Enzymatic Production of Sustainable Aviation Fuels from Waste Feedstock

Abstract

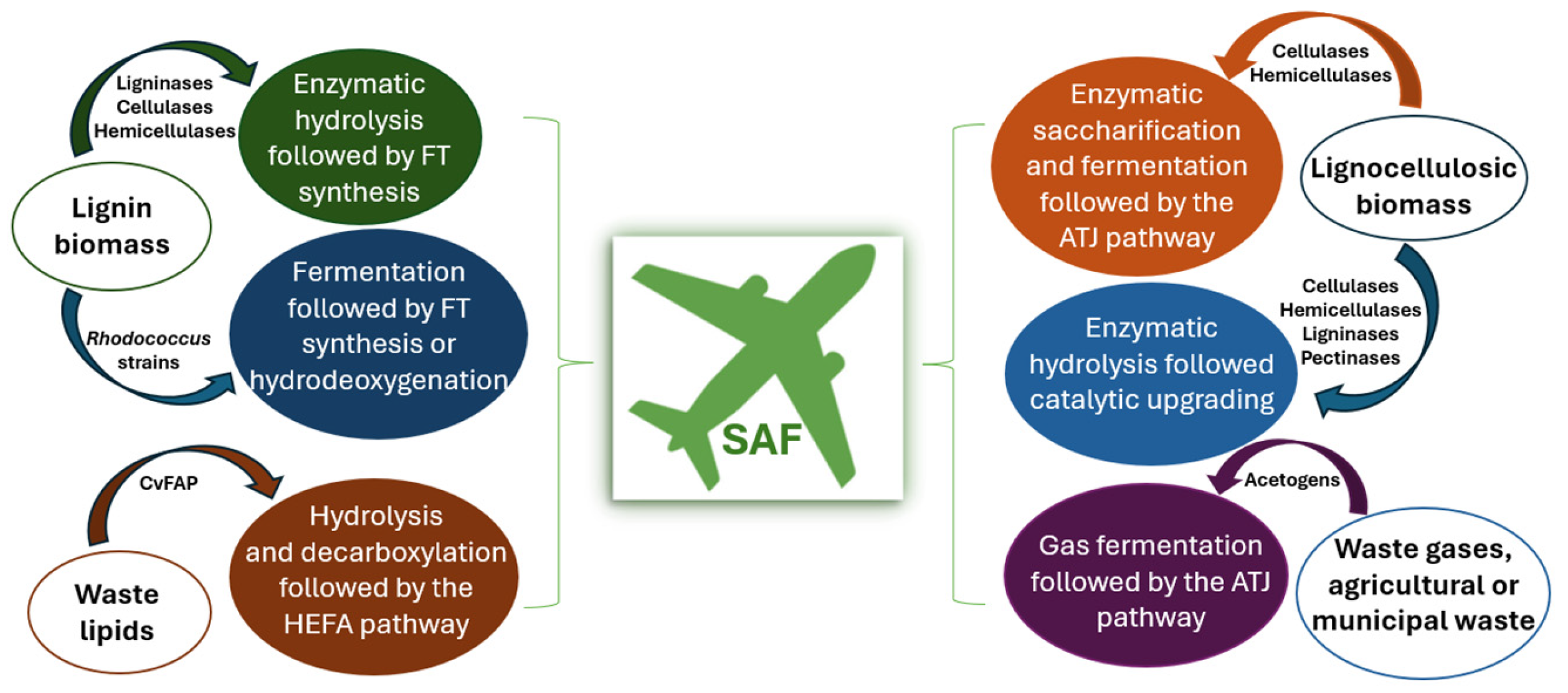

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Review Studies for SAF Production via Enzymatic Processes of Waste Biomass

