Plasmon-Enhanced Piezo-Photocatalytic Degradation of Metronidazole Using Ag-Decorated ZnO Microtetrapods

Abstract

1. Introduction

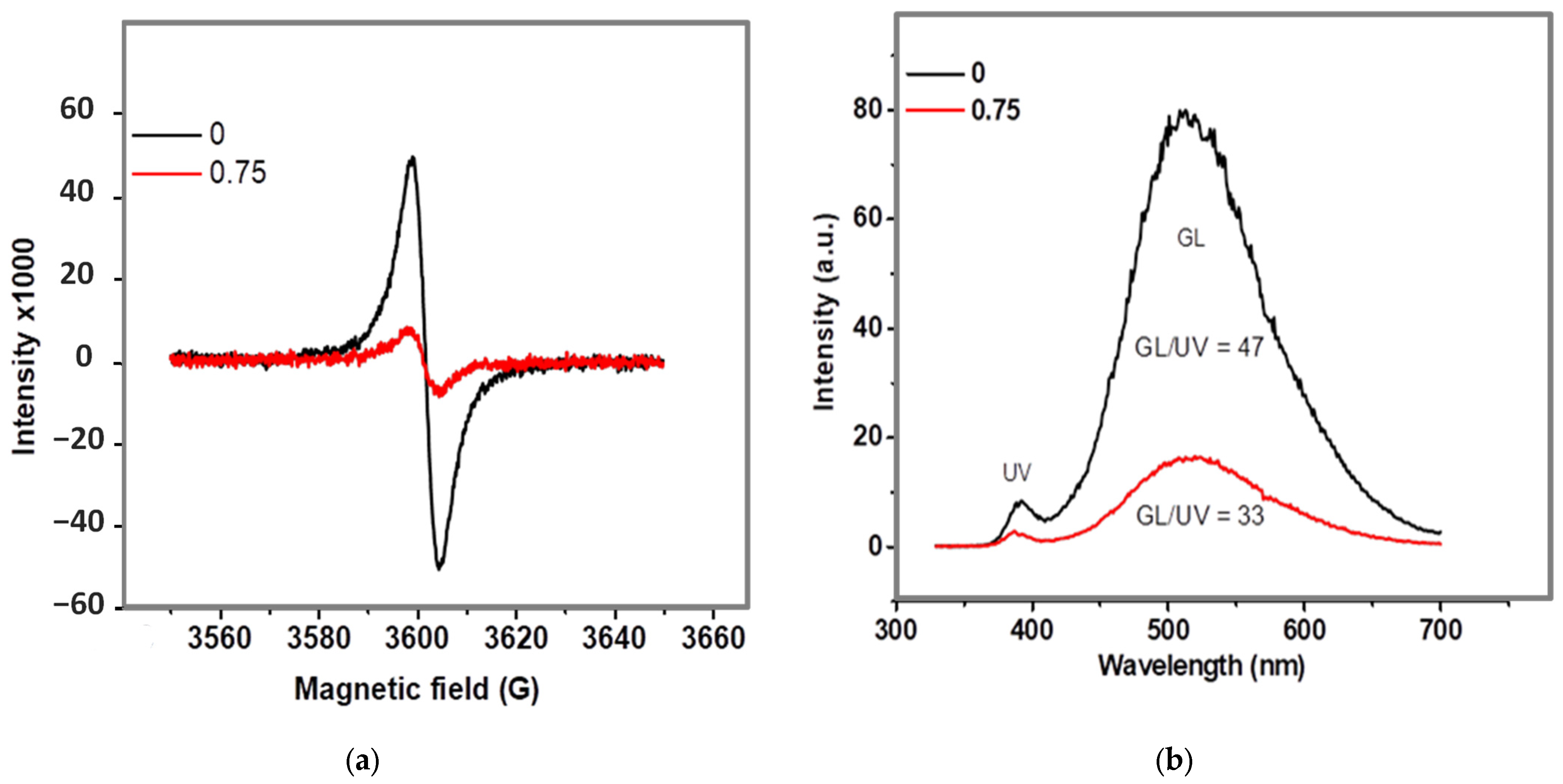

