β-Blockers in the Environment: Challenges in Understanding Their Persistence and Ecological Impact

Abstract

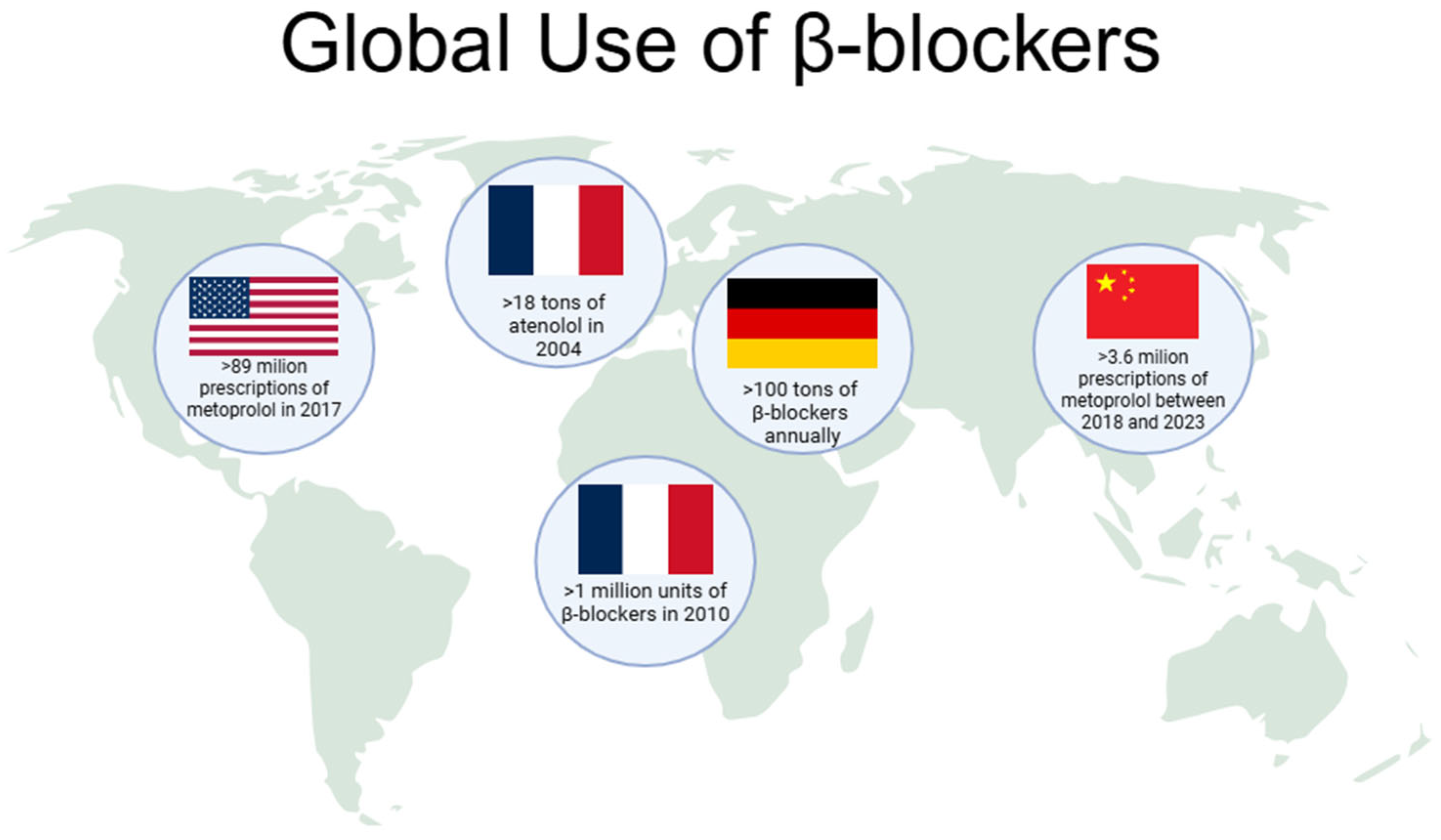

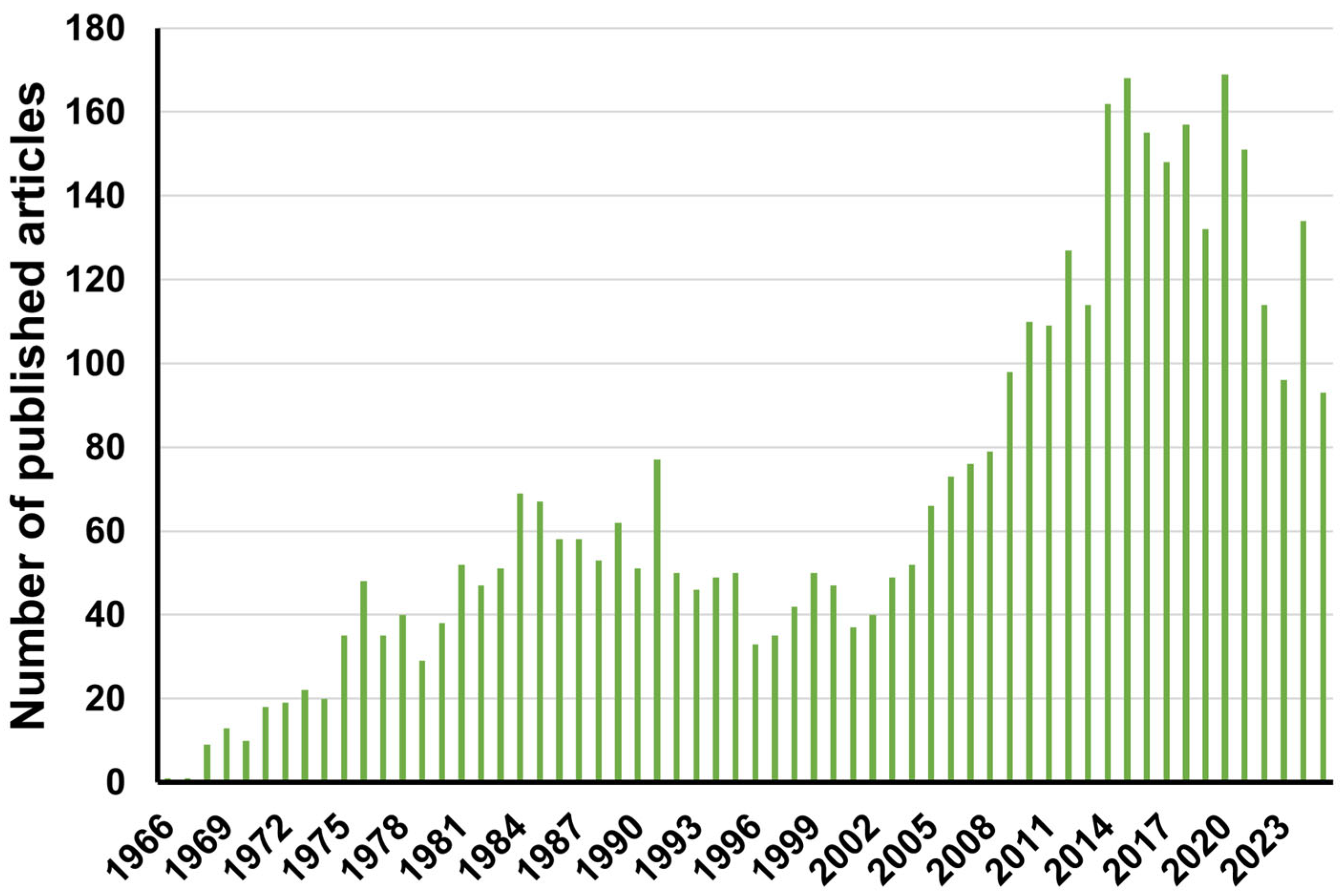

1. Introduction

2. Occurrence and Distribution in the Environment

2.1. Main Emission Sources

2.2. Environmental Presence in Aquatic Systems

3. Physicochemical Properties and Environmental Behaviour

3.1. Chemical Structure and Chirality

3.2. Lipophilicity, Ionization, and Environmental Partitioning

3.3. Sorption to Soils and Sediments

3.4. Chemical and Photochemical Stability

3.5. Bioaccumulation and Trophic Transfer

4. Biological Degradation Mechanisms and Metabolites

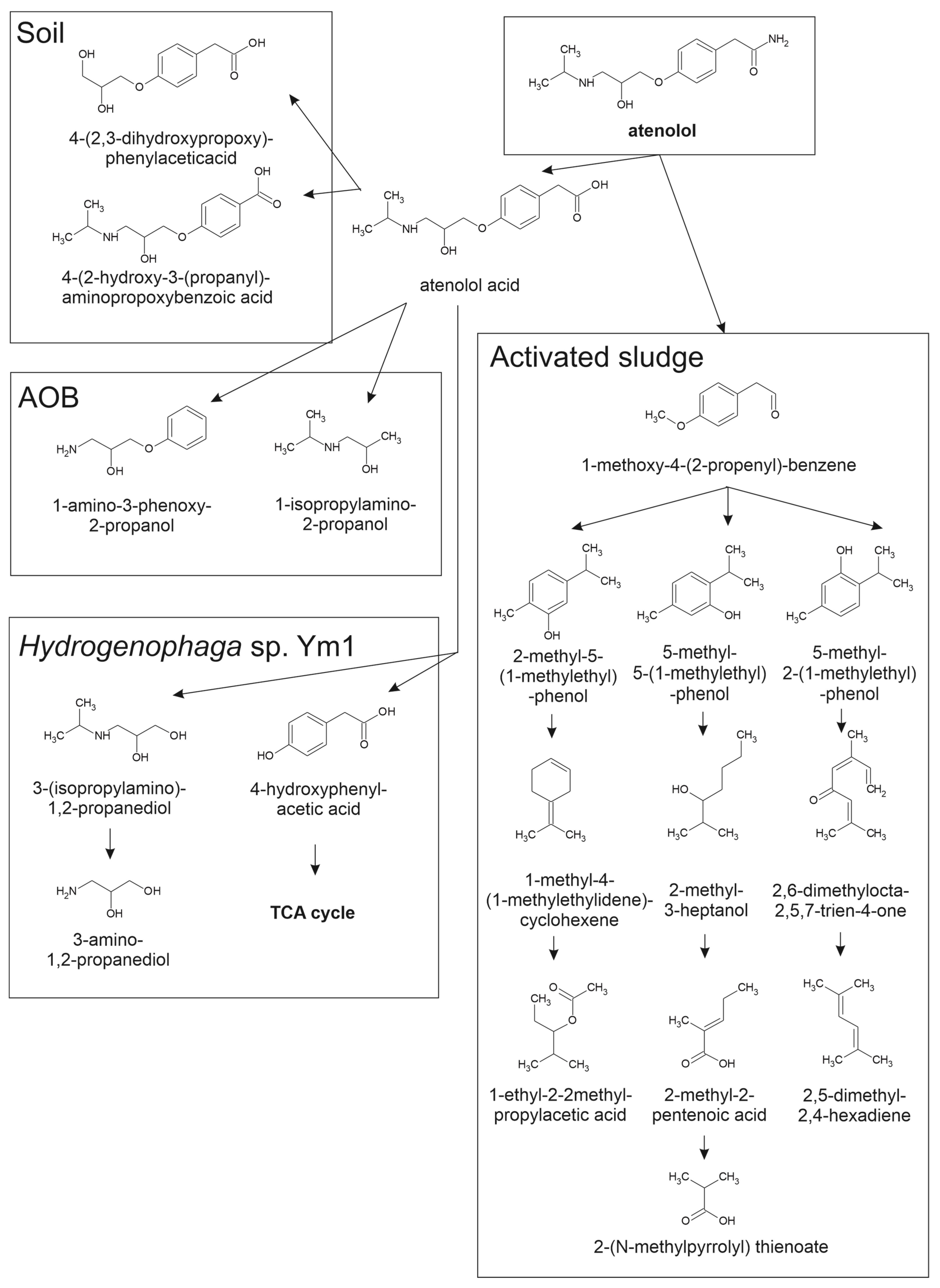

4.1. Atenolol

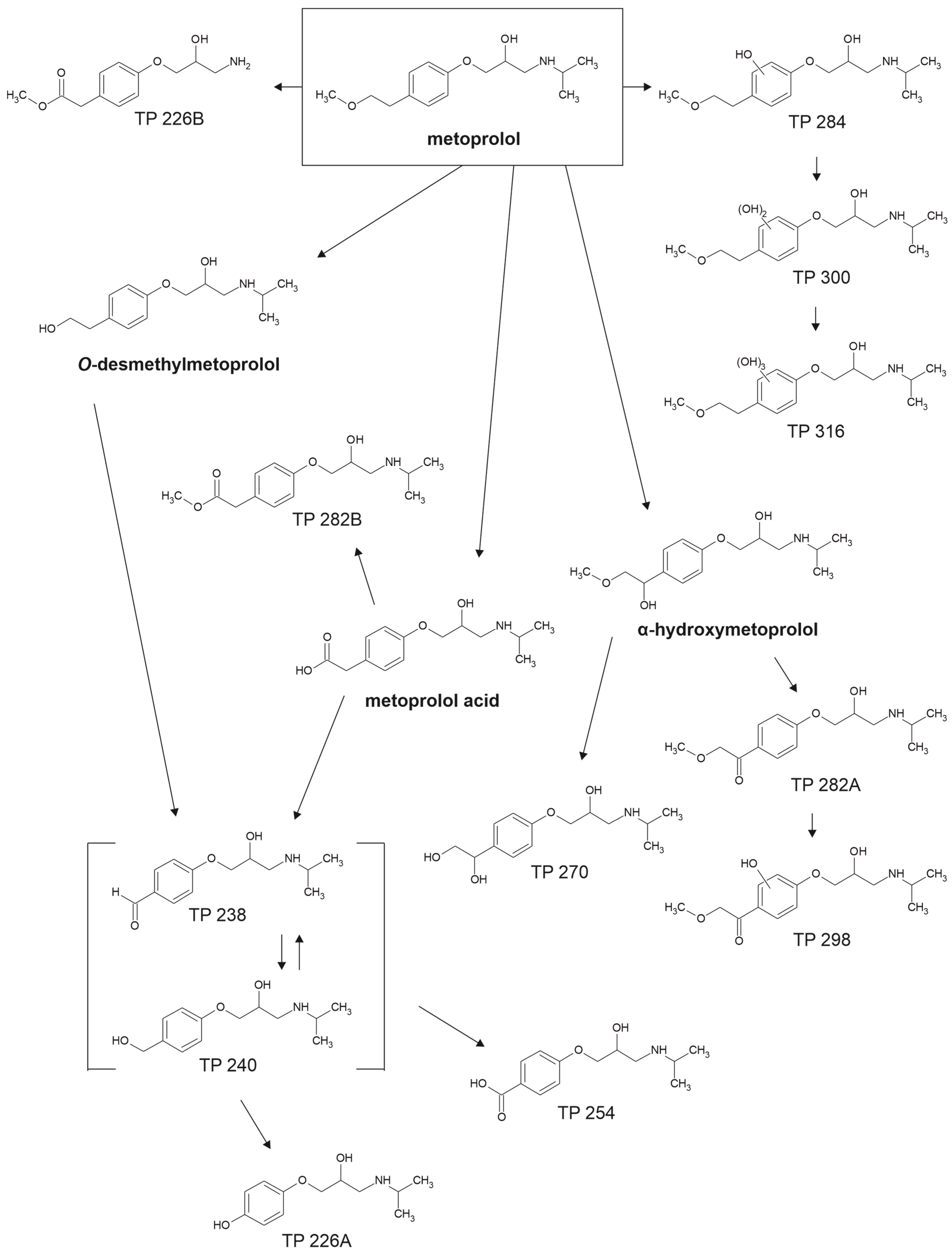

4.2. Metoprolol

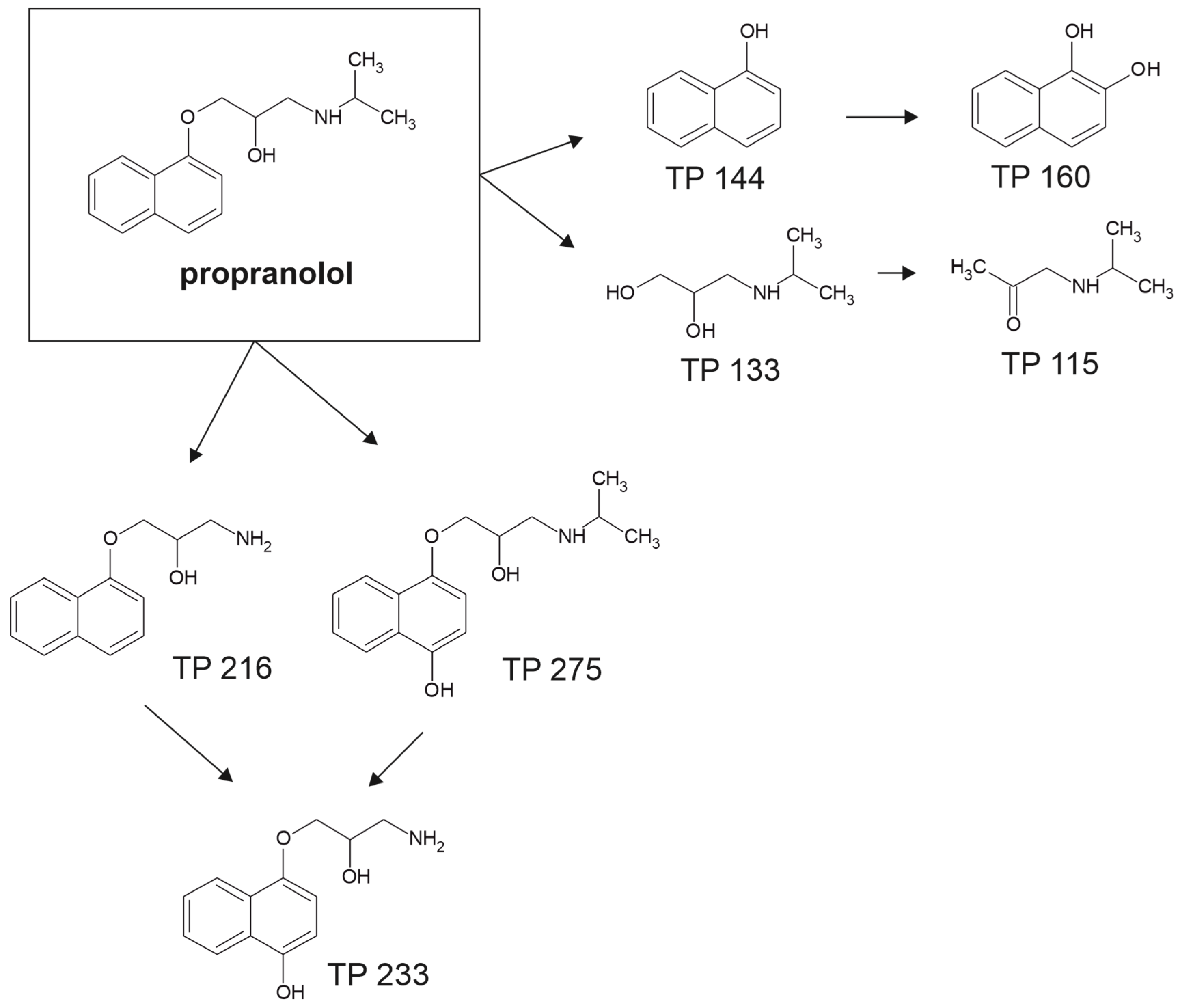

4.3. Propranolol

