New Dimethylpyridine-3-Carboxamide Derivatives as MMP-13 Inhibitors with Anticancer Activity

Abstract

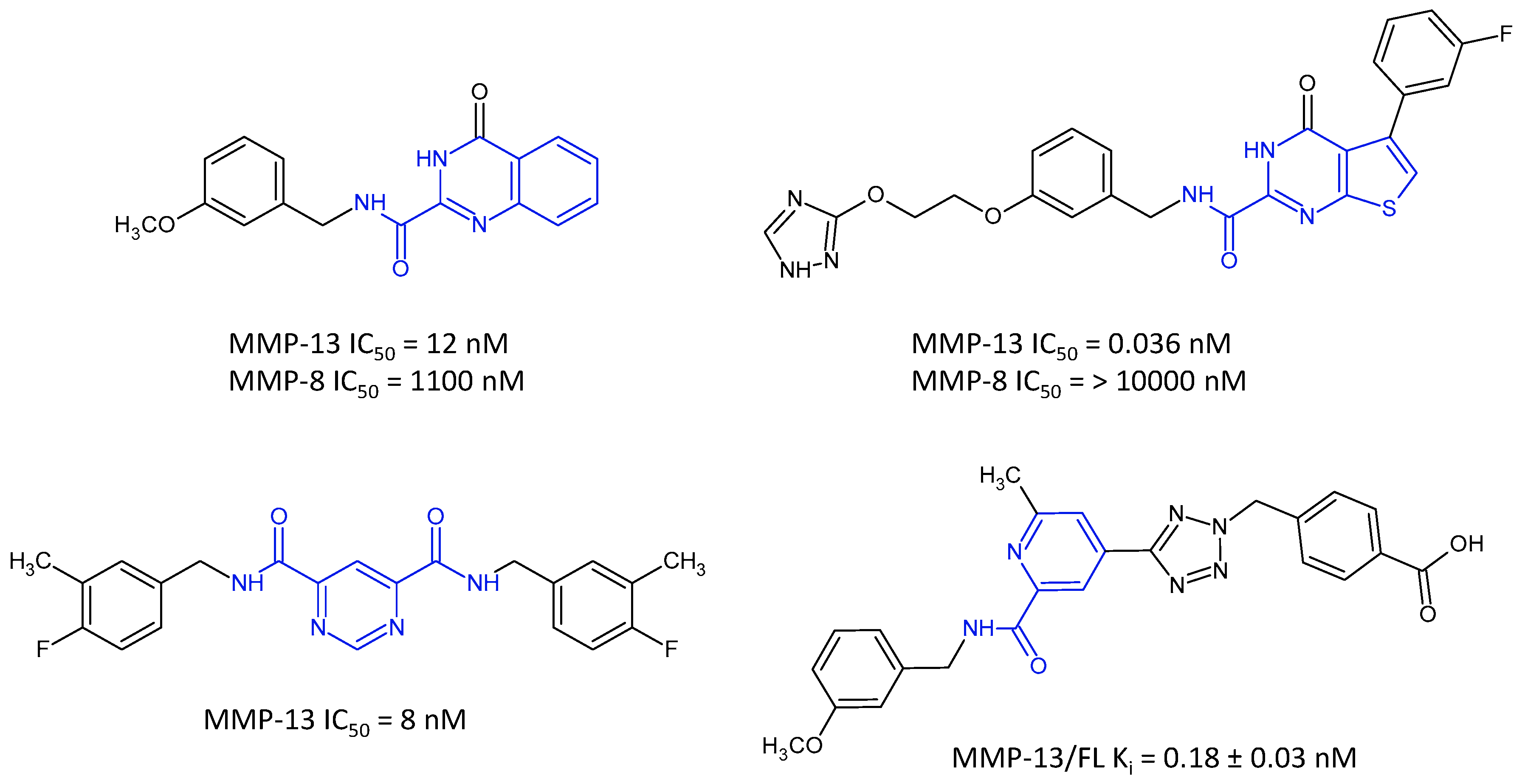

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

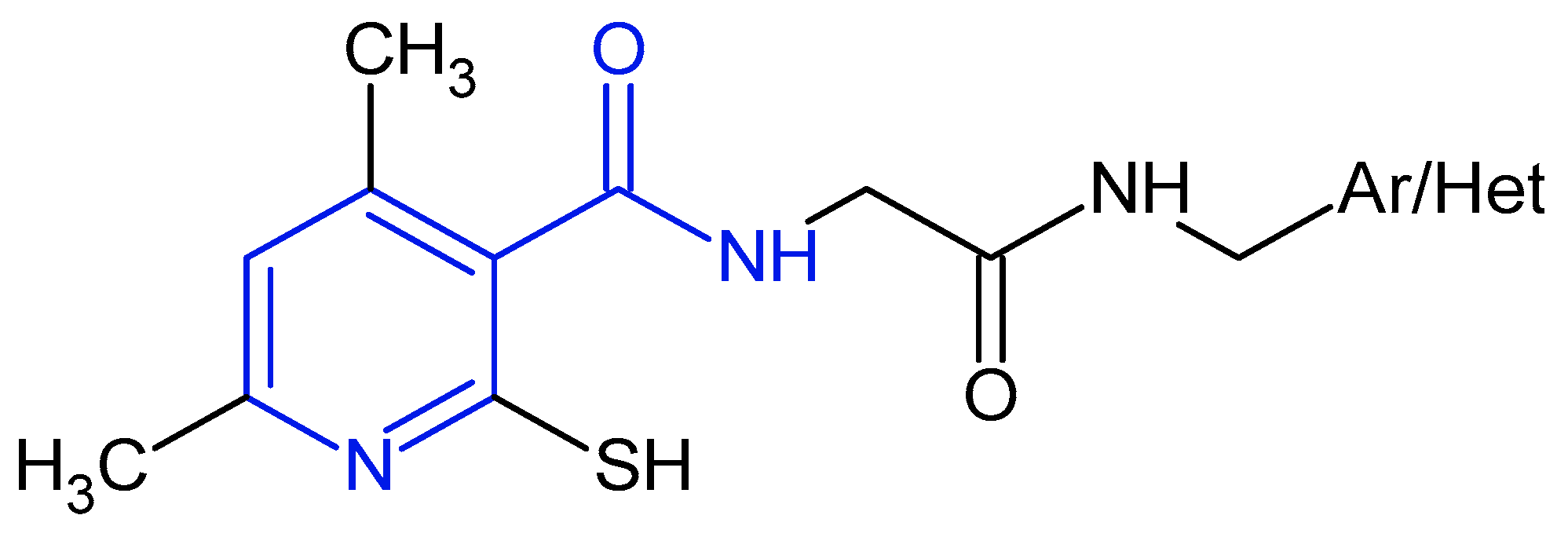