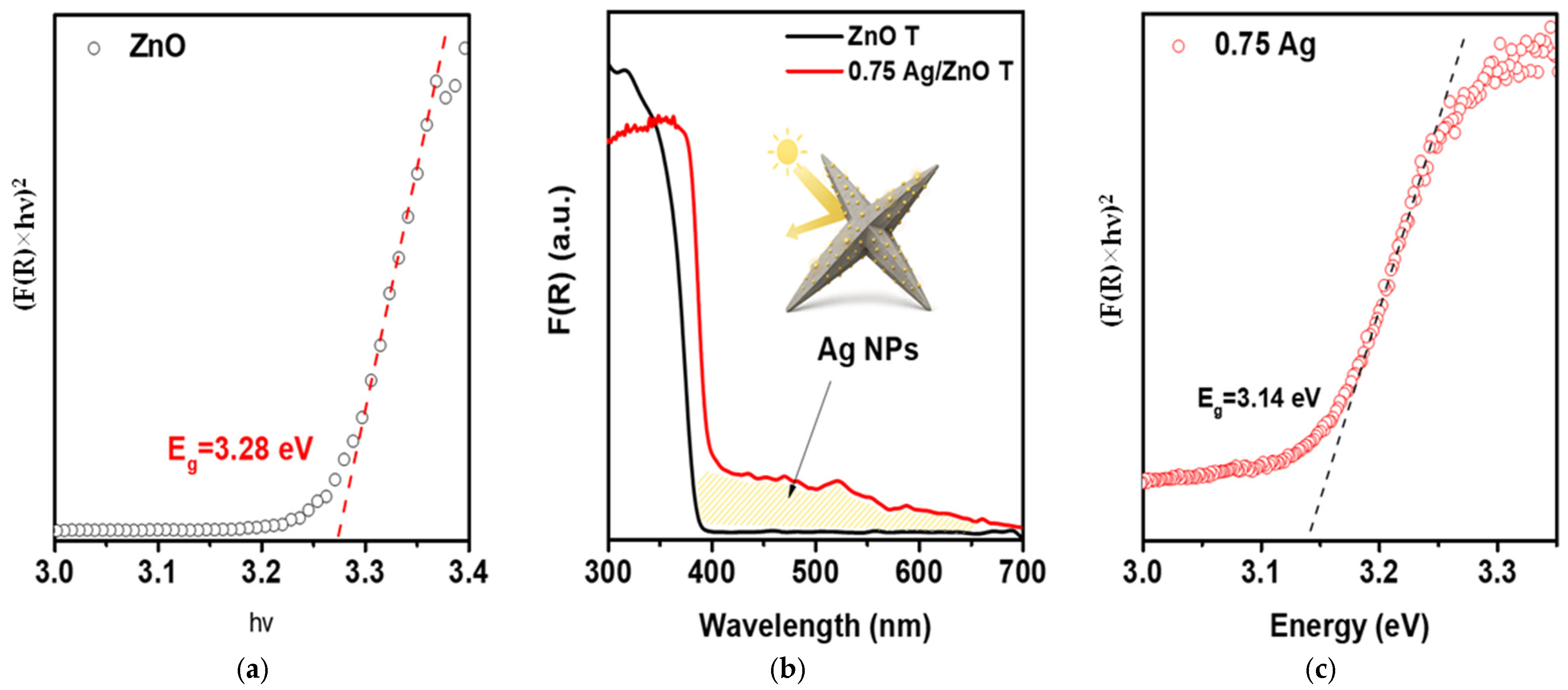

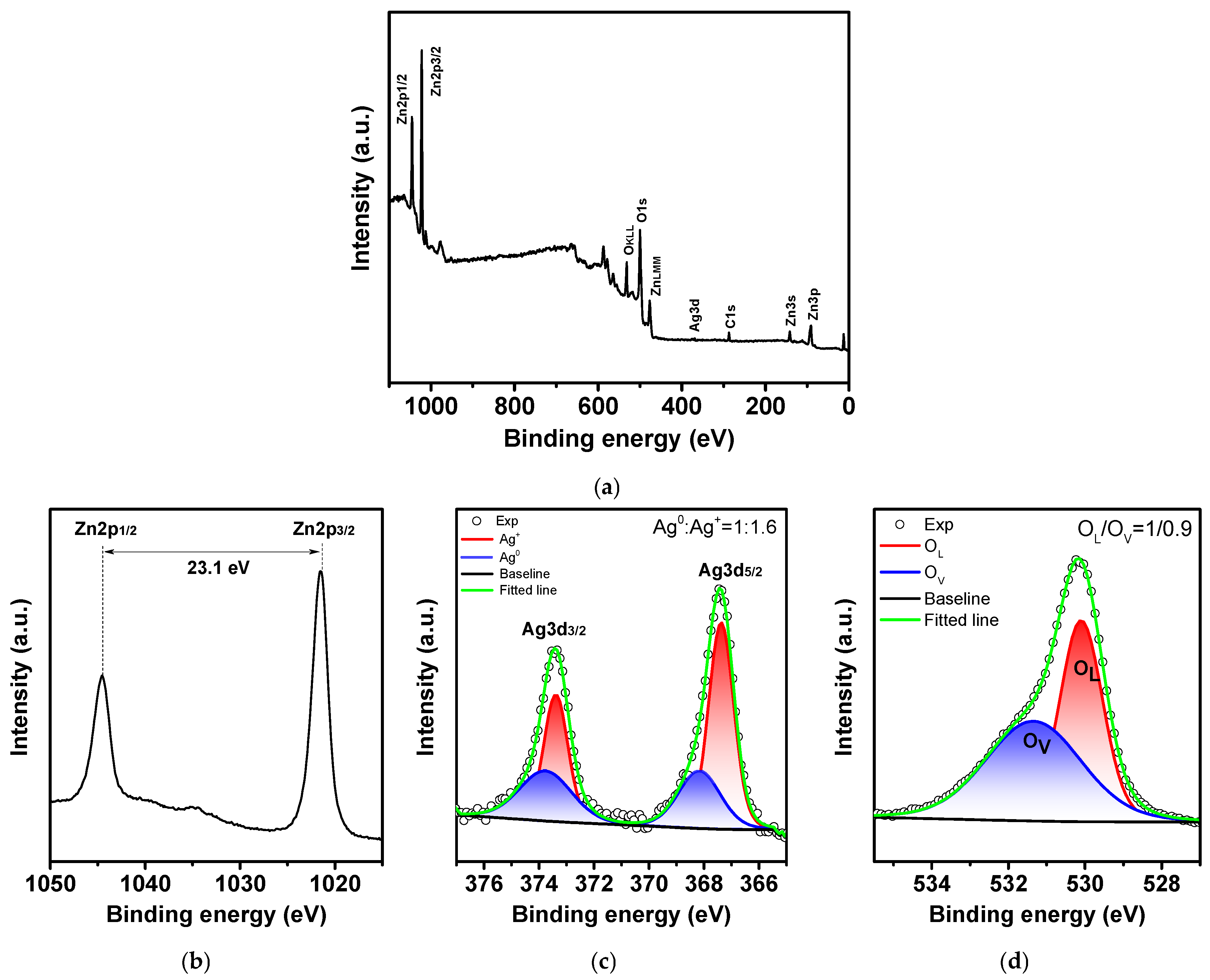

2. Results

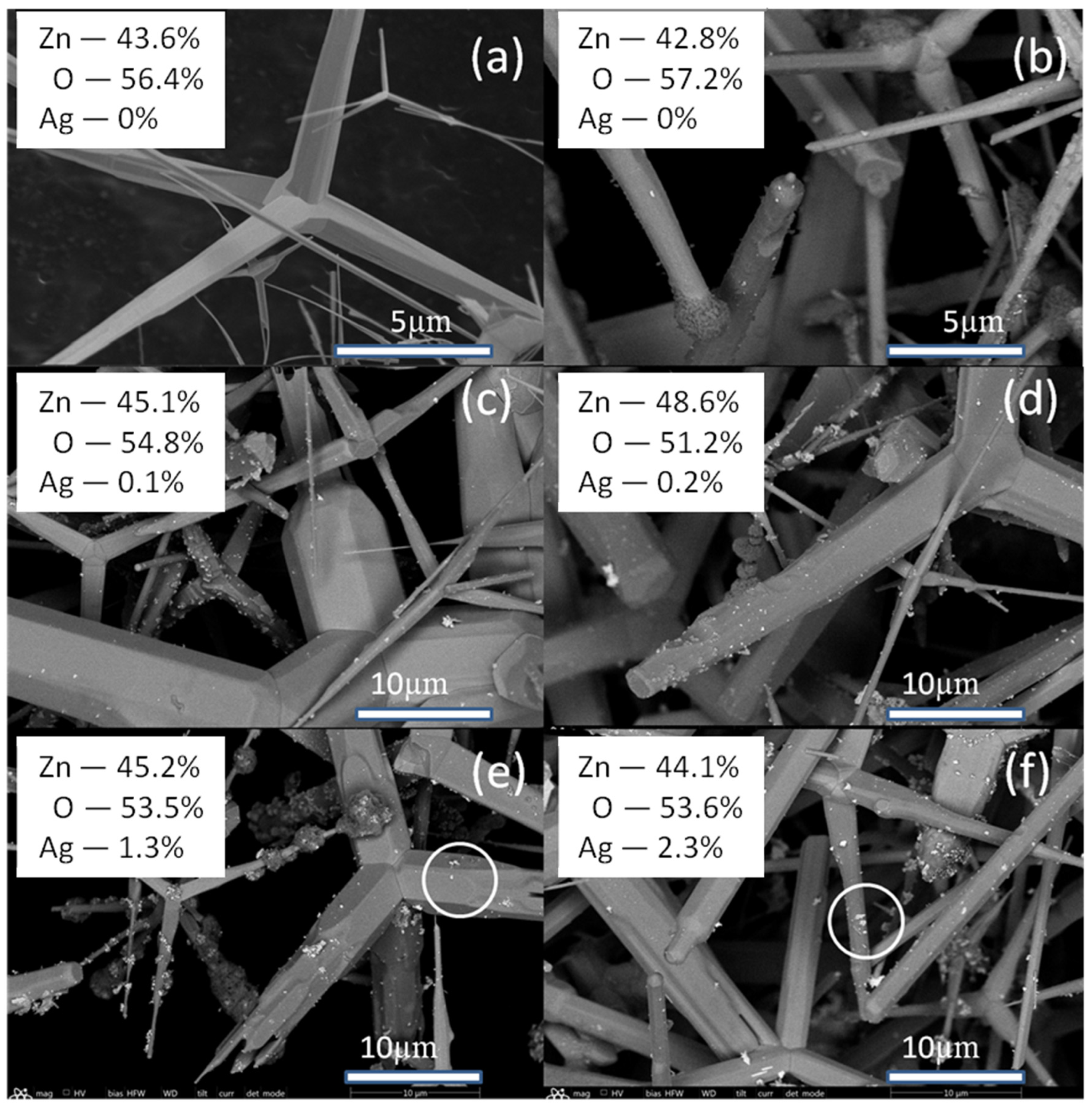

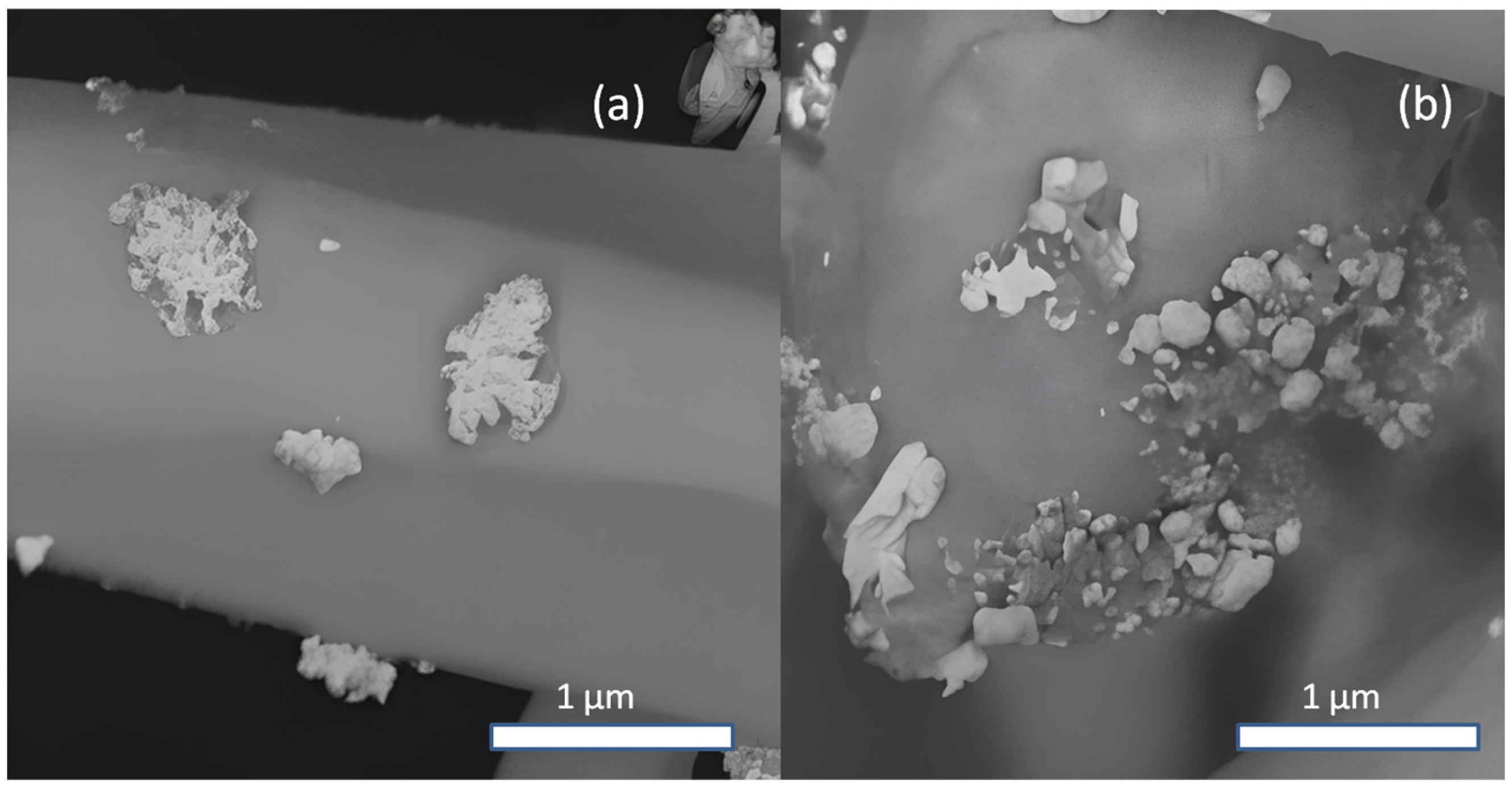