5. Ecotoxicological Impact

5.1. Bacteria and Fungi

5.2. Algae

5.3. Plants

5.4. Animals

5.5. Humans

5.6. Microcosms Community-Level Effects

6. Knowledge Gaps and Research Challenges

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ratnasari, A.; Thakur, S.S.; Zainiyah, I.F.; Boopathy, R.; Wikurendra, E.A. An Overarching Critical Review on Beta-Blocker Biodegradation: Occurrence, Ecotoxicity, and Their Pathways in Water Environments. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2025, 11, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Deng, Y.; Yang, F.; Miao, Q.; Ngien, S.K. Systematic Review of Contaminants of Emerging Concern (CECs): Distribution, Risks, and Implications for Water Quality and Health. Water 2023, 15, 3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Vale, G.T.; Ceron, C.S.; Gonzaga, N.A.; Simplicio, J.A.; Padovan, J.C. Three Generations of β-Blockers: History, Class Differences and Clinical Applicability. Curr. Hypertens. Rev. 2018, 15, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. High Blood Pressure from the FDA Office of Women’s Health. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/consumers/womens-health-topics/high-blood-pressure#Beta_Blockers (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Yan, Y.; An, W.; Mei, S.; Zhu, Q.; Li, C.; Yang, L.; Zhao, Z.; Huo, J. Real-World Research on Beta-Blocker Usage Trends in China and Safety Exploration Based on the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2024, 25, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueye, C.; Cissé, L.; Diaw, P.A.; Mbaye, O.; Seye, M. Analysis of Beta-Blockers in Environment—A Review. JSM Env. Sci. Ecol. 2025, 13, 1106. [Google Scholar]

