Momordica charantia L. (Cucurbitaceae) Leaf Extract from Phytochemical Characterization and Toxicity Evaluation to Modulation of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines and MAPK/NFκB Pathways

Abstract

1. Introduction

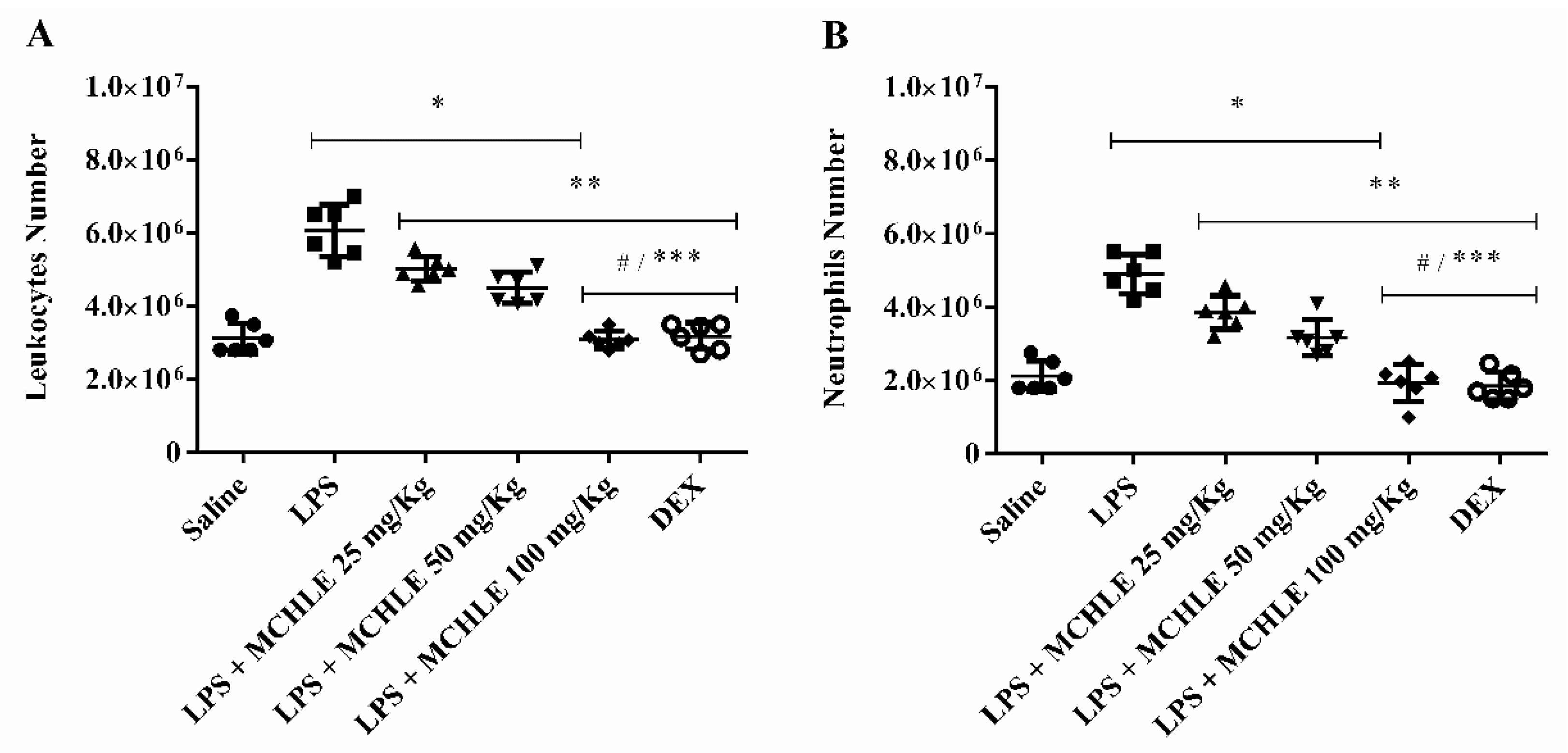

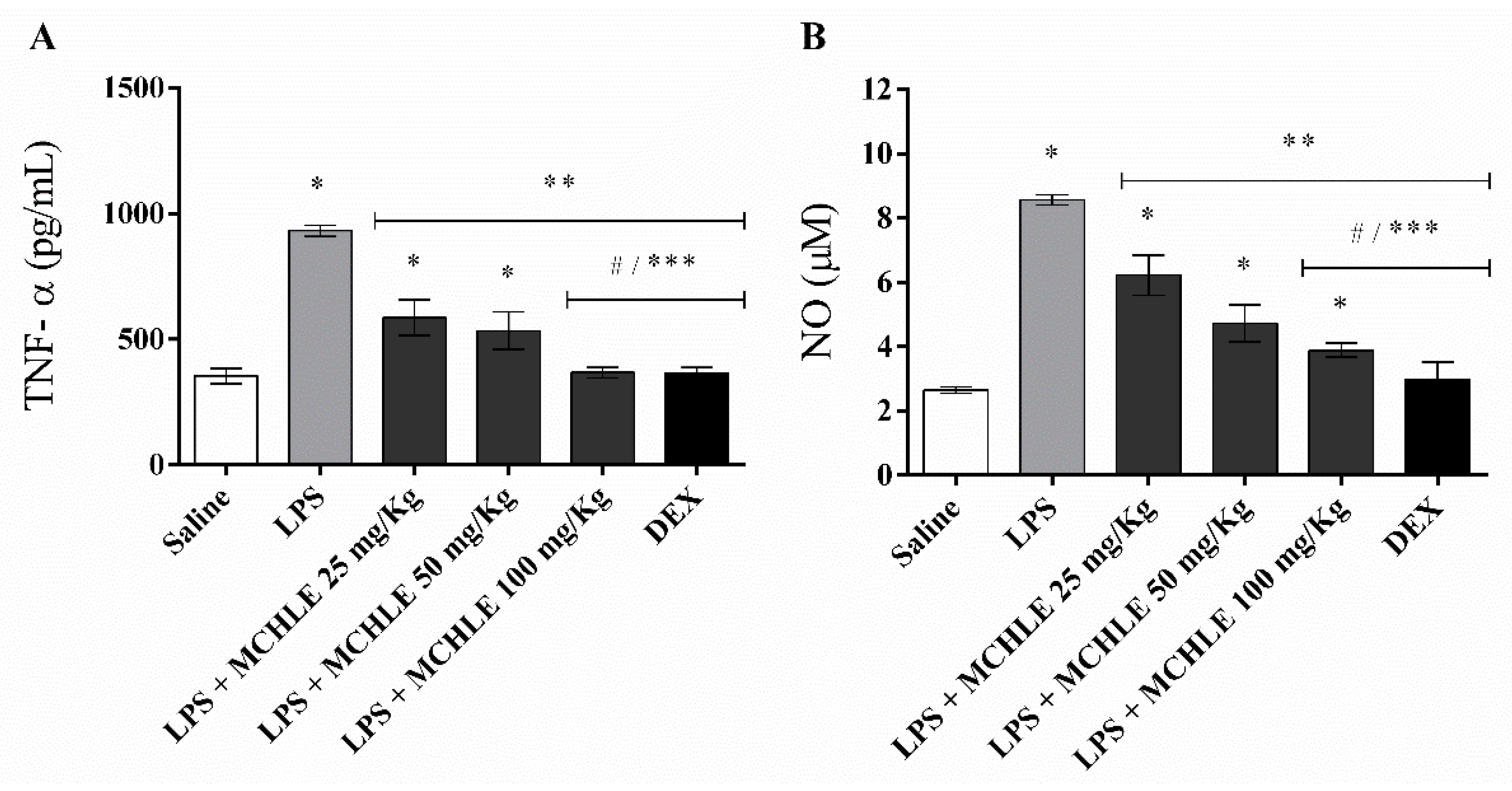

2. Results

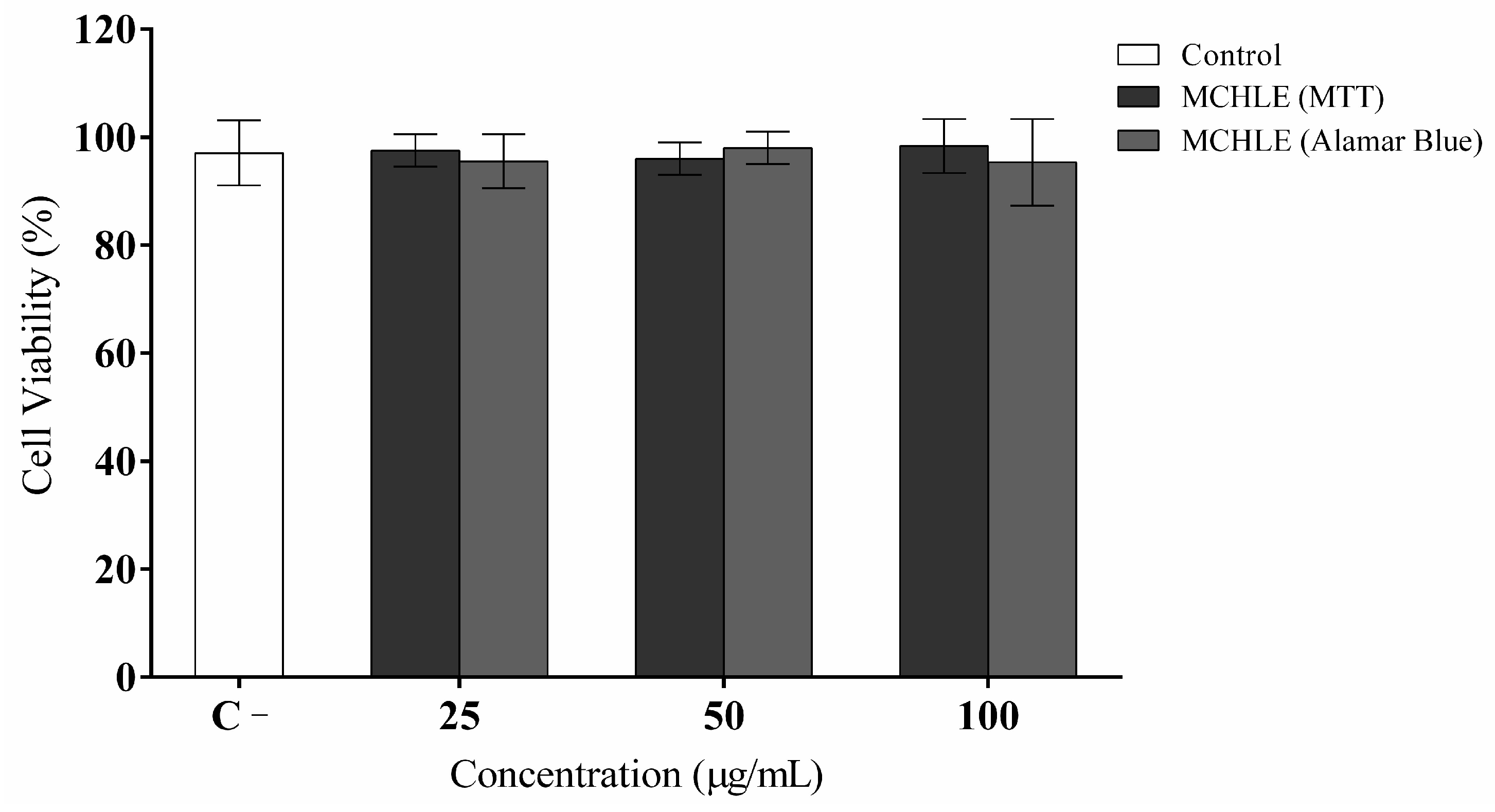

