Procedural Challenges in Soil Sample Preparation for Pharmaceuticals Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

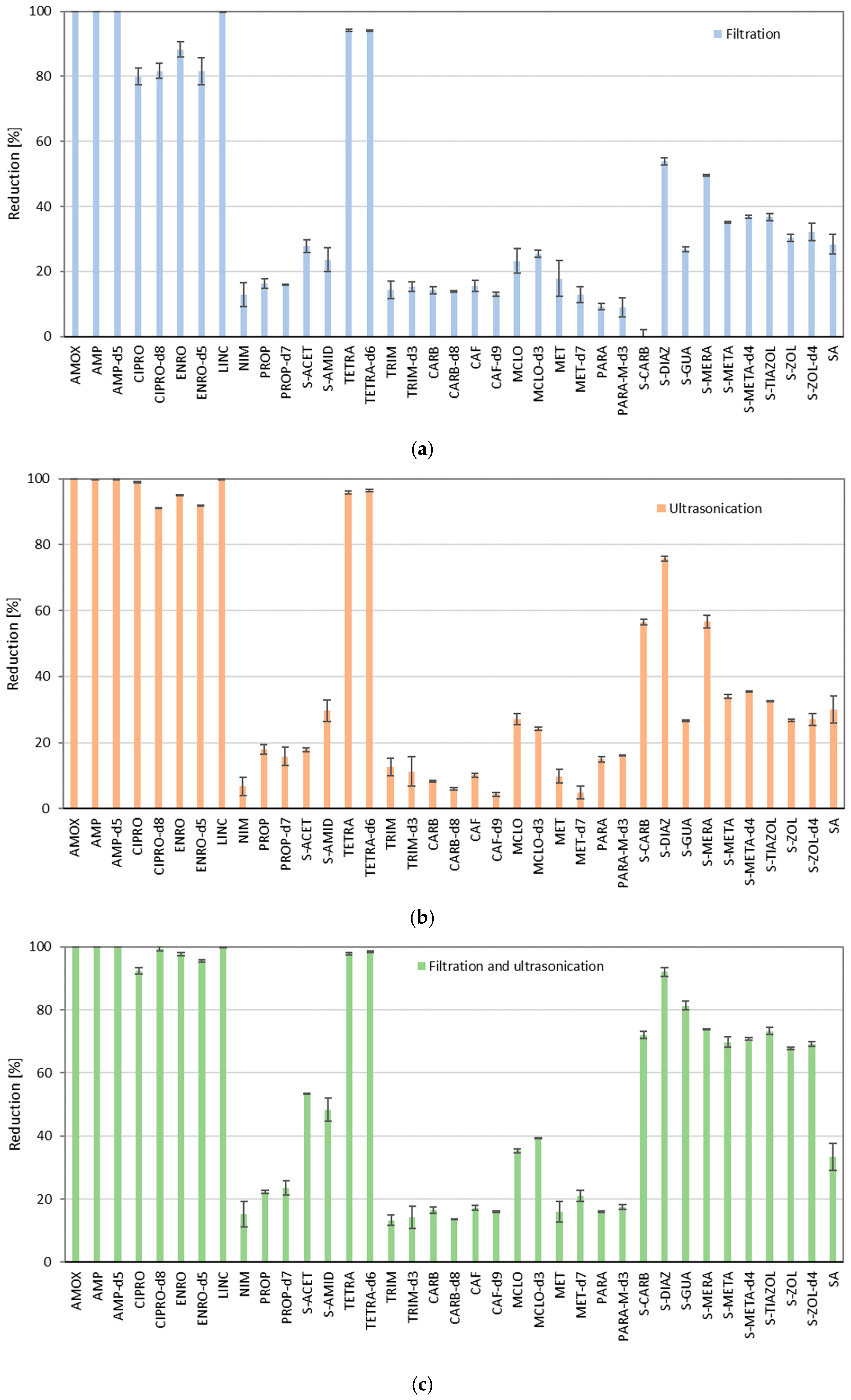

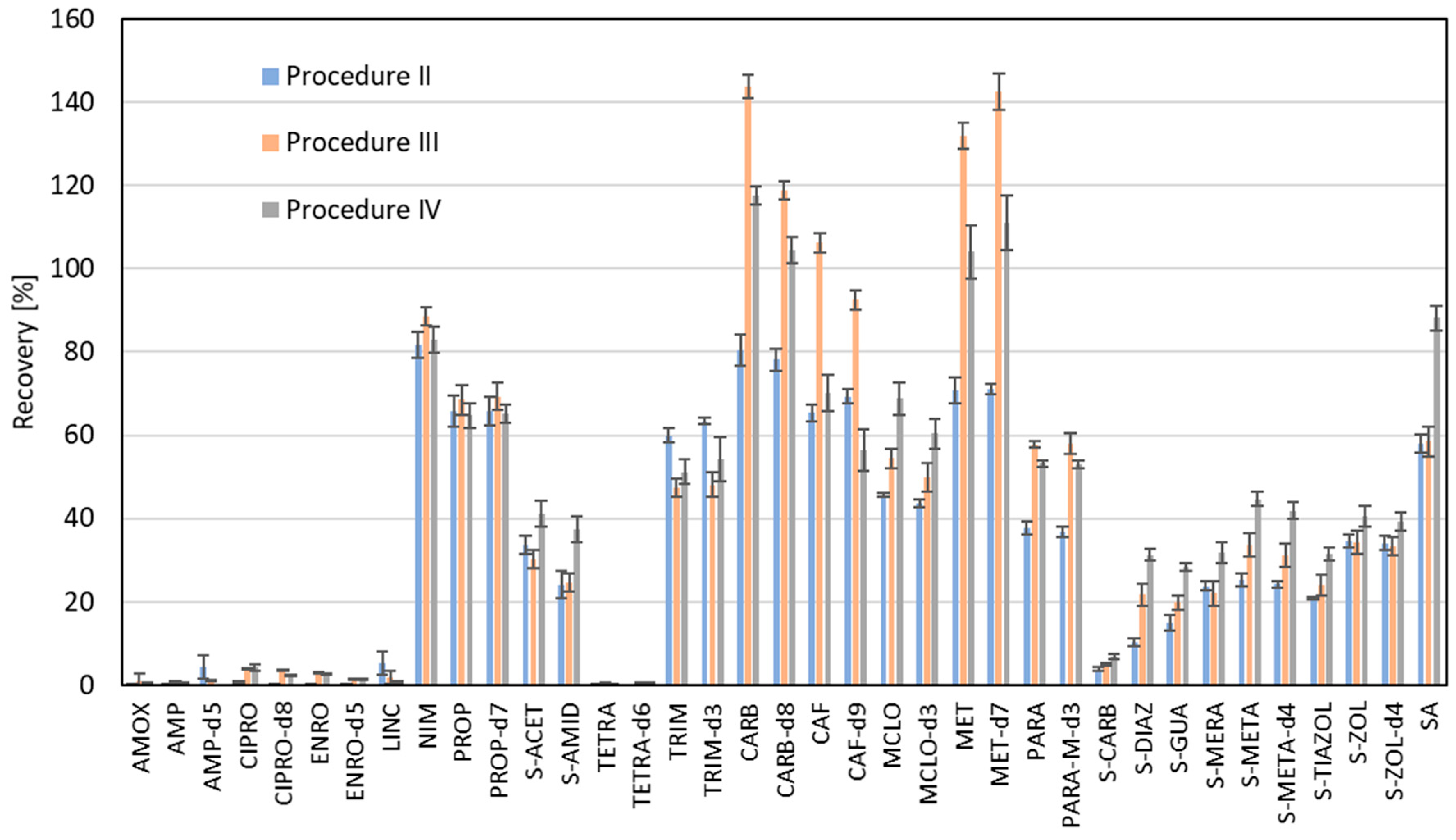

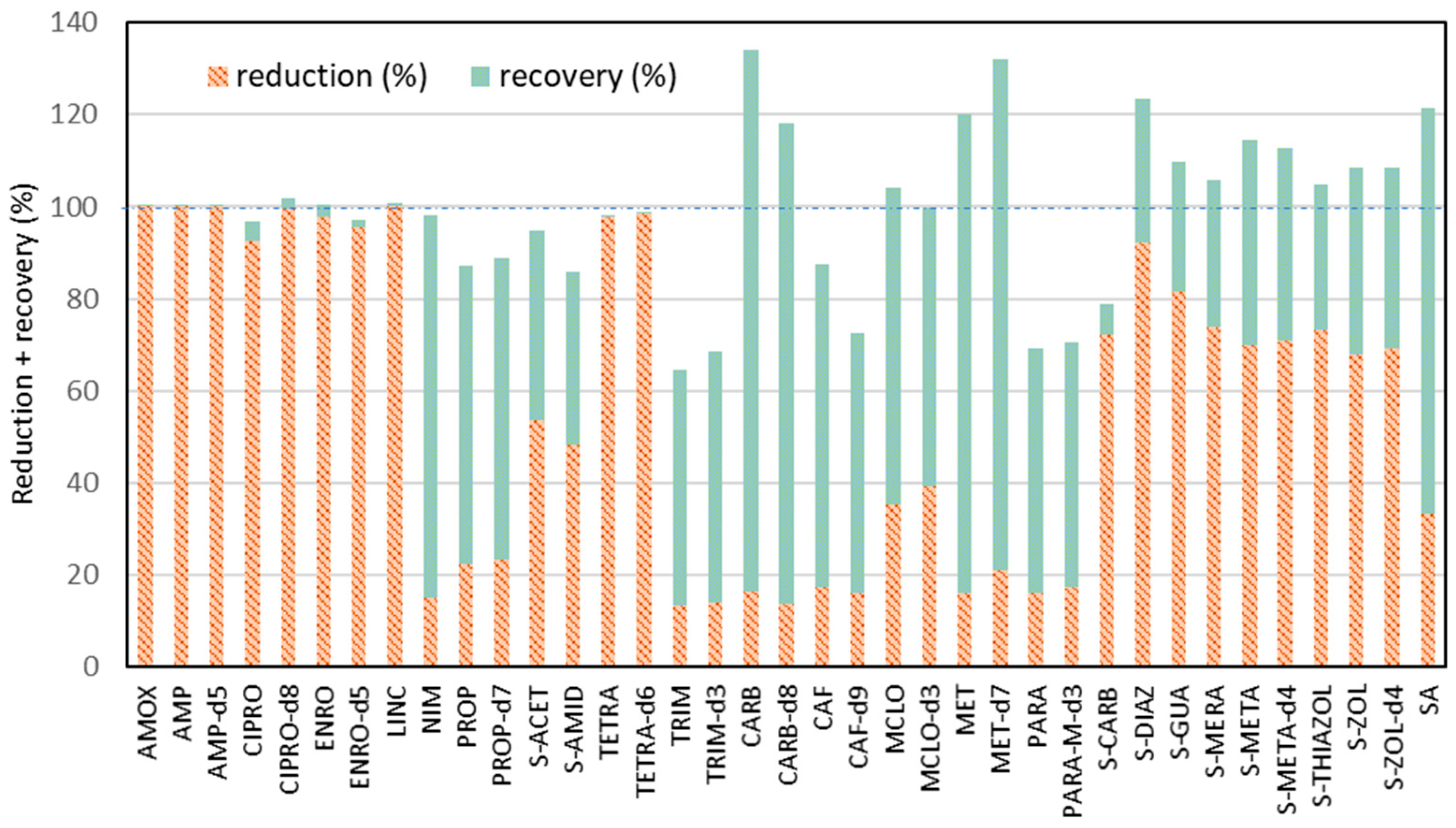

