Cytotoxic and Antimicrobial Activity of the Ageratina Genus

Abstract

1. Introduction

Ethnobotany

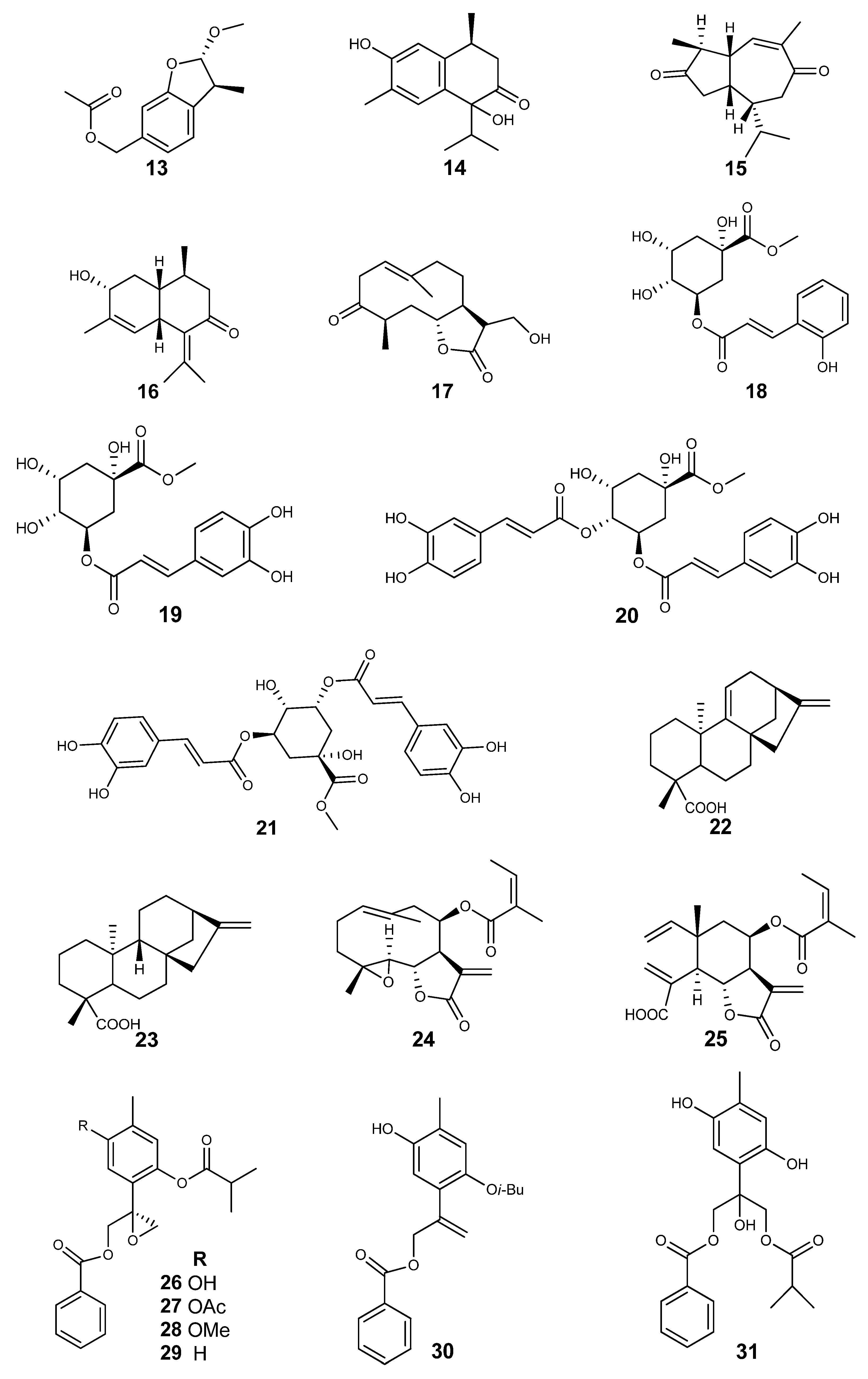

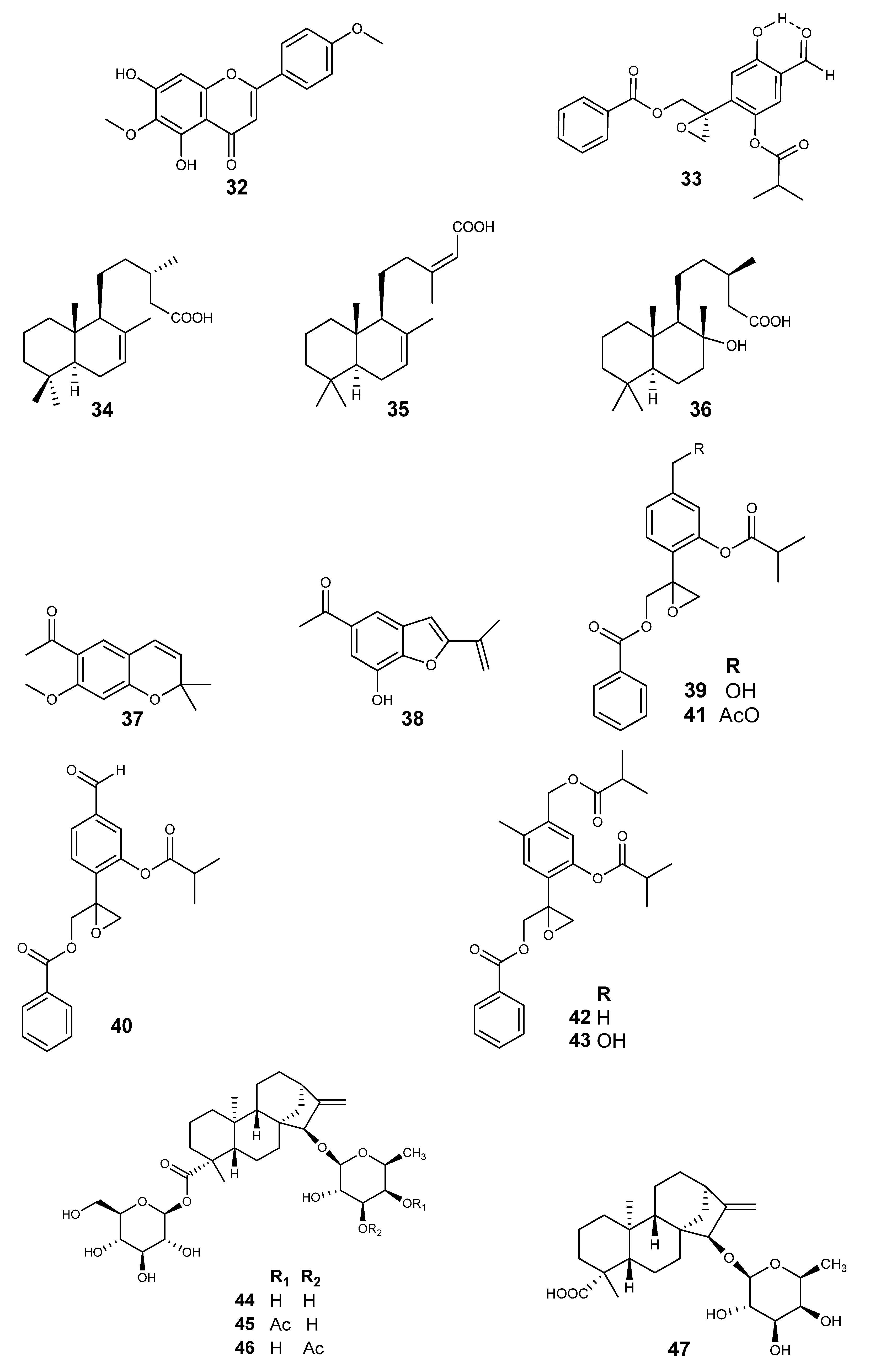

2. Results

3. Discussion

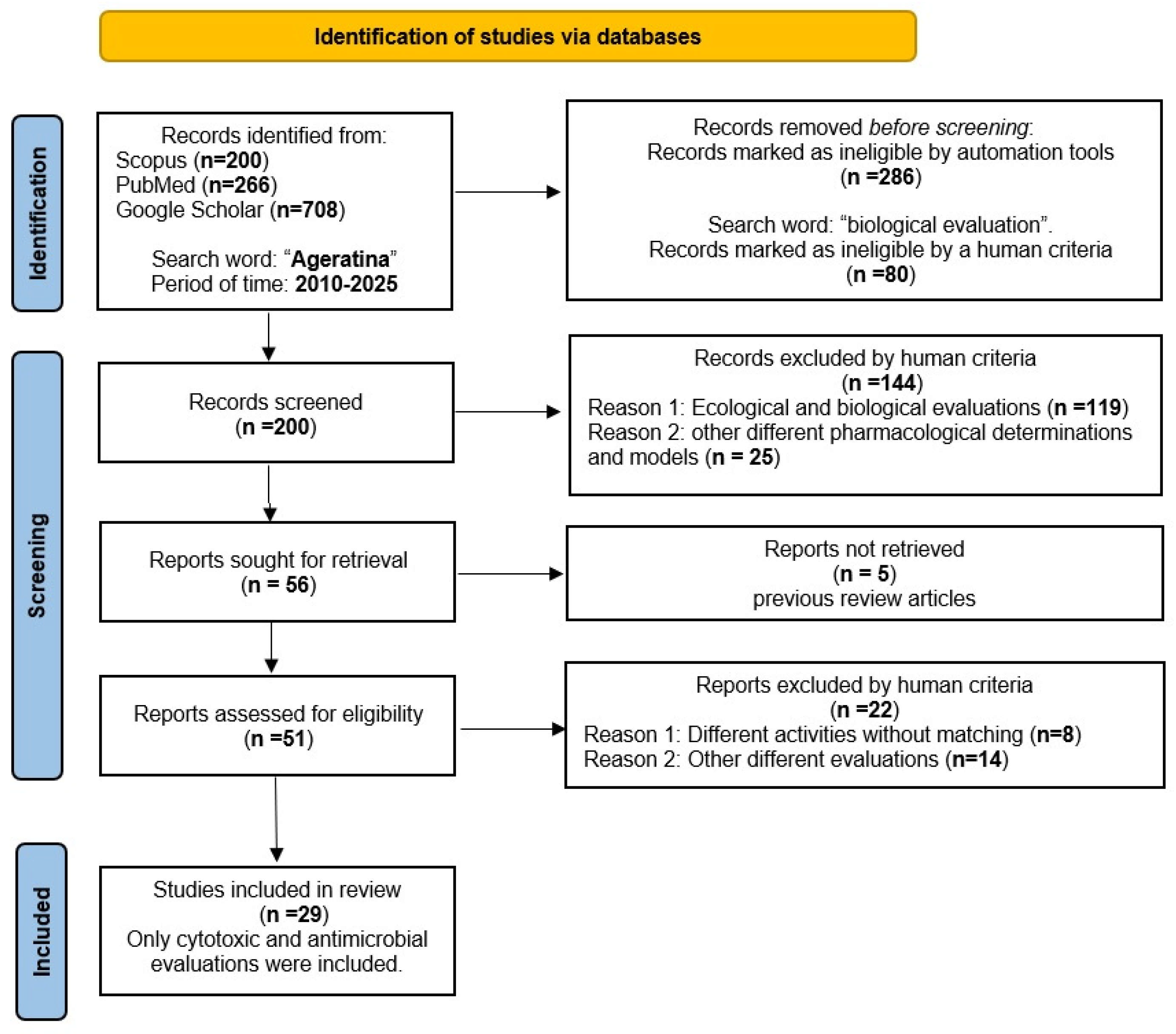

4. Materials and Methods

5. Future Perspectives

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| A549 | Lung cancer |

| AP | Aerial parts |

| ATTC | American Type Culture Collection |

| BioMod | Biological model |

| Bax | Bcl-2-associated X protein |

| Bcl-2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| CCL | Cancer cell line |

| CC50 | 50% Cytotoxic Concentration |

| Caco-2 | Colon cancer |

| Calu-1 | Epidermoid carcinoma of the lung |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| DCM | Dichloromethane |

| Df | Diffusion |

| Df disc | Diffusion disc |

| DIZ | Diameter of Inhibitory Zone |

| EC50 | 50% Effective Concentration |

| EtOAc | Ethyl acetate |

| EO-Hdest | Essential oil by Hydro distillation |

| EO | Essential Oil |

| F | Flowers |

| FS | Flowering stage |

| IC50 | Fifth inhibitory concentration |

| H-EtOAc | Hexane-Ethyl acetate |

| HCT-116 | Adherent cell of colon cancer |

| HCT-15 | Colorectal carcinoma |

| HeLa | Cervical carcinoma |

| HepG2 | Hepatocarcinoma |

| HT29 | Colorectal adenocarcinoma |

| HL-60 | Promyelocytic leukaemia |

| HSV-1 | Herpes simplex virus type 1 |

| HSV-2 | Herpes simplex virus type 1 |

| I | Inflorescence |

| IC50 | Half-maximal Inhibitory Concentration |

| KB | Epithelial carcinoma |

| L | Leaves |

| LC50 | Fifth Lethal Concentration; |

| L&F | Leaves and flowers |

| L&S | Leaves and stems |

| m | Meters |

| MIC | Minimal inhibitory concentration |

| MBC | Minimal bactericide concentration |

| MDA-MB-231 | Human breast cancer |

| MCF-7 | Breast cancer |

| MRSA | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| MTT | 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5 diphenyl tetrazolium bromide |

| MTS | 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-H-tetrazolium |

| MTT/PMS | Tetrazolium salt/phenazine methosulfate |

| μd | microdilution |

| NA | Nitazoxanide assay |

| NK-kB | Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| OVCAR | Ovarian adenocarcinoma |

| PC-3 | Prostatic adenocarcinoma |

| PP/ES | Part of the plant/extraction solvent |

