Adsorption of Imidazolium-Based ILs Combined on Activated Carbon Obtained from Grape Seeds

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Characterization of the Activated Carbons

2.2. Adsorption of Bmim-Based ILs

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Ionic Liquids

3.2. Activated Carbon: Preparation and Characterization

3.3. Adsorption–Desorption Experiments

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IL | Abbreviation |

| Bis–DdmimBr | Dodecane–diyl–bis(methylimidazolium bromide) |

| BmimBF4 | 1–Butyl–3–methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate |

| BmimBr | 1–Butyl–3–methylimidazolium bromide |

| BmimCl | 1–Butyl–3–methylimidazolium chloride |

| BmimMeSO3 | 1–Butyl–3–methylimidazolium methylsulfonate |

| BmimNTf2 | 1–Butyl–3–methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonimide) |

| BmimOTf | 1–Butyl–3–methylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate |

| BmimPF6 | 1–Butyl–3–methylimidazolium hexafluoroborate |

| BmimTFA | 1–Butyl–3–methylimidazolium trifluoroacetate |

| BmpyNTf2 | 1–Butyl–3–methylpyridinium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonimide) |

| BmpyrrBr | 1–Butyl–1–methylpyrrolidinium bromide |

| BpyBr | 1–Butylpyridinium bromide |

| C2NH2Emim | 1–Aminoethyl–3–methylimidazolium |

| DdmimBF4 | 1–Dodecyl–3–methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate |

| DdmimBr | 1–Dodecyl–3–methylimidazolium bromide |

| DdmimCl | 1–Dodecyl–3–methylimidazolium chloride |

| DdmimPF6 | 1–Dodecyl–3–methylimidazolium hexafluoroborate |

| DmimBF4 | 1–Decyl–3–methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate |

| DmimCl | 1–Decyl–3–methylimidazolium chloride |

| DmimPF6 | 1–Decyl–3–methylimidazolium hexafluoroborate |

| EmimBF4 | 1–Ethyl–3–methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate |

| EmimCl | 1–Ethyl–3–methylimidazolium chloride |

| EmimNTf2 | 1–Ethyl–3–methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonimide) |

| EmimPF6 | 1–Ethyl–3–methylimidazolium hexafluoroborate |

| HdmimCl | 1–Methyl–3–hexadecylimidazolium chloride |

| HmimBF4 | 1–Hexyl–3–methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate |

| HmimCl | 1–Hexyl–3–methylimidazolium chloride |

| HmimNTf2 | 1–Hexyl–3–methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonimide) |

| HmimPF6 | 1–Hexyl–3–methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate |

| HOEmim | 1–Hydroxyethyl–3–methylimidazolium |

| MmimCl | 1,3–Dimethylimidazolium chloride |

| OmimBF4 | 1–Methyl–3–octalimidazolium tetrafluoroborate |

| OmimBr | 1–Methyl–3–octalimidazolium bromide |

| OmimCl | 1–Methyl–3–octalimidazolium chloride |

| OmimPF6 | 1–Methyl–3–octalimidazolium hexafluoroborate |

| OmpyrrBr | 1–Octyl–1–methylpyrrolidinium bromide |

| OpyBr | 1–Octylpyridinium bromide |

| PmimBF4 | 1–Pentyl–3–methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate |

| PrmimNTf2 | 1–Methyl–3–propilimidazolium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonimide) |

