The Effect of Roasting on the Health-Promoting Components of Nuts Determined on the Basis of Fatty Acids, Polyphenol Compounds, and Antioxidant Capacity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

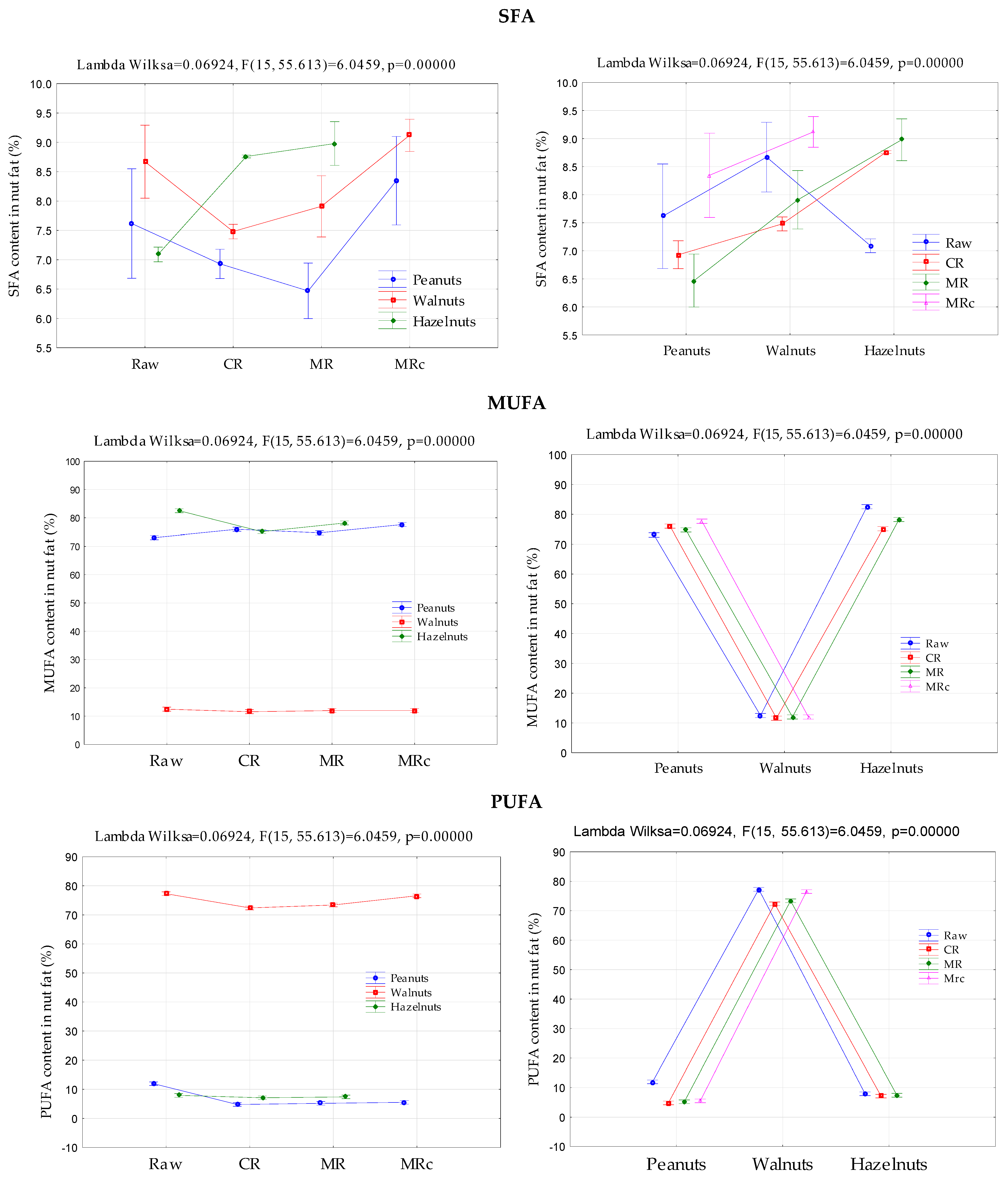

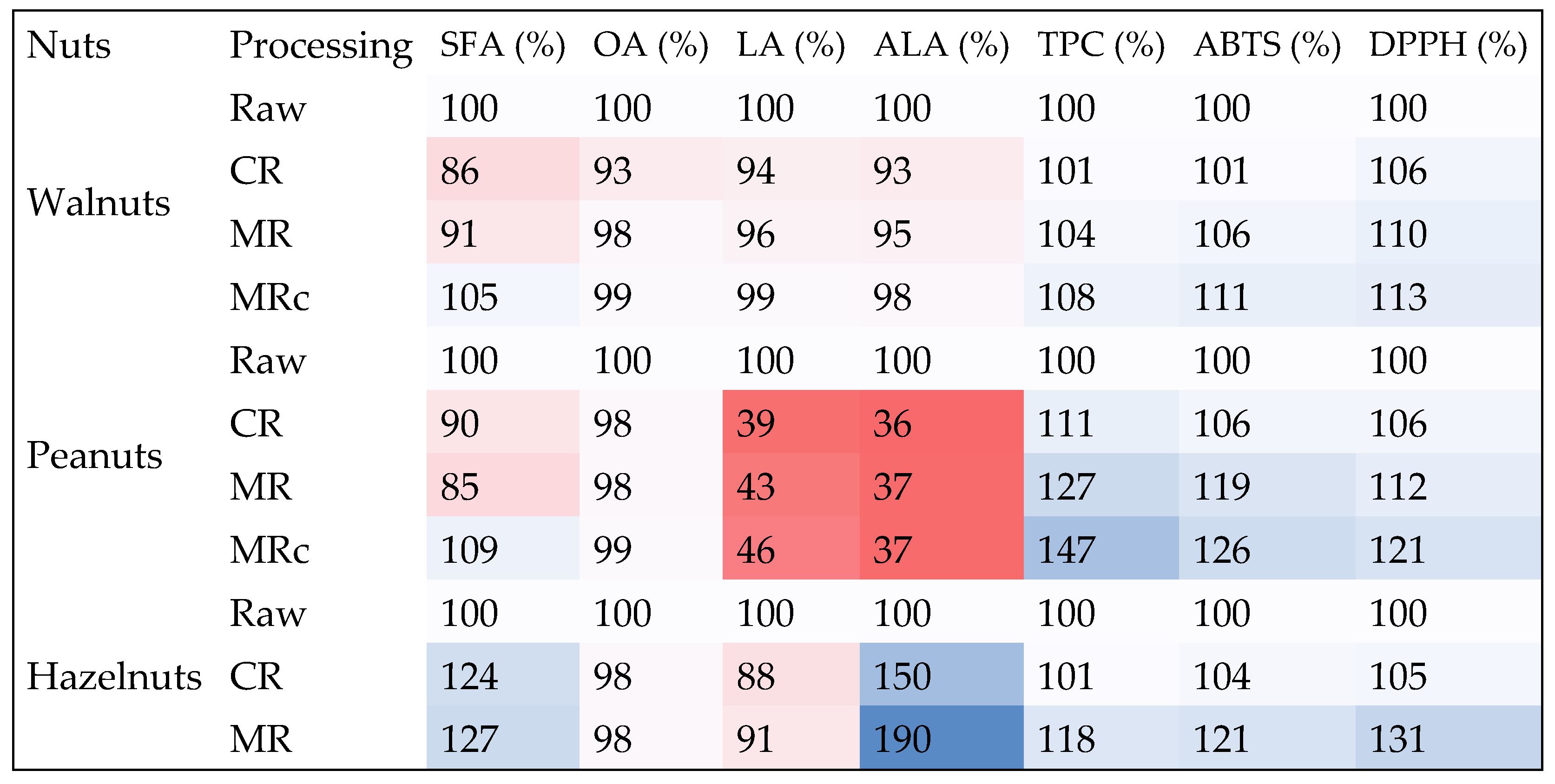

2.1. Fatty Acids Profile

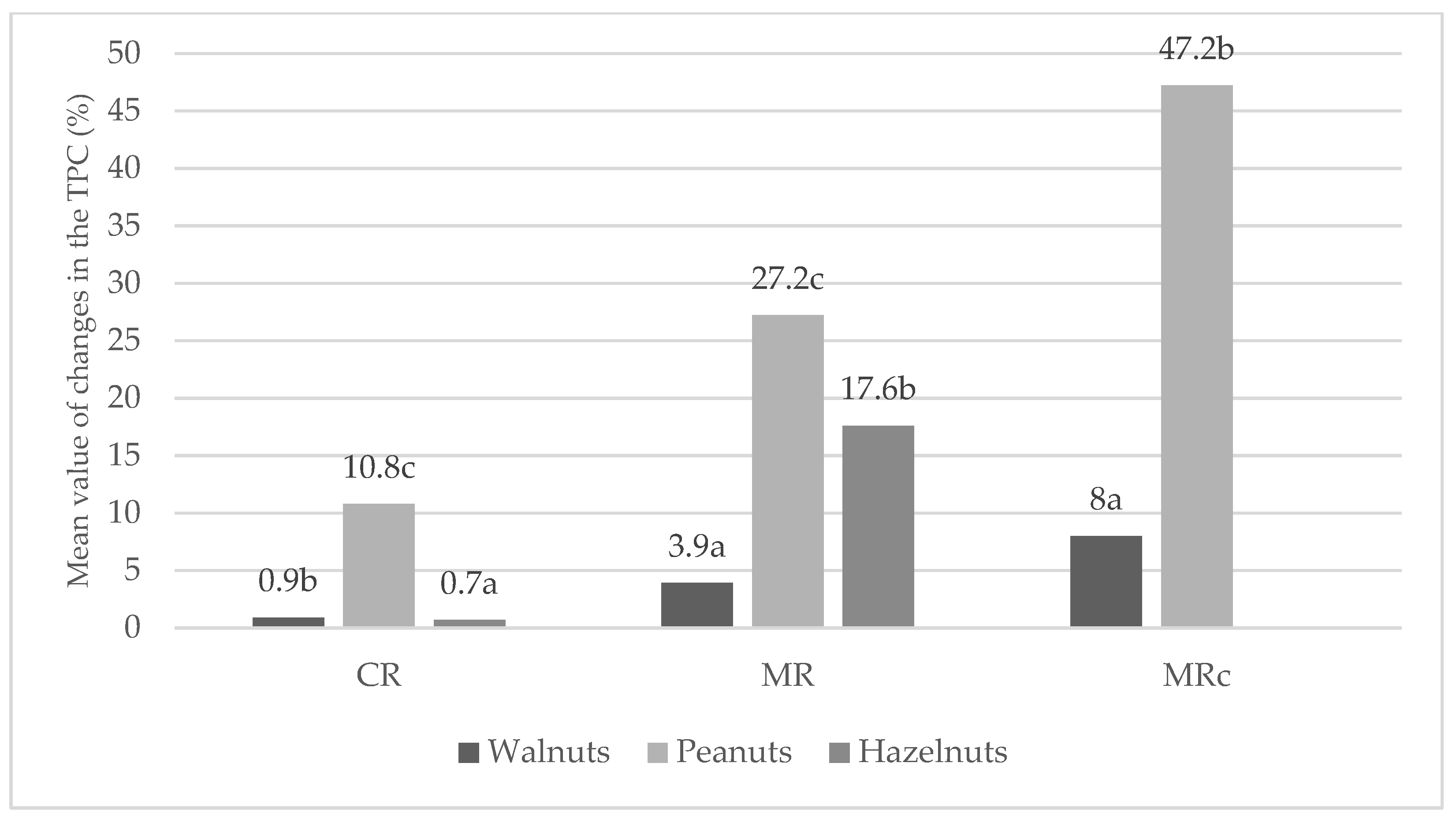

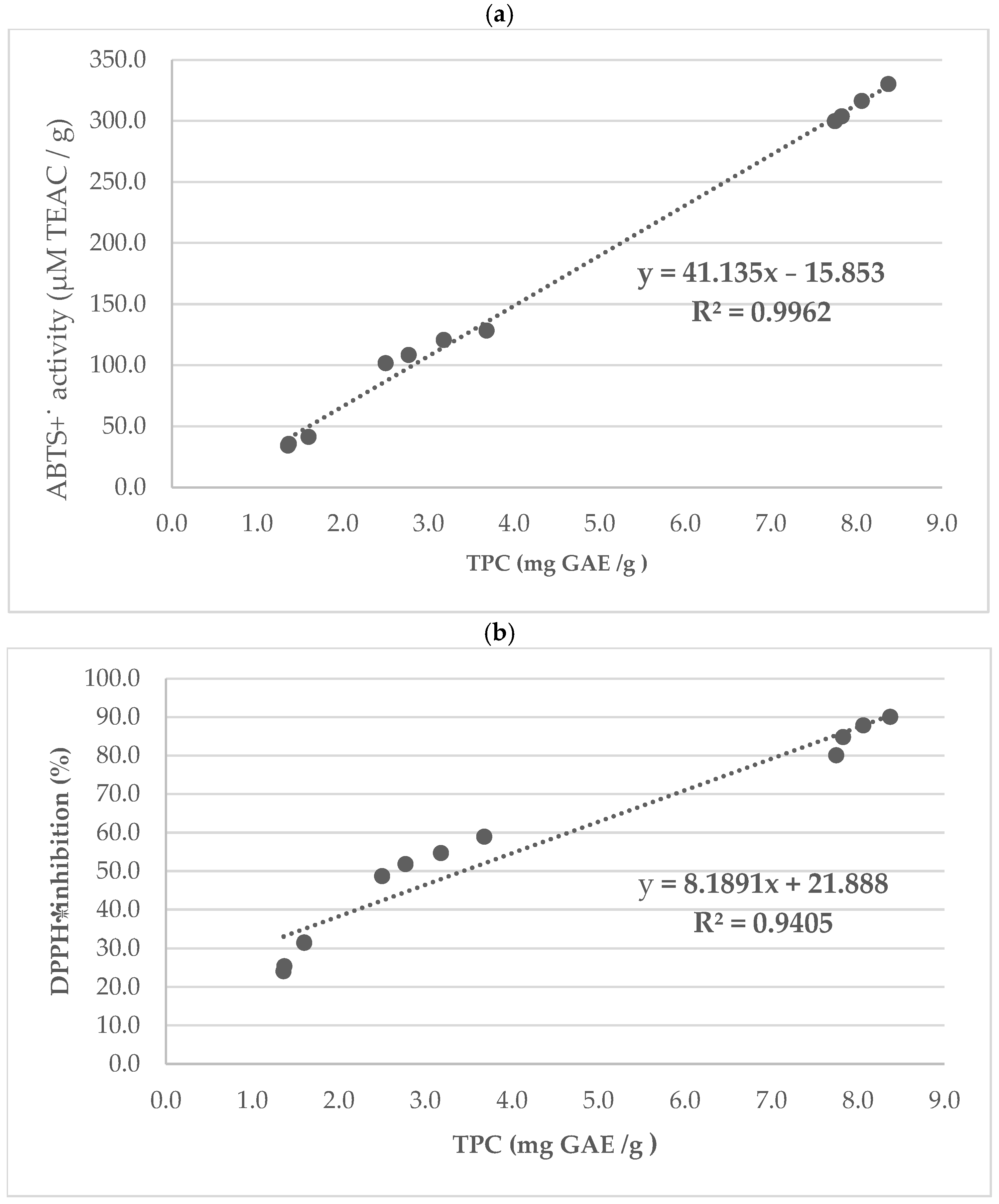

2.2. Antioxidants Capacity

3. Discussion

3.1. Fatty Acids in Nuts

3.2. Antioxidant Capacity

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Roasting Conditions

- (1)

- Convection (CR)—convective roasting was carried out using a laboratory rotary oven (Petrocini, Sant Agostino, Italy). Dry roasting was carried out at 170 °C (i.e., the temperature used during industrial roasting of nuts at the Bakalland factory, Warsaw, Poland). Due to the diverse structure of nuts, the most favorable individual roasting time for each type was selected by trial-and-error (by visual inspection), which was 15 min for walnuts and peanuts and 20 min for hazelnuts.

- (2)