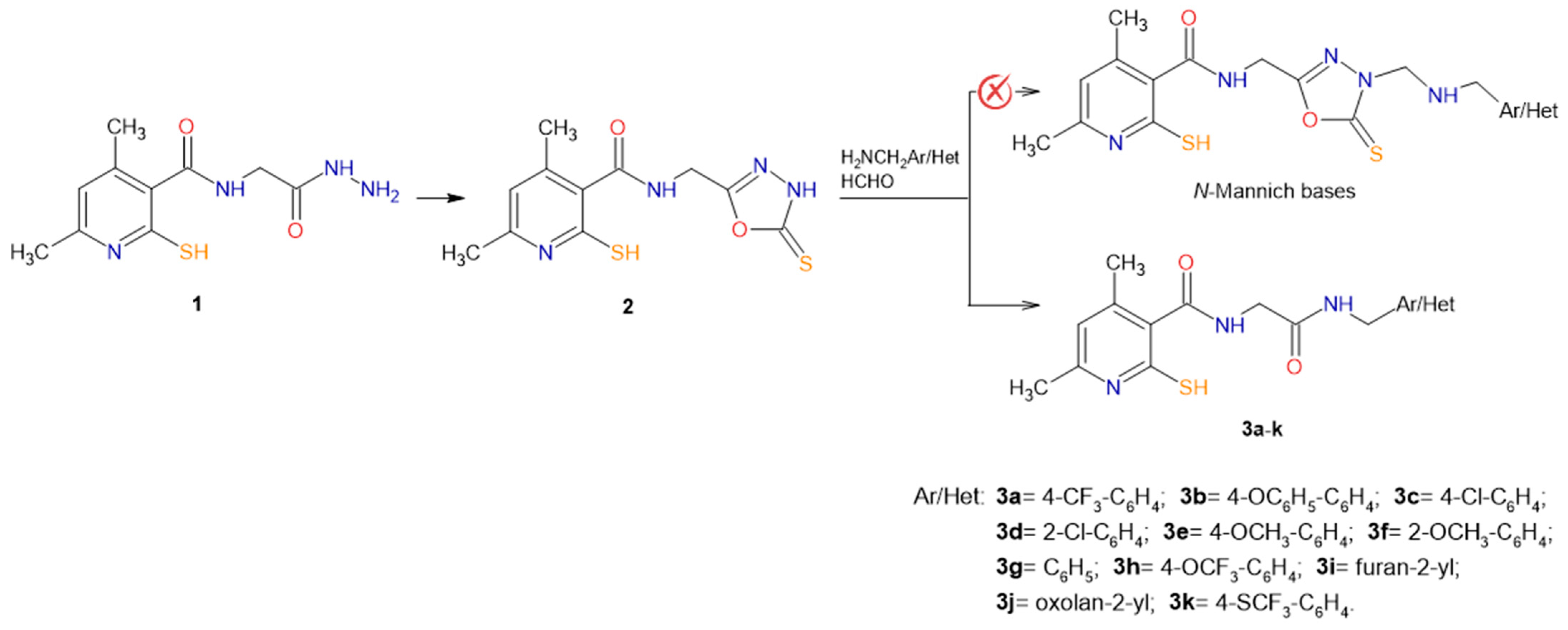

2.1. Chemistry

2.2. Properties of Designed Compounds

2.2.1. Reactivity Parameters

2.2.2. ADMET Evaluations

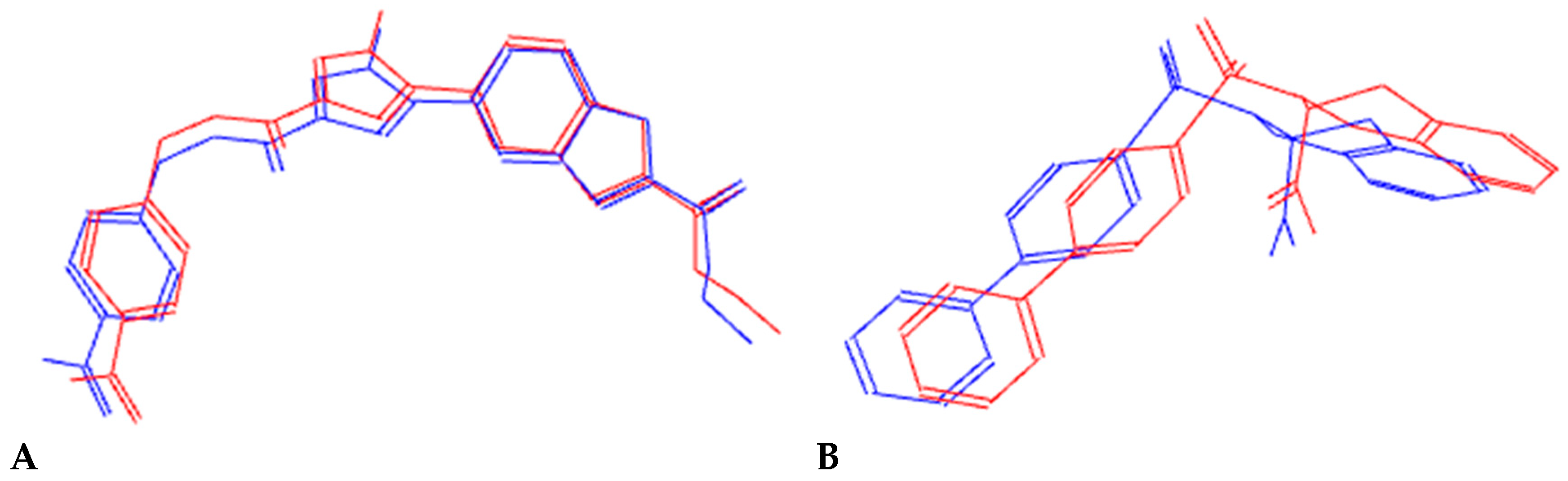

2.3. Molecular Docking and Molecular Dynamics

