Computational Study of Graphene Quantum Dots (GQDs) Functionalized with Thiol and Amino Groups for the Selective Detection of Heavy Metals in Wastewater

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Methods Selection

2.2. Representative Models

2.3. Analysis of Energy Gap (Eg) and Total Dipolar Moment (TDM) Parameters

2.4. Calculations of the Energy Gap Between Orbitals (HOMO-LUMO)

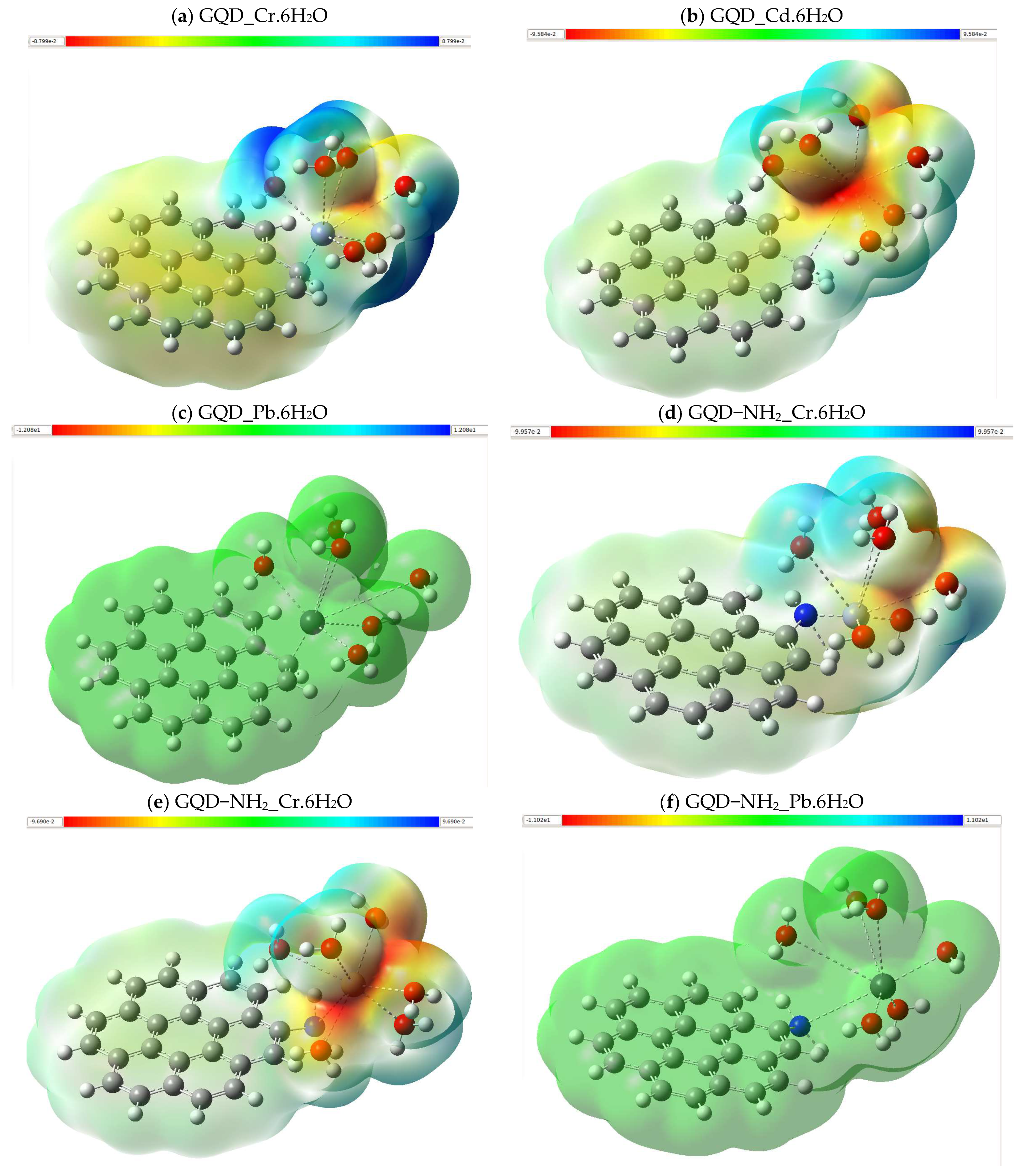

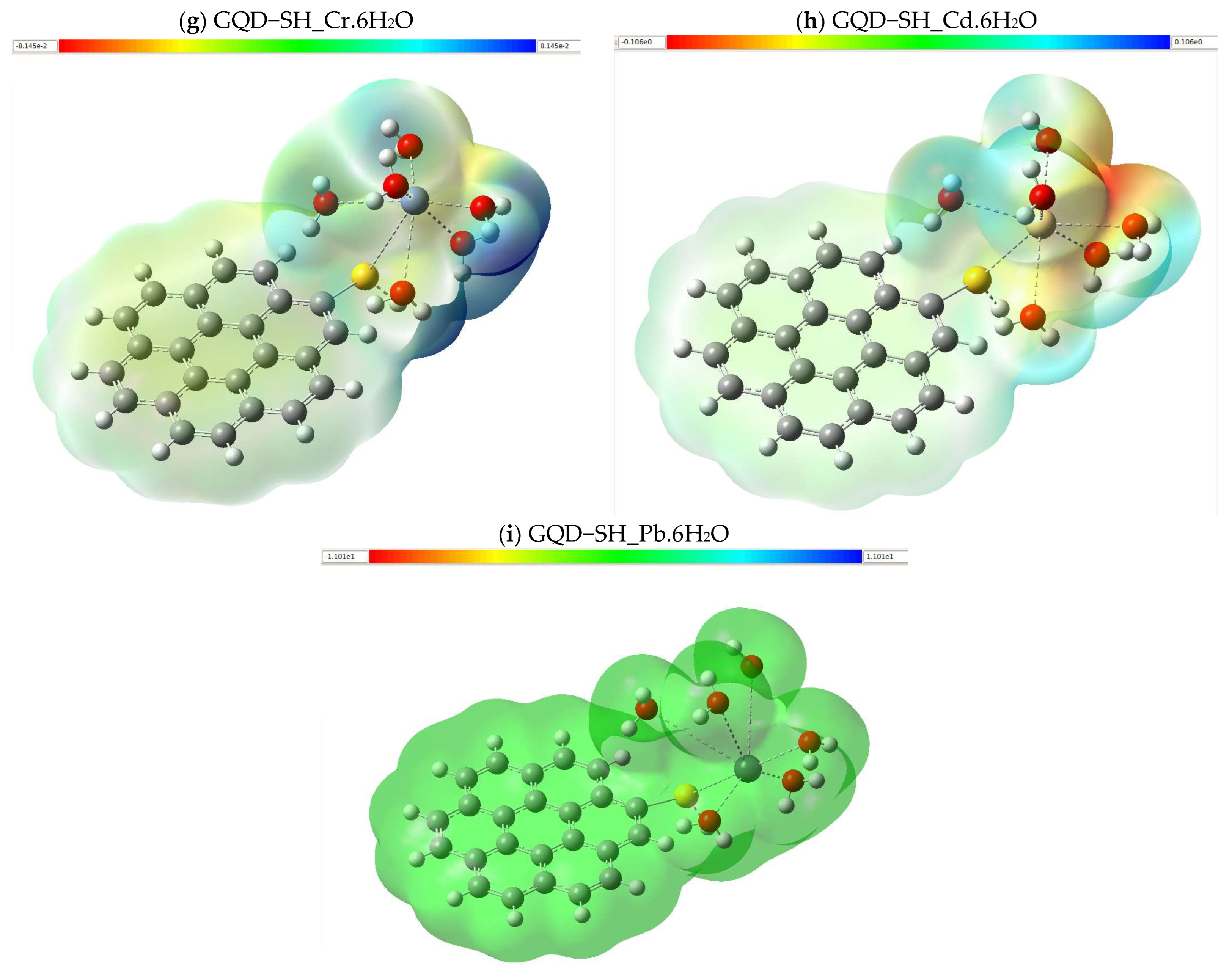

2.5. Electrostatic Potential Map (MEP)

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Computational Details

3.2. Evaluation of Electronic Properties

3.2.1. Calculating the Energy Gap (Eg)

3.2.2. Total Dipole Moment (TMD)

3.2.3. Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP)