- Microwave—laboratory-scale (MR), roasting was conducted under negative pressure in a microwave-vacuum dryer (PROMIS-TECH Sp. z o.o., Wrocław, Poland), roasting pressure 40 hPa, temperature 60 °C, time varying for individual nuts (due to their different structure and size): 140 s for walnuts and peanuts and 180 s for hazelnuts.

- (3)

- Microwave with a protective coating (MRc)—roasting was conducted under the same conditions as for microwave roasting without a protective coating (as described above). The device was additionally equipped with a system for automatic, uniform spraying of sugar syrup onto walnuts and peanuts, as determined by the company from which the samples were obtained. Industrial maltitol syrup (83°Bx) was used, which, due to its very high viscosity, was diluted with water at a 1:1 (m/m) ratio.

4.3. Methods

4.3.1. The Fatty Acid Composition

Calculation of Changes in the Content of Selected Fatty Acids Expressed as Losses After Nut Roasting (%)

- FA—fatty acid/s

- A—FA content before roasting (raw nuts);

- B—SFA content after roasting (CR, MR, MRc).

4.3.2. Extraction of Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidants

Total Polyphenolic Content (TPC)

Calculation of TPC After Roasting

- A—TPC content before roasting (raw nuts);

- B—nut TPC content after roasting (CR, MR, MRc)

4.3.3. Antioxidant Properties

- (1)

- The method of Brand-Williams et al. [102], modified by Thaipong [103]. This method involves the reduction in the stable azo radical DPPH (1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl) by antioxidants contained in the sample. Color was measured spectrophotometrically at a wavelength of λ = 517 nm (Shimadzu UV-2401 spectrophotometer, Kyoto, Japan, for both assays). Results were expressed as % DPPH radical inhibition.% Inhibition = ((Absorbance sample (nut) − Absorbance control))/(Absorbance control) × 100

- (2)

- Antioxidants reduce ABTS+˙ (oxidized form) to colorless ABTS (reduced form). The decrease in absorbance is a measure of the antioxidant content in the tested material. The measurement was taken at a wavelength of 734 nm. Antioxidant content is expressed as Trolox equivalents (after taking into account the conversions resulting from the standard curve) as μM TEAC (Trolox Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity), calculated per 1g of the tested material.