2.2. Experimental Studies for SAF Production via Enzymatic Processes of Waste Biomass

| Waste Feedstock | Enzyme | Production Method/ SAF Pathway | Biojet Range Hydrocarbons or SAF Precursors | Highlights | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recycled Paper | Cellulase | Enzymatic/Acid Hydrolysis followed by catalytic conversion and upgrading | Biojet: 76–83 million bbl/year | The minimum selling price estimate for paper-derived jet fuel is $3.97 per gallon. Direct cellulose hydrogenation could reduce capital and operating costs. | [28] |

| Food waste-derived CO2 and CH4 | Photosynthetic and methanotrophic microorganisms | Anaerobic digestion/ Hydrocracking | Biojet: 0.137 kg CO2eq/MJ | By utilizing both CH4 and CO2 from biogas and taking advantage of potential subsidies for food waste disposal, bioroute-based SAF could become economically viable. | [29] |

| Food waste | CvFAP in the biphasic system | Photoenzymatic decarboxylation and anaerobic digestion | The decarboxylation products were 8-heptadecene (C17:1) and 6,9-heptadecadiene (C17:2) | CvFAP achieved the highest conversion of palmitic acid in a biphasic system using petroleum ether as the oil phase, reaching a rate 26.4 times higher than in a single-phase catalysis setup. | [30] |

| Palmitic acid as the model substrate for waste cooking oil | Chlorella variabilis fatty acid photodecarboxylase broken cells (CvFAP BCs) and CvFAP@E. coli | Photoenzymatic decarboxylation | Yields of 88.4% were obtained for pentadecane using CvFAP@E. coli, while CvFAP BCs achieved a yield of 95.4%. | The highest conversion rate of 17.2 mM·h−1 for CvFAP BCs was achieved, marking the highest rate ever reported. | [31] |

| Waste oils | CvFAP | Photoenzymatic decarboxylation | C15-C17 hydrocarbon biofuel | The CvFAP biocatalyst’s 100% selectivity for C15-C17 in biofuel production under mild conditions demonstrates the advantage of exclusive decarboxylation. | [32] |

| Garden waste | Mixed culture | Arrested anaerobic digestion and chain elongation | Caproic acid as a potential SAF precursor | High caproic acid yield was achieved under optimized conditions and gradual ethanol feeding, resulting in enhanced efficiency compared to batch fermentation. | [33] |

| Softwood residues | Modified bacterial E. coli strains | Enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation/ATJ | Isobutene as SAF precursor | High GHG emission reduction (up to 80.1%) under optimal setups. The effective utilization of by-products, such as lignin, animal feed, and fertilizers, enhances system efficiency. | [34] |

| Pre- and post-consumer food waste | Engineered amylase | Simultaneous saccharification and fermentation | Bioethanol as SAF precursor: Yield: 61.2% to 87.6% | Thermal sterilization at an elevated liquefaction temperature significantly enhanced ethanol yields from pre-and post-consumer food waste, outperforming chemical decontamination methods. | [35] |

| Office paper waste | Yeast isolated from rotten banana | Enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation/ATJ | Bioethanol as SAF precursor Total flux 253.06 g/m2·h | When integrated into a pervaporation system using an Amicon cell, the membrane effectively increased the bioethanol content from 30% to 63%. | [36] |

| Potato by-products | Alpha-amylase | ABE fermentation and catalytic upgrading/ATJ | Biojet: 10.7 total kt/y | Depending on the chosen feedstock and processing configuration, the GHG emission reduction potential of the innovative jet fuel was estimated to range between 41% and 52%. | [37] |

| Case 1: Wheat straw (WS) Case 2: Industrial cellulosic residue(ICR) | Cellulase | Enzymatic saccharification and fermentation/HDO of higher carbon alcohols | Biojet: 7.2 tonnes WS/ tonne biojet fuel (Case 1) Biojet: 16 tonnes ICR/ tonne biojet fuel (Case 2) | Monte Carlo risk analysis indicates a high likelihood of profitability, with a 96.66% probability for Case 1 and an even higher 99.99% probability for Case 2, given the current bio-jet fuel price of 15,000 CNY per tonne. | [38] |

| Palm Oil Mill Effluent | Immobilized lipase | Enzymatic Hydrolysis/ Hydrocracking | Biojet: 94% yield and 57.44% selectivity | High free fatty acid yield (90%), efficient hydrocarbon production using low catalyst loading | [39] |