- Averbuch, T.; Esfahani, M.; Khatib, R.; Kayima, J.; Miranda, J.J.; Wadhera, R.K.; Zannad, F.; Pandey, A.; Van Spall, H.G.C. Pharmaco-Disparities in Heart Failure: A Survey of the Affordability of Guideline Recommended Therapy in 10 Countries. ESC Heart Fail. 2023, 10, 3152–3163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, E.; Mayor, F., Jr.; D’Ocon, P. Role of Beta-Blockers in Cardiovascular Disease in 2019. Rev. Española Cardiol. 2019, 72, 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lucia, C.; Eguchi, A.; Koch, W.J. New Insights in Cardiac β-Adrenergic Signaling during Heart Failure and Aging. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, M.J. Cardiovascular Drug Class Specificity: β-Blockers. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2004, 47, 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maszkowska, J.; Stolte, S.; Kumirska, J.; Łukaszewicz, P.; Mioduszewska, K.; Puckowski, A.; Caban, M.; Wagil, M.; Stepnowski, P.; Białk-Bielińska, A. Beta-Blockers in the Environment: Part I. Mobility and Hydrolysis Study. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 493, 1112–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulvi, A.; Aydın, S.; Aydın, M.E. Fate of Selected Pharmaceuticals in Hospital and Municipal Wastewater Effluent: Occurrence, Removal, and Environmental Risk Assessment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 75609–75625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprzyk-Hordern, B.; Dinsdale, R.M.; Guwy, A.J. The Removal of Pharmaceuticals, Personal Care Products, Endocrine Disruptors and Illicit Drugs during Wastewater Treatment and Its Impact on the Quality of Receiving Waters. Water Res. 2009, 43, 363–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Sun, H.; Zhang, Y.; Alder, A.C. Occurrence and Enantiomer Profiles of β-Blockers in Wastewater and a Receiving Water Body and Adjacent Soil in Tianjin, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 650, 1122–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheurer, M.; Ramil, M.; Metcalfe, C.D.; Groh, S.; Ternes, T.A. The Challenge of Analyzing Beta-Blocker Drugs in Sludge and Wastewater. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010, 396, 845–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biel-Maeso, M.; Corada-Fernández, C.; Lara-Martín, P.A. Monitoring the Occurrence of Pharmaceuticals in Soils Irrigated with Reclaimed Wastewater. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 235, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.; Kumar, A.; Du, J.; Hepplewhite, C.; Ellis, D.J.; Christy, A.G.; Beavis, S.G. Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products (PPCPs) in Australia’s Largest Inland Sewage Treatment Plant, and Its Contribution to a Major Australian River during High and Low Flow. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 541, 1625–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subedi, B.; Kannan, K. Occurrence and Fate of Select Psychoactive Pharmaceuticals and Antihypertensives in Two Wastewater Treatment Plants in New York State, USA. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 514, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iancu, V.I.; Radu, G.L.; Scutariu, R. A New Analytical Method for the Determination of Beta-Blockers and One Metabolite in the Influents and Effluents of Three Urban Wastewater Treatment Plants. Anal. Methods 2019, 11, 4668–4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paíga, P.; Correia, M.; Fernandes, M.J.; Silva, A.; Carvalho, M.; Vieira, J.; Jorge, S.; Silva, J.G.; Freire, C.; Delerue-Matos, C. Assessment of 83 Pharmaceuticals in WWTP Influent and Effluent Samples by UHPLC-MS/MS: Hourly Variation. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 648, 582–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.T.; Zhao, Y.T.; Jiang, B.; Li, Y.Y.; Lin, J.G.; Wang, D.G. Evaluation of Three Chronic Diseases by Selected Biomarkers in Wastewater. ACS ES T Water 2023, 3, 943–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, E.; Petrie, B.; Kasprzyk-Hordern, B.; Wolfaardt, G.M. The Fate of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products (PPCPs), Endocrine Disrupting Contaminants (EDCs), Metabolites and Illicit Drugs in a WWTW and Environmental Waters. Chemosphere 2017, 174, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elorriaga, Y.; Marino, D.J.; Carriquiriborde, P.; Ronco, A.E. Human Pharmaceuticals in Wastewaters from Urbanized Areas of Argentina. Bull. Env. Contam. Toxicol. 2013, 90, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslah, B.; Hapeshi, E.; Jrad, A.; Fatta-Kassinos, D.; Hedhili, A. Pharmaceuticals and Illicit Drugs in Wastewater Samples in North-Eastern Tunisia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 18226–18241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlicchi, P.; Al Aukidy, M.; Galletti, A.; Petrovic, M.; Barceló, D. Hospital Effluent: Investigation of the Concentrations and Distribution of Pharmaceuticals and Environmental Risk Assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 430, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T.S.; Murphy, M.; Mendola, N.; Wong, V.; Carlson, D.; Waring, L. Characterization of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products in Hospital Effluent and Waste Water Influent/Effluent by Direct-Injection LC-MS-MS. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 518–519, 459–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.H.; Lin, A.Y.C.; Wang, X.H.; Lin, C.F. Occurrence of β-Blockers and β-Agonists in Hospital Effluents and Their Receiving Rivers in Southern Taiwan. Desalination Water Treat. 2011, 32, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Qarni, H.; Collier, P.; O’Keeffe, J.; Akunna, J. Investigating the Removal of Some Pharmaceutical Compounds in Hospital Wastewater Treatment Plants Operating in Saudi Arabia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 13003–13014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.S.; Aziz, Z.; Wang, E.S.; Chik, Z. Unused Medicine Take-Back Programmes: A Systematic Review. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2024, 17, 2395535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). Management of Pharmaceutical Household Waste; OECD: Paris, France, 2022; ISBN 9789264452909. [Google Scholar]

- Shaaban, H.; Alghamdi, H.; Alhamed, N.; Alziadi, A.; Mostafa, A. Environmental Contamination by Pharmaceutical Waste: Assessing Patterns of Disposing Unwanted Medications and Investigating the Factors Influencing Personal Disposal Choices. J. Pharmacol. Pharm. Res. 2018, 1, 003. [Google Scholar]