| TdmimCl | 1–Methyl–3–tetradecylimidazolium chloride |

References

- Markiewicz, M.; Piszora, M.; Caicedo, N.; Jungnickel, C.; Stolte, S. Toxicity of Ionic Liquid Cations and Anions towards Activated Sewage Sludge Organisms from Different Sources-Consequences for Biodegradation Testing and Wastewater Treatment Plant Operation. Water Res. 2013, 47, 2921–2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siciliano, A.; Russo, D.; Spasiano, D.; Marotta, R.; Race, M.; Fabbricino, M.; Galdiero, E.; Guida, M. Chronic Toxicity of Treated and Untreated Aqueous Solutions Containing Imidazole-Based Ionic Liquids and Their Oxydized by-Products. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 180, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quijano, G.; Couvert, A.; Amrane, A.; Darracq, G.; Couriol, C.; Le Cloirec, P.; Paquin, L.; Carrié, D. Toxicity and Biodegradability of Ionic Liquids: New Perspectives towards Whole-Cell Biotechnological Applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 174, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amde, M.; Liu, J.; Pang, L. Environmental Application, Fate, Effects and Concerns of Ionic Liquids: A Review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 12611–12627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Docherty, K.M.; Kulpa, C.F., Jr. Toxicity and Antimicrobial Activity of Imidazolium and Pyridinium Ionic Liquids. Green. Chem. 2005, 7, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, J.; Pawlik, M.; Bryniok, D.; Thöming, J.; Stolte, S. Biodegradation Potential of Cyano-Based Ionic Liquid Anions in a Culture of Cupriavidus Spp. and Their in Vitro Enzymatic Hydrolysis by Nitrile Hydratase. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 9495–9505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolte, S.; Steudte, S.; Areitioaurtena, O.; Pagano, F.; Thöming, J.; Stepnowski, P.; Igartua, A. Ionic Liquids as Lubricants or Lubrication Additives: An Ecotoxicity and Biodegradability Assessment. Chemosphere 2012, 89, 1135–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, S.P.F.; Pinto, P.C.A.G.; Saraiva, M.L.M.F.S.; Rocha, F.R.P.; Santos, J.R.P.; Monteiro, R.T.R. The Aquatic Impact of Ionic Liquids on Freshwater Organisms. Chemosphere 2015, 139, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, A.; Gathergood, N. Biodegradation of Ionic Liquids—A Critical Review. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 8200–8237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, S.P.F.; Pinto, P.C.A.G.; Lapa, R.A.S.; Saraiva, M.L.M.F.S. Toxicity Assessment of Ionic Liquids with Vibrio Fischeri: An Alternative Fully Automated Methodology. J. Hazard. Mater. 2015, 284, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena, I.F.; Diaz, E.; Palomar, J.; Rodriguez, J.J.; Mohedano, A.F. Cation and Anion Effect on the Biodegradability and Toxicity of Imidazolium e and Choline e Based Ionic Liquids. Chemosphere 2020, 240, 124947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena, I.F.; Diaz, E.; Rodriguez, J.J.; Mohedano, A.F. An Overview of Ionic Liquid Degradation by Advanced Oxidation Processes. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 52, 2844–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, W.L.; Leal, B.C.; Ziulkoski, A.L.; van Leeuwen, P.W.; dos Santos, J.H.Z.; Schrekker, H.S. Petrochemical Residue-Derived Silica-Supported Titania-Magnesium Catalysts for the Photocatalytic Degradation of Imidazolium Ionic Liquids in Water. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 218, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calza, P.; Fabbri, D.; Noè, G.; Santoro, V.; Medana, C. Assessment of the Photocatalytic Transformation of Pyridinium-Based Ionic Liquids in Water. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 341, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, C.M.; Munoz, M.; Quintanilla, A.; de Pedro, Z.M.; Ventura, S.P.M.; Coutinho, J.A.P.; Casas, J.A.; Rodriguez, J.J. Degradation of Imidazolium-Based Ionic Liquids in Aqueous Solution by Fenton Oxidation. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2014, 89, 1197–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, M.; Domínguez, C.M.; de Pedro, Z.M.; Quintanilla, A.; Casas, J.A.; Rodriguez, J.J. Degradation of Imidazolium-Based Ionic Liquids by Catalytic Wet Peroxide Oxidation with Carbon and Magnetic Iron Catalysts. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2016, 91, 2882–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- de Oliveira Marcionilio, S.M.L.; Crisafulli, R.; Medeiros, G.A.; de Sousa Tonhá, M.; Garnier, J.; Neto, B.A.D.; Linares, J.J. Influence of Hydrodynamic Conditions on the Degradation of 1-Butyl-3-Methylimidazolium Chloride Solutions on Boron-Doped Diamond Anodes. Chemosphere 2019, 224, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieczyńska, A.; Ofiarska, A.; Borzyszkowska, A.F.; Białk-Bielińska, A.; Stepnowski, P.; Stolte, S.; Siedlecka, E.M. A Comparative Study of Electrochemical Degradation of Imidazolium and Pyridinium Ionic Liquids: A Reaction Pathway and Ecotoxicity Evaluation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2015, 156, 522–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poza-Nogueiras, V.; Arellano, M.; Rosales, E.; Pazos, M.; Sanromán, M.A.; González-Romero, E. Electroanalytical Techniques Applied to Monitoring the Electro-Fenton Degradation of Aromatic Imidazolium-Based Ionic Liquids. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2018, 48, 1331–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocos, E.; González-Romero, E.; Pazos, M.; Sanromán, M.A. Application of Electro-Fenton Treatment for the Elimination of 1-Butyl-3-Methylimidazolium Triflate from Polluted Water. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 318, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, M.; Domínguez, C.M.; De Pedro, Z.M.; Quintanilla, A.; Casas, J.A.; Ventura, S.P.M.; Coutinho, J.A.P. Role of the Chemical Structure of Ionic Liquids in Their Ecotoxicity and Reactivity towards Fenton Oxidation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2015, 150, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena, I.F.; Cotillas, S.; Díaz, E.; Sáez, C.; Mohedano, Á.F.; Rodrigo, M.A. Sono- and Photoelectrocatalytic Processes for the Removal of Ionic Liquids Based on the 1-Butyl-3-Methylimidazolium Cation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 372, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena, I.F.; Cotillas, S.; Díaz, E.; Sáez, C.; Rodríguez, J.J.; Cañizares, P.; Mohedano, Á.F.; Rodrigo, M.A. Electrolysis with Diamond Anodes: Eventually, There Are Refractory Species! Chemosphere 2018, 195, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemus, J.; Palomar, J.; Heras, F.; Gilarranz, M.A.; Rodriguez, J.J. Developing Criteria for the Recovery of Ionic Liquids from Aqueous Phase by Adsorption with Activated Carbon. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2012, 97, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedidi, H.; Lakehal, I.; Reinert, L.; Lévêque, J.M.; Bellakhal, N.; Duclaux, L. Removal of Ionic Liquids and Ibuprofen by Adsorption on a Microporous Activated Carbon: Kinetics, Isotherms, and Pore Sites. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markets and Markets. Activated Carbon Market by Type (Powdered Activated Carbon, Granular Activated Carbon), Application (Liquid Phase Application, and Gas Phase Application), End-Use Industry, Raw Material (Coal, Coconut, Wood, Peat), and Region—Global Forecast to 2030; Markets and Markets: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Grand View Research. Activated Carbon Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By Type (Powdered, Granular), By Application (Liquid Phase, Gas Phase) By End-use (Water Treatment, Air Purification), By Region, And Segment Forecasts, 2023–2030; Grand View Research: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, S.; Shah, S.S.A.; Altaf, M.; Hossain, I.; El Sayed, M.E.; Kallel, M.; El-Bahy, Z.M.; Rehman, A.U.; Najam, T.; Nazir, M.A. Activated Carbon Derived from Biomass for Wastewater Treatment: Synthesis, Application and Future Challenges. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2024, 179, 106480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, E.; Manzano, F.J.; Villamil, J.; Rodriguez, J.J.; Mohedano, A.F. Low-Cost Activated Grape Seed-Derived Hydrochar through Hydrothermal Carbonization and Chemical Activation for Sulfamethoxazole Adsorption. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 5127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okman, I.; Karagöz, S.; Tay, T.; Erdem, M. Activated Carbons from Grape Seeds by Chemical Activation with Potassium Carbonate and Potassium Hydroxide. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 293, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Bahri, M.; Calvo, L.; Gilarranz, M.A.; Rodriguez, J.J. Activated Carbon from Grape Seeds upon Chemical Activation with Phosphoric Acid: Application to the Adsorption of Diuron from Water. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 203, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Fan, M.; Sun, K.; Cheng, X.; Wu, F.; Zhang, S.; Hu, X. Chemical Activation of Willow with Co-Presence of FeCl3 Tailors Pore Structure of Activated Carbon for Enhanced Adsorption of Phenol and Tetracycline. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 975, 179302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, M.; Belver, C.; Bedia, J. Effect of Synthesis Conditions on the Porous Texture of Activated Carbons Obtained from Tara Rubber by FeCl3 Activation. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, M.; Fiori, L. From Olive Waste to Solid Biofuel through Hydrothermal Carbonisation: The Role of Temperature and Solid Load on Secondary Char Formation and Hydrochar Energy Properties. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2017, 124, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encinar, J.M.; Beltrán, F.J.; Bernalte, A.; Ramiro, A.; González, J.F. Pyrolysis of Two Agricultural Residues: Olive and Grape Bagasse. Influence of Particle Size and Temperature. Biomass Bioenergy 1996, 11, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrero-López, A.M.; Fierro, V.; Jeder, A.; Ouederni, A.; Masson, E.; Celzard, A. High Added-Value Products from the Hydrothermal Carbonisation of Olive Stones. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 9859–9869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touhami, D.; Zhu, Z.; Balan, W.S.; Janaun, J.; Haywood, S.; Zein, S. Characterization of Rice Husk-Based Catalyst Prepared via Conventional and Microwave Carbonisation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 2388–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, B.; Pandey, N.; Bisht, Y.; Singh, R.; Kumar, J.; Bhaskar, T. Pyrolysis of Agricultural Biomass Residues: Comparative Study of Corn Cob, Wheat Straw, Rice Straw and Rice Husk. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 237, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uçar, S.; Karagöz, S. The Slow Pyrolysis of Pomegranate Seeds: The Effect of Temperature on the Product Yields and Bio-Oil Properties. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2009, 84, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Cordero, D.; Heras, F.; Gilarranz, M.A.; Raymundo-Piñero, E. Grape Seed Carbons for Studying the Influence of Texture on Supercapacitor Behaviour in Aqueous Electrolytes. Carbon 2014, 71, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnomo, C.W.; Castello, D.; Fiori, L. Granular Activated Carbon from Grape Seeds Hydrothermal Char. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomar, J.; Lemus, J.; Gilarranz, M.A.; Rodriguez, J.J. Adsorption of Ionic Liquids from Aqueous Effluents by Activated Carbon. Carbon 2009, 47, 1846–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, A.; Reinert, L.; Levêque, J.M.; Papaiconomou, N.; Irfan, N.; Duclaux, L. Adsorption of Ionic Liquids onto Activated Carbons: Effect of PH and Temperature. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2012, 158, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.; Duclaux, L.; Lévêque, J.M.; Reinert, L.; Farooq, A.; Yasin, T. Effect of Cation Type, Alkyl Chain Length, Adsorbate Size on Adsorption Kinetics and Isotherms of Bromide Ionic Liquids from Aqueous Solutions onto Microporous Fabric and Granulated Activated Carbons. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 144, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, C.M.S.S.; Lemus, J.; Freire, M.G.; Palomar, J.; Coutinho, J.A.P. Enhancing the Adsorption of Ionic Liquids onto Activated Carbon by the Addition of Inorganic Salts. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 252, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Wang, H.; Ren, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Geng, Y.; Wu, L.; Pu, X. Adsorption of Imidazolium-Based Ionic Liquid on Sodium Bentonite and Its Effects on Rheological and Swelling Behaviors. Appl. Clay Sci. 2019, 182, 105248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, K.; Qiu, Y.; Ben, L.; Stenstrom, M.K. Effectiveness and Potential of Straw- and Wood-Based Biochars for Adsorption of Imidazolium-Type Ionic Liquids. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2016, 130, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Sun, L.; Zhou, Y.; Gao, B.; Gao, W.; Bao, C.; Feng, C.; Li, Y. Biosorbents Based on Agricultural Wastes for Ionic Liquid Removal: An Approach to Agricultural Wastes Management. Chemosphere 2016, 165, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, F.; Zhou, Y.; Gao, B.; Qiao, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, E.; Pang, L.; Bao, C. Effective Removal of Ionic Liquid Using Modified Biochar and Its Biological Effects. J. Taiwan. Inst. Chem. Eng. 2016, 67, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ushiki, I.; Tashiro, M.; Smith, R.L. Measurement and Modeling of Adsorption Equilibria of Imidazolium-Based Ionic Liquids on Activated Carbon from Aqueous Solutions. Fluid. Phase Equilib. 2017, 441, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Fu, H.; Zhang, H.; Liu, H.; Wan, Y.; Zheng, S.; Xu, Z. Microporous Zeolite-Templated Carbon as an Adsorbent for the Removal of Long Alkyl-Chained Imidazolium-Based Ionic Liquid from Aqueous Media. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2018, 260, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Cao, W.; Alvarez, P.J.J.; Qu, X.; Fu, H.; Zheng, S.; Xu, Z.; Zhu, D. Oxidized Template-Synthesized Mesoporous Carbon with PH-Dependent Adsorption Activity: A Promising Adsorbent for Removal of Hydrophilic Ionic Liquid. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 440, 821–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Delgado, C.; Fresno, T.; Rodríguez-Santamaría, J.J.; Diaz, E.; Mohedano, A.F.; Moreno-Jimenez, E. Co-Application of Activated Carbon and Compost to Contaminated Soils: Toxic Elements Mobility and PAH Degradation and Availability. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 16, 1057–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemus, J.; Palomar, J.; Gilarranz, M.A.; Rodriguez, J.J. On the Kinetics of Ionic Liquid Adsorption onto Activated Carbons from Aqueous Solution. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 2969–2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, E.; Monsalvo, V.M.; Lopez, J.; Mena, I.F.; Palomar, J.; Rodriguez, J.J.; Mohedano, A.F. Assessment the Ecotoxicity and Inhibition of Imidazolium Ionic Liquids by Respiration Inhibition Assays. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 162, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedia, J.; Peñas-Garzón, M.; Gómez-Avilés, A.; Rodriguez, J.; Belver, C. A Review on the Synthesis and Characterization of Biomass-Derived Carbons for Adsorption of Emerging Contaminants from Water. C 2018, 4, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zazo, J.A.; Fraile, A.F.; Rey, A.; Bahamonde, A.; Casas, J.A.; Rodriguez, J.J. Optimizing Calcination Temperature of Fe/Activated Carbon Catalysts for CWPO. Catal. Today 2009, 143, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ILs | Material | Treatment | AC Characteristics | Adsorption Tests | Adsorption Capacity (mmol g–1) | Significant Results/ Best Operating Conditions | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

