Impact of Drying Methods on β-Glucan Retention and Lipid Stability in Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) Enriched Carp (Cyprinus carpio, L.) Fish Burgers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Raw Materials

2.1.1. Basic Characteristics

2.1.2. Determination of Total Glucans Content

2.1.3. Determination of Lipid Quality Parameters

2.1.4. Fatty Acid Composition

2.2. Fish Burgers with Hot-Air Dried and Freeze-Dried Oyster Mushrooms

2.2.1. Basic Characteristics

2.2.2. Determination of Total Glucans Content

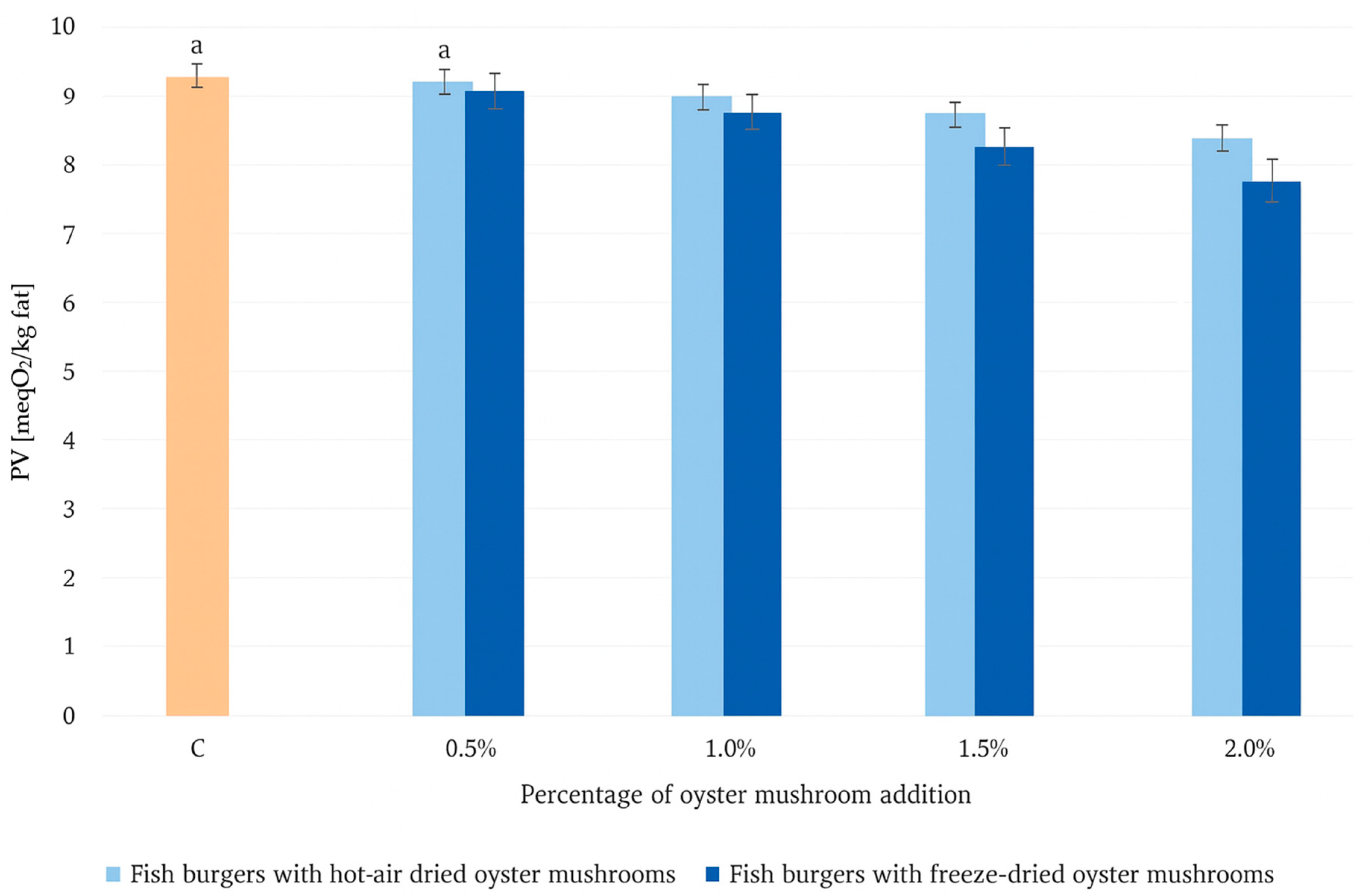

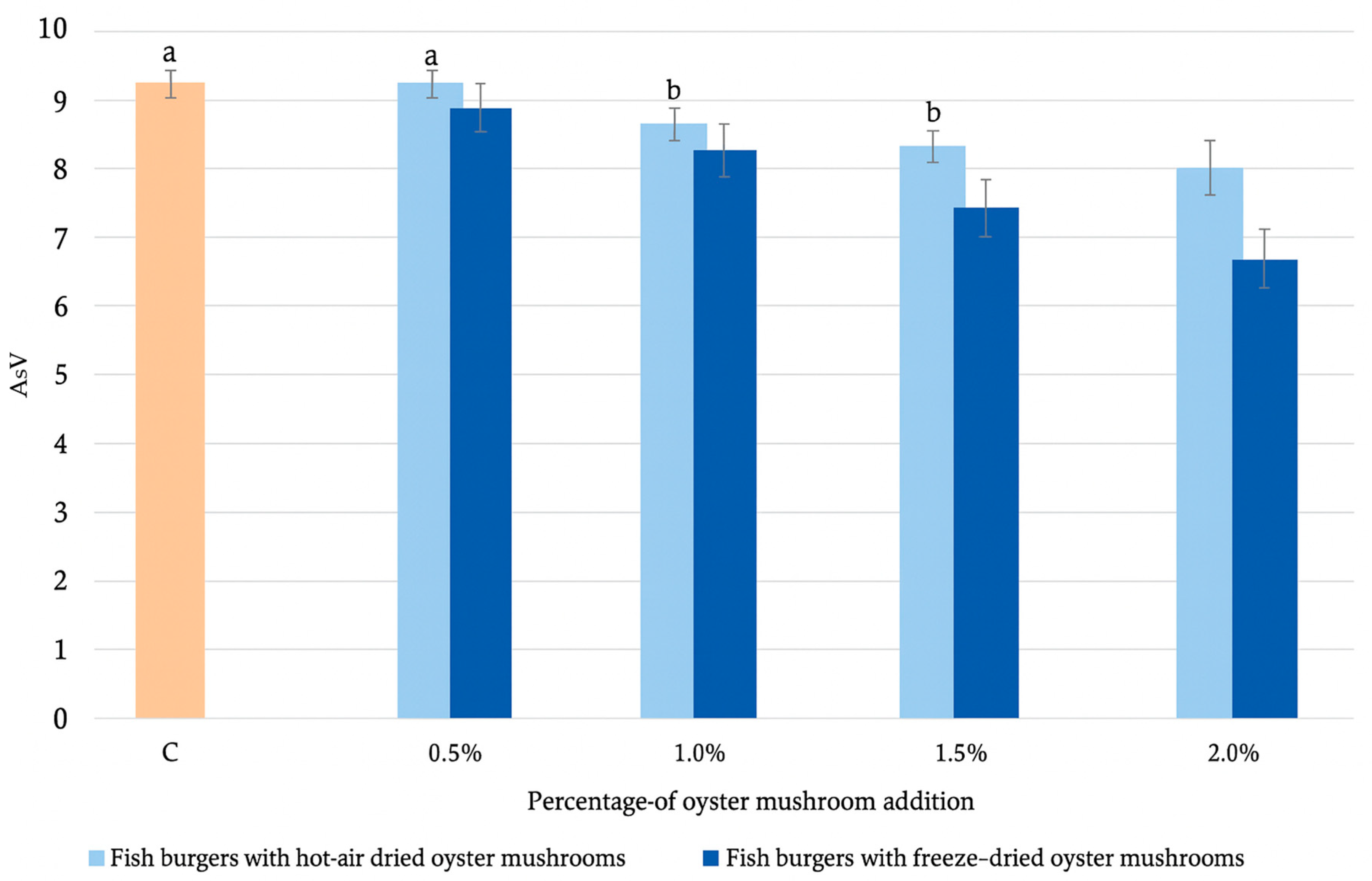

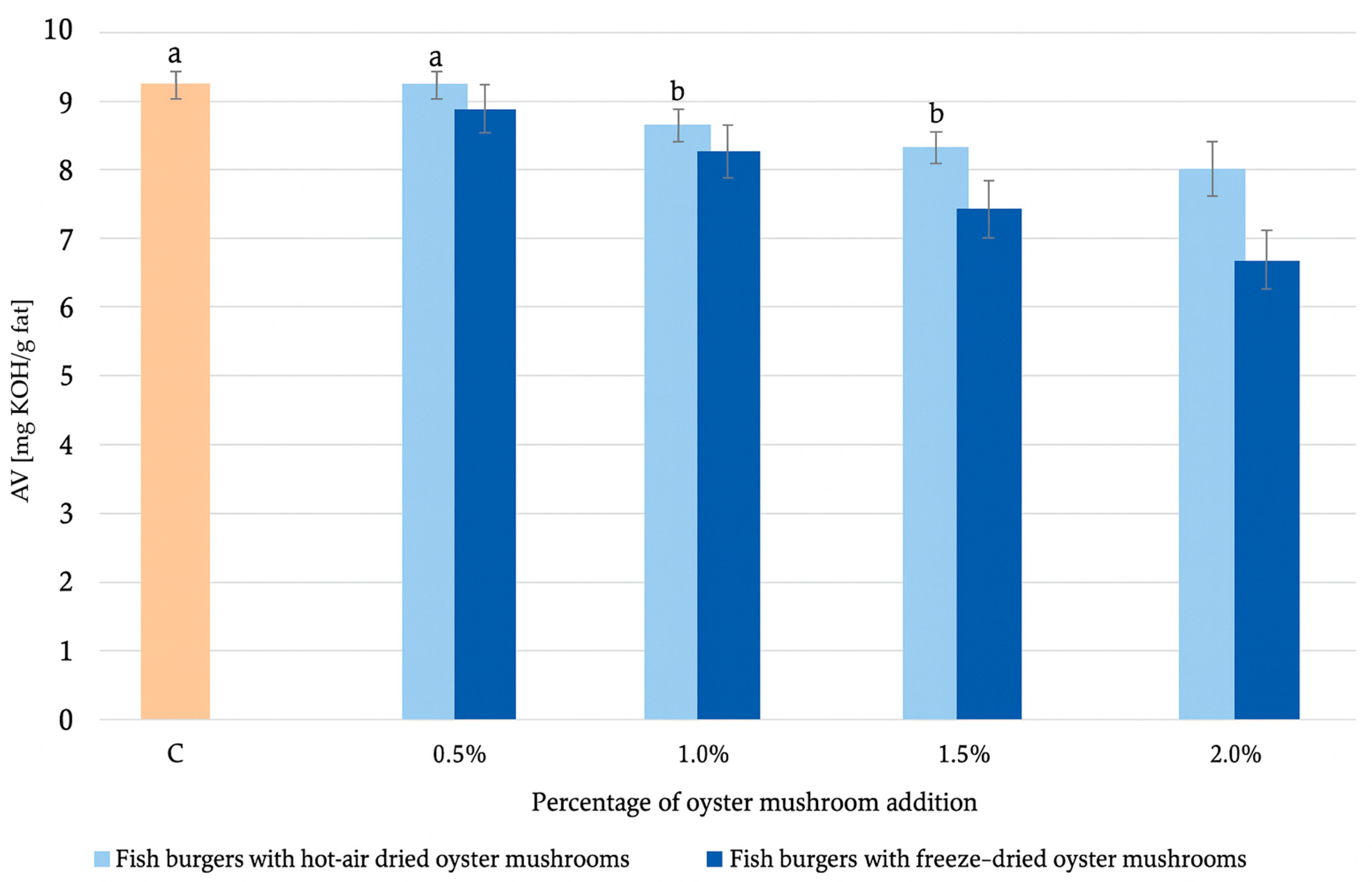

2.2.3. Determination of Lipid Quality Parameters

2.2.4. Fatty Acids Composition

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Preparation of Fish Burgers

3.3. Methods

3.3.1. Proximate Analysis

3.3.2. Total Glucans Content

3.3.3. Determination of Lipid Quality Parameters

3.3.4. Fatty Acids Composition (FAs)

3.3.5. Nutritional Quality Indices of Lipids

- Index of Atherogenicity (AI)

- Index of Thrombogenicity (TI)

- Hypocholesterolemic/Hypercholesterolemic (HH) Ratio

- Fish Lipid Quality/Flesh Lipid Quality (FLQ)

- Health-Promoting Index (HPI)

3.3.6. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020; Sustainability in action; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Understanding Antimicrobial Resistance in Aquaculture. CONTENTS Acknowledgements and Disclaimer Iv. Available online: https://www.asianfisheriessociety.org/publication/archivedetails.php?id=volume-33-special-issue-understanding-antimicrobial-resistance-in-aquaculture&q=1 (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Maghfira, L.L.; Stündl, L.; Fehér, M.; Asmediana, A. Review on the Fatty Acid Profile and Free Fatty acid of Common carp (Cyprinus carpio). Acta Agrar. Debreceniensis 2023, 2, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokarczyk, G.; Felisiak, K.; Adamska, I.; Przybylska, S.; Hrebień-Filisińska, A.; Biernacka, P.; Bienkiewicz, G.; Tabaszewska, M. Effect of Oyster Mushroom Addition on Improving the Sensory Properties, Nutritional Value and Increasing the Antioxidant Potential of Carp Meat Burgers. Molecules 2023, 28, 6975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hematyar, N.; Rustad, T.; Sampels, S.; Kastrup Dalsgaard, T. Relationship Between Lipid and Protein Oxidation in Fish. Aquac. Res. 2019, 50, 1393–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirończuk-Chodakowska, I.; Witkowska, A.M. Evaluation of Polish Wild Mushrooms as Beta-Glucan Sources. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galappaththi, M.; Dauner, L.; Madawala, S.; Karunarathna, S. Nutritional and Medicinal Benefits of Oyster (Pleurotus) Mushrooms: A Review. Fungal Biotec 2021, 1, 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayachandran, M.; Xiao, J.; Xu, B. A Critical Review on Health Promoting Benefits of Edible Mushrooms Through Gut Microbiota. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Ramady, H.; Abdalla, N.; Fawzy, Z.; Badgar, K.; Llanaj, X.; Törős, G.; Hajdú, P.; Eid, Y.; Prokisch, J. Green Biotechnology of Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus L.): A Sustainable Strategy for Myco-Remediation and Bio-Fermentation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeasmin, F.; Rahman, H.; Rana, S.; Khan, J.; Islam, N. The Optimization of the Drying Process and Vitamin C Retention of Carambola: An Impact of Storage and Temperature. J. Food Process Preserv. 