- Vulliet, E.; Cren-Olivé, C.; Grenier-Loustalot, M.F. Occurrence of Pharmaceuticals and Hormones in Drinking Water Treated from Surface Waters. Env. Chem. Lett. 2011, 9, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Qu, H.; Wang, B.; Wang, F.; Yu, G. Widespread Monitoring of Chiral Pharmaceuticals in Urban Rivers Reveals Stereospecific Occurrence and Transformation. Env. Int. 2020, 138, 105657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, B.; Yan, S.; Lian, L.; Yang, X.; Wan, C.; Dong, H.; Song, W. Occurrence and Indicators of Pharmaceuticals in Chinese Streams: A Nationwide Study. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 236, 889–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giebułtowicz, J.; Stankiewicz, A.; Wroczyński, P.; Nałęcz-Jawecki, G. Occurrence of Cardiovascular Drugs in the Sewage-Impacted Vistula River and in Tap Water in the Warsaw Region (Poland). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 24337–24349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huerta-Fontela, M.; Galceran, M.T.; Ventura, F. Occurrence and Removal of Pharmaceuticals and Hormones through Drinking Water Treatment. Water Res. 2011, 45, 1432–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, R.; Somogyvári, I.; Eke, Z.; Torkos, K. Seasonal Monitoring of Cardiovascular and Antiulcer Agents’ Concentrations in Stream Waters Encompassing a Capital City. J. Pharm. 2013, 2013, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nantaba, F.; Wasswa, J.; Kylin, H.; Palm, W.U.; Bouwman, H.; Kümmerer, K. Occurrence, Distribution, and Ecotoxicological Risk Assessment of Selected Pharmaceutical Compounds in Water from Lake Victoria, Uganda. Chemosphere 2020, 239, 124642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodré, F.F.; Santana, J.S.; Sampaio, T.R.; Brandão, C.C.S. Seasonal and Spatial Distribution of Caffeine, Atrazine, Atenolol and Deet in Surface and Drinking Waters from the Brazilian Federal District. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2018, 29, 1854–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Jaimes, J.A.; Postigo, C.; Melgoza-Alemán, R.M.; Aceña, J.; Barceló, D.; López de Alda, M. Study of Pharmaceuticals in Surface and Wastewater from Cuernavaca, Morelos, Mexico: Occurrence and Environmental Risk Assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 613–614, 1263–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nödler, K.; Hillebrand, O.; Idzik, K.; Strathmann, M.; Schiperski, F.; Zirlewagen, J.; Licha, T. Occurrence and Fate of the Angiotensin II Receptor Antagonist Transformation Product Valsartan Acid in the Water Cycle—A Comparative Study with Selected β-Blockers and the Persistent Anthropogenic Wastewater Indicators Carbamazepine and Acesulfame. Water Res. 2013, 47, 6650–6659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gworek, B.; Kijeńska, M.; Wrzosek, J.; Graniewska, M. Pharmaceuticals in the Soil and Plant Environment: A Review. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2021, 232, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossberger, A.; Hadar, Y.; Borch, T.; Chefetz, B. Biodegradability of Pharmaceutical Compounds in Agricultural Soils Irrigated with Treated Wastewater. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 185, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aznar, R.; Sánchez-Brunete, C.; Albero, B.; Rodríguez, J.A.; Tadeo, J.L. Occurrence and Analysis of Selected Pharmaceutical Compounds in Soil from Spanish Agricultural Fields. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 4772–4782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebert, C.D.; Hänsicke, A.; Nagel, T. Stereochemical Comparison of Nebivolol with Other β-Blockers. Chirality 2008, 20, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.R.; Castro, P.M.L.; Tiritan, M.E. Chiral Pharmaceuticals in the Environment. Env. Chem. Lett. 2012, 10, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprzyk-Hordern, B. Pharmacologically Active Compounds in the Environment and Their Chirality. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 4466–4503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernando, M.D.; Gómez, M.J.; Agüera, A.; Fernández-Alba, A.R. LC-MS Analysis of Basic Pharmaceuticals (Beta-Blockers and Anti-Ulcer Agents) in Wastewater and Surface Water. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2007, 26, 581–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, M.J.; Abernethy, D.R.; Greenblatt, D.J. Effect of Obesity on the Pharmacokinetics of Drugs in Humans. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2010, 2, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramil, M.; El Aref, T.; Fink, G.; Scheurer, M.; Ternes, T.A. Fate of Beta Blockers in Aquatic-Sediment Systems: Sorption and Biotransformation. Env. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 962–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, M.; Sheng, Q.; Sui, Q.; Lu, H. β-Blockers in the Environment: Distribution, Transformation, and Ecotoxicity. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 266, 115269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbato, F.; Di Martino, G.; Grumetto, L.; La Rotonda, M.I. Can Protonated β-Blockers Interact with Biomembranes Stronger than Neutral Isolipophilic Compounds? A Chromatographic Study on Three Different Phospholipid Stationary Phases (IAM-HPLC). Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2005, 25, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira-Leite, C.; Carneiro, C.; Soares, J.X.; Afonso, C.; Nunes, C.; Lúcio, M.; Reis, S. Biophysical Characterization of the Drug-Membrane Interactions: The Case of Propranolol and Acebutolol. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2013, 84, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kibbey, T.C.G.; Paruchuri, R.; Sabatini, D.A.; Chen, L. Adsorption of Beta Blockers to Environmental Surfaces. Env. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 5349–5356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffer, M.; Börnick, H.; Nödler, K.; Licha, T.; Worch, E. Role of Cation Exchange Processes on the Sorption Influenced Transport of Cationic β-Blockers in Aquifer Sediments. Water Res. 2012, 46, 5472–5482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.M.; Sayen, S.; Guillon, E. Adsorption of Individual and Mixtures of β-Blockers and Copper in Soils and Sediments. Env. Toxicol. Chem. 2022, 41, 2700–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrozini, B.; Cervini, P.; Cavalheiro, É.T.G. Thermal Behavior of the β-Blocker Propranolol. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2016, 123, 1013–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzek, J.; Kwiecień, A.; Zylewski, M. Stability of Atenolol, Acebutolol and Propranolol in Acidic Environment Depending on Its Diversified Polarity. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2006, 11, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peikova, L.; Pencheva, I.; Tzvetkova, B. Chemical Stability-Indicating HPLC Study of Fixed-Dosage Combination Containing Metoprolol Tartrate and Hydrochlorothiazide. J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 2013, 5, 132–140. [Google Scholar]

