Tetraselmis chuii as Source of Bioactive Compounds Against Helicobacter pylori: An Integrated Proteomic and Bioactivity Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

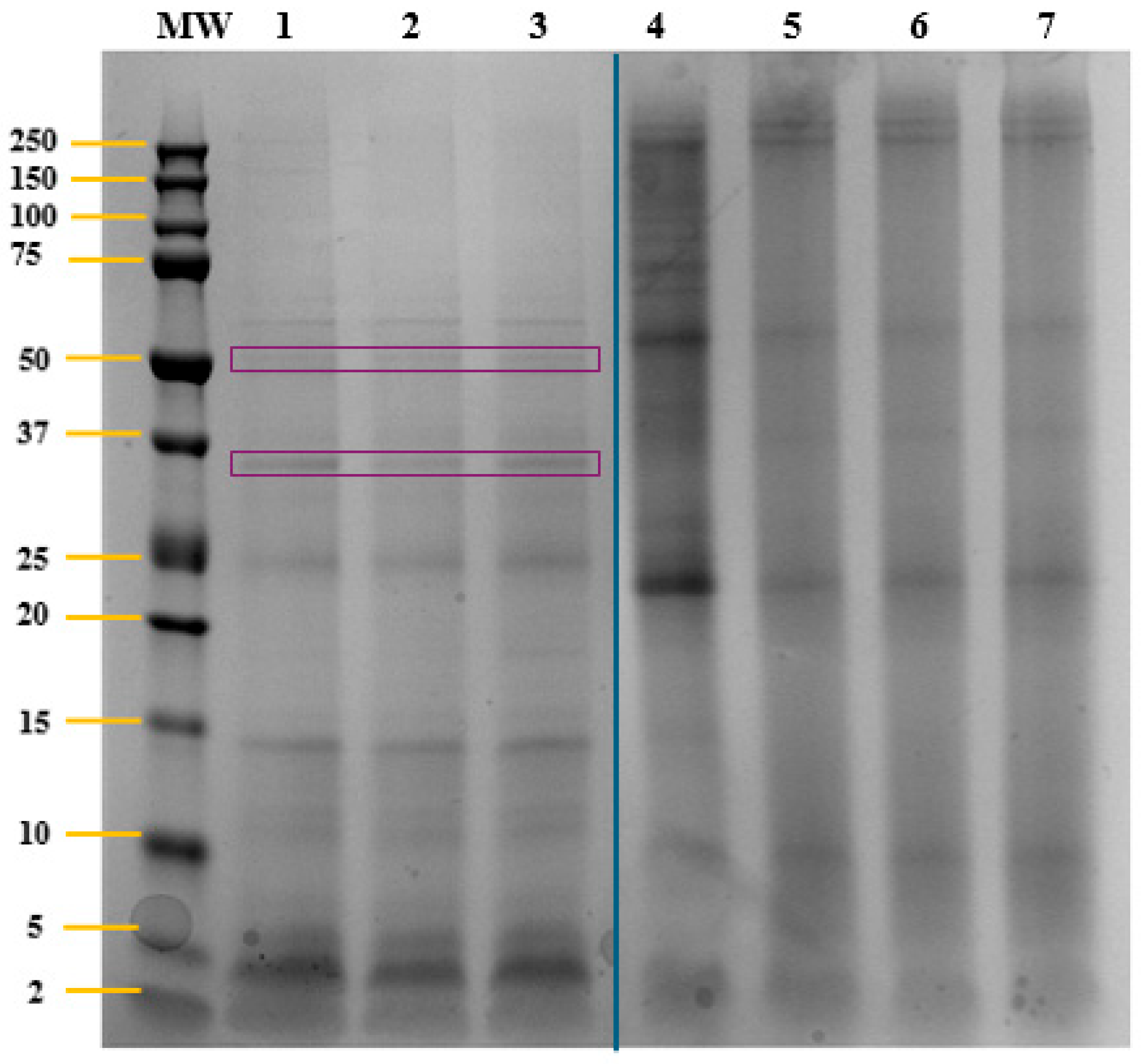

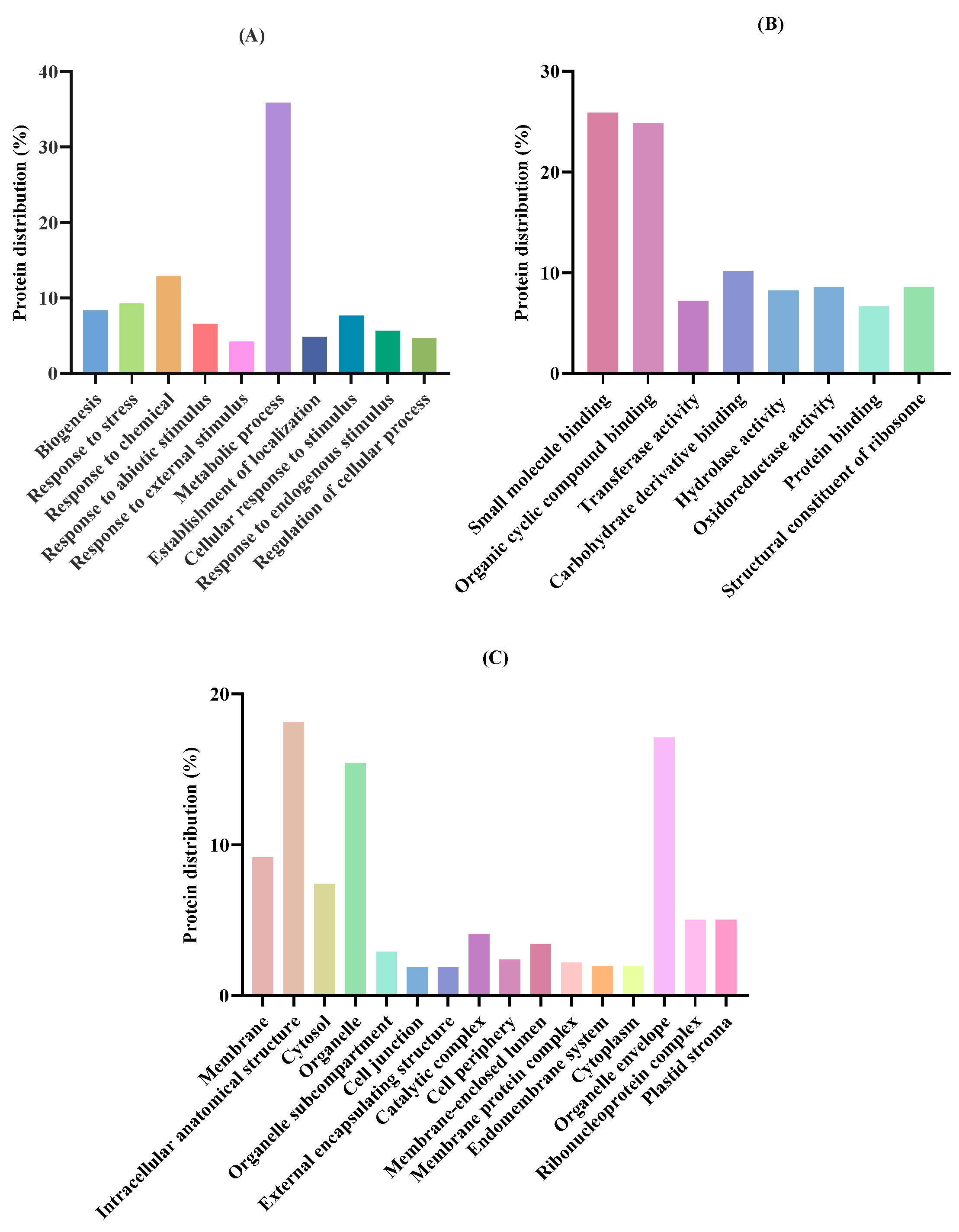