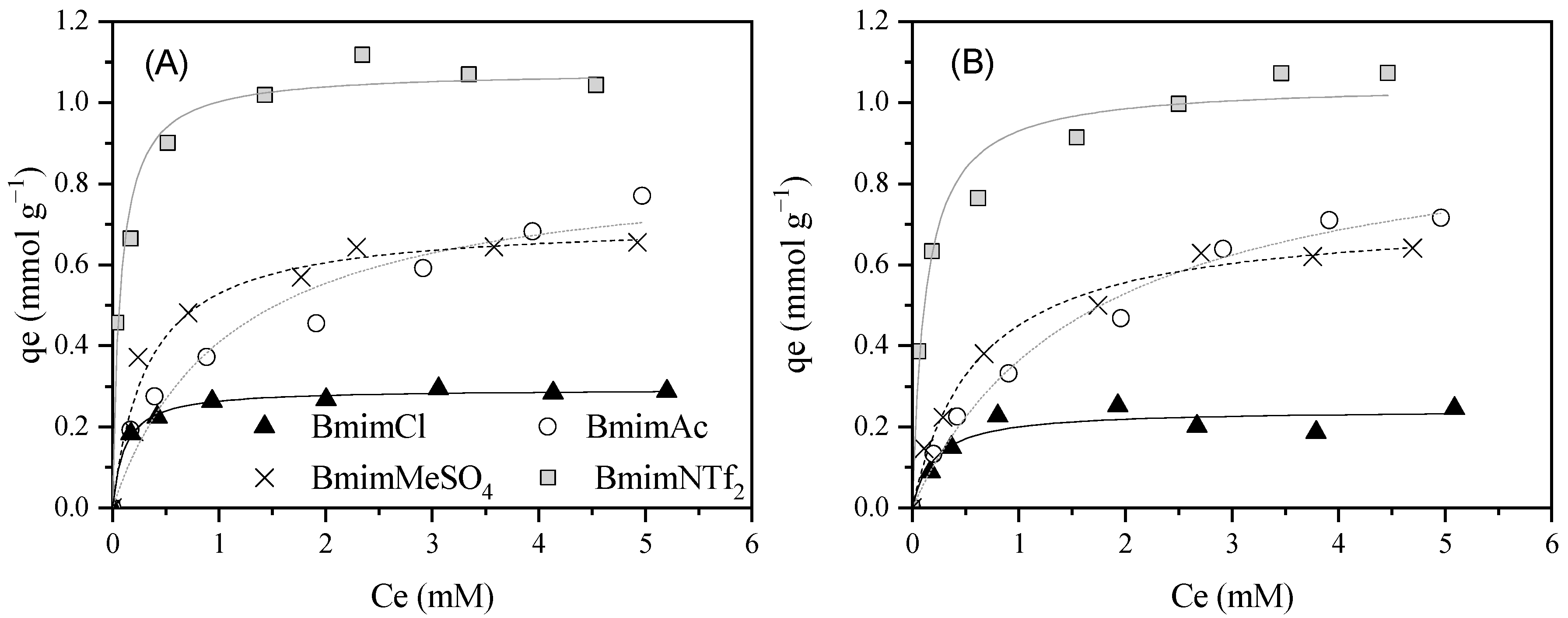

| BmimBF4 BmimCl BmimMeSO3 BmimNTf2 BmimOTf BmimPF6 EmimNTf2 HmimCl HmimPF6 OmimBF4 OmimCl OmimPF6 | Commercial AC (Merck) | No treatment, Thermal treatment (900 °C) Nitric acid oxidation (900 °C) Ammonium persulfate oxidations (900 °C) | ABET = 494–932 m2 g−1 | C0 = 0–5 mM W = 250 mg L−1 T = 25–55 °C Neutral pH | qL = 0.14–1.3 | qL = 1.32 mmolOmim+ g−1 IL: OmimPF6 T: 35 °C AC: similar in all cases | Palomar et al., 2009 [42] |

| BmimCl OmimCl OpyBr | 2 commercial ACs (China and Calgon) Artichokes | The commercial carbons were washed and dried (110 °C) Artichokes were activated using phosphoric acid | ABET = 984–2106 m2 g−1 pHPZC = 6–9.5 | C0 = 0–20 mM W = 1000–2000 mg L−1 T = 20–55 °C pH = 2–9 | qe = 0.4–2.3 | qe = 2.3 mmolOmim+ g−1 IL: OmimCl pH: 9 AC: Artichokes AC (pHPZC = 6; highest O content) | Farooq et al., 2012 [43] |

| EmimCl BmimCl HmimCl OmimCl DmimCl DdmimCl TdmimCl HdmimCl EmimBF4 BmimBF4 HmimBF4 OmimBF4 DmimBF4 DdmimBF4 EmimPF6 BmimPF6 HmimPF6 OmimPF6 DmimPF6 DdmimPF6 EmimNTf2 PrmimNTf2 BmimNTf2 HmimNTf2 BmimOTf BmimTFA BmimMeSO3 | 5 commercial ACs (CAPSUPER, SXPLUS, GXS, Merck and ENA250G), silica and alumina | No treatment, thermal treatment (900 °C) and nitric acid oxidation. | ABET = 79–1915 m2 g−1 pHSlurry= 3.3–8.1 | C0 = 0–5 mM W = 250 mg L−1 T = 35 °C Neutral pH | qL = 0.05–3.5 | qL = 3.5 mmolOmim+ g−1 IL: OmimPF6 T: 35 °C AC: CAPSUPER (highest ABET) | Lemus et al., 2012 [24] |

| BmimBr OmimBr DdmimBr Bis–DdmimBr BmpyrrBr OmpyrrBr BpyBr OpyBr | 2 commercial ACs (China and fabric AC (900-20 from Kuraray)) | Washed with HCl and Milli-Q water and dried (110 °C) | ABET = 1044–1910 m2 g−1 pHPZC = 8–8.7 | C0 = 0–10 mM W = 2000 mg L−1 T = 25–55 °C pH = 7 | qL = 0.23–1.4 | qL = 1.4 mmolDdmim+ g−1 IL: OmimPF6 T: 35 °C AC: fabric AC (highest ABET and micropore area) | Hassan et al., 2014 [44] |

| BmimCl Bmim MeSO3 BmimOTf BmimNTf2 BmpyNTf2 | Commercial AC (Merck) | No treatment | ABET = 927 m2 g−1 | C0 = 100–500 mg L−1 W = 250 mg L−1 T = 35 °C Neutral pH Na2SO4 = 0–1.76 mM | qL = 0.13–1.41 | qL = 1.41 mmolBmpy+ g−1 IL: BmpyNTf2 T: 35 °C AC: Merck | Neves et al., 2014 [45] |

| EmimCl HmimCl OmimCl BmimTFA BmimBF4 BmimOTf BmimPF6 BmimNTf2 | Cellulose | Hydrothermal carbonization (250 °C, 10 h) and KOH activation (400–800 °C) | ABET = 289–838 m2 g−1 | C0 = 0–5 mM W = 2500 mg L−1 T = 25 °C Neutral pH | qL = 0.43–0.95 | qL = 0.95 mmolOmim+ g−1 IL: OmimCl T: 25 °C AC: Cellulose AC | Wang et al., 2015 [46] |

| EmimBF4 EmimPF6 EmimNTf2 BmimBF4 PmimBF4 | Straw ashes Wood | Straw ashes: washed with HCl and water Wood: slow pyrolysis (700 °C, 6 h) | ABET = 465–1268 m2 g−1 | C0 = 0.5–3 mM W = 4000 mg L−1 T = 25 °C Neutral pH | qL = 0.15–0.40 | qL = 0.4 mmolPmim+ g−1 IL: PmimBF4 T: 25 °C AC: Cellulose AC | Shi et al., 2016 [47] |

