CTR | LPPE | HPPE | SEM | p Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Days | 5 Days | 3 Days | 5 Days | 3 Days | 5 Days | Group | Time | GxT | ||

| ACC | 6.96 c | 7.21 d | 6.45 b | 6.91 c | 6.25 a | 6.78 c | 0.068 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.106 |

| Enterobacteriaceae | 3.02 b | 3.43 c | 2.92 b | 3.06 b | 2.30 a | 2.33 a | 0.182 | <0.001 | 0.226 | 0.507 |

| Pseudomonas spp. | 3.68 c | 3.61 c | 3.37 bc | 3.61 c | 2.96 a | 3.18 b | 0.123 | <0.001 | 0.211 | 0.396 |

| TBARSs (mg MDA/kg) | CTR | LPPE | HPPE | SEM | p Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Days | 5 Days | 3 Days | 5 Days | 3 Days | 5 Days | Group | Time | GxT | ||

| Raw | 0.261 bA | 0.306 cA | 0.224 aA | 0.268 bA | 0.225 aA | 0.254 bA | 0.006 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.301 |

| Heated | 1.437 bB | 2.011 cB | 0.460 aB | 0.446 aB | 0.579 aB | 0.530 aB | 0.054 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Groups | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microbial Counts (log cfu/g) | CTR | GA | GB | GC | SEM | p Value | ||||||

| 3 Days | 5 Days | 3 Days | 5 Days | 3 Days | 5 Days | 3 Days | 5 Days | Group | Time | GxT | ||

| ACC | 6.80 e | 7.65 g | 6.33 c | 7.26 f | 6.01 b | 6.91 e | 5.41 a | 6.62 d | 0.077 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.094 |

| Enterobacteriaceae | 4.31 c | 4.81 d | 3.83 c | 4.77 d | 3.31 a | 3.68 b | 3.27 a | 3.63 b | 0.027 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Pseudomonas spp. | 4.70 e | 5.71 g | 4.44 d | 5.59 f | 3.83 b | 4.26 c | 3.71 b | 3.58 a | 0.043 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Groups | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Texture Profile Analyses | CTR | GA | GB | GC | SEM | p Value | ||||||

| 3 Days | 5 Days | 3 Days | 5 Days | 3 Days | 5 Days | 3 Days | 5 Days | Group | Time | GxT | ||

| Hardness (N) | 29.32 a | 99.61 d | 38.78 a | 116.26 e | 31.89 a | 82.12 c | 51.64 b | 136.24 f | 3.252 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Toughness (mJ) | 87.05 a | 350.02 b | 130.50 a | 547.22 c | 72.87 a | 329.80 b | 137.35 a | 625.12 c | 26.58 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Springiness | 0.917 b | 0.742 a | 0.955 b | 0.867 ab | 0.922 b | 0.763 a | 0.935 b | 0.770 a | 0.040 | 0.211 | <0.001 | 0.684 |

| Chewiness (N) | 18.33 a | 37.54 b | 27.78 a | 42.28 b | 20.79 ab | 30.93 b | 36.98 b | 38.17 b | 4.940 | 0.043 | 0.002 | 0.227 |

| Cooking Loss (%) | 10.53 a | 13.53 bc | 11.54 ab | 14.14 cd | 10.09 a | 12.69 b | 13.19 b | 15.81 d | 0.590 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.982 |

| N° | Analyte | RT (Min) | Molecular Formula | Precursor Ion (m/z) | Fragment Ion (m/z) | DP (V) | CE (V) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hydroxytyrosol | 9.6 | C8H10O3 | 153.0557 | 123.0455 | 80 | 14 |

| 2 | Tyrosol | 12.3 | C8H10O2 | 137.0608 | 119.0520 | 90 | 18 |

| 3 | Vanillic acid | 13.7 | C8H8O4 | 167.0350 | 152.0111 | 70 | 15 |

| 4 | Vanillin | 14.9 | C8H8O3 | 151.0401 | 136.0166 | 60 | 14 |

| 5 | p-coumaric acid | 15.4 | C9H8O3 | 163.0401 | 119.0500 | 60 | 14 |

| 6 | Verbascoside | 16.5 | C29H36O15 | 623.1981 | 161.0251 | 90 | 38 |

| 7 | Oleuropein | 17.3 | C25H32O13 | 539.1770 | 307.0824 | 100 | 27 |

| 8 | Pinoresinol | 17.9 | C20H22O6 | 357.1344 | 151.0410 | 80 | 20 |

| 9 | Luteolin | 18.0 | C15H10O6 | 285.0405 | 133.0293 | 110 | 36 |

| 10 | Oleuropein aglycone | 18.1 | C19H22O8 | 377.1242 | 307.0824 | 80 | 14 |

| 11 | Apigenin | 18.2 | C15H10O5 | 269.0456 | 117.0343 | 110 | 35 |

| Extract | Hydroxytyrosol (mg/g) | Tyrosol (mg/g) | Vanillic Acid (mg/g) | Sum (mg/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPE * | 16.9 | 4.78 | 0.24 | 21.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Altissimi, C.; Ranucci, D.; Bauer, S.; Branciari, R.; Galarini, R.; Servili, M.; Roila, R.; Paulsen, P. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Effects of Polyphenolic Extracts from Olive Mill Vegetation Water on Wild Boar Meat Patties. Molecules 2025, 30, 4692. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244692

Altissimi C, Ranucci D, Bauer S, Branciari R, Galarini R, Servili M, Roila R, Paulsen P. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Effects of Polyphenolic Extracts from Olive Mill Vegetation Water on Wild Boar Meat Patties. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4692. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244692

Chicago/Turabian StyleAltissimi, Caterina, David Ranucci, Susanne Bauer, Raffaella Branciari, Roberta Galarini, Maurizio Servili, Rossana Roila, and Peter Paulsen. 2025. "Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Effects of Polyphenolic Extracts from Olive Mill Vegetation Water on Wild Boar Meat Patties" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4692. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244692

APA StyleAltissimi, C., Ranucci, D., Bauer, S., Branciari, R., Galarini, R., Servili, M., Roila, R., & Paulsen, P. (2025). Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Effects of Polyphenolic Extracts from Olive Mill Vegetation Water on Wild Boar Meat Patties. Molecules, 30(24), 4692. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244692