2.1. Characterization of T. chuii Proteins

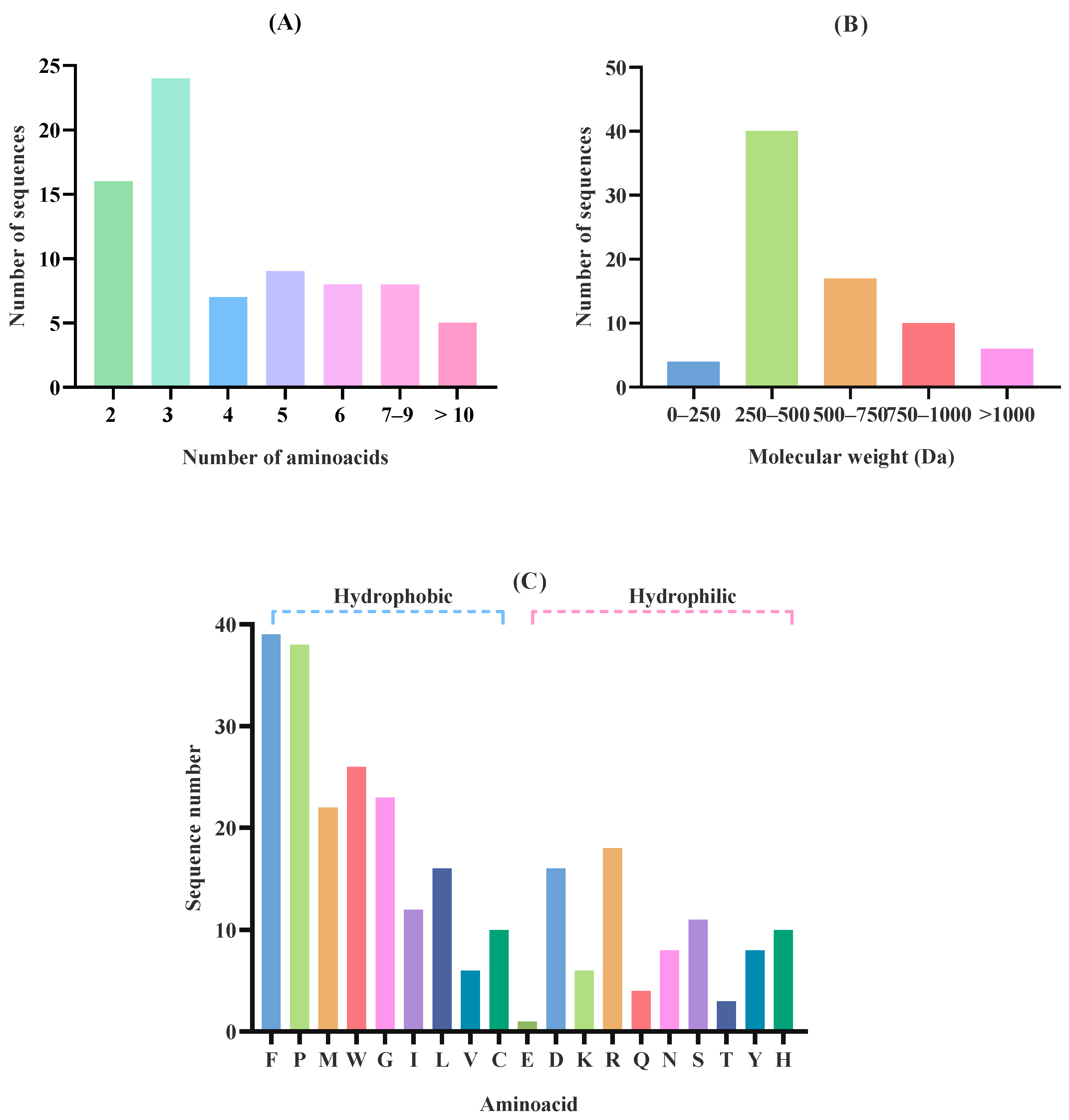

2.2. Effect of In Silico Gastric Digestion on Peptide Release

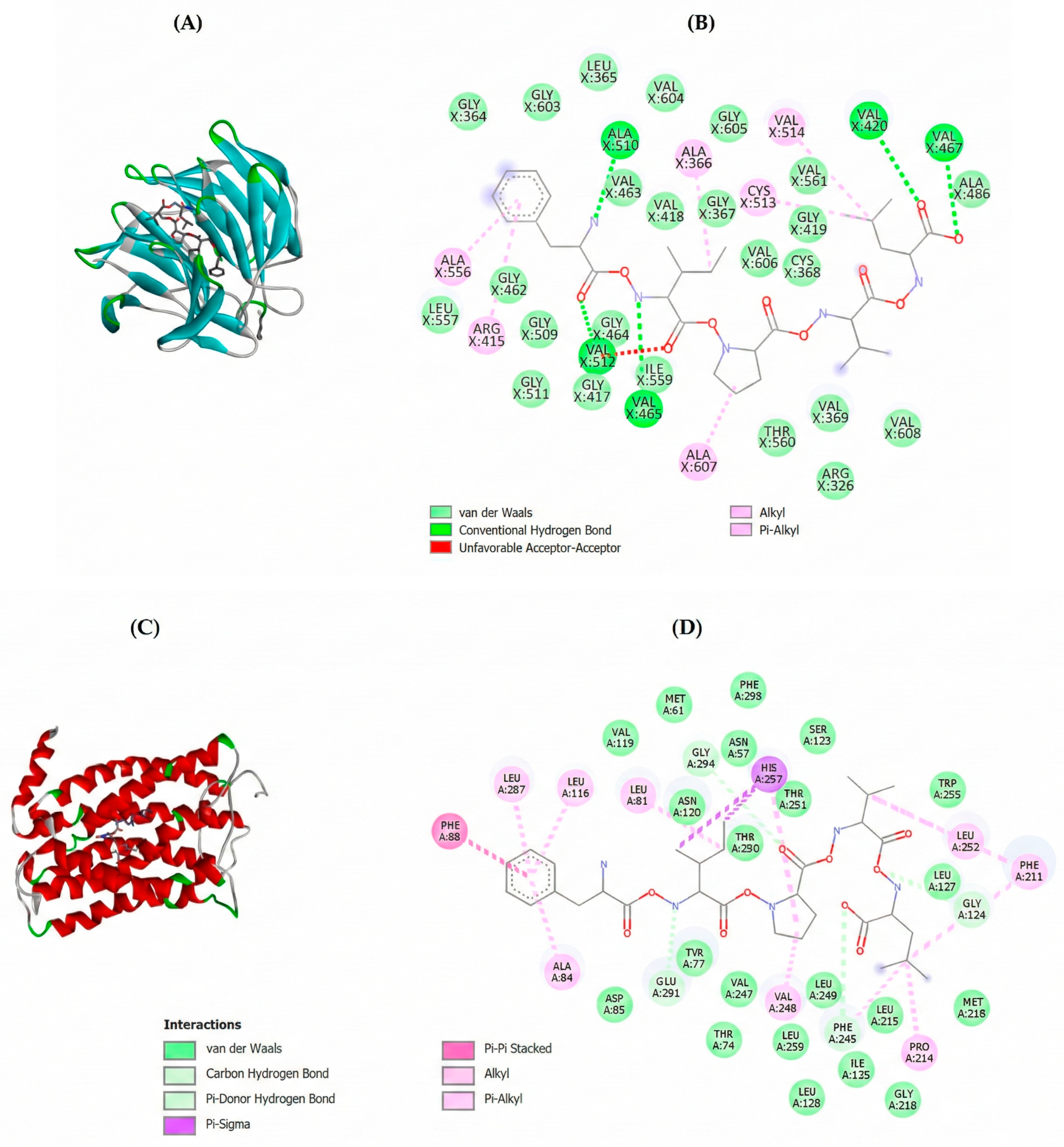

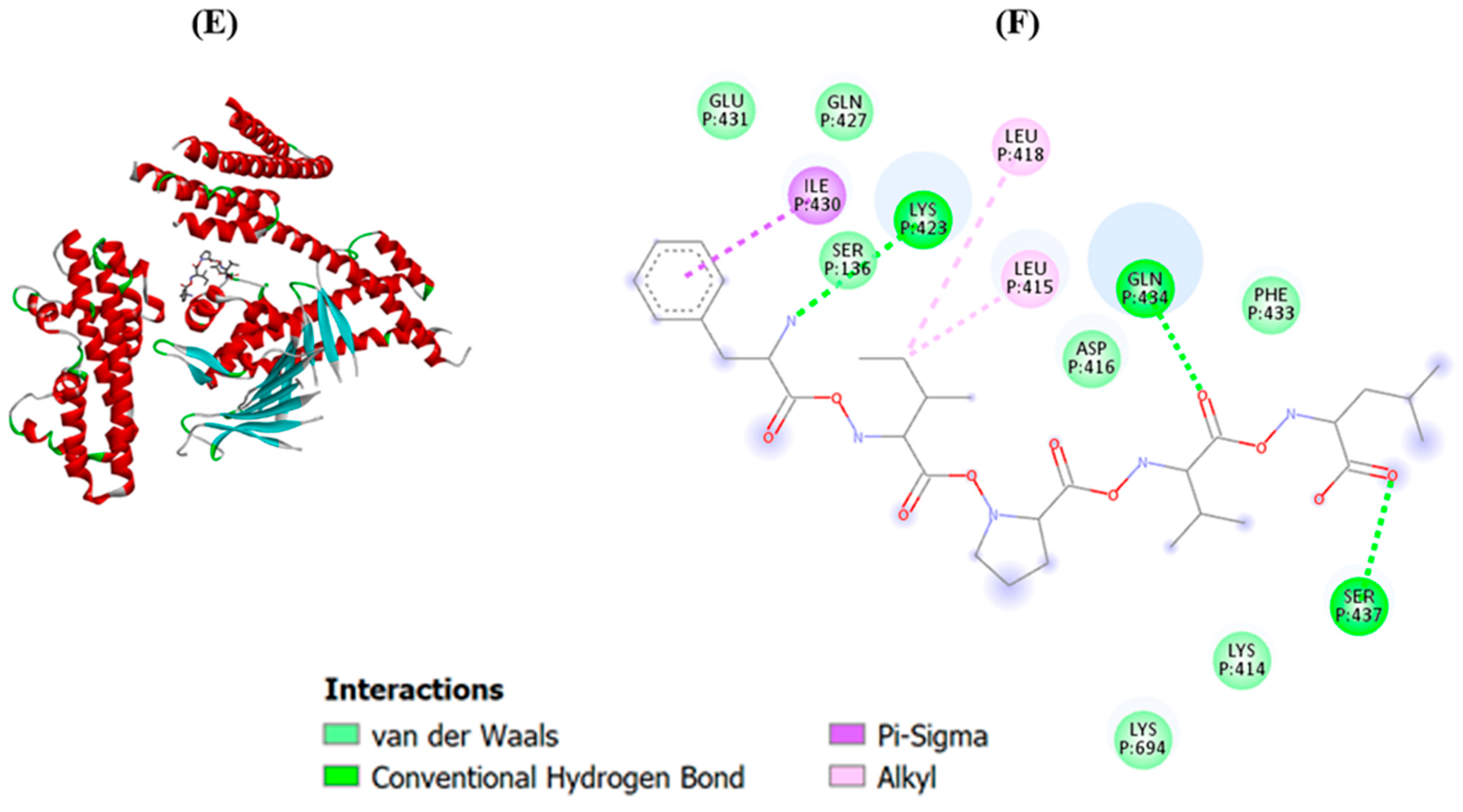