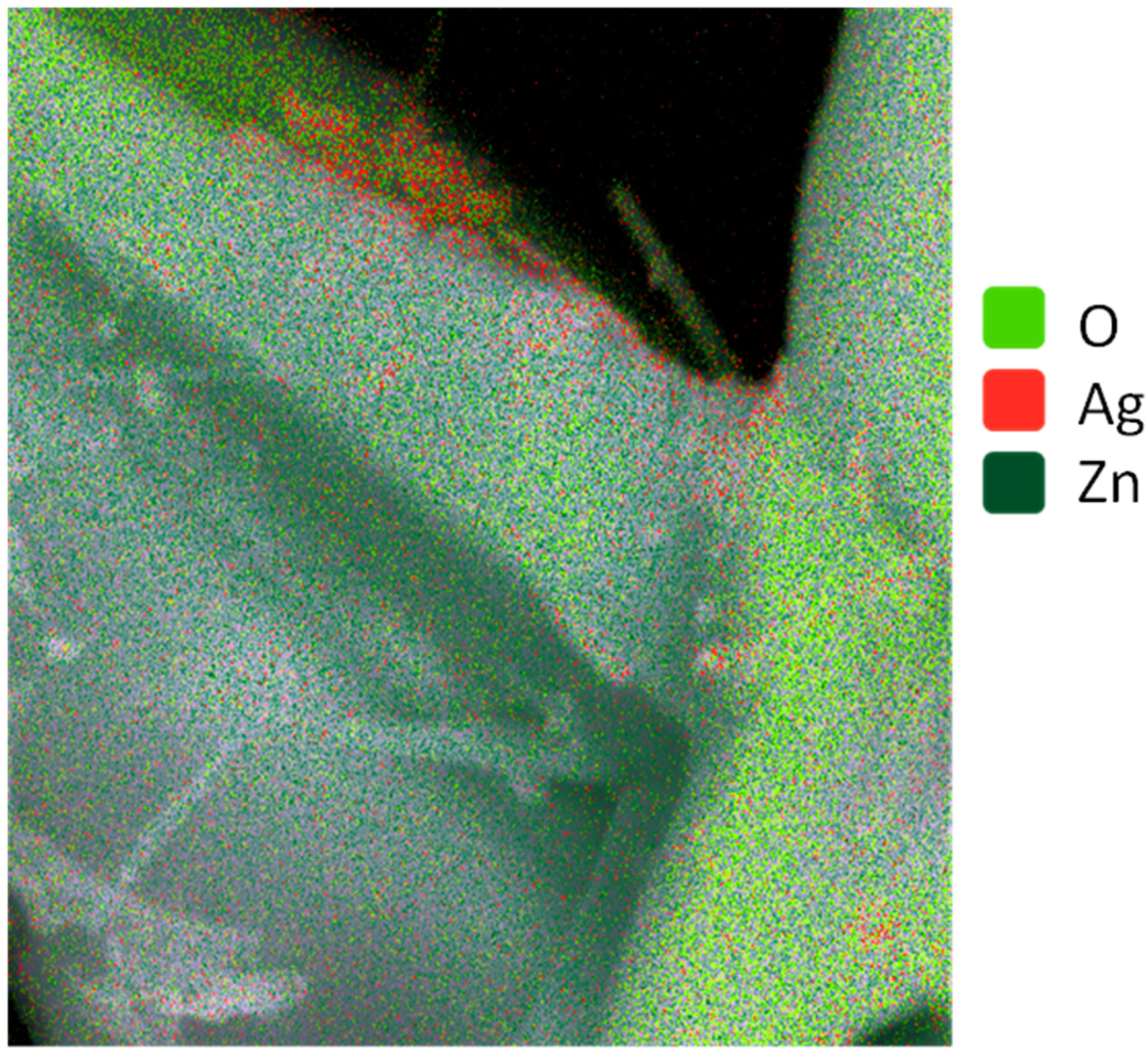

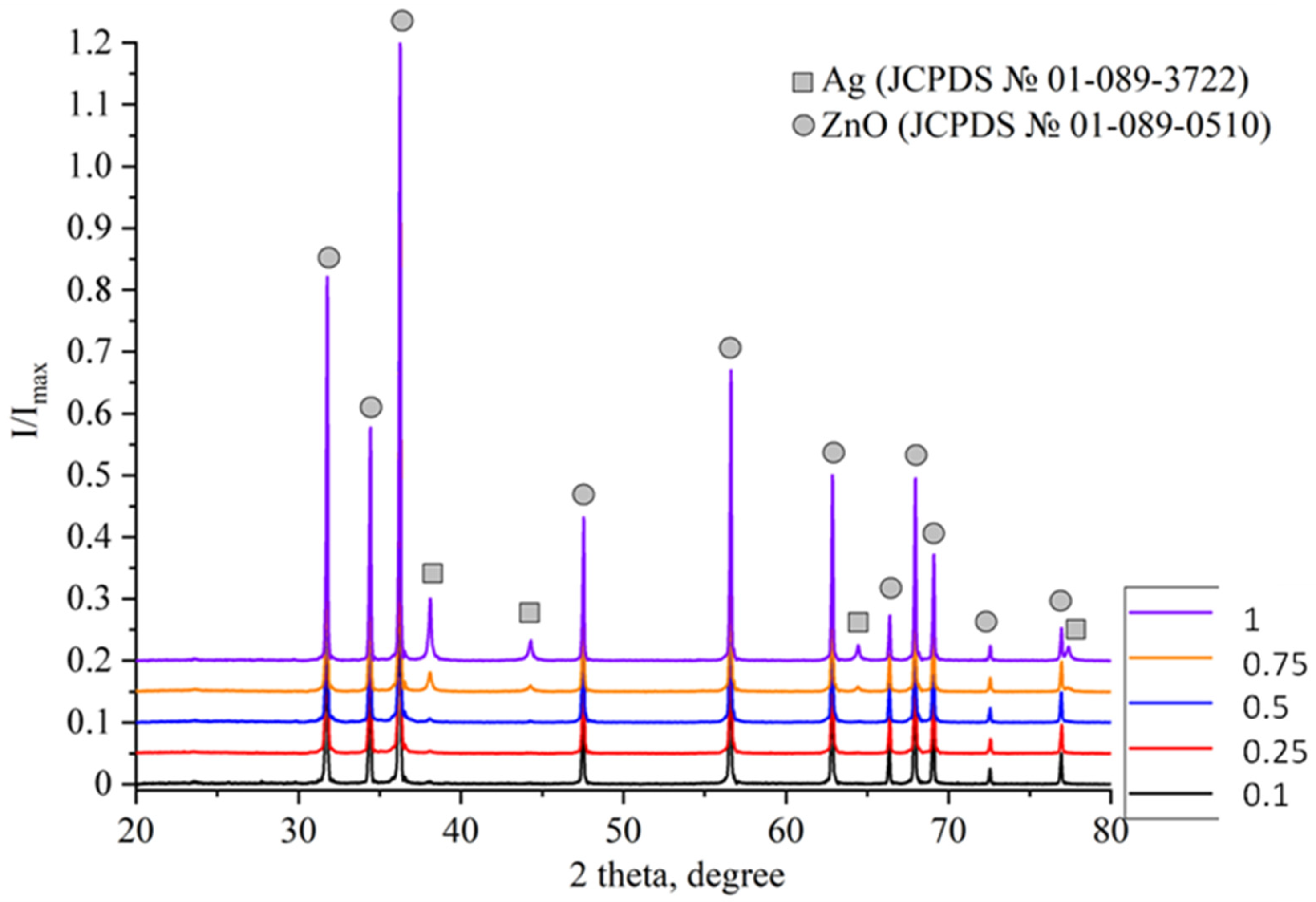

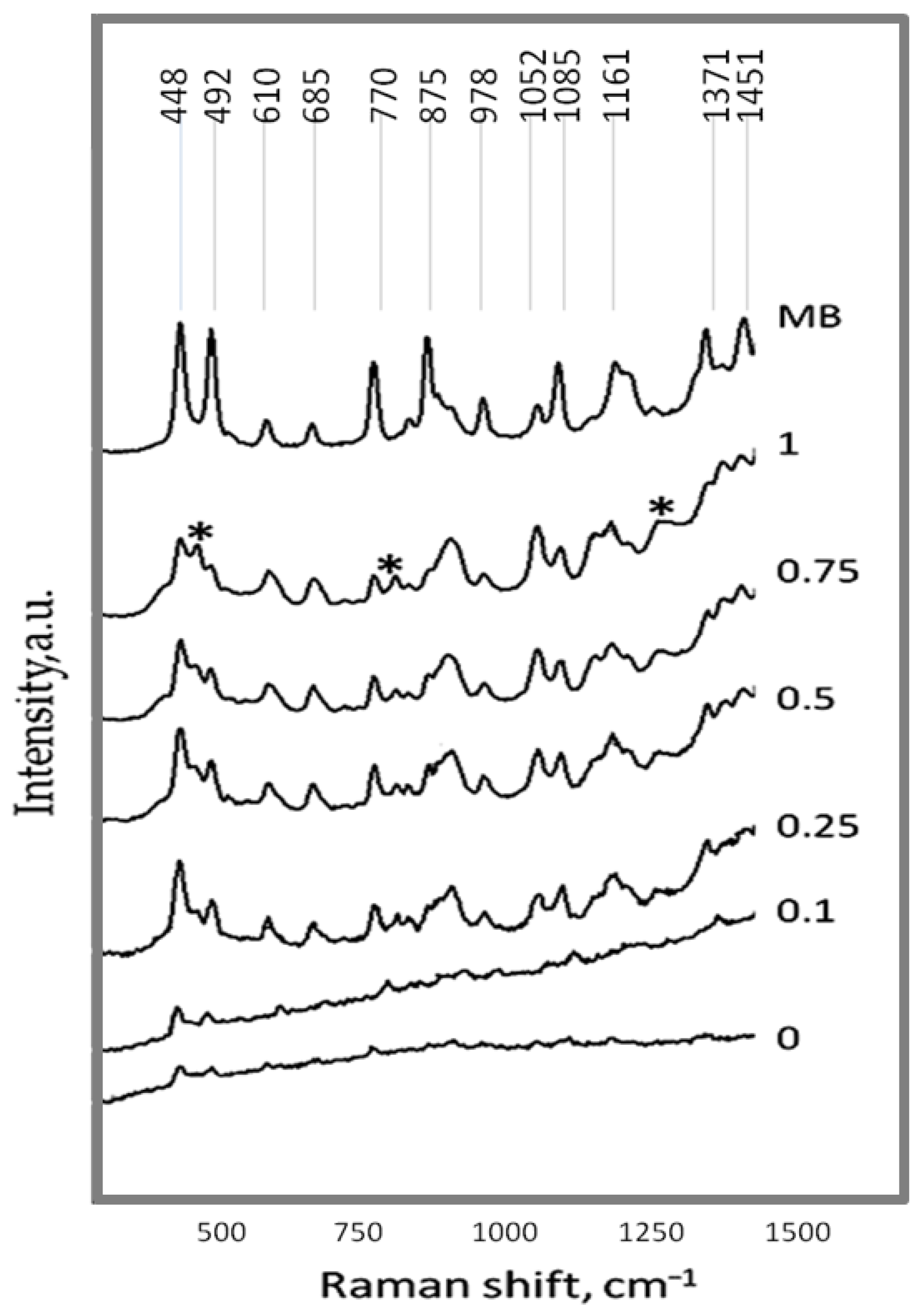

2.1. Study of Morphology, Elemental, and Structural-Phase Compositions of Ag/ZnO Tetrapods