2021, 45, e15037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, D.; Jakubczyk, E. The Freeze-Drying of Foods—The Characteristic of the Process Course and the Effect of Its Parameters on the Physical Properties of Food Materials. Foods 2020, 9, 1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.; Sarker, M.; Lata, M.B.; Islam, A.; Al Faik, A.; Sarkar, S. Physicochemical Properties and Sensory Evaluation of Sponge Cake Supplemented with Hot Air and Freeze Dried Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus Sajor-Caju). World J. Eng. Technol. 2020, 8, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patinho, I.; Saldaña, E.; Selani, M.M.; de Camargo, A.C.; Merlo, T.C.; Menegali, B.S.; de Souza Silva, A.P.; Contreras-Castillo, C.J. Use of Agaricus Bisporus Mushroom in Beef Burgers: Antioxidant, Flavor Enhancer and Fat Replacing Potential. Food Prod. Process. Nutr. 2019, 1, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerón-Guevara, M.I.; Rangel-Vargas, E.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Bermúdez, R.; Pateiro, M.; Rodríguez, J.A.; Sánchez-Ortega, I.; Santos, E.M. Reduction of Salt and Fat in Frankfurter Sausages by Addition of Agaricus Bisporus and Pleurotus Ostreatus Flour. Foods 2020, 9, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, D.; Bal, M.A.; Figueredo, S.; Soler-Rivas, C.; Ruiz-Rodríguez, A. Effect of Household Cooking Treatments on the Stability of β-Glucans, Ergosterol, and Phenolic Compounds in White-Button (Agaricus bisporus) and Shiitake (Lentinula edodes) Mushrooms. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2024, 17, 791–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeković, D.B.; Kwiatkowski, S.; Vrvić, M.M.; Jakovljević, D.; Moran, C.A. Natural and Modified (1→3)-β-D-Glucans in Health Promotion and Disease Alleviation. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2005, 25, 205–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Liu, H. Nutritional Indices for Assessing Fatty Acids: A Mini-Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.; Shen, Q.; Wang, L.; Fan, X.; Zhuang, Y. Effects of Different Drying Methods on the Physical Characteristics and Non-Volatile Taste Components of Schizophyllum commune. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 123, 105632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, R.; Singh, J.; Dash, K.K.; Dar, A.H. Comparative Study of Freeze Drying and Cabinet Drying of Button Mushroom. Appl. Food Res. 2022, 2, 100084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanti, I.; Muhamaludin; Aji, G.K.; Ikhsan, H.M.; Widodo, W.E.; Komariah, K.; Saleh, H.; Zahra, W.; Pranamuda, H. Physicochemical and Sensory Properties of Beta Glucan Product as a Health Supplement to Boost Immune System. AIP Conf. Proc. 2024, 2957, 60048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiozzi, V.; Eliopoulos, C.; Markou, G.; Arapoglou, D.; Agriopoulou, S.; El Enshasy, H.A.; Varzakas, T. Biotechnological Addition of β-Glucans from Cereals, Mushrooms and Yeasts in Foods and Animal Feed. Processes 2021, 9, 1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piskov, S.; Timchenko, L.; Grimm, W.D.; Rzhepakovsky, I.; Avanesyan, S.; Sizonenko, M.; Kurchenko, V. Effects of Various Drying Methods on Some Physico-Chemical Properties and the Antioxidant Profile and ACE Inhibition Activity of Oyster Mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus). Foods 2020, 9, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallotti, F.; Lavoisier, A.; Turchiuli, C.; Lavelli, V. Impact of Pleurotus Ostreatus β-Glucans on Oxidative Stability of Active Compounds Encapsulated in Powders During Storage and In Vitro Digestion. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, K.; Guo, F.; Kainz, M.J.; Li, F.; Gao, W.; Bunn, S.E.; Zhang, Y. The Importance of Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids as High-Quality Food in Freshwater Ecosystems with Implications of Global Change. Biol. Rev. 2024, 99, 200–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukru Bengu, A. The Fatty Acid Composition in Some Economic and Wild Edible Mushrooms in Turkey. Prog. Nutr. 2020, 22, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Lu, Y.; Lu, J.; Yao, T.; Fu, S.; Fan, S.; Ye, L. Comparison of Methods to Produce High-Quality Dried Triploid Fujian Oyster: Hot Air Drying Emerges as a Superior Technique. LWT 2025, 222, 117679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.Y.; Ryu, G.H. Effects of Oyster Mushroom Addition on Quality Characteristics of Full Fat Soy-Based Analog Burger Patty by Extrusion Process. J. Food Process Eng. 2023, 46, e14128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, L.; Tuomainen, P.; Ylinen, M.; Ekholm, P.; Virkki, L. Structural Analysis of Water-Soluble and -Insoluble β-Glucans of Whole-Grain Oats and Barley. Carbohydr. Polym. 2004, 58, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, A.; Gil-González, A.B.; Barjuan Grau, A.; Sardari, R.R.R.; Larsson, O.; Thyagarajan, A.; Hansson, A.; Hernández-Hernández, O.; Olsson, O.; Zambrano, J.A. Macromolecular Characterization of High β-Glucan Oat Lines. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Luo, M.; Liu, F.; Feng, X.; Ibrahim, S.A.; Cheng, L.; Huang, W. Effects of Freeze Drying and Hot-Air Drying on the Physicochemical Properties and Bioactivities of Polysaccharides from Lentinula Edodes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 145, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Törős, G.; Béni, Á.; Peles, F.; Gulyás, G.; Prokisch, J. Comparative Analysis of Freeze-Dried Pleurotus Ostreatus Mushroom Powders on Probiotic and Harmful Bacteria and Its Bioactive Compounds. J. Fungi 2024, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, E.; Goeler-Slough, N.; Cox, A.; Nolden, A. Examination of the Nutritional Composition of Alternative Beef Burgers Available in the United States. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 73, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniyamparambil, S.H.; Salim, M.H.; Al Marzooqi, F.; Mettu, S.; Otoni, C.G.; Banat, F.; Tardy, B.L. A Comprehensive Study on the Potential of Edible Coatings with Polysaccharides, Polyphenol, and Lipids for Mushroom Preservation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 306, 141494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Fish Oil Standard (IFOS). Fish Oil Purity Standars. Available online: http://www.Omegavia.com/best (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Kido, S.; Chosa, E.; Tanaka, R. The Effect of Six Dried and UV-C-Irradiated Mushrooms Powder on Lipid Oxidation and Vitamin D Contents of Fish Meat. Food Chem. 2023, 398, 133917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocine, S.O.; Al-Sawalha, A.-A.B.; Al-Ismail, K. A Study of the Fat Component’s Quality and Quantity and Their Effect on the Oxidative Stability of Beef and Chicken Meat Burgers and Shawarma in Amman Area. RISG Riv. Ital. Sostanze Grasse 2022, 12, 1799–1804. [Google Scholar]