| R | Root(s) |

| S | Stems |

| SiHa | Uterine squamous cell carcinoma |

| SCA | Suspension cell assay |

| SMMC-7721 | uman hepatocellular carcinoma |

| SW480 | Human colon carcinoma |

| 4T1 | Breast cancer |

| U-937 | Histiocytic lymphoma |

| UISO | Merkel carcinoma cell |

| VIICE | Virus inhibition induced cytopathic effect |

| VS | Vaginal suppositories |

| VSt | Vegetative stage |

| Vero | kidney-derived epithelial cell |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Bukowski, K.; Kciuk, M.; Kontek, R. Mechanisms of multidrug resistance in cancer chemotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, P.; Malhotra, J.; Kulkarni, P.; Horne, D.; Salgia, R.; Singhal, S.S. Emerging therapeutic strategies to overcome drug resistance in cancer cells. Cancers 2024, 16, 2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bizuayehu, H.M.; Ahmed, K.Y.; Kibret, G.D.; Dadi, A.F.; Belachew, S.A.; Bagade, T.; Tegegne, T.K.; Venchiarutti, R.L.; Kibret, K.T.; Hailegebireal, A.H.; et al. Global disparities of cancer and its projected burden in 2050. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2443198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F. Planning for tomorrow: Global cancer incidence and the role of prevention 2020–2070. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 18, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Noncommunicable Diseases Progress Monitor 2025; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240105775 (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Oliveira, M.; Antunes, W.; Mota, S.; Madureira-Carvalho, Á.; Dinis-Oliveira, R.J.; Dias da Silva, D. An overview of the recent advances in antimicrobial resistance. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban-Chmiel, R.; Marek, A.; Stępień-Pyśniak, D.; Wieczorek, K.; Dec, M.; Nowaczek, A.; Osek, J. Antibiotic resistance in bacteria—A review. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarland, R.C.; Peralta-Gómez, S.; Sánchez-Morales, C.; Parra-Bustamante, F.; Villa-Hernández, J.M.; de León-Sánchez, F.D.; Pérez-Flores, L.J.; Rivera-Cabrera, F.; Mendoza-Espinoza, J.A. A pharmacological and phytochemical study of medicinal plants used in Mexican folk medicine. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2015, 14, 550–557. [Google Scholar]