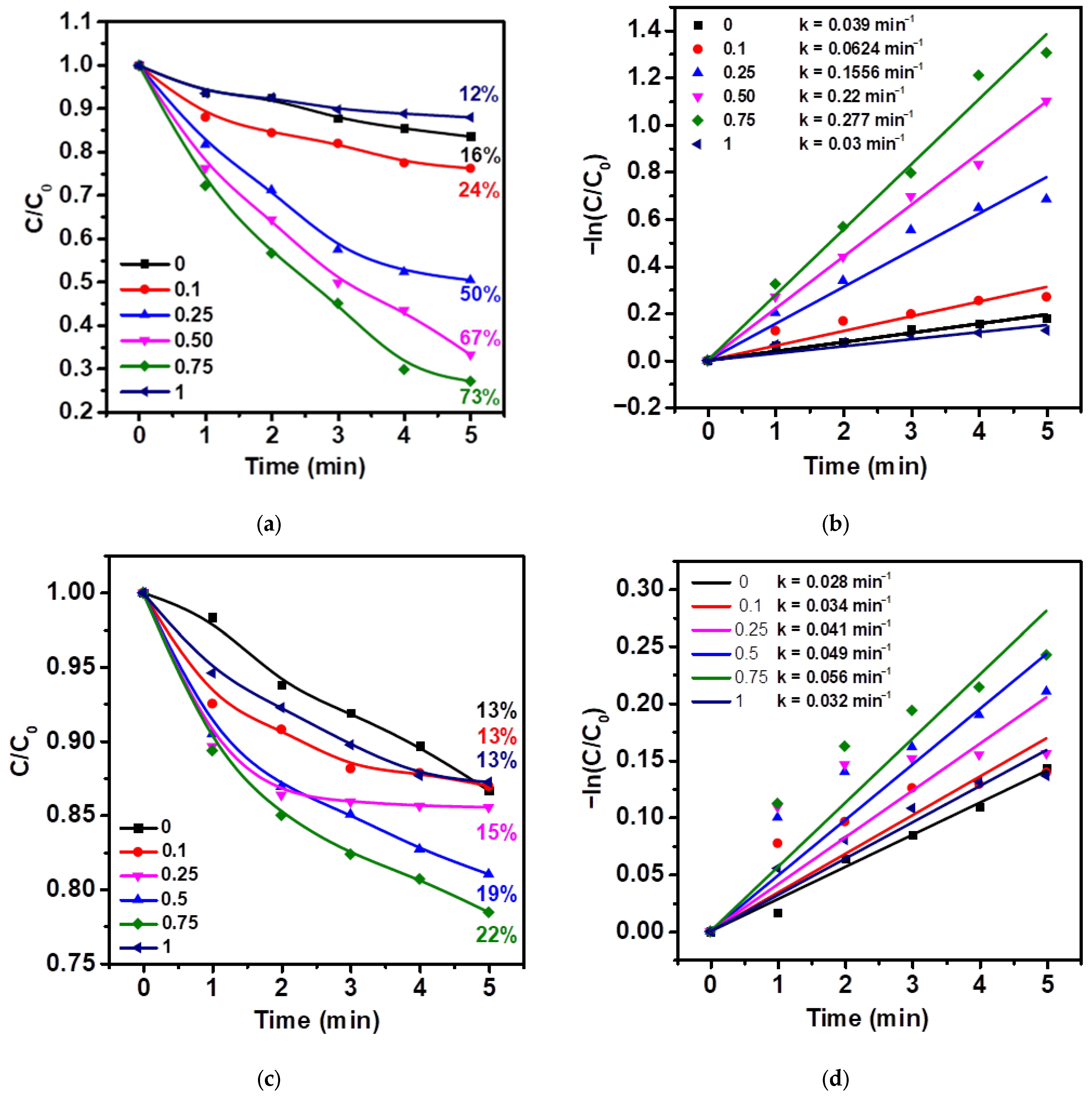

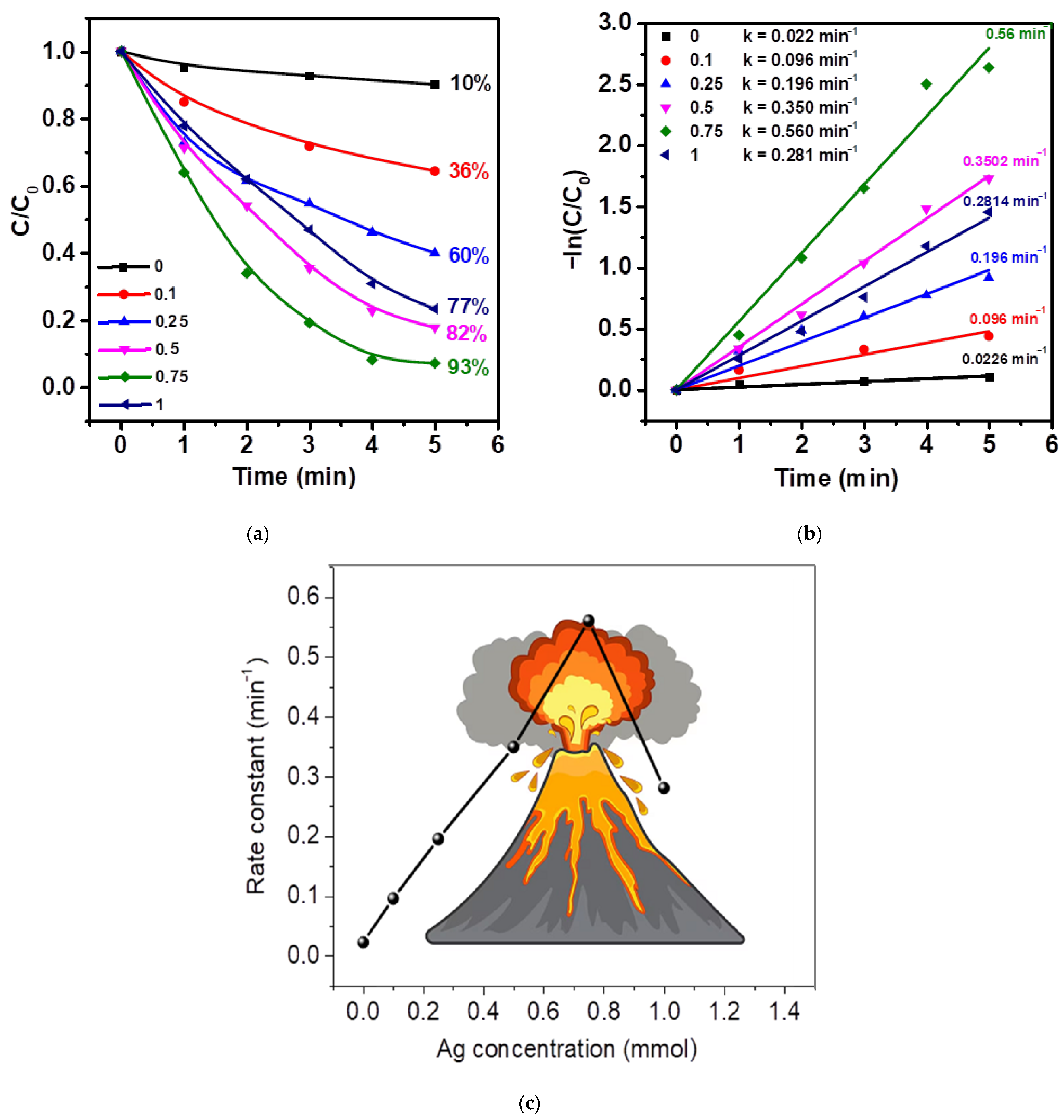

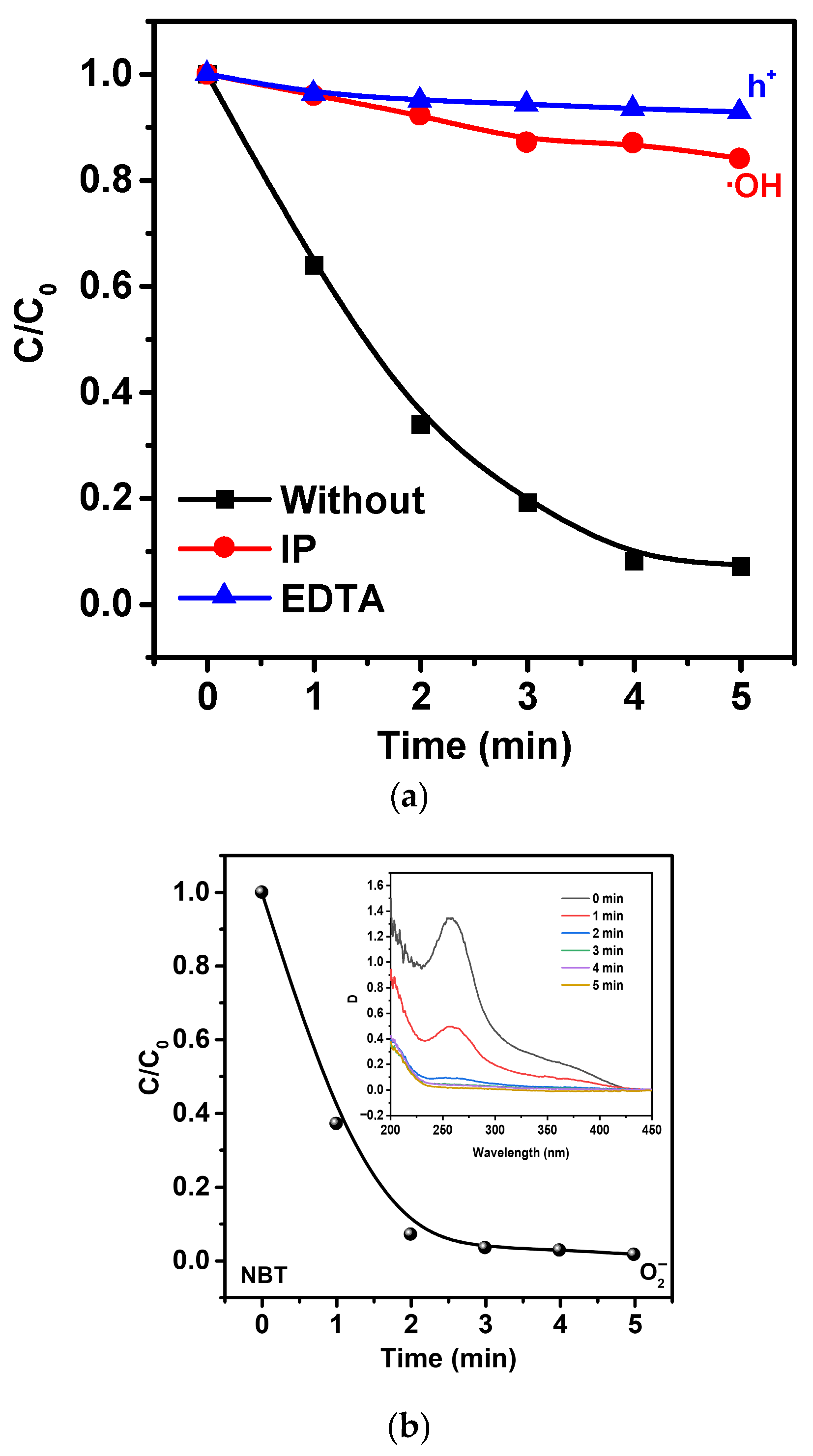

2.2. Study of Photocatalytic, Piezocatalytic, and Piezo-Photocatalytic Properties of Ag/ZnO Tetrapods

- Formation of a Schottky barrier at the ZnO/Ag interface, where Ag acts as an electron sink, suppressing charge recombination.

- Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) of Ag nanoparticles, which promotes additional electron excitation and the injection of “hot” electrons into the ZnO conduction band.

Ag + hν → Ag(LSPR) → Ag(ehot−)

Ag(ehot−) → eCB(ZnO)− + Ag

hVB+ + H2O → •OH + H+

hVB+ + OH− → •OH

•O2− + MNZ → oxidized intermediates

hVB+ + MNZ → MNZ+ → further oxidation

3. Materials and Methods

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bryche, J.-F.; Vega, M.; Tempez, A.; Brulé, T.; Carlier, T.; Moreau, J.; Chaigneau, M.; Charette, P.G.; Canva, M. Spatially-Localized Functionalization on Nanostructured Surfaces for Enhanced Plasmonic Sensing Efficacy. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fomin, V.M.; Marquardt, O. Topology- and Geometry-Controlled Functionalization of Nanostructured Metamaterials. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, D.; Reif, J. 3D DNA Nanostructures: The Nanoscale Architect. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombelli, A.; Lospinoso, D.; Rella, R.; Manera, M.G. Shape Modulation of Plasmonic Nanostructures by Unconventional Lithographic Technique. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Gao, M.; Ban, R.; Chen, H.; Wang, X.; Qian, L.; Li, J.; Yang, Z. Spatially-Controllable Hot Spots for Plasmon-Enhanced Second-Harmonic Generation in AgNP-ZnO Nanocavity Arrays. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnova, V.V.; Muslimov, A.E.; Lavrikov, A.S.; Zadorozhnaya, L.A.; Orudzhev, F.F.; Gulakhmedov, R.R.; Kanevsky, V.M. Characterization and Photocatalytic Properties of ZnO Tetrapods Synthesized by High-Temperature Pyrolysis. Crystallogr. Rep. 2024, 69, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terracciano, M.; Račkauskas, S.; Falanga, A.P.; Martino, S.; Chianese, G.; Greco, F.; Piccialli, G.; Viscardi, G.; De Stefano, L.; Oliviero, G.; et al. ZnO Tetrapods for Label-Free Optical Biosensing: Physicochemical Characterization and Functionalization Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobedo-Morales, A.; Aranda-García, R.J.; Chigo-Anota, E.; Pérez-Centeno, A.; Méndez-Blas, A.; Arana-Toro, C.G. ZnO Micro- and Nanostructures Obtained by Thermal Oxidation: Microstructure, Morphogenesis, Optical, and Photoluminescence Properties. Crystals 2016, 6, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orudzhev, F.; Gadzhiev, M.; Abdulkerimov, M.; Muslimov, A.; Krasnova, V.; Il’ichev, M.; Kanevsky, V. Plasma-Assisted Synthesis of TiO2/ZnO Heterocomposite Microparticles: Phase Composition, Surface Chemistry, and Photocatalytic Performance. Molecules 2025, 30, 3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamberti, A. ZnO- and TiO2-Based Nanostructures. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujara, A.; Sharma, R.; Samriti; Bechelany, M.; Mishra, Y.K.; Prakash, J. Novel zinc oxide 3D tetrapod nano-microstructures: Recent progress in synthesis, modification and tailoring of optical properties for photocatalytic applications. Mater. Adv. 2025, 6, 2123–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ushanov, V.I.; Eremeev, S.V.; Silkin, V.M.; Chaldyshev, V.V. Plasmon Resonance in a System of Bi Nanoparticles Embedded into (Al,Ga)As Matrix. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Zhan, D.; Wang, D.; Han, C.; Fu, Q.; Zhu, H.; Mao, Z.; Liu, Z.-Q. Surface Plasmon Resonance Effect of Noble Metal (Ag and Au) Nanoparticles on BiVO4 for Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting. Inorganics 2023, 11, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Wang, K.; Liu, W.; Song, Y.; Zheng, R.; Chen, L.; Su, B. Hot Electrons Induced by Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance in Ag/g-C3N4 Schottky Junction for Photothermal Catalytic CO2 Reduction. Polymers 2024, 16, 2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busila, M.; Musat, V.; Alexandru, P.; Romanitan, C.; Brincoveanu, O.; Tucureanu, V.; Mihalache, I.; Iancu, A.-V.; Dediu, V. Antibacterial and Photocatalytic Activity of ZnO/Au and ZnO/Ag Nanocomposites. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.-T.; Lu, Y.-C.; Tangsuwanjinda, S.; Chung, R.-J.; Sakthivel, R.; Cheng, H.-M. Irradiation-Induced Synthesis of Ag/ZnO Nanostructures as Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering Sensors for Sensitive Detection of the Pesticide Acetamiprid. Sensors 2022, 22, 6406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orudzhev, F.; Sobola, D.; Ramazanov, S.; Částková, K.; Papež, N.; Selimov, D.A.; Abdurakhmanov, M.; Shuaibov, A.; Rabadanova, A.; Gulakhmedov, R.; et al. Piezo-Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity of the Electrospun Fibrous Magnetic PVDF/BiFeO3 Membrane. Polymers 2023, 15, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.; Wang, P.; Lv, Y.; Dong, L.; Li, L.; Xu, M.; Fu, L.; Yue, B.; Yu, D. Piezo-Photocatalytic Degradation of Ciprofloxacin Based on Flexible BiVO4 PVDF Nanofibers Membrane. Catalysts 2025, 15, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Dong, C.; Chen, X.; Cai, H.; Chen, X.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, A.; Badsha, M.A.H. Review of Piezocatalysis and Piezo-Assisted Photocatalysis in Environmental Engineering. Crystals 2023, 13, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selimov, D.A.; Sobola, D.; Shuaibov, A.; Schubert, R.; Gulakhmedov, R.; Rabadanova, A.; Orudzhev, F. Coupling Photocatalysis and Piezocatalysis in PVDF/ZnO Nanofiber Composites for Efficient Dye Degradation. Chim. Techno Acta 2025, 12, 12216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selimov, D.A.; Rabadanova, A.A.; Shuaibov, A.O.; Magomedova, A.G.; Abdurakhmanov, M.G.; Gulakhmedov, R.R.; Orudzhev, F.F. Piezo-Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity of BaTiO3-Doped Polyvinylidene Fluoride Nanofibers. Kinet. Catal. 2024, 65, 682–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuaibov, A.O.; Abdurakhmanov, M.G.; Magomedova, A.G.; Omelyanchik, A.; Salnikov, V.; Aga-Tagieva, S.; Orudzhev, F.F. Sonophotocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue with Magnetically Separable Zn-Doped-CoFe2O4/α-Fe2O3 Heterostructures. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2024, 35, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orudzhev, F.F.; Magomedova, A.G.; Kurnosenko, S.A.; Beklemyshev, V.E.; Li, W.; Wang, C.; Zvereva, I.A. Tuning of Photocatalytic and Piezophotocatalytic Activity of Bi3TiNbO9 via Synthesis-Controlled Surface Defect Engineering. Molecules 2025, 30, 4136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhadwal, N.; Ben Mrad, R.; Behdinan, K. Review of Zinc Oxide Piezoelectric Nanogenerators: Piezoelectric Properties, Composite Structures and Power Output. Sensors 2023, 23, 3859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polewczyk, V.; Magrin Maffei, R.; Vinai, G.; Lo Cicero, M.; Prato, S.; Capaldo, P.; Dal Zilio, S.; di Bona, A.; Paolicelli, G.; Mescola, A.; et al. ZnO Thin Films Growth Optimization for Piezoelectric Application. Sensors 2021, 21, 6114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Zi-Chang, Z.; Shaikh, A. First-principles investigation of size-dependent piezoelectric properties of bare ZnO and ZnO/MgO core-shell nanowires. Superlattices Microstruct. 2018, 120, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Zhao, X.; Cui, C.; Xi, N.; Zhang, X.L.; Liu, H.; Yu, X.; Sang, Y. Influence of Wurtzite ZnO Morphology on Piezophototronic Effect in Photocatalysis. Catalysts 2022, 12, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muslimov, A.; Orudzhev, F.; Gadzhiev, M.; Selimov, D.; Tyuftyaev, A.; Kanevsky, V. Facile synthesis of Ti/TiN/TiON/TiO2 composite particles for plasmon-enhanced solar photocatalytic decomposition of methylene blue. Coatings 2022, 12, 1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhu, D.; He, H.; Wang, Q.; Xing, L.; Xue, X. Enhanced piezo/solar photocatalytic activity of Ag/ZnO nanotetrapods arising from the coupling of surface plasmon resonance and piezophototronic effect. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2017, 102, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, A.T.; Costa, C.; Fraga, S. Editorial of Special Issue: The Toxicity of Nanomaterials and Legacy Contaminants: Risks to the Environment and Human Health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muslimov, A.; Antipov, S.; Gadzhiev, M.; Ulyankina, A.; Krasnova, V.; Lavrikov, A.; Kanevsky, V. Oxidation of Zinc Microparticles by Microwave Plasma to Form Effective Solar-Sensitive Photocatalysts. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orudzhev, F.; Muslimov, A.; Selimov, D.; Gulakhmedov, R.R.; Lavrikov, A.; Kanevsky, V.; Gasimov, R.; Krasnova, V.; Sobola, D. Oxygen Vacancies and Surface Wettability: Key Factors in Activating and Enhancing the Solar Photocatalytic Activity of ZnO Tetrapods. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, X.; Hao, A.; Cao, Y.; Hu, J.; Xie, J.; Jia, D. Effective promoting piezocatalytic property of zinc oxide for degradation of organic pollutants and insight into piezocatalytic mechanism. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 577, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Fang, J.; Wang, J.; Long, X.; Zhang, I.Y.; Huang, R. Effective Degradation of Metronidazole through Electrochemical Activation of Peroxymonosulfate: Mechanistic Insights and Implications. Energies 2024, 17, 1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado Domínguez, S.M.; Barrera-Díaz, C.E.; Balderas Hernández, P.; Amado-Piña, D.; Torres-Blancas, T.; Roa-Morales, G. Metronidazole Electro-Oxidation Degradation on a Pilot Scale. Catalysts 2025, 15, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzky, P.F.; HallingSorensen, B. The toxic effect of the antibiotic metronidazole on aquatic organisms. Chemosphere 1997, 35, 2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendesky, A.; Menendez, D.; Ostrosky-Wegman, P. Is metronidazole carcinogenic? Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. Res. 2002, 511, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Chu, R.; Khan, Z.U.H. A Theoretical Study on the Degradation Mechanism, Kinetics, and Ecotoxicity of Metronidazole (MNZ) in •OH- and SO4•−-Assisted Advanced Oxidation Processes. Toxics 2023, 11, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hama Aziz, K.H.; Mustafa, F.S.; Karim, M.A.H.; Hama, S. Pharmaceutical Pollution in the Aquatic Environment: Advanced Oxidation Processes as Efficient Treatment Approaches: A Review. Mater. Adv. 2025, 6, 3433–3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, J.; Li, Z.; Yao, Y.; Wang, J.; Hao, L. Metronidazole Degradation via Visible Light-Driven Z-Scheme BiTmDySbO7/BiEuO3 Heterojunction Photocatalyst. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuvo, M.S.H.; Putul, R.A.; Hossain, K.S.; Masum, S.M.; Molla, M.A.I. Photocatalytic Removal of Metronidazole Antibiotics from Water Using Novel Ag-N-SnO2 Nanohybrid Material. Toxics 2024, 12, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta Roy, S.; Ghosh, M.; Chowdhury, J. Adsorptive parameters and influence of hot geometries on the SER(R) S spectra of methylene blue molecules adsorbed on gold nanocolloidal particles. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2015, 46, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzia, M.A.; Khan, A.; Parveen, A.; Almohammedi, A.A. Enhanced antibacterial and visible light driven photocatalytic activity of graphene oxide mediated Ag2O nanocomposites. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2024, 56, 1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khubezhov, S.; Ponkratova, E.; Kuzmichev, A.; Maleeva, K.; Larin, A.; Karsakova, E. Fastand scalable fabrication of Ag/TiO2 nanostructured substrates for enhanced plasmonic sensing and photocatalytic applications. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 670, 160669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabadanova, A.; Selimov, D.; Gulakhmedov, R.R.; Magomedova, A.G.; Ronoh, K.; Částková, K.; Sobola, D.; Kaspar, P.; Shuaibov, A.; Abdurakhmanov, M.G.; et al. Piezophotocatalytic Activity of PVDF/Fe3O4 Nanofibers: Effect of Ultrasound Frequency and Light Source on the Decomposition of Methylene Blue. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 23035–23048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janotti, A.; Van de Walle, C.G. Fundamentals of zinc oxide as a semiconductor. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2009, 72, 126501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, K.; Hahn, D. Electron Spin Resonance of Lattice Defects in Zinc Oxide. Phys. Status Solidi A 1974, 24, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomisto, F.; Saarinen, K.; Look, D.C.; Farlow, G.C. Introduction and recovery of point defects in electron-irradiated ZnO. Phys. Rev. B 2005, 72, 085206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlasenko, L.S.; Watkins, G.D. Optical detection of electron paramagnetic resonance in room-temperature electron-irradiated ZnO. Phys. Rev. B 2005, 71, 125210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCluskey, M.D.; Jokela, S.J. Defects in ZnO. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 106, 071101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sze, S.M.; Ng, K.K. Physics of Semiconductor Devices, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trang, T.N.Q.; Phan, T.B.; Nam, N.D.; Thu, V.T.H. In Situ Charge Transfer at the Ag@ZnO Photoelectrochemical Interface toward the High Photocatalytic Performance of H2 Evolution and RhB Degradation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 12195–12206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.; Feng, X.; Lan, D.; Chen, Y.; Zhong, Q.; Liu, C.; Cheng, Y.; Qi, R.; Ge, J.; Yu, C.; et al. Coupling Effect of Au Nanoparticles with the Oxygen Vacancies of TiO2−x for Enhanced Charge Transfer. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 23823–23831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, S.; Tang, J.; Xie, H.; Ma, J.; Chi, H.; Li, C. Roles of oxygen vacancies in surface plasmon resonance photoelectrocatalytic water oxidation. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2023, 4, 101386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Cui, J.; Liang, J.; Khan, S.N.; Jia, J. Synergy between oxygen vacancies and SPR effect in of Bi@Vo-Bi2O3 for efficient photocatalytic performance under visible light. Chemsuschem. 2025, 18, e202402175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holston, M.S.; Golden, E.M.; Kananen, B.E.; McClory, J.W.; Giles, N.C.; Halliburton, L.E. Identification of the zinc-oxygen divacancy in ZnO crystals. J. Appl. Phys. 2016, 119, 145701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Fu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Xing, L.; Liu, B.; Xue, X. Ultrafast piezo-photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutions by Ag2O/tetrapod-ZnO nanostructures under ultrasonic/UV exposure. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 87446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, S.; Lan, J.; Yan, J.; Khan, I.; Żak, M.; Zheng, Y.; Ma, M.; Wang, Z.; Guo, S.; Huang, S.; et al. ZnO/Ag2S heterogeneous nanowire arrays on porous nickel foam: Synergistic piezo-photocatalytic enhancement for high-efficiency environmental remediation. Surf. Interfaces 2025, 72, 107000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, G.; Thangavel, S.; Vasudevan, V.; Zoltán, K. Efficient visible-light piezophototronic activity of ZnO-Ag8S hybrid for degradation of organic dye molecule. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2020, 143, 109473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, J.; Wu, Z.; Zhu, K.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Tai, G.; Liu, X.; Lu, S. Enhanced visible-light photocatalytic performances of ZnO through loading AgI and coupling piezo-photocatalysis. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 852, 156848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhu, G.; Huang, X.; Liu, W.; Hu, W.; Song, M.; He, W.; Liu, J.; Zhai, J. Piezotronic-effect-enhanced Ag2S/ZnO photocatalyst for organic dye degradation. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 48176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Shan, B.; Zhao, X.; Ji, C.; Li, Z.; Yu, J.; Xu, S.; Jiao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Man, B. Plasmonic enhanced piezoelectric photoresponse with flexible PVDF@Ag-ZnO/Au composite nanofiber membranes. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 32509–32527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yao, B.; He, Y. Piezo-enhanced photodegradation of organic pollutants on Ag3PO4/ZnO nanowires using visible light and ultrasonic. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 528, 146819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroutan, R.; Peighambardoust, S.J.; Boffito, D.C.; Ramavandi, B. Sono-Photocatalytic Activity of Cloisite 30B/ZnO/Ag2O Nanocomposite for the Simultaneous Degradation of Crystal Violet and Methylene Blue Dyes in Aqueous Media. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Sample | ZnO, % | Ag, % |