4.3.4. Statistical Methods

4.3.5. A Heatmap as a Way to Visualize the Impact of the Roasting Process on Selected Components Important for Human Health

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CR | Convectional roasting |

| MR | Microwave roasting |

| MRc | Microwave roasting with a protective coating |

| FA | Fatty acid/s |

| SFA | Saturated fatty acid/s |

| PUFA | Polyunsaturated fatty acid/s |

| ALA | Alpha-linolenic acid C18:3 |

| LA | Linoleic acid C18:2 |

| OA | Oleic acid C18:1 |

| TPC | Total polyphenolic compound |

| ABTS+˙ | 2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid |

| DPPH˙ | 2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid |

References

- Alasalvar, C.; Shahidi, F. Tree nuts: Composition, phytochemicals, and health effects: An overview. In Tree Nuts: Composition, Phytochemicals, and Health Effects; Nutraceutical Science and Technology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros, E. Nuts and CVD. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113 (Suppl. 2), 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorji, N.; Moeini, R.; Memariani, Z. Almond, hazelnut and walnut, three nuts for neuroprotection in Alzheimer’s disease: A neuropharmacological review of their bioactive constituents. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 129, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, J.; Murad, A.L.; Prokop, L.J.; Murad, M.H. Nut consumption and risk of cancer and type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Rev. 2015, 73, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alasalvar, C.; Bolling, B.W. Review of nut phytochemicals, fat-soluble bioactives, antioxidant components and health effects. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113 (Suppl. 2), 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolling, B.; Chen, C.; McKay, D.; Blumberg, J. Tree nut phytochemicals: Composition, antioxidant capacity, bioactivity, impact factors. A systematic review of almonds, Brazils, cashews, hazelnuts, macadamias, pecans, pine nuts, pistachios and walnuts. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2011, 24, 244–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y.; Blumberg, J.B. Phytochemical composition of nuts. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 17 (Suppl. 1), 329–332. [Google Scholar]

- Lainas, K.; Alasalvar, C.; Bolling, B. Effects of roasting on proanthocyanidin contents of Turkish Tombul hazelnut and its skin. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 23, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, L.S.; O’Sullivan, S.M.; Galvin, K.; O’Connor, T.P.; O’Brien, N.M. Fatty acid profile, tocopherol, squalene and phytosterol content of walnuts, almonds, peanuts, hazelnuts and the macadamia nut. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2004, 55, 171–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, E.; Galvin, K.; O’Connor, T.P.; Maguire, A.R.; O’Brien, N.M. Fatty acid profile, tocopherol, squalene and phytosterol content of brazil, pecan, pine, pistachio and cashew nuts. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2006, 57, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlörmann, W.; Birringer, M.; Böhm, V.; Löber, K.; Jahreis, G.; Lorkowski, S.; Müller, A.K.; Schöne, F.; Glei, M. Influence of roasting conditions on health-related compounds in different nuts. Food Chem. 2015, 180, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Na Jom, K.; Ge, Y. Influence of roasting condition on flavor profile of sunflower seeds: A flavoromics approach. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ros, E. Health benefits of nut consumption. Nutrients 2010, 2, 652–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vadivel, V.; Kunyanga, C.N.; Biesalski, H.K. Health benefits of nut consumption with special reference to body weight control. Nutrition 2012, 28, 1089–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alasalvar, C.; Salvadó, J.S.; Ros, E. Bioactives and health benefits of nuts and dried fruits. Food Chem. 2020, 314, 126192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INC. Annual Report 2020/2021, 2022. Available online: https://frutosecosmza.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/1651579968_Statistical_Yearbook_2021-2022.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Zwierczyk, U.; Duplaga, M. Dieta planetarna—Zasady i odniesienie do nawyków żywieniowych ludności w Polsce. Zdr. Publiczne Zarządzanie 2023, 21, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Healthy Claim, 2003. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/nutrition-food-labeling-and-critical-foods/qualified-health-claims-letters-enforcement-discretion (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Borecka, W.; Walczak, Z.; Starzycki, M. Orzech włoski (Juglans regia L.)—Naturalne źródło prozdrowotnych składników żywności. Nauka Przyr. Technol. 2013, 7, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Ciemniewska-Żytkiewicz, H.; Krygier, K.; Bryś, J. Wartość odżywcza orzechów oraz ich znaczenie w diecie. Postępy Tech. Przetwórstwa Spożywczego 2014, 1, 90–96. [Google Scholar]

- Zujko, M.E.; Witkowska, A. Aktywność antyoksydacyjna czekolad, orzechów i nasion. Bromatol. Chem. Toksykol. 2009, XLII, 941–944. [Google Scholar]

- Damavandi, R.D.; Eghtesadi, S.; Shidfar, F.; Heydari, I.; Foroushani, A.R. Efects of hazelnuts consumption on fasting blood sugar and lipoproteins in patients with type 2 diabetes. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2013, 18, 314–321. [Google Scholar]