4. Conclusions

5. Supplementary Information

- Electron affinity (A): Refers to the energy released when the system accepts an extra electron in the LUMO. A high A indicates a good performance as an electron acceptor, which is significant in interactions with heavy metals that can function as partial donors in coordination complexes [62,63,64,65,66].

- Chemical hardness (η): It evaluates the system’s ability to withstand changes in its electron density. High-hardness systems show lower chemical reactivity, indicating greater stability. In contrast, low hardness indicates a greater ability of the system to interact with external elements such as hydrated metal ions [61,63].

- Electronegativity (χ): This global parameter, calculated as the average between I and A, characterizes the system’s ability to attract electrons to itself during a chemical interaction. High electronegativity leads to a stronger polar interaction, which favors adsorption or complexation processes with species [64,65].

- Chemical potential (µ): It represents the system’s inherent tendency to acquire or donate electrons based on its electronic configuration and its interaction with other chemical elements in its environment. Significantly low µ values indicate that the molecule has a greater natural tendency to donate electrons, while notably high values suggest a more pronounced acceptor nature. This molecular descriptor makes it possible to predict in advance the preferential interaction of functionalized derivative-quality graphene with electrophilic metal ions [63,66].

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sankhla, M.S.; Kumari, M.; Nandan, M.; Kumar, R.; Agrawal, P. Heavy Metals Contamination in Water and their Hazardous Effect on Human Health—A Review. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2016, 5, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, L.A.; Bashir, A.; Qureashi, A.; Pandith, A.H. Detection and removal of heavy metal ions: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2019, 17, 1495–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, L.C.; Gaur, J.P.; Kumar, H.D. Phycology and heavy-metal pollution. Biol. Rev. 1981, 56, 99–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhou, K.; Qin, W.; Tian, C.; Qi, M.; Yan, X.; Han, W. A Review on Heavy Metals Contamination in Soil: Effects, Sources, and Remediation Techniques. Soil Sediment Contam. Int. J. 2019, 28, 380–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Yang, N.; Li, Y.; Ren, B.; Ding, X.; Bian, H.; Yao, X. Total concentrations and sources of heavy metal pollution in global river and lake water bodies from 1972 to 2017. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 22, e00925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-H.; Li, Y.-X.; Li, P.-H.; Xiao, X.-Y.; Jiang, M.; Li, S.-S.; Zhou, W.-Y.; Yang, M.; Huang, X.-J.; Liu, W.-Q. Electrochemical spectral methods for trace detection of heavy metals: A review. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2018, 106, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Li, C.; Wang, H.; Xu, C.; Kuang, H. Electrochemical detection of heavy metal ions in water. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 7215–7231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehme, I.; Wolfbeis, O.S. Optical Sensors for Determination of Heavy Metal Ions. Mikrochim. Acta 1997, 126, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Saeed, M.; Tawfik, W.; Khalil, A.A.I.; Fikry, M. Detection of heavy metal elements by using advanced optical techniques. J. Egypt. Soc. Basic Sci. 2024, 1, 99–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochsenkühn-Petropoulou, M.; Ochsenkühn, K.M. Comparison of inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission spectrometry, anodic stripping voltammetry and instrumental neutron-activation analysis for the determination of heavy metals in airborne particulate matter. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2001, 369, 629–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosolina, S.M.; Chambers, J.Q.; Lee, C.W.; Xue, Z.L. Direct determination of cadmium and lead in pharmaceutical ingredients using anodic stripping voltammetry in aqueous and DMSO/water solutions. Anal. Chim. Acta 2015, 893, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, Z.; Ross, A.; Huang, Z.; Chang, W.; Ou-Yang, K.; Chen, Y.; Wu, C. Determination of heavy metals in leather and fur by microwave plasma-atomic emission spectrometry. Acta Part B At. Spectrosc. 2015, 112, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; Cheong, Y.H.; Ahamed, A.; Lisak, G. Heavy Metals Detection with Paper-Based Electrochemical Sensors. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 1880–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Guo, Y.; Liu, H.; Yan, N.; Xu, Z.; Yu, G.; Fang, Y.; Liu, Y. Ultrasensitive and selective sensing of heavy metal ions with modified graphene. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 6492–6494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anas, N.A.A.; Fen, Y.W.; Omar, N.A.S.; Daniyal, W.M.E.M.M.; Ramdzan, N.S.M.; Saleviter, S. Development of Graphene Quantum Dots-Based Optical Sensor for Toxic Metal Ion Detection. Sensors 2019, 19, 3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, S.; Zahra, Q.U.A.; Mansoorianfar, M.; Hussain, Z.; Ullah, I.; Li, W.; Kamya, E.; Mehmood, S.; Pei, R.; Wang, J. Heavy Metal Ions Detection Using Nanomaterials-Based Aptasensors. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2024, 54, 1399–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yao, Y.; Ying, Y.; Ping, J. Recent advances in nanomaterial-enabled screen-printed electrochemical sensors for heavy metal detection. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 115, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buledi, J.A.; Amin, S.; Haider, S.I.; Bhanger, M.I.; Solangi, A.R. A review on detection of heavy metals from aqueous media using nanomaterial-based sensors. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 58994–59002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragay, G.; Merkoçi, A. Nanomaterials application in electrochemical detection of heavy metals. Electrochim. Acta 2012, 84, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Deng, Y.; Dong, H.; Liu, K.; He, N. Progress on sensors based on nanomaterials for rapid detection of heavy metal ions. Sci. China Chem. 2017, 60, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, A.; Mansha, M.; Ullah, N. Nanomaterials-based electrochemical detection of heavy metals in water: Current status, challenges and future direction. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2018, 105, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amina; Munir, R.; Jahan, N.; Nadeem, R.; Bashir, M.Z.; Ambreen, H.; Noreen, S. A Review on Quantum Dots: Revolutionizing Waste Water Cleaning. Chem. Afr. 2024, 7, 5009–5023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Ye, K.; Hu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Geng, B.; Pan, D.; Shen, L. Graphene Quantum Dots Eradicate Resistant and Metastatic Cancer Cells by Enhanced Interfacial Inhibition. Adv. Heal. Mater. 2024, 13, 2304648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, P.; Rajput, R.S.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, A.; Jain, A.; Bora, B.J.; Sharma, P.; Kumar, R.; Shahid, M.; Rajhi, A.A.; et al. Recent Advances in Graphene-Enabled Materials for Photovoltaic Applications: A Comprehensive Review. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 12403–12425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, A.; Samriti Thakur, S.; Prakash, J. Graphene family nanomaterials as emerging sole layered nanomaterials for wastewater treatment: Recent developments, potential hazards, prevention and future prospects. Environ. Adv. 2023, 13, 100402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Gu, Z.; Perez-Aguilar, J.M.; Luo, Y.; Tian, K.; Luo, Y. Molecular dynamics simulations reveal efficient heavy metal ion removal by two-dimensional Cu-THQ metal-organic framework membrane. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, A.; Batool, M.; Akram, S.; Malik, A.H.; Khanday, W.A.; Wani, W.A.; Sheikh, R.A.; Rather, J.A.; Kannan, P. Functionalized Graphene Quantum Dots (FGQDs): A review of their synthesis, properties, and emerging biomedical applications. Carbon Trends 2025, 18, 2400221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, P.; Sampath, S.; John, S.A. Direct growth of gold nanorods on gold and indium tin oxide surfaces: Spectral, electrochemical, and electrocatalytic studies. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 21114–21122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananthanarayanan, A.; Wang, X.; Routh, P.; Sana, B.; Lim, S.; Kim, D.; Lim, K.; Li, J.; Chen, P. Facile Synthesis of Graphene Quantum Dots from 3D Graphene and their Application for Fe3+ Sensing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2014, 24, 3021–3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Ji, J.; Fei, R.; Wang, C.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, L.; Zhu, J. A Facile Microwave Avenue to Electrochemiluminescent Two-Color Graphene Quantum Dots. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012, 22, 2971–2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, S.L.; Ee, S.J.; Ananthanarayanan, A.; Leong, K.C.; Chen, P. Graphene quantum dots functionalized gold nanoparticles for sensitive electrochemical detection of heavy metal ions. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 172, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, T.; Huang, J.; Wang, D.; Meng, T.; Yang, X. Au and Au-Based nanomaterials: Synthesis and recent progress in electrochemical sensor applications. Talanta 2020, 206, 120210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velempini, T.; Pillay, K. Sulphur functionalized materials for Hg(II) adsorption: A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 103350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Lee, T.; Choi, S.; Yoon, J. A density functional theory study of a series of functionalized metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2006, 420, 256–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, D.; Barakat, S.; Van Bramer, S.E.; Nelson, K.A.; Hensley, D.K.; Chen, J. Noncompetitive and Competitive Adsorption of Heavy Metals in Sulfur-Functionalized Ordered Mesoporous Carbon. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 34132–34142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.F.; Zhao, L.J.; Jiang, T.J.; Li, S.S.; Yang, M.; Huang, X.J. Sensitive and selective electrochemical detection of heavy metal ions using amino-functionalized carbon microspheres. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2016, 760, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anfar, Z.; Amedlous, A.; Majdoub, M.; El Fakir, A.A.; Zbair, M.; Ahsaine, H.A.; Jada, A.; El Alem, N. New amino group functionalized porous carbon for strong chelation ability towards toxic heavy metals. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 31087–31100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Ding, X.; Li, W.; Wu, H.; Yang, H. Highly Efficient Adsorption of Heavy Metals onto Novel Magnetic Porous Composites Modified with Amino Groups. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2017, 62, 1865–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandeep Kumar, G.; Roy, R.; Sen, D.; Ghorai, U.K.; Thapa, R.; Mazumder, N.; Saha, S.; Chattopadhyay, K.K. Amino-functionalized graphene quantum dots: Origin of tunable heterogeneous photoluminescence. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 3384–3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; Jiang, Y.; Sun, X.; Bai, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X. Surface modification and chemical functionalization of carbon dots: A review. Microchim. Acta 2018, 185, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Dong, H.; Yu, L.; Dong, L. The optical and electronic properties of graphene quantum dots with oxygen-containing groups: A density functional theory study. J. Mater. Chem. C 2017, 5, 5984–5993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Dong, H.; Pang, B.; Shao, F.; Zhang, C.; Yu, L. Theoretical study on the optical and electronic properties of graphene quantum dots doped with heteroatoms. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 15244–15252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montejo-Alvaro, F.; Oliva, J.; Herrera-Trejo, M.; Hdz-García, H.M.; Mtz-Enriquez, A.I. DFT study of small gas molecules adsorbed on undoped and N-, Si-, B-, and Al-doped graphene quantum dots. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2019, 138, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Yang, F.; Xue, Y.; Xiao, D.; Guo, Y. A Time-Dependent DFT Study of the Absorption and Fluorescence Properties of Graphene Quantum Dots. ChemPhysChem 2014, 15, 950–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shu, H.; Niu, X.; Wang, J. Electronic and Optical Properties of Edge-Functionalized Graphene Quantum Dots and the Underlying Mechanism. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 24950–24957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelsalam, H.; Elhaes, H.; Ibrahim, M.A. Tuning electronic properties in graphene quantum dots by chemical functionalization: Density functional theory calculations. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2018, 695, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shtepliuk, I.; Caffrey, N.M.; Iakimov, T.; Khranovskyy, V.; Abrikosov, I.A.; Yakimova, R. On the interaction of toxic Heavy Metals (Cd, Hg, Pb) with graphene quantum dots and infinite graphene. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, N.M.; Elhaes, H.; Ibrahim, A.; Ibrahim, M.A. Investigating the electronic properties of edge glycine/biopolymer/graphene quantum dots. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamel, M.; Raissi, H.; Hashemzadeh, H.; Mohammadifard, K. Theoretical elucidation of the amino acid interaction with graphene and functionalized graphene nanosheets: Insights from DFT calculation and MD simulation. Amino Acids 2020, 52, 1465–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajid, H.; Mahmood, T. A DFT study on M3O (M = Li & Na) doped triphenylene and its amino-, hydroxy- and thiol-functionalized quantum dots for triggering remarkable nonlinear optical properties and ultra-deep transparency in ultraviolet region. Physica E Low Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 2021, 134, 114905. [Google Scholar]