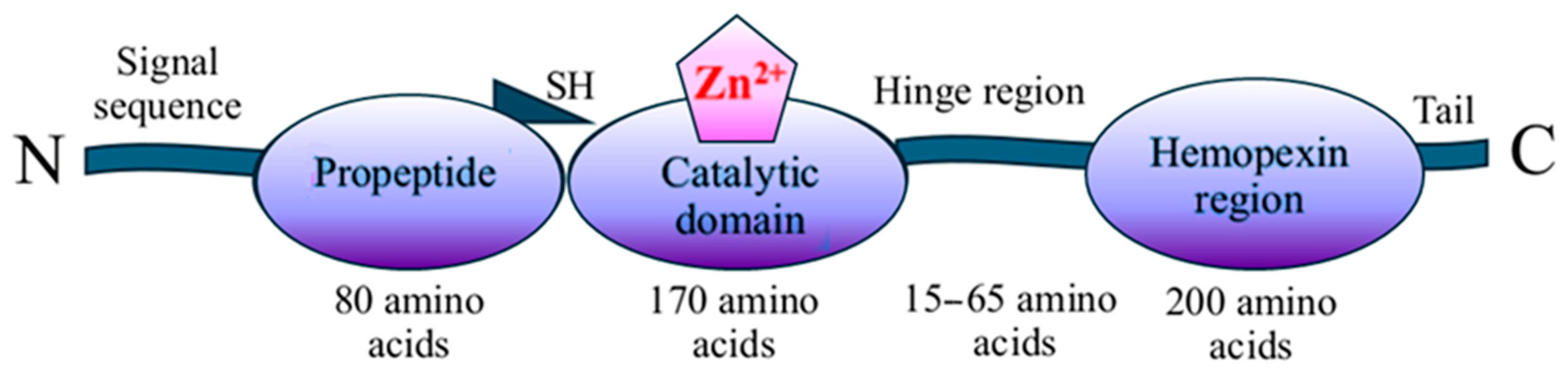

2.3.1. Molecular Targets

2.3.2. Molecular Docking

2.3.3. Molecular Dynamic Simulations

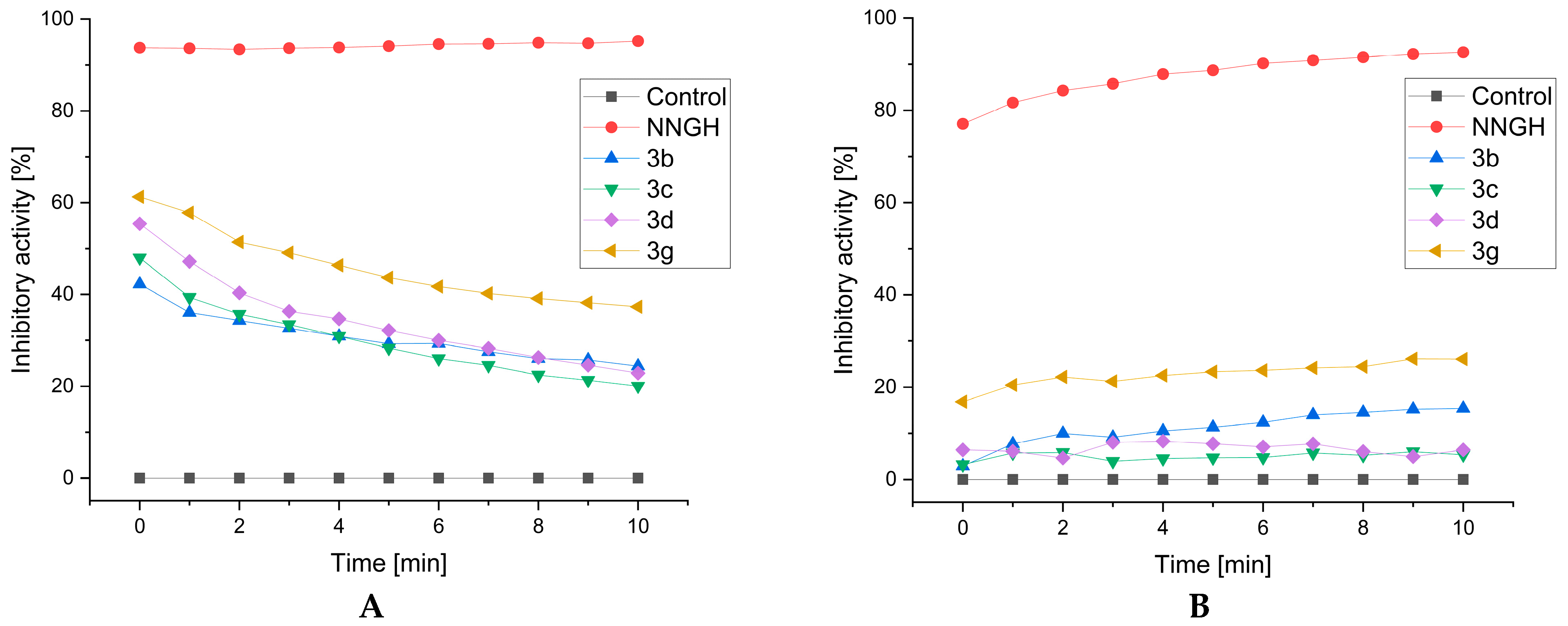

2.4. MMP-13 and MMP-8 Inhibitory Activity

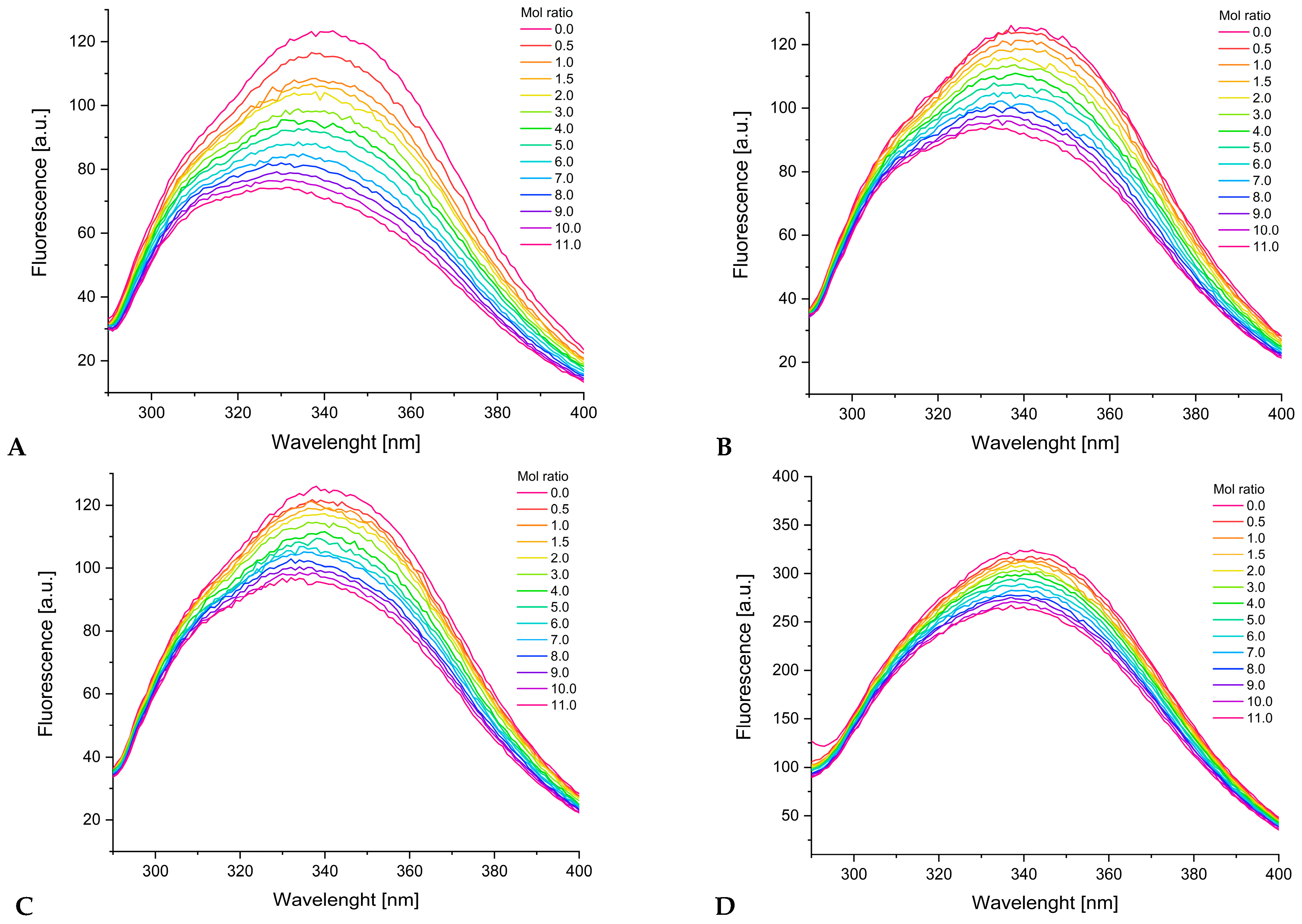