- Pirintsos, S.; Panagiotopoulos, A.; Bariotakis, M.; Daskalakis, V.; Lionis, C.; Sourvinos, G.; Karakasiliotis, I.; Kampa, M.; Castanas, E. From traditional ethnopharmacology to modern natural drug discovery: A methodology discussion and specific examples. Molecules 2022, 27, 4060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R.M.; Robinson, H.E. The genera of the Eupatorieae (Asteraceae). In Monographs in Systematic Botany from the Missouri Botanical Garden; Missouri Botanical Garden: St. Louis, MO, USA, 1987; pp. 1–581. [Google Scholar]

- Royal Botanic Gardens. Ageratina . Available online: https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:30003158-2 (accessed on 29 September 2022).

- Clewell, A.F.; Wooten, J.W. A revision of Ageratina (Compositae: Eupatorieae) from eastern North America. Brittonia 1971, 23, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Peng, P.; Wang, G.; Zhao, G.; Zhou, Y.; Tang, Z. Mapping the Distribution and Dispersal Risks of the Alien Invasive Plant Ageratina adenophora in China. Diversity 2022, 14, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, X.; Zhao, H.; Wang, R.; Zhang, H.; Chen, B.; Huang, H.; Liu, W.; Wan, F. Predicting the potential geographical distribution of Ageratina adenophora in China using equilibrium occurrence data and ensemble model. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 973371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Choi, J.; Song, W. Introduction and Spread of the Invasive Alien Species Ageratina altissima in a Disturbed Forest Ecosystem. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, A.G.; Enríquez, M.I.A.; González, J.B.C.; Miranda, D.M.V.; Bahena, C.Y.M.; Moreno, J.M.P. Plantas útiles de los patios de Santo Domingo, Ocotitlán, Tepoztlán, Morelos, México [Useful Plants of the Playgrounds of Santo Domingo, Ocotitlán, Tepoztlán, Morelos, México]. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosyst. 2020, 23, 50. [Google Scholar]

- Monroy, C.; Castillo, P. Plantas Medicinales Utilizadas en el Estado de Morelos; Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos: Cuernavaca, Mexico, 2000; pp. 23–24. [Google Scholar]

- Crompton, H.; Burke, D. Artificial intelligence in higher education: The state of the field. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2023, 20, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiwaree, S.; Pongpaibul, Y.; Thammasit, P. Anti-dermatophyte activity of the aqueous extracts of Thai medicinal plants. Braz. J. Biol. 2022, 82, e254291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manandhar, S.; Luitel, S.; Dahal, R.K. In vitro antimicrobial activity of some medicinal plants against human pathogenic bacteria. J. Trop. Med. 2019, 2019, 1895340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanu, K.D.; Sharma, N.; Kshetrimayum, V.; Chaudhary, S.K.; Ghosh, S.; Haldar, P.K.; Mukherjee, P.K. Ageratina adenophora (Spreng.) King & H. Rob. Standardized leaf extract as an antidiabetic agent for type 2 diabetes: An in vitro and in vivo evaluation. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1178904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, S.; Natesan, K.; Shivaji, K.; Balasubramanian, M.G.; Ponnusamy, P. Cytotoxic effect induced apoptosis in lung cancer cell line on Ageratina adenophora leaf extract. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019, 22, 101381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, R.; Catarro, J.; Freitas, D.; Pacheco, R.; Oliveira, M.C.; Serralheiro, M.L.; Falé, P.L. Action of euptox A from Ageratina adenophora juice on human cell lines: A top-down study using FTIR spectroscopy and protein profiling. Toxicol. Vitr. 2019, 57, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, W.X.; Zheng, M.F.; Xu, Q.L.; Wan, F.H.; Wang, J.; Lei, T.; Zhou, Z.Y.; Tan, J.W. Bioactive quinic acid derivatives from Ageratina adenophora. Molecules 2013, 18, 14096–14104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Luo, S.; Li, S.; Hua, J.; Li, W.; Li, S. Specialized metabolites from Ageratina adenophora and their inhibitory activities against pathogenic fungi. Phytochemistry 2018, 148, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.H.; Gu, W.J.; Zhang, E.B.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.H.; Yang, Y.X.; Geng, H. Three new cadinene-type sesquiterpenoids from the aerial parts of Ageratina adenophora. Nat. Prod. Res. 2023, 39, 2320–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, L.M.; Zhang, M.; Xu, Q.L.; Zhang, Q.; Luo, B.; Luo, Q.W.; Liu, W.B.; Tan, J.W. Two new thymol derivatives from the roots of Ageratina adenophora. Molecules 2017, 22, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, B.; Dong, L.M.; Xu, Q.L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, W.B.; Tan, J.W. A new monoterpene and a new sesquiterpene from the roots of Ageratina adenophora. Phytochem. Lett. 2018, 24, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustos-Brito, C.; Sanchez-Castellanos, M.; Esquivel, B.; Calderon, J.S.; Calzada, F.; Yepez-Mulia, L.; Hernández-Barragán, A.; Joseph-Nathan, P.; Cuevas, G.; Quijano, L. Structure, absolute configuration, and antidiarrheal activity of a thymol derivative from Ageratina cylindrica. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustos-Brito, C.; Sánchez-Castellanos, M.; Esquivel, B.; Calderón, J.; Calzada, F.; Yépez-Muilia, L.; Joseph-Nathan, P.; Cuevas, G.; Quijano, L. ent-Kaurene Glycosides from Ageratina cylindrica. J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 78, 2580–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustos-Brito, C.; Esquivel, B.; Calzada, F.; Yepez-Mulia, L.; Calderón, J.S.; Porras-Ramirez, J.; Quijano, L. Further thymol derivatives from Ageratina cylindrica. Chem. Biodivers. 2016, 13, 1281–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arciniegas, A.; Pérez-Castorena, A.L.; Meléndez-Aguirre, M.; Ávila, J.G.; García-Bores, A.M.; Villaseñor, J.L.; Romo de Vivar, A. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of Ageratina deltoidea. Chem. Biodivers. 2018, 15, e1700529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valarezo, E.; Jaramillo-Jaramillo, E.; Carrión-Campoverde, A.; Morocho, V.; Jaramillo-Fierro, X.; Cartuche, L.; Meneses, M.A. A Study of the Essential Oil Isolated from Ageratina dendroides (Spreng.) RM King & H. Rob.: Chemical Composition, Enantiomeric Distribution, and Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, and Anticholinesterase Activities. Plants 2023, 12, 2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiroa, J.L.; Triana, J.; Pérez, F.J.; Castillo, Q.A.; Brouard, I.; Quintana, J.; Estévez, F.; León, F. Secondary metabolites from two Hispaniola Ageratina species and their cytotoxic activity. Med. Chem. Res. 2018, 7, 1792–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustos-Brito, C.; Vázquez-Heredia, V.J.; Calzada, F.; Yépez-Mulia, L.; Calderón, J.S.; Hernández-Ortega, S.; Esquivel, B.; García-Hernández, N.; Quijano, L. Antidiarrheal thymol derivatives from Ageratina glabrata. Structure and absolute configuration of 10-benzoyloxy-8, 9-epoxy-6-hydroxythymol isobutyrate. Molecules 2016, 21, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Méndez-Callejas, G.; Rodríguez-Mayusa, J.; Riveros-Quiroga, M.; Mahete-Pinilla, K.; Torrenegra-Guerrero, R. Antiproliferative activity of chloroformic fractions from leaves and inflorescences of Ageratina gracilis. Emir. J. Food Agric. 2017, 29, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Barrio, G.S.I.; García, T.; Roque, A.; Álvarez, A.L.; Calderón, J.S.; Parra, F. Antiviral activity of Ageratina havanensis and major chemical compounds from the most active fraction. Braz. J. Pharmacogn. 2011, 21, 915–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, T.H.; Da Rocha, C.Q.; Dias, M.J.; Pino, L.L.; Del Barrio, G.; Roque, A.; Pérez, C.E.; dos Santos, L.C.; Spengler, I.; Vilegas, W. Comparison of the qualitative chemical composition of extracts from Ageratina havanensis collected in two different phenological stages by FIA-ESI-IT-MSn and UPLC/ESI-MSn: Antiviral activity. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2017, 12, 1934578X1701200110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, T.H.; Rocha, C.Q.D.; Delgado-Roche, L.; Rodeiro, I.; Ávila, Y.; Hernández, I.; Cuellar, C.; Lopes, M.T.P.; Vilegas, W.; Auriemma, G.; et al. Influence of the phenological state of in the antioxidant potential and chemical composition of Ageratina havanensis. effects on the p-glycoprotein function. Molecules 2020, 25, 2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Barajas, L.; Rojas-Vera, J.; Morales-Méndez, A.; Rojas-Fermín, L.; Lucena, M.; Buitrago, A. Chemical composition and evaluation of antibacterial activity of essential oils of Ageratina jahnii and Ageratina pichinchensis collected in Mérida, Venezuela. Bol. Latinoam. Caribe Plantas Med. Aromát. 2013, 12, 92–98. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Sanchez, E.; Ramírez-López, C.B.; Talavera-Alemán, A.; Leon-Hernandez, A.; Martinez-Munoz, R.E.; Martínez-Pacheco, M.M.; Gómez-Hurtado, M.A.; Cerda-García-Rojas, C.M.; Joseph-Nathan, P.; del Río, R.E. Absolute configuration of (13 R)-and (13 S)-labdane diterpenes coexisting in Ageratina jocotepecana. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 1005–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Gallardo, K.; Quintero-Rincón, P.; Stashenko, E.E.; Olivero-Verbel, J. Chemical composition and in vitro bioactivities of hydroalcoholic extracts from Turnera pumilea, Hyptis lantanifolia, and Ageratina popayanensis cultivated in Colombia. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Cerecero, O.; Islas-Garduño, A.L.; Zamilpa, A.; Tortoriello, J. Effectiveness of Ageratina pichinchensis Extract in Patients with Vulvovaginal Candidiasis. A Randomized, Double-Blind, and Controlled Pilot Study. Phytother. Res. 2017, 31, 885–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Cerecero, O.; Zamilpa-Álvarez, A.; Ramos-Mora, A.; Alonso-Cortés, D.; Jiménez-Ferrer, J.E.; Huerta-Reyes, M.E.; Tortoriello, J. Effect on the wound healing process and in vitro cell proliferation by the medicinal Mexican plant Ageratina pichinchensis. Planta Medica 2011, 77, 979–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solís-Quispe, L.; Pino, J.A.; Falco, A.S.; Tomaylla-Cruz, C.; Quispe-Tonccochi, E.G.; Solís-Quispe, J.A.; Aragón-Alencastre, L.J.; Solís-Quispe, A. Chemical composition and antibacterial activities of essential oil from Ageratina pentlandiana (DC.) RM King, H. Rob. leaves grown in the Peruvian Andes. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2019, 31, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Hormaza, L.; Mora, C.; Alvarez, R.; Alzate, F.; Osorio, E. Chemical composition and antibacterial activity against Enterobacter cloacae of essential oils from Asteraceae species growing in the Páramos of Colombia. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 77, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, J.S.; Suta-Velásquez, M.; Mateus, J.; Pardo-Rodriguez, D.; Puerta, C.J.; Cuéllar, A.; Robles, J.; Cuervo, C. Preliminary chemical characterization of ethanolic extracts from Colombian plants with promising anti-Trypanosoma cruzi activity. Exp. Parasitol. 2021, 223, 108079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso-Castro, A.J.; Villarreal, M.L.; Salazar-Olivo, L.A.; Gomez-Sanchez, M.; Dominguez, F.; Garcia-Carranca, A. Mexican medicinal plants used for cancer treatment: Pharmacological, phytochemical and ethnobotanical studies. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 133, 945–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suffness, M.; Pezzuto, J.M. Assays related to cancer drug discovery. In Methods in Plant Biochemistry: Assays for Bioactivity; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990; Volume 6, pp. 71–133. [Google Scholar]