2.3. Molecular Docking of Potential Bioactive Peptides

2.4. Effect of In Vitro Orogastric Digestion on Bioactivity of T. chuii

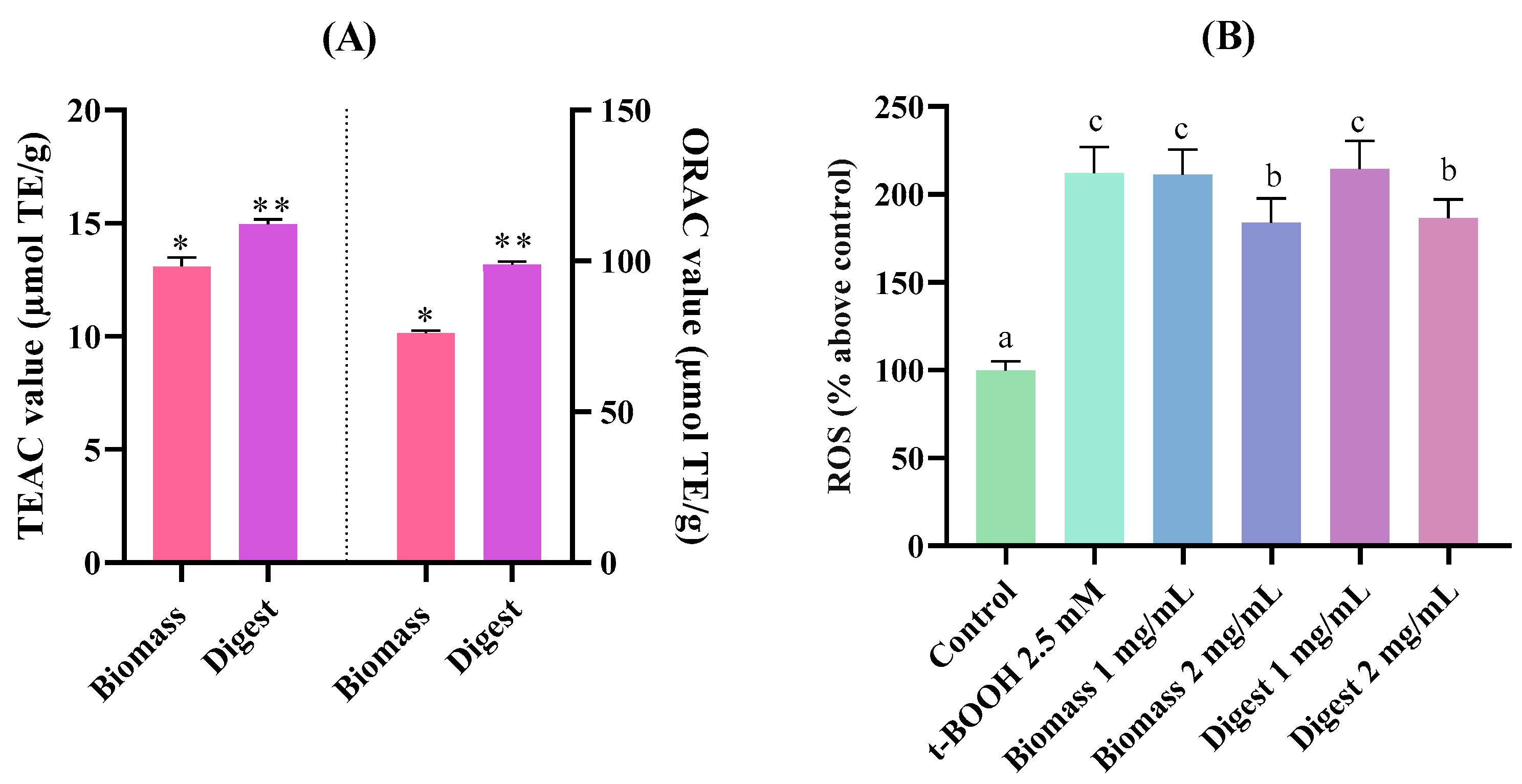

2.4.1. Antioxidant Capacity Through Biochemical Assays and a Gastric Cell Model

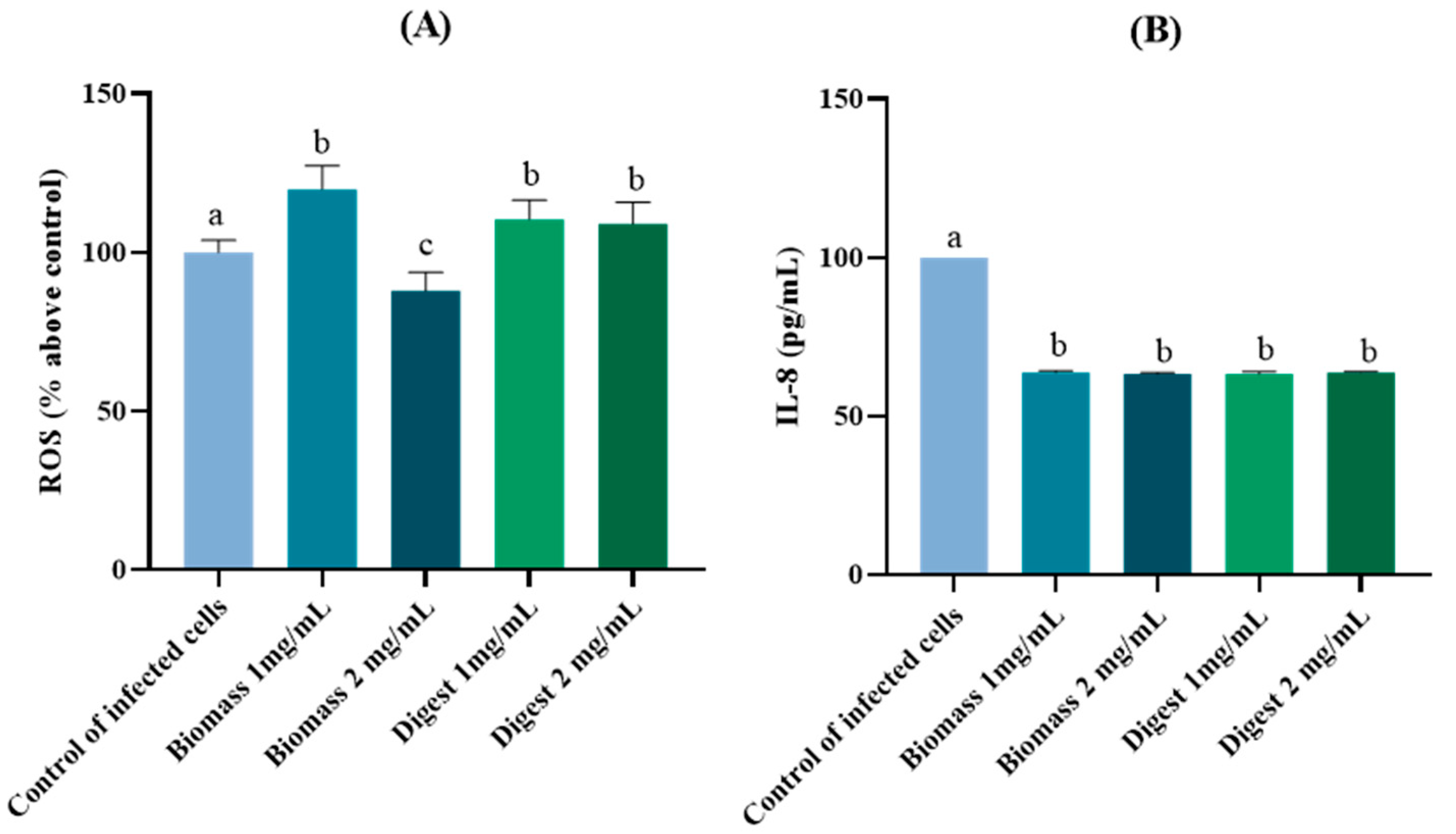

2.4.2. Protective Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects in H. pylori-Infected AGS Cells

2.4.3. Antibacterial Activity

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Microalgae Biomass and Its Pre-Treatment