- Srichamnong, W.; Srzednicki, G. Internal Discoloration of Various Varieties of Macadamia Nuts as Influenced by Enzymatic Browning and Maillard Reaction. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 192, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, J.S.; Casal, S.; Citová, I. Characterization of several hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.) cultivars based in chemical, fatty acid and sterol composition. Eur Food Res. Technol. 2006, 222, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamprese, C.; Ratti, S.; Rossi, M. Effects of roasting conditions on hazelnut characteristics in a two-step process. J. Food Eng. 2009, 95, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekara, N.; Shahidi, F. Effect of roasting on phenolic content and antioxidant activities of whole cashew nuts, kernels, and testa. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 5006–5014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinson, J.A.; Cai, Y. Nuts, especially walnuts, have both antioxidant quantity and efficacy and exhibit significant potential health benefits. Food Funct. 2012, 3, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroga, P.R.; Asensio, C.M.; Nepote, V. Antioxidant effects of the monoterpenes carvacrol, thymol and sabinene hydrate on chemical and sensory stability of roasted sunflower seeds. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2014, 95, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.T.; Liu, S.C.; Hu, C.C.; Shyu, Y.S.; Hsu, C.Y.; Yang, D.J. Effects of roasting temperature and duration on fatty acid composition, phenolic composition, Maillard reaction degree and antioxidant attribute of almond (P.dulcis) kernel. Food Chem. 2016, 190, 520–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hojjati, M.; Noguera-Artiaga, L.; Wojdyło, A. Effects of microwave roasting on physicochemical properties of pistachios (Pistaciavera L.). Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2015, 24, 1995–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megahed, M. Microwave roasting of peanuts: Effects on oil characteristics and composition. Nahrung 2001, 45, 255–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission (EC). Food-Based Dietary Guidelines Recommendations for Nuts and Seeds. Available online: https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa.eu/health-promotion-knowledge-gateway/food-based-dietary-guidelines-europe-table-12_en (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- INC. Nuts & Dried Fruits Statistical Yearbook 2024. Available online: https://inc.nutfruit.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Statistical-Yearbook-2024.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Healthy Roasted Nut Market Consumption Trends: Growth Analysis 2025–2033, 2024. Available online: https://www.datainsightsmarket.com/reports/healthy-roasted-nut-1234494# (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Rajaram, S. Health benefits of plant-derived α-linolenic acid. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Khurana, P.S.; Kansal, R. Choosing quality oil for good health and long life. Indian J. Health Wellbeing 2016, 7, 254–261. [Google Scholar]

- Pedron, G.; Jaouhari, Y.; Bordiga, M. Conventional and Innovative Drying/Roasting Technologies: Effect on Bioactive and Sensorial Profiles in Nuts and Nut-Based Products. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán Sanahuja, A.; Maestre Pérez, S.E.; Grané Teruel, N.; Valdés García, A.; Prats Moya, M.S. Variability of Chemical Profile in Almonds (Prunus dulcis) of Different Cultivars and Origins. Foods 2021, 10, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovic, T.; Debeljak-Martacic, J.; Petrović-Oggiano, G.; Glibetic, M.; Kojadinović, M.; Poštić, M. Fatty acid profiles and antioxidant properties of raw and dried walnuts. Hrana Ishr. 2019, 60, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros, E.; Mataix, J. Fatty acid composition of nuts—Implications for cardiovascular health. Br. J. Nutr. 2006, 96, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, I.; Sousa, A.; Morais, J.S.; Ferreira, I.C.; Bento, A.; Estevinho, L.; Pereira, J.A. Chemical composition, and antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of three hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.) cultivars. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008, 46, 1801–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogeropoulos, N.; Chiou, A.; Ioannou, M.S.; Karathanos, V.T. Nutritional evaluation and health promoting activities of nuts and seeds cultivated in Greece. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 64, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas, J.B.; Naves, M.M.V. Chemical composition of nuts and edible seeds and their relation to nutrition and health. Rev. Nutr. 2010, 23, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köksal, A.İ.; Artik, N.; Şimşek, A.; Güneş, N. Nutrient composition of hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.) varieties cultivated in Turkey. Food Chem. 2006, 99, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, A. Effect of drying methods on fatty acid profile and oil oxidation of hazelnut oil during storage. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2018, 244, 2181–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özcan, M.M. Some nutritional characteristics of fruit and oil of walnut (Juglans regia L.) growing in Turkey. Iran. J. Chem. Chem. Eng. 2009, 28, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Summo, C.; Palasciano, M.; De Angelis, D.; Paradiso, V.M.; Caponio, F.; Pasqualone, A. Evaluation of the chemical and nutritional characteristics of almonds (Prunus dulcis (Mill). DA Webb) as influenced by harvest time and cultivar. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 5647–5655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, J.A.; Oliveira, I.; Sousa, A.; Ferreira, I.C.; Bento, A.; Estevinho, L. Bioactive properties and chemical composition of six walnut (Juglans regia L.) cultivars. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008, 46, 2103–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, J.S.; Casal, S.; Pereira, J.A.; Seabra, R.M.; Oliveira, B.P. Determination of sterol and fatty acid compositions, oxidative stability, and nutritional value of six walnut (Juglans regia L.) cultivars grown in Portugal. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 7698–7702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertürk, U.; Şisman, T.; Yerlikaya, C.; Ertürk, O.; Karadeniz, T. Chemical Composition and Nutritive Value of Selected Walnuts (Juglans regia L.) from Turkey. In Proceedings of the VII International Walnut Symposium, Taiyuan, China, 20–23 July 2013; Volume 1050, pp. 231–234. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, M.Z.; Wang, D.; Tao, X.D.; Wang, Z.Y. Fatty acid compositions and tocopherol concentrations in the oils of 11 varieties of walnut (Juglans regia L.) grown at Xinjiang, China. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2015, 90, 715–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, D.; Angove, M.J.; Tucci, J.; Dennis, C. Walnuts (Juglans regia) chemical composition and research in human health. Crit Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 56, 1231–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Han, J.; Zhao, Z.; Tian, J.; Fu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wei, C.; Liu, W. Roasting treatments affect oil extraction rate, fatty acids, oxidative stability, antioxidant activity, and flavor of walnut oil. Front. Nutr. 2023, 9, 1077081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, L.E.; Dean, L.L. Nutrient composition of raw, dry-roasted, and skin-on cashew nuts. J. Food Res. 2017, 6, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zahrani, M.; Baz, L.; Sandokji, F.; Barnawee, M.; Balgoon, M.; Alazdi, F.; Alharbi, A. A comprehensive study on nutrient content of raw and roasted nuts. Biosci. J. 2024, 40, e40001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafkas, E.; Attar, S.H.; Gundesli, M.A.; Ozcan, A.; Ergun, M. Phenolic and fatty acid profile, and protein content of different walnut cultivars and genotypes (Juglans regia L.) grown in the USA. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 2020, 20, 1711–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özogul, Y.; Özogul, F. Fatty acid profiles of commercially important fish species from the Mediterranean, Aegean and Black Seas. Food Chem. 2007, 100, 1634–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öz, E.; Ekiz Terzioğlu, E.; Savaş, A.; Aoudeh, E.; Abd El-Aty, A.M.; Oz, F. Impact of roasting level on fatty acid composition, oil and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contents of various dried nuts. Turk. J. Agric. For. 2021, 45, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alasalvar, C.; Pelvan, E.; Topal, B. Effects of roasting on oil and fatty acid composition of Turkish hazelnut varieties (Corylus avellana L.). Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2010, 61, 630–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazzawi, H.A.; Al-Ismail, K. A Comprehensive Study on the Effect of Roasting and Frying on Fatty Acids Profiles and Antioxidant Capacity of Almonds, Pine, Cashew, and Pistachio. J. Food Qual. 2017, 2017, 9038257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirbaşlar, F.G.; Türker, G.; Ozsoy Gune, Z.; Ünal, M.; Dülger, B.; Ertaş, E.; Kizilkaya, B. Evaluation of Fatty Acid Composition, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activity, Mineral Composition and Calorie Values of Some Nuts and Seeds from Turkey. Rec. Nat. Prod. 2012, 6, 339–349. [Google Scholar]