| Sugarcane derived microbial oil | Oleaginous yeast | Aerobic fermentation/HEFA | Biojet: 2450 L/ha | SAF produced from microbial oil achieves a reduction of over 50% in GHG emissions compared to fossil fuels. Additionally, microbial oil derived from sugarcane yields four times higher SAF per unit area than soybean oil. | [40] |

| Paper sludge | Cellulase: Cellic CTec2 from Novozymes | Enzymatic hydrolysis, dehydration, and aldol condensation/ Hydroprocessing | More than 330 million gallons of SAF can be produced annually from the over 4 million dry tonnes of paper sludge available each year in the U.S. | The GWP of converting one dry ton of paper sludge to SAF is estimated to range from −584 to −636 kg CO2 eq per dry ton without ash utilization and from −873 to −925 kg CO2 eq per dry ton with ash utilization. | [41] |

| Lipid-rich wastewater | CvFAP | Photoenzymatic decarboxylation | Biojet: Production rate of 59.8 mM/h | Continuous photoenzymatic decarboxylation in a microfluidic photobioreactor yielded an impressive energy output of 33.6 kJ·g−1. | [42] |

| Corn Stover | Novozymes | Enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation/ Catalytic upgrading | Biojet: 35 wt. % or 40.9% carbon-based yield | The jet fuel blendstock contains desirable n-alkanes, isoalkanes, and monocyclic cycloalkanes, along with undesirable alkynes and olefins. | [43] |

| Straw biomass | C. beijerinckii strain | Iron-catalyzed hydrogen peroxide pretreatment, enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation/ ATJ | Bio-Jet: Conversion of 94.9% and selectivity of 77.3% | Fe-HP pretreatment enhanced sugar yield and concentration during enzymatic hydrolysis, facilitating more efficient fermentation and bio-jet fuel production. | [44] |

| Logging residues | Microbial strains | Enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation/ ATJ | Biojet: 81,540 L/day and 102,600 L/day for Ethanol-to-Jet and Isobutanol-to-Jet pathways, respectively. | In the ATJ pathway, the minimum average selling price with co-product credit was lower for the Iso-BTJ pathway compared to the ETJ pathway. | [45] |