|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | ~100 | ~0 |

| 0.25 | ~100 | ~0 |

| 0.50 | ~99.9 | ~0.1 |

| 0.75 | 98.5 | 1.5 |

| 1 | 97.0 | 3.0 |

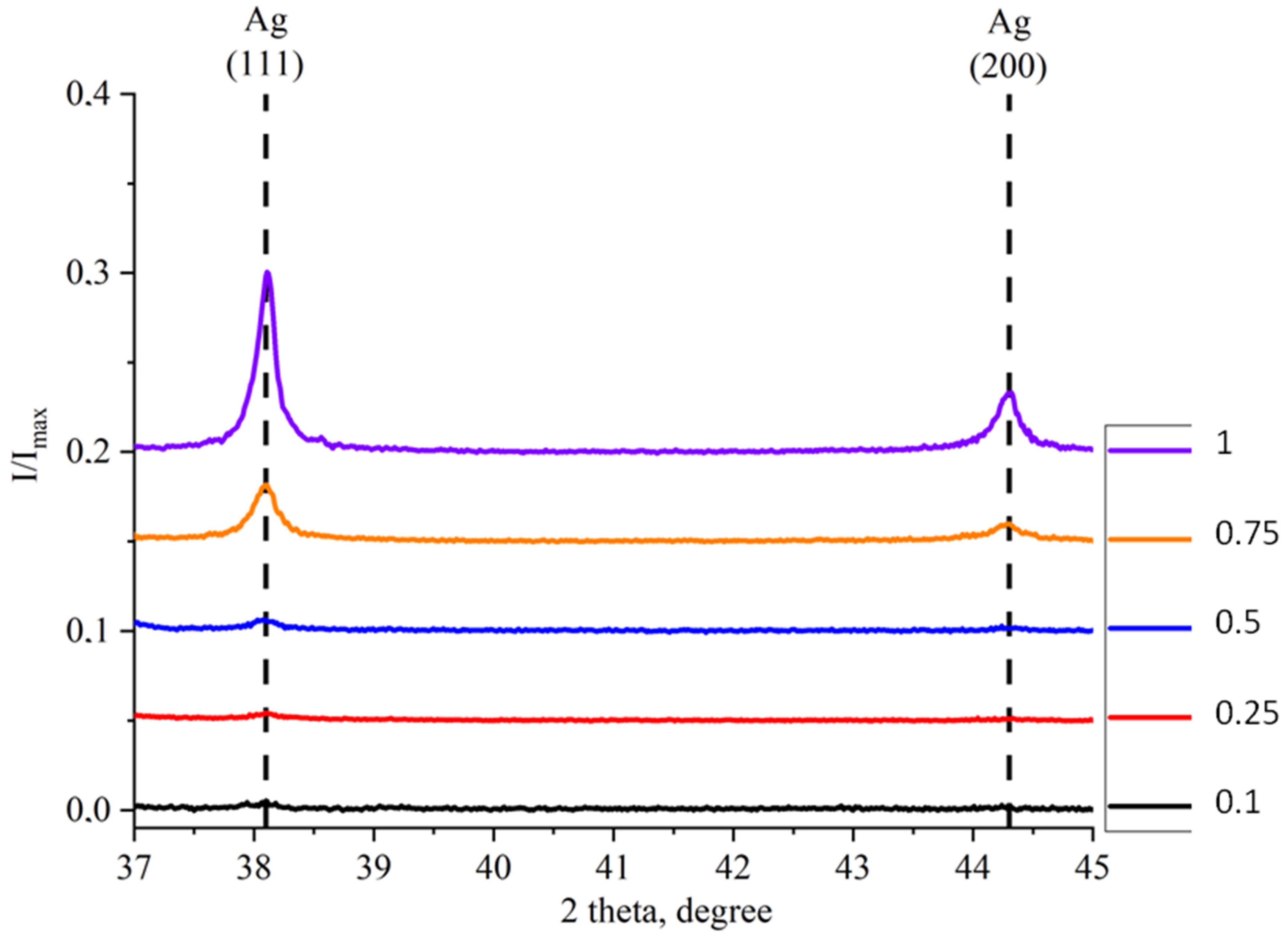

| Type of Sample | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 1 | ||

| I/Imax | Ag (111) | 0.00446 | 0.00519 | 0.00618 | 0.03154 | 0.10058 |

| Ag (200) | 0.00124 | 0.00245 | 0.00143 | 0.00986 | 0.03304 | |

| Catalyst | Light Source | Source of Mechanical Impact | Catalyst Loading | Pollutant (Type, Conc.) | Reaction Time | Efficiency, % Rate Const | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag/ZnO microtetrapods | metal-halide lamp (75 W) | US (120 W, 40 kHz) | 20 mg | MNZ (5 mg/L, 20 mL) | 5 min | 93%/ 0.56 min−1 | This work |

| ZnO-T/Ag2O | UV light (50 W, 365 nm) | US (200 W) | 2 g/L | MB (5 mg/L, 50 mL) | 2 min | 100%/ 1.51 min−1 | [57] |

| ZnO-T/Ag | Spherical Xe lamp (500 W) | US probe (200 W) | 2 g/L | MO (5 mg/L, 100 mL) | 25 min | 100% 0.17 min−1 | [29] |

| ZnO/AgS nanowire | Xenon lamp (300 W) with a cut-off filter (λ ≤ 400 nm) | Magnetic stirrer (500 rpm) | On Ni foam (2 cm × 2 cm, thickness: 1.5 mm) | RhB (2.5 mg/L, 30 mL) | 30 min | 96.6% 0.24542 min−1 | [58] |

| ZnO-T/Ag8S | Halogen lamp (20 V, 250 W) | US (50 W) | - | RhB (1 × 10−3 M, 100 mL) | 120 min | 93.11% 0.0102 min−1 | [59] |

| ZnO/AgI nanoflower | Xenon lamp (250 W, λ > 400 nm, I ~ 100 mW/cm2) | US (40 kHz, 120 W) | 20 mg | RhB (10 mg/L, 100 mL) | 40 min | 97.2% | [60] |

| Ag2S/ZnO nanowire | Solar illumination (I = 80 mW/cm−2) | US (45 kHz) | - | MB (1 mg/L, 100 mL) | 240 min | 100% | [61] |

| PVDF@Ag- ZnO/Au nanofibers | Xenon lamp (300 W) | US (200 W, 40 kHz) | - | RhB (10 mg/L, 50 mL) | 120 min | 98.8%/ 0.04 min−1 | [62] |

| Ag3PO4/ZnO nanowire | Xenon lamp (300 W) with a cut-off filter (λ ≤ 400 nm) | US (50 W, 40 kHz) | 30 mg | MB | 30 min | 98.16%/ 0.1341 min−1 | [63] |

| Cloisite 30B/ZnO/Ag2O | UV lamp (15 W, 254 nm) | US (24 kHz, 180 W) | 0.5 g/L | MB (5 mg/L) | 50 min | 98.43% | [64] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Orudzhev, F.; Gadzhiev, M.; Gyulakhmedov, R.; Antipov, S.; Muslimov, A.; Krasnova, V.; Il’ichev, M.; Kulikov, Y.; Chistolinov, A.; Yusupov, D.; et al. Plasmon-Enhanced Piezo-Photocatalytic Degradation of Metronidazole Using Ag-Decorated ZnO Microtetrapods. Molecules 2025, 30, 4643. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234643

Orudzhev F, Gadzhiev M, Gyulakhmedov R, Antipov S, Muslimov A, Krasnova V, Il’ichev M, Kulikov Y, Chistolinov A, Yusupov D, et al. Plasmon-Enhanced Piezo-Photocatalytic Degradation of Metronidazole Using Ag-Decorated ZnO Microtetrapods. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4643. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234643

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrudzhev, Farid, Makhach Gadzhiev, Rashid Gyulakhmedov, Sergey Antipov, Arsen Muslimov, Valeriya Krasnova, Maksim Il’ichev, Yury Kulikov, Andrey Chistolinov, Damir Yusupov, and et al. 2025. "Plasmon-Enhanced Piezo-Photocatalytic Degradation of Metronidazole Using Ag-Decorated ZnO Microtetrapods" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4643. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234643

APA StyleOrudzhev, F., Gadzhiev, M., Gyulakhmedov, R., Antipov, S., Muslimov, A., Krasnova, V., Il’ichev, M., Kulikov, Y., Chistolinov, A., Yusupov, D., Volchkov, I., Tyuftyaev, A., & Kanevsky, V. (2025). Plasmon-Enhanced Piezo-Photocatalytic Degradation of Metronidazole Using Ag-Decorated ZnO Microtetrapods. Molecules, 30(23), 4643. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234643