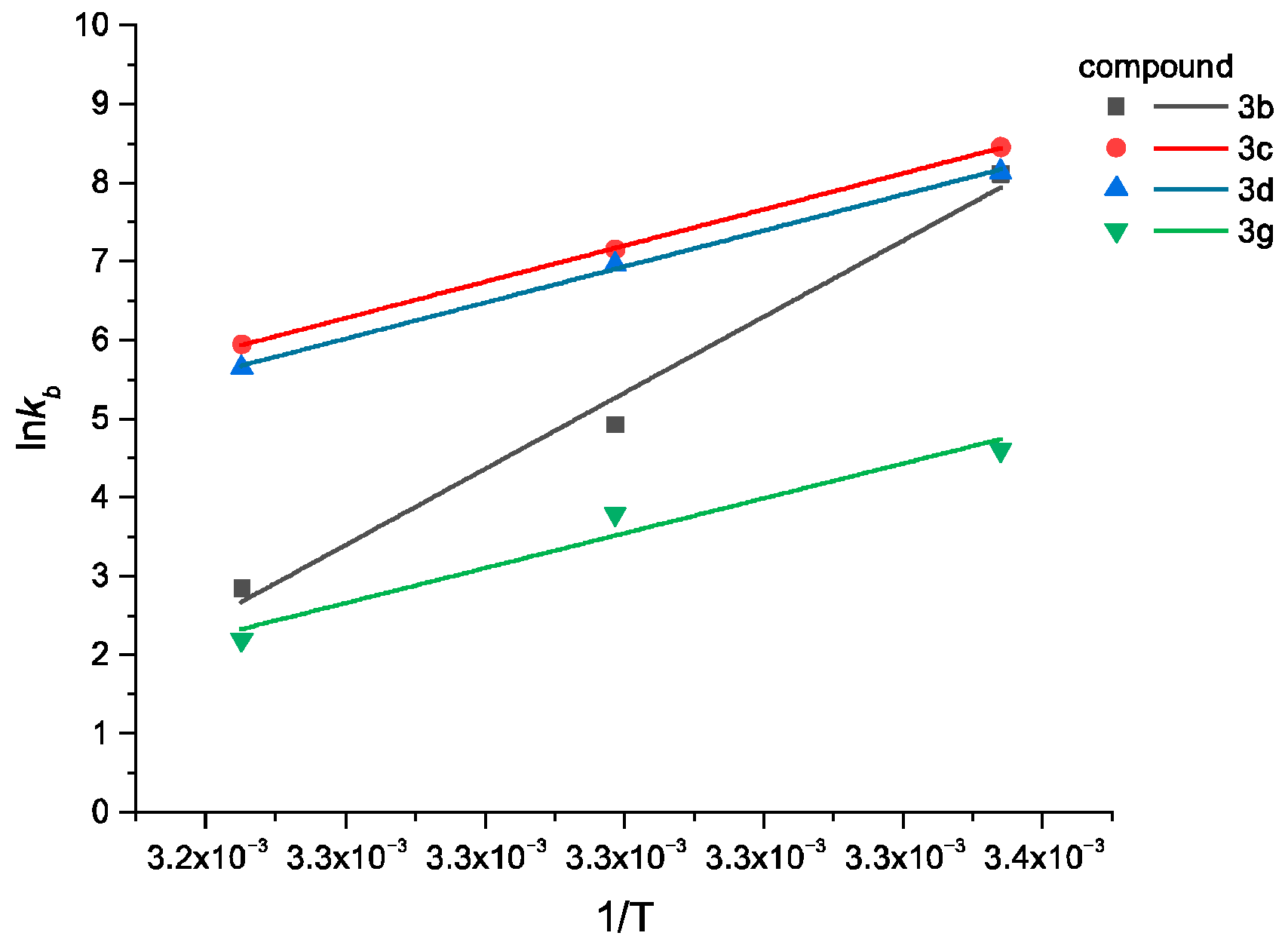

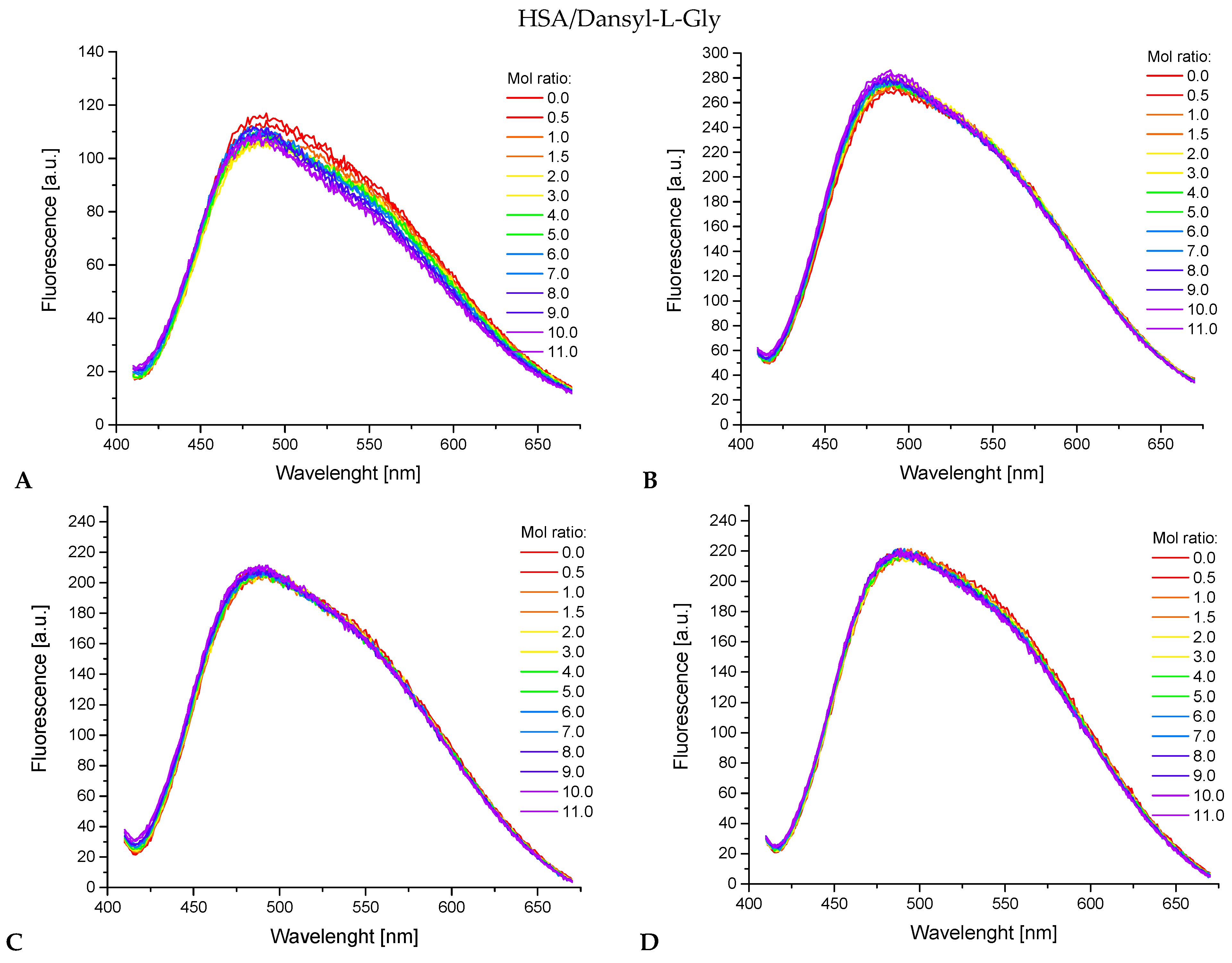

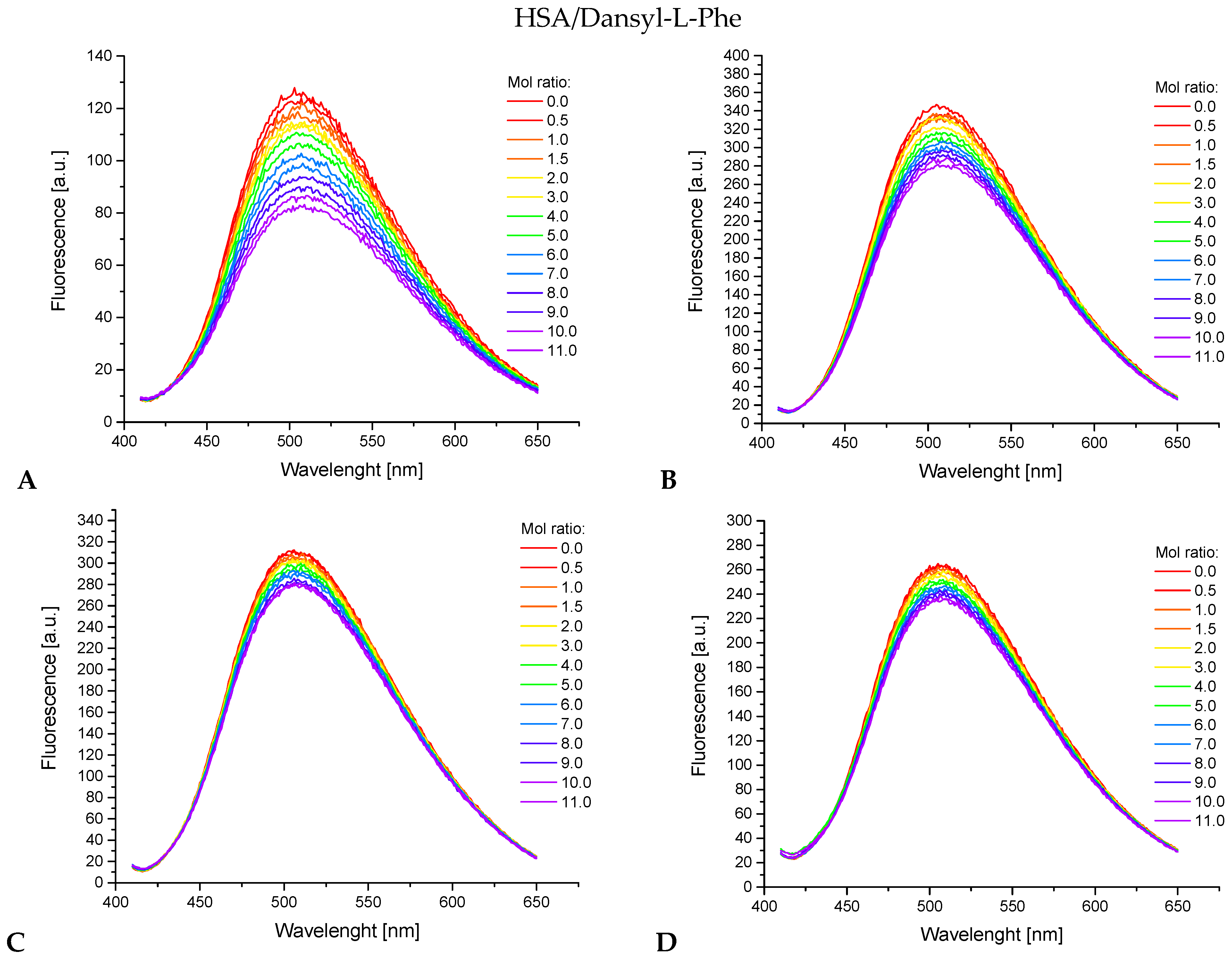

2.5. Fluorescence Spectroscopy and UV-Vis Measurements

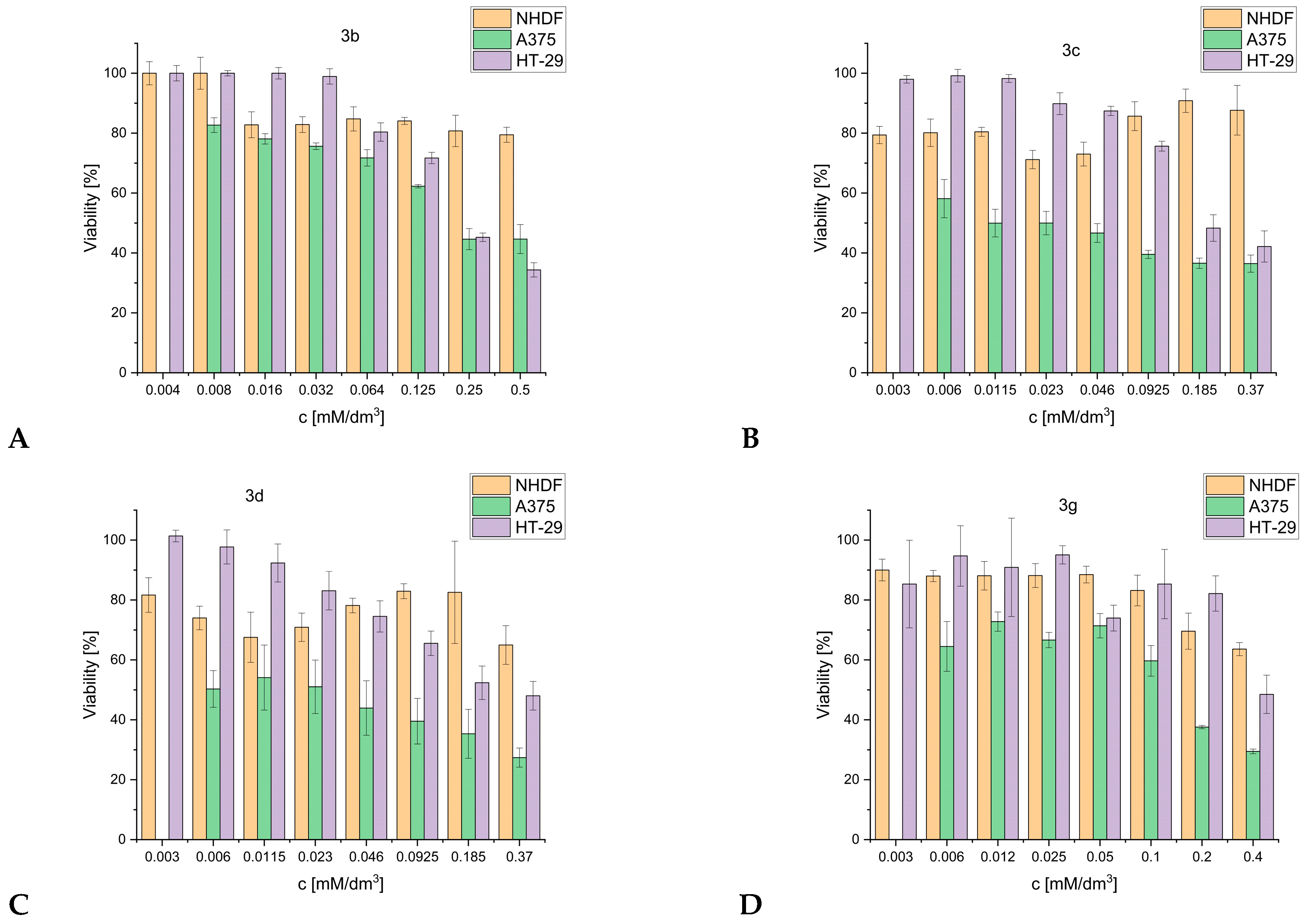

2.6. Anticancer Activity

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemistry

3.1.1. General Comments

3.1.2. General Procedure for the Synthesis of 4,6-Dimethyl-N-{2-[(substituted-methyl)amino]-2-oxoethyl}-2-sulfanylpyridine-3-carboxamide Derivatives 3a–k