3. LCA and Economic Viability of SAF Produced via Enzymatic Processes

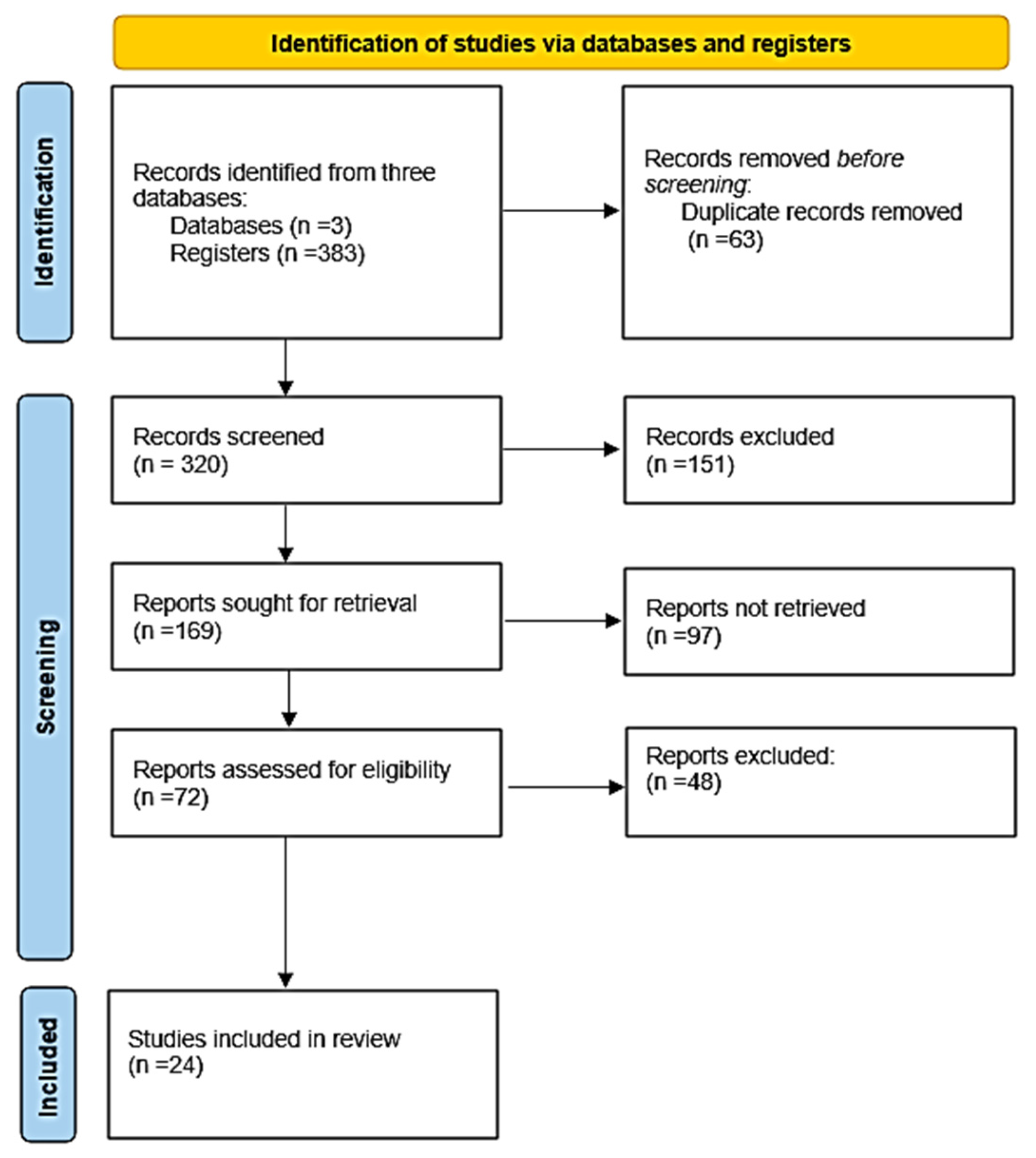

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAD | Arrested anaerobic digestion |

| ABE | Acetone-butanol-ethanol |

| AD | Anaerobic digestion |

| AMP | Antimicrobial peptides |

| ATJ | Alcohol-to-Jet |

| ASTM | American Society for Testing and Materials |

| BC | Broken cells |

| 2,3-BDO | 2,3-butanediol |

| CE | Chain elongation |

| CVFAP | Chlorella variabilis fatty acid photodecarboxylase |

| ETJ | Ethanol-to-Jet |

| Fe-HP | Iron ion-catalyzed hydrogen peroxide |

| FFAs | Free fatty acids |

| FT | Fischer-Tropsch |

| GHG | Greenhouse gases |

| GWP | Global warming potential |

| HDO | Hydrodeoxygenation |

| HEFA-SPK | Hydroprocessed Esters and Fatty Acids-Synthetic |

| HPOME | Hydrolyzed palm oil mill effluent |

| ICAO | International Civil Aviation Organization |

| Iso-BTJ | Iso-Butanol-to-Jet |

| LCA | Life cycle assessment |

| LCFA | Long-chain fatty acids |

| LI-BRES | Lignin boiler, RES grid |

| MEK | Methyl ethyl ketone |

| MO | Microbial oil |

| MSW | Municipal solid waste |

| NOC | Non-oil components |

| PAMPS | Poly (2-acrylamido−2-methyl−1-propanesulfonic acid) |

| PMB | Potassium metabisulfite |

| POME | Palm oil mill effluent |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| SAF | Sustainable aviation fuels |