- Uslu, N.; Özcan, M. Effect of microwave heating on phenolic compounds and fatty acid composition of cashew (Anacardium occidentale) nut and oil. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2017, 18, 344–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudyal, H.; Panchal, S.K.; Diwan, V.; Brown, L. Omega-3 fatty acids and metabolic syndrome: Effects and emerging mechanisms of action. Prog. Lipid Res. 2011, 50, 372–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mora-Escobedo, R.; Hernández-Luna, P.; Joaquín-Torres, I.C.; Ortiz-Moreno, A.; Robles-Ramírez, M.D.C. Physicochemical properties and fatty acid profile of eight peanut varieties grown in Mexico. CyTA J. Food 2015, 13, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uquiche, E.; Jeréz, M.; Ortíz, J. Effect of pretreatment with microwaves on mechanical extraction yield and quality of vegetable oil from Chilean hazelnuts (Gevuina avellana Mol). Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2008, 9, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Liu, H.; Shi, A.; Liu, L.; Fauconnier, M.L.; Wang, Q. The Effect of Microwave Pretreatment on Micronutrient Contents, Oxidative Stability and Flavor Quality of Peanut Oil. Molecules 2018, 24, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirbaslar, F.G.; Erkmen, G. Investigation of the effect of roasting temperature on the nutritive value of hazelnuts. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2003, 58, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, S.F.; Wiley, V.A.; Knauft, D.A. Comparison of oxidation stability of high-and normal-oleic peanut oils. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1993, 70, 489–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.A.M.; Yalım, N.; Al Juhaimi, F.; Özcan, M.M.; Uslu, N.; Karrar, E. The Effect of Different Roasting Processes on the Total Phenol, Flavonoid, Polyphenol, Fatty Acid Composition and Mineral Contents of Pine Nut (Pinus pinea L.) Seeds. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2025, 19, 238–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akele, M.L.; Nega, Y.; Belay, N.; Kassaw, S.; Derso, S.; Adugna, E.; Desalew, A.; Arega, T.; Tegenu, H.; Mehari, B. Effect of Roasting on the Total Polyphenol Content and Antioxidant Activity of Sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) Seeds Grown in Ethiopia. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 16, 101163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.; You, M.; Toney, A.M.; Kim, J.; Giraud, D.; Xian, Y.; Ye, F.; Gu, L.; Ramer-Tait, A.E.; Chung, S. Red Raspberry Polyphenols Attenuate High-Fat Diet–Driven Activation of NLRP3 Inflammasome and Its Paracrine Suppression of Adipogenesis via Histone Modifications. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2020, 64, 1900995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavez-Guajardo, C.; Ferreira, S.R.S.; Mazzutti, S.; Guerra-Valle, M.E.; Sáez-Trautmann, G.; Moreno, J. Influence of In Vitro Digestion on Antioxidant Activity of Enriched Apple Snacks with Grape Juice. Foods 2020, 9, 1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, L.T.; Lajolo, F.M.; Genovese, M.I. Comparison of phenol content and antioxidant capacity of nuts. Ciên. Tecnol. Aliment. 2010, 30, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donno, D.; Beccaro, G.; Mellano, M.G.; Prima, S.; Cavicchioli, M.; Cerutti, A.; Bounous, G. Setting a Protocol for Hazelnut Roasting using Sensory and Colorimetric Analysis: Influence of the Roasting Temperature on the Quality of Tonda Gentile delle Langhe Cv. Hazelnut. Czech J. Food Sci. 2013, 31, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciemniewska-Żytkiewicz, H.; Verardo, V.; Pasini, F.; Bryś, J.; Koczoń, P.; Caboni, M.F. Determination of lipid and phenolic fraction in two hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.) cultivars grown in Poland. Food Chem. 2015, 168, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Win, M.; Abdulhamid, A.; Baharin, B.S.; Anwar, F. Phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of peanuts skin, hull raw kernel roasted kernel flour. Pak. J. Bot. 2011, 43, 1635–1642. [Google Scholar]

- Fakhriya, S.; Wagdy, S.M.; Singer, F. Comparison between antioxidant activity of phenolic extracts from different parts of peanut. Life Sci. J. 2012, 9, 207–215. [Google Scholar]

- Ghazzawi, H.; Al-Ismail, K. Impact of roasting and frying on fatty acids, and other valuable compounds present in peanuts. Riv. Ital. Sostanze Grasse 2018, 95, 147–153. [Google Scholar]