- Hohenberg, P.; Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. 1964, 136, B864–B871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, W.; Sham, L.J. Self-Consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys. Rev. 1965, 140, A1133–A1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agwamba, E.C.; Udoikono, A.D.; Louis, H.; Mathias, G.E.; Benjamin, I.; Ikenyirimba, O.J.; Etiese, D.; Ahuekwe, E.F.; Manicum, A.-L.E. Adsorption mechanism of AsH3 pollutant on metal-functionalized coronene C24H12-X (X = Mg, Al, K) quantum dots. Chem. Phys. Impact 2023, 6, 100224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, H.; Zhour, K.; Zavartorbati, A. DFT study of Benzene, Coronene and Circumcoronene as zigzag graphene quantum dots. J. Interfaces Thin Film. Low Dimens. Syst. 2019, 3, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budyka, M.F. Semiempirical study on the absorption spectra of the coronene-like molecular models of graphene quantum dots. Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2019, 207, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R. Gaussian 16, Rev. C.01; Gaussian Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Becke, A.D. Density-functional thermochemistry. I. The effect of the exchange-only gradient correction. J. Chem. Phys. 1992, 96, 2155–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, I. Hydrated metal ions in aqueous solution: How regular are their structures? Pure Appl. Chem. 2010, 82, 1901–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Gawad, F.K.; Osman, O.; Bassem, S.M.; Nassar, H.F.; Temraz, T.A.; Elhaes, H. Spectroscopic analyses and genotoxicity of dioxins in the aquatic environment of Alexandria. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 127, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okasha, A.; Gomaa, F.; Elhaes, H.; Morsy, M.; El-Khodary, S.; Fakhry, A. Spectroscopic analyses of the photocatalytic behavior of nano titanium dioxide. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2015, 136, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerónimo, G.F.; Salazar, C.; González, V.; Salas, T. Química verde en la síntesis de rGO partiendo de la exfoliación electroquímica del grafito. Ingenierías 2019, 22, 54–65. [Google Scholar]