- Kovácsa, K.; Tóth, T.; Wojnárovits, L. Evaluation of Advanced Oxidation Processes for β-Blockers Degradation: A Review. Water Sci. Technol. 2022, 85, 685–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piram, A.; Salvador, A.; Verne, C.; Herbreteau, B.; Faure, R. Photolysis of β-Blockers in Environmental Waters. Chemosphere 2008, 73, 1265–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.T.; Williams, H.E. Kinetics and Degradation Products for Direct Photolysis of β-Blockers in Water. Env. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makunina, M.P.; Pozdnyakov, I.P.; Chen, Y.; Grivin, V.P.; Bazhin, N.M.; Plyusnin, V.F. Mechanistic Study of Fulvic Acid Assisted Propranolol Photodegradation in Aqueous Solution. Chemosphere 2015, 119, 1406–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmiel, T.; Mieszkowska, A.; Kempińska-Kupczyk, D.; Kot-Wasik, A.; Namieśnik, J.; Mazerska, Z. The Impact of Lipophilicity on Environmental Processes, Drug Delivery and Bioavailability of Food Components. Microchem. J. 2019, 146, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lu, G.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Li, S.; Yan, Z. Occurrence, Bioaccumulation and Risk Assessment of Lipophilic Pharmaceutically Active Compounds in the Downstream Rivers of Sewage Treatment Plants. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 511, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmina, E.S.; Wondrousch, D.; Kühne, R.; Potemkin, V.A.; Schüürmann, G. Variation in Predicted Internal Concentrations in Relation to PBPK Model Complexity for Rainbow Trout. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 550, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, W.; Huang, Z.; Ping, S.; Zhang, S.; Wen, X.; He, Y.; Ren, Y. Toxicological Effects of Atenolol and Venlafaxine on Zebrafish Tissues: Bioaccumulation, DNA Hypomethylation, and Molecular Mechanism. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 299, 118898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo, M.; Cristos, D.; González, P.; López-Aca, V.; Dománico, A.; Carriquiriborde, P. Accumulation of Human Pharmaceuticals and Activity of Biotransformation Enzymes in Fish from Two Areas of the Lower Rio de La Plata Basin. Chemosphere 2021, 266, 129012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Y.; Lin, H.; Zhang, X.; Wu, R.; Zhang, K.; Leung, K.M.Y.; Lam, J.C.W.; Lam, P.K.S. Enantiomer-Specific Bioaccumulation and Distribution of Chiral Pharmaceuticals in a Subtropical Marine Food Web. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 394, 122589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutere, C.; Posselt, M.; Ho, A.; Horn, M.A. Biodegradation of Metoprolol in Oxic and Anoxic Hyporheic Zone Sediments: Unexpected Effects on Microbial Communities. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 6103–6115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodešová, R.; Klement, A.; Golovko, O.; Fér, M.; Nikodem, A.; Kočárek, M.; Grabic, R. Root Uptake of Atenolol, Sulfamethoxazole and Carbamazepine, and Their Transformation in Three Soils and Four Plants. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 9876–9891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, M.; Sheng, Q.; Lv, Z.; Lu, H. Novel Pathway and Acetate-Facilitated Complete Atenolol Degradation by Hydrogenophaga Sp. YM1 Isolated from Activated Sludge. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 810, 152218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, M.; Lou, J.; Zhu, W.; Li, D.; Yu, P.; Lu, H. Mechanism of β-Blocker Biodegradation by Wastewater Microorganisms. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 444, 130338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Radjenovic, J.; Yuan, Z.; Ni, B.J. Biodegradation of Atenolol by an Enriched Nitrifying Sludge: Products and Pathways. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 312, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, R.; Aghapour, A.A.; Khorsandi, H. Investigating the Biological Degradation of the Drug β-Blocker Atenolol from Wastewater Using the SBR. Biodegradation 2022, 33, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, D.; Ju, F.; Hu, W.; Liang, J.; Bai, Y.; Liu, H.; Qu, J. Profiling Microbial Removal of Micropollutants in Sand Filters: Biotransformation Pathways and Associated Bacteria. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 423, 127167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koba, O.; Golovko, O.; Kodešová, R.; Klement, A.; Grabic, R. Transformation of Atenolol, Metoprolol, and Carbamazepine in Soils: The Identification, Quantification, and Stability of the Transformation Products and Further Implications for the Environment. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 218, 574–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubirola, A.; Llorca, M.; Rodriguez-Mozaz, S.; Casas, N.; Rodriguez-Roda, I.; Barceló, D.; Buttiglieri, G. Characterization of Metoprolol Biodegradation and Its Transformation Products Generated in Activated Sludge Batch Experiments and in Full Scale WWTPs. Water Res. 2014, 63, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaén-Gil, A.; Castellet-Rovira, F.; Llorca, M.; Villagrasa, M.; Sarrà, M.; Rodríguez-Mozaz, S.; Barceló, D. Fungal Treatment of Metoprolol and Its Recalcitrant Metabolite Metoprolol Acid in Hospital Wastewater: Biotransformation, Sorption and Ecotoxicological Impact. Water Res. 2019, 152, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, M.; Escher, B.I.; Richle, P.; Schaffner, C.; Alder, A.C. Elimination of β-Blockers in Sewage Treatment Plants. Water Res. 2007, 41, 1614–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, A.R.; Afonso, C.M.; Castro, P.M.L.; Tiritan, M.E. Enantioselective Biodegradation of Pharmaceuticals, Alprenolol and Propranolol, by an Activated Sludge Inoculum. Ecotoxicol. Env. Saf. 2013, 87, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zhao, B.; Liu, C. Removal Mechanisms of β-Blockers by Anaerobic Digestion in a UASB Reactor with Carbon Feeding. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2020, 11, 100531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triebskorn, R.; Casper, H.; Scheil, V.; Schwaiger, J. Ultrastructural Effects of Pharmaceuticals (Carbamazepine, Clofibric Acid, Metoprolol, Diclofenac) in Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio). Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2007, 387, 1405–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maranho, L.A.; André, C.; DelValls, T.A.; Gagné, F.; Martín-Díaz, M.L. Toxicological Evaluation of Sediment Samples Spiked with Human Pharmaceutical Products: Energy Status and Neuroendocrine Effects in Marine Polychaetes Hediste Diversicolor. Ecotoxicol. Env. Saf. 2015, 118, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, T.Y.; Yoon, D.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.Y.; Kim, S.D. Mode of Action Characterization for Adverse Effect of Propranolol in Daphnia Magna Based on Behavior and Physiology Monitoring and Metabolite Profiling. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 233, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrott, J.L.; Balakrishnan, V.K. Life-Cycle Exposure of Fathead Minnows to Environmentally Relevant Concentrations of the Β-Blocker Drug Propranolol. Env. Toxicol. Chem. 2017, 36, 1644–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiner, M.; Laforsch, C.; Letzel, T.; Geist, J. Sublethal Effects of the Beta-Blocker Sotalol at Environmentally Relevant Concentrations on the New Zealand Mudsnail Potamopyrgus Antipodarum. Env. Toxicol. Chem. 2014, 33, 2510–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salinas, A. Effects of Metoprolol and Propranolol Beta-Blockers Mixture on Effects of Metoprolol and Propranolol Beta-Blockers Mixture on Morphological and Physiological Responses in the American Morphological and Physiological Responses in the American Oyster Oyster. Master’s Thesis, The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, Edinburg, TX, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Godoy, A.A.; Domingues, I.; de Carvalho, L.B.; Oliveira, Á.C.; de Jesus Azevedo, C.C.; Taparo, J.M.; Assano, P.K.; Mori, V.; de Almeida Vergara Hidalgo, V.; Nogueira, A.J.A.; et al. Assessment of the Ecotoxicity of the Pharmaceuticals Bisoprolol, Sotalol, and Ranitidine Using Standard and Behavioral Endpoints. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 5469–5481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.-T.; Williams, T.D.; Cumming, R.I.; Holm, G.; Hetheridge, M.J. Comparative Aquatic Toxicity of Propranolol and Its Photodegraded Mixtures: Algae and Rotifer Screening. Env. Toxicol. Chem. 2009, 12, 2622–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maszkowska, J.; Stolte, S.; Kumirska, J.; Łukaszewicz, P.; Mioduszewska, K.; Puckowski, A.; Caban, M.; Wagil, M.; Stepnowski, P.; Białk-Bielińska, A. Beta-Blockers in the Environment: Part II. Ecotoxicity Study. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 493, 1122–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, B.; Feijão, E.; de Carvalho, R.C.; Duarte, I.A.; Silva, M.; Matos, A.R.; Cabrita, M.T.; Novais, S.C.; Lemos, M.F.L.; Marques, J.C.; et al. Effects of Propranolol on Growth, Lipids and Energy Metabolism and Oxidative Stress Response of Phaeodactylum Tricornutum. Biology 2020, 9, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, J.; Hui, M.; Li, V.; Lorenzi, V.; de la Paz, N.; Cheng, S.H.; Lai-Chan, L.; Schlenk, D. Effects of Propranolol on Heart Rate and Development in Japanese Medaka (Oryzias Latipes) and Zebrafish (Danio Rerio). Aquat. Toxicol. 2012, 122–123, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margiotta-Casaluci, L.; Owen, S.F.; Rand-Weaver, M.; Winter, M.J. Testing the Translational Power of the Zebrafish: An Inter-Species Analysis of Responses to Cardiovascular Drugs. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, K.M.; Moon, T.W. Behavioral and Biochemical Adjustments of the Zebrafish Danio Rerio Exposed to the β-Blocker Propranolol. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2016, 199, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheong, H.I.; Johnson, J.; Cormier, M.; Hosseini, K. In Vitro Cytotoxicity of Eight β-Blockers in Human Corneal Epithelial and Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cell Lines: Comparison with Epidermal Keratinocytes and Dermal Fibroblasts. Toxicol. Vitr. 2008, 22, 1070–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Četojević-Simin, D.D.; Armaković, S.J.; Šojić, D.V.; Abramović, B.F. Toxicity Assessment of Metoprolol and Its Photodegradation Mixtures Obtained by Using Different Type of TiO2 Catalysts in the Mammalian Cell Lines. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 463–464, 968–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oskarsson, H.; Wiklund, A.K.E.; Thorsén, G.; Danielsson, G.; Kumblad, L. Community Interactions Modify the Effects of Pharmaceutical Exposure: A Microcosm Study on Responses to Propranolol in Baltic Sea Coastal Organisms. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindim, C.; van Gils, J.; Georgieva, D.; Mekenyan, O.; Cousins, I.T. Evaluation of Human Pharmaceutical Emissions and Concentrations in Swedish River Basins. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 572, 508–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarabyar, S.; Farahbakhsh, A.; Tahmasebi, H.A.; Mahmoodzadeh Vaziri, B.; Khosroyar, S. Enhancing Photocatalytic Degradation of Beta-Blocker Drugs Using TiO2 NPs/Zeolite and ZnO NPs/Zeolite as Photocatalysts: Optimization and Kinetic Investigations. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| β-Blocker | Country/Region | Mean Concentration in the WWTP Influent [µg/L] | Mean Concentration in the WWTP Effluent [µg/L] | Year of Samples Collection | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Propranolol | China, Tianjin | 0.180 | Information not provided | 2013 | [14] |