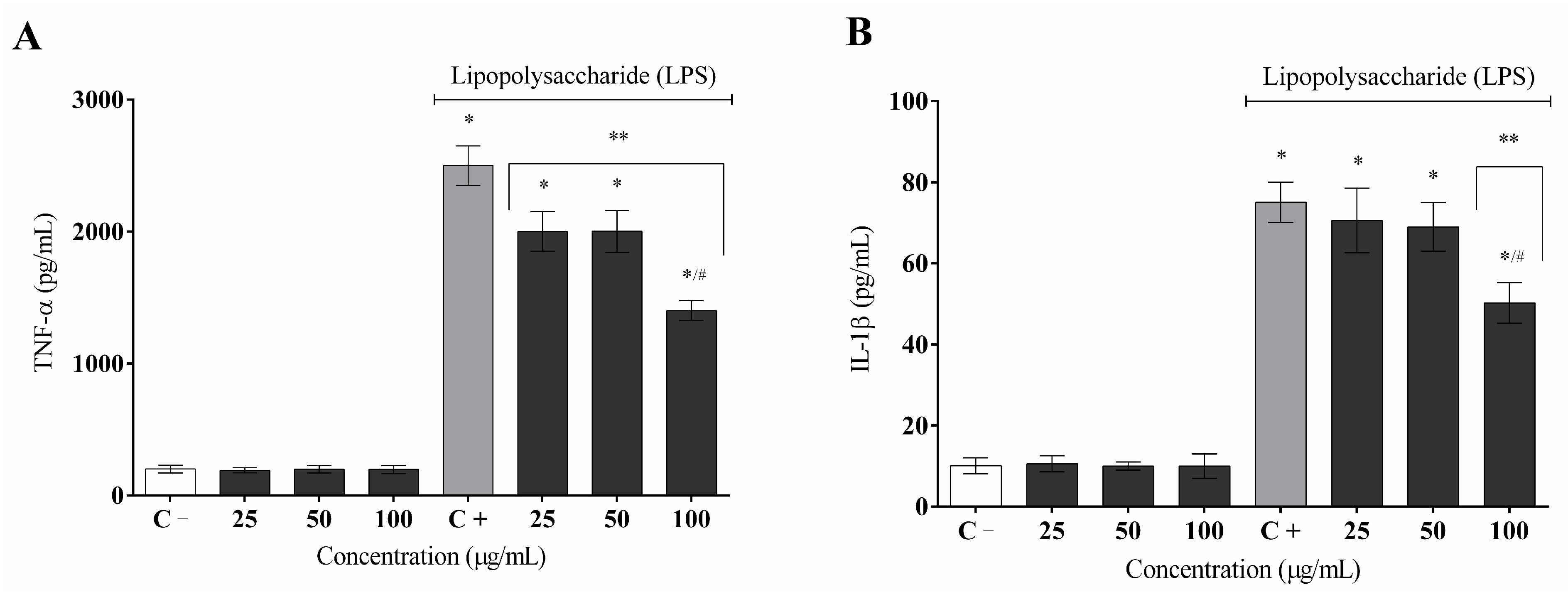

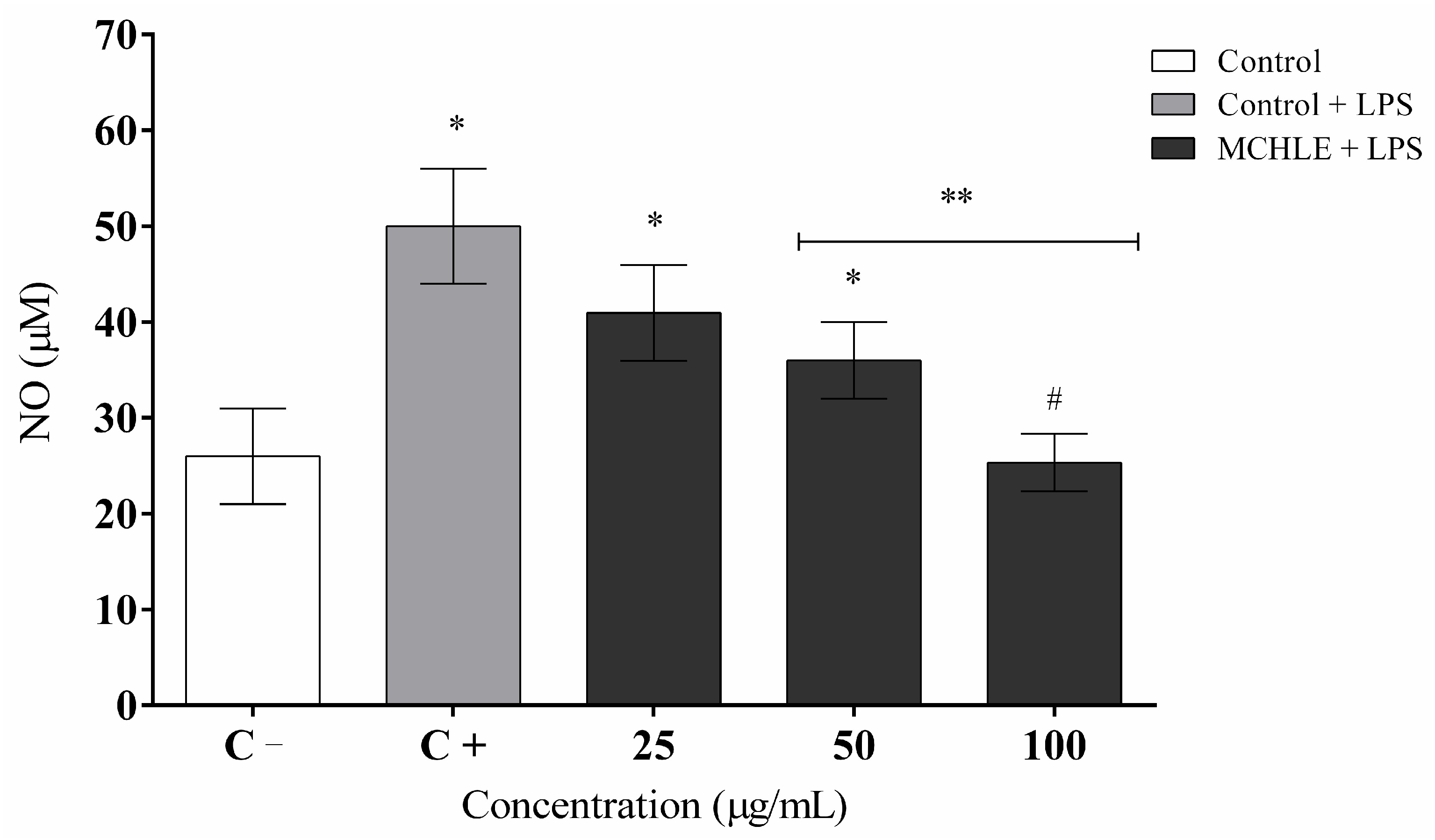

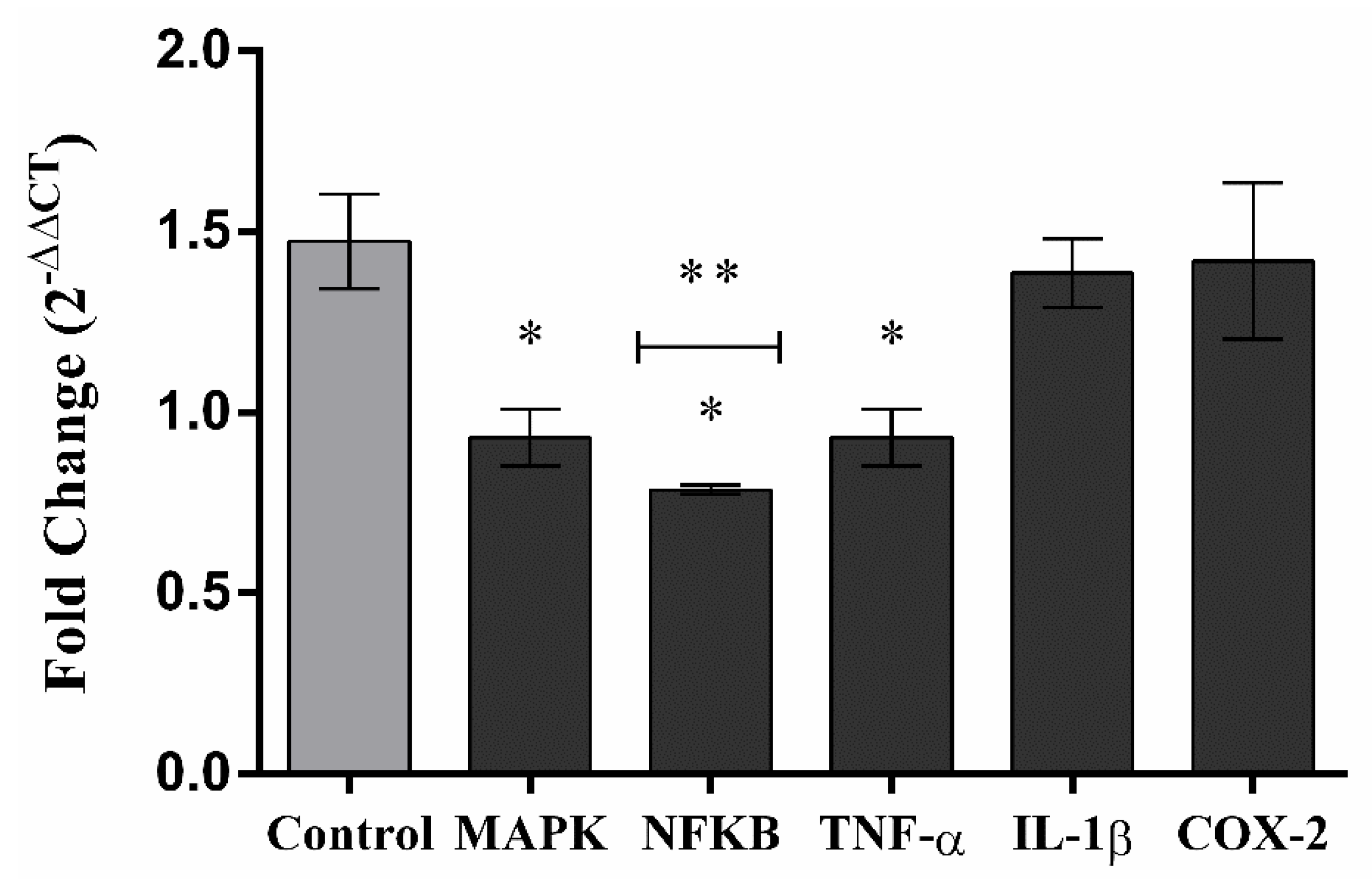

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material and Extract Preparation