3.2. Protein Characterization of T. chuii

3.3. Proteomic and Functional Analysis

3.4. In Silico Orogastric Digestion of Microalgae Proteins: Potential Bioactive Effects

3.5. Molecular Docking

3.6. In Vitro Simulated Orogastric Digestion

3.7. Biological Properties of T. chuii Biomass and Its Orogastric Digests

3.7.1. Antioxidant Activity (ABTS and ORAC Assays)

3.7.2. Antibacterial Activity Against H. pylori

3.7.3. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects in Human Gastric Cells

Human Gastric Cells (AGS) Culture

Cell Viability

Effects on Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Production

Effects on Interleukin (IL)-8 Production

3.8. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Musa, M.; Ayoko, G.A.; Ward, A.; Rösch, C.; Brown, R.J.; Rainey, T.J. Factors affecting microalgae production for biofuels and the potentials of chemometric methods in assessing and optimizing productivity. Cells 2019, 8, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahendran, M.S.; Dhanapal, A.C.T.A.; Wong, L.S.; Kasivelu, G.; Djearamane, S. Microalgae as a potential source of bioactive food compounds. Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. 2021, 9, 917–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuorro, A.; Lavecchia, R.; Contreras-Ropero, J.E.; Martínez, J.B.G.; Barajas-Ferreira, C.; Barajas-Solano, A.F. Natural antimicrobial agents from algae: Current advances and future directions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, H.; Silva, J.; Santos, T.; Gangadhar, K.N.; Raposo, A.; Nunes, C.; Coimbra, M.A.; Gouveia, L.; Barreira, L.; Varela, J. Nutritional potential and toxicological evaluation of Tetraselmis sp. CtP4 microalgal biomass produced in industrial photobioreactors. Molecules 2019, 24, 3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, A.C.; Amaro, H.M.; Malcata, F.X. Microalgae as sources of high added-value compounds—A brief review of recent work. Biotechnol. Prog. 2011, 27, 597–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulombier, N.; Jauffrais, T.; Lebouvier, N. Antioxidant compounds from microalgae: A review. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrot, R.; Barylski, J.; Nowicki, G.; Broniarczyk, J.; Buchwald, W.; Goździcka-Józefiak, A. Plant antimicrobial peptides. Folia Microbiol. 2014, 59, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neshani, A.; Zare, H.; Akbari Eidgahi, M.R.; Hooshyar Chichaklu, A.; Movaqar, A.; Ghazvini, K. Review of antimicrobial peptides with anti-Helicobacter pylori activity. Helicobacter 2019, 24, e12555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, T.S.; Kim, S.K. Down-regulation of histamine-induced endothelial cell activation as potential anti-atherosclerotic activity of peptides from Spirulina maxima. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 50, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Bai, L.; Zhu, L.; Yang, L.; Zhang, X. Marine algae-derived bioactive peptides for human nutrition and health. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 9211–9222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, F.; Wong, G.; Román, T.; Cárdenas, C.; Alvárez, C.; Schmitt, P.; Albericio, F.; Rojas, V. Identification of antimicrobial peptides from the microalgae Tetraselmis suecica (Kylin) Butcher and bactericidal activity improvement. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skjånes, K.; Aesoy, R.; Herfindal, L.; Skomedal, H. Bioactive peptides from microalgae: Focus on anti-cancer and immuno-modulating activity. Physiol. Plant 2021, 173, 612–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, L.; Qiu, Z.; Zhao, R.; Zheng, Z.; Qiao, X. Advancement and prospects of production, transport, functional activity and structure-activity relationship of food-derived angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory peptides. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 1437–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Casas, D.E.; Aguilar, C.N.; Ascacio-Valdés, J.A.; Rodríguez-Herrera, R.; Chávez-González, M.L.; Flores-Gallegos, A.C. Enzymatic hydrolysis and microbial fermentation: The most favorable biotechnological methods for the release of bioactive peptides. Food Chem. Mol. Sci. 2021, 3, 100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Wang, Z.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, W. Marine products as a promising resource of bioactive peptides: Update of extraction strategies and their physiological regulatory effects. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 3081–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohn, T.; Carriere, F.; Day, L.; Deglaire, A.; Egger, L.; Freitas, D.; Golding, M.; Le Feunteun, S.; Macierzanka, A.; Menard, O.; et al. Correlation between in vitro and in vivo data on food digestion. What can we predict with static in vitro digestion models? Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 2239–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Fátima Garcia, B.; de Barros, M.; de Souza Rocha, T. Bioactive peptides from beans with the potential to decrease the risk of developing noncommunicable chronic diseases. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 2003–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, C.; Haslam, N.J.; Pollastri, G.; Shields, D.C. Towards the improved discovery and design of functional peptides: Common features of diverse classes permit generalized prediction of bioactivity. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e45012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, M.; Mora, L.; Lucakova, S. Identification of bioactive peptides from Nannochloropsis oculata using a combination of enzymatic treatment, in silico analysis and chemical synthesis. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Chen, X.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, L.; Tang, Y.J.; Wei, D. Antihypertensive effects, molecular docking study, and isothermal titration calorimetry assay of angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitory peptides from Chlorella vulgaris. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 1359–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuetz, A.N.; Theel, E.S.; Cole, N.C.; Rothstein, T.E.; Gordy, G.G.; Patel, R. Testing for Helicobacter pylori in an era of antimicrobial resistance. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2024, 62, e00732-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadhim, A.S.; Al-Karawi, A.S. Insights into the pathogenesis, virulence factors, and diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori: A comprehensive review. Am. J. Biosci. Bioinform. 2023, 2, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, S.; Fernández-Tomé, S.; Galvez, A.; Hernández-Ledesma, B. Evaluation of the multifunctionality of soybean proteins and peptides in immune cell models. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paterson, S.; Majchrzak, M.; Alexandru, D.; Di Bella, S.; Fernández-Tomé, S.; Arranz, E.; de la Fuente, M.A.; Gómez-Cortés, P.; Hernández-Ledesma, B. Impact of the biomass pretreatment and simulated gastrointestinal digestion on the digestibility and antioxidant activity of microalgae Chlorella vulgaris and Tetraselmis Chuii. Food Chem. 2024, 453, 139686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Chen, X.; Sato, T.; Rankin, S.A.; Tsuji, R.F.; Ge, Y. Purification and high-resolution top-down mass spectrometric characterization of human salivary α-amylase. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 3339–3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejano, L.A.; Peralta, J.P.; Yap, E.E.S.; Panjaitan, F.C.A.; Chang, Y.W. Prediction of bioactive peptides from Chlorella sorokiniana proteins using proteomic techniques in combination with bioinformatics analyses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Ma, B.; Zhang, K. SPIDER: Software for protein identification from sequence tags with de novo sequencing error. J. Bioinform. Comput. Biol. 2005, 3, 697–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.H.U.; Yi, E.K.J.; Amin, N.D.M.; Ismail, M.N. An empirical analysis of Sacha Inchi (Plukenetia volubilis L.) seed proteins and their applications in the food and biopharmaceutical industries. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2024, 196, 4823–4836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, S.; Alonso-Pintre, L.; Morato-López, E.; González de la Fuente, S.; Gómez-Cortés, P.; Hernández-Ledesma, B. Microalga Nannochloropsis gaditana as a sustainable source of bioactive peptides: A proteomic and in silico approach. Foods 2025, 14, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gass, J.; Khosla, C. Prolyl Endopeptidases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2007, 64, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadar, M.; Shahali, Y.; Chakraborty, S.; Prasad, M. Antiinflammatory peptides: Current knowledge and promising prospects. Inflamm. Res. 2019, 68, 125–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khavari, F.; Saidijam, M.; Taheri, M.; Nouri, F. Microalgae: Therapeutic potentials and applications. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 4757–4765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romay, C.; González, R.; Ledón, N.; Remirez, D.; Rimbau, V. C-Phycocyanin: A biliprotein with antioxidant, anti-Inflammatory and neuroprotective effects. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2003, 4, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, A.; Mishra, S.; Pawar, R.; Ghosh, P.K. Purification and characterization of C-Phycocyanin from Spirulina platensis and its anti-Inflammatory activity. Biotechnology 2021, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, W.H.; Rouault, T.A. Functions of mitochondrial ISCU and cytosolic ISCU in iron-sulfur cluster biogenesis and iron homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 34560–34569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Cao, X.; Yao, C.; Xue, S.; Xiu, Z. Protein-protein interaction network of the marine microalga Tetraselmis subcordiformis: Prediction and application for starch metabolism analysis. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 41, 1287–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, R.P.; Conniff, A.S.; Uversky, V.N. Comparative study of structures and functional motifs in lectins from the commercially important photosynthetic microorganisms. Biochimie 2022, 201, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Chang, E.; Yu, X.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Q.; Cao, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Fu, A.; Xu, M. Molecular characterization of magnesium chelatase in soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.]. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, T.J.; Hatch, M.D. Properties and mechanism of action of pyruvate, phosphate dikinase from leaves. Biochem. J. 1969, 114, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.X.; Liu, X.L.; Zheng, X.Q.; Wang, X.J.; He, J.F. Preparation of antioxidative corn protein hydrolysates, purification and evaluation of three novel corn antioxidant peptides. Food Chem. 2016, 204, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.F.; Wang, B.; Hu, F.Y.; Wang, Y.M.; Zhang, B.; Deng, S.G.; Wu, C.W. Purification and identification of three novel antioxidant peptides from protein hydrolysate of bluefin leatherjacket (Navodon septentrionalis) skin. Food Res. Int. 2015, 73, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Gonzalez De Mejia, E. A new frontier in soy bioactive peptides that may prevent age-related chronic diseases. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2005, 4, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Ma, S.; Li, J. Purification and characterization of three antioxidant peptides from protein hydrolysate of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) skin. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 16, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmadi, B.H.; Ismail, A. Antioxidative peptides from food proteins: A review. Peptides 2010, 31, 1949–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parreira, P.; Duarte, M.F.; Reis, C.A.; Martins, M.C.L. Helicobacter pylori infection: A brief overview on alternative natural treatments to conventional therapy. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 42, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Chen, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, J.; An, J.; Liu, X. Anti-inflammatory function of plant-derived bioactive peptides: A review. Foods 2022, 11, 2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellezza, I.; Giambanco, I.; Minelli, A.; Donato, R. Nrf2-Keap1 signaling in oxidative and reductive stress. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2018, 1865, 721–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klebanoff, S.J. Myeloperoxidase: Friend and foe. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2005, 77, 598–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterbourn, C.C.; Kettle, A.J. Redox reactions and microbial killing in the neutrophil phagosome. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013, 18, 642–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Zhuang, W.; Liu, X.; Wu, J.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, C.; Zhang, H. Targeting CXCR1 alleviates hyperoxia-induced lung injury through promoting glutamine metabolism. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 112745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhayni, K.; Zibara, K.; Issa, H.; Kamel, S.; Bennis, Y. Targeting CXCR1 and CXCR2 receptors in cardiovascular diseases. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 237, 108257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jablonska, J.; Wu, C.-F.; Andzinski, L.; Leschner, S.; Weiss, S. CXCR2-mediated tumor-associated neutrophil recruitment is regulated by IFN-β. Int. J. Cancer 2014, 134, 1346–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadakos, K.S.; Sougleri, I.S.; Mentis, A.F.; Hatziloukas, E.; Sgouras, D.N. Presence of terminal EPIYA phosphorylation motifs in Helicobacter pylori CagA contributes to IL-8 secretion, irrespective of the number of repeats. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freire de Melo, F.; Marques, H.S.; Rocha Pinheiro, S.L.; Lemos, F.F.B.; Silva Luz, M.V. Influence of Helicobacter pylori oncoprotein CagA in gastric cancer: A critical-reflective analysis. World J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 13, 866–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cover, T.L.; Blanke, S.R. Helicobacter pylori VacA, a paradigm for toxin multifunctionality. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005, 3, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebert, B.; Fischer, W.; Weiss, E.; Hoffmann, R.; Haas, R. Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin inhibits T lymphocyte activation. Science 2003, 301, 1099–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.G.; Dos Santos, R.N.; Oliva, G.; Andricopulo, A.D. Molecular docking and structure-based drug design strategies. Molecules 2015, 20, 13384–13421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, K.; Yamamoto, M. The KEAP1–NRF2 System in cancer. Front. Oncol. 2017, 7, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waugh, D.J.J.; Wilson, C. The interleukin-8 pathway in cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 6735–6741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hébert, C.A.; Vitangcol, R.V.; Baker, J.B. Scanning mutagenesis of interleukin-8 identifies a cluster of residues required for receptor binding. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 18989–18994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, M.W.; Raghuwanshi, S.K.; Grant, D.J.; Jala, V.R.; Rajarathnam, K.; Richardson, R.M. Differential activation and regulation of CXCR1 and CXCR2 by CXCL8 monomer and dimer. J. Immunol. 2009, 183, 3425–3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Zhao, M.; Shi, F.; Zheng, S.; Xiong, L.; Zheng, L. A review of signal pathway induced by virulent protein CagA of Helicobacter pylori. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1062803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnhold, J. The dual role of myeloperoxidase in immune response. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, S.; Farooq, S.M.; Castelvetere, M.P.; Hou, Y.; Gao, J.-L.; Navarro, J.V.; Oupicky, D.; Sun, F.; Li, C. A Chemokine receptor CXCR2 macromolecular complex regulates neutrophil functions in inflammatory diseases. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 5744–5755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; He, B.; Cho, W.C.; Pan, Y.; Chen, J.; Ying, H.; Wang, F.; Lin, K.; Peng, H.; Wang, S. A systematic review on the association between the Helicobacter pylori vacA i genotype and gastric disease. FEBS Open Bio 2016, 6, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, C.; Galasso, C.; Orefice, I.; Nuzzo, G.; Luongo, E.; Cutignano, A.; Romano, G.; Brunet, C.; Fontana, A.; Ianora, A. The green microalga Tetraselmis suecica reduces oxidative stress and induces repairing mechanisms in human cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocksedge, S.P.; Mantecón, L.; Castaño, E.; Infante, C.; Bailey, S.J. The potential of superoxide dismutase-rich Tetraselmis chuii as a promoter of cellular health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoumifeshani, B.; Abedian Kenari, A.; Sottorff, I.; Crüsemann, M.; Amiri Moghaddam, J. Identification and evaluation of antioxidant and anti-aging peptide fractions from enzymatically hydrolyzed proteins of Spirulina platensis and Chlorella vulgaris. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.P.; Ni, H.Z.; Pannerchelvan, S.; Halim, M.; Tan, J.S.; Kasan, N.A.; Mohamed, M.S. Optimization of trace metal composition utilizing Taguchi orthogonal array enhances biomass and superoxide dismutase production in Tetraselmis chuii under mixotrophic condition: Implications for antioxidant formulations. Int. Microbiol. 2025, 28, 1979–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galasso, C.; Piscitelli, C.; Brunet, C.; Sansone, C. New in vitro model of oxidative stress: Human prostate cells injured with 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) for the screening of antioxidants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Vikash, V.; Ye, Q.; Wu, D.; Liu, Y.; Dong, W. ROS and ROS-mediated cellular signaling. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2016, 2016, 4350965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Lammi, C.; Boschin, G.; Arnoldi, A.; Aiello, G. Recent advances in microalgae peptides: Cardiovascular health benefits and analysis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 11825–11838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chacón-Lee, T.L.; González-Mariño, G.E. Microalgae for “healthy” foods—Possibilities and challenges. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2010, 9, 655–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remize, M.; Brunel, Y.; Silva, J.L.; Berthon, J.-Y.; Filaire, E. Microalgae n-3 PUFAs production and use in food and feed industries. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goiris, K.; Muylaert, K.; Fraeye, I.; Foubert, I.; De Brabanter, J.; De Cooman, L. Antioxidant potential of microalgae in relation to their phenolic and carotenoid content. J. Appl. Phycol. 2012, 24, 1477–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez-Moscoso, C.A.; Merlano, J.A.R.; Olivera Gálvez, A.; Volcan Almeida, D. Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) from microalgae as an alternative to conventional antibiotics in aquaculture. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2025, 55, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira Júnior, N.G.; Souza, C.M.; Buccini, D.F.; Cardoso, M.H.; Franco, O.L. Antimicrobial peptides: Structure, functions and translational applications. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2025, 23, 687–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Niu, M.; Xue, T.; Ma, L.; Gu, X.; Wei, G.; Li, F.; Wang, C. Development of antibacterial peptides with efficient antibacterial activity, low toxicity, high membrane disruptive activity and a synergistic antibacterial effect. J. Mater. Chem. B 2022, 10, 1858–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desbois, A.P.; Smith, V.J. Antibacterial free fatty acids: Activities, mechanisms of action and biotechnological potential. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 85, 1629–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Torres-Sánchez, E.; Morato, E.; Hernández-Ledesma, B.; Gutiérrez, L.-F. Proteomic analysis of the major alkali-soluble Inca Peanut (Plukenetia volubilis) proteins. Foods 2024, 13, 3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchiz, Á.; Morato, E.; Rastrojo, A.; Camacho, E.; De la Fuente, S.G.; Marina, A.; Aguado, B.; Requena, J.M. The experimental proteome of Leishmania infantum promastigote and its usefulness for improving gene annotations. Genes 2020, 11, 1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shevchenko, A.; Wilm, M.; Vorm, O.; Jensen, O.N.; Podtelejnikov, A.V.; Neubauer, G.; Shevchenko, A.; Mortensen, P.; Mann, M. A strategy for identifying gel-separated proteins in sequence databases by MS alone. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1996, 24, 893–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, R.; Pisa, D.; Marina, A.I.; Morato, E.; Rábano, A.; Rodal, I.; Carrasco, L. Evidence for fungal infection in cerebrospinal fluid and brain tissue from patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2015, 11, 546–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, N.H.; Zhang, X.; Xin, L.; Shan, B.; Li, M. De novo peptide sequencing by deep learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 8247–8252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.H.; Rahman, M.Z.; He, L.; Xin, L.; Shan, B.; Li, M. Complete de novo assembly of monoclonal antibody sequences. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, N.H.; Qiao, R.; Xin, L.; Chen, X.; Liu, C.; Zhang, X.; Shan, B.; Ghodsi, A.; Li, M. Deep learning enables de novo peptide sequencing from data-independent-acquisition mass spectrometry. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillet, N. Rapid Peptides Generator: Fast and efficient in silico protein digestion. NAR Genom. Bioinform. 2020, 2, lqz004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, D.; Jiao, L.; Wang, R.; Zhao, Y.; Hao, Y.; Liang, G. Prediction of antioxidant peptides using a quantitative structure−activity relationship predictor (AnOxPP) based on bidirectional long short-term memory neural network and interpretable amino acid descriptors. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 154, 106591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawde, U.; Chakraborty, S.; Waghu, F.H.; Barai, R.S.; Khanderkar, A.; Indraguru, R.; Shirsat, T.; Idicula-Thomas, S. CAMPR4: A database of natural and synthetic antimicrobial peptides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D377–D383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatun, M.S.; Hasan, M.M.; Kurata, H. PreAIP: Computational prediction of anti-inflammatory peptides by integrating multiple complementary features. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, H.M.; Westbrook, J.; Feng, Z.; Gilliland, G.; Bhat, T.N.; Weissig, H.; Shindyalov, I.N.; Bourne, P.E. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodkorb, A.; Egger, L.; Alminger, M.; Alvito, P.; Assunção, R.; Ballance, S.; Bohn, T.; Bourlieu-Lacanal, C.; Boutrou, R.; Carrière, F.; et al. INFOGEST static in vitro simulation of gastrointestinal food digestion. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 991–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arts, M.J.T.J.; Haenen, G.R.M.M.; Voss, H.P.; Bast, A. Antioxidant capacity of reaction products limits the applicability of the Trolox Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity (TEAC) assay. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2004, 42, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Ledesma, B.; Dávalos, A.; Bartolomé, B.; Amigo, L. Preparation of antioxidant enzymatic hydrolysates from α-lactalbumin and β-lactoglobulin. Identification of active peptides by HPLC-MS/MS. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 588–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvan, J.M.; Gutiérrez-Docio, A.; Moreno-Fernandez, S.; Alarcón-Cavero, T.; Prodanov, M.; Martinez-Rodriguez, A.J. Procyanidin-rich extract from grape seeds as a putative tool against Helicobacter Pylori. Foods 2020, 9, 1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franca-Oliveira, G.; Monreal Peinado, S.; Alves de Souza, S.M.; Kalume, D.E.; Ferraz de Souza, T.L.; Hernández-Ledesma, B.; Martinez-Rodriguez, A.J. Proteomic characterization of a lunasin-enriched soybean extract potentially useful in the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebel, C.P.; Ischiropoulos, H.; Bondy, S.C. Evaluation of the probe 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin as an indicator of reactive oxygen species formation and oxidative stress. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1992, 5, 227–231. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1322737/ (accessed on 2 November 2025). [CrossRef]