- Ucar, T.M.; Karadag, A. The Effects of Vacuum and Freeze-Drying on the Physicochemical Properties and In Vitro Digestibility of Phenolics in Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus). J. Food Meas. Charact. 2019, 13, 2298–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, H.G.; Eom, T.K.; Jung, W.K.; Kim, S.K. Characterization of Fish Oil Extracted from Fish Processing By-Products. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2008, 13, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fereidoon, S.; Ying, Z. Lipid Oxidation and Improving the Oxidative Stability. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 4067–4079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husein, Y.; Secci, G.; Dinnella, C.; Parisi, G.; Fusi, R.; Monteleone, E.; Zanoni, B. Enhanced Utilisation of Nonmarketable Fish: Physical, Nutritional and Sensory Properties of ‘Clean Label’ Fish Burgers. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 54, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratusz, K.; Symoniuk, E.; Wroniak, M.; Rudzińska, M. Bioactive Compounds, Nutritional Quality and Oxidative Stability of Cold-Pressed Camelina (Camelina sativa L.) Oils. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gałgowska, M.; Pietrzak-Fiećko, R. Evaluation of the Nutritional and Health Values of Selected Polish Mushrooms Considering Fatty Acid Profiles and Lipid Indices. Molecules 2022, 27, 6193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, M.; Adhikari, B. Recent Developments in Frying Technologies Applied to Fresh Foods. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 98, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiné, R.P.F.; Florença, S.G.; Barroca, M.J.; Anjos, O. The Link Between the Consumer and the Innovations in Food Product Development. Foods 2020, 9, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Meenu, M.; Liu, H.; Xu, B. A Concise Review on the Molecular Structure and Function Relationship of β-Glucan. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tocher, D.R. Omega-3 Long-Chain Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Aquaculture in Perspective. Aquaculture 2015, 449, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, S.A.; Zhang, G.; Decker, E.A. Biological Implications of Lipid Oxidation Products. JAOCS J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2017, 94, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sima, P.; Vannucci, L.; Vetvicka, V. β-Glucans and Cholesterol (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 41, 1799–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishak, W.; Maihiza, N.; Raushan, M. The Ability of Oyster Mushroom in Improving Nutritional Composition, β-Glucan and Textural Properties of Chicken Frankfurter. Int. Food Res. J. 2015, 22, 311–317. [Google Scholar]

