Dynamic Hormonal Networks in Flax During Fusarium oxysporum Infection and Their Regulation by Spermidine

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Progression of the Infection with Fusarium oxysporum in Flax

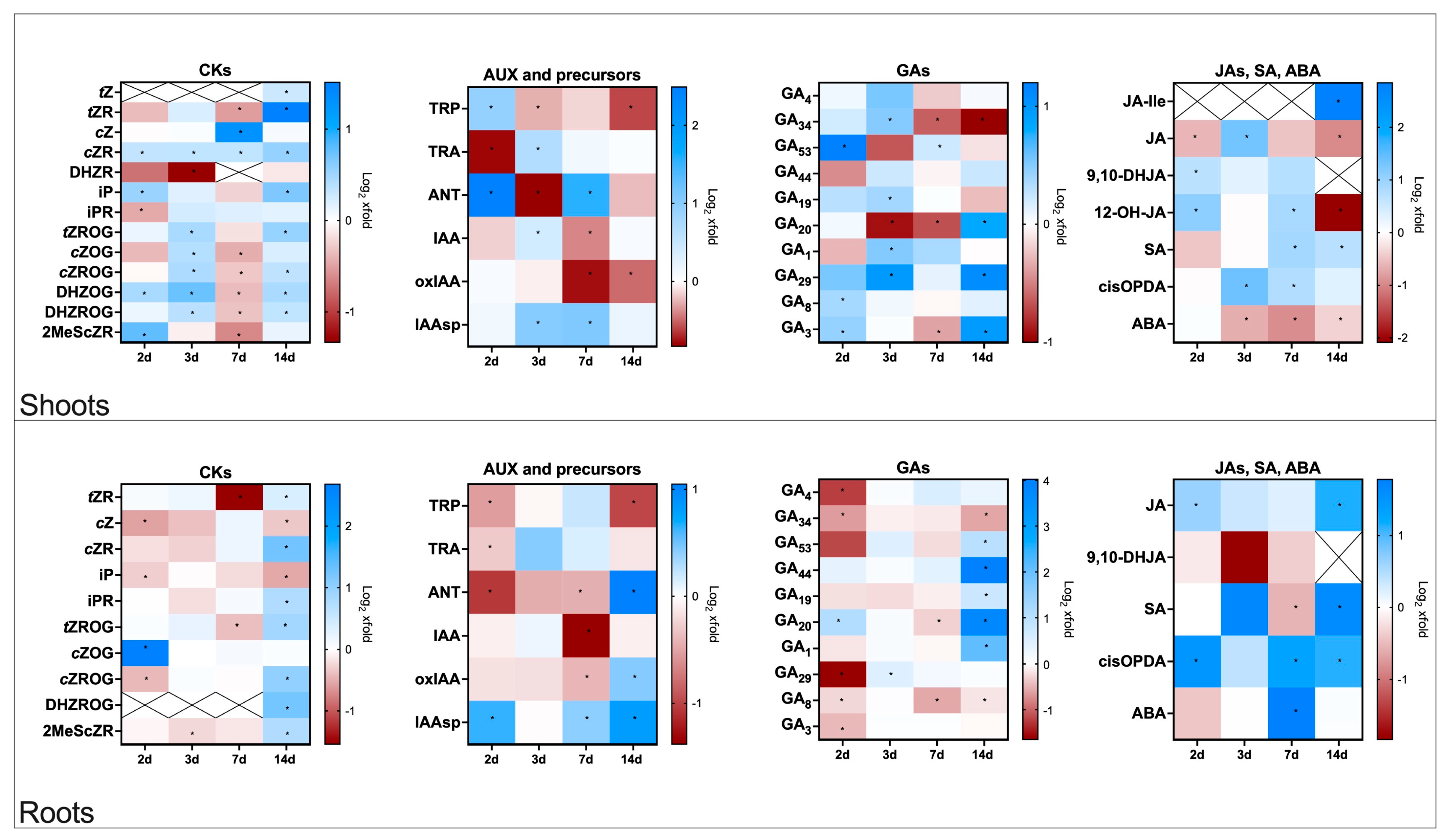

2.2. Hormonal Changes in Flax Plants Infected with Fusarium oxysporum

2.2.1. Cytokinin Profiles in Roots and Shoots of Flax Plants Infected with F. oxysporum

2.2.2. Auxin Profiles in Roots and Shoots of Flax Plants Infected with F. oxysporum

2.2.3. Gibberellin Profiles in Roots and Shoots of Flax Plants Infected with F. oxysporum