- Salve, A.R.; LeBlanc, J.G.; Arya, S.S. Effect of processing on polyphenol profile, aflatoxin concentration and allergenicity of peanuts. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 58, 2714–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raisi, M.; Ghorbani, M.; Sadeghi-Mahoonak, A. Effect of storage atmosphere and temperature on the oxidative stability of almond kernels during long term storage. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2015, 62, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobolev, V.S. Vanillin content in boiled peanuts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 3725–3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-González, C.; Ciudad, C.J.; Noé, V.; Izquierdo-Pulido, M. Health benefits of walnut polyphenols: An exploration beyond their lipid profile. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 57, 3373–3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellegrini, N.; Serafini, M.; Salvatore, S. Total antioxidant capacity of spices, dried fruits, nuts, pulses, cereals and sweets consumed in Italy assessed by three different in vitro assays. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2006, 50, 1030–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arranz, S.; Pérez-Jiménez, J.; Saura-Calixto, F. Antioxidant capacity of walnut (Juglans regia L.): Contribution of oil and defatted matter. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2008, 227, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangcharoen, W.; Gomolmanee, S. Antioxidant activity changes during hot-air drying of Moringa oleifera leaves. Maejo Int. J. Sci. Technol. 2013, 7, 353–363. [Google Scholar]

- Açar, Ö.C.; Gökmen, V.; Pellegrini, N.; Fogliano, V. Direct evaluation of the total antioxidant capacity of raw and roasted pulses, nuts and seeds. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2009, 229, 961–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulcin, I. Antioxidant activity of food constituents: An overview. Arch. Toxicol. 2012, 86, 345–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elouafy, Y.; El Idrissi, Z.L.; El Yadini, A.; Harhar, H.; Alshahrani, M.M.; Al Awadh, A.A.; Goh, K.W.; Ming, L.C.; Bouyahya, A.; Tabyaoui, M. Variations in Antioxidant Capacity, Oxidative Stability, and Physicochemical Quality Parameters of Walnut (Juglans regia) Oil with Roasting and Accelerated Storage Conditions. Molecules 2022, 27, 7693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niki, E.; Noguchi, N. Antioxidant Action of Vitamin E in Vivo as Assessed from Its Reaction Products with Multiple Biological Oxidants. Free Radic. Res. 2021, 55, 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunasamy, K.; Shie, L.; Paulraj, P.; Pattammadath, S.; Keeyari Purayil, S.; Chandramohan, M.; Bhavya, K. Effect of Heat Treatment on the Bioactive Components and Antioxidant Activity in Selected Dry Beans and Nuts. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 13, 915–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, I.; Meyer, A.S.; Afonso, S.; Sequeira, A.; Vilela, A.; Goufo, P.; Trindade, H.; Gonçalves, B. Effects of different processing reatments on almond (Prunus dulcis) bioactive compounds, antioxidant activities, fatty acids, and sensorial characteristics. Plants 2020, 9, 1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, I.; Meyer, A.S.; Afonso, S.; Aires, A.; Goufo, P.; Trindade, H.; Gonçalve, B. Phenolic and fatty acid profiles, α-tocopherol and sucrose contents, and antioxidant capacities of understudied Portuguese almond cultivars. J. Food Biochem. 2019, 43, e12887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salín-Sánchez, Á.; Figiel, A.; Hernández, F.; Melgarejo, P.; Lech, K.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á.A. Chemical composition, antioxidant capacity, and sensory quality of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) arils and rind as affected by drying method. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2013, 6, 1644–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Bencomo, J.J.; Kelebek, H.; Sonmezdag, A.S.; Rodriguez-Alcala, L.M.; Fontecha, J.; Selli, S. Characterization of the aroma-active, phenolic, and lipid profiles of the pistachio (Pistacia vera L.) nut as affected by the single and double heating process. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 7830–7839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, M.L.D.L.; Resurreccion, A.V.A. Antioxidant capacity and sensory profiles of peanut skin infusions. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 47, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, K.; Gantner, M.; Piotrowska, A.; Hallmann, E. Effect of Climate and Roasting on Polyphenols and Tocopherols in the Kernels and Skin of Six Hazelnut Cultivars (Corylus avellana L.). Agriculture 2020, 10, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC Official Method 2001.12 Water/Dry Matter (Moisture) in Animal Feed, Grain, and Forage (Plant Tissue): Karl Fischer Titration Methods; AOAC International: Rockville, MD, USA, 2023.

- PN-EN ISO 5509:2001; Vegetable and Animal Oils and Fats—Preparation of Fatty Acid Methyl Esters. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- PN-EN ISO 5508:1996; Vegetable and Animal Oils and Fats—Analysis of Fatty Acid Methyl Esters by Gas Chromatography. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- Slatnar, A.; Mikulic-Petkovsek, M.; Stampar, F.; Veberic, R.; Solar, A. Identification and quantification of phenolic compounds in kernels, oil and bagasse pellets of common walnut (Juglans regia L.). Food Res. Int. 2015, 67, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.; Rossi, J. Colorimetry of Total Phenolic Compounds with Phosphomolybdic-Phosphotungstic Acid Reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 1, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaipong, K.; Boonprakob, U.; Crosby, K.; Cisneros-Zevallos, L.; Byrne, D. Comparison of ABTS, DPPH, FRAP, and ORAC assays for estimating antioxidant activity from guava fruit extracts. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2006, 19, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Nuts | Raw | CR | MR | MRc | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saturated fatty acids (SFA) (%) | Nuts | Roasting | ||||

| Walnuts (n = 9) | 8.67 ± 0.25 b | 7.48 ± 0.05 a | 7.91 ± 0.21 a | 9.12 ± 0.11 b | ||

| Peanuts (n = 9) | 7.62 ± 0.38 b | 6.93 ± 0.10 a | 6.47 ± 0.19 a | 8.30 ± 0.37 c | * | * |