- Canga, I.; Vita, P.; Oliveira, A.I.; Castro, M.Á.; Pinho, C. In vitro cytotoxic activity of African plants: A review. Molecules 2022, 27, 4989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrouni, I.A.; Elachouri, M. Anticancer medicinal plants used by Moroccan people: Ethnobotanical, preclinical, phytochemical and clinical evidence. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 266, 113435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, R.S.; Seif El-Din, A.A.; Abu-Serie, M.; Abd El Rahman, N.M.; El-Demellawy, M.; Metwally, A.M. Investigation of In-Vitro Cytotoxic and Potential Anticancer Activities of Flavonoidal Aglycones from Egyptian Propolis. Rec. Pharm. Biomed. Sci. 2017, 2, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, X.; Liu, H. Sesquiterpene lactones and cancer: New insight into antitumor and anti-inflammatory effects of parthenolide-derived Dimethylaminomicheliolide and Micheliolide. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1551115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-Y.; Rajabi, S.; Hamzeloo-Moghadam, M.; Kumar, A.; Maresca, M.; Ghildiyal, P. Sesquiterpene lactones as emerging biomolecules to cease cancer by targeting apoptosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1371002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monasterio, A.; Urdaci, M.C.; Pinchuk, I.V.; Lopez-Moratalla, N.; Martinez-Irujo, J.J. Flavonoids induce apoptosis in human leukemia U937 cells through caspase-and caspase-calpain-dependent pathways. Nutr. Cancer 2004, 50, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopustinskiene, D.M.; Jakstas, V.; Savickas, A.; Bernatoniene, J. Flavonoids as anticancer agents. Nutrients 2020, 12, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Xia, L. Plant-derived natural products and combination therapy in liver cancer. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1116532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajabi, S.; Maresca, M.; Yumashev, A.V.; Choopani, R.; Hajimehdipoor, H. The most competent plant-derived natural products for targeting apoptosis in cancer therapy. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montané, X.; Kowalczyk, O.; Reig-Vano, B.; Bajek, A.; Roszkowski, K.; Tomczyk, R.; Pawliszak, W.; Giamberini, M.; Mocek-Płóciniak, A.; Tylkowski, B. Current perspectives of the applications of polyphenols and flavonoids in cancer therapy. Molecules 2020, 25, 3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamas-Din, A.; Kale, J.; Leber, B.; Andrews, D.W. Mechanisms of action of Bcl-2 family proteins. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a008714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C.; Chen, J.W.; Shen, L.S.; Chen, S.; Chen, G.Q. Research advances in natural sesquiterpene lactones: Overcoming cancer drug resistance through modulation of key signalling pathways. Cancer Drug Resist. 2025, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Chu, C.; Qin, J.J.; Guan, X. Research progress on antitumor mechanisms and molecular targets of Inula sesquiterpene lactones. Chin. Med. 2023, 18, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, A.; Islam, A.U.; Prakash, H.; Singh, S. Phytochemicals targeting NF-κB signalling: Potential anti-cancer interventions. J. Pharm. Anal. 2022, 12, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoub, I.M.; El-Shazly, M.; Lu, M.C.; Singab, A.N.B. Antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities of the crude extracts of Dietes bicolor leaves, flowers and rhizomes. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2014, 95, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Liufang, H.; Shah, S.M.; Ali, F.; Khan, S.A.; Shah, F.A.; Li, J.B.; Li, S. Cytotoxic effects of extracts and isolated compounds from Ifloga spicata (forssk.) sch. bip against HepG-2 cancer cell line: Supported by ADMET analysis and molecular docking. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 986456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serwecińska, L. Antimicrobials and antibiotic-resistant bacteria: A risk to the environment and to public health. Water 2020, 12, 3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulos, B.; Bisrat, D.; Yeshak, M.Y.; Asres, K. Natural Products with Potent Antimycobacterial Activity (2000–2024): A Review. Molecules 2025, 30, 3708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Pastor, R.; Carrera-Pacheco, S.E.; Zúñiga-Miranda, J.; Rodríguez-Pólit, C.; Mayorga-Ramos, A.; Guamán, L.P.; Barba-Ostria, C. Current Landscape of Methods to Evaluate Antimicrobial Activity of Natural Extracts. Molecules 2023, 28, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalska-Krochmal, B.; Dudek-Wicher, R. The minimum inhibitory concentration of antibiotics: Methods, interpretation, clinical relevance. Pathogens 2021, 10, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, L.; YanChun, H.; Lei, W.; Hui, T.; Quan, M.; Biao, L.; YaJun, H.; JunLiang, D.; YaHui, W. Antitumor activity in vitro by 9-oxo-10, 11-dehydroageraphorone extracted from Eupatorium adenophorum. Asian J. Chem. 2014, 26, 7321–7323. [Google Scholar]