2.2.4. Profiles of Jasmonates, Salicylic Acid, and Abscisic Acid in Flax Plants Infected with F. oxysporum

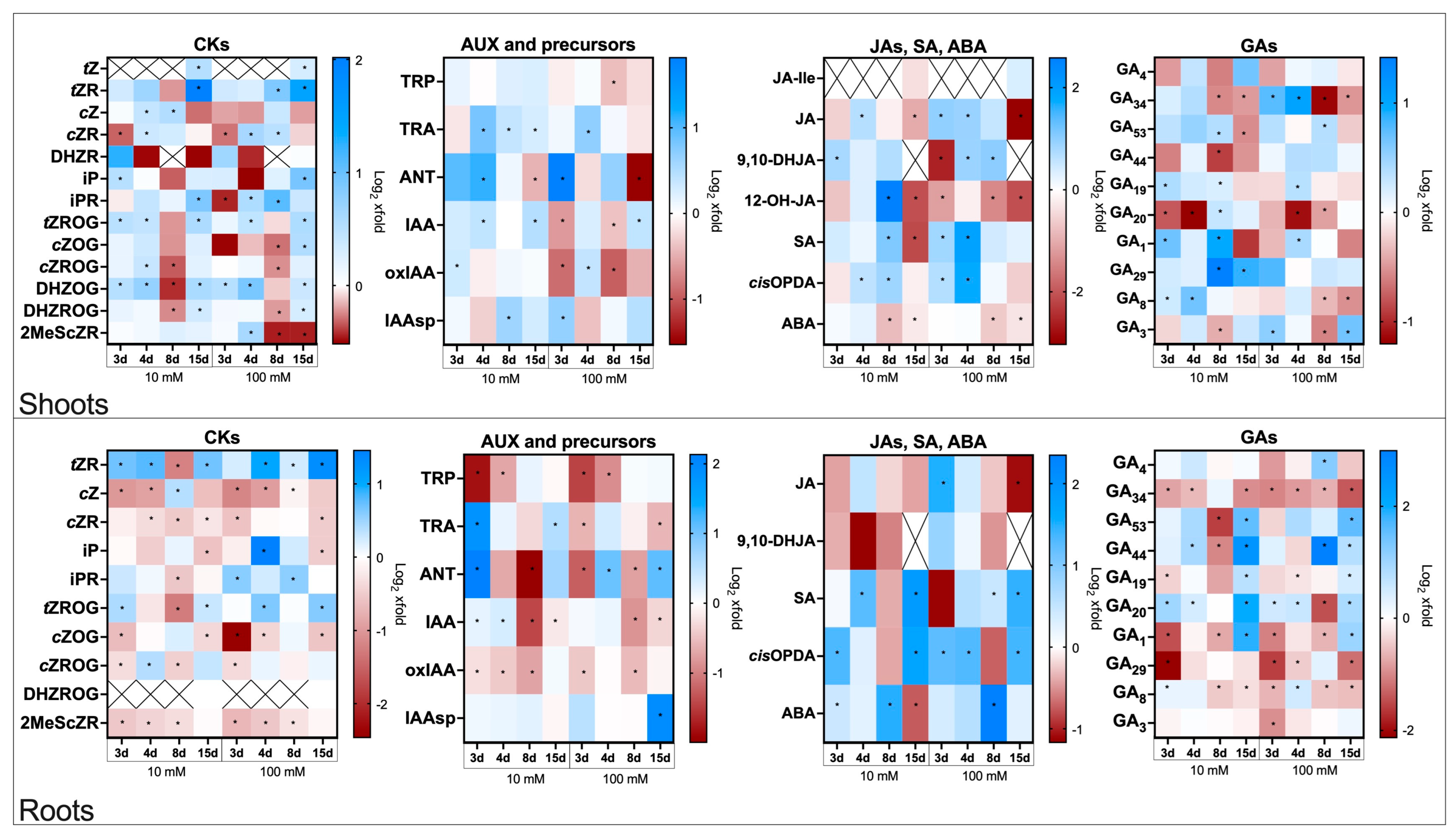

2.3. Hormonal Changes in Spermidine-Treated, Non-Infected Flax Plants

2.3.1. Cytokinins Profiles in Roots and Shoots of Flax Plants Treated with Spd

2.3.2. Auxin Profiles in Roots and Shoots of Flax Plants Treated with Spd

2.3.3. Jasmonates, Salicylic Acid, and Abscisic Acid Profiles in Roots and Shoots of Flax Plants Treated with Spd