| Turkey | 0.00331–0.00743 | 0.00064 | Information not provided | [12] | |

| Australia | 0.018–0.151 | 0.036–0.076 | 2012–2013 | [17] | |

| USA, New York | 0.377–2.000 | 0.299–0.852 | 2013 | [18] | |

| Germany | 0.064 | 0.062 | 2008 | [15] | |

| Romania | 0.0268 | 0.0194 | 2018 | [19] | |

| Portugal | 0.320 | - | 2017 | [20] | |

| Spain | 0.123 | 0.073 | 2014–2015 | [16] | |

| UK | 0.557 | 0.265 | 2007 | [13] | |

| Metoprolol | China, Tianjin | 0.692–3.5 | 0.522–5.249 | 2013 | [14] |

| Turkey | 0.00743–0.0868 | 0.0397 | Information not provided | [12] | |

| Germany | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2008 | [15] | |

| UK | 0.075 | 0.069 | 2007 | [13] | |

| Atenolol | China | 0.00554 | Information not provided | 2016–2021 | [21] |

| Turkey | 0.154–0.424 | 0.138–0.163 | Information not provided | [12] | |

| Australia | 0.255–0.300 | 0.075–0.135 | 2012–2013 | [17] | |

| USA, New York | 0.003–0.097 | 0.023–0.153 | 2013 | [18] | |

| China, Tianjin | 1.283 | 0.0487 | 2013 | [14] | |

| Germany | 1.3 | 0.4 | 2008 | [15] | |

| Romania | 0.2086 | 0.0946 | 2018 | [19] | |

| Spain | 1.620 | 1.140 | 2014–2015 | [16] | |

| UK | 12.913 | 2.870 | 2007 | [13] | |

| South Africa | 1.593–2.541 | 0.364–0.712 | 2015 | [22] | |

| Argentina | Information not provided | 0.2–1.7 | Information not provided | [23] | |

| Tunisia | 2.198–0.388 | 1.244–0.420 | 2014 | [24] | |

| Nadolol | China | 0.00001 | Information not provided | 2016–2021 | [21] |

| Sotalol | China | 0.00454 | Information not provided | 2016–2021 | [21] |

| China, Tianjin | 0.243 | Information not provided | 2013 | [14] | |

| Turkey | 0.00743–0.081 | 0.0304 | Information not provided | [12] | |

| Germany | 2.1 | 1.9 | 2008 | [15] | |

| Betaxolol | Romania | 0.0449 | 0.0169 | 2018 | [19] |

| Bisoprolol | Germany | 0.48 | 0.31 | 2008 | [15] |

| Romania | 0.1001 | 0.051 | 2018 | [19] |

| β-Blocker | Country/Region | Mean Concentration [µg/L] | Year of Samples Collection | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Propranolol | Southern Taiwan | 0.3660 | 2009 | [27] |

| Italy | 0.023–0.085 | 2009–2010 | [26] | |

| China, Tianjin | 0.110–0.158 | 2013 | [14] | |

| Turkey | 0.00097–0.0149 | Information not provided | [12] | |

| USA | 0.01–0.200 | 2013 | [26] | |

| Atenolol | Southern Taiwan | 0.0941 | 2009 | [27] |

| Italy | 2.4–5.8 | 2009–2010 | [25] | |

| Saudi Arabia | 0.329–0.730 | 2014 | [28] | |

| China, Tianjin | 0.0009–0.0036 | 2013 | [14] | |

| Turkey | 0.0353–0.156 | Information not provided | [12] | |

| USA | 1.370–3.790 | 2013 | [26] | |

| Metoprolol | Southern Taiwan | 0.5813 | 2009 | [27] |

| Italy | 0.74–1.1 | 2009–2010 | [25] | |

| China, Tianjin | 0.0078–10.002 | 2013 | [14] | |

| Turkey | 0.00669–0.0182 | Information not provided | [12] | |

| USA | 0.750–3.540 | 2013 | [26] | |

| Acebutolol | Southern Taiwan | 0.0975 | 2009 | [27] |

| Nadolol | Italy | 0.0012 | 2009–2010 | [25] |

| Pindolol | Italy | 0.038–0.12 | 2009–2010 | [25] |

| Sotalol | Italy | 0.048–5.1 | 2009–2010 | [25] |

| Turkey | 0.00041–0.00754 | Information not provided | [12] | |

| USA | 0.1–0.53 | 2013 | [26] | |

| Timolol | Italy | 0.033 | 2009–2010 | [25] |

| Betaxolol | Italy | 0.01–0.011 | 2009–2010 | [25] |

| β-Blocker | Country/Region | Water Body | Mean Concentration [ng/L] | Year of Samples Collection | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Propranolol | France | surface waters (urban and rural dam of water, river, and lakes) | 0.8–2 | 2007–2008 | [32] |