3.2. Computational Studies

3.2.1. Geometry and Properties of Designed Compounds

3.2.2. Molecular Docking

3.2.3. Molecular Dynamic Simulations

3.2.4. ADMET Evaluation

3.3. MMP-13 and MMP-8 Inhibitory Assay

3.4. Fluorescence and UV-Vis Studies

3.4.1. Binding to Human Serum Albumin

3.4.2. Determination of Specific Pocket in Human Serum Albumin

3.5. Cell Culture

3.5.1. Cell Lines Conditions

3.5.2. MTT Assay

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grillet, B.; Pereira, R.V.S.; Van Damme, J.; Abu El-Asrar, A.; Proost, P.; Opdenakker, G. Matrix Metalloproteinases in Arthritis: Towards Precision Medicine. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2023, 19, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Novel Drug Discovery Approaches for MMP-13 Inhibitors in the Treatment of Osteoarthritis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2024, 114, 130009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Li, W.; Liao, Z.; Yan, M.; Chen, X.; Tang, Z. Selective MMP-13 Inhibitors: Promising Agents for the Therapy of Osteoarthritis. Curr. Med. Chem. 2020, 27, 3753–3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigrino, P.; Kuhn, I.; Bäuerle, T.; Zamek, J.; Fox, J.W.; Neumann, S.; Licht, A.; Schorpp-Kistner, M.; Angel, P.; Mauch, C. Stromal Expression of MMP-13 Is Required for Melanoma Invasion and Metastasis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2009, 129, 2686–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczygielski, O.; Dąbrowska, E.; Niemyjska, S.; Przylipiak, A.; Zajkowska, M. Targeting Matrix Metalloproteinases and Their Inhibitors in Melanoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Sun, B.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Wang, X.; Gu, Q.; Zhao, J.; Dong, X.; Liu, Z.; et al. Dual Effects of Collagenase-3 on Melanoma: Metastasis Promotion and Disruption of Vasculogenic Mimicry. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 8890–8899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merchant, N.; Alam, A. Matrix Metalloproteinases in Colorectal Cancer. Onco Ther. 2022, 9, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonsa, A.M.; VanSaun, M.N.; Ustione, A.; Piston, D.W.; Fingleton, B.M.; Gorden, D.L. Host and Tumor Derived MMP13 Regulate Extravasation and Establishment of Colorectal Metastases in the Liver. Mol. Cancer 2015, 14, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, T.; Oshima, T.; Yoshihara, K.; Tamura, S.; Kanazawa, A.; Inagaki, D.; Yamamoto, N.; Sato, T.; Fujii, S.; Numata, K.; et al. Overexpression of MMP-13 Gene in Colorectal Cancer with Liver Metastasis. Anticancer. Res. 2010, 30, 2693–2699. [Google Scholar]

- Morcos, C.A.; Khattab, S.N.; Haiba, N.S.; Bassily, R.W.; Abu-Serie, M.M.; Teleb, M. Battling Colorectal Cancer via S-Triazine-Based MMP-10/13 Inhibitors Armed with Electrophilic Warheads for Concomitant Ferroptosis Induction; the First-in-Class Dual-Acting Agents. Bioorg. Chem. 2023, 141, 106839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Ecker, M. Overview of MMP-13 as a Promising Target for the Treatment of Osteoarthritis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuffaro, D.; Gimeno, A.; Bernardoni, B.L.; Di Leo, R.; Pujadas, G.; Garcia-Vallvé, S.; Nencetti, S.; Rossello, A.; Nuti, E. Identification of N-Acyl Hydrazones as New Non-Zinc-Binding MMP-13 Inhibitors by Structure-Based Virtual Screening Studies and Chemical Optimization. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.R.; Pavlovsky, A.G.; Ortwine, D.F.; Prior, F.; Man, C.-F.; Bornemeier, D.A.; Banotai, C.A.; Mueller, W.T.; McConnell, P.; Yan, C.; et al. Discovery and Characterization of a Novel Inhibitor of Matrix Metalloprotease-13 That Reduces Cartilage Damage in Vivo without Joint Fibroplasia Side Effects. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 27781–27791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuti, E.; Casalini, F.; Avramova, S.I.; Santamaria, S.; Cercignani, G.; Marinelli, L.; La Pietra, V.; Novellino, E.; Orlandini, E.; Nencetti, S.; et al. N-O-Isopropyl Sulfonamido-Based Hydroxamates: Design, Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Selective Matrix Metalloproteinase-13 Inhibitors as Potential Therapeutic Agents for Osteoarthritis. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 4757–4773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monovich, L.G.; Tommasi, R.A.; Fujimoto, R.A.; Blancuzzi, V.; Clark, K.; Cornell, W.D.; Doti, R.; Doughty, J.; Fang, J.; Farley, D.; et al. Discovery of Potent, Selective, and Orally Active Carboxylic Acid Based Inhibitors of Matrix Metalloproteinase-13. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 3523–3538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nara, H.; Sato, K.; Kaieda, A.; Oki, H.; Kuno, H.; Santou, T.; Kanzaki, N.; Terauchi, J.; Uchikawa, O.; Kori, M. Design, Synthesis, and Biological Activity of Novel, Potent, and Highly Selective Fused Pyrimidine-2-Carboxamide-4-One-Based Matrix Metalloproteinase (MMP)-13 Zinc-Binding Inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2016, 24, 6149–6165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nara, H.; Kaieda, A.; Sato, K.; Naito, T.; Mototani, H.; Oki, H.; Yamamoto, Y.; Kuno, H.; Santou, T.; Kanzaki, N.; et al. Discovery of Novel, Highly Potent, and Selective Matrix Metalloproteinase (MMP)-13 Inhibitors with a 1,2,4-Triazol-3-Yl Moiety as a Zinc Binding Group Using a Structure-Based Design Approach. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 608–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.J.; Nahra, J.; Johnson, A.R.; Bunker, A.; O’Brien, P.; Yue, W.-S.; Ortwine, D.F.; Man, C.-F.; Baragi, V.; Kilgore, K.; et al. Quinazolinones and Pyrido[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4-Ones as Orally Active and Specific Matrix Metalloproteinase-13 Inhibitors for the Treatment of Osteoarthritis. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 835–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnute, M.E.; O’Brien, P.M.; Nahra, J.; Morris, M.; Howard Roark, W.; Hanau, C.E.; Ruminski, P.G.; Scholten, J.A.; Fletcher, T.R.; Hamper, B.C.; et al. Discovery of (Pyridin-4-Yl)-2H-Tetrazole as a Novel Scaffold to Identify Highly Selective Matrix Metalloproteinase-13 Inhibitors for the Treatment of Osteoarthritis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 576–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Świątek, P.; Saczko, J.; Rembiałkowska, N.; Kulbacka, J. Synthesis of New Hydrazone Derivatives and Evaluation of Their Efficacy as Proliferation Inhibitors in Human Cancer Cells. Med. Chem. 2019, 15, 903–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świątek, P.; Glomb, T.; Wiatrak, B.; Nowotarska, P.; Gębarowski, T.; Wojtkowiak, K.; Jezierska, A.; Strzelecka, M. New 1,2,4-Triazole Derivatives with a N-Mannich Base Structure Based on a 4,6-Dimethylpyridine Scaffold as Anticancer Agents: Design, Synthesis, Biological Evaluation, and Molecular Modeling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świątek, P.; Glomb, T.; Dobosz, A.; Gębarowski, T.; Wojtkowiak, K.; Jezierska, A.; Panek, J.J.; Świątek, M.; Strzelecka, M. Biological Evaluation and Molecular Docking Studies of Novel 1,3,4-Oxadiazole Derivatives of 4,6-Dimethyl-2-Sulfanylpyridine-3-Carboxamide. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strzelecka, M.; Glomb, T.; Drąg-Zalesińska, M.; Kulbacka, J.; Szewczyk, A.; Saczko, J.; Kasperkiewicz-Wasilewska, P.; Rembiałkowska, N.; Wojtkowiak, K.; Jezierska, A.; et al. Synthesis, Anticancer Activity and Molecular Docking Studies of Novel N-Mannich Bases of 1,3,4-Oxadiazole Based on 4,6-Dimethylpyridine Scaffold. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stempel, A.; Zelauskas, J.; Aeschlimann, J.A. Preparation of 5-substituted-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2(3H)ones and their reactions. J. Org. Chem. 1955, 20, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, W.R.; Esch, A. Von Ring-Opening Reactions of 1,3,4-Oxadiazol-2-Ones and Thiones. J. Org. Chem. 1962, 27, 3472–3475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagase, H.; Visse, R.; Murphy, G. Structure and Function of Matrix Metalloproteinases and TIMPs. Cardiovasc. Res. 2006, 69, 562–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, C.K.; Pirard, B.; Schimanski, S.; Kirsch, R.; Habermann, J.; Klingler, O.; Schlotte, V.; Weithmann, K.U.; Wendt, K.U. Structural Basis for the Highly Selective Inhibition of MMP-13. Chem. Biol. 2005, 12, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavuzzo, E.; Pochetti, G.; Mazza, F.; Gallina, C.; Gorini, B.; D’Alessio, S.; Pieper, M.; Tschesche, H.; Tucker, P.A. Two Crystal Structures of Human Neutrophil Collagenase, One Complexed with a Primed- and the Other with an Unprimed-Side Inhibitor: Implications for Drug Design. J. Med. Chem. 2000, 43, 3377–3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thirkettle, S.; Decock, J.; Arnold, H.; Pennington, C.J.; Jaworski, D.M.; Edwards, D.R. Matrix Metalloproteinase 8 (Collagenase 2) Induces the Expression of Interleukins 6 and 8 in Breast Cancer Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 16282–16294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.J.; Abeywardane, A.; Liang, S.; Muegge, I.; Padyana, A.K.; Xiong, Z.; Hill-Drzewi, M.; Farmer, B.; Li, X.; Collins, B.; et al. Fragment-Based Discovery of Indole Inhibitors of Matrix Metalloproteinase-13. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 8174–8187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhou, H.; Guan, C.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Jiang, X.; Dong, Z.; Tao, Y.; Du, J.; Wang, S.; et al. Applicability of Free Drug Hypothesis to Drugs with Good Membrane Permeability That Are Not Efflux Transporter Substrates: A Microdialysis Study in Rats. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2020, 8, e00575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, D.; Schmidt, S.; Derendorf, H. Importance of Relating Efficacy Measures to Unbound Drug Concentrations for Anti-Infective Agents. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2013, 26, 274–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammarlund-Udenaes, M. Active-Site Concentrations of Chemicals—Are They a Better Predictor of Effect than Plasma/Organ/Tissue Concentrations? Basic. Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2010, 106, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A.; Pea, F.; Lipman, J. The Clinical Relevance of Plasma Protein Binding Changes. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2013, 52, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birn, H.; Christensen, E.I. Renal Albumin Absorption in Physiology and Pathology. Kidney Int. 2006, 69, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohnert, T.; Gan, L.-S. Plasma Protein Binding: From Discovery to Development. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 102, 2953–2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.M.; Carter, D.C. Atomic Structure and Chemistry of Human Serum Albumin. Nature 1992, 358, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakowicz, J.R. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; ISBN 9780387312781. [Google Scholar]