2.3.4. Gibberellin Profiles in Roots and Shoots of Flax Plants Treated with Spd

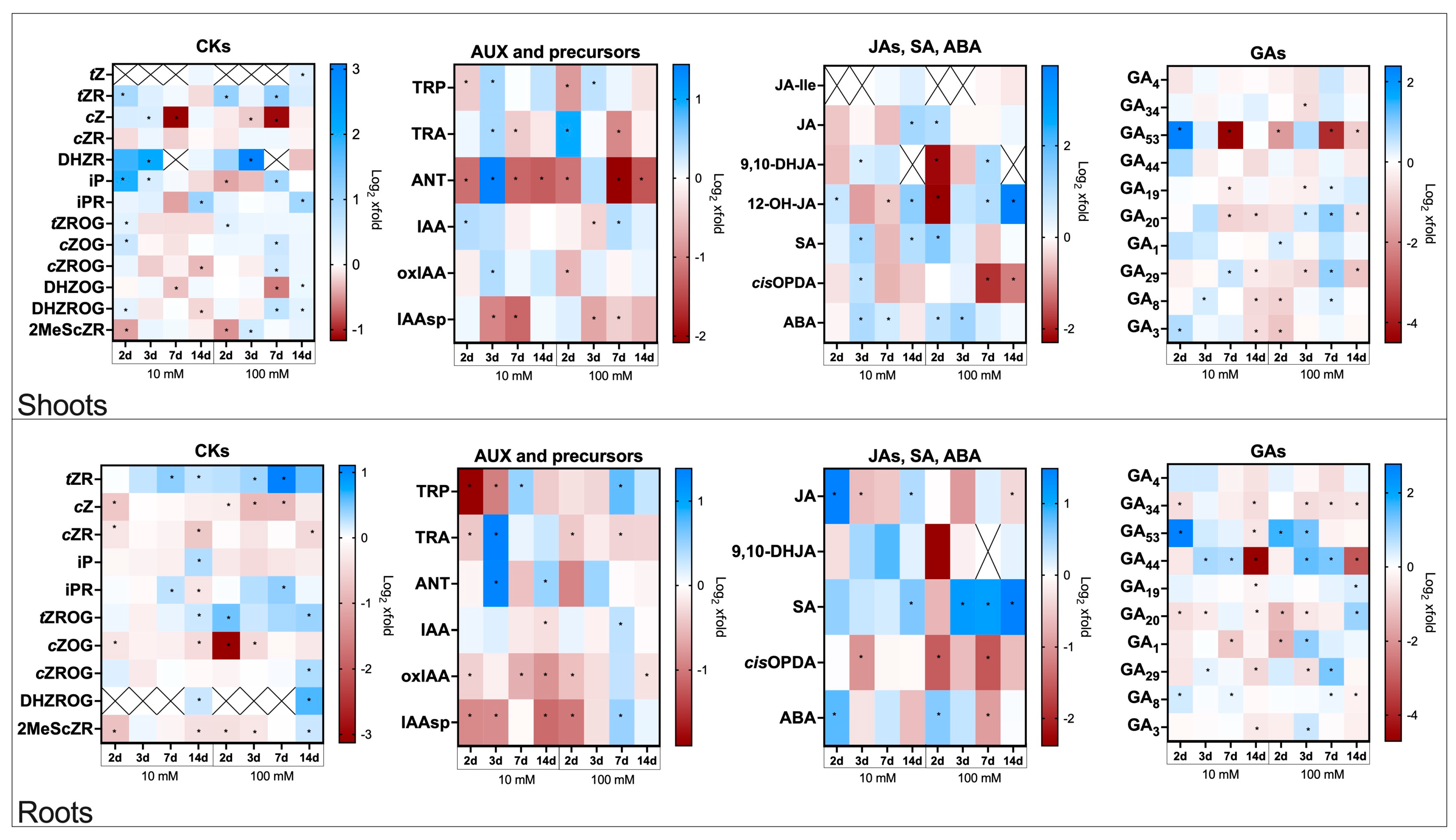

2.4. Hormonal Changes in Spermidine-Treated Flax Plants Infected with Fusarium oxysporum

2.4.1. Cytokinins Profiles in Roots and Shoots in Spermidine-Treated Flax Plants Infected with Fusarium oxysporum

2.4.2. Auxin Profiles in Roots and Shoots in Spermidine-Treated Flax Plants Infected with Fusarium oxysporum

2.4.3. Jasmonates, Salicylic Acid and Abscisic Acid Profiles in Roots and Shoots in Spermidine-Treated Flax Plants Infected with Fusarium oxysporum