| BmimCl | Peanut shell Corn stalk Wheat straw | Pyrolysis (700 °C, 2 h), KOH activation (700 °C, 2 h) and washed with HCl and water. Oxidation with (NH4)2S2O8 at room temperature | ABET = 1283–1347 m2 g−1 | C0 = 0–8 mM W = 1200 mg L−1 T = 25 °C pH: 4.0–10.0 | qL = 0.61–0.85 | qL = 0.85 mmolBmim+ g−1 IL: BmimCl T: 25 °C AC: Peanut shell AC oxidized with (NH4)2S2O8 | Yu et al., 2016a [48] |

| BmimCl | Bamboo | Pyrolysis (700 °C, 2 h), KOH activation (700 °C, 2 h) and washed with HCl and water. Oxidation with (NH4)2S2O8 at room temperature | ABET = 1137–1195 m2 g−1 | C0 = 0–8 mM W = 1200 mg L−1 T = 25 °C pH: 4.0–10.0 | qL = 0.51–0.56 | qL = 0.56 mmolBmim+ g−1 IL: BmimCl T: 25 °C AC: Bamboo Ac oxidized with (NH4)2S2O8 | Yu et al., 2016b [49] |

| BmimCl HmimCl OmimCl | Cambridge filter Japan AC | Introduced in an adsorption column | ABET = 1300 m2 g−1 | C0 = 2.74 mM W = 1200 mg L−1 T = 30–50 °C Neutral pH | qL = 0.40–0.70 | qL = 0.70 mmolOmim+ g−1 IL: OmimCl T: 30 °C AC: Cambridge filter Japan AC | Ushiki et al., 2017 [50] |

| BmimCl OmimCl HdmimCl | Ordered microporous carbon ZTC, ordered mesoporous carbon CMK–3 and 2 commercial AC (coconut-shell-derived activated carbon (HuaJing Co.), Filtrasorb-300 (Calgon Carbon Co.)) | Ordered microporous carbon: Y zeolite with chemical carbon deposition of acetylene (550 °C, 5 h) and pyrolysis (850 °C, 6 h). Ordered mesoporous carbon: SBA-15 mixed with sucrose, pyrolysis (850 °C, 6 h). Both materials were washed with HF and water to remove the zeolite. | ABET = 631–1610 m2 g−1 | C0 = 0–1.25 mM W = 250–750 mg L−1 T = 20 °C pH: 3.5–10.0 | qL = 0.18–3.40 | qL = 3.40 mmolHdmim+ g−1 IL: HdmimCl T: 20 °C AC: Ordered microporous carbon ZTC | Zhang et al., 2018a [51] |

| BmimCl | Ordered mesoporous carbon CMK–3 and AC (Filtrasorb-300, Calgon) | Ordered mesoporous carbon: SBA-15 mixed with sucrose, pyrolysis (850 °C, 5 h) and washed with HF and water to remove the silica. Both materials were oxidized using HNO3 | ABET = 762–1078 m2 g−1 | C0 = 0–0.98 mM W = 250 mg L−1 T = 25–45 °C pH: 2.0–10.0 | qL = 0.23–0.87 | qL = 0.87 mmolBmim+ g−1 IL: BmimCl T: 25 °C AC: OMC oxidized with 6 M HNO3 | Zhang et al., 2018b [52] |

| Material | Adsorption-Desorption N2 Isotherm | Elemental Analysis | Ash (%) | TPD | pHslurry | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABET (m2/g) | Vmeso (cm3/g) | Vmicro (cm3/g) | C (%) | H (%) | N (%) | S (%) | O * (%) | CO (µmol/g) | CO2 (µmol/g) | |||

| Merck | 882 | 0.040 | 0.368 | 89.54 | 0.67 | 0.53 | 0.73 | 3.79 | 4.73 | 544 | 322 | 7.7 |

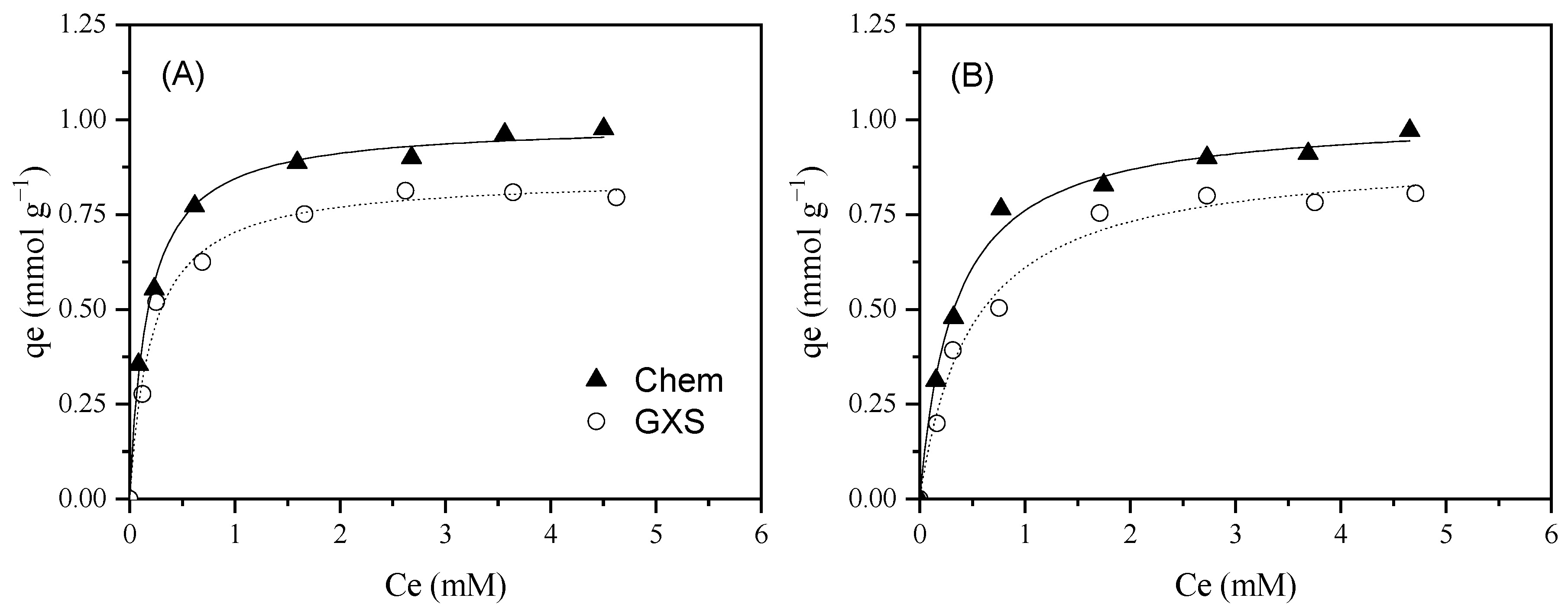

| Chem | 1392 | 0.170 | 0.549 | 84.30 | 0.25 | 1.30 | 0.09 | 9.26 | 4.80 | 1157 | 542 | 6.2 |