- Ware, W.R. Oxygen quenching of fluorescence in solution: An experimental study of the diffusion process. J. Phys. Chem. 1962, 66, 455–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanali, G.; di Masi, A.; Trezza, V.; Marino, M.; Fasano, M.; Ascenzi, P. Human Serum Albumin: From Bench to Bedside. Mol. Aspects Med. 2012, 33, 209–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, A.J.; Ghuman, J.; Zunszain, P.A.; Chung, C.; Curry, S. Structural Basis of Binding of Fluorescent, Site-Specific Dansylated Amino Acids to Human Serum Albumin. J. Struct. Biol. 2011, 174, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chudzik, M.; Maciążek-Jurczyk, M.; Pawełczak, B.; Sułkowska, A. Spectroscopic Studies on the Molecular Ageing of Serum Albumin. Molecules 2016, 22, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leeman, M.F. Matrix Metalloproteinase 13 Activity Is Associated with Poor Prognosis in Colorectal Cancer. J. Clin. Pathol. 2002, 55, 758–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanwell, M.D.; Curtis, D.E.; Lonie, D.C.; Vandermeersch, T.; Zurek, E.; Hutchison, G.R. Avogadro: An Advanced Semantic Chemical Editor, Visualization, and Analysis Platform. J. Cheminform. 2012, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16, Revision C.01.2016; Gaussian Inc.: Wallingford CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasi, J.; Mennucci, B.; Cammi, R. Quantum Mechanical Continuum Solvation Models. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 2999–3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janak, J.F. Proof That in Density-Functional Theory. Phys. Rev. B 1978, 18, 7165–7168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, R.G.; Szentpály, L.v.; Liu, S. Electrophilicity Index. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 1922–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, H.M. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matter, H.; Schwab, W.; Barbier, D.; Billen, G.; Haase, B.; Neises, B.; Schudok, M.; Thorwart, W.; Schreuder, H.; Brachvogel, V.; et al. Quantitative Structure−Activity Relationship of Human Neutrophil Collagenase (MMP-8) Inhibitors Using Comparative Molecular Field Analysis and X-Ray Structure Analysis. J. Med. Chem. 1999, 42, 1908–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Martins, D.; Forli, S.; Ramos, M.J.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock4Zn: An Improved AutoDock Force Field for Small-Molecule Docking to Zinc Metalloproteins. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2014, 54, 2371–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.M.; Huey, R.; Lindstrom, W.; Sanner, M.F.; Belew, R.K.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated Docking with Selective Receptor Flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Menche, G.; Power, T.D.; Sower, L.; Peterson, J.W.; Schein, C.H. Accounting for Ligand-bound Metal Ions in Docking Small Molecules on Adenylyl Cyclase Toxins. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2007, 67, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velázquez-Libera, J.L.; Durán-Verdugo, F.; Valdés-Jiménez, A.; Núñez-Vivanco, G.; Caballero, J. LigRMSD: A Web Server for Automatic Structure Matching and RMSD Calculations among Identical and Similar Compounds in Protein-Ligand Docking. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 2912–2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, M.J.; Murtola, T.; Schulz, R.; Páll, S.; Smith, J.C.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E. GROMACS: High Performance Molecular Simulations through Multi-Level Parallelism from Laptops to Supercomputers. SoftwareX 2015, 1–2, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.; Kim, T.; Iyer, V.G.; Im, W. CHARMM-GUI: A Web-based Graphical User Interface for CHARMM. J. Comput. Chem. 2008, 29, 1859–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanommeslaeghe, K.; Hatcher, E.; Acharya, C.; Kundu, S.; Zhong, S.; Shim, J.; Darian, E.; Guvench, O.; Lopes, P.; Vorobyov, I.; et al. CHARMM General Force Field: A Force Field for Drug-like Molecules Compatible with the CHARMM All-atom Additive Biological Force Fields. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 671–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKerell, A.D.; Bashford, D.; Bellott, M.; Dunbrack, R.L.; Evanseck, J.D.; Field, M.J.; Fischer, S.; Gao, J.; Guo, H.; Ha, S.; et al. All-Atom Empirical Potential for Molecular Modeling and Dynamics Studies of Proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102, 3586–3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, B.R.; Brooks, C.L.; Mackerell, A.D.; Nilsson, L.; Petrella, R.J.; Roux, B.; Won, Y.; Archontis, G.; Bartels, C.; Boresch, S.; et al. CHARMM: The Biomolecular Simulation Program. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 1545–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Cheng, X.; Swails, J.M.; Yeom, M.S.; Eastman, P.K.; Lemkul, J.A.; Wei, S.; Buckner, J.; Jeong, J.C.; Qi, Y.; et al. CHARMM-GUI Input Generator for NAMD, GROMACS, AMBER, OpenMM, and CHARMM/OpenMM Simulations Using the CHARMM36 Additive Force Field. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2016, 12, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdés-Tresanco, M.S.; Valdés-Tresanco, M.E.; Valiente, P.A.; Moreno, E. Gmx_MMPBSA: A New Tool to Perform End-State Free Energy Calculations with GROMACS. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2021, 17, 6281–6291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Origin(Pro), version 10.1; OriginLab Corporation: Northampton, MA, USA, 2024.