2.4.4. Gibberellin Profiles in Roots and Shoots in Spermidine-Treated Flax Plants Infected with Fusarium oxysporum

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions and Prospects

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Plant Material and Growing Conditions

5.2. Phytohormone Extraction and Quantification, Except Gibberellins

5.3. Gibberellin Extraction and Quantification

5.4. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Cytokinins: | |

| tZ | trans-zeatin |

| tZR | trans-zeatin riboside |

| cZ | cis-zeatin |

| cZR | cis-zeatin riboside |

| DHZR | dihydrozeatin riboside |

| iP | N6—isopentenyladenine |

| iPR | N6—isopentenyladenosine |

| tZROG | trans-zeatin riboside-O-glucoside |

| cZOG | cis-zeatin-O-glucoside |

| cZROG | cis-zeatin riboside O-glucoside |

| DHZOG | dihydrozeatin-O-glucoside |

| DHZROG | dihydrozeatin riboside-O-glucoside |

| 2MeScZR | 2-methylthio-cis-zeatin riboside |

| Auxins: | |

| TRP | tryptophan |

| TRA | tryptamine |

| ANT | anthranilic acid |

| IAA | indole-3-acetic acid (active auxin) |

| oxIAA | 2-oxindole-3-acetic acid (oxidised form of IAA) |

| IAAsp | indole-3-acetyl-aspartate (conjugated form of IAA) |

| Gibberellins: | |

| GA1, GA3, GA4 | bioactive gibberellins |

| GA53, GA44, GA19, GA20 | gibberellin biosynthetic precursors |

| GA8, GA29, GA34 | gibberellin catabolites / deactivation products |

| Jasmonates: | |

| JA-Ile | jasmonoyl-isoleucine (bioactive form of JA) |

| JA | jasmonic acid |

| 9,10-DHJA | 9,10-dihydrojasmonic acid |

| 12-OH-JA | 12-hydroxy-jasmonic acid |

| cis-OPDA | 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid (biosynthetic precursor of JA) |

| Salicylic acid: | |

| SA | salicylic acid |

| Abscisic acid: | |

| ABA | abscisic acid |

References

- Gupta, R.; Nadeem, H.; Ahmad, F. Flaxseed Oil Cake. In Oilseed Cake for Nematode Management; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; pp. 89–102. ISBN 978-1-003-31925-2. [Google Scholar]