- Heena; Kaushal, S.; Kaur, V.; Panwar, H.; Sharma, P.; Jangra, R. Isolation of quinic acid from dropped Citrus reticulata Blanco fruits: Its derivatization, antibacterial potential, docking studies, and ADMET profiling. Front. Chem. 2024, 12, 1372560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Yi, G.; Li, M.; Liao, L.; Yang, C.; Cho, C.; Zhang, B.; Zhu, J.; Zou, K.; et al. Quinic acid: A potential antibiofilm agent against clinical resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Chin. Med. 2021, 16, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercan, L.; Doğru, M. Antioxidant and antimicrobial capacity of quinic acid. Bitlis Eren Üniv. Fen Bilim. Derg. 2022, 11, 1018–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, S.; Sotondoshe, N.; Aderibigbe, B.A. Carvacrol and Thymol Hybrids: Potential Anticancer and Antibacterial Therapeutics. Molecules 2024, 29, 2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.T.; Khan, M.; Ahmad, J.; Wahab, R.; Abd-Elkader, O.H.; Musarrat, J.; Al-Kedhairy, A.A. Thymol and carvacrol induce autolysis, stress, growth inhibition and reduce the biofilm formation by Streptococcus mutans. AMB Express 2017, 7, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintanilla-Licea, R.; Mata-Cárdenas, B.D.; Vargas-Villarreal, J.; Bazaldúa-Rodríguez, A.F.; Ángeles-Hernández, I.K.; Garza-González, J.N.; Hernández-García, M.E. Antiprotozoal activity against Entamoeba histolytica of plants used in northeast Mexican traditional medicine. Bioactive compounds from Lippia graveolens and Ruta chalepensis. Molecules 2014, 19, 21044–21065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranasinghe, S.; Armson, A.; Lymbery, A.J.; Zahedi, A.; Ash, A. Medicinal plants as a source of antiparasitics: An overview of experimental studies. Pathog. Glob. Health 2023, 117, 535–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, F.; Ayaz, M.; Sadiq, A.; Ullah, F.; Hussain, I.; Shahid, M.; Yessimbekov, Z.; Adhikari-Devkota, A.; Devkota, H.P. Potential role of plant extracts and phytochemicals against foodborne pathogens. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noites, A.; Borges, I.; Araújo, B.; da Silva, J.C.E.; de Oliveira, N.M.; Machado, J.; Pinto, E. Antimicrobial activity of some medicinal herbs to the treatment of cutaneous and mucocutaneous infections: Preliminary research. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Saadony, M.T.; Saad, A.M.; Mohammed, D.M.; Korma, S.A.; Alshahrani, M.Y.; Ahmed, A.E.; Ibrahim, E.H.; Salem, H.M.; Alkafaas, S.S.; Saif, A.M.; et al. Medicinal plants: Bioactive compounds, biological activities, combating multidrug-resistant microorganisms, and human health benefits—A comprehensive review. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1491777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaou, N.; Stavropoulou, E.; Voidarou, C.; Tsigalou, C.; Bezirtzoglou, E. Towards Advances in Medicinal Plant Antimicrobial Activity: A Review Study on Challenges and Future Perspectives. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Flores, J.G.; Garcia-Curiel, L.; Perez-Escalante, E.; Contreras-Lopez, E.; Aguilar-Lira, G.Y.; Angel-Jijon, C.; Gonzalez-Olivares, L.G.; Baena-Santillan, E.S.; Ocampo-Salinas, I.O.; Guerrero-Solano, J.A.; et al. Plant Antimicrobial Compounds and Their Mechanisms of Action on Spoilage and Pathogenic Bacteria: A Bibliometric Study and Literature Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Castro, A.J.; Domínguez, F.; Maldonado-Miranda, J.J.; Castillo-Pérez, L.J.; Carranza-Álvarez, C.; Solano, E.; Isiordia-Espinoza, M.A.; Juárez-Vázquez, M.d.C.; Zapata-Morales, J.R.; Argueta-Fuertes, M.A.; et al. Use of medicinal plants by health professionals in Mexico. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 198, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoridis, S.; Drakou, E.G.; Hickler, T.; Thines, M.; Nogues-Bravo, D. Evaluating natural medicinal resources and their exposure to global change. Lancet Planet. Health 2023, 7, e155–e163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangra, K.; Kakkar, S.; Mittal, V.; Kumar, V.; Aggarwal, N.; Chopra, H.; Malik, T.; Garg, V. Incredible use of plant-derived bioactives as anticancer agents. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 1721–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porras, G.; Chassagne, F.; Lyles, J.T.; Marquez, L.; Dettweiler, M.; Salam, A.M.; Samarakoon, T.; Shabih, S.; Farrokhi, D.R.; Quave, C.L. Ethnobotany and the role of plant natural products in antibiotic drug discovery. Chem. Rev. 2020, 121, 3495–3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradeep Prabhu, P.; Mohanty, B.; Lobo, C.L.; Balusamy, S.R.; Shetty, A.; Perumalsamy, H.; Mahadev, M.; Mijakovic, I.; Dubey, A.; Singh, P. Harnessing the nutriceutics in early-stage breast cancer: Mechanisms, combinational therapy, and drug delivery. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K.; Gupta, J.K.; Chanchal, D.K.; Shinde, M.G.; Kumar, S.; Jain, D.; Almarhoon, Z.M.; Alshahrani, A.M.; Calina, D.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; et al. Natural products as drug leads: Exploring their potential in drug discovery and development. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2025, 398, 4673–4687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.; Amin, A.; Akhtar, M.S.; Zaman, W. Micro-and Nanoengineered Devices for Rapid Chemotaxonomic Profiling of Medicinal Plants. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happy, K.; Ban, Y.; Mudondo, J.; Haniffadli, A.; Gang, R.; Choi, K.O.; Rahmat, E.; Okello, D.; Komakech, R.; Kang, Y. SMART-HERBALOMICS: An Innovative Multi-Omics Approach to Studying Medicinal Plants Grown in Controlled Systems such as Phytotrons. Phytomedicine 2025, 148, 157303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ydyrys, A.; Nurtayeva, M.; Yerkebayeva, M. Advancing Medicinal Plant Research with Artificial Intelligence: Key Applications and Benefits. Nat. Resour. Hum. Health 2025, 5, 740–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriyaamporn, P.; Pamornpathomkul, B.; Patrojanasophon, P.; Ngawhirunpat, T.; Rojanarata, T.; Opanasopit, P. The artificial intelligence-powered new era in pharmaceutical research and development: A review. AAPS PharmSciTech 2024, 25, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, M.; Abid, A.; Aziz, T.; Saleem, A.; Hanif, N.; Ali, I.; Alasmari, A.F. Comparative toxicity assessment of fisetin-aided artificial intelligence-assisted drug design targeting epibulbar dermoid through phytochemicals. Open Chem. 2024, 22, 20230197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Collection Place | Part of the Plant | Extract Solvent | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. adenophora | Thailand | L | Ethanol | [19] |