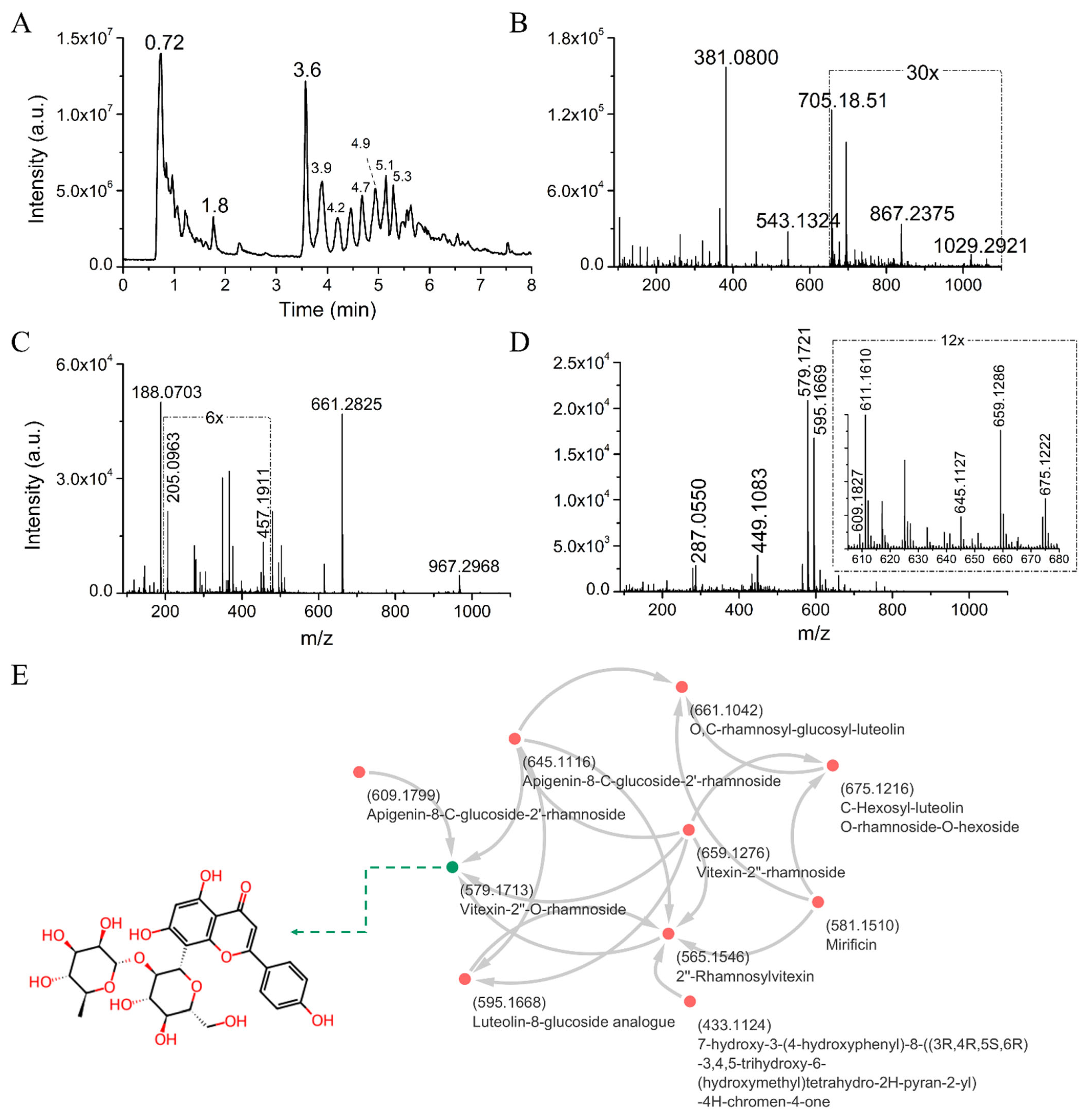

4.2. Phytochemical Analysis by Ultrafast Liquid Chromatography Coupled to Mass Spectrometry (LC–MS/MS)

4.3. Cell Culture and Animals

4.4. Cell Viability and Cytotoxicity Assays

4.5. Acute Toxicity

4.6. Repeated Dose Oral Toxicity 28 Days

4.7. Evaluation of Biochemical Parameters and Preparation of Hepatic Homogenate

4.8. Oxidative Stress Analyses

4.9. Leukocyte Migration into Peritoneal Cavity and Cytokine Dosage

4.10. Cytokine Measurement (TNF-α and IL1-β)

4.11. Measurement of Nitric Oxide (NO) Production

4.12. Gene Expression Analysis

4.12.1. RNA Extraction and cDNA Production

4.12.2. Inflammation-Related Gene Expression Quantification

4.13. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chavda, V.P.; Feechan, J.; Apostolopoulos, V. Inflammation: The Cause of All Diseases. Cells 2024, 13, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soliman, A.M.; Barreda, D.R. Acute Inflammation in Tissue Healing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Lan, C.; Benlagha, K.; Camara, N.O.S.; Miller, H.; Kubo, M.; Heegaard, S.; Lee, P.; Yang, L.; Forsman, H.; et al. The interaction of innate immune and adaptive immune system. Med. Comm. 2023, 5, e714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Saeed, A.F.U.H.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, Q.; Xu, H.; Xiao, G.G.; Rao, L.; Duo, Y. Macrophages in immunoregulation and therapeutics. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Lin, X. Challenges and advances in the management of inflammation in atherosclerosis. J. Adv. Res. 2025, 71, 317–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindu, S.; Mazumder, S.; Bandyopadhyay, U. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and organ damage: A current perspective. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020, 180, 114147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, M.R.; Goemaere, S.; Bergmann, P.; Body, J.J.; Bruyère, O.; Cavalier, E.; Rozenberg, S.; Lapauw, B.; Gielen, E. Prevention and Treatment of Glucocorticoid-Induced Osteoporosis in Adults: Consensus Recommendations From the Belgian Bone Club. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 908727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, A. Recent Data about the Use of Corticosteroids in Sepsis—Review of Recent Literature. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luz, J.R.D.; Barbosa, E.A.; Nascimento, T.E.S.; Rezende, A.A.; Ururahy, M.A.G.; Brito, A.S.; Araujo-Silva, G.; López, J.A.; Almeida, M.G. Chemical Characterization of Flowers and Leaf Extracts Obtained from Turnera subulata and Their Immunomodulatory Effect on LPS-Activated RAW 264.7 Macrophages. Molecules 2022, 27, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, M.; Khalid, R.; Afzal, M.; Anjum, F.; Fatima, H.; Zia, S.; Rasool, G.; Egbuna, C.; Metwa, A.G.; Uche, C.Z.; et al. Phytobioactive compounds as therapeutic agents for human diseases: A review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 2500–2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudrapal, M.; Rakshit, G.; Singh, R.P.; Garse, S.; Khan, J.; Chakraborty, S. Dietary Polyphenols: Review on Chemistry/Sources, Bioavailability/Metabolism, Antioxidant Effects, and Their Role in Disease Management. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behl, T.; Kumar, K.; Brisc, C.; Rus, M.; Nistor-Cseppento, D.C.; Bustea, C.; Aron, R.A.C.; Pantis, C.; Zengin, G.; Sehgal, A.; et al. Exploring the multifocal role of phytochemicals as immunomodulators. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 133, 110959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakadate, K.; Ito, N.; Kawakami, K.; Yamazaki, N. Anti-Inflammatory Actions of Plant-Derived Compounds and Prevention of Chronic Diseases: From Molecular Mechanisms to Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Li, Z.; Zeng, T.; Zhan, J.; Wang, S.; Ho, C.; Li, S. Bioactives of Momordica charantia as Potential Anti-Diabetic/Hypoglycemic Agents. Molecules 2022, 27, 2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolotti, M.; Mercatelli, D.; Polito, L. Momordica charantia, a Nutraceutical Approach for Inflammatory Related Diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayathry, K.S.; John, J.A. A comprehensive review on bitter gourd (Momordica charantia L.) as a gold mine of functional bioactive components for therapeutic foods. Food Prod. Process. Nutr. 2022, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bara, L.V.; Budau, R.; Apahidean, A.I.; Bara, C.M.; Iancu, C.V.; Jude, E.T.; Cheregi, G.R.; Timar, A.V.; Bei, M.F.; Osvat, I.M.; et al. Momordica charantia L.: Functional Health Benefits and Uses in the Food Industry. Plants 2025, 14, 2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batran, S.A.E.S.E.; El-Gengaihi, S.E.; El Shabrawy, O.A. Some toxicological studies of Momordica charantia L. on albino rats in normal and alloxan diabetic rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006, 108, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Dan, L.; Su, L.; Wei, X. Tissue-specific partitioning of flavonoids and phenolic acids coordinates bioactivities in Ormosia henryi Prain. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, B.; Sharma, H.; Meena, A.K.; Bharthi, V. Balancing tradition and conservation: Exploring plant part substitution in traditional medicine. J. Integr. Med. 2025, 23, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, T.E.S.; López, J.A.; Barbosa, E.A.; Ururahy, M.A.G.; Brito, A.S.; Araujo-Silva, G.; Luz, J.R.D.; Almeida, M.G. Mass Spectrometric Identification of Licania rigida Benth Leaf Extracts and Evaluation of Their Therapeutic Effects on Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Inflammatory Response. Molecules 2022, 27, 6291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, A.; Hu, P.; Yang, M.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, W.; Zheng, Q. Natural Products as Anticancer Agents: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Molecules 2022, 27, 8367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R.; Miao, L.; Zhang, H.; Tan, L.; Zhao, Y.; Tu, Y.; Prieto, M.A.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Chen, L.; He, C.; et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of flavonols via inhibiting MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways in RAW264.7 macrophages. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2022, 5, 1176–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Wong, W.F.; Dong, J.; Cheng, K.K. Momordica charantia Suppresses Inflammation and Glycolysis in Lipopolysaccharide-Activated RAW264.7 Macrophages. Molecules 2020, 25, 3783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumbhar, S.; Musale, M.; Jamsa, A. Bilirubin metabolism: Delving into the cellular and molecular mechanisms to predict complications. Egypt. J. Intern. Med. 2024, 36, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Mejía, M.M.; Castillo-Castañeda, S.M.; Pal, S.C.; Qi, X.; Méndez-Sánchez, N. The Multifaceted Role of Bilirubin in Liver Disease: A Literature Review. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2024, 12, 939–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, C.L.; Fang, S.C.; Liu, C.W.; Chen, Y.F. Inhibitory effects of new varieties of bitter melon on lipopolysaccharide-stimulated inflammatory response in RAW 264.7 cells. J. Func. Foods 2013, 5, 1829–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Guo, C.; Yang, X.; Mi, W.; Hua, C.; Tang, C.; Wang, H. Effects of natural products on macrophage immunometabolism: A new frontier in the treatment of metabolic diseases. Pharmacol. Res. 2025, 213, 107634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suksungworn, R.; Andrade, P.B.; Oliveira, A.P.; Valentão, P.; Duangsrisai, S.; Gomes, N.G.M. Inhibition of Proinflammatory Enzymes and Attenuation of IL-6 in LPS-Challenged RAW 264.7 Macrophages Substantiates the Ethnomedicinal Use of the Herbal Drug Homalium bhamoense Cubitt & W.W.Sm. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freemerman, A.J.; Johnson, A.R.; Sacks, G.N.; Milner, J.J.; Kirk, E.L.; Troester, M.A.; Macintyre, A.N.; Goraksha-Hicks, P.; Rathmell, J.C.; Makowski, L. Metabolic Reprogramming of Macrophages: Glucose Transporter 1 (Glut1)-Mediated Glucose Metabolism Drives a Proinflammatory Phenotype. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 7884–7896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, R.; Gu, H.; Zhang, E.; Qu, J.; Cao, W.; Huang, X.; Yan, H.; He, J.; Cai, Z. Metabolic reprogramming in macrophage responses. Biomark. Res. 2021, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofuegbe, S.O.; Oyagbemi, A.A.; Omobowale, T.O.; Adedapo, A.D.; Ayodele, A.E.; Yakubu, M.A.; Oguntibeju, O.O.; Adedapo, A.A. Methanol leaf extract of Momordica charantia protects alloxan-induced hepatopathy through modulation of caspase-9 and interleukin-1β signaling pathways in rats. Vet. World 2020, 13, 1528–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özbeyli, D.; Şen, A.; Çevik, O.; Erdoğan, O.; Tuğçe, O.; Kaya, Ç.; Ede, S.; Şener, G. The Protective Effects of Momordica Charantia Fruit Extract in Methotrexate Induced Liver Damage in Rats. Cyprus J. Med. Sci. 2022, 7, 787–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonan, P.; Ariyabukalakorn, V.; Yoysungnoen, B.; Singsai, K.; Praphasawat, R.; Sangkham, S.; Jantarach, N.; Riyamongkhol, P.; Somparn, N.; Munkong, N. Hepatoprotective Effects of Gac (Momordica cochinchinensis) Aril Extract in Acetaminophen-Induced Liver Injury: Modulation of Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Glucose Metabolism. J. Exp. Pharmacol. 2025, 17, 527–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, G.; Cordova, F.; Koning, T.; Sarmiento, J.; Boric, M.P.; Birukov, K.; Cancino, J.; Varas-Godoy, M.; Soza, A.; Alves, N.G.; et al. TNF-a-activated eNOS signaling increases leukocyte adhesion through the Snitrosylation pathway. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2021, 321, 1083–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, T.; Uche, N.; Juric, M.; Zielonka, J.; Bai, X. Regulation of immunomodulatory networks by Nrf2-activation in immune cells: Redox control and therapeutic potential in inflammatory diseases. Redox Biol. 2024, 70, 103077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunstein, I.; Motohashi, H.; Dallenga, T.; Schaible, U.E.; Benhar, M. Redox signaling in innate immunity and inflammation: Focus on macrophages and neutrophils. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2025, 237, 427–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.H.; Yan, Z.Q.; Brauner, A.; Tullus, K. Activation of macrophage nuclear factor-κB and induct ion of inducible nitric oxide synthase by LPS. Respir. Res. 2002, 3, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; Zou, J.; Chen, J.; Zhong, X.; Kang, R.; Tang, D. Pattern recognition receptors: Function, regulation and therapeutic potential. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.M.; Park, J.E.; Park, J.S.; Leem, Y.H.; Kim, D.Y.; Hyun, J.W.; Kim, H.S. Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant mechanisms of coniferaldehyde in lipopolysaccharide-induced neuroinflammation: Involvement of AMPK/Nrf2 and TAK1/MAPK/NF-κB signaling pathways. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 979, 176850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luz, J.R.D.; Nascimento, T.E.S.; Morais, L.V.F.; Cruz, A.K.M.; Rezende, A.A.; Brandão-Neto, J.; Ururahy, M.A.G.; Luchessi, A.D.; López, J.A.; Rocha, H.A.O.; et al. Thrombin Inhibition: Preliminary Assessment of the Anticoagulant Potential of Turnera subulata (Passifloraceae). J. Med. Food 2019, 22, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ANVISA. National health surveillance agency: Ministry of health resolution—RE n° 90/2004. In Standards for Toxicological Studies of Herbal Products; Official Gazette of the Federative Republic of Brazil, Executive Branch: Brasília, Brazil, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals: Acute and Toxicity Acute Toxic Class Method; OECD Guideline 423; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Batista, D.; Luz, J.R.D.; Nascimento, T.E.S.; Senes-Lopes, T.F.; Galdino, O.A.; Silva, S.V.; Ferreira, M.P.; Azevedo, M.A.S.; Brandão-Neto, J.; Araujo-Silva, G.; et al. Licania rigida leaf extract: Protective effect on oxidative stress, associated with cytotoxic, mutagenic and preclinical aspects. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 2022, 85, 276–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals: Repeated Dose 90-Day Oral Toxicity Study in Rodents; OECD Guideline 407; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yagi, K. Assay for serum lipid peroxide level by TBA reaction. In Lipid Peroxides in Biology and Medicine; Yagi, K., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1982; pp. 223–242. [Google Scholar]