- Kiryluk, A.; Kostecka, J. Pro-Environmental and Health-Promoting Grounds for Restitution of Flax (Linum usitatissimum L.) Cultivation. J. Ecol. Eng. 2020, 21, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyse, J.; Lecomte, S.; Marcou, S.; Mongelard, G.; Gutierrez, L.; Höfte, M. Overview and Management of the Most Common Eukaryotic Diseases of Flax (Linum usitatissimum). Plants 2023, 12, 2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michielse, C.B.; Rep, M. Pathogen Profile Update: Fusarium oxysporum. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2009, 10, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, J.; Mukarram, M.; Ojo, J.; Dawam, N.; Riyazuddin, R.; Ghramh, H.A.; Khan, K.A.; Chen, R.; Kurjak, D.; Bayram, A. Harnessing Phytohormones: Advancing Plant Growth and Defence Strategies for Sustainable Agriculture. Physiol. Plant. 2024, 176, e14307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilroy, E.; Breen, S. Interplay between Phytohormone Signalling Pathways in Plant Defence–Other than Salicylic Acid and Jasmonic Acid. Essays Biochem. 2022, 66, 657–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.H.; Irving, H.R. Developing a Model of Plant Hormone Interactions. Plant Signal. Behav. 2011, 6, 494–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Shao, Q.; Yin, L.; Younis, A.; Zheng, B. Polyamine Function in Plants: Metabolism, Regulation on Development, and Roles in Abiotic Stress Responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 9, 1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, M.E.; Jasso-Robles, F.I.; Flores-Hernández, E.; Rodríguez-Kessler, M.; Pieckenstain, F.L. Current Status and Perspectives on the Role of Polyamines in Plant Immunity. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2021, 178, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifi, H.S.; Zarei, A.; Hsiang, T.; Shelp, B.J. Spermine Is a Potent Plant Defense Activator Against Gray Mold Disease on Solanum lycopersicum, Phaseolus vulgaris, and Arabidopsis thaliana. Phytopathology 2019, 109, 1367–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambeesan, S.; AbuQamar, S.; Laluk, K.; Mattoo, A.K.; Mickelbart, M.V.; Ferruzzi, M.G.; Mengiste, T.; Handa, A.K. Polyamines Attenuate Ethylene-Mediated Defense Responses to Abrogate Resistance to Botrytis cinerea in Tomato. Plant Physiol. 2012, 158, 1034–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustyniak, B.; Wojtasik, W.; Sawuła, A.; Burgberger, M.; Kulma, A. Spermidine Treatment Limits the Development of the Fungus in Flax Shoots by Suppressing Polyamine Metabolism and Balanced Defence Reactions, Thus Increasing Flax Resistance to Fusariosis. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1561203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boba, A.; Kostyn, K.; Kozak, B.; Zalewski, I.; Szopa, J.; Kulma, A. Transcriptomic Profiling of Susceptible and Resistant Flax Seedlings after Fusarium oxysporum Lini Infection. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Jackson, E.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y. Salicylic Acid and Jasmonic Acid in Plant Immunity. Hortic. Res. 2025, 12, uhaf082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, R.; Stiller, J.; Powell, J.; Rusu, A.; Manners, J.M.; Kazan, K. Fusarium oxysporum Triggers Tissue-Specific Transcriptional Reprogramming in Arabidopsis Thaliana. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thatcher, L.F.; Manners, J.M.; Kazan, K. Fusarium oxysporum Hijacks COI1-mediated Jasmonate Signaling to Promote Disease Development in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2009, 58, 927–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Lu, X.; Hu, Y.; Li, W.; Hong, K.; Mo, Y.; Cahill, D.M.; Xie, J. Methyl Jasmonate Induced Defense Responses Increase Resistance to Fusarium oxysporum f. Sp. Cubense Race 4 in Banana. Sci. Hortic. 2013, 164, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert-Seilaniantz, A.; Grant, M.; Jones, J.D.G. Hormone Crosstalk in Plant Disease and Defense: More Than Just JASMONATE-SALICYLATE Antagonism. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2011, 49, 317–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ton, J.; Flors, V.; Mauch-Mani, B. The Multifaceted Role of ABA in Disease Resistance. Trends Plant Sci. 2009, 14, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boba, A.; Kostyn, K.; Kochneva, Y.; Wojtasik, W.; Mierziak, J.; Prescha, A.; Augustyniak, B.; Grajzer, M.; Szopa, J.; Kulma, A. Abscisic Acid—Defensive Player in Flax Response to Fusarium culmorum Infection. Molecules 2022, 27, 2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boba, A.; Kostyn, K.; Kozak, B.; Wojtasik, W.; Preisner, M.; Prescha, A.; Gola, E.M.; Lysh, D.; Dudek, B.; Szopa, J.; et al. Fusarium oxysporum Infection Activates the Plastidial Branch of the Terpenoid Biosynthesis Pathway in Flax, Leading to Increased ABA Synthesis. Planta 2020, 251, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, X.; Takken, F.L.W.; Tintor, N. How Phytohormones Shape Interactions between Plants and the Soil-Borne Fungus Fusarium oxysporum. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo-González, L.; Deyholos, M.K. RNA-Seq Transcriptome Response of Flax (Linum usitatissimum L.) to the Pathogenic Fungus Fusarium oxysporum f. Sp. Lini. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boba, A.; Kulma, A.; Kostyn, K.; Starzycki, M.; Starzycka, E.; Szopa, J. The Influence of Carotenoid Biosynthesis Modification on the Fusarium culmorum and Fusarium oxysporum Resistance in Flax. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2011, 76, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, S.; Roychoudhury, A. Molecular Crosstalk of Jasmonate with Major Phytohormones and Plant Growth Regulators During Diverse Stress Responses. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2025, 44, 62–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napieraj, N.; Janicka, M.; Reda, M. Interactions of Polyamines and Phytohormones in Plant Response to Abiotic Stress. Plants 2023, 12, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, F.; BusÃ, E.; Carrasco, P. Overexpression of SAMDC1 Gene in Arabidopsis Thaliana Increases Expression of Defense-Related Genes as Well as Resistance to Pseudomonas syringae and Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, R.; Bertea, C.M.; Foti, M.; Narayana, R.; Arimura, G.-I.; Muroi, A.; Horiuchi, J.-I.; Nishioka, T.; Maffei, M.E.; Takabayashi, J. Exogenous Polyamines Elicit Herbivore-Induced Volatiles in Lima Bean Leaves: Involvement of Calcium, H2O2 and Jasmonic Acid. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009, 50, 2183–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Atanasov, K.E.; Murillo, E.; Vives-Peris, V.; Zhao, J.; Deng, C.; Gómez-Cadenas, A.; Alcázar, R. Spermine Deficiency Shifts the Balance between Jasmonic Acid and Salicylic Acid-mediated Defence Responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 2023, 46, 3949–3970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asija, S.; Seth, T.; Umar, S.; Gupta, R. Polyamines and Their Crosstalk with Phytohormones in the Regulation of Plant Defense Responses. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 42, 5224–5246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.V.; Singh, A.; Chakravortty, D. Defence Warriors: Exploring the Crosstalk between Polyamines and Oxidative Stress during Microbial Pathogenesis. Redox Biol. 2025, 83, 103648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blázquez, M.A. Polyamines: Their Role in Plant Development and Stress. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2024, 75, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Wei, B.; Han, J.; Liao, Y.; Liu, Y. Spermidine Increases the Sucrose Content in Inferior Grain of Wheat and Thereby Promotes Its Grain Filling. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, F.; Busó, E.; Lafuente, T.; Carrasco, P. Spermine Confers Stress Resilience by Modulating Abscisic Acid Biosynthesis and Stress Responses in Arabidopsis Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, T.; Bi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Prusky, D. Exogenous Polyamines Enhance Resistance to Alternaria Alternata by Modulating Redox Homeostasis in Apricot Fruit. Food Chem. 2019, 301, 125303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, D.M.; Kazan, K.; Praud, S.; Torney, F.J.; Rusu, A.; Manners, J.M. Early Activation of Wheat Polyamine Biosynthesis during Fusarium Head Blight Implicates Putrescine as an Inducer of Trichothecene Mycotoxin Production. BMC Plant Biol. 2010, 10, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimura, J.; Antoniadi, I.; Široká, J.; Tarkowská, D.; Strnad, M.; Ljung, K.; Novák, O. Plant Hormonomics: Multiple Phytohormone Profiling by Targeted Metabolomics. Plant Physiol. 2018, 177, 476–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittenberg, D.; Foster, G.L. A New Procedure for Quantitative Analysis by Isotope Dilution, with Application to the Determination of Amino Acids and Fatty Acids. J. Biol. Chem. 1940, 133, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanová, T.; Tarkowská, D.; Novák, O.; Hedden, P.; Strnad, M. Analysis of Gibberellins as Free Acids by Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Talanta 2013, 112, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Augustyniak, B.; Petrik, I.; Tarkowska, D.; Burgberger, M.; Wojtasik, W.; Novak, O.; Kulma, A. Dynamic Hormonal Networks in Flax During Fusarium oxysporum Infection and Their Regulation by Spermidine. Molecules 2025, 30, 4631. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234631

Augustyniak B, Petrik I, Tarkowska D, Burgberger M, Wojtasik W, Novak O, Kulma A. Dynamic Hormonal Networks in Flax During Fusarium oxysporum Infection and Their Regulation by Spermidine. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4631. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234631

Chicago/Turabian StyleAugustyniak, Beata, Ivan Petrik, Danuse Tarkowska, Marta Burgberger, Wioleta Wojtasik, Ondrej Novak, and Anna Kulma. 2025. "Dynamic Hormonal Networks in Flax During Fusarium oxysporum Infection and Their Regulation by Spermidine" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4631. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234631

APA StyleAugustyniak, B., Petrik, I., Tarkowska, D., Burgberger, M., Wojtasik, W., Novak, O., & Kulma, A. (2025). Dynamic Hormonal Networks in Flax During Fusarium oxysporum Infection and Their Regulation by Spermidine. Molecules, 30(23), 4631. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234631