- Benítez, P.; Rafael de la, P. Generación de un nuevo Revestimiento Arquitectónico a Partir del Grafeno Aplicado a las Pinturas Exteriores de los Edificios. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semaan, C.; Pecastaings, G.; Schappacher, M.; Soum, A. The preparation of carbon nanotube/poly(ethylene oxide) composites using amphiphilic block copolymers. Polym. Bull. 2012, 68, 465–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, W.E. Morphology and physical properties of poly(ethylene oxide) loaded graphene nanocomposites prepared by two different techniques. Eur. Polym. J. 2011, 47, 1534–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento RF, do. Funcionalização do Grafeno por Ácidos Fosfônicos: Estudos por Primeiros Princípios. 2011. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1843/IACO-8JFQKP (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- González, Z.; Acevedo, B.; Predeanu, G.; Axinte, S.M.; Drăgoescu, M.F.; Slăvescu, V. Graphene materials from microwave-derived carbon precursors. Fuel Process. Technol. 2021, 217, 106803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Molecule | DFT Functional/Basis Set | Electronic Energy (Hartree) | Gibbs Energy (Hartree) | Enthalpy (Hartree) | Entropy (Cal/mol-Kelvin) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cr.6H2O | B3LYP/6-311+G(d,p) | −82 2.178 | −822.210 | −822.177 | 69.886 |