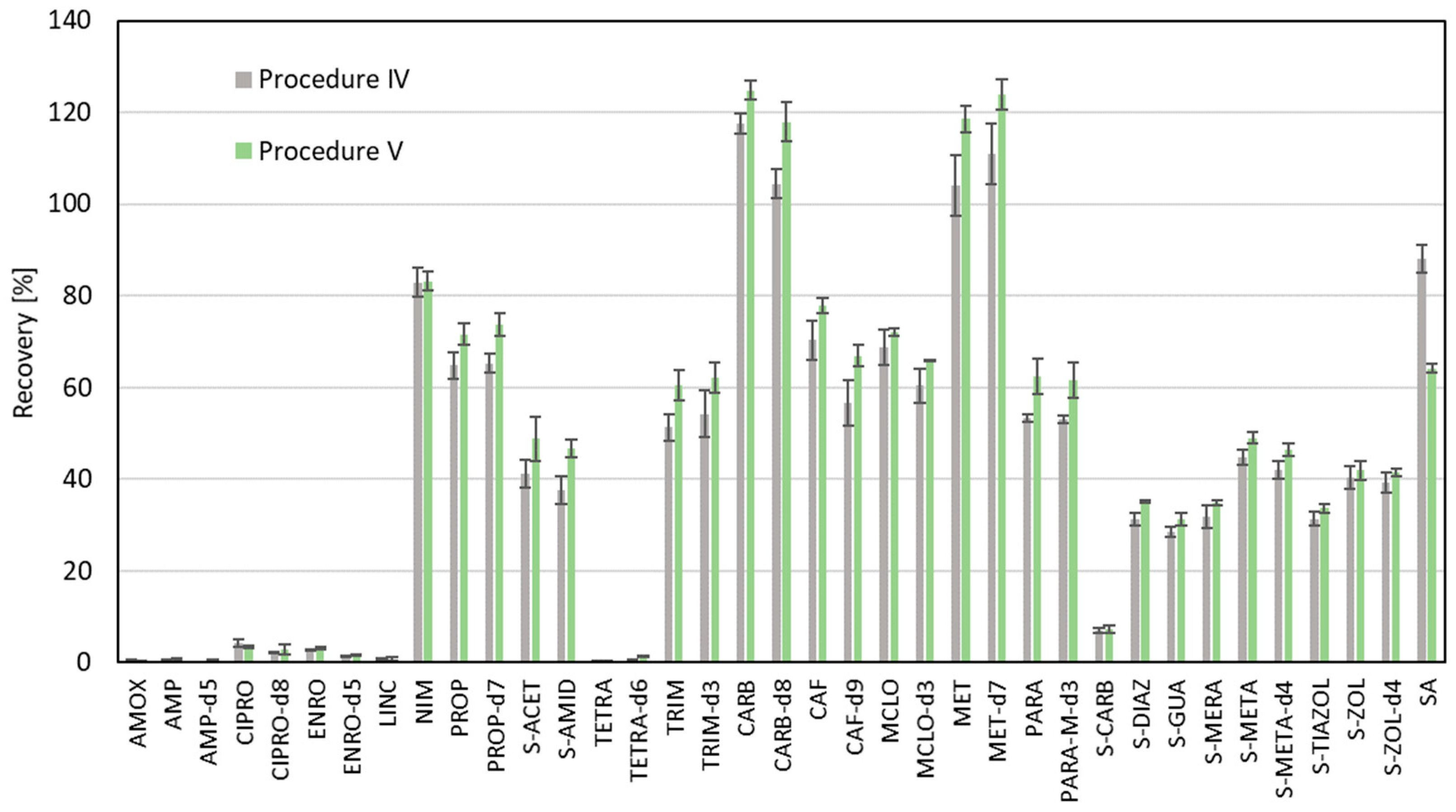

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Preparation of Standard Solutions