| GXS | 1065 | 0.270 | 0.391 | 86.70 | 1.00 | 0.58 | 0.78 | 2.53 | 8.41 | 785 | 350 | 5.0 |

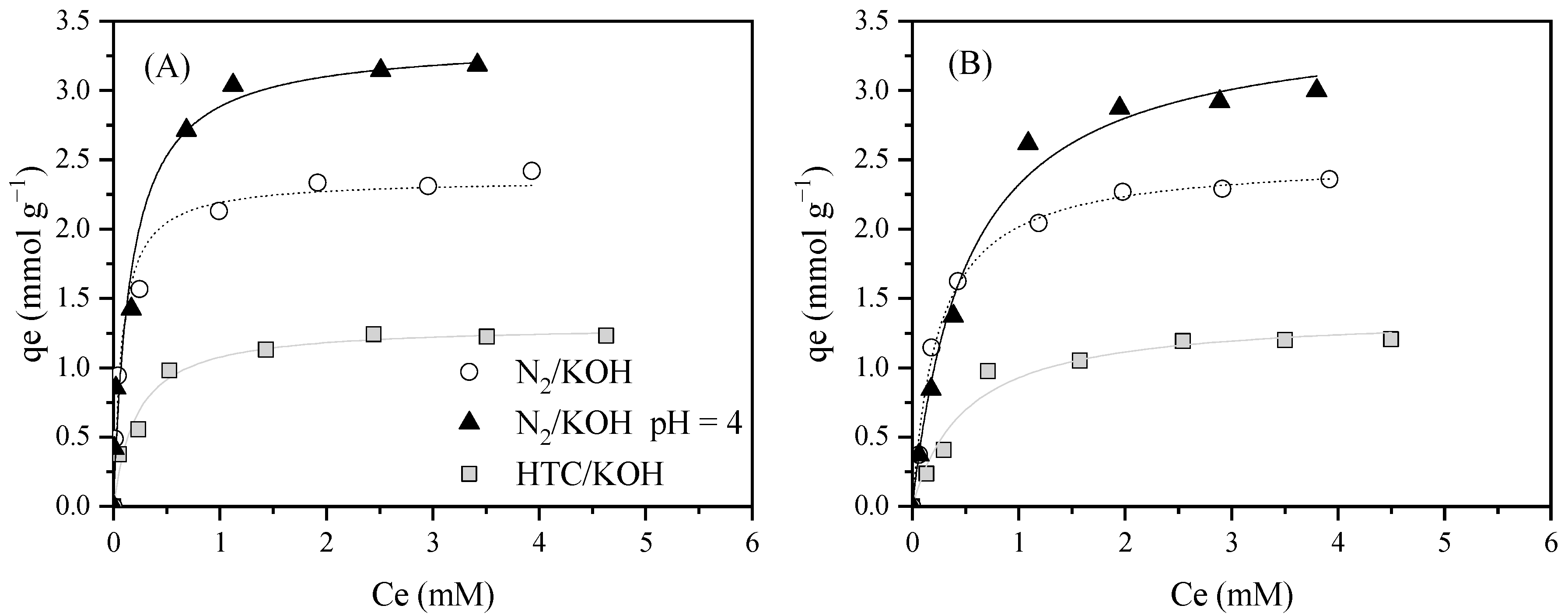

| N2/KOH | 1304 | 0.029 | 0.605 | 70.32 | 0.90 | 0.22 | 0.03 | 12.93 | 15.6 | 867 | 491 | 8.0 |

| HTC/KOH | 815 | 0.025 | 0.354 | 74.33 | 0.93 | 0.28 | 0.14 | 8.16 | 16.3 | 725 | 441 | 9.0 |

| IL | AC | pH | qL Cation (mmol g−1) | kL Cation (L mmol−1) | r2 | qL Anion (mmol g–1) | kL Anion (L mmol–1) | r2 | qL Cation/qL Anion | KOW * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BmimCl | Merck | Neutral (7.3) | 0.293 ± 0.004 | 8.86 ± 0.89 | 0.995 | 0.242 ± 0.020 | 4.75 ± 2.10 | 0.882 | 1.21 | 0.0012 |

| BmimAc | Merck | Neutral (7.5) | 0.861 ± 0.089 | 0.902 ± 0.291 | 0.946 | 0.973 ± 0.069 | 0.597 ± 0.110 | 0.986 | 0.88 | 0.9126 |

| BmimMeSO4 | Merck | Neutral (7.5) | 0.707 ± 0.035 | 2.97 ± 0.67 | 0.963 | 0.725 ± 0.026 | 1.64 ± 0.230 | 0.989 | 0.98 | 0.0085 |

| BmimNTf2 | Merck | Neutral (7.6) | 1.08 ± 0.033 | 13.2 ± 2.79 | 0.975 | 1.05 ± 0.037 | 8.01 ± 1.72 | 0.971 | 1.03 | 2754.2 |

| BmimNTf2 | Chem | Neutral (7.6) | 0.990 ± 0.013 | 5.81 ± 0.43 | 0.996 | 1.01 ± 0.02 | 3.03 ± 0.30 | 0.993 | 0.98 | |

| BmimNTf2 | Norit | Neutral (7.6) | 0.850 ± 0.021 | 4.77 ± 0.62 | 0.988 | 0.912 ± 0.033 | 2.02 ± 0.30 | 0.985 | 0.93 | |