| Accession a | −10logP b | Average Mass (kDa) | Description c | Peptides Generated After in Silico Gastric Digestion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A0A7S1SXE6 | 362.47 | 99.05 | Tr-type G domain-containing protein | 93 |

| A0A7S1SM83 | 346.30 | 101.61 | Alpha-14 glucan phosphorylase | 105 |

| A0A7S1SNL9 | 339.13 | 84.11 | Aconitate hydratase mitochondrial | 76 |

| A0A7S1SIF9 | 317.63 | 92.59 | formate C-acetyltransferase | 90 |

| A0A7S1X996 | 313.38 | 91.33 | ACT domain-containing protein (Fragment) | 75 |

| A0A7S1SHH8 | 305.65 | 100.13 | ABC transporter domain-containing protein | 89 |

| A0A7S1X1T7 | 289.92 | 129.14 | Cation-transporting P-type ATPase N-terminal domain-containing protein | 107 |

| A0A7S1SVE5 | 284.05 | 66.20 | Alpha-14 glucan phosphorylase (Fragment) | 82 |

| A0A7S1SPX6 | 265.75 | 98.81 | Coatomer subunit gamma | 81 |

| A0A7S1T3I0 | 261.36 | 88.82 | Prolyl endopeptidase | 102 |

| A0A7S1SPT9 | 234.30 | 104.32 | carbamoyl-phosphate synthase (glutamine-hydrolyzing) | 96 |

| A0A7S1X6A5 | 231.33 | 103.28 | Cation-transporting P-type ATPase N-terminal domain-containing protein | 92 |

| A0A7S1SQY6 | 220.37 | 109.36 | Clp R domain-containing protein | 92 |

| A0A7S1SKB1 | 202.03 | 113.48 | Uncharacterized protein | 100 |

| A0A7S1T064 | 186.71 | 155.40 | magnesium chelatase | 146 |

| A0A7S1SWQ6 | 181.90 | 178.52 | SUEL-type lectin domain-containing protein | 171 |

| A0A7S1WYL3 | 171.80 | 105.99 | leucine--tRNA ligase (Fragment) | 89 |

| A0A7S1SW31 | 165.90 | 111.31 | Pyruvate phosphate dikinase AMP/ATP-binding domain-containing protein | 120 |

| A0A7S1SM91 | 140.91 | 101.38 | Glycosyl hydrolase family 13 catalytic domain-containing protein (Fragment) | 103 |

| A0A7S1X1F6 | 139.34 | 95.70 | valine--tRNA ligase | 85 |

| A0A7S1SM32 | 107.70 | 99.61 | Coatomer WD-associated region domain-containing protein (Fragment) | 89 |

| Peptide | Free Binding Energy (Kcal/mol) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keap-1 | MPO | CXCR1 | CXCR2 | VacA | CagA | |

| FAPMSRF | −4.6 | −7.5 | −6.9 | −6.5 | −1.3 | −2.2 |

| FHPKRPWI | n.d. | −8.0 | −2.3 | −6.5 | −1.2 | n.d. |

| FIPVL | −8.1 | −7.9 | −7.7 | −6.4 | −2.0 | −5.1 |

| GARCNMPKL | n.d | −6.5 | −4.5 | −5.7 | −1.1 | n.d. |

| WMGGRL | −7.3 | −7.2 | −5.5 | −6.3 | −1.6 | −5.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Majchrzak, M.; Paterson, S.; Gómez-Cortés, P.; Silvan, J.M.; Martinez-Rodriguez, A.J.; Hernández-Ledesma, B. Tetraselmis chuii as Source of Bioactive Compounds Against Helicobacter pylori: An Integrated Proteomic and Bioactivity Approach. Molecules 2025, 30, 4669. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244669

Majchrzak M, Paterson S, Gómez-Cortés P, Silvan JM, Martinez-Rodriguez AJ, Hernández-Ledesma B. Tetraselmis chuii as Source of Bioactive Compounds Against Helicobacter pylori: An Integrated Proteomic and Bioactivity Approach. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4669. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244669

Chicago/Turabian StyleMajchrzak, Marta, Samuel Paterson, Pilar Gómez-Cortés, Jose Manuel Silvan, Adolfo J. Martinez-Rodriguez, and Blanca Hernández-Ledesma. 2025. "Tetraselmis chuii as Source of Bioactive Compounds Against Helicobacter pylori: An Integrated Proteomic and Bioactivity Approach" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4669. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244669

APA StyleMajchrzak, M., Paterson, S., Gómez-Cortés, P., Silvan, J. M., Martinez-Rodriguez, A. J., & Hernández-Ledesma, B. (2025). Tetraselmis chuii as Source of Bioactive Compounds Against Helicobacter pylori: An Integrated Proteomic and Bioactivity Approach. Molecules, 30(24), 4669. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244669