- Beutler, E.; Duron, O.; Kelly, B.M. Improved method for the determination of blood glutathione. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1963, 61, 882–888. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Phytocomponents Matched with GNPS Database | Cosine | Mass-Diff | Mass | Molecular Formula | Adduct | RT (min) | Classification | Shared Peaks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trigonelline | 0.83 | 0.000 | 138.055 | C7H7NO2 | [M+H]+ | 0.7 | Alkaloid | 5 |

| Polysaccharide | MA | 0.001 | 867.2413 | C30H52O26 | [M+K]+ | 0.8 | Polysaccharide | MA |

| DL-Octopamine | 0.95 | 0.000 | 136.076 | C8H11NO2 | [M+H]+ | 1.0 | Biogenic amine | 5 |

| L-Tyrosine * | 0.94 | 0.001 | 165.054 | C9H8O3 | [M+H]+ | 1.0 | Amino acid | 5 |

| L-(+)-norleucine | 0.98 | 0.001 | 132.102 | C6H13NO2 | [M+H]+ | 1.0 | Amino acid | 6 |

| Ciclo(His-Pro) | MA | 0.001 | 235.1182 | C11H14N4O2 | [M+H]+ | 1.1 | Ciclic dipeptide | MA |

| N-Fructosyl tyrosine | 0.78 | 0.001 | 344.133 | C15H21NO8 | [M+H]+ | 1.1 | Glycated amino acid | 10 |

| Phenylalanine * | 0.96 | 0.000 | 166.086 | C9H11NO2 | [M+H]+ | 1.2 | Amino acid | 5 |

| Fru-Gly-Leu/Ile | 0.73 | 0.001 | 351.177 | C14H26N2O8 | [M+H]+ | 2.1 | Dipeptide | 11 |

| Deoxycarnitine | 0.96 | 0.057 | 146.06 | C7H15NO2 | [M+H]+ | 3.6 | Carnitine derivative | 5 |

| L-Tryptophan * | 0.97 | 0.000 | 188.07 | C11H9N1O2 | [M−NH3+H]+ | 3.6 | Amino acid | 7 |

| Adenosine, 5_-S-methyl-5_-thio- | 0.93 | 0.000 | 298.097 | C11H15N5O3S | [M+H]+ | 3.9 | Purine nucleos(t)ides | 11 |

| Ferulate/isoferulate | 0.89 | 0.000 | 177.054 | C10H8O3 | [M+H]+ | 4.2 | Phenolic acid | 7 |

| O,C-rhamnosyl-glucosyl-luteolin | 0.75 | 66.104 | 661.104 | NA | [M+H]+ | 4.5 | Flavones | 9 |