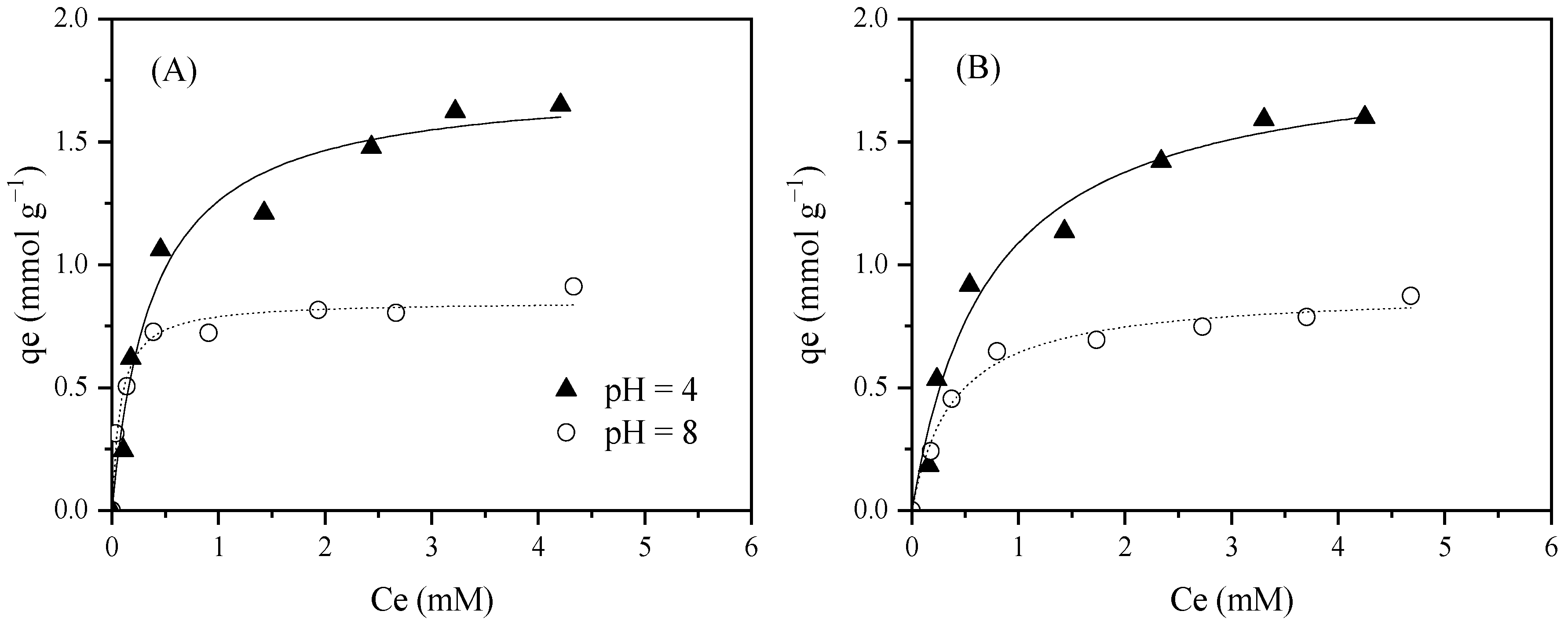

| BmimNTf2 | Merck | 4 | 1.74 ± 0.09 | 2.57 ± 0.57 | 0.971 | 1.87 ± 0.11 | 1.39 ± 0.29 | 0.976 | 0.93 | |

| BmimNTf2 | Merck | 8 | 0.851 ± 0.027 | 12.5 ± 2.52 | 0.975 | 0.893 ± 0.032 | 2.54 ± 0.40 | 0.983 | 0.95 | |

| BmimNTf2 | HTC/KOH | Neutral (7.6) | 1.31 ± 0.05 | 4.64 ± 1.02 | 0.972 | 1.39 ± 0.080 | 2.00 ± 0.46 | 0.969 | 0.94 | |

| BmimNTf2 | N2/KOH | Neutral (7.6) | 2.36 ± 0.07 | 13.1 ± 2.7 | 0.098 | 2.51 ± 0.05 | 4.08 ± 0.41 | 0.993 | 0.94 | |

| BmimNTf2 | N2/KOH | 4 | 3.36 ± 0.18 | 6.13 ± 1.88 | 0.966 | 3.53 ± 0.14 | 1.92 ± 0.28 | 0.989 | 0.95 | |