- Witrowa-Rajchert, D.; Lewicki, P.P. Rehydration Properties of Dried Plant Tissues. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2006, 41, 1040–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Method of Analysis, 18th ed.; Association of Officiating Analytical Chemists: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bligh, E.G.; Dyer, W.J. A Rapid Method of Total Lipid Extraction and Purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 1959, 37, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magazyme Assay Procedure for Mushroom and Yest Beta-Glucan. K-YBGL 02/21. Magazyme. 2021. Available online: https://www.megazyme.com/beta-glucan-assay-kit-yeast-mushroom (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- AOAC. Official Methods and Recommended Practices of the American Oil Chemists Society, 15th ed.; Methods Ce 1b-89, Fatty Acid Composition by GLC, Marine Oil; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Rockville, MD, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- PN EN ISO 3960:2017; Animal and Vegetable Fats and Oils—Determination of Peroxide Value—Iodometric (Visual) Endpoint Determination. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- EN ISO 6885:2016; Animal and Vegetable Fats and Oils—Determination of Anisidine Value. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- EN ISO 660:2020; Animal and Vegetable Fats and Oils. Determination of Acid Value and Acidity. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis; Method 991.39. Fatty Acids in Encapsulated Fish Oils and Fish Oil Methyl and Ethyl Esters; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Rockville, MD, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Ulbricht, T.L.V.; Southgate, D.A.T. Coronary Heart Disease: Seven Dietary Factors. Lancet 1991, 338, 985–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ning, X.; He, X.; Sun, X.; Yu, X.; Cheng, Y.; Yu, R.Q.; Wu, Y. Fatty Acid Composition Analyses of Commercially Important Fish Species from the Pearl River Estuary, China. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Li, Y.; Wen, S.; Sun, Y.; Chen, J.; Gao, Y.; Sagymbek, A.; Yu, X. Analytical Methods for Determining the Peroxide Value of Edible Oils: A Mini-Review. Food Chem. 2021, 358, 129834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- TIBCO Statistica Electronic Manual. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/321061529/STATISTICA-Electronic-Manual (accessed on 14 August 2025).

| Carp Meat | Hot-Air Dried Oyster Mushrooms | Freeze-Dried Oyster Mushrooms | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water | 75.2 ± 0.2 | 13.0 ± 0.8 | 0.6 ± 0.2 |

| Protein | 18.3 ± 0.3 | 22.5 ± 1.3 a | 24.6 ± 1.0 a |

| Lipid | 4.7 ± 0.4 | 0.8 ± 0.1 a | 1.0 ± 0.2 a |

| Ash | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 6.8 ± 0.2 | 7.8 ± 0.2 |

| Carp Meat | Hot-Air Dried Oyster Mushrooms | Freeze-Dried Oyster Mushrooms | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PV [meqO2/kg fat] | 5.1 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0.0 | 1.1 ± 0.2 |

| AsV | 3.2 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 |

| AV [mg KOH/g fat] | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.0 a | 0.3 ± 0.1 a |

| TOTOX | 13.5 ± 0.3 | 3.5 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.2 |

| Fatty Acid | Carp Meat | Hot-Air Dried Oyster Mushrooms | Freeze-Dried Oyster Mushrooms |

|---|---|---|---|

| C10:0 | 0.10 ± 0.00 | - | - |

| C12:0 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.00 a | 0.02 ± 0.01 a |

| C14:0 | 0.04 ± 0.02 a | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.00 a |