| SPVC | Sulfonated polyvinyl chloride |

| TOS | Time-on-stream |

| UHC | Unburnt hydrocarbons |

| WO | Waste oil |

References

- Kokkinos, N.; Emmanouilidou, E.; Sharma, S. Waste-To-Biofuel Production for the Transportation Sector. In Intelligent Transportation System and Advanced Technology. Energy, Environment, and Sustainability; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Energy System, Aviation. 2025. Available online: https://www.iea.org/energy-system/transport/aviation (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Emmanouilidou, E.; Mitkidou, S.; Agapiou, A.; Kokkinos, N. Solid waste biomass as a potential feedstock for producing sustainable aviation fuel: A systematic review. Renew. Energy 2023, 206, 897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Renewables 2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/renewables-2024 (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Feng, L.; Sun, Y.; Lin, K.; Guo, X.; Xia, A.; Kumar, V.; Zhu, X.; Zhao, W.; Liao, Q. Photo-driven decarboxylation for sustainable biofuel production: A review on harnessing potential of fatty acid decarboxylases. Chem. Commun. 2025, 61, 18273–18288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, B.; Chong, C.T.; Ge, Y.; Ong, H.C.; Ng, J.-H.; Tian, B.; Veeramuthu, A.; Lim, S.; Seljak, T.; Józsa, V. Progress in utilisation of waste cooking oil for sustainable biodiesel and biojet fuel production. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 223, 113296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Nie, Y.; Ban, L.; Wu, D.; Yang, S.; Zhang, H.; Li, C.; Zhang, K. Photocatalytic and Electrochemical Synthesis of Biofuel via Efficient Valorization of Biomass. Adv. Energy Mater. 2025, 15, 2406098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, A.E.; Klass, S.H.; Winegar, P.H.; Keasling, J.D. Microbial production of fuels, commodity chemicals, and materials from sustainable sources of carbon and energy. Curr. Opin. Syst. Biol. 2023, 36, 100482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Mosier, N.; Ladisch, M. Valorization of lignin from aqueous-based lignocellulosic biorefineries. Trends Biotechnol. 2024, 42, 1348–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Guan, D.; Xia, S.; Fan, Y.; Zhao, K.; Zhao, Z.; Zheng, A. Recent advances, challenges, and opportunities in lignin valorization for value-Added chemicals, biofuels, and polymeric materials. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 322, 119123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkinos, N.C.; Emmanouilidou, E. Waste-to-Energy: Applications and Perspectives on Sustainable Aviation Fuel Production. In Energy, Environment, and Sustainability; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 265–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D1655-22a; Standard Specification for Aviation Turbine Fuels. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023. [CrossRef]

- ASTM D7566-24d; Standard Specification for Aviation Turbine Fuel Containing Synthesized Hydrocarbons. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Raji, A.M.; Manescau, B.; Chetehouna, K.; Ekomy Ango, S.; Ogabi, R. Performance and spray characteristics of fossil JET A-1 and bioJET fuel: A comprehensive review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 207, 114970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun-Unkhoff, M.; Kathrotia, T.; Rauch, B.; Riedel, U. About the interaction between composition and performance of alternative jet fuels. CEAS Aeronaut. J. 2016, 7, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Li, Z.; Liu, Z. Comparison of Emission Properties of Sustainable Aviation Fuels and Conventional Aviation Fuels: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; Deng, C.; Zhang, W.; Hollmann, F.; Murphy, J.D. Production of Bio-alkanes from Biomass and CO2. Trends Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomás-Pejó, E.; Morales-Palomo, S.; González-Fernández, C. Microbial lipids from organic wastes: Outlook and challenges. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 323, 124612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, S.; Dien, B.S.; Eilts, K.K.; Sacks, E.J.; Singh, V. Pilot-scale processing of Miscanthus x giganteus for recovery of anthocyanins integrated with production of microbial lipids and lignin-rich residue. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 485, 150117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santner, P.; Chanquia, S.N.; Petrovai, N.; Benfeldt, F.V.; Kara, S.; Eser, B.E. Biocatalytic conversion of fatty acids into drop-in biofuels: Towards sustainable energy sources. EFB Bioeconomy J. 2023, 3, 100049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolah, R.; Zafar, S.; Hassan, M.Z. Chapter 8—Alternative jet fuels: Biojet fuels’ challenges and opportunities. In Value-Chain of Biofuels; Yusup, S., Rashidi, N.A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 181–194. [Google Scholar]