| Vitexin-2″-rhamnoside | 0.88 | 79.957 | 659.128 | C27H30O14 | [M+H]+ | 4.6 | Flavones | 11 |

| Riboflavin | 0.83 | 0.000 | 377.146 | C17H20N4O6 | [M+H]+ | 4.7 | Pteridine alkaloids | 12 |

| Apigenin-8-C-glucoside-2′-rhamnoside | 0.83 | 65.941 | 645.112 | C27H30O14 | [M+H]+ | 4.7 | Flavones | 12 |

| C-Hexosyl-luteolin O-rhamnoside-O-hexoside | 0.74 | 81.878 | 675.122 | NA | [M+H]+ | 4.7 | Flavones | 8 |

| Mirificin | 0.78 | 31.991 | 581.151 | C26H28O13 | [M+H]+ | 4.9 | Isoflavone glycoside | 9 |

| 7-O-beta-glucopyranosyl-4′-hydroxy-5-methoxyisoflavone | 0.91 | 0.001 | 447.13 | C22H22O10 | [M+H]+ | 5.0 | Isoflavone glycoside | 5 |

| Diprotin A | 0.76 | 0.000 | 342.2386 | C17H31N3O4 | [M+H]+ | 5.1 | Dipeptide | MA |

| Vitexin-2″-O-rhamnoside | 0.96 | 0.001 | 579.171 | C27H30O14 | [M+H]+ | 5.1 | Flavones | 15 |

| 2″-Rhamnosylvitexin | 0.93 | 14.015 | 565.155 | C27H30O14 | [M+H]+ | 5.2 | Flavones | 10 |

| 7-hydroxy-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-8-((3R,4R,5S,6R)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)-4H-chromen-4-one | 0.73 | 15.992 | 433.113 | C21H20O9 | [M+H]+ | 5.2 | Flavones | 8 |

| Kaempferol | 0.80 | 0.000 | 287.055 | C15H10O6 | [M+H]+ | 5.3 | Flavonols | 11 |

| Apigenin-8-C-glucoside-2′-rhamnoside | 0.79 | 30.009 | 609.18 | C27H30O14 | [M+H]+ | 5.3 | Flavones | 9 |

| Epicatechin gallate | 0.91 | 0.024 | 465.104 | C22H18O10 | [M+Na] | 5.5 | Flavones | 3 |

| Luteolin 4′-O-glucoside | 0.97 | 0.001 | 449.109 | C21H20O11 | [M+H]+ | 5.7 | Flavones | 8 |

| Petunidin-3-O-B-glucopyranoside | 0.89 | 0.001 | 479.119 | C22H22O12 | [M+H]+ | 5.8 | Anthocyanin glycosede | 5 |

| Kaempferol | 0.80 | 0.000 | 287.055 | C15H10O6 | [M+H]+ | 6.7 | Flavonols | 11 |

| Aspergillusenes A | 0.71 | 0.001 | 235.169 | C15H22O2 | [M+H]+ | 8.8 | Sesquiterpenoid | 11 |

| Luteolin-8-glucoside analog | 0.79 | 15.990 | 595.167 | C27H30O15 | [M+H]+ | 4.9/5.2 | Flavones | 16 |

| Biochemical Parameters | Acute Toxicity | Repeated Dose Toxicity | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | ||||||||

| Control | 2000 mg/kg | Control | 100 mg/kg | 200 mg/kg | 400 mg/kg | Control | 100 mg/kg | 200 mg/kg | 400 mg/kg | |

| Gluc (mg/dL) | 152 ± 8.91 | 73 ± 1.1 * | 124.34 ± 5.32 | 122.05 ± 12.32 | 100.09 ± 15.02 *,# | 40.94 ± 1.32 *,# | 121.73 ± 12.09 | 100.08 ± 2.13 # | 85.43 ± 1.32 *,# | 60.02 ± 1.35 *,# |

| Trig (mg/dL) | 78 ± 1.65 | 35.1 ± 3.35 | 21.80 ± 1.80 | 23.99 ± 2.77 | 24.23 ± 1.09 | 24.98 ± 1.23 | 40.21 ± 1.12 | 41.12 ± 1.34 | 45.01 ± 3.76 | 43.23 ± 1.63 |

| Chol (mg/dL) | 58.2 ± 5.01 | 29 ± 0.97 * | 63.63 ± 4.32 | 61.63 ± 4.32 | 60.01 ± 1.22 | 32.76 ± 2.98 * | 50.21 ± 2.42 | 50.43 ± 1.02 | 53.02 ± 1.95 | 24.93 ± 1.88 * |

| ALT (U/L) | 95 ± 4.44 | 93 ± 1.60 | 86.34 ± 5.64 | 88.32 ± 15.06 | 86.92 ± 3.43 | 84.65 ± 9.08 | 85.23 ± 1.54 | 84.65 ± 1.01 | 84.52 ± 2.98 | 83.12 ± 5.01 |

| AST (U/L) | 234 ± 21.3 | 215 ± 18.5 | 215.98 ± 1.39 | 214.65 ± 9.38 | 210.23 ± 5.39 | 212 ± 2.98 | 200.23 ± 13.38 | 201.62 ± 5.35 | 200.98 ± 1.54 | 203.76 ± 3.79 |

| γ-GT (U/L) | 14 ± 0.23 | 13.3 ± 0.01 | 11.98 ± 0.54 | 10.87 ± 0.05 | 10.87 ± 0.50 | 11.77 ± 0.02 | 9.89 ± 0.32 | 9.88 ± 1.51 | 9.32 ± 0.02 | 9.32 ± 0.32 |

| TB (mg/dL) | 0.33 ± 0.01 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 0.46 ± 0.02 | 0.25 ± 0.05 | 0.34 ± 0.01 | 0.55 ± 0.25 | 0.35 ± 0.15 | 0.35 ± 0.25 | 0.30 ± 0.02 | 0.32 ± 0.05 |

| DB (mg/dL) | 0.103 ± 0.04 | 0.104 ± 0.09 | 1.34 ± 0.01 | 1.32 ± 0.01 | 1.38 ± 0.01 | 1.18 ± 0.01 | 1.43 ± 0.05 | 1.45 ± 0.01 | 1.35 ± 0.52 | 1.34 ± 0.08 |

| IB (mg/dL) | 0.25 ± 0.01 | 0.21 ± 0.10 | 0.20 ± 0.001 | 0.17 ± 0.001 | 0.14 ± 0.005 | 0.17 ± 0.001 | 0.18 ± 0.002 | 0.10 ± 0.001 | 0.05 ± 0.001 | 0.02 ± 0.001 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 50.5 ± 1.7 | 43.3 ± 1.04 | 34.23 ± 1.21 | 33.84 ± 2.61 | 31.77 ± 1.81 | 32.54 ± 2.09 | 32.23 ± 0.01 | 32.87 ± 1.61 | 31.77 ± 1.81 | 31.54 ± 1.02 |