| Nepal | AP | Methanol | [20] | |

| India | L | Hydroalcoholic | [21] | |

| India | L | Methanol | [22] | |

| Portugal | L | Aqueous | [23] | |

| China | AP | Ethanol | [24] | |

| China | R | Methanol | [25] | |

| China | R | Ethanol | [26,27,28] | |

| A. cylindrica | México | L | DCM | [29] |

| México | L | Aqueous | [30] | |

| México | L | Petrol | [31] | |

| A. deltoidea | Mexico | AP | Hexane | [32] |

| A.dendroides | Ecuador | L&F | EO-Hdest | [33] |

| A. dictyoneura | Dominican Republic | AP | Ethanol | [34] |

| A. glabrata | Mexico | L | DCM | [35] |

| A.gracilis | Colombia | I | Ethanol | [36] |

| Colombia | I | Petrol | ||

| Colombia | L | Ethanol | ||

| Colombia | L | Petrol | ||

| A.havanensis | Cuba | L | Ethanol | [37] |

| Cuba | L | EtOAc | ||

| Cuba | L | n-butanol | ||

| Cuba | S | Ethanol | ||

| Cuba | S | EtOAc | ||

| Cuba | S | n-butanol | ||

| Cuba | S | Ethanol | ||

| Cuba | L&F | EtOAc | [38] | |

| Cuba | L&F | n-butanol | ||

| Cuba | L (FS) | Ethanol | [39] | |

| Cuba | L (FS) | EtOAc | ||

| Cuba | L (FS) | n-butanol | ||

| Cuba | S (FS) | Ethanol | ||

| Cuba | S (FS) | EtOAc | ||

| Cuba | S (FS) | n-butanol | ||

| Cuba | F (FS) | Ethanol | ||

| Cuba | F (FS) | EtOAc | ||

| Cuba | F (FS) | n-butanol | ||

| A. illita | Dominican Republic | AP | Ethanol | [34] |

| A.janni | Venezuela | L | EO-Hdest | [40] |

| A. jocotepecana | Mexico | F | Hexane | [41] |

| Mexico | L | |||

| A.popayanensis | Colombia | AP | Hydroalcoholic | [42] |

| A.pichinchensis | Mexico | AP | (7:3) H-EtOAc | [43] |

| Mexico | AP | Aqueous | [44] | |

| Mexico | AP | (7:3) H-EtOAc | ||

| Venezuela | L | EO-Hdest | [40] | |

| A.pentlandiana | Peru | L | EO-Hdest | [45] |

| A. tinifolia | Colombia | AP | EO-Hdest | [46] |

| A.vacciniaefolia | Colombia | L | Ethanol | [47] |

| Specie | PP/ES | CCL | Result IC50 (μg/mL) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. adenophora | L/Hydroalcoholic | HCT-116 | 65.65 ± 2.1 | [21] |

| L/Methanol | A549 | 50.08 ± 0.14 | [22] | |

| L/Aqueous | HeLa | 950 ± 0.07 | [23] | |

| Caco-2 | 289 ± 0.12 | |||

| MCF-7 | 302 ± 0.16 | |||

| A. havanensis (FS) | L/Ethanol | 4T1 | 381.6 ± 7.5 | [39] |

| L/EtOAc | 252.5 ± 10.1 | |||

| L/n-butanol | 302.0 ± 8.0 | |||

| S/Ethanol | 228.2 ± 8.7 | |||

| F/Ethanol | 263.5 ± 8.2 | |||

| F/EtOAc | 259.5 ± 10.6 | |||

| F/n-butanol | 315.5 ± 9.9 | |||

| A. havanensis (VSt) | L/Ethanol | 4T1 | 392.8 ± 6.7 | |

| L/EtOAc | 313.0 ± 12.1 | |||

| L/n-butanol | 496.5 ± 6.7 | |||

| S/Ethanol | 355.7 ± 7.6 | |||

| A. gracilis | I/Ethanol | SiHa | 41.14 ± 1.02 | [36] |

| HT29 | 62.33 ± 1.24 | |||

| A549 | 74.56 ± 0.95 | |||

| MDA-MB-231 | 62.81 ± 0.37 | |||

| PC-3 | 77.35 ± 1.06 | |||

| I/Petrol | SiHa | 21.19 ± 1.25 | ||

| HT29 | 12.67 ± 1.13 | |||

| A549 | 38.50 ± 1.18 | |||

| MDA-MB-231 | 26.94 ± 1.05 | |||

| PC-3 | 52.65 ± 0.64 | |||

| L/Ethanol | SiHa | 71.98 ± 1.53 | ||

| HT29 | 53.05 ± 0.82 | |||

| A549 | 116.96 ± 1.04 | |||

| MDA-MB-231 | 58.44 ± 0.78 | |||

| PC-3 | 72.46 ± 0.47 | |||

| L/Petrol | SiHa | 12.91 ± 0.92 | ||

| HT29 | 11.20 ± 1.20 | |||

| A549 | 34.80 ± 1.15 | |||

| MDA-MB-231 | 14.72 ± 0.69 | |||

| PC-3 | 29.85 ± 1.27 | |||

| A. pichinchensis | L&S/Aqueous | KB | ≥20 | [44] |

| HCT-15 | ≥20 | |||

| UISO | ≥20 | |||

| OVCAR | ≥20 | |||

| L&S/(7:3) H-EtOAc | KB | ≥20 | ||

| HCT-15 | ≥20 | |||

| UISO | ≥20 | |||

| OVCAR | ≥20 | |||

| A. popayanensis | AP/Hydroalcoholic | Calu-1 | 444 | [42] |

| HepG2 | 387 | |||

| A. havanensis | L/Ethanol | Vero | CC50 (µg/mL) 2834 ± 448 | [37] |

| L/EtOAc | Vero | 1670 ± 0.2 | ||

| L/n-butanol | Vero | 404.9 ± 43.5 | ||

| S/Ethanol | Vero | 5685 ± 117 | ||

| S/EtOAc | Vero | 2270 ± 99.9 | ||

| S/n-butanol | Vero | 457.4 ± 28.1 | ||

| L&F/EtOAc | Vero | 1242.8 ± 37.2 | [38] |

| Specie | Compounds | BioMod | CCL | Result IC50 μM | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. adenophora | New tricyclic cadinene (1) | MTS | HL-60 | 24.06 ± 2.21 | [26] |

| A549 | 11.45 ± 0.69 | ||||

| SMMC-7721 | 9.96 ± 1.45 | ||||

| MDA-MB-231 | 16.35 ± 3.32 | ||||

| SW480 | 28.75 ± 3.93 | ||||

| (+)-(5R,7S,9R,10S)-2-oxocadinan-3,6(11)-dien-12,7-olide (2) | HL-60 | 35.73 ± 1.51 | |||

| A549 | 9.85 ± 0.88 | ||||

| SMMC-7721 | 13.44 ± 2.32 | ||||

| MDA-MB-231 | 12.72 ± 1.58 | ||||

| SW480 | 26.03 ± 2.91 | ||||

| Cadinene norsesquiterpenoid (3) | HL-60 | 42.85 ± 1.35 | |||

| A549 | 21.82 ± 0.65 | ||||

| SMMC-7721 | 10.28 ± 1.67 | ||||

| MDA-MB-231 | 30.42 ± 2.24 | ||||

| SW480 | 23.65 ± 1.49 | ||||

| 9-oxo-10,11-dehydro-ageraphorone (Euptox A) (4) | HeLa | (mg/mL) 0.55 ± 0.05 | [23] | ||