| C15:0 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 0.10 ± 0.01 |

| C16:0 | 75.45 ± 0.53 | 3.31 ± 0.20 | 1.96 ± 0.15 |

| C16:1 | 13.74 ± 0.34 | 0.08 ± 0.02 a | 0.08 ± 0.01 a |

| C17:0 | 2.14 ± 0.12 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.01 |

| C17:1 | 0.89 ± 0.09 | - | - |

| C18:0 | 219.96 ± 2.13 | 0.59 ± 0.11 a | 0.48 ± 0.10 a |

| C18:1 ω-9 | 235.28 ± 1.64 | 3.25 ± 0.54 | 4.81 ± 0.48 |

| C18:2 ω-6 | 15.76 ± 0.97 a | 15.05 ± 0.81 a | 18.10 ± 0.32 |

| C20:0 | 0.46 ± 0.10 | - | - |

| C18:3 ω-6 | 0.56 ± 0.09 | - | - |

| C18:3 ω-3 | 2.24 ± 0.16 | 0.07 ± 0.02 a | 0.05 ± 0.01 a |

| C20:1 ω-9 | 1.97 ± 0.04 | 0.06 ± 0.01 a | 0.07 ± 0.02 a |

| C18:4 ω-3 | 1.01 ± 0.06 | - | - |

| C20:2 ω-6 | 3.63 ± 0.06 | - | - |

| C22:0 | 0.28 ± 0.01 | - | - |

| C20:3 ω-6 | 0.42 ± 0.02 | - | - |

| C22:1 ω-9 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | - | - |

| C20:4 ω-6 | 0.76 ± 0.02 | - | - |

| C20:4 ω-3 | 5.44 ± 0.21 | - | - |

| C20:5 ω-3 | 1.21 ± 0.02 | - | - |

| C22:4 ω-6 | 1.01 ± 0.01 | - | - |

| C24:1 ω-9 | 1.12 ± 0.03 | - | - |

| C22:5 ω-6 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | - | - |

| C22:5 ω-3 | 2.32 ± 0.10 | - | - |

| C22:6 ω-3 | 12.30 ± 0.12 | - | - |

| SFA | 298.66 ± 2.92 | 4.22 ± 0.34 | 2.69 ± 0.27 |

| MUFA | 253.04 ± 2.15 | 3.39 ± 0.55 | 4.96 ± 0.51 |

| PUFA | 46.89 ± 1.85 | 15.12 ± 0.85 | 18.15 ± 0.33 |

| Total FA | 598.59 ± 6.92 | 22.73 ± 1.74 | 25.80 ± 1.11 |

| ω-3/ω-6 | 1.10 | - | - |

| C | Fish Burgers with Hot Air-Dried Oyster Mushrooms | Fish Burgers with Freeze-Dried Oyster Mushrooms | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5% | 1.0% | 1.5% | 2.0% | 0.5% | 1.0% | 1.5% | 2.0% | ||

| Water | 65.6 ± 0.1 a | 65.9 ± 0.2 a | 66.5 ± 0.1 a | 68.0 ± 0.2 b | 69.0 ± 0.1 b | 66.7 ± 0.2 a | 68.0 ± 0.1 b | 68.9 ± 0.1 b | 69.7 ± 0.1 b |

| Protein | 18.7 ± 0.2 c | 18.5 ± 0.1 c | 17.8 ± 0.1 b | 16.9 ± 0.1 a | 16.5 ± 0.1 a | 18.6 ± 0.1 c | 18.3 ± 0.1 c | 17.9 ± 0.1 b | 17.1 ± 0.9 a |

| Lipid | 9.7 ± 0.1 d | 9.6 ± 0.1 d | 9.3 ± 0.1 c | 8.9 ± 0.1 c | 8.4 ± 0.1 b | 9.2 ± 0.1 c | 8.3 ± 0.1 b | 8.0 ± 0.2 a | 7.8 ± 0.1 a |

| Ash | 2.8 ± 0.1 a | 2.9 ± 0.1 a | 3.3 ± 0.1 b | 3.6 ± 0.1 | 3.9 ± 0.1 | 2.9 ± 0.1 a | 3.1 ± 0.1 b | 3.2 ± 0.2 b | 3.2 ± 0.2 b |

| C | Fish Burgers with Hot-Air Dried Oyster Mushrooms | Fish Burgers with Freeze-Dried Oyster Mushrooms | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5% | 1.0% | 1.5% | 2.0% | 0.5% | 1.0% | 1.5% | 2.0% | ||

| Total Glucans | 0.60 ± 0.05 | 1.79 ± 0.10 | 1.93 ± 0.13 | 2.06 ± 0.05 | 2.21 ± 0.06 | 4.24 ± 0.06 | 4.51 ± 0.04 | 5.10 ± 0.05 | 5.80 ± 0.08 |

| α-Glucans | 0.02 ± 0.03 a | 0.02 ± 0.02 a | 0.10 ± 0.06 b | 0.11 ± 0.09 b | 0.12 ± 0.08 b | 0.02 ± 0.10 a | 0.06 ± 0.10 ab | 0.09 ± 0.09 b | 0.18 ± 0.06 |

| β-Glucans | 0.58 ± 0.06 | 1.77 ± 0.11 a | 1.83 ± 0.11 a | 1.95 ± 0.06 b | 2.09 ± 0.08 b | 4.22 ± 0.08 | 4.45 ± 0.08 | 5.01 ± 0.06 | 5.62 ± 0.05 |

| C | Fish Burgers with Hot-Air Dried Oyster Mushrooms | Fish Burgers with Freeze-Dried Oyster Mushrooms | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5% | 1.0% | 1.5% | 2.0% | 0.5% | 1.0% | 1.5% | 2.0% | ||

| TOTOX | 27.01 ± 0.03 b | 27.2 ± 0.1 b | 25.7 ± 0.2 a | 24.9 ± 0.0 a | 24.2 ± 0.1 a | 26.4 ± 0.0 b | 24.6 ± 0.2 a | 23.0 ± 0.0 | 21.0 ± 0.0 |

| C | Fish Burgers with Hot-Air Dried Oyster Mushrooms | Fish Burgers with Freeze-Dried Oyster Mushrooms | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5% | 1.0% | 1.5% | 2.0% | 0.5% | 1.0% | 1.5% | 2.0% | ||

| C10:0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| C12:0 | 0.03 ± 0.01 a | 0.04 ± 0.01 a | 0.02 ± 0.01 a | 0.05 ± 0.02 a | 0.05 ± 0.02 a | 0.04 ± 0.01 a | 0.03 ± 0.01 a | 0.04 ± 0.00 a | 0.03 ± 0.00 a |

| C14:0 | 4.31 ± 0.02 c | 4.18 ± 0.04 c | 3.73 ± 0.04 b | 3.38 ± 0.01 b | 3.00 ± 0.03 a | 2.32 ± 0.02 | 4.31 ± 0.02 c | 4.69 ± 0.05 | 2.91 ± 0.05 a |

| C15:0 | 0.39 ± 0.03 a | 0.44 ± 0.01 a | 0.36 ± 0.03 a | 0.31 ± 0.01 a | 0.28 ± 0.05 a | 0.22 ± 0.02 a | 0.39 ± 0.03 a | 0.46 ± 0.02 a | 0.32 ± 0.03 a |