3.3. Extraction Methods

3.4. Tests of the Loss of Analytes in Ultrasonication and Filtration

3.5. Final Determination

3.6. Determination of Selected Pharmaceuticals in Environmental Samples

3.7. Data Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACN | acetonitrile |

| AMOX | amoxicillin |

| AMP | ampicillin |

| AMP-d5 | ampicillin-d5 |

| CAF | caffeine |

| CAF-d9 | caffeine-d9 |

| CARB | carbamazepine |

| CARB-d8 | carbamazepine-d8 |

| CIPRO | ciprofloxacin |

| CIPRO-d8 | ciprofloxacin-d8 |

| ENRO | enrofloxacin |

| ENRO-d5 | enrofloxacin-d5 |

| FA | formic acid |

| ILIS | isotopically labelled internal standards |

| IPA | isopropanol |

| LINC | lincomycin |

| LOD | limit of detection |

| LOQ | limit of quantification |

| LogP | octanol–water partition coefficient |

| LCMS/MS | Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry |

| MeOH | methanol |

| MCLO | metoclopramide |

| MCLO-d3 | metoclopramide-d3 |

| MET | metoprolol |

| MET-d7 | metoprolol-d7 |

| MRM | Multiple Reaction Monitoring |

| NIM | nimesulide |

| PARA | paracetamol |

| PARA-M-d3 | paracetamol-methyl-d3 |

| PROP | propranolol |

| PROP-d7 | propranolol-d7 |

| S-ACET | sulfacetamide |

| S-AMID | sulfanilamide |

| S-CARB | sulfacarbamide |

| S-DIAZ | sulfadiazine |

| S-GUA | sulfaguanidine |

| S-MERA | sulfamerazine |

| S-META | sulfamethazine |

| S-META-d4 | sulfamethazine-d4 |

| S-ZOL | sulfamethoxazole |

| S-ZOL-d4 | sulfamethoxazole-d4 |

| S-THIAZOL | sulfathiazole |

| SA | salicylic acid |

| TETRA | tetracycline |

| TETRA-d6 | tetracycline-d6 |

| TRIM | trimethoprim |

| TRIM-d3 | trimethoprim-d3 |

References

- Magri, C.A.; Garcia, R.G.; Binotto, E.; Burbarelli, M.F.C.; Gandra, E.R.S.; Przybulinski, B.B.; Caldara, F.R.; Komiyama, C.M. Occupational Risks and Their Implications for the Health of Poultry Farmers. Work 2021, 70, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gržinić, G.; Piotrowicz-Cieślak, A.; Klimkowicz-Pawlas, A.; Górny, R.L.; Ławniczek-Wałczyk, A.; Piechowicz, L.; Olkowska, E.; Potrykus, M.; Tankiewicz, M.; Krupka, M.; et al. Intensive Poultry Farming: A Review of the Impact on the Environment and Human Health. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 858, 160014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aouant, A.D.; Hela, D. Extraction and Analytical Techniques for Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products in Sediments: A Critical Review Towards Environmental Sustainability. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorslaer, X.; Dewulf, J.; Van Langenhove, H.; Demeestere, K. Fluoroquinolone Antibiotics: An Emerging Class of Environmental Micropollutants. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 500, 250–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gworek, B.; Kijeńska, M.; Wrzosek, J.; Graniewska, M. Pharmaceuticals in the Soil and Plant Environment: A Review. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2021, 232, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białk-Bielińska, A.; Kumirska, J.; Borecka, M.; Caban, M.; Paszkiewicz, M.; Pazdro, K.; Stepnowski, P. Selected Analytical Challenges in the Determination of Pharmaceuticals in Drinking/Marine Waters and Soil/Sediment Samples. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2016, 121, 271–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golovko, O.; Koba, O.; Kodesova, R.; Fedorova, G.; Kumar, V.; Grabic, R. Development of Fast and Robust Multiresidual LC-MS/MS Method for Determination of Pharmaceuticals in Soils. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 14068–14077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadadou, D.; Tizani, L.; Alsafar, H.; Hasan, S.W. Analytical Methods for Determining Environmental Contaminants of Concern in Water and Wastewater. MethodsX 2024, 12, 102582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, L.; Pang, S.; Zhong, M.; Sun, Y.; Qayum, A.; Liu, Y.; Rashid, A.; Xu, B.; Liang, Q.; Ma, H.; et al. A Comprehensive Review of Ultrasonic Assisted Extraction (UAE) for Bioactive Components: Principles, Advantages, Equipment, and Combined Technologies. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023, 101, 106646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiszka-Borzyszkowska, A.; Sulowska, A.; Czaja, P.; Bielicka-Giełdoń, A.; Zekker, I.; Zielińska-Jurek, A. ZnO-Decorated Green-Synthesized Multi-Doped Carbon Dots from Chlorella Pyrenoidosa for Sustainable Photocatalytic Carbamazepine Degradation. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 25529–25551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, R.A.; Albero, B. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction Methods for the Determination of Organic Contaminants in Solid and Liquid Samples. TrAC—Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 166, 117204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechlińska, A.; Gdaniec-Pietryka, M.; Wolska, L.; Namieśnik, J. Evolution of Models for Sorption of PAHs and PCBs on Geosorbents. TrAC—Trends Anal. Chem. 2009, 28, 466–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strawn, D.G.; Ghangrekar, M.M.; Chatterjee, P. Water Pollutants Classification and Its Effects on Environment. In Carbon Nanotubes for Clean Water; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- Vulava, V.M.; Cory, W.C.; Murphey, V.L.; Ulmer, C.Z. Sorption, Photodegradation, and Chemical Transformation of Naproxen and Ibuprofen in Soils and Water. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 565, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhalabi, A.M.; Meetani, M.A.; Shabib, A.; Maraqa, M.A. Sorption of Pharmaceutically Active Compounds to Soils: A Review. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2024, 36, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filep, T.; Szabó, L.; Kondor, A.C.; Jakab, G.; Szalai, Z. Evaluation of the Effect of the Intrinsic Chemical Properties of Pharmaceutically Active Compounds (PhACs) on Sorption Behaviour in Soils and Goethite. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 215, 112120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodešová, R.; Grabic, R.; Kočárek, M.; Klement, A.; Golovko, O.; Fér, M.; Nikodem, A.; Jakšík, O. Pharmaceuticals’ Sorptions Relative to Properties of Thirteen Different Soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 511, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.; Chu, L.M. Adsorption and Degradation of Five Selected Antibiotics in Agricultural Soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 545–546, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Hernández, V.; Meffe, R.; Herrera, S.; Arranz, E.; de Bustamante, I. Sorption/Desorption of Non-Hydrophobic and Ionisable Pharmaceutical and Personal Care Products from Reclaimed Water onto/from a Natural Sediment. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 472, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, F.; Zhaojun, L.; Xiaoqing, H. Impacts of Soil Organic Matter, Iron-Aluminium Oxides and PH on Adsorption-Desorption Behaviors of Oxytetracycline. Res. J. Biotechnol. 2016, 11, 121–131. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.L.; Lin, S.S.; Dai, C.M.; Shi, L.; Zhou, X.F. Sorption-Desorption and Transport of Trimethoprim and Sulfonamide Antibiotics in Agricultural Soil: Effect of Soil Type, Dissolved Organic Matter, and PH. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 5827–5835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodešová, R.; Kočárek, M.; Klement, A.; Golovko, O.; Koba, O.; Fér, M.; Nikodem, A.; Vondráčková, L.; Jakšík, O.; Grabic, R. An Analysis of the Dissipation of Pharmaceuticals under Thirteen Different Soil Conditions. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 544, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarkoti, C.; Chaturvedi, A.; Gogate, P.R.; Pandit, A.B. Degradation of Sulfamerazine Using Ultrasonic Horn and Pilot Scale US Reactor in Combination with Different Oxidation Approaches. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 312, 123351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wang, Z.; Sun, Z.; Wang, Z. Degradation of Carbamazepine from Wastewater by Ultrasound-Enhanced Zero-Valent Iron -Activated Persulfate System (US/Fe0/PS): Kinetics, Intermediates and Pathways. Environ. Technol. 2024, 45, 1760–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wu, Z.; Abramova, A.V.; Cravotto, G. Sonochemical Processes for the Degradation of Antibiotics in Aqueous Solutions: A Review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 74, 105566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Qin, Y.; Zhou, W. Degradation of Amoxicillin from Water by Ultrasound-Zero-Valent Iron Activated Sodium Persulfate. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 275, 119080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stucchi, M.; Rigamonti, M.G.; Carnevali, D.; Boffito, D.C. A Kinetic Study on the Degradation of Acetaminophen and Amoxicillin in Water by Ultrasound. ChemistrySelect 2020, 5, 14986–14992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya-Rodríguez, D.M.; Serna-Galvis, E.A.; Ferraro, F.; Torres-Palma, R.A. Degradation of the Emerging Concern Pollutant Ampicillin in Aqueous Media by Sonochemical Advanced Oxidation Processes—Parameters Effect, Removal of Antimicrobial Activity and Pollutant Treatment in Hydrolyzed Urine. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 261, 110224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wang, Z. Removal of Ciprofloxacin from Wastewater by Ultrasound/Electric Field/Sodium Persulfate (US/E/PS). Processes 2022, 10, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; He, Z.; Diaz-Rivera, D.; Pee, G.Y.; Weavers, L.K. Sonochemical Degradation of Ciprofloxacin and Ibuprofen in the Presence of Matrix Organic Compounds. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2014, 21, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturini, M.; Speltini, A.; Maraschi, F.; Profumo, A.; Pretali, L.; Fasani, E.; Albini, A. Sunlight-Induced Degradation of Soil-Adsorbed Veterinary Antimicrobials Marbofloxacin and Enrofloxacin. Chemosphere 2012, 86, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Shen, Y.; Hui, F.; Niu, Q. Degradation of Residual Lincomycin in Fermentation Dregs by Yeast Strain S9 Identified as Galactomyces Geotrichum. Ann. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 1333–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 33. Gao, Y.Q.; Gao, N.Y.; Wang, W.; Kang, S.F.; Xu, J.H.; Xiang, H.M.; Yin, D.Q. Ultrasound-Assisted Heterogeneous Activation of Persulfate by Nano Zero-Valent Iron (NZVI) for the Propranolol Degradation in Water. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018, 49, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo-Perea, A.L.; Serna-Galvis, E.A.; Lee, J.; Torres-Palma, R.A. Understanding the Effects of Mineral Water Matrix on Degradation of Several Pharmaceuticals by Ultrasound: Influence of Chemical Structure and Concentration of the Pollutants. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 73, 10550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Huang, C.; Tang, Y.; Wang, C.; Lin, S. Tetracycline Degradation by Dual-Frequency Ultrasound Combined with Peroxymonosulfate. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2024, 106, 106886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arvaniti, O.S.; Frontistis, Z.; Nika, M.C.; Aalizadeh, R.; Thomaidis, N.S.; Mantzavinos, D. Sonochemical Degradation of Trimethoprim in Water Matrices: Effect of Operating Conditions, Identification of Transformation Products and Toxicity Assessment. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020, 67, 105139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, Y.; Yang, H.; Xue, D.; Guo, Y.; Qi, F.; Ma, J. Sonolytic and Sonophotolytic Degradation of Carbamazepine: Kinetic and Mechanisms. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2016, 32, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziylan-Yavas, A.; Ince, N.H.; Ozon, E.; Arslan, E.; Aviyente, V.; Savun-Hekimoğlu, B.; Erdincler, A. Oxidative Decomposition and Mineralization of Caffeine by Advanced Oxidation Processes: The Effect of Hybridization. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 76, 105635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowjanya, P.; Shanmugasundaram, P.; Naidu, P.; Singamsetty, S.K. Novel Validated Stability-Indicating UPLC Method for the Determination of Metoclopramide and Its Degradation Impurities in API and Pharmaceutical Dosage Form. J. Pharm. Res. 2013, 6, 765–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, M.; Bartels, I.; Schmiemann, D.; Votel, L.; Hoffmann-Jacobsen, K.; Jaeger, M. Metoprolol and Its Degradation and Transformation Products Using Aops-Assessment of Aquatic Ecotoxicity Using Qsar. Molecules 2021, 26, 3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lastre-Acosta, A.M.; Cruz-González, G.; Nuevas-Paz, L.; Jáuregui-Haza, U.J.; Teixeira, A.C.S.C. Ultrasonic Degradation of Sulfadiazine in Aqueous Solutions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 918–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayati, F.; Isari, A.A.; Anvaripour, B.; Fattahi, M.; Kakavandi, B. Ultrasound-Assisted Photocatalytic Degradation of Sulfadiazine Using MgO@CNT Heterojunction Composite: Effective Factors, Pathway and Biodegradability Studies. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 381, 122636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.Q.; Gao, N.Y.; Deng, Y.; Gu, J.S.; Gu, Y.L.; Zhang, D. Factors Affecting Sonolytic Degradation of Sulfamethazine in Water. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2013, 20, 1401–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Yang, Y.; Li, X.; Yu, H.; Wang, N.; Li, H.; Du, P.; Jiang, Y.; Fan, X.; Zhou, Z. Degradation of Sulfamethazine by Persulfate Activated with Nanosized Zero-Valent Copper in Combination with Ultrasonic Irradiation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020, 239, 116537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.Q.; Yin, R.L.; Zhou, X.J.; Du, J.S.; Cao, H.O.; Yang, S.S.; Ren, N.Q. Sulfamethoxazole Degradation by Ultrasound/Ozone Oxidation Process in Water: Kinetics, Mechanisms, and Pathways. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2015, 22, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arslan, E.; Hekimoglu, B.S.; Cinar, S.A.; Ince, N.; Aviyente, V. Hydroxyl Radical-Mediated Degradation of Salicylic Acid and Methyl Paraben: An Experimental and Computational Approach to Assess the Reaction Mechanisms. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 33125–33134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauletto, P.S.; Lütke, S.F.; Dotto, G.L.; Salau, N.P.G. Adsorption Mechanisms of Single and Simultaneous Removal of Pharmaceutical Compounds onto Activated Carbon: Isotherm and Thermodynamic Modeling. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 336, 116203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Evseenko, V.I.; Khvostov, M.V.; Borisov, S.A.; Tolstikova, T.G.; Polyakov, N.E.; Dushkin, A.V.; Xu, W.; Min, L.; Su, W. Solubility, Permeability, Anti-Inflammatory Action and in Vivo Pharmacokinetic Properties of Several Mechanochemically Obtained Pharmaceutical Solid Dispersions of Nimesulide. Molecules 2021, 26, 1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, Z.; Lou, X.; Fang, C.; Wang, P.; Wu, G.; Guan, J. Insights into Antimicrobial Agent Sulfacetamide Transformation during Chlorination Disinfection Process in Aquaculture Water. RSC Adv. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Dong, F.; Mei, X.; Ning, J.; She, D. Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards and Grouping Scheme for Determination of Neonicotinoid Insecticides and Their Metabolites in Fruits, Vegetables and Cereals – A Compensation of Matrix Effects. Food Chem. 2020, 311, 125871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mülow-Stollin, U.; Lehnik-Habrink, P.; Kluge, S.; Bremser, W.; Piechotta, C. Efficiency Evaluation of Extraction Methods for Analysis of OCPs and PCBs in Soils of Varying TOC. J. Environ. Prot. 2017, 8, 693–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, J.; Barrón, D.; Jiménez-Lozano, E.; Sanz-Nebot, V. Comparison between Capillary Electrophoresis, Liquid Chromatography, Potentiometric and Spectrophotometric Techniques for Evaluation of PKa Values of Zwitterionic Drugs in Acetonitrile-Water Mixtures. Anal. Chim. Acta 2001, 437, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiva Noor Rachmayani. Available online: https://www.chemicalbook.com/ChemicalProductProperty_IN_CB3711796.htm (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Available online: https://www.chemeo.com/cid/12-308-6/Sulfaguanidine (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Available online: https://go.drugbank.com/drugs/DB13726 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Lin, K.; Gan, J. Chemosphere Sorption and Degradation of Wastewater-Associated Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs and Antibiotics in Soils. Chemosphere 2011, 83, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, A.Y.; Lin, C.; Tung, H.; Chary, N.S. Potential for Biodegradation and Sorption of Acetaminophen, Caffeine, Propranolol and Acebutolol in Lab-Scale Aqueous Environments. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 183, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, G.; Eadsforth, C.; Bossuyt, B.; Bouvy, A.; Enrici, M.H.; Geurts, M.; Kotthoff, M.; Michie, E.; Miller, D.; Müller, J.; et al. A Comparison of Log K Ow (n-Octanol–Water Partition Coefficient) Values for Non-Ionic, Anionic, Cationic and Amphoteric Surfactants Determined Using Predictions and Experimental Methods. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2019, 31, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, T.G.; Zhou, C.; Øiestad, E.L.; Hegstad, S.; Trones, R.; Pedersen-Bjergaard, S. Conductive Vial Electromembrane Extraction of Opioids from Oral Fluid. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2023, 415, 5323–5335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Dong, F.; Xu, J.; Liu, X.; Chen, Z.; Liu, N.; Chen, X.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, Y. Simultaneous Determination of Chlorantraniliprole and Cyantraniliprole in Fruits, Vegetables and Cereals Using Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry with the Isotope-Labelled Internal Standard Method. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015, 407, 4111–4120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamscher, G.; Sczesny, S.; Höper, H.; Nau, H. Determination of Persistent Tetracycline Residues in Soil Fertilized with Liquid Manure by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Electrospray Ionization Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2002, 74, 1509–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuchiyama, T.; Katsuhara, M.; Nakajima, M. Compensation of Matrix Effects in Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry Analysis of Pesticides Using a Combination of Matrix Matching and Multiple Isotopically Labeled Internal Standards. J. Chromatogr. A 2017, 1524, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. Analytical Quality Control and Method Validation for Pesticide Residues Analysis in Food and Feed (SANTE/12682/2019); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Harron, D.W.G. Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use: The ICH Process. Textb. Pharm. Med. 2013, 1994, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Information about Lincomycine from Sigma Aldrich. Available online: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/PL/pl/product/sigma/l6004?srsltid=AfmBOoogB_UQAzx4ad641ztp-anbT3AaXaDqk0tlCszsNJDFzPjy_d (accessed on 30 October 2025).