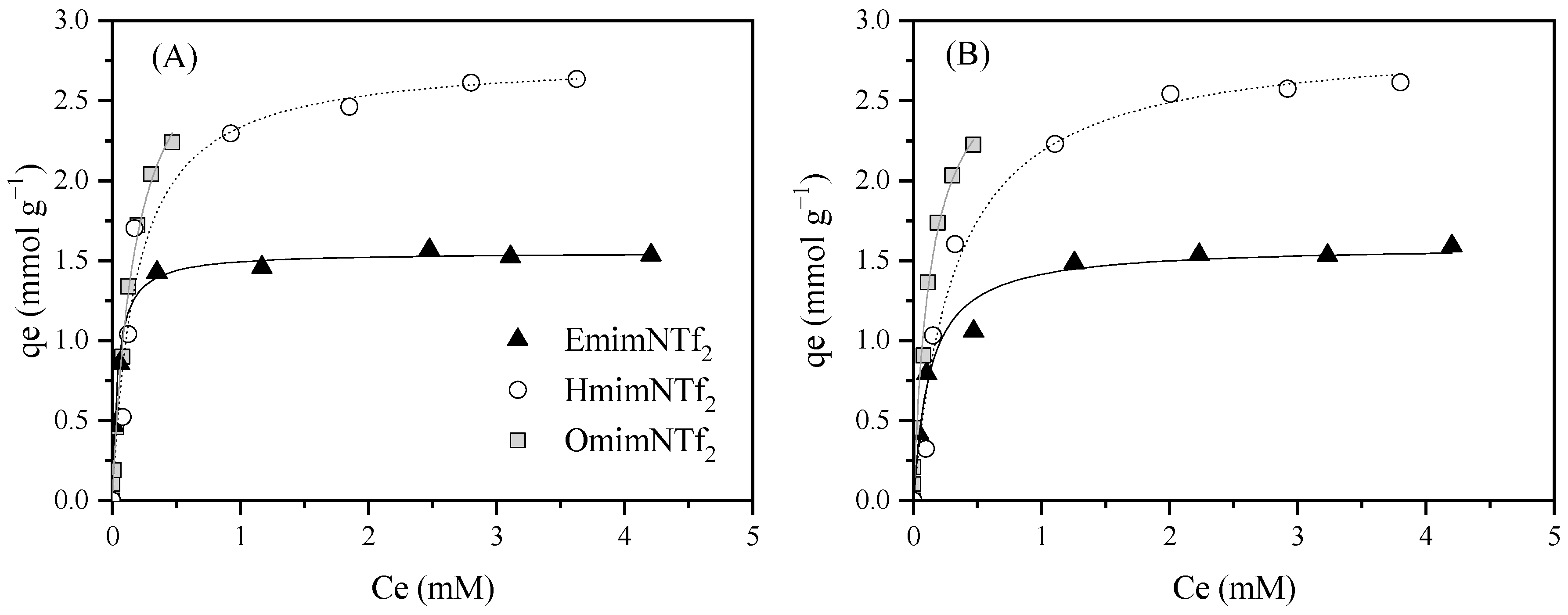

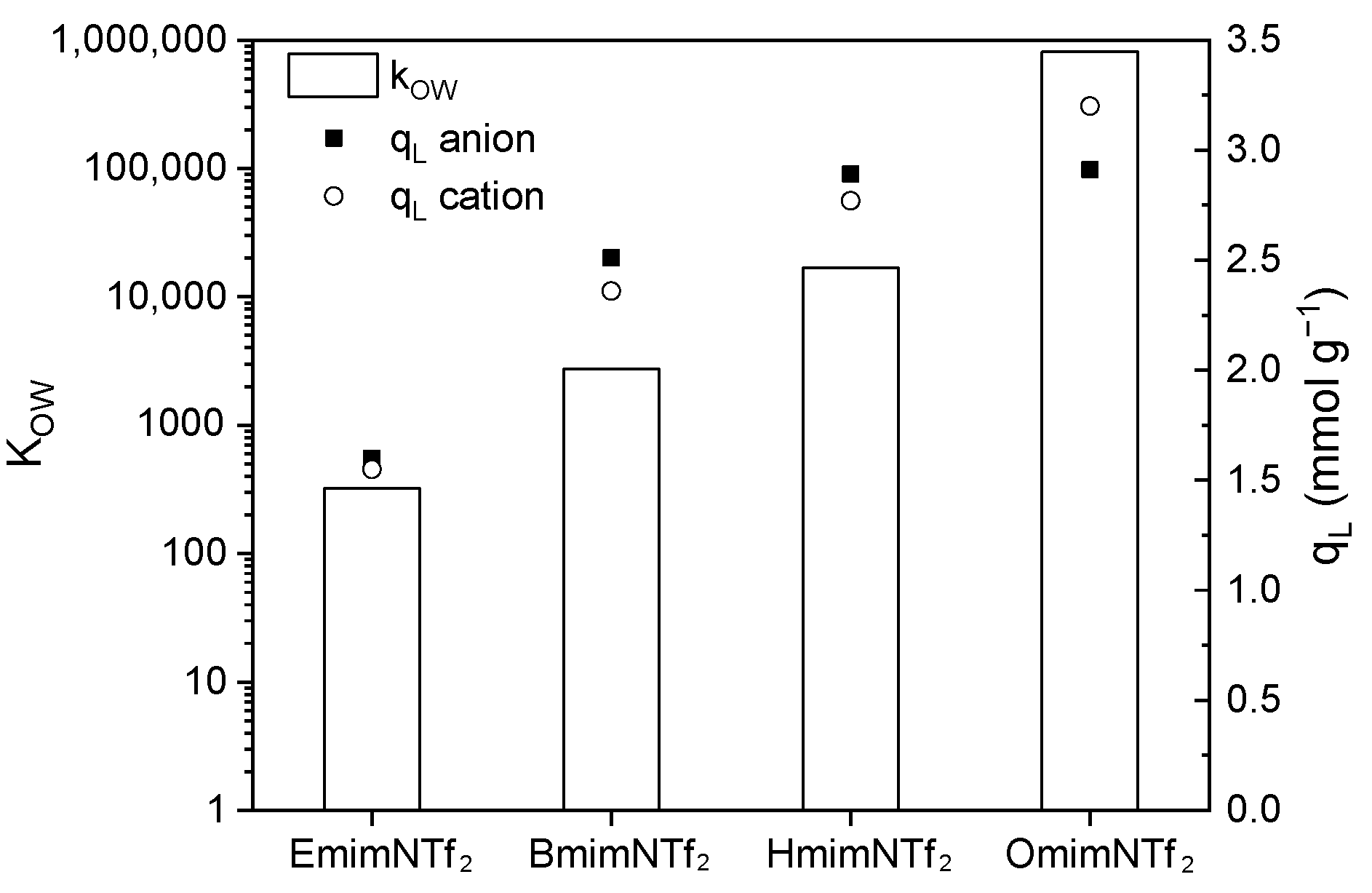

| EmimNTf2 | N2/KOH | Neutral (7.6) | 1.55 ± 0.025 | 25.2 ± 2.86 | 0.993 | 1.60 ± 0.05 | 7.88 ± 1.57 | 0.977 | 0.97 | 323.59 |

| HmimNTf2 | N2/KOH | Neutral (7.7) | 2.77 ± 0.14 | 5.34 ± 1.17 | 0.961 | 2.89 ± 0.14 | 3.06 ± 0.60 | 0.992 | 0.96 | 16,762 |

| OmimNTf2 | N2/KOH | Neutral (7.7) | 3.20 ± 0.15 | 5.46 ± 0.60 | 0.995 | 2.91 ± 0.37 | 7.28 ± 2.48 | 0.962 | 1.10 | 809,717 |

| IL | Abbreviation | Purity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1–Ethyl–3–methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide | EmimNTf2 | 99 |

| 1–Butyl–3–methylimidazolium chloride | BmimCl | 98 |

| 1–Butyl–3–methylimidazolium acetate | BmimAc | >95 |

| 1–Butyl–3–methylimidazolium methylsulfate | BmimMeSO4 | >95 |

| 1–Butyl–3–methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide | BmimNTf2 | 99 |

| 1–Hexyl–3–methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide | HmimNTf2 | 99 |

| 3–Methyl–1–octylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide | OmimNTf2 | 99 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

F. Mena, I.; Diaz, E.; Palomar, J.; F. Mohedano, A. Adsorption of Imidazolium-Based ILs Combined on Activated Carbon Obtained from Grape Seeds. Molecules 2025, 30, 4595. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234595

F. Mena I, Diaz E, Palomar J, F. Mohedano A. Adsorption of Imidazolium-Based ILs Combined on Activated Carbon Obtained from Grape Seeds. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4595. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234595

Chicago/Turabian StyleF. Mena, Ismael, Elena Diaz, Jose Palomar, and Angel F. Mohedano. 2025. "Adsorption of Imidazolium-Based ILs Combined on Activated Carbon Obtained from Grape Seeds" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4595. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234595

APA StyleF. Mena, I., Diaz, E., Palomar, J., & F. Mohedano, A. (2025). Adsorption of Imidazolium-Based ILs Combined on Activated Carbon Obtained from Grape Seeds. Molecules, 30(23), 4595. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234595