| Caco-2 | 1.43 ± 0.08 | ||||

| MCF-7 | 1.63 ± 0.08 | ||||

| 7,9-diisobutyryloxy-8-ethoxythymol (5) | MTT | A549 | IC50 (μM) >100 | [27] | |

| HeLa | >100 | ||||

| HepG2 | >100 | ||||

| 7-acetoxy-8-methoxy-9-isobutyryloxythymol (6) | A549 | >100 | |||

| HeLa | >100 | ||||

| HepG2 | >100 | ||||

| 7,9-diisobutyryloxy-8-methoxythymol (7) | A549 | >100 | |||

| HeLa | >100 | ||||

| HepG2 | >100 | ||||

| 9-oxoageraphorone (8) | A549 | >100 | |||

| HeLa | >100 | ||||

| HepG2 | >100 | ||||

| (−)-isochaminic acid (9) | A549 | 32.37 ± 3.75 | |||

| HeLa | 25.64 ± 2.34 | ||||

| HepG2 | 41.87 ± 6.53 | ||||

| (1α,6α)-10-hydroxy-3-carene-2-one (10) | A549 | 30.65 ± 3.87 | |||

| HeLa | 18.36 ± 1.72 | ||||

| HepG2 | 39.44 ± 3.61 | ||||

| A. dictyoneura | Quercetin 3,7-dimethylether (11) | U-937 | 7.0 ± 0.5 | [34] | |

| A. illita | (8R)-8-hydroxy-β-cyclocostunolide (12) | 6.0 ± 0.7 |

| Specie | PP/ES | Method | Microorganism | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. adenophora | AP/Methanol | μd | MRSA | MIC (mg/mL) 125 | [20] |

| S. aureus | 25 | ||||

| AP/EO | μd | E. coli | MIC (μg/mL) >4000 | [33] | |

| P. aeruginosa | >4000 | ||||

| E. faecium | >4000 | ||||

| E. faecalis | >4000 | ||||

| S. aureus | >4000 | ||||

| AP/EO | μd | S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Thypimurium | >4000 | ||

| A. janni | L/EO | Df disc | S. aureus | MIC (mg/mL) 49.5 | [40] |

| E. faecalis | 49.5 | ||||

| A.pentlandiana | L/EO | μd | S. aureus | MIC (μL/mL) 11.9 + 0.1 | [45] |

| B. subtilis | 22.7 ± 0.3 | ||||

| E. coli | 57.7 ± 0.1 | ||||

| S. thyphimurium | 41.6 ± 0.1 | ||||

| MBC | S. aureus | 11.9 + 0.1 | |||

| B. subtilis | 22.7 ± 0.1 | ||||

| E. coli | 64.8 ± 0.3 | ||||

| S. thyphimurium | 50.0 ± 0.2 | ||||

| A. pichinchensis | L/EO | Df disc | S. aureus | MIC (mg/mL) 104 | [40] |

| E. faecalis | 104 | ||||

| A.tinifolia | AP/EO | μd | E. cloacae clinical sample | >5 | [46] |

| E. cloacae ATCC | >5 | ||||

| A. havanensis | L/Ethanol | SCA | HSV-1 | EC50 (μg/mL) 809.9 ± 59.6 | [37] |

| HSV-2 | 1050 ± 42.9 | ||||

| L/EtOAc | HSV-1 | 311.6 ± 10.1 | |||

| HSV-2 | >450 | ||||

| L/n-butanol | HSV-1 | >225 | |||

| HSV-2 | 128.1 ± 22.8 | ||||

| S/Ethanol | HSV-1 | >450 | |||

| HSV-2 | 2614 ± 158 | ||||

| S/EtOAc | HSV-1 | >450 | |||

| HSV-2 | >450 | ||||

| S/n-butanol | HSV-1 | 240.9 ± 5.7 | |||

| HSV-2 | 145.4 ± 22.1 | ||||

| L&F/EtOAc | VIICE | HSV-1 | 463.4 ± 12.5 | [38] | |

| HSV-2 | >200 | ||||

| A. adenophora | L/Ethanol | Df | T. mentagrophytes | MIC (mg/mL) 0.04 | [19] |

| T. rubrum | <0.0025 | ||||

| A. dendroides | AP/EO | μd | A. niger | MIC (μg/mL) >4000 | [33] |

| AP/EO | μd | C. albicans | >4000 | ||

| A. pichinchensis | AP/(7:3) H-EtOAc | VS | C. albicans | Decrease % 81.2 | [43] |

| A. vacciniaefolia | L/Ethanol | MTT | T. cruzi | EC50 (μg/mL) 256 | [47] |

| Specie | Compounds | Method | Microorganism Assay | Result MIC (µg/mL) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. adenophora | 2α-methoxyl-3β-methyl-6-(acetyl-O-methyl)-2,3-dihydrobenzofuran (13) | μd | S. aureus | 25 | [28] |

| B. cereus | 50 | ||||

| B. subtilis | 25 | ||||

| E. coli | >100 | ||||

| 1,6-dihydroxy-1-isopropyl-4,7-dimethyl-3,4-dihydronaphthalen-2(1H)-one (14) | S. aureus | >100 | |||

| B. cereus | >100 | ||||

| B. subtilis | >100 | ||||

| E. coli | >100 | ||||

| Eupatorenone (15) | S. aureus | 12.5 | |||

| B. cereus | 25 | ||||

| B. subtilis | 25 | ||||

| E. coli | >100 | ||||

| 3-hydroxymuurola-4,7(11)-dien-8-one (16) | S. aureus | 25 | |||

| B. cereus | 12.5 | ||||

| B. subtilis | 25 | ||||

| E. coli | >100 | ||||

| 9-oxoageraphorone (8) | S. aureus | >100 | |||

| B. cereus | >100 | ||||

| B. subtilis | >100 | ||||

| E. coli | >100 | ||||

| (4R,5S)-4-hydroxy-5-isopropyl-2-methyl-2-cyclohexehone (17) | S. aureus | >100 | |||

| B. cereus | >100 | ||||

| B. subtilis | >100 | ||||

| E. coli | >100 | ||||

| 7,9-diisobutyryloxy-8-ethoxythymol (5) | μd | S. aureus | >200 | [27] | |

| B. thuringiensis | >200 | ||||

| B. subtilis | 125 | ||||

| E. coli | >200 | ||||

| S. dysenteriae | >200 | ||||

| 7-acetoxy-8-methoxy-9-isobutyryloxythymol (6) | S. aureus | 125 | |||

| B. thuringiensis | 62.5 | ||||

| B. subtilis | 62.5 | ||||

| E. coli | >200 | ||||

| S. dysenteriae | >200 | ||||

| 7,9-di-isobutyryloxy-8-methoxythymol (7) | S. aureus | >200 | |||

| B. thuringiensis | 125 | ||||

| B. subtilis | 125 | ||||

| E. coli | >200 | ||||

| E. dysenteriae | >200 | ||||

| 9-oxoageraphorone (8) | S. aureus | >200 | |||

| B. thuringiensis | >200 | ||||

| B. subtilis | >200 | ||||

| E. coli | >200 | ||||

| S. dysenteriae | >200 | ||||

| (−)-isochaminic acid (9) | S. aureus | 31.3 | |||

| B. thuringiensis | 31.3 | ||||

| B. subtilis | 15.6 | ||||

| E. coli | 62.5 | ||||

| S. dysenteriae | 62.5 | ||||

| (1α,6α)-10-hydroxy-3-carene-2-one (10) | S. aureus | 15.6 | |||

| B. thuringiensis | 31.3 | ||||

| B. subtilis | 15.6 | ||||

| E. coli | 62.5 | ||||

| S. dysenteriae | 62.5 | ||||

| 5-O-trans-o-coumaroylquinic acid methyl ester (18) | μd | S. aureus | MIC (µM) 88.8 | [24] | |