| Analyzed Compound | Recovery Factor | LOD [ng g−1] | LOQ [ng g−1] | CF1 ± SD [ng g−1] | CF2 ± SD [ng g−1] | CA ± SD [ng g−1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMOX | 1.18 | 2.4 | 7.1 | <LOD | <LOQ | 138 ± 49 |

| AMP | 0.89 | 1.9 | 5.8 | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ |

| CIPRO | 0.86 | 2.7 | 8.0 | 14.5 ± 3.6 | 12.5 ± 7.2 | <LOQ |

| ENRO | 0.93 | 2.0 | 6.1 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| LINC | 1.75 | 1.3 | 3.8 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| NIM | 0.74 | 0.26 | 0.78 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| PROP | 0.86 | 0.12 | 0.35 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| S-ACET | 1.31 | 0.31 | 0.93 | 3.57 ± 1.32 | <LOD | <LOD |

| S-AMID | 1.31 | 2.4 | 7.3 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| TETRA | 2.27 | 4.0 | 12 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| TRIM | 1.03 | 0.35 | 1.0 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| CARB | 0.94 | 0.28 | 0.84 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| CAF | 0.86 | 0.94 | 2.8 | 4.29 ± 1.31 | <LOD | <LOD |

| MCLO | 0.91 | 0.26 | 0.77 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| MET | 1.05 | 0.62 | 1.8 | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ |

| PARA | 1.06 | 0.47 | 1.4 | 16.6 ± 3.3 | <LOD | <LOD |

| S-CARB | 6.46 | 2.2 | 6.7 | <LOD | <LOQ | <LOD |

| S-DIAZ | 1.32 | 0.52 | 1.6 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| S-GUA | 1.48 | 0.88 | 2.6 | <LOD | <LOQ | <LOD |

| S-MERA | 1.34 | 0.38 | 1.2 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| S-META | 0.95 | 0.48 | 1.4 | <LOQ | <LOQ | <LOQ |

| S-TIAZOL | 1.23 | 0.28 | 0.85 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| S-ZOL | 0.99 | 0.27 | 0.82 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| SA | 1.86 | 6.2 | 19 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fiszka Borzyszkowska, A.; Olkowska, E.; Wolska, L. Procedural Challenges in Soil Sample Preparation for Pharmaceuticals Analysis. Molecules 2025, 30, 4660. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234660

Fiszka Borzyszkowska A, Olkowska E, Wolska L. Procedural Challenges in Soil Sample Preparation for Pharmaceuticals Analysis. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4660. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234660

Chicago/Turabian StyleFiszka Borzyszkowska, Agnieszka, Ewa Olkowska, and Lidia Wolska. 2025. "Procedural Challenges in Soil Sample Preparation for Pharmaceuticals Analysis" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4660. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234660

APA StyleFiszka Borzyszkowska, A., Olkowska, E., & Wolska, L. (2025). Procedural Challenges in Soil Sample Preparation for Pharmaceuticals Analysis. Molecules, 30(23), 4660. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234660