| C16:0 | 98.64 ± 0.04 b | 96.05 ± 0.01 a | 95.59 ± 0.02 a | 98.08 ± 0.00 b | 99.27 ± 0.02 b | 99.28 ± 0.03 b | 98.64 ± 0.04 b | 96.02 ± 0.03 a | 98.58 ± 0.02 b |

| C16:1 | 10.44 ± 0.02 b | 11.57 ± 0.01 c | 9.35 ± 0.06 | 8.26 ± 0.02 a | 8.30 ± 0.02 a | 8.68 ± 0.02 a | 10.44 ± 0.02 b | 11.81 ± 0.02 c | 10.92 ± 0.03 b |

| C17:0 | 1.23 ± 0.01 b | 1.34 ± 0.00 b | 1.12 ± 0.05 b | 0.96 ± 0.03 a | 0.82 ± 0.01 a | 0.58 ± 0.01 | 1.23 ± 0.01 b | 1.37 ± 0.02 b | 0.95 ± 0.04 a |

| C17:1 | 1.23 ± 0.00 c | 1.08 ± 0.00 b | 0.90 ± 0.01 b | 0.58 ± 0.02 a | 0.65 ± 0.01 a | 0.49 ± 0.00 a | 1.23 ± 0.00 b | 1.11 ± 0.01 c | 0.85 ± 0.01 b |

| C18:0 | 61.64 ± 0.01 b | 66.45 ± 0.02 | 59.71 ± 0.04 a | 55.60 ± 0.04 | 57.05 ± 0.09 a | 59.88 ± 0.00 c | 61.64 ± 0.01 b | 60.29 ± 0.09 a | 60.40 ± 0.01 a |

| C18:1 ω9 | 279.76 ± 0.0 a | 278.75 ± 0.02 a | 295.00 ± 0.02 b | 293.46 ± 0.05 b | 295.90 ± 0.01 b | 295.52 ± 0.01 b | 299.76 ± 0.0 b | 296.31 ± 0.04 b | 298.84 ± 0.00 b |

| C18:2 ω6 | 85.27 ± 0.06 | 97.12 ± 0.03 | 99.89 ± 0.03 | 94.10 ± 0.07 b | 95.10 ± 0.01 b | 94.42 ± 0.02 b | 95.27 ± 0.06 b | 90.66 ± 0.04 a | 90.30 ± 0.00 a |

| C20:0 | 2.37 ± 0.05 b | 3.27 ± 0.04 | 2.22 ± 0.03 b | 1.89 ± 0.06 a | 1.75 ± 0.00 a | 1.40 ± 0.03 | 2.37 ± 0.05 b | 2.70 ± 0.02 c | 2.75 ± 0.00 c |

| C18:3 ω6 | 0.76 ± 0.03 b | 0.43 ± 0.04 a | 0.85 ± 0.03 b | 0.93 ± 0.06 c | 1.00 ± 0.00 c | 0.96 ± 0.04 c | 0.76 ± 0.03 b | 0.32 ± 0.01 a | 0.38 ± 0.07 a |

| C18:3 ω3 | 14.62 ± 0.03 a | 25.13 ± 0.05 | 18.15 ± 0.05 b | 19.90 ± 0.02 c | 19.67 ± 0.01 c | 17.68 ± 0.04 b | 14.62 ± 0.03 a | 20.51 ± 0.00 c | 18.57 ± 0.08 b |

| C20:1 ω9 | 10.76 ± 0.02 a | 12.81 ± 0.01 | 10.51 ± 0.01 a | 9.86 ± 0.01 | 10.31 ± 0.03 a | 10.96 ± 0.05 a | 10.76 ± 0.02 a | 11.02 ± 0.00 b | 11.22 ± 0.06 b |

| C18:4 ω3 | 0.27 ± 0.02 a | 0.41 ± 0.02 b | 0.30 ± 0.05 a | 0.29 ± 0.01 a | 0.28 ± 0.04 a | 0.25 ± 0.05 a | 0.27 ± 0.02 a | 0.37 ± 0.02 b | 0.31 ± 0.05 a |

| C20:2 ω6 | 2.01 ± 0.01 a | 2.33 ± 0.01 b | 2.19 ± 0.00 a | 2.19 ± 0.00 a | 4.23 ± 0.02 c | 4.08 ± 0.02 c | 2.01 ± 0.01 a | 2.14 ± 0.04 a | 2.33 ± 0.05 b |

| C22:0 | 0.71 ± 0.01 c | 1.21 ± 0.01 d | 0.52 ± 0.02 ab | 0.47 ± 0.03 a | 0.42 ± 0.03 a | 0.24 ± 0.01 | 0.71 ± 0.01 c | 0.53 ± 0.03 b | 0.63 ± 0.02 bc |

| C20:3 ω6 | 1.36 ± 0.01 b | 1.62 ± 0.03 c | 1.36 ± 0.03 b | 1.33 ± 0.02 b | 1.13 ± 0.05 a | 2.24 ± 0.00 d | 1.36 ± 0.01 b | 1.50 ± 0.03 c | 1.23 ± 0.02 ab |

| C22:1 ω9 | 0.59 ± 0.02 b | 1.51 ± 0.02 | 0.51 ± 0.04 ab | 0.48 ± 0.02 a | 0.45 ± 0.05 a | 0.43 ± 0.02 a | 0.59 ± 0.02 b | 1.26 ± 0.01 c | 1.20 ± 0.01 c |

| C20:4 ω6 | 4.54 ± 0.02 c | 5.04 ± 0.04 | 4.41 ± 0.02 c | 3.20 ± 0.01 ab | 2.91 ± 0.01 a | 1.94 ± 0.02 | 4.54 ± 0.02 c | 4.49 ± 0.03 c | 3.50 ± 0.06 b |

| C20:4 ω3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| C20:5 ω3 | 0.68 ± 0.01 b | 0.74 ± 0.01 | 0.65 ± 0.07 b | 0.59 ± 0.01 b | 0.49 ± 0.04 ab | 0.41 ± 0.03 a | 0.68 ± 0.01 b | 0.69 ± 0.02 b | 0.53 ± 0.03 a |