| China | Beiyun rivers | 0–5.86 | 2016 | [33] | |

| China | Surface waters from 31 provinces | 0.25 | 2014–2015 | [34] | |

| Poland | Vistula River | 1.2–38 | 2013–2014 | [35] | |

| Poland | Tap water (Warsaw) | 7.0 | 2013–2014 | [35] | |

| Spain | Llobregat River | 54 | 2008–2009 | [36] | |

| Hungary | Streams near Budapest | 36 | 2010–2011 | [37] | |

| Atenolol | South Africa | River | 156–272 | 2015 | [22] |

| Uganda | Lake Victoria | 24–380 | 2018 | [38] | |

| Brasil | Paranoá Lake | 34.7–90 | 2017 | [39] | |

| France | Surface waters (urban and rural dam of water, river and lakes) | 0.2–34 | 2007–2008 | [32] | |

| China | Beiyun rivers | 1.4–6.2 | 2016 | [33] | |

| Poland | Vistula River | 1.4–104 | 2013–2014 | [35] | |

| Poland | Tap water (Warsaw) | 1.5 | 2013–2014 | [35] | |

| Mexico | Apatlaco River | 4–32 | 2015–2016 | [40] | |

| Spain | Llobregat River | 470 | 2008–2009 | [36] | |

| Germany | Surface waters | 8.8 | 2012 | [41] | |

| Hungary | Streams near Budapest | 55 | 2010–2011 | [37] | |

| Metoprolol | France | Surface waters (urban and rural dam of water, river and lakes) | 0.5–2 | 2007–2008 | [32] |

| Uganda | Lake Victoria | 0.4–21 | 2018 | [38] | |

| China | Beiyun rivers | 49.0–680.1 | 2016 | [33] | |

| China | Surface waters from 31 provinces | 5.4 | 2014–2015 | [34] | |

| Poland | Vistula River | 15–1190 | 2013–2014 | [35] | |

| Poland | Tap water (Warsaw) | 14 | 2013–2014 | [35] | |

| Spain | Llobregat River | 90 | 2008–2009 | [36] | |

| Germany | Surface waters | 102 | 2012 | [41] | |

| Hungary | Streams near Budapest | 1230 | 2010–2011 | [37] | |

| Sotalol | Poland | Vistula River | 34–1170 | 2013–2014 | [35] |

| Poland | Tap water (Warsaw) | 16 | 2013–2014 | [35] | |

| Spain | Llobregat River | 100 | 2008–2009 | [36] | |

| Germany | Surface waters | 25 | 2012 | [41] | |

| Hungary | Streams near Budapest | 160 | 2010–2011 | [37] | |

| Bisoprolol | Poland | Vistula River | 15–660 | 2013–2014 | [35] |

| Poland | Tap water (Warsaw) | 8.5 | 2013–2014 | [35] | |

| Spain | Llobregat River | 57 | 2008–2009 | [36] | |

| Labetalol | Poland | Vistula River | 1.9 | 2013–2014 | [35] |

| Spain | Llobregat River | 6 | 2008–2009 | [36] | |

| Acebutolol | Poland | Vistula River | 2.5–270 | 2013–2014 | [35] |

| Poland | Tap water (Warsaw) | 1.2 | 2013–2014 | [35] | |

| Spain | Llobregat River | 44 | 2008–2009 | [36] | |

| Hungary | Streams near Budapest | 98 | 2010–2011 | [37] | |

| Carvedilol | Hungary | Streams near Budapest | 41 | 2010–2011 | [37] |

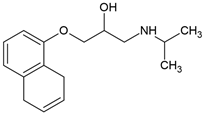

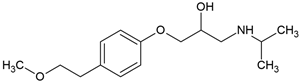

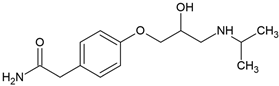

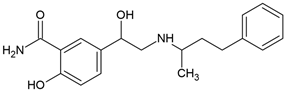

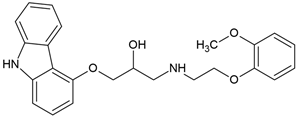

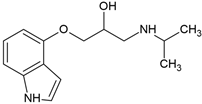

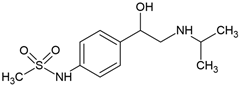

| Compound (CAS Number) | Structure | pKa | log Kow | log D in pH 7.4 | Solubility in Water at 25 °C (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

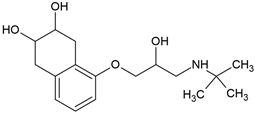

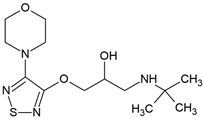

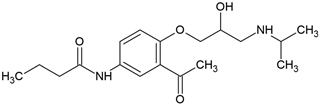

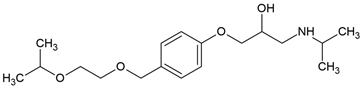

| Propranolol (525-66-6) |  | 9.5 | 3.5 | 1.29 | 61.7 |

| Metoprolol (51384-51-1) |  | 9.7 | 1.9 | −0.28 | 16,900 |

| Atenolol (29122-68-7) |  | 9.6 | 0.16 | −1.61 | 13,300 |

| Nadolol (42200-33-9) |  | 9.7 | 0.8 | −1.30 | 8330 |

| Timolol (26839-75-8) |  | 9.2 | 1.76 | −0.52 | 2470 |

| Acebutolol (37517-30-9) |  | 9.2 | 1.71 | 3.4 | 259 |

| Betaxolol (63659-18-7) |  | 9.4 | 3.26 | 0.42 | 451 |

| Bisoprolol (66722-44-9) |  | 9.6 | 2.15 | −0.02 | 2240 |

| Labetalol (36894-69-6) |  | 9.3 | 2.6 | 1.09 | 117 |

| Carvedilol (72956-09-3) |  | 8.0 | 4.19 | 3.5 | insoluble |

| Pindolol (13523-86-9) |  | 9.7 | 1.75 | −0.10 | insoluble |

| Sotalol (3930-20-9) |  | 8.2 | 0.2 | −1.50 | 5510 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dzionek, A. β-Blockers in the Environment: Challenges in Understanding Their Persistence and Ecological Impact. Molecules 2025, 30, 4630. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234630

Dzionek A. β-Blockers in the Environment: Challenges in Understanding Their Persistence and Ecological Impact. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4630. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234630

Chicago/Turabian StyleDzionek, Anna. 2025. "β-Blockers in the Environment: Challenges in Understanding Their Persistence and Ecological Impact" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4630. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234630

APA StyleDzionek, A. (2025). β-Blockers in the Environment: Challenges in Understanding Their Persistence and Ecological Impact. Molecules, 30(23), 4630. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234630