| B. thuringiensis | 88.8 | ||||

| E. coli | 88.8 | ||||

| S. enterica | 88.8 | ||||

| S. dysenteriae | 177.6 | ||||

| Chlorogenic acid methyl ester (19) | S. aureus | 84.8 | |||

| B. thuringiensis | 84.8 | ||||

| E. coli | 84.8 | ||||

| S. enterica | 84.8 | ||||

| S. dysenteriae | 169.8 | ||||

| Macranthoin F (20) | S. aureus | 29.4 | |||

| B. thuringiensis | 59.0 | ||||

| E. coli | 59.0 | ||||

| S. enterica | 14.7 | ||||

| S. dysenteriae | 117.9 | ||||

| Macranthoin G (21) | S. aureus | 59.0 | |||

| B. thuringiensis | 59.0 | ||||

| E. coli | 59.0 | ||||

| S. enterica | 7.4 | ||||

| S. dysenteriae | 117.9 | ||||

| A. deltoidea | Grandiflorenic acid (22) | μd | S. aureus | MIC (µg/mL) 31 | [32] |

| Kaurenoic acid (23) | S. aureus | 31 | |||

| Deltoidin A (24) | E. coli | 16 | |||

| 8β-angeloyloxyelemacronquistianthus acid (25) | S. aureus | 125 | |||

| E. coli | 125 | ||||

| A. glabrata | (8S)-10-Benzoyloxy-8,9-epoxy-6-hydroxythymol isobutyrate (26) | MTT/PMS | E. histolytica | IC50 (µM) 1.6 | [35] |

| G. lamblia | 36.9 | ||||

| 10-Benzoyloxy-8,9-epoxy-6-acetyloxythymol isobutyrate (27) | E. histolytica | 0.84 | |||

| G. lamblia | 24.2 | ||||

| 10-Benzoyloxy-8,9-epoxy-6-methoxythymol isobutyrate (28) | E. histolytica | 169.6 | |||

| G. lamblia | 191.2 | ||||

| 10-Benzoyloxy-8,9-epoxythymol isobutyrate (29) | E. histolytica | 25.9 | |||

| G. lamblia | 48.3 | ||||

| 10-Benzoyloxy-8,9-dehydro-6-hydroxythymol isobutyrate (30) | E. histolytica | 61.2 | |||

| G. lamblia | 68.0 | ||||

| 10-Benzoyloxy-6,8-dihydroxy-9-isobutyryloxythymol (31) | E. histolytica | 45.6 | |||

| G. lamblia | 60.7 | ||||

| Pectolinaringenin (32) | E. histolytica | 43.6 | |||

| G. lamblia | 68.7 | ||||

| (8S)-8,9-epoxy-6-hydroxy-10-benzoyloxy-7-oxothymol isobutyrate (33) | E. histolytica | 184.9 | |||

| G. lamblia | 167.4 | ||||

| A. jocotepecana | (−)-(5S,9S,10S,13S)-labd-7-en-15-oic acid (34) | μd | S. aureus | MIC (mg/mL) 0.78 | [41] |

| B. subtilis | 0.15 | ||||

| (−)-(5S,9S,10S,13Z)-labda-7,13-dien-15-oic acid (35) | S. aureus | 1.00 | |||

| B. subtilis | 10.00 | ||||

| (+)-(5S,8R,9R,10S,13R)-8-hydroxylabdan-15-oic acid (36) | S. aureus | 2.34 | |||

| B. subtilis | 1.56 | ||||

| A. adenophora | Encecalin (37) | Df disc (50 μg/disc) | F. oxysporum f. sp. niveum | DIZ (mm) 10.00 ± 0.15 | [25] |

| 7-hydroxy-dehydrotremetone (38) | C. gloeosporioides | 17.28 ± 0.46 | |||

| C. musae | 17.24 ± 0.52 | ||||

| R. solani | 16.40 ± 0.81 | ||||

| F. oxysporum f. sp. niveum | 13.90 ± 1.05 | ||||

| A. alternata | 14.36 ± 0.68 | ||||

| A. cylindrica | Cylindrinol B (39) | NA | E. histolytica | IC50 (µM) 287.5 | [31] |

| G. lamblia | 226.2 | ||||

| Cylindrinol C (40) | E. histolytica | 237.0 | |||

| G. lamblia | 251.9 | ||||

| Cylindrinol D (41) | E. histolytica | 86.9 | |||

| G. lamblia | 134.0 | ||||

| Cylindrinol E (42) | E. histolytica | 210.2 | |||

| G. lamblia | 164.5 | ||||

| Cylindrinol F (43) | E. histolytica | 213.2 | |||

| G. lamblia | 151.1 | ||||

| ent-15β-(β-L-fucosyloxy)kaur-16-en-19-oic acid β-Dglucopyranosyl ester (44) | E. histolytica | 43.3 | [30] | ||

| G. lamblia | 41.9 | ||||

| ent-15β-(4-acetoxy-β-L-fucosyloxy) kaur-16-en-19-oic acid β-D-glucopyranosyl ester (45) | E. histolytica | 49.5 | |||

| G. lamblia | 69.5 | ||||

| ent-15β-(3-acetoxy-β-L-fucosyloxy) kaur-16-en-19-oic acid β-D-glucopyranosyl ester (46) | E. histolytica | 52.7 | |||

| G. lamblia | 48.9 | ||||

| ent-15β-(β-L-fucosyloxy)kaur-16-en-19-oic acid (47) | E. histolytica | 73.5 | |||

| G. lamblia | 98.5 | ||||

| (8S)-8,9-epoxy-6-hydroxy-10-benzoyloxy-7-oxothymol isobutyrate (33) | E. histolytica | 184.9 | [29] | ||

| G. lamblia | 167.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rojas-Jiménez, S.; Salinas-Sánchez, D.O.; Rodríguez-López, V.; Salinas-Marín, R.; Avilés-Montes, D.; Sotelo-Leyva, C.; Figueroa-Brito, R.; Bustos Rivera-Bahena, G.; Abarca-Vargas, R.; Arias-Ataide, D.M.; et al. Cytotoxic and Antimicrobial Activity of the Ageratina Genus. Molecules 2025, 30, 4656. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234656

Rojas-Jiménez S, Salinas-Sánchez DO, Rodríguez-López V, Salinas-Marín R, Avilés-Montes D, Sotelo-Leyva C, Figueroa-Brito R, Bustos Rivera-Bahena G, Abarca-Vargas R, Arias-Ataide DM, et al. Cytotoxic and Antimicrobial Activity of the Ageratina Genus. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4656. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234656

Chicago/Turabian StyleRojas-Jiménez, Sarai, David Osvaldo Salinas-Sánchez, Verónica Rodríguez-López, Roberta Salinas-Marín, Dante Avilés-Montes, César Sotelo-Leyva, Rodolfo Figueroa-Brito, Genoveva Bustos Rivera-Bahena, Rodolfo Abarca-Vargas, Dulce María Arias-Ataide, and et al. 2025. "Cytotoxic and Antimicrobial Activity of the Ageratina Genus" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4656. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234656

APA StyleRojas-Jiménez, S., Salinas-Sánchez, D. O., Rodríguez-López, V., Salinas-Marín, R., Avilés-Montes, D., Sotelo-Leyva, C., Figueroa-Brito, R., Bustos Rivera-Bahena, G., Abarca-Vargas, R., Arias-Ataide, D. M., & Valladares-Cisneros, M. G. (2025). Cytotoxic and Antimicrobial Activity of the Ageratina Genus. Molecules, 30(23), 4656. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234656