| Uric acid (mg/dL) | 1.14 ± 0.45 | 1.01 ± 0.01 | 1.10 ± 0.01 | 1.15 ± 0.04 | 1.15 ± 0.05 | 1.01 ± 0.232 | 1.6 ± 0.05 | 1.15 ± 0.06 | 1.23 ± 0.41 | 1.48 ± 0.99 |

| Organ (g) | Acute Toxicity | Repeated Dose Toxicity | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | ||||||||

| Control | 2000 mg/kg | Control | 100 mg/kg | 200 mg/kg | 400 mg/kg | Control | 100 mg/kg | 200 mg/kg | 400 mg/kg | |

| Kidney (R) | 0.30 ± 0.01 | 0.3 ± 0.03 | 0.45 ± 0.04 | 0.54 ± 0.12 | 0.52 ± 0.14 | 0.55 ± 0.90 | 0.38 ± 0.17 | 0.45 ± 0.15 | 0.39 ± 0.16 | 0.40 ± 0.01 |

| Kidney (L) | 0.31 ± 0.03 | 0.31 ± 0.1 | 0.36 ± 0.09 | 0.40 ± 0.10 | 0.65 ± 0.14 | 0.65 ± 0.54 | 0.35 ± 0.08 | 0.44 ± 0.05 | 0.38 ± 0.10 | 0.30 ± 0.00 |

| Liver | 4.21 ± 0.5 | 3.96 ± 0.03 | 4.54 ± 0.08 | 4.98 ± 0.12 | 4.35 ± 0.15 | 4.99 ± 0.12 | 4.54 ± 0.05 | 4.00 ± 0.09 | 4.00 ± 0.38 | 4.40 ± 0.02 |

| Spleen | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.34 ± 0.04 | 0.54 ± 0.03 | 0.43 ± 0.03 | 0.47 ± 0.04 | 0.26 ± 0.05 | 0.28 ± 0.01 | 0.25 ± 0.08 | 0.20 ± 0.09 |

| Heart | 0.21 ± 0.01 | 0.20 ± 0.02 | 0.21 ± 0.02 | 0.34 ± 0.05 | 0.45 ± 0.09 | 0.25 ± 0.04 | 0.26 ± 0.17 | 0.24 ± 0.07 | 0.26 ± 0.08 | 0.30 ± 0.05 |

| Lung | 0.42 ± 0.01 | 0.5 ± 0.01 | 0.41 ± 0.04 | 0.48 ± 0.05 | 0.43 ± 0.04 | 0.39 ± 0.03 | 0.42 ± 0.03 | 0.48 ± 0.03 | 0.40 ± 0.04 | 0.60 ± 0.05 |

| Stomach | 0.45 ± 0.14 | 0.6 ± 0.21 | 0.54 ± 0.02 | 0.66 ± 0.08 | 0.55 ± 0.05 | 0.52 ± 0.03 | 0.48 ± 0.05 | 0.42 ± 0.01 | 0.39 ± 0.02 | 0.40 ± 0.03 |

| Oxidative Stress Parameters | Acute Toxicity | Repeated Dose Toxicity | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | ||||||||

| Control | 2000 mg/kg | Control | 100 mg/kg | 200 mg/kg | 400 mg/kg | Control | 100 mg/kg | 200 mg/kg | 400 mg/kg | |

| MDA (μmol/L) | 78.14 ± 1.12 | 43.44 ± 1.55 | 80.23 ± 3.43 | 80.43 ± 1.57 | 40.84 ± 1.23 * | 30.43 ± 1.43 * | 74.16 ± 1.02 | 73.51 ± 1.78 * | 42.10 ± 1.24 * | 29.19 ± 1.36 * |

| GSH (μmol/L) | 5.48 ± 0.05 | 4.93 ± 0.06 | 5.65 ± 1.32 | 5.73 ± 0.04 | 4.98 ± 0.01 | 5.46 ± 0.03 | 5.51 ± 0.01 | 5.54 ± 0.07 | 5.93 ± 0.08 | 2469 ± 0.08 |

| SOD (IU/mg protein) | U.R. | U.R. | 68.34 ± 1.43 | 65.56 ± 0.43 | 65.23 ± 1.43 | 88.35 ± 1.23 * | 68.30 ± 0.04 | 69.34 ± 0.21 | 66.32 ± 1.39 | 85.50 ± 1.58 * |

| GPx (IU/mg protein) | U.R. | U.R. | 5.74 ± 0.05 | 7.58 ± 0.08 * | 8.43 ± 0.01 * | 10.98 ± 0.03 * | 5.91 ± 0.06 | 5.19 ± 0.07 | 7.56 ± 0.02 * | 11.01 ± 0.04 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oliveira, M.L.d.A.; Sousa, R.M.d.; Barbosa, E.A.; Galdino, O.A.; Dantas, D.L.A.; Alves, I.R.; Sousa Borges, R.; Castelo Branco, N.C.d.M.; Nascimento Rodrigues, A.S.d.; de Souza, G.C.; et al. Momordica charantia L. (Cucurbitaceae) Leaf Extract from Phytochemical Characterization and Toxicity Evaluation to Modulation of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines and MAPK/NFκB Pathways. Molecules 2025, 30, 4335. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30224335

Oliveira MLdA, Sousa RMd, Barbosa EA, Galdino OA, Dantas DLA, Alves IR, Sousa Borges R, Castelo Branco NCdM, Nascimento Rodrigues ASd, de Souza GC, et al. Momordica charantia L. (Cucurbitaceae) Leaf Extract from Phytochemical Characterization and Toxicity Evaluation to Modulation of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines and MAPK/NFκB Pathways. Molecules. 2025; 30(22):4335. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30224335

Chicago/Turabian StyleOliveira, Maria Lúcia de Azevedo, Rubiamara Mauricio de Sousa, Eder Alves Barbosa, Ony Araújo Galdino, Duanny Lorena Aires Dantas, Ingrid Reale Alves, Raphaelle Sousa Borges, Nayara Costa de Melo Castelo Branco, Artemis Socorro do Nascimento Rodrigues, Gisele Custódio de Souza, and et al. 2025. "Momordica charantia L. (Cucurbitaceae) Leaf Extract from Phytochemical Characterization and Toxicity Evaluation to Modulation of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines and MAPK/NFκB Pathways" Molecules 30, no. 22: 4335. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30224335

APA StyleOliveira, M. L. d. A., Sousa, R. M. d., Barbosa, E. A., Galdino, O. A., Dantas, D. L. A., Alves, I. R., Sousa Borges, R., Castelo Branco, N. C. d. M., Nascimento Rodrigues, A. S. d., de Souza, G. C., Silva, S. V. e., Araujo-Silva, G., Luz, J. R. D. d., & Almeida, M. d. G. (2025). Momordica charantia L. (Cucurbitaceae) Leaf Extract from Phytochemical Characterization and Toxicity Evaluation to Modulation of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines and MAPK/NFκB Pathways. Molecules, 30(22), 4335. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30224335