- Xiong, G.; Wu, Z.; Yi, J.; Fu, L.; Yang, Z.; Hsieh, C.; Yin, M.; Zeng, X.; Wu, C.; Lu, A.; et al. ADMETlab 2.0: An Integrated Online Platform for Accurate and Comprehensive Predictions of ADMET Properties. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W5–W14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound | EHOMO | ELUMO | GAP (HOMO-LUMO) | A | I | η | s | µ | χ | ω |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3a | −6.53 | −1.42 | −5.11 | 1.42 | 6.53 | 2.56 | 0.39 | −3.97 | 3.97 | 7.89 |

| 3b | −6.14 | −1.20 | −4.94 | 1.20 | 6.14 | 2.47 | 0.40 | −3.67 | 3.67 | 6.73 |

| 3c | −6.21 | −1.26 | −4.95 | 1.26 | 6.21 | 2.47 | 0.40 | −3.73 | 3.73 | 6.97 |

| 3d | −6.26 | −1.16 | −5.09 | 1.16 | 6.26 | 2.55 | 0.39 | −3.71 | 3.71 | 6.88 |

| 3e | −6.12 | −1.17 | −4.95 | 1.17 | 6.12 | 2.47 | 0.40 | −3.65 | 3.65 | 6.64 |

| 3f | −6.11 | −1.59 | −4.52 | 1.60 | 6.11 | 2.26 | 0.44 | −3.85 | 3.85 | 7.42 |

| 3g | −6.15 | −1.21 | −4.95 | 1.21 | 6.15 | 2.47 | 0.40 | −3.68 | 3.68 | 6.77 |

| 3h | −6.33 | −1.21 | −5.11 | 1.21 | 6.33 | 2.56 | 0.39 | −3.77 | 3.77 | 7.10 |

| 3i | −6.26 | −1.09 | −5.17 | 1.09 | 6.26 | 2.58 | 0.39 | −3.68 | 3.68 | 6.76 |

| 3j | −6.68 | −1.64 | −5.04 | 1.64 | 6.68 | 2.52 | 0.40 | −4.16 | 4.16 | 8.65 |

| 3k | −6.35 | −1.71 | −4.64 | 1.71 | 6.35 | 2.32 | 0.43 | −4.03 | 4.03 | 8.13 |

| Properties: | 3b | 3c | 3d | 3g |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipinski Rule | Accepted | Accepted | Accepted | Accepted |

| TPSA | 80.32 | 71.09 | 71.09 | 71.09 |

| Absorption | ||||

| Caco-2 Permeability | −5.30 | −5.10 | −5.58 | −5.30 |

| MDCK Premeability | −4.65 | −4.76 | −4.80 | −4.75 |

| HIA | >30% | >30% | >30% | >30% |

| Distribution | ||||

| PPB | 98.70% | 98.30% | 98.50% | 97.70% |

| VDss [L/kg] | 1.19 | 1.14 | 1.18 | 1.13 |

| Excretion | ||||

| CLplasma [mL/min/kg] | 4.18 | 4.72 | 5.07 | 4.64 |

| T1/2 [h] | 0.52 | 0.47 | 0.48 | 0.47 |

| Toxicity The output value is the probability of being toxic within the range of 0 to 1. | ||||

| hERG Blockers | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| AMES Toxicity | 0.83 | 0.66 | 0.62 | 0.69 |

| Rat Oral Acute Toxicity | 0.25 | 0.32 | 0.40 | 0.34 |

| Carcinogenicity | 0.49 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.11 |

| Enzyme | Hydrogen Bonds | π-Type Interactions with the Heterocyclic or Aromatic Ring of the Inhibitor |

|---|---|---|

| MMP-13 | Lys140 Thr245 Thr247 Met253 | Phe217 Leu218 His222 |

| MMP-8 | Leu160 Ala161 | Tyr219 His197 |

| Compound: | MMP-13 | MMP-8 |

|---|---|---|

| 4FU | −38.97 | - |

| 3b | −38.62 | −19.48 |

| 3c | −36.61 | −14.70 |

| 3d | −33.89 | −19.35 |

| 3g | −21.64 | −15.64 |

| Compound | Quenching | Binding | Thermodynamic | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | KSV·104 | kq·1012 | logKb | Kb·103 | n | ΔG0 | ΔH0 | ΔS0 | |

| [K] | [dm3·mol−1] | [dm3·mol−1·s−1] | [dm3·mol−1] | [kJ·mol−1] | [kJ·mol−1] | [J·mol−1·K−1] | |||

| 3b | 297 | 1.21 | 1.21 | 3.52 | 3.32 | 0.89 | −13.29 | −402.16 | −1282.70 |

| 303 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 2.14 | 0.14 | 0.60 | ||||

| 308 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 1.24 | 0.17 | 0.44 | ||||

| 3c | 297 | 2.69 | 2.69 | 3.67 | 4.65 | 0.84 | −18.07 | −191.19 | −571.09 |

| 303 | 2.34 | 2.34 | 3.11 | 1.28 | 0.74 | ||||

| 308 | 2.07 | 2.07 | 2.58 | 0.38 | 0.65 | ||||

| 3d | 297 | 2.51 | 2.51 | 3.53 | 34.18 | 0.82 | −17.39 | −190.25 | −570.21 |

| 303 | 2.13 | 2.13 | 3.03 | 10.59 | 0.73 | ||||

| 308 | 1.88 | 1.88 | 2.45 | 0.28 | 0.63 | ||||

| 3g | 297 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 2.01 | 0.10 | 0.60 | −8.86 | −184.42 | −579.14 |

| 303 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 1.65 | 0.04 | 0.54 | ||||

| 308 | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.95 | 0.01 | 0.42 | ||||

| Compound | Marker Displacement Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| HSA/Dansyl-L-Gly | HSA/Dansyl-L-Gly | |

| 3b | 8.6% | 35.2% |

| 3c | - | 18.5% |

| 3d | - | 10.6% |

| 3g | - | 11.1% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Płaczek, R.; Janek, T.; Strzelecka, M.; Kotynia, A.; Świątek, P.; Czyżnikowska, Ż. New Dimethylpyridine-3-Carboxamide Derivatives as MMP-13 Inhibitors with Anticancer Activity. Molecules 2025, 30, 4662. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244662

Płaczek R, Janek T, Strzelecka M, Kotynia A, Świątek P, Czyżnikowska Ż. New Dimethylpyridine-3-Carboxamide Derivatives as MMP-13 Inhibitors with Anticancer Activity. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4662. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244662

Chicago/Turabian StylePłaczek, Remigiusz, Tomasz Janek, Małgorzata Strzelecka, Aleksandra Kotynia, Piotr Świątek, and Żaneta Czyżnikowska. 2025. "New Dimethylpyridine-3-Carboxamide Derivatives as MMP-13 Inhibitors with Anticancer Activity" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4662. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244662

APA StylePłaczek, R., Janek, T., Strzelecka, M., Kotynia, A., Świątek, P., & Czyżnikowska, Ż. (2025). New Dimethylpyridine-3-Carboxamide Derivatives as MMP-13 Inhibitors with Anticancer Activity. Molecules, 30(24), 4662. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244662