- Kocaturk, E.; Salan, T.; Ozcelik, O.; Alma, M.H.; Candan, Z. Recent Advances in Lignin-Based Biofuel Production. Energies 2023, 16, 3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.-M.; Liu, Z.-H.; Zhang, T.; Meng, R.; Gong, Z.; Li, Y.; Hu, J.; Ragauskas, A.J.; Li, B.-Z.; Yuan, Y.-J. Unleashing the capacity of Rhodococcus for converting lignin into lipids. Biotechnol. Adv. 2024, 70, 108274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Xia, A.; Zhang, W.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhu, X.; Liao, Q. Photoenzymatic decarboxylation: A promising way to produce sustainable aviation fuels and fine chemicals. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 367, 128232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashokkumar, V.; Venkatkarthick, R.; Jayashree, S.; Chuetor, S.; Dharmaraj, S.; Kumar, G.; Chen, W.-H.; Ngamcharussrivichai, C. Recent advances in lignocellulosic biomass for biofuels and value-added bioproducts—A critical review. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 344, 126195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, K.; Pedroso, M.; Harris, A.; Garg, S.; Hine, D.; Köpke, M.; Schenk, G.; Marcellin, E. Gas fermentation for microbial sustainable aviation fuel production. Microbiol. Aust. 2023, 44, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynd, L.R.; Beckham, G.T.; Guss, A.M.; Jayakody, L.N.; Karp, E.M.; Maranas, C.; McCormick, R.L.; Amador-Noguez, D.; Bomble, Y.J.; Davison, B.H.; et al. Toward low-cost biological and hybrid biological/catalytic conversion of cellulosic biomass to fuels. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 938–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubic, W.L.; Moore, C.M.; Semelsberger, T.A.; Sutton, A.D. Recycled Paper as a Source of Renewable Jet Fuel in the United States. Front. Energy Res. 2021, 9, 728682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Fu, R.; Kang, L.; Ma, Y.; Fan, D.; Fei, Q. An upcycling bioprocess for sustainable aviation fuel production from food waste-derived greenhouse gases: Life cycle assessment and techno-economic analysis. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 486, 150242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Xia, A.; Feng, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, X.; Liao, Q. Integrating photoenzymatic decarboxylation and anaerobic digestion to convert food waste into hydrocarbon: Performance and process intensification. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 308, 118409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Xia, A.; Li, F.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, X.; Liao, Q. Photoenzymatic decarboxylation to produce renewable hydrocarbon fuels: A comparison between whole-cell and broken-cell biocatalysts. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 255, 115311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Xia, A.; Guo, X.; Zhang, W.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhu, X.; Liao, Q. Continuous hydrocarbon fuels production by photoenzymatic decarboxylation of free fatty acids from waste oils. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 110748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandra Harahap, B.; Ahring, B.K. Caproic acid production from short-chained carboxylic acids produced by arrested anaerobic digestion of green waste: Development and optimization of a mixed caproic acid producing culture. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 414, 131573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puschnigg, S.; Fazeni-Fraisl, K.; Lindorfer, J.; Kienberger, T. Biorefinery development for the conversion of softwood residues into sustainable aviation fuel: Implications from life cycle assessment and energetic-exergetic analyses. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 386, 135815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rooyen, J.; Mbella Teke, G.; Coetzee, G.; van Rensburg, E.; Ferdinand Görgens, J. Enhancing bioethanol yield from food waste: Integrating decontamination strategies and enzyme dosage optimization for sustainable biofuel production. Fuel 2024, 378, 133026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansy, A.E.; El Desouky, E.A.; Taha, T.H.; Abu-Saied, M.A.; El-Gendi, H.; Amer, R.A.; Tian, Z.-Y. Sustainable production of bioethanol from office paper waste and its purification via blended polymeric membrane. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 299, 117855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, C.; López-Contreras, A.; De Vrije, T.; Kraft, A.; Junginger, M.; Shen, L. From agricultural (by-)products to jet fuels: Carbon footprint and economic performance. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 775, 145848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Chen, B.; Wang, T.; Zhao, X. A promising technical route for converting lignocellulose to bio-jet fuels based on bioconversion of biomass and coupling of aqueous ethanol: A techno-economic assessment. Fuel 2025, 381, 133670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muanruksa, P.; Winterburn, J.; Kaewkannetra, P. Biojet Fuel Production from Waste of Palm Oil Mill Effluent through Enzymatic Hydrolysis and Decarboxylation. Catalysts 2021, 11, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchesan, A.N.; Sampaio ILde, M.; Chagas, M.F.; Generoso, W.C.; Hernandes, T.A.D.; Morais, E.R.; Junqueira, T.L. Alternative feedstocks for sustainable aviation fuels: Assessment of sugarcane-derived microbial oil. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 416, 131772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, K.; Cruz, D.; Li, J.; Agyei Boakye, A.A.; Park, H.; Tiller, P.; Mittal, A.; Johnson, D.K.; Park, S.; Yao, Y. Life-Cycle Assessment of Sustainable Aviation Fuel Derived from Paper Sludge. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 8379–8390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Xia, A.; Guo, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, W.; Chen, R.; Liao, Q. Photo-driven enzymatic decarboxylation of fatty acids for bio-aviation fuels production in a continuous microfluidic reactor. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 183, 113507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affandy, M.; Zhu, C.; Swita, M.; Hofstad, B.; Cronin, D.; Elander, R.; Lebarbier Dagle, V. Production and catalytic upgrading of 2,3-butanediol fermentation broth into sustainable aviation fuel blendstock and fuel properties measurement. Fuel 2023, 333, 126328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Zhang, R.; He, Y.; Zhu, C.; Jiang, Y.; Ni, Y.; Fan, M.; Li, Q. Iron ion catalyzed hydrogen peroxide pretreatment for bio-jet fuel production from straw biomass. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2024, 99, 1810–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, H.A.; Masum, F.H.; Dwivedi, P. Life cycle emissions and unit production cost of sustainable aviation fuel from logging residues in Georgia, United States. Renew. Energy 2024, 228, 120611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, R.; Ghosh, P.; Tyagi, B.; Vijay, V.K.; Vijay, V.; Thakur, I.S.; Kamyab, H.; Nguyen, D.D.; Kumar, A. Advances in biogas valorization and utilization systems: A comprehensive review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 273, 123052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prussi, M.; Lee, U.; Wang, M.; Malina, R.; Valin, H.; Taheripour, F.; Velarde, C.; Staples, M.D.; Lonza, L.; Hileman, J.I. CORSIA: The first internationally adopted approach to calculate life-cycle GHG emissions for aviation fuels. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 150, 111398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, A.H.; Zhang, Y.; Milbrandt, A.; Newes, E.; Moriarty, K.; Klein, B.; Tao, L. Evaluation of performance variables to accelerate the deployment of sustainable aviation fuels at a regional scale. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 275, 116441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroz, D.; Greene, J.M.; Limb, B.J.; Quinn, J.C. Prospective Life Cycle Assessment of Sustainable Aviation Fuel Systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 19269–19282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrill, E.; Koh, S.C.L.; Yuan, R. Review of technological developments and LCA applications on biobased SAF conversion processes. Front. Fuels 2024, 2, 1397962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Yao, Y. Sustainable aviation fuel pathways: Emissions, costs and uncertainty. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 215, 108124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mero, M.; Mesazou, V.; Emmanouilidou, E.; Kokkinos, N.C. Enzymatic Production of Sustainable Aviation Fuels from Waste Feedstock. Molecules 2025, 30, 4648. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234648

Mero M, Mesazou V, Emmanouilidou E, Kokkinos NC. Enzymatic Production of Sustainable Aviation Fuels from Waste Feedstock. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4648. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234648

Chicago/Turabian StyleMero, Maria, Vasiliki Mesazou, Elissavet Emmanouilidou, and Nikolaos C. Kokkinos. 2025. "Enzymatic Production of Sustainable Aviation Fuels from Waste Feedstock" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4648. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234648

APA StyleMero, M., Mesazou, V., Emmanouilidou, E., & Kokkinos, N. C. (2025). Enzymatic Production of Sustainable Aviation Fuels from Waste Feedstock. Molecules, 30(23), 4648. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234648