| B3LYP/6-31++G(d,p) | −798.982 | −799.015 | −798.981 | 69.899 | |

| M06-2X/6-311+G(d,p) | −802.841 | −802.874 | −802.840 | 69.898 | |

| Cd.6H2O | B3LYP/6-311+G(d,p) | −1269.154 | −1269.187 | −1269.153 | 70.871 |

| B3LYP/6-31++G(d,p) | −1268.983 | −1269.014 | −1269.980 | 70.812 | |

| M06-2X/6-311+G(d,p) | −1264.445 | −1264.478 | −1264.444 | 70.922 | |

| Pb.6H2O | B3LYP/6-311+G(d,p) | −461.692 | −461.727 | −461.692 | 74.608 |

| B3LYP/6-31++G(d,p) | −461.570 | −461.608 | −461.569 | 81.336 | |

| M06-2X/6-311+G(d,p) | −461.562 | −461.558 | −461.628 | 80.405 | |

| GQD | B3LYP/6-311+G(d,p) | −922.084 | −922.120 | −922.0820 | 77.340 |

| B3LYP/6-31++G(d,p) | −921.923 | −921.961 | −921.924 | 77.339 | |

| M06-2X/6-311+G(d,p) | −921.721 | −921.757 | −921.720 | 77.334 | |

| GQD-NH2 | B3LYP/6-311+G(d,p) | −977.415 | −977.453 | −977.414 | 83.357 |

| B3LYP/6-31++G(d,p) | −977.238 | −977.277 | −977.237 | 83.335 | |

| M06-2X/6-311+G(d,p) | −977.034 | −977.073 | −977.033 | 83.260 | |

| GQD-SH | B3LYP/6-311+G(d,p) | −1320.270 | −1320.311 | −1320.269 | 88.119 |

| B3LYP/6-31++G(d,p) | −1320.080 | −1320.121 | −1320.079 | 88.101 | |

| M06-2X/6-311+G(d,p) | −1319.881 | −1319.922 | −1319.880 | 87.875 |

| Structure | Interaction | Eg (eV) | TDM (D) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GQD | Cr.6H2O | 0.07453 | 3.286890 |

| Cd.6H2O | 0.04286 | 3.286890 | |

| Pb.6H2O | 0.07692 | 5.689753 | |

| GQD-NH2 | Cr.6H2O | 0.06823 | 4.252212 |

| Cd.6H2O | 0.03571 | 0.533976 | |

| Pb.6H2O | 0.02140 | 2.008093 | |

| GQD-SH | Cr.6H2O | 0.01781 | 5.231810 |

| Cd.6H2O | 0.03016 | 3.514984 | |

| Pb.6H2O | 0.02175 | 4.066719 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hernández-Fernández, J.A.; Pérez, J.S.G.; Marquez, E. Computational Study of Graphene Quantum Dots (GQDs) Functionalized with Thiol and Amino Groups for the Selective Detection of Heavy Metals in Wastewater. Molecules 2025, 30, 4661. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244661

Hernández-Fernández JA, Pérez JSG, Marquez E. Computational Study of Graphene Quantum Dots (GQDs) Functionalized with Thiol and Amino Groups for the Selective Detection of Heavy Metals in Wastewater. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4661. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244661

Chicago/Turabian StyleHernández-Fernández, Joaquín Alejandro, Juan Sebastian Gómez Pérez, and Edgar Marquez. 2025. "Computational Study of Graphene Quantum Dots (GQDs) Functionalized with Thiol and Amino Groups for the Selective Detection of Heavy Metals in Wastewater" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4661. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244661

APA StyleHernández-Fernández, J. A., Pérez, J. S. G., & Marquez, E. (2025). Computational Study of Graphene Quantum Dots (GQDs) Functionalized with Thiol and Amino Groups for the Selective Detection of Heavy Metals in Wastewater. Molecules, 30(24), 4661. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244661