| Hazelnuts (n = 9) | 7.09 ± 0.05 a | 8.76 ± 0.01 b | 8.98 ± 0.15 b | n/s | ||

| Oleic acid C18:1 (OA) (%) | ||||||

| Walnuts (n = 9) | 12.15 ± 0.67 d | 11.35 ± 0.50 a | 11.94 ± 0.34 b | 12.00 ± 0.09 c | * | |

| Peanuts (n = 9) | 73.43 ± 0.10 b | 72.43 ± 0.10 a | 72.37 ± 0.14 a | 73.00 ± 0.26 b | ||

| Hazelnuts (n = 9) | 81.95 ± 0.15 c | 80.02 ± 0.10 a | 80.73 ± 0.18 b | n/s | ||

| Linoleic acid C18:2 (LA) (%) | ||||||

| Walnuts (n = 9) | 61.58 ± 0.86 c | 58.09 ± 0.86 a | 58.86 ± 0.72 b | 61.48 ± 0.43 c | ||

| Peanuts (n = 9) | 8.56 ± 1.03 d | 3.30 ± 0.10 a | 3.65 ± 0.48 b | 3.97 ± 0.31 c | * | * |

| Hazelnuts (n = 9) | 7.92 ± 0.22 b | 6.96 ± 0.10 a | 7.22 ± 0.02 b | n/s | ||

| Alpha-linolenic acid C18:3 (ALA) (%) | ||||||

| Walnuts (n = 9) | 15.18 ± 0.09 c | 14.14 ± 0.13 a | 14.46 ± 0.33 b | 14.94 ± 0.41 bc | ||

| Peanuts (n = 9) | 2.97 ± 0.11 c | 1.08 ± 0.05 a | 1.11 ± 0.09 b | 1.11 ± 0.03 b | * | |

| Hazelnuts (n = 9) | 0.10 ± 0.03 a | 0.15 ± 0.07 b | 0.19 ± 0.10 b | n/s | ||

| Nuts | Raw | CR | MR | MRc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PUFA/SFA * | ||||

| Walnuts (n = 9) | 8.75 a ** | 9.76 b | 9.37 b | 8.21 a |

| Peanuts (n = 9) | 0.95 c | 0.40 a | 0.46 b | 0.44 b |

| Hazelnuts (n = 9) | 0.76 b | 0.82 c | 0.72 a | n/s |

| MUFA/SFA | ||||

| Walnuts (n = 9) | 1.41 b | 1.56 c | 1.53 c | 1.28 a |

| Peanuts (n = 9) | 6.19 b | 6.32 c | 6.74 c | 5.99 a |

| Hazelnuts (n = 9) | 7.93 b | 8.61 c | 7.63 a | n/s |

| OA/LA | ||||

| Walnuts (n = 9) | 0.19 a | 0.19 a | 0.20 ab | 0.19 a |

| Peanuts (n = 9) | 8.57 a | 22.16 d | 20.01 c | 18.43 b |

| Hazelnuts (n = 9) | 10.35 a | 10.74 b | 10.77 b | n/s |

| LA/ALA | ||||

| Walnuts (n = 9) | 4.05 a | 4.10 b | 4.07 a | 4.14 b |

| Peanuts (n = 9) | 2.88 a | 3.06 b | 3.29 c | 3.61 c |

| Hazelnuts (n = 9) | 79.2 c | 46.10 b | 38.01 a | n/s |

| Nuts | Raw | CR | MR | MRc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total phenolic content (TPC) (mg GAE/g) | ||||

| Walnuts (n = 9) | 7.75 ± 0.25 a * | 7.82 ± 0.04 b | 8.05 ± 0.01 c | 8.37 ± 0.04 d |

| Peanuts (n = 9) | 2.50 ± 0.15 a | 2.77 ± 0.07 b | 3.18 ± 0.08 c | 3.68 ± 0.05 d |

| Hazelnuts (n = 9) | 1.36 ± 0.05 a | 1.37 ± 0.02 a | 1.60 ± 0.15 b | n/s |

| ABTS+˙ activity (µM TEAC/g) | ||||

| Walnuts (n = 9) | 299.69 ± 1.78 a | 303.76± 0.48 b | 316.32 ± 1.37 c | 330.17 ± 1.97 d |

| Peanuts (n = 9) | 101.59 ± 0.93 a | 108.11 ± 0.57 b | 120.66 ± 0.84 c | 128.33 ± 0.83 d |

| Hazelnuts (n = 9) | 34.02 ± 0.60 a | 35.53 ± 0.90 a | 41.22 ± 0.93 b | n/s |

| DPPH˙ inhibition (%) | ||||

| Walnuts (n = 9) | 80.08 ± 0.24 a | 84.82 ± 0.34 b | 87.83 ± 0.25 c | 90.6 ± 0.41 d |

| Peanuts (n = 9) | 48.67 ± 1.18 a | 51.82 ± 0.47 b | 54.68 ± 0.28 c | 58.93 ± 0.60 d |

| Hazelnuts (n = 9) | 24.07 ± 0.24 a | 25.37 ± 1.30 b | 31.42 ± 1.23 c | n/s |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kulik, K.; Waszkiewicz-Robak, B. The Effect of Roasting on the Health-Promoting Components of Nuts Determined on the Basis of Fatty Acids, Polyphenol Compounds, and Antioxidant Capacity. Molecules 2025, 30, 4594. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234594

Kulik K, Waszkiewicz-Robak B. The Effect of Roasting on the Health-Promoting Components of Nuts Determined on the Basis of Fatty Acids, Polyphenol Compounds, and Antioxidant Capacity. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4594. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234594

Chicago/Turabian StyleKulik, Klaudia, and Bożena Waszkiewicz-Robak. 2025. "The Effect of Roasting on the Health-Promoting Components of Nuts Determined on the Basis of Fatty Acids, Polyphenol Compounds, and Antioxidant Capacity" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4594. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234594

APA StyleKulik, K., & Waszkiewicz-Robak, B. (2025). The Effect of Roasting on the Health-Promoting Components of Nuts Determined on the Basis of Fatty Acids, Polyphenol Compounds, and Antioxidant Capacity. Molecules, 30(23), 4594. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234594