| C24:1 ω9 | 0.32 ± 0.03 b | 0.61 ± 0.02 | 0.38 ± 0.09 b | 0.32 ± 0.00 b | 0.27 ± 0.02 a | 0.19 ± 0.05 a | 0.32 ± 0.03 b | 0.30 ± 0.09 ab | 0.29 ± 0.03 a |

| C22:4 ω6 | 0.43 ± 0.01 a | 0.68 ± 0.04 | 0.51 ± 0.05 a | 0.49 ± 0.07 a | 0.46 ± 0.02 a | 0.44 ± 0.01 a | 0.43 ± 0.01 a | 0.48 ± 0.03 a | 0.40 ± 0.03 a |

| C22:5 ω6 | 0.63 ± 0.02 b | 0.76 ± 0.02 | 0.60 ± 0.02 ab | 0.53 ± 0.08 a | 0.42 ± 0.01 | 0.32 ± 0.02 | 0.63 ± 0.02 b | 0.68 ± 0.04 b | 0.59 ± 0.02 a |

| C22:5 ω3 | 0.62 ± 0.03 b | 0.74 ± 0.02 | 0.61 ± 0.01 b | 0.57 ± 0.05 b | 0.53 ± 0.00 ab | 0.45 ± 0.03 a | 0.62 ± 0.03 b | 0.57 ± 0.05 b | 0.46 ± 0.01 a |

| C22:6 ω3 | 4.58 ± 0.03 a | 4.81 ± 0.00 | 4.41 ± 0.00 a | 3.12 ± 0.02 | 2.81 ± 0.01 | 2.05 ± 0.02 | 4.58 ± 0.03 a | 4.22 ± 0.05 | 4.05 ± 0.00 |

| SFA | 28.81 ± 0.14 | 27.96 ± 0.40 | 26.61 ± 0.31 a | 26.96 ± 0.13 a | 26.78 ± 0.15 a | 27.08 ± 0.10 b | 27.38 ± 0.14 b | 27.07 ± 0.59 b | 27.11 ± 0.60 b |

| MUFA | 51.51 ± 0.65 a | 49.46 ± 0.51 | 51.58 ± 0.24 a | 51.69 ± 0.16 a | 51.97 ± 0.49 a | 52.24 ± 0.51 b | 52.27 ± 0.25 b | 52.46 ± 0.61 b | 52.61 ± 0.22 b |

| PUFA | 19.68 ± 0.26 a | 22.58 ± 0.15 | 21.82 ± 0.15 c | 21.35 ± 0.37 c | 21.25 ± 0.12 c | 20.68 ± 0.60 b | 20.35 ± 0.66 b | 20.47 ± 0.22 b | 20.23 ± 0.43 ab |

| Total FA | 588.37 ± 5.30 | 619.31 ± 5.84 b | 613.96 ± 3.28 b | 610.21 ± 3.82 a | 607.78 ± 3.04 a | 605.59 ± 4.92 a | 618.37 ± 5.10 b | 615.55 ± 4.93 b | 614.36 ± 5.51 b |

| ω3/ω6 | 0.22 | 0.29 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.26 | 0.24 |

| DHA/EPA | 6.73 | 6.51 | 6.81 | 5.28 | 5.69 | 5.01 | 6.73 | 6.14 | 7.64 |

| AI | 0.38 | 0.18 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.34 |

| TI | 0.63 | 0.55 | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.59 | 0.60 | 0.55 | 0.57 |

| PUFA/SFA | 0.68 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.76 | 0.74 | 0.76 | 0.75 |

| HPI | 2.61 | 2.71 | 2.86 | 3.08 | 3.09 | 3.11 | 3.14 | 3.20 | 3.18 |

| HH | 3.79 | 4.11 | 4.26 | 4.09 | 4.08 | 4.06 | 4.08 | 4.15 | 4.10 |

| FLQ | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.82 | 0.61 | 0.54 | 0.41 | 0.85 | 0.80 | 0.75 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tokarczyk, G.; Felisiak, K.; Adamska, I.; Przybylska, S.; Hrebień-Filisińska, A.; Biernacka, P.; Bienkiewicz, G.; Tabaszewska, M.; Bernaś, E.; Arroyos, E.L. Impact of Drying Methods on β-Glucan Retention and Lipid Stability in Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) Enriched Carp (Cyprinus carpio, L.) Fish Burgers. Molecules 2025, 30, 4649. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234649

Tokarczyk G, Felisiak K, Adamska I, Przybylska S, Hrebień-Filisińska A, Biernacka P, Bienkiewicz G, Tabaszewska M, Bernaś E, Arroyos EL. Impact of Drying Methods on β-Glucan Retention and Lipid Stability in Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) Enriched Carp (Cyprinus carpio, L.) Fish Burgers. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4649. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234649

Chicago/Turabian StyleTokarczyk, Grzegorz, Katarzyna Felisiak, Iwona Adamska, Sylwia Przybylska, Agnieszka Hrebień-Filisińska, Patrycja Biernacka, Grzegorz Bienkiewicz, Małgorzata Tabaszewska, Emilia Bernaś, and Eire López Arroyos. 2025. "Impact of Drying Methods on β-Glucan Retention and Lipid Stability in Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) Enriched Carp (Cyprinus carpio, L.) Fish Burgers" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4649. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234649

APA StyleTokarczyk, G., Felisiak, K., Adamska, I., Przybylska, S., Hrebień-Filisińska, A., Biernacka, P., Bienkiewicz, G., Tabaszewska, M., Bernaś, E., & Arroyos, E. L. (2025). Impact of Drying Methods on β-Glucan Retention and Lipid Stability in Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) Enriched Carp (Cyprinus carpio, L.) Fish Burgers. Molecules, 30(23), 4649. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234649